Abstract

The informational efficiency of stock prices is conditioned by the level of quality of financial reports, contributing to an accurate assessment of the company’s future performance. By approaching informational quality from two perspectives, we conducted an analysis of the impact of faithful representation and readability of annual reports on the reaction of the Romanian capital market, measured by annual stock returns (SR) and cumulative abnormal returns (CAR). The findings revealed an accentuated concern of investors regarding the faithful representation of the firm’s financial results (both at the time of financial statements’ publication and at the year-end) and a diminished significance of the comprehensibility level of financial information in the investment decision-making process. The annual reports of a sample of firms listed on the BSE between 2017 and 2023 have an increased level of linguistic complexity, which entails processing costs, and are intended for sophisticated users with financial expertise. Along with the specialized language, the extensive length of reports delays the incorporation of all information into the stock price, decreasing the informational efficiency of the market. This empirical study applies several indices to assess the readability and conciseness of financial information (FOG index, Flesch–Kincaid index, Flesch Reading Ease Score, and report length) and contributes to the expanding literature by providing a useful basis for future analysis of the influence of financial report quality on investors’ perceptions.

1. Introduction

Information is one of the fundamental resources of modern society, significantly influencing how individuals, organizations, and communities interact and make strategic decisions. In the context of investment decisions, financial reports are a starting point in the process of analyzing the results, risks, and prospects that define a company. They become not only a tool for compliance with legislative requirements but also an essential component of the information infrastructure of capital markets, ensuring their efficient functioning by reducing information asymmetry between insiders and the public (Verrecchia, 2001). Within the Romanian capital market, the financial statements are perceived as the main determinant of stock price variation (Spătăcean & Herțeg, 2024), suggesting that investors react predominantly to financial information. Also, they exhibit a fundamentalist and rational approach, independent of market sentiment or overall market trends. In this manner, the relevance of financial reporting in shaping investment decisions becomes increasingly evident, as the quality and clarity of disclosed information exert a measurable influence on the behavior and expectations of capital market participants.

From a three-dimensional perspective, corporate financial reporting can be summarized by the information provided (what), the timing of publication (when), and the manner of presenting financial information (how) (Courtis, 2004); these elements constitute the pillars of quality financial disclosure. As defined by the relevance, accuracy, comprehensibility, and timeliness of published financial information, the quality of financial reporting becomes crucial in informing investment decisions. It ensures the efficient allocation of financial resources by investors and strengthens the stability of capital markets. Issuing financial reports with enhanced informational quality is perceived as cooperative behavior in the capital market (Guiso et al., 2008), as it strengthens investors’ confidence in the published financial information.

However, in an unfavorable scenario, the poor quality of reported financial information, manifested through opacity and accounting manipulation, can have detrimental repercussions on the process of informed investment decisions, such as making inaccurate forecasts (Jin & Myers, 2006) and increased volatility in the capital market (Miller, 2010). Although management’s manipulative interventions on accounting numbers may generate favorable reactions from the market in the short term, in the long term, however, they tend to mislead the valuation of companies by current and potential investors (Anh & Hung, 2025). In this way, earnings management practices affect the relevance and reliability of financial reporting (Burlacu et al., 2024), diminishing their ability to accurately reflect the performance and risks associated with companies and to support investors’ decision-making processes.

The complexity of capital market mechanisms and the diversification of financial products require a more in-depth analysis of how investors base their decisions on investing surplus capital. In this context, a certain level of quality of financial information generates distinct reactions from capital market participants, manifested by fluctuations and sudden adjustments in share prices, not only depending on the informational content of financial reports, but also on the timing of their publication. In this regard, this study aims to conduct an empirical analysis of the link between the quality of financial reporting (from the perspective of two qualitative attributes of financial information: faithful representation and readability) and stock returns (as an indicator of capital market reaction) at the level of Romanian companies listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange. The reference dates for quantifying the Romanian capital market’s reaction include the end of the financial year and the date of publication of the annual financial statements. The results obtained reveal the complexity of the relationship between the quality of financial information and investor reaction, highlighting non-uniform perceptions of the presence of discretionary accruals. Thus, at the moment of financial statement publication, Romanian investors tend to “penalize” the opportunistic behavior of managers (because of the decrease in stock returns). However, at the end of the financial year, they interpret discretionary adjustments as a legitimate strategy for increasing the informativeness of annual reports as stock market returns increase. Furthermore, the high linguistic complexity of annual reports negatively affects annual stock returns, highlighting the importance of clarity and conciseness in financial documents for efficient investor decision-making.

Within the Romanian academic literature, the readability of financial communication in capital markets has received relatively limited attention. Existing studies tend to focus primarily on the quantitative dimensions of financial reporting quality, while placing less emphasis on the comprehensibility of narrative disclosures and their interaction with the accuracy of financial information. By examining both the faithful representation of financial information and its textual intelligibility, and by analyzing their joint impact on investor reactions, this study contributes to a less explored area of the literature and provides new empirical insights from the Romanian capital market, an emerging and relatively under-researched setting.

From a structural point of view, this paper outlines the relevant critical perspectives in the literature on the faithful reflection and comprehensibility of financial information in the capital market, and specifies the research hypotheses and the methodology applied, in accordance with the research objectives. The study also highlights the results obtained and outlines new directions for research, offering empirical perspectives on the sensitivity of the Romanian capital market to the quality of published financial reports.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Financial reporting is a fundamental tool for accurately reflecting a company’s activities, occupying a prominent position in the information infrastructure of modern and efficient economies. With an emphasis on transparency, comparability, and relevance of the information provided, financial reporting serves as a source of information for a wide range of users (internal and external), from employees and various management structures to tax authorities, creditors, and current or potential investors. In the context of capital markets, the improved quality of financial information is associated with a reduction in information asymmetry between insiders and the wider public, contributing to market efficiency and the creation of a favorable investment environment.

The annual reports published by companies incorporate both quantitative information and narrative components (Rahman, 2019), intended to provide a comprehensive picture of the companies’ performance and financial position. However, from the perspective of the impact of financial information quality on the capital market, the literature has focused predominantly on the analysis of numerical sections, namely information on discretionary accruals (Toma et al., 2022; Cerqueira & Pereira, 2017; Soon Kim et al., 2020; Perotti & Windisch, 2017) or financial results (Carp & Toma, 2020; Eliwa et al., 2016). These studies tend to place the textual attributes of financial reports and their impact on various stakeholders in the background.

A firm’s total accruals are considered subjective elements, subject to the professional judgment of managers, and can be divided into non-discretionary accruals and discretionary accruals. Non-discretionary accruals represent the “normal” component of total accruals (Pham et al., 2019), being driven by changes in the company’s economic cycle and recognized in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles. In contrast, discretionary accruals highlight the existence of intentional adjustments to the cash flow by adjusting accounting policies or methods, essentially indicating the quality of the reported financial information (Kliestik et al., 2021).

The literature captures divergent reactions from capital market participants, which can be explained by their different perceptions of the nature of discretionary profit adjustments and earnings management practices. In this regard, Scott (2000) classifies these practices into two categories: opportunistic earnings management and efficient earnings management. Opportunistic management consists of adjusting financial results to satisfy one’s own interests, such as obtaining personal financial benefits or professional ascension. It also involves controlling stock market volatility by creating a fictitious picture of stability and financial health, to the detriment of other categories of stakeholders. On the other hand, effective earnings management contributes to accurately reflecting economic reality by integrating additional private information that would serve the general interests of the firm. Louis and Robinson (2005) adopt the perspective of the efficiency of discretionary accruals, stating that, by using them, managers can reflect favorable private information, which will reduce the informational asymmetry existing in the capital market. In the same spirit, Pham et al. (2019) present empirical evidence on the association of positive discretionary accruals with increased informational value of reported financial results, which are not perceived as a manipulative tool for managing results, but as a mechanism for reducing informational uncertainty. Against this approach, the study by Shette et al. (2016) supports the managerial opportunism hypothesis, showing that before an initial public offering (IPO) on the stock market, companies tend to artificially boost their reported financial performance, causing a temporary rise in stock prices and allowing their shares to be sold at overvalued prices at the time of listing. This reaction of capital market participants is analyzed by L. Li and Hwang (2019), who argue that when managers use discretionary accruals, investors tend to follow trends during periods of rising stock prices, while in the context of falling prices, they exhibit fundamentalist behavior, reacting by rewarding or penalizing discretionary adjustments, respectively. In addition, Fei et al. (2013) emphasize that earnings management practices, which are meant to boost (or lower) companies’ financial performance, have a direct impact on how the capital market perceives them and are associated with an increase in abnormal positive (negative) returns.

On the other hand, the semi-strong form of the efficient market hypothesis (Fama, 1970), according to which stock prices adjust quickly to all disclosed information, is currently conditioned by the way information is presented. A high degree of information complexity reduces its usefulness for users, claiming discrepancies in financial expertise and their ability to process financial data (Gangadharan & Padmakumari, 2023). Thus, the readability of financial information enhances the informative and decision-making value of accounting data, amplifying its usefulness in financial communication, especially in the context of relevant risk assessment and efficient investment decisions.

In a normative approach, the notion of “readability/intelligibility” of financial information is not established terminologically in Romania, being explicitly presented only in OMFP No. 1802/2014 for the approval of Accounting Regulations on individual annual financial statements and consolidated annual financial statements, as one of the amplifying qualitative characteristics of financial information. It is defined by the clarity, conciseness, and comprehensibility with which financial information is presented, organized, and characterized, so that it can be easily understood by various categories of users. Equivalent formulations are found in some legislative or protocol acts relating to the functioning of the capital market, such as the regulations issued by the Financial Supervisory Authority (ASF) or the Corporate Governance Code of the Bucharest Stock Exchange. Internationally, however, ensuring the readability of financial reports has always been a concern for capital market supervisory and regulatory institutions. In this regard, the SEC publishes a guide to writing financial reports (Plain English Handbook, 1998), outlining a series of recommendations on the following: the conciseness of annual reports and the avoidance of ambiguity, the use of common language without highly technical terms (unless they are defined in context), as well as other linguistic suggestions aimed to facilitate the processing and interpretation of financial information by capital market participants.

According to the incomplete disclosure hypothesis (Bloomfield, 2008), the significant costs associated with processing financial information directly affect the degree to which it is incorporated into the market price of shares, reducing stock market informativeness, especially when the disclosed information concerns unfavorable aspects, such as poor financial performance (F. Li, 2008). In addition, the management obfuscation hypothesis argues that company management intentionally resorts to ambiguities, excessive technical language, or complex accounting discourse to conceal sensitive information (poor performance, reputational risks) and manipulate the perception of external users (Loughran & McDonald, 2014; Smaili et al., 2023). Conservative reporting of financial information involves extremely cautious formulation of negative news (De Souza et al., 2019), citing Bloomfield’s (2008) ontological explanation that satisfactory performance is inherently easier to communicate than poor performance.

The interference of psychological and financial theories highlights the cognitive and affective impact of the readability of financial reports on user perception. The degree of readability affects stakeholder confidence and the reliability of disclosed financial information (Rennekamp, 2012), with a positive link identified between readability, market transparency, and informational efficiency (Aldoseri & Melegy, 2023). The comprehensive difficulty of financial information also leads to a negative assessment of companies’ market value (Hwang & Kim, 2017) because of increased uncertainty and risk aversion among investors. Given the existence of information asymmetry, less intelligible reports cause discrepancies between the intrinsic value of companies and their market capitalization, in the sense of overvaluation or undervaluation of shares (Chen et al., 2023). In addition, the complexity and reduced clarity of financial reports cause a decrease in the trading volume of shares (Lawrence, 2013; Boubaker et al., 2019), a phenomenon felt predominantly among individual investors, due to significant processing costs. There are also differences in opinion among investors (D’Augusta et al., 2023), as the ambiguous style of financial reporting leads to different interpretations, manifested by abnormal price volatility in the period following the publication of annual reports. However, the adverse effects of poor readability are mitigated by the expertise of sophisticated users (institutional investors and financial analysts), whose analytical skills and extensive experience help reduce ambiguity regarding investment returns and risks (Asay et al., 2017), as well as to lower the cost of capital (Rjiba et al., 2021).

The level of transparency and clarity of financial reports determines the degree to which company-specific information is absorbed into stock prices. The difficulty in understanding and interpreting the information disclosed by companies leads investors to focus primarily on market or industry factors, to the detriment of analyses based on company-specific information. Consequently, the weight of the information reflected in the share price, as well as the way it is formed, is defined by the synchronicity of stock returns. This quantifies the extent to which the return on an individual stock aligns with market or industry variations, whether it is generated by company-specific information (Dasgupta et al., 2010). The literature highlights a dualism in the impact of financial information readability on stock return synchronicity. Gangadharan and Padmakumari (2023) argue that increased transparency and clarity of financial information lead to increased stock price synchronicity, as investors react similarly to disclosed information, generating simultaneous stock price movements. In contrast, Bai et al. (2018) and Barzegar and Faghih (2023) point out the negative relationship between the comprehensibility of financial reports and price synchronicity, explaining their results by the reduced costs of processing financial information and significant incorporation of firm-specific information into the stock market price. Since annual reports highlight a convergence between financial narratives and accounting numbers, and specialized studies emphasize the connection between manipulative management interventions and their projection in the presentation of financial information (Tiwari et al., 2024; Samit & Prateek, 2023), the objective of this research is to analyze the impact of financial information quality on investor reaction from two distinct perspectives: the faithful representation and readability of financial information. Thus, the main research hypothesis, which refers to the designation of financial information quality as a predictor of investment decisions (H1), is divided into two secondary hypotheses, specific to the two characteristics of financial information quality, as follows:

H1a:

The size of discretionary accruals (DA) significantly influences the annual return and cumulative abnormal returns of stocks at the time of annual report publication.

H1b:

The readability scores (FOG, FKI, FRE) of financial information significantly influence the annual return and cumulative abnormal returns of stocks at the time of publication of annual reports.

3. Methodology and Sample

The sample analyzed consists of 49 companies listed on the main market of the Bucharest Stock Exchange, over a period of seven financial years, namely 2017–2023, summing up to 340 statistical observations. In order to examine the impact of financial information quality on investor perception, we selected models and indices established in the literature, both for assessing the level of faithful representation and readability of financial information, as well as for assessing the reaction of the capital market.

In the context of this study, the annual return on shares reflects investors’ perception of the financial information disclosed by companies. For comparative purposes, an event analysis was also performed on investors’ reaction to the level of information quality at the time of publication of annual reports, considering the cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) of shares one month before and after the publication of financial statements. The event window is set to ±1 month around the publication of financial reports, reflecting the lower liquidity and slower information diffusion of the Romanian capital market. This window allows us to capture both immediate and more gradual price adjustments to financial disclosures, consistent with evidence from emerging and less liquid markets. Obtaining negative or positive values for CAR, calculated according to Equation (1), signals an unfavorable or positive reaction from the market to various predictive factors (Ikram & Nugroho, 2014), considering the deviation of the actual return on shares (R) from the average return of the analyzed sample (). The quantification of the stock market performance of the shares was based on their prices on the Bucharest Stock Exchange from one financial year to another.

where

and

The presence of possible manipulations in the accounting numbers was quantified by applying Jones’ (1991) model, which aims to calculate discretionary accruals as an index of management’s interventions in the reported financial results. The residual component (ε) in Equation (4) captures discretionary accruals as part of total accruals that are not explained by the normal activity of companies and outlines the risk of earnings management practices.

where

- —total accruals of firm i at time t;

- —the operating profit of company i at time t;

- —cash flow from the operating activities of company i at time t;

- —total assets of company i at the end of financial year t − 1;

- —change in the company’s i revenues from one period to another;

- —the gross tangible assets of company i at time t;

- , , —regression model parameters;

- —residual component.

The model parameters are estimated using a pooled approach, whereby all firm-year observations across the entire sample period are jointly used for estimation, and outliers are eliminated following the Tukey (1977) procedure.

Determining the degree of readability of financial information is an interdisciplinary field of information quality, situated at the intersection of accounting, computational linguistics, and communication sciences. The literature reveals a series of relevant indicators for measuring the comprehensibility of financial information, focusing on syntactic analysis of the text (sentence length and word complexity), the proportion of technical terms (Loughran & McDonald, 2014), the tone of accounting discourse (Ayuningtyas & Harymawan, 2021; Rjiba et al., 2021), as well as the size of financial reports (De Souza et al., 2019; Loughran & McDonald, 2014). Regarding the syntactic attributes of textual sections, previous empirical studies predominantly use indices such as the FOG index (F. Li, 2008; Barzegar & Faghih, 2023; Aldahray, 2024; Lo et al., 2017; Ajina et al., 2016; Hesarzadeh & Rajabalizadeh, 2019), the Flesch–Kincaid index (D’Augusta et al., 2023; Gangadharan & Padmakumari, 2023; Tiwari et al., 2024), and the BOG index (Bonsall et al., 2017; Rjiba et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2023). Other studies have developed new composite indices (PC index), which synthesize several methods and metrics for assessing the intelligibility of financial information (Humphery-Jenner et al., 2024), enabling a robust and extensive evaluation.

The widespread recognition of the FOG index in the literature, as well as the possibility of interpreting the results by relating them to the level of formal education required for users to process and understand the information disclosed, indicates the relevance of its application in assessing the comprehensibility of financial reports, calculated according to the following equation:

where the complexity of words refers to their number of syllables (≥3 syllables). The FOG (or Gunning-FOG) index was created by Gunning (1952) and introduced for the first time in accounting literature by F. Li (2008). By assessing the difficulty of understanding the information contained in an annual report at first reading, FOG scores can be interpreted as follows: 8–10 (very simple text, middle school education), 10–12 (accessible text, high school education), 12–14 (ideal text, university education), 14–18 (difficult text, specialized postgraduate education), ≥18 (extremely difficult text, advanced academic or technical education).

To ensure the robustness of the results, the study includes two additional indices for assessing the readability of annual reports, developed by Flesch (1948). Like the FOG index, the Flesch–Kincaid (FKI) and Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) indices, calculated according to Equations (7) and (8), respectively, consider sentence length and the number of syllables per word, emphasizing the comprehensibility of financial reports.

The Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) index generates a numerical score between 0 and 100, where higher values indicate a text that is easy to understand for the public and lower values indicate increased complexity of annual reports and significant difficulties in accessing and interpreting financial information by non-specialist users. In contrast, values between 0 and 18 on the Flesch–Kincaid Index (FKI) outline an estimate of the educational level attributed to users, where low (high) scores denote a high (low) degree of understandability of the narrative discourse, intended for users with financial expertise and an advanced level of education (ordinary users, lacking solid knowledge in the financial field). To highlight the degree of readability of the annual reports, we considered it useful to transpose the scores obtained for the readability indices into categorical variables, according to Table 1.

Table 1.

Codification of readability scores into categorical levels.

Compared to other empirical studies that focus on analyzing the readability of certain sections of annual reports, such as those concerning management analyses and discussions (Samit & Prateek, 2023; Ayuningtyas & Harymawan, 2021), notes to financial statements (Aldahray, 2024), or both (F. Li, 2008), this study looks at annual reports as a whole (Loughran & McDonald, 2014). Based on the premise that each section provides various information relevant to users, we cannot highlight a particular section of the annual reports whose usefulness in the context of investment decisions would be particularly distinctive (Gangadharan & Padmakumari, 2023). In addition, the importance of developing concise and non-redundant narrative content (Alduais et al., 2022), combined with the widespread use of the length of annual reports as an indicator of informational complexity (Lee, 2012; Samit & Prateek, 2023; F. Li, 2008; Ebaid, 2023), determines the inclusion in empirical analyses of the logarithmic number of words in financial reports:

The readability indices of annual reports were computed using computer-assisted textual analysis, following Clarkson et al. (2020). Annual reports were manually downloaded from the official website of the Bucharest Stock Exchange in PDF format and subsequently converted into plain text files to facilitate optical character recognition (OCR) and to enable textual processing. Readability analysis was conducted using RStudio (version 2025.05.1+513), employing the readtext, tidyverse, stringr, and quanteda packages. The RStudio code used to calculate the number of syllables in words was adapted to the linguistic characteristics of the Romanian language, considering vowel sounds combined in a single syllable (diphthong, triphthong). Reports available only in scanned PDF format were excluded due to unreliable text extraction, and observations with missing or implausible readability measures were not included in the empirical analysis.

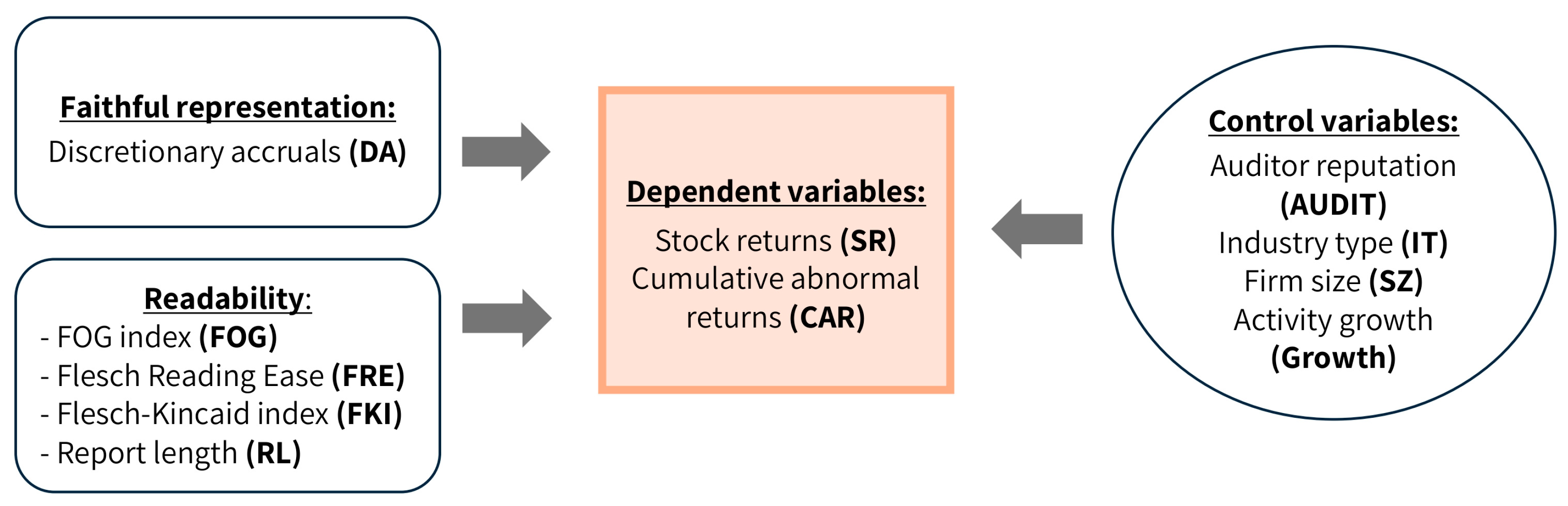

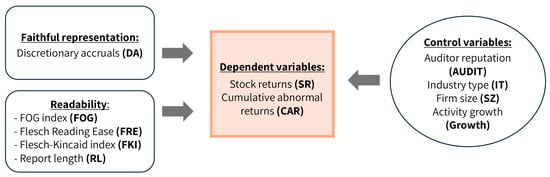

Equations (10) and (11) outline the regression models analyzed, where the parameters are estimated using a pooled approach. Figure 1 provides an overview of the variables included in this empirical study, highlighting the dependent and explanatory variables, as well as the control variables. The latter highlight aspects such as the auditors of the analyzed companies belonging to the Big4 group (AUDIT), the field in which they operate—services, trade, or manufacturing (IT), the size of the company (SZ), determined as the natural logarithm of total assets, and the growth of the companies’ activity (Growth), taking into account the ratio between the variation in turnover from one financial year to another and the turnover for the previous period.

Figure 1.

Methodological framework of the study.

4. Results and Discussion

Considering positive accounting theory, the actions of a company’s management may be influenced by self-interest (wealth accumulation), highlighting opportunistic behavior (Watts & Zimmerman, 1990), especially in the way the performance of listed entities is presented. This involves manipulating earnings through discretionary accruals, either to meet or exceed analysts’ expectations, or to influence stock prices in line with their own interests prior to important corporate events (Jena et al., 2020). In this sense, the faithful representation of the financial reality of companies is affected, emphasizing the information asymmetry between capital market participants, which means that there is an imbalance in the information held by management and investors in terms of both volume and quality (Cerqueira & Pereira, 2017).

From the perspective of the impact of discretionary accruals on investor perception, the results obtained (Table 2) highlight the fact that, at the level of the sample analyzed, a low level of financial information quality (reflected in an increase in discretionary accruals) has the effect of reducing the abnormal return on shares at the time of publication of the financial statements. Consequently, to place capital efficiently, investors are particularly concerned about the accurate representation of companies’ financial results so that opportunistic behavior of the company management, i.e., manipulative interventions in accounting numbers, is ‘penalized’ by a reduction in stock market performance. In this context, investor behavior tends to be fundamentalist (Fama & French, 1992), as capital allocation decisions are based on rigorous analysis of companies’ fundamental value, facilitating the detection of intentional adjustments to reported results. Therefore, the presence of earnings management in financial reporting is a determining factor in the change in cumulative abnormal returns (CAR), especially in the case of institutional investors. Their expertise contributes to the relevant assessment of the earnings reported by companies, which may generate a negative reaction from the stock market (Fei et al., 2013). Similarly, the results are consistent with Sayari et al. (2014), which outlines the negative impact of discretionary accruals on the cumulative abnormal returns of small firms in Tunisia, while highlighting antithetical results in the case of large firms. The same inverse relationship can be observed when analyzing two periods: normal business activity and economic instability, such as the pandemic crisis. The impact of discretionary accruals is more pronounced in the pre-crisis period, highlighting the fact that investor reaction is based on an in-depth analysis of companies’ financial performance and is not influenced by emotional factors, trends, or uncertainty. In terms of control variables, only the growth in companies’ activity reflects a significant influence on cumulative abnormal returns from the moment the financial statements are published.

Table 2.

The impact of discretionary accruals (DA) on stock returns.

Although previous empirical studies emphasize the inverse relationship between discretionary accruals and stock returns, the results obtained indicate an uneven relationship between the two variables. In relation to stock market returns from one financial year to another, an increase in discretionary accruals generates an increase in annual stock returns. This indicates that capital market participants base their investment decisions on information that can be manipulated and do not closely analyze the presence of such interventions. According to L. Li and Hwang (2019), these discrepancies in results may be determined by behavioral heterogeneity among investors, who have different perceptions of the nature of discretionary accruals. In this sense, the presence of discretionary accruals can be perceived as a sign of earnings management—a strategy that enhances the ability of firms to create value for shareholders, generating increased stock market returns. Alternatively, it can suggest earnings manipulation—as a reflection of the financial difficulties encountered by companies, amplifying investors’ risk aversion and, implicitly, diminishing stock market performance. At the same time, in line with the results of Pham et al. (2019), managers manage accruals to reflect relevant private information about the company’s future performance. In that case, this practice is not considered opportunistic behavior, but rather an attempt to minimize information asymmetry between different categories of stakeholders. Thus, for the sample analyzed, investors appear to give limited attention to the quality of financial information. Instead, they interpret discretionary accruals as a sign of a company’s financial potential, which in turn is associated with higher annual returns.

Assuming that, to meet the requirements and expectations of the capital market, managers adopt various strategies to cosmeticize financial reports, in terms of both content and presentation of financial information. Table 3 outlines the degree of readability of the annual reports analyzed using three types of scores.

Table 3.

Readability scores of financial reports.

In terms of the comprehensibility of published annual reports, the categorical variables FOG, Flesch–Kincaid, and Flesch Reading Ease indicate the degree of linguistic complexity of financial reports and are correlated with the minimum level of education required for a user to process and interpret financial information. A maximum score indicates a low degree of accessibility and clarity of financial information (F. Li, 2008), so that, following the content analysis performed in Table 3, most company reports obtained a score of 5 for the FOG and Flesch–Kincaid indices and 7 for the Flesch Reading Ease index. These scores highlight the fact that over 85% of the annual reports analyzed are complex and difficult to read and are written in sophisticated language, with long sentences and technical terms. According to the Institute of Corporate Finance, official reports that are lengthy and highly technical are usually attributed a FOG index of between 30 and 35, highlighting their poor readability and the fact that they are aimed at a limited audience with solid knowledge in the field. In line with the findings of Gangadharan and Padmakumari (2023), Rjiba et al. (2021), and Loughran and McDonald (2014), due to the increased complexity and specialized language, the main audience for these documents is financial professionals (financial analysts) or institutional investors with advanced (academic/professional) education. Consequently, the presentation of information is detrimental to individual investors or users without financial expertise. Furthermore, the low level of readability of annual reports may be the result of deficiencies in management’s communication skills or deliberate attempts to formulate financial information in an ambiguous manner to mask poor financial performance (F. Li, 2008).

Similarly to the analytical approaches conducted by Bai et al. (2018) and Tiwari et al. (2024), this study outlines the differentiated impact of annual report readability on investor behavior, depending on the economic context. Considering the maximum scores obtained for the linguistic complexity of annual reports, the Flesch–Kincaid and Flesch Reading Ease indices highlight the fact that an increase in the level of education of users leads to a better understanding of annual reports, which was more pronounced in the period leading up to the pandemic crisis (Table 4). In this context, investors are more predisposed to analyze the disclosed information in depth, ensuring a relevant assessment of future performance and generating increased annual returns. Therefore, in periods of economic uncertainty or instability, investors rely less on the narrative content of annual reports (Bai et al., 2018), focusing instead on exogenous factors (aggregate market trends or reactions).

Table 4.

Readability metrics and annual return—the role of Flesch indices.

The impact is similar from the perspective of the FOG index, but only in the context of the dissociation between the two periods analyzed (Table 5). In addition, we also considered the level of readability of reports in terms of their length, as the way they are organized also influences the cost of processing and understanding financial information by users. In this sense, the large size of annual reports reduces annual returns, as investors consider more concise reports to be more useful than lengthy ones and contribute to more efficient processing of company-specific information. Similarly, Lawrence (2013) concludes that investors show a preference for shares issued by companies that publish transparent and concise financial reports. The results obtained are consistent with Alduais et al. (2022); thus, the complexity of the narrative sections in annual reports determines the decrease in the current return on shares, as well as the expected future returns. Therefore, the preparation of extensive annual reports can be interpreted as a management strategy to reduce transparency and conceal adverse financial information from investors (F. Li, 2008). Or, given the negative relationship established between report length and annual return depending on the economic context, the longer financial reports outline a detailed reflection of the economic activity of companies, including more information relevant to investors.

Table 5.

The impact of the FOG index and the report length on annual returns.

However, in line with the results of D’Augusta et al. (2023), regarding event analysis, namely the analysis of the impact of readability on abnormal returns at the time of publication of financial statements, it was found that this is not statistically significant. This finding is specific to the sample under investigation and indicates that, within this empirical setting, readability does not constitute a salient factor in investors’ decision-making processes. In this regard, it should be noted that there is a time lag in the incorporation of all the information contained in annual reports into share prices, as this information is more difficult for users to process.

In the Romanian capital market context, the findings regarding readability further demonstrate that low readability and excessive report length impose real information-processing costs, which translate into lower annual stock returns, even if immediate market reactions remain unaffected.

5. Conclusions

The quality of financial information disclosed by listed companies is an essential element in accurately assessing their ability to create added value for investors. The results obtained highlight the complexity of the interaction between the level of information quality in financial reports and investor reaction, outlining multiple implications for investment decisions.

Firstly, the presence of discretionary accruals leads to a decrease in abnormal returns accumulated in the month before and after the publication of financial statements. This suggests that investors tend to penalize managers’ opportunistic behavior and that the faithful representation of companies’ financial performance is a major factor in the decision-making process. However, in the context of financial statement publication, there is a negative relationship between discretionary accruals and cumulative abnormal returns. The analysis of annual returns reveals a positive relationship, shaped by the existence of heterogeneous perceptions among investors, who interpret management adjustments either as a strategy to maximize the value of the firm or as a form of manipulation of financial performance. In this regard, the research presents non-uniform results, highlighting different reactions from the capital market, influenced by contextual factors and the level of investors’ sophistication. At the same time, the temporal analysis carried out over two distinct periods (pre-pandemic and post-pandemic) shows that investors exhibit stronger sensitivity to the quality of financial information in conditions of economic stability, indicating a rigorous basis for investment decisions. However, in times of uncertainty, such as the pandemic crisis, the impact of earnings management on stock market performance is reduced, as exogenous factors have a strong influence on market reaction.

From the perspective of the readability of annual reports, the sample analyzed is characterized by a high degree of linguistic complexity, reflected in maximum scores for the FOG, Flesch–Kincaid, and Flesch Reading Ease indices. These indicate a limited audience, predominantly institutional investors or users with advanced financial training. Sophisticated language and long sentences do not significantly influence the immediate market reaction when annual reports are published. However, they are negatively associated with annual stock returns, highlighting the fact that low readability complicates the analysis of financial information and affects decision-making efficiency. In addition, the length of financial reports negatively influences investor perception, suggesting that concise and well-structured documents are preferred over lengthy ones, which require considerable effort to process. This finding highlights the importance of clarity and relevance of financial information in maintaining investor confidence and maximizing stock market performance.

Given the results obtained from the sample analyzed, the faithful representation of companies’ financial performance prevails over the way they are presented in annual reports. In this sense, numerical information sends more credible signals to capital market participants, so that investors pay particular attention to financial numbers or indicators (Hesarzadeh & Rajabalizadeh, 2019), while the comprehensibility of financial information plays a secondary role, especially in the context of emerging capital markets.

This study is subject to several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, certain methodological choices were adapted to the specific characteristics of the Romanian capital market, which is an emerging and relatively less liquid market. In particular, cumulative abnormal returns were computed using deviations from the average return in order to better capture firm-specific price adjustments, which may limit direct comparability with studies relying on standard market-model specifications. Second, the analysis employs the FOG, Flesch Reading Ease, and Flesch–Kincaid readability indices, which were originally developed for the English language. Although these measures were adapted to the linguistic characteristics of Romanian and applied with the aim of testing their relevance in a different context, their interpretation may not be fully equivalent across languages. Finally, the relatively small sample size restricts the generalizability of the findings, and the results should therefore be interpreted with caution when extending conclusions to other emerging capital markets. Overall, the findings have important implications for regulators and investors. For regulators, they highlight the need to strengthen disclosure standards that enhance transparency and comparability, particularly in emerging markets where information asymmetry is more pronounced. For investors, the results underscore the importance of focusing on the substance of financial performance while exercising caution with managerial discretion and complex disclosures that may obscure underlying fundamentals.

In future research, in addition to conducting a syntactic analysis of annual reports, it would be useful to determine the implications of negative or ambiguous tone and the presence of persuasive language in the narrative sections. This study contributes to the expanding literature on the subject and will be useful in future analysis of the influence of financial report quality on investor perception.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M. and M.C.; methodology, D.M.; validation, M.C.; formal analysis, D.M. and M.C.; investigation, D.M.; data curation, D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.; writing—review and editing, D.M. and M.C.; visualization, D.M. and M.C.; supervision, M.C.; project administration, D.M. and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were manually collected from the website of the Bucharest Stock Exchange at www.bvb.ro (accessed on 18 February 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ajina, A., Laouiti, M., & Msolli, B. (2016). Guiding through the fog: Does annual report readability reveal earnings management? Research in International Business and Finance, 38, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldahray, A. (2024). Notes readability and discretionary accruals. Spanish Accounting Review, 27(2), 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoseri, M. M., & Melegy, M. M. (2023). Readability of annual financial reports, information efficiency, and stock liquidity: Practical guides from the Saudi business environment. Information Sciences Letters, 12(2), 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alduais, F., Ali Almasria, N., Samara, A., & Masadeh, A. (2022). Conciseness, financial disclosure, and market reaction: A textual analysis of annual reports in listed Chinese companies. International Journal of Financial Studies, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, P. T., & Hung, D. N. (2025). The impact of earnings management on stock returns with the moderating role of audit quality in emerging markets. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 15(6), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asay, H. S., Elliott, B. W., & Rennekamp, K. (2017). Disclosure readability and the sensitivity of investors’ valuation judgments to outside information. The Accounting Review, 92(4), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuningtyas, E. S., & Harymawan, I. (2021). Negative tone and readability in management discussion and analysis reports: Impact on the cost of Debt. Journal of Theory and Applied Management, 14(2), 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X., Dong, Y., & Hu, N. (2018). Financial report readability and stock return synchronicity. Applied Economics, Taylor & Francis Journals, 51(4), 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, G., & Faghih, M. (2023). Financial report readability and stock price synchronicity: The moderator role of CEO media exposure. Empirical Studies in Financial Accounting, 20(78), 117–153. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield, R. (2008). Discussion of „Annual report readability, current earnings, and earnings persistence”. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(2–3), 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsall, S. B., Leone, A. J., Miller, B. P., & Rennekamp, K. M. (2017). A plain English measure of financial reporting readability. Journal of Accounting & Economics (JAE), 63(2), 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubaker, S., Gounopoulos, D., & Rjiba, H. (2019). Annual report readability and stock liquidity. Financial Markets, Institutions and Instruments, 28(2), 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlacu, G., Robu, I.-B., & Munteanu, I. (2024). Exploring the influence of earnings management on the value relevance of financial statements: Evidence from the bucharest stock exchange. International Journal of Financial Studies, 12(3), 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carp, M., & Toma, C. (2020). Earnings quality and market efficiency: Evidence from Romanian capital market. In Eurasian studies in business and economics (pp. 193–210). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, A., & Pereira, C. (2017). Accruals quality, managers’ incentives and stock market reaction: Evidence from Europe. Applied Economics, 49(16), 1606–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Hanlon, D., Khedmati, M., & Wake, J. (2023). Annual report readability and equity mispricing. Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics, 19(3), 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P. M., Ponn, J., Richardson, G. D., Rudzicz, F., Tsang, A., & Wang, J. (2020). A textual analysis of US corporate social responsibility reports. Abacus, 56(1), 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtis, J. K. (2004). Corporate report obfuscation: Artefact or phenomenon? The British Accounting Review, 36(3), 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S., Gan, J., & Gao, N. (2010). Transparency, price informativeness, and stock return synchronicity: Theory and evidence. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 45(5), 1189–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Augusta, C., Vito, A., & Grossetti, F. (2023). Words and numbers: A disagreement story from post-earnings announcement return and volume patterns. Finance Research Letters, 54(2), 103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, J. A., Rissatti, J. C., Rover, S., & Borba, J. A. (2019). The linguistic complexities of narrative accounting disclosure on financial statements: An analysis based on readability characteristics. Research in International Business and Finance, 48, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebaid, I. E. (2023). IFRS adoption and the readability of corporate annual reports: Evidence from an emerging market. Future Business Journal, 9(1), 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliwa, Y., Haslam, J., & Abraham, S. (2016). The association between earnings quality and the cost of equity capital: Evidence from the UK. International Review of Financial Analysis, 48, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F. (1970). Efficient capital markets: A review of theory and empirical work. The Journal of Finance, 25(2), 383–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1992). The cross-section of expected stock returns. The Journal of Finance, 47(2), 427–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, D. F., Su, L., & Ning, H. N. (2013, January 16–17). Institutional investors holdings on earnings management market reaction intensity affect study. Fifth International Conference on Measuring Technology and Mechatronics Automation (pp. 639–642), Hong Kong, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flesch, R. (1948). A new readability yardstick. Journal of Applied Psychology, 32(3), 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangadharan, V., & Padmakumari, L. (2023). Annual report readability and stock return synchronicity: Evidence from India. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1), 2186034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2008). Trusting the stock market. Journal of Finance, 63(6), 2557–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning, R. (1952). The technique of clear writing. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hesarzadeh, R., & Rajabalizadeh, J. (2019). The impact of corporate reporting readability on informational efficiency. Asian Review of Accounting, 27(4), 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphery-Jenner, M., Liu, Y., Nanda, V., Silveri, S., & Sun, M. (2024). Of fogs and bogs: Does litigation risk make financial reports less readable? Journal of Banking & Finance, 163, 107180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B., & Kim, H. (2017). It pays to write well. Journal of Financial Economics, 124(2), 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, F., & Nugroho, A. B. (2014). Cumulative average abnormal return and semistrong form efficiency testing in Indonesian equity market over restructuring issue. International Journal of Management and Sustainability, Conscientia Beam, 3(9), 552–566. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, S. K., Mishra, C. S., & Rajib, P. (2020). Do Indian companies manage earnings before share repurchase? Global Business Review, 21(6), 1427–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L., & Myers, S. C. (2006). R2 around the world: New theory and new tests. Journal of Financial Economics, 79(2), 257–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J. J. (1991). Earnings management during import relief investigation. Journal of Accounting Research, 29(2), 193–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliestik, T., Belas, J., Valaskova, K., Nica, E., & Durana, P. (2021). Earnings management in V4 countries: The evidence of earnings smoothing and inflating. Economic Research, 34(1), 1452–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A. (2013). Individual investors and financial disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 56, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. J. (2012). The effect of quarterly report readability on information efficiency of stock prices. Contemporary Accounting Research, 29(4), 1137–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. (2008). Annual report readability, current earnings, and earnings persistence. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(2–3), 221–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., & Hwang, N.-C. R. (2019). Do market participants value earnings management? An analysis using the quantile regression method. Managerial Finance, 45(1), 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K., Ramos, F., & Rogo, R. (2017). Earnings management and annual report readability. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 63(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, T., & McDonald, B. (2014). Measuring readability in financial disclosures. The Journal of Finance, 69, 1643–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, H., & Robinson, D. (2005). Do managers credibly use accruals to signal private information? Evidence from the pricing of discretionary accruals around stock splits. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(2), 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B. P. (2010). The effects of reporting complexity on small and large investor trading. The Accounting Review, 85(6), 2107–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perotti, P., & Windisch, D. (2017). Managerial discretion in accruals and informational efficiency. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 44, 375–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H. Y., Chung, R. Y.-M., Roca, E., & Bao, B.-H. (2019). Discretionary accruals: Signalling or earnings management in Australia? Accounting and Finance, 59(2), 1383–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S. (2019). Discretionary tone, annual earnings and market returns: Evidence from UK interim management statements. Review of Financial Analysis, 65, 101384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennekamp, K. (2012). Processing fluency and investors’ reactions to disclosure readability. Journal of Accounting Research, 50(5), 1319–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjiba, H., Saadi, S., Boubaker, S., & Ding, X. (2021). Annual report readability and the cost of equity capital. Journal of Corporate Finance, 67, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samit, P., & Prateek, S. (2023). Does earnings management affect linguistic features of MD&A disclosures? Finance Research Letters, 51, 103352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayari, S., Omri, A., Finet, A., & Harrathi, H. (2014). The impact of earnings management on stock returns: The case of Tunisian firms. Global Journal of Accounting, Economics and Finance, 1(1), 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, R. W. (2000). Financial accounting theory. Prentice Hall Canada Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Shette, R., Kuntluru, S., & Korivi, S. R. (2016). Opportunistic earnings management during initial public offerings: Evidence from India. Review of Accounting and Finance, 15(3), 352–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaili, N., Gosselin, A. M., & Le Maux, J. (2023). Corporate financial disclosures and the importance of readability. Journal of Business Strategy, 44(2), 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon Kim, K., Young Chung, C., Hwon Lee, J., & Cho, S. (2020). Accruals quality, information risk, and institutional investors’ trading behavior: Evidence from the Korean stock market. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 51, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spătăcean, I. O., & Herțeg, M. C. (2024). Investors’ reaction to financial reporting—Empirical studies on price volatility on the bucharest stock exchange. Acta Marisiensis, Seria Oeconomica, 17(1), 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S., Chatterjee, C., & Sengupta, P. (2024). Effect of earnings management and cash holdings on annual report readability: Evidence from top Indian companies. IIMB Management Review, 36(4), 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, C., Carp, M., Afrăsinei, M. B., & Georgescu, I. E. (2022). Value relevance of accruals. The case of listed Romanian companies. Transformations in Business and Economics, 21(2A), 496–513. [Google Scholar]

- Tukey, J. W. (1977). Exploratory data analysis (Vol. 2). Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Verrecchia, R. E. (2001). Essays on disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32(1–3), 97–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R., & Zimmerman, J. (1990). Positive accounting theory: A ten year perspective. The Accounting Review, 65(1), 131–156. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.