Abstract

This paper develops a novel hybrid framework that integrates clustering-enhanced Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with stretching techniques to solve Markowitz’s quadratic portfolio optimization problem. The proposed approach avoids local optima traps that plague traditional optimization methods, while the stretching function modifications enhance the algorithm’s global search capabilities. The framework comprises four distinct algorithmic variants: a baseline SWARM PSO with stretching algorithm, and three clustering-enhanced extensions incorporating Hierarchical, K-means, and DBSCAN techniques. These clustering enhancements strategically group assets based on risk–return characteristics to improve portfolio diversification and risk management. Implementation in R enables comprehensive analysis of portfolio weight allocation patterns and diversification metrics across varying market structures. Empirical validation using daily price data from six major international stock market indices spanning January 2020 to December 2025 demonstrates the framework’s generalization capability in constructing buy-and-hold investment portfolios. The results reveal significant market-specific algorithmic effectiveness, with K-means variants achieving competitive efficacy in Eurostoxx and Belgian markets, DBSCAN demonstrating strong effectiveness in Chinese equity markets, Hierarchical clustering showing robust results in Indian market conditions, and the baseline SWARM algorithm exhibiting relative efficiency in French and Danish indices. Performance evaluation encompasses comprehensive risk-adjusted metrics, including Portfolio Return, Volatility, Sharpe Ratio, Calmar Ratio, and Value at Risk, providing portfolio managers with an adaptive, market-responsive optimization toolkit.

1. Introduction

Asset managers often encounter significant challenges when using Markowitz’s (1952) mean-variance optimization. This method can produce unstable portfolio weights that vary greatly from one period to the next and may result in algorithmic non-convergence, which underscores the complexities and unpredictabilities of real-world asset allocation, making the application of mean-variance optimization a nuanced task that requires careful consideration.

In this paper, I propose a new mean-variance Markowitz solver programmed in R, leveraging evolutionary strategies. To overcome key challenges in quadratic programming, particularly in avoiding local optima, I combine Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with stretching and clustering functions.

Among heuristic-based optimization methodologies, the Particle Swarm Optimizer is particularly appealing due to its biological inspiration, reflecting the dynamics of fish schools and bird flocks, as first introduced by Eberhart and Kennedy (1995). PSO is a method where solutions are represented as vectors in an n-dimensional space, known as particles. Each particle tracks its best-known position and the best overall found by the swarm, guiding its movement and velocity in iterations. The particles collaborate to explore the search space and find optimal solutions.

On the one hand, the “stretching” technique by Parsopoulos et al. (2001a) is incorporated into the Particle Swarm Optimizer (PSO) to overcome the issue of getting trapped in local minima, which can hinder its effectiveness in complex optimization tasks. The stretching technique uses a two-step transformation: first, it raises the objective function to reduce undesirable local minima, and then it stretches the neighborhood of the trapped point to convert a local minimum into a local maximum. This approach enhances the algorithm’s ability to escape local traps, improving its global optimization capabilities and making stretched PSO a more reliable tool for solving complex problems across various fields.

On the other hand, the clustering methodology represents another contribution. I apply various machine learning algorithms, including hierarchical clustering, K-means, and density-based clustering (DBSCAN). I extend PSO’s global search abilities to find optimal cluster centroids and apply function stretching to avoid local minima. By partitioning the search space or particle population, this original theoretical framework enhances both exploration and exploitation, leading to effective solutions for complex multi-modal optimization problems and unsupervised learning tasks.

The core contribution of this research to the field of financial optimization and portfolio management is the development of a novel algorithm that combines particle swarm optimization, stretching, and clustering techniques, implemented on the R platform. This algorithm will be rigorously tested using historical stock market data spanning six global indices from January 2000 to December 2025. I evaluate the performance of a buy-and-hold portfolio using various metrics, such as the Sharpe and Calmar ratios.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 contains a literature review of the latest developments in particle swarm optimization. Section 3 details the models with stretching and with clustering. Section 4 contains an empirical application dedicated to asset allocation. Section 5 concludes.

2. Theoretical Contributions to Particle Swarm Optimization: A Literature Review

The theoretical basis of PSO has evolved substantially since its introduction. Sengupta et al. (2018) surveyed its development, hybridization strategies, and convergence analysis, while Freitas et al. (2020) emphasized enhancements such as inertia weight and constriction factor to address stagnation in convergence. A comprehensive and useful review of meta-heuristics for portfolio optimization can be found in Erwin and Engelbrecht (2023).

Dynamic parameter adaptation plays a central role in boosting PSO’s performance. Zhan et al. (2009) proposed Adaptive PSO, enabling real-time detection of swarm states (e.g., exploration or convergence) to tune inertia and acceleration parameters accordingly. Yao et al. (2024) extended this by integrating adaptive inertia weights, reverse learning, Cauchy mutation, and Hooke–Jeeves local search, jointly enhancing convergence and escape from local optima.

To balance convergence and diversity, several structural PSO variants have emerged. Lin et al. (2025) segmented the swarm into subpopulations with customized learning rates and adaptive tuning, enabling local and global cooperation. Jiang et al. (2025) added chaotic initialization, adaptive inertia, multi-subpopulation coordination, and mutation, collectively preventing premature convergence in complex landscapes.

Multimodal and multi-objective tasks have spurred efforts to enhance PSO’s ability to capture multiple optima. Passaro and Starita (2008) combined PSO with dynamic k-means clustering to identify multiple optima in multimodal functions. Li et al. (2021) proposed a grid search-enhanced multi-population PSO combining clustering and spatial partitioning to maintain diverse Pareto sets and improve solution distribution.

In unsupervised learning, PSO has supported robust clustering. Huang (2011) paired PSO with Rough Set Theory to dynamically select the number of clusters, improving classifier accuracy. Zhang and Liu (2023) combined PSO with cloud theory and information entropy to boost feature selection and clustering on high-dimensional, imbalanced data. Verma et al. (2021) integrated fuzzy C-means with PSO for improved brain image segmentation, leveraging PSO’s global search to overcome local minima in medical data classification tasks. Hayashida et al. (2025) introduce ELPSO-C, an enhanced leader particle swarm optimization variant that uses agglomerative clustering to detect and control dimension-wise diversity, selectively reintroducing variation in stagnating dimensions to improve convergence and search performance on high-dimensional optimization problems.

PSO applications in financial portfolio management have evolved from basic optimization to sophisticated frameworks addressing real-world constraints. Chen et al. (2021) demonstrated PSO’s effectiveness in optimizing non-differentiable risk metrics, particularly the Sortino ratio, within large portfolio contexts where traditional gradient-based methods fail. Bulani et al. (2025) advanced this approach by integrating clustering methodologies with enhanced data preprocessing techniques, improving risk-adjusted returns across diverse asset classes and creating more robust optimization frameworks for complex financial environments. Lolic (2024) introduces two practical regularization enhancements to classical mean-variance optimization—one that constrains utility to reduce portfolio weight concentration, and another that resamples asset subsets—to produce more stable, diversified multi-asset portfolios with improved out-of-sample risk-adjusted returns relative to standard mean-variance optimization. Ntare et al. (2025) apply dynamic portfolio optimization and asset selection methods, including PSO, to examine diversification benefits and risk–return trade-offs when combining cryptocurrencies with highly correlated bank equities.

Domain-specific hybridizations expand PSO’s reach. Aguiar Nascimento et al. (2022) proposed a two-phase optimizer for Full Waveform Inversion using modified PSO with k-means for exploration, followed by the Adaptive Nelder–Mead method for local refinement. Ananthi et al. (2025) developed a metaheuristic for dynamic data streams via lion optimization and an exponential PSO variant, enhancing centroid initialization for real-time clustering. Yuan et al. (2024) propose a multi-robot task allocation approach that synergistically combines a constrained K-means++ clustering (to group tasks according to robot capacity) with particle swarm optimization (to assign clusters to robots and optimize task execution order), demonstrating improved collaborative efficiency over other heuristic methods in both simulation and real robot experiments.

Extensions of PSO through alternative swarm models continue to diversify the algorithmic toolkit. Niu et al. (2025) introduced a multi-objective Sand Cat Swarm Optimization with adaptive clustering, refining crowding distance and improving neighborhood modeling in multimodal contexts, underscoring the integrative potential of non-PSO swarm paradigms.

Hybrid PSO architectures fuse complementary strategies for expanded functionality. Niknam and Amiri (2010) combined fuzzy adaptive PSO, ant colony optimization, and k-means to reduce initialization sensitivity and improve clustering accuracy. Abubaker et al. (2015) introduced a hybrid of multi-objective PSO with simulated annealing, optimizing cluster validity metrics while mitigating stagnation. In another evolutionary framework, Muteba Mwamba et al. (2025) demonstrated the effectiveness of the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm III (NSGA-III) over the traditional mean-variance optimization method for financial portfolio management.

3. Model

The modelling setup includes five main components: (i) Ledoit and Wolf’s (2003) shrinkage estimator to estimate precisely the covariance matrix of assets; (ii) the particle swarm optimization with stretching for better search space exploration; (iii) hierarchical clustering for nested cluster structures; (iv) K-Means for data partitioning into fixed cluster numbers; and (v) Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise to identify clusters of different shapes and densities while managing outliers.

3.1. Quadratic Portfolio Optimization with Shrinkage Estimator

The integration of Markowitz’s (1952) seminal portfolio optimization framework with Ledoit and Wolf’s (2003) shrinkage estimator represents a sophisticated approach to addressing the fundamental challenges of modern portfolio theory in high-dimensional settings. This enhanced methodology combines the theoretical elegance of mean-variance optimization with advanced statistical techniques that mitigate the notorious instability of sample covariance matrices, particularly when the number of assets approaches or exceeds the number of observations.

3.1.1. Markowitz’s (1952) Portfolio Optimization

The classical mean-variance optimization framework, introduced by Markowitz (1952), revolutionized portfolio management by formalizing the intuitive concept that investors seek to maximize expected returns while minimizing risk. This foundational approach treats portfolio construction as a quadratic optimization problem that explicitly balances the trade-off between expected return and variance, providing a mathematically rigorous foundation for rational investment decision-making.

Let be the set of raw individual stocks within an index, for which I compute the log-returns . The classical mean-variance optimization problem is formulated as:

This optimization framework seeks to determine the optimal portfolio weights that minimize portfolio variance while satisfying two fundamental constraints. The objective function represents the portfolio variance, where is the covariance matrix of asset returns that captures both individual asset volatilities and cross-asset correlations. The quadratic form elegantly encapsulates the risk contribution of each asset and the diversification benefits arising from imperfect correlations between assets.

The first constraint, , ensures that the portfolio achieves a predetermined target expected return, where is the vector of expected returns for each asset and represents the investor’s desired portfolio return. This constraint transforms the optimization problem from a simple variance minimization to a constrained optimization that explicitly considers the return-risk trade-off. The second constraint, , where is a vector of ones, ensures that the portfolio weights sum to unity, representing the requirement that the entire investment capital is allocated across the available assets.

3.1.2. Ledoit and Wolf’s (2003) Shrinkage Estimator

The practical implementation of Markowitz’s framework encounters significant challenges when dealing with sample covariance matrices, particularly in high-dimensional settings where the number of assets is large relative to the number of observations. Ledoit and Wolf (2003) addressed this fundamental limitation by developing a shrinkage estimator that systematically combines the sample covariance matrix with a structured target matrix, effectively reducing estimation error through a principled bias-variance trade-off.

The Ledoit and Wolf’s (2003) shrinkage estimator of the covariance matrix is defined as:

This shrinkage formulation represents a convex combination of two distinct covariance estimators, where is the sample covariance matrix computed from historical return data, and is the single-index model covariance matrix that serves as a structured target. The sample covariance matrix is unbiased but exhibits high variance, particularly when the ratio of assets to observations is large, leading to unstable portfolio weights and poor out-of-sample performance. Conversely, the structured target introduces bias but substantially reduces variance by imposing a parsimonious structure that reflects economic intuition about asset return relationships.

The shrinkage intensity parameter determines the optimal balance between bias and variance, with corresponding to the sample covariance matrix and representing complete reliance on the structured target. The genius of the Ledoit–Wolf approach lies in the analytical derivation of the optimal shrinkage intensity that minimizes the expected squared Frobenius norm of the estimation error, providing a theoretically grounded and computationally efficient solution to the covariance estimation problem.

The optimal shrinkage intensity is determined by minimizing the expected squared Frobenius norm of the estimation error:

This optimal shrinkage intensity is computed using three fundamental components that capture different aspects of the estimation problem. The parameter represents the asymptotic variance of the sample covariance matrix elements, quantifying the uncertainty inherent in the sample-based estimation:

The parameter measures the asymptotic covariance between the sample covariance matrix and the structured target, reflecting the extent to which the target matrix aligns with the sample-based estimates:

The parameter represents the squared Frobenius norm of the difference between the structured target and the true population covariance matrix, quantifying the bias introduced by the target structure:

These components involve the -elements and of matrices and , respectively, and representing the -element of the true population covariance matrix . The parameter T denotes the number of observations used to compute the sample covariance matrix, while AsyVar and AsyCov represent asymptotic variance and covariance operators that capture the large-sample behavior of the estimators.

3.1.3. Enhanced Portfolio Optimization

The integration of Ledoit and Wolf’s (2003) shrinkage estimator into Markowitz’s (1952) framework creates a robust portfolio optimization approach that maintains the theoretical elegance of mean-variance optimization while addressing the practical limitations of sample covariance matrices. This enhanced formulation systematically improves portfolio performance by reducing estimation error and increasing the stability of optimal portfolio weights.

Incorporating the Ledoit and Wolf’s (1952) shrinkage estimator into the Markowitz’s (1952) framework yields:

This enhanced formulation preserves the essential structure of the Markowitz optimization problem while substituting the problematic sample covariance matrix with the shrinkage estimator ΣLW. The resulting optimization problem maintains the same constraints and objective function structure, ensuring compatibility with existing portfolio optimization algorithms and theoretical results, while significantly improving the numerical stability and out-of-sample performance of the resulting portfolios.

The shrinkage estimator effectively balances the bias-variance tradeoff inherent in covariance estimation: the structured target provides regularization that reduces variance and improves numerical conditioning, while the sample covariance matrix preserves data-specific covariance patterns and maintains a connection to the observed return dynamics. The closed-form solution for the optimal shrinkage intensity ensures consistency under large-dimensional asymptotics, providing theoretical guarantees for the estimator’s performance as both the number of assets and observations increase.

This integration represents a significant advancement in portfolio optimization methodology, combining the foundational insights of modern portfolio theory with cutting-edge statistical techniques to address the practical challenges of high-dimensional portfolio construction. The resulting framework maintains the intuitive appeal and theoretical rigor of the Markowitz approach while providing substantially improved empirical performance in realistic investment settings.

3.2. PSO Dynamics with Stretching Function

3.2.1. Vanilla PSO

Particle swarm optimization operates through a population-based metaheuristic that simulates the collective behavior of bird flocking or fish schooling to solve optimization problems. The algorithm maintains a swarm of particles, where each particle represents a potential solution that moves through the search space by dynamically adjusting its position based on its own experience and the collective knowledge of the swarm.

According to Eberhart and Kennedy (1995), the fundamental mechanism governing particle movement consists of two sequential update equations that define how each particle i evolves from iteration k to iteration . The first equation updates the velocity vector, which determines the direction and magnitude of the particle’s movement:

This velocity update equation comprises three distinct components that balance exploration and exploitation. The first term, , represents the inertia component, where the inertia weight w controls the influence of the particle’s previous velocity direction. A higher inertia weight promotes global exploration by maintaining the particle’s momentum, while a lower value encourages local exploitation by reducing the impact of previous movement patterns.

The second term, , constitutes the cognitive component that attracts each particle toward its personal best position . This term represents the particle’s individual learning capability, where is the cognitive acceleration coefficient that determines the strength of attraction toward the particle’s historical best performance. The random number introduces stochastic variation that prevents deterministic behavior and maintains diversity in the search process.

The third term, , represents the social component that draws particles toward the global best position discovered by the entire swarm. The social acceleration coefficient controls the intensity of this collective attraction, while the random number ensures probabilistic movement toward the global optimum. This social learning mechanism enables information sharing among particles and facilitates convergence toward promising regions of the search space.

Following the velocity update, the second equation updates the particle’s position by integrating the newly computed velocity:

This position update represents a simple Euler integration scheme that translates the particle’s current location by the velocity vector, effectively moving the particle through the N-dimensional search space. The position vector represents the candidate solution, which in portfolio optimization contexts corresponds to the portfolio weights across N assets.

The algorithm maintains memory structures for each particle, including the personal best position , which stores the best solution found by particle i throughout its search history, and the global best position , which represents the best solution discovered by any particle in the swarm. These memory components enable the algorithm to retain valuable information and guide future search directions based on accumulated experience.

The velocity vector serves as the primary mechanism for exploration and exploitation, encoding both the direction and speed of particle movement. The interplay between the inertia weight , acceleration coefficients , and random numbers creates a dynamic balance between diversification (exploring new regions) and intensification (exploiting promising areas), enabling the swarm to efficiently navigate complex optimization landscapes while avoiding premature convergence to suboptimal solutions.

3.2.2. Function Stretching Technique for PSO

The Function Stretching technique represents a sophisticated two-stage transformation method designed to help Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) escape from local minima by systematically modifying the objective function landscape. This approach by Parsopoulos et al. (2001a), Parsopoulos et al. (2001b), Parsopoulos and Vrahatis (2002) and Parsopoulos and Vrahatis (2004) is particularly valuable because it addresses one of the most fundamental challenges in global optimization: the tendency of search algorithms to become trapped in suboptimal solutions.

Conceptual Foundation

The core philosophy behind Function Stretching lies in the strategic manipulation of the objective function’s topology. Rather than attempting to modify the search algorithm itself, this technique transforms the problem landscape in a way that eliminates problematic local minima while preserving the global optimum. The transformation is applied immediately after PSO has converged to a local minimum , essentially “reshaping” the function to create new pathways toward the global solution.

First-Stage Transformation: Elevation of Local Minima

The first transformation stage is designed to eliminate local minima that possess higher function values than the detected local minimum . This is achieved through the following transformation:

The mathematical structure of this transformation is carefully constructed to achieve specific objectives. The term represents the Euclidean distance from any point to the detected local minimum . This distance component ensures that the transformation’s effect is spatially localized, with the strongest impact occurring near the problematic local minimum.

The sign function serves as a selective filter that determines which regions of the function landscape should be modified. When , the sign function returns +1, and when combined with the +1 constant, produces a coefficient of 2. This means that points with higher function values than the local minimum receive the full strength of the transformation. Conversely, when , the sign function returns −1, and the combined coefficient becomes 0, leaving these regions completely unaffected.

The parameter controls the intensity of this elevation effect. A larger value results in more dramatic elevation of the problematic regions, while a smaller value produces a gentler transformation. The choice of must balance effectiveness in eliminating local minima with maintaining the overall function structure.

The geometric interpretation of this transformation is that it “lifts up” all regions of the function that have higher values than the detected local minimum, with the lifting effect being proportional to the distance from . This creates a cone-like elevation centered at the local minimum, effectively making previously attractive local minima become less appealing to the optimization algorithm.

Second-Stage Transformation: Neighborhood Stretching

The second transformation stage focuses on the immediate neighborhood of the detected local minimum, further discouraging the algorithm from remaining in this region:

This transformation builds upon the result of the first stage, , and applies an additional modification specifically designed to “stretch” the neighborhood around upward. The hyperbolic tangent function is crucial here because it provides a smooth, bounded transformation that prevents the function from becoming unbounded while still creating significant local changes.

The argument to the tanh function, , represents the difference between the current function value (after first-stage transformation) and the transformed value at the local minimum. The parameter controls the steepness of this hyperbolic tangent, effectively determining how rapidly the stretching effect transitions from its minimum to maximum values.

The same selective mechanism from the first stage, , is employed here to ensure that only points with function values higher than the original local minimum are affected by this stretching operation. The parameter scales the overall magnitude of the stretching effect.

The combined effect of this second transformation is to create a smooth, upward-stretching distortion in the neighborhood of the local minimum. This transformation converts the former local minimum into a local maximum, making it highly unattractive to the optimization algorithm while maintaining smooth transitions to surrounding regions.

Preservation of Global Structure

A critical property of both transformation stages is their selective nature regarding the global optimum and other local minima with lower function values. Since the transformations only affect regions where , any local minimum with a lower function value than remains completely unaltered. This includes the global minimum, which by definition has the lowest function value of all points in the search space.

The sign function mechanism mathematically guarantees this preservation property. When , the term evaluates to either 0 or 1, but in the critical case where , it becomes 0, completely nullifying the transformation effect. This ensures that the global optimum’s basin of attraction is preserved and potentially even enhanced relative to the eliminated local minima.

Implementation in Stretched PSO (SPSO)

The Function Stretching technique is integrated into PSO through a monitoring and transformation protocol. The algorithm initially applies standard PSO to the original objective function . A convergence detection mechanism continuously monitors the swarm’s progress, identifying when the algorithm has stagnated at a local minimum .

Upon detection of local minimum convergence, the algorithm applies the two-stage transformation to create the new objective function . The PSO is then reinitialized with the same swarm configuration but now optimizes the transformed function. This process can be repeated multiple times if the algorithm encounters additional local minima, creating a sequence of progressively transformed functions that systematically eliminate problematic regions of the search space.

This Function Stretching approach represents a significant advancement in hybrid optimization strategies, combining the population-based search capabilities of PSO with intelligent landscape modification techniques to achieve more reliable global optimization performance.

3.2.3. Comparison with Traditional Quadratic Solvers

Particle Swarm Optimization with Function Stretching offers practical advantages over conventional quadratic programming in both optimization robustness and computational efficiency (see Table A1 in the Appendix A to save space).

Namely, it enhances global optimization in non-convex portfolio settings by altering the objective landscape to suppress poor local minima while preserving global optima. This matters in real-world scenarios involving transaction costs and market frictions. Through an adaptive inertia weight , the swarm balances exploration and exploitation. Parallel evaluation of particles accelerates convergence in high-dimensional problems. Unlike traditional methods, PSO naturally handles various constraints without reformulation and remains stable even with noisy or ill-conditioned covariance input.

3.2.4. Pseudo-Code for PSO with Stretching

In Table A3 (see the Appendix A to save space), the algorithm begins by estimating a robust shrinkage covariance matrix using the Ledoit–Wolf procedure to mitigate instability in high dimensions. It generates diverse random portfolio weights and evaluates portfolio risk via . Function stretching transforms the landscape to avoid local optima, guiding the swarm toward the global solution. Particle positions and velocities are iteratively updated until convergence or stopping criteria are met. This hybrid method efficiently combines shrinkage estimation’s stability with PSO’s global search capacity to produce robust portfolios even with limited or noisy data.

3.3. Hierarchical Clustering of Assets as an Input to Markowitz Portfolio Optimization

3.3.1. Hierarchical Clustering of Assets

Hierarchical clustering transforms the enhanced covariance matrix into a tree structure that reveals natural groupings of financial assets. By using the Ledoit and Wolf’s (2003) shrinkage estimator’s correlations, it identifies assets with similar risk–return profiles, aiding in better portfolio construction and risk management.

Given a shrunk covariance matrix from Ledoit and Wolf (2003), I define a proximity matrix for hierarchical clustering:

where are elements of .

The proximity matrix measures dissimilarity between asset pairs based on their volatilities and correlations. Each element represents the distance between assets i and j, calculated from the variance of their return differences. Highly correlated assets with similar volatilities have smaller distances, while uncorrelated or negatively correlated assets have larger distances. This metric includes the individual variances of assets i and j (diagonal elements and ) and their covariance (off-diagonal element ). Thus, assets with high positive correlation and similar risk profiles are closer together, while those with low correlation or differing risks are farther apart.

This metric satisfies three fundamental mathematical properties that ensure its validity as a distance measure:

- (1)

- (non-negativity);

- (2)

- (identity);

- (3)

- (ultrametric inequality).

The non-negativity property states that distances are either positive or zero, meaning dissimilarity cannot be negative. The identity property requires that the distance between an asset and itself is zero, while distances between different assets are positive. The ultrametric inequality is a stricter form of the triangle inequality, supporting hierarchical clustering and allowing for a meaningful dendrogram.

3.3.2. Hierarchical Clustering Scheme (HCS)

Hierarchical clustering forms a tree-like structure of asset relationships by merging the most similar clusters using Johnson’s (1967) algorithm for efficiency:

- (1)

- Initialize clusters: ;

- (2)

- At each step k, merge clusters A and B with minimal ultrametric distance:

- (3)

- Update proximity matrix by removing rows/columns for A and B, adding new row/column for .

The algorithm begins with each asset as its own cluster, denoted as . During each iteration k, it identifies the two clusters A and B with the smallest inter-cluster distance, defined by . This complete linkage criterion promotes compact clusters by limiting the maximum distance between merged assets.

This method is effective for financial applications, as it results in stable clusters that reflect similar risk traits while preventing outliers from distorting the results. After each merge, the proximity matrix is updated by removing the merged clusters and adding a new entry for the combined cluster , ensuring efficient calculations for future iterations.

The hierarchical clustering creates a sequence of nested partitions , which allows analysts to observe asset relationships from individual to collective groupings. This representation aids in tactical asset allocation and portfolio construction, and visualizing it with a dendrogram reveals important correlations and groupings within the asset universe.

In practice with R, I can adjust the number of clusters to ensure multiple stocks are included in each. The ideal number of clusters varies with the total stock count, whether it is 20, 30, 40, 50, or 100. I can provide detailed information on stock assignments for improved understanding of the clusters.

3.3.3. PSO with Stretching for Cluster-Aware Optimization

Cluster-Constrained Markowitz Problem

The cluster-constrained Markowitz formulation improves classical mean-variance optimization by incorporating hierarchical clustering constraints. With m clusters , it aims to minimize portfolio variance while targeting specific expected returns and ensuring cluster-level diversification. This method mitigates concentration risk by limiting the total weight of assets in each cluster. For m clusters identified via HCS:

The objective is to minimize portfolio variance using the Ledoit–Wolf shrinkage covariance estimator for better estimation accuracy in portfolio optimization. I have a target expected return , a constraint that portfolio weights sum to one, and a limit on asset weights within each cluster based on a risk budget to enhance diversification.

To tackle this cluster-constrained portfolio optimization, I apply particle swarm optimization (PSO) with function stretching. This approach navigates the complex constraints of cluster diversification and mitigates issues of local optima, common in traditional optimization due to asset correlations.

Cluster-Guided Stretching

The stretching mechanism improves convergence by modifying the objective function’s landscape during stagnation. This is particularly beneficial in portfolio optimization, where diverse asset clusters lead to complex, multi-modal objective functions with numerous local optima. The stretching transformation is applied according to cluster membership data to align with the asset universe’s structure. When the optimization algorithm hits a local minimum at iteration , the objective function is recalibrated using the following formulation:

The augmented objective function integrates the original function with a stretching term based on the distance to a stagnation point . The parameter controls the stretching intensity, while adjusts its sensitivity to proximity to the stagnation point. A hyperbolic tangent function provides a smooth stretching effect, preventing optimization landscape distortion.

The neighborhood is defined by cluster memberships, so the stretching is applied only to solutions within the same cluster as the stagnation point. The indicator function restricts stretching to this area, ensuring the optimization process remains intact while exploring new allocation strategies linked to market segments.

3.3.4. Pseudo-Code for Hierarchical Cluster-Guided PSO with Stretching

In Table A4 (see the Appendix A to save space), the pseudo-code uses hierarchical clustering and particle swarm optimization to enhance portfolio construction within realistic constraints. It also overcomes traditional mean-variance limitations by resorting to the stretching function, leading to better asset diversification through cluster-based constraints and metaheuristic techniques.

3.3.5. Computational Advantages

The hierarchical clustering approach with particle swarm optimization significantly improves high-dimensional portfolio optimization by enhancing efficiency and solution quality through dimensionality reduction and regularized covariance estimation (see Table A2 in the Appendix A to save space).

The hierarchical clustering component reduces optimization dimensionality from to , where m is the number of clusters. This significant reduction eases the computational burden of calculating covariance matrices in large-scale portfolio optimization and groups assets with similar risk–return profiles. Implementing Ledoit–Wolf shrinkage enhances covariance matrix estimation, addressing substantial errors typical in high dimensions and stabilizing clustering performance, particularly in volatile markets.

The particle swarm optimization (PSO) framework, with function stretching, effectively navigates local minima within the complex optimization landscape imposed by cluster constraints. Unlike traditional gradient-based methods, PSO explores the solution space more effectively, avoiding local optima.

This hybrid approach combines robust shrinkage estimators, structured hierarchical clustering, and global PSO optimization, tackling various computational challenges to improve portfolio management efficiency and effectiveness.

3.4. K-Means Clustering of Assets as an Input to Markowitz Portfolio Optimization

3.4.1. K-Means

K-means clustering represents a fundamental unsupervised learning technique that partitions the asset universe into distinct groups based on similarity measures (Likas et al., 2003). Given K clusters with centroids , the K-means objective seeks to minimize the total within-cluster sum of squares, effectively creating compact and well-separated clusters:

This objective function balances the dual goals of minimizing intra-cluster variance while maximizing inter-cluster separation. In this formulation, represents the set of indices for points assigned to cluster k, and denotes the centroid of cluster k. The optimization simultaneously determines both the cluster assignments and the optimal centroid positions, making K-means a particularly challenging non-convex optimization problem.

3.4.2. Distance Metrics

The choice of distance metric significantly influences the clustering structure and the resulting portfolio composition. The standard Euclidean distance serves as the default distance metric used in K-means clustering:

This metric assumes that all dimensions contribute equally to the similarity measure, which may not always be appropriate for financial data, where certain risk factors or return characteristics may be more significant than others. The Euclidean distance implicitly creates spherical clusters, which can be limiting when dealing with assets that exhibit non-spherical correlation structures.

3.4.3. K-Means Clustering Scheme (KCS)

The K-means clustering scheme employs Hartigan and Wong’s (1979) algorithm through an iterative refinement process that alternates between cluster assignment and centroid update steps. This algorithm provides a computationally efficient approach to solving the otherwise intractable K-means optimization problem. First, the algorithm initializes cluster centroids as , typically through random initialization or more sophisticated methods such as K-means++. At each iteration t, the algorithm assigns each asset i to the nearest cluster according to:

This assignment step ensures that each asset belongs to exactly one cluster, creating a hard partitioning of the asset universe. Subsequently, the algorithm updates centroids by computing cluster means:

The centroid update step repositions each cluster center to the geometric mean of its assigned points, minimizing the within-cluster sum of squares for the current assignment. The resulting KCS converges to a partition that represents a local minimum of the within-cluster sum of squares objective function.

3.4.4. K-Means Constrained Markowitz Problem

The integration of K-means clustering into the Markowitz framework creates a novel constrained optimization problem that incorporates structural information about asset relationships.

For K clusters identified via KCS, the constrained optimization problem becomes:

This formulation extends the classical mean-variance optimization by introducing cluster-level constraints that prevent excessive concentration within any single asset group. Here, represent the K-means cluster-level risk budgets, which can be determined through risk budgeting principles or regulatory requirements. These constraints ensure that the optimization process respects the underlying asset structure identified through clustering, potentially leading to more stable and interpretable portfolio allocations.

3.4.5. PSO with Stretching for K-Means Cluster-Aware Optimization

The incorporation of particle swarm optimization with stretching techniques addresses the computational challenges associated with solving the constrained K-means Markowitz problem. For each particle p representing portfolio weights , the particle swarm optimization algorithm updates velocities and positions according to:

This swarm-based approach combines local and global search capabilities, where particles explore the feasible space while sharing information about promising regions. In this formulation, represents the projection operator that enforces K-means cluster constraints and budget constraints, ensuring that all generated solutions remain feasible throughout the optimization process.

3.4.6. K-Means Cluster-Guided Stretching

The stretching technique provides a sophisticated mechanism for escaping local minima by temporarily modifying the objective function landscape. When local minima occur at iteration , the algorithm applies a stretching technique defined by:

This formulation adds a repulsive force around the current local minimum, encouraging the search process to explore alternative regions of the solution space. Here, is defined via K-means cluster memberships, ensuring that the stretching effect respects the underlying asset structure. The parameters control the magnitude and range of the stretching effect, while is the indicator function that activates the stretching only within the relevant cluster neighborhood.

3.4.7. Portfolio Insights

K-means clustering enhances portfolio analysis by identifying asset groupings that reveal correlations often masked by individual asset weights. It allows for better segmentation based on risk–return profiles, helping portfolio managers evaluate the contributions of different asset classes to overall risk and return.

This method also highlights concentration risks from over-weighted similar assets, informing diversification strategies for a more balanced allocation. Additionally, it supports effective risk budgeting and portfolio rebalancing by pinpointing reallocations needed as asset characteristics change. Clustering further improves factor exposure analysis by grouping assets with similar sensitivities, ensuring thorough exposure to systemic risk.

3.4.8. Pseudo-Code for K-Means Cluster-Guided PSO with Stretching

In Table A5 (see the Appendix A to save space), the pseudo-code uses K-means clustering to group stocks into homogeneous clusters based on return patterns, reducing the dimensionality of the portfolio optimization problem. The cluster weights are then determined using an enhanced particle swarm optimization algorithm with adaptive stretching transformations and time-varying parameters to maximize the Sharpe ratio, before distributing the optimal weights proportionally to individual stocks within each cluster.

3.5. DBSCAN Clustering of Assets as an Input to Markowitz Portfolio Optimization

The DBSCAN algorithm requires two main parameters for effective clustering (Khan et al., 2014). The first parameter is (Eps), which represents the neighborhood radius that defines the maximum distance between two points for them to be considered neighbors. The second parameter is MinPts, which specifies the minimum number of points required to form a dense region or cluster.

Parameter selection can be guided by portfolio characteristics, the desired granularity of clusters, and domain expertise in financial markets. These considerations help determine appropriate values that align with the specific characteristics of the financial data being analyzed.

3.5.1. Core Concepts

-Neighborhood

The -neighborhood of point is defined as the set of all points within the specified radius distance. This concept is mathematically expressed as:

This equation captures all points in the dataset X that are within distance from the reference point .

Core Point

A point is classified as a core point when it satisfies specific density requirements. The mathematical condition for a core point is:

This means that a point becomes a core point if the number of points in its -neighborhood is at least MinPts, indicating sufficient local density to anchor a cluster.

Directly Density-Reachable

A point is directly density-reachable from when it satisfies two simultaneous conditions. The mathematical formulation is:

This relationship establishes a direct connection between points based on proximity and the core point status of the reference point.

Density-Reachable

A point is density-reachable from when there exists a chain of points connecting them through direct density-reachability. The formal definition requires a sequence such that:

This transitive relationship allows points to be connected through intermediate core points, extending the reach of cluster formation beyond immediate neighborhoods.

Density-Connected

Two points and are density-connected when they can both reach a common point through density-reachability. The mathematical condition states:

This symmetric relationship forms the foundation for grouping points into the same cluster, even when they may not be directly reachable from each other.

DBSCAN Algorithm

Given parameters (neighborhood radius) and MinPts (minimum points), the DBSCAN objective focuses on identifying density-based clusters by grouping points that are closely packed together. The optimization problem can be formulated as:

In this formulation, represents the set of indices for points assigned to cluster k, and defines the -neighborhood of point .

Distance Metrics

The default distance metric used in DBSCAN is the standard Euclidean distance. This metric is mathematically expressed as:

This norm provides a natural measure of similarity between points in the feature space.

3.5.2. DBSCAN Clustering Scheme (DCS)

The DBSCAN clustering scheme follows the algorithm developed by Ester et al. (1996) and proceeds through several systematic steps. Initially, for each point , the algorithm determines whether it qualifies as a core point using the criterion:

Subsequently, for each core point , the algorithm creates a cluster by identifying all density-reachable points:

Finally, the algorithm classifies remaining points as noise if they are not density-reachable from any core point. The resulting DCS produces clusters and a noise set containing outliers.

3.5.3. DBSCAN Constrained Markowitz Problem

For K clusters identified via DCS, the optimization problem incorporates cluster-aware constraints. The formulation is:

In this constrained optimization problem, represents DBSCAN cluster-level risk budgets, and denotes the noise risk budget.

3.5.4. PSO with Stretching for DBSCAN Cluster-Aware Optimization

For each particle p representing portfolio weights , the particle swarm optimization dynamics are governed by velocity and position updates. The velocity update equation is:

The projection operator enforces DBSCAN cluster constraints, noise constraints, and budget constraints simultaneously.

3.5.5. DBSCAN Cluster-Guided Stretching

When local minima occur at iteration , the stretching function modifies the objective landscape. The stretched objective function is defined as:

In this formulation, is defined via DBSCAN cluster memberships and noise classification, are stretching parameters, and represents the indicator function that activates the stretching effect only within the specified region.

3.5.6. Pseudo-Code for DBSCAN Cluster-Guided PSO with Stretching

In Table A6 (see the Appendix A to save space), the pseudo-code merges density-based clustering for stock grouping with dynamic PSO parameters to locate the global optima, and assigns weights to securities for optimized portfolio construction.

4. Empirical Application

4.1. Data Preparation

This analysis examines a six-year period from January 2020 to December 2025, utilizing daily data. For each stock market under consideration, I collect for the purpose of the empirical analysis: (i) the Stock Index itself; (ii) the Constituents of the Index; (iii) 10-year government bond yields as the risk-free rate; and (iv) one Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) per stock market. The objective is to create optimized buy-and-hold Markowitz portfolios over the six-year period and evaluate the performance of PSO with stretching and clustering against market indices and ETF benchmarks.

To ensure numerical stability in high-dimensional settings, I implement a safe covariance shrinkage function. This mechanism checks the observation-to-asset ratio and applies James-Stein type shrinkage to the covariance matrix; in cases where data density is insufficient, the algorithm automatically falls back to a robust standard covariance estimator to prevent singular matrix errors during PSO fitness evaluation.

4.2. DJ Euro Stoxx 50

The Euro Stoxx 50 is a benchmark for the eurozone equity market, comprising the 50 largest companies across various industries.

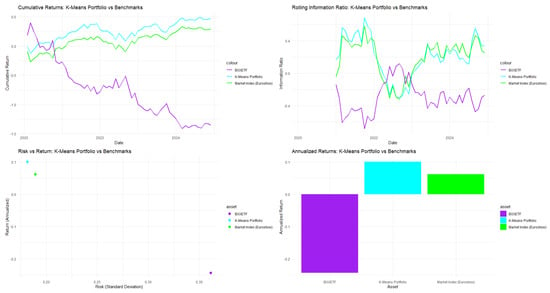

In Table 1, the portfolio optimization analysis of the Eurostoxx 50 reveals significant performance differences among algorithms. K-means clustering is the most effective, achieving a Sharpe ratio of 0.7913, exceeding the SWARM algorithm at 0.7865, while Hierarchical Clustering and DBSCAN lag behind. K-means provides the highest portfolio return mean of 0.1008, despite having a moderate risk standard deviation of 0.1814. In terms of downside risk, K-means has a Calmar ratio of 0.3057, outperforming other methods and demonstrating strong tail risk protection along with substantial returns. It reports a maximum drawdown of 0.2721, balancing risk and return effectively. Additional metrics further support K-means, with a Value-at-Risk of −0.2810, Expected Shortfall of −0.3544, and the best Omega ratio at 1.4763. Overall, K-means clustering is the top choice for portfolio optimization in the Eurostoxx 50, excelling in both returns and risk management.

Table 1.

Portfolio Analytics for DJ Euro Stoxx 50.

In Table A7 (see Appendix A to save space), the portfolio created using cluster-guided PSO with K-Means features a two-tier weighting structure. The top 15 holdings are split into two clusters: Cluster 5 and Cluster 7, each with different risk allocations. Cluster 5, the highest-tier, contains six assets—Adyen, Hermès, Ferrari, Schneider Electric, ASML Holding, and Dassault Systèmes—each weighted equally at 6.73%, totaling 40.39% of the portfolio. This uniform weighting optimizes the assets for better risk–return potential. Cluster 7 includes nine assets, with individual allocations of 4.49%, contributing to 40.38% of the portfolio. Notable companies here are Enel, Iberdrola, and SAP, providing sector diversification, albeit with potentially lower risk-adjusted returns than Cluster 5. From a diversification standpoint, the portfolio spans various sectors, but it carries concentration risks due to uniform weights within the clusters, which may lead to correlated performance in market downturns. The constraints of the algorithm prioritize uniform weights, illustrating a trade-off between structured risk management and traditional mean-variance optimization, thereby impacting the diversification efficiency.

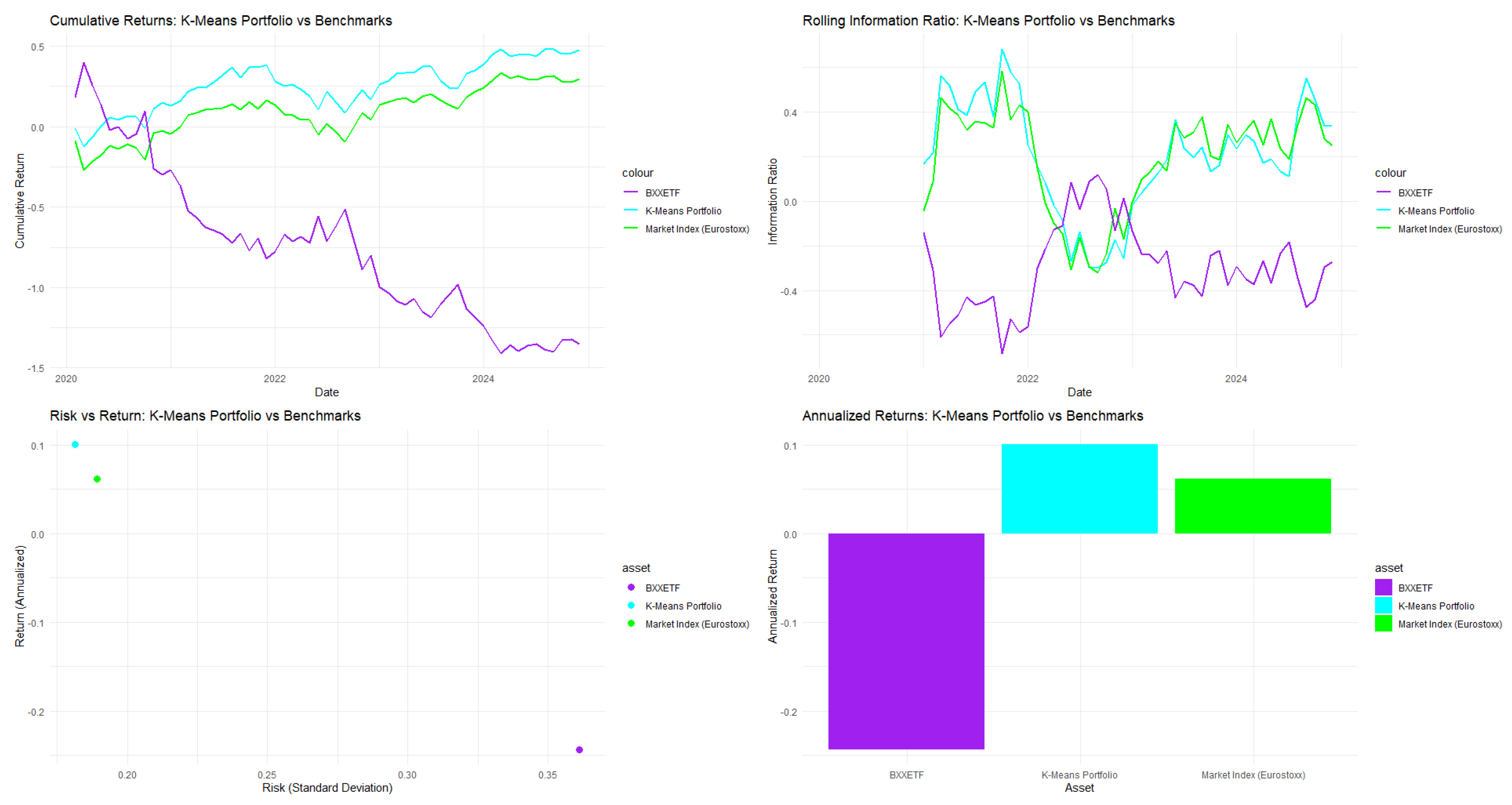

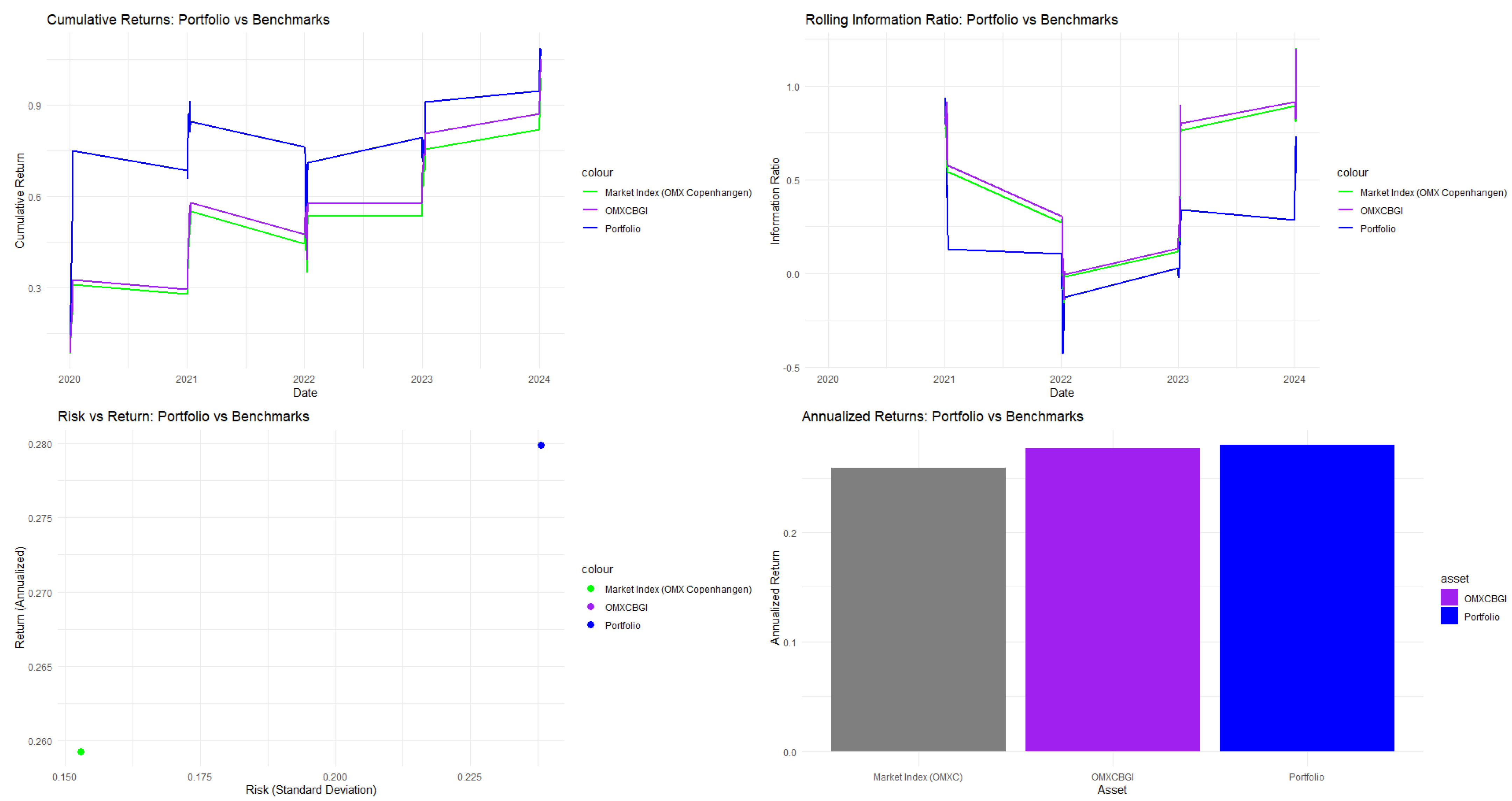

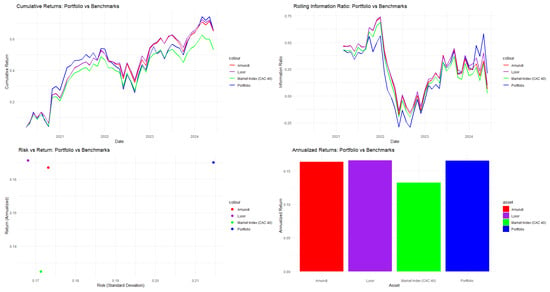

As illustrated in Figure 1, the K-Means guided PSO with stretching slightly outperforms the performance of both the DJ Eurostoxx 50 market index itself, as well as the Amundi EUR STOXX 50 Dly (-2x) Inv UCITS ETF Acc (BXX).

Figure 1.

Performance analytics for DJ Euro Stoxx 50.

4.3. S&P CNX Nifty 50

Exchanged on India’s National Stock Exchange (NSE), the Nifty 50 is an important index made up of 50 selected stocks from major economic sectors.

In Table 2, both the SWARM algorithm (without clustering) and the Hierarchical Clustering algorithm perform well in terms of portfolio optimization techniques for the Nifty 50 index. Both methods yield similar Sharpe ratios, with SWARM at 1.06571 and Hierarchical Clustering at 1.06653. However, SWARM indicates a higher mean portfolio return of 0.22292, surpassing Hierarchical Clustering’s 0.19703; though it incurs more risk, evident in the standard deviations of 0.20661 for SWARM versus 0.18218 for Hierarchical Clustering. In terms of downside risk management, Hierarchical Clustering excels with a Calmar ratio of 0.74068 compared to 0.64965 for SWARM, alongside a maximum drawdown of 0.24009 versus 0.29790. Value-at-Risk statistics further favor Hierarchical Clustering, showing at −0.25785 compared to SWARM’s −0.34271, and better Expected Shortfall at −0.42925 against SWARM’s −0.59912. Additionally, Hierarchical Clustering’s Sortino ratio of 1.29239 outperforms SWARM’s 1.14218, indicating superior risk-adjusted returns. It also demonstrates lower negative skewness (−0.41923 versus −1.57752) and decreased kurtosis (2.16304 versus 4.34262), suggesting a more stable return distribution. In comparison, both K-means (0.76777) and DBSCAN (1.18035) present competitive Sharpe ratios but struggle with downside risk management, evidenced by lower Calmar ratios of 0.38237 and −0.02367. K-means has the highest maximum drawdown at 0.37850 and concerning negative skewness at −2.21309. In conclusion, Hierarchical Clustering is recommended for optimizing Nifty 50 portfolios due to its superior Calmar ratio and effective downside risk management, essential for practical investment strategies.

Table 2.

Portfolio Analytics for Nifty 50.

In Table A8 (see Appendix A to save space), the Nifty 50 portfolio, organized through Hierarchical Clustering, emphasizes the top eight holdings, each at 7.17%, leading to a total of 57.38% from Cluster 4. Sector composition shows a mix of benefits and risks. The pharmaceutical sector, led by Cipla Ltd. and Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd., accounts for 14.35%, enhancing diversity but facing regulatory challenges. The technology sector, featuring HCL Technologies Ltd. and Wipro Ltd., also at 14.35%, is exposed to global tech spending shifts and currency risks. In the industrial and materials sectors, Hindalco Industries Ltd. and Bharat Petroleum Corporation Ltd. contribute 14.35%, linking them to commodity prices. Tata Motors Ltd. in automotive and Britannia Industries Ltd. in consumer goods dilute risk, each at 7.17%. The portfolio has a balanced sector distribution but suffers from equal weighting, which contradicts the Markowitz principle of tailored allocations based on expected returns and risks. The focus on Cluster 4 increases risk during market stress, and while sector diversity helps, uniform weighting can limit risk-adjusted returns.

As pictured in Figure 2, both the Hierarchical Clustering-guided PSO with stretching algorithm and the Nippon Nifty 50 BeES (NBES) ETF beat the market index; the clustering algorithm even surpasses the performance of the ETF itself.

Figure 2.

Performance analytics for Nifty 50.

4.4. FTSE China A50

The China A50 Index tracks 50 major A-shares from the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges, developed by FTSE Russell. It serves as a benchmark for equity investments in mainland China and reflects increasing global interest in Chinese equities.

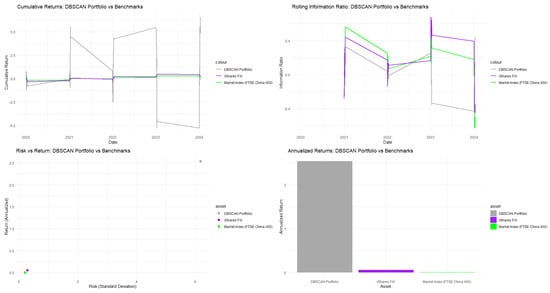

In Table 3, DBSCAN clustering demonstrates strong performance for the China A50 index, making it advantageous for portfolio optimization. It achieved a Sharpe ratio of 0.4077, similar to K-means’ 0.4100, while significantly outperforming SWARM (0.0631) and Hierarchical Clustering (0.2789). DBSCAN also had the highest Calmar ratio at 0.5790, exceeding K-means (0.5202), SWARM (0.1417), and Hierarchical Clustering (0.2095), indicating better risk-adjusted returns relative to maximum drawdown. The mean return for DBSCAN reached 2.5397, far surpassing K-means (0.1556) and SWARM (0.0372), highlighting its ability to identify high-return opportunities in the Chinese market. Additionally, it recorded the highest Treynor ratio (0.0859) and a favorable Sortino ratio (0.2526), in stark contrast to the negative ratios from competing methods, indicating better downside risk management. DBSCAN also produced the highest Jensen’s alpha (0.1692), showing significant value beyond market expectations. While its volatility metrics are higher, this reflects a proactive return-seeking strategy that captures the dynamic nature of Chinese A-shares. The density-based approach of DBSCAN’s superior Calmar ratio and competitive Sharpe ratio make it a preferred choice for investors aiming to maximize risk-adjusted returns in the Chinese equity market.

Table 3.

Portfolio Analytics for China A50.

In Table A9 (see the Appendix A to save space), the analysis of DBSCAN-Guided PSO with the Stretching Algorithm for China A50 stocks reveals a significant deviation from the Markowitz portfolio approach, indicating strong sector concentration. The top nine holdings are primarily in the consumer discretionary sector, especially the alcoholic beverage sub-sector, comprising about 39.7% of the portfolio. Key stocks include Kweichow Moutai and Wuliangye Yibin, signifying strong co-movement in the baijiu industry. There is minimal representation from healthcare and technology, raising concerns about diversification. The algorithm allocates nearly 9.92% to the top holdings, focusing on risk-adjusted returns instead of traditional diversification, suggesting a similar risk–return profile among these assets. This concentration in consumer staples and discretionary sectors contrasts with the Markowitz principle of including uncorrelated assets to mitigate risk. The findings imply that correlation-based strategies may be less effective in the Chinese market due to its unique sector dynamics.

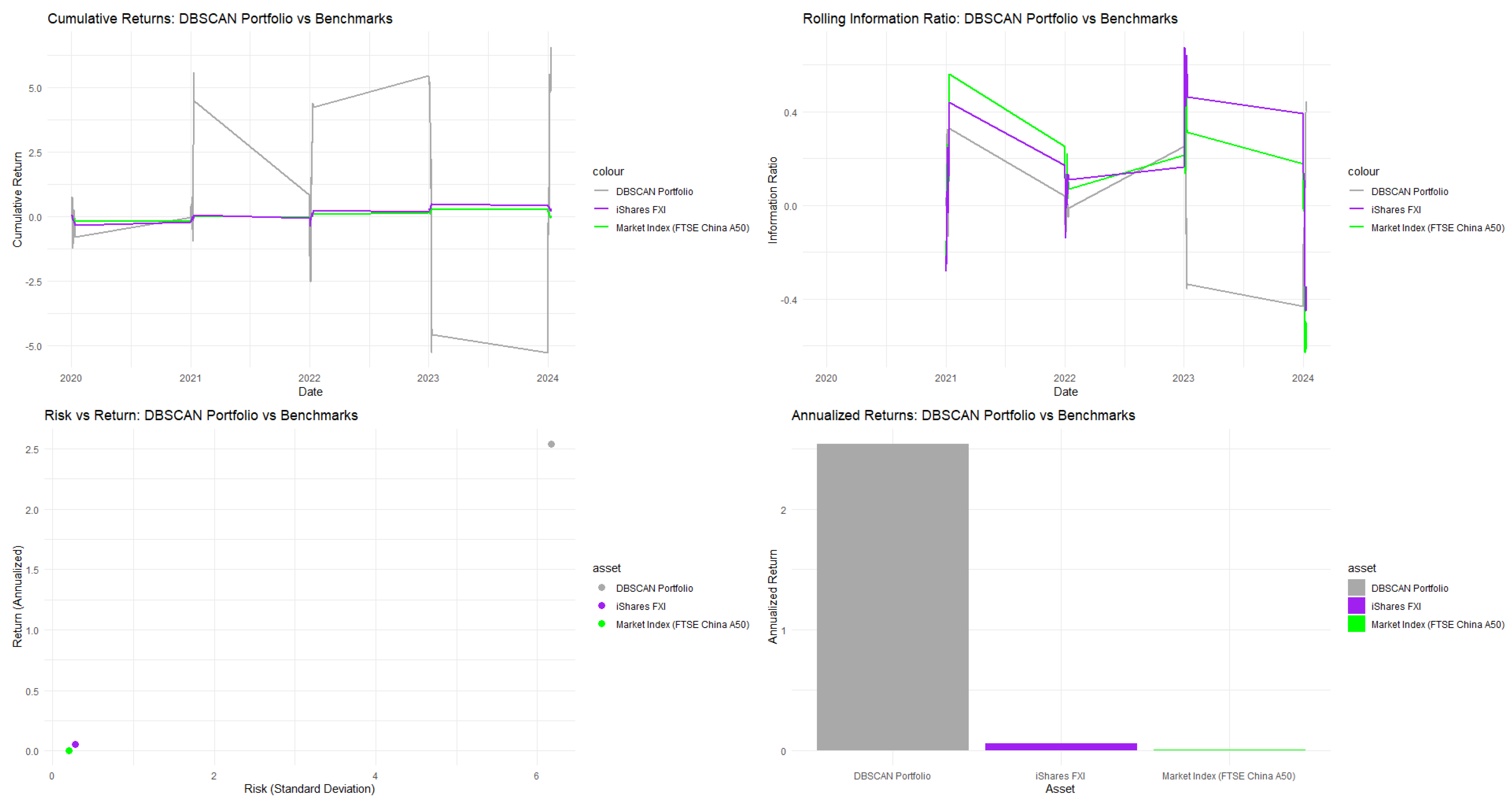

As shown in Figure 3, the DBSCAN method effectively identifies high-quality Chinese equities and may exploit market inefficiencies better than traditional optimization methods. It surpasses both the China A50 market index and the iShares China Large-Cap FXI ETF.

Figure 3.

Performance analytics for China A50.

4.5. Euronext CAC 40

The CAC 40 is the primary index for the Paris Bourse, featuring the performance of the 40 major companies in the French equity market.

In Table 4, regarding the French CAC 40 stock market, the SWARM Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with the Stretching algorithm significantly outperforms clustering-guided PSO methods across key risk-adjusted performance metrics. Notably, the SWARM algorithm (without clustering) records a Sharpe ratio of 0.4690. The Calmar ratio of 0.5406 indicates strong performance against maximum drawdown. The unconstrained SWARM PSO with Stretching proves more effective for portfolio optimization, balancing risk with a beta of 1.2077 and a maximum drawdown of 0.2594. Its favorable Sharpe and Calmar ratios demonstrate a solid return-risk balance, and return distributions show positive skewness. The success of the SWARM PSO with Stretching supports the use of advanced algorithms that do not necessarily rely on predefined asset groupings. In conclusion, although clustering strategies may appear advantageous, they can impose constraints that hinder portfolio efficiency in the French CAC 40 stock market.

Table 4.

Portfolio Analytics for CAC 40.

In Table A10 (see the Appendix A to save space), the SWARM PSO portfolio, without clustering, reflects Markowitz diversification theory, focusing on sector distribution and risk management. The algorithm allocates 5.0403% to the top 19 holdings, indicating a balanced approach with similar risk-adjusted returns, differing from market capitalization-weighted strategies. The portfolio displays solid sector diversification in the French economy, featuring TotalEnergies (energy), Vinci (industrials), and automotive firms like Stellantis and Renault. A significant 20.16% is allocated to financials, including BNP Paribas and AXA, highlighting sector importance but raising concentration risk concerns. Major firms like Schneider Electric and Airbus provide exposure to both domestic and international markets, aligning with France’s industrial focus. The portfolio includes Sanofi (pharmaceuticals), EssilorLuxottica (consumer discretionary), and Saint-Gobain (construction). While sector distribution appears reasonable, the asset allocation from the SWARM PSO algorithm somewhat lacks exposure to traditional consumer staples and technology, possibly reflecting preferences for value sectors within the CAC 40.

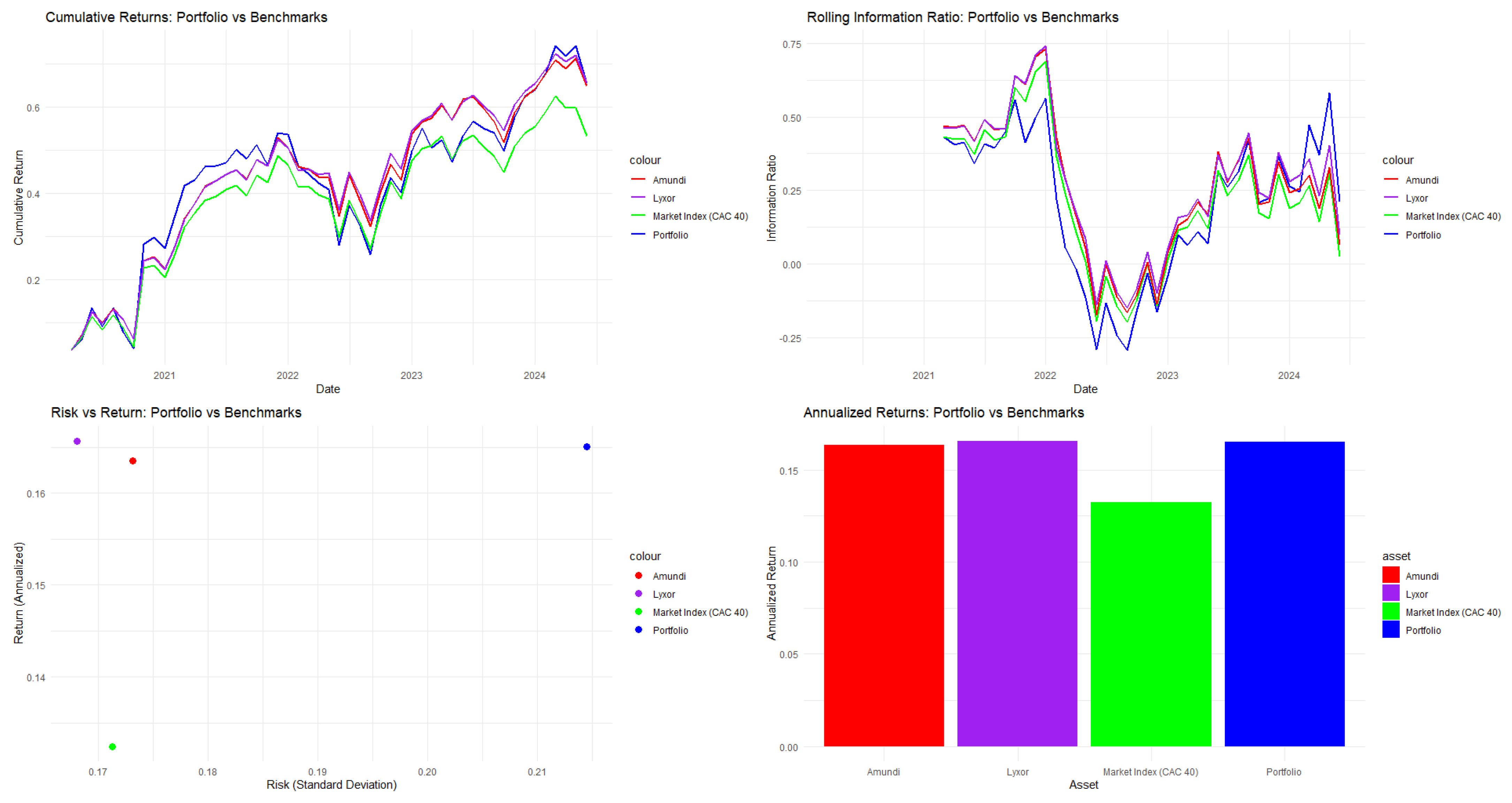

As displayed in Figure 4, the SWARM (without clustering) with the Stretching algorithm outperforms the CAC 40 index, and matches the performance of the Amundi CAC 40 UCITS and Lyxor UCITS Daily ETFs.

Figure 4.

Performance analytics for CAC40.

4.6. Euronext BEL 20

The BEL 20 Index is the main benchmark for the Brussels Stock Exchange, representing the 20 largest and most liquid companies listed on the Belgian stock exchange, making it a key indicator of the Belgian equity market.

In Table 5, for the Belgian BEL 20 stock market, the K-Means-guided Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with the Stretching algorithm outperforms other optimization methods. It achieves a Sharpe ratio of 1.0004, exceeding the SWARM method at 0.9577 and hierarchical clustering at 0.8264. K-Means effectively balances returns with risk, with a portfolio volatility higher than SWARM’s 0.1310 and hierarchical clustering’s 0.1393. It offers a Calmar ratio of 0.5783, demonstrating superior performance. Despite a maximum drawdown of 0.2178, it remains manageable due to its favorable risk–return profile. The K-Means methodology has a beta of 0.8459, indicating moderate sensitivity to market movements, which allows it to capitalize on market uptrends while maintaining some defensive qualities. The K-Means algorithm shows acceptable tail risk, with a 5% Value-at-Risk of −0.2421 and an Expected Shortfall of −0.3140, justifying its higher tail risk through significant returns.

Table 5.

Portfolio Analytics for BEL 20.

In Table A11 (see the Appendix A to save space), regarding the BEL 20 Cluster-Based Allocation, the portfolio exhibits a high concentration risk, with 26.83% invested in arGEN-X SE, a biopharmaceutical company, which undermines diversification. Other significant asset allocations are visible at 4.48% each in Cluster 1: the portfolio is diversified across industries, including sustainability (Umicore), financial services (KBC Group, Ageas), and consumer goods (Anheuser-Busch InBev). Melexis NV adds semiconductor exposure. Other holdings include Proximus (telecommunications), Solvay (chemicals), and Aperam (specialty materials), enhancing industrial diversification. While sectors are somewhat diversified, the significant investment in arGEN-X SE does introduce considerable idiosyncratic risk. To minimize exposure to high-risk assets, the K-Means PSO utilizing the Stretching method should decrease the allocation to arGEN-X and instead reallocate based on asset characteristics that could enhance performance while mitigating risks.

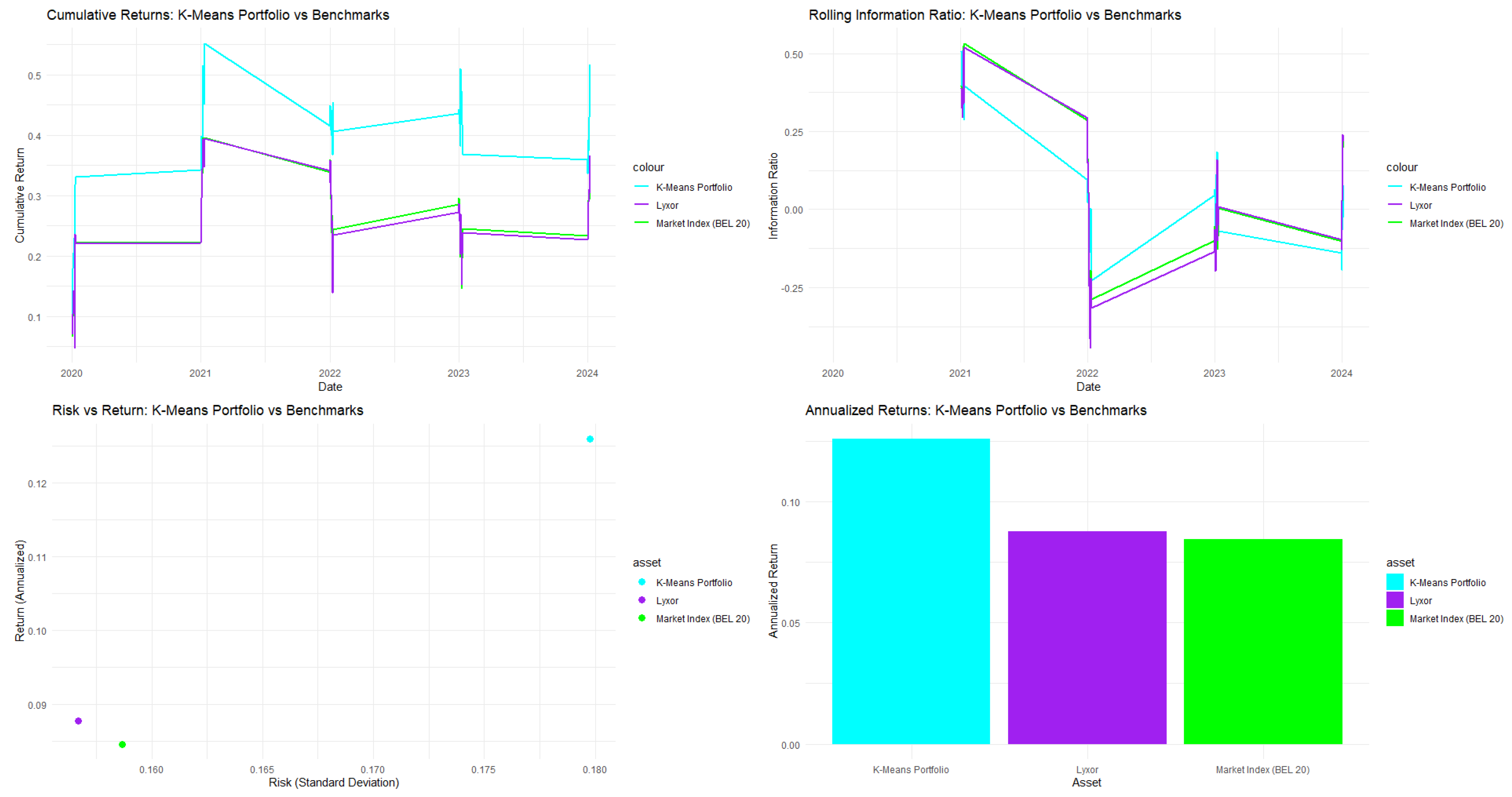

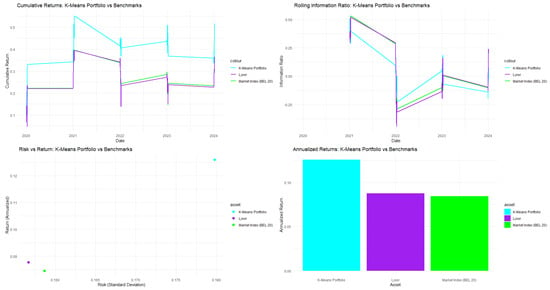

As shown in Figure 5, the K-Means-guided PSO with Stretching improves mean-variance optimization, enabling better risk–return trade-offs compared to SWARM and other methods in the Belgian market.

Figure 5.

Performance analytics for BEL 20.

4.7. Nasdaq OMX Copenhagen 20

The OMX Copenhagen 20 Index is the leading benchmark for the Copenhagen Stock Exchange, comprising the 20 most actively traded stocks, which tracks the performance in the Danish equity market.

In Table 6, the SWARM (without clustering) PSO with the Stretching algorithm shows superior performance in risk-adjusted return metrics for the Nasdaq OMX Copenhagen 20. It achieves a Sharpe ratio of 0.9581, outperforming clustering-based methods and demonstrating superior risk–return efficiency. With a Calmar ratio of 0.8096, SWARM balances returns and downside risk effectively, aligning with Markowitz’s goal of maximizing return per unit of risk. The methodology yields a mean return of 0.2799 and a standard deviation of 0.2381, placing it on the efficient frontier and showcasing optimal mean-variance trade-offs. The low drawdown of 0.3457 highlights strong risk management. Additionally, the Omega ratio of 2.2149 indicates more than double the potential upside compared to downside risk. The portfolio’s beta of 1.0602 suggests slightly above-market systemic risk, while the return distribution’s skewness of −0.0608 and kurtosis of −0.0364 is close to normal, supporting mean-variance optimization. In conclusion, the hybrid SWARM-PSO-Stretching methodology effectively tackles Markowitz portfolio optimization challenges and represents a significant advancement in modern investment strategy for the Danish stock market.

Table 6.

Portfolio Analytics for OMX C20.

In Table A12 (see the Appendix A to save space), the SWARM particle swarm optimization enhanced with a stretching algorithm achieves a uniform allocation of 17.86% across the top five constituents of the Nasdaq OMX Copenhagen 20 portfolio, contrasting with traditional Markowitz optimization, which often results in uneven allocations. The portfolio is well-diversified within the Danish economy. NKT A/S offers low-, medium-, and high-voltage power solutions, aligning with Europe’s renewable energy transition, while Vestas Wind Systems focuses on wind turbine design. Jyske Bank, Denmark’s third-largest bank, adds financial stability with regional diversification, and Pandora A/S, a prominent jewelry manufacturer, enhances geographic reach. The ROCKWOOL Group contributes through stone wool solutions, benefiting from strong construction activity. The uniform weight distribution suggests the SWARM algorithm optimizes beyond mean-variance efficiency, resulting in a balanced allocation across infrastructure, renewable energy, financial services, consumer goods, and industrial materials, ensuring strong regional coherence in the Nordic market.

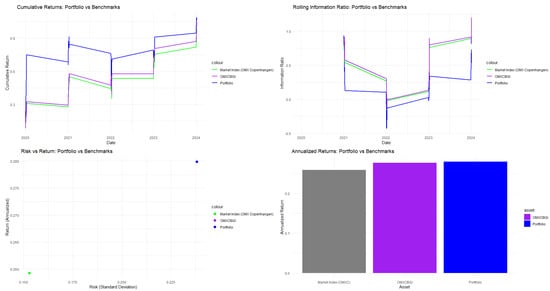

As reported in Figure 6, the SWARM algorithm beats the OMX Copenhagen market index itself, as well as the OMX Copenhagen Benchmark (OMXCBGI) ETF by a small margin.

Figure 6.

Performance analytics for OMX C20.

4.8. Sensitivity Analyses

In this section, I verify the robustness of our empirical estimates with respect to three sources of variations (for brevity, applied only to the Belgium and Danish stock markets with the SWARM algorithm).

4.8.1. Rebalancing

The backtesting framework employs an expanding window approach. While the initial portfolio is held for 24 months, I implement dynamic monthly rebalancing from month 25 through month 60. During each rebalancing event, the Swarm solver recalculates optimal weights based on all preceding data. To align the model with real-world trading conditions, implicit transaction costs of 3 basis points are applied to all weight rotations1, ensuring that the reported performance accounts for turnover friction.

For BEL20, the SWARM solver runs for 14.77 s in the buy-and-hold scenario, versus 44.52 s with monthly rebalancing of portfolio weights. For OMXC20, the SWARM solver runs for 15.25 s in the buy-and-hold scenario, versus 44.02 s with monthly rebalancing of portfolio weights.

In Table 7, I present the performance comparison between buy-and-hold, initial holding, and monthly rebalancing strategies for both indices. For BEL 20, the initial holding period (months 1–24) delivers the highest mean return (1.35%) and Sharpe ratio (1.1242). The rebalancing period (months 25–60) shows negative returns (−0.06%) with decreased risk-adjusted performance (0.7584). This suggests that the portfolio benefits from stability in the first two years but faces deterioration during the rebalancing phase. For OMXC20, all strategies yield negative Sharpe ratios, indicating poor risk-adjusted performance. The holding period produces the highest returns (2.72%) but remains inadequate for positive risk compensation. The rebalancing period exhibits further degradation with returns near zero (−0.16%) and the lowest Sharpe ratio (−0.6522). The negative Sharpe ratios across OMXC20 periods suggest systematic underperformance relative to the risk-free rate.

Table 7.

Rebalancing results.

4.8.2. Out-of-Sample Forecasting

I trained the model over 5 years (January 2020–December 2024), and consider the last year 2025 as the testing window. This procedure is documented within the pseudo-code (Table A3).

To evaluate the predictive significance of the SWARM framework, I move beyond point estimates by reporting Theil’s U statistic, defined as , where implies superior predictive power over a naive forecast. This metric assesses the model against a naive random-walk forecast; a value of indicates that the algorithm successfully captures structural market signals rather than coincidental patterns. Furthermore, I utilize Equity Curve Partitioning to visually distinguish between in-sample optimization and out-of-sample validation periods.

For BEL20, the out-of-sample forecast takes 13.41 s to run. For OMXC20, the out-of-sample forecast takes 13.92 s to run.

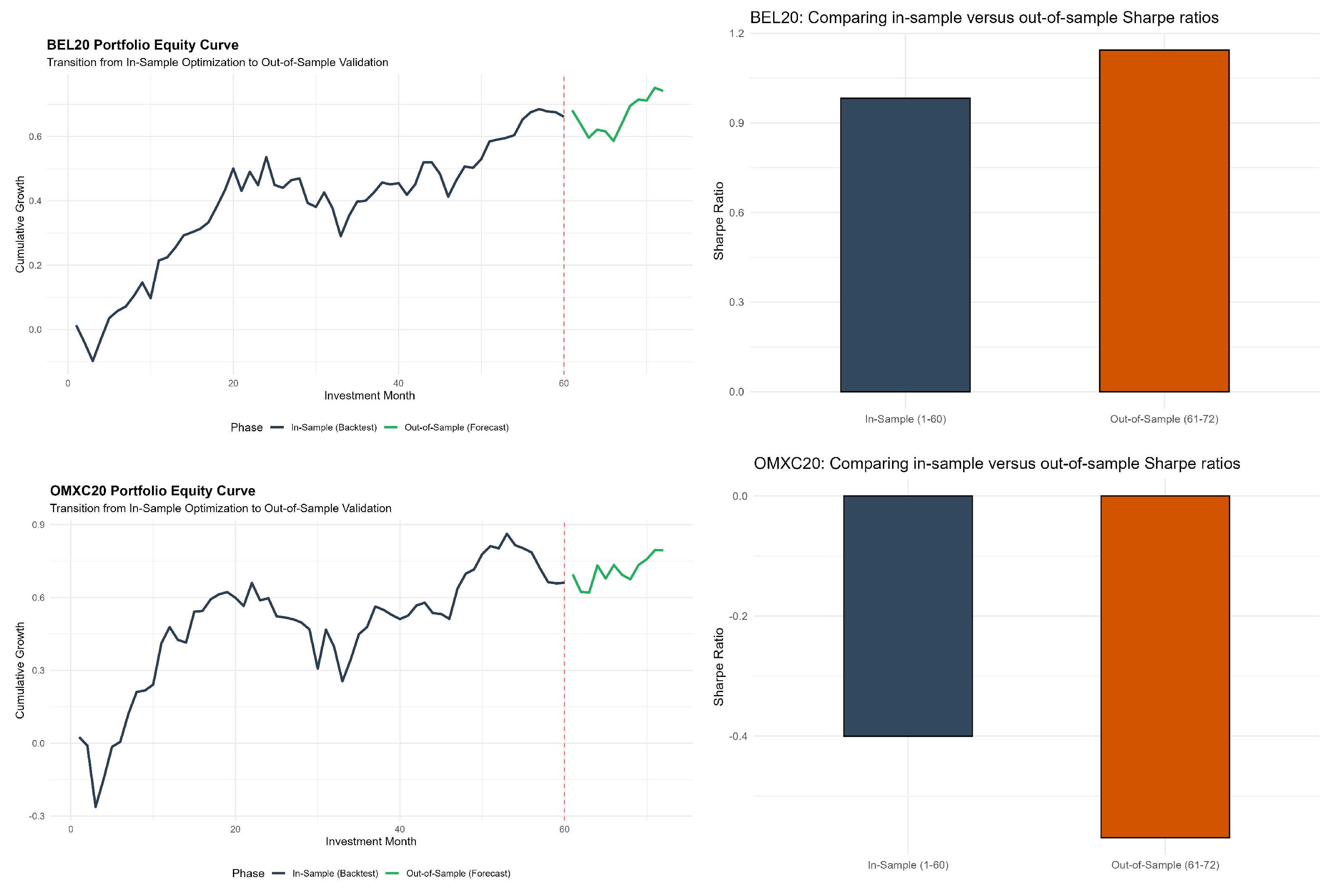

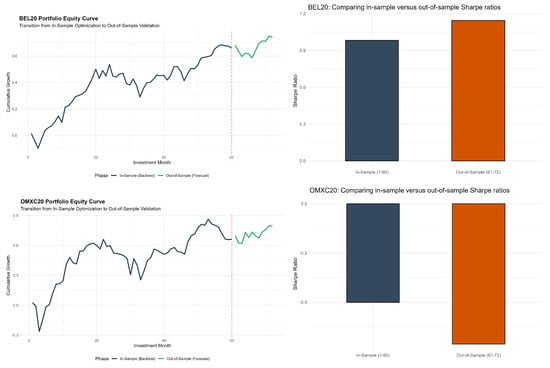

In Table 8, I examine the generalization capability of the optimized portfolios through in-sample and out-of-sample comparison. For BEL 20, the out-of-sample period exhibits lower mean returns (0.67% vs. 1.10%) and reduced volatility (0.0344 vs. 0.0444). The Sharpe ratio improves slightly in the forecast period (1.1439 vs. 0.9824), indicating better risk-adjusted performance despite lower absolute returns. The cumulative return drops substantially from 66.13% in-sample to 8.04% out-of-sample over the shorter twelve-month horizon. For OMXC20, mean returns remain stable between periods (1.10% vs. 1.12%). Volatility decreases markedly out-of-sample (0.0530 vs. 0.0757), yet the Sharpe ratio deteriorates further (−0.5693 vs. −0.4004). This persistent negative risk-adjustment suggests the portfolio consistently underperforms the risk-free rate. The cumulative return reduction from 66.06% to 13.38% reflects both the shorter evaluation window and continued weak performance.

Table 8.

Out-of-sample forecasting results.

In Table 9, I report detailed forecast accuracy and portfolio risk metrics for the out-of-sample period. For BEL 20, the MAE (2.88%) and RMSE (3.32%) indicate moderate prediction errors. The MAPE of 150% suggests high relative forecast errors, likely driven by periods where actual returns approach zero. Theil’s U statistic (0.7444) below unity indicates the model outperforms naive forecasts. The Sortino ratio (1.9935) demonstrates strong downside risk-adjusted performance. Maximum drawdown remains contained at 9.51%. The win rate of 50% shows balanced positive and negative return months. For OMXC20, forecast errors are higher with MAE at 4.26% and RMSE at 5.07%. The MAPE (251.67%) and Theil’s U (0.8059) confirm weaker predictive accuracy, though still superior to naive benchmarks. The negative Sortino ratio (−1.0380) reflects poor downside risk management. Maximum drawdown (7.46%) is lower than BEL 20 but occurs within an overall negative performance context. The 50% win rate indicates no directional edge in the forecast period.

Table 9.

Out-of-sample forecasting metrics.

In Figure 7, I visualize the out-of-sample forecasting performance through equity curves and Sharpe ratio comparisons for both indices. The top-left panel shows the BEL20 equity curve, which exhibits steady growth during the in-sample period (months 1–60), accumulating approximately 66% cumulative return. At month 60, marked by the red dashed line, the transition to out-of-sample validation occurs. The green segment demonstrates continued positive performance in the forecast period, adding an additional 8% despite increased volatility. The top-right panel confirms Sharpe ratio improvement from 0.98 in-sample to 1.14 out-of-sample, indicating enhanced risk-adjusted returns during validation. This improvement occurs despite lower absolute returns, reflecting the volatility reduction observed in Table 8.

Figure 7.

Out-of-sample forecasting plots for BEL20 (top) and OMXC20 (bottom). Note: The red dashed line represents the start of the out-of-sample forecasts.

The bottom-left panel presents the OMXC20 equity curve, revealing higher volatility throughout the in-sample period. The portfolio experiences significant drawdowns, notably around months 5, 32, and the terminal phase before month 60. Despite volatility, cumulative returns reach 66% by the end of in-sample optimization. The out-of-sample segment shows an initial decline followed by a recovery, accumulating 13.4% over twelve months. The bottom-right panel displays negative Sharpe ratios in both periods (−0.40 in-sample, −0.57 out-of-sample). The deterioration indicates that reduced volatility in the forecast period does not compensate for persistent underperformance relative to the risk-free rate. The equity curve’s continued upward trajectory despite negative Sharpe ratios suggests that absolute returns remain positive but fail to provide adequate risk compensation.

4.9. Turnover

Institutional rebalancing between January 2020 and December 2025 reflected varying levels of turnover for both indices. The BEL20 recorded the highest turnover at 20%, rotating four constituents: Proximus (PROX), Galapagos (GLPG), Aperam (APAM), and Ahold Delhaize (AHOG) were replaced by Lotus Bakeries (LOTB), Montea (MONTE), Agfa-Gevaert (AGFB), and Bekaert (BEKB). In contrast, the OMXC20 exhibited high continuity (5% turnover), substituting only GN Store Nord (GN) with FLSmidth & Co. (FLS). These migrations underscore a pivot toward industrial logistics and defensive consumer segments, which the SWARM algorithm must navigate to maintain portfolio efficiency. In particular, the shift to Belgium’s stock Lotus Bakeries (LOTB) aligns with the algorithm’s preference for lower-beta defensive stocks during the volatility observed in the 2022–2023 period.

5. Conclusions

I develop an algorithmic framework that combines Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), function stretching, and clustering to enhance portfolio optimization and asset allocation. Function stretching modifies the objective function to reduce local minima while preserving the global optimum, thereby preventing premature convergence and improving search robustness. Clustering is also incorporated to organize similar data points, enhancing both the interpretability of the solution space and the analytical capabilities of the framework. This integration yields a methodology that enhances PSO’s global search capabilities, demonstrating competitive performance in complex, high-dimensional, and multi-modal optimisation, as well as in unsupervised data analysis tasks.

In terms of empirical validation, the analysis of six stock markets reveals that the effectiveness of algorithmic strategies in portfolio optimization varies by market characteristics, requiring tailored approaches. The empirical results demonstrate the generalization capability of this algorithmic family across diverse market environments, with K-means clustering variants performing competitively in the Eurostoxx 50 and Belgian BEL 20 indices, while the baseline SWARM algorithm shows comparable efficacy in the French CAC 40 and Danish OMX Copenhagen markets. demonstrating that clustering-enhanced PSO algorithms can be systematically adapted to The key methodological contribution lies in market-specific characteristics, thereby providing portfolio managers with a comprehensive toolkit for asset allocation across different market structures. These results emphasize that the proposed algorithmic framework offers significant practical value by enabling market-specific optimization strategies, highlighting the importance of adaptive algorithms that can respond to evolving market dynamics while maintaining computational efficiency.