1. Introduction

Consonant clusters are linear sequences of consonantal units occurring before or after the nucleus of a syllable and can be defined on the level of graphemes, phones or phonemes (

Gregová 2010, p. 79). The composition of such a sequence is firstly determined by the Sonority Sequencing Principle (

Selkirk 1984, p. 116), which is considered as a linguistic universal. However, there are also language-specific phonotactic rules: such rules might forbid certain consonant combinations, but they can also allow violations of the Sonority Hierarchy (

Alber and Meneguzzo 2016, p. 27).

That particular phonotactic rules and preferences do not only apply to languages but also to dialects is shown by

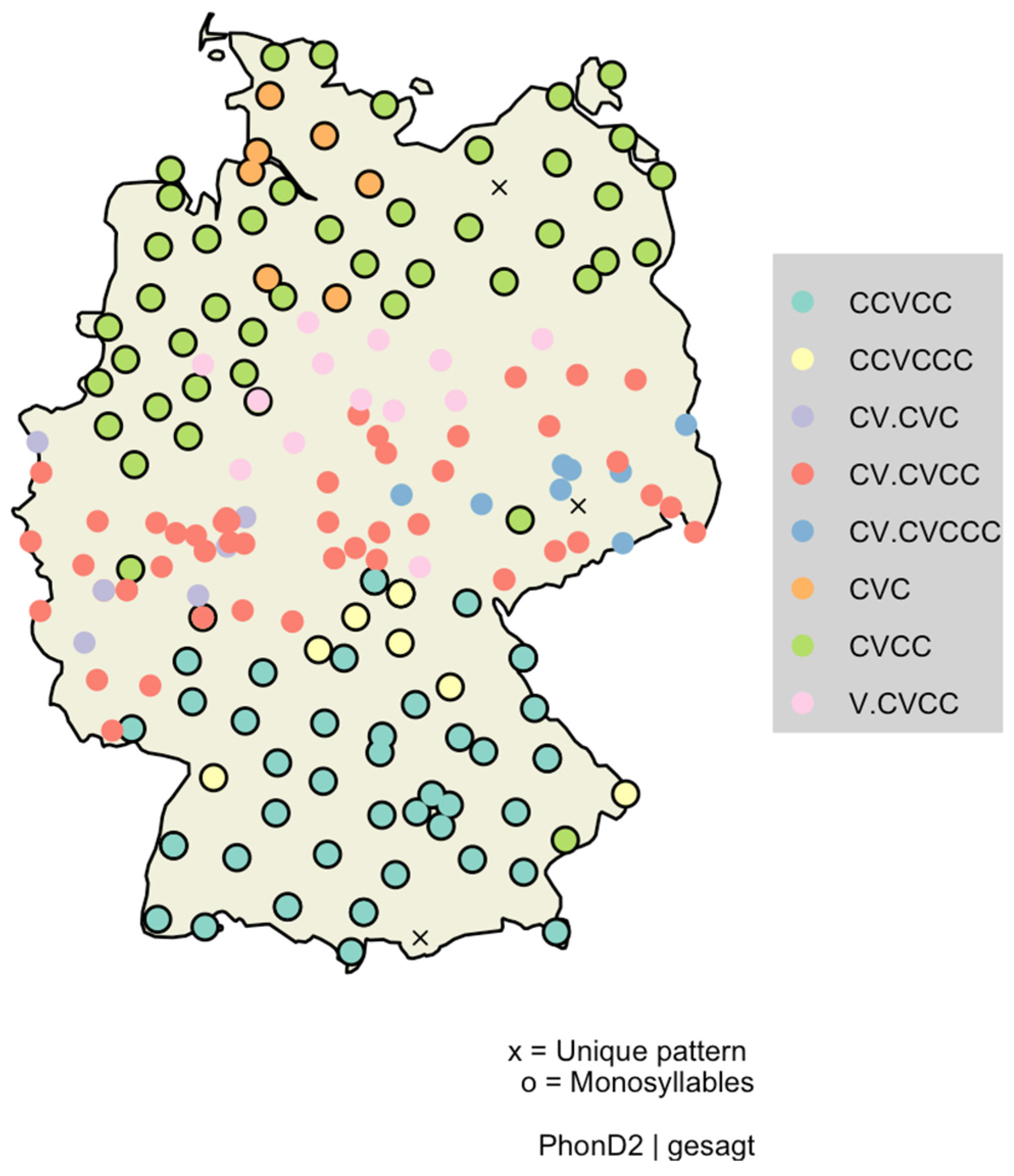

Lameli (

2022, pp. 262–66) in describing a North–South divide of consonant clustering probability in monosyllabic words in the dialects spoken in the Federal Republic of Germany. From the Low German to the Upper German dialects, the consonant clustering probability was found to increase. One example of how this increase manifests in the data is the way the lemma

gesagt, ‘said’, is realized in the examples (1)–(6) from different areas.

| (1) | zɛçt (Hohwacht, North Saxon, LG); |

| (2) | əzɛçt (Astfeld, Eastphalian, LG); |

| (3) | jəzaːt (Siebenbach, Mozelle Franconian, WCG); |

| (4) | gəzaːxt (Linz, Thuringian, ECG); |

| (5) | gsaIt (Bempflingen, Swabian, WUG); |

| (6) | gsɔkt (Peterskirchen, Central Bavarian, EUG). |

As illustrated by these examples

1, there are not only differences in syllabicity (mono- vs. bisyllabic) and consonant clustering (no clusters, onset and/or coda clusters) but also in whether they are realized with a short or long monophthong or a diphthong.

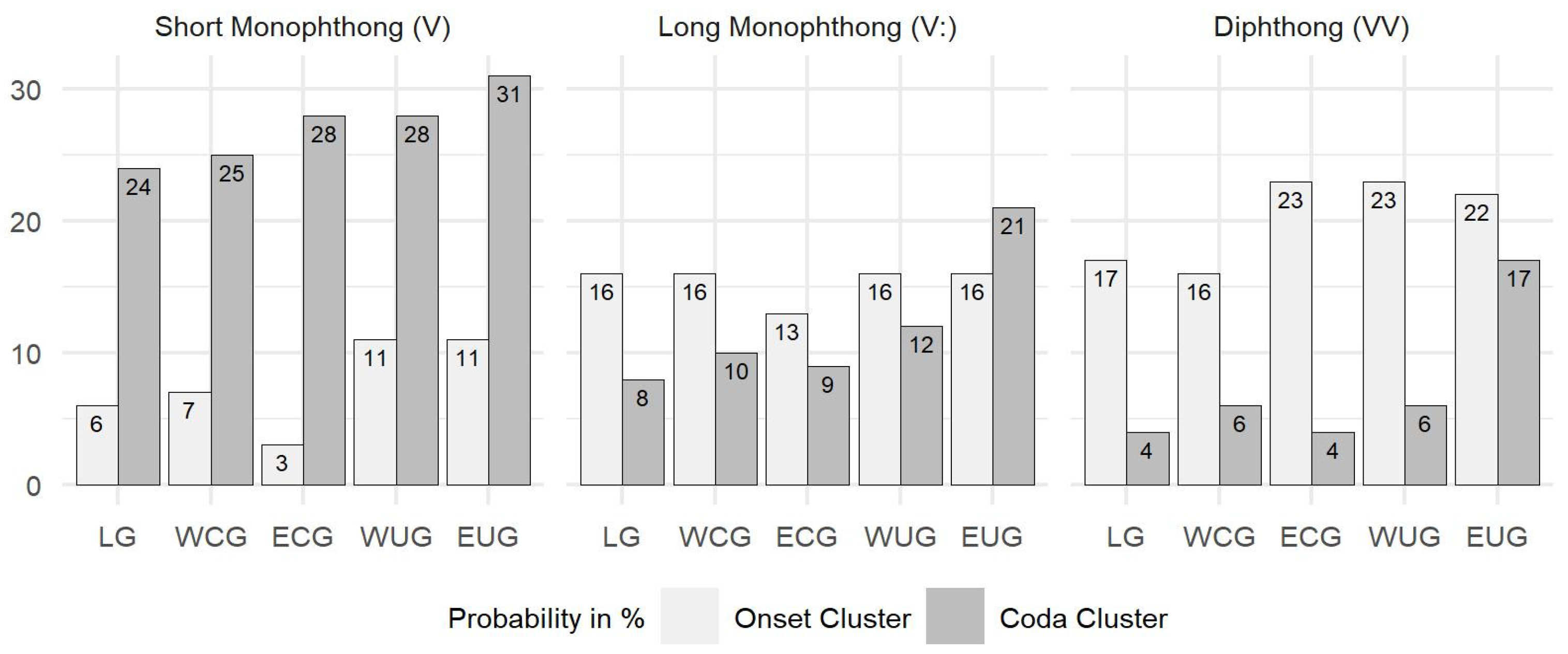

Thus, the question was raised in

Lameli and Link (

forthcoming) how the spatial North–South increase interacts with these three vowel types (V, Vː, VV). The results from

Lameli and Link (

forthcoming) given in

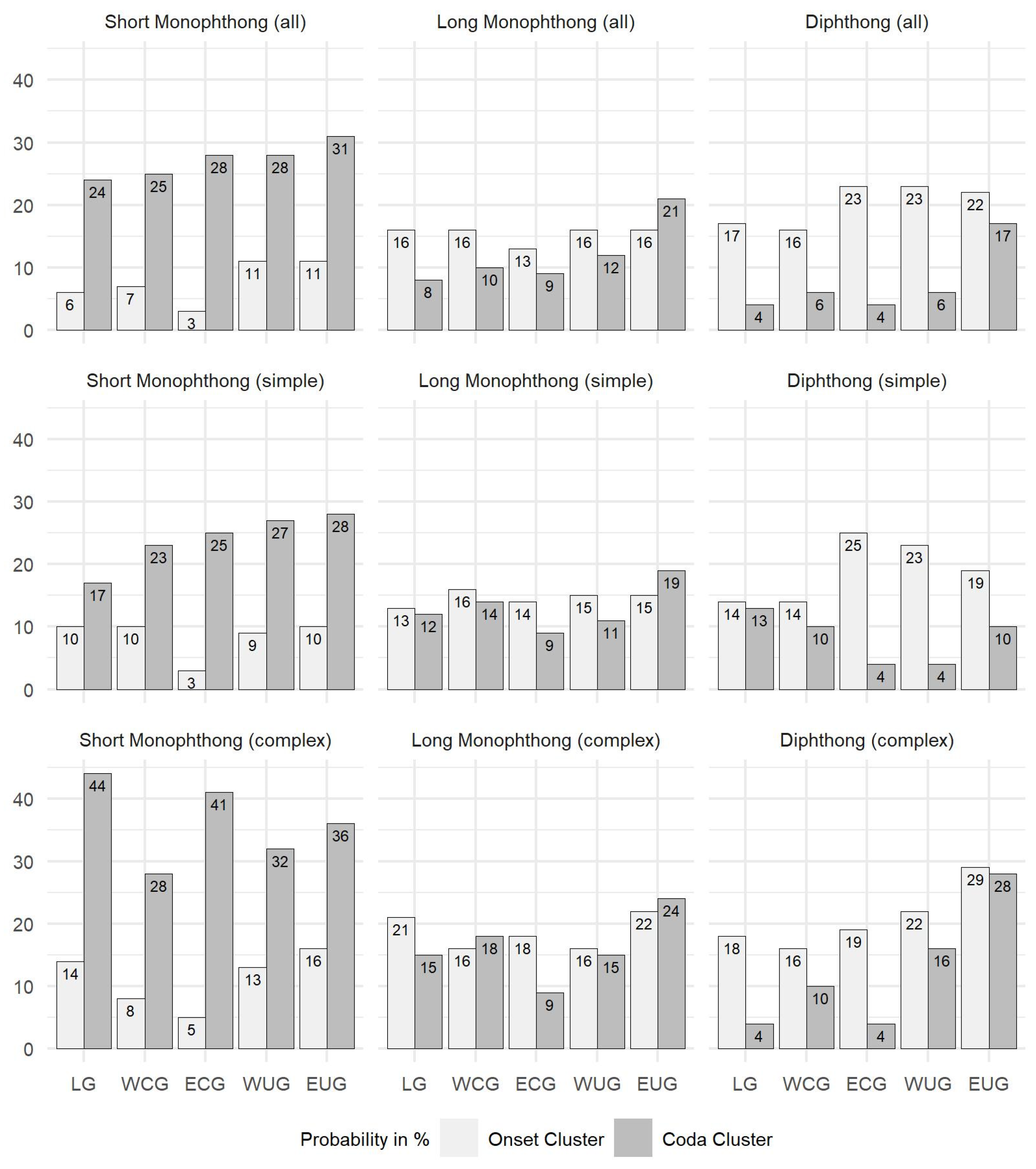

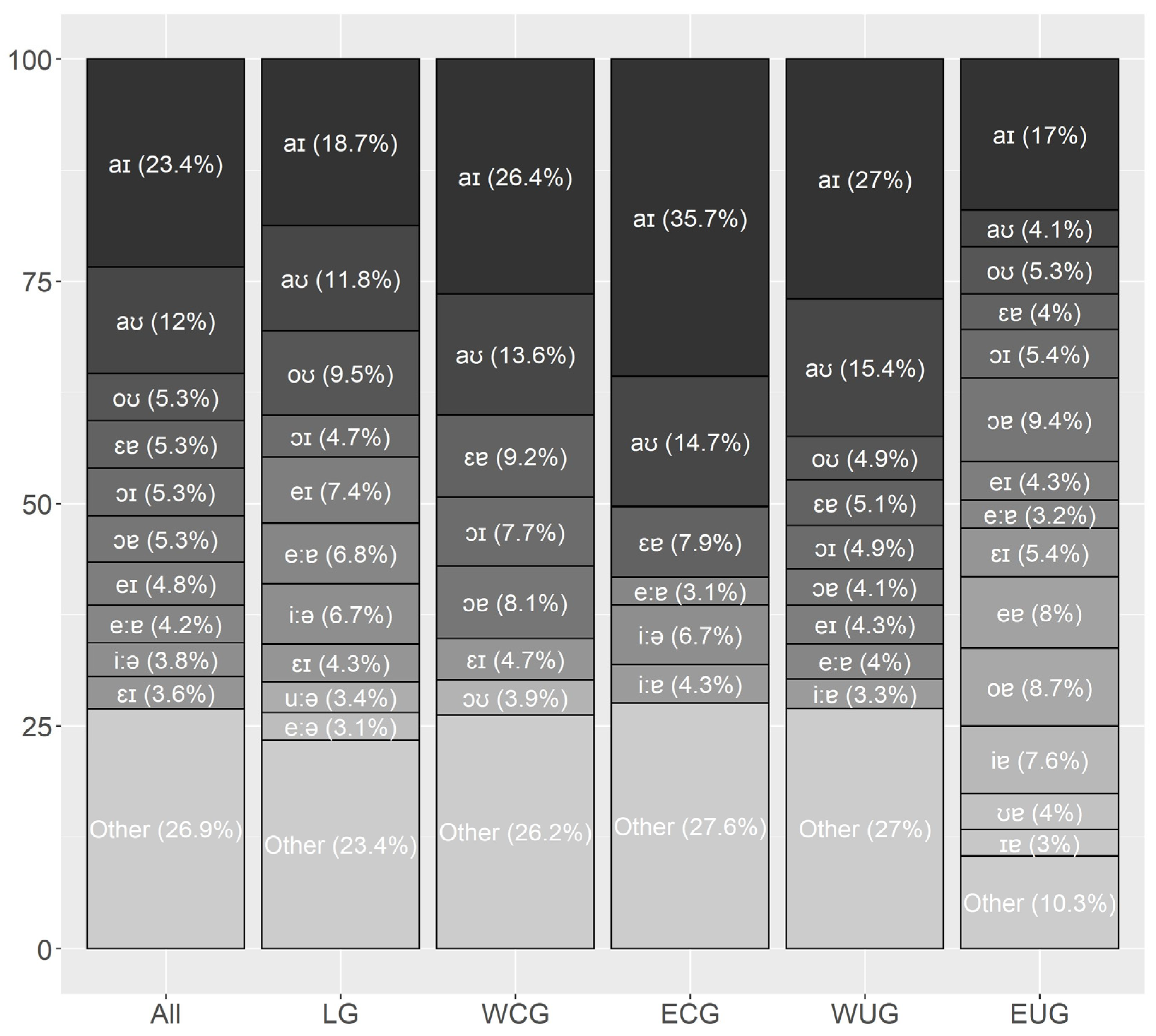

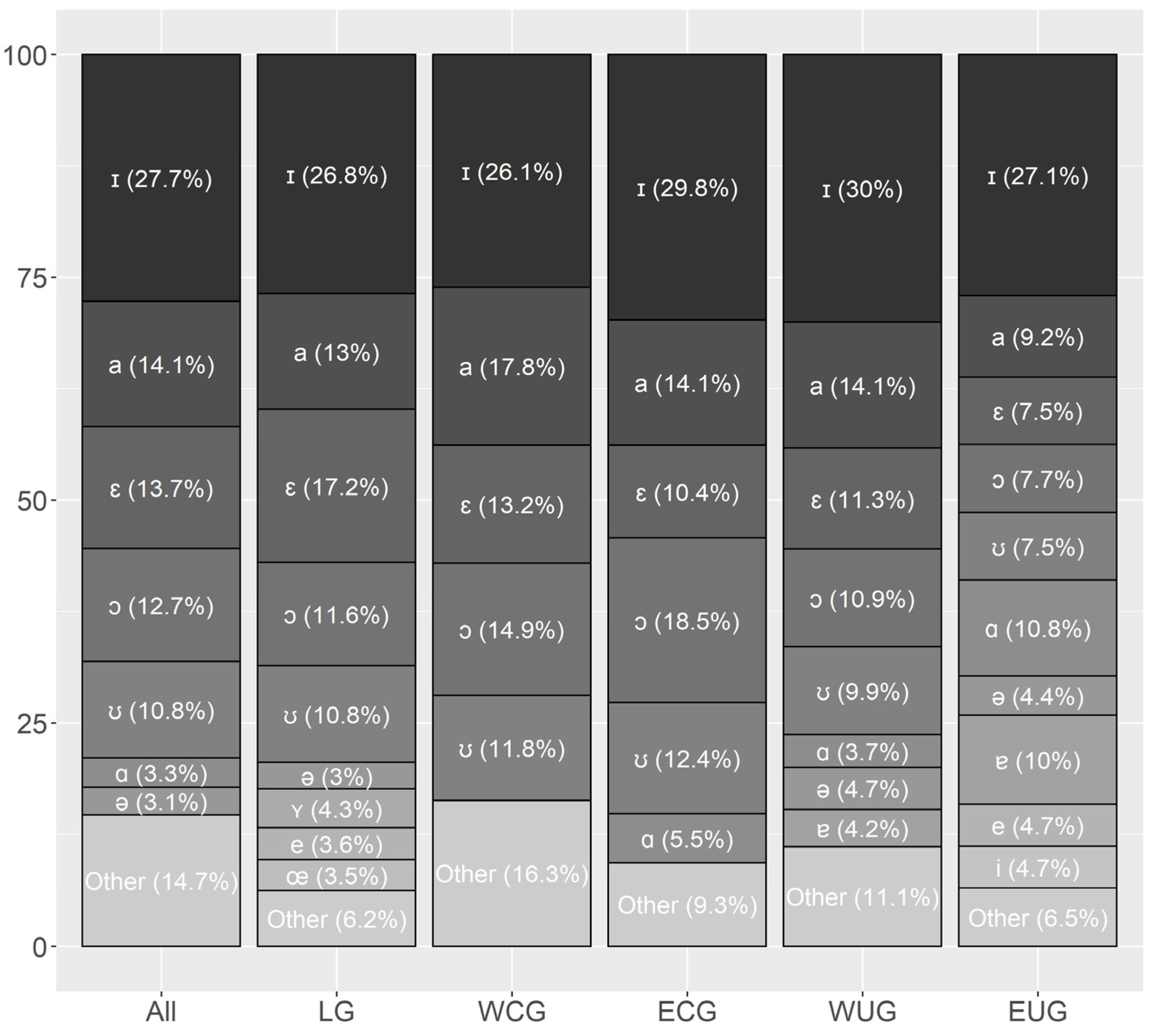

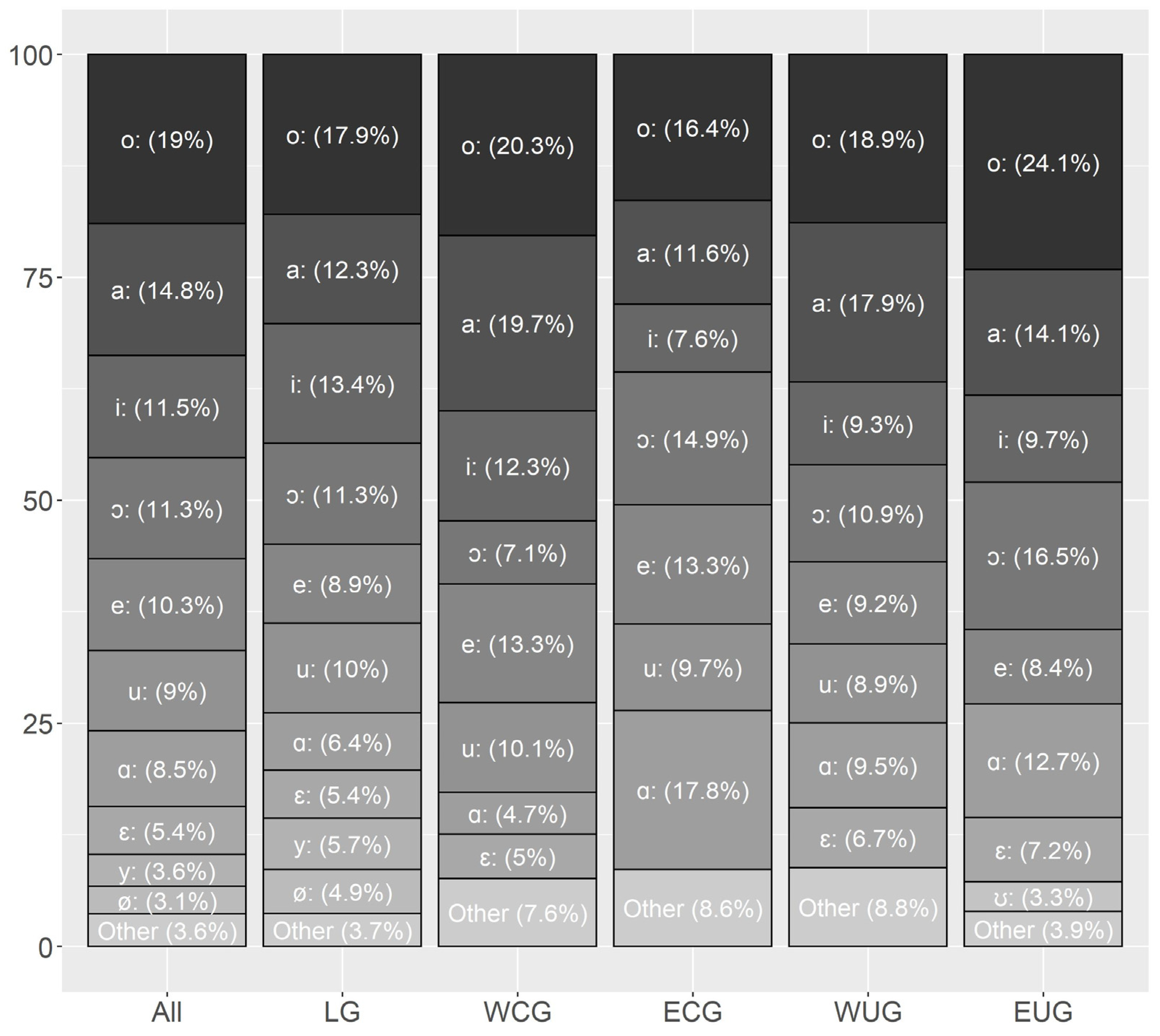

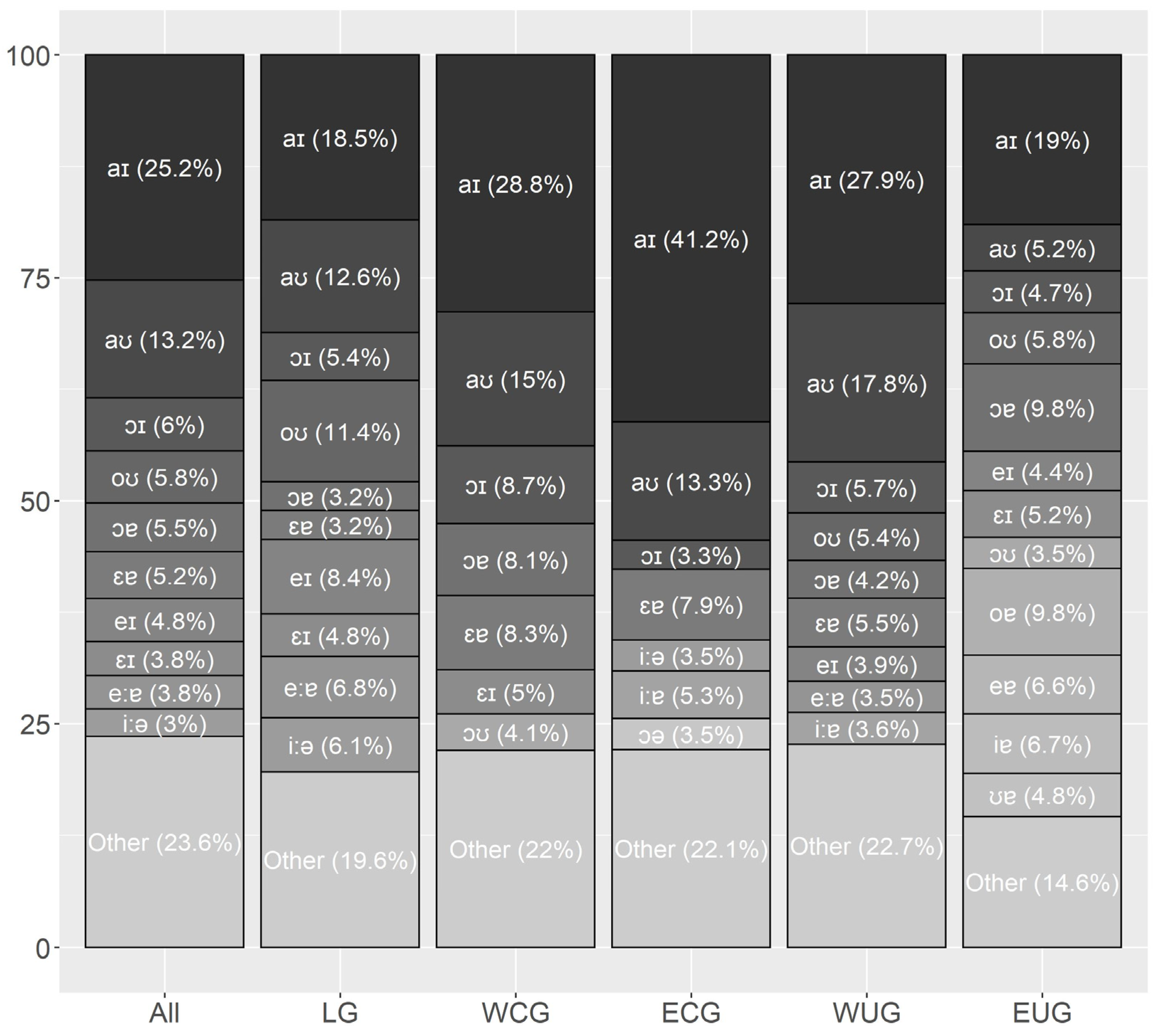

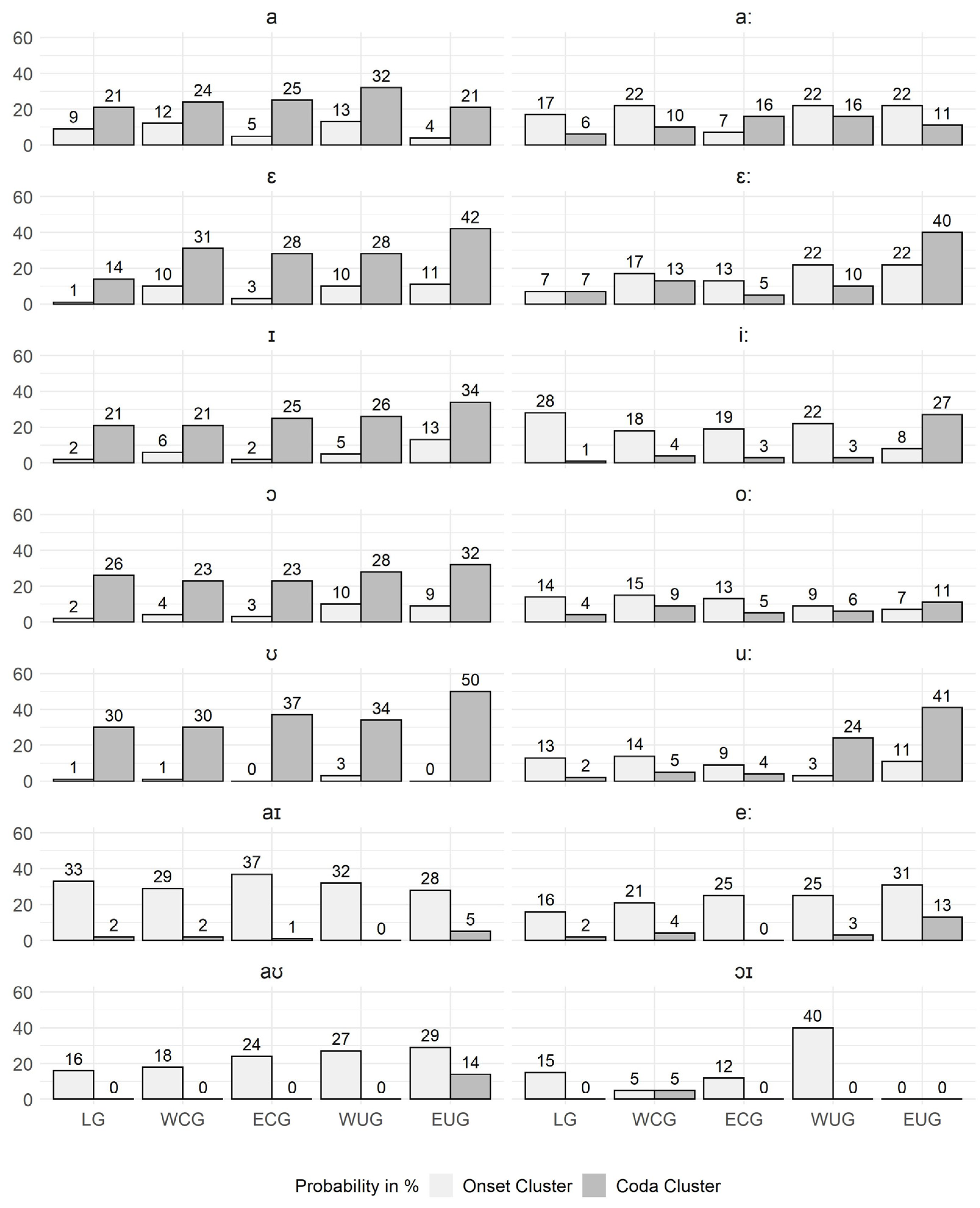

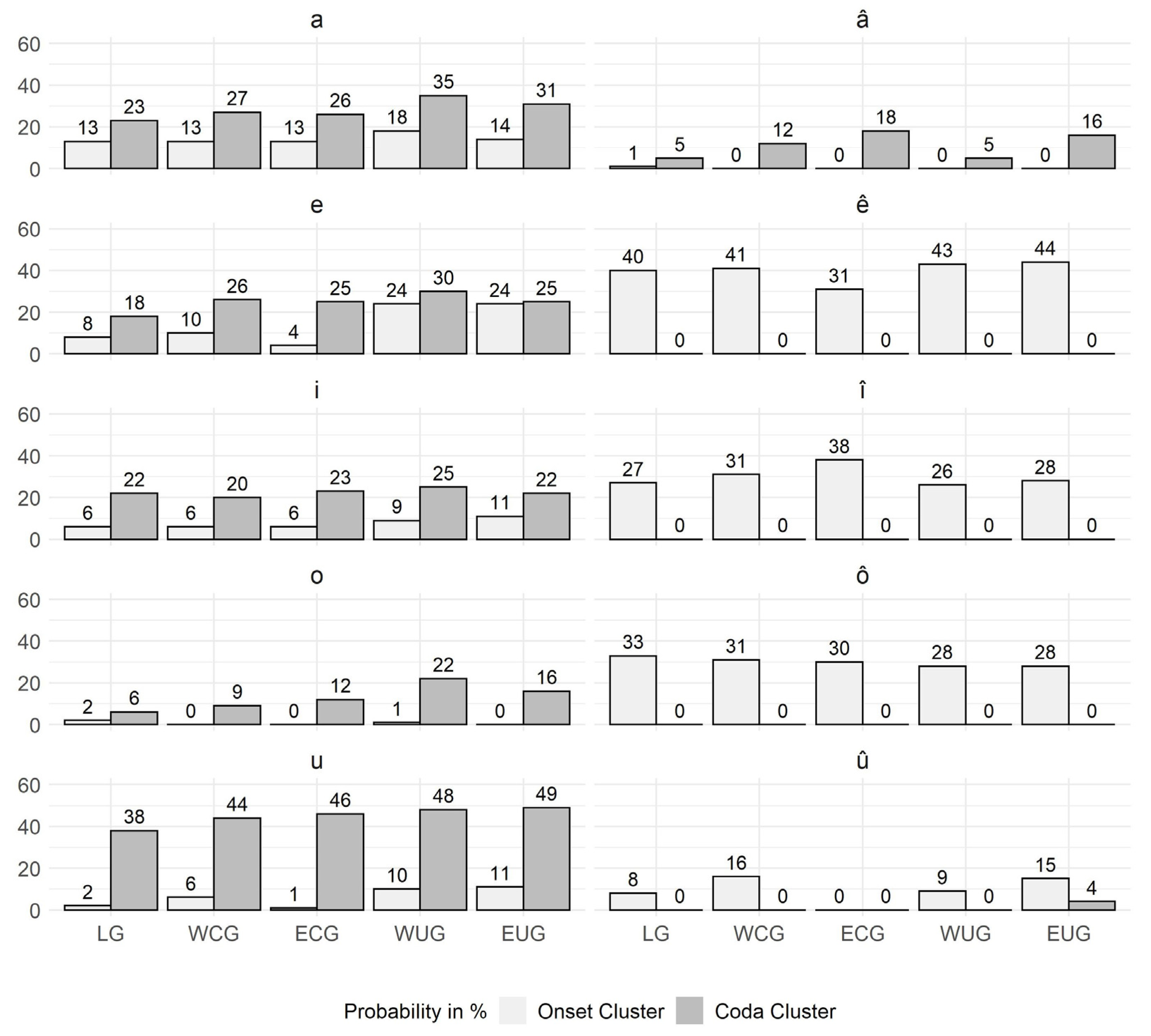

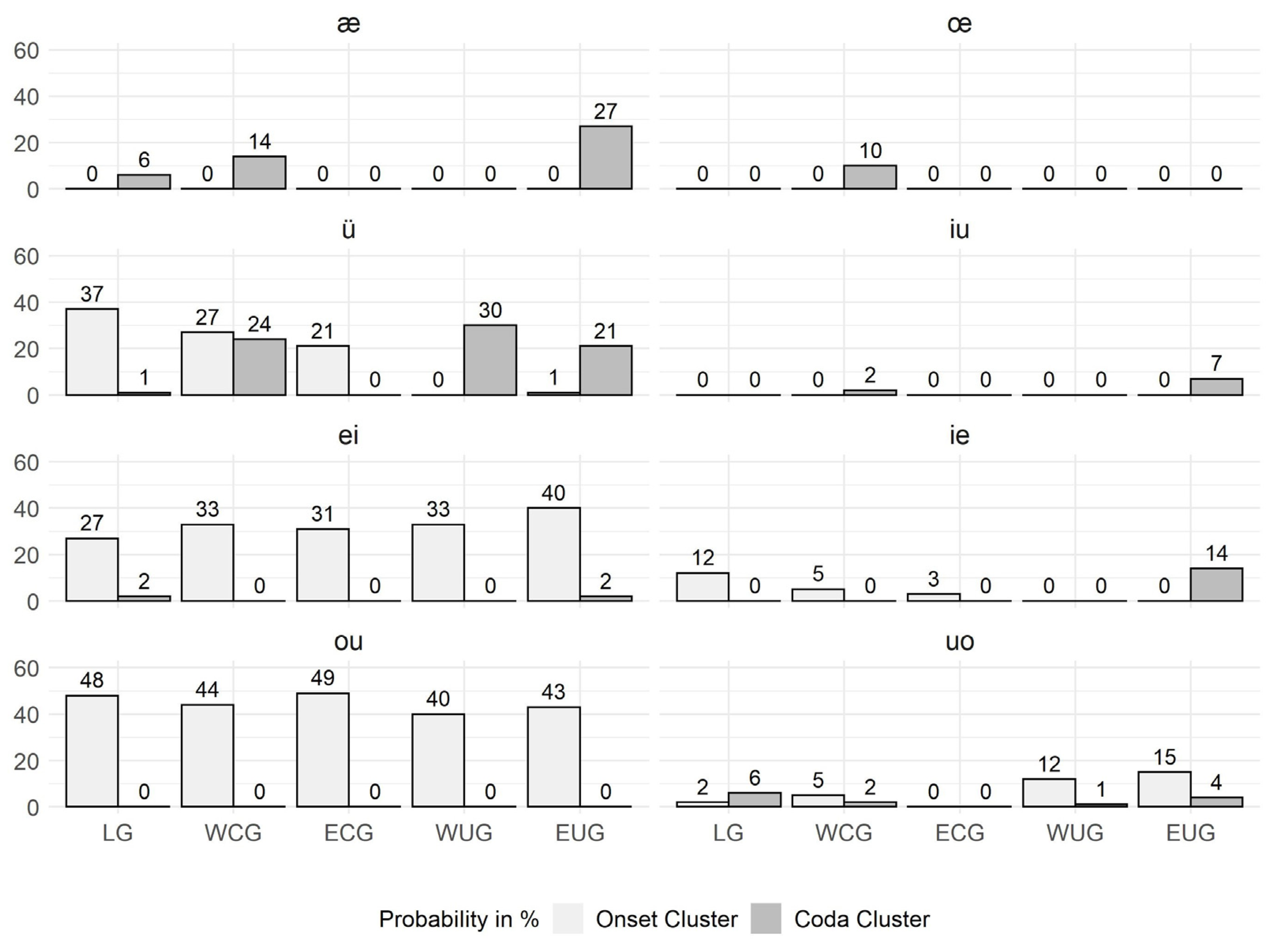

Figure 1 reveal that although the North–South increase is present in all vowel types, they differ in terms of the preference of the cluster position: the short monophthongs prefer coda clusters, which contrasts with the onset preference of the diphthongs, and the long monophthongs have a more balanced pattern with a slight onset preference, except in East Upper German (EUG), which prefers coda clusters.

- 1

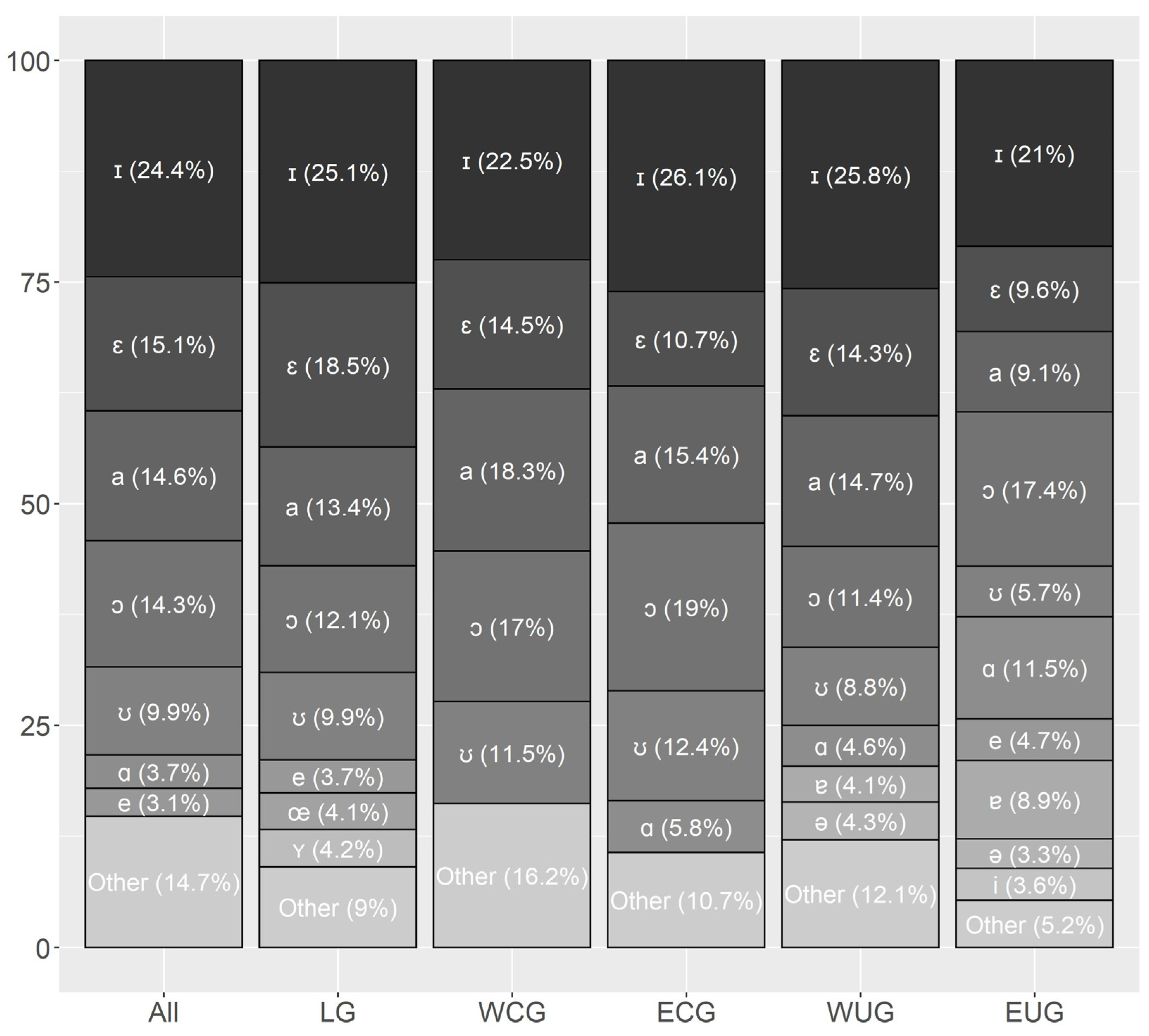

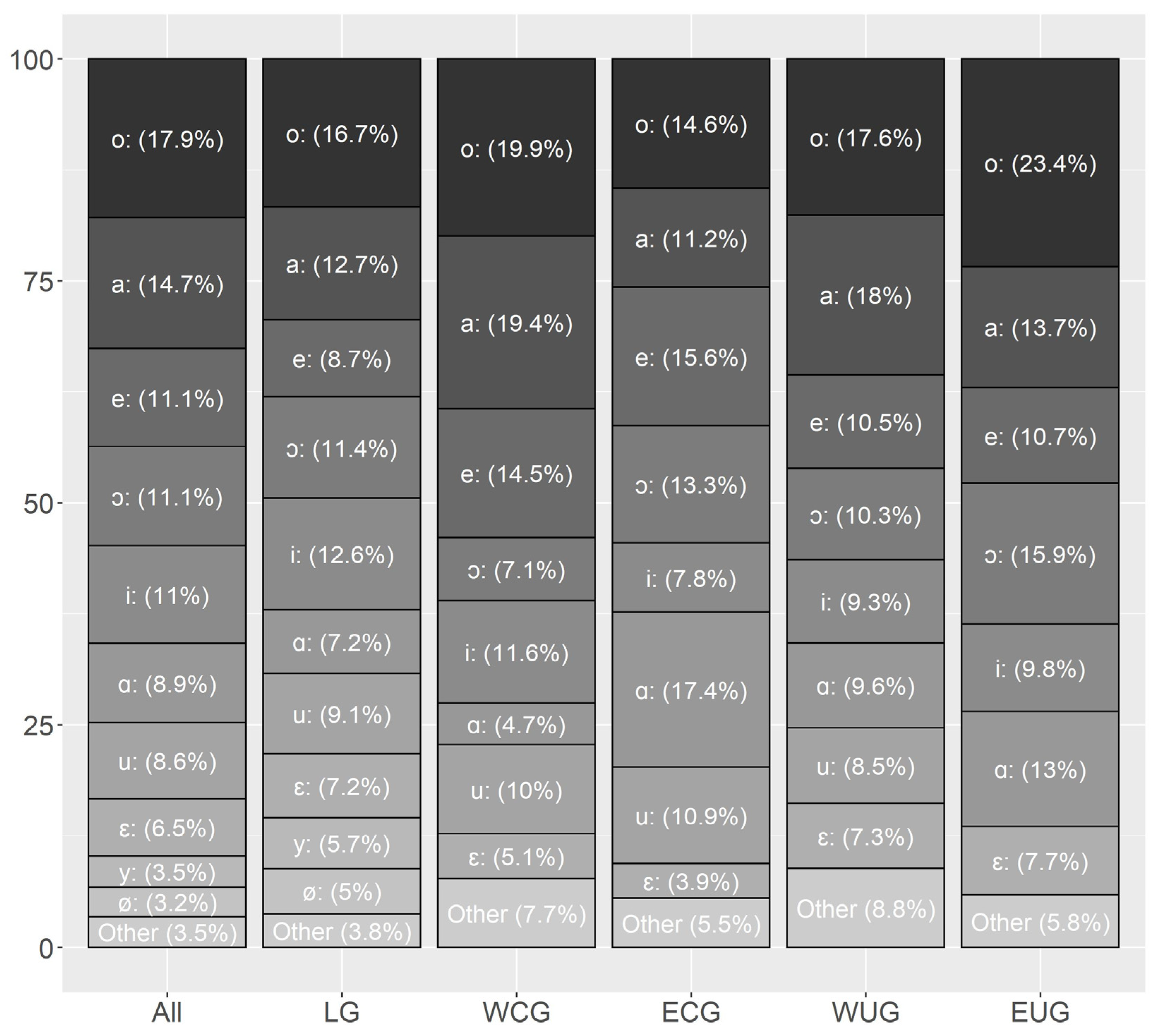

A second question, which is the main focus of this study, is which actual vowels are represented by the three groups V, Vː and VV? Standard German is classified as a language with a large vowel system (

Maddieson 2013). From its 15 vowels, there are 6 tense ones, which can be short [i y e ø u o] or long [iː yː eː øː uː oː], and 9 short lax ones [ɪ ɛ ʏ œ ʊ ɔ a ə ɐ] from which 2 can be lengthened [ɛː aː] (

Hall 2000, p. 34). Furthermore, there are the three diphthongs [aɪ aʊ ɔɪ]. The Standard German vowel inventory is also shared by the dialects. However, they introduce a couple of particularities: [ɑ] or [ɒ] are found in many areas including Hessian (

Durrell and Davies 1990, p. 225), Thuringian (

Spangenberg 1990, pp. 269, 274, 277), High Alemannic (

Russ 1990a, p. 369) and Southern Bavarian (

Wiesinger 1990, p. 485). Furthermore, there are nasal vowels in Swabian (

Russ 1990b, p. 347) and tone accents in Central Franconian (

Schmidt 1986). A detailed overview of the vowel inventories of the German dialects is given in

Wiesinger (

1983b) and further descriptions can be found in the two edited volumes by

Herrgen and Schmidt (

2019) and

Russ (

1990c). But so far, there are no studies providing any information on German dialectal vowel frequencies. In contrast, there are a couple of studies discussing them for Standard German: a very early approach is

Trubetskoy’s (

1967, p. 233), who calculated the vowel percentages of 200 words from a scientific text (K. Bühler) and from a fairytale (A. Dirr) which are given in

Table 1. Due to these rather similar percentages, he concludes that German phoneme frequency is not influenced by stylistics.

Menzerath (

1954, p. 72f) provides frequency counts for monosyllabic words that constitute the following order (from highest to lowest count). [ʌ] does not belong to the Standard German vowel inventory and might originate from a loanword in his data. The diphthong /ui/ is restricted to cases such as interjections (

Pfui!) or names (

Luise).

Short Vowels: a (385), i (252), u (214), ä (197), o (191), ü (15), ö (15), æ (3), ʌ (1);

Long Vowels: aː (164), oː (108), iː (107), eː (93), uː (92), äː (31), üː (19), öː (26);

Diphthongs: ei (163), au (110), eu (31), ui (2).

Delattre (

1964, p. 89) gives combined percentages for mono- and polysyllabic words, but does not further distinguish between long and short vowels:

ə (23.88%), ɪ (11.52%), a (10.72%), aɪ (7.88%), ɛ (7.08%), e (6.73%), i (5.88%),

ʊ (5.28%), ɑ (3.89%), u (3.84%), ɔ (3.74%), aʊ (3.14%), o (2.29%), y (1.30%),

ʏ (0.98%), ø (0.95%), ɔʏ (0.55%), œ (0.35%).

Pätzold and Simpson (

1997, p. 223) present relative vowel frequency counts from the Kiel Corpus resulting in the order given below (the original data are given as a bar plot; thus, the percentages had to be extracted from the y-axis):

ə (15,6%), ɪ (11.7%), a (9%), iː (8%), aɪ (7.8%), ɛ (7%), ɐ (7%), eː (6.7%), aː (5.3%),

ʊ (5%), uː (3.3)%, ɔ (3%), aʊ (2.9%), oː (2.8%), yː (1.3%), ɔʏ (1.1%), ʏ (1%), øː (1%),

œ (0.5%).

Since these four works rely on different data and analyze them in varying granularity, it is not surprising that their results for short and long vowels do not agree in every aspect.

Pätzold and Simpson (

1997, p. 222) further point out that vowel frequencies tend to be a speaker-dependent phenomenon. Nevertheless, all four works reveal a general tendency that can be summarized as the following: [ə] is the most frequent vowel in German, followed by the group of unrounded non-back vowels [a, ɪ, i, ɛ, e] with [ɪ] as the most frequent one, followed by the back vowels [u, ʊ, o, ɔ] and the rounded front vowels [y, ʏ, ø, œ] as the rarest group. However, this pattern contradicts the hypothesis of

Menzerath (

1954, p. 72f) that the most frequent vowels are those found in the extreme points of the vowel space. In contrast to the monophthongs, the results for the diphthongs are consistent: all four sources found them to be ordered as [aɪ, aʊ, ɔʏ].

In

Section 3.2, this work presents a comparative analysis of vowel frequency in the five German dialect areas. Coming back to the initial question of what stands behind the three groups V, Vː and VV,

Section 3.3 features an analysis of consonant clustering similar to

Lameli and Link (

forthcoming) but separately for all vowels and diphthongs. Based on the results from

Section 3.2 and

Section 3.3, two questions are considered:

- 2

Are some vowels more inclined to have consonant clusters than others?

- 3

Do more frequent vowels also have a higher probability for clustering?

Another aspect from

Lameli and Link (

forthcoming) is the important role of sound change processes from both Middle High German (MHG) and Middle Low German (MLG) to the modern German dialects. MHG is the historic stage of German, which was spoken in a couple of varieties in the Central and Upper German area around 1050 to 1350 (

Paul 2007, p. 10). MHG is thus a diachronic reference point for the vowel systems of the modern dialects of this area (

Wiesinger 1983b, p. 1044). The Low German dialects correspond to MLG (

Wiesinger 1983b, p. 1045), which is dated from the start of the 13th century to the 16th century (

Lasch 1974, pp. 3, 5). Like modern German, MHG and MLG have short and long monophthongs and diphthongs, but due to a couple of sound change processes, there are some major differences: as an example, there is the New High German (NHG) Diphthongization, which caused MHD <î>, <iu> and <û> to become [aɪ], [ɔʏ] and [aʊ].

In order to approach the question below,

Section 3.4 presents another analysis of consonant clustering probability based on splitting the data according to the underlying MHG/MLG vowels.

- 4

Can differences in clustering be traced back to MHG/MLG vowels?

Furthermore,

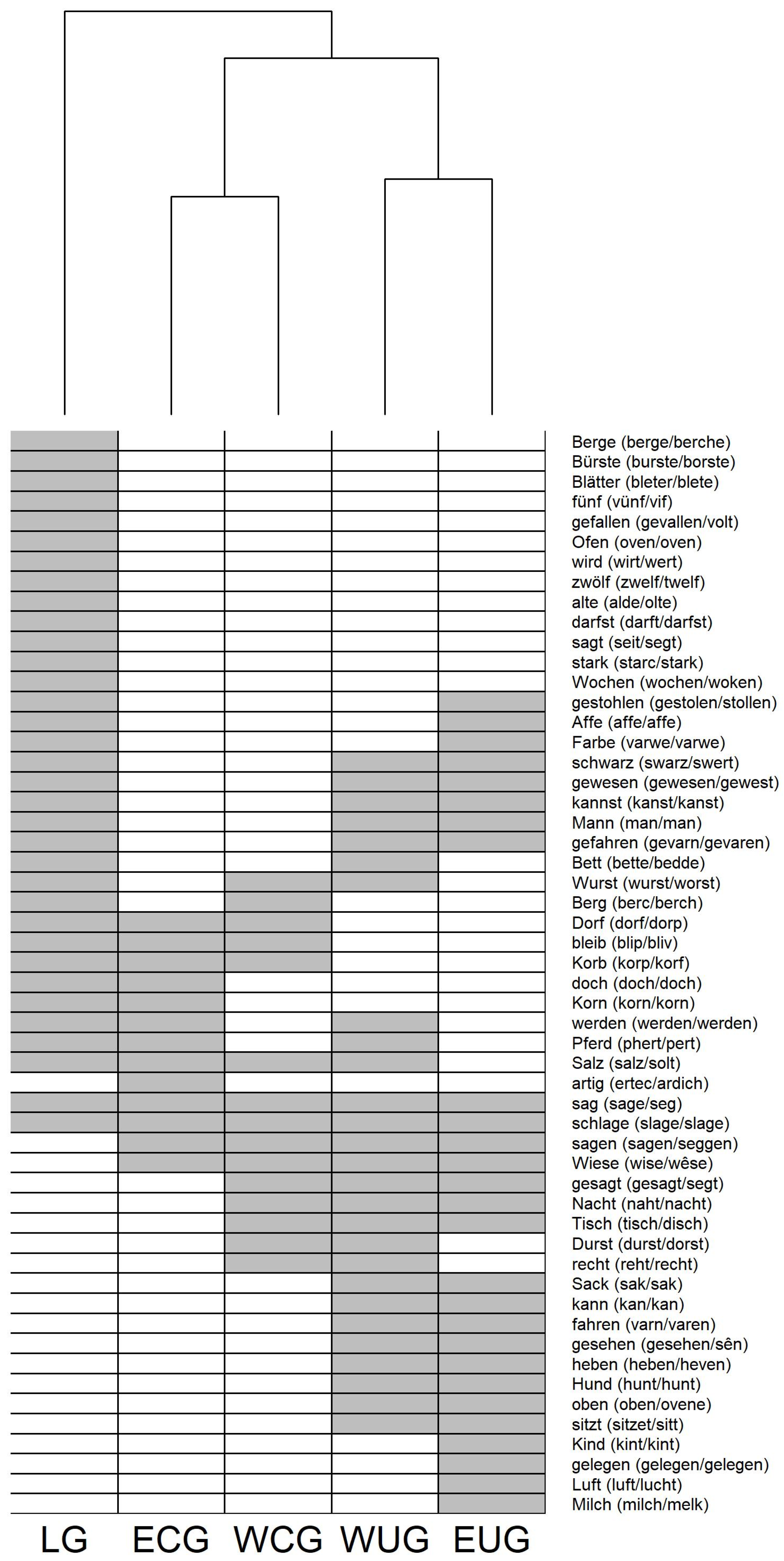

Section 3.4 also considers the role of the (CV) syllable structure and takes a look at the actual MHG/MLG words in terms of an analysis of hierarchical clustering.

2. Materials and Methods

The PhonD2-Corpus is an open access online database on phonotactic and morphological structure of the dialects in the Federal Republic of Germany (see

Lameli et al. 2023). The corpus features translations of Wenker sentences

2 into dialect by 172 subjects from 172 sites all across Germany (approx. 80,000 words and approx. 300,000 sounds).

The audio data used for the corpus have been taken from the project

Phonetischer Atlas der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (PAD) (

Göschel 1992,

2000). The PhonD2-Corpus contains broad phonetic IPA and SAMPA transcriptions, which had the aim of documenting features that are phonologically contrastive on the dialectal level

3. The transcribed words are syllabified based on the Sonority Sequencing Principle (

Selkirk 1984, p. 116) and the Maximum Onset Principle (

Hall 2000, p. 217). Since the syllabification also considers syllabic consonants (liquids and nasals; see

Hall 2000, p. 216), consonant sequences caused by the loss of schwa such as [bn] in [haːbn] ‘to have’ are treated as syllables (with [b] as onset and [n] as nucleus). The corpus provides further phonotactic information such as the CV structure, syllable scheme, sonority measures, syllable count, syllable weight and syllable type and also gives some morphological data. It is available under

https://dsa.info/PhonD2/ (last accessed on 17 July 2024), where the data for each lemma can be downloaded as a CSV or EXCEL file.

In recent phonotactic research, it is common to classify consonant clusters into two groups (see

Dressler and Dziubalska-Kolaczyk 2006): There are morphonotactic clusters, as in vaːʃt (warst), ‘you were’, which result from the affixation of consonantal suffixes -

s, -

t, -

st or the

g-prefix in the Upper German area due to the schwa syncope of the past participle marker

ge- like in

ghapt (gehabt), ‘have’, (see

Rowley 1997, p. 76). Clusters within a word consisting of a single morpheme such as vuɐʃt (Wurst), ’sausage’, are referred to as phonotactic. In

Lameli and Link (

forthcoming), it was revealed that morphologically complex monosyllabic lexemes have a higher clustering probability than those consisting of a single morpheme, which is in line with

Dressler and Kononenko (

2021, p. 43). Since this was the case in all five dialect areas and for all three vowel types alike, the morphonotactic vs. phonotactic distinction was not further considered for the spatial analyses of

Lameli and Link (

forthcoming; this result is given in

Appendix A in

Figure A1).

This study is based on the same data as

Lameli and Link (

forthcoming): monosyllabic lexemes from the Wenker sentences of the PhonD2-Corpus. But to ensure consistency, its focus is set on purely phonotactic clusters and thus only monosyllabic lexemes without morpheme boundaries (85.29% of the original data) are considered for analysis. Nevertheless, all analyses were also made using the original data and these results are given in

Appendix A for comparison.

As in

Lameli and Link (

forthcoming), the data were split into the five large dialect areas according to

Wiesinger (

1983a): Low German (LG), West Central German (WCG), East Central German (ECG), West Upper German (WUG) and East Upper German (EUG)

4. Below, some frequency counts of the analyzed data are given:

4. Discussion

- 1

- 2

Are some vowels more inclined to have consonant clusters than others?

- 3

Do more frequent vowels also have a higher probability for clustering?

- 4

Can differences in clustering be traced back to MHG/MLG vowels?

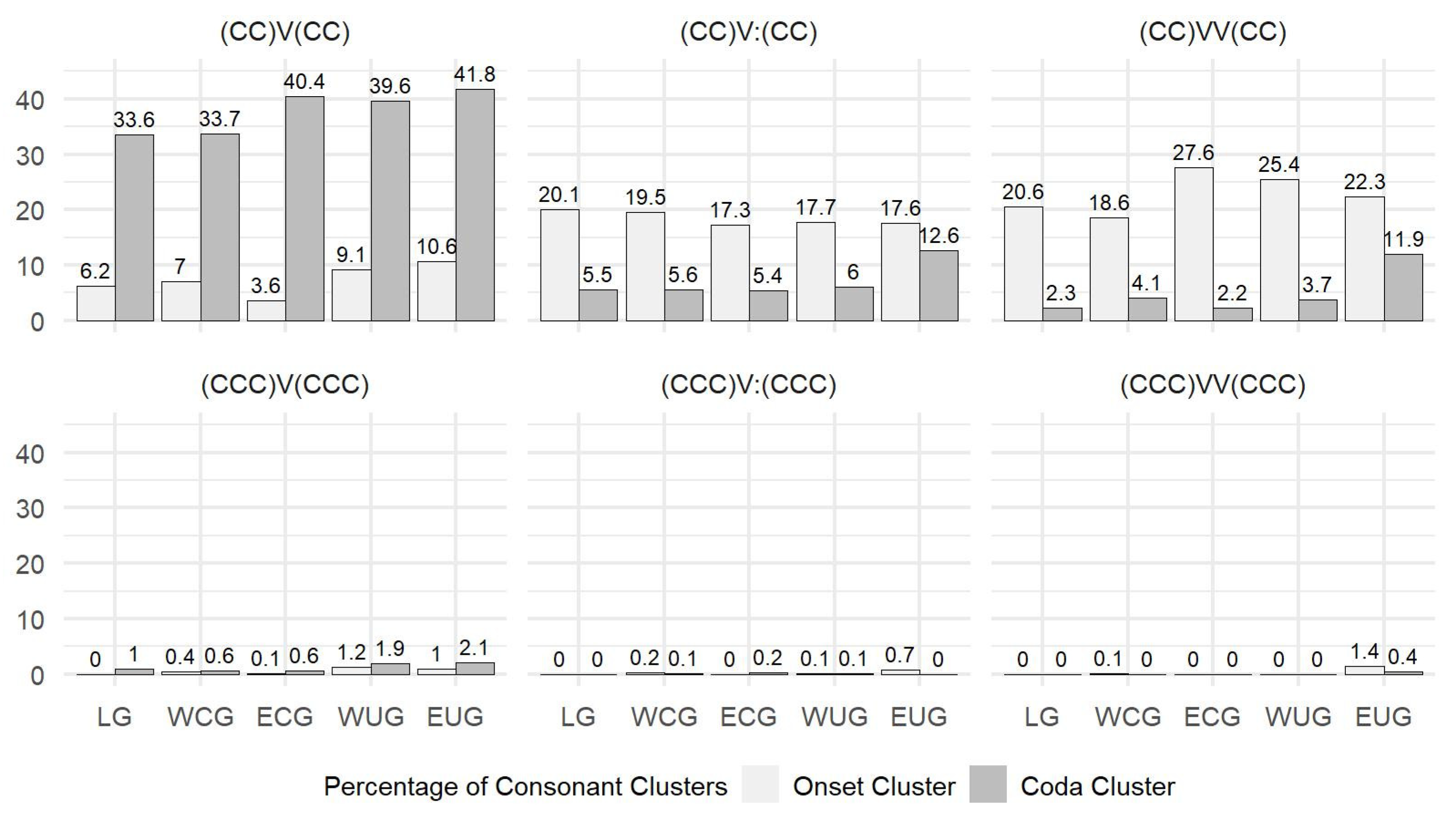

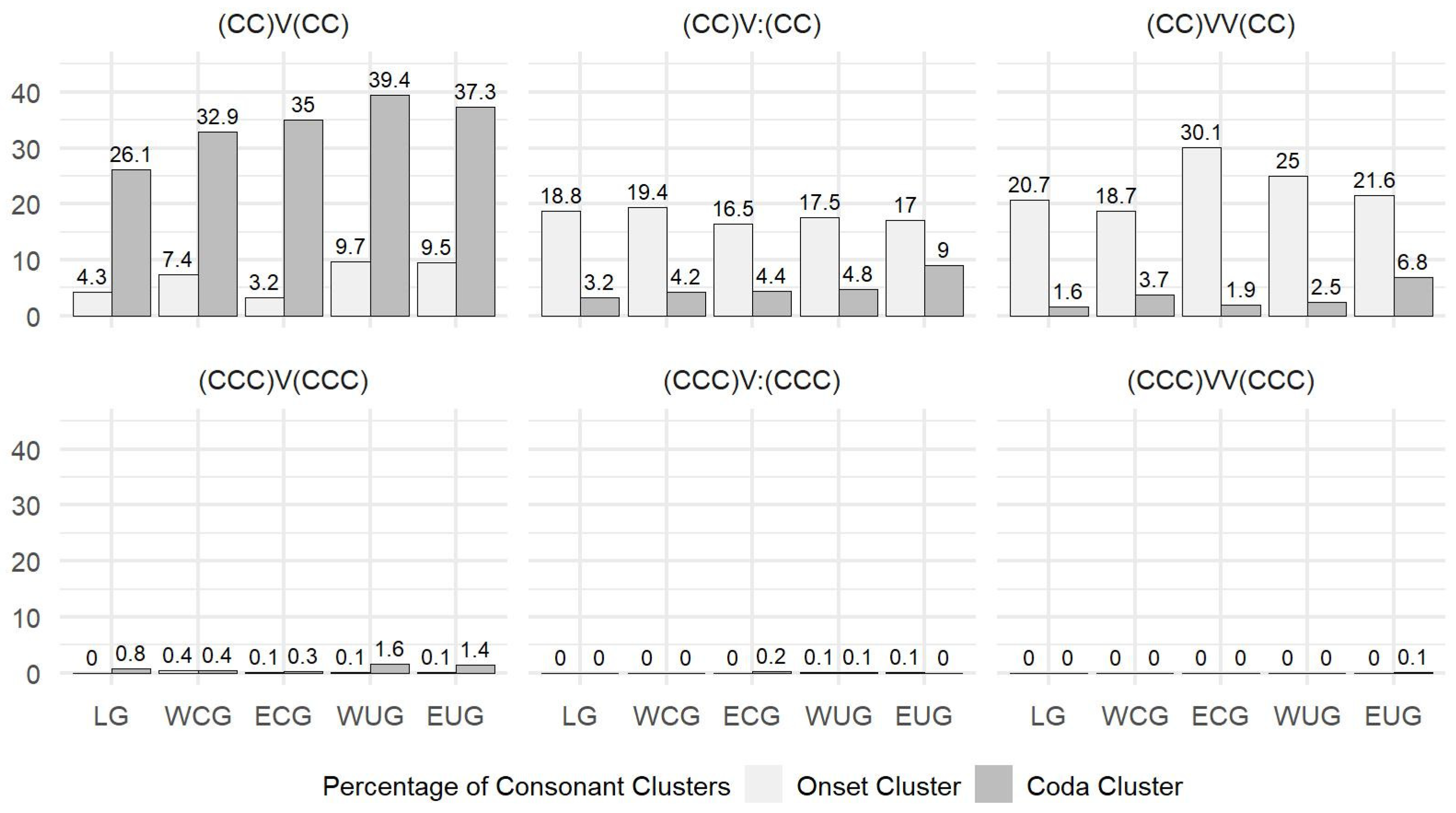

Question 1 was answered in 3.1 where it was found that the spatial North–South increase as well as the preferences of the three vowel groups (V, Vː, VV) are dominated by syllable types with biconsonantal clusters in the onset and/or coda. However, this is not surprising in terms of markedness: clusters with three or more clusters are more marked than biconsonantal ones in the onset (

Silbenanlautgesetz;

Hall 2000, p. 213) as well as in the coda (

Silbenauslautgesetz;

Hall 2000, p. 214).

It is of great interest to go deeper into the consonant clusters below the level of the CV structure. Such an analysis is given in

Harnisch (

1987, pp. 255–59), who examined the relation between vowel quantity and particular consonant clusters for the dialect of Ludwigsstadt (Thuringian–East Franconian transition area). However, performing this for the data studied in this work would have extended the scope of a single paper. Thus, this is going to be performed in a second work that is currently under preparation.

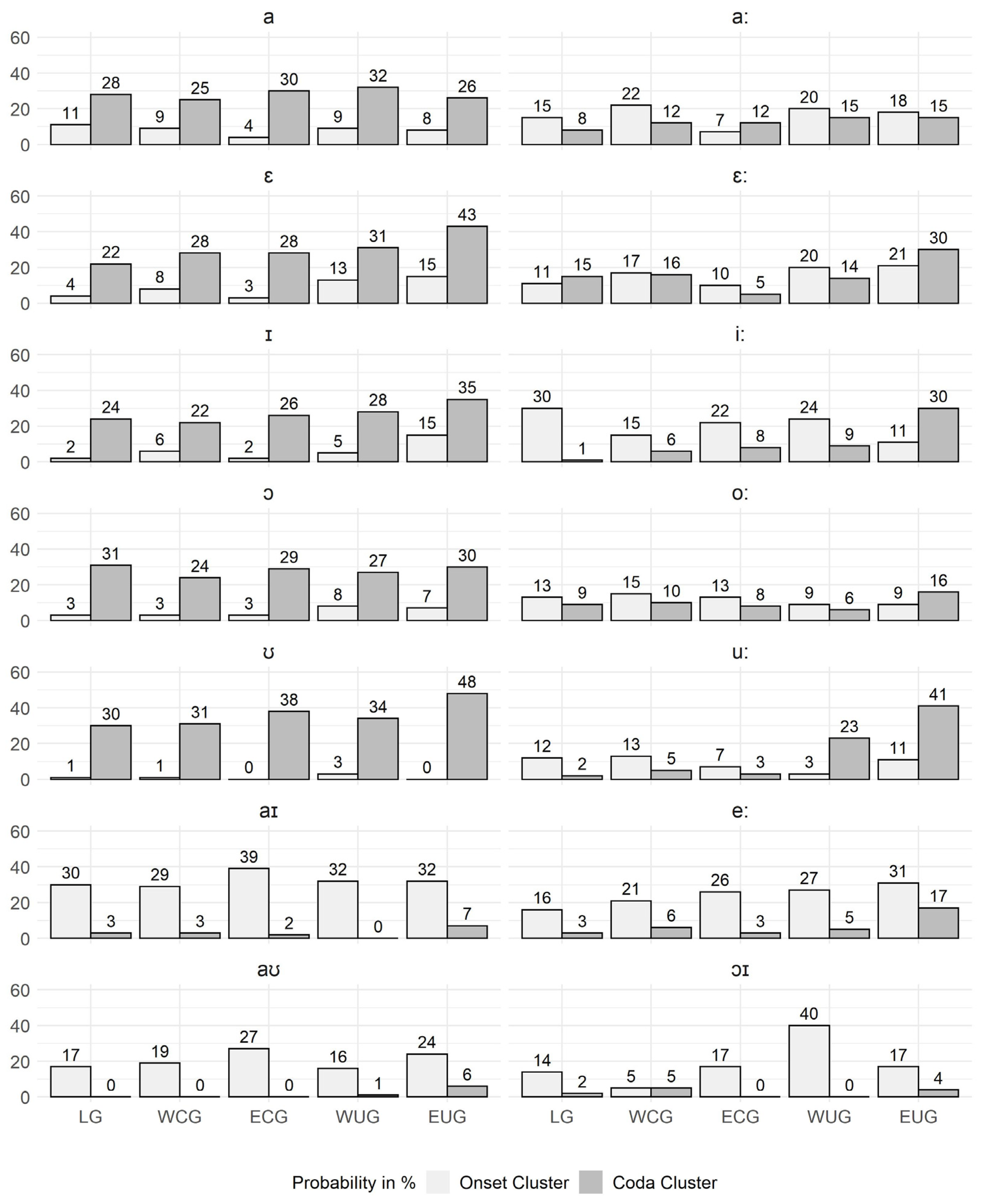

Considering Question 2, the findings of

Section 3.3 could confirm that particular vowels do have clustering preferences of their own. Nevertheless, these preferences are ruled by the characteristic pattern of the vowel group (V, Vː, VV) described by

Lameli and Link (

forthcoming): monosyllabic lexemes with a short vowel in the nucleus prefer coda clustering while those with a diphthong prefer onset clusters and those with a long vowel have a balanced pattern.

Question 3 was tested by calculating the correlation between the clustering probabilities found in

Section 3.3 and the vowel percentages from

Section 3.2. The monophthongs (V, Vː) had no positive correlations so that a frequency effect can be ruled out for them. In contrast, the diphthongs were found to be positively correlated with frequency.

For Standard German,

Beedham (

1995, p. 146) describes a tendency for particular consonant + vowel and vowel + consonant sequences to be predictors of whether a verb has strong or weak inflection. It would be highly interesting to test the five dialect areas for this tendency as well but in order to gain valuable insights, a much broader database would be necessary:

Beedham (

1995) is based on 169 strong and 1467 weak verbs whereas the Wenker sentences from the PhonD2-Corpus have a type count of 139 verbs (for the full corpus), from which 73 are strong and 66 are weak.

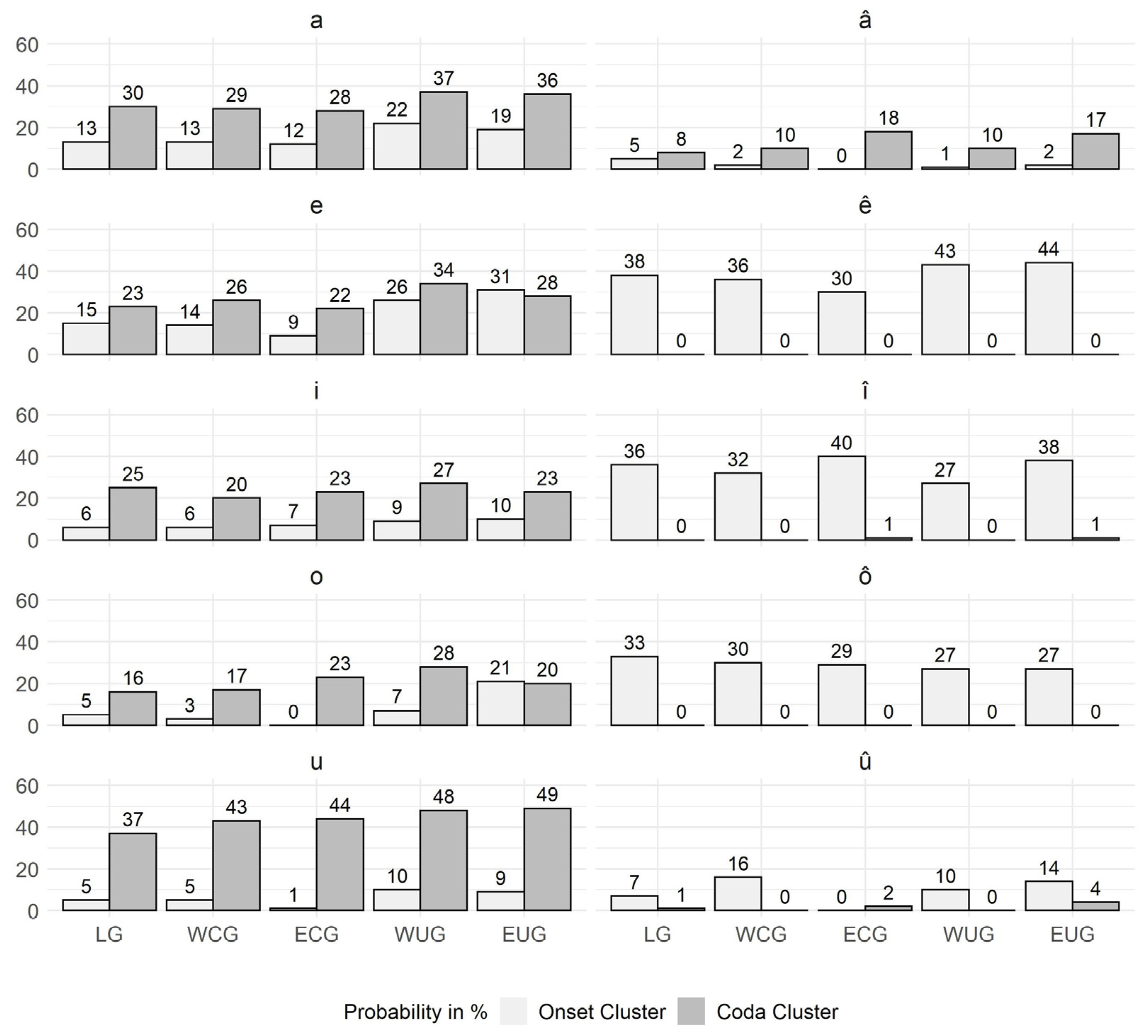

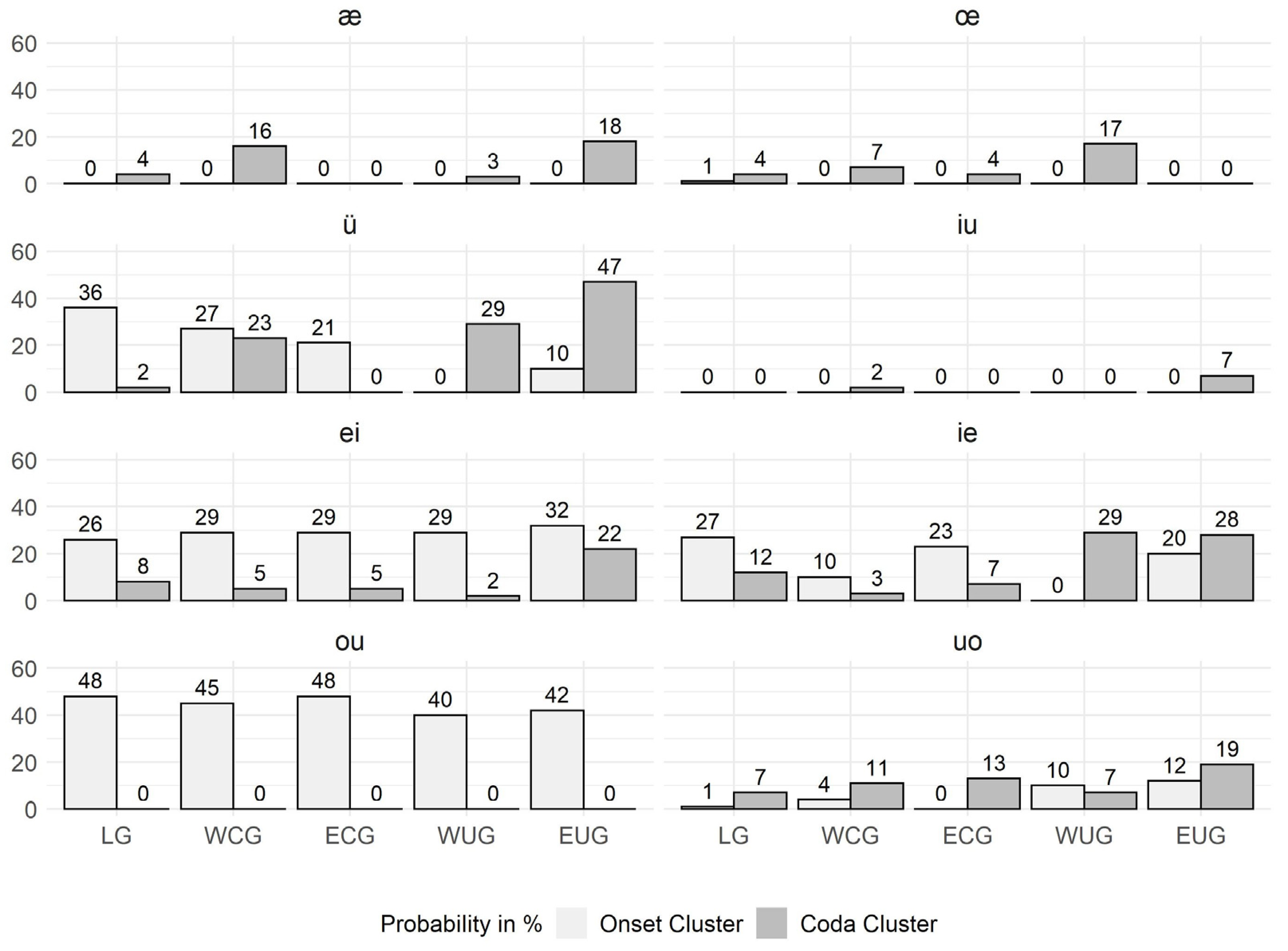

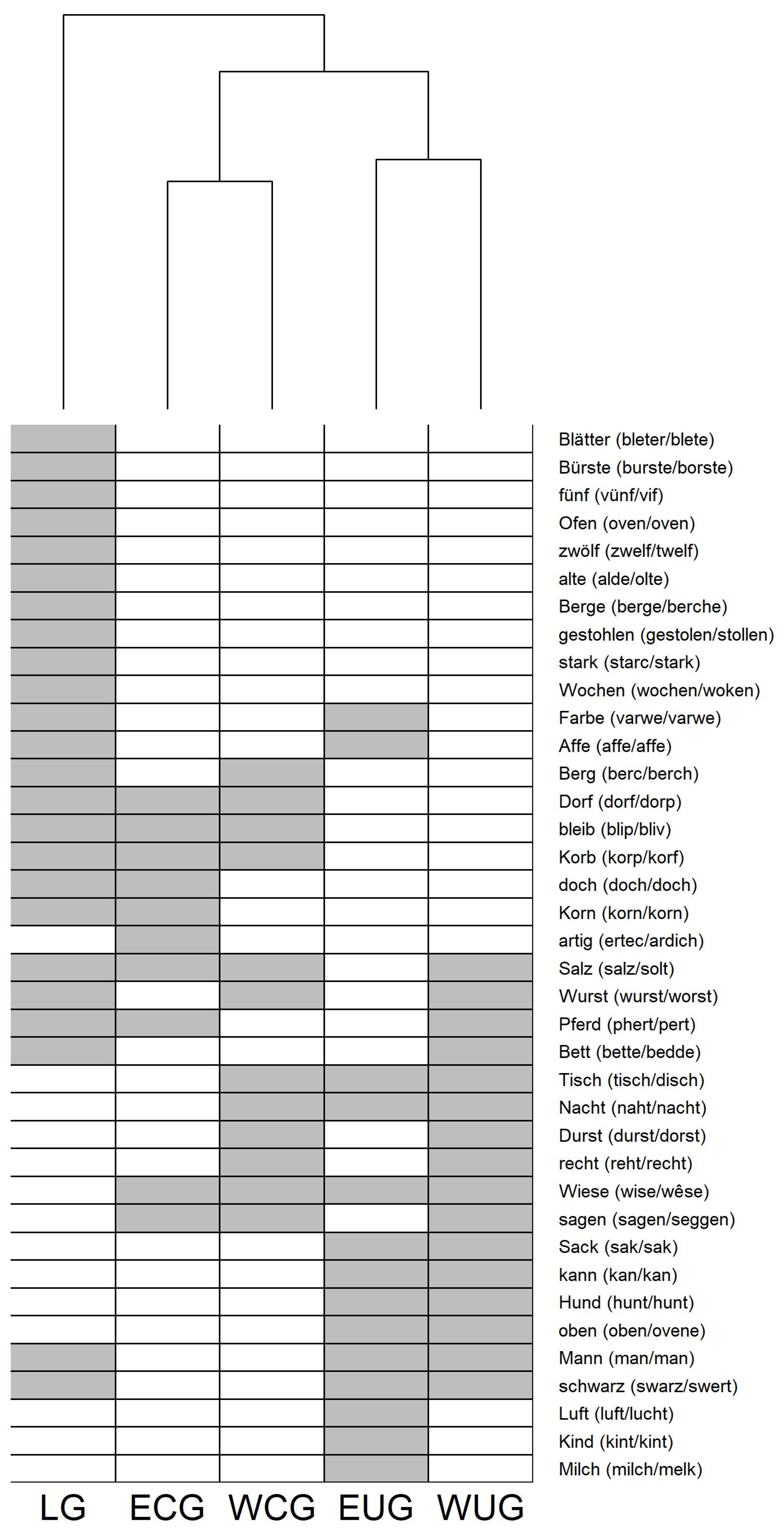

For answering Question 4, the data were grouped according to the underlying MHG (and MLG) vowels in

Section 3.4. The analyses of the clustering probability in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 reveal an interesting phenomenon: instead of the previously described threefold pattern, a twofold pattern of consonant clustering preference becomes visible. Words with an MHG (and MLG) long vowel have the same strong onset preference as the modern diphthongs. This raised the question of how the balanced clustering preference of the modern long vowel did emerge. The analysis of the CV structure in

Section 3.4.3 illustrated that there are only a small number of CCV:CC syllables, but a high number of CV:CC and CCV:C, which lead to the assumption that there must have been a transition from MHG (and MLG) short vowels to modern long vowels. In

Section 3.4.4, three historical sound change processes that have caused such a transition were identified and validated with a large number of examples from the PhonD2 Corpus.

In

Lameli and Link (

forthcoming), the strong coda cluster preference of monosyllabic words with a short vowel was explained with regard to the compensation of the syllable weight (

Auer 1991, p. 8), which was not necessary for long vowels and diphthongs counting as heavy due to being bimoraic. This compensation of the syllable weight actually corresponds more closely to the twofold pattern of the clustering preference found when analyzing the data based on the underlying MHG/MLG vowels in

Section 3.4.

Ryan (

2016, p. 721) notes that most languages with a weight-sensitive stress system have a binary distinction but more fine-grained distinctions are also found (p. 728). A possible explanation for the threefold clustering pattern of the modern dialects, namely the tendency for long vowels towards balanced probabilities, could be in terms of the Weight-by-Position parameter indicating whether the coda is treated as moraic or not in a language (

Hayes 1989, p. 258). In the context of Monosyllabic Lengthening before consonant clusters (

Schwerschlussdehnung),

Seiler and Würth (

2014, p. 151) suggest that Thuringian does not have Weight-by-Position and consonant clusters are not considered for calculating the syllable weight. Furthermore, long monophthongs can also be considered as lighter than diphthongs:

Ryan (

2016, p. 730) notes that vowels with a longer duration correlate with a greater syllable weight and according to

Delattre (

1964 p. 91), diphthongs have averagely longer durations than the long and short monophthongs.

In addition to the compensation of the syllable weight,

Lameli and Link (

forthcoming) also assumed that the preference for coda clustering is helpful for marking word boundaries in monosyllabic words, which supports speech perception (

Caro Reina 2019, p. 267). With regard to the MHG/MLG twofold vs. the modern threefold pattern, there is probably a tendency towards the strengthening of the phonological word in monosyllabic lexemes, which becomes interesting in the context of the syllable vs. word language typology framework.

Szczepaniak (

2007) suggests that German was once a language that put a strong emphasis on the syllable (Old High German as a syllable language), which changed to a focus on the phonological word (New High German as a word language). The stage where this process was consolidated is Early New High German, which corresponds to the twofold clustering preference of MHG/MLG becoming threefold in the five dialect areas (

Szczepaniak 2007, p. 331). Furthermore,

Szczepaniak (

2007, p. 329) emphasizes that such a change from syllable to word language goes in hand with optimizing the structure of the phonological word by either word final consonant epenthesis (which leads to consonant clustering) or by word-related restrictions on phoneme distribution.

But since the analyses of this work are focused on monosyllabic lexemes, it is not known whether the boundary strengthening observed for them also takes place in polysyllabic words. Thus, future work does not only have to consider the consonant clusters themselves (which is going to be the case in a second paper) but also explore polysyllabic words under these aspects.