Abstract

This systematic review explores the incorporation of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors within financial risk prediction models, with a particular focus on Machine Learning (ML), Natural Language Processing (NLP), and Large Language Models (LLM). Adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and the Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and PICOC frameworks, we identified 74 peer-reviewed publications disseminated between 2009 and March 2025 from the Scopus database. After excluding 10 systematic and literature reviews to avoid double-counting of evidence, we conducted quantitative analysis on 64 empirical studies. The findings indicate that traditional econometric methodologies continue to prevail (48%), followed by ML strategies (39%), NLP methodologies (8%), and Other (5%). Research that concurrently focuses on all three dimensions of ESG constitutes the most substantial category (44%), whereas the Social dimension, in isolation, receives minimal focus (5%). A geographic analysis reveals a concentration of research activity in China (13 studies), Italy (10), and the United States and India (6 each). Chi-square tests reveal no statistically significant relationship between the methodological approaches employed and the ESG dimensions examined (p = 0.62). The principal findings indicate that ML models—particularly ensemble methodologies and neural networks—exhibit enhanced predictive accuracy in the context of credit risk and default probability, whereas NLP methodologies reveal significant potential for the analysis of unstructured ESG disclosures. The review highlighted ongoing challenges, including inconsistencies in ESG data, variability in ratings across different providers, insufficient coverage of emerging markets, and the disparity between academic research and practical application in model implementation.

1. Introduction

The crisis caused by climate change in recent years has emphasized the need to consider Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria in business investment. Although the ESG concept was introduced decades ago in the United Nations’ Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) (UNEP FI & UN Global Compact, 2006), it has gained momentum due to the growing importance of corporate sustainability performance alongside financial performance, enabling Socially Responsible Investments (SRIs). Increasing regulations and investor expectations regarding corporate sustainability require integrating these factors into financial risk management.

Environmental factors include mitigation of climate change, resource efficiency, pollution prevention, and protection of biodiversity. Social factors include treatment of workers, respect for human rights, community engagement, and product safety. Governance factors include corporate governance matters such as board structure and executive pay (United Nations Global Compact, 2004).

The European Union (EU) has been the world leader in ESG financial rules. A key milestone was the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (Directive 2014/95/EU), which required large companies to disclose social and environmental information (European Parliament and Council, 2014). In 2021, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) came into effect, requiring financial market participants to explain how they integrate sustainability risks (European Parliament and Council, 2019). The EU also introduced the Taxonomy Regulation in 2020 to define sustainable economic activities (European Parliament and Council, 2020). The adoption of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) in 2022 further expanded the scope and rigor of ESG reporting, enforcing alignment with the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (European Parliament and Council, 2022). These efforts show that the EU is incorporating ESG as a part of both financial risk regulation and disclosure.

In contrast to this comprehensive regulatory approach, the U.S. adopted a more fragmented strategy. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) gave advice in 2010 suggesting that companies should disclose climate risks under existing materiality (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 2010). In 2022, the SEC proposed comprehensive climate risk disclosure rules aligned with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFDs) (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 2022). At the same time, investor-led groups like the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) developed ESG metrics that are specific to each industry (Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, 2020). These developments reflect a growing recognition of the materiality of ESG factors in investor risk assessment, despite a less prescriptive regulatory environment compared to the EU.

In contrast to the market-driven evolution observed in the United States, China has rapidly advanced ESG integration through top-down regulatory mandates. In 2008, stock exchanges started making voluntary disclosures. By 2016, these disclosures had turned into national green finance guidelines (People’s Bank of China, 2016). By 2021, the China Securities Regulatory Commission required listed firms to disclose ESG-related risks in periodic reports (China Securities Regulatory Commission, 2021). In 2024, the Ministry of Finance introduced draft Corporate Sustainability Disclosure Standards to align with global norms (Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China, 2024). Other regional hubs, such as Hong Kong and Singapore, have also made rules about ESG reporting, which are often based on the TCFD framework.

All these government initiatives have fostered researchers to propose advanced models to analyze and predict the impact of ESG factors on financial risks. Existing studies reveal that although traditional econometric methodologies continue to prevail, the use of Machine Learning (ML), Natural Language Processing (NLP), and Large Language Models (LLMs) are demonstrating their suitability for capturing nonlinear relationships and processing unstructured ESG data that conventional approaches cannot handle effectively.

In this context, the contribution of this survey is threefold: (i) we identify existing solutions related to the application of data-driven techniques—including ML, NLP, and LLM—for ESG-based financial risk prediction, following the PRISMA and PICOC frameworks to ensure methodological rigor; (ii) we propose a taxonomy to classify the studies in terms of methodological approaches, ESG dimensions, geographic scope, and data sources, and perform a comparative analysis according to these criteria; and (iii) we highlight the lessons learned from existing approaches, identify critical research gaps, and outline future directions to guide the development of more robust ESG risk assessment frameworks.

2. Related Systematic Literature Reviews

To cover various aspects of ESG factors from multiple perspectives—such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) applications in finance, corporate sustainability performance, and climate-related financial risks—several authors have conducted systematic literature reviews. This section presents a comprehensive analysis of ten reviews identified during our search process, which provide valuable insights into the current state of knowledge and methodological approaches in the field.

Following the PICOC and PRISMA methodology described in Section 3, these ten reviews were identified and selected. By presenting them separately, we provide context on the current state of knowledge while avoiding the methodological issue of double-counting evidence from secondary analyses in our quantitative synthesis.

Lim (2024) conducted a systematic literature mapping study at the intersection of ESG, AI and finance. The study analyzed 370 papers to identify knowledge gaps and research trends, identifying eight archetypical research domains including Trading and Investment, ESG Disclosure, Data, and Responsible Use of AI. The mapping revealed that the Trading and Investment domain shows the highest research intensity but is becoming crowded, while the Data archetype demonstrates significant growth potential. The study employed bibliometric analysis combined with network analyses and topic modeling, utilizing tools such as EndNote X9, NVivo11, and Excel spreadsheets for data organization. Key findings emphasized that the integration of ESG and AI in finance offers new opportunities for sustainable investment practices, with ML algorithms demonstrating capability in analyzing ESG data to inform investment decisions. The research highlighted regulatory frameworks’ significant impact on ESG and AI adoption in finance and called for future research to explore emerging AI techniques for ESG applications.

Redondo and Aracil (2024) conducted a systematic review, adhering to PRISMA best practices, to evaluate the incorporation of climate-related credit risk (CRR) into the credit risk assessment and management frameworks of banks. They analyzed 145 research papers that were written by policymakers and financial regulators and used quantitative methods and content analysis to do so. The synthesis process produced four themes: CRR drivers, CRR tools, CRR data, and CRR pricing. This study concludes that the process of climate-related credit risk evaluation differs markedly from the latter, influenced by factors such as uncertainty, non-linearity, heterogeneity across geographical and sectoral dimensions, and the irreversible characteristics of the CRR factors. The study also highlights concerns regarding CRR data, especially their comparability, availability, and reliability. It suggests that using AI tools could help with these issues. There is a discussion about a general framework for integrating CRR into the management process of credit risk and how policy contexts and risk appetite are important for managing CRR.

Kaleem et al. (2024) conducted a review of ML techniques for predicting business failure in the Brazilian context, with particular focus on ESG factor integration. The study analyzed data from 235 companies using principal component analysis on 40 variables related to bankruptcy prediction, ultimately identifying seven key predictive variables. An elaborate suite of 11 major ML algorithms was employed, including Decision Tree, Random Forest, Ada Boost, Gradient Boosting, Support Vector Machine, Naive Bayes, and Logistic Regression. The findings demonstrated that ESG factors significantly predict business failure in Brazil, with the incorporation of ESG scores enhancing bankruptcy prediction model precision. The research revealed that Decision Tree, Random Forest, Ada Boost, and Gradient Boosting models performed excellently, while ESG variables affected different algorithms to varying degrees. The study contributes valuable insights for investors, policymakers, and business leaders regarding risk assessment and strategic decision-making in developing economies.

In 2025, a PRISMA-based systematic review was conducted by Ed-Dafali et al. (2025) regarding ESG practices and their overall impact on sustainability and financial performance. In total, 85 articles published in high-quality refereed journals, and recorded in Scopus, were carefully considered. The results show that having effective governance factors, such as various levels of presence and integration of the ESG approach, as well as efficient risk management, are the most important drivers of improved ESG performance and financial profitability. At the same time, some gaps are currently observed in the knowledge base, especially regarding new, up-and-coming issues such as green innovation, ESG controversy, and the impact of digitalization. The geographic distribution of the research covers developed nations (61%) and developing nations (34%, including 25% transcending national boundaries).

Similarly, de Souza Barbosa et al. (2023) utilized the same systematic literature review method following the PRISMA protocol to map and examine the literature concerning the influence of ESG factors on corporate sustainability performance from diversified perspectives. This study involved the critical and extensive examination of selected articles and the utilization of network analysis software, to examine the precise conformity of keywords. Ultimately, the study produced a compilation of 49 research articles that were gathered using systematic literature reviews, adding two research articles using the snowball technique. Some major findings point towards the fact that the consideration and integration of ESG factors improve corporate sustainability performance.

dos Reis Cardillo and Cruz Basso (2025) investigated the variables that influence the relationship between ESG-factors and corporate financial performance (CFP) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) factors. In the study, the authors focused on 108 articles listed on the Web of Science and Scopus databases, published between 2019 and 2023. The authors were able to identify the major variables, important studies, and approaches to the study. The paper highlights that the inconsistent orientation of the moderating variables like governance, culture, and technological and market maturity significantly impacts the relationship between financial performance and ESG and CFP. The study indicates that the literature appears inconsistent due to various study approaches and the definitions applied to the study. Indeed, these variables remain understudied. The study calls for standardization of the definition of the variables and the use of advanced study approaches to improve the relationship between corporate sustainability and financial performance.

Fiaschi et al. (2020) offered a critical review of ESG metrics, evaluating existing indices and their limitations in measuring corporate wrongdoing. The study proposed an M-quantile regression approach to develop an index of corporate wrongdoing, understood as firms’ involvement in controversies over universal human rights. The methodology was applied to a novel hand-collected dataset of 380 large publicly listed firms from both advanced and emerging economies, covering the period 2003–2012. The dataset included 1078 controversies across 102 countries and 3473 firm-year events. The research highlighted that existing ESG data, while widely used in academia, present significant limitations that require assessment and resolution. The proposed methodology provides a direct measure of reliability through confidence intervals and allows for flexible operationalizations of indices based on the severity of human rights abuses. The study emphasized the importance of shifting corporate focus from “doing good” to “doing no harm,” arguing that existing metrics may overlook harmful corporate practices despite positive CSR initiatives.

Mashaqi et al. (2025) carried out the synthesis of the literature to examine the non-linear relationship between environmental quality and risk-taking activities of banks for the Middle East and North African (MENA) region. In the study, the research applied generalized quadratic quantile regressions and the data involved 154 publicly listed banks from the MENA region during 2011 and 2023. The findings revealed a U-shaped relationship between bank risk-taking and environmental quality, indicating that initial improvements in environmental quality reduce risk-taking until a threshold is reached. Larger banks demonstrated better management of environmental hazards without increasing risk-taking behavior, highlighting the moderating influence of bank size. The research challenged conventional linear models and advocated for the Resource-Based View in understanding risk management. Practical implications emphasized the need for effective risk management strategies that consider both bank size and environmental improvements, with particular attention to smaller banks facing increased risk due to limited resources.

Aversa (2024) performed a literature review of banks’ sustainability report disclosures in relation to climate change and financial stability. The study examined the sustainability reports of banks on the FTSE Italia All-Share index for 2020–2021, employing multivariate techniques such as Reinert’s method for hierarchical descendant analysis and cluster analysis. The study utilized text analytics that integrated unsupervised learning with information extraction and retrieval methodologies, employing tools such as Iramuteq 0.7 alpha 2. The findings revealed significant deficiencies in the quality and comprehensiveness of sustainability reports. Banks provided limited disclosure on climate change, prioritizing broader environmental, social, and governance reporting instead. The study emphasized the need for enhanced transparency and alignment with international standards in banks’ scenario analysis and disclosure of transition and physical risks.

Magli and Amaduzzi (2025) wrote a literature review that examined the best practices for innovation in annual reports. It focused on how corporate reporting has changed over time and how technology can enhance transparency. The review showed that technology and changes in the law have driven substantial advancements in financial reporting, including the adoption of AI-based analytics and blockchain-enabled verification systems. The European Commission’s efforts, such as the 2001 Green Paper on CSR and the 2014 Directive on non-financial disclosures, were examined. The study focused on the CSRD, which mandates comprehensive sustainability disclosures starting with the 2024 financial year. It also addressed the Triple Bottom Line approach, which encourages businesses to look at their performance in terms of economic, social, and environmental factors.

2.1. Summary of Methodological Approaches

The identified reviews demonstrate diverse methodological approaches. Systematic literature reviews following PRISMA guidelines were employed by Redondo and Aracil (2024), Ed-Dafali et al. (2025), and de Souza Barbosa et al. (2023). Bibliometric analysis was utilized by Lim (2024) and dos Reis Cardillo and Cruz Basso (2025). ML approaches for data analysis were featured in Kaleem et al. (2024) and Aversa (2024). Quantitative econometric methods including quantile regression were employed by Mashaqi et al. (2025) and Fiaschi et al. (2020). The variety of methodological approaches reflects the interdisciplinary nature of ESG research spanning finance, management, environmental sciences, and data science.

Despite the diversity of methodological approaches, these reviews coincide with the following points of discussion. First, there is a consistent tension between predictive accuracy and interpretability: ML-based approaches demonstrate superior forecasting performance, yet their adoption in practice remains limited by explainability concerns (Kaleem et al., 2024; Lim, 2024). Second, data quality and standardization emerge as persistent obstacles across all reviews, with ESG rating divergence undermining cross-study comparability (Fiaschi et al., 2020; Redondo & Aracil, 2024). Third, the relationship between ESG and financial outcomes appears highly context-dependent, varying by region, industry, firm size, and regulatory regime (dos Reis Cardillo & Cruz Basso, 2025; Ed-Dafali et al., 2025). These issues help identify our research questions, and they will be further explored within the Section 5, where inconsistencies among the 64 primary studies considered will be explored.

2.2. Research Gaps Identified

Across the reviewed literature, several consistent research gaps emerged. First, there is a need for standardized ESG metrics and variables to enable meaningful cross-study comparisons (Berg et al., 2022; Billio et al., 2021). Second, the integration of emerging technologies such as AI and ML with ESG analysis requires further exploration (Lim, 2024). Third, research on ESG impacts from stakeholder perspectives beyond shareholders, particularly workers and communities, remains limited (de Souza Barbosa et al., 2023). Fourth, the relationship between ESG factors and financial performance continues to show inconsistent findings due to methodological heterogeneity (dos Reis Cardillo & Cruz Basso, 2025; Friede et al., 2015). Fifth, climate-related financial risk assessment tools and data reliability require significant development (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2021; Financial Stability Board, 2021). These gaps provide direction for future research endeavors in the field.

This systematic review addresses the second research gap, where emerging technologies in ESG metrics are underutilized. This gap is very important for three reasons. First, ESG data increasingly originates from unstructured sources—sustainability reports, news media, social platforms—that traditional econometric methods cannot effectively process. Second, the nonlinear relationships between ESG factors and financial outcomes require algorithms capable of capturing complex interdependencies. Third, regulatory pressure for real-time ESG risk monitoring (e.g., SFDR, CSRD) demands computational approaches that can process information faster than annual rating cycles allow. By examining how ML and NLP are currently deployed in this domain, this review identifies both achievements and opportunities for methodological advancement. This research seeks to examine how ESG factors are incorporated into financial risk prediction models, especially concerning ML and NLP tools. This systematic review identifies the trends, problems, and opportunities for further research concerning the use of ML and NLP for financial risk prediction based on ESG considerations.

2.3. Theoretical Foundations: ESG Mechanisms and Financial Risk

To better understand the connection between the effect resulting from the incorporation of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors and financial risk, it is necessary to have an understanding of recognized theories. There are certain theories that help to clarify the impact of different ESG factors in managing financial performance.

Stakeholder Theory (Freeman, 1984) argues that companies that manage relationships with stakeholders beyond shareholders achieve better long-term performance because they are less exposed to operational disruptions, reputational damage, and regulatory penalties. From this view, strong ESG performance can be seen as a sign of effective stakeholder management, which helps reduce risk.

Information Asymmetry Theory (Akerlof, 1970) provides another explanatory mechanism. ESG disclosure reduces information asymmetry between firms and investors by revealing non-financial risks that traditional accounting metrics fail to capture. Enhanced transparency through ESG reporting allows investors and creditors to more accurately assess default probability and required risk premiums, thereby affecting cost of capital and credit ratings.

Risk Management Theory frames ESG performance as a proxy for overall management quality and organizational resilience (Godfrey, 2005). Firms with robust environmental management systems, strong labor relations, and effective governance structures demonstrate superior risk identification and mitigation capabilities. These competencies translate into lower operational risk, reduced litigation exposure, and greater adaptability to regulatory changes.

Legitimacy Theory (Suchman, 1995) suggests that firms must operate within the bounds of societal expectations to maintain their “license to operate.” ESG practices enhance organizational legitimacy, reducing the risk of consumer boycotts, regulatory sanctions, and activist campaigns that could impair financial performance.

These theories also help explain why ML and NLP are useful for ESG risk assessment. ML models can handle non-linear relationships. For example, the impact of a firm’s environmental record on credit risk is not the same across industries, and it also depends on how much the firm emits. NLP helps address two problems from the theories above: companies are not always clear in what they disclose (disclosure opacity), and outsiders usually know less than management (information asymmetry). Much of what we know about ESG comes from text—sustainability reports, news articles, and regulatory filings—and structured ratings may miss this or reflect it too late. NLP can detect early signs of ESG problems before they show up in the numbers, which goes beyond just improving predictions.

3. Methodology of the Systematic Review: Search, Screening, and Analysis

This systematic review uses the PICOC model to ensure that the process and procedure followed are robust, clear, and well-articulated, and that it also satisfies the PRISMA checklist.

3.1. PICOC Framework

The PICOC framework—standing for Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, and Context—offers a systematic and transparent approach for formulating research questions and structuring the scope of systematic reviews (Kitchenham & Charters, 2007).

Applying the PICOC framework in this review helps to clarify the inclusion criteria, guide the search strategy, and ensure methodological coherence. The main elements as applied to our study are as follows:

- Population (P): The population of interest includes firms, industries, and financial markets where ESG criteria are actively considered. This encompasses organizations across a broad spectrum of sectors and jurisdictions, with varying degrees of ESG integration. The review emphasizes firms that disclose ESG information and investors or analysts who incorporate ESG signals into financial decision-making.

- Intervention (I): The primary intervention examined is the integration of ESG factors into financial risk assessment processes through advanced data-driven techniques. Specifically, the review focuses on the use of ML and AI models—particularly NLP and LLM—to extract, interpret, and apply ESG-related data from structured and unstructured sources. These include financial disclosures, ESG rating agencies, media sentiment, and social networks.

- Comparison (C): This component involves contrasting different approaches to ESG integration and their influence on financial risk modeling. Comparators include firms that do not employ ESG criteria, variations in ESG scoring methodologies—such as MSCI1 versus Sustainalytics2 —and different ML/AI architectures. The review also explores the comparative performance of models using internally generated ESG data versus external sources, as well as traditional statistical techniques versus modern AI-driven models.

- Outcomes (O): The expected outcomes center on financial risk indicators (e.g., credit risk, volatility), predictive performance metrics (e.g., precision, recall, Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), etc.), and broader measures of financial stability. Additional outcomes include identifying the ESG dimensions most correlated with financial resilience and evaluating the interpretability and reliability of ML-generated predictions.

- Context (C): The contextual scope covers an extensive range of geographical and industry sectors. In light of the global nature of ESG integration, the literature review features research conducted involving both emerging and developed markets, and varying levels of regulatory environments.

3.2. PRISMA Framework

The PRISMA framework (Moher et al., 2009) is a standardized, evidence-based reporting guideline developed to improve the transparency, accuracy, and quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Page et al., 2021).

The PRISMA framework divides the systematic review process into four key phases. Each phase was addressed as described below for the purpose of this study:

- Identification: The review began with a comprehensive literature search using the Scopus database, chosen for its broad interdisciplinary coverage, especially in finance, technology, and sustainability. A carefully designed Boolean query was developed to combine relevant keywords such as “ESG,” “financial risk,” “machine learning,” and “natural language processing.” To ensure up-to-date coverage, the search was performed until the first quarter of 2025. This initial search considered articles published between 2009 and March 2025.

- Screening: All records were imported into Rayyan3, a collaborative screening tool specifically designed for systematic reviews. Rayyan’s blind screening features and tagging system facilitated the categorization of studies by methodology and ESG focus. During this step, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the PICOC framework were applied. Title and abstract screening resulted in the exclusion of records that did not meet the eligibility criteria, primarily due to: lack of focus on ESG factors, absence of financial risk analysis, no application of ML/AI/NLP techniques, or inappropriate publication types (editorials, book chapters, non-peer-reviewed sources).

- Eligibility: The remaining were retrieved and reviewed in detail to assess compliance with the eligibility criteria. A standardized evaluation form was used to ensure consistent application of inclusion rules. During this phase, we excluded the ones not meeting the inclusion criteria upon detailed examination. Reasons for exclusion were documented and recorded for transparency.

- Inclusion: The final population of studies was ultimately included in the synthesis. A subset of these were identified as systematic or literature reviews, which are discussed in Section 2 to provide context on the current state of the field. To avoid double-counting of evidence and potential bias from including secondary analyses, the quantitative analyses presented in the Section 4 are based on the remaining empirical studies (see Table 1).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria used during screening.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria used during screening.

3.2.1. Research Questions

This study seeks to address several key questions that highlight its unique contributions to the field of ESG-driven financial risk analysis. These questions are organized into two main groups: (i) those related to the integration of ESG, ML, and NLP (RQ1–RQ3), and (ii) those related to the global and conceptual aspects of ESG research in financial risk analysis (RQ4–RQ5).

- RQ1:

- How can NLP techniques improve the accuracy of financial risk prediction models by incorporating data from non-traditional sources?

- RQ2:

- What ML techniques are most effective in predicting financial risks based on ESG data?

- RQ3:

- How do different ESG factors impact the financial stability of companies?

- RQ4:

- How does this study bridge the gap between academic research on ESG and its practical applications in the financial industry?

- RQ5:

- To what extent does this research capture the global relevance of ESG factors in financial risk management across different regions and industries?

These questions help to define the contents of this study and also help to clarify the general understanding of how ESG elements may be included in models of financial risk prediction.

3.2.2. Search Strategy and Data Sources

To ensure a thorough capture of relevant literature addressing ESG integration in financial risk modeling using advanced computational methods, a carefully structured Boolean search equation was developed. The query combines controlled vocabulary and free-text terms to maximize both precision and recall. The search reflects the evolving nature of recent publications and to include the most current studies available:

(“ESG” AND “Environmental, Social, and Governance”) AND (“Financial Impact” OR “Financial Risk”) AND (“predict*” OR “Machine Learning” OR “ML” OR “Artificial Intelligence” OR “AI” OR “Data Science” OR “algorithm*” OR “Natural Language Processing” OR “NLP” OR “Large Language Models” OR “LLM”) AND (PUBYEAR < 2025 OR PUBDATETXT(“January 2025” OR “February 2025” OR “March 2025”))

The rationale behind the search structure is described below:

- The dual inclusion of “ESG” and “Environmental, Social, and Governance” ensures that the query captures both acronym-based and descriptive keyword indexing, reducing the chance of omitting relevant literature and avoiding unrelated articles talking about environmental, social, and governance, in general,.

- The clause (“Financial Impact” OR “Financial Risk”) targets studies focused on the financial consequences or vulnerabilities associated with ESG integration, aligning directly with the central research objective.

- The technological terms (“predict*”, “Machine Learning”, “ML”, “AI”, etc.) are included to filter for studies employing computational and algorithmic techniques. The wildcard * in “predict*” and “algorithm*” captures variations such as prediction, predictive, algorithms, etc., increasing the scope of relevant matches.

- The time filters—PUBYEAR < 2025 and PUBDATETXT(...)—ensure temporal precision.

This search strategy was designed to balance specificity (ensuring relevance to ESG and AI-driven financial risk modeling) with sensitivity (capturing a wide array of terminologies and research designs).

3.2.3. Database Selection

Scopus offers the most comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed literature in business, finance, and management sciences, indexing over 27,000 journals and providing broader coverage than Web of Science in interdisciplinary fields such as sustainable finance (Falagas et al., 2008; Mongeon & Paul-Hus, 2016). Furthermore, Scopus demonstrates substantial overlap with other major databases; studies comparing database coverage have found that approximately 84% of Web of Science records are also indexed in Scopus (Singh et al., 2021). Given that ESG–financial risk research spans multiple disciplines—including finance, environmental science, computer science, and management—Scopus’s interdisciplinary indexing was particularly suited to capture the breadth of relevant literature. Nevertheless, this single-database approach may have excluded some relevant studies indexed exclusively in Web of Science, Google Scholar, or regional databases.

The use of English language publications is widespread in systematic reviews. This approach is further justified by the established role of English as the lingua franca of contemporary scientific communication (Englander, 2014), while this is helpful in ensuring consistency in both screening and analysis, it may result in language bias because some studies may be published in other languages, especially in non-English speaking regions of Europe, Asia, and Latin America. However, as a way of mitigating this problem, we would like to point out that many journals from these regions publish in English, and several high-impact ESG studies from countries such as China and Italy were included in our sample.

3.3. Filtering and Screening

After executing the search queries in Scopus, all retrieved records were exported in RIS format to enable compatibility with reference management and screening tools. Initial filtering was applied to exclude non-English publications and limit the dataset to peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and review articles.

The resulting dataset was imported into Rayyan, which was used as follows:

- Screen titles and abstracts based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Automatically detect and manually verify duplicate records.

- Tag and categorize articles by thematic criteria (e.g., ESG focus, methodology, data sources).

- Track screening decisions through systematic highlighting and annotation features.

This structured approach ensured that the literature selection process was transparent, reproducible, and consistent with best practices for systematic reviews. Metadata for each article—including title, abstract, authors, keywords, publication date, and citation count—was preserved to support traceability and future updates of the review.

To ensure methodological consistency and relevance, all records imported into Rayyan were screened using a predefined set of inclusion and exclusion criteria. These criteria were developed based on the PICOC framework and the research objectives of this review. The goal was to retain only those studies that directly address the intersection of ESG, financial risk, and data-driven methodologies. Table 1 summarizes the specific eligibility criteria applied during the screening phase.

3.4. Data Analysis

This section describes the analytical methods employed to examine the collected data.

3.4.1. Software and Tools

All analyses were performed using Python (version 3.10) with the following libraries:

- pandas: for data manipulation and contingency table creation;

- scipy.stats: for Chi-square and Fisher’s Exact tests;

- nltk: for stopword lists;

- spacy: for lemmatization; (en_core_web_sm model);

- unidecode: for accent normalization;

- wordcloud: for word cloud generation;

- matplotlib: for data visualization.

3.4.2. Text Mining and Word Cloud Generation

To explore the most frequently discussed concepts across the reviewed literature, a text mining approach was applied. The process involved the following steps:

- Corpus construction: A text corpus was built by aggregating relevant textual fields from the extracted data, specifically the “Findings” and “Challenges” from the 64 empirical studies.

- Text preprocessing: The corpus underwent standard NLP preprocessing, including tokenization, lowercasing, removal of URLs, numbers, and punctuation, accent normalization (unidecode), stop word removal (NLTK), and lemmatization (spaCy, en_core_web_sm). Domain-specific terms (e.g., “ESG,” “sustainability”) were also filtered to highlight more distinctive concepts.

- Frequency analysis: Word frequencies were computed using Python’s Counter class to identify the most recurrent terms in the literature.

- Visualization: Word clouds were generated using the WordCloud library in Python, where the size of each word corresponds to its frequency in the corpus. The parameter collocations=False was set to avoid duplicate bigrams.

3.4.3. Statistical Analysis

To examine relationships and associations among categorical variables extracted from the reviewed studies (e.g., ESG dimensions and methodological approaches), statistical tests were performed.

Chi-Square Test of Independence. The chi-square () test is employed to assess whether significant associations exist between categorical variables, specifically between the research methods used and the ESG categories addressed (Agresti, 2002). This non-parametric test evaluates whether the observed frequency distribution differs from the expected distribution under the assumption of independence. The formula used to measure the value required by the chi-square test is represented as shown in Equation (1); where

- = the chi-square test statistic;

- = the observed frequency for category i;

- = the expected frequency for category i under the null hypothesis of independence;

- n = the number of categories (cells) in the contingency table.

Fisher’s exact test. When sample sizes are small or when expected cell frequencies fall below 5, the chi-square approximation becomes unreliable (Kim, 2017). In such cases, Fisher’s exact test was applied as an alternative. Unlike the chi-square test, which relies on asymptotic approximations, Fisher’s exact test calculates the exact probability of obtaining the observed distribution (or a more extreme one) under the null hypothesis of independence. This test is particularly appropriate for contingency tables and was used in our pairwise comparisons between methodological categories. The test computes the probability using the hypergeometric distribution, as shown in Equation (2); where

- = the four cell frequencies in a contingency table;

- n = the total sample size ();

- = the binomial coefficient, representing the number of ways to choose k elements from n elements;

- p = the probability of obtaining the observed (or more extreme) distribution under the null hypothesis.

The two-sided version of the test was employed to detect associations in either direction.

Significance Level. For all statistical tests conducted in this study, a significance level of was adopted. The results yielding a p-value below this threshold () were considered statistically significant, indicating sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis of independence between variables. For marginally significant results (), findings are reported but interpreted with appropriate caution.

4. Results

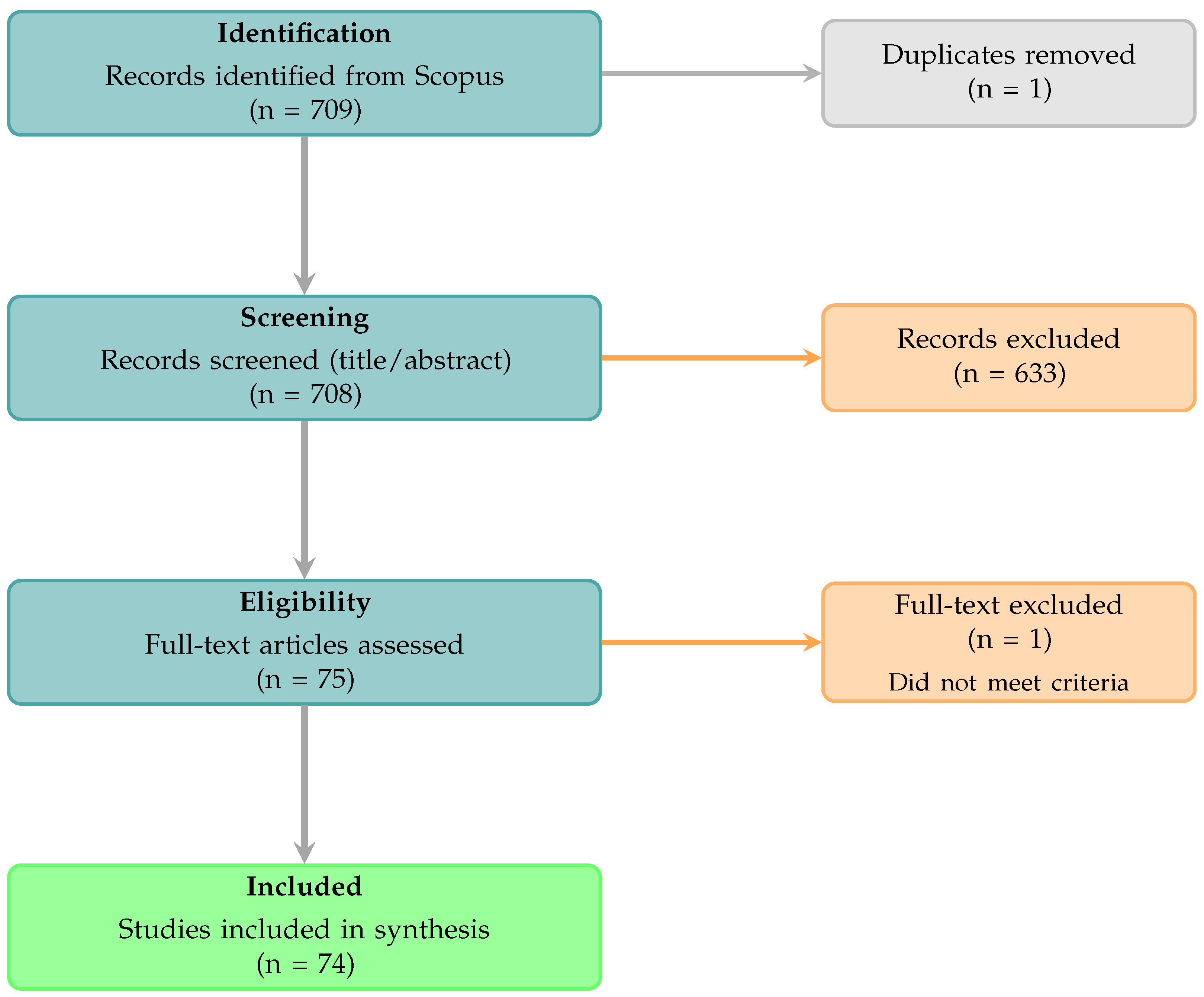

The systematic search conducted in Scopus yielded 709 records published between 2009 and March 2025. After removing one duplicate, 708 unique records were screened based on title and abstract. During this phase, 633 records were excluded for not meeting the eligibility criteria, primarily due to the lack of focus on ESG factors, absence of financial risk analysis, no application of data-driven techniques, or inappropriate publication types. The remaining 75 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 1 article was excluded upon detailed examination. Ultimately, 74 studies were included in the final synthesis. Of these, 10 were identified as systematic or literature reviews, which are discussed in Section 2 to provide context on the current state of the field. To avoid double-counting of evidence and potential bias from including secondary analyses, the quantitative analyses presented in the following sections are based on the remaining 64 empirical studies. Figure 1 illustrates the complete PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the systematic review process.

4.1. Overview and Geographic Distribution

As shown in Table 2, the time distribution of the 74 articles (including reviews) clearly demonstrates a growth trajectory in ESG-related financial risk research. The earliest study in our sample dates from 2018, with only one publication, reflecting the nascent state of this intersection at that time. The period of 2019–2021 shows modest activity, with zero to three articles per year, likely representing the foundational phase where researchers began exploring the integration of ESG factors into financial risk models.

Table 2.

Number of articles included per year.

A marked turning point was observed in 2022, when the number of publications rose to 10—more than triple the number found in the preceding year. This acceleration coincides with significant regulatory developments, including the adoption of the EU CSRD, and increased SEC attention to climate-related disclosures in the United States. The upward trend continues sharply, with 16 articles in 2023 and reaching a peak of 26 articles in 2024, representing 35% of the total sample. The 15 articles from early 2025 (partial year, January–March) suggest that this growth trajectory is likely to continue.

This growth reflects the expanding interest in sustainable finance research and applications. This post-2020 trend is supported by the convergence of three elements: (i) the availability and increase in ESG data sources and raters, which allowed more advanced quantitative analysis to occur; (ii) the advancement of ML and NLP technology relevant to finance; and (iii) increased demands by financial actors and authorities regarding the transparency of ESG risk evaluation after the pandemic triggered by the COVID-19 crisis, which underlined the relevance of other than financial risk drivers.

Table 3 shows the top 10 countries most cited across the 64 studies. China leads the distribution with 13 studies, closely followed by Italy, which has 10 studies, reflecting the increasing number of studies and corresponding increased corporate support and involvement in ESG considerations. India and the US are also very visible, having 6 studies each, and then follows the UK, which has 4 studies, showing the increased involvement of each of these countries in financial studies involving ESG considerations.

Table 3.

Top 10 countries mentioned across 64 empirical studies.

4.2. Methodological Approaches

Table 4 presents the distribution of methodological approaches identified in the 64 empirical studies, grouped into four main categories: Statistical Methods, ML/AI, NLP, and Other approaches.

Table 4.

Specific analytical methods employed in 64 empirical studies.

As shown in Table 4, traditional statistical techniques remain dominant (31 studies, 48%), which reflects their entrenched role in financial research. However, the presence of AI and ML methods (25 studies, 39%) is notable and expected to grow in a rapidly evolving field like ESG. The limited use of NLP techniques (five studies, 8%) suggests an opportunity for methodological expansion in future research, especially considering the rise in unstructured ESG data from reports, media, and social platforms.

This review shows that ML models are proving to be highly effective tools for ESG-based financial risk prediction. Algorithms like Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and CatBoost stand out for their ability to capture complex relationships between ESG factors and financial outcomes with high accuracy across multiple evaluation metrics (Goldberg & Mouti, 2022; Taskin et al., 2025). Their strength lies in handling the nonlinear patterns inherent in ESG data that traditional econometric models often miss. Similarly, neural network architectures, including Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and hybrid approaches combining Self-Organizing Maps with ANN (SOM-ANN), have demonstrated superior performance in modeling the multidimensional nature of ESG–financial relationships (Cheong et al., 2025; Lin & Jin, 2023), while Logistic Regression does not achieve the same predictive power as more advanced models, it remains a viable option when model interpretability is prioritized—a critical consideration given regulatory requirements for transparent decision-making in financial institutions (Taskin et al., 2025). Taken together, these findings highlight the value of ML in capturing subtle ESG signals that influence financial risk (D’Ecclesia et al., 2024; Xue et al., 2024), while also recognizing that traditional statistical methods retain an important role when explainability and auditability are essential.

The role of NLP in ESG–financial risk research remains limited but promising. Among the five empirical studies employing NLP techniques, several demonstrate its potential for extracting risk-relevant information from unstructured sources. Hajek et al. (2024) found that ESG report content significantly predicts corporate credit ratings, while Shang et al. (2025) combined NLP with traditional methods to analyze corporate debt default risk. Cardoni and Kiseleva (2023) applied text mining to examine the relationship between sustainable governance and firm value, and C. Zhang and Hu (2025) used NLP to analyze the relationship between ESG performance and firms’ productivity. These studies suggest that NLP can capture qualitative ESG signals—such as disclosure tone, reporting completeness, and governance language—that structured data alone cannot provide. However, most applications remain limited to basic techniques like keyword extraction and sentiment analysis, with more advanced approaches such as transformer-based models (BERT, GPT) largely unexplored in this domain.

4.3. ESG Dimension Analysis

Table 5 presents the distribution of the 64 empirical studies according to their ESG orientation, based on each study’s dominant ESG Focus (single or combined pillars). Studies may still consider other ESG dimensions alongside their primary focus.

Table 5.

Distribution of articles by ESG Focus.

Studies focused on all three ESG dimensions simultaneously represent the largest category (28 studies, 44%), followed by those focusing on Governance and Environmental aspects combined (12 studies, 19%). The Social dimension alone is the focus of only three studies (5%), suggesting limited scholarly attention to non-financial performance metrics tied to stakeholder expectations. Governance is a common term, and it is presumably used due to its relevance to risk and control. Environmental indicators are gaining prominence, reflecting the growing importance of climate-related disclosure.

To examine whether there is a relationship between the type of model used and the ESG dimension studied, a chi-square test of independence was performed on the 64 empirical studies. Table 6 presents the contingency table showing the observed frequencies for each combination of method and ESG category.

Table 6.

Contingency table: method × ESG category (64 Empirical Studies).

Table 7 shows the expected frequencies under the assumption of independence between variables, as calculated for the chi-square test.

Table 7.

Expected frequencies for method × ESG (chi-square test).

The result of the chi-square test was not statistically significant (, , , ). This indicates that, in our sample, the type of modeling method does not appear to influence which ESG dimension is analyzed. Table 8 summarizes the most frequently studied ESG category for each methodological approach.

Table 8.

Most frequent ESG category per method.

As shown in Table 8, most methodological approaches tend to focus on all ESG dimensions simultaneously. Studies classified as “Other” show no dominant ESG category, with equal representation across ESG, Governance, and the Governance–Environmental combination.

While the global chi-square test indicates no significant association between methodological approaches and ESG dimensions when focusing on all categories simultaneously, a more granular analysis using Fisher’s exact test for pairwise comparisons reveals nuanced patterns between the two dominant methodological categories: AI/ML () and Statistical methods ().

Table 9 presents the results of these pairwise comparisons. The analysis focused on the presence or absence of specific ESG components across methodological approaches.

Table 9.

Fisher’s exact test: pairwise comparison between AI/ML and statistical methods.

The pairwise analysis reveals one statistically significant finding. The combination of Governance and Environmental (GE) dimensions is significantly more common in AI/ML studies (32.0%) than in Statistical studies (9.7%, ). Additionally, AI/ML methods demonstrate a stronger association with studies that incorporate the Environmental component: 92.0% of AI/ML studies focus on Environmental factors compared to 74.2% of Statistical studies (). Studies focusing exclusively on Governance—without Environmental or Social dimensions—are found only among Statistical methods (12.9% vs. 0% in AI/ML, ).

These patterns suggest a methodological specialization within the field. Researchers appear to preferentially apply ML techniques when analyzing environmental factors, possibly due to the greater complexity and heterogeneity of environmental data (carbon emissions, energy consumption, and climate risk indicators) that benefit from ML algorithms’ capacity to capture nonlinear relationships and process diverse data sources. Conversely, governance-focused studies, which often rely on well-structured categorical variables (board composition, ownership structure, and audit quality), may be adequately addressed through traditional econometric approaches such as panel regression and fixed effects models.

4.4. Data Sources and Study Types

The quality and reliability of ESG research depend significantly on the data sources employed. Table 10 presents the main ESG data sources used across the 64 empirical studies, revealing a concentrated reliance on a limited number of commercial providers.

Table 10.

ESG Data sources used in 64 empirical studies.

Refinitiv (formerly Thomson Reuters) emerges as the dominant data provider, utilized in 23 studies (36% of the empirical sample), followed by Bloomberg with 16 studies (25%). Together, these two commercial providers account for over half of the data sources employed in ESG–financial risk research. This concentration raises important considerations regarding data accessibility and potential methodological biases, as smaller research institutions may face cost barriers when accessing these proprietary databases.

ESG rating agencies employ different techniques. Refinitiv rates entities based on percentile ranks, utilizing more than 450 ESG factors. Bloomberg utilizes a scoring technique based on disclosures. MSCI concentrates on industry-related topics and is forward-looking. Correlation coefficients as low as 0.38 have been reported by Berg et al. (2022) between major ESG rating providers. These disparities occur based on differences in scope, measurement, and weight. These inconsistencies may impact the comparability of research, causing divergence in findings based on the usage of possibly contrasting suppliers, such as Refinitiv, Bloomberg, and MSCI, among others, despite focusing on the identical set of entities and periods. Recent research has started to examine ways in which these disparities impact particular financial performances; for instance, Sun et al. (2025) demonstrate that divergent ESG evaluations create sustainability uncertainty that significantly impacts supply chain financing decisions in China. Future research should explicitly address this limitation through multi-source validation or sensitivity analyses across rating providers.

The differences in ESG data may influence how comparable and reliable models are. When research is conducted using different ESG data suppliers, it is possible that variation in findings may stem from differences in data measurement and not actual economic differences. For example, if one study finds that ESG performance reduces credit risk using data from Refinitiv, but another study finds no relationship using data from Bloomberg, it may be due to differences in how each provider measures environmental and governance aspects.

This heterogeneity poses three specific challenges for the field:

- Replication difficulties: Replication of research in this way is not possible if the source of the ESG ratings is private. It is possible that the same company has been rated quite differently by two different providers.

- Model portability: A model trained on data from one ESG provider may not work well with data from another provider. This is a problem for financial institutions that use different data subscriptions.

- Meta-analytic synthesis: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses aggregating findings across studies face the challenge that effect sizes may not be commensurable when underlying ESG measurements differ fundamentally.

Future research should prioritize multi-provider validation studies that explicitly test whether substantive conclusions hold across ESG data sources, and the emerging ISSB standards may eventually provide a common measurement framework that addresses these comparability concerns.

Regional data sources also play a significant role, particularly CSMAR (China Stock Market and Accounting Research Database), which appears in seven studies focusing on Chinese markets. This reflects the growing academic interest in ESG dynamics within emerging economies and the need for region-specific data infrastructure. The World Bank serves as a complementary source for macroeconomic and institutional indicators in three studies, and is often used simultaneously with more detailed ESG information at the individual enterprise level.

Notably, the diversity of data sources introduces challenges for cross-study comparability. Different providers employ varying methodologies for ESG scoring, which may explain some of the heterogeneity observed in research findings across the literature. This underscores the importance of transparency in data source selection and the potential value of studies that explicitly compare results across multiple ESG data providers.

Understanding the methodological nature of the reviewed literature provides insight into the maturity and direction of ESG–financial risk research. Table 11 categorizes the 74 identified studies according to their primary research design.

Table 11.

Distribution of study types.

The distribution reveals a strong empirical orientation within the field, with 64 studies (86%) conducting original quantitative analyses using firm-level or market data. This predominance of empirical work reflects the applied nature of ESG–financial risk research, where practitioners and academics seek actionable insights for investment decisions and risk management frameworks.

The 10 systematic and literature reviews (14%) serve a complementary but essential function, synthesizing existing knowledge and identifying research gaps. These reviews are described in detail in Section 2 and were excluded from the quantitative analyses in subsequent sections to avoid double-counting of evidence. The presence of multiple recent reviews (seven published in 2024–2025) indicates a consolidation phase in the literature, where researchers are increasingly attempting to organize and evaluate the rapidly growing body of empirical evidence.

4.5. Application Scope

A comprehensive understanding of how ESG factors are applied in financial research requires examining the specific outcomes and risk dimensions that researchers have investigated. Table 12 presents the financial outcomes and risk dimensions studied across the reviewed literature, organized by application area.

Table 12.

Application scope: financial outcomes and risk dimensions studied (64 Empirical Studies).

4.5.1. Corporate Financial Performance

The largest application area focuses on firm performance metrics, with 25 studies examining traditional financial indicators such as Return on Assets (ROA), Return on Equity (ROE), and Tobin’s Q. This concentration reflects the fundamental research question driving the field: whether ESG integration creates or destroys shareholder value. The predominance of accounting-based metrics (ROA, ROE) alongside market-based measures (Tobin’s Q) suggests researchers are attempting to capture both operational efficiency and market valuation effects of ESG practices.

4.5.2. Risk Assessment

Risk-related applications represent the second major research stream, encompassing three distinct dimensions:

- Credit Risk/Default Risk (ten studies): This category examines how ESG factors influence corporate creditworthiness and bankruptcy probability. Studies in this area are particularly relevant for financial institutions developing ESG-integrated credit scoring models and for rating agencies incorporating sustainability metrics into their assessments.

- Stock Price Volatility/Market Risk (eight studies): Research in this area investigates whether strong ESG performance reduces stock price fluctuations and systematic risk exposure. Findings generally suggest that ESG acts as a risk mitigation mechanism, potentially lowering the cost of equity capital.

- Bank Risk-Taking (four studies): A specialized stream focusing on how ESG considerations affect risk appetite and risk management practices within banking institutions. This area has gained prominence following regulatory emphasis on climate-related financial risks.

4.5.3. Other Application Areas

Eight studies focus specifically on ESG disclosure quality, examining both the determinants and consequences of corporate sustainability reporting. This research stream addresses critical questions about information asymmetry, greenwashing detection, and the role of mandatory versus voluntary disclosure regimes. The growing regulatory emphasis on standardized ESG reporting (e.g., CSRD in Europe, SEC climate rules in the US) makes this application area increasingly relevant for practitioners and policymakers.

Six studies develop predictive models for ESG scores themselves, rather than using ESG as a predictor of financial outcomes. This emerging application area responds to practical needs: the high cost of commercial ESG ratings, delays in score publication, and coverage gaps for smaller firms. ML approaches are particularly prominent in this category, with models trained to predict ESG scores from publicly available financial and textual data.

Five studies focus specifically on carbon emissions and climate risk, reflecting the urgency of climate-related financial concerns. This specialized stream examines how carbon intensity affects firm valuation, how climate transition risks manifest in credit spreads, and how physical climate risks impact asset prices. The concentration of environmental-specific studies signals the field’s response to regulatory initiatives such as the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations.

Several patterns emerge from this application landscape. First, there is a notable imbalance: corporate performance and credit risk dominate, while social-specific applications (e.g., labor practices and community impact) remain underexplored. Second, most studies adopt a firm-level perspective; portfolio-level and systemic risk applications are scarce. Third, the temporal dimension is often overlooked—few studies examine how ESG–financial relationships evolve over time or differ across economic cycles. These gaps suggest promising directions for future research.

4.6. Thematic Analysis from Word Clouds

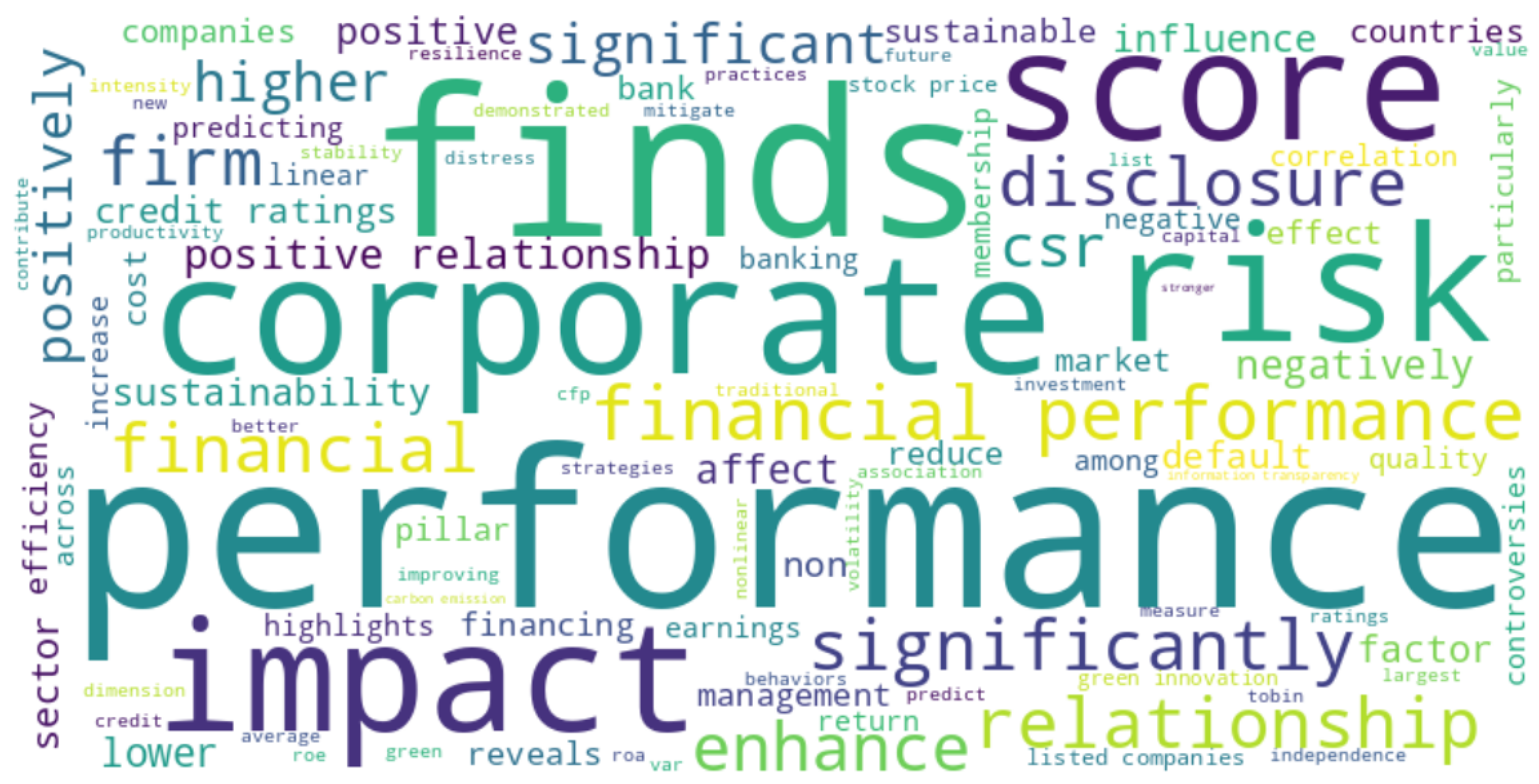

To complement the quantitative analysis, a text mining approach was applied to the “Findings” and “Challenges” extracted from the 64 empirical studies. Word clouds were generated after standard NLP preprocessing (tokenization, lemmatization, stopword removal, and domain-specific filtering) to visualize the most salient concepts across the literature. This approach enables the identification of recurring themes, dominant research patterns, and the overall tone of reported results.

The word cloud derived from the “Findings” (Figure 2) reveals the thematic priorities of ESG–financial risk research. The most prominent terms—performance, firm, financial, relationship, and corporate—underscore the literature’s central focus on establishing empirical linkages between ESG factors and corporate financial outcomes.

Figure 2.

Word cloud of research findings.

Several semantic clusters emerge from the Findings visualization:

- Performance-oriented terms: The dominance of performance, financial, firm, and corporate reflects the literature’s emphasis on measuring tangible financial impacts of ESG integration. Terms such as enhance, improve, and positive suggest that a majority of studies report beneficial associations between ESG practices and financial outcomes.

- Risk and stability concepts: Words like risk, default, credit, and stability indicate substantial research attention to how ESG factors influence various dimensions of financial risk, including credit risk, default probability, and overall corporate resilience.

- Disclosure and transparency: The presence of disclosure, transparency, score, and rating highlights the importance of ESG reporting quality and third-party assessments in mediating financial outcomes.

- Stakeholder and governance dimensions: Terms such as investor, stakeholder, board, and management reflect research attention to governance mechanisms and stakeholder relationships as channels through which ESG affects financial performance.

- Methodological indicators: The appearance of significant, positive, negative, and relationship indicates that most studies employ hypothesis-testing frameworks to establish statistical associations, with findings predominantly reporting significant positive relationships.

Notably, the relatively high frequency of positive compared to negative suggests an optimistic consensus in the literature regarding ESG’s beneficial effects on financial outcomes, though this may also reflect publication bias toward positive findings.

Complementing the analysis of findings, we also examined the “Challenges” reported across the 64 empirical studies. Understanding the obstacles and limitations acknowledged by researchers is crucial for identifying methodological gaps, data constraints, and areas requiring further development. This analysis reveals not only what the field has achieved, but also what barriers persist in translating ESG research into practical applications.

The “Challenges” word cloud (Figure 3) provides insight into the methodological and practical obstacles facing ESG–financial risk research. The prominence of financial, risk, performance, and limitation indicates that challenges are often framed in relation to the core constructs under investigation.

Figure 3.

Word cloud of research challenges.

Key challenge clusters include

- Data-related constraints: Terms such as data, lack, limited, sample, and availability point to persistent data quality issues. Researchers frequently cite insufficient ESG data coverage, inconsistent reporting standards, and limited historical time series as significant obstacles to robust analysis.

- Methodological limitations: Words like generalizability, complexity, model, and interpretation reflect concerns about the external validity of findings. Many studies acknowledge that results derived from specific geographic or sectoral contexts may not transfer to other settings.

- Measurement challenges: The presence of score, measure, indicator, and assessment highlights ongoing difficulties in operationalizing ESG constructs. Disagreements among ESG rating providers and the lack of standardized metrics complicate cross-study comparisons.

- Market and contextual factors: Terms such as market, country, sector, and industry indicate that researchers recognize the context-dependent nature of ESG–financial relationships. Regulatory environments, cultural factors, and industry characteristics introduce heterogeneity that challenges universal conclusions.

- Stakeholder and disclosure issues: Words like stakeholder, disclosure, transparency, and information suggest challenges related to corporate reporting practices, including concerns about greenwashing and the reliability of self-reported ESG information.

- Endogeneity and causality: Although less visually prominent, terms related to bias, selection, and endogeneity appear in the corpus, reflecting methodological concerns about establishing causal relationships rather than mere correlations.

As a synthesis of thematic patterns, comparing the two word clouds reveals an important asymmetry: while the “Findings” cloud emphasizes positive outcomes and established relationships, the “Challenges” cloud highlights persistent uncertainties and limitations. This contrast suggests that while the field achieved substantial progress in documenting ESG–financial associations, significant methodological and data-related hurdles remain before these findings can be translated into reliable predictive models for practical application.

The thematic analysis also reveals a notable gap: terms related to emerging technologies (ML, NLP, and AI) appear with moderate frequency in the findings but are largely absent from the challenges discourse. This may indicate that while advanced computational methods are increasingly employed, their specific limitations—such as interpretability concerns, overfitting risks, and computational requirements—are not yet systematically discussed in the literature.

4.7. Summary of Key Findings

This systematic review analyzed 64 empirical studies examining the intersection of ESG factors and financial performance using quantitative methods (after excluding 10 systematic reviews from the 74 identified articles). The key findings are summarized as follows:

- Methodological landscape: Traditional econometric approaches remain dominant (48%), followed by AI/ML methods (39%) and NLP techniques (8%). The chi-square test revealed no significant association between methodological approach and ESG dimension studied (, ), suggesting that method selection is independent of the specific ESG focus.

- ESG dimension coverage: Integrated ESG studies focusing on all three dimensions simultaneously dominate the literature (44%), followed by combined Governance and Environmental focus (19%). The Social dimension alone receives minimal attention (5%), highlighting a gap in stakeholder-focused research.

- Geographic distribution: Research output is concentrated in China (13 studies), Italy (10 studies), and the United States and India (6 studies each), reflecting both regulatory developments and emerging market interest in ESG integration.

- Temporal trends: Publication output shows substantial growth, with 2024 representing the peak year, underscoring accelerating academic interest in ESG–financial performance relationships.

- Context-dependent effects: ESG integration significantly influences corporate financial stability, though effects vary by region and sector, reflecting the context-dependent relevance of ESG in financial risk management.

- Academic-practice gap: A gap persists between academic ESG models and practical adoption in financial institutions, particularly regarding interpretability and operational deployment.

- ML effectiveness: ML models—especially ensemble methods and neural networks—demonstrate high effectiveness in ESG-based risk prediction, signaling a methodological shift toward data-driven approaches.

- NLP potential: Most models rely on structured ESG data, limiting their scope. NLP methods incorporating unstructured data (e.g., media sentiment analysis, ESG disclosure mining) show promise for improving model accuracy and capturing dynamic risk signals.

These findings underscore the need for regionally sensitive and ethically grounded ESG modeling frameworks, as well as the potential of advanced AI techniques to bridge academic knowledge and practical financial risk assessment.

5. Discussion

This section synthesizes the findings of the systematic review in relation to the research questions posed at the outset. We discuss the implications of our results, identify critical gaps in the current literature, and outline open problems that warrant future investigation.

5.1. Addressing the Research Questions

5.1.1. RQ1: How Can NLP Techniques Improve Financial Risk Prediction Models?

Our review identified only 5 studies (8%) explicitly employing NLP techniques for ESG-based financial risk prediction, indicating that this methodological approach remains underutilized despite its significant potential. The studies that did incorporate NLP demonstrated promising results in several key areas.

First, NLP enables the extraction of risk-relevant information from unstructured sources that traditional models cannot process, including sustainability reports, CSR disclosures, news articles, and social media content. These sources often contain early warning signals of ESG-related risks—such as environmental controversies, labor disputes, or governance failures—that precede their reflection in structured financial data.

Second, sentiment analysis and topic modeling techniques allow researchers to capture qualitative dimensions of ESG performance that standardized ratings may overlook. For instance, the tone and specificity of environmental disclosures can reveal management commitment beyond what numerical scores convey.

However, the current application of NLP in this field faces limitations. Most of the research is based on fairly simple techniques such as keyword extraction, Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF), and simple sentiment analysis using predefined lists of words. The downside is that keyword extraction is unable to take context and negations into consideration, and predefined word lists for sentiment analysis are often unsuited for the language of finance and sustainability. More recent approaches like transformer models (BERT, FinBERT, and ClimateBERT), large language models (GPT-4 and Claude), and domain-specific embeddings have not been widely used in ESG–financial risk analysis. However, they offer significant benefits: they can understand complex sustainability narratives, detect greenwashing through textual consistency analysis, support the analysis of disclosures in non-English languages, and identify emerging sustainability issues that were not present in training data. This represents a significant opportunity for future research.

5.1.2. RQ2: What ML Techniques Are Most Effective for ESG-Based Risk Prediction?

The review reveals a clear hierarchy of methodological effectiveness among the 25 studies employing AI/ML approaches. Ensemble methods—particularly Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and CatBoost—consistently outperformed traditional statistical models across multiple evaluation metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, AUC).

Neural network architectures, including ANN and SOM-ANN, demonstrated superior capability in capturing the nonlinear relationships between ESG factors and financial outcomes. These models proved especially effective for credit risk prediction and default probability estimation, where complex interdependencies among environmental, social, and governance variables influence outcomes in non-additive ways.

Logistic regression, while less powerful than ensemble methods, remains a viable option when model interpretability is prioritized. Several studies noted that regulatory requirements in financial services often mandate explainable models, creating a trade-off between predictive accuracy and operational deployability.

An important challenge that demands more attention is the “black box” problem of high-performing ML models and its implications for financial regulations. Financial regulations such as the EU AI Act, or rules from the Basel Committee regarding managing risks associated with models, or SEC regulations regarding fair lending practices, all call for models that are explainable and auditable to some degree. The problem is that some of the models that are able to accurately predict ESG risks—neural nets or ensemble models—cannot provide clear, rule-like explanations that regulators would find satisfactory for high-value financial applications.

Recent solutions involve post hoc explanation techniques; for example, SHAP and LIME, interpretable models that are easily understood; for example, decision trees, Generalized Additive Models (GAMs), and techniques that combine ML model predictions with rule extraction that are easily interpretable. However, based on our review, very few studies have specifically addressed the aspect of ML related to interpretability techniques. Still, the aspect of interpretability is not yet adequately investigated, requiring immediate intervention for practical applications.

A critical gap identified in this area is the limited use of deep learning architectures. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), which have proven effective in other financial applications, are virtually absent from ESG-focused research. Similarly, hybrid approaches combining multiple ML techniques with traditional econometric methods remain rare, despite their potential to leverage the strengths of both paradigms.

5.1.3. RQ3: How Do Different ESG Factors Impact Financial Stability?

The analysis of ESG dimension distribution reveals important patterns in how individual factors affect corporate financial stability. Studies focusing on all three ESG dimensions simultaneously (44%) generally report positive associations between integrated ESG performance and financial outcomes, supporting the view that sustainability practices create long-term value.

However, when examining individual dimensions, the effects are more nuanced:

- Environmental factors: Studies focusing on environmental aspects (8 studies exclusively, 12 combined with governance) consistently find that strong environmental performance reduces credit risk and enhances firm valuation, particularly in carbon-intensive industries. Climate risk disclosure and carbon emission management emerge as key predictors of financial resilience.

- Governance factors: Governance-focused studies (5 exclusive, 12 combined with environmental) emphasize the role of board composition, executive compensation alignment, and transparency mechanisms in reducing agency costs and information asymmetry. Governance factors show the strongest association with credit ratings and default risk.

- Social factors: The social dimension receives the least attention (three studies exclusively), representing a significant gap. Available evidence suggests that social performance—including labor practices, community relations, and human rights policies—affects firm reputation and stakeholder trust, but the financial materiality of these factors remains less established than for environmental and governance aspects.

The underrepresentation of the Social dimension warrants deeper examination, as it may reflect multiple underlying factors:

- Data limitations: Social performance is more challenging to measure compared to environmental metrics (such as carbon emissions and energy consumption) and governance metrics (such as board composition and ownership). The likes of diversity and happiness of employees and societal footprint cannot be measured uniformly.

- Measurement challenges: While environmental performance can be quantified in physically measurable terms, social performance lacks the ability to be distinctly measured in physical terms as it can only be judged through self-evaluation or third-party reviews in many instances.

- Perceived financial materiality: Investors and researchers may perceive social factors as having weaker or more indirect links to financial outcomes compared to environmental risks (climate transition, carbon pricing) or governance failures (fraud, mismanagement). This perception—whether accurate or not—shapes research priorities.

- Structural biases in ESG research: The academic finance community’s traditional focus on quantifiable risk factors may systematically disadvantage research on social dimensions, which often require qualitative or mixed-methods approaches.

- Temporal lag: Social risks such as labor disputes, human rights problems, or resistance from the community may emerge in a timeframe longer than environmental and governance risks, thus becoming difficult to quantify from a financial perspective in typical studies.