Abstract

Magnesia-dolomite refractories have emerged as sustainable alternatives to traditional carbon- or chromium-containing linings in steelmaking and cement industries. Their outstanding thermochemical stability, high refractoriness, and strong basic slag compatibility make them suitable for converters, electric arc furnaces (EAF), and argon–oxygen decarburization (AOD) units. However, their practical application has long been constrained by hydration and thermal shock sensitivity associated with free CaO and open porosity. Recent advances, including optimized raw material purity, fused co-clinker synthesis, nano-additive incorporation (TiO2, MgAl2O4 spinel, FeAl2O4), and improved sintering strategies, have significantly enhanced density, mechanical strength, and hydration resistance. Emerging technologies such as co-sintered magnesia–dolomite composites and additive-assisted microstructural tailoring have enabled superior corrosion resistance and extended service life. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of physicochemical mechanisms, processing routes, and industrial performance of magnesia–dolomite refractories, with special emphasis on their contribution to technological innovation, decarbonization, and circular economy strategies in high-temperature industries.

1. Introduction

Refractory materials have played a pivotal role in the progress of human civilization, supporting the technological development of ceramic, metallurgical, and glass industries since antiquity. They are inorganic, non-metallic materials designed to withstand extreme conditions of temperature, mechanical load, and chemical corrosion without undergoing structural or compositional degradation [1]. These materials are essential components in the operation of furnaces, converters, boilers, and other industrial equipment exposed to severe thermal and chemical environments. By maintaining structural integrity and thermal insulation under such conditions, refractories ensure the operational efficiency, safety, and longevity of high-temperature processes that sustain modern industry [2].

Refractory materials are broadly classified according to their chemical composition (acidic, basic, and neutral or special), manufacturing process (sintered or fused), form of implementation (shaped or unshaped), and porosity (dense or porous) [3,4]. Regardless of classification, their functional performance depends on their microstructure and phase assemblage, particularly the presence of highly refractory phases such as mullite, corundum, periclase, doloma, spinel, and alumina [5]. Structurally, refractories are composed of four main elements: coarse aggregates (1–2.5 mm), fine fillers (<150 µm), binders or cements, and a network of pores that influence mechanical and thermal behavior [6].

Among the various families, basic refractories mainly based on magnesia (MgO), dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2), forsterite, and spinel are indispensable due to their high melting temperatures (≥2000 °C), strong chemical stability in basic atmospheres, and excellent resistance to lime- and iron-rich slags [7,8]. They are extensively used for lining primary and secondary steelmaking furnaces, converters, ladles, and kilns, where extreme thermal and chemical stresses prevail [9]. Magnesia-based refractories have long been recognized for their exceptional thermal stability (melting point ≈ 2800 °C), resistance to basic slags, and mechanical integrity at elevated temperatures. The raw materials for magnesia production are derived from natural magnesite ores or synthesized from seawater and inland brines through precipitation and calcination processes [10,11]. Depending on the production route, magnesia may be sintered (dead-burned) or fused (electrocast), the latter conferring enhanced purity and microstructural homogeneity. These characteristics make magnesia refractories indispensable in steel, cement, and glass industries, where they serve as primary linings and thermal barriers [12].

Dolomite-based refractories derived from the calcination of dolomite into doloma (CaO + MgO) have attracted attention due to their thermodynamic compatibility with steelmaking slags, cost-effectiveness, and abundant availability. The CaO–MgO system exhibits an eutectic temperature near 2370 °C, endowing doloma with remarkable refractoriness [13,14]. However, the hydration susceptibility of doloma, particularly of its free lime content, remains a key limitation influencing handling, storage, and performance. Advances in sintering, impurity control, and microstructural stabilization have led to the development of improved doloma refractories with enhanced hydration resistance and densification behavior [15,16].

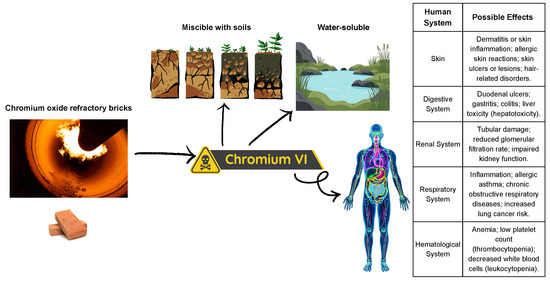

Within basic refractories, magnesia–dolomite (MgO-CaO) refractories have gained increasing relevance as high-performance and environmentally sustainable alternatives to conventional magnesia–chrome or magnesia–carbon systems. Their advantages include high refractoriness, strong resistance to basic slags, and the absence of chromium compounds, which eliminates toxic emissions associated with Cr6+ during service or disposal [17,18]. This aspect aligns closely with the global industrial transition toward cleaner production, circular economy strategies, and lower carbon footprints. However, the practical application of magnesia–dolomite refractories is not without challenges. Their main limitation lies in the susceptibility to hydration caused by the presence of free lime (CaO), leading to volumetric expansion, microcracking, and loss of mechanical integrity during storage or exposure to moisture and water vapor at service conditions [19,20]. In addition, these materials exhibit moderate thermal shock resistance, tendency to form low-melting phases in contact with Al2O3- or SiO2-rich slags, and difficulties in achieving a dense, homogeneous microstructure that guarantees long-term stability. Further constraints arise from the high cost of functional additives (TiO2, ZrO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3) and the limited industrial validation of laboratory-scale innovations, which still hinder large-scale deployment [18].

Historically, calcined dolomite refractories (doloma bricks) were first introduced in steelmaking furnaces and LD converters during the mid-20th century because of their ability to form protective lime-rich layers that enhance slag resistance and extend lining life. Despite these advantages, their widespread use was initially restricted by poor hydration resistance and short service life, prompting the development of hybrid magnesia–dolomite compositions with improved chemical and mechanical stability. The combination of MgO and CaO phases offers an optimal balance between refractoriness, slag compatibility, and cost-effectiveness, making MgO–CaO systems particularly attractive for modern steelmaking and cement industries [21,22].

Industrial validation of magnesia–dolomite refractory innovations faces several interconnected challenges that hinder the transition from laboratory-scale research to industrial implementation. Scale-up often introduces inconsistencies in sintering temperature control, raw material uniformity, and process atmosphere, affecting product reproducibility and quality [14]. Moreover, the high energy requirements of high-temperature processing increase production costs and carbon emissions, limiting rapid adoption [11]. The lack of pilot-scale facilities and the stringent standards for quality certification further constrain technology transfer. Overcoming these barriers demands stronger collaboration between academia and industry, focused investment in pilot-scale validation, and the development of scalable, energy-efficient production routes for advanced MgO–CaO refractories [11,14].

In recent decades, the design of magnesia–dolomite refractories has evolved from empirical formulation toward scientific material engineering, supported by phase diagram analysis, thermodynamic modeling, and advanced sintering technologies. The incorporation of functional additives, nanostructured oxides (nano-Al2O3), and in situ spinel formation mechanisms has markedly enhanced hydration resistance, densification kinetics, and thermal shock tolerance [23]. Emerging processing technologies—such as microwave sintering, spark plasma sintering, and additive manufacturing—offer new routes to control grain boundary chemistry and minimize energy consumption. These innovations have led to magnesia–dolomite refractories with higher chemical purity, finer microstructural control, and improved corrosion resistance, enabling their use in increasingly demanding thermal environments [18,24].

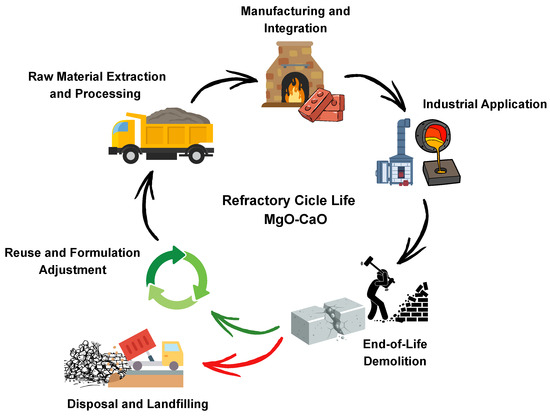

Beyond property optimization, sustainability considerations are reshaping refractory development. Novel approaches now emphasize recycling spent refractories, reducing CO2 emissions during MgO production, and reusing industrial by-products as raw materials, consistent with the broader principles of circular economy and resource efficiency. These strategies not only improve environmental performance but also contribute to lowering production costs and conserving critical mineral resources [25,26].

The present review aims to provide a comprehensive and critical analysis of advances in magnesia–dolomite refractories, encompassing their microstructural evolution, thermochemical behavior, mechanical and corrosion resistance, and industrial applications. Special emphasis is placed on recent technological developments and sustainability-driven innovations, including nanoparticle engineering, additive incorporation, sintering optimization, and recycling routes. The review also discusses current challenges and future prospects for magnesia–dolomite systems in next-generation high-temperature processes, particularly in steelmaking and cement manufacturing, where energy efficiency, emission reduction, and durability are strategic priorities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Criteria for Selection and Exclusion of Research

To ensure transparency, rigor, and replicability in this systematic review, a clearly structured protocol was adopted. Systematic reviews require methodological precision and consistent criteria to evaluate the relevance and scientific quality of the included studies. In the absence of such rigor, many reviews risk producing incomplete or unreliable conclusions. Therefore, a strict set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was designed to preserve the thematic alignment and academic robustness of this research.

The review followed a structured methodology consistent with the PRISMA statement, ensuring transparency and reproducibility in the selection and synthesis of the scientific evidence. A comprehensive search and screening process was conducted across Scopus, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, and MDPI databases, prioritizing recent advances published between 2010 and 2025. The structure and inclusion criteria were aligned with previously validated systematic approaches reported in related research (Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DCHPW).

The study focuses on magnesia–dolomite refractories, with particular attention to their mechanical performance, thermal shock resistance, corrosion behavior, slag resistance, hydration resistance, and sustainability aspects. In this context, sustainability was understood to include energy efficiency during processing, the utilization of recycled or secondary raw materials, CO2 emission reduction strategies, life-cycle and circular economy approaches, and resource optimization within refractory production. Based on this research scope, the following criteria were established:

- Keyword Focus—Selected studies must explicitly address refractory systems based on magnesia, dolomite, or basic MgO–Dolomite compositions, combined with technical properties such as mechanical performance, thermal shock resistance, corrosion resistance, or recycling.

- Publication Date Range—Only publications between 2018 and 2025 were considered, ensuring a current perspective on recent advances.

- Subject Area Filtering—To maintain disciplinary focus, publications from non-engineering or non-materials domains such as dentistry, sociology, agriculture, mathematics, and business were excluded.

- Document Type—Only peer-reviewed journal articles in English were included. Non-article types such as patents, proceedings, book chapters, and technical reports were excluded to ensure consistency in the scientific rigor of the dataset.

- Thematic Relevance—Papers unrelated to refractory performance or focused on unrelated technologies (fuel cells, membranes, semiconductors, thin films, or medical applications) were excluded, as these do not align with the structural and thermomechanical objectives of this study.

- Final Search Code:

- The search string used was the following Listing 1:

| Listing 1. Scopus search string for magnesia—dolomite refractory materials |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY("magnesia refractory*" OR "dolomite refractory*" OR "basic refractory*" OR "MgO-CaO*") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY("mechanical properties" OR "thermal shock" OR "corrosion resistance" OR "slag resistance" OR "hydration resistance" OR "sustainability" OR "recycling") AND PUBYEAR > 2017 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE,"ar" ) OR LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE,"English" ) OR EXCLUDE ( DOCTYPE,"p" ) OR EXCLUDE ( DOCTYPE,"k" ) OR EXCLUDE ( DOCTYPE,"d" ) OR EXCLUDE ( DOCTYPE,"Fuel Cells" ) OR EXCLUDE ( DOCTYPE,"Membranes" ) OR EXCLUDE ( DOCTYPE,"Semiconductors" ) OR EXCLUDE ( DOCTYPE,"Catalysts" ) OR EXCLUDE ( DOCTYPE,"Medical Applications" ) OR EXCLUDE ( DOCTYPE,"Thin Films" ) ) AND ( EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA,"DENT" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA,"SOCI" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA,"AGRI" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA,"MATH" ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA,"BUSI" ) ) |

2.2. Analysis Guide for Systemic Review of MgO–Dolomite Refractory Research

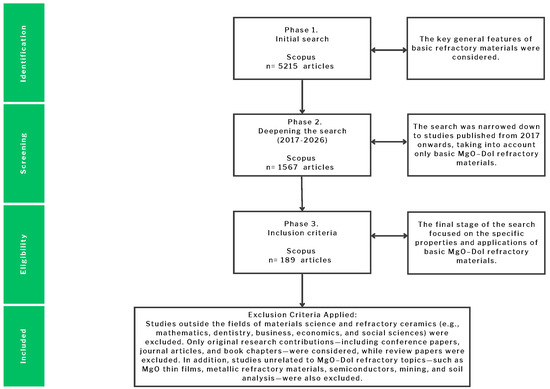

The analysis process also followed a three-phase framework adapted for the systematic review of basic refractories, specifically MgO–Dolomite systems. As illustrated in Figure 1, the initial search in Scopus retrieved 5215 articles. After refining the period of interest to 2017–2026 and restricting the scope to materials science and ceramic engineering, the dataset was reduced to 1567 articles. Finally, by applying strict inclusion and exclusion criteria focused on magnesia–dolomite refractory materials, 189 articles were selected for in-depth analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the selection and exclusion process applied in the systematic review of magnesia–dolomite refractory materials.

This procedure ensured that the reviewed publications were aligned with the structural, thermomechanical, and corrosion-resistance aspects that directly influence the performance of basic refractories in high-temperature industrial applications. The progressive filtering process excluded studies outside of the core disciplinary scope, such as mathematics, dentistry, business, economics, and social sciences. Moreover, topics unrelated to MgO–Dolomite refractories (Thin films, metallic refractory alloys, semiconductors, mining, and soil analysis) were systematically removed to guarantee thematic relevance.

The final selection emphasizes research that investigates mechanical properties, hydration resistance, slag and corrosion resistance, thermal shock performance, and sustainability approaches such as recycling. Only original contributions—including journal articles, conference papers, and book chapters—were considered, while review papers were excluded to preserve methodological consistency and to focus on primary evidence.

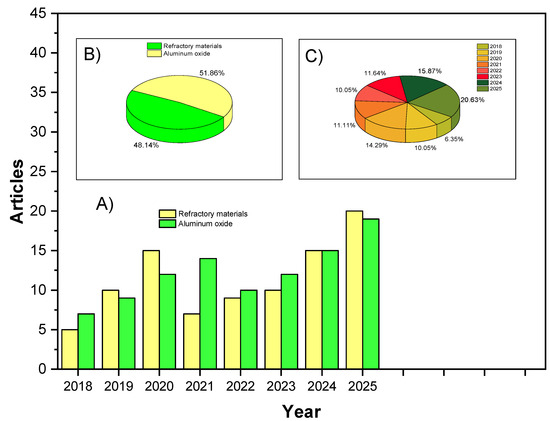

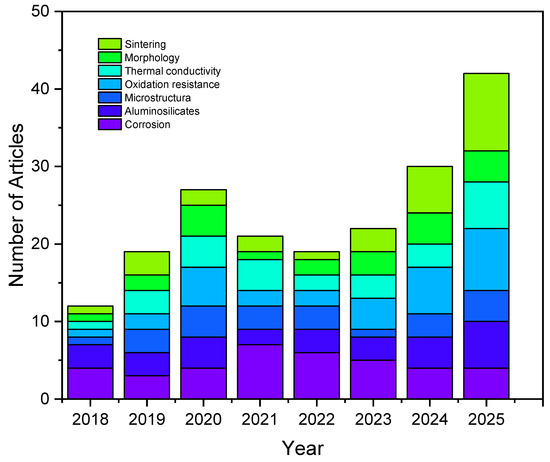

2.3. Bibliometric Trends in Magnesia–Dolomite Refractory Research

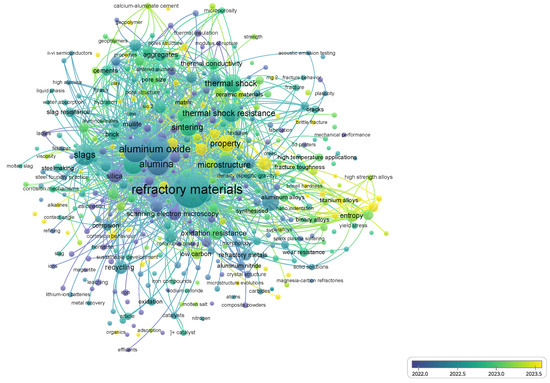

Figure 2 illustrates the bibliometric network generated with VOSviewer (1.6.20), providing a comprehensive visualization of the co-occurrence of keywords associated with refractory materials. The color scale reflects the temporal distribution of research activity, thereby allowing a critical interpretation of how the scientific focus in this field has undergone significant evolution over the last decade.

Figure 2.

Network visualization map of co-occurring keywords in refractory research, generated with VOSviewer. The color scale indicates the temporal evolution of research trends, highlighting the transition from early studies on microstructural characterization to sustainability-driven solutions and the incorporation of advanced processing technologies.

In the initial stage (before 2018), the dominant terms were strongly linked to fundamental aspects of refractory science, such as pore structure, hydration, calcination, and mechanical performance. These keywords indicate a period when research efforts were primarily focused on gaining a basic understanding of microstructural development, hydration resistance, and the mechanical characterization of bricks for conventional industrial use. This foundational stage was essential for establishing correlations between raw materials, processing routes, and intrinsic performance indicators.

From 2018 onward, the network shows a pronounced transition toward sustainability and environmental awareness. The increasing prominence of terms such as recycling, sustainable development, geopolymers, and effluents evidences the growing interest in minimizing the ecological footprint of refractory materials. This trend is consistent with global pressures for circular economy approaches, where the valorization of spent refractories, the substitution of carbon-intensive raw materials, and the integration of alternative binders (e.g., calcium aluminate cements or geopolymer matrices) are emerging as strategic research avenues. For magnesia–dolomite refractories in particular, such developments represent a paradigm shift from mere durability optimization to the design of systems that are both technically effective and environmentally responsible.

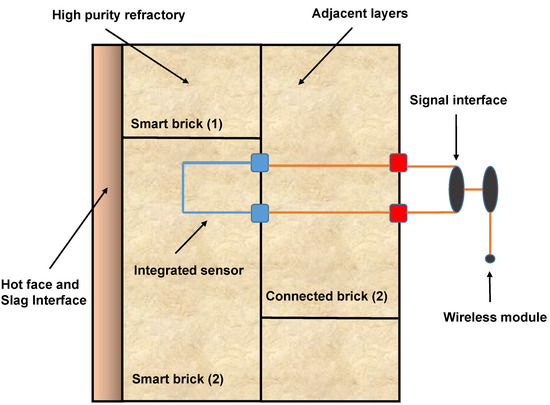

In the most recent period (2020–2025), the bibliometric map highlights the emergence of advanced processing technologies and performance-driven approaches. Notable keywords such as spark plasma sintering, 3D printing, nanoindentation, and acoustic emission testing illustrate a clear transition from conventional manufacturing to cutting-edge methods. These techniques enable a finer control over densification, microstructural tailoring, and in situ performance monitoring. Furthermore, the coupling of such innovations with computational modeling and real-time sensing aligns with the development of “smart refractories” that can withstand aggressive environments, improve thermal shock resistance, and enhance corrosion resistance under steelmaking conditions. This evolution demonstrates that the field has moved beyond classical material testing toward a more integrated framework that combines experimental, computational, and digital approaches.

Taken together, the observed keyword trends confirm the maturation of refractory research into a multidisciplinary domain that bridges traditional material science with sustainability imperatives and advanced technological solutions. For magnesia–dolomite refractories, this trajectory underscores their strategic relevance: they are no longer studied solely for their intrinsic properties, but increasingly as enablers of cleaner, more efficient, and digitally integrated industrial processes. This perspective is crucial for guiding future developments and aligning the laboratory innovations with industrial implementation. In contemporary industry, the study of materials has evolved from focusing solely on intrinsic properties to emphasizing their role as active enablers of cleaner, more efficient, and digitally integrated processes. This shift, driven by sustainability goals and Industry 4.0 technologies, highlights how refractories such as magnesia–dolomite composites contribute to energy efficiency, process optimization, and reduced environmental impact [27].

2.4. Comparative Analysis of Bibliometric Maps

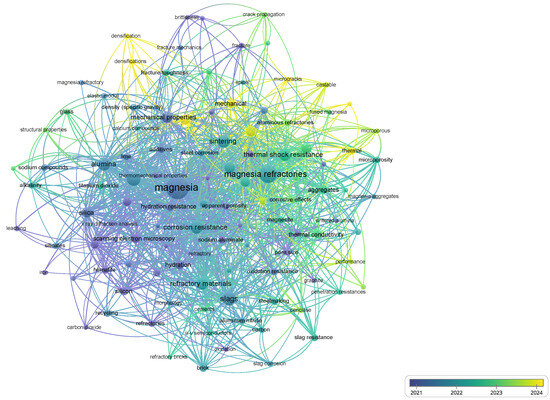

Figure 2 and Figure 3 present two network visualizations obtained through VOSviewer, each based on different exclusion criteria in the Scopus query. The comparison between these maps provides valuable insights into how search strategies affect the thematic landscape of refractory research.

Figure 3.

Network visualization map of co-occurring keywords (strict exclusion criteria). Highlights the mechanical and chemical performance terms in refractories.

In the first network (Figure 2), which was generated with a broader set of results, the most recurrent keywords were associated with general materials science and sustainability. Terms such as geopolymers, sustainable development, effluents, and 3D printers were prominent, reflecting the expansion of refractory research into multidisciplinary areas that address environmental and technological innovation.

In contrast, the second network (Figure 3), which applied stricter exclusion filters to remove unrelated domains, revealed a more focused set of keywords directly linked to refractory performance. Concepts such as fracture mechanics, slag corrosion, hydration resistance, and oxidation resistance became central nodes, pointing to a technical and application-driven orientation. This suggests that narrowing the scope of the search reduces noise from peripheral disciplines and highlights the mechanical, chemical, and thermomechanical challenges that define the state-of-the-art in magnesia-based refractories.

The comparative results, summarized in Table 1, demonstrate that the exclusion strategy plays a critical role in shaping bibliometric analyses. While broader queries capture interdisciplinary trends and sustainability perspectives, refined queries emphasize the core scientific and engineering issues relevant for industrial applications.

Table 1.

Comparison of bibliometric maps obtained with different exclusion criteria.

2.5. Classification of Basic Refractories

Basic refractories are a crucial class of materials engineered to withstand high temperatures and corrosive environments dominated by basic oxides, such as those found in steelmaking, cement production, and specific non-ferrous metallurgical processes. Their primary constituents are magnesia (MgO) and doloma (CaO·MgO), which provide excellent resistance to chemical attack from slags rich in calcium and magnesium oxides, making them ideal for lining furnaces, ladles, and converters [7,13].

In refractory terminology, magnesia denotes magnesium oxide (MgO), typically obtained by calcining magnesite (MgCO3) or magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)2). Conversely, doloma refers both to the calcined form of dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2), consisting mainly of calcium oxide (CaO) and magnesium oxide (MgO), and to the family of refractory products such as bricks and monolithic concretes developed from this system. For this reason, doloma-based refractories are commonly designated as MgO-CaO materials in the literature and industry, reflecting their compositional basis rather than their raw mineral origin [22].

The performance of basic refractories depends on their chemical composition, microstructure, and manufacturing processes, with high-temperature firing and careful control of impurities, such as silica, being essential for optimizing strength and durability [28]. Advances in refractory technology have led to the development of castable and monolithic basic refractories that offer significant improvements over traditional shaped products. These innovations include low-cement and ultra-low-cement castables, cement-free systems, and advanced binder technologies, which result in higher densification, lower open porosity, and enhanced mechanical strength and durability [29]. The use of optimized particle packing, advanced plasticizers, and colloidal matrix additions (such as silica and alumina) further improves workability, flowability, and the final microstructure, contributing to superior thermal shock and slag corrosion resistance [30].

Installation flexibility has also increased with the introduction of self-flowing, shotcreting, and quick dry-out castables, as well as pre-cast shapes, allowing for more efficient and convenient application in complex industrial settings. These developments have blurred the line between shaped and unshaped refractories, with monolithic products now widely replacing bricks in many high-temperature processes due to their improved performance and ease of installation [31].

Characterization of these materials involves assessing mechanical, thermal, and corrosion resistance properties to ensure reliability in demanding applications [5]. Environmental concerns and resource scarcity have also driven interest in recycling spent basic refractories, with closed-loop recycling gaining traction as a sustainable approach [32].

From a compositional standpoint, basic refractories can be classified according to their main oxide phase and the additives present, highlighting the following systems.

2.5.1. Magnesia-Based Basic Refractories

Magnesium oxide (MgO), or magnesia, is the primary component in basic refractories due to its exceptionally high melting point (2852 °C) and strong chemical stability in basic environments, making it ideal for lining furnaces in steel, iron, and cement industries [33,34,35]. High-purity MgO can be produced from sources such as seawater, dolomite, and salt-lake brine, with recent advances focusing on sustainable and cost-effective manufacturing processes that reduce energy consumption and CO2 emissions [36].

The addition of materials like calcium boride (CaB6) and yttrium oxide (Y2O3) to MgO-based refractories has been shown to significantly enhance properties such as bulk density, hot modulus of rupture, oxidation resistance, and resistance to molten slag, thereby improving performance in harsh service conditions [36,37].

However, MgO is susceptible to hydration, which leads to the formation of magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)2) and causes significant volume expansion, potentially limiting the reuse of spent refractories in construction applications. Research on the hydration behavior and swelling mechanisms of MgO granules has provided information on how to manage these effects and explore alternative uses, such as soil modification [38,39].

Furthermore, the interaction of MgO-based refractories with fuel ash at high temperatures can result in chemical wear, emphasizing the need for ongoing improvements in refractory formulations to enhance durability and reduce maintenance costs. Table 2 shows the main industrial grades.

Table 2.

Comparison of magnesia types used in basic refractories.

2.5.2. Calcium Oxide-Based Refractories

CaO-based refractories are valued for their exceptionally high refractoriness and strong basicity, making them suitable for specialized metallurgical applications such as steel refining where MgO contamination must be avoided. However, their practical use is limited by their tendency to rapidly hydrate and degrade upon exposure to moisture, necessitating careful storage and handling to maintain performance [46]. Research has focused on improving their hydration resistance and mechanical properties by incorporating additives such as microsilica, ZrO2, and calcium hexaluminate, which can reduce porosity, enhance strength, and improve thermal shock resistance [47,48,49,50]. For example, small additions of CaO in composite refractories can significantly increase hardness and strength, while the formation of protective layers like CA2 or CaZrO3 can enhance corrosion and hydration resistance [47,49,50]. In steelmaking, CaO refractories are particularly effective in desulfurization processes, as they react with sulfur in molten alloys to form CaS, thereby improving alloy purity [49,51].

2.5.3. Magnesia–Calcium Oxide Refractories

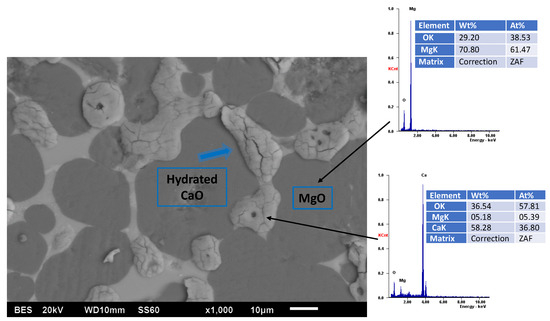

The combination of MgO and CaO in refractories creates materials with enhanced properties, leveraging the high refractoriness and thermal shock resistance of MgO alongside the basicity and slag resistance of CaO. These refractories typically form complex mineral phases such as periclase (MgO) and calcium silicates, which improve their performance in environments with variable or aggressive slags, such as those encountered in steelmaking and secondary refining furnaces [52]. However, a challenge is the tendency of free CaO to hydrate, which can compromise durability; see Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Scanning electron microscopy image of a magnesia–dolomite refractory showing the expansive hydration process of lime.

This issue is being addressed through additives like TiO2 or CaZrO3 coatings that significantly improve hydration resistance and mechanical strength by forming protective layers at grain boundaries [19,53]. Advanced sintering techniques and the use of chemical binders further optimize the microstructure, densification, and thermal behavior of MgO–CaO refractories, resulting in better resistance to slag penetration and corrosion, even under demanding conditions such as electromagnetic fields or high-temperature cycling [54,55]. These improvements make MgO–CaO refractories suitable for use in high-temperature industrial processes, including steel refining and insulation applications, where both chemical stability and thermal efficiency are critical [48].

2.5.4. Magnesia–Carbon Refractories

The MgO–C (magnesia–carbon) refractory system is a cornerstone in the lining of electric arc furnaces and steel ladles due to its unique combination of high refractoriness, excellent thermal shock resistance, and strong resistance to slag and metal penetration. The addition of natural graphite enhances thermal shock resistance and reduces slag infiltration, but graphite is prone to oxidation at high temperatures, which can compromise the refractory’s integrity. To address this, antioxidant additives such as aluminum, silicon, or magnesium are incorporated to protect the carbon phase by preferentially reacting with oxygen, thereby extending the refractory’s service life and maintaining its mechanical strength [56]. Recent advances include the use of nano carbon to reduce overall carbon content without sacrificing performance, which not only improves oxidation resistance and mechanical properties but also addresses environmental concerns related to CO and CO2 emissions [57]. The microstructure and phase composition, including the formation of in situ ceramic phases like spinel, further influence the durability and corrosion resistance of these refractories [58]. Optimizing the balance between magnesia, carbon, and antioxidants is crucial for maximizing performance and longevity in the harsh environments of steelmaking [59].

2.5.5. Sintered Dolomite Refractories (Doloma)

Doloma refractories, produced by calcining dolomite (CaCO3·MgCO3) at temperatures above 1700 °C, yield materials predominantly composed of periclase (MgO) and calcium oxide (CaO) phases. These refractories are widely employed in steelmaking processes, such as LD (Linz–Donawitz) and AOD (Argon Oxygen Decarburization) converters, owing to their high refractoriness, strong resistance to basic slag attack, and excellent thermochemical stability under severe operating conditions [60]. Doloma refractories with a silica content below 1 wt% exhibit significantly higher thermodynamic stability compared with high-alumina and even magnesite-based refractories. Refractory-grade doloma generally contains less than 2.5 wt% of total impurities—mainly SiO2, Fe2O3, and Al2O3—and more than 97.5 wt% of combined CaO and MgO. However, most high-purity dolomite ores present considerable challenges during calcination and sintering, as achieving high density often demands specialized processing techniques. During production, the carbonate precursor (dolomite) is thermally decomposed to its oxide form (doloma) and subsequently sintered at temperatures above 1850 °C in either rotary or shaft kilns. Two principal manufacturing routes are employed for this purpose: the single-pass and the double-pass processes [13,61]. These refractories are particularly important in desulfurization, where in situ generated magnesium from decomposed dolomite effectively removes sulfur from molten iron, with the desulfurization rate primarily governed by reaction kinetics rather than diffusion processes, and showing optimal efficiency at elevated temperatures up to about 1623 K [62]. Doloma-based refractories are favored for their low cost and wide availability, though their service life is generally shorter than that of more advanced MgO–C refractories [63]. Studies indicate that the dissolution behavior and wear resistance of doloma refractories in contact with steelmaking slags depend on their microstructure, phase composition, and the basicity of the slag, with higher MgO content and optimized firing conditions improving performance [64]. Advances in processing, such as the development of off-fluxed dolomite compositions and improved sintering techniques, aim to enhance the mechanical and refractory properties of these materials, making them more competitive for industrial applications [65]. Despite some limitations in durability, doloma refractories remain a practical choice for many steelmaking operations due to their effectiveness in slag conditioning and sulfur removal, as well as their economic advantages [63].

2.6. Fundamental Physicochemical Properties

Basic refractories based on dolomite (CaCO3·MgCO3) and its calcined derivatives exhibit a distinctive set of physicochemical properties that determine their performance in high-temperature industrial applications, particularly in steelmaking processes. The most relevant properties include refractoriness, bulk density, chemical reactivity, slag resistance, and hydration resistance. Table 3 shows a summary of these properties.

The thermal decomposition of dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) is a well-established two-step endothermic process, extensively characterized by Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) and Thermogravimetric (TG) methods [66]. The first decomposition step occurs around 650–750 °C, where dolomite releases CO2 and forms a metastable mixture of MgO and CaCO3, often referred to as “half decomposition” [67]. The second, more intense endothermic event takes place between 800 and 950 °C, corresponding to the decomposition of the remaining CaCO3 into CaO and additional CO2 [68].

Above 1000 °C, solid-state reactions between CaO and MgO can occur, leading to limited sintering and the formation of periclase–lime aggregates, with the overall weight loss (typically 45–47%) reflecting the total CO2 released from the original carbonate structure [69]. The process is influenced by factors such as particle size, impurities, and the partial pressure of CO2, which can shift the decomposition temperatures. These transformations are crucial for understanding the calcination behavior and reactivity of doloma, especially in refractory and industrial applications where the properties of the resulting oxides are critical [70].

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of dolomitic refractories and their relevance in steelmaking processes.

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of dolomitic refractories and their relevance in steelmaking processes.

| Property | Description and Impact in Steelmaking | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Refractoriness | High melting point and thermal stability make dolomite suitable for lining furnaces and converters. | [71,72] |

| Bulk Density | Affects mechanical strength and resistance to slag penetration; influenced by calcination process. | [65,73] |

| Chemical Reactivity | Reactivity with slag and steel is determined by mineralogy, crystal size, and calcination degree. | [64,74] |

| Slag Resistance | Good resistance to basic slags (high CaO, MgO); calcined dolomite dissolves efficiently in slag. | [64,75] |

| Hydration Resistance | Calcined dolomite (Doloma) is prone to hydration; hydration resistance is lower than MgO bricks. | [72,76] |

The high refractoriness of the materials means that their ability to withstand extremely high temperatures without melting or deforming is crucial for applications such as steelmaking and high-temperature reactors. In dolomitic ceramic materials, their chemical composition, microstructure, and thermal stability are determined primarily. The presence of refractory phases such as periclase (MgO), calcium oxide (CaO), forsterite (Mg2SiO4), spinel, and corundum (Al2O3) contributes to high melting points, often above 1700 °C, ensuring structural integrity at elevated temperatures [77,78]. High-entropy ceramics also offer exceptional resistance to temperature due to their stable multielement microstructures [79,80]. A well-sintered, dense microstructure with minimal porosity enhances the resistance to thermal shock and mechanical strength [81], while additives like Cr2O3 promote the formation of high-temperature phases and improve densification [81]. Maintaining a high MgO/SiO2 ratio (>2.2) prevents the formation of low melting point compounds and ensures desirable phase assemblages [82]. In addition, chemical and mechanical stability at high temperatures further supports a long service life in aggressive steelmaking environments [83].

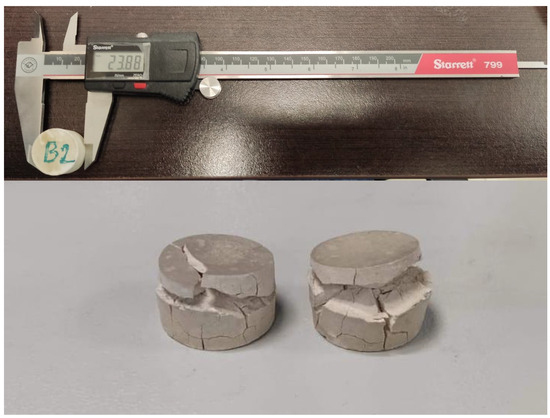

Calcined dolomitic refractory bricks are valued for their high bulk density, which typically ranges from 2.6 to greater 3.0 g/cm3, see Table 4. The higher bulk density in these bricks is closely related to a lower open porosity, resulting in improved mechanical strength and greater resistance to slag penetration. The performance of calcined dolomitic refractory bricks is strongly influenced by the relationship between bulk density and open porosity. Higher bulk density is generally associated with lower open porosity, which directly enhances compressive strength, resistance to chemical corrosion, and slag penetration [19,84]. The achievement of optimal density depends on several manufacturing parameters, including raw material quality, firing temperature, and binder selection. For example, the use of tar-based binders combined with high pressure compaction (500 kg/cm2) can consistently produce bricks with bulk densities exceeding 2.6 g/cm3 and low porosity [84]. Furthermore, higher sintering temperatures, such as 1400 °C, significantly improve densification and reduce porosity, as demonstrated in the fabrication of dolomite-based forsterite bricks [85].

Table 4.

Bulk density ranges of magnesia dolomite refractory materials by product.

Dolomitic refractories and dolomite-based materials are widely used for desulfurization in metallurgical and fuel processing industries due to their strong chemical reactivity with acidic slag components and sulfur compounds; see Figure 5. Their effectiveness in desulfurization is primarily due to the active participation of both calcium and magnesium oxides in sulfur capture reactions.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of sulfur capture by calcined dolomite (CaO) in high-temperature gas environments. Modified from [62].

Dolomite, when decomposed and reduced such as in aluminothermic reactions, generates metallic magnesium, which dissolves in molten iron and reacts with sulfur to remove it efficiently. The desulfurization rate increases with higher temperatures and greater amounts of reactants, but tends to plateau above 1623 K. This process is primarily controlled by the chemical reaction kinetics rather than by mass diffusion, and it occurs predominantly in the homogeneous phase, rather than via magnesium vapor bubbles [62].

Dolomite and other calcium-based sorbents (such as limestone) are effective for capturing sulfur in coal gasification and fluidized-bed combustion systems. The active component, CaO (obtained from the calcination of dolomite), reacts with hydrogen sulfide (H2S) to form stable calcium sulfide (CaS), as shown in Equation (1):

Dolomite remains reactive at elevated temperatures (above 1023 K), making it suitable for high-temperature sulfur capture processes [89,90]. However, the presence of water vapor imposes thermodynamic limitations on the lowest achievable H2S concentrations due to equilibrium constraints. In contrast, the presence of CO2 does not significantly hinder the sulfur capture efficiency, though it may influence the initial calcination of the sorbent [90]. Dolomite is a promising raw material for SO2 sorbents in fluidized combustion systems, as both calcium oxide (CaO) and magnesium oxide (MgO) actively participate in sulfur dioxide binding. The resulting sulfation products, such as CaSO4 and MgSO4, are thermally stable up to 1100 °C, which supports the applicability of dolomite in high-temperature desulfurization processes [91].

Slag resistance in refractories is strongly influenced by the material’s microstructure, the MgO/CaO ratio, and the basicity of the contacting slag. A higher MgO content generally improves resistance to acidic slags, while the CaO content and the slag basicity affect the corrosion behavior and the formation of either protective or reactive interfacial layers.

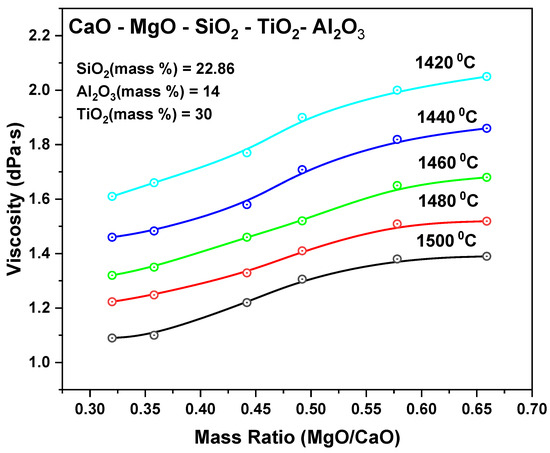

MgO-CaO refractories are primarily governed by microstructural features, the MgO/CaO ratio, and the basicity of the contacting slag. Finer grain boundaries contribute to the formation of dense isolation layers that block slag penetration [92], while highly dispersed microstructures, especially those containing stabilizing phases like ZrO2, enhance chemical durability at the slag interface [93]. Chemically, increasing the MgO/CaO ratio enhances resistance to acidic slags and initially reduces slag viscosity, as shown in Figure 6. However, excessive MgO content may reverse this trend, leading to precipitation of MgO-rich phases and a subsequent increase in viscosity, reducing slag fluidity at high MgO/CaO ratios [44]. Higher slag basicity, typically expressed as CaO/SiO2, depolymerizes the slag structure and enhances flow, but overly basic compositions can lower corrosion resistance in MgO–CaO systems [94,95]. CaO content also promotes reactions with sulfur and other impurities, supporting steel refinement, but may increase corrosive interaction in low-basicity slags [92]. Optimal ranges—such as MgO/CaO ratios between 0.34 and 0.55 [93], and basicity ratios between 1.0 and 1.2 [94]—have been identified as the most effective balance between viscosity control and corrosion resistance.

Figure 6.

Effect of MgO/CaO mass ratio on the viscosity of CaO–SiO2–Al2O3–MgO–TiO2 slags at various temperatures. Modified from [96].

Hydration resistance is a critical property for the presence of free lime in MgO–CaO refractories that makes these materials highly reactive when exposed to water in either liquid or vapor form. This reactivity originates from the weak Ca–O bond and the inherent structural instability of lime, which crystallizes in a face-centered cubic (FCC) structure [97]. Because the ionic radius of Ca2+ is relatively large, it cannot be stably accommodated within the sixfold coordination sites of the lattice. Consequently, CaO tends to react with H2O to form calcium hydroxide [Ca(OH)2] [98,99], as described by the following Equation (2):

The hydration of lime (CaO) to form calcium hydroxide [Ca(OH)2, also known as portlandite] is accompanied by a significant volume increase due to the lower density of portlandite (approximately 2.21 g/cm3) compared to lime (approximately 3.34 g/cm3). This expansion is well documented in cementitious systems and is a direct result of the crystallization and growth of Ca(OH)2 within the material matrix, which can lead to internal stresses and potential cracking if not properly managed [100]. The expansion is particularly pronounced when free lime is present in concrete or soil stabilization applications, as the hydration reaction causes the volume of the affected region to nearly double, especially for smaller CaO grains where a larger proportion of the grain hydrates [101].

Structurally, the hydration process involves an expansion in the direction perpendicular to the close-packed planes: from the (111) plane and [111] direction in FCC–CaO to the (001) plane and [001] direction in HCP–Ca(OH)2 [102]. The interplanar spacing changes significantly from approximately 2.78 Å to 4.91 Å, leading to nearly a twofold volumetric expansion.This anisotropic growth in the [001] direction generates internal stresses that can seriously damage the surrounding matrix and promote microcracking [103].

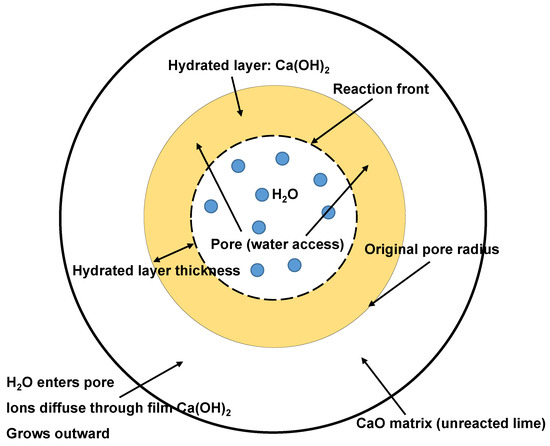

The hydration of CaO-based refractories proceeds through three consecutive stages [104]. In the first stage, water molecules come into direct contact with the exposed surface of the lime matrix, resulting in a rapid chemical reaction that forms an initial layer of hydrated compounds. As the reaction continues, the second stage begins, during which the growing hydration layer acts as a diffusion barrier that slows down the ingress of water and ionic species. Once this layer reaches a critical thickness, internal stresses generated by shrinkage exceed the mechanical strength of the material, leading to the development of microcracks. Finally, in the third stage, known as the “dusting stage,” the hydration rate rises abruptly, causing extensive structural damage and, in some cases, complete disintegration of the material due to the expansive formation of Ca(OH)2 [102].

The three-stage hydration process previously described can be visualized through the cylindrical pore model [102], which provides a clear geometrical interpretation of the reaction front propagation in porous CaO systems. Figure 7 schematically represents this mechanism, illustrating how H2O molecules diffuse through open cylindrical pores, forming a physically and chemically adsorbed water layer on the pore walls. During CaO hydration, H2O molecules diffuse through open cylindrical pores and form a physically and chemically adsorbed water layer on the pore walls. Within this adsorbed layer, the diffusion of OH− and Ca2+ ions facilitates the nucleation and growth of Ca(OH)2, causing the hydrated layer to progressively expand toward the unreacted CaO matrix. As the reaction front advances, the thickness of the Ca(OH)2 layer increases, which reduces the effective pore radius and leads to significant internal stresses due to the volumetric mismatch between the original CaO and the newly formed Ca(OH)2. This process can result in microcracking and, in extreme cases, dusting phenomena, as the weak tensile strength and poor crack resistance of the Ca(OH)2 layer make it prone to disintegration under stress. Pore blockage and the resulting internal stresses are key factors in the mechanical degradation of CaO-based materials during hydration, and the extent of these effects depends on factors such as pore structure, hydration rate, and the physical properties of the hydration products [105,106].

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the hydration mechanism of CaO based on the cylindrical pore model. Modified from [102].

Several methods have been developed to improve the hydration resistance of calcium oxide (CaO), a critical issue in refractories and high-purity applications due to its high reactivity with moisture. One of the most effective strategies involves the incorporation of additives such as yttrium oxide, manganese oxide, chromium oxide, Fe2O3, and zirconia, which form solid solutions or secondary phases with CaO, thereby stabilizing the microstructure and impeding water ingress [107]. Complementary approaches like high-temperature sintering with additives and surface treatments lead to densification, reducing porosity and moisture penetration [108]. Microstructural control through advanced processing techniques such as cold isostatic pressing or plasma-assisted synthesis can further reduce grain boundary area and enhance hydration resistance [109]. Composite formation, particularly the incorporation of Ca2SiO4 nanoparticles, has shown promise in pinning CaO grains, mitigating agglomeration, and simultaneously improving hydration resistance and thermal behavior in energy storage contexts [110].

Mechanistically, hydration occurs rapidly upon exposure to water, releasing heat and forming Ca(OH)2; however, the addition of specific oxides and superplasticizers can delay this transformation and modify the morphology of the hydration products [98,111]. Improved resistance has been directly linked to the formation of secondary phases such as calcium ferrites and silicates, as well as to microstructural densification [107]. In high-purity applications such as CaO crucibles used in metal and alloy smelting, tailored additive strategies for improving magnesia–doloma refractories include the incorporation of metallic and ceramic nanoparticles such as ZrO2, TiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3, which promote sintering and form secondary phases that strengthen grain boundaries and enhance corrosion and thermal shock resistance [15]. Other approaches involve the use of spinel-forming oxides (MgAl2O4 or CaZrO3) to improve microstructural integrity, as well as hydrophobic additives and surface modifiers that reduce pore connectivity and prevent hydration of free CaO [16]. These strategies collectively enhance densification, mechanical strength, and durability while mitigating moisture-induced degradation in MgO-CaO systems to simultaneously maintain chemical purity and prevent premature hydration [112].

2.7. Raw Materials: Characteristics, Availability, and Geopolitics

The performance and economic viability of MgO-CaO refractories are critically dependent on the quality and characteristics of the raw materials used. Main parameters such as chemical purity, crystallinity, grain size, and the presence of minor oxides directly influence sintering behavior, hydration resistance, and mechanical integrity. High-purity dolomite and magnesite are preferred for ensuring optimal refractory behavior, while specific impurities (such as SiO2, Al2O3, or Fe2O3) can either degrade or, when carefully controlled, enhance certain properties by promoting the formation of stable secondary phases [19,20]. Well-crystallized, coarse-grained raw materials tend to improve sintering kinetics, lower porosity, and enhance hydration resistance and strength. In contrast, fine-grained or poorly crystalline sources exhibit higher reactivity and are more susceptible to moisture-induced degradation [19,113].

Geological origin also plays a pivotal role, as it determines the mineralogical structure and impurity profile of the raw materials, which in turn affects processing requirements and final refractory performance [114,115]. Sintering behavior benefits from high-purity inputs and optimal particle size distribution, facilitating densification and mechanical strength [19,20,113]. Hydration resistance can be further improved by minimizing free CaO and incorporating specific additives—such as Fe2O3, TiO2, ZnO, or hercynite—that encapsulate reactive grains and inhibit water diffusion [116,117]. Moreover, mechanical properties are significantly enhanced by combining compositional control with advanced processing techniques like high-temperature sintering or co-clinkering, which ensure microstructural uniformity and phase stability [114].

The global supply of high-grade dolomite and magnesite is unevenly distributed, with major producers such as China, Brazil, Turkey, the United States, and the European Union relying on distinct geological formations and industrial infrastructures; see Table 5. Geopolitical dynamics including export regulations, environmental policies, and supply chain vulnerabilities play a decisive role in determining market access and price stability for these critical refractory minerals. China holds a dominant position as the world’s leading supplier of magnesite, supported by substantial reserves and advanced refining capabilities. This strategic control allows China to influence global pricing and availability, often leading to volatility in markets dependent on magnesia-based refractories [118,119].

Table 5.

Major regions producing dolomite and magnesite and their industrial status.

Although Uzbekistan is not a major exporter, it possesses over 60 identified high-quality dolomite deposits. If further industrial infrastructure were developed, Uzbekistan could reduce regional dependence on imported magnesite and become a more significant player in the refractory raw material supply chain [14]. Other countries such as Brazil, Turkey, the United States, and various EU members also maintain notable dolomite and magnesite resources. However, their collective influence remains more limited in comparison to China’s export volume and market leverage [120,121].

Despite dolomite’s geological abundance in Europe, its classification as a critical raw material by the European Commission is primarily due to supply-chain vulnerabilities rather than scarcity. The production of high-purity calcined dolomite (doloma) for refractory and industrial applications is energy-intensive and subject to strict environmental regulations, which have led to a significant decline in domestic production capacity over recent decades [122]. As a result, Europe has become heavily reliant on imports especially from China for processed MgO-CaO materials, increasing exposure to market concentration and geopolitical risks [123].

This dependence is further exacerbated by the EUA broader vulnerability to supply disruptions in mineral raw materials, which can threaten economic activities and job security [123]. The dominance of external suppliers, particularly China, in critical mineral value chains raises concerns about potential coercive measures and supply restrictions, prompting the EU to consider strategies such as diversifying supply chains, reinvesting in domestic extraction and processing, and establishing partnerships with countries that uphold high socio-environmental standards [124]. These factors collectively explain why dolomite and magnesite are included in the EUA list of critical raw materials, despite their natural abundance within Europe [122].

Raw material selection must consider not only thermomechanical performance but also long term supply security and environmental impact. Strategies such as regional sourcing, beneficiation of lower grade ores, and the development of synthetic alternatives (seawater magnesia or bio-derived CaO) are being explored to ensure sustainable and resilient refractory manufacturing in a changing global context.

3. Processing and Synthesis Technologies

The production of magnesia–doloma refractory bricks traditionally relies on MgO-CaO systems, which are widely used in industries such as cement and steel due to their excellent high-temperature resistance and chemical stability.

3.1. Conventional Processes

Their production relies on the precise selection of raw materials, high-temperature calcination, and meticulous control of hydration and sintering processes. The most critical step in the manufacturing sequence is the high-temperature calcination of dolomite, which leads to the formation of calcined dolomite (doloma), typically performed at 1650–1800 °C, resulting in a composite of CaO and MgO phases [114]. This thermal treatment strongly influences the hydration resistance and mechanical properties of the final brick, making it essential for the long-term performance of the refractory in aggressive environments [125].

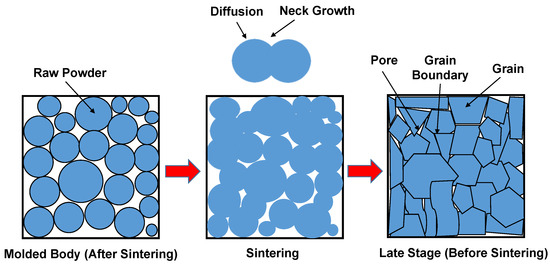

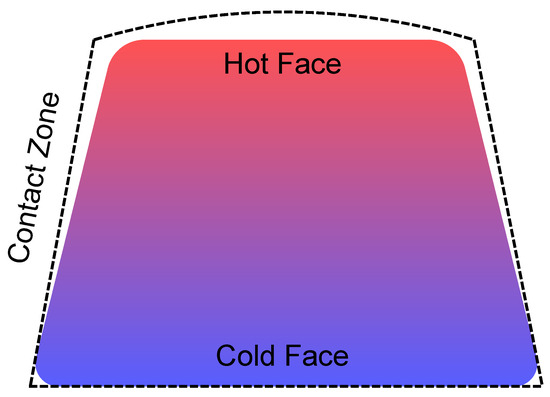

Sintering is then applied to densify the calcined powders, often at temperatures above 1700 °C, leading to the formation of interlocking grain structures and reduced porosity. During sintering, diffusion mechanisms promote bonding between adjacent particles, leading to densification, pore reduction, and the formation of grain boundaries [126], as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of the sintering process showing powder consolidation, neck growth, and grain coalescence.

To further improve mechanical strength and corrosion resistance, additives such as graphite are introduced, which act as antioxidants and thermal shock absorbers in carbon-containing refractories [56,127,128,129]. Organic binders such as phenolic resins and pitch and thermosetting resins play a critical role in the processing of magnesia–doloma refractory bricks by providing the necessary green strength before firing, thereby facilitating compaction and handling [56]. These binders also influence the final density, porosity, and mechanical properties of the bricks; therefore, the optimal binder content must be carefully controlled, as excessive amounts can increase residual porosity and compromise the integrity of the material [130,131]. In advanced applications, particularly in additive manufacturing, clean burn-off binders such as polyvinylpyrrolidone vinyl acetate (PVP–VAc) are being developed to reduce carbon residues during firing and improve the microstructural quality of the final sintered product [132,133].

Dense brick fabrication is a process focused on achieving high packing density, low porosity, and strong intergranular bonding to ensure durability and performance in demanding applications. Optimization of particle size distribution and compaction methods is essential to produce bricks with these properties for high performance applications in steel converters, cement kilns, and non-ferrous metallurgy. This is shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Main factors influencing dense brick fabrication for magnesia–dolomite refractories.

3.2. Innovative Processing Strategies

In response to the increasing demand for high performance and sustainable refractory materials, several innovative processing strategies have emerged to improve the structural, chemical, and environmental performance of MgO-CaO refractories.

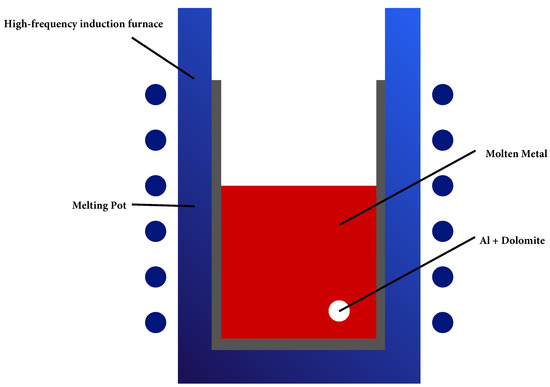

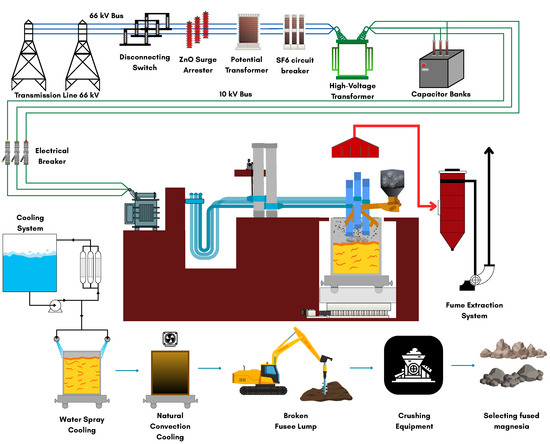

One promising development is the production of fused magnesia–dolomite co-clinkers via melting of stoichiometric mixtures at temperatures exceeding 2000 °C. Figure 9 illustrates the industrial production flow of fused magnesia, including charging, arc melting, molten pool formation, and crystallization steps paralleling the co-clinker synthesis process where dolomite and magnesia are combined and densified through high-temperature fusion [139]. Fusion of magnesia–dolomite co-clinkers at temperatures above 2000 °C achieves superior densification and phase uniformity, which is critical for high-performance refractory materials [140]. However, this process is significantly more energy-intensive than conventional sintering (typically 1550–1700 °C), with specific energy demands for fusion routes exceeding 6 GJ t−1—almost double that of sintering (≈3–3.5 GJ t−1)—and results in 30–40% higher CO2 emissions [141]. The high energy consumption is primarily due to the elevated temperatures required for complete fusion and densification. Recent research highlights that energy-saving measures, such as improved furnace insulation, heat recovery from exhaust gases, and the gradual adoption of renewable electricity, can help mitigate these environmental impacts and align fused co-clinker production with circular economy strategies [11]. Additionally, alternative approaches like optimizing particle size for sintering have shown potential to achieve high densification at lower temperatures, further reducing energy use and emissions [141]. This process yields dense, homogeneous materials with improved grain bonding, reduced porosity, and enhanced thermal shock and hydration resistance. The fusion process eliminates residual carbonates and free CaO, resulting in microstructures that are more stable under aggressive service conditions [20,87].

Figure 9.

Schematic overview of the fused magnesia industrial production process in electric arc furnaces. Modified from [139].

Another innovation involves the progressive addition of MgO to natural dolomite during calcination or sintering. This approach allows precise control of the MgO/CaO ratio, improving sinterability and hydration resistance while tailoring the final phase composition. By adjusting the additive proportions, it is possible to engineer multiphase microstructures that balance mechanical strength with corrosion and thermal resistance.

The controlled addition of MgO, or the use of dolomite with optimized Mg/Ca ratios, plays a central role in enhancing the performance of MgO-CaO refractories. From a processing standpoint, increasing MgO content improves sinterability by promoting the formation of dense and uniform microstructures. Homogeneous mixing at the atomic scale facilitates an even distribution of calcium and magnesium, which is essential for achieving consistent mechanical and thermal properties in the final product [142]. In terms of chemical stability, higher MgO content, particularly when combined with functional additives such as TiO2, leads to the development of protective phases like magnesium silicate hydrates, hydrotalcite, or calcium titanate (CaTiO3), which significantly enhance hydration resistance and long-term durability [19]. Furthermore, by carefully balancing the MgO/CaO ratio and additive content, it is possible to engineer multiphase microstructures that provide both early mechanical strength (primarily from CaO hydration) and extended service life (through the slower, stabilizing hydration of MgO) [143]. While the addition of MgO and functional oxides offers clear benefits, certain limitations must be considered to ensure optimal performance. Excessive MgO content may result in the presence of unreacted or poorly bonded particles within the microstructure, which can reduce mechanical strength and compromise reactivity [144]. Therefore, careful optimization of the MgO/CaO ratio is essential to balance densification, hydration resistance, and durability. Similarly, additives such as TiO2 are known to enhance hydration resistance and mechanical integrity by promoting the formation of protective ceramic phases; however, their effectiveness is highly dependent on proper dosage, as excess amounts may disrupt phase equilibrium or lead to undesirable microstructural effects [19].

Ensuring high purity dolomite and magnesite is crucial for industrial applications. Advanced flotation techniques, especially with selective depressants and collectors, are the primary methods for removing siliceous and ferrous impurities, resulting in consistent and high quality feedstock.

Recent advances in flotation-based purification techniques have significantly improved the selective separation of dolomite from magnesite, a critical step for obtaining high purity raw materials in refractory production. One major innovation involves the use of modern selective depressants such as EDTMPA, DTPMP, HEDP, Na2ATP, EGTA, sesbania gum, gellan gum, and tannin. These compounds preferentially bind to calcium ion sites (Ca2+) on the dolomite surface, increasing its hydrophilicity and thereby suppressing its floatability. This facilitates more effective separation from magnesite [121,145,146,147,148,149,150,151]. Many of these depressants are also biodegradable and environmentally friendly, aligning with green processing goals.

Advancements in collector agents such as -chloro-oleate acid and DBDP have enhanced the floatability of target minerals. Depending on the process design, these collectors can selectively increase either dolomite or magnesite recovery [152,153,154,155]. Additionally, physical enhancement methods like ultrasonic treatment have shown to improve flotation efficiency by increasing mineral surface roughness and reagent adsorption, resulting in better separation performance and cleaner product quality [156,157].

Beyond improvements in separation technologies, these advancements align with a broader shift in the refractory industry toward sustainability and resource efficiency. Current research and industrial practice emphasize energy efficient processing, the recycling of spent refractory materials, and the integration of circular economy principles. Key strategies include the valorization of industrial waste, the use of secondary raw materials from demolition or process residues, and the optimization of thermal treatments, all of which contribute to reducing the environmental footprint and improving long term resource security.

Several energy-saving measures have been identified to reduce the high energy consumption and CO2 emissions associated with MgO-CaO production, especially in fusion processes above 2000 °C. Upgrading to larger and more efficient electric arc furnaces—such as replacing 1600 kVA units with 3000 kVA models—can significantly lower unit power consumption in fused magnesia production [158]. Advanced process designs, such as transport bed flash calcination, utilize staged preheating and product cooling to recover heat, achieving energy efficiencies up to 66.8%, almost double that of conventional reverberatory furnaces [159].

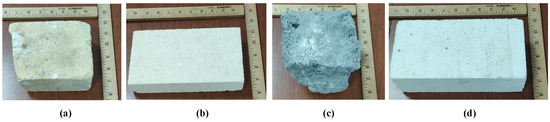

Switching to alternative energy sources, such as integrating renewable electricity, nuclear power, or hydrogen, can further reduce the carbon footprint, with nuclear and hydrogen offering substantial reductions compared to coal or natural gas [160]. Partial substitution of fossil fuels with biomass in calcination can also cut CO2 emissions by up to 38% for dead-burned magnesia (DBM) [161]. Additional strategies include improved furnace insulation, heat recovery from exhaust gases, and the adoption of CO2 capture technologies, all of which contribute to making magnesia production more compatible with circular economy and sustainability goals [162]. While process optimization reduces the energy intensity of magnesia production, extending the material life cycle through recycling further enhances its overall environmental performance. In this context, the recycling of spent refractories is gaining momentum in the refractory industry as a response to growing environmental concerns, raw material supply limitations, and rising production costs. Despite this progress, recycled materials currently meet only about 7% of the total demand for refractory raw materials, largely due to quality variability and the lack of widespread high-value recycling applications [32,163]. Figure 10 illustrates examples of typical refractory waste materials from various industrial sectors. These spent materials form the basis for recycling strategies aimed at reducing environmental impact and raw material dependency. Nevertheless, closed loop recycling where used refractories are reintroduced into the production of new refractory products is emerging as a promising strategy to enhance resource efficiency and reduce dependence on virgin materials.

Figure 10.

Refractory waste materials from various applications: (a) Highly sintered chromite brick used in kiln lining; (b) corundum brick for combustion chamber; (c) MgO–C refractory brick after severe attack by molten slag in blast furnace conditions; (d) magnesia–zirconia brick for smelting furnaces.

Recent innovations such as electrodynamic fragmentation have shown potential in producing high-purity recycled fractions that retain comparable performance to conventional raw materials [164]. These methods enable effective separation and recovery of valuable phases, contributing to lower energy consumption and carbon emissions during processing. Supporting this, life cycle assessment (LCA) studies indicate that the reuse and recycling of refractory waste can lead to savings of approximately 0.54 tonnes of CO2-equivalent and 3 GJ of non-renewable energy per tonne of waste processed. Among the available options, direct reuse of materials offers the most significant environmental benefits [25]. Together, these developments position recycling and circular economy practices as central components of future sustainable refractory production systems.

4. Modification with Nanostructured Additives

The modification of MgO-CaO refractories with nanostructured additives has proven to be a highly effective approach for improving hydration resistance, structural integrity, and overall performance in aggressive environments.

4.1. Assessment of Additives

Commonly investigated additives include ZnO, ZrO2, TiO2, Fe2O3, and Al2O3, as well as spinel-forming compounds such as MgAl2O4 (spinel) and FeAl2O4 (hercynite) [113,165,166,167,168,169,170]. Beyond conventional additives, recent research has expanded the range of functional oxides to include MnO and SiO2, which offer additional advantages in phase stability, densification, and surface engineering [171,172,173,174]. From a thermodynamic perspective, MnO promotes the formation of MnCr2O4 spinel by shifting equilibrium away from Cr2O3, enabling selective chromium enrichment and improving slag interactions in steelmaking environments [175,176]. Simultaneously, MnO and SiO2 serve as effective network modifiers, depolymerizing silicate structures, lowering melt viscosity, and promoting densification during high-temperature processing [176,177,178]. These effects are crucial for optimizing the microstructure and minimizing porosity in advanced ceramics and refractories. Cr2O3 also demonstrates excellent thermodynamic stability in contact with Ga2O3 up to 600 °C, supporting its use in high temperature electronics and corrosion-resistant coatings [179,180]. Moreover, surface-engineered SiO2 and MnO2 core shell composites have shown excellent results in polishing systems due to their combined chemical and mechanical effects [181].

Additional studies have explored the use of B2O3 to form dense glassy phases that reduce moisture permeability; kaolin as a source of aluminosilicates promoting in situ spinel formation [182,183]; Si3N4 to enhance hydrophobicity and reduce wetting behavior; and MgSiO3 (enstatite) to generate intergranular protective barriers [184,185].

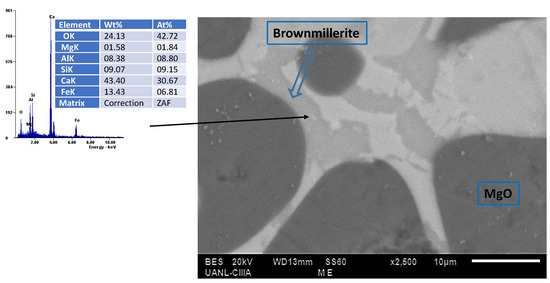

4.2. Impact of Nanostructured Additives on Performance Parameters

- Hydration Resistance

In conjunction with compositional advances, hydration resistance is primarily governed by the formation of protective phases at grain boundaries such as spinels, perovskites, and dense oxide layers which encapsulate reactive CaO and MgO, thereby reducing water exposure and limiting degradation. Nano-additives containing trivalent and tetravalent cations (Zr, Al, Ti) form solid solutions or low-melting compounds that densify grain boundaries and block moisture ingress. Sol-derived oxides like alumina sol enhance bonding and protective layer density, while hybrid systems such as Al–TiB2 suppress the formation of hydratable phases and improve thermal shock resistance. These microstructural modifications including grain encapsulation, densification, and reduced porosity—are essential to the durability and performance of advanced refractory systems [15,186,187,188]. In addition, Figure 11 provides direct SEM microstructural evidence supporting this mechanism. The image corresponds to an experimental formulation containing MgO-CaO with the addition of microparticles of hercynite (FeAl2O4), which incorporates trivalent Fe ions. During high-temperature sintering, this raw material reacts with CaO to form brownmillerite (), a low-melting phase that wets the grain boundaries between lime and magnesia. This phase behaves as a liquid-like collar surrounding the grains, promoting densification and reducing porosity and intergranular defects within the refractory matrix. Consequently, the formation of such continuous boundary films enhances the material’s resistance to hydration by limiting the penetration of moisture and blocking reactive sites associated with free CaO.

Figure 11.

SEM image of a MgO-CaO refractory showing the brownmillerite phase (), formed by the reaction of free lime () with the added hercynite (), encapsulating magnesia grains ().

- Mechanical Performance

Nanostructured additives significantly enhance mechanical performance. By refining grain size, increasing bulk density, and improving intergranular bonding, these additives contribute to tougher, more resilient microstructures. In both metallic and ceramic matrices, nanoparticles such as Y-Zr-O, Fe3O4, or graphene oxide disperse uniformly to form dense structures that resist crack propagation and improve compressive and flexural strength. These enhancements are attributed to grain boundary optimization, Orowan strengthening, and the formation of stable second phases. Combined with the densification and encapsulation mechanisms previously described, these effects establish nanostructured additives as powerful tools for engineering multifunctional materials with high durability, hydration resistance, and mechanical robustness [189,190,191,192,193,194,195].

- Thermal Behavior

Thermal performance is likewise improved through additive-induced phase engineering and microstructural control. The engineered formation of spinel and perovskite phases particularly when coupled with controlled porosity significantly enhances thermal shock resistance and reduces thermal conductivity. In magnesia-based refractories, in situ spinel formation creates fine, uniformly distributed pores that absorb thermal stress and inhibit crack propagation under cyclic heating. Similarly, perovskite structures, especially two-dimensional or high entropy variants, exhibit ultra-low thermal conductivity due to strong phonon scattering, lattice distortions, and defect engineering. These thermally insulating features, together with mechanical and hydration enhancements, position nanostructured additive systems as ideal candidates for high-performance applications exposed to extreme thermal cycling [196,197,198,199]. Overall, nanostructured additive engineering offers a promising route to tailor the microstructure and durability of magnesia–dolomite refractories, making them more suitable for demanding industrial applications where hydration and thermal stress are critical challenges.

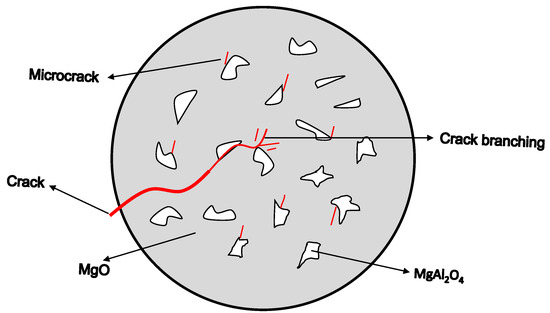

Spinel Phase Engineering for Thermal Shock Resistance

The enhancement of thermal shock resistance in ceramics through the engineered formation of spinel phases (notably MgAl2O4) is a well established phenomenon, supported by a robust body of research. Spinel phases, when introduced or formed in–situ within ceramic matrices, contribute to improved mechanical properties, reduced thermal conductivity, and increased resistance to crack propagation under cyclic heating and cooling. These improvements are attributed to mechanisms such as microcrack toughening, crack deflection, and the development of dense, well-bonded microstructures. Numerous studies have demonstrated that optimizing the content, distribution, and microstructure of spinel phases, often in combination with controlled porosity or secondary additives, leads to significant gains in thermal shock resistance across a variety of ceramic systems, including magnesia-based refractories, alumina spinel composites, and forsterite–spinel ceramics [200,201,202,203].

The primary mechanism by which spinel phases enhance thermal shock resistance is through microcrack toughening and crack deflection. The mismatch in thermal expansion coefficients between spinel and the matrix (magnesia or alumina) induces microcracks that dissipate thermal stress and hinder crack propagation [200,204,205], as shown in Figure 12. The formation of intergranular spinel phases also leads to a denser, more uniform microstructure, further improving resistance to thermal shock [169,200].

Figure 12.

Schematic of crack propagation. Modified from [206].

These mechanisms are foundational, but achieving optimal performance depends on further control over spinel content and distribution. Studies show that a well dispersed, interconnected spinel network maximizes crack deflection and energy absorption, while excessive or poorly distributed spinel can reduce mechanical strength [169,170,200]. The addition of secondary phases (rare earth oxides, aluminium titanate) or the use of nano-sized additives can further refine the microstructure and enhance performance [205].

Spinel phase engineering has been shown to improve thermal shock resistance in a wide range of ceramics, including magnesia–spinel refractories, alumina–spinel composites, forsterite–spinel ceramics, and zirconia-based systems [207,208,209]. The benefits are observed in both dense and porous ceramics, with microporous structures often providing additional thermal insulation and stress accommodation [210,211].

Controlled porosity, when combined with spinel formation, further enhances thermal shock resistance by accommodating thermal expansion and reducing thermal conductivity [196,203,210]. Additives such as rare earth oxides, aluminium titanate, and zirconia can synergistically improve both mechanical and thermal properties, as well as promote the formation of beneficial microstructures [169,211,212]. These synergies have been validated across a range of studies, as summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Selected studies on spinel engineering and its effect on thermal shock resistance in ceramic systems.

4.3. Industrial Applications and In-Service Performance

MgO-CaO refractory materials are widely used in industrial applications such as linings for furnaces, boilers, and cement kilns due to their high refractoriness, excellent resistance to basic slags, and suitability for clean steel production [13]. Their main advantages include stability in basic environments, high corrosion resistance, and relatively low production costs, making them attractive for industries seeking chrome-free alternatives with environmental and health benefits [214].

4.3.1. Steelmaking

MgO-CaO refractories are essential in the steel industry, particularly for lining Basic Oxygen Furnaces (BOFs), Electric Arc Furnaces (EAFs), and Argon Oxygen Decarburization (AOD) converters, due to their high resistance to basic slags, excellent thermal stability, and suitability for clean steel production [214]. Their use is driven by their ability to withstand chemically aggressive, high-temperature environments, offering advantages such as thermodynamic stability and cost-effectiveness compared to other basic refractories [215].

However, a main limitation has been their relatively low hydration resistance, which can lead to degradation during service. Recent advancements, such as the addition of nano- and micro-sized alumina, have significantly improved the physical and mechanical properties of MgO-CaO refractories, including bulk density, cold crushing strength, and thermal shock resistance, while also reducing their tendency to hydrate [216]. Innovative processing methods, like fused dolomite–magnesia co-clinkers, have further enhanced their chemical purity and resistance to corrosion, hydration, and thermal shocks, making them more reliable for demanding steelmaking applications [140,217]. Despite these improvements, the industry continues to seek ways to optimize their performance and extend their service life in steel production environments [65,218,219].

Refractories for Basic Oxygen Furnace (BOF) Units