Abstract

In today’s rapidly changing economic landscape, financial stability plays a crucial role in ensuring individual and societal well-being. Millennials encounter unique financial pressures, including shifting labor markets, high housing costs, and economic uncertainty, which may impact their financial stability and broader life choices. This cross-cultural comparative study investigates the interplay between financial stability and environmental sentiment among Greek and Dutch Millennials, exploring how cultural differences influence these dynamics. Utilizing a quantitative research methodology, the study analyzed responses from a convenient sample of 426 participants across Greece and the Netherlands, employing measures such as a multidimensional construct of financial stability and the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) scale to assess environmental attitudes. The results indicated a significant positive correlation between perceived financial stability and pro-environmental sentiment in both cohorts, suggesting that economic security is a key facilitator of environmental engagement irrespective of cultural context. However, no significant differences were found in environmental sentiment between the two groups, highlighting a possible universal environmental awareness among Millennials transcending economic disparities. These findings suggest that policies aimed at enhancing financial stability may simultaneously foster greater environmental stewardship. The study underscores the importance of integrating economic and environmental policy to promote sustainable development globally among younger populations.

1. Introduction

Understanding the relationship between financial stability and environmental sentiment is critical as societies grapple with the dual challenges of economic security and environmental sustainability. This interplay is particularly evident among younger generations, whose financial behaviors and attitudes toward sustainability will shape future economic and environmental outcomes (Surmacz et al., 2024). Exploring these dynamics can provide valuable insights into how financial literacy and environmental awareness intersect to influence decision-making. Furthermore, understanding these relationships could inform targeted policies and educational initiatives aimed at fostering both financial well-being and sustainable practices among future leaders.

This research explores the nuances of this relationship among Millennials in Greece and the Netherlands, providing insights into how financial perceptions influence environmental attitudes across different cultural landscapes. The focus on Millennials is pertinent given their increasing demographic and economic influence and their recognized concern for sustainability (Gómez-Román et al., 2021; Smith & Brower, 2012).

Millennials have been at the forefront of the sustainability movement, often showing greater environmental concern than previous generations (Sarrasin et al., 2022). However, the extent to which financial stability influences their environmental attitudes remains underexplored, especially across different cultural contexts. Previous research has established a link between economic conditions and environmental concerns, with greater financial security often associated with higher environmental engagement (Gifford & Nilsson, 2014; Sun et al., 2022).

This study seeks to expand on this foundation by exploring how these dynamics play out in two economically diverse European countries. Greece’s GDP in 2023 was approximately EUR 224 billion, with growth projected at 2.1% in 2024. Key drivers include domestic demand and investment, though challenges persist, such as high public debt, which stood at 171% of GDP in 2023, and unemployment, which remains one of the highest in the EU at 10.4% (OECD, 2023b). The Netherlands, a more economically mature country, recorded a GDP of about EUR 1.03 trillion in 2023. It boasts strong performance in advanced sectors like technology and finance, coupled with low unemployment rates (3.5% in 2023). Although its economic growth was relatively modest at around 1%, the stability of its economy provides a sharp contrast to Greece’s (OECD, 2023b).

In terms of green energy, Greece has made significant strides in renewable energy, achieving over 50% of its electricity generation from renewables in 2023. Solar power dominates this mix, accounting for around 40% of the installed renewable energy capacity. Wind energy is the second-largest contributor, with a cumulative capacity of 5.2 GW and a generation of approximately 10.9 TWh in 2023. The country is committed to doubling its renewable capacity by 2030, driven by investments in solar and wind technology and planned offshore wind farms. Despite these efforts, challenges remain, including improving efficiency in transportation and buildings to enhance electrification and decarbonization efforts (OECD, 2025).

Similarly, the Netherlands has achieved notable progress in its renewable energy sector. In the first half of 2024, renewable sources generated more electricity than fossil fuels for the first time, with renewables accounting for 53% of the total electricity output. This increase is largely attributed to wind power, which grew by 4.4 billion kWh to 17.4 billion kWh, bolstered by new offshore wind farms and upgrades to land-based installations. Consequently, coal-powered electricity generation declined to 3.9 billion kWh, as renewable options became more cost-competitive (Reuters, 2024).

Greece and the Netherlands have made significant strides in integrating renewable energy into their energy grids, reflecting their commitment to sustainable energy transitions. Greece, has set ambitious goals, focusing on investments in solar and wind technologies, including planned offshore wind farms. Despite these advancements, challenges persist in enhancing efficiency within the transportation and building sectors to further electrification and decarbonization efforts. Similarly, the Netherlands has achieved notable progress in its renewable energy sector. Both countries have leveraged their unique geographical and climatic conditions to harness renewable resources effectively. Greece’s abundant sunlight and favorable wind conditions have propelled its solar and wind energy sectors, while the Netherlands has utilized its technological expertise and policy frameworks to overcome geographical limitations, establishing itself as a leader in renewable energy adoption. However, both countries face ongoing challenges in their energy transitions. Greece must address inefficiencies in transportation and building sectors to fully realize the benefits of electrification and decarbonization. The Netherlands continues to work towards reducing greenhouse gas emissions and ensuring energy security as it phases out fossil fuels. Thus, the experiences of Greece and the Netherlands underscore the critical role of renewable energy in national energy strategies and the multifaceted efforts required to transition towards more sustainable energy systems.

The choice of Greece and the Netherlands presents an opportunity to examine these issues in contrasting economic environments. The Greek economy has faced significant challenges, including prolonged recessions and austerity measures, while the Dutch economy is comparatively stable and prosperous (OECD, 2023a). These differing economic backgrounds provide a backdrop for investigating how financial stability influences environmental sentiment in varying cultural and economic settings. Greece and the Netherlands also differ significantly in their approaches to environmental policy and sustainability. The Netherlands is recognized as a global leader in sustainability, renewable energy adoption, and environmental protection policies. The country has a strong environmental consciousness, with extensive government and societal efforts directed toward mitigating climate change and promoting sustainable practices. In contrast, Greece, while making strides in environmental policy, has historically faced challenges related to environmental regulation, particularly due to its economic constraints (Drosos et al., 2019). This variation in environmental policy and public engagement allows for a comparative analysis of how Millennials in each country respond to environmental issues in the context of differing levels of environmental awareness and infrastructure. Greece and the Netherlands also offer a diverse cultural background, which is essential in understanding how societal values and norms influence environmental sentiment. Dutch culture is known for its progressive stance on environmental issues, driven by a deep-rooted sense of social responsibility and collective action. Greek culture, while also valuing nature and the environment, has historically placed more emphasis on economic recovery and personal financial security due to its recent economic hardships (Skordoulis et al., 2024). This cultural contrast provides a valuable framework for exploring how cultural differences impact Millennials’ views on sustainability and their ability to engage with environmental causes.

As far as the above analysis is concerned, the selection of Greece and the Netherlands for this study is based on their distinct economic conditions, environmental policies, and cultural attitudes toward sustainability. Greece has faced prolonged financial instability, high public debt, and significant unemployment (Skordoulis et al., 2018), factors that influence its environmental policies and public engagement with sustainability. In contrast, the Netherlands, with its stable and advanced economy (Hasan et al., 2024), has established itself as a leader in environmental consciousness and policy implementation (De Haas et al., 2021). This contrast allows for a meaningful examination of how financial stability affects environmental sentiment. Other European countries may share some of these characteristics, but few present as stark a contrast as Greece and the Netherlands in terms of both economic conditions and environmental approaches. For example, Western European nations like Germany or France have strong economies but do not exhibit the same level of financial instability as Greece. Meanwhile, Southern European countries such as Spain or Italy share some economic challenges with Greece but do not match its level of financial distress or the Netherlands’ leadership in environmental policy (Ntanos et al., 2018b).

Moreover, by focusing on Millennials, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how generational characteristics can interact with economic conditions to shape environmental attitudes. Millennials, born between 1981 and 1996, are a crucial demographic for examining the intersection of financial stability and environmental sentiment. Millennials are particularly relevant for this study as they have lived through significant economic and environmental upheavals. Moreover, Millennials are considered an environmentally conscious generation. They have been at the forefront of environmental movements and are more likely than previous generations to prioritize sustainability in their personal and professional lives. This makes them an ideal group to study in the context of environmental sentiment, as their values, behaviors, and attitudes toward sustainability can have a significant impact on broader societal trends, including consumption patterns, voting behaviors, and corporate social responsibility demands. These experiences shape their views on financial stability and their willingness to engage with environmental issues (Skordoulis et al., 2023). Last, despite their environmental awareness, Millennials are also facing unique economic challenges, particularly in relation to financial stability. In both Greece and the Netherlands, Millennials have been affected by shifting labor markets, high housing costs, and, in some cases, economic uncertainty. These factors may influence their ability or willingness to engage with environmental issues, as financial insecurity often forces individuals to prioritize immediate economic needs over long-term environmental goals. Thus, this analysis is crucial for policymakers and environmental organizations aiming to engage younger generations in sustainability efforts effectively.

Thus, the present study specifically focuses on Millennials rather than other age groups due to their unique positioning at the intersection of economic challenges and environmental consciousness. Born between 1981 and 1996, Millennials have experienced significant economic upheavals, such as the global financial crisis, which have impacted their financial stability and influenced their perspectives on sustainability (Dunlap & York, 2008). Prior research has identified a generational pattern in the relationship between financial security and environmental concern, with younger cohorts often expressing strong pro-environmental values, but struggling to act on them due to economic constraints. Despite facing financial stressors, Millennials are often characterized by a heightened awareness of environmental issues and a willingness to engage in sustainable behaviors (Brick & Lai, 2018; Gifford & Nilsson, 2014).

Prior research suggests that younger generations are increasingly vocal and engaged in climate-related activism, especially via digital platforms (Tyson et al., 2021), and expect stronger climate action from institutions, including employers (Deloitte, 2022). However, economic constraints can create a value–action gap, where pro-environmental attitudes do not consistently lead to environmentally friendly behavior (Gatersleben et al., 2002; Gifford & Nilsson, 2014).

This dynamic is especially relevant to the “luxury good hypothesis” of environmentalism, which posits that environmental concern and action increase as economic security improves (Franzen & Meyer, 2010; Ntanos et al., 2018b; Skordoulis et al., 2023). By examining Millennials in two economically and culturally distinct countries—Greece, which has endured prolonged economic austerity, and the Netherlands, with a comparatively affluent and stable economy—the present study provides a novel cross-national lens to investigate how financial context moderates sustainability behavior.

While cross-national studies have explored environmental attitudes (Dunlap & York, 2008; Franzen & Meyer, 2010), relatively few have focused specifically on how generational cohorts, such as Millennials, navigate the intersection of financial and environmental pressures within diverse economic and cultural contexts. The aim of the present research is to investigate the relationship between financial stability and environmental sentiment among Millennials in Greece and the Netherlands, exploring how economic conditions and cultural differences shape environmental attitudes. By selecting Greece and the Netherlands, this study ensures a clear comparative framework that highlights the role of economic security, cultural values, and policy effectiveness in shaping Millennials’ engagement with environmental issues.

To sum up, by focusing on this demographic cohort, the study may provide insights that are crucial for policymakers and organizations aiming to promote sustainability among younger generations. Moreover, by comparing two countries with contrasting economic trajectories and welfare regimes, this research offers original insights into how financial security influences the value–action gap in sustainability. In doing so, it contributes to a deeper understanding of whether and how environmentalism functions as a “luxury good” for younger generations—a question with important implications for designing targeted, context-sensitive sustainability policies.

Integrating the concepts of financial stability and environmental sentiment within the Millennial demographic offers a unique lens through which to examine sustainable behaviors. The relationship between financial security and environmental engagement is particularly pertinent given the economic challenges faced by Millennials, such as higher rates of unemployment and economic instability than previous generations (Battiston et al., 2021; Ozili & Iorember, 2024). Research has yet to fully explore how these economic challenges intersect with cultural differences to influence the environmental sentiments and behaviors of Millennials in diverse settings such as Greece and the Netherlands.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Financial Stability and Environmental Behavior

While existing research has explored the effects of income or education on environmental attitudes, few studies have directly compared how perceived financial stability affects environmental sentiment within the same generational cohort in differing cultural–economic contexts. This study addresses that gap.

Recent research increasingly acknowledges the significant influence of financial stability on environmental behaviors, proposing that economic security may enable individuals to engage more actively in sustainable practices. Vicente-Molina et al. (2018) argue that financial stability provides not only the resources but also the psychological capacity necessary for individuals to commit to environmentally friendly actions. Their work suggests that when individuals are financially secure, they are more capable of focusing on long-term goals, such as sustainability, rather than being preoccupied with immediate economic concerns. This psychological bandwidth theory is further supported by behavioral economics, where decision-making is seen as constrained by financial insecurity, leading individuals to focus on short-term survival rather than future-oriented sustainability.

Corroborating this, studies by Mostafa (2009) and Gatersleben et al. (2002) highlight a positive correlation between higher income levels and increased environmental concern, suggesting that financial well-being empowers individuals to prioritize and act upon environmental issues. Mostafa (2009) found that wealthier individuals are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviors, such as recycling or purchasing eco-friendly products, because their financial resources allow them to absorb the potential cost premiums associated with these behaviors. Similarly, Gatersleben et al. (2002) observed that financial stability enables greater access to green technologies and sustainable choices, which might be economically out of reach for lower-income groups.

Nonetheless, Kasser (2009) emphasizes that this relationship is nuanced, mediated by personal values, education, and cultural contexts, indicating that financial stability’s impact on environmental behaviors extends beyond mere economic capability. Kasser’s findings suggest that even in financially stable contexts, environmental engagement is strongly influenced by intrinsic values such as a desire for community well-being and environmental stewardship. This underscores the importance of educational and cultural factors in shaping how individuals perceive and act upon environmental issues, even when they have the financial means to do so.

Further investigation into the underpinnings of this relationship reveals that in more affluent societies, where basic material needs are less of a concern, there tends to be a shift towards higher-order values such as altruism and sustainability, known as the “post-materialist thesis” (Inglehart, 1995). This shift is particularly pronounced in Northern and Western European countries, where material security fosters stronger environmental values and behaviors (Franzen & Vogl, 2013). This theory posits that as economic security increases, individuals begin to prioritize non-materialist concerns, such as environmental preservation and social justice. This shift towards post-materialist values in wealthier societies has been empirically supported by studies showing that populations in economically stable countries tend to exhibit stronger environmental behaviors and attitudes (Brechin, 2003; Franzen & Vogl, 2013).

At the same time, Ecological Modernization Theory provides an additional explanatory framework, suggesting that economic development and environmental protection are not mutually exclusive but can evolve together through technological innovation, institutional reform, and market-driven environmental solutions (Milanez & Bührs, 2007; Mol & Sonnenfeld, 2000; Mol et al., 2013). In this view, wealthier societies have both the capacity and institutional infrastructure to decouple environmental degradation from economic growth. This premise is increasingly observed in Northern European contexts (Hariram et al., 2023; Ntanos et al., 2018b; Zhang et al., 2024).

Comparative analyses also reveal notable differences between Northern and Southern Europe in terms of environmental attitudes and institutional trust. The research shows that environmental concern tends to be higher in Northern European countries, where environmental governance is stronger and public trust in institutions is more robust, while Southern European countries like Greece exhibit comparatively lower environmental engagement, often linked to economic instability, political fragmentation, and weaker policy implementation mechanisms (Hadler & Haller, 2011; Leonidou et al., 2022; Nawrotzki, 2012; Ntanos et al., 2018a).

Additionally, the role of education and access to information emerges as a critical factor in this dynamic. Wealthier economies not only offer financial stability but also provide better access to environmental education and knowledge resources, which, in turn, foster greater awareness and concern for sustainability issues (Lampropoulos et al., 2024; Qadri et al., 2025).

On the other hand, developing countries are actively working to raise awareness about sustainability, despite facing economic and regulatory challenges. Initiatives such as youth-led environmental programs and grassroots organizations are promoting climate action and sustainable practices (Moyeen & West, 2014). However, these efforts often involve trade-offs. Governments may hesitate to implement strict environmental regulations due to potential legal disputes with foreign investors, and economic pressures sometimes force compromises, such as reopening protected areas for commercial activities (Akhtar et al., 2024). These challenges highlight the delicate balance between sustainability and economic development, as nations strive to prioritize environmental goals while ensuring financial stability.

This complex interplay between financial stability, education, and access to information suggests that while financial well-being may lay the foundation for environmental behaviors, informational resources and cultural values play an equally significant role in guiding how individuals navigate sustainability challenges. This perspective supports a multidimensional approach to understanding the relationship between financial stability and environmental behavior, acknowledging that economic resources alone are insufficient without the cultural and educational frameworks that encourage sustainable action.

The role of economic disparities is crucial in understanding environmental behaviors, as financial inequality can exacerbate the differences in environmental engagement. In regions with pronounced income disparities, environmental degradation and its associated burdens disproportionately affect the economically disadvantaged, adding an ethical dimension to the discourse on financial stability and environmental behavior (Martinez-Alier, 2002). Such dynamics are particularly relevant in heterogeneous societies like Greece and the Netherlands, where regional economic variations could affect the uniformity and efficacy of environmental initiatives.

These theoretical frameworks and empirical insights set the stage for a deeper investigation into how financial stability may shape environmental sentiment in varied cultural and economic contexts. By examining Millennials in Greece and the Netherlands, this study tests whether these global trends hold in two distinct European environments.

2.2. Environmental Sentiment Among Millennials

As pointed out in the paper’s introduction, Millennials are widely recognized for their pronounced focus on sustainability, distinguishing them from previous generations. This cohort exhibits heightened environmental awareness and a preference for sustainable lifestyles, shaped by global connectivity and easy access to information on environmental issues (Lee et al., 2016). Growing up in an era marked by visible environmental crises, such as climate change and pollution, and amplified by digital media, Millennials have developed a strong affinity for environmental activism and advocacy. They are more likely to support brands and companies that align with their environmental values and prioritize ethical consumption, seeking out sustainable products and practices in their personal lives.

However, as Sogari et al. (2017) noted, the degree of environmental engagement among Millennials can vary significantly, influenced by socio-economic factors such as financial stability and access to education. Financial constraints can limit the extent to which Millennials can adopt sustainable practices, particularly when eco-friendly options are more expensive. Moreover, educational opportunities play a critical role in shaping their environmental sentiment, with more informed individuals generally exhibiting stronger environmental concern and action.

This variability highlights the need for a nuanced understanding of how Millennials from diverse economic conditions perceive and engage with environmental issues. While many Millennials are leading the sustainability movement and advocating for systemic change, others may be constrained by socio-economic challenges, resulting in differing levels of environmental engagement. Despite these challenges, Millennials remain a pivotal demographic in the global push toward sustainability, leveraging their collective power to demand stronger policies and greater corporate accountability. Their environmental sentiment, though shaped by individual circumstances, underscores a generational shift towards more sustainable and responsible living.

2.3. Cultural Differences in Environmental Attitudes

Cultural values significantly shape environmental perceptions and the readiness to engage in sustainable behaviors, as demonstrated in comparative studies across economically diverse countries (Price et al., 2014; Uzzell et al., 2002; Zeng et al., 2020). In the specific contexts of Greece and the Netherlands, distinct cultural attributes underpin different environmental strategies and attitudes. The Dutch culture, which values long-term orientation and indulgence, tends to be receptive to progressive environmental policies, as evidenced by their robust sustainability education and green technological advancements. Conversely, Greece’s higher power distance and strong uncertainty avoidance may lead to skepticism towards new environmental policies or technologies, favoring more traditional and immediate environmental solutions (Keaney, 1999; Skordoulis et al., 2020).

These cultural variations are further embedded within broader regional patterns across Europe. Eurobarometer surveys consistently show that citizens in Northern European countries (e.g., the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany) are more likely to support and engage in environmental actions compared to those in Southern Europe (e.g., Greece, Italy, Spain), where economic challenges often limit both individual and institutional capacity for sustainable behavior (European Commission, 2024). This north–south divide in environmental sentiment has been linked to both cultural value systems and disparities in public environmental investments and infrastructure (Marquart-Pyatt, 2012; Pampel & Hunter, 2012).

By situating the study of Millennials within these contrasting contexts, the current research is uniquely positioned to explore how economic and cultural differences shape the relationship between financial stability and environmental attitudes in Europe. This aligns with calls for more generationally and culturally nuanced environmental research (Fornara et al., 2016; Gatersleben & Vlek, 1998; Poortinga et al., 2004), especially in the face of intensifying climate challenges and uneven socio-economic recovery across EU member states.

Sustainable development is increasingly challenged by the interplay of social and economic crises, necessitating innovative strategies to balance progress with resilience. The 2024 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Report highlights that global progress on key SDGs remains uneven, with setbacks attributed to lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, intensifying climate crises, and economic instability. Urgent actions, such as scaled-up investments of USD 500 billion annually in sustainable projects, are deemed critical to reversing these trends and achieving the 2030 agenda.

Economic disparities are a significant obstacle. While high-income nations, such as Nordic countries, lead in SDG performance, others lag due to limited resources, conflicts, and financial constraints. Strengthening multilateral cooperation and creating long-term, inclusive policies are vital to fostering both economic growth and social equity globally.

These findings underscore the necessity for integrated approaches to sustainable development, emphasizing investments in green energy, equitable economic policies, and robust social safety nets to navigate these intertwined challenges effectively.

This underscores the importance of exploring whether these generational patterns persist across different economic and cultural systems, such as between Greek and Dutch Millennials, which is a central aim of the present study.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a quantitative research methodology to investigate the influence of perceived financial stability on environmental sentiment among Greek and Dutch Millennials. The research was conducted between 1 November and 31 December 2023, encompassing a total of 432 participants, with 426 providing usable data for the final analysis. The six non-adequate responses were excluded. The sample was evenly distributed between the two countries, with 210 participants from Greece and 216 from the Netherlands.

To qualify for inclusion, participants had to be Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) and have permanently resided in their respective countries for at least the last five years, ensuring cultural and economic relevance (Skordoulis et al., 2023). To ensure that participants were Millennials, multiple verification measures were implemented. First, participants were required to provide their birth year at the beginning of the questionnaire, with automated validation restricting responses outside the 1981–1996 range. Additionally, to minimize potential misreporting, respondents were asked to confirm their age in the demographics section. Any inconsistencies were flagged and reviewed before data inclusion.

The demographics revealed a nearly even split with 52% participants from Greece and 48% from the Netherlands (Figure 1). The gender distribution included 45% males, 54% females, and 1% identifying as other (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Country of origin.

Figure 2.

Gender.

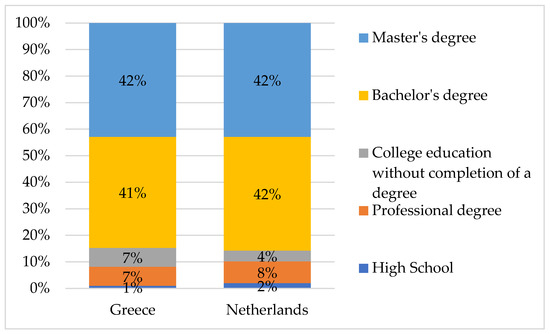

The participants’ education level ranged from high school diplomas to master’s degrees, with the majority holding a bachelor’s degree. The sample also varied across different income levels, potentially influencing responses on financial stability and environmental sentiment.

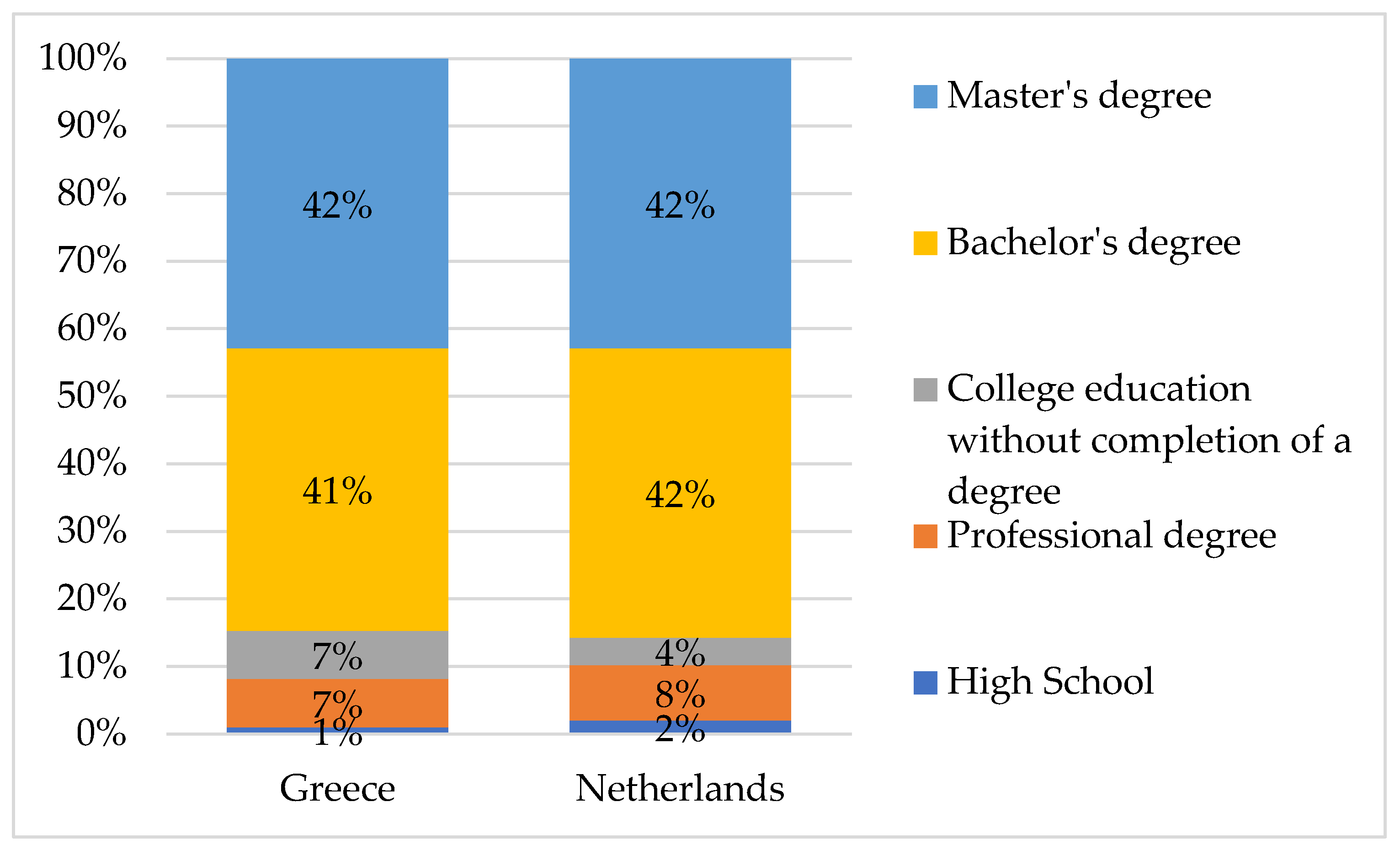

Figure 3 offers a comparative analysis of the educational levels between Greece and the Netherlands, displaying the distributions as percentages of the total educational attainment in each country.

Figure 3.

Educational level.

More specifically, the data show a relatively uniform distribution across different educational levels in both countries, with a few notable differences. A significant portion of the educational attainment in both countries is at the bachelor’s degree level, with the Netherlands exhibiting a slightly higher percentage than Greece. Furthermore, the Netherlands has a substantially higher proportion of individuals with master’s degrees, indicating a stronger emphasis on or access to graduate education. On the other hand, Greece shows a marginally higher representation of individuals with education at the high school level and below, which may reflect differences in the educational or economic structures affecting educational outcomes. Both countries have comparable, albeit small, proportions of individuals with professional degrees and some college education without completion of a degree.

A structured questionnaire, developed specifically for this study and informed by well-established precedents in the field, served as the primary research tool. This questionnaire integrated both the multidimensional construct of financial stability and the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) scale to assess environmental attitudes. The financial stability component included 10 statements covering various dimensions relevant to an individual’s financial situation, which participants rated on a 7-point Likert scale.

The questionnaire was distributed online using Microsoft Forms, ensuring convenience for participants. Recruitment was conducted via email invitations and shared on social media platforms targeting Millennial groups, including professional networks and university alumni associations in both countries. Snowball sampling was also employed, allowing participants to invite peers to complete the survey, which enhanced the sample’s diversity. Pre-testing with a smaller group helped refine the survey for clarity and reliability, ensuring high-quality data collection.

For the independent variable (financial stability), the purpose was to create a single variable that can effectively capture the multidimensional nature of financial stability. Participants were given 10 statements related to various dimensions of financial stability, such as income, savings, and debt, to rate in terms of a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree). More specifically, questions included assessments of participants’ financial well-being, such as their satisfaction with their current financial situation, sense of control over their financial future, and clarity in understanding monthly expenses. Additional measures examined their ability to manage financial risks, including having sufficient emergency savings, comfort with debt levels, regular saving habits, confidence in retirement planning, satisfaction with investment portfolios, and their perceived ability to handle financial setbacks.

A unified variable was created by merging the averaged responses for all participants from each of these 10 statements into a single numeric variable using the “Compute Variable” option in SPSS (v.26). Once the financial stability variable was created, descriptive statistics were reported on this variable, including percentage values for positive, neutral, and negative responses.

Similarly, the NEP scale, comprising 15 statements, gauged participants’ environmental concerns across several categories (Ntanos et al., 2019). More specifically, the NEP scale includes questions to assess respondents’ environmental attitudes based on dimensions such as beliefs about the fragility of nature’s balance, the limits to growth, and the potential for ecological catastrophe due to human activity. The NEP scale includes questions that are used to evaluate statements reflecting anthropocentric versus ecocentric worldviews, such as whether humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs, whether nature is resilient enough to recover from human intervention, and whether technological advancements can resolve environmental issues. Furthermore, the NEP scale assesses respondents’ views on human dependence on nature, the interconnectedness of ecosystems, and the urgency of environmental action, helping to gauge the extent to which they recognize environmental problems as pressing concerns requiring immediate intervention.

It is a fact that the NEP scale is widely used with adaptations. However, in the present study, the most recent approach of Dunlap (2008) was adopted. For the case of Greece, the referred approach was already successfully used in previous research (Diakakis et al., 2021; Ntanos et al., 2019). Furthermore, to ensure the NEP scale was appropriately tailored for the case of the Netherlands, a rigorous translation and back-translation process was undertaken. Initially, the NEP statements were translated from English into Dutch. An independent bilingual expert, unfamiliar with the original version, then back-translated the items into English. Discrepancies were reviewed and resolved by both translators and the research team to ensure semantic and conceptual equivalence. While this approach ensured linguistic accuracy and cultural relevance, a formal test of cross-cultural measurement invariance was not conducted. This limitation was addressed in the Discussion Section, and future research is encouraged to assess structural equivalence across cultural contexts. This limitation is discussed in the relevant section.

The study set a level of significance at 5%, using a multiple linear regression model to determine the relationship between financial stability and environmental sentiment. Additional statistical tests, including the Mann–Whitney U test, were employed to compare responses between the two national groups, ensuring that non-response error was minimal, as confirmed by tests conducted between the first and the last 30 questionnaires.

The design of the methodology was rigorously structured to avoid potential biases and ensure the reliability of the data. Reliability testing using Cronbach’s alpha was conducted; the results provided in Table 1 show a high internal consistency in both the total sample and the samples from Greece and the Netherlands separately.

Table 1.

Cronbach’s alpha values for the components of the questionnaires’ sections.

The robustness of the research methodology ensures that the findings are supported by empirical evidence, allowing for a reliable analysis of how financial stability influences environmental attitudes among Millennials in Greece and the Netherlands. This approach not only highlights the interconnections between economic and environmental domains but also underpins the study’s contribution to understanding the broader implications of financial security on sustainable behaviors.

4. Results

4.1. The Relationship Between Financial Stability and Environmental Sentiment

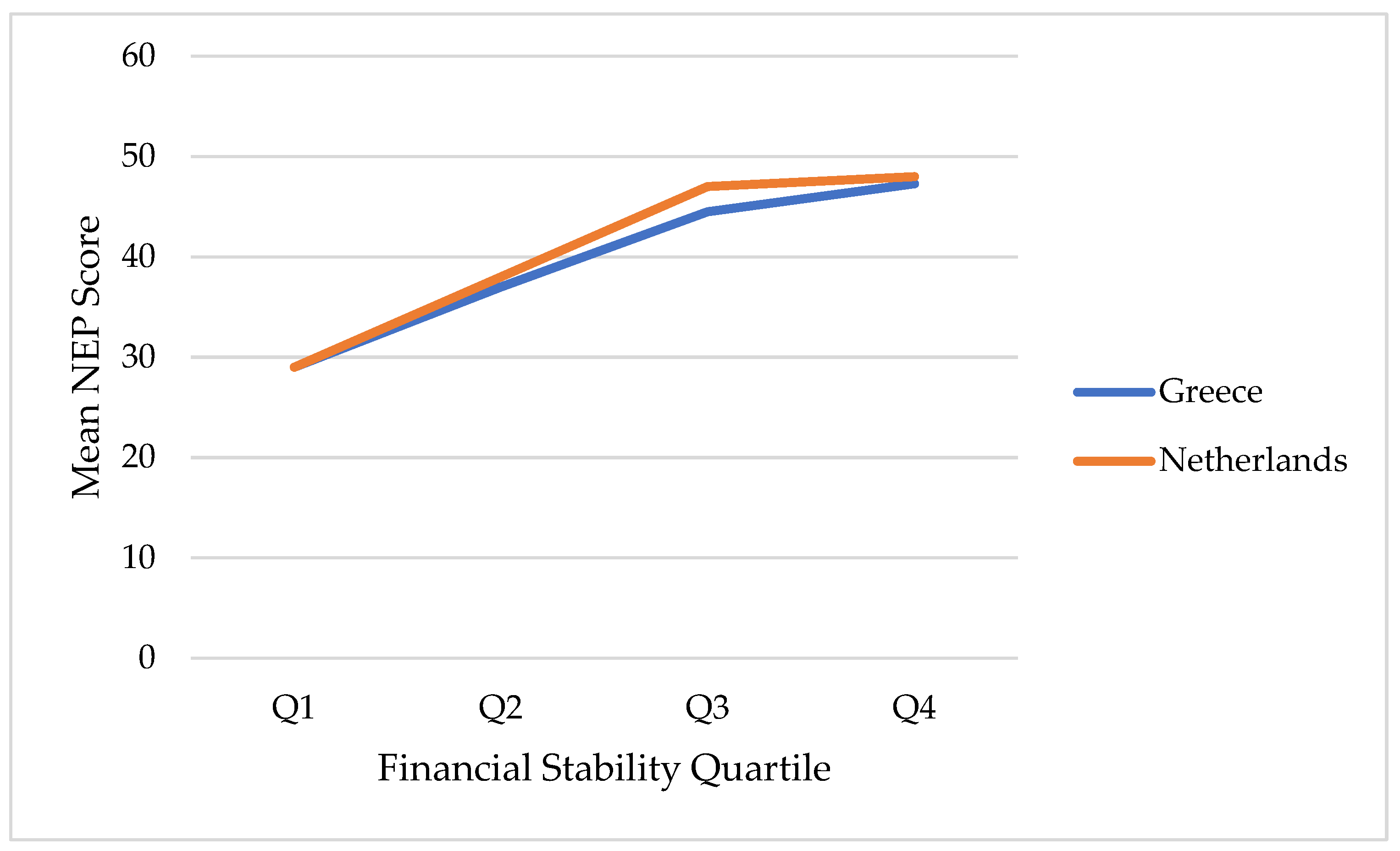

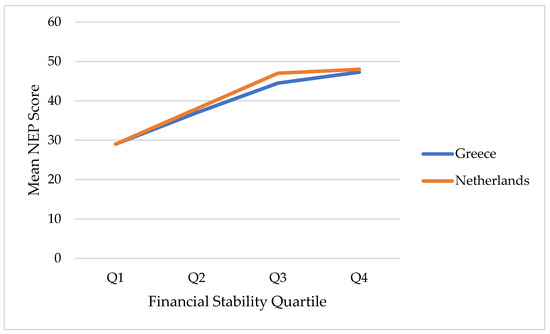

Participants’ financial stability was analyzed using a questionnaire that explored various dimensions such as satisfaction with current financial conditions, control over financial futures, and preparedness for unforeseen expenses. Responses were categorized into quartiles to delineate the relationship between financial stability and environmental sentiment. The NEP scale was used to measure environmental sentiment, where a direct correlation was found between higher financial stability and greater environmental concern. The mean NEP score was higher in the Netherlands (5.57) compared to Greece (4.12), pointing to a more pronounced environmental concern in the sample from the Netherlands. Moreover, the analysis showed that higher quartiles, which represent greater financial stability, consistently reported higher NEP scores, indicative of stronger environmental sentiments.

More specifically, as provided in Figure 4, participants from the Netherlands in the highest financial stability quartile (Q4) scored a mean NEP of 48.0, compared to their Greek counterparts who scored 47.3 in the same quartile. The lowest quartiles in both countries, Q1, scored 26.0 in Greece and 29.0 in the Netherlands, showing a clear trend where increased financial stability correlates with enhanced environmental concern.

Figure 4.

NEP scores by financial stability quartiles in Greece and the Netherlands.

A detailed correlation analysis was conducted to explore the relationship between financial stability and environmental sentiment among Greek and Dutch Millennials. The analysis employed a multiple linear regression model where the dependent variable was the score on the NEP scale, indicating environmental sentiment, and the independent variables included the financial stability score and country of origin. The regression results provided in Table 2 revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between financial stability and environmental sentiment, as indicated. The model estimated that an increase in financial stability is associated with an increase in the NEP scale score, suggesting that individuals who perceive themselves as financially stable are more likely to exhibit stronger pro-environmental attitudes. Additionally, being from the Netherlands was associated with a higher environmental sentiment score.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression model for relationship between financial stability and environmental sentiment.

The model’s adjusted R-squared value of 0.437 indicates that approximately 43.7% of the variability in environmental sentiment can be explained by the combined effects of financial stability and country. Last, the Durbin–Watson statistic of 1.821 suggests that there is no significant autocorrelation in the residuals of the regression model, supporting the validity of the model results.

The above findings align with the hypothesis that financial stability is positively correlated with environmental sentiment. This relationship underscores the importance of economic security in fostering environmental consciousness, highlighting how financial resources can enable individuals to engage more actively in sustainable practices. The analysis provides robust evidence supporting the need for policies that enhance financial stability as a strategy to promote environmental sustainability, especially among younger populations in diverse economic contexts.

4.2. Cultural Differences in Financial Stability and Cultural Impact on Financial Perceptions and Behaviors

The values depicted in Table 3 highlight several areas where financial stability differs significantly between Greek and Dutch Millennials, suggesting that economic and cultural contexts influence these differences. Notably, the Dutch respondents scored higher in satisfaction with their current financial situation, having enough emergency savings to cover unexpected expenses, regularly saving a portion of their income, and confidence in their ability to plan for retirement.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of financial stability indicators among Greek and Dutch Millennials: Mann–Whitney U test results.

These differences likely reflect broader economic stability and financial management practices that are culturally ingrained within each country. The Dutch economy is generally more robust than the Greek economy, which has undergone significant stress, especially post-2008 financial crisis. These economic conditions contribute to a higher sense of financial security among Dutch Millennials.

The financial stability components where the Dutch respondents report higher levels may also correlate with higher environmental concerns. This suggests that environmental quality is considered a luxury that those in more stable financial conditions can afford to prioritize. As such, these economic capabilities might enable Dutch Millennials to engage more actively in environmental conservation efforts and sustainable practices, leveraging their financial security towards supporting or investing in environmental sustainability.

4.3. Demographics and Financial Stability Components

To further enrich our understanding of the relationship between financial stability and environmental sentiment, we extended our analysis to explore subgroup dynamics and the underlying components of financial well-being. Specifically, we examined how NEP scores vary across financial quartiles, identified which elements of financial stability most strongly predict environmental concern, and assessed the influence of education and gender on these relationships.

Initially, referring to NEP score differences by financial stability quartiles, participants in the lowest financial stability quartile (Q1) had an average NEP score of 28.6 (St. Dev. = 5.1), while those in the highest quartile (Q4) scored 47.8 (St. Dev. = 4.3), as provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

NEP scores by financial stability quartile.

An ANOVA test (Table 5) was carried out and confirmed that these differences were statistically significant (sig. = 0.000), with a large effect size (R2 = 0.371), suggesting that over one-third of the variance in environmental sentiment can be attributed to financial stability levels.

Table 5.

ANOVA test results.

To gain insight into which aspects of financial stability are most influential, we performed a stepwise multiple regression using the individual financial stability indicators as predictors of NEP scores. This was intended to isolate the specific financial dimensions that might enable pro-environmental behavior beyond the aggregated financial stability score. The results provided in Table 6 reveal that the most influential predictors are enough emergency savings to cover unexpected expenses (β = 0.31, p = 0.001), regularly save a portion of income (β = 0.27, p = 0.004), and feel confident in the ability to plan for retirement (β = 0.24, p = 0.009). Other dimensions such as comfort with debt and monthly expense understanding did not significantly predict environmental sentiment. The final model explained 39% of the variance in NEP scores (adjusted R2 = 0.39).

Table 6.

Stepwise regression model for financial stability components.

To assess multicollinearity among predictors in the stepwise regression model, we examined the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and tolerance values. All VIF values were below 1.5, and all tolerance values exceeded 0.70, indicating low multicollinearity and acceptable independence among the included financial stability components.

Finally, to examine how demographic characteristics might influence environmental sentiment, a model multiple linear regression that included gender and education level was developed. This was motivated by previous literature indicating that demographic variables may shape attitudes toward sustainability and financial behavior. In the present analysis, education level was coded in ascending order (e.g., high school = 1, professional degree = 2, college education = 3, bachelor’s degree = 4, master’s degree = 5), and gender was coded similarly (male = 1, female = 2, other = 3). This allowed us to preserve ordinal structure while maintaining model parsimony. The results provided in Table 7 reveal that education level is as a significant positive predictor (β = 0.161, p = 0.008), while gender does not have a statistically significant impact (β = 0.068, p = 0.191).

Table 7.

Multiple linear regression model for relationship between demographics and environmental sentiment.

As in the previous model, VIF and tolerance values were examined. All VIF values were below 1.5, and all tolerance values exceeded 0.70; these results indicated low multicollinearity and acceptable independence among the included variables.

These above analyses offer more nuanced insights into the financial stability and environmental sentiment relationship. Notably, specific components of financial stability (emergency savings, consistent saving behavior, and confidence in retirement planning) were the strongest predictors of environmental sentiment. This suggests that individuals who perceive long-term control and preparedness over their financial lives are more inclined to engage with sustainability issues.

Additionally, education level emerged as a positive predictor of pro-environmental attitudes, which is consistent with prior research. This reinforces the idea that both financial literacy and educational attainment may enhance environmental awareness. Gender, while modeled as an ordinal variable, did not significantly influence NEP scores, suggesting limited differentiation in environmental sentiment across gender identities within this sample.

Lastly, the substantial difference in NEP scores between the lowest and highest financial stability quartiles underscores the strength of the relationship and supports the broader framing of environmentalism as influenced by economic capacity.

5. Discussion

This study highlights the complex relationship between financial stability and environmental sentiment among Greek and Dutch Millennials, contributing to the broader discourse on how economic conditions correlate with environmental attitudes. The quantitative analysis shows that perceived financial stability significantly enhances environmental concern, supporting prior research that identifies financial security as a key driver of environmental engagement (Gatersleben et al., 2002; Schaefer et al., 2020).

Dutch Millennials exhibit stronger environmental sentiment than Greeks, reflecting the Netherlands’ more stable economic environment. This aligns with the “luxury good hypothesis”, which suggests environmental quality becomes a higher priority in financially secure contexts. Financial stability enables individuals to invest in cleaner technologies and sustainable practices (Lambert et al., 2023). Dutch participants reported higher satisfaction with their financial situation and emergency savings, likely translating into a higher capacity and willingness to prioritize environmental concerns.

These findings are consistent with recent studies showing that financial stability creates a buffer that allows individuals to focus on long-term global issues like environmental sustainability, rather than being preoccupied with short-term economic survival (Ozili & Iorember, 2024). This dynamic is evident in the correlation analysis, where financial stability positively impacts environmental sentiment, especially in a financially stable cohort like the Dutch. This supports the view that socio-economic stability encourages individuals to engage in pro-environmental behaviors by reducing existential threats, thereby fostering a greater focus on sustainable practices (Griskevicius et al., 2010).

Furthermore, the significance of country of origin as a predictor reinforces the influence of national context on sustainability attitudes. The consistently higher NEP scores among Dutch participants may reflect more deeply embedded ecological norms, as well as stronger institutional support for environmental initiatives. This supports the theoretical framing of environmental quality as a “post-materialist” concern, more easily prioritized in stable economic settings.

Moreover, the cultural and economic context in the Netherlands, which is characterized by higher incomes and access to financial services, appears to support both financial and environmental planning. These conditions likely contribute to the heightened environmental awareness observed among Dutch Millennials.

In contrast, Greece’s economic challenges may limit Millennials’ ability to prioritize environmental issues, as immediate financial concerns take precedence (Kasser, 2009). This highlights how economic hardship can shift focus away from environmental sustainability.

In summary, this study underscores the importance of economic security in fostering environmental consciousness and suggests that enhancing financial stability may serve as a strategic lever to promote environmental sustainability (Arabatzis & Myronidis, 2011; Malesios & Arabatzis, 2010). Policymakers and stakeholders should consider these dynamics in designing interventions aimed at improving financial literacy and stability to facilitate greater environmental engagement, especially among younger populations in diverse economic contexts.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Managerial Implications

This study underscores the critical role of financial stability in shaping environmental consciousness, particularly among younger generations navigating diverse economic conditions. The relationship between economic security and environmental sentiment reflects the broader challenges and opportunities embedded within sustainable practices amid ongoing social and economic complexities. For Millennials, financial stability serves not only as a foundation for personal well-being but also as a catalyst for long-term commitment to sustainability.

The disparity between Greek and Dutch Millennials highlights how national economic contexts influence sustainability engagement. The Netherlands’ strong financial environment supports proactive environmental attitudes, as is consistent with the “luxury good hypothesis”, which posits that sustainability becomes a priority in stable economic conditions (Lambert et al., 2023). In contrast, economic precarity in Greece reinforces short-term survival concerns, limiting focus on global challenges like environmental sustainability. These findings contribute to broader discussions advocating for inclusive financial systems, culturally sensitive approaches, and targeted support for economically vulnerable populations gap (Gupta & Vegelin, 2016).

To address the intertwined challenges of economic security and environmental sustainability, policymakers and stakeholders should pursue integrated strategies that promote financial stability and environmental awareness. Investments in education, access to financial services, and economic resilience are essential to empowering individuals and communities to participate in sustainable development. Joint initiatives that foster both economic empowerment and ecological responsibility can amplify the impact. Strengthening individuals’ sense of financial control may also enhance their engagement with environmental issues (Ntanos et al., 2020).

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study offers valuable insights into the relationship between financial stability and environmental sentiment among Millennials in Greece and the Netherlands, several limitations should be noted. First, the reliance on self-reported survey data may introduce social desirability bias, as participants might overstate their environmental concern or financial stability to align with perceived societal expectations. Future research could incorporate behavioral measures or financial records to validate these responses.

Another methodological concern is common method variance, as both independent and dependent variables were collected through self-reports at a single time point. Although procedural measures such as anonymity and randomized item ordering were used, statistical controls (e.g., Harman’s single-factor test) were not applied. Future studies could consider these techniques to better assess and address potential bias.

Cultural and policy differences between Greece and the Netherlands may also influence environmental sentiment beyond financial stability. Differences in government sustainability initiatives, environmental education, and cultural views on financial security could have shaped responses. Future research should consider additional control variables, such as political ideology, policy exposure, and access to green infrastructure, to refine the analysis.

Moreover, the cross-sectional design captures financial stability and environmental sentiment at one point in time, limiting insight into how these perceptions change. A longitudinal approach would better track how shifts in economic conditions and policy environments influence this relationship over time.

Although the same financial stability scale was administered in both countries, it is possible that the construct of financial stability may be interpreted differently depending on the national economic and cultural context. While the 10-item scale covered key dimensions such as income, savings, debt comfort, and future planning, it is a fact that societal expectations and financial norms vary between Greece and the Netherlands. To ensure internal consistency within each sample, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated separately, resulting in high reliability scores (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.812 for Greece; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.816 for the Netherlands). However, the present study did not include formal measurement invariance testing. Future research could apply multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine whether the construct demonstrates configural, metric, and scalar equivalence, ensuring that cross-cultural comparisons are based on structurally similar interpretations of financial stability.

Another limitation concerns the sampling strategy, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. While the sample size was adequate and achieved a balanced distribution across gender and nationality, the online recruitment approach through snowball sampling likely resulted in an overrepresentation of digitally connected and highly educated employed Millennials. As our demographic data suggest, a significant proportion of respondents hold bachelor’s or master’s degrees. These socio-economic characteristics are known to be associated with both greater perceived financial security and stronger pro-environmental attitudes (Franzen & Vogl, 2013; Pampel & Hunter, 2012). As such, the results may reflect the perspectives of a relatively privileged segment of the Millennial population, potentially underrepresenting the views of individuals from lower-income, rural, or less formally educated backgrounds. Future studies could address this limitation through stratified sampling techniques or quota-based recruitment, ensuring more representative coverage of diverse socio-economic profiles.

The study’s focus on Millennials limits its applicability to other generational cohorts. While Millennials are central to sustainability discourse, future research could include Generation Z and older groups to determine whether these trends persist across age groups.

Finally, while NEP remains a valuable benchmark, future research should consider multidimensional measures that capture both environmental attitudes and behaviors. Examining how financial precarity or intergenerational wealth influences engagement with sustainability efforts would offer a more nuanced understanding of financial stability and environmental sentiment relationship.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and A.Z.; methodology, M.S. and A.Z.; software, M.S.; validation, A.K., A.-S.S. and P.K.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, A.Z.; resources, A.Z.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S., A.Z. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.-S.S. and P.K.; visualization, A.-S.S. and P.K.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was approved in accordance with the regulations of the Department of Business Administration at the University of West Attica. The specific approval details are maintained by the department. Ethical oversight was provided by the department’s internal convention, which adheres to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akhtar, S., Tian, H., Iqbal, S., & Hussain, R. Y. (2024). Environmental regulations and government support drive green innovation performance: Role of competitive pressure and digital transformation. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 26(12), 4433–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabatzis, G., & Myronidis, D. (2011). Contribution of SHP Stations to the development of an area and their social acceptance. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 15(8), 3909–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiston, S., Dafermos, Y., & Monasterolo, I. (2021). Climate risks and financial stability. Journal of Financial Stability, 54, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechin, S. R. (2003). Comparative public opinion and knowledge on global climatic change and the Kyoto Protocol: The US versus the world? International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 23(10), 106–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, C., & Lai, C. K. (2018). Explicit (but not implicit) environmentalist identity predicts pro-environmental behavior and policy preferences. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 58, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haas, W., Hassink, J., & Stuiver, M. (2021). The role of urban green space in promoting inclusion: Experiences from The Netherlands. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 9, 618198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. (2022). Gen Zs and millennials look to employers to address climate concerns. WSJ. Available online: https://deloitte.wsj.com/sustainable-business/gen-zs-and-millennials-look-to-employers-to-address-climate-concerns-c1cddbe8 (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Diakakis, M., Skordoulis, M., & Savvidou, E. (2021). The relationships between public risk perceptions of climate change, environmental sensitivity and experience of extreme weather-related disasters: Evidence from Greece. Water, 13(20), 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosos, D., Skordoulis, M., Arabatzis, G., Tsotsolas, N., & Galatsidas, S. (2019). Measuring industrial customer satisfaction: The case of the natural gas market in Greece. Sustainability, 11(7), 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R. E. (2008). The new environmental paradigm scale: From marginality to worldwide use. The Journal of Environmental Education, 40(1), 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R. E., & York, R. (2008). The globalization of environmental concern and the limits of the postmaterialist values explanation: Evidence from four multinational surveys. The Sociological Quarterly, 49(3), 529–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2024). Attitudes of Europeans towards the environment: Eurobarometer report. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Fornara, F., Pattitoni, P., Mura, M., & Strazzera, E. (2016). Predicting intention to improve household energy efficiency: The role of value-belief-norm theory, normative and informational influence, and specific attitude. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, A., & Meyer, R. (2010). Environmental attitudes in cross-national perspective: A multilevel analysis of the iSSP 1993 and 2000. European Sociological Review, 26(2), 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, A., & Vogl, D. (2013). Two decades of measuring environmental attitudes: A comparative analysis of 33 countries. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B., Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2002). Measurement and determinants of environmentally significant consumer behavior. Environment and Behavior, 34(3), 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B., & Vlek, C. (1998). Household consumption, quality of life, and environmental impacts: A psychological perspective and empirical study. In Green households. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R., & Nilsson, A. (2014). Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. International Journal of Psychology, 49(3), 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Román, C., Lima, M. L., Seoane, G., Alzate, M., Dono, M., & Sabucedo, J.-M. (2021). Testing common knowledge: Are northern europeans and millennials more concerned about the environment? Sustainability, 13(1), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., & Van den Bergh, B. (2010). Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(3), 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J., & Vegelin, C. (2016). Sustainable development goals and inclusive development. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16(3), 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadler, M., & Haller, M. (2011). Global activism and nationally driven recycling: The influence of world society and national contexts on public and private environmental behavior. International Sociology, 26(3), 315–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariram, N. P., Mekha, K. B., Suganthan, V., & Sudhakar, K. (2023). Sustainalism: An integrated socio-economic-environmental model to address sustainable development and sustainability. Sustainability, 15(13), 10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R., Ashfaq, M., & Shao, L. (2024). Evaluating drivers of fintech adoption in The Netherlands. Global Business Review, 25(6), 1576–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. (1995). Public support for environmental protection: Objective problems and subjective values in 43 societies. PS: Political Science & Politics, 28(1), 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T. (2009). Psychological need satisfaction, personal well-being, and ecological sustainability. Ecopsychology, 1(4), 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaney, M. (1999). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding cultural diversity in business. International Journal of Social Economics, 26(5), 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M. J. M., Jusoh, Z. M., Abd Rahim, H., & Zainudin, N. (2023). Exploring the determinants of financial well-being in the millennial generation: A systematic literature review (SLR). International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13(16), 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, I., Astara, O.-E., Skordoulis, M., Panagiotakopoulou, K., & Papagrigoriou, A. (2024). The contribution of education and ict knowledge in sustainable development perceptions: The case of higher education students in Greece. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies, 12(1), 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W. J. (Thomas), Cheah, I., Phau, I., Teah, M., & Elenein, B. A. (2016). Conceptualising consumer regiocentrism: Examining consumers’ willingness to buy products from their own region. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 32, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C. N., Gruber, V., & Schlegelmilch, B. B. (2022). Consumers’ environmental sustainability beliefs and activism: A cross-cultural examination. Journal of International Marketing, 30(4), 78–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesios, C., & Arabatzis, G. (2010). Small hydropower stations in Greece: The local people’s attitudes in a mountainous prefecture. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 14(9), 2492–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart-Pyatt, S. T. (2012). Contextual influences on environmental concerns cross-nationally: A multilevel investigation. Social Science Research, 41(5), 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alier, J. (2002). The environmentalism of the poor. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Milanez, B., & Bührs, T. (2007). Marrying strands of ecological modernisation: A proposed framework. Environmental Politics, 16(4), 565–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A. P. J., & Sonnenfeld, D. A. (2000). Ecological modernisation around the world: An introduction. Environmental Politics, 9(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A. P. J., Spaargaren, G., & Sonnenfeld, D. A. (2013). Ecological modernization theory: Taking stock, moving forward. In Routledge international handbook of social and environmental change. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, M. M. (2009). Shades of green: A psychographic segmentation of the green consumer in Kuwait using self-organizing maps. Expert Systems with Applications, 36(8), 11030–11038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyeen, A., & West, B. (2014). Promoting CSR to foster sustainable development: Attitudes and perceptions of managers in a developing country. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 6(2), 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrotzki, R. J. (2012). The politics of environmental concern: A cross-national analysis. Organization & Environment, 25(3), 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntanos, S., Asonitou, S., Kyriakopoulos, G., Skordoulis, M., Chalikias, M., & Arabatzis, G. (2020). Environmental sensitivity of business school students and their attitudes towards social and environmental accounting. In A. Kavoura, E. Kefallonitis, & P. Theodoridis (Eds.), Strategic innovative marketing and tourism (pp. 195–203). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ntanos, S., Kyriakopoulos, G., Chalikias, M., Arabatzis, G., Skordoulis, M., Galatsidas, S., & Drosos, D. (2018a). A social assessment of the usage of renewable energy sources and its contribution to life quality: The case of an attica urban area in Greece. Sustainability, 10(5), 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntanos, S., Kyriakopoulos, G., Skordoulis, M., Chalikias, M., & Arabatzis, G. (2019). An application of the new environmental paradigm (NEP) scale in a greek context. Energies, 12(2), 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntanos, S., Skordoulis, M., Kyriakopoulos, G., Arabatzis, G., Chalikias, M., Galatsidas, S., Batzios, A., & Katsarou, A. (2018b). Renewable energy and economic growth: Evidence from european countries. Sustainability, 10(8), 2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023a). Key policy insights (Vol. 2023). OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023b). OECD economic surveys: Greece 2023. OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-economic-surveys-greece-2023_c5f11cd5-en.html (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- OECD. (2025). The Netherlands—Countries & regions. IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/countries/the-netherlands/energy-mix (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Ozili, P. K., & Iorember, P. T. (2024). Financial stability and sustainable development. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 29(3), 2620–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampel, F. C., & Hunter, L. M. (2012). Cohort change, diffusion, and support for environmental spending in the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 118(2), 420–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W., Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2004). Values, environmental concern, and environmental behavior: A study into household energy use. Environment and Behavior, 36(1), 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J. C., Walker, I. A., & Boschetti, F. (2014). Measuring cultural values and beliefs about environment to identify their role in climate change responses. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 37, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadri, H. M. U. D., Zafar, M. B., Ali, H., & Tahir, M. (2025). Wealth, wisdom, and the will to protect: An examination of socioeconomic influences on environmental behavior|social indicators research. Social Indicators Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters. (2024). Renewables outweigh fossil fuels in Dutch power mix, statistics agency says. Reuters. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrasin, O., Crettaz von Roten, F., & Butera, F. (2022). Who’s to act? Perceptions of intergenerational obligation and pro-environmental behaviours among youth. Sustainability, 14(3), 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A., Williams, S., & Blundel, R. (2020). Individual values and SME environmental engagement. Business & Society, 59(4), 642–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M., Kaskouta, I., Chalikias, M., & Drosos, D. (2018). E-commerce and e-customer satisfaction during the economic crisis. Journal for International Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 11(1), 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M., Ntanos, S., & Arabatzis, G. (2020). Socioeconomic evaluation of green energy investments: Analyzing citizens’ willingness to invest in photovoltaics in Greece. International Journal of Energy Sector Management, 14(5), 871–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M., Panagiotakopoulou, K., Manolis, D., Papagrigoriou, A., & Kalantonis, P. (2023). Perceptions of environmental sustainability and luxury: Influences on organic food buying behavior among Millennials and Generation Z in Greece. Global NEST Journal, 26(5), 06067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M., Patsatzi, O., Kalogiannidis, S., Patitsa, C., & Papagrigoriou, A. (2024). Strategic management of multiculturalism for social sustainability in hospitality services: The case of hotels in athens. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(4), 977–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. T., & Brower, T. R. (2012). Longitudinal study of green marketing strategies that influence Millennials. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 20(6), 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G., Pucci, T., Aquilani, B., & Zanni, L. (2017). Millennial generation and environmental sustainability: The role of social media in the consumer purchasing behavior for wine. Sustainability, 9(10), 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L., Fang, S., Iqbal, S., & Bilal, A. R. (2022). Financial stability role on climate risks, and climate change mitigation: Implications for green economic recovery. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(22), 33063–33074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surmacz, T., Wierzbiński, B., Kuźniar, W., & Witek, L. (2024). Towards sustainable consumption: Generation Z’s views on ownership and access in the sharing economy. Energies, 17(14), 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, A., Kennedy, B., & Funk, C. (2021). Gen Z, Millennials stand out for climate change activism, social media engagement with issue. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/05/26/gen-z-millennials-stand-out-for-climate-change-activism-social-media-engagement-with-issue/ (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Uzzell, D., Pol, E., & Badenas, D. (2002). Place identification, social cohesion, and enviornmental sustainability. Environment and Behavior, 34(1), 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M. A., Fernández-Sainz, A., & Izagirre-Olaizola, J. (2018). Does gender make a difference in pro-environmental behavior? The case of the Basque Country University students. Journal of Cleaner Production, 176, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J., Jiang, M., & Yuan, M. (2020). Environmental risk perception, risk culture, and pro-environmental behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Waris, U., Qian, L., Irfan, M., & Rehman, M. A. (2024). Unleashing the dynamic linkages among natural resources, economic complexity, and sustainable economic growth: Evidence from G-20 countries. Sustainable Development, 32(4), 3736–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).