Abstract

Despite the burgeoning Latino population in the Midwest, research on language attitudes in this region remains sparse. This study addresses this gap by examining language attitudes and beliefs towards Spanish in the Northwest Indiana region, one of the oldest Latino immigration gateways in the Midwest. Data collected from a 2018–2019 sociolinguistic survey, involving 236 participants representative of the local Latino community, form the basis of the analysis. The study aims to elucidate attitudes towards various Spanish dialects, particularly the local variety. Findings indicate widespread acceptance of the local Spanish variety, with participants viewing its divergence from Mexican or Puerto Rican Spanish as normal and inevitable. Despite perceptions of linguistic mixing with English, the community’s Spanish is valued as an effective communication tool and cultural asset, including in educational settings. This positive attitude towards a stigmatized linguistic variety suggests a preference for any form of Spanish over none, particularly in situations of low Spanish language maintenance. The study of language attitudes shows that speakers will tend to reproduce in their speech new ways of speaking that they find acceptable. This generalized behavior, in turn, leads toward linguistic change.

1. Introduction

The study of language attitudes and beliefs can reveal significant insights for understanding the dynamics of a speech community. Attitudes are the focal point of research examining the future of minority languages in bilingual contexts and the symbolic status they hold for certain societal groups. The attitudes of speakers towards different varieties and functions of Spanish, particularly towards the Spanish spoken in their community, also provide an opportunity to study the social significance of various linguistic varieties and the consolidation of norms within the community. Overall, the study of language attitudes is essential for gaining a comprehensive understanding of language use, language maintenance, social dynamics, and intergroup relations within diverse communities. Research on attitudes is particularly important in contemporary life, when rapidly increasing globalization and migration have normalized regular contact with different linguistic groups for more and more individuals and communities ().

Little research has been conducted on language attitudes in the Latino Midwest (; ; ; ; ; ), considering the exponential growth of the Latino population in the last decades. The present study is a contribution in that direction as it focuses on language attitudes and beliefs towards Spanish in the Indiana Rust Belt and the wider Northwest Indiana region, a historic Latino immigration gateway in the Midwest. The 2020 Decennial Census counted 554,191 “Hispanic or Latino” individuals in the state of Indiana; of those, 130,655, or 23.5%, of the total reside in the northwest corner of the state, just twenty miles east of Chicago.

Since their early arrival in the 1920s, the Latino community in this region has woven a rich tapestry of cultural, activist, social, and civic contributions, establishing a profound sense of belonging and home in Northwest Indiana that continues to this day. This region appears as a good case study to analyze what language attitudes may develop in such a social and historical setting and how they might differ from the situation in the rapidly growing new Latino destinations in the South and rural Midwest. This is also a particularly interesting target of research because, although Latinas/os have a long and well documented history in the industrial areas of the Indiana Rust Belt, since the collapse of the steel industry, they have increasingly moved to towns and cities where they are small minorities, a situation that is representative of the many recently formed communities in the US: “As the number of Spanish speakers grows in the U.S., so does the number of communities with small percentages of Spanish speakers, therefore making this research very important” (). The coexistence of both old and new Latino settlement patterns makes this territory particularly interesting for research.

The data analyzed was collected in 2018 and 2019 as part of a Sociolinguistic survey created by the author. Two hundred and thirty-six (236) Latinas/os from the region participated in the study, a sample largely representative of the wider Latino community. The purpose of the study is to better understand the linguistic beliefs and attitudes of Latinas/os towards different varieties of Spanish, particularly the Spanish spoken in the communities where they live. Some questions asked participants if they perceived differences between the Spanish spoken in Indiana and the Spanish spoken in Mexico or Puerto Rico and about their emotional or evaluative response to those differences. Other questions were designed to explore the relationship between language attitudes and notions of correctness and to elicit an evaluation of local varieties in terms of their level of prestige and their role as representations of ethnic identity. This method of direct measurement has been used successfully in studies that questioned the subjects about their attitudes towards different varieties of speech (; ; ; ).

Finally, the survey elicits information on attitudes towards the use of Spanish in public settings. Language is a salient marker of ethnic affiliation, and how other people may respond to or feel about that symbol can provide an indication of how the manifestation of an ethnic Latino identity is received in different settings. In this respect, preliminary findings equate different experiences to different areas, contrasting the Indiana Rust Belt to the rest of the region and the state.

1.1. The Definition and Study of Language Attitudes

Since the early work on social psychology in the 1970s, there has been much discussion about the role of attitudes and beliefs in linguistic theory. Attitudes are, according to many definitions, intrinsically evaluative. That is, they imply a positive or negative feeling about what is believed. Although some researchers limit the attitude to that evaluative or affective response, traditionally the concept of attitude includes two additional components: belief, the cognitive basis of the evaluation, i.e., the beliefs held about the attitude object; and behavior, the behavioral intentions as well as the observable reflection of the evaluation directed towards the attitude object (; ; ; ). If the three elements correlate well, we are dealing with an attitude, but if they do not correlate, we may have to conclude that we are facing three different entities.

The lack of correlation in numerous studies led () to propose a theory that does not require a necessary connection between these elements. According to this theory, people form attitudes toward an object or action based on their beliefs about the object and their evaluation of those beliefs. In turn, these attitudes influence the likelihood of a person carrying out a particular behavior related to the object or action. However, not all beliefs that a person holds about an object influence their attitude towards it in the same way, as some may be more relevant than others. Therefore, the Theory of Reasoned Action posits that people consider both the beliefs and the affective evaluations of those beliefs when forming an attitude, and these attitudes, in turn, influence their behavior.

Starting from this multiple componential structure of attitudes in general, language attitudes are traditionally defined as “any affective, cognitive, or behavioral index of evaluative reactions towards different varieties and their speakers” (). The symbolic nature of language naturally finds expression in the attitudes that people hold towards different linguistic varieties and their users: “If language has social meaning, people will evaluate it in relation to the social status of its users. Their language attitudes will be social attitudes” (). Attitudes towards particular varieties therefore reflect the attitudes that people hold towards their users (; ; ).

More recently, () advances a model for the study of language attitudes from the framework of cognitive sociolinguistics, a model particularly concerned with the study of the cognitive resources involved in processing and contextualizing language use. Using cognition as a basis, the sociolinguistic process goes from perception and meaningful understanding of societal language use to the manifestation of sociolinguistic attitudes and beliefs.

In the present study, survey questions were designed to gather linguistic beliefs and speakers’ evaluative judgments, following the basic distinction established between the cognitive component and the affective response to those beliefs, which will be more or less positive or negative (). The behavioral or instrumental component of the survey is also addressed in some specific questions and in some of the participants’ comments. On several occasions, due to the format of the survey, the explicit evaluative component is missing, and then we speak more properly of beliefs. In other cases, participants provide the attitude along with the cognitive basis or belief.

1.2. Community Background

The arrival of Mexican migrants to Chicago and the Calumet Region of Northwest Indiana dates to 1916, when Mexicans were recruited from the southwest to work as track workers for the railroads and in the region’s meatpacking plants (). Northwest Indiana was also the site of steel foundries and oil tank works, which by the late nineteenth century gave way to the steel industries that would become the main source of employment (; ). The foundation of the two main cities, East Chicago and Gary, was closely linked to the expansion of the steel industry from Chicago to the east, along the shore of Lake Michigan (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mexican Colonies of Chicago and the Calumet Region (1928). Source: ().

Steel production transformed the Chicago-Northwest Indiana region into a mecca for Mexicans migrating to the Midwest. East Chicago was home to the Inland Steel Company, the world’s largest steel plant at the time. In a decade (1914–1924), its workforce grew from 3900 to 7000 workers, and thirty percent were of Mexican descent ().

Gary was founded in 1906 by the U.S. Steel Corporation as the home for its new giant plant, Gary Works, becoming the largest company town ever built. The Gary Mills also employed large numbers of Mexicans, with 2000 at work in 1923 at its various plants (; ).

Despite endemic discrimination and an urban and highly industrial setting foreign to them, Mexicans developed a clear connection to the Calumet Region and a sense of place. In 1932, Taylor observed that hardly a decade after the first Mexicans arrived in the region, “here, in an urban-industrial environment in the heart of America, Mexicans have won a recognized place” ().

Following World War II, the steel industry enjoyed another period of prosperity that revived Mexican communities after the Great Depression. The growing neighborhoods now included not only Mexicans but also a significant number of Puerto Ricans and southwestern Chicanos recruited to address the labor shortage. But the end of the “steel boom” was just around the corner, and, squarely located in the middle of the Rust Belt, Northwest Indiana would suffer the social and economic decline that has come to be associated with the once manufacturing heartland of the nation. Until the 1970s, the great bulk of the Latino population appeared to have succeeded in reaching economic security, in large part due to the abundance of well-paying blue-collar jobs.

The vibrant Latino life that had developed in Lake County in the 1920s continued through the following decades, reflecting the needs of changing historical circumstances. Today, as much as a century ago, Latinos in this region of the Midwest continue to thrive and struggle, combining new ways of life with a century-old sense of place ().

In order to interpret how geography matters in the development of positive or negative immigrant experiences, “attention must also be paid to the history of social/power relations (broadly conceived) in particular places, which in turn help to construct and reconstruct belief systems such as race thinking as well as conceptions of nation and place” (). In this region of Northwest Indiana, Mexicans constructed in the early decades a conception of place that included them as builders and shareholders. This early self-representation set the base for the role Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos would play in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Survey

The sociolinguistic survey employed in this study included a set of open-ended questions that elicited information on language attitudes (see Appendix A). The advantage of open-ended questions is that they give complete freedom to the participant about how to respond and what to mention. The responses present the point of view of the participant in all its complexity, with a minimum distortion of words, while reducing the probability of overlooking important aspects that may not have been included in the preselected options (; ; ; ; ; ).

Open-ended questions also present their own challenges. Since there are no preestablished choices of response, the researcher needs to develop a system of classification of the data that will be based on whatever repeated patterns may emerge from the resposes. While this approach is more laborious—and it may end up with some cases that do not perfectly “fit” in any of the categories proposed—the system of classification is completely data-driven, so it arguably reflects the attitudes of the speech community more faithfully. This was the process followed in this study for the classification of the responses to each of the questions included in the survey.

One drawback that we encountered in this study is that, when given the freedom to respond as they see fit, some less responsive participants provided very simple and unelaborated answers, while others responded with comments that did not produce the evaluative judgment requested in the question. These issues could be addressed with follow-up questions when the interviewer is present, but in this case, the great majority of the participants filled out the survey by themselves, so prodding for a more complete response was not possible.

The survey questions analyzed in this study are organized around three different sociolinguistic topics. The first one is concerned with speakers’ attitudes when they compare the local variety of Spanish with the Spanish spoken in Mexico or Puerto Rico. The second line of inquiry concentrates on the attitudes and beliefs held about the local Spanish, when considered on its own, not in contrast with a different dialectal variety of Spanish. A last set of questions seeks to uncover the ideas about correctness and the linguistic ideology that may play a significant part in the language attitudes of these speakers.

2.2. Description of the Sample

The data collection took place in 2018 and 2019. To participate in the study, the respondent was to self-identify as Latina/o, be 18 years of age or older, and had to have lived at least 10 years in the Northwest Indiana region. Initially, the interviews were conducted by a group of bilingual Latina/o college students acting as research assistants. They were all born and raised in the region and could be perceived as “insiders” by members of the local Latino community. They met at homes, churches, and public libraries. Some of the interviews were conducted in Spanish, others in English, always accommodating the participant’s language preference. Early on, it became clear that, in order to gather a high volume of responses, the survey would have to be made available to individuals who would answer it independently, without the presence of an interviewer. Spanish and English versions of the survey were distributed in printed and electronic form. Participants responded in the language of their choice and returned the completed surveys. Thanks to the collaboration of individuals from the community, the survey circulated through different schools and businesses where parents, students, and workers agreed to participate.

Two hundred and twenty people (236) participated in the study: 79 men (33.4%) and 157 (66.5%) women. The gender disparity was evident from the beginning of the data collection. We tried to correct it by including additional male research assistants and by targeting specific groups and individuals. The two groups came closer, but the gender ratio of the sample still shows an overrepresentation of women. The age of the participants ranges from 18 to 85 years old. The median age in our sample is 33, which corresponds closely to the median age in 2020 (ACS 5-Year Estimates) for the Latino population in Lake County (30) and Porter County (29), the two main counties of Northwest Indiana.

One question asked about the place of residence. Because it was an open question, some of the responses did not name a particular city or town and gave a more general response, such as “Indiana” or “Northwest Indiana”. From the 205 total responses, 152 (82%) participants lived in Lake County and 34 (18%) in Porter County. These figures are very close to the overall distribution of Latinas/os in the region, according to the 2020 US Decennial Census: 76.4% of Northwest Indiana Latinos lived in Lake County, and 14.4% in Porter County. Lake County continues to be, by a very large margin, the enclave for Spanish language claimants in the region. The city with the highest number of participants in our sample is Hammond (39: 21%), as is the city with the largest Latino population in Lake County (29,370: 32%).

Another question asked about the birthplace, and the results are presented in Table 1 and Figure 2. Three-quarters of the sample, or 75% (174), were born in the United States, most of them locally: 78 in Northwest Indiana, 55 in Chicago, 9 in Indiana, and 8 in Illinois. The percentage of foreign-born people in the sample (25%) is a little higher than what the 2020 US Census shows for foreign-born Latino population in Lake County (19%). Among those who were born abroad, 41% arrived before they were 6 years old and 66% before they were 12, so most of the people who were born abroad have spent most or a significant part of their lives in the United States.

Table 1.

Place of Birth of Survey Participants.

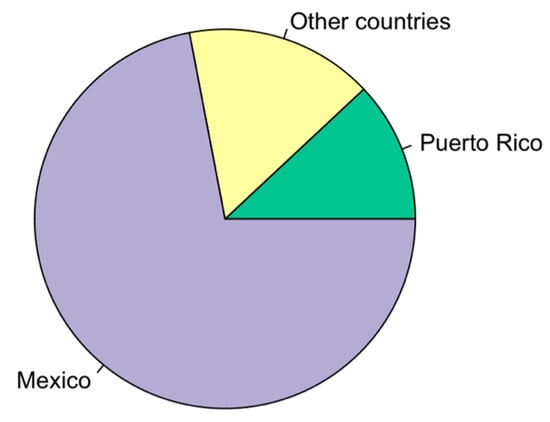

Figure 2.

Place of Birth of Foreign-born Population.

Eighty-six percent (86%) of native Latinas/os were born in Northwest Indiana or the greater Chicago area; therefore, the sample shows a clear affiliation to the Midwest.

The majority of the Latinas/os interviewed (159: 67%) are of Mexican ancestry, followed by the group of Puerto Ricans (21: 9%).1 These figures approximate the distribution of both groups in the region (2020 ACS-5 Year Estimates), where Mexicans comprise 76% of Latinas/os in Lake County and 72% in Porter County. Similarly, Puerto Ricans make up 16% of the total Latinas/os in Lake County and 18% in Porter County.

In terms of both place of birth and residence, the sample can be considered representative of the total Latino population in the region.

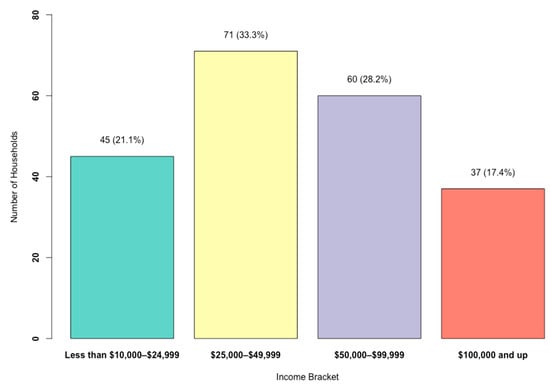

The sample is also representative of the Latino population in the region in terms of income (Figure 3). Twenty-one percent (45: 21%) of participants reported a household yearly income under USD 25,000, the same percentage reported in the 2020 ACS-5 Year Estimates for Latinos in Lake County (20%). The percentage earning between USD 25,000 and USD 49,999 is 33% (71) in the sample vs. 27% in Lake County Latino population. As the scale moves towards higher income levels, the general Latino population shows higher percentages than the participants in the study. In the interval of USD 50,000–99,999, the sample’s percentage is 28% (60) vs. 31% in Lake County, and those earning more than USD 100,000 are 22% in Lake County and 17% (37) in the population of the study. The principal discrepancy seems to be a slight overrepresentation of people in the range of USD 25,000–50,000 when compared with the numbers for the Latino population in Lake County.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Households by Income in the Sample.

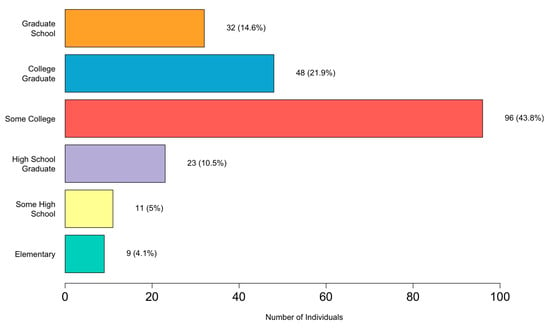

Figure 4 shows the educational attainment of the participants. Eleven participants (5%) have less than a high school diploma, and 23 (11%) are high school graduates, numbers that align well with the ratios for Latinos in the region. There seems to be an overrepresentation of higher education achievement in our sample. Ninety-six persons (94: 44%) have some college, and 80 (37%) hold a bachelor’s degree or higher. The figures for Latinas/os in Lake County Latinas/os are 27% and 14%, respectively.

Figure 4.

Educational achievement of participants.

This overrepresentation can be partially explained because the research assistants who helped with the collection of data were themselves college students who reached out to some of their peers for participation in the study. Additionally, some of the data was gathered in several high schools, so the responses by teachers may have contributed to overpopulation in those higher education categories.

As far as current occupation, the group includes 17 students, 4 stay-at-home parents, and 2 retired individuals. For those active in the workforce, the most common occupations are sales and office jobs2 (49), management, business, and science occupations (41), and service occupations (38). The rest are employed in jobs in education (22), production and transportation (13), and construction and maintenance occupations (11). The only category that shows a significant difference with the data for Lake County Latinas/os is production and transportation, which is underrepresented in the sample. Again, it is likely that this discrepancy, as well as the high number of education-related jobs, is linked to the groups contacted for the purpose of finding participants in the study. The rest of the categories, however, are representative of the Latino population of the region at large.

Finally, one question asked what language they learned first. A little over half of the group (116: 53%) learned Spanish first, 21% (50) learned English first, and the remaining 22% (51) learned Spanish and English at the same time. Within the group of those who learned Spanish first, 74% state that they learned English as children, between 3 and 8 years old. What emerges in terms of language proficiency is a population that has had a native or near-native command of English since childhood. Only 13% of the sample learned English after the age of 12. In this respect, the sample is also representative of the larger Latino population of the region: in Lake County, only 7% of Latinas/os claimed to speak English “not well” or “not at all”.

3. Results

As it was stated earlier, the questions included in the survey followed an open-ended format. Participants were not provided with a preestablished set of possible answers; instead, they responded freely, including anything they considered relevant. Once all the responses to the question were gathered, the analysis proceeded, looking for concepts that could group the responses into different categories. This process was relatively easy to conduct, as the answers repeated common patterns of linguistic perception and evaluation.

The study is divided into three parts. The first one elicits the participants’ beliefs and affective responses towards the local variety as it compares with Spanish spoken in the homeland, which in this community refers mainly to Mexican Spanish and Puerto Rican Spanish. The second part concentrates on speakers’ attitudes towards the local Spanish, this time considered without a term of comparison. The last part is devoted to the linguistic ideology underlying the attitudes of these speakers and includes some questions that target the behavioral or instrumental components of attitudes.

3.1. Local Spanish vs. Homeland Spanish

Two questions asked participants to compare the local variety of Spanish to the Spanish spoken in Mexico and Puerto Rico (Is the Spanish spoken by Mexican Americans or Puerto Ricans in your community different from the Spanish spoken in Mexico or Puerto Rico?) and then to express their affective response to that difference.3

All the responses were organized into the three categories presented in Table 2. As would be expected, the great majority of participants (163: 84%) do find noticeable differences between the Spanish spoken in Mexico or Puerto Rico and the Spanish spoken in the Indiana communities where they live. Only 18 participants (9%) state that they do not perceive significant differences (Table 2). In some of these cases, the similarity is explained because people speak the kind of Spanish they learned from relatives who were born in Mexico or Puerto Rico.

Table 2.

Responses to Question: “Would you say that the Spanish spoken by Mexican Americans or Puerto Ricans in your community is different from the Spanish spoken in Mexico or Puerto Rico?”.

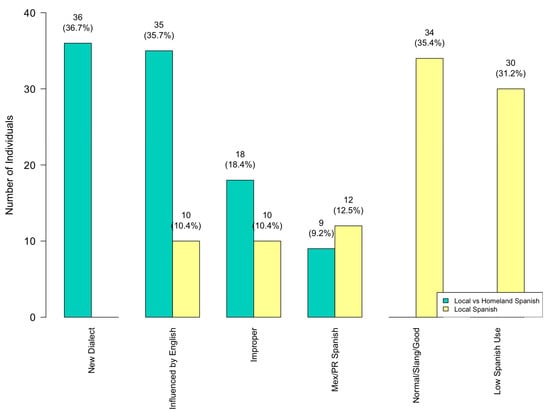

Of the 163 people who respond that the local Spanish is different, 149 (91%) provide some kind of explanation that substantiates their response. The reasons given by the participants were organized around five major ideas (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characterization of Local Spanish Variety in Responses.

Most of the explanations given are descriptive in nature and only incorporate an evaluative attitude or value judgment in the 26 (18%) responses that characterized the local variety as Improper (Group 3). The groups with the largest number of responses characterize the local variety either as a New Spanish Dialect (53: 36%) or as Influenced by English (52: 35%). Together, those two categories make up almost two-thirds (71%) of the explanations given for the difference with homeland Spanish.

When describing the local Spanish as a New Spanish dialect, participants point to the existence of different words and accents, of the same words with different meanings, and to a wider use of slang, or “street” in the Spanish spoken in Indiana. Some comments refer to variations in Spanish as it is spoken in particular geographical areas, not unlike the differences in the English spoken in different areas of the United States: “Creo que sí porque es un diferente lugar y en lugares diferentes hay diferentes acentos o palabras o cosas así. Como una persona de Chicago y una persona de Alabama tenían aspectos diferentes en su inglés creo que es la misma situación”.

Local Spanish is repeatedly characterized as “informal”, with frequent use of slang and idiomatic expressions, while Mexican Spanish is more formal and uses a more complex vocabulary. The term “slang” seems to lump together the informality of the variety, but also the use of idiomatic expressions and “sayings” that were coined in US communities. It is safe to assume that many of these new “sayings” have their origin in English expressions, but speakers do not make mention of the influence of English in the shaping of this New Spanish Dialect. One way to interpret this fact is to consider that for some second and third generation speakers who were born and raised in the United States, this new “slang” or dialect is, in fact, their native Spanish variety, which they do not contrast with an “ideal” or “pure” Spanish, devoid of English influences. Just as loanwords adapt and no longer feel foreign, the new “slang or sayings” may evolve into Spanish in the US “dialectalisms”, “It is regional slang that becomes regular vocabulary. Yes. They do not use idiomatic expressions in the same way”.

A second group of responses (52: 35%) characterizes the differences as Influenced by English. It is most often called “Spanglish” and is described as a “mix” of Spanish and English. In an illustrative rendition of the process described, one person explains that Spanish is “mixteado” with English: “Sí, porque utilisan [sic] español moderno mixtiado con inglés. Spanglish”.

Some speakers mention that they incorporate English words when they do not remember the Spanish counterpart: “I mostly speak Spanglish because sometimes I forget certain words, and of course in Mexico they are fluent”. For others, it is a natural linguistic development when speakers are bilingual and live in constant contact with English: “Yes, because we are bilingual, therefore speak Spanglish which is a mix of both”.

The responses included in this group do not incorporate an evaluative component, which was elicited in the question that followed. One Puerto Rican participant describes “Spanglish” as the US dialect spoken by both Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans who otherwise “speak Spanish very well”. These dialectal differences are obviously more salient when communicating with speakers from other Spanish-speaking countries.

Group 3 (It is improper Spanish) comprises 26 responses (18%) that characterize the differences in terms of correctness and evaluate the variety negatively (Table 3). The Spanish spoken in the local communities is “broken”, less correct, fluent, and proper than the Spanish spoken in Mexico or Puerto Rico. Some problems mentioned are a limited lexical inventory, which leads to making up “Spanglish” words, as well as errors in pronunciation. There are also remarks on the abundance of “slang”, but unlike in the responses collected in Groups 1 and 2, for these speakers, the use of slang is stigmatized as “not proper” Spanish: “The Spanish I hear here includes more slang and is improper”.I feel like Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans in my community speak Spanish very well, but at times it differs from Spanish in their perspective countries. A lot of the time, “Spanglish” is used in the States rather than authentic, straight-up Spanish. I just got back from Mexico and struggled a bit with the Spanish spoken out there. And to top it all off, Spanish in the States is different from Spanish in Spanish-speaking countries.

For a few participants (14: 9%), the differences are the result of contact between people from Mexico and Puerto Rico (Group 4: It is a mix of Mexican and Puerto Rican dialects) or from the coexistence of different Mexican regional dialects: “Mexico has many regions with different dialects, accents, and regionalisms”; “Yes. Not every word means the same to a Mexican as to a Puerto Rican”. If before speakers expressed their linguistic awareness about the influence of English in the local Spanish, now they turn to their awareness of the presence of different Spanish dialects and how that contact may impact the Spanish spoken locally. “Yes, we tend to adapt each other’s lingo”.

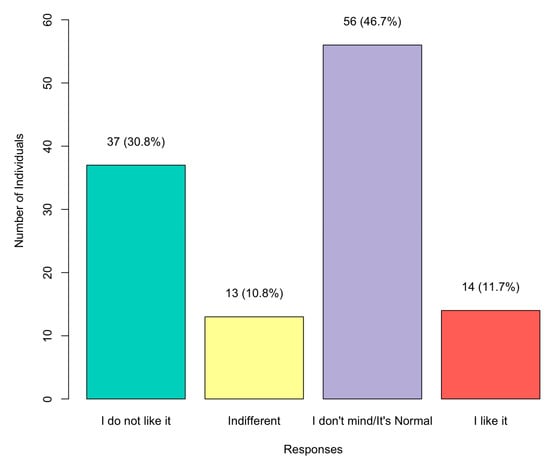

In their responses to the previous question, most of the participants simply described the nature of the differences without conveying how they valued them. A second question was included in the survey to elicit an evaluative or affective response: If you think that there is a difference, how do you feel or what do you think about that difference?

The answers obtained were organized into the five points of a continuum (Table 4) that moves from a clearly negative evaluation (37: 31%) (Group 1: I do not like it/I feel bad/It is incorrect) to the positive appreciation of the local Spanish variety (14: 12%) (Group 5: I like it/I feel comfortable/It is cool). Between those two poles, 13 (11%) participants report a neutral or indifferent attitude (Group 2: I am indifferent/Neutral/No feelings). The most common response (56: 46%) is that speakers “do not mind”, stating that the differences from Mexican/Puerto Rican Spanish are “ok”, “normal”, “to be expected” under such sociolinguistic conditions (Group 3: I do not mind/It is normal). Finally, a minority of speakers (14: 12%) provide a clearly positive evaluation (I like it/I feel comfortable/It is cool).

Table 4.

Classification of Responses to the Question: “If you think that there is a difference, how do you feel or what do you think about that difference”?

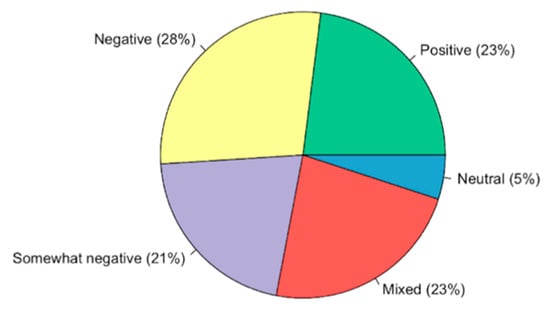

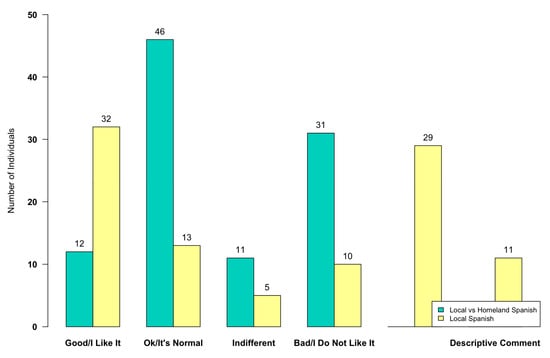

In this continuum, a clear break can be established between “negative” (37: 31%) and “not negative” attitudes (83: 69%). The results presented in Table 4 and Figure 5 leave little doubt about the prevalence of attitudes that range from neutrality (13: 11%) and acceptance (46: 56%) to positive appreciation (14: 12%). It is also true that clearly negative attitudes are far more common (31%) than clearly positive ones (12%).

Figure 5.

Classification of Responses to the Question: “If you think that there is a difference, how do you feel or what do you think about that difference?”.

While only a minority of Latinas/os in these communities endorse the local dialect unequivocally, most of the evaluations (69%) point to the unavoidable acceptance of a US Spanish variety that is different from Mexican, and Puerto Rican Spanish and whose natural development is beyond their control. Faced with that realization, attitudes can range from neutral to positive, but the majority of people do not reject or stigmatize the local variety. The differences are considered “normal”, “expected”, “inevitable”, “understandable”, and are sometimes explained in purely dialectological terms as “due to geography”, similar to the difference between British and American English: “I think the difference is normal and to be expected. People speak English in England, but it is obviously different from the English we speak”. In other cases, people go a step further from “not minding” to harboring a positive evaluation and to express a sense of pride or attachment to the local variety: “I think it makes us unique in a sense. The fact that we have to navigate between two languages is pretty impressive. It definitely shows our culture”.

Another idea that appears repeatedly when participants explain their feelings about the novelty of the local variety is that any kind of Spanish that allows speakers to communicate effectively is good Spanish. If Spanish can function as an effective means of communication, other considerations (such as correctness or prestige) do not come into play: “As long as they understand me, I don’t have a problem”. The validation of the local dialect seems to rest on a linguistic ideology that values communication over prestige.

A negative attitude towards the type of Spanish that is spoken in the region is found in 31% of the responses. This negative evaluation is anchored on many of the same parameters that appeared in the responses to the previous question. The local Spanish is “incorrect”, “not proper”, and “inauthentic”. It is a variety that “takes away” from the true language and is altogether worse than Mexican Spanish.

The affective component of language attitudes appears very clearly in some of these responses. Speakers report feeling “sad”, “disheartened” and “frustrated” in the face of the Spanish commonly used around them. The affective and behavioral dimensions of speakers’ attitudes appear in the responses of participants who reject and dislike the dialect and also encourage people to be proactive in trying to improve it: “Siento que debemos de mejorar nuestro español y practicar más”.

This part of the study includes a final question that asks people about their feelings if they were to be identified as a Mexican or a Puerto Rican speaker (If someone told you that you speak Spanish like a Mexican–or like a Puerto Rican if you are Puerto Rican, etc.–, would you take it as a compliment? Why?). The responses to this question can attest to the level of prestige these dialects may hold for the speakers and how much they identify with that dialect (Table 5).

Table 5.

Responses to Question: “If someone told you that you speak Spanish like a Mexican (or a Puerto Rican if you are Puerto Rican, etc.), would you take it as a compliment? Why?”.

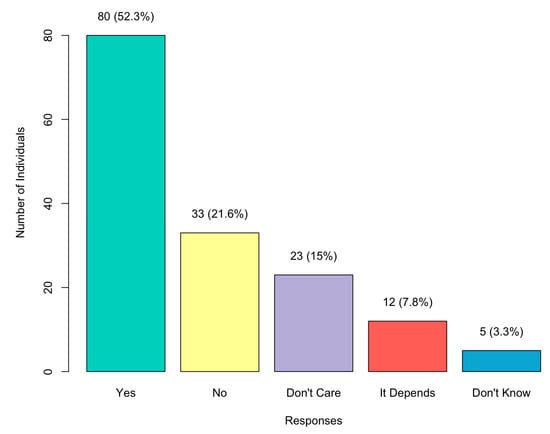

Table 5 and Figure 6 show that a little over half of the participants (80: 52%) would consider it a compliment to be told that they speak “like a Mexican” or “like a Puerto Rican”. Some participants explain their response by referring to feelings of Mexican pride, evidencing the clear connection between ethnic pride and linguistic identity. () finds similar results in New York City, where most of the speakers interviewed “were pleased to be identified as speakers of their country’s dialect” (p. 27).

Figure 6.

Responses to Question: “If someone told you that you speak Spanish like a Mexican (or like a Puerto Rican if you are Puerto Rican, etc.), would you take it as a compliment? Why?”.

In other cases, the reasons are linguistic in nature. Some people praise the Mexican Spanish variety itself, while others say they would be flattered because being identified as a Mexican implies superior Spanish language skills and fluency.

The percentage of people who responded that they would not take it as a compliment is small (33: 22%). In a few cases, it seems that participants want to distance themselves from a linguistic variety that they consider incorrect: “I would probably feel like I wasn’t speaking it right”. Others explain that they would not take the comment as a compliment because they are in fact Mexican/Puerto Rican, so to be recognized as such when they speak would just be something normal and expected, not particularly deserving of a compliment: “No, I am Mexican, I’m supposed to”. Such responses imply a positive affirmation of their linguistic and dialectal background.

A completely different explanation is offered by those who would not interpret such a comment (“You speak like a Mexican/Puerto Rican”) as a compliment, but as an offensive and racist remark: “I am sure that they say it condescendingly”, “No. I wouldn’t take that as a compliment. I think that would be a bit racist”, “Probably not, because they are stereotyping me”. In doing so, they are assuming for this question a social context that discredits and stigmatizes Mexican/Puerto Rican Spanish speakers.

The presumed social context of the interaction is also behind the responses of 12 (8%) individuals who did not give a Yes, I would take it as a compliment, or No, I would not take it as a compliment response because, for them, the choice hinges on who would be making the comment. If the comment was made by in-group members of the “same race”, they would take it as a compliment, but if the person is perceived as an outsider, “a person from Spain or from a school” or “a bigot”, it would not be taken as a compliment.

All these responses are based on the presupposition for this interaction of a social context that is hostile to Latinas/os. It is interesting to notice that such misgivings originate on different grounds. One would be the racist stigmatization of Latinas/os, and another would be the stigmatization of Latino speech by a person perceived as upholding an ideal of correctness (“a person from Spain”), or by a person associated with a setting where their speech would be stigmatized (from a school’”). These comments evidence social tensions in the incorporation of Latinas/os in the region, particularly in areas where they represent small minority populations.

The number of participants that provided a Neutral/Indifferent response (23: 15%) seemed somewhat surprising. These speakers interpret the question from a remarkably different perspective. Some feel an unquestionable legitimacy to the way they speak Spanish, making the importance of outside endorsements of the way they speak a moot point or irrelevant: “Neither as a compliment nor insult, aside from region and accent, Spanish is the same language”, “I wouldn’t take it as a compliment, but I wouldn’t get offended if they told me I sound like a Puerto Rican”. In feeling this way, they demonstrate a level of linguistic security and confidence in the way they speak.

3.2. Attitudes and Beliefs about the Local Variety of Spanish

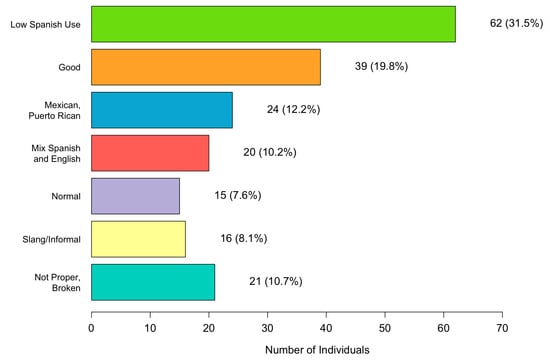

The second concentration of the study involves the speakers’ beliefs and attitudes about their local variety, but this time considered on its own, without another dialect as a point of reference or comparison (How would you describe the Spanish spoken in your community?).

Table 6 and Figure 7 show that the largest number of responses (62: 30%) make reference to the low level of Spanish language use in the places where they live. Perhaps the question was interpreted by participants as assuming that Spanish was regularly spoken in their communities, which, as they make clear, in many cases is not the case. As one person puts it, “it is hard to describe because very few people speak Spanish”. The low frequency of use is associated with living in mostly “rural” or “Caucasian” areas: “I moved to a rural white community, so it isn’t”.

Table 6.

Responses to Question: “How would you describe the Spanish spoken in your community?”4.

Figure 7.

Responses to the Question: “How would you describe the Spanish spoken in your community?”.

Some people who moved to Northwest Indiana from Chicago comment on how much more widely Spanish is spoken in the city. One person points to the fact that in suburban towns where Latinas/os are small minorities, people may shy away from speaking Spanish in public: “Ahora vivo en Munster y hay pocas familias que hablan español y si lo hablan no hablan en público. Antes cuando you viví en Chicago fue muy diferente. Muchas personas de todas las edades hablan español todavía”.

In another 24 cases (12%), participants mention the dialectal affiliation of the local Spanish to the Spanish spoken in Mexico and Puerto Rico. It is “Mexican Spanish” or “Puerto Rican Spanish”, depending on who the majority population is.

Responses also point to a blend of Mexican and Puerto Rican features in the Spanish spoken locally: “All over it is mixed between Mexican and Puerto Rican”. The perception of a blend of dialects as a defining feature of the Spanish spoken in the community suggests a metalinguistic awareness that can be attributed to the fact that in Northwest Indiana, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans have a long history of living side by side. It also shows a positive attitude towards the accommodation of features of the other dialect.

This linguistic situation, which allows for the incorporation of lexical items from the other dialect, is very different from the one described by () for the midwestern town of Lorain, OH. In Lorain, Puerto Ricans and Mexican Americans had also coexisted for over six decades, but these groups “have separate and different language ideologies and have decided against converging their linguistic varieties. There is no evidence of superficial borrowing, or influence of lexical items”. The linguistic divergence in this case is linked to a history of tensions and segregation of Puerto Ricans and Mexican Americans.

The Mix of English and Spanish appears, once again, as a salient characteristic of the local Spanish (20: 10%), as does the description of the variety as Slang/Informal (16: 8%) “learned at home, not school”. It is also called Normal (15: 8%), implying that this variety of Spanish is what they consider habitual, natural, or ordinary Spanish and does not need further specifications; it is just “Spanish”.

Finally, in 31% (60) of the cases, the responses provide a clearly positive or negative evaluation. In 39 (20%) responses the Spanish variety is considered “proper”, “good” or “very Good” Spanish. Negative evaluations (21) make up 11% and seem to be largely based on the influence of English.

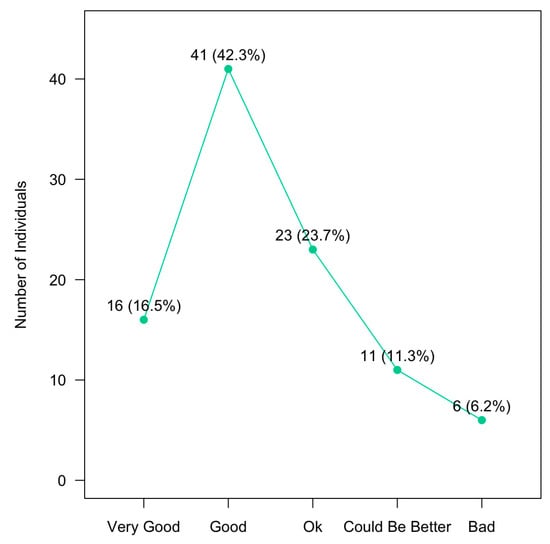

As it was done earlier when speakers compared local and homeland Spanish, the survey included a follow-up question destined to elicit the affective connection participants may feel towards the Spanish spoken in the region (How do you feel or what do you think about the Spanish spoken in your community?) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Affective/Evaluative and Non-Affective/Non-Evaluative Responses to the Question: “How do you feel or what do you think about the Spanish spoken in your community?”.

The subgroup of evaluative responses (97: 54%) conveys feelings that range from “very good” to “bad” (Figure 8). Feelings about the local Spanish are overwhelmingly positive (58%), “I feel like it’s great”, “I think it’s good, should be spoken more”. In the middle of this continuum, other responses express more neutral feelings, but still with a clear acceptance of the variety (“I’m ok with it”, “Language is used to communicate thoughts and ideas, so as long as people understand one another, I don’t mind”). From there, the scale moves to a small number of responses that convey negative feelings and judgments (17: 17%): “It is not very proper because of the lack of education in the language” and “It is poor”.

Figure 8.

Group of Responses that provided an evaluative response to the question “How do you feel or what do you think about the Spanish spoken in your community?”.

Despite the phrasing of the question, which clearly asked speakers to express “how they felt”, close to half of the responses (83: 46%) did not provide an affective or evaluative response. This is an issue that clearly should be addressed in further studies.

A large group of participants (51: 61%) responds to the question, (How do you feel or what do you think about the Spanish spoken in your community?) again with remarks about the low level of Spanish language use in their communities, or by making non-affective and non-evaluative linguistic comments (20: 24%). In 8 cases (10%), people respond that they do not have any emotional response and are “indifferent” (Table 7).

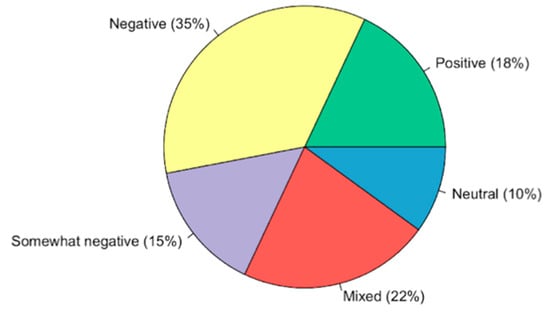

One factor that can play a role in Spanish language use is the attitude of non-Latinas/os towards the use of Spanish in public settings. Language is a salient marker of ethnic affiliation, and how people outside the ethnic group may respond to or feel about that symbol can be an indication of how the manifestation of an ethnic Latino identity is judged in different settings. These issues are addressed in one question of the study that questioned participants about their experience in Northwest Indiana: In your opinion, what is the attitude of non-Latinas/os towards the use of Spanish in Northwest Indiana?

The responses obtained often equated different experiences with different areas, contrasting the Northwest Indiana Rust Belt with the rest of the region and the state. Outside of the East Chicago and Hammond Metropolitan area, where Latinas/os are present in significant numbers, perceptions change; “Some people feel it is a positive thing worth promoting, and some think it should not happen publicly. The former tends to be from northern Lake County and the latter from the rest of the region”, “Most do not like it, in the majority of Caucasian towns”, “Depends on the area. Racism is alive and well in NWI”.

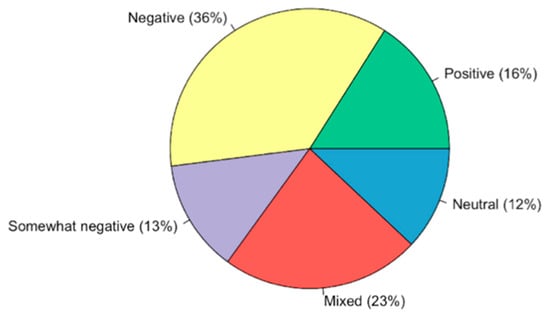

Answers were classified into five groups in a scale from negative to positive attitudes as follows: “Negative”/“Somewhat negative”/“Mixed”/“Neutral”/“Positive” (Table 8 and Figure 9).

Table 8.

Reported attitudes (N) of “Non-Latinas/os” towards the use of Spanish on Northwest Indiana.

Figure 9.

Reported attitudes towards the use of Spanish in Northwest Indiana.

Results in Figure 9 show half of the responses (50%) report negative or somewhat negative attitudes toward the public use of Spanish. Sixty-three (35%) of the participants feel non-Latinos have a Negative response towards the use of Spanish in public settings: “Negative. I live near a lot of conservatives”, “I feel now with politics, a lot of people are being so racist and prejudiced against Spanish speakers. As soon as they hear someone speaking Spanish, they immediately think that they are illegal. It makes my blood boil”, “People get very mad due to the fact this is an English-speaking country”.

Another 15% gave a response that was classified as Somewhat negative because the negativity appears qualified, as in “They don’t appreciate it because they might feel awkward”.

The other half of the participants (50%) perceive Mixed (22%), Neutral (10%), or Positive attitudes (18%): “Aquí en Indiana, hay gente que se molesta cuando hablas español y gente que le gusta para aprender o practicar a la vez”, “Indiferente. For the most part, I don’t think non-Latinos care about the use of Spanish”, “Most of them are fine with it. No problem”, “Muy buena”.

These subjective appreciations provide a glimpse into how the performance of a Latino ethnic identity is perceived to be valued by “out-group” people in real-life contexts. Overall, the perception that seems to prevail is the acceptance of bilingualism as a reality in the region, with a stronghold of the population that does not appreciate this situation.

The location where participants live appears to be a significant factor, whether they live inside (Figure 10 and Figure 11) or outside an ethnic enclave. The responses obtained from people who live inside a Latino enclave show a lower percentage of genuinely Negative attitudes, fewer Neutral attitudes, and a higher percentage of Positive attitudes. These results point to “place of residence” and the demographics associated with it as a factor affecting how the performance of a Latino identity is judged and valued in the region.

Figure 10.

Reported attitudes towards the use of Spanish in a Latino enclave.

Figure 11.

Reported attitudes towards the use of Spanish outside a Latino enclave.

As Latinas/os increasingly live in suburban settings, where they are a small minority, their exposure to a negative evaluation of their use of Spanish in public increases. At the same time, as non-Latino residents have a wider exposure to the public use of Spanish, their attitudes may also change. What seems to be clear is that Indiana Latinas/os have left the old residential patterns for good, and this will have consequences for their incorporation experiences in the region.

3.3. Ideologies of Prestige and Linguistic Correctness

The last part of the study delved into the ideologies of prestige and linguistic correctness of the speakers, as they can have a significant impact on the present and future Spanish language use in the region. Ideologies shape people’s identities and bring with them certain forms of behavior, including linguistic habits. They are essential knowledge for an approach to linguistics through the lens of societal and interactional contexts (; ).

Ideology is also crucial for following norms of correctness and appropriateness in language use. Variants may be labeled as incorrect due to their divergence from prescribed norms or their association with speech from less prestigious regions, countries, or social groups. The use of “correct” or “incorrect” in this context stems from subjective attitudes rooted in social norms rather than from objective linguistic evaluation ().

The study included a question that asked about what country or countries speakers identified as prototypes of “correct” Spanish: In what country or countries do you think people speak “correct” Spanish? Why? The main prototypes within an “international language” category usually have varieties directly associated with countries (“Spanish from Spain,” “British English”). The notion of choosing an ideal linguistic variety that differs from one’s own is not an uncommon phenomenon. The classification of language varieties is influenced by cultural, political, and economic prestige, resulting in certain languages being deemed more prestigious than others.

Table 9 shows that the countries mentioned more often are Spain (68: 31%) and Mexico (51: 23%), followed closely by “Every Country” (44: 20%). Often, speakers believe that the best variety of a language is tied to a particular territory, which features prominently in history: “Spain is the birthplace of Spanish, and that is said to be correct Spanish”, “Spain, the Spanish language originates there”.

Table 9.

Responses to: “In what country or countries do you think people speak “correct” Spanish? Why?”5.

In her work in New York City, () explains that many immigrants come to the United States with Latin American ideas of good and bad language, including the belief in “the superiority of the Spanish of Spain and the local ‘norma culta’, particularly of highland Sound American dialects” (p. 28). The strength of this linguistic alignment seems to be in part affected by the level of linguistic security. In her New York City study, she found that the more linguistically secure Latino groups agreed more strongly with the notion that “we should not learn to speak like Spaniards”. Peninsular Spanish was also selected as the most correct variety in a study that targeted the perceptions of Cubans in Miami ().

After Spain, Mexico is, by a very long margin, the country identified as the model for correct Spanish. This is not surprising, as most of the participants are of Mexican ancestry.

In 20% of the responses (44), speakers challenge the notion of correctness that underlies the question itself, stating that “good Spanish” is not confined to a specific place but is spoken across all Spanish-speaking countries (Every Country). They reject the notion that correctness is associated with any country, stating that there is no such thing as one “correct” way to speak Spanish: “Every Hispanic race has different ways of speaking Spanish. There is no correct or perfect way”, “This is an irrelevant question. There is no such thing as “correct” Spanish when comparing the way different Spanish-speaking countries use the language differently. Each is valid”.

Others (7: 3%) convey a similar idea by saying that “correct” Spanish is not spoken anywhere, as every dialect develops its own “slang” and “street talk”: “None. Does anyone truly speak any language “correctly” across the board? I feel it is human nature to develop short cuts and slang”.

Sometimes linguistic prestige is not associated with a place but with a context. Among those who think that correct Spanish can be found irrespective of geographical location, there are people (13: 6%) who base their notions of correctness on educational attainment and social status: “Throughout Spain and Latin America, where there is a higher social-economic status”,” In my opinion, higher education level Spanish from any Spanish speaking country is correct Spanish”. () study of Latinas/os living in Fortuna, California, records similar results. She finds that speakers felt that their variety was not the best but rather perceived as better the Spanish spoken by persons with more education, no matter their country of origin.

A significant finding in the results of this study is the low prestige of the Puerto Rican variety, named only four times, although there were at least 20 Puerto Rican participants in the sample. The stigmatization of Puerto Rican Spanish in the United States has been amply documented and is also illustrated in some of the comments made by participants in this survey. Similar results are reported by () in his study of language attitudes in Cleveland, OH. He finds that, although Puerto Ricans are the largest group of Latinas/os in the city and the largest group in his sample, Puerto Rican Spanish was the variety less favorably evaluated. Puerto Rican Spanish was also considered to be the least appropriate variety to be taught at schools. Spanish from Spain was the most common choice as the best Spanish variety to be taught in an educational setting (33.3%), followed by Mexican Spanish (15.3%), with only 6.3% choosing Puerto Rican Spanish.

The previous question was paired with another that asked about what country or countries speakers associated with “incorrect” Spanish (Table 10). The United States is the country that most people identify with “incorrect” Spanish, but the low percentage (44: 26%) confirms previous findings, in regard to the general acceptance and validation of the local Spanish variety. The second country most often identified with “incorrect Spanish” is Puerto Rico (20: 12%), which confirms the lack of prestige of this particular variety of Spanish. In contrast, Mexican Spanish is only mentioned five times as a prototype of “incorrect Spanish”.

Table 10.

Responses to: “In what country or countries. Do you think people speak “incorrect” Spanish? Why?”.

Thirty people (17%) explain that no country speaks “incorrect” Spanish because there is not such a thing as “incorrect” Spanish: “None, all have a proper way of using it”, “I do not. Every Spanish speaking country has its own dialect. It is not necessarily ‘incorrect’”.

The opposite idea, that “incorrect” Spanish is found in “all or most of the countries” appears 17 (10%) times. Incorrectness is related in some examples to the use of slang, “All of them. They all use slang”.

Some speakers (17: 10%) link the notion of “incorrectness” to social factors such as low socio-economic status and poor educational achievement: “People speak incorrect Spanish in low education areas of every Spanish speaking country”, “Within Spain and Latin America, where there is a lower social-economic status”.

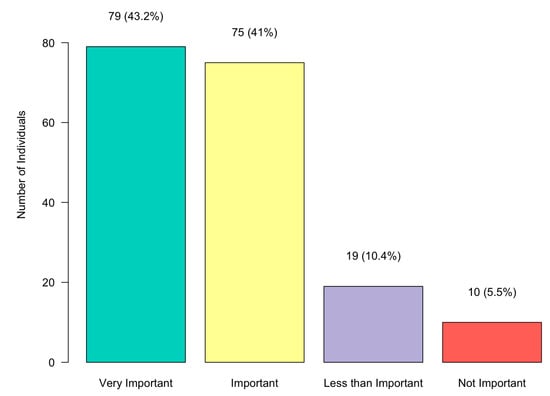

A third question asked participants about the importance of speaking Spanish correctly: How important is it to speak Spanish “correctly”? Why? This is the only question included in the study that provided a set of preestablished options for the response. Participants had to choose between the four categories presented in Figure 12 and were later asked to explain their answer in a free response format.

Figure 12.

Responses to: “How important is it to speak Spanish “correctly”? Why?”.

The overwhelming response (84%) is that speaking Spanish correctly is important or very important. They state that speaking correct Spanish is important to communicate effectively, to improve job opportunities, and because correct Spanish is part of the cultural heritage they would want to transmit to their children. It is also part of the image one portrays publicly and, as such, can be used to pass judgment on a person: “Do not want to seem uneducated”, “Again, in the Latina/o community, being able to speak Spanish fluently is important; otherwise, you are stigmatized as being ‘too American’ or ‘white’”.

This part of the study ends with a question that asks whether speakers consider the variety of Spanish spoken in Northwest Indiana to be a suitable variety of Spanish to be taught at schools: Should We Teach in the Schools the Kind of Spanish Spoken in Your Community? Why? The endorsement or not endorsement of this variety represents the choice of a course of action on the part of the speaker, so it provides an example of the behavioral component of attitudes.

Table 11 shows that more people are in favor (48%) than against (42%) of using the local variety of Spanish as the Spanish dialect to be taught at local schools.

Table 11.

Responses to: “Should We Teach in the Schools the Kind of Spanish. Spoken in Your Community? Why?”.

Some of the responses that are in favor of teaching the local Spanish in schools offer linguistic reasons: this variety is as grammatically correct or viable as any other. Moreover, “if students learn at school about Spanish dialects from other regions of the Spanish speaking world, why not learn their own regional variety as well? It is also important to learn the Spanish they will hear most often at home and in the community so that they can communicate effectively”.

In her study of Latinas/os in New York City, () finds that of all the Latino groups included, Colombians were the only ones who were mostly (56%) in favor of teaching their own dialect in US schools. In this and other measures, Colombians were the group which displayed the most linguistic security. In our data, if the 12 Do not know cases are not counted, the results of our survey show that 54% of the participants respond in favor of teaching the local Spanish variety in the schools. This finding can be interpreted as another measure of the relative linguistic security of these speakers.

Many times, the reasons adduced to favor the local variety are community oriented. Speaking the same Spanish will help people communicate better, build bridges, and tend to each other’s needs. This group of responses seems to value communication over correctness. The main thing is to know Spanish, and the local variety of Spanish will guarantee that individuals communicate effectively in their communities. Although for some people this may entail teaching a Spanish that is not formal, it is nevertheless considered preferable. “Yes, absolutely. It would benefit others so much more and even those that don’t understand much English”, “All kinds should be taught”, “Yes because in school we learn Spanish from South America, Europe, etc., which is not wrong, but focus on Spanish in our community”, “Si porque es el español que oyen en sus casas y su comunidad”. These speakers advocate for the teaching and preservation of local Spanish.

Another set of responses (42%) reject the notion of teaching in schools, a variety that they consider improper and incorrect. The school is seen as the context in which students should learn formal and standard Spanish, just as they learn standard English. The standard norm is also the “universal” form, which increases the capacity of communication. The local Spanish is considered “slang” that may hinder the chances to advance socially. Several participants believe that schools should teach the correct Spanish, and then students will “figure out little details”.

4. Discussion

Recent proposals () point to the crucial information language attitudes provide about speakers, their social position, linguistic values, and prejudices. Language attitudes can influence the acceptance of certain linguistic variants and are indicators of the possible future of variable phenomena, such as the adoption of a categorical linguistic norm. In addition, attitudes are essential for understanding and defining a speech community, which is characterized not only by the use of common linguistic forms but also by shared evaluative norms about the language.

The results of this study, as presented above, reveal what participants think and how they feel about the Spanish spoken in Northwest Indiana. In the first part of the study, they responded by comparing the local Spanish to the homeland Spanish of Mexico or Puerto Rico, while in the second part, they were asked to consider the local Spanish on its own. The findings show that there was significant overlap in the way participants responded to both sets of questions, but there are some important differences in terms of frequencies (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Characterization of the local Spanish when compared to homeland Spanish and when described on its own (%).

The negative evaluation (Improper) of the variety is more prominent when it is compared with the homeland Spanish than when it is evaluated on its own (18% vs. 10%), as is the Influence from English in the variety (35% vs. 10%). On the other hand, the percentage of responses that described Spanish as a New Dialect when compared with the homeland Spanish (34%), is very similar to the percentage that described it as Normal/Slang/Good when considered on its own (34%). In all, positive evaluations are more clearly present when the variety is considered independently.

These results are not surprising, as the survey question asked the speaker to think of the local variety as compared to a “standard” variety. Mexican and Puerto Rican Spanish carry the cultural, political, and historical prestige of a “normative model” (). This model represents the idealized set of rules that defines how the language should be used and serves as a benchmark for evaluating language use. It typically includes prescribed grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and usage conventions that are considered correct or acceptable by a community of speakers or linguistic authorities and employed in educational contexts, official communications, and the media.

When evaluated according to this ideology of standardization, varieties that deviate are more likely to be deemed “incorrect” or “not pure”. Such deviations are often vocally denounced by people in positions of power and influence, reinforcing the ideology of what is “good” and “bad” language.

The stigmatization of the Spanish spoken in the US is often based on the influence of English. () reviews the linguistic ideology promoted by Latino individuals of influence (writers, politicians, reporters, etc.) and illustrates how the influence of English over Spanish has a long history of stigmatization, leading to the definition of a variety with English influence and borrowings as defective or deteriorated. This ideology of language standardization has sometimes been used to racialize the linguistic stigmatization of Latinas/os (). () explains how the speech of Puerto Ricans in New York City is, in fact, racialized “whenever an accent, ‘bad’ grammar, or ‘mixing’ are equated with bad habits, laziness, and speech that is somehow not language.” A group’s language variety can be characterized as an invaluable resource or as a permanent deficit, even as a state of “languageness” that questions the group’s linguistic capacity altogether ().

The study of language attitudes and beliefs about language varieties has shown that the perceptions of nonlinguists are often widespread and extend to teachers and language students. These perceptions can be so strong that they influence behavior even when theoretical knowledge contradicts them. Such beliefs and attitudes significantly impact social behavior and institutions, thereby shaping speech communities internally (; ). School is one of those institutions that disseminate linguistic ideologies, some of them fostering a sense of linguistic insecurity among speakers, as illustrated by the following comment made by a participant of the study: “una de los maestras de español en mi escuela dijo a muchos de mis amigos que saben hablar español que su español es ‘street’ y ‘inproper and incorrect’”.

In her study of the Puerto Rican community of Brentwood, Long Island, () finds that 82% of the adults claimed to code-mix English and Spanish. When asked about their attitudes towards mixing, 24% chose the response “it is good”, 39% chose “it is bad”, and 36% said they “do not know”. Most of those who considered it a problem portray the influence of English as a sign of linguistic deficiency, but others recognize its usefulness, and some voice very positive feelings about it. Torres concludes that, although most Puerto Rican parents and students code-mix, they are critical of this linguistic behavior. For many, it is a sign of linguistic deficiency, and “they understand that is one of the reasons that their speech is stigmatized” (p. 27). The percentage of negative evaluations of English influence in the present study is very similar (35%) when the question involves the comparison with homeland Spanish. Again, positive attitudes towards the usefulness of this “mixed” variety are more prominent when the variety is evaluated on its own.

In descriptions of the local Spanish, 30% of the responses refer to the low use of Spanish within the community. These results describe a situation where positive attitudes towards the language are not associated with Spanish maintenance and use on the part of the speakers. Research shows that positive attitudes towards Spanish and Spanish language maintenance do not necessarily go hand in hand. In a study of attitudes across multiple generations of Mexican Americans in Los Angeles, () observed that commitment to language maintenance, including participation in activities promoting Spanish and Mexican culture, significantly decreased with longer family residence in the United States, despite consistently positive attitudes toward the Spanish language and Mexican culture across all generational groups. Similar results were obtained by () in his study of the attitudes of Puerto Ricans in Central Florida and New York City: “language is adopted as a symbol, but its maintenance is not necessarily adopted as a behavior of practice” (p. 78).

As speakers distance their Latino identity from the use of Spanish, issues of correctness lose relevancy. () find that in Chicago, Puerto Ricans’ and Mexicans’ negative linguistic evaluations of the other group peaked among second-generation participants and were almost nonexistent among third-generation participants. They explain that the criticisms were based on an ideology of language standardization, which “seems to be losing ground in G3, very likely due, in part, to a loosening of the bond between the Spanish language and Latino identity. This decoupling of language from ethnic identity permits a wider variety of individuals to claim latininidad but also reflects and sustains ideologies that permit Spanish loss” (p. 30).

The comparative analyses of the responses obtained in Local vs. Homeland Spanish and Local Spanish were also conducted for the question that elicited an affective or evaluative response (Figure 14). In this case, there is also an overlap in the responses collected.

Figure 14.

Evaluation of the local Spanish when compared to Mexican/Puerto Rican Spanish and when described on its own (%).

() explain that linguistic variables have multidimensional connotations and evaluative judgments are not necessarily uniform across different dimensions. In their research, they find that, in an objective and impersonal dimension, a standard variant is evaluated positively, but in a subjective and personal dimension, the same variant does not receive a uniformly positive evaluation. This same principle can be applied to the evaluation of linguistic varieties in this study. When participants compare the local variety with “normative models” like the Spanish spoken in Mexico/Puerto Rico, the percentage of negative evaluations (31%) is much larger than when they assess local Spanish on its own (10%). The first case involves an objective dimension with connotations of power and prestige, while the other is a subjective and community-oriented dimension where ethnic solidarity connotations prevail. Positive evaluations of the local variety show the same relationship: 32% think the local Spanish is good when evaluated on its own, compared to 12% when contrasted with homeland Spanish.

The stigmatization of the local speech arises primarily when compared with normative varieties. However, when the local variety is compared to Mexican or Puerto Rican Spanish, what prevails (46%) is a qualified positive attitude that views the differences as simply “normal”. () indicates that in popular language theory, language is viewed as a concrete reality existing outside the individual. Those closely associated with this concept of language, such as academics, politicians, and teachers, use it in a “perfectly correct” or “model” manner. On the other hand, those who do not have this direct connection use the language in a more “normal” manner. “In fact, when people are asked about their way of speaking, the vast majority of people respond that they speak ‘normally’” (p. 196). Once the way of speaking departs from that “normal language”, the variety is perceived to be “deviant” or contain “errors”.

The study of attitudes has been the focus of many investigations aimed at predicting the future of minority languages within bilingual contexts. In these situations, it is not uncommon for a monolingual majority group to develop negative attitudes toward the minority language. In regards to Spanish in the US, () state that “en la actualidad los hispanos aseguran que, cuando hablan español frente a un anglohablante, la reacción no es hostil. Cuando lo es, los hispanos parecen sentirse seguros y reafirman su derecho a comunicarse en español” (p. 95). While this may be true in areas with a high concentration of Latinas/os, the results from this study show clear differences in the experiences of Latinas/os, with a reported perception of a hostile environment towards the public use of Spanish in places where they represent small minorities.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study show that the vast majority of speakers (84%) perceive a clear difference between the Spanish spoken in their community and that spoken in Mexico or Puerto Rico. For some (36%), the difference is explained in terms of the emergence of a new Spanish dialect. The results leave little doubt about the acceptance of the local variety by most participants. One idea that emerges is that the development of a US Spanish variety that is different from Mexican or Puerto Rican Spanish is, in the words of the participants, “normal”, “unavoidable”, or “to be expected”, “not something we can control.” The differences are “inevitable unless one constantly travels to Mexico or Puerto Rico,” and are sometimes explained in purely dialectological terms as “due to geography” and likened to the distinction between the English spoken in the United Kingdom and American English. Another 35% state that the main reason for this difference is the interference with English, which in itself does not imply a negative evaluation.

Languages and their speakers are influenced by the cultural, communal, group, and situational environment. These environments set the stage for language use by the speaker who dwells in them and perceives them in different ways. From this perspective, it could be argued that speakers living in a situation of language contact with English value positively a “non-standard” variety of Spanish because this is the variety that prevails in their community. Awareness and knowledge of language varieties different from our own are gained through education and increased interaction with speakers from diverse backgrounds. Those speakers who have not studied Spanish in an educational setting and are not regularly exposed to the normative variety in their daily linguistic interactions do not feel under a strong pressure to conform to a normative ideal.

By valuing this variety positively, speakers contribute to the survival of the language and, with it, to the affirmation of their Latino identity. In the framework of network sociolinguistics, it could be said that in this Latino community “small world networks” prevail over “big world networks”. The former are the “personal networks of a speech community’s members, and within them occurs a dynamic of identity, variation, and change”, while the latter are networks that unify language and communication patterns and “would include media networks, created by major media consortiums, able to reach all members of a community and even to penetrate different natural and sociocultural environments” (). The conflict between the values attributed to each of these networks is expressed in the different attitudes toward the Spanish spoken in the community.

The findings of this study show that when the local Spanish variety is compared with that of Mexico or Puerto Rico, 31% of people consider it bad or incorrect. However, when evaluated on its own, the community speech receives a largely positive assessment (78%), with only 10% of participants expressing negative attitudes. Several studies on reactions to different varieties of Spanish indicate that Mexican Americans in the Southwest () and Puerto Ricans in New York (), especially the younger generation, appreciate their local varieties, at least in certain situations. In these states, the total number of Latinas/os, the percentage they represent in the total population, and the degree of linguistic loyalty is much higher than in Northwest Indiana. However, despite these demographic differences and the lower degree of Spanish language use in Northwest Indiana, the community’s dialectal variety of Spanish receives a clear positive evaluation.

This positive endorsement is connected to the symbolic value attached to heritage languages and to the history of the Latino community in Northwest Indiana. In addition to being a means of communication, language is also a symbol around which a social group articulates, thereby acquiring symbolic value for a collective of individuals. A positive attitude towards any type of Spanish represents the affirmation of the heritage language as a symbol of a Latino ethnic identity. Additionally, Latino communities that have been anchored in a well-defined geography over a long period of time go through many changes, but through them they preserve a sense of belonging to the place that is enacted in many social, cultural, economic, political and linguistic experiences. Thus, the concept of "place" and a strong sense of belonging, rooted in historic Latino settlements, can play a crucial role in validating the local Spanish as an integral part of Latino identity in the region ().

It is important to note that this positive attitude represents the acceptance of a variety that speakers characterize as “mixed with English” and where elements of Mexican and Puerto Rican Spanish “are blended”, that is, a variety largely stigmatized in the United States. It seems that the low level of Spanish language use and, in some cases, the limited knowledge or interaction with the standard varieties acquired through formal schooling have contributed to the prevalence of an attitude that values the prevalent variety and considers ‘any’ Spanish better than ‘no’ Spanish at all.

Half of the participants (50%) believe that non-Latinas/os in the region are somewhat “bothered’ or “do not like” Spanish being spoken in public settings. Only 18% of the responses report a positive attitude towards Spanish. The rest perceive the attitudes of non-Latinas/os as “neutral” (10%) or “mixed” (22%). When bilingualism and the use of vernacular languages are stigmatized nationally and locally, an effective defense of the language may be the acceptance and positive evaluation of the only Spanish that the community can guarantee, the one that is spoken daily among community members. According to (), although linguistic change appears to conflict with linguistic loyalty to Spanish, in reality, these changes represent a successful strategy for maintaining Spanish among second- and third-generation speakers.

For 31% of the speakers, the prototype of “correct Spanish” is found in the Spanish spoken in Spain, while Mexican Spanish is chosen in 23% of the cases. Another 20% state that a specific place cannot be mentioned, or that “good Spanish” is spoken in any Spanish-speaking country. The findings of this study corroborate the stigmatization of Puerto Rican Spanish in the United States. Only 2% of speakers chose this variety as “correct Spanish”, while 12% considered it a prototype of “incorrect” Spanish.