Abstract

Research in Loanword Phonology has extensively examined the adaptation processes of Anglicisms into recipient languages. In the Tijuana–San Diego border region, where English and Spanish have reciprocally existed, Anglicisms exhibit two main phonetic patterns: some structures exhibit Spanish phonetic properties, while others preserve English phonetic features. This study analyzes 131 vowel tokens drawn from spontaneous conversations with 28 bilingual speakers in Tijuana, recruited via the sociolinguistic ‘friend-of-a-friend’ approach. Specifically, it focuses on monosyllabic Anglicisms with monophthongs by examining the F1 and F2 values using Praat. The results were compared with theoretical vowel targets in English and Spanish through Euclidean distance analysis. Dispersion plots generated in R further illustrate the acoustic distribution of vowel realizations. The results reveal that some vowels closely match Spanish targets, others align with English, and several occupy intermediate acoustic spaces. Based on these patterns, the study proposes two phonetically based corpora—Phonetically Adapted Anglicisms (PAA) and Phonetically Non-Adapted Anglicisms (PNAA)—to capture the nature of Anglicisms in this contact setting. This research offers an empirically grounded basis for cross-dialectal comparison and language contact studies from a phonetically based approach.

1. Introduction

Language contact scenarios involve the integration of structural elements from the languages in contact (Lanz, 2022; Silva-Corvalán, 2017). Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico, lies directly south of San Diego, United States. Both cities are widely known to form one of the most frequently crossed land borders in the world (Toledo & García, 2018, p. 106). The ongoing contact between Spanish and English across sociocultural, historical, and political forms has led to the widespread incorporation of Anglicisms into local speech (Toledo & García, 2018, p. 90). Nowadays, borrowings have become integral to everyday communication, particularly among younger speakers in Tijuana (Lanz, 2020, p. 51). Anglicisms are defined as lexical items originating from English that are adapted—linguistically and phonologically—within a recipient language (adapted from Gottlieb, 2005, p. 163). In Tijuana, Anglicisms typically exhibit two phonetic patterns: some conform to the Spanish phonological system, while others preserve English phonetic features.1 For instance, the words boss, crush, and match are often realized with English-like phonetic features ([bɑs], [kɹʌʃ], and [mætʃ]); whereas cash, plus, and top are consistently adapted to Spanish phonology ([kaʃ], [plus] and [top]).

According to Loanword Phonology (Bäumler, 2024; Calabrese & Wetzels, 2009; Duběda, 2020 inter alia), L2 categories may undergo phonological adaptation due to L1 constraints or be preserved with minimal modification to maintain L2 features (Bäumler, 2024, p. 2; Paradis & LaCharité, 2008, p. 92). Calabrese and Wetzels (2009) distinguished two primary mechanisms of phonological integration. First, nativization-through-production occurs when bilingual speakers retrieve an underlying representation from the mental lexicon and it is reshaped through production, based on the L1 phonological constraints (Calabrese & Wetzels, 2009, p. 2). Conversely, nativization-through-perception occurs when speakers with limited L2 proficiency rely on surface cues that often result in misperceived forms that align more closely with L1 categories (Calabrese & Wetzels, 2009, p. 2). Nevertheless, the Loanword Phonology framework—particularly the binary opposition between perception and production—may not fully capture the complexity of bilingual speech in highly dynamic contexts such as Tijuana. All participants in this study are bilingual, though to varying degrees, their vowel realizations suggest a more gradient process. In order to address this complexity, the present study incorporates experience-based models of bilingual phonetic development. Firstly, Speech Learning Model (SLM) (Flege, 1995) posits that bilinguals form L2 phonetic categories through comparison with L1 categories with outcomes influenced by age of acquisition, exposure, and frequency of use. Second, the Perceptual Assimilation Model (PAM) (Best, 1995; Best & Tyler, 2007) complements this view by emphasizing that L2 sounds are mapped onto perceptually similar L1 categories, often producing hybrid or intermediate forms. These frameworks are particularly suitable for analyzing the spontaneous bilingual speech examined here where some vowel realizations are not consistently predictable by a categorical model to either native language system.

In addition, previous investigations have emphasized the roles of orthographic influence and temporal–lexical integration in the adaptation of borrowed forms. As Lallier et al. (2014, p. 1178) observe, Spanish orthography is notably transparent, featuring a near one-to-one correspondence between graphemes and phonemes. This structural feature tends to promote adaptations that match with Spanish phonotactic norms as speakers often rely on spelling cues during phonological integration. Temporal–lexical factors also shape adaptation trajectories. For instance, while older borrowings are more likely to undergo phonological assimilation into the recipient language, newer Anglicisms often preserve source-language features (Haspelmath, 2009, p. 43). This trend is particularly evident in Tijuana, where English lexical items—especially among younger speakers—are increasingly incorporated with minimal phonetic modification (Escandón, 2019, p. 15). In this context, sustained exposure to English through media, education, and cross-border interaction has normalized the presence of English-origin vocabulary in everyday discourse, becoming a marker of sociolinguistic identity (Escandón, 2019, p. 118; Lanz, 2022, p. 87). Hence, lexical borrowing in Tijuana presents a complex interaction between structural constraints imposed by Spanish and sociolinguistic pressures stemming from the status and accessibility of English. These dynamics highlight the multifactorial nature of language contact, in which vowel realizations are shaped by the convergence of phonological, orthographic, lexical and social influences.

This study contributes to this line of inquiry by examining the phonetic behavior of monosyllabic Anglicisms produced in spontaneous bilingual speech. The study is found on formant-based acoustic analysis by examining the F1 and F2 values of vowel tokens to identify two phonetic realizations among Anglicisms: Phonetically Adapted Anglicisms (PAA) and Phonetically Non-Adapted Anglicisms (PNAA) to propose two empirically grounded corpora to account for gradient phonetic integration in this contact setting. These analyses can integrally characterize the degree of phonological integration in contact-induced lexical borrowings to reveal the mechanisms underlying lexical adaptations in bilingual speech. Additionally, the study aims to propose two phonetically based corpora based on acoustic analyses: one corpus involving adapted Anglicisms with Spanish phonetic features (PAA); another with English phonetic characteristics (PNAA). These corpora allow for the systematic investigation of segmental variation across lexical items, providing insight into the mechanisms of phonological adaptation in bilingual speech. By structuring the dataset around vowel-level acoustic criteria, rather than whole-word categories, the study aligns with current methodologies in corpus phonetics (Harrington, 2010, p. 11; Liberman, 2019, pp. 96–100), which research emphasize the role of frequency and fine-grained acoustic variation across speakers. Accordingly, the phonetic analysis and frequency distributions of Anglicisms presented here offer a novel lens through which to examine loanword integration, phonetic convergence, and contact-induced change in the specific sociolinguistic context of Tijuana Spanish. Finally, we propose the next questions to guide the present study:

- (a)

- What are the acoustic characteristics in terms of F1 and F2 formants of the vowels within the Anglicisms from this study?

- (b)

- How do the vowel realizations in spontaneous speech present a gradient continuum between Spanish and English phonological categories in a language contact setting?

- (c)

- To what extent can the development of two phonetically grounded corpora, based on the acoustic properties of vowels in monosyllabic Anglicisms, contribute to a more empirically robust typology of loanword integration?

2. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the methodological framework, including data collection procedures, participant recruitment strategies, corpus design, and the acoustic and statistical tools employed for analysis.

2.1. Corpus Design

2.1.1. Data Collection and Participants

The dataset comprises spontaneous conversations recorded with 28 bilingual speakers residing in Tijuana. All conversations were developed between the subjects and the investigators. The decision to focus on monosyllabic Anglicisms in spontaneous speech occurs from the need to analyze vowels under maximally controlled yet naturally occurring phonological conditions. Monosyllables provide consistent stress patterns and reduce the influence of prosodic variation that allow clearer comparisons across languages (Strange, 2005). This specific dataset, though quantitatively limited, enhances phonetic precision. By focusing on monosyllabic Anglicisms in naturalistic speech, the study aims to minimize prosodic variation and enhance the precision of formant analysis, despite the lower frequency of such tokens in spontaneous discourse (Bäumler, 2024, p. 4). Participants were selected through social networks to ensure relatively homogeneous sociolinguistic profiles, often based on pre-existing connections among the participants or with the research team. Table 1 overviews the sociolinguistic features pondered for selecting the subjects.

Table 1.

Sociolinguistic aspects of individuals.

In terms of statistics, 17 subjects are Mexicans and 11 are Mexican-Americans. This equals to 60.7% and 39.3%, respectively. The average age was 24 years. Both sexes represented 50% for women and 50% for men, a sex-balanced sampling. All subjects have Spanish as L1 and English as L2. Regarding English competence, six subjects have C1 (21.4%), seventeen B2 (60.7%), and five B1 (17.9%) according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001).2 The subjects required a minimum high school education, residing in Tijuana and being third generation of Tijuana heritage with both parental lineages born in the city. These criteria do not aim to represent the full sociolinguistic landscape of Tijuana; rather, they define a focused subsample of young adult bilinguals actively engaged in cross-border linguistic environments. The goal is to examine how English borrowings behave phonologically within this specific demographic, rather than to generalize across the entire speech community.

The participants were recruited using the sociolinguistic approach Friend-of-a-friend (Milroy & Gordon, 2003). In sociolinguistic studies, this approach promotes natural (spontaneous) interaction by reducing the perception from the investigators as external individuals during the conversations. Importantly, these interactions were not structured interviews or elicitation tasks. Instead, the investigators initiated the topics and occasionally stated follow-up questions to maintain the dynamic of interactions. Prior to the audio recordings, the investigators requested the consent of the subjects. By focusing on natural speech, the study documents the vowel realizations as natural features of real-time language use in Tijuana. All subjects granted their consent to be recorded. The audio quality was ensured by using a clip-on microphone positioned close to the subject’s mouth connected to a Sony ICD-UX570 voice recorder. The conversations lasted between 90 min and three hours. After the recordings, the participants were informed about the scientific objectives of the study.

After the audio recordings, the Anglicisms were initially identified perceptually by two trained researchers. Each token was annotated independently and any discrepancies were resolved through joint listening sessions. Although no interrater reliability was formally computed, a consensus was reached for all cases prior to acoustic analysis. Importantly, the perceptual identification served only as a preliminary filter. All subsequent classifications were based on acoustic measurements (F1 and F2) extracted with Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 2023) and evaluated using Euclidean distance metrics. This methodology ensures that final categorization relies on quantifiable phonetic data rather than subjective auditory judgment. For the specific selection of the Anglicisms, we excluded expressions (e.g., very nice or you know) and morphologically hybrid forms (e.g., baika or wachar). Furthermore, we intentionally excluded Anglicisms containing phonemic diphthongs (e.g., host /hoʊst/ or fake /feɪk/) from the analysis. This allowed us to focus on stable monophthongal realizations to ensure greater comparability across tokens by reducing variation from dynamic formant transitions. Unfortunately, it also limits representativeness—particularly for mid and back vowels like [o]—in which, items like host, may have revealed how Spanish–English bilinguals adapt phonemic diphthongs by simplifying them to monophthongs. Nevertheless, we considered words with digraphs realized as monophthongs (e.g., clean ([klin]) or loop ([lup]). All Anglicisms were monosyllabic structures. These syllabic structures were chosen for their acoustic clarity and prosodic consistency that allowed precise analyses of vowel formants (F1 and F2) and minimized prosodic interference. This approach is widely supported in acoustic and sociophonetic research as a reliable method for capturing stable formant measurements, especially for the cases of Spanish and English languages (Aubanel et al., 2015; Hagiwara, 1997; Jeske, 2012; Thomas, 2011).

We verified the lexical validation of each Anglicism using two cross-referencing online dictionaries: Nuevo Tesoro Lexicográfico de la Lengua Española (NTLLE, Real Academia Española, 2001) and Diccionario del Español de México (DEM, El Colegio de México, 2010). The NTLLE relates to general Spanish, whereas DEM pertains specifically to Mexican Spanish. The lexical verifications determined if Anglicisms are continuously used as English terms or they had lexically been integrated into Spanish. The tokens were included if (1) absent from both dictionaries, (2) present only in the NTLLE, or (3) exhibited English-like phonetic realizations despite the dictionary presence. Finally, we also considered theoretical formant values from English and Spanish literature based on the potential occurrences of the vowels involved in all Anglicisms. The theoretical average formants were drawn from acoustic research on Mexican Spanish (Grijalva et al., 2013, p. 4) and Californian English (Aiello, 2010, p. 301; Hagiwara, 1997, p. 656). We excluded Chicano English in order to present a relatively neutral representation of the Californian dialect.3 Table 2 represents the theoretical averages of both formants. Table 2 shows the theoretical average F1 and F2 values that will serve to be reciprocally compared with the data vowels.

Table 2.

Theoretical F1 and F2 average values from English and Spanish vowels.

Importantly, we maintained both /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ as distinct categories in Table 2 and our analysis of Californian English. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that these vowels often undergo merger in Southern Californian varieties. Aiello (2010, p. 301) explicitly notes that /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ are frequently realized within overlapping acoustic spaces among younger and urban speakers. This suggested a near-merger or neutralization of these categories. In contrast, Hagiwara (1997) did not list /ɔ/ as a separate category in his vowel inventory, which may exhibit an already consolidated low-back vowel system. Nonetheless, we keep both /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ as theoretical targets to observe whether bilingual speakers in Tijuana preserve, neutralize, or show gradient behavior among these vowels. This decision supports our broader aim to document possible variation and continuous variation in loanword adaptations.

2.1.2. Acoustic Analyses

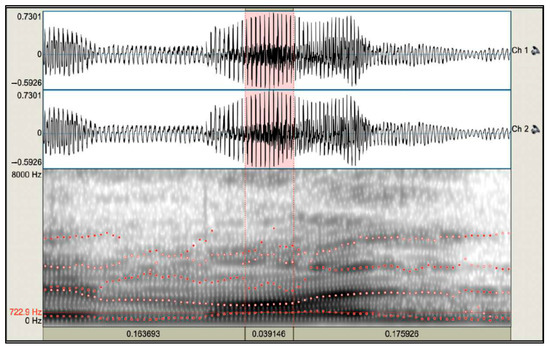

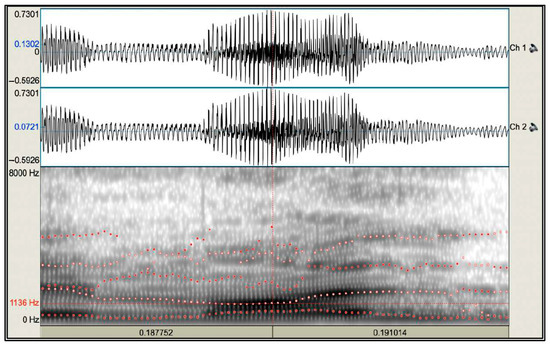

The audio files were segmented and specified to the target words. We measured the F1 and F2 of each token with Praat. Figure 1 and Figure 2 present the average of both formants for [ɔ] in mall. The vowel boundaries were manually identified using spectrogram inspection, waveform cues and auditory confirmation. The onset was defined by the emergence of periodic energy and visible formant structure, while the offset was marked by the reduction or interruption of these features due to the following consonant. These boundaries guided the selection of the midpoint frame, a practical method in sociophonetic studies (e.g., Thomas, 2011, p. 112). The “Get First Formant” and “Get Second Formant” functions in Praat were used to extract vowel formants. In Figure 1 and Figure 2, the midpoint frames are highlighted in red in the lower left corner for visual reference. Notably, the spectrograms in Figure 1 and Figure 2 display 8000 Hz just for visualization. In order to ensure accuracy, we adjusted the formant ceiling settings based on the speaker gender: 5500 Hz for males and 6000 Hz for females, following the Praat guidelines (Boersma & Weenink, 2023). We applied this process to all Anglicisms.

Figure 1.

Spectrogram and wave form of mall indicate the F1 of [ɔ] at 722 Hz. Red dots mark formant values and red dashed lines delimit the [ɔ] segment, highlighted in pink.

Figure 2.

F2 of 1136 Hz of [ɔ] in mall, red dots mark formant values.

The extracted average F1 and F2 values for each token represent the acoustic realization of vowels in spontaneous speech. These measurements were compiled into a dataset for further analysis. As an illustration, the realization of [ɔ] in mall showed an F1 average of 722 Hz and an F2 average of 1136 Hz. Importantly, these formant values are treated as part of a distributional continuum rather than discrete phonemic points that may exhibit the variability inherent in natural speech. Therefore, the acoustic similarity in the F1-F2 space between the dataset vowels was assessed and compared with the theoretical vowels based on the Euclidean distance; considering specifically their linear differences in hertz. We applied a 50 Hz threshold to assess perceptual distinctiveness between vowels by following studies indicating that formant differences below this level are typically not perceptually salient (Pols et al., 1973, p. 100); an approach particularly adopted in acoustic studies to assess overlap or phonetic continuous variation (Labov et al., 2006, pp. 36–38).

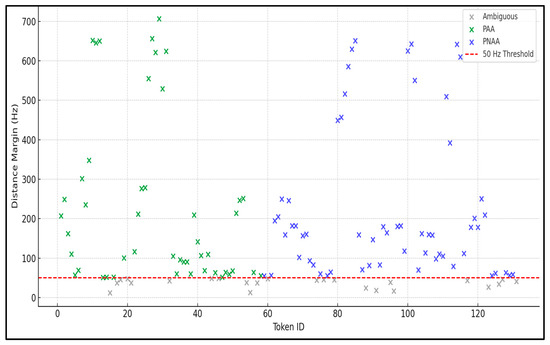

A vowel was classified as PAA if its Euclidean distance to the Spanish vowel was less than 50 Hz, indicating its close phonetic similarity. Conversely, a token was classified as PNAA if its distance to Spanish exceeded 50 Hz, but it displayed a closer distance to the English vowel, less than 50 Hz. For instance, the vowel [ɔ] in mall exhibited average formant values of F1: 722 Hz and F2: 1136 Hz (Figure 1 and Figure 2), compared to English /ɔ/ (F1: 632 Hz, F2: 1172 Hz) and Spanish /o/ (F1: 606 Hz, F2: 1012 Hz). Based on Euclidean distance calculations, the dataset vowel was 47 Hz away from the English /ɔ/ and 159 Hz from the Spanish /o/. Henceforth, the proximity to the English target vowel than the Spanish target vowel (47 Hz versus 159 Hz) classified mall as a PNAA.4 Beyond the primary PAA/PNAA classifications, we identified tokens that did not clearly match with either vowel space. These tokens were classified as ‘Both’ when the Euclidean distance to both targets was under 50 Hz or when formants exhibited split alignment (e.g., F1 closer to Spanish, F2 closer to English). These cases suggest intermediate or overlapping realizations that characterize gradient bilingual productions (Best, 1995; Best & Tyler, 2007). Tokens exceeding the 50 Hz threshold in a less systematic manner—falling near, but not within, either vowel space—were labeled as ‘Ambiguous.’ These added classifications account for acoustic variability and the nuanced nature of bilingual speech. The complete results are visualized in Figure 3 and detailed in Appendix A. Although we did not compute a single difference score (e.g., distance to English—distance to Spanish) for plotting, this contrast between the two distances can be interpreted as a ‘distance margin’.

Figure 3.

Distance margins show the proximity of each token to Spanish vowels (positive = PAA) or English vowels (negative = PNAA) targets. Dashed lines at ±50 Hz mark the perceptual threshold for classification.

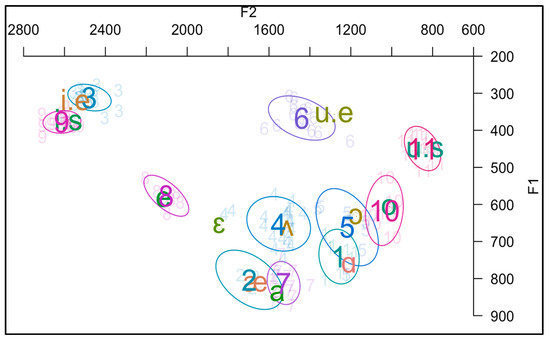

Finally, consistent with sociophonetic research (Escudero, 2005), our findings suggest that bilingual speakers frequently exhibit gradient phonetic integration rather than categorical vowel substitution. In order to visualize these patterns, we used R (R Core Team, 2023) and the phonR package (McCloy, 2016/2023) to generate a general F1 × F2 vowel plot with ellipses to capture within-category variation and alignments with Spanish or English vowel targets.

3. Results

This section presents the primary results from the acoustic analysis of the 131 monosyllabic Anglicism tokens across the 33 lexical items. Only tokens with a minimum of three occurrences were included in the analyses.5 Their frequency ranged from three to six instances per word. Furthermore, the results are organized in three dimensions: (1) the Euclidean distance margin between each vowel token and its theoretical targets in Spanish and English; (2) the frequency distribution of Anglicisms and their associated vowel realizations; and (3) the dispersion of vowel tokens are visualized in a general F1 × F2 plot. Together, the analyses empirical foundation for classifying tokens as Phonetically Adapted Anglicisms (PAA), Phonetically Non-Adapted Anglicisms (PNAA), or intermediate categories.

3.1. The Distance Margin Between Spanish and English Target Tokens

In order to assess phonetic configurations, we calculated the Euclidean distance between each vowel token and its Spanish and English targets in the F1–F2 space. A distance margin—defined as the difference between the distance to Spanish and the distance to English—indicates the relative proximity to either L1 or L2 categories. Positive values indicate greater proximity to Spanish vowels (PAA) and negative values relate to English vowels (PNAA). The zero line represents the midpoint between targets, with ±50 Hz dashed lines denoting the perceptual distinctiveness threshold. Values are visualized in Figure 3.

The results in Figure 3 demonstrate that vowel tokens classified as Phonetically Adapted Anglicisms (PAA) (green) and Phonetically Non-Adapted Anglicisms (PNAA) (blue) consistently exhibit distance margins exceeding 50 Hz. This indicates a clear acoustic separation between Spanish and English vowel targets. Such margins suggest that listeners are likely to perceive these categories as distinct, given that the acoustic differences exceed established perceptual discrimination thresholds. In contrast, ambiguous tokens, plotted in gray, cluster below the 50 Hz threshold, exhibiting minimal spectral separation and increasing the likelihood of perceptual confusion or misclassification. Figure 3 also includes several cases of vowel realizations that do not show significant distinctions. For instance, cool, mood, gym, tip(s), trip, bleach, cheers, weed, weird were classified as both since they presented acoustic properties that related both languages. The vowel in these cases presented distance of <50 Hz that also present ambiguities for their classification, particularly considering previous studies where there is no distinction between high vowels (Escudero, 2005). Notably, other occurrences of the same Anglicisms exhibited a combination of both formants from both languages. In this case, some presented F1 from Spanish and F2 from English and vice versa. Similarly, the Anglicisms crush, flush, and must showed sub-threshold differences, which is likely due to challenges Spanish speakers face in perceiving and producing the English vowel [ʌ], despite L2 proficiency (Baigorri et al., 2018). These distributional patterns offer critical insight into bilingual phonetic behavior in contact settings, where speakers navigate between two competing vowel systems. In such contexts, cross-linguistic influence often results in blurred phonemic boundaries, producing intermediate or ambiguous vowel realizations. This aligns with previous findings suggesting that perceptual and articulatory proximity between L1 and L2 categories can lead to category assimilation; whereby, bilingual speakers generate merged or near-merged vowel realizations within a shared acoustic space (Flege, 1995). The observed patterns support a gradient, usage-based model of bilingual phonetic production, in which acoustic distinctiveness plays a central role in shaping perceptual outcomes (Escudero, 2006). In total, 20 vowel tokens were classified as ‘Ambiguous’.

3.2. The Frequency of the Anglicisms and the Vowels

Table 3 overviews the list of Anglicisms along with their corresponding vowel realizations. The dataset vowels were classified according to their alignment with either Spanish or English phonological targets. As noted earlier, only Anglicisms with a minimum of three occurrences were included in the analysis, totalizing 131 vowel tokens. This frequency-based inclusion criterion allowed for the examination of whether certain input vowels were more likely to undergo phonetic adaptation or preservation based on the distribution of their realizations across tokens.

Table 3.

Overview of the Anglicisms and their frequencies.

According to Table 3, the most frequent Anglicisms in the dataset were cool, gym, plus, sad, and tip(s), each occurring six times. These were followed by boss, mall(s), mood, trip, and weird with five occurrences. Notably, individual phonological categories often displayed asymmetric realizations—being more frequently classified as either Phonetically Non-Adapted Anglicisms (PNAA) or Phonetically Adapted Anglicisms (PAA), depending on the lexical item. As an example, the vowel [ʌ] occurred in bun, bundle, crush, flush, fuck, and must, but it not occur in plus, which emerged as [u] in all cases. Oppositely, cash, (to) hack, sad, staff predominantly adapted /æ/ to [a], except for match. These exceptions (e.g., plus [plʌs] → [u], PAA; match [mætʃ], PNAA) suggest that vowel identity alone does not reliably predict phonetic adaptation outcomes. Additional variation was observed among words containing the grapheme <o>. The vowels /ɑ/ and /o/ showed a balanced distribution: boss and spots were realized with [ɑ], while shot(s) and top aligned with [o]. This pattern may exhibit subtle orthographic influence on production, despite the fact that these tokens were not elicited through reading tasks. The most frequent sounds [i] in bleach, clean, cheers, gym, tip(s), trip, weed, and weird and [u] in dude, loop, cool, mood, and plus represented the largest lists of Anglicisms, reinforcing the notion that vowel adaptation in Anglicisms follows a gradient continuum that is shaped by lexical, phonetic, and sociolinguistic variables (Flege, 1995, pp. 264–265). Finally, the vowel realization percentages across the dataset were as follow: [ɑ] (6.8%), [ʌ] (15.2%), [ɔ] (6.8%), [æ] (2.2%), [a] (13.7%), [e] (5.3%), [o] (5.3%), [i] (26.7%) and [u] (17.5%). Generally, the most frequent sounds are [i] (35) and [u] (23), followed by [ʌ] (20) and [a] (18).

3.3. The Vowel Plotting

Figure 4 exhibits the F1 × F2 frequency values that visualize the distribution of the vowel realizations generated for all Anglicism tokens. Each token was mapped relative to its theoretical Spanish and English vowel targets. English categories are labeled as /ɑ/, /æ/, /ʌ/, /ɛ/, /ɔ/, /i.e/ and /u.e/; whereas Spanish vowels are labeled as /a/, /e/, /o/, /i.s/ and /u.s/ with ‘e’ indicating English and ‘s’ indicating Spanish origin. Each numbered cluster in the plot corresponds to a distinct vowel realization derived from specific lexical items. For instance, cluster 3 includes Anglicisms, such as clean, cheers, weird, and weed, all of which originate from the English input vowel /i/ and were realized phonetically as [i]. The colored ellipses represent one standard deviation from each cluster centroid, providing a visual indication of the consistency and dispersion of vowel realizations within each category. These ellipses show the central tendency and variation of each vowel across tokens. The clusters (ellipses) are labeled as follows: ‘1’ ([ɑ]), ‘2’ ([æ]), ‘3’ ([i]), ‘4’ ([ʌ]), ‘5’ ([ɔ]), ‘6’ ([u]), ‘7’ ([a]), ‘8’ ([e]), ‘9’ ([i]), ‘10’ ([o]) and ‘11’ ([u]).

Figure 4.

General plotting of all dataset and theoretical vowels. Ellipses indicate the tokens clusters and the English categories are labeled as follows: /ɑ/, /æ/, /ʌ/, /ɛ/, /ɔ/, /i.e/ and /u.e/; whereas Spanish vowels are labeled as /a/, /e/, /o/, /i.s/ and /u.s/ with ‘e’ indicating English and ‘s’ indicating Spanish origin.

Several vowel clusters in the F1 × F2 plot show clear alignment with either Spanish or English theoretical targets. Clusters ‘2’ ([æ]) from English and clusters ‘8’ ([e]), ‘9’ ([i]), ‘10’ ([o]), and ‘11’ ([u]) from Spanish seem to present adaptations into the native Spanish phonological system. Conversely, clusters ‘1’ ([ɑ]), ‘3’ ([i]), ‘4’ ([ʌ]), and ‘5’ ([ɔ])—all derived from English input—along with cluster ‘7’ ([a]) from Spanish, show near-target realizations that suggest the presence of gradient categories as a potential indicator of an inter-phonological system emerging from language contact. Cluster ‘6’ ([u]), associated with English input, displayed the clearest phonetic divergence from Spanish categories, exhibiting a lack of adaptation. In addition, the size and shape of the ellipses provide valuable insight into intra-category variability. For instance, clusters ‘4’ ([ʌ]) and ‘6’ ([u]) exhibited broader dispersions that suggested greater variability in how those vowels are produced. This variability may be influenced by differences in speaker background, degree of exposure to English, sociolinguistic awareness or lexical entrenchment. Contrarily, clusters ‘3’ ([i]) and ‘11’ ([u]) show tighter distributions, which may indicate a higher degree of phonological integration or stabilization. These spatial patterns support the Euclidean distance findings and reinforce the interpretation that loanword adaptation operates along a gradient continuum, rather than through categorical substitution. Moreover, they highlight that individual lexical items may exhibit different degrees of phonetic stability depending on their frequency, functional load, lexical status, or even intra-speaker conditions (Flege, 1995).

The results across Figure 3 and Figure 4 demonstrate that vowel realizations in Anglicisms tend to follow two primary phonetic trajectories: clear adaptations to Spanish phonological categories or preservations to English phonetic features. As shown in Figure 3, many vowel tokens were unambiguously classified as either Spanish or English based on their marginal proximity to theoretical targets. However, other realizations exhibited classification ambiguity, likely attributable to intra-speaker variation or to inter-phonological influences arising from sustained language contact. These ambiguous cases present patterns of misperception and misproduction, particularly among phonological categories that lack a direct equivalent in the speaker’s L1. While certain vowel realizations—such as [i], [u], [ʌ], and [a]—were more frequent than others, their distribution does not align uniformly with a single phonological system. For example, although [ʌ] appeared 20 times (e.g., bun, bundle, crush, flush, fuck, must), it was preserved in an English-like form, whereas plus—which might be expected to follow the same pattern—was consistently realized as [u], which suggests Spanish adaptation. This variability is also evident in the numeric vowel clusters and their respective dispersions. The ellipse plots indicate that tokens derived from the same input vowel can yield diverse phonetic outputs. For instance, while [u] was frequent, it did not consistently align with the English /u/ target. This reveals that frequency alone does not predict adaptation direction. Overall, the Anglicism phenomenon in Tijuana appears to involve a complex interaction of linguistic and extralinguistic factors that include language contact, language proficiency, intra-speaker factors, usage frequency, orthographic transparency, and lexical entrenchment. Bilingual speakers appear to engage with both nativization-through-perception and nativization-through-production mechanisms that result in a flexible, gradient system. Therefore, the observed dispersion patterns, reinforced by the Euclidean distance results, support a usage-based model of loanword adaptation that accommodates intra-category variability and phonetic flexibility.

4. The Importance of Proposing Two Phonetically Grounded Corpora

The development of two phonetically based corpora—Phonetically Adapted Anglicisms (PAA) and Phonetically Non-Adapted Anglicisms (PNAA)—constitutes an empirical and methodological contribution to the study of bilingual phonetics, interlanguage phonology and contact-induced lexical variation. These corpora are anchored in acoustic evidence derived from vowel nuclei, which are well-suited due to their prosodic stability and sensitivity to phonological integration. As demonstrated in Figure 3 and Figure 4, and Table 3, vowel realizations frequently align with either Spanish or English targets. However, a significant number of vowel tokens occupy ‘both’ and ‘ambiguous’ positions (mostly [i] and [u]).6 These realizations cannot be fully accounted by categorical frameworks or orthographic proxies alone. Instead, they reveal a nuanced and gradient continuum of phonological integrations that exhibit both segmental and lexical variability. Accordingly, the adaptation patterns in loanwords are not merely postulated theoretically but are quantified acoustically. This allows for a data-driven typology of borrowing that aligns more accurately with naturalistic bilingual speech. This supports the idea of variation in phonetic integration rather than binary adaptation; it reinforces research on bilingual vowel perception (Jeske, 2012; Baigorri et al., 2018). Additionally, this segmental-level analysis is innovative; since it captures intra-word phonetic variability it overlooks the complexity of bilingual speech. The corpora further expose the limitations of existing models such as Loanword Phonology (Calabrese & Wetzels, 2009), binary dichotomy of production-based versus perception-based nativization. The former model cannot fully account for the inconsistent realizations of the same phoneme across different Anglicisms (e.g., /ʌ/ realized as [ʌ] in crush versus [u] in plus). Instead, the observed patterns stipulate empirical validation for two frameworks such as the Perceptual Assimilation Model (Best, 1995), which explains how L2 sounds are perceptually filtered through L1 categories and the Speech Learning Model (Flege, 1995), which accounts for speaker-specific variation based on age, exposure, and usage frequency. Importantly, the construction of two phonetically defined corpora represents a methodological innovation. According to current research, no existing bilingual phonetic corpus explicitly targets monosyllabic Anglicisms categorized through empirical acoustic criteria. Unlike elicited or controlled data, this dataset is drawn from natural interactions that potentially enhance its ecological validity and relevance for sociophonetic research.

5. Discussion

The acoustic analyses of vowel formants in this study reveal that the Anglicisms used in spontaneous speech in Tijuana exhibit systematic, yet variable phonetic realizations. Despite the limited quantity of the data, two distinct patterns emerged: Phonetically Adapted Anglicisms (PAA), which approximate Spanish vowel targets and Phonetically Non-Adapted Anglicisms (PNAA), which preserve features of English vowels. These patterns are empirically supported by Euclidean distance calculations (Figure 3), vowel dispersion plots clustered with ellipses (Figure 4), and categorical classification based on acoustic measurements (Appendix A). Important to recall is the data challenge binary models of phonological integration. In this respect, the vowel realizations reveal a gradient continuum that opposes the perception–production distinctions that are central to traditional Loanword Phonology frameworks (Calabrese & Wetzels, 2009). For instance, several Anglicisms that contained the same input vowel (e.g., match [mætʃ] vs. cash [kaʃ]) exhibited divergent realizations. This suggested that uniform rules of nativization are insufficient. Instead, the findings matched more closely with usage-based and perceptually grounded models, such as the Speech Learning Model (Flege, 1995) and the Perceptual Assimilation Model (Best, 1995), since they account for variability in bilingual production as a function of exposure, frequency, and perceptual similarity. One notable factor observed in the data is the indirect influence of orthography. While not directly manipulated in this study, the consistent realization of [a] in Anglicisms, such as, cash, dark, sad, and staff—all of which contain the grapheme <a>—suggests that spelling may guide phonetic adaptation. This influence is especially plausible in a language like Spanish, which features high grapheme–phoneme transparency (Lallier et al., 2014). Such findings are consistent with prior research highlighting the role of orthography in bilingual phonetic production (Nuñez-Nogueroles, 2017; Shea, 2021). Nevertheless, orthographic influence alone cannot explain all variations. For instance, match was realized in an English-like manner as [mætʃ], despite the presence of <a>. Similarly, while bun, bundle, crush, flush, fuck, and must consistently preserved the English vowel [ʌ], plus deviated from this pattern, surfacing as [u]. These discrepancies point to the influence of additional factors—such as lexical frequency, sociolinguistic indexicality, and phonological salience—in shaping the adaptation process (Bybee, 1999; Escandón, 2019).

Furthermore, a subset of tokens (bleach, cheers, clean, gym, tip(s), trip, weird, cool, dude, loop, mood, and plus) exhibited formant values near the 50 Hz threshold. These tokens were classified as ‘Both’ when their presented values were close to Spanish and English, but they were also classified as ‘Ambiguous’ when they exhibited value formants different from both languages. These cases denote intermediate realizations which support the potential characterization of contact varieties by adopting a tri- or even four-level classification model beyond the traditional binary scheme. This is particularly relevant for high vowels, such as [i] and [u], which frequently exhibited acoustic overlap. The overlaps in both L1 and L2 categories often lead to indistinct mapping in bilingual speech (Baigorri et al., 2018; Escudero, 2005; Flege et al., 1997). The latter was especially evident in the broad dispersions of clusters associated with [ʌ] and [u], as compared to the more stabilized clusters for [i] or [a] (see Figure 4). The decision to group /i/–/ɪ/ and /u/–/ʊ/ was guided by prior studies showing that Spanish-dominant bilinguals typically neutralize these contrasts and map both English pairs to their nearest Spanish counterparts (Baigorri et al., 2018, p. 79; Escudero, 2005, p. 149; Flege et al., 1997, p. 459). This pattern was evident in our dataset, where high vowel tokens frequently clustered in shared acoustic regions. This underscores the importance of considering unified vowel categories to analyze spontaneous bilingual speech. While future work may explore fine-grained distinctions in perception-based or elicited tasks, the present findings exhibit the patterns commonly found in natural speech environments. In contrast, we maintained /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ as separate categories in our analysis of Californian English despite the evidence of an ongoing merger of these vowels in Southern Californian varieties. Aiello (2010, p. 301) notes that these vowels often overlap acoustically, particularly among younger and urban speakers, indicating a near-merger. Hagiwara (1997), in turn, omits the category /ɔ/ entirely from his inventory, suggesting a consolidated low-back vowel space. The data in this study show variation along a continuum; some tokens match more closely with /ɑ/ or /ɔ/ and others occupy intermediate spaces. Henceforth, we maintained both categories as theoretical targets in order to examine whether bilingual speakers in Tijuana preserve, neutralize or demonstrate continuous variation across these vowel types. This choice aligns more with the broader objective of the study to capture phonetic gradience and inter-speaker variability in vowel realization.

Additionally, segmental contexts also appear to play a meaningful role in shaping vowel realizations. Regarding this, words such as, gym, cheers, and weird exhibited coarticulatory effects driven by the presence of non-Spanish phonemes such as [ʒ] or [ɹ]. The articulatory and acoustic properties of these segments—particularly when they follow or precede the vowel—may account for formant centralization, lengthening, or spectral shifts. These effects are consistent with prior work on segmental coarticulation in both monolingual and bilingual speech. As Recasens (2015, p. 1409) noted, articulatory overlap and the influence of neighboring consonants significantly shape vowel space and duration. Accordingly, this study acknowledges that vowel realizations are not determined by vowel quality alone but are also shaped by local phonetic environments, especially adjacent consonants. Future iterations of the vowel-based classification proposed here could benefit from explicitly incorporating such segmental effects, particularly given their relevance in spontaneous bilingual corpora. Despite its contributions, the study recognizes several methodological limitations. The sample of 28 bilingual speakers provides rich phonetic data but may not exhibit the complete sociophonetic spectrum of the target population in Tijuana. The specific variables per speaker such as pitch, speech rate, and background noise—although methodologically controlled—may have influenced the properties of the formants. Moreover, while Euclidean metrics provided a replicable approach to classification, perceptual studies with human listeners or machine-learning classifiers may further enhance the precision of vowel categorization.

Beyond their classificatory purpose, the proposed corpora offer a multidimensional framework that integrates vowel formant values (F1–F2), lexical identity, token frequency and dispersion patterns. Grounded in segmental; rather than lexeme-level criteria, these corpora constitute a methodological contribution to both language contact research and corpus-based phonetic analyses. Interestingly, to our knowledge, this study provides the first corpora that systematically classify monosyllabic Anglicisms using vowel-level acoustic parameters derived from spontaneous bilingual speech for Mexican Spanish. Whereas most existing corpora are based on elicited or controlled data, our dataset presents naturalistic bilingual interactions that potentially enhance its validity and strengthen its applicability to sociophonetic and language contact studies. As such, the corpora provide a robust foundation for examining vowel behavior across lexical items and speaker profiles. They are particularly well-suited for research on phonetic convergence, lexical innovation, and frequency effects in bilingual contexts—especially in complex contact zones such as Tijuana.

6. Conclusions

This study contributes to the fields of Loanword Phonology and Corpus Phonetics by demonstrating that phonetic adaptation in bilingual speech—specifically in the case of Anglicisms in Tijuana—is neither a fixed nor a binary process. Instead, it denotes a dynamic interplay of linguistic constraints, cognitive mechanisms, and sociolinguistic variables (e.g., lexical frequency and exposure to English). Notably, speakers with higher levels of exposure to English—regardless of nationality—were more likely to produce Anglicisms with English-like phonetic features, rather than conforming to Spanish grapheme–phoneme correspondences, as noted by Bäumler (2024, p. 15). This finding also reinforces the role of individual linguistic experience in shaping vowel adaptation and highlights the need for models of bilingual phonetics that are responsive to sociolinguistic context and patterns of language use. In addition, the acoustic analyses further revealed that many Anglicism realizations occupy intermediate positions within the F1–F2 acoustic space that offer empirical support for the view that phonetic adaptation in contact settings operates along a gradient continuum rather than through categorical shifts (Best & Tyler, 2007; Escudero, 2006; Flege, 1995). Similarly, this finding challenges traditional models of loanword integration and aligns more closely with usage-based and experience-driven frameworks such as the Speech Learning Model (Flege, 1995) and the Perceptual Assimilation Model (Best, 1995).

In response to these findings, we developed two phonetically grounded corpora—Phonetically Adapted Anglicisms (PAA) and Phonetically Non-Adapted Anglicisms (PNAA)—based principally on Euclidean distance measurements and supported with vowel dispersion plots as well as formant measurements. These corpora provide a more empirically robust typology of loanword integration and are derived from spontaneous speech, a context in which Anglicisms occur sporadically yet authentically (Bäumler, 2024, p. 4). Hence, the study advances our understanding of how lexical innovation, phonological adaptation, and sociolinguistic factors converge in naturalistic contact settings. Taken together, these findings underscore the importance of integrating phonetic, lexical, and social dimensions when investigating language contact phenomena. The proposed corpora provide a replicable and empirically grounded resource for future research on bilingual phonetic convergence, lexical innovation, and typologies of loanword integration in dynamic contact settings such as Tijuana.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R.P.-R.; methodology, R.R.P.-R., C.I.G.-B. and N.E.V.-M.; validation, R.R.P.-R., C.I.G.-B. and N.E.V.-M.; formal analysis, R.R.P.-R., C.I.G.-B. and N.E.V.-M.; investigation, R.R.P.-R., C.I.G.-B. and N.E.V.-M.; data curation, R.R.P.-R. and N.E.V.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.P.-R., C.I.G.-B. and N.E.V.-M.; writing—review and editing, R.R.P.-R., C.I.G.-B. and N.E.V.-M.; visualization, R.R.P.-R., C.I.G.-B. and N.E.V.-M.; supervision, R.R.P.-R.; project administration, R.R.P.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We informed about the anonymization and storage of the data to the subjects; they were eventually informed about the scientific objectives of the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from the subjects. Verbal consent was obtained rather than written as a procedure approved by the Ethics Committee Board of omitted. The authors committed themselves to follow legal stipulations by individually signing the confidentiality commitment letters submitted with the present study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Facultad de Idiomas Tijuana from Universidad Autónoma de Baja California for granting the time and academic freedom to conduct this research. Additionally, this paper is based on work that was originally presented at II Congreso International CROS held in Brussels, Belgium on 7–8 February, 2024. This journal article expands upon that work with specific and additional analyses and findings. We extend our sincere gratitude to all participants for their valuable contributions to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The appendix provides details of the analyzed Anglicisms considering a list, frequency, formants F1 and F2 and their Euclidean distance comparison from Spanish and English. The head titles in the columns from the third indicate the following: ‘F1_T’ (F1 token), ‘F2_T’ (F2 token), ‘F1_S’ (theoretical F1 from Spanish), ‘F2_S’ (theoretical F2 from Spanish), ‘F1_E’ (theoretical F1 from English) ‘F2_E’ (theoretical 21 from English) ‘D_S’ (distance from Spanish) and ‘D_E’ (distance from English). Recall that ‘Both’ indicates tokens acoustically close to both Spanish and English targets (distance < 50 Hz or mixed formant alignment). ‘Ambiguous’ refers to tokens with inconsistent proximity—above-threshold differences—or unclear alignment with either vowel category.

| Token ID | Anglicism | F1_T | F2_T | F1_S | F2_S | F1_E | F2_E | D_S | D_E | Differences | Classification |

| 1 | blend | 586 | 2078 | 585 | 2115 | 655 | 1844 | 37.013511046643494 | 243.9610624669437 | 206.94755142030021 | PAA |

| 2 | blend | 571 | 2100 | 585 | 2115 | 655 | 1844 | 20.518284528683193 | 269.4290259047826 | 248.9107413760994 | PAA |

| 3 | blend | 568 | 2053 | 585 | 2115 | 655 | 1844 | 64.28841264178172 | 226.38462845343543 | 162.0962158116537 | PAA |

| 4 | cash | 846 | 1483 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 75.32595834106593 | 185.776747737708 | 110.45078939664208 | PAA |

| 5 | cash | 780 | 1555 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 59.07622195096772 | 116.09048195265622 | 57.0142600016885 | PAA |

| 6 | cash | 864 | 1578 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 32.01562118716424 | 101.21264743103995 | 69.19702624387571 | PAA |

| 7 | dark | 776 | 1576 | 839 | 1558 | 762 | 1209 | 65.52098900352466 | 367.26693289758606 | 301.7459438940614 | PAA |

| 8 | dark | 832 | 1497 | 839 | 1558 | 762 | 1209 | 61.40032573203501 | 296.3848849047468 | 234.98455917271178 | PAA |

| 9 | dark | 827 | 1565 | 839 | 1558 | 762 | 1209 | 13.892443989449804 | 361.8853409576022 | 347.99289696815237 | PAA |

| 10 | dude | 389 | 1135 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 305.3604427557702 | 347.476617918386 | 42.11617516261583 | Both |

| 11 | dude | 378 | 1149 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 321.4000622277475 | 332.66349363884217 | 11.263431411094643 | Both |

| 12 | dude | 388 | 1133 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 303.608300281794 | 349.3780187705002 | 55.76971848870619 | Ambiguous |

| 13 | gym | 359 | 2551 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 32.31098884280702 | 42.2965719651132 | 9.985583122306181 | Both |

| 14 | gym | 363 | 2602 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 22.47220505424423 | 72.47068372797375 | 49.99847867372952 | Both |

| 15 | gym | 336 | 2591 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 36.40054944640259 | 48.84669896727925 | 12.44614952087666 | Both |

| 16 | gym | 382 | 2560 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 23.706539182259394 | 66.49060083951716 | 42.784061657257766 | Both |

| 17 | gym | 388 | 2552 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 33.61547262794322 | 71.25307010929424 | 37.63759748135102 | Both |

| 18 | gym | 389 | 2560 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 27.65863337187866 | 73.348483283569 | 45.68984991169033 | Both |

| 19 | hack | 864 | 1549 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 26.570660511172846 | 127.23600119463045 | 100.6653406834576 | PAA |

| 20 | hack | 793 | 1572 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 48.08326112068523 | 96.317184344228 | 48.23392322354277 | Ambiguous |

| 21 | hack | 802 | 1584 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 45.221676218380054 | 82.87339742040264 | 37.651721202022586 | Ambiguous |

| 22 | nerd | 594 | 2033 | 585 | 2115 | 655 | 1844 | 82.49242389456137 | 198.600100704909 | 116.10767681034764 | PAA |

| 23 | nerd | 624 | 2097 | 585 | 2115 | 655 | 1844 | 42.95346318982906 | 254.8921340488953 | 211.93867085906624 | PAA |

| 24 | nerd | 528 | 2205 | 585 | 2115 | 655 | 1844 | 106.53168542738823 | 382.6878623630491 | 276.1561769356608 | PAA |

| 25 | nerd | 564 | 2149 | 585 | 2115 | 655 | 1844 | 39.96248240537617 | 318.2860348805772 | 278.323552475201 | PAA |

| 26 | plus | 464 | 912 | 451 | 836 | 663 | 1512 | 77.10382610480494 | 632.140016135666 | 555.036190030861 | PAA |

| 27 | plus | 410 | 857 | 451 | 836 | 663 | 1512 | 46.06517122512408 | 702.163798554155 | 656.0986273290309 | PAA |

| 28 | plus | 408 | 879 | 451 | 836 | 663 | 1512 | 60.81118318204309 | 682.432414236018 | 621.6212310539748 | PAA |

| 29 | plus | 433 | 814 | 451 | 836 | 663 | 1512 | 28.42534080710379 | 734.917682465186 | 706.4923416580822 | PAA |

| 30 | plus | 428 | 931 | 451 | 836 | 663 | 1512 | 97.74456506629922 | 626.7264155913647 | 528.9818505250655 | PAA |

| 31 | plus | 508 | 847 | 451 | 836 | 663 | 1512 | 58.05170109479997 | 682.8250141873832 | 624.7733130925833 | PAA |

| 32 | sad | 734 | 1540 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 106.53168542738823 | 149.25146565444507 | 42.719780227056845 | Ambiguous |

| 33 | sad | 820 | 1492 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 68.6804193347711 | 174.1034175425629 | 105.4229982077918 | PAA |

| 34 | sad | 791 | 1560 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 48.041648597857254 | 108.4665847162157 | 60.42493611835845 | PAA |

| 35 | sad | 805 | 1516 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 54.037024344425184 | 150.26975743641833 | 96.23273309199314 | PAA |

| 36 | sad | 793 | 1511 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 65.76473218982953 | 156.41611170208776 | 90.65137951225823 | PAA |

| 37 | sad | 779 | 1481 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 97.6165969494942 | 188.2817038376273 | 90.66510688813311 | PAA |

| 38 | shot(s) | 628 | 1114 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 104.34557968596465 | 164.2589419179364 | 59.913362231971746 | PAA |

| 39 | shot(s) | 623 | 1025 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 21.400934559032695 | 230.6013876801265 | 209.2004531210938 | PAA |

| 40 | shot(s) | 688 | 996 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 83.54639429682169 | 225.48835890129672 | 141.94196460447503 | PAA |

| 41 | staff | 818 | 1395 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 164.34719346554112 | 271.02951868754076 | 106.68232522199963 | Ambiguous |

| 42 | staff | 821 | 1574 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 24.08318915758459 | 92.26592003551474 | 68.18273087793014 | PAA |

| 43 | staff | 872 | 1488 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 77.38862965578342 | 187.21111078138497 | 109.82248112560156 | PAA |

| 44 | tip(s) | 362 | 2602 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 22.847319317591726 | 71.84010022264724 | 48.99278090505551 | Both |

| 45 | tip(s) | 370 | 2570 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 11.045361017187261 | 58.180752831155424 | 47.13539181396816 | Both |

| 46 | tip(s) | 322 | 2599 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 52.20153254455275 | 53.23532661682466 | 1.0337940722719097 | Both |

| 47 | tip(s) | 355 | 2567 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 21.2602916254693 | 43.41658669218482 | 22.156295066715522 | Both |

| 48 | tip(s) | 363 | 2604 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 24.351591323771842 | 74.02702209328699 | 69.675430769515145 | Ambiguous |

| 49 | tip(s) | 341 | 2612 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 43.139309220245984 | 70.22819946431775 | 27.08889024407177 | Both |

| 50 | top | 650 | 1094 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 93.05912099305473 | 160.52725625263767 | 67.46813525958294 | PAA |

| 51 | top | 526 | 1030 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 82.0 | 296.2043213729334 | 214.2043213729334 | PAA |

| 52 | top | 609 | 1002 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 10.44030650891055 | 257.40629362935164 | 246.9659871204411 | Ambiguous |

| 53 | top | 590 | 989 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 28.0178514522438 | 279.25615481131297 | 251.23830335906916 | PAA |

| 54 | trip | 355 | 2570 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 19.4164878389476 | 44.94441010848846 | 25.527922269540863 | Both |

| 55 | trip | 333 | 2584 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 38.118237105091836 | 41.23105625617661 | 3.1128191510847714 | Both |

| 56 | trip | 344 | 2590 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 28.460498941515414 | 51.62363799656123 | 23.163139055045814 | Both |

| 57 | trip | 351 | 2611 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 36.05551275463989 | 73.35529974037323 | 37.299786985733334 | Both |

| 58 | trip | 289 | 2708 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 151.17208737065187 | 164.40194646049662 | 13.229859089844751 | Both |

| 59 | bleach | 505 | 2454 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 184.6212338816963 | 209.30360723121808 | 24.682373349521782 | Ambiguous |

| 60 | bleach | 326 | 2518 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 77.42092740338364 | 29.410882339705484 | 48.01004506367816 | Both |

| 61 | bleach | 377 | 2508 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 73.24616030891995 | 71.02112361825881 | 2.225036690661142 | Both |

| 62 | boss | 721 | 1219 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 236.799493242701 | 42.20189569201838 | 194.59759755068262 | PNAA |

| 63 | boss | 714 | 1301 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 308.5206638136253 | 103.76897416858277 | 204.75168964504252 | PNAA |

| 64 | boss | 788 | 1224 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 279.4065138825507 | 30.01666203960727 | 249.38985184294344 | PNAA |

| 65 | boss | 726 | 1179 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 205.6428943581567 | 46.861498055439924 | 158.78139630271676 | PNAA |

| 66 | boss | 802 | 1328 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 371.8494318941472 | 125.54282137979854 | 246.30661051434865 | PNAA |

| 67 | bun | 589 | 1487 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 259.88651369395836 | 78.10889834071403 | 181.77761535324433 | PNAA |

| 68 | bun | 611 | 1502 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 234.77648945326703 | 52.952809179494906 | 181.82368027377214 | PNAA |

| 69 | bun | 632 | 1622 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 216.6679487141557 | 114.28473213863697 | 102.38321657551873 | PNAA |

| 70 | bun | 571 | 1575 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 268.5386378158644 | 111.50336317797773 | 157.03527463788663 | PNAA |

| 71 | bundle | 623 | 1432 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 250.06399181009647 | 89.44271909999159 | 160.62127271010488 | PNAA |

| 72 | bundle | 710 | 1491 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 145.3616180427282 | 51.478150704935004 | 93.88346733779319 | PNAA |

| 73 | bundle | 686 | 1580 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 154.5736070614903 | 71.78439941937245 | 82.78920764211784 | PNAA |

| 74 | cheers | 322 | 2549 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 58.52349955359813 | 5.830951894845301 | 52.69254765875283 | Ambiguous |

| 75 | cheers | 351 | 2525 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 59.464274989274024 | 39.96248240537617 | 19.501792583897853 | Both |

| 76 | cheers | 340 | 2534 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 56.302753041036986 | 25.942243542145693 | 30.360509498891293 | Both |

| 77 | clean | 301 | 2482 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 121.24768039018313 | 65.96969000988257 | 55.277990380300565 | Ambiguous |

| 78 | clean | 301 | 2577 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 70.11419257183242 | 34.88552708502482 | 35.2286654868076 | Both |

| 79 | clean | 324 | 2479 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 112.30761327710601 | 67.36467917239716 | 44.942934104708854 | Both |

| 80 | cool | 488 | 1191 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 356.9229608753127 | 318.2153358969363 | 38.70762497837637 | Both |

| 81 | cool | 451 | 1188 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 352.0 | 307.7092783781471 | 44.290721621852924 | Both |

| 82 | cool | 382 | 1175 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 345.950863563021 | 307.01954335188503 | 38.93132021113598 | Both |

| 83 | cool | 381 | 1454 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 621.951766618602 | 36.124783736376884 | 585.8269828822251 | Ambiguous |

| 84 | cool | 333 | 1479 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 653.737714989735 | 24.08318915758459 | 629.6545258321504 | Both |

| 85 | cool | 404 | 1099 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 267.1666146808018 | 384.88050093503045 | −117.71388625422867 | Ambiguous |

| 86 | core | 611 | 1360 | 606 | 1012 | 632 | 1172 | 348.0359176866664 | 189.16923639957952 | 158.86668128708686 | PNAA |

| 87 | core | 646 | 1125 | 606 | 1012 | 632 | 1172 | 119.87076374162301 | 49.040799340956916 | 70.82996440066609 | PNAA |

| 88 | core | 644 | 1201 | 606 | 1012 | 632 | 1172 | 192.78226059469267 | 31.38470965295043 | 161.39755094174225 | PNAA |

| 89 | core | 722 | 1144 | 606 | 1012 | 632 | 1172 | 175.72706109191037 | 94.25497334358543 | 81.47208774832494 | PNAA |

| 90 | crush | 681 | 1501 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 167.96725871431016 | 21.095023109728988 | 146.87223560458116 | PNAA |

| 91 | crush | 625 | 1818 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 336.7432256185713 | 308.3504499753487 | 28.392775643222592 | PNAA |

| 92 | crush | 656 | 1623 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 194.20092687729377 | 111.22050170719426 | 82.98042517009951 | PNAA |

| 93 | crush | 623 | 1517 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 219.85677155821242 | 40.311288741492746 | 179.54548281671967 | PNAA |

| 94 | flush | 665 | 1490 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 186.81541692269406 | 22.090722034374522 | 164.72469488831953 | PNAA |

| 95 | flush | 719 | 1572 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 120.81390648431164 | 82.07313811473277 | 38.74076836957887 | PNAA |

| 96 | flush | 744 | 1528 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 99.62429422585637 | 82.56512580987206 | 17.059168415984317 | PNAA |

| 97 | fuck | 643 | 1497 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 205.27298896834918 | 25.0 | 180.27298896834918 | PNAA |

| 98 | fuck | 619 | 1506 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 226.06193841511666 | 44.40720662234904 | 181.65473179276762 | PNAA |

| 99 | fuck | 690 | 1532 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 151.25144627407698 | 33.60059523282288 | 117.6508510412541 | PNAA |

| 100 | loop | 486 | 1191 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 356.72117963473937 | 317.3972274611106 | 39.323952173628754 | Both |

| 101 | loop | 465 | 1188 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 352.27829907617075 | 312.27071588607214 | 40.007583190098615 | Both |

| 102 | loop | 344 | 1224 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 402.48354003611126 | 257.3285837212804 | 145.15495631483088 | Ambiguous |

| 103 | mall(s) | 668 | 1125 | 606 | 1012 | 632 | 1172 | 128.89142717807107 | 59.20304046246274 | 69.68838671560833 | PNAA |

| 104 | mall(s) | 645 | 1217 | 606 | 1012 | 632 | 1172 | 208.67678356731494 | 46.84015371452148 | 161.83662985279346 | PNAA |

| 105 | mall(s) | 789 | 1222 | 606 | 1012 | 632 | 1172 | 278.54802099458544 | 164.76953601925328 | 113.77848497533216 | PNAA |

| 106 | mall(s) | 722 | 1136 | 606 | 1012 | 632 | 1172 | 206.6204249342257 | 47.07440918375928 | 159.5460157504664 | PNAA |

| 107 | mall(s) | 606 | 1347 | 606 | 1012 | 632 | 1172 | 335.0 | 176.92088627406318 | 158.07911372593682 | PNAA |

| 108 | match | 795 | 1667 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 117.5457357797381 | 19.026297590440446 | 98.51943818929765 | PNAA |

| 109 | match | 790 | 1740 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 188.48076824970764 | 77.79460135510689 | 110.68616689460075 | PNAA |

| 110 | match | 825 | 1681 | 839 | 1558 | 814 | 1666 | 123.79418403139947 | 18.601075237738275 | 105.1931087936612 | PNAA |

| 111 | mood | 445 | 1171 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 335.0537270349339 | 322.2483514310042 | 12.80537560392969 | Both |

| 112 | mood | 481 | 1185 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 350.28702516650543 | 320.92366693654736 | 29.363358229958067 | Both |

| 113 | mood | 495 | 1202 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 368.63532115086315 | 311.26355392175293 | 57.37176722911022 | Both |

| 114 | mood | 394 | 1621 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 787.0667061945893 | 144.80676779764127 | 642.259938396948 | Ambiguous |

| 115 | mood | 312 | 1476 | 451 | 836 | 357 | 1481 | 654.9206058752466 | 45.27692569068709 | 609.6436801845595 | Ambiguous |

| 116 | must | 699 | 1509 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 148.32734070291963 | 36.124783736376884 | 112.20255696654274 | PNAA |

| 117 | must | 615 | 1412 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 267.3798795721174 | 110.92339699089638 | 156.456482581221 | PNAA |

| 118 | must | 644 | 1492 | 839 | 1558 | 663 | 1512 | 205.86646157157313 | 27.586228448267445 | 178.2802331233057 | PNAA |

| 119 | spot(s) | 711 | 1288 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 295.29815441346733 | 94.03190947758107 | 201.26624493588628 | PNAA |

| 120 | spot(s) | 678 | 1327 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 323.12381527829234 | 144.84474446799925 | 178.2790708102931 | PNAA |

| 121 | spot(s) | 784 | 1255 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 301.21918929576844 | 50.99019513592785 | 250.2289941598406 | PNAA |

| 122 | spot(s) | 743 | 1198 | 606 | 1012 | 762 | 1209 | 231.00865784641059 | 21.95449840010015 | 209.05415944631045 | PNAA |

| 123 | weed | 366 | 2403 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 178.07021087200408 | 151.16216457830973 | 26.908046293694355 | Both |

| 124 | weed | 363 | 2470 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 111.28791488746656 | 88.83692925805124 | 22.450985629415314 | Both |

| 125 | weed | 356 | 2529 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 54.120236510939236 | 42.5440947723653 | 11.576141738573938 | Both |

| 126 | weed | 347 | 2333 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 249.15858403835898 | 215.10230124292022 | 34.05628279543876 | Both |

| 127 | weird | 371 | 2481 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 100.0 | 84.50443775329198 | 15.495562246708019 | Both |

| 128 | weird | 294 | 2518 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 99.48869282486326 | 36.235341863986875 | 63.25335096087639 | Ambiguous |

| 129 | weird | 360 | 2441 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 140.4314779527724 | 113.46365056704283 | 26.967827385729578 | Both |

| 130 | weird | 288 | 2509 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 109.87720418721983 | 47.01063709417264 | 62.866567093047195 | Ambiguous |

| 131 | weird | 329 | 2548 | 371 | 2581 | 317 | 2546 | 53.41348144429457 | 12.165525060596439 | 71.24795638369813 | Ambiguous |

Notes

| 1 | Several studies have provided their own definitions and typologies depending on the linguistic nature of the receipt language. |

| 2 | The subjects declared having an English language certification (e.g., TOEFL or IELTS); others completed six semesters from an English course offered by the Centro de Educación Continua. The link provides more information about the English course: https://centrodeeducacioncontinua.uabc.mx/ingles/ (accessed on 2 November 2024). |

| 3 | Hagiwara (1997) and Aiello (2010) included northern and southern areas of California as well as both speaker’s sexes. Therefore, they provided sufficient information to ground average formants of this English dialect, suitable at least for the present study, despite the variation in sex among the subjects that crucially influences the average of both formants. |

| 4 | Other studies (Zeldin, 2023) advocated for the use of Euclidean metrics to measure interphonemic distance. The studies emphasized its utility in quantifying phonetic similarity—even with limited data—across languages and applications like hearing assessments. Therefore, this measurement fits ideally for this limited dataset. |

| 5 | This consideration is based on Usage-Based Phonology (Bybee, 1999, pp. 225–227) that suggests that phonetic and phonological patterns arise through the frequency or productive repetitive use of structures. |

| 6 | Contrarily, Escudero (2006) demonstrated that duration could make phonological contrast between English /i/ and /ɪ/ among Spanish native speakers. |

References

- Aiello, A. (2010). A phonetic examination of California [Master’s thesis, University of California]. [Google Scholar]

- Aubanel, V., Davis, C., & Kim, J. (2015, August 10–14). Syllabic structure and informational content in English and Spanish. 18th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS 2015), Glasgow, UK. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-02068860v1 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Baigorri, M., Campanelli, L., & Levy, E. S. (2018). Perception of American-English vowels by early and late Spanish-English bilinguals. Language and Speech, 62(4), 681–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäumler, L. (2024). Loanword phonology of Spanish anglicisms: New insights from corpus data. Languages, 9(9), 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, C. T. (1995). A direct realistic view of cross-language speech perception. In W. Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research (pp. 171–204). York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Best, C. T., & Tyler, M. D. (2007). Nonnative and second-language speech perception: Commonalities and complementarities. In O.-S. Bohn, & M. J. Munro (Eds.), Language experience in second language speech learning: I honor of james emil flege (pp. 13–34). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2023). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (Version 6.1.40) [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/praat/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Bybee, J. L. (1999). Usage-based phonology. In M. Darnell, F. J. Newmeyer, M. Noonman, & E. A. Moravcsik (Eds.), Functionalism and formalism in linguistics (Vol. 1, pp. 211–242). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, A., & Wetzels, L. (2009). Loan phonology: Issues and controversies. In A. Calabrese, & L. Wetzels (Eds.), Loan phonology (pp. 1–10). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duběda, T. (2020). The phonology of anglicisms in French, German and Czech: A contrastive approach. Journal of Language Contact, 13(1), 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Colegio de México. (2010). Diccionario del Español de México. Available online: https://dem.colmex.mx (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Escandón, A. (2019). Linguistic practices and the linguistic landscape along the US-Mexico border: Translanguaging in Tijuana [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southampton]. Available online: http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/id/eprint/438663 (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Escudero, P. (2005). Linguistic perception and second language acquisition: Explaining the attainment of optimal phonological categorization [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Utrecht]. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, P. (2006). The phonological and phonetic development of new vowel contrasts in Spanish learners of English. In B. O. Baptista, & M. A. Watkins (Eds.), English with a Latin beat: Studies in Portuguese/Spanish English interphonology (pp. 41–55). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flege, J. E. (1995). Second-language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In W. Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research (pp. 233–277). York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flege, J. E., Bohn, O.-S., & Jang, S. (1997). Effects of experience on non-native speakers’ production and perception of English vowels. Journal of Phonetics, 25(4), 437–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, H. (2005). Anglicisms and translation. In G. Anderman, & M. Rogers (Eds.), In and out of English: For better, for worse? (pp. 161–184) Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grijalva, C., Piccinini, E., & Arvaniti, A. (2013). The vowels spaces of southern Californian English and Mexican Spanish as produced by monolinguals and bilinguals. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 133(5), 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara, R. (1997). Dialect variation and formant frequency: The American English vowels revisited. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 102(1), 655–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, J. (2010). The phonetic analysis of speech corpora. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Haspelmath, M. (2009). Lexical borrowings: Concepts and issues. In M. Haspelmath, & U. Tadmor (Eds.), Loanwords in the world’s languages: A comparative handbook (pp. 35–54). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeske, A. (2012). The perception of English vowels by native Spanish speakers [Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Pittsburgh]. Available online: http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/13199/ (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Labov, W., Ash, S., & Boberg, C. (2006). The atlas of North American English: Phonetics, phonology and sound change. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Lallier, M., Valdois, S., Lassus-Sangosse, D., Prado, Chloé, & Kandel, S. (2014). Impact of orthographic transparency on typical and atypical reading development: Evidence in French-Spanish bilingual children. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(5), 1177–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanz, L. (2020). Actitudes lingüísticas frente al inglés en Tijuana. Gloss, 9(9), 47–61. Available online: https://glosas.anle.us/site/assets/files/1286/07_lanz_vallejo.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Lanz, L. (2022). Mixed feelings en Tijuana: Bilingüismo, sentimiento y consumo. McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman, M. Y. (2019). Corpus phonetics. Annual Review of Linguistics, 5(1), 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloy, R. (2016/2023). Normalizing and plotting vowels with phonR 1.0.7. Available online: https://drammock.github.io/phonR/ (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Milroy, L., & Gordon, M. (2003). Style-shifting and code-switching. In Sociolinguistics: Method and interpretation (pp. 188–222). Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez-Nogueroles, E. E. (2017). Typographical, orthographic and morphological variation of Anglicisms in a corpus of Spanish newspaper texts. Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses, (75), 175–190. Available online: http://riull.ull.es/xmlui/handle/915/6972 (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Paradis, C., & LaCharité, D. (2008). Apparent phonetic approximation: English loanwords in Old Quebec French. Journal of Linguistics, 44(1), 87–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pols, L. C. W., Tromp, H. R. C., & Plomp, R. (1973). Perceptual and physical space of vowels. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 54(1), 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Real Academia Española. (2001). Nuevo tesoro lexicográfico de la lengua española. Espasa Calpe. Available online: https://www.rae.es/obras-academicas/diccionarios/nuevo-tesoro-lexicografico-0 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Recasens, D. (2015). The effect of stress and speech rate on vowel coarticulation in catalan vowel-consonant-vowel sequences. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(5), 1407–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, C. (2021). Spanish speaker’s English schwar production: Does orthography play a role? Applied Psycholinguistics, 42(6), 1377–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Corvalán, C. (2017). Variación y cambio. In C. Silva-Corvalán, & A. Enrique-Arias (Eds.), Sociolingüística y pragmática del español (2nd ed., pp. 262–297). Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strange, W. (2005). Cross-language comparisons of contextual variation in the production and perception of vowels. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 117, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E. R. (2011). Sociophonetics: An introduction. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, D., & García, L. (2018). Escenarios lingüísticos emergentes en la frontera Tijuana-San Diego. Káñiña, Revista Artes y Letras-Universidad de Costa Rica, 42(2), 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeldin, A. (2023). The Euclidean metrics applied to the interphonemic distance measurements. Philology and Culture, 71(1), 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).