Abstract

This study offers a detailed comparative analysis of the reflexes of Proto-Bantu noun class prefixes within nine Gabonese languages belonging to the B50, B60, and B70 groups of Guthrie’s referential inventory of the Bantu languages. Genealogically speaking, all of them are part of the Kwilu-Ngounie subclade of the Bantu family’s West-Coastal Bantu branch. Starting out from a robust dataset comprising over 4000 lexical items collected through fieldwork and existing descriptions, the Comparative Method is used to distinguish changes in noun class morphology due to regular sound shifts from those emerging from analogical reanalysis and levelling. The comparative study shows a systematic reduction and reorganization of the inherited Proto-Bantu noun class system, notably the loss of classes 12/13 and 19 across all languages, variable retention and loss of classes 7/8 and 11, and complex patterns of reshuffling involving classes 5, 9/10, and 1/2. Key innovations, potentially reinforcing lexicon-based hypotheses of phylogenetic subgrouping within Kwilu-Ngounie, include the development of a class 7 allomorphy conditioned by stem-initial segments in the B50 languages and the emergence of vocalic prefixes restricted to the B60 and B70 languages.

1. Introduction

The evolution of the reconstructed Proto-Bantu noun class system is a topic of longstanding interest to scholars in historical and comparative linguistics (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). Although our diachronic understanding of noun class systems has significantly improved since the start of Bantu historical linguistics in the 19th century CE, the way in which they changed in terms of prefix shapes, noun class pairings, agreement patterns and semantics is still not fully understood in certain subgroups of the Bantu family.

Starting out from this observation, this article examines the reflexes of Proto-Bantu noun class prefixes in present-day Bantu languages belonging to the B50, B60 and B70 groups of the referential classification of the Bantu languages (), as updated by () and revised by (). With other Bantu languages belonging to the B40, B80, H10 and H30 referential groups as well as Kihungan (H42) and Gisamba (L12), these B50-70 languages are part of the “West-Western” branch of the Bantu family (), also known as “West-Coastal Bantu” (; ; ; ; ; ). Our research focusses on B50-70 language varieties spoken in Gabon. Varieties spoken outside Gabon’s borders, i.e., in the Republic of Congo and the Democratic Republic of Congo. This comparative study is limited to Liwanzi (B501), Liduma (B51), Inzebi (B52), Itsengi (B53), Lekaningi (B602), Lembaama (B62), Lendumu (B63), Lintsitseke (B701) and Latege (B71). Within West-Coastal Bantu, all these languages belong to the Kwilu-Ngounie clade in the lexicon-based phylogenetic classification of () (see also ). Except for some rare historical-comparative studies notwithstanding such as (), (), (), and (), the historical development of noun class systems within Kwilu-Ngounie are poorly known.

This contribution, which starts out from my doctoral dissertation (), endeavors to provide diachronic explanations for the evolution of noun class prefixes in the Bantu languages under study. My approach is restricted to changes in the shape of these bound morphemes, through either sound shifts or other drivers of morphological change such as analogy. In as far as sound change is concerned, I rely on the principles of the Comparative Method as exposed in (). Even if I touch upon the more fundamental restructurings which noun class systems underwent as consequence of these changes in noun class morphology, my analysis does not encompass a systematic review of noun class pairings for number marking, agreement patterns through concord prefixes or nominal derivational strategies making use of noun class prefixes, let alone a treatment of noun class semantics.

2. Data and Methods

As is often the case in historical-comparative linguistics, my dataset departs from basic vocabulary, which is deemed to be more resistant to borrowing (), which is extended with more culture-specific and specialized lexicon. My questionnaire includes 465 different concepts, i.e., 140 basic vocabulary items from the ALGAB (Atlas Linguistique du Gabon) () and 325 other concepts from the Comparative Bantu Word List (). My database counts 4185 words in total, which I collected in dictionaries, wordlists included in grammatical descriptions and popular literature and which I extended through dedicated field surveys conducted over three periods (July–September 2017; July–September 2018; July–September 2019) with native speakers of the languages targeted in their home areas.

Table 1 lists the existing sources on which I have relied to obtain additional comparative data from each of the Gabonese West-Coastal Bantu languages in my sample.

Table 1.

Sources used for comparative Gabonese West-Coastal Bantu data.

In my application of the Comparative Method following (), I mainly attempted to establish regular correspondences between the synchronic lexical data in my dataset on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the Bantu grammatical reconstructions in () when it comes to noun class prefixes and the Bantu lexical reconstructions in () when it comes to noun stems.

3. Synchrony and Diachrony of Noun Class Prefixes

Table 2 below presents the noun class prefixes in the Gabonese WCB languages of my sample as they have been analyzed in the existing descriptions which I have consulted (see Table 1) and juxtaposes them to the noun class prefixes reconstructed for Proto-Bantu following ().

Table 2.

Systems of noun classes of Bantu languages (B50, B60 et B70).

Table 2 allows to make some very general comparative observations on the evolution of noun class prefixes in the West-Coastal Bantu languages of Gabon:

- Proto-Bantu noun class prefixes 12, 13, and 19 survived in none of the languages.

- Proto-Bantu noun class prefix 11 was retained in only few languages.

- Proto-Bantu locative noun class prefixes 16, 17, and 18 survived in most languages but not all. I will not further consider them in this study because of complexities in terms of syntax.

- Proto-Bantu noun class prefix 7 and 8 was lost in only one language.

- The reflexes of the noun class prefixes manifest a great degree of formal uniformity across the languages of my sample, especially when it comes to classes 1–10.

- Tonally, the low tones of Proto-Bantu, except for classes 9 and 10, were retained.

- Vocalic prefixes occur only in a minority of the sampled languages, i.e., in B60 and Lateghe (B71), where they coexist with CV-type prefixes that prevail everywhere else. As Proto-Bantu also had CV-type prefixes, vocalic prefixes can be considered a historical innovation that merits further examination.

- The prefixes of noun classes 5, 7, 8 and 11 also manifest some particularities which require a closer historical look.

In the remainder of this section, we will examine more closely the historical developments of those Proto-Bantu noun class prefix which still have reflexes in the West-Coastal Bantu languages of Gabon, except for the locative classes 16–18.

3.1. Classes 1 and 3 *mʊ̀-

Despite having different non-nominal agreement prefixes, and therefore considered distinct, Proto-Bantu noun classes 1 and 3 have the noun prefix *mʊ̀-.

In the B50 languages, this prefix was retained as mù-, which is a phonologically regular reflex of *mʊ̀-, e.g., *mʊ̀-pɪ̀kà ‘slave’ > mù-βègà [mùβèɣà] (class 1) in Liduma (B51) and in *mʊ̀-kɪ́dà ‘tail’ > mù-kélà [mùkélà] (class 3) in Inzebi (B52). These languages lost the contrast between Proto-Bantu *i and *ɪ as well as *u and *ʊ within noun prefixes, which consequently manifest only three vowels: i, a, and u (). In front of vowel-initial stems, the back vowel of mu- undergoes glide formation, e.g., *mʊ̀-jánà ‘child’ > mù-ánà [mwá:nà] (class 1) in Liduma (B51).

In Lekaningi (B602), this contrast was not lost in noun prefixes, but *ɪ and *ʊ underwent lowering to e and o, respectively. Hence, mò- is also a regular reflex of *mʊ̀-, e.g., *mʊ̀-dʊ́mè ‘husband’ > mò-lúmù (class 1), *mʊ̀-tɪ́ ‘tree’ > mò-tí (class 3). In front of vowel-initial stems, mò- undergoes glide formation to mw-, e.g., *mʊ̀-jánà ‘child’ > mw-ánà (class 1).

The B70 and other B60 languages have class 1 and 3 noun prefixes that are vocalic, i.e., ù- in Lintsitseke (B701) and ò- in Lembaama (B62), Lendumu (B63), and Lateghe (B71). The nasal of Proto-Bantu *mʊ̀- only still features in front of vowel-initial stems, e.g., *mʊ̀-jánà ‘child’ > mw-áná (class 1) in Lembaama (B62). Elsewhere, the noun class prefix is either just a mid-back vowel ò-, e.g., *mʊ̀-kʊ́dʊ̀ ‘elder’ > ò-kúlù (class 1), *mʊ̀-nyʊ̀à ‘mouth’ > ò-wà (class 3) in Lateghe (B71), or a high back vowel ù-, e.g., *mʊ̀-kádí ‘woman, wife’ > ù-kálì (class 1), *mʊ̀-tɪ́mà ‘heart’ > ù-tímà (class 3) in Lintsisteke (B701). The emergence of vocalic prefixes of classes 1 and 3 in these languages is not the outcome of regular diachronic sound shift as Proto-Bantu *m is systematically retained. In other words, ù- in Lintsitseke (B701) and ò- in the other three languages are not direct reflexes of Proto-Bantu *mʊ̀-.

In general, and not only for the noun prefixes of classes 1 and 3 (cf. infra), I see two possible ways to account for the replacement of mV-type by V-type noun prefixes. First, taking into account that this is a relatively common evolution also attested elsewhere in West-Coastal Bantu, there is the hypothesis of analogical levelling which () propose for Ngwi (B861), a West-Coastal Bantu spoken south of the Kasai in the Kwilu Province of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The noun prefixes *mʊ̀- of classes 1 and 3 inherited from Proto-Bantu were replaced by their corresponding non-nominal agreement prefixes, i.e., the reflexes of *jʊ- (class 1) and *gʊ- (class 3) (). Due to the convergent diachronic loss of both *j and *g (), these non-nominal agreement prefixes ended up the same, i.e., a V-type prefix with a back vowel. Whether this back vowel is today mid, i.e., o-, or high, i.e., u-, then depends on the historical of the vowel system in each language. Second, the vocalic noun prefixes of classes 1 and 3 could be reflexes of the augment or pre-prefix which precedes the noun prefix in many modern Bantu languages and has also been reconstructed to Proto-Bantu (). This alternative explanation is not fundamentally different from the first one in that the augment is identical in form with the non-nominal agreement prefixes. Hence, the sequence of augment and noun prefix was *jʊ́-mʊ̀- for class 1 and *gʊ́-mʊ̀- for class 3. Because of the parallel deletion of *j and *g, these sequences would have merged into *ʊ́-mʊ̀- for both classes, after which the original noun prefix *mʊ̀- dropped out. The augment is known to be commonly subject to vowel lowering (; ), which would then account for the emergence of ò- in Lembaama (B62), Lendumu (B63), and Lateghe (B71).

3.2. Class 2 *bà- and Class 6 *mà-

I treat the reflexes of Proto-Bantu class 2 *bà- and class 6 *mà- together, not only because they share the same vowel, but also because they underwent the same historical evolutions in the languages under study. They were either conserved as is or they were substituted by a prefix consisting of their low vowel only.

In line with the regular conservation of Proto-Bantu *b and *m, the noun prefixes of classes 2 and 6 were retained in most languages as bà- and mà-, respectively, e.g., *bà-kádí ‘woman, wife’ > bà-káásà, *bà-jánà ‘children’ > bà-ánà [bá:nà] (class 2) in Itsengi (B53), *mà-cùbà ‘urine > mà-súbà, *mà-gàdí ‘oil’ > mà-árì [má:rì] (class 6) in Lekaniŋgi (B602). Note that Lintsitseke (B701), which replaced the mV-type noun prefixes of classes 1 and 3 by a V-type prefix (see Section 3.1), retained Proto-Bantu’s CV-type noun prefixes for classes 2 and 6.

Lembaama (B62), Lendumu (B63), and Lateghe (B71), the three other languages in my sample which vocalic noun prefixes for classes 1 and 3 (see Section 3.1), do also have à- for classes 2 and 6, e.g., *kʊ́dà ‘red color, substance’ > à-kúlá ‘Pygmies’ (class 2) in Lateghe (B71), *mà-gìdá ‘blood’ > à-kílà (class 6) in Lembaama (B62). As with the class 1 and 3 noun prefixes (see Section 3.1), CV-type prefixes were only conserved in front of vowel-initial stems, e.g., *bà-jánà ‘children’ > bà-ánà [bá:nà] (class 2) in Lateghe (B71), *mà-jícò ‘eyes’ > mà-ísí [mí:sí] (class 6) in Lembaama (B62). Once again, the emergence of à- prefixes in classes 2 and 6 cannot result from regular sound change. Neither Proto-Bantu *b nor *m underwent reduction to zero in the languages in question, as the conservation of ba- and ma- before vowel-initial stems indicates. Just like the vocalic prefixes of classes 1 and 3 (see Section 3.1), class 6 à- probably originates in Proto-Bantu *gá-, which is both the non-nominal agreement prefix and the augment (). Proto-Bantu *g does have zero reflexes in those languages (). This does not hold for class 2, as the non-nominal agreement prefix and augment is segmentally identical to the noun prefix, i.e., *bá-. As *b loss did not take place here either, à- may have its source in the augment, which is commonly reduced to just a vowel across Bantu, irrespectively of the regular diachronic evolution of its consonant (; ).

3.3. Class 4 *mɪ̀-

The reflexes of Proto-Bantu class 4 *mɪ̀- manifest the same patterns as those of Proto-Bantu class 2 *bà- and class 6 *mà-, i.e., conservation in all languages except in Lembaama (B62), Lendumu (B63), and Lateghe (B71), which have innovated towards a vocalic prefix.

Complying with the systematic retention of Proto-Bantu *m, the noun prefix of class 4 was conserved in most languages as mì-, e.g., *mɪ̀-cìngà ‘string; body hair’ > mì-síngà ‘veins’ in Liwanzi (B501). Lekaniŋgi (B602) is the only to have preserved *mɪ̀- as mè-, e.g., *mɪ̀-kígè ‘eyebrows’ > mè-kíngì. This ties in with its conservation of Proto-Bantu class 1 and 3 *mʊ̀- as mò- (see Section 3.1). In noun prefixes, Lekaningi (B602) maintained the contrast between *i vs. *ɪ and *u vs. *ʊ, but *ɪ and *ʊ were lowered to e and o, respectively.

In line with the evolution of their noun prefixes of classes 1 and 3 (see Section 3.1) as well as classes 2 and 6 (see Section 3.2), Lembaama (B62), Lendumu (B63), and Lateghe (B71) have a vocalic prefix for class 4, i.e., è-, e.g., *mɪ̀-tɪ́mà ‘hearts’ > è-tímà in Lendumu (B63). It has the same degree of aperture as their class 1 and 3 prefix ò-. It likely also originates in the shape of the Proto-Bantu non-nominal agreement prefix and augment of class 4, i.e., *gɪ́-. Proto-Bantu *g is commonly reduced to zero in those languages ().

3.4. Class 5 *ì-

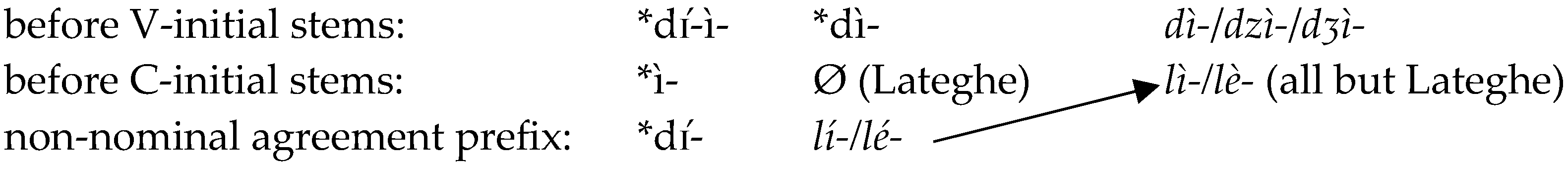

Proto-Bantu class 5 is the only one for which a vocalic prefix has been reconstructed, i.e., *ì-. Its non-nominal agreement prefix and augment does have a reconstructed initial consonant, i.e., *dɪ́-. The Proto-Bantu augment-noun prefix sequence *dɪ́-ì- led to a variety of different class 5 noun prefixes in present-day Bantu languages (). A common evolution is towards a complementary distribution between two allomorphs, i.e., one with a V-shape such as i- before consonant-initial stems vs. one with a CV-shape such as di-, ri-, li-, etc. before vowel-initial stems. In this division of labor, the pre-consonantal vocalic prefix often evolves into a zero prefix (). The situation is the Gabonese WCB languages is clearly different as Table 2 shows. They do have two allomorphs, but in all languages except Lateghe (B71), both have a different CV-shape, i.e., one that starts with the obstruent /d/, /dz/ or /dʒ/ before vowel-initial stems and one that begins with the liquid /l/ before consonant-initial stems.

Although often neglected in the available grammatical descriptions which I have consulted, all languages in my sample have a class 5 CV-prefix starting with an obstruent in front of vowel-initial stems. In that context, Liduma (B51) and Inzebi (B52) have an allomorph beginning with the alveolar stop /d/, i.e., dì-, e.g., *dɪ́-ì-jínò ‘tooth’ > dì-ínù [dí:nù] in Liduma (B51). In Liwanzi (B501), Lintsitseke (B701) and Latege (B71), the corresponding allomorph starts with the alveolar affricate /dz/, i.e., dzi-, e.g., *dɪ́-ì-jícò ‘eye’ > dzì-ísì [dzí:sì] in Lintsitseke (B701). Itsengi (B53), Lekaningi (B602), Lembaama (B62) and Lendumu (B63) share an allomorph with the initial postalveolar affricate /dʒ/, i.e., dʒi-, e.g., *dɪ́-ì-jínò ‘tooth’ > dʒì-ínì [dʒí:nì] in Lekaningi (B602). I consider this allomorph restricted to vowel-initial stems as a reflex of the amalgamation of the augment-noun prefix sequence *dɪ́-ì- into the noun prefix *dì-, i.e., *dɪ́-ì- > *dì-. This fusion happened in favor of the close front vowel *i of the original Proto-Bantu noun prefix, which was conserved to the detriment of the near-close front vowel *ɪ of the augment. The variation between /d/, /dz/ and /dʒ/, which the allomorph manifests initially, reflects divergent but regular reflexes of Proto-Bantu *d in front of the Proto-Bantu high front vowel *i, e.g., Itsengi (B53) *n-dímʊ̀ ‘spirit’ > n-dʒímà [ndʒímà] vs. *kʊ̀-dɪ̀d-à ‘to cry’ > ù-lìl-à. As the same allomorph is attested in all languages in my sample, the innovation *dɪ́-ì- > *dì- likely happened in a common ancestor language.

Before consonant-initial stems, all languages except Lateghe (B71) have an allomorph starting with the liquid /l/, which is often erroneously presented as the only class 5 prefix in certain grammatical descriptions. In Lateghe (B71), the allomorph has a zero representation, but compensatory diphthongization may occur root-internally, e.g., *ì-béèdè ‘breast’ > Ø-béélè [byélè]. In all B50 languages and Lintsitseke (B701), the allomorph before stems beginning with a consonant is lì-, e.g., *ì-pácà ‘twin’ > lì-βásà in Inzebi (B52). The B60 languages share an allomorph whose front vowel is lowered, i.e., lè-, e.g., * ì-bádà ‘marriage’ > lè-bálà in Lembaama (B62). This CV-type with initial liquid cannot be a direct reflex of the Proto-Bantu class 5 noun prefix *i-, which is often retained preceding consonant-initial stems in modern Bantu languages. Its initial /l/ is a regular reflex of Proto-Bantu *d in front of Proto-Bantu vowels other than close *i and *u. Hence, its shape seems rather a reflex of the Proto-Bantu class 5 non-nominal agreement prefix and augment *dɪ́-. The close-mid front vowel /e/ in the lè- prefix of the B60 languages is a diagnostic trace of the Proto-Bantu near-close front vowel *ɪ which is regularly lowered to /e/ in prefixes (see also Section 3.1 and Section 3.3).

To account for lì-/lè- in front of consonant-initial stems, I see two possible scenarios: either it is a divergent evolution of the augment-noun prefix sequence *dɪ́-ì- or it is an analogically motivated innovation of the noun prefix on the model of the non-nominal agreement prefix. The second option seems the most likely for at least two reasons. First, the languages concerned already have a different reflex of *dɪ́-ì- in front of vowel-initial stems, which can only be accounted for as originating in this specific sequence. It is difficult to conceive how one and the same augment-noun prefix sequence could give rise to divergent outcomes in front of vowel-initial and consonant-initial stems. Second, at least one of the languages in the sample, i.e., Lateghe (B71), has the class 5 zero prefix, i.e., the allomorph which Bantu languages commonly have before consonant-initial stems (cf. supra). Hence, it is plausible to assume that all languages concerned went through a phase whereby the Proto-Bantu class 5 noun prefix *ì- was reduced to zero before stems beginning with a consonant. Subsequently, all languages except Lateghe (B71) innovated that specific allomorph by creating a new noun prefix based on the segmental form of the regular reflex of the non-nominal agreement prefix of class 5 *dɪ́-.

In the sum, the complementary distributed allomorphs of the class 5 noun prefix would have evolved as summarized as follows, whereby > represents regular sound changes and ↗ an analogically motivated paradigm transposition.

3.5. Class 7 *kɪ̀-

The Proto-Bantu class 7 *kɪ̀- prefix survived in different forms in all languages of my sample, except for Lekaningi (B602), where it disappeared together with its usual plural equivalent of class 8, i.e., *bì- (see Section 3.6).

In the other B60 languages and in the B70 languages, *kɪ̀- exclusively with a CV-shape and with retention of its initial velar stop. In Lembaama (B62) and Lintsitseke (B701), its form resembles most the reconstructed Proto-Bantu prefix, i.e., kì-, e.g., *kɪ̀-bìmbà ‘corpse’ > kì-bímà in Lintsitseke (B701). Its close front vowel /i/ is in line with the languages’ regular merger of Proto-Bantu close *i and near-close *ɪ in favor of the former. In Lendumu (B63), not only the prefix vowel became close, but its initial consonant also underwent voicing to gì-, which is also a regular historical development in the language (), e.g., *kɪ̀-bídí ‘soot’ > gì-víri [ɣìvírì] ‘coal’. In Lateghe (B71), the class 7 noun prefix is ká-, e.g., *kɪ̀-pɪ̀cɪ́ ‘bone’ > ká-yèrí. Although *ɪ > a is not a regular sound shift in the language, it is also observed within prefixes in other West-Coastal Bantu languages, such as Mbuun (B87) (), and in other Bantu languages, such as the Gabonese North-Western Bantu language Fang (A75), where /a/ in prefixes probably results from the reinforcement of /ə/, itself a weaking of *ɪ ().

The B50 languages developed a class 7 noun prefix allomorphy, which is not so common for this noun class in Bantu, and which certainly not goes as deep back in time as the one observed more generally for class 5 (see Section 3.4). These languages manifest a complementary distribution between a V-shaped allomorph in front of consonant-initial stems and a CV-shaped allomorph before vowel-initial stems. When the noun stem starts with a consonant, they all have ì-, e.g., *kɪ̀-gʊ̀dʊ̀ ‘hill’ > ì-kúrì ‘hill, mountain’. The close front vowel of the prefix is expected following the regular merger of Proto-Bantu close *i and near-close *ɪ to the detriment of the latter. The complete loss of Proto-Bantu velar stops, i.e., *k/*g > Ø, is not so common in the B50 languages, but also not completely unattested (). Preceding vowel-initial stems, the B50 languages have a CV-shaped allomorph whose initial consonant is a fricative, either postalveolar /ʃ/ in Inzebi (B52) and Itsengi (B53), e.g., *kɪ̀-gèdà ‘iron; iron thing’ > ʃì-ílà [ʃí:là] ‘thing’ in Inzebi (B52), or /s/ in Liwanzi (B501) and Liduma (B51), e.g., *kɪ̀-tòdó ‘sleep’ > sì-ᴐ́lᴐ́ [syᴐ́:lᴐ̀] in Liduma (B51). These prefix shapes are the outcome of sound shifts to which Proto-Bantu *kɪ̀- is often subject across Bantu (), i.e., velar palatalization (or rather postalveolarization) of *k to ʃ before the reflex of *ɪ, and the subsequent depalatalization (or rather depostalveolarization) of ʃ to s: *kɪ̀- > ʃì- > sì-. These diachronic processes probably took place after an initial split between i- before consonant-initial stems and ki- before vowel-initial stems, as summarized below:

| before V-initial stems: | *kɪ̀- | kì- | ʃì- | sì- |

| before C-initial stems: | *kɪ̀- | ì- |

In principle, the vocalic allomorph ì- in front of consonant-initial stems could also have emerged after first having gone through a phase of postalveolarization of *k in Inzebi (B52) and Itsengi (B53) and subsequent depostalveolarization in Liwanzi (B501) and Liduma (B51) before losing its initial fricative, i.e., kì- > ʃì- > sì- > ì-. However, the complete loss of ʃ in Inzebi (B52) and Itsengi (B53) and of s in Liwanzi (B501) and Liduma (B51) is not attested. It is therefore more plausible to assume that the fricatives ʃ and s only emerged after an initial contextually conditioned split between ki- (before V) and i- (before C). In any event, the development of this class 7 noun prefix allomorphy is an innovation only shared among the B50 languages suggesting that they are more closely related among each other than with the other Gabonese WCB languages considered here. Within B50, Liwanzi (B501) and Liduma (B51) could be more closely related as they are the only two to share the depostalveolarization of ʃì- to sì-.

3.6. Class 8 *bì-

The Proto-Bantu class 8 prefix *bì- was retained quite uniformly as bì- in all languages of my sample, except for Lekaningi (B602), where it disappeared together with its usual singular equivalent of class 7, i.e., *kɪ̀- (see Section 3.5), and in Lateghe (B71), where this noun prefix now takes the form è-.

As for bì-, it is direct unchanged reflex of Proto-Bantu *bì-, e.g., *bì-tákò ‘buttocks’ > bì-tákì in Lintsitseke (B701), *bì-bʊ̀ngʊ́ ‘hyenas’ > bì-búngù ‘lions’ in Inzebi (B52). In front of vowel-initial stems, its vowel undergoes glide formation with by- as surface realization, e.g., *bì-gèdà ‘iron; iron things’ > bì-ílà [byí:là] ‘things’ in Lembaama (B62).

As for e- in Lateghe (B71), e.g., è-tólì ‘claws, nails’ and é-kò ‘clothes’, this vocalic prefix is in line with the language’s development of vowel prefixes in other noun classes, such as 1 and 3 (see Section 3.1), 2 and 6 (see Section 3.2), and 4 (see Section 3.3). As in the other noun classes, è- cannot be a phonologically regular reflex of *bì-. Neither *b is systematically reduced to zero nor *i regularly shifts to e. It can also not be the reflex of the non-nominal agreement prefix *bí-, as it is segmentally identical to the noun prefix. As I have argued for the à- prefix of classes 2 and 6 in Lateghe (B71) (see Section 3.2), è- may have its source in the augment, which is commonly reduced to just a vowel across Bantu, irrespectively of the regular diachronic evolution of its consonant. What is more, the augment vowel is often subject to lowering independently of how vowels evolve otherwise in the language (; ). Another hypothesis that needs further examination is whether class 8 in Lateghe (B71) did not undergo a merger with a different class whose prefix could have regularly evolved into è- (see also ).

3.7. Classes 9-10 *n-

Based on Table 2, one could suppose that all Gabonese West-Coastal Bantu languages in my sample just retained the homorganic nasal *n- which was reconstructed for both class 9 and 10 in Proto-Bantu. This is only partly true. All languages do indeed have singular and plural nouns whose initial nasal adopts the place of articulation of the stem’s first consonant. For example, in Itsengi (B53), we observe *n-bʊ́tʊ́ ‘seed(s)’ > n-bútù [mbútù], whose initial nasal is a bilabial in line with the bilabial articulation of the following consonant. Likewise, in Lekaningi (B602), there is *n-jɪ̀dà ‘path’ > n-dʒílà [ndʒílà], whose initial nasal adopts the position of articulation of the postalveolar affricate which it precedes. In Liduma (B51), the initial nasal is velar when the following consonant also is, e.g., *n-gàndʊ́ ‘crocodile’ > n-gàndú [ŋgà:ndú] whose first nasal is velar. In front of vowels, the nasal is commonly realized palatal, e.g., *n-jádà ‘fingernail; toenail; claw’ > n-ádà [ɲádà] in Itsengi (B53), *n-jʊ́tʊ̀ ‘body’ > n-ùtù [ɲùtù] in Lintsitseke (B701). When the stem starts with a nasal, the erstwhile nasal prefix usually drops as the languages under study no not license geminate nasals, e.g., *n-nyàmà ‘animal’ > n-ɲámà [ɲámà] in Lekaningi (B602).

Despite the general conservation of the class 9-10 homorganic nasal prefix *n-, the languages do vary in how it is realized in front of voiceless consonants, a variation that is common in Bantu more widely (). Lembaama (B62) and the B70 languages retain a homorganic nasal in that context, e.g., *n-cádá ‘feather’ > n-tʃálá [ntʃálá], n-kú [ŋkú] ‘hair’ in Lembaama (B62), *n-pígò ‘kidney’ > n-píkì [mpíkì] ‘loins, hips’ in Lintsitseke (B701), *n-pʊ́tá ‘wound’ > n-púrà [mpúrà], *n-tʊ́dò ‘chest’ > n-túlù [ntúlù] in Lateghe (B71). All other languages reduce the initial nasal to zero in front of an unvoiced consonant, e.g., *n-tàbà ‘goat’ > n-tàbà [tàβà] in Liwanzi (B501), *n-kʊ́nì ‘firewoods’ > n-kúɲì [kúɲì] in Liduma (B51). Although the B50 languages and the B60 languages except Lembaama (B62) share this innovation *n > Ø/__C[-voice], it is hard to tell whether it is diagnostic of a closer genealogical relationship between them. As the loss of homorganic nasals in this context is common across Bantu, it could also be a parallel innovation.

3.8. Classe 11 *dʊ̀-

The reflex of Proto-Bantu class 11 *dʊ̀- perished in most languages in our sample. It only persisted in Inzebi (B52), Itsengi (B53), and Lateghe (B71). In each of these languages it evolved into a different shape, though always starting with a liquid, which is the reflex of *d in front of non-close vowels. In Itsengi (B53), the prefix maintained its back vowel but heightened it following the merger of Proto-Bantu *u and *ʊ to the detriment of the latter, i.e., lù-, e.g., *dʊ̀-bàgàdà ‘male’ > lù-bàgə̀lə̀ [lùbàɣə̀lə̀] ‘man’. In Inzebi (B52), its vowel was centralized and lowered to give rise to a schwa, i.e., lə̀-, e.g., *dʊ̀-kʊ́nì ‘firewood’ > lə̀-kúɲì. The development of a schwa is not observed for any of the other Inzebi (B52) noun prefixes, also not those originally having *ʊ (see Section 3.1, Section 3.9 and Section 3.10). However, the centralization and lowering of back vowels is attested word-finally in Inzebi (B52), but rather to a than to schwa, e.g., *mʊ̀-démbó ‘finger’ > mù-lémbà, *mʊ̀-dàmbʊ́ ‘tribe’ > mù-lámbà, *bɪ́cù ‘unripe; uncooked’ > m-bísà. () calls this frequent word-final vowel shift the “Nzebi rule”. In Lateghe (B71), we see this further lowering to a also in the prefix itself, i.e., là-, e.g., *dʊ̀-bádɪ̀ ‘side’ > là-bárì ‘arrow’, an evolution which the class 7 prefix *kɪ̀- also underwent in the language. Although the emergence of different class 11 noun prefix shapes could be seriated as *dʊ̀- > lù- > lə̀- > là-, this phenomenon of back vowel lowering is maybe too common in the broader area to consider Inzebi (B52) and Lateghe (B71) more closely related to each other than to Itsengi (B53), where the prefix retained its back vowel. It could easily have happened independently in Inzebi (B52) and Lateghe (B71).

3.9. Classe 11 *bʊ̀-

The Proto-Bantu class 14 prefix *bʊ̀- evolved in two different ways in the languages of my sample. In the B50 languages and Lintsitseke (B701), the ancestral CV-shape is maintained. In the B60 languages and Lateghe (B71), the present-day prefix is vocalic. Among those languages, Lekaningi (B602) is the only one to have retained a CV-shaped prefix in classes 1 and 3 (see Section 3.1), 2 and 6 (see Section 3.2), and 4 (see Section 3.3).

The CV-type reflex of Proto-Bantu *bʊ̀- is bù- in all languages concerned, e.g., *bʊ̀-nénè ‘bigness’ > bù-nénì, *bʊ̀-dògì ‘witchcraft’ > bù-lògì in Liduma (B51). This shape is in line with the regular conservation of Proto-Bantu *b as b and the regular merger of Proto-Bantu *u and *ʊ into u.

The form of the V-type class 14 prefix is ò- in all languages concerned, e.g., *bʊ̀-dàdì ‘madness’ > ò-lárì, *bʊ̀-jédì ‘wisdom’ > ò-yédì in Lembaama (B62). The development of this prefix consisting of a mid-back vowel does not tie in with regular evolutions in diachronic phonology as *b is normally also conserved in these languages and o is not a regular reflex of Proto-Bantu *ʊ. As I have discussed for the à- prefix of classes 2 and 6 (see Section 3.2) and the è- prefix of class 8 (see Section 3.6), ò- could originate in the augment, which is commonly reduced to just a vowel across Bantu, independently from the regular historical development of its consonant, and whose vowel often subject undergoes lowering (; ).

3.10. Classe 15 *kʊ̀-

As in many Bantu languages (), infinitives belong to noun class 15 in the Gabonese West-Coastal Bantu language of my sample. When it comes to infinitives, the Proto-Bantu prefix *kʊ̀- of class 15 survived as a CV-shaped prefix in Liwanzi (B501), Liduma (B51), Lendumu (B63), Lintsitseke (B701), and Lateghe (B71), everywhere as kù-, which is expected following the merger of Proto-Bantu *u and *ʊ in favor of the former.

Inzebi (B52), Itsengi (B53), Lekaningi (B602) and Lebaama (B62) have a V-type infinitival prefix. In the two B50 languages, it consists of the close back vowel ù-, e.g., *kʊ̀-kùt-à ‘to tell lies’ > ù-kùt-ù in Nzebi (B52). In the two B60 languages, it has the mid-back vowel ò-, e.g., *kʊ̀-dámb-à ‘cook, boil’ > ò-láám-á in Lekaningi (B602). As *k is commonly reduced to zero in these languages, this vocalic prefix could be a direct reflex of *kʊ̀-. The ù- shape in the B50 languages ties in with the regular merger of Proto-Bantu *u and *ʊ to the detriment of the latter. The lowering of the vowel to ò- in the B60 languages is also observed for the class 1 and 3 prefixes (see Section 3.1) and class 14 prefix (see Section 3.9).

Despite the development of vocalic class 15 prefixes, its ancestral CV-shape still survives in some rare nouns for body parts whose stem start a vowel, e.g., *kʊ̀-bókò ‘arm’ > kù-ᴐ́gᴐ̀ [kwᴐ́:ɣᴐ̀], *kʊ̀-gʊ̀dʊ̀ ‘leg’ > kù-úlù [kú:lù] in Liwanzi (B501), but these nowadays trigger agreement in class 3.

4. Conclusions

The comparative data presented in this article on how Proto-Bantu noun prefixes evolved in the Gabonese West-Coastal Bantu languages show both significant cross-linguistic correspondences and differences.

When it comes to the number of different noun classes, Table 2 shows that the inherited Proto-Bantu shrunk in all languages of my sample, but to variable extents. While the prefixes of noun classes 12/13 and 19 disappeared in all languages, those of the class pair 7/8 only disappeared in Lekaningi (B602). Then again, the noun class 11 prefix only survived in three languages. These class deletions have contributed to a reduced prefix system. It is therefore legitimate to ask what has become of the nouns that were historically part of these now-defunct classes. We could logically assume that they were absorbed by other classes to the point of even leaving no trace at all as is the case for classes 12/13 and 19 or just some residual forms.

The example of the Lembaama (B62) is highly telling regarding such relic noun classes and indicative of how class pair 7/8 disappeared from its close relative Lekaningi (B602). Unlike Lekaningi (B602), Lembaama (B62) still has two nouns manifesting a class 7/8 kì-/bì- singular/plural alternation, i.e., kììlà/bììlà ‘thing(s)’ and kʲílà/bʲílà ‘food(s)’. However, they already manifest agreement in classes 3/4, i.e., kì-ìlà ò-níní ‘a wide thing’ (instead of **kì-ìlà kì-níní), bì-ìlà è-kuna ‘lots of food’ (instead of ** bì-ìlà bì-kuna). This shows that classes 7/8 have already merged with classes 3/4 in terms of agreement, and apart from these two residual nouns, also in terms of noun prefixes, a process which is fully completed in Lekaningi (B602).

Similarly, the disappearance of class 11 in most languages is probably linked with its (partial) absorption into class 5 because of the phonemic merger between their noun prefixes. Highly diagnostic in this respect are class 5 nouns whose stems originally belonged to the class pair 11/10 and whose plural class 10 homorganic nasal prefix is sometimes still visible as a trace stem-initially, e.g., *dʊ̀-pémbé/*n-pémbé ‘white clay; white colour’ > lì-pémbè ‘kaolin’ (class 5) in Itsengi (B53), *dʊ̀-dèdì/*n-dèdì ‘beard (hair)’ > lè-ndérì ‘beard’ (class 5) in Lekaningi (B602), This innovation has also been observed in West-Coastal Bantu languages of the Kwilu-Ngounie subgroup outside of Gabon (; ; ), and is therefore potentially highly relevant for West-Coastal Bantu genealogical subclassification. It should also be further examined to what extent classes 5 and 9 were integrated into each other and reshuffled, a noun class system restructuring also observed in the B40 languages of the Kikongo Language Cluster (; ).

As discussed in () and (), the animacy-based reclassification of historical class 9/10 nouns referring to animals into the class pair 1/2, possibly under the influence of stories where animals are often personified (), is also another shared innovation potentially indicative of genealogical relationships within West-Coastal Bantu (see also ). The semantic split of the inherited Proto-Bantu class pair 9/10 whereby inanimate and animate nouns end up in different present-day noun classes is a very common phenomenon among West-Coastal Bantu languages of Guthrie’s B50-70 groups. It is indeed also attested in several languages of my sample, especially for the plural. The class 2 prefix of plural animal names is often followed by a homorganic nasal, which is the ancient plural prefix of classes 9/10 integrated into the noun stem, e.g., *n-gìngì ‘flies’ > bà-ŋgíngì in Liduma (B51), *n-gùbʊ́ ‘hippopotami’ > à-ŋgùbú in Lembaama (B62). Inanimate nouns that used to belong to the class pair 9/10 often make their plural in class 6, whose noun prefix is also often followed by the erstwhile homorganic nasal of classes 9/10 now petrified as part of the stem, e.g., *n-dɪ̀dò ‘boundaries’ > mà-ndílí in Lintsitseke (B701), *n-gìdà ‘taboos’ > à-ndʒírì in Lendumu (B63).

Finally, I wish to highlight two other shared innovations in the noun class prefixes of the Gabonese West-Coastal Bantu languages which possibly reinforce recent insights into the genealogical structure of West-Coastal Bantu’s Kwilu-Ngounie subbranch (, ). The development of a class 7 allomorphy opposing vowel-initial and consonant-initial stems is possibly an innovation uniquely shared between the B50 languages, which thus corroborating their closer relatedness within Kwilu-Ngounie. Then again, the development of vocalic prefixes not explainable through regular sound change is only attested in B60 and B70 languages in my sample, possibly corroborating that they are more closely related amongst each other within Kwilu-Ngounie than with the B50 languages (). The innovation of the prefixes involved in the class 5 allomorphy inherited from Proto-Bantu might be one shared by all Kwilu-Ngounie languages, which would reinforce their genealogical unity as a West-Coastal Bantu subbranch. More research is needed to work this out.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

https://hal.science/tel-03660292v1, accessed on 26 May 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Assoumou Ella, T. (2004). Esquisse phonologique et morphologique du téké B71, langue bantoue du Gabon. Université Omar Bongo, Mémoire de Maîtrise. [Google Scholar]

- Bastin, Y., Coupez, A., & Mann, M. (1999). Continuity and divergence in the bantu languages: Perspectives from a lexicostatistic study. Royal Museum for Central Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Bastin, Y., Coupez, A., Mumba, E., & Schadeberg, T. C. (Eds.). (2002). Bantu lexical reconstructions 3. Royal Museum for Central Africa. Available online: https://www.africamuseum.be/nl/research/discover/human_sciences/culture_society/blr (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Blanchon, J. A. (1987a). Les classes nominales 9, 10 et 11 dans le groupe B40. Pholia, 2, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchon, J. A. (1987b). Les voyelles finales des nominaux du yinzèbi. Pholia, 2, 47–73. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchon, J. A., & Alihanga, M. (1992). Notes sur la morphologie du lempiini de Eyuga. Pholia, 7, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bleek, W. H. I. (1869). A Comparative grammar of South African languages. Part II. The concord. Trübner & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Bollaert, F. (2019). A historical-comparative study of the noun class systems in the kasai-ngounie (Extended) languages (Bantu B50-70, B81-84) [Master’s thesis, Ghent University]. [Google Scholar]

- Bollaert, F., Pacchiarotti, S., & Bostoen, K. (2021). The noun class system of bwala, an undocumented teke language from the DRC (Bantu, B70z). Nordic Journal of African Studies, 30, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bostoen, K., & de Schryver, G.-M. (2018). Seventeenth-century kikongo is not the ancestor of present-day kikongo. In K. Bostoen, & I. Brinkman (Eds.), The kongo kingdom: The origins, dynamics and cosmopolitan culture of an African polity (pp. 60–102). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Blois, K. F. (1970). The augment in the Bantu languages. Africana Linguistica, 4, 85–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Schryver, G.-M., Grollemund, R., Branford, S., & Bostoen, K. (2015). Introducing a state-of-the-art phylogenetic classification of the Kikongo language cluster. Africana Linguistica, 21, 87–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Garbo, F., & Verkerk, A. (2022). A typology of northwestern Bantu gender systems. Linguistics, 60(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodo Bounguendza, E. (1986). Perspectives linguistiques pour l’enseignement du liwandji (cours préparatoires première et deuxième années). Université Omar Bongo, Mémoire de Maîtrise. [Google Scholar]

- Forges, G. (1983). La classe de l’infinitif en bantou. Africana Linguistica, 9, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grollemund, R., Branford, S., Bostoen, K., Meade, A., Venditti, C., & Pagel, M. (2015). Bantu expansion shows that habitat alters the route and pace of human dispersals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112, 13296–13301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, M. (1971). Comparative bantu: An introduction to the comparative linguistics and prehistory of the bantu languages. In Volume 2: Bantu prehistory, inventory and indexes. Gregg International. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, L. M., Lionnet, F., & Ngolele, C. (2019). Number and animacy in the Teke noun class system. In S. Lotven, S. Bongiovanni, P. Weirich, R. Botne, & S. G. Obeng (Eds.), African linguistics across the disciplines: Selected papers from the 48th Annual conference on African linguistics (pp. 89–102). Language Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Idiata, D. F. (2000). Classes nominales et catégorisation en inzèbi (B50, Gabon). In D. F. Idiata, M. Leitch, P. Ondo-Mebiame, & J.-P. Rekanga (Eds.), Les classes nominales et leur semantisme dans les langues bantu du Nord-ouest (pp. 23–32). Lincom Europa. [Google Scholar]

- Ikapi Nziengui, D.-D. (2014). De la phonétique à la phonologie du lintsitsèkè de Lendoundoungou (B701a). Université Omar Bongo, Mémoire de Maîtrise. [Google Scholar]

- Kadima, M. (1969). Le système des classes en bantou. Vander. [Google Scholar]

- Kamba Muzenga, J.-G. (1988). Comportement du préfixe nominal de classe 5 en bantou. Annales Aequatoria, 9, 89–131. [Google Scholar]

- Katamba, F. (2003). Bantu nominal morphology. In D. Nurse, & G. Philippson (Eds.), The bantu languages (pp. 103–120). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kerremans, R. (1980). Nasale suivie de consonne sourde en proto-bantu. Africana Linguistica, 8, 159–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koile, E., Greenhill, S. J., Blasi, D. E., Bouckaert, R., & Gray, R. D. (2022). Phylogeographic analysis of the Bantu language expansion supports a rainforest route. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119, e2112853119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maho, J. F. (1999). A comparative study of Bantu noun classes. Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. [Google Scholar]

- Maho, J. F. (2009). NUGL online: The online version of the new updated guthrie list, a referential classification of the bantu languages. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242323260_NUGL_Online_The_online_version_of_the_New_Updated_Guthrie_List_a_referential_classification_of_the_Bantu_languages (accessed on 4 June 2009).

- Marchal-Nasse, C. (1989). De la phonologie à la morphologie du nzebi, langue bantoue (B52) du Gabon [Ph.D. thesis, Université libre de Bruxelles]. [Google Scholar]

- Mba Ondo, J.-P. (2008). Essai de morphologie nominale et pronominale du lekaniŋi, langue bantoue du groupe B60. Université Omar Bongo, Mémoire de Maîtrise. [Google Scholar]

- Medjo Mvé, P. (1989). Exploration morpho-syntaxique du dialecte le nyani ou contribution à l’étude du verbe ndumu. Université Omar Bongo, Mémoire de Maîtrise. [Google Scholar]

- Meeussen, A. E. (1967). Bantu grammatical reconstructions. Africana Linguistica, 3, 79–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhof, C. (1906). Grundzüge einer vergleichenden Grammatik der bantusprachen. Reimer. [Google Scholar]

- Mickala-Manfoumbi, R. (1988). Eléments de description du duma, langue bantu du Gabon (B51). Université libre de Bruxelles, Mémoire de Licence Spéciale. [Google Scholar]

- Mouélé, M. (1988). Description d’un parler ndumu le nyani (phonétique, phonologie, morphologie nominale et pronominale). Université Omar Bongo, Mémoire de Maîtrise. [Google Scholar]

- Mouélé, M. (1997). Étude synchronique et diachronique des parlers dúmá (groupe bantu B.50) [Ph.D. thesis, Université Lumière Lyon 2]. [Google Scholar]

- Mundeke, L. (1979). Esquisse grammaticale de la langue mbúún (parler de Éliob). Université Nationale du Zaïre, Mémoire de Licence. [Google Scholar]

- Munguengui Nzamba, W. (2009). Morphologie verbale du lekaningi, langue bantoue du Gabon (B66). Université Omar Bongo, Mémoire de Maîtrise. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, P. (2000). Comparative linguistics. In B. Heine, & D. Nurse (Eds.), African languages. An introduction (pp. 59–271). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Niama Niama, J. (2016). La diachronie du yilumbu (B 44), parlé à Mayumba: Eléments de phonologie et de morphologie nominale. Université Omar Bongo, Mémoire de Master Recherche. [Google Scholar]

- Niama Niama, J. (2021). Approche historico-comparative des langues bantu du Gabon: Vers de nouveaux embranchements phonologiques partagés entre les groupes B50-60-70 [Ph.D. thesis, Université Omar Bongo]. [Google Scholar]

- Ntolo, B. (2001). Esquisse phonologique du tsèngi, parlé à Lemanassa (langue bantou, B53). Université Omar Bongo, Mémoire de Maîtrise. [Google Scholar]

- Nzang-Bie, Y. (2014). Revisitation des classes nominales non locatives dans les langues du groupe A70. Revue Africaine et Malgache de Recherche Scientifique (RAMReS) ‘Littérature, Langues et Linguistique’, 2, 137–169. [Google Scholar]

- Okoudowa, B. (2005). Descrição preliminar de aspectos da fonologia e da morfologia do lembaama [Master’s thesis, Universidade de São Paulo]. [Google Scholar]

- Pacchiarotti, S., & Bostoen, K. (2020). The proto-west-coastal bantu velar merger. Africana Linguistica, 26, 139–195. [Google Scholar]

- Pacchiarotti, S., & Bostoen, K. (2021). The evolution of the noun class system of Ngwi (West-Coastal Bantu, B861, DRC). Language in Africa, 2, 11–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacchiarotti, S., & Bostoen, K. (2022). Erratic velars in west-coastal Bantu: Explaining irregular sound change in Central Africa. Journal of Historical Linguistics, 12, 381–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacchiarotti, S., Chousou-Polydouri, N., & Bostoen, K. (2019). Untangling the west-coastal bantu mess: Identification, geography and phylogeny of the Bantu B50-80 Languages. Africana Linguistica, 25, 155–229. [Google Scholar]

- Pacchiarotti, S., Kouarata, G., & Bostoen, K. (2024). Sound change versus lexical change for subgrouping: Word-final lenition of Proto-Bantu *ŋg in West-Coastal Bantu. Language Dynamics and Change, 14, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadmor, U., Haspelmath, M., & Taylor, B. (2010). Borrowability and the notion of basic vocabulary. Diachronica, 27, 226–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoue, P. C. (2009). Morphologie nominale et pronominale de leteghe parlé à Akiéni: Inventaires des préfixes de classes. Université Omar Bongo, Mémoire de Maîtrise. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Veen, L. (Ed.). (2014). Langues et dialectes du Gabon: Cognats et reconstructions. Available online: http://www.ddl.cnrs.fr/fulltext/Van%20Der%20Veen/Van%20der%20Veen_2014_gabon_cognats_reconstructions.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Van de Velde, M. (2019). Nominal morphology and syntax. In M. Van de Velde, K. Bostoen, D. Nurse, & G. Philippson (Eds.), The bantu languages (2nd ed., pp. 237–269). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vansina, J. (1995). New linguistic evidence and the bantu expansion. Journal of African History, 36, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, A., & Di Garbo, F. (2022). Sociogeographic correlates of typological variation in northwestern Bantu gender systems. Language Dynamics and Change, 12, 155–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).