Abstract

This study examines the extent to which Indian technology equities generate sufficient returns relative to their inherent volatility and assesses whether intra-sector diversification can improve outcomes in this dynamic, high-risk sector. Drawing on data from January 2020 to April 2025, ten leading firms are analyzed using an integrated approach that incorporates traditional risk-adjusted indicators, downside-sensitive metrics, and a six-factor model featuring momentum. The results show clear heterogeneity in performance. Mid-cap innovators such as Persistent Systems and Coforge deliver positive and, in some cases, statistically significant alphas, while large-cap stocks including Infosys, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), and Wipro provide stability but limited excess returns. At the portfolio level, an equally weighted allocation improves downside protection. However, factor-model analysis finds no statistically significant portfolio alpha once systematic exposures are accounted for. These findings highlight the importance of active firm-level selection within the Indian technology sector, while also underscoring the role of intra-sector diversification in mitigating extreme losses.

1. Introduction

India’s technology sector has been a major contributor to the country’s economic expansion, spurred by rapid digitalization, rising global outsourcing, and continuous innovation. The digital economy is poised to make up almost one-fifth of India’s GDP by FY2029–30. For long-term investors, this growth trajectory indicates the sector’s significance. Yet rapid growth has been accompanied by pronounced volatility, raising a fundamental question for portfolio construction: do Indian technology equities deliver returns that adequately compensate investors for the risks they bear? This question is particularly relevant since sector-level exposure often conceals significant heterogeneity across companies. This leaves investors wondering whether diversification within the technology sector truly enhances risk-adjusted performance or redistributes volatility among correlated assets.

Significant research has analyzed the performance of Indian mutual funds and broad equity benchmarks, while comparatively less attention has been given to performance at the firm level in specific industries, such as technology (Malhotra et al., 2024; Malhotra & Singh, 2025). Existing literature predominantly employs traditional risk-adjusted performance measures such as the Sharpe and Sortino ratios (Sharpe, 1966; Sortino & van der Meer, 1991), which focus on mean–variance trade-offs and rest on the assumptions of normally distributed returns. These assumptions are particularly restrictive for technology stocks, which are known to exhibit return distributions with significant asymmetry, fat tails, and sharp drawdowns during times of macroeconomic distress. Despite the availability of more comprehensive performance measures, including the Omega ratio (Keating & Shadwick, 2002), the adjusted Sharpe ratio (Pezier & White, 2006; Zakamouline & Koekebakker, 2009), and drawdown-based measures such as the Calmar ratio (Young, 1991; Eling & Schuhmacher, 2007), their empirical application to Indian technology equities remains limited. Consequently, the existing literature offers an incomplete assessment of firm-level risk–return characteristics and the role of intra-sector diversification within this high-growth segment.

This paper fills the above gaps by examining the risk-adjusted performance of ten leading Indian technology stocks from January 2020 to April 2025. We use a combination of traditional risk-adjusted measures, downside-risk measures, tail-risk metrics, and a six-factor asset pricing model that incorporates momentum factors to provide a holistic view of performance that goes beyond conventional benchmarks. More importantly, we also investigate the impact of intra-sector diversification at the portfolio level to distinguish between stock-specific alpha generation and returns that are compensation for systematic risk factors. The paper provides new insights into the sources of performance differences across Indian technology equities and the extent to which diversification within the sector can reduce downside risk without creating persistent abnormal returns.

The January 2020 to April 2025 period was marked by considerable disruption within the financial sphere, largely attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing post-pandemic realignments. Throughout this timeframe, technology firms exhibited sudden, occasionally fleeting, increases in revenue and profitability, coupled with modifications in operational costs, profit margins, and investment strategies. The frequent adjustments to corporate projections and evolving market expectations fostered increased volatility, non-normal return distributions, and shifting risk evaluations.

The technology sector is particularly well suited for analysis in this context. It was both a primary beneficiary of accelerated digitalization during the pandemic and one of the most affected sectors during the subsequent normalization of growth expectations and discount rates. Importantly, mid-cap and large-cap technology firms responded heterogeneously to these macroeconomic and financial shocks, making firm-level analysis especially informative. Moreover, the study period spans an extraordinary monetary policy environment characterized by near-zero interest rates, abundant liquidity, and later aggressive tightening to contain inflation. Given the sensitivity of technology equities to discount rates and growth expectations, this environment reinforces the relevance of examining risk-adjusted performance, factor exposures, and the disappearance of alpha at the portfolio level.

This study employs both traditional and downside-sensitive performance metrics in conjunction with a six-factor (including momentum) asset pricing model and tail-risk measures (Value-at-Risk and Conditional Value-at-Risk). The constructed sample allows a contrast between the anchor of large-cap stocks (Infosys, Tata Consultancy Services, Wipro) and the more growth (and in some cases alpha) chasing tendency of mid-caps (Persistent Systems, Coforge, Mphasis). The dual lens of firm and portfolio and the context of the broader literature on emerging market equities provides a comprehensive overview of how risk and opportunity in the form of participation in the growth of Indian technology stocks can be better navigated by investors and policymakers alike.

The rest of the paper is organized along the following lines. Section 2 reviews previous studies that examine risk-adjusted returns. In Section 3, we discuss the characteristics of the data used in this study. Section 4 discusses the methodology used in this paper. In Section 5, we discuss empirical results, and Section 6 concludes our study.

2. Previous Studies

Most of the existing research on Indian equities has concentrated on mutual funds and broader indices, with limited attention to sectoral dynamics. Deb et al. (2007) and Malhotra et al. (2024) showed that while Indian fund managers often demonstrate strong stock selection skills, their market timing ability remains weak. Such findings provide valuable insights into active management but do not extend to the performance of specific industries. Previous studies have widely applied standard risk-adjusted measures that include the Sharpe ratio (Sharpe, 1966) and Sortino ratio (Sortino & van der Meer, 1991) to evaluate the performance of funds and indices. However, they assume normality of returns and fail to account for asymmetric return patterns and tail risks that are typical of volatile sectors such as technology.

While advanced measures have been developed, such as those capturing skewness, kurtosis, and drawdowns, they have rarely been applied to Indian technology companies. The Omega ratio (Keating & Shadwick, 2002) considers the entire return distribution, the modified Sharpe ratio (Zakamouline & Koekebakker, 2009) adjusts for skewness and kurtosis, and the Calmar ratio (Eling & Schuhmacher, 2007) places more weight on maximum drawdowns instead of variance. These measures are well suited for sectors prone to sudden shocks, such as technology, but their application in the Indian equity space has been limited. In the context of India, sectoral analyses have mostly centered around innovation and export orientation (Parthasarathi & Joseph, 2002), rather than quantifying risk-return trade-offs. Studies on idiosyncratic volatility (Aziz & Ansari, 2017) and global interconnectedness (Raddant & Kenett, 2020) have shed light on broader market risks, leaving room for exploration of systematic and firm-specific exposures within the technology sector. This represents an unexplored opportunity.

The existing literature reveals that most of the Indian equity research has been conducted at the fund or the index level and firm performance, especially that of technology companies, remains unexplored at the firm level. Second, even though some advanced performance measures such as Omega ratio (Keating & Shadwick, 2002), adjusted Sharpe ratio (Zakamouline & Koekebakker, 2009) and Calmar ratio (Eling & Schuhmacher, 2007) that provide a more holistic view of risk-adjusted returns have been developed, they have rarely been used to benchmark Indian technology companies.

This study bridges the gaps by conducting an evaluation of ten Indian technology companies from 2020 to 2025 under a multi-dimensional performance framework. We use traditional measures of the Sharpe and Sortino ratios, downside-sensitive measures of the Omega and Calmar ratios, and a six-factor model by including momentum (Fama & French, 1993, 2015). We also consider the tail-risk measures of Value at Risk (VaR) and Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR) to illustrate how the performance can be altered in tail conditions. We then show how intra-sector diversification across the Indian technology industry can potentially improve the risk-adjusted outcomes and contextualize our findings to offer unique insights to investors and portfolio managers.

3. Data

Data for the monthly returns on each individual stock for this study are sourced from Investing.com. We gathered monthly returns for ten major Indian technology companies and two benchmark indices (Nifty IT Index and Nifty 50 Index) from January 2020 to April 2025. The study period is selected to capture the post–COVID-19 regime shifts in equity markets. January 2020 marks the onset of both extreme market volatility and an accelerated digitization phase that fundamentally reshaped the global technology industry. Furthermore, we start from 2020 to ensure complete data coverage for the set of firms in our sample. Nifty IT Index is a sector-specific benchmark that tracks the performance of the Indian technology sector. Nifty 50 Index is a broad market benchmark that tracks the performance of the overall Indian equity market. The dual benchmarks are used to track whether these firms outperform both sector peers and the broader market, providing a more comprehensive view on risk-return trade-off.

This study uses monthly return data for several key reasons. First, analyzing returns monthly is typical in risk-adjusted performance assessments and multi-factor asset pricing models; it also matches the frequency of Fama–French factor returns. Second, relying on monthly data helps reduce microstructure effects and short-term volatility distortions that can impact downside risk estimates at higher frequencies. Stock prices and returns are obtained from Investing.com, with adjustments made for dividends and stock splits to ensure consistency in total return calculations. To avoid survivorship bias, only firms listed continuously from January 2020 to April 2025 are included in the sample. The three-month U.S. Treasury bill yield serves as the proxy for the risk-free rate, in alignment with the construction of the factor datasets used in the empirical analysis.

Table 1 summarizes data for ten Indian technology stocks from January 2020 to April 2025, including an equally weighted portfolio and various benchmark indices. It presents average monthly returns, standard deviations, and return-to-risk ratio.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics of Monthly Returns for Indian Technology Stocks, an Equally Weighted Technology Portfolio, and Benchmark Indices (January 2020–April 2025).

Persistent Systems achieved the highest average monthly return at 5.15% and demonstrated the strongest return-to-risk ratio at 0.40. Despite exhibiting the greatest volatility among the stocks considered, its superior returns adequately compensated for the elevated risk profile. Both Coforge and Mphasis reported average monthly returns exceeding 2%, coupled with favorable return-to-risk ratios.

Infosys, TCS, and Wipro had average monthly returns of less than 1.5% and return-to-risk ratios of less than 0.20. This data shows that large-cap stocks may have been more stable, but they also gave lower returns throughout this time.

The average return for an equally weighted portfolio of ten technology stocks was 2.21%, with a return-to-risk ratio of 0.28. This portfolio outperformed most individual equities and all benchmark indices in return-to-risk, indicating that diversification benefits the Indian technology sector by balancing fast-growing and established companies.

The Nifty IT Index achieved a monthly return of 1.53%, while the broader Nifty 50 benchmark posted a 1.24% return. Although both indices have reasonable risk-adjusted ratios, 0.22 for Nifty IT and 0.23 for Nifty 50, these figures are lower than the return-to-risk ratio offered by a technology portfolio with equal weighting across ten companies.

The results in Table 1 show that an investor would have been better off with a diversified portfolio of Indian technology stocks than investing with either a sector-specific benchmark or broader equity markets in India. Persistent Systems and Coforge led in performance, but the diversified portfolio offered the optimal risk-return balance.

4. Methodology

To evaluate the risk-adjusted performance of Indian technology companies, this study uses a structured performance evaluation approach to see how effectively individual Indian IT companies and a diverse sectoral portfolio pay investors for the risks they take. This builds on the descriptive findings from the preceding section. The study looks at ten leading technology equities and compares them to the Nifty IT Index, which is a proxy for the Indian technology sector, and the Nifty 50 Index, which is a proxy for the whole market. The study assesses standalone and portfolio outcomes to determine if sector diversification improves performance. This approach clearly shows the balance between return and risk for emerging market equities, addressing investor concerns about volatility, drawdowns, and downside protection.

This study examines the Sharpe Ratio (Sharpe, 1966), Sortino Ratio (Sortino & van der Meer, 1991), and Omega Ratio (Keating & Shadwick, 2002), which are frameworks for evaluating return relative to risk.

4.1. Sharpe Ratio

The Sharpe Ratio, introduced by Sharpe (1966), quantifies the return received relative to the risk taken by investors. It is commonly used to compare portfolios because it incorporates portfolio volatility into its calculation. The Sharpe Ratio is given in Equation (1).

where = the portfolio returns.

= the risk-free rate1.

= standard deviation of the portfolio.

A Sharpe ratio greater than zero indicates that a portfolio’s returns exceeded the risk-free rate after adjusting for volatility. The Sharpe ratio shows how adding assets can diversify holdings and lower standard deviation, although this effect is relative to market performance.

4.2. Sortino Ratio

The Sortino Ratio, introduced by Sortino and van der Meer (1991), refines the Sharpe ratio by focusing only on downside risk rather than overall volatility. This approach is useful for volatile assets since it does not penalize portfolios for upward gains. The Sortino Ratio is given in Equation (2).

where and are described above and is the standard deviation of portfolio’s negative returns. The Sortino Ratio focuses on downside volatility, making it a preferred tool for investors evaluating high-risk portfolios.

4.3. Omega Ratio

The Omega ratio (Keating & Shadwick, 2002) compares probability-weighted gains above a chosen threshold to probability-weighted losses below it. Unlike the Sharpe ratio, which relies on the mean and variance, Omega uses the entire return distribution, capturing asymmetric and tail risk. Equation (3) gives the Omega Ratio.

where is the cumulative distribution function (the probability that the return will be less than x), r is a threshold that is determined by the investor, and a and b are integration bounds. This represents the ratio of probability-weighted gains to probability-weighted losses at a chosen threshold (r = 0%).

This study sets the Omega ratio’s threshold return to zero, aligning with past empirical work and using it as a minimum acceptable benchmark. An Omega ratio above one means probability-weighted gains are greater than losses relative to this non-negative threshold.

4.4. Adjusted Sharpe Ratio and Calmar Ratio

As an additional robustness check, we also compute two other risk-adjusted performance metrics, the adjusted Sharpe ratio and the Calmar ratio. We want to make sure that our results are not driven by the implicit assumptions in the Sharpe ratio, which is the most common measure of risk-adjusted return.

The Sharpe ratio is a simple measure of risk-adjusted returns and a standard in the industry. It gauges returns versus volatility under the assumption that they are normally distributed. Because the Sharpe ratio equally penalizes upside and downside volatility, a high Sharpe ratio can mask the actual risk of a strategy with asymmetric returns or exposure to extreme losses in the tails (Mistry & Shah, 2013). With the standard Sharpe ratio, we may overestimate the risk-adjusted returns of strategies that deliver smooth returns during normal market conditions but that are prone to tail risk.

The adjusted Sharpe ratio or modified Sharpe ratio2 is Sharpe ratio adjusted for skewness and kurtosis of the return distribution. The adjusted Sharpe ratio can be used to determine if a high Sharpe ratio is the result of a favorable skew/kurtosis or an artificially high value due to statistical distortions. Hedge funds and many options-based strategies typically have negative skewness and/or excess kurtosis. Therefore, we also calculate the adjusted Sharpe ratio to get a better idea of the strategies’ performance after correcting for the skewness and kurtosis of their returns.

The third risk-adjusted return measure we calculate is the Calmar ratio. The Calmar ratio is defined as the ratio of annualized returns to the maximum drawdown of the investment. In some respects, the Calmar ratio is a more conservative measure than the Sharpe ratio as it does not rely on volatility (which could understate the impact of very rare large drawdowns). The Calmar ratio is used to show the return of a strategy versus the magnitude of the largest drawdown or to see how well the strategy preserves capital.

In addition, Value at Risk (VaR) and Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR) are estimated using a historical, non-parametric approach based on monthly return distributions. This method avoids distributional assumptions and is well suited to capturing tail behavior in volatile equity sectors such as technology. VaR and CVaR estimates are computed at conventional confidence levels and serve as complementary diagnostics to drawdown-based measures rather than as optimization targets.

4.5. Multi-Factor Model Analysis

In addition to computing risk-adjusted returns, this study applies multi-factor models to break down investment returns into systematic risk components like market trends, macroeconomic factors, and sector characteristics, enabling clear and consistent performance attribution.

Factor modeling aims to measure how asset returns respond to different risks. For Indian technology companies in a fast-evolving digital economy, this method is relevant due to their exposure to factors like digital growth, shifting regulations, and global demand for tech services.

To provide robustness to our performance evaluation, we make use of an extended Fama and French (2015) five-factor model with an additional momentum factor.3 The model considers factors such as beta or market risk, size, book-to-market value, profitability, investment, and momentum. Fama and French’s five-factor model (Fama & French, 2015) is an extension to their three-factor model (Fama & French, 1993) to better capture cross-sectional variation in stock returns. This extension includes two new factors: operating profitability and investment. We use this five-factor model in our research along with an additional momentum factor on our sample of Indian tech companies to further improve our explanatory power of their performance, as we can now account for a wider and more complex set of firm-specific and market-wide risk factors.

Momentum, characterized by the propensity of equities with strong historical returns to sustain their performance in the short term, is especially pertinent within the Indian technology sector, where investor sentiment, accelerated innovation cycles, and sector-specific dynamics frequently contribute to persistent performance trends.

Omitting the momentum component in performance evaluation may lead to biased alpha estimates and an incomplete analysis of return drivers, particularly in sectors marked by rapid technological change and speculative capital movement.

Equation (4) presents the five-factor plus momentum model. This model is calculated using monthly returns.

where = the percentage return for firm i in month t.

= the yield on US Treasury bill month t.

= the return on the relevant market index for month t.

This variable is the market risk factor, which indicates the excess return of the overall market and reflects the general risk involved in stock market investment.

(Small minus Big) is the difference in returns between small-cap and large-cap stocks. Calculated as small-cap portfolio return minus large-cap portfolio return, a positive SMB indicates small-caps have outperformed large-caps.

(High minus Low) measures the return difference between value stocks (low price-to-book ratio) and growth stocks (high price-to-book ratio). A positive HML means value stocks outperformed growth stocks.

(Robust minus Weak) factor tracks the return gap between profitable and unprofitable firms, calculated as the difference in returns between portfolios of each. A positive RMW indicates profitable companies have outperformed unprofitable ones.

(Conservative minus Aggressive) measures the return difference between conservative (low investment) and aggressive (high investment) firms. It is calculated by subtracting the returns of aggressive companies from those of conservative ones. A positive CMA means conservative companies outperformed aggressive ones.

(Momentum) = momentum captures the persistence of relative performance of an asset. Momentum refers to the tendency of strong-performing assets to continue rising, while poor performers tend to keep underperforming.

= an error term.

5. Empirical Analysis

Our empirical analysis of Indian technology stocks relative to the benchmark indices begins with correlation assessments and extends to risk-adjusted performance measures and alpha estimation.

5.1. Correlation Analysis

Table 2 displays the correlation coefficients for the monthly returns of ten Indian technology stocks alongside two benchmark indices, the Nifty IT Index and the Nifty 50 Index, covering the period from January 2020 to April 2025. These correlations indicate the degree of alignment between the price movements of these companies and those of the broader market indices.

Table 2.

Correlation of Monthly Returns (January 2020–April 2025).

Table 2 presents the correlation of monthly returns among ten Indian technology stocks, an equally weighted portfolio of them, and various domestic benchmarks from January 2020 to April 2025. These correlations are essential for diversification and risk management.

Technology stocks show moderate to strong correlations, for example, Infosys and HCL Technologies at 0.78, and Infosys and Tech Mahindra at 0.76, indicating similar responses to market conditions. These correlations are influenced by global tech trends, investor sentiment, and sector-wide macroeconomic events.

Coforge and Persistent Systems, despite having somewhat different market capitalizations, still show notable return correlations with large-cap IT stocks, though slightly lower than others. The equally weighted portfolio has strong correlations with all ten stocks (0.70–0.87), showing its returns closely track the group as a whole and help reduce individual stock volatility.

The Nifty IT Index demonstrates strong correlations with both individual stocks and the portfolio, with coefficients above 0.70 for companies and 0.96 for the portfolio. This high correlation is expected since the index includes many of the same stocks and reflects the Indian IT sector’s performance.

The correlations with broader indices such as the Nifty 50 are lower, indicating the distinct characteristics of the tech sector within the Indian market. The correlation between the equally weighted portfolio and the Nifty 50 Index is 0.61, which shows that Indian tech stocks are partially associated with overall market trends but also display independent sector-specific patterns.

Table 2 shows that Indian technology stocks are closely linked to each other and the Nifty IT Index, but have lower correlations with broader Indian indices, indicating potential diversification benefits.

5.2. Analysis of Risk-Adjusted Returns

Table 3 compares Indian technology stocks, an equally weighted portfolio, and major indices using five risk-adjusted performance measures: Sharpe Ratio, Adjusted Sharpe Ratio, Sortino Ratio, Omega Ratio, and Calmar Ratio.

Table 3.

Risk-adjusted return ratios for Indian Technology Stocks, equally weighted portfolio of ten Indian technology stocks and Market Indices (January 2020 to April 2025).

Table 3 reports five risk-adjusted performance metrics, Sharpe, Sortino, Omega, Adjusted Sharpe, and Calmar ratios, for ten Indian technology stocks, their equally weighted portfolio, and selected Indian market indices, using data from January 2020 to April 2025.

Persistent Systems was the undisputed top performer, sporting a uniform pattern of positive figures across all five measures, including a Sharpe ratio of 0.19, Sortino of 0.47, Omega of 1.90 and the highest Calmar ratio (2.00). The results reflect the company’s ability to generate steady excess returns while maintaining modest drawdowns, resulting in an appealing risk-adjusted proposition for investors. Coforge reported positive numbers too, with a Calmar ratio of 0.77, but its performance wasn’t as strong as Persistent’s. HCL Technologies had a Calmar ratio of 0.73, indicating that the company displayed relatively good downside risk control despite its marginally negative Sharpe and Sortino ratios. LTIMindtree and L&T Technology Services had modestly positive Sortino and Omega ratios with Calmar ratios in the 0.43–0.48 range, indicating some but limited resilience.

In contrast, large-cap stocks like Infosys, TCS, Tech Mahindra and Wipro had negative Sharpe and Sortino ratios, Omega numbers less than 1 and poor Calmar ratios (all less than 0.45). These figures indicate that the biggest firms failed to provide investors with adequate compensation for their risk.

At the portfolio level, the equally weighted basket of these 10 firms reported a slightly negative Sharpe ratio (−0.06) but positive Sortino (0.01), Omega (0.53) and Calmar (0.73) ratios. For the equally weighted portfolio, an Omega ratio below unity reflects the persistence of downside risk during extreme market episodes, despite improvements in drawdown-based measures such as the Calmar ratio.

The benchmarks, the Nifty IT Index, reported a Calmar ratio of 0.55 and negative Sharpe and Sortino values, pointing to weak draw-down-adjusted performance at the sector level. The Nifty 50 Index fared even poorer, posting a Calmar ratio of 0.49 and uniformly negative numbers across the other metrics. Taken together, these results suggest that, although performance among Indian tech companies has been highly uneven, certain mid-caps such as Persistent Systems and Coforge posted superior risk-adjusted outcomes relative to their large-cap peers and the market at large.

5.3. Rolling Sharpe Ratio

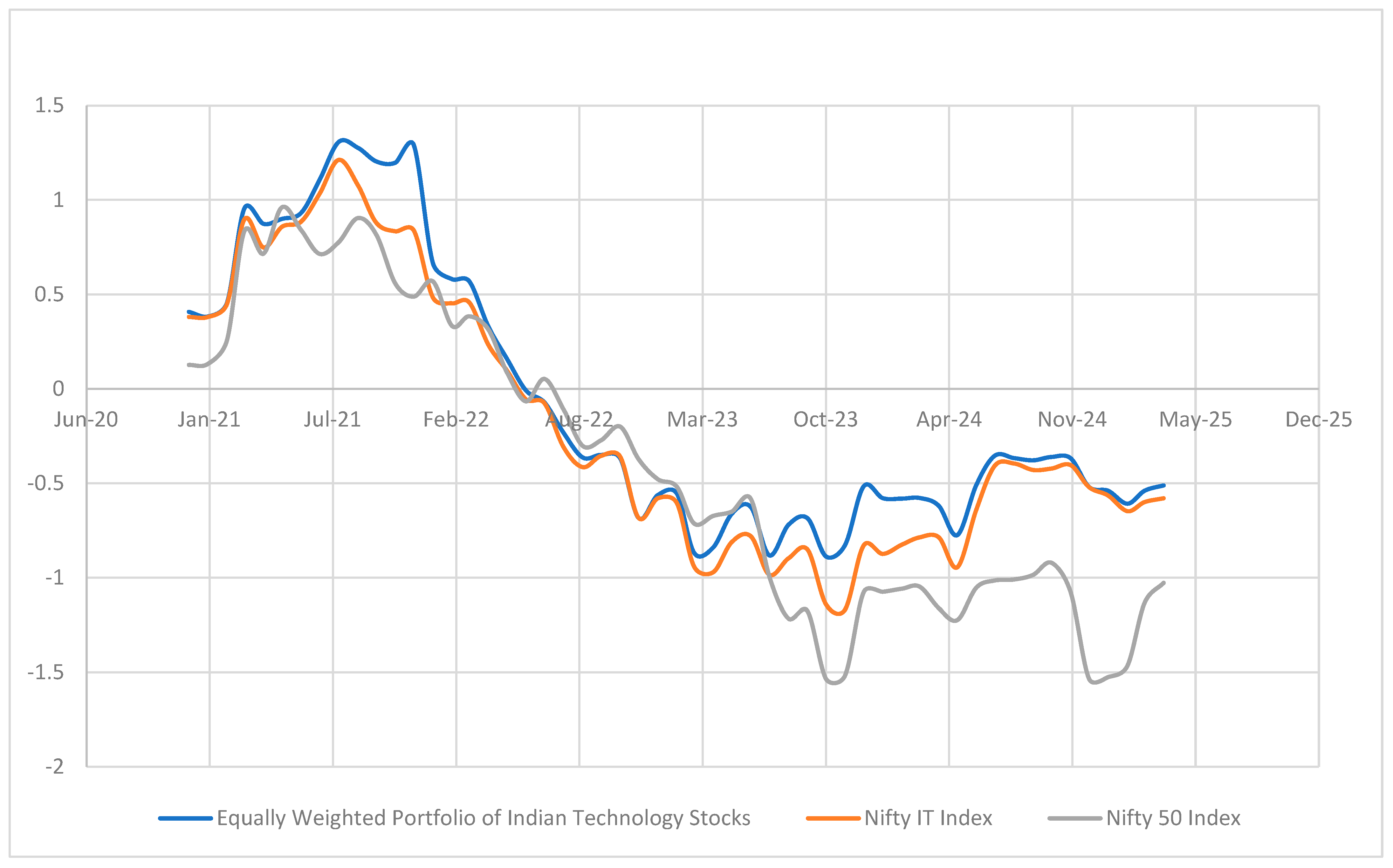

The 12-month rolling Sharpe ratio was calculated for Indian technology stocks, the Nifty IT Index, and the Nifty 50 Index over the period from January 2020 to April 2025. This method monitors the variation in risk-adjusted returns during periods such as the COVID-19 downturn, subsequent recovery, and recent macroeconomic developments. Figure 1 displays these ratios for the ten largest Indian technology companies alongside benchmark indices.

Figure 1.

Twelve-month rolling monthly Sharpe ratio for top 10 Indian Technology Companies, an equally weighted portfolio of top ten Indian Technology Companies, Nifty IT Index, and Nifty 50 Index (January 2020 to April 2025).

The time-varying Sharpe ratios also reflect distinct market regimes, including the sharp deterioration during the COVID-19 shock, the subsequent recovery phase, and periods of normalization amid tightening global financial conditions. These dynamics highlight the importance of evaluating risk-adjusted performance across market cycles rather than relying solely on full-sample averages.

The 12-month rolling Sharpe ratios suggest that diversifying within sectors primarily strengthens the portfolio’s ability to weather downturns, rather than consistently outperforming the market. The portfolio’s Sharpe ratio frequently aligns with or slightly exceeds that of the Nifty IT Index, and it generally remains above the Nifty 50. This supports the notion that blending mid-cap growth with the stability of large-cap stocks helps to mitigate volatility when the market is under pressure.

However, the portfolio’s performance is marked by frequent fluctuations and periods of negative returns, highlighting the fact that risk-adjusted returns for Indian technology equities are significantly influenced by current market conditions. Strong performance tends to occur in short, intense periods, particularly during market recoveries, while downturns quickly erase those gains. In short, while sector diversification improves stability and provides downside protection, it does not ensure sustained outperformance compared to benchmarks.

These findings show that risk-adjusted performance varies over time and stress the need to review strategies through different market cycles. The technology portfolio’s higher averages and peaks indicate that intra-sector diversification can improve returns, especially in volatile growth sectors.

5.4. Empirical Analysis of Multi-Factor Model

Table 4 reports the net monthly alpha values from a six-factor model (Mkt-Rf, SMB, HML, RMW, CMA, MOM) for ten leading Indian technology firms, their equally weighted portfolio, and benchmark indices. These alphas indicate monthly returns not captured by common risk factors, highlighting firm-specific performance. We use Fama–French emerging market factors for Fama–French five-factor plus momentum model (http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/data_library.html#International; accessed on 2 December 2025).

Table 4.

Net monthly alphas for top ten Indian technology companies and equally weighted portfolio (January 2020 to April 2025). T-statistics are reported in parentheses.

Table 4 presents the estimated net monthly alphas and factor loadings for the ten largest Indian firms and their equally weighted portfolio over the period from January 2020 to April 2025. To compute these risk-adjusted performance measures, we employ the Fama and French (2015) five-factor model augmented with Carhart’s (1997) momentum factor. The risk factors include market risk, size (SMB), value (HML), profitability (RMW), investment (CMA), and momentum (MOM). These factors enable us to understand whether the observed stock returns are the result of systematic factor exposures or due to firm-specific alpha generation. The estimation results provide several important insights that are broadly consistent with the existing factor-based literature.

First, we observe that Persistent Systems Limited is the only firm in the sample that produces a statistically significant and positive alpha of 2.79 percent per month (t-statistics at the 10 percent level). This suggests that the returns earned by Persistent Systems are not completely explained by systematic risk premium, consistent with Sharpe’s (1966) definition of alpha as a measure of superior performance. Persistent Systems also showed positive and statistically significant exposures to both the size and profitability factors. This is broadly in line with Fama and French’s (2015) finding that small and profitable firms receive a positive premium. At the same time, the ability of Persistent to produce positive alpha also resonates with the evidence on stock-selection skill found in a survey of Indian fund managers (Deb et al., 2007; Malhotra et al., 2024), but in this case at the firm level rather than the fund level.

In contrast, all four large-cap incumbents in the sample, Infosys, Tata Consultancy Services, Wipro, and Tech Mahindra, have negative and statistically insignificant alphas. The returns earned by these firms can be almost entirely explained by their systematic factor exposures. All four firms have significant exposure to momentum, while Infosys, Tata Consultancy Services, and Wipro also have strong and significant exposures to profitability. These results are consistent with the evidence on stability, but lack of excess performance previously documented in individual Indian equities (Parthasarathi & Joseph, 2002; Aziz & Ansari, 2017).

Two mid-tier firms in the sample, Coforge and HCL Technologies, have positive but statistically insignificant alphas. The former has exceptionally high sensitivity to the size factor which, as Fama and French (2015) have shown, is similar to other small-cap firms. It also has strong and statistically significant profitability exposure, consistent with factor-based explanations of returns (Fama & French, 2015). These patterns suggest that while returns are mostly explained by factor characteristics, they do not automatically imply positive alpha generation.

At the portfolio level, we find that the equally weighed portfolio of all ten firms produces a low and statistically insignificant alpha of 0.13 percent per month. This implies that the aggregate performance of the Indian technology sector does not provide returns above those that can be explained by its exposure to systematic risk factors. On the other hand, the portfolio has strong and statistically significant exposures to market (1.14), size (1.64), profitability (1.74), and momentum (0.84). These estimates are consistent with existing studies that show the strong interconnectedness and factor dependence of Indian equities in emerging markets (Raddant & Kenett, 2020).

We can draw two conclusions from our results. First, the importance of active stock selection within the Indian technology sector. Firms such as Persistent Systems clearly stand out and produce positive abnormal performance, whereas most large-cap incumbents clearly underperform after accounting for risk factors. Second, we find no evidence of statistically significant alpha generation at the portfolio level, implying that exposure to the Indian technology equity space is mostly an exposure to systematic risk factors (market, SMB, RMW, and MOM in particular) rather than excess returns that are consistently earned over time. This also resonates with earlier studies that argued for more advanced performance measures than simple Sharpe ratios for high volatility and high-kurtosis sectors (Keating & Shadwick, 2002; Eling & Schuhmacher, 2007). For the portfolio manager or investor, this finding has important implications for the design of an equity portfolio. Rather than passively investing in sector-level indices, evidence in this paper points to the importance of careful firm-level analysis and active stock selection when seeking superior investment outcomes.

Table 5 summarizes net monthly alpha and R-squared (R2) for ten Indian technology firms, their equally weighted portfolio, and benchmark indices, supplementing the six-factor regression. Alpha reflects firm-level performance not explained by risk exposure, while R2 indicates how much stock return variance the model accounts for.

Table 5.

Net monthly alphas for top ten Indian technology companies, an equally weighted portfolio of Indian technology companies, and benchmark indices (January 2020 to April 2025).

As noted earlier, Persistent Systems and Coforge have the highest monthly alpha of 2.79 percent among all companies, which shows that they are still doing better than the rest. But these companies also have low R2 values of 0.21, which means that a lot of their return variability comes from factors that are distinctive to the company or not systematic and are not included in the six-factor model.

Conversely, the highest R2 is reported by Wipro at 0.375, though it has a considerably negative alpha (−0.80 percent). This means that though Wipro returns are less influenced by idiosyncratic risk and more by systematic risk factors, the stock has underperformed all other peers on a risk-adjusted basis, even after considering its sensitivities to different factors. A similar conclusion could be drawn for Tech Mahindra and HCL Technologies, which show relatively higher R2 numbers (0.337 and 0.320, respectively) but a negative or low alpha. This means that these two stocks can have their returns more accurately predicted based on factor sensitivities, without providing any additional compensation to investors.

The equally weighted portfolio of all 10 technology firms has an R2 of 0.417, the highest across all series reported, but with a modest alpha of 0.13 percent. The result shows that although the portfolio generates small excess returns, most of the return variation can be explained by the exposures to systematic risks. The fact that this portfolio also has a positive alpha is an indication of the value of diversification to reduce firm-specific noise while maintaining exposures to beneficial factors such as size and profitability.

Benchmark indices offer a useful point of comparison. The Nifty IT Index shows a negative alpha (−0.32%) and a high R2 of 0.420, suggesting a strong dependence on systematic risk exposures without any added performance premium. The Nifty 50 Index exhibits the highest R2 at 0.779, consistent with its broad market composition and deep liquidity, but it too posts a negative alpha (−0.24%), indicating underperformance relative to factor expectations.

Table 5 shows three important points: Companies like Persistent Systems and Coforge that do well provide a lot of stock-specific value that is not explained by normal risk considerations. Companies with the greatest R2 typically have little or no alpha, which shows that being predictable does not mean getting large returns. Diversified sector portfolios balance systematic exposure with alpha, which makes them good for investment that takes risk into account.

5.5. Empirical Analysis of Downside Risk

Table 6 reports the 95 percent Value at Risk (VaR) and Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR), or Expected Shortfall, for ten Indian technology stocks, their equally weighted portfolio, as well as major sector specific and domestic equity indices. These risk measures indicate potential losses under adverse market conditions and are relevant for assessing tail risk and capital preservation during market downturns.

Table 6.

Ninety-five percent Value-at-Risk and Expected Shortfall for top ten Indian Technology stocks and benchmark indices.

Value at Risk (VaR) is the largest possible loss that might happen with 95% certainty over a certain period of time. Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR), which is sometimes called expected shortfall, looks at the average of the worst 5% of instances to quantify risk and show the extent of a tail event. Using these measurements together gives a more thorough picture of how risky an asset is.

The findings indicate significant disparities in downside risk across individual stocks. L&T Technology Services exhibited the greatest risk, reporting a Value at Risk (VaR) of −15.94% and a Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR) of −20.30%. On average, losses exceeded 20% during the most adverse 5% of scenarios. LTIMindtree, Tech Mahindra, and Coforge also have CVaRs around −20%, indicating significant downside exposure, consistent with their high volatility and aggressive investment profiles.

In contrast, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) exhibits the lowest downside risk among individual stocks, with a VaR of −7.02 percent and a CVaR of −10.26 percent, consistent with its large-cap status, conservative financial strategy, and relative stability. Infosys and HCL Technologies also demonstrate moderately lower downside risk, though their CVaRs still exceed −13 percent, suggesting that even the most stable firms are not immune to significant losses during extreme market conditions.

The equally weighted portfolio of the ten technology stocks records a VaR of −11.82 percent and a CVaR of −15.15 percent, reflecting a lower risk profile than most of its individual constituents. This supports the conclusion that diversification within the Indian technology sector offers meaningful downside protection, smoothing extreme losses and mitigating firm-specific shocks.

Benchmark comparisons further underscore the risk-return trade-off. The Nifty 50 Index, representing the broader Indian equity market, reports the lowest downside risk metrics, with a VaR of −5.58 percent and a CVaR of −10.43 percent. These values are consistent with their broad diversification and sectoral balance. In contrast, the Nifty IT Index, though technology-focused, shows a VaR of −9.26 percent and CVaR of −12.90 percent, less risky than the equal-weighted tech portfolio but more exposed than the general market index.

Table 6 shows that Indian technology shares possess much more downside risk compared to Indian broad market indices. The significant variation across corporations underscores the need to do risk analysis at the stock level. The reduced CVaR of the equally weighted portfolio illustrates the need to diversify investments across several asset classes to mitigate the risk of substantial losses. These factors are essential for investors and portfolio managers cognizant of risk, particularly those seeking to maximize returns while safeguarding against losses in a volatile market.

5.6. Portfolio Optimization

While the downside risk metrics in Table 6 highlight the vulnerability of Indian technology equities to sharp losses, it is equally important to assess how these stocks interact within an optimized portfolio framework. To extend the analysis beyond stock-level and equal-weight portfolios, we solve three canonical allocation problems: the Markowitz mean–variance optimization (maximizing the Sharpe ratio), the global minimum variance (GMV) portfolio, and a risk parity allocation. These methods provide a richer understanding of how Indian technology equities, when considered alongside the Nifty 50 benchmark, contribute to efficiency, diversification, and stability in a portfolio setting.

All portfolios in this study are long-only, with no short selling. Transaction costs, turnover limits, and rebalancing frictions are excluded to focus on structural diversification and risk-return profiles, enabling straightforward comparisons between single equities, diversified portfolios, and benchmarks.

Table 7 summarizes portfolio-level performance metrics for the optimization strategies shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Portfolio Performance Metrics under Markowitz, GMV, and Risk Parity (January 2020–April 2025).

Table 7 shows mean excess return over the risk-free rate, volatility, and Sharpe ratio. The Markowitz portfolio achieves the highest risk-adjusted return but with significant concentration risk. The GMV portfolio achieves the lowest volatility but delivers modest returns. Risk Parity provides balanced exposure across Indian technology firms and the Nifty 50 benchmark, producing intermediate risk-return trade-offs and greater robustness. Results underscore the trade-offs between efficiency, concentration, and diversification in portfolio construction with Indian technology equities.

The findings demonstrate a clear trade-off. The Markowitz portfolio offers the highest risk-adjusted return, but at the expense of significant concentration, with nearly three-quarters of its weight in Persistent. This leaves investors highly exposed to firm-specific risk. The GMV allocation, on the other hand, prioritizes stability by focusing on TCS and the Nifty 50 benchmark. However, it results in modest returns and a relatively low Sharpe ratio. In contrast, the risk parity portfolio strikes a balance, with more evenly distributed weights across the technology firms and the benchmark. This approach achieves intermediate volatility and returns while avoiding excessive concentration.

These results highlight the inherent trade-off between pursuing maximum efficiency and maintaining diversification. Based on this analysis, the evidence suggests that a thoughtful combination of Indian technology equities with the Nifty 50 benchmark can enhance portfolio outcomes. Mid-cap disruptors like Persistent contribute to growth, while large-cap stalwarts such as TCS and broad-market exposure through the Nifty 50 enhance resilience.

5.7. Discussion and Implications

This study provides three main takeaways on alpha and the role of Indian technology equities in a portfolio. The study finds that alpha generation is driven by mid-cap disruptors (Persistent Systems and Coforge), while the large-cap incumbents (Infosys, TCS, and Wipro) play a more stabilizing role in the portfolio and do not contribute to abnormal returns. Second, a combination of growth mid-caps and more mature firms beats the Nifty IT Index and Nifty 50 Index, indicating that intra-sector diversification is a good idea. Finally, downside risk measures highlight the sector’s fragility and potential for significant losses, once again underscoring the importance of prudent portfolio construction and risk management.

Table 7 reports portfolio optimization results that build on these conclusions, highlighting how different allocation rules shape the tradeoff between efficiency, diversification, and concentration. The Markowitz solution realized the highest Sharpe ratio but at the cost of extreme concentration risk, with nearly ¾ of the portfolio allocated to Persistent and a small stake in the Nifty 50 benchmark. The Global Minimum Variance portfolio increased exposure to TCS and the Nifty 50 benchmark, confirming the stabilizing role of the former and the diversification benefits of broad market exposure but at the cost of reduced returns. In contrast, the Risk Parity solution focused on equalizing risk contributions across firms and anchoring on the Nifty 50 benchmark, leading to a more intermediate result with respect to risk-adjusted performance and resilience. These results highlight the role of Indian technology equities in portfolio efficiency, which, in addition to arising from selective high-return firms, also comes from their interplay with broad benchmarks that deliver diversification benefits.

These findings have a number of potential applications for investors. For institutional investors, the concept of risk parity offers a natural starting point for portfolio allocations that provide a reasonable balance between diversification and performance. Selective tilts toward higher-return firms like Persistent can be added on top of this base case to pursue growth without destabilizing the portfolio. For ETF providers, our results point to an opportunity to create products that blend concentrated exposure to high-growth technology firms with weights on broad benchmarks that can play a stabilizing role. A product of this type would enable investors to participate in the growth story of Indian technology while mitigating the concentration risk associated with single-firm allocations.

6. Summary and Conclusions

This study evaluated the risk-adjusted performance of ten leading Indian technology firms from January 2020 to April 2025, with comparisons to sectoral and market benchmarks. Alpha generation appears concentrated in the mid-cap disruptors Persistent Systems and Coforge, while large-cap incumbents Infosys, TCS, and Wipro act as ballast without significant excess returns. The equally weighted portfolio of all 10 firms provided outperformance versus both the Nifty IT Index and the Nifty 50 Index, demonstrating the benefits of intra-sector diversification. However, downside risk confirmed that Indian technology equities are prone to sharp drawdowns, and careful risk management and portfolio construction is required.

While equal weighting implicitly reduces concentration risk relative to capitalization-weighted benchmarks, future research may explicitly incorporate concentration metrics such as the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index or marginal risk contribution analysis. Such extensions would further clarify the trade-off between concentration, diversification, and downside risk within sector-focused portfolios.

Portfolio optimization added additional nuance to these observations. The Markowitz solution provided the highest Sharpe ratio, but was highly concentrated in Persistent, leaving investors vulnerable to idiosyncratic shocks. The Global Minimum Variance solution tilted more heavily to TCS and the Nifty 50, providing stability but limiting upside. The Risk Parity solution provided a more balanced mix of exposure to individual firms and the benchmark delivering intermediate performance but with more resilience. Investors may take away from these findings that risk parity provides a convenient baseline that can be supplemented with active tilts to higher-return firms, while ETF providers can consider products that blend exposure to growth with some benchmark stability. Adding Indian technology stocks can boost portfolio efficiency when balanced with risk and return.

While this study focuses on the Indian technology sector, the empirical framework developed here lends itself naturally to broader comparative analysis. An important direction for future research is the application of this methodology to other equity markets, including both emerging economies such as Brazil, Mexico, China, and South Africa, as well as developed markets in the United States, Europe, and Japan. Such extensions would allow researchers to examine whether the observed heterogeneity in alphas, the role of momentum, and the benefits of intra-sector diversification are features specific to the Indian market or whether they persist across markets with different levels of liquidity, institutional development, and informational efficiency. A comparative perspective across emerging and developed markets may also shed light on structural differences in market depth, sensitivity to global macroeconomic factors, and the persistence of risk premiums.

Furthermore, future work could explore whether active stock selection and diversification within a sector generate systematically different outcomes depending on the maturity of the market. In addition, extending the analysis from individual stocks to sectoral indices, both within technology and across other key sectors such as financials, energy, healthcare, and consumer discretionary, would help assess the robustness of the findings at a higher level of aggregation. Such work would also enable a clearer distinction between the roles of intra-sector diversification and cross-sector diversification in managing downside risk and improving risk-adjusted performance. Taken together, these extensions would position the present study not only as a sector-specific empirical analysis, but also as a flexible methodological framework for examining risk, return, and diversification across markets and sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K.M.; Methodology, D.K.M. and S.B.; Validation, D.K.M. and R.S.; Formal analysis, D.K.M.; Investigation, D.K.M. and R.S.; Data curation, S.B. and R.S.; Writing—original draft, D.K.M.; Writing—review and editing, S.B. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data derived from public domain resources and Data is also available on request from authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Returns are reported in Indian rupees. The three-month U.S. Treasury bill rate serves as the risk-free rate, aligning with Fama–French factor datasets and reflecting an international investor’s perspective on Indian technology stocks. While using an Indian risk-free rate could affect excess-return figures, the U.S. Treasury bill is standard in global asset-pricing research for consistent market comparison. The study focuses on relative performance, factor exposures, and abnormal returns, not absolute excess-returns. The sample period covers near-zero rates and later monetary tightening, making the U.S. Treasury bill a relevant benchmark for global financial trends affecting emerging markets. |

| 2 | For the formula for computing adjusted Sharpe ratio, please refer to Pezier and White (2006); Calmar ratio = Annual Return/Maximum Drawdowns. |

| 3 | The factor returns employed in this study are drawn from the Fama–French Emerging Market factor library rather than India-specific factor constructions. While this approach ensures data availability and methodological consistency, it may introduce measurement noise if local risk premia differ from broader emerging market dynamics. Nevertheless, emerging market factors are widely used in empirical studies of Indian equities and provide a reasonable approximation of systematic risk exposures. Future research may extend this analysis by employing India-specific factor sets or alternative momentum definitions, such as 12–2-month momentum, as longer and more granular datasets become available. |

References

- Aziz, T., & Ansari, V. A. (2017). Idiosyncratic volatility and stock returns: Evidence from the Indian stock market. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 11(3), 288–305. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23322039.2017.1420998 (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Carhart, M. M. (1997). On persistence in mutual fund performance. Journal of Finance, 52, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S. G., Banerjee, A., & Chakrabarti, B. B. (2007). Market timing and stock selection ability of mutual funds in India: An empirical investigation. Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers, 32(2), 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, M., & Schuhmacher, F. (2007). Does the choice of performance measure influence the evaluation of hedge funds? Journal of Banking & Finance, 31(9), 2632–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. (1993). Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33(1), 3–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2015). A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics, 116(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, C., & Shadwick, W. F. (2002). A universal performance measure. Journal of Performance Measurement, 6(3), 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, D. K., & Singh, R. (2025). The role of Indian equity exchange-traded funds in diversified portfolios: A risk-adjusted performance analysis. Journal of Investment Strategies, 14(2), 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, D. K., Singh, R., & Ramani, L. (2024). Navigating market volatility: Risk and return insights from Indian mutual funds. Cogent Economics & Finance, 12(1), 2431535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J., & Shah, J. (2013). Dealing with the limitations of the sharpe ratio for portfolio evaluation. Journal of Commerce and Accounting Research, 2(3), 10–20. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3413284 (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Parthasarathi, A., & Joseph, K. J. (2002). Limits to innovation with strong export orientation: The case of India’s information and communication technology sector. Science, Technology and Society, 7(1), 13–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezier, J., & White, A. (2006). The relative merits of investable hedge fund indices and of funds of hedge funds in optimal passive portfolios. ICMA Centre Discussion Papers in Finance DP2006-10. Henley Business School, University of Reading. [Google Scholar]

- Raddant, M., & Kenett, D. Y. (2020). Interconnectedness in the global financial market. Journal of International Money and Finance, 109, 102238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, W. F. (1966). Mutual fund performance. The Journal of Business, 39(1), 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sortino, F. A., & van der Meer, R. (1991). Downside risk. Journal of Portfolio Management, 17(4), 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T. W. (1991). Calmar ratio: A smoother tool. Futures. [Google Scholar]

- Zakamouline, V., & Koekebakker, S. (2009). Portfolio performance evaluation with Adjusted Sharpe ratios: Beyond the mean and variance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(7), 1242–1254. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.