Abstract

This study, based on naturalistic discourse in Mano and on both morphosyntactic and prosodic characteristics, analyses the Mano constructions formed with the marker lɛ́, including the identifying construction, referent introduction, focus, relativization, and hanging topic. While the identifying construction can be treated as a separate predication, and lɛ́ within it as a predicator, in all the other constructions lɛ́ does not have a predicative function. For Mano lɛ́, we suggest an invariant function instead, that of attention shift. Depending on both the structural and the pragmatic grounds, attention shift can be interpreted as having a predicative or a non-predicative function. We finally suggest that mapping recurrent constructions on interactants’ actions requires no definition of the notion of “clausehood”: NP-based constructions can be deployed for performing a communicatively self-sufficient action of an attention shift. This would present them as “clausal” in a speech-act-based analysis, and non-clausal from the perspective that defines clauses as subject–predicate structures—but this question does not arise in our approach that links syntactic structures to communicative action. The analysis is nested in the approach to polysemy as a “family of constructions” and to information structure as diverse interpretive effects, rather than a closed set of discrete universal categories.

1. Introduction

The function of an NP in discourse and its marking are typically examined with respect to the role the NP plays in a larger, namely, clausal or sentential, structure. For example, case-marking signals the relationship of an NP to another constituent in the clause (e.g., Shcherbakova et al., 2024). Similarly, pragmatic marking is commonly regarded as signalling the contribution of the NP relative to the rest of the sentence, such as whether the information expressed by this NP has the topical or focal status on the propositional level (e.g., Nakagawa, 2020 for Japanese). In the same vein, the function of extra-clausal left- and right-detached NPs is analysed with respect to the adjacent clause (López, 2016).

On the structural level, NPs are usually analysed as part of a larger construction type at the level of a clause. For example, although structurally they have no role in it, a left- or right-detached NP and the clause adjacent to it are often regarded as jointly forming a sentence type or construction (e.g., Gregory & Michaelis, 2001). Similarly, a pragmatic marking is considered for its clause- or sentence-level contribution, even if the distribution of this marking is known to be driven by broader discourse factors. This is the case with the ‘as for’ construction in English, traditionally regarded as sententialtopic marking (after Reinhart, 1981) despite its higher-level function of signalling a discourse shift to an issue that forms a set with other previously addressed issues (Jaeger & Oshima, 2002). The same principle applies also for the analysis of the Japanese “topic-particle” -wa, whose distribution is driven by episode shifts in discourse (Shimojo, 2016).

When it comes to syntactically detached nominal constituents, an analysis in terms of a sentential structure becomes less straightforward. Some syntactic approaches assume the existence of an underlying sentential structure, regarding the phenomenon as ellipsis (see the discussion in Stainton, 2006). In other views, non-sentential structures are accepted for particular constructions dedicated to specific, often non-updating actions, such as nominal exclamatives (e.g., Zanuttini & Portner, 2005).

Interactional approaches instead explored various functions that detached NPs play as part of larger discourse, without assuming a sentential or otherwise specific structure. These functions include an introduction of referents or a maintenance of their active status, signalling their relevance for the subsequent discourse (Matsumoto, 1998, for Japanese), making assessments (Helasvuo, 2019, for Finnish), or providing updating information (Ono & Thompson, 1994, for English; Matsumoto, 1998, for Japanese). Moreover, interactional research shows that nominal constituents that do eventually evolve into sentential structures can nonetheless represent sub-sentential constructions with a consistent function. Speakers may employ them without foreseeing the entire upcoming structure and aiming merely at their local contribution. This is the case with foreshadowing, or “projecting” (in the interactional sense of Hopper & Thompson, 2008; Auer, 2015, among many others) constructions, which range from complex structures, such as pseudoclefts (“wh-clefts”, Maschler et al., 2023), to simpler NP-structures, such as the Hebrew ha’emet she, ‘the truth that’ (Polak-Yitzhaki, 2020).

Another case where NPs are reanalysed as constructions on their own with an independent sub-sentential contribution (instead of forming part of a larger structure) is left detachments. Interactional studies found a set of recurrent functions for NPs produced as a separate intonation unit, such as an attention shift to a referent or maintenance of joint attention on an activated referent. The functions are consistent irrespective of whether the NP has no structural continuation, evolves smoothly into a clause assuming the syntactic role of the subject, or is continued by a full clause rendering a left-detached configuration (Ozerov, 2025a, 2025b). In other words, left detachments are not constructions but collocations of two separate structures, namely, an NP and a clause, each of which has a separate contribution. Importantly, this analysis attributes a local function to the prosodically separate NP, irrespective of the question whether the continuation transforms it into an element of a coherent structure or not. In other words, detached items can have an independent sub-sentential function, with clauses and sentences potentially emerging when sub-clausal chunks are continued in subsequent talk.

While the current research has identified a substantial array of sub-sentential and sub-clausal constructions with consistent local discourse contributions, there is less evidence for dedicated morphological marking associated with sub-clausal functions. This study explores the adnominal marker lɛ́ in Mano, a Mande language spoken by about 400,000 people in Guinea and Liberia. Examined from the clause-based perspective, the marker appears to exhibit highly dissimilar grammatical and pragmatic functions: (a) a non-verbal predicator in a presentative construction; (b) a left-detached construction used for referent introduction; (c) a narrow, cleft-like (identificational) focus marker; (d) an adnominal marker in thetic, all-focus constructions; and (e) a relativiser. A similar range of functions has been observed for a cognate marker in a closely related language, Guro (Kuznetsova, 2023). We propose that at least for Mano, all these functions are by-products of its unified sub-clausal function: a pragmatic instruction for a required attention shift. For this reason, from here onwards we will gloss the marker as att. Depending on both the structural and the pragmatic context, attention shift can be interpreted as having a predicative or a non-predicative function, a topic-like or a focus-like interpretation, or appear in contexts of referent introductions and a preliminary profiling of a referent before an elaboration on its precise identity by a relative-like clause. As such, this paper contributes to the study of the grammar and functions of sub-clausal constituents and their dedicated marking, and the optional emergence of clausal constructions. It also contributes to the discussion of low transitivity, including non-verbal constructions as (a)typical clauses (see Mayes, 2024), by pushing the argument further and bringing into question the predicative nature of identifying constructions and of items that are traditionally described as non-verbal copulas or predicators. It demonstrates how NP-structures can have a consistent communicative contribution without having a typical clausal syntactic structure. The analysis is nested in the approach to polysemy as “family of constructions” (Hopper, 2001; Maschler & Pekarek Doehler, 2022, inter alia) and to information structure as diverse interpretive effects, rather than a closed set of discrete universal categories (Ozerov, 2021).

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents our materials and methods. Section 3 provides the empirical core of the argument: first, some necessary structural background (Section 3.1), followed by a description of the range of functions of constructions with lɛ́ (Section 3.2). We discuss the findings, propose an invariant function—that of attention shift—in Section 4 and conclude in Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

The paper is based on a collection of recordings of naturalistic, mostly monological, texts of various genres: traditional folktales, narrative retellings, church sermons, and spontaneous Bible translations. By default, the examples come from such a corpus. Most of the recordings are published or are soon to be published in online repositories, but some remain in the second author’s personal archive. Whenever token counts are made, the sources are properly referenced. Some examples come from experimental picture description tasks and are marked as [exper]. Elicited examples are marked as [el].

3. The Range of Functions of lɛ́

3.1. Structural Background

3.1.1. Background on Predication and Predicative Function of lɛ́

Mano has a rigid (S)–(Aux)–(O)–verb/non-verbal predicate–(X) word order (Nikitina, 2011). The auxiliary is an obligatory part of verbal and most non-verbal predications and indexes the subject’s person and number in addition to expressing tense, aspect, modality, and polarity (TAMP). Portmanteau auxiliaries in addition incorporate a third-person-singular pronoun, which typically, but not always, occupies the direct object position.

| (1) | mā | gèē | ī | lɛ̀ɛ̄ |

| 1sg.pst>3sg | say | 2sg | to | |

| ‘I said it to you.’ | ||||

Thus, in (1), mā is a first-person-singular auxiliary of the past series merged with a third-person-singular object pronoun. Depending on the TAMP construction, the verb may appear in one of the dedicated tonal forms. In constructions with auxiliaries, the subject NP is optional. X stands for all arguments besides the direct object, as well as for adjuncts; both are typically expressed by postpositional phrases, such as ī lɛ̀ɛ̄ ‘to you’.

Most affirmative non-verbal predications in Mano are organized around the predicate kɛ̄ ‘to be’, except of the present, where an existential auxiliary series is used. This can be seen in the non-verbal construction expressing referential identity in (2), where the subject NP, gɔ̰́ wɛ̄ ‘this man’, has the same referent as the predicate NP, ŋ̄ dɛ̰̄ ‘my husband’, introduced in the postpositional phrase with the postposition ká. Class-membership, possession, attribution, location, and existential constructions are also formed on the basis of kɛ̄ ‘to be’ and, in the present, the existential auxiliary (for details, see Khachaturyan, 2023b).

| (2) | gɔ̰́ | wɛ̄ | lɛ̄ | ŋ̄ | dɛ̰̄ | ká. |

| man:h | dem | 3sg.ex | 1sg | husband | with | |

| ‘This man is my husband’ [el.] | ||||||

Mano has four markers, called here “non-verbal predicators”, that make an NP into a self-standing construction that forms a complete utterance and accomplishes a speech act. These predicators are typically used only with the nominal term in the position immediately preceding it, although in some cases, a locative adjunct can be used. They are restricted to the present tense. The word order is NP–predicator. The markers belonging to this category are gɛ̰̀, wɔ́, and lɛ̄, as well as lɛ́, which was introduced in Section 1 and which is the focus of this paper. Specifically, this study explores the invariant function of this marker, and the ensuing specific status of the whole construction, beyond the cover terms “predication” and “clause”.

The predicators wɔ́ and gɛ̰̀ are typically used in deictic presentation constructions, whose main function is to shift attention to a referent physically present at the interaction scene. The predicators lɛ̄ and lɛ́ are used primarily for the identification of non-visible and abstract referents. Unlike referential identity construction in (2) with a subject and a predicate NP, lɛ̄ and lɛ́ can be used with a single nominal term preceding the predicator. The second term is unexpressed but contextually identifiable (see Creissels, 2022). It can alternatively be considered non-existent, with the predicate NP being the sole lexical constituent of the construction, which—as is described below—has a range of functions falling in the domain of merely presenting or naming the referent of this NP. For a discussion on whether the only nominal term used with predicators in the identity construction is part of the non-verbal predicate or is its argument, see Khachaturyan (2023a).

This paper focuses on the marker lɛ́; details on other predicators can be found in Khachaturyan (2023a). Lɛ́ (it also has a variants tɛ́, nɛ́ (in a nasal context) and a floating high tone) never occurs in a clause-final position and requires another element after it. Most commonly, it is a demonstrative: wāā~wɛ̄~ɓɛ̄ or yāā~yā~ā~ā̰. The latter demonstrative can also take form of a simple vowel assimilating to the preceding mid-open one, with four additional variants (ɛ̄, ɔ̄, ɛ̰̄, ɔ̰̄). These demonstratives are generic in function and, when used within an NP, can combine with both exophoric and endophoric referents (Khachaturyan, 2020); see léé wɛ̄ ‘this woman’ in ex. (7). They contrast with purely endophoric (more specifically, anaphoric) and purely exophoric demonstratives, which we briefly mention in Section 5. Combined with a demonstrative, lɛ́ is commonly used with endophoric referents for identification, as in (3) and (4).

| (3) | gèlè | lɛ́ | gbāā | wɛ̄. |

| war | att | now | dem | |

| ‘It is/There is war now.’ | ||||

| (4) | ŋ̀ | pḭ̀à̰ | tɛ̀kápɛ̀lɛ̀ | lɛ́ | ɛ̄. |

| 1sg.poss | story | end | att | dem | |

| ‘It is the end of my story.’ | |||||

Lɛ́ can also be used with exophoric referents in the presentative function (5).

| (5) | ī | kɔ́nɔ́ | lɛ́ | wɛ̄. |

| 2sg | food | att | dem | |

| ‘Here is your food.’ | ||||

3.1.2. Background on Prosody

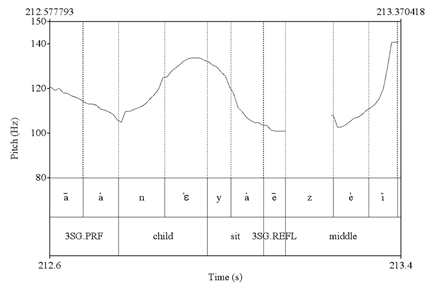

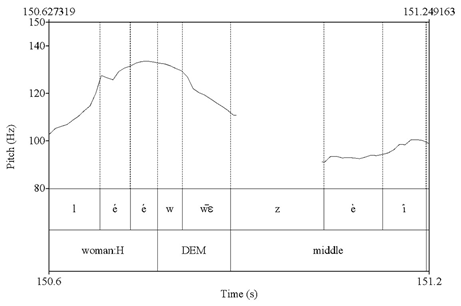

Mano is a tonal language, distinguishing three level tones: high, mid, and low. It also makes use of sentence-level prosody. The exact workings of prosody in Mano remain understudied, but there are two important utterance-level processes: (1) realization of a high tone as mid and low as falling, signalling the end of an utterance; (2) no final lowering, signalling continuation. These patterns are illustrated by examples (6) and (7), providing a contrast between the realization of the final tone of zèí: as high in (6) (a sharp rise) and as mid in (7) (only a slight rise, not even reaching the level of the previous mid tone).

| (6) | léé | wɛ̄ | āà | nɛ́ | yà | ē | zèí |

| woman:h | dem | 3sg.prf | child | sit | 3sg.refl | middle |

| āà | sɔ̄ | yèlè | à | mɔ̀. | |

| 3sg.prf | cloth | attach | 3sg | on | |

| ‘This woman has put a child on her back, she is attaching a cloth to it.’ [exper] | |||||

| (7) | ō | nɛ́ | yà-pɛ̀lɛ̀ | léé | wɛ̄ | zèí. |

| 3pl.ex | child | sit-inf | woman:h | dem | middle | |

| ‘They are putting a child on the woman’s back.’ [exper] | ||||||

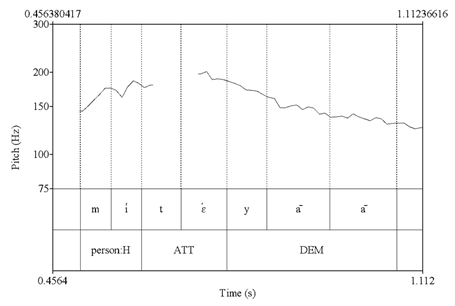

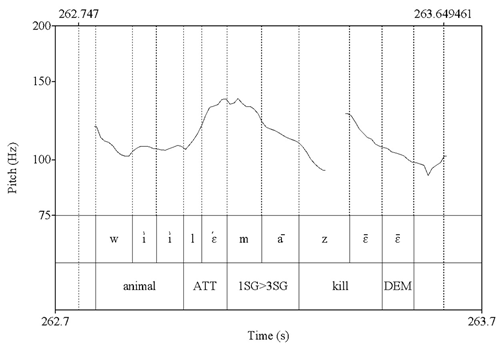

The difference in the final vs. non-final realization of mid and low tones is less. Example (8) illustrates a continuous intonation: the mid tone of the demonstrative yāā, which occurs mid-utterance, is realized as flat. Example (9) illustrates a general lowering of the pitch over two utterance-final mid tone segments, as a result of which the ultimate mid of the demonstrative ɛ̄ is realized as low as the low tone of the utterance-initial wìì.

| (8) | mí | tɛ́ | yāā |

| person:h | att | dem | |

| ‘this person’ | |||

| (9) | wìì | lɛ́ | mā | zɛ̄ | ɛ̄ |

| animal | att | 1sg.pst>3sg | kill | dem | |

| ‘[I did not hit a person,] it is an animal that I killed.’ | |||||

To summarize Section 3.1, we have discussed simple constructions with the predicator lɛ́, which can be used to present or, more commonly, identify a referent. Lɛ́ is usually followed by a demonstrative. We have also distinguished between a final lowering and a continuation intonation. The final mid tones, including those of demonstratives, tend to be realized as falling, while non-final mid tones tend to be realized as flat.

3.2. Functions of lɛ́—Comprehensive Overview

3.2.1. NP–lɛ́–DEM, (Cont.): Referent Identification

In Section 3.1.1, we introduced the function of lɛ́ as a predicator in a referent identifying construction (examples 3–5). In this function, the marker is typically accompanied by a demonstrative, and the overall construction can function as a standalone utterance, with a falling tone signalling utterance-finality. This final contour is optional though, and such a construction can also occur in a sequence with immediately following material, as in (10).

| (10) | [NP | ] | lɛ́ | DEM | [cont. | ] | |||||

| ŋ̀ŋ́gɔ̰̀ | Josef | gbē | lɛ́ | wāā | ŋ̀ŋ́gɔ̰̀ | Marie | gbē | lɛ́ | wɛ̄ | ò! | |

| isn’t.it | PropN | son | att | dem | isn’t.it | PropN | son | att | dem | inj | |

| ‘[This person,] it is a son of Joseph isn’t it, it is a son of Mary isn’t it?’ | |||||||||||

3.2.2. NP–lɛ́–DEM, Cont.: Referent Introduction

A sequence NP–lɛ́–DEM with a continuation intonation can be used for a related function of referent introduction. The boundary between referent identification and introduction is blurred as it is not a categorical distinction. The NP can introduce an identifiable referent, providing new information relevant to the observed or discussed situation, as is the case in (3) “[It is/there is] war now” and (5) “[Here is] your food”. However, the same construction can have the function of merely introducing a referent that should become relevant only in the subsequent talk. This is illustrated by ex. (8). The full utterance that (8) was taken from is given in (11). The sequence NP–lɛ́–DEM thus introduces a referent, instead of identifying it (‘this person’, not ‘this is a person’). The non-final intonation on the demonstrative (flat mid tone) projects a continuation and the subsequent predication communicates something about the referent via a referential identity construction whose subject is coreferential with the preceding NP.

| (11) | [NP] | lɛ́ | DEM | [cont. | ] | ||

| mí | tɛ́ | yāā | lɛ̄ | ŋ̀ | nɛ́ | ká. | |

| person:h | att | dem | 3sg.ex | 1sg.poss | child | with | |

| ‘This person, it is my child.’ | |||||||

The structural identity between identifying constructions with a continuation (10) and a referent introduction construction (11) is remarkable and will be important for the unifying analysis in Section 5.

3.2.3. NP–lɛ́–Clause–DEM, Cont.: Relative and Hanging Constructions

So far, we have discussed sequences NP–lɛ́–DEM with no intervening material. However, DEM does not always immediately follow lɛ́, and there may be an additional clause separating them. The NP is taken up again in the clause by a resumptive element, either in the subject position, an auxiliary (except 3sg existential auxiliary, which can be dropped), or, in a non-subject position, a pronoun. In such constructions, there may be a continuing or final intonation on the demonstrative.

In case of continuing intonation, if the NP’s referent is taken up yet again in the predication(s) following the demonstrative, the resulting function of the construction can be that of relativization. Indeed, the sequence NP–lɛ́ introduces the referent, the clause says something in addition to help identify it, and the continuation communicates the main piece of information. In such a case the referent is mentioned at least three times in the overall utterance: by the initial NP, by some element in the subsequent clause, and by some element in the continuation, which are all represented in bold in (12) and (13) below. Mano thus represents a non-reduction strategy of relativization, and more specifically, a correlative strategy (for details, see Khachaturyan, 2023b; on correlatives in Mande, see Creissels, 2009; Makeeva, 2013; on other types of relative clauses in Mano, see Khachaturyan, 2015).

| (12) | [NP] | lɛ́ | [clause | ] | DEM | [cont. | ] | ||

| ŋwɔ́ | lɛ́ | ā | gèē | wɛ̄ | ŋ́ŋ̀ | lō | à | kɛ̄-ɛ̀. | |

| problem | att | 3sg.pst>3sg | say | dem | 1sg.ipfv | go:ipfv | 3sg | do-ger | |

| ‘The thing that he said (lit. the thing is he said it), I will do it.’ | |||||||||

| (13) | [NP] | lɛ́ | [clause | ] | DEM | |||||

| sɛ́lɛ́ | lɛ́ | nɔ́ | ō | ŋwɔ́ | yā | kɛ̄-pìà | à | yí | ā | |

| village | att | just | 3pl.pst | problem | dem | do-inf | 3sg | in | dem |

| [cont. | ] | ||||

| ē | kɛ̄ | sɛ́lɛ́ | nɛ́ɛ́ | dò | ká. |

| 3sg.pst | do | village | small | indef | with |

‘The village where these events were taking place was a small village (lit.: the village is, these events were taking place in it, it was a small village).’

The referent of the construction-initial NP is not necessarily taken up again in the continuation. In such a case, NP–lɛ́–clause–DEM, cont. functions as a construction that introduces a referent in an elaborate fashion: the NP provides general information, such as its type (person, animal, issue), and the full clause as an elaboration required to identify it. The continuation then communicates something related to this referent without overtly mentioning it. As such, it is functionally and structurally parallel to hanging topic constructions (Villa-García, 2023) and to “projecting constructions” in Interactional Linguistics of the kind the issue is… (Günthner, 2011; Polak-Yitzhaki, 2020).

| (14) | [NP] | lɛ́ | [clause | ] | DEM | ||

| ŋwɔ́ | lɛ́ | kò | lō | ā | kɛ̄-ɛ̀ | ɛ̄ | |

| problem | att | 1pl.sbjv | go:ipfv | 3sg | do-ger | dem |

| [cont. | …] | ||||

| à | gɔ̰̄ | yā | bílí | ā | sí... |

| bridg | man | dem | corpse | dem | take |

‘The thing that we are going to do (lit.: the thing is, we are going to do it), take the corpse of that man...’

Khachaturyan (2023b) argues that relative clauses in Mano are a subset of paratactic hanging constructions with a coreference relationship between the initial NP and some element in the continuation part, while in hanging constructions as a whole coreference is not a requirement. A key argument is that the syntax of relative clauses can be shown to be “flat”, with parataxis rather than subordination.

3.2.4. NP–lɛ́–Clause–DEM, (Cont.): Focus and WH-Questions

A further set of constructions with a clause between lɛ́ and the demonstrative, with or without continuation, are constructions associated with effects of correction, identification, and content-questions associated with the notion of focus. This is illustrated by (15), where the discussed construction constitutes a separate utterance without a continuation.

| (15) | [NP] | lɛ́ | [clause | ] | DEM |

| wìì | lɛ́ | mā | zɛ̄ | ɛ̄. | |

| animal | att | 1sg.pst>3sg | kill | dem | |

| ‘[I did not hit a person,] it is an animal that I killed.’ | |||||

The NP can contain a question word, in which case the construction becomes a WH-question. In (16), below, the form mɛ̄ɛ́ is a merger between the question word mɛ̄ ‘what’ and lɛ́. Note that the final element in (15) is a demonstrative adverb yī that has not been introduced before. Indeed, it can replace ɓɛ̄ and yā in the clause-final position.

| (16) | [NP]>ATT | [clause | ] | DEM | |||

| mɛ̄ɛ́ | māē | ŋ̀ | lō | à | kɛ̄-ɛ̀ | yī? | |

| what>att | 1sg.emph | 1sg.sbjv | go:ipfv | 3sg | do-ger | there | |

| ‘What will I do there?’ | |||||||

The function of the continuation may be clause-combining with no additional pragmatic effects (17).

| (17) | [NP] | lɛ́ | [clause | ] | DEM | |||

| chinois | lɛ́ | ē | ɲínà | ē | kílíā | kṵ́ | ā̰ | |

| Chinese[fr] | att | 3sg.pst | spirit | 3sg.refl | dem.anaph | take | dem |

| [cont. | ||||||||

| wáà | gèè | à | chinois | à | ɓéē | lɛ̀ɛ́ | gbāā | bɛ̰̀ɛ̰̄ |

| 3pl.jnt | say:jnt | bridg | Chinese[fr] | 3sg | living | 3sg.ipfv | now | be.able |

| ] | |||

| gbāā | tó | á | yí. |

| now | stay | 3sg | in |

| ‘[There is this lie people are spreading in Conakry, they say that somebody caught an evil spirit,] A CHINESE PERSON caught the evil spirit (lit.: Chinese person is, he caught the evil spirit = it was a CHINESE PERSON who caught the evil spirit), they say he now cannot stay alive (lit.: his living cannot stay there now).’ | |||

3.2.5. NP–lɛ́–Clause–DEM, (Cont.): Thetic Reading

The last usage of lɛ́ that can be linked to a separate pragmatic function is the marking of a nominal constituent in thetic sentences. Thetic statements express a single unit of information that is indivisible into topic and comment parts (Sasse, 1987). A cross-linguistically common pattern for thetic sentences is a configuration where the nominal constituent is marked similarly to a narrowly focused one (Lambrecht, 2000; Güldemann, 2010). This is also the case in Mano, as (18) illustrates.

| (18) | [NP]>ATT | [clause | ] | DE | ||

| sálà | ŋ̀ | zɔ̰̀ɔ̰̀ | ī | lɛ̀ɛ̄ | ɓɛ̄. | |

| sacrifice | 1sg.ipfv>3sg | show:ipfv | 3sg | to | dem | |

| (When you leave), I will show you a sacrifice (to make) (lit.: A SACRIFICE I will show to you).’ | ||||||

However, when a continuation occurs after the demonstrative, there may be an additional interpretive effect involved, namely, causality, which has been shown to accompany thetic utterances (Vydrina, 2020), as illustrated by (19).

| (19) | [NP | ] | lɛ́ | [clause | ] | DEM | |||

| mɔ̀ɔ̀ | bɛ̰̀ɛ̰̄ | lɛ́ | ē | kɛ̄ | nū-pìà | mīī | mɔ̀ | ɔ̄… | |

| birds | also | att | 3sg.pst | do | come-inf | person | on | dem | |

| ‘{A woman is preparing food to bring to a child who was sent out to the rice field to chase the birds. The child needs a lot to eat because the work is physically exhausting.} (Because) THE BIRDS are coming (lit.: bird also is, it is coming) [even if you eat, it does not satisfy you]’ (In other words, because BIRDS are coming, the child must eat a lot). | |||||||||

Indeed, Sax (2012) analyses English thetic sentences with accented subject (e.g., -Why are you so late? -My CAR broke down.) as introducing a referent whose appearance in the discourse provides a contextually sufficient contribution, commonly with the function of an explanation or self-justification. The activity related to this referent is, in such cases, predictable from the nature of the referent itself and the context. In this account, these utterances shift attention to a referent, with the attention shift achieving the relevant discourse effects (Wilson & Wharton, 2006; Sax, 2011).

As in the case of identifying and referent introduction construction, hanging topic/relativization, focalizing, and thetic usages all employ a structurally identical, or simply the same, construction despite having very different functions. We explore this observation in search of the invariant function in the next section.

4. Analysis and Discussion: Towards an Invariant Function of Attention Shift

All constructions with lɛ́ include an NP preceding it and a demonstrative following it but are distinguished depending on whether there is a clause between the NP and the demonstrative and whether there is a continuation after the demonstrative. Table 1 summarizes all the constructions and respective functions of lɛ́ discussed above, with references to the sections where they were introduced.

Table 1.

Family of interpretations of the lɛ́ (clause) DEM construction.

As can be seen in Table 1, instead of singling out a particular set of morphosyntactic properties as the construction with necessary and sufficient conditions, with minor variations in the formal structure we can arrive at a wide array of functions, and a family (Hopper, 2001) or network (Diessel, 2019) of constructions. At the extremes, the family members may share few features, such as the identifying construction and the relativization construction. And yet, there are often trivial or not-so-trivial functional similarities and inherited properties (Goldberg, 2013) across the family. Moreover, shifting away from the clause-driven view on the analysed structures allows us to suggest that, at least originally, we deal with a single non-clausal construction. The observed differences are a result of its combination with other constructions that jointly produce longer combinations of constructions (constructs). Some of the frequent constructs, such as the relativizing one, can have then become separate constructions. This idea can appear puzzling at first, since the same sequence can have very different interpretations: thus, NP–lɛ́–clause–DEM, cont. can be interpreted as a hanging topic, a focus, or a thetic construction, covering very different categories of information structure. It also has a presentative function, and an apparently entirely unrelated syntactic function of relativization. How can all these disparate usages be reconciled within a single construction with a unified function?

We suggest that the analysis of the construction X–lɛ́ (–clause)–DEM as an instruction that an attention shift to its referent will produce a contribution that can be locally assessed and responded to provides the answer to this question. As we now proceed to arguing in more detail, the specific interpretations addressed above stem from the combination of this function with intonational marking, the precise configuration, and the context.

The framing structure of the noun X and the final demonstrative is the basic scaffolding for the attention shift. Indeed, demonstratives are commonly analysed along the lines of attention shifters (Diessel, 2006). Unlike the mere usage of a noun with a demonstrative though, the basic construction with lɛ́ (namely, X–lɛ́–DEM) presents information as locally self-sufficient material, an indication that the information can be assessed, acted upon, or be responded to separately. The recipient can locally identify the referent or fail to identify it, display comprehension about the chosen discourse trajectory, or evaluate the contribution as modifying the currently unfolding discourse in an unpredictable way. The final falling contour on the demonstrative signals that the speaker regards their contribution of “attend to X” as forming a separate action in conversation. This is the presentative interpretation (Here is X).

In the case the reason for the attention shift towards the referent is to be assessed with respect to the context, the construction is expanded with the clause between lɛ́ and the demonstrative. In this case, lɛ́ indicates the upcoming requirement for the attention shift while the noun preliminarily foreshadows the nature of the referent. However, it is the clause that follows lɛ́ and precedes the demonstrative that allows the recipient to identify the referent, and assess its contextual relevance and the reason for the requirement to attend to it. With the content of the clause being contextually given or predictable and the contour on the demonstrative falling, the utterance receives a narrow focal or thetic interpretation, respectively. The attention shift is evaluated with respect to the context provided by the clause.

Thus, with final terminating (falling) intonation on the demonstrative, the sequence X–lɛ́ (– clause)–DEM conveys the essence of what the speaker wanted to communicate. In that case, attention shift becomes the goal of the communicative act and, as such, can be interpreted as a claim of identity, or as a predication (it is X), or else as an update or specification, typically called a “focus construction” (it is X that Y).

The attention shift may also function as a separate, but, unlike presentatives, not self-sufficient contribution. The speaker may judge that the recipient requires further contextual information but can locally identify the referent before the discourse proceeds. In this case, the structure contains continuation, which is projected by the continuing intonation on the demonstrative. Attention shift in those cases is to be interpreted by the addressee as a preparatory communicative act and serves an underspecified cataphoric function. This happens in cases classically regarded as left detachments (Ozerov, 2025b). In the case of Mano, these are referent introduction constructions, relativizations, and hanging topics.

Crucially, since the instruction “attend to X” is broad enough, it is possible to achieve a stacking effect with the same attention centre, X, and several clauses within the same sequence, such as in (20). The first clause in the sequence provides a background, which enables identification (whence, a relative function), which in turn is pragmatically embedded in a construction that serves as an answer to the preceding question “What made you sit here?” (whence, a focus function). Both are latched to the same NP, ɲínà.1

| (20) | [[NP] | lɛ́ | [clause | ] | DEM]] | lɛ́ | [clause | ] | DEM | ||

| ɲínà | lɛ́ | lɛ̄ | pɛ̄lɛ̄í | ā | lɛ́ | ē | ŋ̄ | yà | zèē | ā. | |

| spirit | att | 3sg.ex | village | dem | att | 3sg.pst | 1sg | sit | here | dem | |

| ‘It is the spirit which is in the village that made me sit here (lit.: It is the spirit, it is in the village, it made me sit here).’ | |||||||||||

The overall effects depend on the status of the referent with respect to discourse, intonation, and broader interactional context (Ozerov, 2025b, inter alia), and can even result in a blended interpretation. Example (17), repeated below as (21), is particularly revealing in that regard as it straddles the partition between a narrow-focus assertion and a topicalization, making distinctions crucial for, e.g., English, redundant for Mano.

| (21) | [NP] | lɛ́ | [clause | ] | DEM | |||

| chinois | lɛ́ | ē | ɲínà | ē | kílíā | kṵ́ | ā̰… | |

| Chinese | att | 3sg.pst | spirit | 3sg.refl | dem.anaph | take | dem |

| [cont. | ||||||||

| wáà | gèè | à | chinois | à | ɓéē | lɛ̀ɛ́ | gbāā | bɛ̰̀ɛ̰̄ |

| 3pl.jnt | say:jnt | bridg | Chinese[fr] | 3sg | living | 3sg.ipfv | now | be.able |

| ] | |||

| gbāā; | tó | á | yí. |

| now | stay | 3sg | in |

| ‘[There is this lie people are spreading in Conakry, they say that somebody caught an evil spirit.] A CHINESE PERSON caught the evil spirit (lit.: it is a Chinese person, he caught the evil spirit), they say he now cannot stay alive.’ | |||

In the context of (21), where the discussed issue is “somebody catching an evil spirit”, the new, unpredictable, updating part is “a Chinese person”, which as such fits the usual definition of a narrow focus. In English, it would be expected to present this information as a self-standing update, parallel to a full predicative clause with a narrow focus, namely, a cleft (“It is a CHINESE PERSON, who caught an evil spirit”). However, the continuing intonation at the end of this Mano clause signals that this referent has been introduced for the purpose of providing further information about him, as happens in topicalizations (“a CHINESE PERSON who caught an evil spirit, [he] cannot stay alive”).2 This finding partially reminds one of previous analyses in information structure that bridged hanging topics with focal, updating information. For example, Bickel (1993) echoes Jakobson’s (1936) view that left-dislocated constituents are thetic referent introductions. In Erteschik-Shir’s model of information structure (Erteschik-Shir, 1997), new referents are focal, and additionally acquire a topical status if continued by an assertion made as about them. However, unlike English, where similar marking, namely, an accent, occurs both on new topics and foci, the discussed constructions in Mano represent a different cluster of specific functionsː structurally, they unify hanging (non-contrastive) topics, narrow and thetic focus, referent identification, and—unexpectedly for pragmatic analyses—relativization. Interaction participants comprehend discourse not by mapping information on topical or focal roles, but navigate interactive discourse based on local communicative instructions that manage their attention and relate communicated material with contextual expectations.

5. Clausehood, Predicativity, Attention, and lɛ́-Marked Constituents

Admittedly, the function of attention shift is very broad and needs further justification, and potentially specification. Moreover, this function can also be associated with an unmarked NP, whose most typical function, cross-linguistically, is referent introduction (see below; also Ariel, 1990). Attention shift has also been claimed to be the core function of demonstratives (Diessel, 2006). The evident question then is what does the predicator, which appears in combination with a noun and a demonstrative, add to this function. Let us return to the morphosyntactically most basic constructions with lɛ́, identification and referent introduction, which, as we demonstrate, have the clearest connection to the function of attention shift. Predicators used in identification constructions, such as (3)–(5), belong to the typological class of demonstrative predicators and, in many languages, have formal similarities with other demonstratives (Killian, 2022). They shift attention, indeed, but unlike a bare NP or a demonstrative construction, the predicator signals that the attention shift is the ultimate local goal of the speaker’s utterance terminating with a demonstrative. Yet, because in Mano the predicator is co-opted in a range of functions, the situation is more complex: the attention shift may only be a preparatory step. Indeed, in the case of a clause intervening between the predicator and the demonstrative (as in relativization and cleft-like interpretations), the predicator creates an anticipation (“projects”, in the sense of, e.g., Auer, 2009) that the mentioned NP initiates the two-step process. The first step is attention shift to a referent foreshadowed by its core properties, which are expressed by the initial NP. The referent is then fully elaborated by the subsequent clause. Finally, the final demonstrative requires the addressee to identify the referent, accomplishing the act of an attention shift as a separate local action in interaction, locally evaluated by the recipient.

Crucially, the same construction can have both predicative and non-predicative functions. This is the case of the sequence NP–lɛ́–DEM, cont., which can be used for referent introduction (11), but also for predicative identification with a follow-up (10). Attention shift, thus, can be interpreted as having a predicative or a non-predicative function. Predicativity is however epiphenomenal of a more general discourse function.

The analysis of lɛ́ as an element that may, depending on context, be interpreted as having or not having a predicative function is reminiscent of the analysis of cleft constructions3. Indeed, cleft constructions are a well-known puzzle to syntax, semantics, and pragmatics: while being syntactically biclausal, they express a single proposition. According to an influential account by Lambrecht (2001), in English cleft constructions, the first element in the biclausal sequence (it is in (22) below) is semantically empty. Instead, is, the copula, together with it, its empty, non-referential subject, assigns a pragmatic role, that of focus, to an argument (the country) of the forthcoming predicate.

| (22) | It’s the country that suits her best. (Lambrecht, 2001, p. 493) |

In English, like in many other languages, cleft constructions are formally indistinguishable (putting aside possible prosodic differences) from bi-propositional sequences where the non-verbal predicate maintains its semantic value. Thus, (22) has two interpretations:

- monopropositional cleft construction (it is non-referential, is is not predicative): The COUNTRY (=countryside) suits her best (compared to for example large towns).

- bipropositional construction (it is referential, is is a copula in a referential identity construction, the second proposition is expressed as a restrictive relative clause): It, the aforementioned country, is the country that suits her best.

Such semantic polyfunctionality raises a further question: whether copulas and other non-verbal predicates are indeed, in line with Lambrecht’s proposal, tumbler switches, with their predicative function being activated depending on the context where they appear. Lambrecht’s solution would satisfy some semantic models but would hardly provide a unified account of the grammatical polyfunctionality. Our analysis in terms of attention shift is an attempt to provide such a unified account.

However, in the context of the Mano data presented here, such an analysis leads to the more general problem: how exactly do constructions with lɛ́ become clauses and what does it mean at all for a construction to be predicative? While discussing at length how predicative demonstratives are demonstratives (in particular, by being members of the same paradigm as more prototypical, adnominal or locative demonstratives), Killian (2022) does not address the question of why they are predicative. It seems that the reasoning behind this could be that if there is no better candidate for being the predicate, the demonstratives are predicative by necessity. Note that Haspelmath (2025) acknowledges that many non-verbal constructions (including identificational and presentational, which Haspelmath calls “deictic-identificational”) are not predicational since they lack a subject and a predicate in a traditional sense. He suggests calling these constructions “non-verbal clause constructions”, but this does not solve the discussed problem since the concept of “clause” itself avoids a coherent definition (De Beaugrande, 1999).

The question becomes less of a problem however if we abandon the generally accepted idea that utterances must constitute clauses in one way or another, and that there must be a predicate within them. Indeed, the theoretical concept of clausehood typically presupposes a systematic mapping between a clausal structure and a locally sufficient communicative contribution. While this contribution is often assumed to correspond to the update of the common ground (Stalnaker, 2002), interaction participants pursue diverse goals during a conversation beyond updating each other. The identifying constructions that we analysed in this paper serve specific discourse-management functions. For example, gèlè lɛ́ gbāā wɛ̄ ‘it is a war now’ (3) foreshadows a description of a fight between two characters, while ŋ̀ pḭ̀à̰ tɛ̀kápɛ̀lɛ̀ lɛ́ ɛ̄ ‘it is the end of my story’ (4) signals that the speaker has finished talking. If we take the communicative action of attention shift as a basic function, the actions of both foreshadowing and closure arise as its local interpretations in a given stretch of discourse. The predicative function reappears in this account as a consistent mapping between a local communicative function and a dedicated structure. This view is indeed prominent in the current research on natural interaction. Cross-linguistic findings in this regard emphasise the structurally basic status of non-clausal (or “unipartite”, “monomial”) utterance, although potentially calling the only constituent ‘a predicate’ (Izre’el, 2018; Ewing, 2019). This analysis recasts clausal structures as emerging phenomena rooted in a variety of more basic structures that accomplish diverse communicative tasks (Thompson, 2019).

It remains for further research to ask the crucial, and barely explored, question of when do referent introductions and attention shifts constitute a separate action in discourse. Similarly, although it is generally agreed that existential constructions (There is/was…) perform this function, it is unclear when speakers use this more effortful strategy in place of using a lexical noun. Generally, such a construction is employed when the referent identification is non-trivial or when the referent is expected to have a prominent discourse role (Izre’el, 2022). Similarly, for Mano, the sequence NP–lɛ́–DEM is one among several strategies of introducing new referents; a bare NP and an NP with a demonstrative are also among them. Corpus data suggests however that NP–lɛ́–DEM is used when an extra effort is needed to secure the identifiability of the referent and joint attention on it (Khachaturyan, 2020): ‘this person’ in (16), for instance, is taken from a translation of the Sermon on the Mount, where God is speaking from a cloud, is invisible, and cannot point.

Clearly, there are numerous points that must be elaborated further in this analysis and questions to be explored. The first question is related to the actual frequencies of constructions with lɛ́. Indeed, the most syntactically basic constructions of the family, identification and referent introduction, which exhibit the attention shift function in its purest form and as such motivate its postulation as the basic invariant function, are also the rarest in the corpus and thus are not frequency-based prototypes. Thus, in a subcorpus of Mano texts (mostly narrative with some conversations)4, only 10 out of 145 tokens of lɛ́ are used in the identification function. Most commonly, lɛ́ is used for relativization (50 tokens), focus (50), and hanging constructions (35). As for referent introduction, in the existing Mano corpus, usually, endophoric referents are first introduced by bare NPs or NPs accompanied by a demonstrative alone (cf. Haig & Schnell, 2016 for cross-linguistic findings). We performed a separate study of left-detached NPs, which is a syntactic position cross-linguistically associated with attention shift in interaction (Ozerov, 2025a). We found 34 tokens of bare NPs or NPs with other determiners except demonstratives and 49 NPs with demonstratives. The latter group contained only three tokens of lɛ́, all three used with anaphoric demonstratives with which lɛ́ is obligatory (Khachaturyan, 2020). However, the study was based on narratives and narrative retellings

(see note 4), and the narrative genre does not represent the settings of natural multimodal interaction, where monitoring and shifting the interlocutors’ attention is one of the primary tasks with which speakers deal. In interaction, non-clausal NPs obtain a prominent role (e.g., Helasvuo, 2019; Ozerov, 2025a). Moreover, in some types of interactional data, such as argumentation, non-verbal constructions have been found to be among the most prominent types (Mayes, 2024). We expect that in an interactional corpus of Mano, identifying constructions and referent introduction with lɛ́ will be more common.

The second issue is related to the difficulty in defining what exactly constitutes attention shifting. Joint attention in case of exophoric referents is relatively straightforward: there is a here-and-now present referent that interlocutors orient to with the help of linguistic expressions, aided by gesture, gaze, and body position (Enfield, 2003). Lɛ́ in Mano also plays a role in that process, since both exophoric demonstratives tɔ́ɔ̄ and dḭ̀ā̰, which we have not discussed in this paper, either have tɛ́, a variant of lɛ́, in their underlying form (in case of tɔ́ɔ̄) or obligatorily combine with lɛ́~tɛ́ (in case of dḭ̀ā̰). Similarly, in example (11), where gesture was impossible (God speaking from a cloud), a combination of tɛ́ with a generic demonstrative wɛ̄ was used. Endophoric referents are more problematic, however. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, lɛ́ also combines with anaphoric demonstratives. Here, Mano exhibits a more complex system, with further sensitivities that require additional research. In the predicative function, lɛ́ is mostly used with endophoric referents. It is another demonstrative predicator wɔ́, introduced in Section 3.1, that is more commonly used in the presentative function shifting attention to exophoric referents. This demonstrative has many parallels with lɛ́: it is also used with a demonstrative and it can also be used in the focus function (see Khachaturyan, 2023a), as illustrated in example (23). Here, the boy’s pointing is coordinated with wɔ́ ɔ̄.

| (23) | [NP | ] | wɔ́ | DEM |

| ŋ̀ | pɛ̄ | wɔ́ | ɔ̄ | |

| 1sg.poss | thing | pres | dem | |

| ‘Here is my thing’ | ||||

What constitutes attention shifts in the case of endophoric referents and, more broadly, mental phenomena, remains undertheorized. However, there are recent studies focusing on attention to mental states, such as beliefs (O’Madagain & Tomasello, 2021). Moreover, joint attention to entities absent from the here-and-now of the interactional event, commonly discussed under the term of “displacement” (Hockett, 1960), is considered one of the hallmarks of human communication and language evolution (Dor, 2014; Corballis, 2019). Indeed, according to Diessel, “they [endophoric demonstratives] involve the same psychological mechanisms as demonstratives that speakers use with text-external reference. In both uses, demonstratives focus the interlocutors’ attention on a particular referent. In the exophoric use they focus the interlocutors’ attention on concrete entities in the physical world, and in the discourse use they focus their attention on linguistic elements in the surrounding context” (Diessel, 2006, p. 476). The claim that the psychological—and, as we may develop—interactional mechanism of joint attention on endophoric referents is the same as for exophoric referents is a stipulation and is not empirically grounded. It remains open for future research to demonstrate joint attention on endophoric referents as an interactional achievement, and what role, if any, linguistic devices, as well as gaze, bodily position, and gesture play in that process. For example, Skilton (2024 and references therein) argues that reference to previously mentioned referents occurs with reduced gestures; she does not discuss however how addressees orient towards those gestures. By contrast, Ozerov (2025a) focuses on the interactional uptake of attention alignment, including mental attention and its interactional and multimodal aspects, as one of the functions of left-detached NPs in Anal Naga (Tibeto-Burman, India). He argues that in some cases of left detachment, NPs are introduced to negotiate joint attention on this referent as the only goal of the detached NP, and as such are a likely preparation for further action. He shows that, in interactional data, the process is often evident from vocal and multimodal cues, such as backchanneling, co-gesture, and nodding. The constructions with lɛ́ in Mano require further multimodal, interactional, and experimental research.

6. Conclusions

This paper, based on naturalistic discourse in Mano and on both morphosyntactic and prosodic characteristics, presents the family of usages of Mano constructions formed with the marker lɛ́, including the identifying function, referent introduction, focus, relativization, and hanging topic interpretations. While the identifying usage can be treated as a separate predicative NP, and lɛ́ within it as a predicator, in all the other constructions lɛ́ does not have the predicative function.

For Mano lɛ́, we suggest a conventional mapping between a construction (NP-lɛ́-(clause)-DEM-(cont.)) and a speaker’s action in the interaction. Probably unsurprisingly, the action performed by such a construction is in line with the most basic function of NPs, especially those with demonstratives—attention shift to a referent. However, the contribution of lɛ is to present the attention shift as a locally self-sufficient action that can result in the recipient’s uptake. Depending on both the structural (the type of construction involved) and the pragmatic grounds (the status of referent as given or new; its background-setting or updating role), the construction has a range of recurrent and conventionalized functions in the domain of pragmatics (information structure), discourse structuring (projecting constructions), and semantics (reference modification parallel to the function of relativization). In turn, attention shift can be interpreted as having or not a self-sufficient communicative contribution, with the term ‘predicate’ employed for it in the former case.

Speech act-based definitions of “sentence” would regard the Mano construction as a sentence type, while formal criteria, such as having a subject and a predicate, would not treat it as a clause, let alone a sentence (see De Beaugrande, 1999 for an overview). However, we see no need for a discrete definition that would uniquely delineate the notion of a clause while remaining operable for linguistic and typological analysis. Instead, we suggest that there are mappings between diverse language-specific constructions and recurrent speakers’ actions in interaction. The Mano construction with lɛ́ is one of the constructions that exhibit such a mapping, and as such can be used with a consistent communicative goal—a self-standing attention shift to a referent. Its function deviates from the most intuitive, updating usage of language, but that does not diminish its role, or the place that self-standing attention shifts play in conversation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.O. and M.K.; methodology, M.K.; formal analysis, P.O. and M.K.; investigation, M.K.; resources, M.K.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.O. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, P.O. and M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Kone Foundation, grant N 20190756, and the Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK (https://tenk.fi/en), ethical review was not required for this project, but the project closely followed their recommendations concerning work with human participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The corpus used for this study is being prepared for publication at Fin-Clarin.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ritva Laury and Yoshi Ono, the editors of the present special issue, for their valuable comments at various stages of manuscript preparation. We are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their contributions, as well as Yael Maschler for a general inspiration. Lastly, we thank Pé Mamy for his work on the Mano corpora and experimental data, as well as all Mano speakers who contributed to the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

1—first person; 2—second person; 3—third person; anaph—anaphoric; att—attention shift; bridg—bridging marker; dem—demonstrative; ex—existential; ger—gerund; h—high tone; indef—indefinite; inf—infinitive; inj—interjection; ipfv—imperfective; pl—plural; poss—possessive; prf—perfect; pst—past; refl—reflexive; sbjv—subjunctive; sg—singular.

Notes

| 1 | Note that the second token of lɛ́ in (20) is not adjacent to the NP associated with it. While in (20) lɛ́ can be interpreted as part of a focus construction where the focalized element is an NP with a relative clause, lɛ́ non-adjacent to an NP can also be interpreted as a relativizer (Khachaturyan, 2015, p. 233, ex. 6.71 and 6.73), and be used in a narrative chain (Khachaturyan, 2015, p. 236). These usages represent a different function of lɛ́, where it does not serve to draw attention to the referent but functions as a clause-linking marker. The constructions with lɛ́ where it both draws attention to the referent and connects to subsequent discourse are a middle point between these different functions. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Notice that the referent “Chinese person” is not contrastive here, and an analysis along the lines of a narrow contrastive domain within a topic (as in “MY son… plays SOCCER”, as opposed to your son) would not hold. The discussed referent updates an open proposition, as happens in typical cases of narrow focus, but does so with an NP-like construction. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Mano construction with lɛ́ in the focus function bears a close superficial similarity to a particular type of English clefts, namely, reverse WH cleft. Compare (i) and (ii) (the Mano glosses are simplified for the sake of comparison):

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | https://corporan.huma-num.fr/Archives/corpus=mev (accessed on 12 December 2025). Under agreement for publication with FIN-CLARIN (https://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:lb-2025111121, accessed on 12 December 2025). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Ariel, M. (1990). Accessing noun-phrase antecedents. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, P. (2009). On-line syntax: Thoughts on the temporality of spoken language. Language Sciences, 31(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, P. (2015). The temporality of language in interaction: Projection and latency. In A. Deppermann, & S. Günthner (Eds.), Temporality in interaction (pp. 27–56). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel, B. (1993). Belhare subordination and the theory of topic. In K. H. Ebert (Ed.), Studies in clause linkage (pp. 23–55). ASAS-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Corballis, M. C. (2019). Language, memory, and mental time travel: An evolutionary perspective. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creissels, D. (2009). Les relatives corrélatives: Le cas du malinké de kita. Langages, 174(2), 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creissels, D. (2022). A typological rarum in mande languages: Argument-predicate reversal in nominal predication. Mandenkan, 68, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beaugrande, R. (1999). Sentence first, verdict afterwards: On the remarkable career of the ‘sentence’. Word, 50(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diessel, H. (2006). Demonstratives, joint attention, and the emergence of grammar. Cognitive Linguistics, 17, 463–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diessel, H. (2019). The grammar network: How linguistic structure is shaped by language use. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dor, D. (2014). The instruction of imagination: Language and its evolution as a communication technology. In D. Dor, C. Knight, & J. Lewis (Eds.), The social origins of language (pp. 105–125). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Enfield, N. J. (2003). Demonstratives in space and interaction: Data from Lao speakers and implications for semantic analysis. Language, 79, 82–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erteschik-Shir, N. (1997). The dynamics of focus structure. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, M. C. (2019). The predicate as a locus of grammar and interaction in colloquial Indonesian. Studies in Language, 43(2), 402–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A. E. (2013). Constructionist approaches. In T. Hoffmann, & G. Trousdale (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of construction grammar. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, M. L., & Michaelis, L. A. (2001). Topicalization and left-dislocation: A functional opposition revisited. Journal of Pragmatics, 33(11), 1665–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güldemann, T. (2010). The relation between focus and theticity in the tuufamily. In I. Fiedler, & A. Schwarz (Eds.), The expression of information structure: A documentation of its diversity across Africa (pp. 69–93). Typological studies in language 91. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Günthner, S. (2011). Between emergence and sedimentation: Projecting constructions in German interactions. In P. Auer, & S. Pfänder (Eds.), Constructions: Emerging and emergent (pp. 156–185). Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haig, G., & Schnell, S. (2016). The discourse basis of ergativity revisited. Language, 92(3), 591–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haspelmath, M. (2025). Nonverbal clause constructions. Language and Linguistics Compass, 19(2), e70007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helasvuo, M.-L. (2019). Free NPs as units in Finnish. Studies in Language, 43(2), 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockett, C. F. (1960). The origin of speech. Scientific American, 203(3), 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, P. J. (2001). Grammatical constructions and their discourse origins: Prototype or family resemblance? In M. Pütz, & S. Niemeier (Eds.), Applied cognitive linguistics. Volume I, theory and language acquisition (pp. 109–130). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, P. J., & Thompson, S. A. (2008). Projectability and clause combining in interaction. In R. Laury (Ed.), Typological studies in language (Vol. e80, pp. 99–123). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izre’el, S. (2018). Unipartite clauses: A view from spoken Israeli Hebrew. In M. Tosco (Ed.), Afroasiatic: Data and perspectives (pp. 235–259). Current issues in linguistic theory 339. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Izre’el, S. (2022). The syntax of existential constructions: The spoken Israeli Hebrew perspective. Journal of Speech Sciences, 11, e022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, T. F., & Oshima, D. Y. (2002). Towards a dynamic model of topic marking. In Pre-proceedings of the information structure in context workshop (pp. 153–167). Stuttgart University, Stuttgart, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, R. (1936). Beitrag zur allgemeinen kasuslehre: Gesamtbedeutungen der russischen kasus. In Selected writings (Vol. 2, pp. 23–71). Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Khachaturyan, M. (2015). Grammaire du mano. Mandenkan, 54, 1–252. [Google Scholar]

- Khachaturyan, M. (2020). Common ground in demonstrative reference: The case of Mano (Mande). Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 543549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khachaturyan, M. (2023a). From copula to focus, vice versa, or neither? Mandenkan, 69, 87–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachaturyan, M. (2023b). Mano correlatives are non-subordinating. Mandenkan, 70, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killian, D. (2022). Towards a typology of predicative demonstratives. Linguistic Typology, 26(1), 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, N. (2023). Homonymy and polysemy of lē in Guro: Identificational, quotative, complementiser, focus and relative-possesive functions. In I. Kapitonov, M. Khachaturyan, S. Oskolskaya, N. Sumbatova, & S. Verhees (Eds.), Song and trees. Papers in memory of Sasha Vydrina (pp. 227–284). ILS RAN. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht, K. (2000). When Subjects behave like objects: An analysis of the merging of s and o in sentence-focus constructions across languages. Studies in Language, 24(3), 611–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, K. (2001). A framework for the analysis of cleft constructions. Linguistics, 39(3), 463–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L. (2016). Dislocations and information structure. In C. Féry, & S. Ishihara (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of information structure (pp. 402–421). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Makeeva, N. (2013). Кoммуникативные стратегии и кoррелятивная кoнструкция в языке кла-дан и других южных манде [Information structure and correlative construction in Kla-Dan and other Southern Mande]. Voprosy Jazykoznanija, 1, 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Maschler, Y., Lindström, J., & De Stefani, E. (2023). Pseudo-clefts: An interactional analysis across languages. Lingua, 291, 103538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschler, Y., & Pekarek Doehler, S. (2022). Pseudo-cleft-like structures in Hebrew and French conversation: The syntax-lexicon-body interface. Lingua, 280, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K. (1998). Detached NPs in Japanese conversation: Types and functions. Text & Talk, 18(3), 417–444. [Google Scholar]

- Mayes, P. (2024). Low transitive constructions as typical clauses in English: A case study of the functions of clauses with the nonverbal predicate be in stance displays. Languages, 9(12), 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, N. (2020). Information structure in spoken Japanese: Particles, word order, and intonation (Topics at the grammar-discourse interface 8). Language Science Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitina, T. (2011). Categorial reanalysis and the origin of the S-O-V-X word order in Mande. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics, 32(2), 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Madagain, C., & Tomasello, M. (2021). Joint attention to mental content and the social origin of reasoning. Synthese, 198(5), 4057–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, T., & Thompson, S. A. (1994). Unattached NPs in English conversation. Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 20(1), 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozerov, P. (2021). Multifactorial information management: Summing up the emerging alternative to information structure. Linguistics Vanguard, 7(1), 2020039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozerov, P. (2025a). Left detachment in a verb-final language: The interactional perspective. Linguistic Typology at the Crossroads, 5(1), 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozerov, P. (2025b). Left dislocation in spoken Hebrew, it is neither topicalizing nor a construction. Linguistics, 63(4), 907–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak-Yitzhaki, H. (2020). The Ha’emet (Hi) She- ‘the Truth (is) that’ construction: Emergent patterns of predicative clauses in spoken hebrew discourse. In Y. Maschler, S. Pekarek Doehler, J. K. Lindström, & L. Keevallik (Eds.), Emergent syntax for conversation: Clausal patterns and the organization of action (pp. 127–150). Studies in language and social interaction. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, T. (1981). Pragmatics and linguistics: An analysis of sentence topics in pragmatics and philosophy I. Philosophica, 27(1), 53–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasse, H.-J. (1987). The thetic/categorical distinction revisited. Linguistics, 25, 511–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, D. J. (2011). Sentence stress and the procedures of comprehension. In V. Escandell-Vidal, M. Leonetti, & A. Ahern (Eds.), Procedural meaning: Problems and perspectives (pp. 347–381). Current research in semantics/pragmatics interface 25. Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, D. J. (2012). Not quite ‘out of the blue’? Towards a dynamic, relevance-theoretic approach to thetic sentences in English. Relevance studies in Poland, 4, 24–53. [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbakova, O., Blasi, D. E., Gast, V., Skirgård, H., Gray, R. D., & Greenhill, S. J. (2024). The evolutionary dynamics of how languages signal who does what to whom. Scientific Reports, 14, 7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimojo, M. (2016). ‘Saliency in Discourse and Sentence Form: Zero Anaphora and Topicalization in Japanese’. In M. M. Jocelyne Fernandez-Vest, & R. D. Van Valin Jr. (Eds.), Information structuring of spoken language from a cross-linguistic perspective (pp. 55–75). Walter De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Skilton, A. (2024). Anaphoric demonstratives occur with fewer and different pointing gestures than exophoric demonstratives. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainton, R. (2006). Words and thoughts: Subsentences, ellipsis, and the philosophy of language. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stalnaker, R. (2002). Common ground. Linguistics and Philosophy, 25(5/6), 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S. A. (2019). Understanding ‘clause’ as an emergent ‘unit’ in everyday conversation. Studies in Language, 43(2), 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-García, J. (2023). Hanging topic left dislocations as extrasentential constituents: Toward a paratactic account. evidence from English and Spanish. The Linguistic Review, 40(2), 265–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vydrina, A. (2020). Topicality in sentence focus utterances. Studies in Language, 44(3), 501–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D., & Wharton, T. (2006). Relevance and prosody. Journal of Pragmatics, 38(10), 1559–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanuttini, R., & Portner, P. (2005). The semantics of nominal exclamatives. In E. Reinaldo, & R. J. Stainton (Eds.), Ellipsis and nonsentential speech (pp. 57–67). Springer. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.