1. Introduction

Financial literacy, delineated as the knowledge and skills that facilitate informed positive decision-making about budgeting, saving, investing, and managing credit (

Mulla, 2022), is proposed to limit risk and exposure to debt for individuals and help them to make better investment decisions (

Liu et al., 2024). Despite the ease of access to financial products, many populations have not acquired financial literacy to achieve positive financial behaviors. As such, the roles of financial literacy and financial behavior in achieving financial well-being are key to achieving positive financial outcomes (

Choung et al., 2023). Fintech also contributes to improving financial behavior in budgeting, saving, and investing; however, better comprehending Fintech products leads to maximizing the use and benefits of their offerings (

Alamelu, 2024). Fintech has changed the way people manage their finances, particularly for the millennial generation, who use personal finance apps to track spending daily, create a budget, and make informed decisions that impact their financial wellness (

Cardoso et al., 2024).

Nguyen (

2024) highlights that millennials, in developed economies, prefer Fintech services because they are easier and more efficient.

Within the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) context, notable heightened areas within the realm of behavioral finance encompass the focus on regulatory gaps, digital literacy, and trust issues (

Elouaourti & Ibourk, 2024). Across the Lebanese landscape, the rise of Fintech has been hampered by the low level of financial literacy, and there is a noticeable lack of prior literature on Fintech-related usage and adoption.

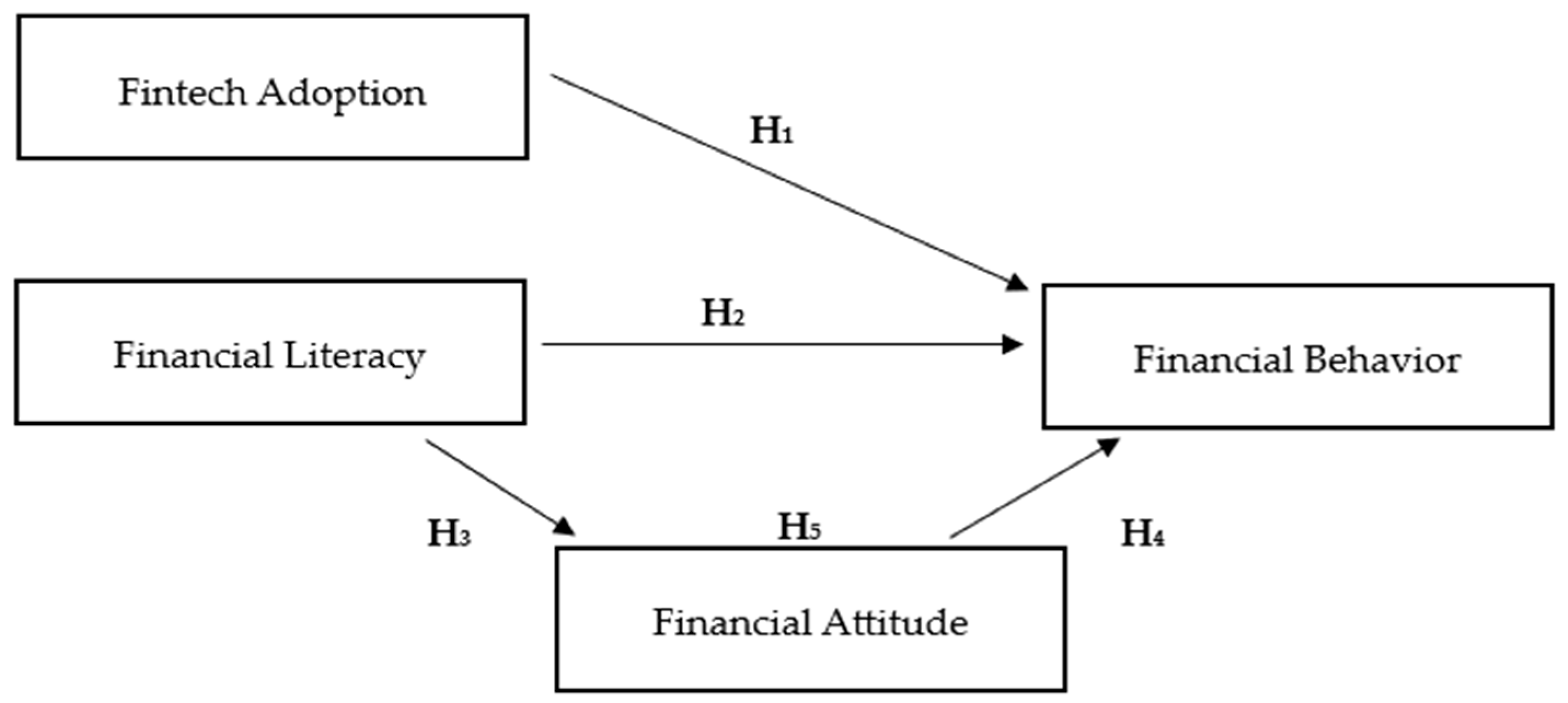

Hence, this research seeks to fill this gap, and the objective is three-fold, as it aims to examine the connection between Fintech adoption and the financial behavior adoption of Lebanese millennials, along with exploring the correlation between financial literacy and the financial behavior of these targeted millennials, and to investigate whether financial attitude serves as a mediator between financial literacy and financial behavior. These variables become especially relevant in Lebanon due to the country’s prolonged economic collapse, currency devaluation, capital controls, and declining trust in the financial system. Millennials increasingly rely on digital financial solutions and personal financial competencies to navigate daily financial decisions. As a result, understanding how financial literacy, financial attitudes, and FinTech adoption jointly influence financial behavior is critical in a crisis-affected context where traditional financial guidance and institutional support are limited. The context of economic turmoil, inflation, and issues in Lebanon’s banking system makes it important to understand how millennials engage with digital financial services (

Bejjani et al., 2024;

Sawaya et al., 2023).

The three core constructs examined in this study, namely FinTech adoption, financial literacy, and financial attitude, collectively shape how millennials engage in financial behavior. Financial literacy forms the cognitive foundation enabling individuals to interpret financial information and evaluate choices. Financial attitudes capture the psychological and evaluative orientations toward money, influencing how literacy is translated into actual behavior. FinTech adoption represents the practical behavioral channel through which individuals execute, manage, and monitor financial activities. To ground this investigation theoretically, the study adopts Behavioral Finance Theory (BFT), which recognizes that individuals’ financial decisions are shaped by cognitive processing, psychological biases, and contextual influences. Together, these elements align with BFT, which posits that financial behavior emerges from the interaction of knowledge, perceptions, and the tools individuals use. Accordingly, examining these constructs jointly provides a comprehensive lens for understanding millennials’ financial behavior within Lebanon’s crisis context.

This study makes three key contributions to the literature on financial behavior in emerging markets. First, it integrates FinTech adoption, financial literacy, and financial attitude within a unified behavioral finance model, offering a more holistic understanding of millennials’ financial decision-making. Second, it provides novel empirical insights from Lebanon, a crisis-affected and institutionally fragile economy where data on FinTech use and financial behavior are scarce. Third, by validating the mediating role of financial attitudes, the study extends the BFT to account for psychological and attitudinal factors that shape financial behavior in uncertain and high-risk environments. These contributions offer both theoretical advancement and practical guidance for scholars, policymakers, and financial institutions.

Three pivotal research questions guide this study:

RQ1. What is the role of Fintech adoption in millennials’ financial behavior?

RQ2. What is the role of financial literacy in millennials’ financial behavior?

RQ3. Do financial attitudes mediate the relationship between financial literacy and financial behavior?

Although the conceptual relationships between financial literacy, financial attitude, and financial behavior have been widely documented, their dynamics in crisis-affected economies remain markedly underexplored. In Lebanon, a context characterized by institutional collapse, hyperinflation, and the erosion of public trust in the financial system, these behavioral relationships are likely to function differently than in stable markets. Thus, the contribution of this study is not rooted in proposing a novel theoretical path but in demonstrating how well-established behavioral mechanisms operate, and in some cases intensify, under extreme economic instability. By providing large-scale empirical evidence from a severely fragile financial environment, the study extends existing behavioral finance knowledge into settings where traditional assumptions about rationality, trust, and risk no longer hold.

4. Research Context

Across the Lebanese context, Fintech’s maturation period is finally establishing initiatives for digital infrastructure modernization, driven by the rapid growth of digital banking and payments. Banque du Liban’s Circular 331 is intended to support Fintech innovation through incentives for equity investors in early-stage startups. Nonetheless, the foray into Fintech blockchain and cryptocurrency information is met with hesitancy due to legal uncertainty, lack of trust, and predominantly cash-based, informal economy structures. Increased internet and smartphone penetration assist in technology and Fintech adoption, as mobile wallets are proliferating in Lebanon, with OMT, Whish, and BOB Finance being widely adopted amid enduring banking restrictions (

Boustani, 2020). Lending models, namely, peer-to-peer lending (P2P) lending and crowdfunding, are also emerging, although Fintech lending continues to face regulatory, as well as structural, hurdles (

Tarhini et al., 2016).

The millennial generation is the most significant demographic to adopt Fintech commercial models, using mobile-based financial innovations as an alternative to traditional banking products and services within a stagnant economic environment (

Abu Alrub et al., 2020). Many Lebanese millennials demonstrate a lack of knowledge in essential areas such as budgeting, investing, and debt management. Lebanon is among the lowest in financial literacy when compared to countries like the UAE and Qatar. Financial education efforts in the region have been sporadic and generally ineffective, and Lebanon lacks consistent educational programs (

Makdissi & Mekdessi, 2024). As such, this current study focuses on the financial literacy and behavior of millennials, especially concerning fintech, to help bridge gaps in decision-making in today’s digital financial landscape amidst ongoing instability.

Regarding the Lebanese ecosystem, many Lebanese lost access to their savings since the crisis resulted in severe capital and banking limitations, which eroded public confidence in the financial system (

Mawad et al., 2022). Following the collapse of the Lebanese pound, with a loss of over 90%, hyperinflation has reduced purchasing power considerably, with many families now living in poverty, and the informal economy has expanded tremendously. Cash transactions have become commonplace due to their anonymity and to avoid banking limits (

Elhajjar, 2023). Concurrently, digital financial solutions, such as cryptocurrencies as a hedge against currency devaluation (

El-Chaarani et al., 2023). Millennials have begun adjusting their financial behaviors by embracing informal, flexible, and digitally driven approaches, such as the use of mobile payments and digital wallets, despite regulatory concerns (

Abu Daqar et al., 2021). While fintech does present alternative options, financial illiteracy continues to pose a risk to users by exposing them to poor financial decisions, fraud, and scams (

Dermesrobian, 2023).

Bizri et al. (

2018) noted that the multi-religious society of Lebanon influenced financial decisions, especially when looking at principles of Islamic finance as a proxy for financial attitudes towards banking, loans, and investment behavior among Muslim millennials. Plus, according to

Abou Ltaif and Mihai-Yiannaki (

2024), Lebanese millennials have become more risk-averse to various economic crises, notably the financial collapse of 2019. This risk aversion can be expressed by a preference for saving rather than spending or perhaps pursuing more moderate investment styles.

Millennials’ financial mindset in Lebanon is further influenced by their socioeconomic status and education, as well as their access to financial services. As the Lebanese economy continues to face enormous hardship (e.g., hyperinflation, a depreciated currency, and political disequilibrium), Lebanese millennials’ financial orientation is majorly affected. Many millennials lack access to traditional financial products or credit and are exploring alternatives outside the conventional financial sector to save and invest or access loans (

Mawad et al., 2022;

Domat, 2022). For example, Lebanese millennials are likely to engage in modern finance, such as budgeting, investing, and retirement planning, yet because many are unemployed or underemployed, they do not have the resources to save or invest, which creates disconnection and division in financial orientation and perspective (

El-Chaarani et al., 2023).

In a nutshell, although Fintech adoption is growing, challenges like frugality, limited financial education, and unclear regulations continue to affect Lebanese millennials’ financial behavior. The ongoing economic challenges only make these issues more difficult. Hence, there is a clear need for better financial education and clearer regulations to help millennials take full advantage of entrepreneurial opportunities. All these conditions make Lebanon an appropriate setting for analyzing how knowledge, attitudes, and digital financial tools collectively shape financial behavior.

6. Methodology

6.1. Research Design

A positivist philosophy was followed, and the reasoning in this explanatory study is deductive, alongside a mono-quantitative methodological choice. As such, a self-report survey was employed using closed-ended questions for demographics, and five-point Likert scale statements for the studied variables (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree). Given the absence of publicly available national data on Fintech adoption, financial literacy, financial attitudes, and financial behavior in Lebanon, the use of a primary questionnaire was both necessary and justified. Moreover, considering the relevance and urgency of the topic amid Lebanon’s ongoing economic crisis, this approach provides timely, context-specific insights into a critically underexplored population segment.

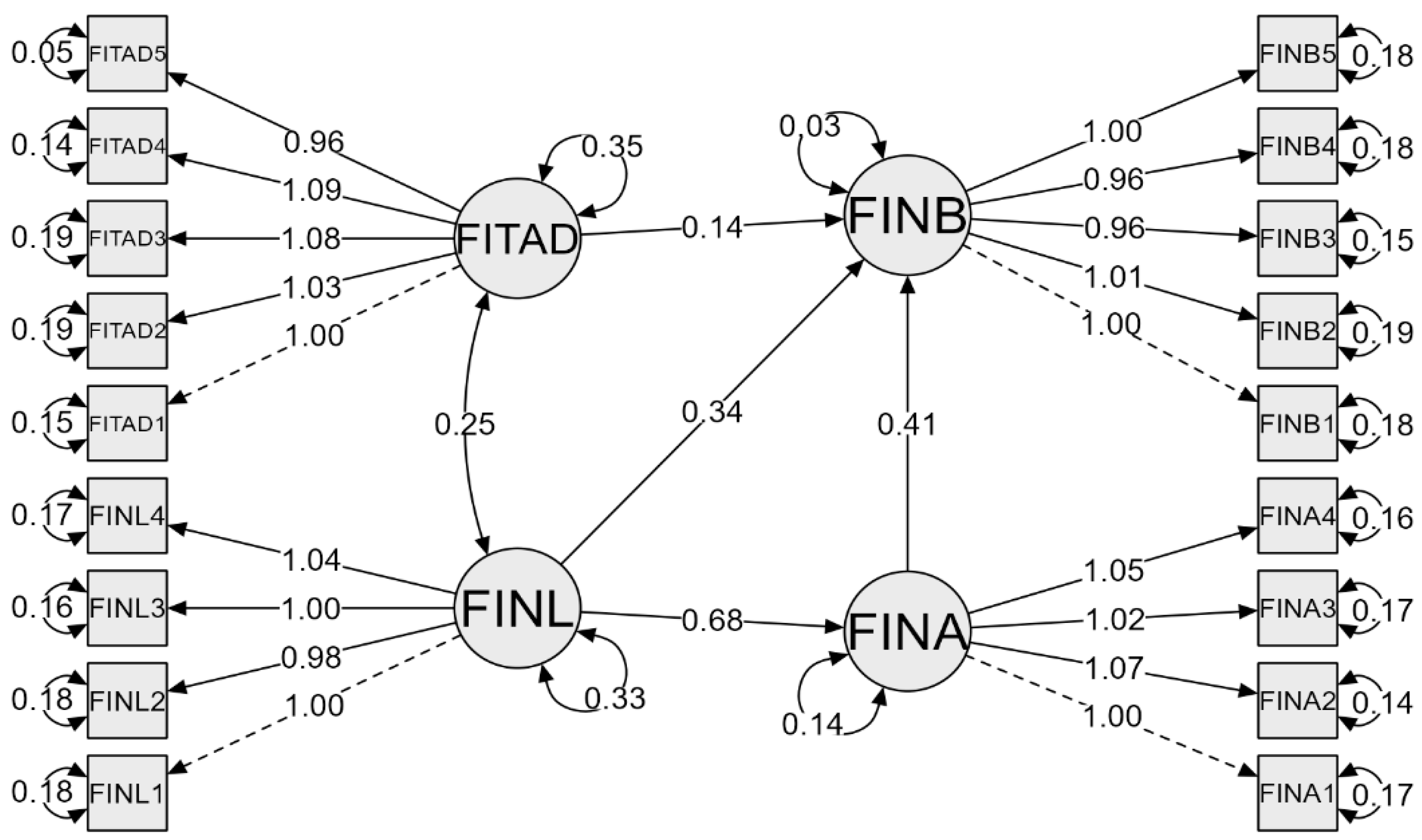

The survey was split into five parts. The first part covers demographic information encompassing background insights related to their age, gender, educational background, employment status, and income. The second part reflects the reported usage and adoption of Fintech (FITAD). The third part is related to the participants’ financial literacy (FINL) measurements. The questionnaire’s fourth part is related to the financial attitude of Lebanese millennials (FINA). Lastly, the fifth part is reserved for respondents’ financial behavioral conduct (FINB), following the behavioral finance theory. Each scale was preferred to provide a robust understanding of the associations between FITAD, FINL, FINA, and FINB in the context of this study.

Therefore, FITAD is examined according to five statements, retrieved from

Ahmad et al. (

2021) observations on the frequency or confidence of using Fintech services, such as online banking, mobile payments, and digital wallets. In turn, FINL items are adapted from

Potrich et al. (

2025), translating the understanding of financial concepts like interest rates and inflation planning for the future with finances, and covering four statements. FINA items are studied based on the study of

Peach et al. (

2017) on attitudes towards money, like money saving, spending, or taking financial risks, comfort with using debt, and encompass four statements. Lastly, FINB items are adapted from

OECD (

2022), which collected participants’ stratified responses about financial behavior, budgeting, saving, repayment of debt, and investing habits.

Before data collection, a pilot test was performed on 20 professionals to secure clarity and reliability. Subsequently, survey participants were provided with substantial information related to this research aim, data utilization, and their rights as research subjects. Respondents then validated their written informed voluntary consent for participating in the questionnaire, and ethical consideration was ensured upon server confidentiality. Also, the names of the survey participants were not supplied to avoid privacy issues. Lastly, ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee (REC) at the Arab Open University (AOU)-Lebanon under the reference AOU-IRB-2025-100.

6.2. Population and Sample

By 2025, the estimate indicates that the population in Lebanon will be 5.81 million, relatively higher than that of 2024 due to stability and prosperity within the country (

Wordometer, 2024). Millennials, born between 1981 and 1996, and aged between 28 and 43, make up around 23.6% of the Lebanese total population (

DataReportal, 2024). This study utilizes random sampling to survey millennials and follows up with snowball sampling. According to Qualtrics, the reliable sample size used for this research is 385 respondents. Hence, online survey data were collected from Lebanese millennials by distributing the questionnaires using Google Forms from March 2025 to May 2025. A final data set of 390 participants was obtained, and the distilled data were then analyzed using JASP statistical software version 0.95.4.0 to test the hypothesized relationships among the variables.

6.3. Data Analysis

In this investigation, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to validate the presumed hypotheses showcased in the conceptual model. SEM was selected because it allows simultaneous estimation of multiple relationships among latent constructs, accounts for measurement error, and is suitable for testing mediating effects. Given the multidimensional nature of behavioral finance constructs, SEM provides stronger explanatory power compared to traditional regression methods. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted before the structural model to confirm that all items loaded significantly onto their respective constructs and that the measurement model met the required validity and reliability thresholds.

Model robustness and validity were assessed following standard SEM procedures. Internal consistency was examined using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, while convergent validity was evaluated through average variance extracted (AVE). Discriminant validity was confirmed using the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio.

Although socio-demographic variables were collected to describe the sample, they were not included in the structural model. The study followed a theoretically driven modeling strategy based on BFT, which focuses primarily on cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral constructs. Including demographics, without theoretical grounds linking them to the endogenous variables, would add unnecessary complexity and reduce model parsimony. For this reason, socio-demographic variables were retained for descriptive purposes only and not incorporated into the final SEM model.

9. Conclusions

This study examined how FinTech adoption, financial literacy, and financial attitudes jointly shape the financial behavior of Lebanese millennials within a prolonged economic and institutional crisis. The findings confirm that financial literacy significantly enhances financial behavior, both directly and indirectly, through a strong mediating effect of financial attitude. FinTech adoption also contributes positively, though with a smaller effect size, reflecting the infrastructural, regulatory, and trust limitations characteristic of Lebanon’s financial environment. While several findings align with global behavioral finance patterns, others are distinctly shaped by Lebanon’s prolonged crisis and institutional breakdown. The analysis, therefore, distinguishes between mechanisms that are generalizable and those that are specific to the Lebanese context. The results demonstrate that in contexts marked by instability, currency devaluation, and weakened banking systems, financial behavior becomes more strongly influenced by psychological evaluations and attitudinal mechanisms than in stable economies. This provides important empirical evidence on how behavioral finance relationships operate differently under crisis conditions.

9.1. Theoretical Implications

In crisis-affected environments, the traditional pathways proposed by BFT undergo significant contextual modification. Crisis-induced uncertainty, survival-driven heuristics, and the erosion of institutional trust reshape the magnitude and direction of established behavioral relationships. Under such conditions, financial attitudes acquire disproportionate influence because individuals rely more heavily on subjective judgments, emotional coping strategies, and heuristic shortcuts when formal financial systems are unstable. These mechanisms help explain why the literacy–attitude–behavior pathway is amplified in Lebanon. Thus, the study extends the BFT by illustrating how macroeconomic stress, institutional breakdown, and high-risk environments distort otherwise stable behavioral mechanisms. In addition, the findings extend BFT by illustrating how cognitive, psychological, and contextual pressures interact in crisis economies, offering a theoretical contribution relevant for research in other fragile markets.

9.2. Implications for Practitioners

This research offers direction for both action and implications for policymakers and educational and financial institutions.

For policymakers, the findings underscore the urgent need to rebuild financial trust through transparent regulation, credible communication, and protection against financial misconduct, elements that strongly shape attitudes in crisis environments. For financial institutions and FinTech providers, the results suggest that digital financial engagement must be supported by intuitive, low-risk tools that address users’ heightened sensitivity to uncertainty. Integrating financial education within mobile apps, reducing friction in onboarding processes, and ensuring clear data protection mechanisms are essential to influencing attitudes positively. For international development organizations, the evidence indicates that financial literacy programming in fragile states must prioritize emotional and attitudinal components, not only technical knowledge, to support households navigating prolonged instability. These insights extend beyond Lebanon and apply broadly to fragile economies experiencing institutional breakdown, inflationary shocks, or trust erosion.

Further, areas of the regulatory framework need to be reinforced to build trust in Fintech platforms, advocating for their adoption, especially in the areas of cybersecurity, data protection, and digital transactions. Financial institutions can also impact the building of positive financial attitudes and behaviors through enhanced affordability and innovation. These institutions are urged to develop programming that is user-friendly and utilizes a Fintech lens, with educational components from budgeting tools with tutorials to personalized financial advice. For engagement to occur, market incentives in the form of reduced transaction fees, loyalty rewards, or benefits that are tiered based on the usage of digital services can lower the barrier to adopting Fintech approaches. In addition, educational institutions are prompted to develop more foundational and applied financial literacy curricula and develop programs centered around important life skills, such as budgeting skills, saving, investing, and borrowing. As a result, the confidence and proficiency of those taught in managing a new world of digital experiences are enhanced.

In turbulent environments and crisis-affected economies, empowering millennials with both tools, Fintech, and mindset (attitudes) is vital to reinforce financial resilience. Community-based peer learning and success stories should be encouraged to normalize responsible financial behavior among young adults.

9.3. Limitations and Future Research

Despite the valuable insights this study delivers, it has a few limitations worth mentioning.

Initially, the study’s sample limits the generalizability of the study, considering that millennials in Lebanon grew up in an exceedingly heterogeneous population. Also, the cross-sectional design limits tracking changes in financial behavior, so further interventions can conduct longitudinal studies that would have significant improvements. The reliance on self-reported surveys also presents a limitation, as self-reports of financial behavior may reflect what participants perceive as their tendencies, yet are not indicators of genuine behavior. Although the study employed a quantitative approach, incorporating qualitative methods such as interviews could yield rich insights that better contextualize user experiences and motivations related to Fintech adoption.

A further limitation concerns the measurement approach used for financial literacy and financial behavior. Both were assessed exclusively through self-reported Likert-scale items, which reflect perceived tendencies and subjective confidence rather than objectively verified financial knowledge or actual behavioral practices. This reliance on perception-based indicators may inflate or distort associations among variables due to self-assessment bias or social desirability effects. Future research should therefore integrate objective measures of financial literacy, such as interest-rate calculations, inflation comprehension, numeracy tasks, and risk-diversification concepts, as well as behavior-based indicators including saving regularity, budgeting habits, payment-method usage, and digital transaction records. Combining subjective and objective measures would substantially strengthen construct validity and provide a more accurate assessment of financial capabilities and real-life financial behavior.

Furthermore, although socio-demographic variables were collected, they were not incorporated into the structural model as control variables. Future studies may examine whether demographic differences moderate the relationships among the constructs.

Additionally, although this study is positioned within Lebanon’s severe economic crisis, it does not incorporate key crisis-specific constructs such as institutional trust, perceived financial risk, inflation exposure, or perceived banking instability. These variables are central to understanding financial behavior in fragile economies, yet they were not included due to the study’s focus on the behavioral pathways proposed by BFT and the lack of validated crisis-specific scales at the time of data collection. Their omission limits the ability to draw direct causal inferences about how macro-level instability shapes micro-level financial decisions. Future research should therefore integrate these constructs to more fully capture the psychological and structural mechanisms operating in crisis environments and to enhance the explanatory power of behavioral models in high-uncertainty settings.

Future research could strengthen and extend these findings through cross-country comparative analyses, particularly by contrasting Lebanon with more financially stable economies (e.g., UAE or Qatar) or with other crisis-affected markets. Such comparisons would clarify whether the behavioral mechanisms identified in this study are context-specific or generalizable. Further studies could also explore generational differences (e.g., Millennials vs. Gen Z).

Taken together, these methodological and conceptual constraints highlight the need to interpret the findings with caution. While the study provides meaningful insights into behavioral mechanisms among millennials in a crisis-affected economy, the scope of the analysis remains limited by the selected constructs, the reliance on self-reported data, and the absence of contextual crisis-related variables. As such, the study offers a focused but not exhaustive account of financial behavior in Lebanon. Future research should adopt more comprehensive designs, integrating objective measures, longitudinal data, and additional crisis-specific constructs, to develop a fuller and more robust understanding of financial decision-making in fragile economic environments.

9.4. Contributions to the Broader Literature

This study advances the literature on financial behavior in emerging markets in four distinct ways, offering primarily methodological and empirical contributions that extend beyond the Lebanese context.

First, it goes beyond typical unidimensional approaches in financial behavior research by demonstrating that cognitive, psychological, and technological factors must be examined jointly rather than in isolation. While existing studies typically focus on financial literacy (cognitive), attitudes (psychological), or FinTech adoption (technological) as standalone predictors, this research provides an integrated framework that captures their simultaneous and interactive effects. This multidimensional perspective offers a more comprehensive and realistic representation of how financial decisions are formed, particularly in contexts where traditional financial guidance systems are absent or inaccessible.

Second, the study contributes methodologically by providing a validated and replicable structural model specifically calibrated for crisis-affected markets. Most behavioral finance models are developed and tested in stable economic environments, limiting their applicability to fragile or volatile contexts. By demonstrating that established measures and relationships remain empirically robust even under severe macroeconomic stress, although with altered magnitudes, this research offers a methodological template that can be adapted and applied to other emerging economies experiencing institutional breakdown, inflationary shocks, or financial system collapse. The structural equation modeling approach used here provides a replicable analytical framework for researchers seeking to investigate financial behavior in similar high-risk environments.

Third, this research addresses a persistent gap in global financial behavior studies, which have historically concentrated on developed economies or stable emerging markets. By supplying large-scale primary data from a severely underrepresented region, the Arab world during an acute crisis, the study expands the empirical foundation upon which global behavioral finance theories are built. This contribution is particularly significant given the near-total absence of nationally representative statistics on FinTech usage, financial literacy levels, or behavioral outcomes in Lebanon and similar MENA countries. The evidence generated here enables more inclusive and geographically diverse meta-analyses and comparative studies, reducing the Western-centric bias that has long characterized the field.

Fourth, the findings hold transferable value for scholars, policymakers, and practitioners working in parallel contexts marked by economic volatility, rapid digital transformation, and generational shifts in financial engagement. The mechanisms identified here, particularly the amplified role of attitudes under uncertainty and the conditional effectiveness of digital financial tools, offer empirical reference points for cross-country comparative research. Countries experiencing hyperinflation, banking sector instability, or erosion of institutional trust, such as Argentina, Venezuela, Zimbabwe, or Sri Lanka, can draw on these findings to inform both academic inquiry and policy design. This cross-contextual applicability positions the study as a useful reference for the growing body of research on financial resilience and digital financial inclusion in fragile states.

Collectively, these contributions move the field forward by integrating dimensions that are often studied separately, by providing methodological scaffolding for crisis-economy research, by filling critical empirical voids in underrepresented regions, and by offering insights that resonate across diverse yet structurally similar economic contexts.