Abstract

This study examines attitudes and ideologies associated with the Finnish language and identity among successive generations of Finnish Americans in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and Northern Minnesota, where Finnish is a postvernacular heritage language (HL). Employing ethnographic approaches including participant observation, narrative interviews, and the study of material analyzed using thematic analysis, I describe prevailing ideologies shaping perceptions of Finnishness. My findings highlight a pronounced pride and attachment to Finnish identity, which discursively and ideologically shape a sense of belonging and serve as a foundation for Finnish American identity formation. However, tensions emerge, particularly regarding the perceived pronunciation of Finnish words such as “sauna” and Finnish last names, indicating ideologies related to authenticity and purity. The evolution of terms like “Finlander” suggests generational change and reflects a history of friction with individuals not identifying as Finnish within the studied postvernacular speech communities.

1. Introduction

Attitudes and ideologies, much like language and identity, are ever-evolving. Current multigenerational Finnish Americans engage with their Finnish heritage differently than their predecessors. Unlike earlier generations, who were immersed in the Finnish language through church services, newspapers such as Työmies, and, more recently in history, the local Finnish American TV show, Suomi Kutsuu, today’s generations navigate their identity against a backdrop of shifting linguistic and cultural landscapes. As the active use of the Finnish language recedes into the past, cultural lexical items and phrases become the extent to which Finnish is used in daily life, with the ability to pronounce these terms according to what Finnish Americans perceive as correct being indicative of an authentic Finnish identity.

Understanding these attitudes (Garrett 2010) and ideologies (Silverstein 1979; Peterson 2019; Cavanaugh 2020; Woolard 2020; Johnstone 2010) toward language, specifically Finnishness, requires examining how members of the heritage language (HL) community express their complex mix of beliefs, perceptions, and emotions regarding the Finnish language and identity. While recent HL research has concentrated on the influence of attitudes and ideologies on language acquisition and language maintenance, examining Finnish as an HL in the United States requires a nuanced approach due to the postvernacularity (Shandler 2005) of the Finnish language. That is, Finnish in Michigan and Minnesota is postvernacular because it is no longer actively spoken as the primary means of communication in daily life, yet applications of Finnish still hold cultural and symbolic significance as HL community members continue to shape their identity and foster a sense of belonging through Finnishness (Remlinger and Karinen, forthcoming). Finnish, with its largest wave of migration to the U.S. occurring in the early 1900s, faces a different reality as an HL than, for instance, Spanish, due to a smaller, less continuously replenished speaker community. In contrast to Finnish, Spanish as an HL benefits from a consistent influx of new immigrants and a large speaker base, favorably contributing to language maintenance and transmission. In this article, the term “Finnishness” refers to that which encompasses the Finnish American identity, including semiotic manifestations associated with language, culture, and heritage.

This study builds on existing research that has explored various aspects of Finnish American language use in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, including the linguistic landscape (Remlinger and Karinen, forthcoming), linguistic performativity of Finnishness (Remlinger 2016), and how Finnish has impacted and interacts with the variety of English known as the Yooper1 dialect in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (Rankinen 2014; Remlinger 2017; Rankinen and Ma 2020). This study also benefits from Johnson’s (2018) study on Finnish language shift in Oulu, Wisconsin, a rural HL community located about 35 miles from Duluth, Minnesota. The present work distinguishes itself by being the first study, to my knowledge, to focus specifically on attitudes and ideologies of Finnish as an HL and expands on the scope of previous work by including Northern Minnesota as a fieldwork site.

The current study is particularly timely given the heightened uncertainty surrounding the future of Finnish American heritage and culture due to the gradual decline of cultural clubs and fluent speakers. The sudden closure of Finlandia University2 in May 2023 has exacerbated this uncertainty, prompting concerns about the fate of key institutions vital for preserving Finnish and Finnish American culture. The university housed culturally significant entities, including the Finnish American Heritage Center, Folk Art School, and the widely circulated Finnish American newspaper, The Finnish American Reporter. Given these circumstances, this study is motivated by the necessity to comprehend and describe the shifts Finnish American identity and heritage amidst these obstacles.

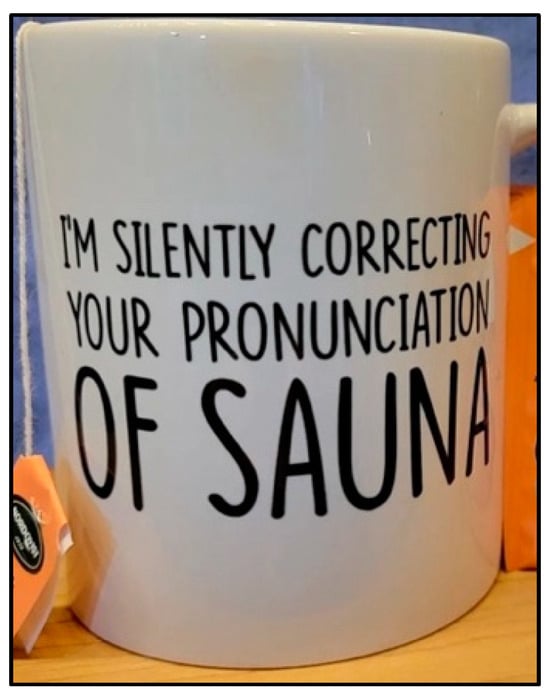

My analysis draws on material gathered through ethnographic approaches, including participant observation conducted in May 2022 and July 2023, narrative interviews with 36 individuals, and collected photos of material ethnography. An analysis of the data reveals overwhelmingly positive attitudes and pride associated with the Finnish language and Finnishness. These sentiments are met by ideologies of authenticity and purity alongside subtle generational differences. Generational changes are evident in the way language is perceived, as seen in the evolution of terms like “Finlander”, which had strongly negative connotations for older generations but is now used neutrally or with pride by younger generations. Purist corrections are also evident, as demonstrated by the popularized expression, “I’m silently correcting your pronunciation of sauna” found commodified on mugs and t-shirts. These findings illustrate a growing flexibility in some instances and evolving cultural and linguistic perceptions in others.

This descriptive study aims to provide an overview of the language attitudes and ideologies present among members of Finnish American heritage communities across successive generations. It is important to note that the principal aim of this study is not to generate representative, quantitative conclusions but rather to focus on the need to better understand Finnish American identity and heritage, which enables comparisons to other heritage language contexts. Thus, the research questions guiding this study are as follows:

- (1)

- How do attitudes and ideologies toward Finnishness manifest in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and Northern Minnesota?

- (2)

- What discernible generational differences, if any, characterize attitudes and ideologies toward Finnishness among Finnish Americans?

2. Background

2.1. Language Attitudes and Ideologies

Language attitudes and language ideologies, integral components of sociolinguistic inquiry, originate from diverse academic disciplines (Garrett 2010, p. 24): language ideologies from linguistic anthropology through the works of Hymes (1977) and Blom and Gumperz (1972) and language attitudes from social psychology developed and applied through studies of language awareness (Preston 1996) and perceptual dialectology (Preston 1989). According to Kroskrity, the difference is also visible in methodological approaches, with research on language attitudes often aiming for quantitative assumptions, while studies on language ideologies tend to adopt qualitative methods (Kroskrity 2016). While clarifying the distinction between these theoretical terms—attitudes and ideologies—is essential (King 2000), it is equally important to recognize that there is a significant overlap between them. Both concepts play a role in shaping how individuals perceive and interact with language in social settings, influencing their linguistic behaviors, preferences, and judgments. The following paragraphs aim to contextualize these concepts within the context of this work.

Peterson’s work on attitudes and ideologies behind varieties of English provides definitions for understanding language attitudes. According to Peterson (2019, p. 8), language attitudes are “beliefs or judgments people have about certain social styles of language, features of a language, or varieties of a language”. To illustrate this concept, consider an example observed during an informal conversation on a research trip in 2022 that prompted the present study. While discussing local ways of speaking in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, someone remarked that their partner “had to get rid of his Yooper3 accent, he sounded Finnish and uneducated”. This remark vividly demonstrates the tendency to make judgments or hold beliefs about the variety of English in the Upper Peninsula influenced by Finnish, associating this specific accent with social attributes pertaining to social class and education level. Garrett (2010, p. 23) explains that although controversial, attitudes can be understood through three components: (1) cognition, (2) affect, and (3) behavior. In the example above, this would correspond as such:

- (1)

- The belief that this variety of English influenced by Finnish is uneducated.

- (2)

- Feelings of discomfort or disdain toward this variety of English.

- (3)

- Actively ensuring that one’s partner does not let this Finnish influence slip into their English.

While language attitudes center on individuals’ beliefs and judgments about language varieties, language ideologies offer a broader perspective by examining societal assumptions or patterns surrounding language use. Peterson (Kühl and Peterson 2018, p. 7) explains that language ideologies are “preconceived notions, beliefs, and/or emotions that people hold about certain social styles, varieties, or features of a language”. A prime example of a language ideology of Finnish as an HL context is illustrated by the belief that authentic Finns pronounce sauna “correctly” (see Remlinger 2018), reflecting the notion or purist ideology that there exists a single “correct” way to pronounce the word. These ideologies are prevalent within the Finnish heritage communities under study and often extend to those who do not identify as Finnish American. In other words, these ideologies can and often do extend to individuals, irrespective of their claimed identity.

Despite their distinct disciplinary origins, both the study of language attitudes and the study of language ideologies share a common goal: to uncover people’s beliefs and sentiments about language, whether at an individual or collective level. The relationship between language attitudes and ideologies is dynamic and exhibits overlap. While language attitudes can contribute to the formation of language ideologies through individual and collective experiences, language ideologies also play a role in shaping and reinforcing language attitudes within a society. As King puts it, “while a language attitude is usually conceived of as a specific response to certain aspects of a particular language, language ideology is an integrated system of beliefs concerning a language, or possibly language in general” (King 2000, p. 7).

2.2. Situating “The Center of Finnish America”

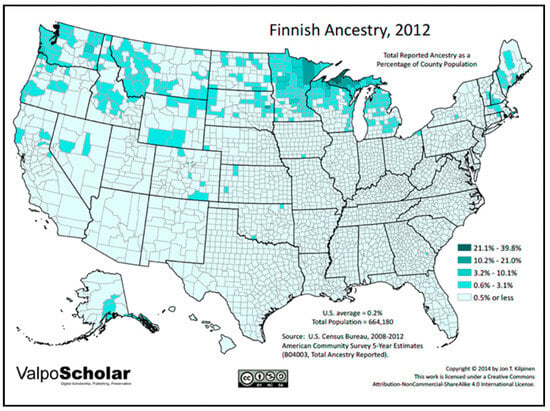

Michigan and Minnesota are the states home to the highest percentage of the population claiming Finnish ancestry in the United States (see Figure 1), boasting numerous areas historically populated by Finnish migrants, leading Lockwood and Lockwood (2017) to designate this region as the “center of Finnish America” (pp. 115–16). Given this significance, Duluth in Minnesota and Hancock in Michigan were the focal points for this study due to their status as hubs for Finnish and Finnish American heritage and cultural activity. Interviewees and observations were also carried out in the surrounding areas, including in towns spread out across the Western Upper Peninsula and towns spread across Upper Minnesota.

Figure 1.

Map of Finnish ancestry in the United States. Source: Jon T. Kilpinen (2014).

Before diving into these geographical areas, it is necessary to give a brief history of Finnish immigration to North America. During the years spanning from 1870 to 1929, an estimated 350,000 Finns made their way to North America, with an estimated 300,000 choosing the United States as their destination (Björklund 2005, p. 8; United States Bureau of the Census 1920). Most of these emigrants came from the historical Pohjanmaa “Ostrobothnia” province. Nowadays, this corresponds to Ostrobothnia, Northern Ostrobothnia, Central Ostrobothnia, Southern Ostrobothnia, Kainuu, and southern parts of Lapland. Kero notes that the geographical location of Ostrobothnia influenced emigration due to its proximity and connections to other countries (Kero 1996, pp. 61–62). Drawing from passenger lists and archival records of parishes, Kero identifies several regions with significant emigrant populations during that period, including the Tornio River Valley, Kalajoki, Kokkola, Vaasa, and Kristiinankaupunki (Kero 1982, p. 21).

Even today, many Finnish Americans speculate about why their ancestors chose these regions, often attributing it to the resemblance of the landscape to their native Finland. However, these resemblances are largely coincidental. The primary reason for their settlement in these areas was the availability of jobs working in copper and iron mines and in the forest as loggers, among other jobs (Kaunonen 2009, p. 7). These Finns tended to move to what is known as the Iron Range in Northern Minnesota and the Copper Country in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. This article also acknowledges the complex role of Finns in settler colonialism. In their book, Lahti and Andersson (2022) offer a fresh perspective, portraying the Finnish presence in North America not merely as that of immigrants but that of settlers actively involved in settler colonial processes. They assert that “Finns were actively involved in the settler colonial processes, and they played a role in the exploitation of nature and replacement of Indigenous peoples”, whether knowingly or unknowingly (Lahti and Andersson 2022, p. 2).

2.3. Areal Focus: Hancock in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan

Hancock, Michigan, is home to the Finnish American Heritage Center and Finnish American Folk Art School, serving as focal points for Finnish cultural preservation. Until May 2023, Hancock was also home to Finlandia University, previously known as Suomi College. According to the university’s website, Finlandia was recognized as the sole surviving university established by Finnish immigrants still operational in North America. Not only did the community face the closure of the university, but, shortly thereafter, Kaleva Cafe, a renowned Finnish American gathering spot serving traditional foods, also closed its doors after over a century of operation. A few years earlier, there was also the closure of Kukkakauppa, a flower shop located on the main street of downtown Hancock, which happened to be the same street where the Finlandia University and Kaleva Cafe were located. These closures sparked concerns about the future of Finnish American culture in the community. However, they also paved the way for change and the emergence of new ventures that embrace Finnish heritage in contemporary ways. In 2023, Ilo, an arts and craft store named after the Finnish word for “joy” or “happiness”, opened its doors. Shortly after, Nisu Bakery and Café (see Figure 2), a coffee shop featuring traditional Finnish and Finnish American products, became another Finnish-influenced establishment in the area. Opened also in 2023, Kuusi “Spruce” Mercantile is yet another example of a new Finnish-inspired business. Lastly, Kukkakauppa’s name changed to The Flower Shop, still featuring Finnish items despite a change in ownership.

Figure 2.

Nisu Bakery and Cafe in Hancock, Michigan.

Additional entities in the surrounding areas have also popped up such as Kuusi Modern Mercantile in 2023 and the Copper Island Academy, a charter school that implements Finnish education practices, in 2020.

The school’s website homepage emphasizes its Finnish connection by incorporating the concept of sisu, a Finnish term that signifies perseverance, with the motto “Community, Excellence, and a Dash of Sisu”.4

In Hancock and neighboring towns, Finnish culture is prominent. Finnish influence is evident everywhere, from the abundance of cars with Finnish license plates to the use of Finnish business names and Hancock’s bilingual Finnish and English street signs. Personal expressions of Finnishness, such as Finnish-themed clothing, car accessories (see

Figure 3), and items sold at local markets, further contribute to the pervasive presence of Finnish culture in the area. These items often express claims to Finnishness and provide context to the attitudes and ideologies held by those who embrace them.

Figure 3.

TGIF, THANK GOD I’M FINNISH license plate.

2.4. Areal Focus: Duluth in Northern Minnesota

Duluth, Minnesota, emerges as the second geographical focus of this research, with the city earning the nickname “The Helsinki of America”, as noted by Alanen in his book on The Finns in Minnesota (Alanen 2012, pp. 22–23), emphasizing its significant ties to Finnish culture and heritage. Historically, Finnish Americans from smaller communities have traveled to and from Duluth for work, fostering connections with smaller Finnish American enclaves like Oulu, Wisconsin (Johnson 2018, p. 35). The existence of direct flights between Helsinki and Duluth in the 1980s underscored the significant Finnish presence in the area and the Upper Midwest as a whole. Nowadays, Duluth has a Nordic Center, which contributes to its broader Nordic identity beyond Finnish heritage. This is evidenced by approximately one-third of the Duluth population identifying with Nordic roots, as indicated by the United States Census Bureau (2012). The city serves as a hub for prominent Finnish American figures and cultural endeavors, notable among them being the celebrated young Finnish American musician, Steve Solkela, and Cedar and Stone Sauna, a rapidly expanding sauna business founded by Finnish American Justin Juntunen.

Moreover, FinnFest USA5, the largest festival celebrating Finnish and Finnish American culture and heritage in North America, has chosen Duluth as its home base for five consecutive years. Marianne Wargelin, President of FinnFest USA, attributed this decision to Duluth’s superior infrastructure compared to smaller, historically Finnish American towns that lacked adequate logistical support and public transportation accessibility (26 March 2024). The decision to choose a location with Nordic ancestry for events such as FinnFest USA underscores a strategic approach and signifies an openness to expand beyond solely Finnish interests exemplified by the “Experience Nordic Culture” (see Figure 4) statement on the advertising poster of FinnFest. The researcher’s presence during the 2023 FinnFest in Duluth may have influenced the expressions of Finnishness observed, leading to a greater abundance of public displays compared to what may be seen on an average day. Nonetheless, Figure 5 displays a car belonging to a resident of Duluth adorned with a blue cross reminiscent of the Finnish flag, a permanent fixture that extends beyond the scope of FinnFest and performativity as a result of the festival.

Figure 4.

FinnFest poster, “Experience Nordic Culture”. Source: FinnFest USA.

Figure 5.

Car made to look like the Finnish flag.

The Finnish presence in Duluth and Hancock is expected to bring forth abundant expressions of Finnishness in these towns and their surrounding regions. The work of scholars described in this section made the present study possible and set the stage for further investigation. Exploring how attitudes and ideologies manifest in these settings calls for qualitative and ethnographic methods to understand how community members express their Finnish American identity, including with attitudes and ideologies, with an eye toward uncovering generational differences.

3. Methodology

The findings of this study are derived from participant observation, narrative interviews, and the collection of material ethnography. This comprehensive approach enabled a holistic exploration of the HL contexts under investigation. Participant observation (DeWalt and DeWalt 2011; Papen 2019) played a pivotal role in understanding the extent of Finnish usage publicly and the expressed ideologies within the HL community. With this method, I transitioned between the roles of observer and participant, actively engaging with the community while maintaining a passive stance when necessary. Effective listening skills and a genuine interest in the experiences and perspectives of community members were crucial for successful participant observation (Papen 2019, p. 144). This method was further enhanced by narrative interviews (Ochs and Capps 2001) that sought to capture participants’ personal stories and life experiences.

Through these interviews, this study aimed to uncover prevailing attitudes and ideologies by exploring interviewees’ experiences of growing up Finnish American, their current engagement with their heritage, and reflections on how these matters have evolved over time. Interviews were essential as they provided personal anecdotes that offered in-depth contexts to answer the research questions, enriching the understanding of observed phenomena. As highlighted by Scollon and Scollon (2003), ethnographic methods are indispensable for comprehending the nuances of semiotics and sociolinguistic phenomena, as “only an ethnographic analysis can tell us what users of that semiotic system mean by it” (p. 160). This emphasizes the importance of employing qualitative methods like participant observation and interviews to grasp the meanings behind observed behaviors and linguistic practices. Unlike sociolinguistic interviews, narrative interviews prioritize participants’ subjective experiences and storytelling, allowing for a deeper understanding of individuals’ lived realities.

The final method employed in this study involved gathering material ethnography (Pahl 2004; Lane 2008; Karjalainen 2012), primarily through the collection of pictures. Building on the research of Remlinger (2006, 2009, 2016, 2018) and Remlinger and Karinen (forthcoming), this method highlighted the expression of Finnishness through material culture and the linguistic landscape. The expression of Finnishness extends to the home, prompting the collection of material ethnographic data beyond public expressions to include material presented by interviewees, with their permission. This approach resonates with the work of Karjalainen (2016), who emphasizes the importance of incorporating multimodal resources such as pictures and artifacts to enrich the study of heritage culture.

3.1. Data Collection

In June 2022, I spent two weeks in the Hancock area for a previous research study, which provided valuable insights and facilitated connections with local residents. Following this, I conducted five weeks of participant observation in Northern Minnesota and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan in 2023. During this trip, I primarily stayed in Hancock, Michigan, and Duluth, Minnesota. Interviews were mainly conducted in these two towns and expanded to locations within approximately a three-hour radius by car. The research trip culminated at the 2023 FinnFest in Duluth, Minnesota, where I observed Finnishness on a larger scale and presented this study’s initial insights.

Interviewees were recruited for this research through a combination of personal contacts and the snowball sampling technique. Leveraging existing connections, some participants were initially identified among individuals known to the researcher. Subsequently, the snowball effect was employed, wherein these initial participants referred the researcher to other potential interviewees within their networks. This approach identified a diverse range of participants who provided perspectives on various aspects of Finnishness from different towns surrounding the main research sites, as well as a wide range of participants from different age groups. The interviewees had the choice of where to conduct the interview to ensure that they felt as comfortable as possible. Most interviewees invited me into their homes for interviews, one interview took place in a local cafe, three at FinnFest in Duluth, one on Zoom, and three at the house I stayed at in Hancock, Michigan. The question guide for the interviews is provided, refer to Appendix A. These questions guided the conversation, follow-up questions highly varied based on what the interviewee wanted to tell to the researcher.

My positionality as a semi-insider is shaped by my identity as a Finnish American. I was raised in lower Michigan, with family ties to the Hancock area in the Upper Peninsula, where my grandparents grew up and maintained a cabin where they spent time annually after moving to the Lower Peninsula. As a child, I visited the area several times, which familiarized me with the Finnish cultural importance of, for instance, sauna. While I did not grow up speaking Finnish, I became fluent after moving to Finland in 2017 to study the language. At the time of writing this article, I have lived in Finland for seven years. Moreover, my experiences living in Finland and fluency in Finnish hold significance within Finnish American communities, and this aided me in finding interviewees. This unique positionality granted me insider access to certain cultural and linguistic aspects while also positioning me as an outsider as an academic in the research setting. This dual perspective inevitably influenced the framing of the research questions and the methodologies selected. Throughout this study, I aim to maintain reflexivity and critical self-awareness, leveraging my semi-insider status to enrich the research findings while mitigating any biases that may have arisen.

3.2. Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to systematically examine the interview data, identifying recurring themes and patterns in participants’ responses. Thematic analysis was conducted following the six phases outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006): (1) familiarization with the data, (2) coding the data, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the final report. In phase one, I reviewed the dataset twice before coding it in phase two, a process of labeling data to capture the meaning of occurrences. Selective coding was applied to concentrate on specific themes deemed particularly relevant to the research questions. Some examples of codes include “young people”, “shame”, “local identity”, “older generations”, “change’, “correction”, “correctness”, “nostalgia”, and “pride”, among many others. The codes were then separated into themes that focused on language ideologies and generational shifts. The themes were developed by examining high occurrences in the data and ideologies that stood clearly in the data, as was the case with linguistic purism, with the example of the pronunciation of sauna, as we will see in the analysis. The findings of the thematic analysis are visualized through the use of diagrams that answer the research questions in the Analysis section. These diagrams were made on Canva. This approach enabled a focused and efficient analysis, aiding in the identification of key language attitudes and ideologies among the interviewees.

3.3. Participation Criteria and Participant Profiles

The primary criterion for participation in this study was that individuals identify as Finnish American or feel a strong connection to Finnish American culture and heritage, possibly through a relationship or marriage, studying Finnish, and/or residing in an HL community. In the latter case—when one did not identify as Finnish—they are referred to as non-Finn in the excerpts throughout the analysis. Some participants, for example, expressed enthusiasm to involve their partners or family members who self-identified as adopted Finns. Given this study’s focus on attitudes and ideologies, the perspectives of these semi-insiders were particularly intriguing and enhanced the research. These interviewees played active roles in the construction of Finnish identity both in their personal lives and in the larger community.

Of the 35 interviewees, six did not claim Finnish ancestry, meaning the vast majority identified as Finnish American. In total, 36 participants took part in this study, spanning a diverse range of ages. The data appeared skewed toward older participants. Identifying participants from the 18–35 and 36–50 age groups was slightly more challenging. Although I conducted research in areas with higher education institutions nearby, my visits during the summer months coincided with a period when classes were not in session, and many students and families were likely on vacation. Due to the limited time available during FinnFest, I was unable to conduct as many interviews as initially projected. Many participants who were interested in participating could not find the time due to the festival’s full schedule. This time constraint hindered the balance of the data. Given more time, I would have been able to interview additional participants, which would have contributed to a more balanced dataset.

During the analysis phase, data were grouped into four age categories to explore potential generational variations. Factors such as gender identity, socioeconomic status, and occupation were not considered relevant to the research objectives and, therefore, were not included in the interview questions posed to the participants. The age of interviewees was deemed relevant and is therefore reported, as there was interest in understanding potential generational differences within this study.

3.4. Research Ethics

In conducting ethnographic research on Finnish as an HL, I was dedicated to upholding the rights, well-being, and wishes of my research participants. I prioritized ethical conduct throughout the fieldwork and in the writing of this publication. Drawing on the four “r” words of ethical research outlined by Rice (2012) and guidelines from TENK (The Finnish National Board on Research Integrity), I centered my approach on (1) respect, (2) relationship, (3) reciprocity, and (4) responsibility. I thoroughly explained the purpose of this study, the intended use of collected data, and the rights afforded to participants. I obtained informed consent, either orally or in writing, for the use of their data and the recording of interviews. I also obtained consent to take pictures of their personal items and received their permission to use them in my research. Lastly, I informed participants of their right to withdraw from the research at any time and they were provided with my contact information for further inquiries or withdrawal requests. All figures in this article are my own, unless stated otherwise, and have been taken and used with permission. Any names mentioned have also been mentioned with permission.

4. Analysis

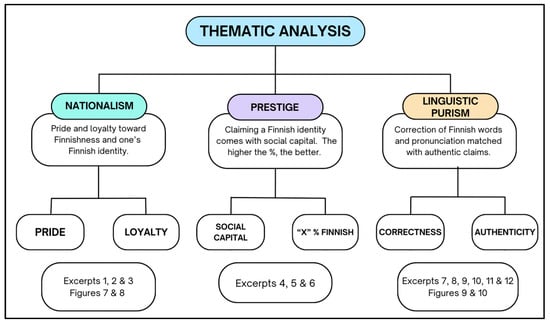

In this section, I address the main research question regarding prevailing language ideologies using a thematic analysis diagram below (Figure 6). I address the second research question regarding generational differences in Section 4.4, in which the evolution of terms like Finlander suggests generational change and reflects a history of friction with individuals not identifying as Finnish. My findings highlight a pronounced pride and attachment to Finnish identity, which discursively and ideologically shape a sense of belonging and serve as a foundation for Finnish American identity formation. Furthermore, the findings reveal ideologies of authenticity and purity that underscore the esteemed value placed on claiming Finnish identity, along with the social and cultural capital it brings. The following diagram answers the first research question: How do attitudes and ideologies toward Finnishness manifest in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and Northern Minnesota? Throughout the analysis, I interpret these findings with excerpts and ethnographic material.

Figure 6.

Thematic analysis diagram of attitudes and ideologies toward Finnishness.

The formation of a Finnish or Finnish American identity is marked by a complex interplay of attitudes and ideologies that often coexist and intertwine. As outlined in Section 2.1, distinguishing between attitudes and ideologies can be challenging, and the same holds true for the findings of this study. While the excerpts analyzed below can be categorized into their respective sections, they frequently overlap and interact with each other in nuanced ways. The following paragraphs contextualize these findings with excerpts, images, and findings from participant observation.

The pervasive presence of Finnish identity in Hancock, Duluth, and its surroundings is unmistakable, permeating the multimodal landscape. During my observations in Hancock, I was struck by the unexpected sound of the Finnish national anthem resonating through the streets, emanating from a local church. Similarly, in Duluth, I encountered a car adorned with the blue cross from the Finnish flag prominently affixed to its sides. The unmistakable emblem of the Finnish flag was ubiquitous in both locations. These manifestations underscored the significance of Finnishness and provided valuable insights into the pride and nationalistic ideology that emerges in places where the Finnish identity occupies physical and cultural space.

The most prevalent ideology encountered in this study was nationalistic, associated with a strong sense of pride in being Finnish American and a deep loyalty to one’s roots and heritage. Additionally, the prestige associated with Finnishness and purist ideologies was also abundant. As mentioned previously, this study does not aim to quantify these attitudes and ideologies but rather to describe their presence, allowing for future research in the Finnish HL context and facilitating comparisons with other HL contexts. The remainder of this section delves into the findings, utilizing images, excerpts from interviews, and observations from the research sites to provide a comprehensive overview. The findings are divided to address the main research questions. That is, Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3 discuss attitudes and ideologies describing the findings visualized in Figure 6 that answer the research question: How do attitudes and ideologies toward Finnishness manifest in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and Northern Minnesota? Section 4.4 describes the generational differences that answer this study’s second research question: What discernible generational differences, if any, characterize attitudes and ideologies toward Finnishness among Finnish Americans? In the excerpts below, names and places have been replaced with pseudonyms to protect the anonymity and privacy of the interviewees. Excerpts denote UP (Upper Peninsula), NMN (Northern Minnesota), and non-Finn to indicate the community the interviewee identified with. Excerpts with … reflect a pause in speech and […] indicates that a portion of the text has been removed. When citing excerpts from interviews, I provide A–E in parentheses, which correspond to the age group in Table 1. For example, (C) refers to an interviewee aged 51–49.

Table 1.

Distribution of participants’ ages.

4.1. Nationalistic Ideologies

The term nationalism can carry significant political weight. In this study, however, it refers exclusively to the pride and enthusiasm for Finnish culture, with no exploration into its political dimensions. The presence of nationalistic ideologies tied to pride for and loyalty to (see Section 4.1.1) one’s Finnish American identity was abundantly clear through the participant observations and consistently expressed in all interviews. As such, the predominant finding of this study is the profound sense of pride associated with Finnishness. Finnish Americans often do not need to verbally articulate this pride and loyalty regarding their Finnish ancestry; instead, they express it through a multitude of ways. This became evident through participant observations, as individuals consistently showcased and wore items that helped in their Finnish American identity construction. In interviews, participants brought family heritage books, wore t-shirts featuring Finnish sayings, and welcomed me into their homes with freshly baked nisu bread6 and coffee poured into mugs from Marimekko, a Finnish design brand.

4.1.1. Pride for and Loyalty to the Finnish American Identity

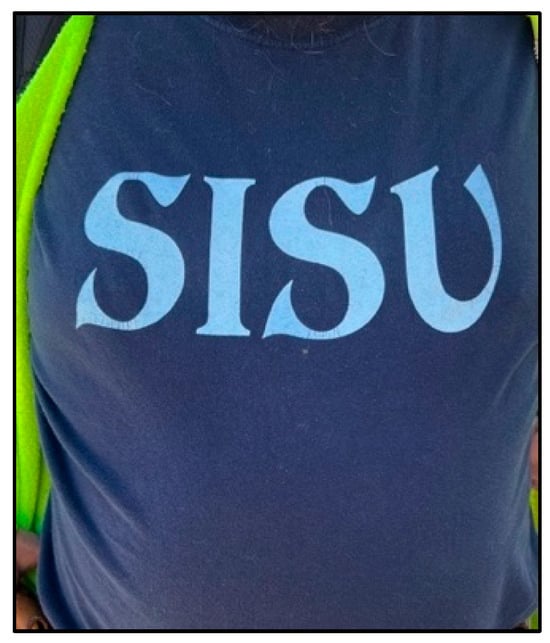

Nationalism regarding the Finnish American identity manifested in a multitude of ways, with my analysis focusing on pride and loyalty, two of the most recurring themes in this ideology. Differences between Duluth and Hancock were evident in the presence and public performativity of Finnishness. In Duluth, this presence was more transient, mainly confined to festival days and specific events. Conversely, in Hancock, the “performativity” reached a FinnFest level on a daily basis. In Hancock, it is nearly impossible to go about without encountering someone proudly displaying commodified items that express their Finnish identity, such as the sisu t-shirt in Figure 7. Hancock’s population is also twenty times smaller than Duluth’s and this evidently impacted the visibility and influenced my experiences during the participant observations.

Figure 7.

Sisu t-shirt in Hancock.

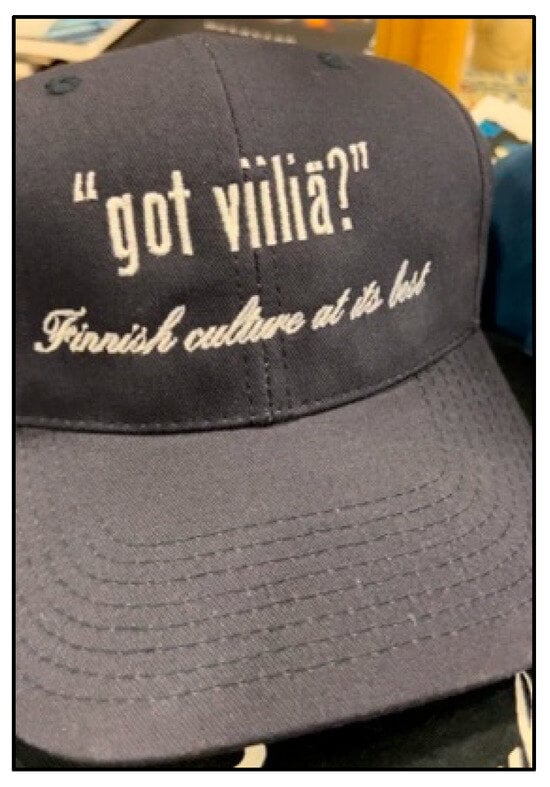

The majority of public manifestations of Finnishness in Duluth were associated with FinnFest due to my time there during the festival. One of the many manifestations found included a hat (see Figure 8) referencing the practice of making viiliä, fermented or cultured milk, a practice that remains common among Finnish Americans in Northern Minnesota. In fact, the hat was made with a clever double meaning playing off the English translation, “cultured milk”. The hat’s designer, Steve Leppälä, skillfully utilized this linguistic subtlety, and thus the hat features the phrase Finnish culture at its best. This interpretation features indexical meaning (Silverstein 1979) because it is understood by Finnish Americans, and, more specifically, those in Duluth. These findings also relate to what Karjalainen (2016), who studied Finnish Americans in Seattle, describes when Finnish Americans have objects that allow them to express their identities as Finnish Americans and not solely as Americans. Karjalainen explains that these manifestations connect to authenticity (Pennycook 2007) in relation to discourse on identity and belonging.

Figure 8.

“Got viiliä” Finnish culture at its best hat at FinnFest 2023.

These material expressions of Finnish pride and loyalty were echoed in the interviews conducted in both the Hancock and Duluth areas, as demonstrated in Excerpts 1 and 2, where interviewees expressed pride in claiming a Finnish American identity.

- Excerpt 1—NMN

“[At the event,] I told them I’m Finnish, I’m English, I’m Scottish, I’m Irish, I am a lot of things but when people ask me, I say I’m Finnish. It is really [up to] what you claim and what you’re excited about”.(36A)

- Excerpt 2—UP

“I worked at Post Office with a guy called Dan, for my whole working career until he retired first. His famous saying was, he is originally Copper Harbor, ‘you know what I’d be if I wasn’t Finnish..ashamed!’ [laughter]”.(18D)

- Excerpt 3—NMN

“Sometimes I wonder if I am too ethnocentric. I don’t want people to think I am excluding their culture or anything else. I welcome all cultures, I really do, and try to always”.(32C)

The statement in Excerpt 1 reflects a nationalistic ideology that underscores loyalty to their Finnish heritage and the simultaneous pride they take in it. The speaker also acknowledged their diverse ancestral background, yet Finnish was what they most engaged with and were enthusiastic about. Excerpt 2 highlights another manifestation of pride and loyalty within the Finnish American community. The anecdote exemplifies a humorous expression of pride. The remark, “you know what I’d be if I wasn’t Finnish…ashamed!” accompanied by laughter, illustrates a comical yet sincere embrace of Finnish identity. This attitude is reverberated by material culture such as the TGIF, THANK GOD I’M FINNISH license plate in Hancock (see Section 2.3). This anecdote reflects the strong sense of loyalty and camaraderie among Finnish Americans, as well as their pride in their cultural heritage, coming together to form a nationalistic ideology.

However, it is important to recognize that such expressions of belonging may also lead to exclusion within heritage communities, where certain identities take precedence (Remlinger and Karinen, forthcoming). While these comments were sincere from the Finnish American participants of this study, they also highlight the potential for exclusion within heritage communities, where certain identities may be prioritized over others. In Excerpt 3, one Finnish American expresses concern about being too ethnocentric. Their statement reflects an important first step to ensuring inclusivity in the reality of multicultural American communities. Further research with individuals who do not identify as Finnish or have close connections to the Finnish community is necessary to fully understand this dynamic.

4.2. Prestige of Finnish and Finnishness and Relevant Attitudes

While nationalistic ideologies related to pride and loyalty are prevalent, it appears that this has not always been the case, as I will explore in this section. I will examine the association of Finnishness with social and cultural capital and discuss its manifestations through exclamations claiming percentages of Finnish ancestry and claims of cultural authenticity. This prestige seems to have evolved over time; historically, Finns changed their last names to assimilate, and there was a reluctance to embrace Finnish identity due to social exclusion. The evolution of the term Finlander is an example of how the term has evolved over generations, which is discussed in Section 4.4.

4.2.1. Prestige

The prestige of claiming a Finnish identity has evolved since Finns initially migrated to the Upper Midwest to work in the mining and logging industry. As mentioned in the introduction, this study was partly motivated by overhearing someone say that their partner “had to get rid of his Yooper accent, he sounded Finnish and uneducated”, which is intriguing given how Finnishness is held in high regard, while the regional ways of speaking in these areas historically have not been considered prestigious. As Remlinger (2016) puts it, “identity and language attitudes are inseparable”, and, since the Yooper and Finnish identities overlap significantly (Remlinger 2017), this observation is particularly intriguing. In both research sites, several interviewees recounted how their ancestors changed their names to mitigate social exclusion and secure employment, reflecting the negative attitudes toward Finns during that era. This phenomenon directly relates to the term Finlander, a significant finding discussed in Section 4.4 due to its connection to generational changes. Contemporary Finnish Americans no longer feel the need to conceal their identity; in fact, some have actively reclaimed their Finnish last names. Prestige refers to the respect and admiration given to someone or something based on its perceived value or status. In this study’s case, the prestige that is associated with Finnishness is exemplified in Excerpts 4 and 5.

- Excerpt 4—UP

“In my parents’ generation, it was still very common for Finns to marry Finns and Croatians to marry Croatians. However, it started to change, and many began marrying outside their ethnic group. But among Finns, if you mentioned, ‘Oh, my daughter is getting married’, or ‘My son’, instinctively, people would ask, ‘Onko hän suomalainen tai toiskielinen?’ Because ‘toiskielinen’ meant anyone other than a Finn. When my parents got engaged, my father was Finnish and my mother wasn’t. He went and told his parents, and his mother cried. My mother went and told her parents, and her mother and grandfather cried. The neighbor was there, and she was very dignified. She said, ‘Well, my daughter isn’t going to marry a Finn’. And um, she did; she married a Finn. The woman said, ‘Well, he’s an educated Finn’ [because] he had gone to Suomi College”.(D)

Excerpt 4 also demonstrates an example of language attrition—the gradual reduction or loss of language knowledge over time—where the use of tai “and/or” is used where vai “or” should have been used. Since the language has not been actively transmitted and is primarily used symbolically or for indexing one’s identity, it is understandable that words or sayings are misused or not maintained in their standard form. Other examples of attrition are the loss of umlauts on Finnish words, Anglicized pronunciations of Finnish words, and simplifications of double consonants to one, such as Amerikka “America” to Amerika, among others (Remlinger and Karinen, forthcoming). During this fieldwork, I also observed a few speakers say juustoa “say cheese” when taking photos. The phrase “say cheese”, commonly used in English, has been American–Finnishisized, as this is not used in Finland. In addition, this observation is a verbal confirmation of what Remlinger and Karinen (forthcoming) notice with the use of juustoa7 “cheese”, which has been fossilized in the partitive form in the written use of Finnish in the Finnish American areas under study. It is interesting because the word appears in the partitive form juustoa rather than the nominative juusto. I also observed the same phenomenon with kahvia “coffee” and nisua “sweet cardamom bread”. These findings relate to what Kühl and Peterson (2018) find with morphosyntactic features in the Danish HL community in Sanpete County, Utah, where speakers add the English plural marker -s to words, despite the Danish words already featuring the enclitic plural marker -er or -r. I would argue that this is the same in the Finnish American heritage communities under study because locals were likely to say “I need to get me some juustoa”, where the partitive marker -a means “some”. These observations illustrate the impact of language attrition in the Finnish American communities under study, highlighting how linguistic features can change or simplify over time when a language is not actively maintained or transmitted.

Excerpt 5 provides an illustrative example of the prestige associated with Finnish cultural knowledge, as demonstrated by a teacher who was commended by non-Finnish Americans for a project where students explored various topics related to Finland and Finnish culture. This excerpt is significant because the interviewee specifically noted that non-Finnish Americans were the most appreciative, suggesting that within the local community, understanding Finnish cultural elements was essential for full community integration and recognition at that time.

- Excerpt 5—UP

“She would do a six-week-long series. The children would pack these backpacks, which was a paper grocery sack. They would put all the little projects in the sack. At the end, they would take them out, and they would talk about what they discovered, going to Finland in their minds, and she would have a little program at the end, and the parents and grandparents could come in. They would bring her gifts, and they would cry, bake her bread, and all kinds of stuff. In the end, she said it was really interesting. The people who were the most appreciative of it were families who had moved here, and their children were in the program. They said, ‘it helps us and helps our children understand the community’. Other teachers who had done Finnish things as well get a lot of recognition in the community for it”.(D)

Together, Excerpts 4 and 5 convey conflicting notions regarding the status of Finns in the local community of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Excerpt 4 echoes the notion introduced earlier in this section regarding education, suggesting a prevailing stereotype that Finns were generally perceived as uneducated. Simultaneously, there was historically prestige associated with marrying another Finn. This attitude was affirmed by an interviewee in Minnesota, who recalled that marrying a non-Finn was “a scandal”. However, the interviewee added that “it is no more, which is good”, noting that such attitudes are no longer prevalent, which is interpreted as a positive development toward higher inclusivity among Finnish Americans. Excerpt 5 illustrates the significant regard for Finnish culture, to the extent that schools occasionally devoted several weeks to studying Finland. The prestige of Finnishness extended beyond the Finnish community, as indicated by the teacher’s observation that non-Finns were among the most appreciative participants. These individuals recognized the social and cultural significance of Finnish heritage, emphasizing its importance in the Upper Peninsula.

4.2.2. Social and Cultural Capital

The social and cultural capital associated with claiming a Finnish identity appeared to be more pronounced in Hancock than in Duluth, likely due to the higher percentage of Finns in the former. Regardless of their location, Finnish Americans often felt the need to quantify their Finnish heritage, with a higher percentage seen as more favorable. During participant observation, individuals frequently made statements such as, “I’m 30% Finn!” as a way to assert their identity. While these statements were out of a need to identify oneself, one interviewee recalled a situation where there was a comment at their workplace where someone exclaimed that another person got the job because of being Finnish, suggesting that this person’s Finnish last name also helped. This suggests a tension between those who identify as Finnish and those who do not, as well as the perceived advantage of being Finnish in terms of gaining social and cultural capital. The person who made this claim was not Finnish yet recognized the value of having the identity and having a Finnish last name. In short, locals without Finnish connections recognized the significance of Finnish names and claiming a Finnish identity. Excerpt 6 reinforces this attitude, with a comment that was a complaint by a non-Finn recited by a Finn, who recalled community members feeling that Finnishness had a higher place in the community.

- Excerpt 6—UP

“They complained a lot.. ‘if you want any money for that, you have to give it a Finnish name’”.(D)

This comment underscores the perception that anything associated with Finnish culture holds inherent value, which can extend to influencing decisions, including in matters such as securing funding. This relates to what Shandler describes as common in Yiddish as a postvernacular language, where they describe that “the symbolic level of meaning is always privileged over its primary level” (Shandler 2005, p. 22). In the case of this study, this means that the symbolic value of Finnish identity and cultural markers often outweighs their practical use, granting individuals with Finnish heritage certain advantages. The meaning of the business, last name, or phrase in Finnish is not as important as the fact that it is Finnish. In essence, the social and cultural capital associated with Finnish identity shapes both individual experiences and community dynamics. It influences how people perceive themselves and others, guides social interactions, and can even impact economic opportunities.

4.3. Purist Ideologies

Purist ideologies deal with the perceived correctness and authenticity of language use. In this study, the most prevalent findings dealt with the pronunciation of Finnish last names and sauna, which is a Finnish American shibboleth feature (Remlinger 2018, p. 266). There were also tensions regarding what is “truly Finnish” because the Finnish American culture is different from modern Finnish culture. An interesting finding was the approximation to the standard Finnish pronunciation of words among Finnish Americans, creating three to four recognizable variants of pronunciation for words like sauna and last names such as Juntila, as presented in the excerpts below.

4.3.1. Finnish American Authenticity

Due to the closure of Finlandia University and the uncertainty surrounding the future of the Finnish American Heritage Center and Finnish American Folk School—two entities previously managed under Finlandia University—there were debates regarding the ideal location for the heritage center if it were to continue functioning. Advocates proposed various options: some argued for Duluth due to its strategic location, others advocated for staying in Hancock to preserve the Finnish presence and historical significance, and some suggested relocating it to Minneapolis, citing the city’s status as a metropolitan hub with better connectivity to other communities and global networks. The discussions surrounding these options bring us to the ideology of authenticity. Oftentimes, arguments in these discussions revolved around which place was the most authentically Finnish. Ultimately, Finlandia Foundation National (FFN)8 decided that the heritage center should remain in Hancock, and Excerpt 7 is an example of the authentic Finnishness outwardly displayed by the town that likely aided in this decision. The FFN played a crucial role following the closure of Finlandia University in May 2023. By raising funds, the FFN successfully took over operations of the Finnish American Folk School, Finnish American Heritage Center, and North Winds Bookstore, all previously managed by Finlandia University.

- Excerpt 7—UP

“The Finnish American Heritage Center has had interns that have come from Finland to work there. They have gone home knowing how to play the kantele, that they didn’t know how to play before. I remember seeing some of them in the Heikinpäivä9 parade saying ‘oh my gosh, this is more Finnish than Finland is’”.(D)

The significance of this excerpt to a Finnish American lies in the implicit acknowledgment that authenticity in Finnish culture transcends geographical boundaries. When a Finn asserted that something was “more Finnish than in Finland”, it served as a validation of cultural authenticity and adherence to traditional practices, and, more importantly for the topic of this section, reinforced Hancock as an authentic Finnish place. Finnish Americans nowadays do, however, recognize that the Finnish culture in Finland is not the same as that in Finnish American communities, as understood by Excerpt 8.

- Excerpt 8—UP

“For me, I think it is important to recognize people as Finnish Americans. It’s a distinct culture. And I think we do one of two things either we are constantly trying to be even more Finnish and do everything here as it is done in Finland, which is not possible. Or else we embrace what we have figured out, we’ve accommodated being in America, and we have remained Finnish. For someone like me, and I know I’m not the only one, it is not enough to be American. It is simply not enough… it’s like taking a plant and planting it in new soil under new conditions and it still can thrive”.(D)

This sentiment was juxtaposed by another interviewee who did not identify as Finnish and had observed a vibrant atmosphere of innovation within traditional Finnish artistic expressions in Finland. In contrast, they perceived a more conservative approach within Finnish American artistic circles.

- Excerpt 9—Non-Finn

“[in Finland] they are making new music, creating new things, there is a lot of improvization and experimentation and composition happening and collaboration with other genres..just like in any vibrant arts or music scene, here sometimes.. there’s.. a. I’ve witnessed a little bit of a box.. there is sort of these expectations [from Finnish Americans] of ‘what my grandparents did’ or ‘I’ve never heard of that.. is that really so Finnish’”.(B)

Excerpt 9 provides a contrasting perspective to Excerpts 7 and 8. While Excerpts 7 and 8 emphasize the importance of preserving traditional Finnish practices and values, Excerpt 9 suggests that Finnish American circles may sometimes exhibit a more conservative approach, with expectations rooted in nostalgia for past traditions. This observation implies a tension between preserving cultural authenticity and embracing innovation within Finnish American communities.

4.3.2. Correctness

In exploring Finnish American identity, the concept of correctness emerged as a significant theme. At the forefront of this discussion was the pronunciation of Finnish words, with sauna serving as perhaps the most prominent example (Remlinger 2017; Rankinen and Ma 2020). Within Finnish American communities, correct pronunciation holds considerable cultural significance, as illustrated by anecdotes of frustration and humor surrounding mispronunciations of Finnish last names in Excerpts 9, 10, and 11. These excerpts shed light on a purist ideology that emphasizes the importance of linguistic authenticity in preserving Finnish heritage. Moreover, they underscore the belief that mastering correct pronunciation is not only a matter of linguistic accuracy but also a reflection of one’s genuine Finnish identity.

- Excerpt 10—UP

“The Finnish stuff that resonated with my great grandparents or even my kids… there are differences in the things that resonate while there are also similarities. If my kids hear someone mispronounce sauna, they will be the first to make sure that person knows. I mean.. I’ve seen them do it…”.(B)

Excerpt 10 illustrates how mispronunciations, particularly of sauna, prompt correction from Finnish Americans, reinforcing the value placed on linguistic purity. Excerpt 11 reflects a similar attitude, where mispronunciations of Finnish last names are corrected. However, as seen in Excerpts 11 and 12, individuals with Finnish last names may not be familiar with either standard Finnish or the Finnish American variant. Given that many Finnish Americans are several generations removed from their Finnish roots and may not speak Finnish, it is unreasonable to expect them to be knowledgeable about standard Finnish pronunciation.

- Excerpt 11—NMN

“I said to Professor Jussila [dʒˈusɪlə} ‘do you really want people calling you Jussila [dʒusiˈlɑ]’”.(D)

This statement reflects a purist ideology regarding pronunciation. Subconsciously, knowing how to pronounce these names is seen as a marker of Finnish identity and is valued, although these pronunciations are simply an approximation of standard Finnish. One young Finnish American shared that they regularly interact with Finnish Americans in their work and that they find humor in situations when they are hypercorrected by clients with Finnish last names, as seen in Excerpt 12.

- Excerpt 12—NMN

“I said Järvelä [jærʋelæ] and the client corrected me and said, no, it’s not Järvelä, it’s JärVElä [dʒærʋeˌlæ]”.(A)

This interviewee obtained an intermediate proficiency in Finnish through study at Salolampi,10 an intensive language camp. Thus, they were familiar with the language and pronunciation guidelines. They went on to explain that they sometimes had three different pronunciations for certain last names, such as Jurmu.

| [ˈjurmu] | Standard Finnish pronunciation |

| [juːrˈmʊ] | Finnish American |

| [dʒurˈmuː] | Non-Finn11 |

These examples are illustrative of attrition that has taken place now that the Finnish heritage is so removed, meaning that Finnish Americans are several generations down the line and no longer first-, second-, or even third-generation Finnish Americans. In addition, this anecdote reflects my findings on the pronunciation of sauna. There is the standard Finnish pronunciation, the common Finnish American pronunciation, a hypercorrected version influenced by the word “sow” to aid pronunciation (see Figure 9), and the non-Finnish American pronunciation. This hypercorrected version is a result of sow being a heteronym, a word that has the same spelling but different pronunciations and meanings.

| [ˈsɑunɑ] | Standard Finnish pronunciation |

| [ˈsaʊnə] | Finnish American (sow-na) |

| [ˈsoʊnə] | Hypercorrection (sow-na) |

| [ˈsɑ:nə] | Common U.S. pronunciation (saw-na) |

Figure 9.

Sauna sign for sale at FinnFest 2023.

The sauna sign for sale at FinnFest 2023 (see Figure 9) exemplifies linguistic purism, featuring a prescriptive guide on the pronunciation of sauna. This sign also illustrates the commodification of Finnish as an HL, a phenomenon also observed with the HL of French and Cajun English in New Orleans (Dubois and Horvath 2000; Eble 2009). Such commodification of language indicates that the practice is prevalent across HL communities.

The “correct” pronunciation of sauna is indexical (Silverstein 1979) because it signifies more than just the word’s phonetic form; it also signals social and cultural identity. In Finnish American heritage areas, using the “correct” pronunciation of sauna indicates an authentic Finnish American identity and is valued. This example of sauna also demonstrates how I, the researcher, was more of an outsider than an insider in the community because I understood the hypercorrection version through the reference instead of the indexically “correct” pronunciation in Figure 9. In addition, I employ the common U.S. pronunciation when speaking English and grew up saying it that way. It is also worth mentioning that there are inevitably more ways to pronounce sauna than noted; these were the main four pronunciations recognized by the researcher. Nonetheless, sauna is a prime example of how purist correction can lead to hypercorrection.

Collectively, these examples illustrate how correctness in pronunciation serves as a point of pride and identity. Finnish Americans exhibit an approximation to standard Finnish pronunciation, with many words and names that are not quite the non-Finnish way yet not quite the standard Finnish pronunciation either. By employing this variation, individuals signal their authentic Finnish American identity. In addition, this matches with what Garrett (2010) describes regarding (1) cognition, (2) affect, and (3) behavior (23). In the example above, this would correspond as such:

- (1)

- The belief of Finnish Americans that there is only one way to pronounce sauna.

- (2)

- Feelings of discomfort or disdain toward other pronunciations of sauna.

- (3)

- Actively making sure to prescriptively correct someone when they pronounce sauna in a manner that does not match with what Finnish Americans consider “correct”.

In alignment with the three phases is another example: an interviewee’s mug (see Figure 10) with the phrase “I’m silently correcting your pronunciation of sauna”. This is another example of linguistic purism that has been commodified and its purchase exemplifies the behavior phase outlined by Garrett (2010). The phrase on the mug exemplifies purist ideology, implying that there is only one “correct” way to pronounce such words, and silently correcting others reflects a commitment to upholding this linguistic standard as a marker of authentic Finnishness.

Figure 10.

Mug.

4.4. Generational Changes

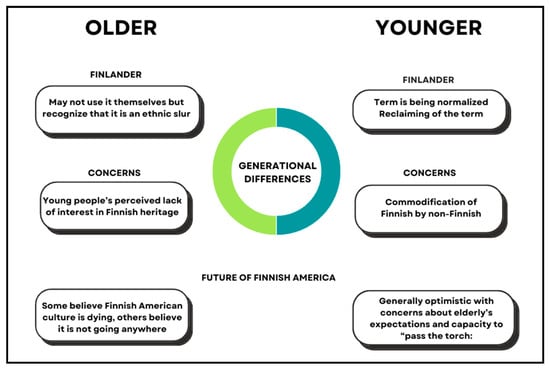

The most pronounced generational difference was the evolution of the term Finlander. In regard to concerns, the older generations tended to be concerned regarding the lack of interest in Finnish heritage among the younger generations (see Figure 11). Simultaneously, there was a strong trust that the presence of Finnish culture would remain for generations to come. On the other hand, the overall attitudes among young people were inconclusive. There were mentions of concerns regarding the loss of the Finnish spoken by older Finnish Americans and indications of concern regarding the commodification of Finnish by non-Finnish entities, but more research is needed to understand the attitudes and ideologies of younger generations. The figure below answers the second research question of this study: What discernible generational differences, if any, characterize attitudes and ideologies toward Finnishness among Finnish Americans?

Figure 11.

Mapping generational differences.

4.4.1. Finlander: From Ethnic Slur to Reclamation

The evolution of the term Finlander reflects the shifting attitudes and perceptions of Finns in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and Northern Minnesota over time. Older generations recalled a time when the term carried negative connotations, associated with derogatory stereotypes and linguistic discrimination. Many recalled their parents refraining from using the term and having strong feelings toward it from a period when the term carried negative connotations, often associated with derogatory stereotypes and discrimination. In Excerpt 13, the interviewee recounted being surprised to learn about its derogatory nature from their parent, indicating a generational shift in understanding. Excerpt 14 highlights the term’s linguistic and cultural discrimination and how it impacted one Finnish American’s choice to stop speaking Finnish as well as its association with the Yooper identity. However, Excerpt 15 suggests a reclaiming of the term among newer generations, signifying a transformation from a derogatory slur to a marker of cultural identity.

- Excerpt 13—UP

“I remember the first time that I might have used the term Finlander and my dad reacted—not real negatively—but he was like ‘oh you know, that’s kinda derogatory’ and I was like ‘it is?!’ I had no idea, I had heard people use it… he was like ‘oh yeah that used to be a slur!’”.(B)

- Excerpt 14—UP

“There used to be this phrase people used, ‘dumb Finlander’ and if you had that heavy broke [accent].. ‘dumb Finlander’ and a lot of times… same as southern, you speak a bit slower and there’s a great mover where the guy says, ‘Just because I talk slow doesn’t mean I’m stupid’, and people were embarrassed by that. I have to say I feel sad, I know that I had a very Yooper accent as a child, let off articles, and crazy things with prepositions and all that, and I lost all that, and I could recreate it but it wouldn’t be authentic anymore, and I love hearing it. I grew up in a family that we had a sense of pride in being Finnish. [...] My [partner] also grew up in the U.P. and she said, ‘you know we didn’t embrace the Finnishness because so many people would say dumb Fin lander’. And I met a girl just last summer she was umm, I think she was 4 years younger than me… and her grandparents, her grandfather was born in Finland and her mother was a daughter of immigrants and her grandparents insisted that she speak Finnish… So, I saw her after many years, and I said “so have you kept up your Finnish”, and she said “no, you know, I felt bad because I was different, and I let it go” and now she rues the day… and it was that dumb Finlander”.(D)

- Excerpt 15—NMN

“I would say that after 1900 is probably when they used it a lot, and definitely in a derogatory way towards Finns. I assume it had a lot to do with the blacklisting in the strikes that went on; I’m sure that’s where it started. It was definitely a derogatory term for many, many years. I do not know when we started to reclaim it. I would definitely say it is a Finnish American thing; you know, you see a lot of Finnish Americans use that word as a community term for each other. It is not derogatory anymore; I don’t know if I would go as far as to say that it is a term of endearment, but it is definitely a part of the identity of being Finnish American. I would say that it is definitely more claimed by people of my Finnish American generation. What I mean by that is people whose ancestors came in the late 1800s and maybe even in the early 1900s. But a lot of people who came later, their children and grandchildren, are not as apt to claim that word. My great grandmother, she was the one who actually started to teach me Finnish when I was little. Her grandfather was born in Finland, and I remember one of her last few years when she visited us at our house. It was a nice spring day, and she said a few things; one of the things I remember distinctly she said, ‘I sing because I’m happy.. I sing because I’m free.. I sing because I’m a Finlander, can’t you see?’ and I always love thinking about that”.(A)

The reclaiming of the term Finlander reflects a broader evolution in Finnish American identity. These generational shifts signify changing patterns in how individuals engage with the Finnish language and cultural heritage, shaping their identities on their own terms with the resources available to them. As these ways of interacting with the heritage culture continue to evolve, so do the attitudes and ideologies surrounding the preservation of Finnishness within these HL communities. Remlinger (2006) mentions the term “dumb Finlander” together with “dumb Yooper”, finding that the term “dumb Yooper” is being reclaimed as well. These evolving dynamics reveal how communities reshape their identity and cultural heritage, reflecting broader societal shifts in reclaiming and reframing terms like “Finlander” and “Yooper” in a more positive light.

4.4.2. “Many Times They Have Tried to Put the Lid on the Coffin and Sisu Pushes It Off”

The biggest concern among the older generations of Finnish Americans in Northern Minnesota and Hancock, Michigan, was the worry that young people are not interested in Finnish American heritage. The remaining elements discovered throughout the research came about in individual instances, not allowing for the generalization of any of these attitudes. For example, one interviewee said that the problem in their opinion was the lack of an attempt to attract the younger generations. A younger Finnish American, on the other hand, expressed concern about the commodification of Finnishness by non-Finnish entities. Another young Finnish American expressed concern about the inability of those in power to “pass the torch” and feared that this would have an impact on the future of the heritage culture.

Amidst these concerns, the emergence of new establishments dedicated to Finnish culture signals an active effort by younger generations to integrate local Finnish heritage on their terms while honoring and celebrating their Finnish cultural roots. In some cases, this shift may be a deliberate and necessary expansion, with, for example, FinnFest’s scope now reaching the wider Nordic audience. In other cases, it may reflect a desire to adapt Finnish traditions to contemporary contexts or explore new avenues for incorporating Finnishness. Apart from the concern to attract youth and “pass the torch”, the remainder of the discussions related solely to the HL community in and surrounding Hancock. Excerpt 16, for example, discusses the new charter school in Calumet that embraces Finnish education. Excerpt 17 reflects on the transition of Suomi College to Finlandia University, and the broader evolution of Finnish American identity with it. The interviewee acknowledged the resistance to change from some individuals who were upset about the college changing its name. However, the speaker emphasized that change was inevitable and that this is no different from the current circumstances in Hancock. While some individuals resisted change, others, like the speaker in Excerpt 18, recognized the persistence of Finnishness despite inevitable transformations.

- Excerpt 16—UP

“But there is this brand new Finnish model school that is developing, like that’s what people want to get behind, like they are looking to their Finnish roots and what is going on in Finland now and saying ‘hey, they have a great Finnish education system, what don’t we look into that?’ So, people are going to pursue what they see value. It may or may not be the same thing that their parents or grandparents [did]”.(B)

- Excerpt 17—UP

“There were people who were upset about Suomi College changing its name, and it’s like, you know, there was no way that this was still going to be a university for Finnish Americans at some point. Even before that, it always had people who weren’t Finns after they started using English as their language of instruction in the 20s. The institution that was created in 1896 had already undergone changes within 30 years, and it continued to evolve. It continued to enrich people’s lives. I know individuals with really fascinating interethnic backgrounds because their parents met at Suomi. That wouldn’t have happened if people hadn’t diversified and branched out. We wouldn’t have a café celebrating nisu if there hadn’t been some sort of gap in the local dining scene that allowed for that to happen. Gaps always get filled with what is needed to be put in that spot. There is going to be something new. These occurrences provide an opportunity for new things to emerge and for the Finnish identity of this area to have new meaning for new people”.(B)

- Excerpt 18—Non-Finn

“They may not look or sound the same as they did 100 years ago... they won’t, it’s not a ‘may’, they won’t look or sound the same as they did 100 years ago. But, they are going to continue, and through those things, language continues, and foodways continue. It is absolutely possible to remain vibrant even without institutions that we were familiar with. Moreover, I feel like it is a time of transition. I mean, the older generation is aging out of leadership, but that doesn’t necessarily mean there aren’t people who are ready to take it on—perhaps in a different way than previous generations, on their own terms. And I am seeing that in a lot of ways”.(B)

To conclude, the excerpts presented in this section shed light on the concerns surrounding the future of Finnish American heritage and culture in Northern Minnesota and Hancock, Michigan. Despite these concerns, there is tangible evidence of a proactive stance by younger generations to both integrate and preserve Finnish culture. This proactive effort is exemplified by the emergence of new establishments and initiatives dedicated to Finnish culture, signaling adaptations of Finnish and Finnish American culture to fit contemporary contexts. Excerpt 19 captures the essence of this study’s discussion section by highlighting the resilience of Finnish Americans in preserving their heritage amidst changing circumstances. The speaker recalled the possibility of cultural events being the “last time” 50 years ago. Despite this perception, they defiantly rejected the notion of Finnish culture fading away. Instead, they cited instances where attempts to suppress it have been overcome, expressing confidence in its enduring strength.

- Excerpt 19—UP

“In my years living here, people would often say, ‘well, it’s almost over’. I responded, ‘I don’t accept that anymore’, because I’ve seen them try to put the lid on the coffin many times. I remember when I was 16, there was a Juhannus12 dance in Bruce Crossing at the baseball field with outdoor dancing. I attended, and eventually, I went home. As I walked up the steps near the landing at the top, I thought I’d better stand here and listen to this for a while; this might be the last time. That was in 1973. I thought that this was the last gasp, and many times they have tried to put the lid on the coffin, but sisu pushes it off”.(D)

5. Conclusions

This study revealed a diverse range of language attitudes and ideologies prevalent in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and Northern Minnesota, as observed through interviews and material ethnography. Among these, nationalistic and purist ideologies emerged prominently, influencing the perception of Finnishness within these communities. These ideologies were articulated both verbally, through discourse and conversation, and symbolically, through material culture. For instance, items like mugs inscribed with phrases like “I’m silently correcting your pronunciation of sauna” reflected a purist attitude, while sentiments expressed in interviews such as “you know what I’d be if I wasn’t Finnish… ashamed!” illustrated nationalistic perspectives. These findings contribute to the understanding of how language attitudes shape the construction of an authentic Finnish identity within these communities.

Furthermore, the apprehension regarding the future of Finnish heritage in historically Finnish regions seems justified, given the recent losses such as the closure of Finlandia University and Kaleva Café in Hancock, Michigan. However, this study suggests that present generations are embracing Finnishness in novel ways, albeit possibly diverging from the expectations of older generations. The emergence of new establishments where Finnish Americans and locals, regardless of Finnish heritage, innovate and create something unique implies an evolving cultural identity rather than its loss. An openness to new interpretations and expressions of Finnishness signifies a positive shift in the community’s attitude toward cultural preservation and adaptation. Future research could expand to include other historically Finnish areas such as the Finnish Triangle in Minnesota and Thunder Bay, Canada. This broader scope would provide insights into how Finnishness is perceived on a larger scale, allowing for comparison, particularly in areas where Finnish identity is not sustained by national organizations, such as the Finlandia Foundation National in Hancock and the 5-year commitment of FinnFest to Duluth.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Finlandia Foundation National and the Finlandia Foundation National New York Chapter. Open access funding provided by University of Helsinki.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research adheres to the guidelines of the University of Helsinki in Finland, which are in alignment with the principles outlined by TENK (The Finnish National Board on Research Integrity) and governed by the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation). Compliance with these guidelines ensured the ethical conduct and protection of data in the research process.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all interviewees involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected in this study are not publicly available. The reason for this is that I informed interviewees through the consent form that their audio or video files and transcripts of the interviews (either in part or in full) would not be published without their explicit consent and knowledge.

Acknowledgments