Abstract

This study explores the extent to which Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals, a population that is said to have a residual high tone of African origin, keep their two languages temporally and intonationally distinct across statements. While creole languages that emerged from the contact of African and European languages, such as Palenquero, may develop hybrid prosodic systems with tones from substrate languages, and stress from the majority language, language-specific prosody might be expected to converge or simplify over the course of time. As prosodic convergence seems to be inescapable under Palenquero’s circumstances, which factors could support language-specific prosody in this population, if there are any? Two-hundred and thirty-four five-syllable statements were elicited through a discourse completion task, with the participation of ten Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals, in two unilingual sessions. Both phrase-final lengthening and F0 contours were assessed using linear mixed-effects models testing their association with final stress, language, and generation. F0 contours were dimensionally reduced using functional principal component analysis. Despite the strong similarities between the two languages, results indicate that both groups keep their two languages intonationally distinct using plateau-shaped contours in Palenquero initial rises followed by steeper declinations in Spanish. However, elderly bilinguals implement penultimate lengthening language-specifically, being more pronounced in Palenquero. Adults, in contrast, do not show this distinction. In addition to this, elderly speakers show hyperarticulation in Spanish intonation, increasing the difference between their languages. This leads us to believe that adults exhibit a more simplified prosodic system between their languages, relative to elderly bilinguals. In spite of such differences, both generations seem to have the same underlying process (perhaps a substrate effect) driving plateau-shaped intonation in Palenquero, which enhances language differentiation.

1. Introduction

Even though bilingual speakers may acquire or develop phonological categories that are language-specific, these categories do not appear to be autonomous as languages somehow influence one another (Barlow 2014; Deuchar and Clark 1996; Flege and Eefting 1987; Paradis 2001). In a language contact situation, speakers may become bilingual (Appel and Muysken 2005; Montrul 2008), and despite that the majority language could have more effects on the minority language, both languages would—to some extent—influence each other in the mind of proficient bilinguals. Prosody, the music of language, is not immune to cross-linguistic interactions, opening a new avenue for bilingual research in language contact scenarios.

Prosody involves phenomena such as tone, stress, intonation, phonological phrasing, or temporal limits (Arvaniti 2022; Beckman and Venditti 2011; Fujisaki 1997; Ladd 2008; Shengli 2019). Given that bilingual speakers exhibit cross-linguistic interactions showing transfer, interference, simplification, and convergence of forms and meanings (Grosjean 2008; Gutiérrez 1994), bilingual prosody also entails any of these cross-linguistic interactions (see Bullock and Toribio 2004). In addition to this, we have become increasingly aware of the vulnerability of prosody to bilingualism and language contact situations. In fact, bilingual speakers may be less exposed to one language input due to the strong influence of a majority language, accelerating prosodic convergence or simplification (Bullock 2009; Stefanich and Cabrelli 2020). Last but not least, prosody is inherently variable, as it is deployed to carry information about constituent and rhythmic structure (i.e., temporal limits), semantic and pragmatic meaning, and emotional content (Dupoux et al. 2008, p. 3). For these reasons, showing how prosodic information is represented at the phonological level, and produced at the phonetic level, in bilingual speakers of contact-induced languages poses major challenges. Nevertheless, knowing to what extent these bilingual speakers maintain their languages prosodically distinct could be a good starting point in order to better understand bilingual prosody in language contact scenarios.

Bilingual speakers of creole languages that developed from the contact of African and European languages, as in the case of Papiamento (Kouwenberg and Muysken 1994), Saramaccan (Bakker et al. 1994), or Palenquero (Hualde 2006; Hualde and Schwegler 2008), have shown a tendency towards prosodic merge or converge as they may also develop hybrid prosodic systems with (residual) tones from substrate African languages, and stress from source (or lexifier) European languages (see Gooden et al. 2009). Thus, prosodic convergence appears to be inescapable when language contact with the majority language is consistent and intense, as Bullock and Gerfen (2004) have argued. We do not know however what factors may counterbalance prosodic convergence, and could therefore explain language-specific prosody in these bilinguals. In fact, it is unclear whether bilingual speakers of creole languages could really keep their two languages, i.e., the creole and European languages, prosodically distinct. What is more, if this were possible, we would not have a clear understanding of how many generations could preserve language-specific intonation, or those temporal limits (i.e., rhythmic structures) that are used by these bilinguals in a language-specific fashion. One of the main motivations for asking a question of this sort is to explore what factors and conditions contribute to maintaining language-specific prosody in bilingual speakers of creole languages.

This paper reports on the effects of final stress, language, and generation on both phrase-final lengthening and intonation, in Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals. The aim of this study is to know, in the first place, whether these speakers maintain their two languages prosodically distinct when producing statements, and thus understand better which underlying processes might have contributed to language-specific prosody, and which ones could be indicative of prosodic simplification or convergence. In order to operationalize these concepts, two research questions are addressed in this paper:

- Do bilingual Palenquero/Spanish speakers use phrase-final lengthening in statements language-specifically? If that was the case, how final stress, language, and generation condition language distinctions from phrase-final lengthening production?

- Do these bilinguals keep their two languages intonationally distinct in statements? If language-specific intonation is attested, what is the contribution of final stress and generation to the bilingual production of statement intonation in these speakers?

Palenquero is a creole language that has developed in San Basilio de Palenque, Colombia (South America), from the contact of African people with Spanish conquerors during the times of slavery and abduction in African lands. The most salient prosody of Palenquero creole was described as a type of phrase-final “cadence” (Friedemann and Patiño-Roselli 1983; Montes 1962), correlated acoustically with a falling pitch and a lengthening effect, stretched from the penultimate syllable until the end of the statement (Hualde 2006; Hualde and Schwegler 2008). In addition to this, it has been shown that statement intonation, in Palenquero, tends to be flat or, at least, exhibits plateau-shaped contours in most cases, and also that penultimate lengthening is ostensibly more frequent in Palenquero than Spanish (Correa 2017). On the other hand, Spanish broad-focus statements are typically realized with a steeper rise whose peak is reached later in prenuclear intonation (i.e., non-final intonation). This rise tends to be followed by a declination whereby statements describe a falling intonation for the most part of the utterance (see Beckman et al. 2002; Hualde and Prieto 2015). Therefore, flat or plateau-shaped contours do not seem to be frequent throughout unmarked statements in more Spanish dialects.

The social conditions under which adult and elderly bilinguals have acquired both Palenquero and Spanish relate to some differences in their particular ecological contexts (for linguistic ecology perspectives, see Gooden 2022; Mufwene 1996, 2001; Steien and Yakpo 2020). Elderly speakers have experienced discrimination, marginalization, and exclusion more severely than adult speakers in the current ecological context. This may be evidenced by Patiño-Roselli (1983), who found that Palenquero speakers, in the early 1980s, avoided the use of the creole, and did not want their children to speak Palenquero due to the stigma associated with its use. However, most elderly bilinguals are illiterate, as they have not received formal instruction in Spanish, but nowadays are the most fluent Palenquero speakers. Even though adult bilinguals were led away from Palenquero in their childhood, they were also part of the first cohort of students in the revival program for the Palenquero creole that started in the 1990s (Morton 2005). This implies that, as well as having learned the creole at home with their parents and grandparents, adult bilinguals have also learned Palenquero in public school while being taught to read and write in Spanish.

In what follows, Section 1 will cover the prosodic characteristics of some creole languages, and how the context wherein these languages develop may determine a hybrid status for their prosody. This section also offers a brief overview of bilingual prosody, and describes prosodic patterns that have been shown so far for Caribbean Spanish varieties and Palenquero creole, especially with regard to phrase-final lengthening and intonation. Then, Section 2 will describe the background and language proficiency of the bilingual participants, and present the production task used in this study, as well as the corpus, and the statistical analyses performed. The functional principal component analysis used for F0 contours is explained and visualized in this section. On the other hand, Section 3 will illustrate results on penultimate lengthening and intonation from both adult and elderly bilinguals, while Section 4 and Section 5 will discuss and conclude how convergence, simplification, hyperarticulation, final stress, and language-specific intonation could disclose a particular perspective to understand statement prosody in Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals.

1.1. Prosody in Creole Languages

Creoles are languages that arise from “intense language contact situations between groups of people with no language in common, but a common need for communication” (Holm 2000). For instance, creoles that have developed in plantations, also throughout the period of slavery in the Americas, have emerged from the contact of European and African languages. Broadly speaking, African speakers have initially borrowed lexical items from the given European language, and have inserted them into the morpho-syntactic structure of their original African language. The resultant language (i.e., the pidgin) was then the first language for subsequent generations, who have theoretically made use of their innate linguistic capacities to transform it into a full-fledged language, being at this particular point a creole language (cf. Bioprogram Theory, and the Founder Principle in Creole Genesis in Mufwene 1996; Muysken and Smith 1994, respectively). Creole speakers used the European language to communicate outside their local community, whereas the creole is solely used within the community, being unintelligible to monolingual speakers of the European language. For that reason, African descendants in the Americas were raised in bilingual contexts, where speakers use a creole language demoted to be for informal contexts, and a dominant European language promoted to be used in more formal settings (Mufwene 1996; Rickford 1980; Thomason and Kaufman 1988).

Empirical evidence seems to indicate that creole speakers with tonal substrates from West African languages reinterpreted stress from the European language with the surface form of an African H tone (e.g., Adamson and Smith 1994; Bakker et al. 1994; Hualde 2006; Hualde and Schwegler 2008; Kouwenberg and Muysken 1994). Thus, they exhibit a H tone on primary-stressed syllables in the creole even when tones do not contrast paradigmatically (i.e., when there are no minimal pairs differing solely on the basis of tone), just as speakers from Bantu languages did with words borrowed from French and Portuguese (cf. Kikongo language in Samba 1989). In Saramaccan, for instance, European-derived words exhibit a H tone in primary-stressed syllables (Bakker et al. 1994, p. 170); in Papiamento, H and L tones correspond respectively to stressed and unstressed syllables (Kouwenberg and Muysken 1994, p. 208), and in Sranan, a double accent phenomenon is correlated with double length, and a H tone is used in intensive constructions and onomatopoeia (Adamson and Smith 1994, p. 221). In addition to this, it has been shown that creoles may also associate H tones with non-stressed syllables, such as Fa d’Ambu creole, whose long vowels, being stressed or not, show a high rise tone (LH), and the following syllable is always pronounced with a H tone (Post 1994, p. 194).

Even though bilingual speakers of creole languages may develop hybrid prosodic systems (Gooden et al. 2009), telling apart those patterns that are influenced by tonal substrate languages from those that are intonational is not as straightforward as it might seem. This is because some patterns can be found in both tonal and intonational languages. The phrasal phonology of Saramaccan, for instance, exhibits high-tone plateauing, wherein two H tone syllables can flank syllables unspecified for tone, as in (1a) and (1b) (Good 2004, p. 598).

| (1) | a. | dí foló bɛ́ —> dí fóló bɛ́ |

| the flower red | ||

| ‘The flower is red.’ (Taken from Good 2004) | ||

| b. | dí wajamáka=dɛ́ á óbo —> dí wájámáká=dɛ́á óbò | |

| the iguana=there have egg | ||

| ‘The iguana has eggs.’ (Taken from Good 2004) |

However, Papago language—known as Tohono O’odham—a North American language spoken in Southern Arizona and Mexico, also exhibits high-tone plateauing, given that speakers associate a H accent to each stressed vowel, and to all vowels in between (Hale and Selkirk 1987, p. 152). This is illustrated in (2) with the words wákial ‘cowboy’, and wísilo ‘calf’. The final result would be very similar to what has been observed in Saramaccan. Despite that, Papago has been described as an intonational language, and there is no evidence for tonal remnants in this language (Hale and Selkirk 1987).

| (2) | na-t g wákial g wísilo cépos? —> |

| Inter-Aux.3sg.Perf Art cowboy Art calf brand.Perf | |

| na-t g wákíál g wísíló cépos? | |

| ‘Did the cowboy brand the calf?’ (Taken from Hale and Selkirk 1987) |

1.2. Creole Speakers as Agents of a Minority Language, and a Majority Language

As speakers of creole languages are in close contact with a majority language, prosodic outcomes may be driven by phonological loans, transfer, interference, convergence, or simplification (see Matras 2009; Thomason and Kaufman 1988; van Coetsem 1988). This implies that either language, i.e., the African or the European language, can provide the creole with prosodic features (Yakpo 2021). This is the reason why van Coetsem (1988) used the term “agentivity” to explain how language contact determines phonological features in contact-induced language. From this perspective, there are phonological loans that entail the partial or total reproduction of phonological material from a source language into a recipient language, including its form (matter in Matras 2009) and structure (pattern in Matras 2009). This is triggered by the relative “agentivity” of speakers’ languages, given that they behave as agents of either the source language or the recipient language (van Coetsem 1988, pp. 7–12). In other words, agentivity is therefore determined by the relative activation of speakers’ languages. Two critical processes are then explained from this perspective: Impositions (previously referred to as interference, see Thomason and Kaufman 1988), and borrowings. These terms can be more readily understood when observed in succession, as with a shift in language dominance between two generations of speakers who have come into contact with a majority language. As shown below, a topical subject such as the immigration phenomenon provides the context to better understand “agentivity”, given that language contact and bilingualism are, most of the time, driven by immigration.

The following examples were adapted from van Coetsem (1988, pp. 88–89) who showed that, when the speaker’s recipient language is more active, recipient language agentivity is in effect. Therefore, speakers would borrow forms from the non-native source language, and adapt those to the native recipient language phonology. For example, a first generation of Dutch immigrants in an English-speaking country borrowed English words while speaking Dutch, because the social context required them to speak English. Dutch is then the recipient language for the borrowings coming from English, which is the source language. English borrowings are thus adapted to Dutch phonology. On the other hand, source language agentivity connotes more activation of the speaker’s source language, as they impose its grammar and phonotactics on the form being reproduced in the recipient language. To continue with the generational transition for the above example, and see the succession for the two types of agentivity, the Dutch immigrants then had children who acquired L1 proficiency in English, and have also acquired Dutch from their parents as a heritage language. They are, in practical terms, bilingual speakers. When Dutch/English children speak Dutch with their parents, they may include English functional words, for example, the English preposition ‘at’ instead of Dutch ‘naar’. In this case, these bilinguals are applying source language agentivity. Within this type of interference, it is expected that those English forms used while speaking Dutch follow English phonotactics. They may be considered, therefore, as impositions from the native source language features on Dutch, which is the recipient language. It is worth reminding ourselves that these effects could entail more issues and greater complexities when it comes to explaining prosodic loans, transfer, interference, and simplification.

Consequently, source or lexifier languages have a vast impact on creoles, given that this latter is commonly the minority language. In the main, bilingual speakers tend to “impose” the source language prosody upon the recipient language, which is a linguistic behavior that in most cases leads to intonational convergence or simplification. Thus, when prosodic patterns from a majority language are “imposed” on the minority or speakers’ non-dominant language, source language agentivity is applied. Despite that, the minority or non-dominant language may also permeate the majority or dominant language prosody, in which case recipient language agentivity would be applied. Thomason and Kaufman (1988) consider this as substratum interference, being a subtype of interference that usually results from imperfect group learning during the process of language shift (p. 38). In general, bilingual speakers show transfer, interference, convergence, and other processes such as simplification, overgeneralization, or hyperarticulation of prosodic patterns. This is why cross-linguistic interactions are a constant stream of variation, and may be hiding a more general trend towards intonational simplification or convergence (Bullock and Toribio 2004; Gutiérrez 1994).

1.3. Prosodic Convergence in Bilingualism and Language Contact

It has become evident that, at least for segmental and prosodic information, some structures of bilinguals’ languages are somehow inclined to merge. Interference, transfer, or simplification are processes that make bilinguals’ languages less distinct or structurally more alike, a characteristic that has also been used to describe convergence. In bilingual studies, convergence has been defined as a process whereby “bilinguals’ languages become uniform with respect to a property that was initially merely similar” (Bullock and Toribio 2004, p. 91). For instance, Spanish-English bilinguals have shown a degree of convergence for voice onset time (VOT) in code-switched productions. That is, when switching from Spanish to English, the English VOT values were more Spanish-like, and when switching from English to Spanish, the Spanish VOT values were more English-like (Olson 2012). In addition to convergence, code-switched tokens may show hyperarticulation correlating with longer duration and higher pitch, when communicative constraints are at a higher level (see Hyper- and Hypo-articulation Theory in Lindblom 1990, cited in (Olson 2012)). Another case of convergence was reported in bilingual French-English speakers, living in Frenchville, Pennsylvania. These bilinguals have replaced the mid-front round French vowels [ø] and [œ] with the English rhoticized schwa [ɚ]. According to Bullock and Gerfen (2004), cross-language acoustic and perceptual similarity among these vowels makes them phonetically unstable, being this the reason why phonological convergence took place. However, they do not rule out the possibility that language contact with English could, at some point, have motivated this change. In any case, as the particular direction of change is opaque, the authors ascribe the merger primarily to the phonetic instability in the vowels because of their similarity (Bullock and Gerfen 2004, p. 103).

Convergence is a technical term widely used also in language contact studies. It is defined as a process by which two languages in contact change to become structurally more alike, assuming they were different at the onset of contact (Aalberse and Muysken 2019; Silva-Corvalán 1990; Thomason 2001). Thomason (2001) gave a wide definition for convergence claiming that, in a contact situation, languages converge in ways that make them more similar, but cross-language interference can be mutual, and not necessarily unidirectional. This holds true especially when neither the source nor the recipient language has the resulting feature, or when the direction of areal features is often impossible to determine (pp. 89–90). Bullock and Toribio (2004), presenting convergence as an emergent feature in bilingual studies, do not differ much from this perspective, since their definition does not give special relevance to the direction of influence between the languages in contact (p. 91). Furthermore, Silva-Corvalán (1990)’s definition is also stark and critical given that, in addition to resulting from transfer, convergence may occur due to internally motivated changes in one language, being most likely accelerated by contact, rather than transferred from one language to the other (p. 164). This implies that convergence not only results from transfer, but also from language internal processes such as simplification or overgeneralization.

Simplification is defined as the expansion of a given form to a larger number of contexts, at the expense of a different form that was in competition with the given form. That is, simplification involves the contraction of a different form which is used less frequently (Silva-Corvalán 1990). This concept might overlap with overgeneralization as the latter also describes the extensive use of a given form. Nevertheless, this would affect contexts where no competing form exists (Silva-Corvalán 1990). Prosodic systems in some creole languages and Afro-Spanish varieties have been analyzed as simple or reduced, showing apparently a degree of structural simplification (see Correa 2017; Sessarego and Rao 2016). It seems to be more convenient when we do not know whether substrate or source language effects could provide a sense of directionality in order to explain the current (or resulting) features. However, Alvord (2006) and Colantoni (2011) warn that prosodic patterns in contact-induced languages could be the result of transfer from one language rather than a language-internal simplification. Convergence is therefore a critical concept to this analysis, and seems to be in line with simplification, since creole languages undergo regular typological change and areal convergence with European source languages. These processes are not specific to creoles, but are part of the adaptation to their linguistic ecology (Yakpo 2021).

As prosodic studies with bilingual speakers following a language contact framework are relatively recent (e.g., Bullock 2009; Colantoni and Gurlekian 2004; Elordieta 2003; Elordieta and Irurtzun 2016; O’Rourke 2005; Queen 2006; Rodríguez-Vázquez 2019; Simonet 2011, among others), both bilingual and language contact studies are starting to have meeting points, at least with reference to prosody. Simonet (2011), for example, mentioned that bilingual speakers may show two types of convergence: Symmetrical and asymmetrical convergence. The latter would explain prosodic changes in which the two languages become more similar because one language is adopting the features of the other language, accounting for one-way directionality, either from the majority language to the minority language, or vice versa. Symmetrical convergence, on the other hand, should explain prosodic changes where the two languages are more alike by developing shared features (Simonet 2011, p. 158). However, it remains unclear what the scope and impact of symmetrical convergence might be, and whether this always depends on the prosodic influence that languages at play exert against each other.

Prosodic studies with bilingual participants whose languages are in intense contact allow us to see a little closer how symmetrical convergence may occur in bilingual prosody. For instance, young Turkish/German bilinguals, being Turkish heritage speakers, use short rises typically found in monolingual Turkish speakers, as a way to prosodically highlight the main point of narratives in nuclear position (i.e., phrase-final position). They also use German steeper rises which are produced by monolingual speakers for pragmatically more salient information in nuclear position. These young girls kept both short and steeper rises as contrastive, despite that the functions were similar and that the German language was the majority language, and could have therefore exerted a stronger influence on Turkish short rises. Queen (2006) showed that the two rises were contrastive to one another, and also to nuclear contours with falling or flat intonation, but were equally used in both Turkish and German. That is to say, they were no longer used language-specifically. These patterns were thus “fused” rather than mixed, given that the two rises went from being contrastive in two separate intonational grammars to being contrastive in one single intonational grammar that has resulted from “fusion” (Queen 2006, p. 175).

Bullock (2009), on the other hand, has interviewed the last two English/French bilinguals, who were French heritage speakers living in Frenchville, Pennsylvania. At the time of the study, they were about seventy years old, and were also English-dominant. She found that these speakers use pitch accents and tonal contours that have not been reported in any other French variety. They produced a penultimate prominence that was very similar—albeit not identical—to their English intonation. However, penultimate prominence in Frenchville French is not attributed to English influence, as it also resembles the secondary or emphatic accent from regional varieties of French. It is worth noting that these bilinguals no longer had contact with French. The study suggests therefore that speakers were innovators, but the contact with English intonation has enhanced the development of penultimate prominence as well because it is also similar (i.e., congruent) with English. In other words, penultimate prominence in Frenchville French is an innovation that could have resulted from both a language-internal mechanism for prosodic change in French, and from the influence of English intonation. Unfortunately, the report did not confirm whether penultimate prominence was still language-specific, yet all of them, penultimate prominence, focus via prominence in situ, and the prosody of left dislocation seem to be convergent with English, i.e., the speakers’ dominant language (Bullock 2009). Despite that, it does not appear to be an indisputable case of asymmetrical convergence.

This type of convergence, albeit driven by Italian, the native and recipient language of one of the most representative groups of people who have migrated to Argentina, might explain why Spanish intonation in Buenos Aires is distinguished from other Spanish varieties. In this dialect, early alignment of F0 peaks occurs in prenuclear position (i.e., non-final), and a pronounced pitch drop is observed in statement-final position (Fontanella de Weinberg 1966, 1980; Kaisse 2001; Malmberg 1950; Sosa 1999). That is, the former describes intonational rises whose peaks are reached within the boundaries of the stressed syllable in prenuclear position (i.e., non-final position), which is represented as H* or L+H* within the AM model for Spanish, in contrast to late alignment (represented as L+<H*, see Section 1.4.2). The latter refers to a more pronounced fall, in phrase-final position. It has been shown that prenuclear intonation in Spanish varieties exhibits late alignment (see Face 2001; Hualde 2000; Hualde and Prieto 2015; Sosa 1991, among others), it is therefore widely accepted as a common feature in Spanish intonation. However, some Spanish varieties in a situation of language contact, on the contrary, show early alignment, as is the case for Peruvian Spanish in contact with Quechua (O’Rourke 2012), or Lekeito Spanish in the Basque Country in Northern Spain (Elordieta 2003; Elordieta and Irurtzun 2016). In Colantoni and Gurlekian (2004)’ study, Spanish speakers showed early alignment to prosodically mark narrow focus, which is why they did not ascribe early-aligned peaks in prenuclear intonation to language contact. Nevertheless, they did connect the more pronounced fall occurring in phrase-final position of statements to both direct and indirect language contact from Lunfardo slang and Italian language, as both show falling contours (HL) downstepping pitch accents in phrase-final position. In Colantoni and Gurlekian (2004)’s words, it is plausible to assume that there were both active and passive Italian/Spanish bilinguals, and it is also reasonable to consider that monolingual Spanish speakers probably imitated the speech of Italian immigrants (p. 115). Recipient language agentivity could in both prospects explain why intonation in Buenos Aires Spanish differs from other Spanish varieties, supporting the language contact hypothesis.

In addition to this, O’Rourke (2012) found an interesting trend for contrastive and broad-focus marking in Peruvian Spanish. Prosodic distinctions, in terms of pitch height and alignment, were less contrastive in the two conditions, as the experiment moved from native Spanish speakers to Quechua/Spanish bilinguals, to native Quechua speakers (p. 508). These findings indicate that alignment is not distinct, and lower peaks are used in both contrastive and broad-focus conditions mainly by native Quechua participants in Cuzco, while, at the other end, monolingual Spanish speakers, most of them living in Lima, showed focus marking patterns similar to those found in Peninsular Spanish. It is not clear, however, how intonation contributes to focus marking in Quechua, given that empirical evidence is sparse. O’Rourke (2005) studied the prosody of Quechua evidential suffixes, including the suffix used to mark focus morphologically. She argued that speakers did not use peak height to distinguish evidential meanings in Quechua. On the other hand, Cole (1982, cited in (O’Rourke 2012)) studied Quechua from Imbaura, Ecuador, and found that non-final peaks under contrastive focus were higher than peaks in broad focus (pp. 210–11). O’Rourke suggests that native speakers of Quechua, as well as some Quechua/Spanish bilinguals, do not keep the two focus conditions prosodically distinct as a consequence of the influence of Quechua prosody. Nevertheless, it remains to be explored how Quechua intonation has influenced focus marking in Peruvian Spanish for these two groups, since the process is still opaque, and ruling out symmetrical convergence could be inaccurate at this point.

In view of the above, understanding how the direction of prosodic changes occurs from the majority to the minority language, or vice versa is not that simple. There appears to be no clarity or agreement on the way we assess prosodic changes that are influenced, at the same time, by both the majority and the minority languages, as well as on those patterns or “innovations” that have not been clearly outlined in any of the component languages at play, but are equally used in the two languages. Nevertheless, prosody from bilingual speakers of creole languages, such as Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals, is an understudied phenomenon that might help us understand how bilingual prosody evolves over time. Perhaps we do not have all the historical and statistical details to reconstruct the evolution of prosody, but we could start by asking whether bilingual speakers of creole languages can keep their two languages prosodically distinct, despite cross-linguistic interactions reflected through transfer, interference, and convergence. To this end, Section 1.4 will describe prosodic features found in Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals thus far, and what has been discovered about the past of this population, including their connection with African prosodies, and their contact with Caribbean Spanish intonation.

1.4. The Intonation of Palenquero and Caribbean Spanish

Palenquero is an Afro-Hispanic creole language spoken in San Basilio de Palenque, Colombia, South America, which developed in the XVII century, from the contact of African slaves brought to the current territory of Colombia by Spanish colonists (Navarrete 2008; Schwegler 2011b). The vitality of Palenquero appears to have remained stable until the 1970s, when monolingual speakers of Palenquero still coexisted with both active and passive bilinguals, and monolingual speakers of Spanish (see Lewis 1970). Since the early 1990s, Palenquero has been taught in the public school following a language revitalization program (see Morton 2005). Today, there are no monolingual speakers of Palenquero, and the elderly members of the community, those who have acquired the creole as their native language, are the most fluent speakers of Palenquero. They used the creole along with the local variety of Caribbean Spanish spoken in the village. Adult Palenquero speakers belong to a different generation, and indeed not all of them speak Palenquero. Some have acquired the creole as a heritage language and, at some point in the past, have attended Palenquero classes in the local school (Smith 2014). As mentioned earlier, Palenquero is unintelligible to Spanish monolingual speakers, whereas Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals switch languages depending on specific social contexts. Caribbean Spanish is used outside and inside the community, in more formal settings, while the creole is demoted to be informal, and for everyday transactions only within the community (Morton 2005). It is worth noting that despite the fact that Palenquero speakers have been in contact with Spanish for around four centuries, Palenquero is not undergoing a process of decreolization (Dussias et al. 2016; Lipski 2016; Schwegler 2001), which suggests that the language revival program is helping children hold onto their creole language and African cultural heritage.

Spanish is the source language or lexical donor language for Palenquero; thus, most Palenquero words are cognates from Spanish. Despite that, the creole contains lexical and morphological elements from Bantu origin (Hualde and Schwegler 2008), possibly coming from two dialects of Kikongo—Kiyombe and Civili—both of which would have been spoken by Bakongo communities (Moñino 2017; Noguera et al. 2014). Kikongo melodies have been explored previously (e.g., Bentley 1887; Butaye 1909; de Clercq 1907; Laman 1922; Lumwamu 1973; Marichelle 1902; Samba 1989). Laman (1922) found, for instance, that Kikongo words display a rhythmic accent, falling always at the penultimate syllable, which is also weakened when the final syllable is accented (Samba 1989, p. 22). As a result, the intonation of words was said to be flat when the root and the following syllables had the same pitch; it fell when the following syllables were lower than the root, and it rose when the final pitch was higher than the root (Samba 1989, p. 23). It is also interesting to note that French and Portuguese lexical borrowings in varieties of Kikongo were assigned a H tone by analogy in the most prominent vowel (Samba 1989) which, following the same logic, has also been posited for Palenquero, as a H tone surfaces stressed syllables in the creole (Correa 2017; Hualde and Schwegler 2008; Lipski 2010). For that reason, Palenquero prosody is said to be in an intermediate position between tone and stress (Hualde 2006), meaning that not only Kikongo dialects have contributed to current Palenquero melodies, but also Caribbean Spanish has influenced the shape of Palenquero prosody.

1.4.1. Phrase-Final Lengthening

Phrase-final lengthening is one of the dimensions that might help understand the extent to which Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals keep their two languages prosodically distinct. Although the final “cadence” of Palenquero was impressionistically described like this by Montes (1962) and Friedemann and Patiño-Roselli (1983), thanks to the development of speech technologies, this can now be acoustically associated with a sustained H tone followed by a falling pitch occurring in tandem with a lengthening effect which stretches from the penultimate syllable until the end of the utterance (Hualde and Schwegler 2008). Clearly of relevance to this study is the claim that Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals produce more penultimate lengthening in Palenquero than Spanish (Correa 2017, p. 264). While this phonological process has not been reported in Caribbean Spanish varieties, some Bantu languages exhibit a process of penultimate lengthening in phrase-final position (see Hyman 2013), which might be another pattern from African origin. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider that penultimate lengthening may potentially contribute to language-specific intonation in Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals.

It is interesting however that, even though lengthening at the rightmost edge of statements could point towards a more comprehensive understanding of the intonational grammar for Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals, the study of final lengthening and its contribution to language-specific prosody is still uncharted territory. This could stem from the fact that pitch contours are relatively well-known when they are implemented on iambs in statement-final position. In this specific context, Palenquero speakers have shown flat contours, which usually lead to the flattening of F0 declination, and the truncation of low boundary tones (L%) (Correa 2012; Hualde and Schwegler 2008). Lipski (2010) tested statements ending in combinations of two or more stressed syllables, and found that Palenquero speakers dissimilate consecutive H tones through upstep, having one H tone higher than the other, or downstep, having one H tone lower. He suggested that a possible locus for the Palenquero high tone (H) lies precisely in this position.

Prosodic convergence, as detailed in Section 1.3, may lead Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals to produce phrase-final lengthening equally in their two languages. However, if adult speakers used penultimate lengthening irrespective of language, and if elderly speakers made a language-specific use of it, at least we could surmise that a change in apparent time might actually be happening (see Labov 1972). Final lengthening, on the other hand, might not parallel penultimate lengthening, if this latter were language-specific. In general, both final and penultimate lengthening are analyzed separately, as has been shown in Shekgalagari (see Hyman and Monaka 2011). In that report, final lengthening was above penultimate lengthening and its subsequent implementation of L% tones. This implies that Shekgalagari speakers attach more importance to final lengthening than penultimate lengthening, despite that the latter is phonologically less marked. Furthermore, it has been attested that both penultimate and final lengthening might be blocked for use in utterances other than statements, as in Bantu languages like Tswana, Shekgalagari, Sesotho, or Kinande (Hyman 2013). However, it is unknown thus far whether the relation between penultimate and final lengthening goes beyond that of the implicational relation claiming that if final lengthening is met, then penultimate lengthening should be met as well, and not in the opposite order (see Hyman and Monaka 2011).

As a way to address these gaps in understanding the prosody of Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals, it is conjectured in this present study that, as penultimate and final lengthening seem to be partly independent of each other, language mode may not condition them in the same way. In other words, if penultimate lengthening is language-specific, this would not imply that final lengthening is also language-specific, whereby language effects might differ. Additionally, age effects were not bypassed or set aside here. Recall that adult and elderly bilinguals have acquired Palenquero and Spanish at home, and within the Palenquero community. Notwithstanding this, adults took part in the Palenquero revival process that began in the early 1990s. Hence, they have also learned Palenquero in school (Morton 2005), which suggests that concern about the preservation of Palenquero creole grew among the members of the community during that time, due probably to the increasing use of the local Caribbean Spanish. It is surmised therefore that if a prosodic change were occurring in “apparent time” (see Labov 1972), because of the intense contact with Caribbean Spanish, adults should not mirror the elderly's lengthening. In consequence, the standardization process of Palenquero in school could have been permeated by the high influence of Caribbean Spanish.

1.4.2. Statement Intonation

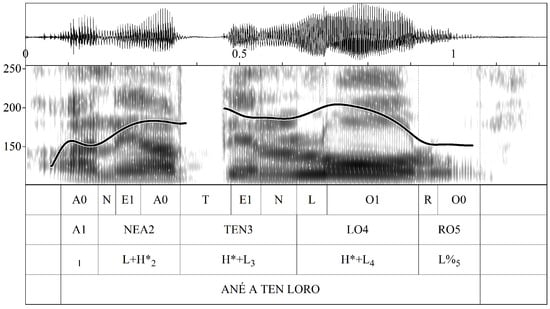

It has been suggested that flat or plateau-shaped intonation contours in Palenquero are linked to the reinterpretation of Spanish stress with a residual high tone (H) from two dialects of Kikongo language (see Correa 2012, 2017). The main implication of this claim is that these intonational outcomes could be envisaged as a result of H tones flanking unstressed syllables (or units underspecified for the residual H tone), which is, in other words, the definition used by Good (2004) to explain high-tone plateauing in Saramaccan. As mentioned above, the realization of L% tones is oftentimes truncated in Palenquero given the lack of F0 declination because of flat contours and, interestingly enough, due to iambic stress in phrase-final position (Correa 2017; Lipski 2010). Final stress would then serve as the right flank for flat contours, hence the interest in iambs when they occur in phrase-final position.

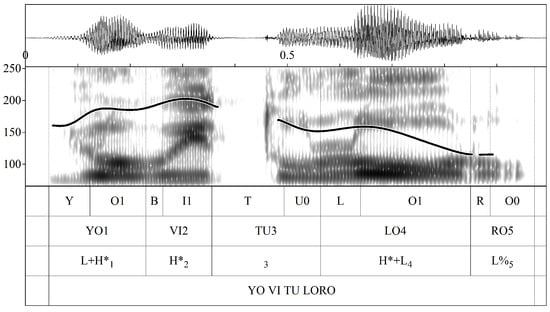

Even though statement intonation with flat or plateau-shaped contours has not been widely mentioned across Caribbean Spanish varieties, there is no evidence as yet that they are rare in this geographic region. Statement intonation in Spanish varies across dialects, but, overall, it describes a rising F0 in utterance-initial position (i.e., in prenuclear intonation), and once the rise reaches its peak, it is followed by a declination that falls until the end of the statement (see Figure 1a). Moreover, F0 peaks do not tend to be aligned within the boundaries of the stressed syllable in prenuclear intonation (Hualde and Prieto 2015). In other words, Spanish speakers produce F0 peaks that are reached after the stressed syllable in prenuclear intonation, which is why they are said to be late aligned or delayed relative to the accented syllable. The Autosegmental Metrical Model for Spanish (Beckman et al. 2002; Hualde and Prieto 2015) describes late alignment with the bitonal pitch accent L+<H*1, as can be found in the examples from Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Tunes found in Spanish statements (adapted from Hualde and Prieto 2015).

The stressed syllable is the first ‘be’ in Figure 1a,b. Recall that both of these examples correspond to the answer for the question ‘What does s/he do?’, and in either case, the first F0 peak is late aligned relative to the accented syllable (i.e., the first stressed syllable, in this case). On the other hand, nuclear intonation (i.e., final intonation) could present two possibilities: The first option is a smooth falling interpolation which spreads from the first F0 peak to the low boundary tone (L%), whose nuclear intonation has been annotated as L* L%, as illustrated in Figure 1a. The second option is a nuclear intonation showing a rising contour reaching a peak associated with the accented syllable (L+H*), and just before the L% tone, as Figure 1b demonstrates (examples taken from Hualde and Prieto 2015, p. 364). While changes in the pragmatic meanings have not been attested between these two nuclear possibilities, they appear to be an example of allotonic variation across Spanish intonation so far.

An iambic stress pattern in phrase-final position may prosodically motivate the production of flat contours in statements, resulting in phonological processes such as L% tone truncation. However, the linear association of flat intonation contours with L% tone truncation has not been extensively studied in Caribbean Spanish. One exception is the study done by Armstrong (2012), who noted that final rises or final plateaus in Puerto Rican Spanish yes/no questions tend to recur with increasing frequency when stressed syllables are in final position, whereby L% is said to be truncated. Cuban speakers also produce L% tone truncation in questions when the nuclear contour H* L% is anchored to an iambic syllable (Martín and Dorta 2018). Furthermore, L% tone truncation has been shown to be driven by iambic stress in phrase-final position of Canarian Spanish (Cabrera-Abreu and Vizcaíno-Ortega 2010), a variety that is historically connected to Caribbean Spanish. Other romance varieties such as Italian, Friulian, Moldavian Romanian, and Portuguese have shown L% tone truncation (Frota and Prieto 2015, p. 416), because of which, we will not be able to say that this outcome is alien to Caribbean Spanish intonation.

As languages with hybrid prosodic systems (i.e., tone and stress), like the Saramaccan creole (Good 2004), also exhibit this phonological pattern, it is therefore difficult, at this point, to attribute the occurrence of flat and plateau-shaped contours in Palenquero to the tonal remnants of a substrate African language, or to the intense contact with Caribbean Spanish. However, to understand better how these contours are used by these speakers, it is worth asking whether flat and plateau-shaped contours are equally likely to occur in both the Palenquero and Spanish of these bilinguals. Although there is not yet any definite evidence to answer this question, the few studies done in this regard seem to present incompatible perspectives. For instance, Correa (2012, 2017) argued that there were no substantial differences between the intonation of Palenquero and Caribbean Spanish statements across Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals. That report highlights that speakers use the same inventory of pitch accents and nuclear configurations in statements from both Palenquero and Spanish (Correa 2017, p. 263). However, later in time2, Lipski (2016) noted that Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals can disambiguate language in identification tasks by using the intonational grammar of Palenquero. In his study, when bilingual listeners heard Palenquero intonation in Spanish utterances, they ostensibly biased language identification in the direction of Palenquero (Lipski 2016, p. 53). If that were the case of Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals in the present study, then language-specific intonation should be expected in at least some specific contexts.

Finally, as previously conjectured for age effects on phrase-final lengthening results, the main difference in the acquisition of Palenquero between adult and elderly bilinguals is grounded in the fact that adult speakers, besides learning Palenquero at home and within the community, have learned the creole in school (Morton 2005; Schwegler 2011b). Therefore, adults have had a different experience with Palenquero given that, since the early 1980s, fluent creole speakers ceased transmitting Palenquero to children (Patiño-Roselli 1983). It is then appropriate to have control for age effects, and also test the conjecture that if an intonation change were occurring in apparent time (see Labov 1972), adult Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals should not mirror elderly bilinguals’ intonation. As a result, adults might show more intonational convergence between their two languages, probably due to the simplification of prosodic patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

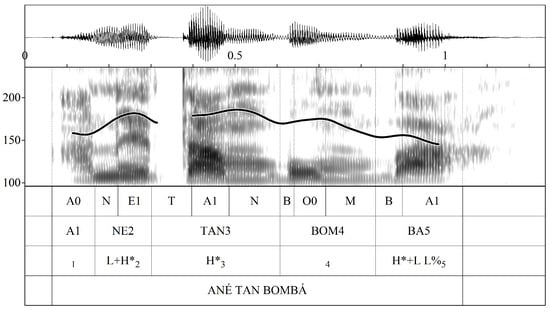

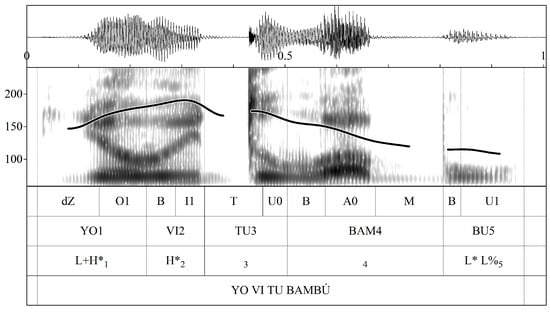

2.1. Production Task

The materials used in production tasks were designed to elicit semi-spontaneous statements. In order to more realistically reflect intonation variance across this sentence type in both Palenquero and Spanish, twelve near-minimal pairs were created aiming to explore the intonational contrast in statements from adult and elderly bilinguals. Minimal pairs were conveniently syllabified to have five units so that they were comparable and, at the same time, had a familiar ring to the participants in the production experiment. One sample from Palenquero creole is illustrated with the sentences in bold in (3) and (5), and their counterpart pairs in Spanish are shown with the sentences in bold in (4) and (6).

| (3) | Pal Nuno sabé nú si andi Balá ané a ten kaló nú. |

| Chitiá Nuno ke andi Balá ané a ten kaló. | |

| (Expected response: Nuno, andi Balá, ané a ten kaló.) | |

| ‘Nuno does not know if in Bala’s house they are hot. | |

| Tell Nuno that, in Bala’s house, they are hot.’ | |

| (Expected response: ‘Nuno, in Bala’s house, they are hot.’) |

| (4) | Spa A Nuno le gusta escuchar música de Kalé. |

| Dile a Nuno que donde Balá tú oíste su Kale. | |

| (Expected response: Nuno, donde Balá, yo oí tu Kalé.) | |

| ‘Nuno likes listening to Kale’s music. | |

| Tell Nuno that, in Balá’s house, you listened to his Kale.’ | |

| (Expected response: ‘Nuno, in Balá’s house, I listened to your Kalé.’) |

| (5) | Pal Nuno sabé nú si andi Balá ané a ten kalo nú. |

| Chitiá Nuno ke andi Balá ané a ten kalo. | |

| (Expected response: Nuno, andi Balá, ané a ten kalo.) | |

| ‘Nuno does not know if in Bala’s house they have soup. | |

| Tell Nuno that, in Bala’s house, they have soup.’ | |

| (Expected response: ‘Nuno, in Bala’s house, they have soup.’) |

| (6) | Spa Nuno no sabe dónde dejó su palo. |

| Dile a Nuno que donde Balá tú viste su palo. | |

| (Expected response: Nuno, donde Balá, yo vi tu palo.) | |

| ‘Nuno does not know where he left his stick. | |

| Tell Nuno that, in Balá’s house, you saw his stick.’ | |

| (Expected response: ‘Nuno, in Balá’s house, I saw your stick.’) |

As might have been inferred from the target sentences in (3)–(6), minimal pairs were designed with the aim of controlling for final stress effects on phrase-final lengthening, and also on intonation contours. Hence, the items in (3) and (4) end with iambic stress, whereas the items in (5) and (6) end with trochaic stress. This approach would allow us to see more clearly final stress effects, as it comprises two-syllable words which are near-minimal pairs varying their prosody from stress position. To make the point, the final Pal word [ka.ˈlo] “heat”, in (3), contrasts within the same language (i.e., Palenquero) with Pal [ˈka.lo] “soup”, in (5). On the other hand, the final Spa word [ka.ˈle] “name of a well-known musician”, in (4), contrasts with Spa [ˈpa.lo] “stick”, in (6), within Spanish statements. Consequently, the two-syllable words in final position contrast within and between languages.

The sentences to be elicited were designed and prepared in collaboration with a community leader and a Palenquero teacher, following the grammar of Palenquero described in Morton (2005); Pérez-Tejedor (2004). Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals performed two discourse completion tasks (DCTs) adapted to the participants’ everyday life. A DCT is a questionnaire used to gather prosodic data based on semi-spontaneous speech acts while speakers complete a turn in a given dialogue Brown (2001); Kasper and Dahl (1991). In order to present short, simple, and intuitive situations, the DCT instructions have followed dialogue construction and the old versions of DCT formats (see Vanrell et al. 2018). DCT instructions were therefore initiated with a brief situational background, followed by one direction prompting the speaker to reply as in (3)–(6).

To move forward in line with the idea of providing these bilinguals with familiar contexts, the voice of a known interlocutor was recorded while giving examples and the specific instructions, similar to those shown in (3)–(6). It aims to facilitate listeners’ understanding so that they are able to complete their turn in the conversation more naturally and as spontaneously as possible. Utterances were collected in a sound-attenuated recording studio in San Basilio de Palenque using a ZOOM H4n voice recorder, at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz, with 16-bit amplitude resolution. Participants wore a head-mounted microphone. It should be noted that tasks were designed and presented on psycho.py Peirce (2007, 2009), all the speakers were then exposed to the same voice from the well-known interlocutor who is fluent in Palenquero.

2.2. Participants and Procedure

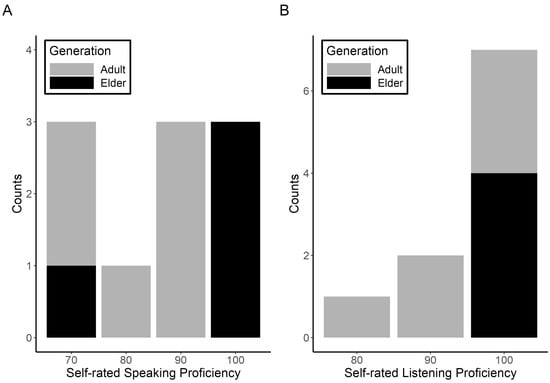

Ten participants (five of them female) were recruited for the production experiment with the help of Palenquero leaders and teachers who were familiar with their Palenquero proficiency. Speakers were divided into two different generations: Six adults (three of them female) (), and four elderly speakers (two of them female) (). Participants completed a linguistic background questionnaire in which they were asked about their place of birth, level of education, occupation, Palenquero acquisition age, and whether the creole was acquired at home, at school, or outside in the village streets. All participants were born in San Basilio de Palenque, and learned the creole at home and within the community. As expected, unlike adults, elderly speakers had a lower level of education, and did not have the need to study Palenquero at school. They are thus native speakers of Palenquero, who have acquired the creole both at home and while interacting with community members. All participants were asked about the origin of their parents and spouse, and also if they speak Palenquero with them. At the end, they provided a self-rated proficiency of Palenquero for both speaking and listening skills, which is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(A) Self-rated speaking proficiency in Palenquero. (B) Self-rated listening proficiency in Palenquero (N = 10).

Since bilingual speakers are more likely to inhibit cross-linguistic interactions in unilingual contexts (see Antoniou et al. 2011; Olson 2013; Simonet 2016), participants were recorded on two different days. Thus, the priming effects of the non-target language were controlled in this way. The first session was in Palenquero, whereas the second session was in Spanish, and took place around a week later. Participants were told that they were going to hear a short description of a situation, and they had to answer as the voice indicated. They were trained with one example at the beginning of each session. The task generally began once they had understood both the example and the expected response. In addition to this, they were able to move on at their own pace, by pressing the space bar to hear the next situation. Participants were asked to repeat the utterance only if the statement fell far short of the requirements for the expected response. In this way, the list effect on intonation driven by frequent repetitions was addressed.

2.3. Data Analysis

A total of 240 utterances were collected, but after removing outliers and influential points using Cook’s distance Cook (1977) and the car package in R Fox and Weisberg (2018), 231 statements were considered for phrase-final lengthening analysis, and 196 statements were deemed to be optimal for the intonation analyses. Phrase-final lengthening analysis, including both penultimate and final lengthening, required the automatic extraction of vowel length from penultimate and final syllables. Thus, penultimate and final lengthening effects were accounted for by the statistical analysis of vowel length. Measurements were normalized by the subject being log-transformed and scaled as z-scores in R, following Mücke et al. (2018). This is the main reason why results will be reported as units, which in practice are standard deviations (SDs). The regression equation that best described the linear association between vowel length with final stress, language, and generation, was found by conducting automatic forward and backward stepwise regressions, with the R function step Venables and Ripley (2002). In order to make regression results more readable and interpretable, predictors’ levels were dummy-coded to be zero or one. That is, final trochee, Palenquero, and adult were coded as zero (0), while final iamb, Spanish, and elderly were coded as one (1). Random effects of speakers’ variation on the intercept were accounted for by the linear mixed-effects model, for completeness.

The analysis of intonation contours was conducted using functional principal component analysis (FPCA) Ramsay and Silverman (2005); Ramsay et al. (2009) along with linear regression analyses. The former required an exhaustive data preparation and normalization of intonation contours. The entire process may be outlined in three major steps: Firstly, F0 contours were time-normalized by extracting ten F0 points per syllable, having fifty points per utterance. Then, F0 samples were automatically extracted at equidistant times on each syllable using ProsodyPro Xu (2013). Second, pitch ranges were normalized by subject, by transforming F0 points as log values and turning them into z-scores. This means that the mean for each subject’s range was zero. It is the reason why intonational differences represent, in practice, standard deviations (SDs). At this point, outliers and influential intonation points were manually transformed into NAs (not available). Third, FPCA was performed in order to reduce F0 dimensionality, and simultaneously obtain the most substantial modes of F0 variations (i.e., the functional principal components (FPCs)). The R-package fda Ramsay et al. (2009) was used to serve this purpose. The most substantial modes of F0 variation, resulting from FPCA, were analyzed incrementally from the first FPC through the one which, after being cumulatively added, covered approximately 80% of the total variance. It means that FPC2 was cumulatively added to FPC1, and then FPC3 to FPC2 and FPC1, and so on, until the cumulative addition of variances covered approximately 80% of the total variance. The linear equation to explain the mode of F0 variance contained in each FPC was found using forward and backward stepwise regressions, and model comparisons, in order to find predictors and interactions that best explain the relationship between each FPC with final stress, language, and generation. Backward and forward stepwise regressions were achieved with the R function step Venables and Ripley (2002). Random effects of speakers’ variation on the intercept of each FPC were accounted for by the linear mixed-effects models for completeness.

2.3.1. Functional Principal Component Analysis (FPCA)3

Intonation as a physical property is the modulation of vocal fold vibration; hence, intonational data are high dimensional, and involve much variation. However, FPCA helps understand how this variation occurs by revealing the most substantial modes of variation, and showing towards which intonational pattern F0 contours are trending. Variance is then partitioned into functional principal components (FPCs), and each FPC corresponds to one dimension that captures one portion of the whole variance. In a second step, linear regression analyses are performed in order to explain the variance accounted for by each FPC. That is, main, interaction, and random effects are tested to predict the variance contained in each FPC (see Asano et al. 2016; Aston et al. 2010). FPCA is a data-driven semi-automatic analysis used to understand the dominant or the most substantial modes of variation in functional data while projecting the variances as smoothed curves generated from the same data Asano et al. (2016); Ramsay et al. (2009). To the best of my knowledge, projecting FPCs onto eigenvectors as smoothed intonation contours is the only way the variance contained in one dimension may be visually understood. Each projected FPC could reveal different pitch contours, and, furthermore, when they are incrementally added, the total variance can be reconstructed.

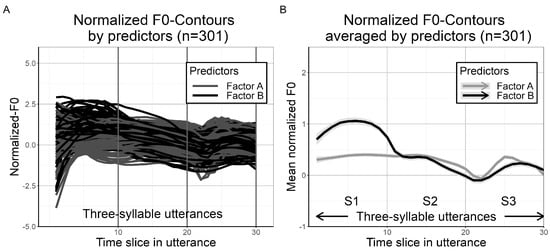

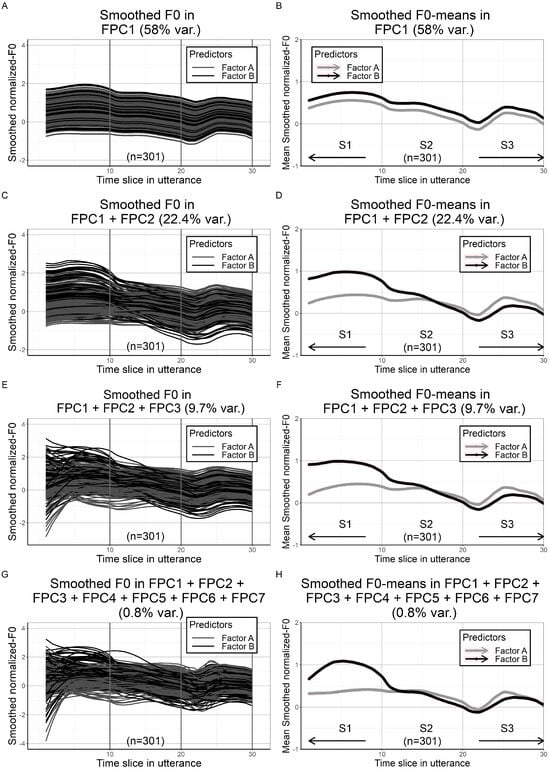

In order to illustrate this process, a sample dataset with 301 three-syllable contours, coming from two different predictors (Factor A and Factor B), is shown in Figure 3. It should be noted that the F0 contours presented in this section are by no means the actual contours studied in this paper. The FPCA performed in this illustrative dataset is visualized in Figure 4. Intonational data from Factors A and B are shown in Figure 3A, while averaged contours are presented in Figure 3B. FPCA helps find the most substantial modes of F0 variation, as illustrated in Figure 3A, so that we can visualize the average contours towards which actual contours are trending, and infer pitch accents whenever possible. Figure 4 shows the first three most substantial variances in these contours (see Figure 4A–F), as well as the entire reconstruction of intonation contours after having cumulatively added seven FPCs (see Figure 4G,H). Each FPC is one dimension of intonation contours, and is also the dependent variable for predictors, as presented in the following section.

Figure 3.

(A) Sample dataset with normalized three-syllable intonation contours from two groups. (B) Sample dataset averaged by Factor A and Factor B (n = 301).

Figure 4.

Reconstruction of the F0 contours, shown in Figure 3, by the incremental addition of FPCs, from FPC1 to FPC7. (A–D) represent the first two most substantial modes of F0 variation (i.e., FPC1 and FPC2) and, taken together, account for 80.4% of the total variance.

3. Results

This section shows the statistical analyses conducted, and the results obtained in order to answer, initially, whether Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals use phrase-final lengthening language-specifically across statements and, afterwards, whether the speakers maintain their two languages intonationally distinct in this sentence type. Given that penultimate lengthening is one of the most noticeable characteristics of Palenquero intonation (Friedemann and Patiño-Roselli 1983; Montes 1962), phrase-final lengthening analysis investigates how penultimate and final lengthening are implemented in both Palenquero and Spanish. Hence the interplay of final stress, language, and generation with each other is tested, aiming to understand its association with phrase-final lengthening. Palenquero intonation seems to differ from Spanish intonation among Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals, as flat or plateau-shaped contours have reportedly been more connected to the creole than to Spanish (Correa 2017). For that reason, the contribution of final stress and generation to language-specific intonation was also tested.

3.1. Phrase-Final Lengthening

Phrase-final lengthening results are presented below. I anticipate that they supported the claim that, overall, penultimate lengthening is much longer across elderly speakers than adults, being used language-specifically by the former. On the other hand, despite that final lengthening was significantly longer than penultimate lengthening, both adults and the elderly exhibit final lengthening to the same extent in their two languages. Therefore, there were no age effects on the way speakers implement final lengthening, and is not used language-specifically. In a nutshell, while adults produced penultimate lengthening in both Palenquero and Spanish, elderly speakers showed much longer vowels in Palenquero trochees, demonstrating that they implement penultimate lengthening in a language-specific fashion. Final lengthening, on the contrary, was equally likely in both Palenquero and Spanish. Let us examine these findings in more detail.

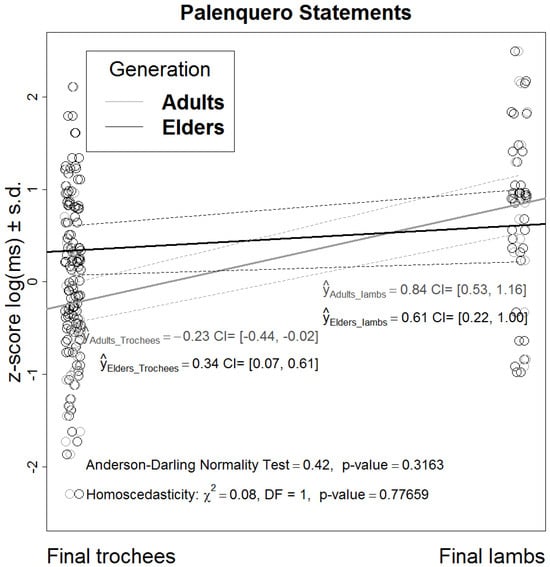

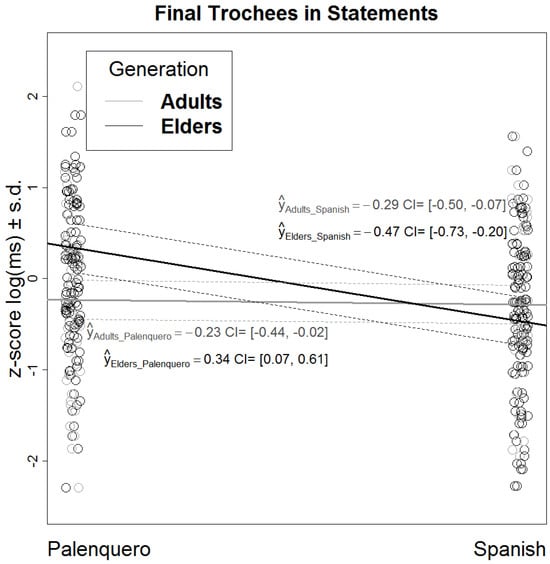

The predicted vowel length for penultimate syllables (i.e., from final trochees) in adult bilinguals was −0.23 (95% CI [−0.44, −0.02]), as can be found in Table 1. Adults increased vowel length at a rate of 1.07 units in stressed syllables of final iambs from Palenquero, which indicates that final lengthening is longer than penultimate lengthening in this generational group (see Adults in Figure 5). Nevertheless, adult speakers did not show language-specific differences for vowel length in the stressed syllable of final trochees (B = −0.05, 95% CI [−0.33, 0.22], p = 0.70; see Figure 6). Interestingly, elderly bilinguals increased vowel length at a rate of 0.57 units in Palenquero trochees, as compared to adult bilinguals (95% CI [0.23, 0.92], p = 0.01; see Figure 5).

Table 1.

Linear mixed-effects model for vowel duration in phrase-final position from statements (n = 231).

Figure 5.

Predicted vowel length for both final trochees and iambs by generation, in Palenquero statements.

Figure 6.

Predicted vowel length for both Palenquero and Spanish by generation, in final trochees.

This implies that, while final lengthening occurs in Palenquero regardless of age, the two generations differed in the phonetic implementation of penultimate lengthening. Elderly bilinguals showed therefore a more pronounced lengthening in Palenquero than adults (B = −0.80, 95% CI [−1.32, −0.28], p = 0.002). The Palenquero lengthening found across elderly speakers has a particularly relevant consequence for language-specific prosody in this group. Results show that elderly bilinguals produced final trochees in Spanish with a shorter lengthening relative to Palenquero, whereas adult speakers have produced penultimate lengthening equally in both Palenquero and Spanish, as shown in Figure 6. In other words, despite that adults use penultimate lengthening, this is not only less pronounced with respect to the elderly (B = 0.57, 95% CI [0.23, 0.92], p = 0.01), but also equally likely in their two languages (B = −0.05, 95% CI [−0.33, 0.22], p = 0.70).

3.2. Intonation Contours

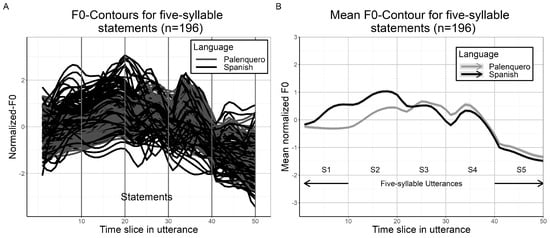

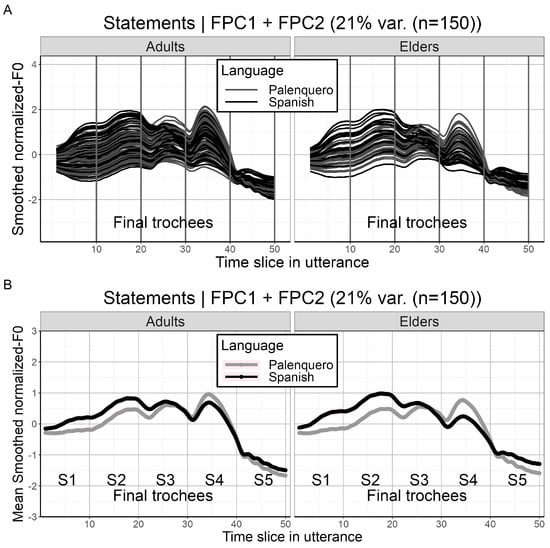

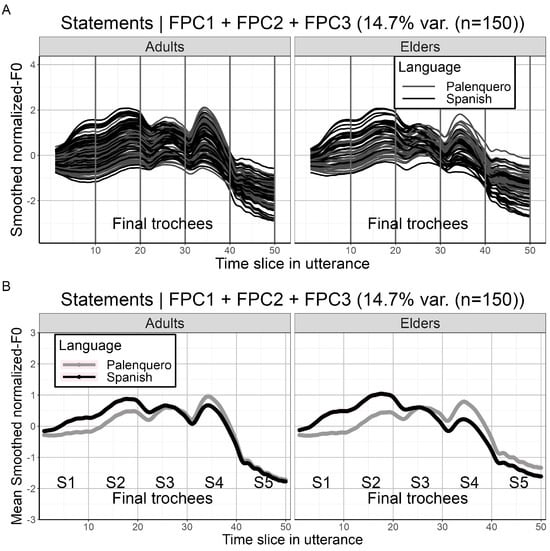

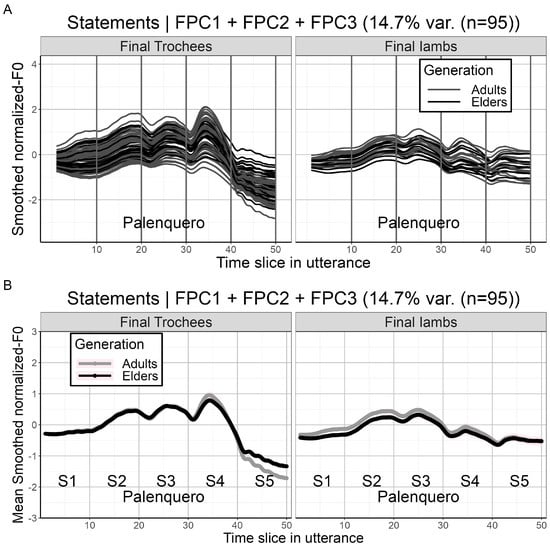

The aim of the present analysis is to resolve whether Palenquero/Spanish bilinguals exhibit language-specific intonation patterns across statements, and to determine the extent to which other prosodic factors, such as stress in phrase-final position, and sociolinguistic factors, like generation, intermediate. Figure 7A shows the intonation contours from both Palenquero and Spanish, after removing outliers and influential points, and after being normalized by the speaker (see Section 2.3). This Figure also offers a more general perspective on the actual intonation variation across statements. Figure 7B, in turn, presents the averaged contours depicting an initial high rise in Spanish statements, which is followed by a steeper declination. In Palenquero, statement intonation seems to describe a high plateau sustained throughout syllables two, three, and four (i.e., S2, S3, and S4).

Figure 7.

(A) All the intonation contours from statements normalized by subject, from Palenquero and Spanish. (B) All the intonation contours from statements averaged by language.

As described earlier in Section 2.3.1, the most substantial modes of F0 variation arising from the F0 variance of statements, shown in Figure 7A, were obtained through FPCA. Then, each FPC was explained using a linear mixed-effects model, including final stress, language, and generation as predictors, and speaker as a random variable for the intercept. Results indicate that, despite the great intonational similarities between Palenquero and Spanish statements, speakers produced statements using language-specific intonation patterns. As shown below, the intonation declination seemed to be partly suspended in Palenquero, as suggested from Figure 7B through the averaged plateau-shaped contour observed in Palenquero. Spanish statements, on the other hand, exhibited initial rises that were as steep as the declinations that followed them. Let us then now see the extent to which these language-specific differences were driven by final stress and generation effects.

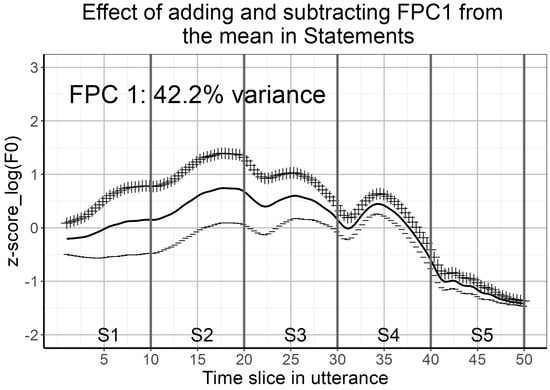

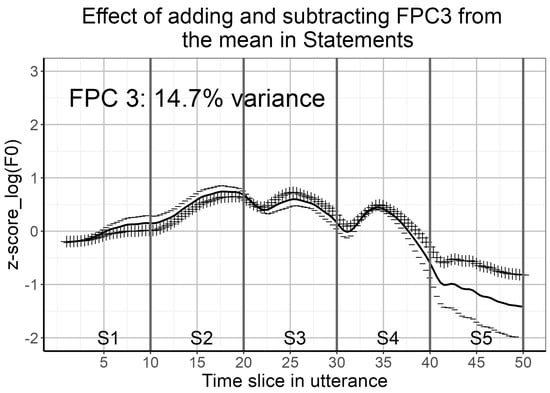

3.2.1. First Most F0 Variance, FPC1

The first most substantial F0 variation (i.e., FPC1) across statements is illustrated in Figure 8, and represents the effect of adding (+++ line) and subtracting (− − − line) FPC1 from the grand mean. The variance in FPC1 targets two specific trends, the first being related to flat contours preceding the boundary tone at the rightmost edge, which has resulted from subtracting FPC1 from the mean, in Figure 8, and the second one showing an initial steeper rise, followed by a pronounced declination, similar to the contour that has resulted from adding FPC1 to the mean, in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Effect of adding (+++ line) and subtracting (−−− line) FPC1 from the grand mean (solid line).

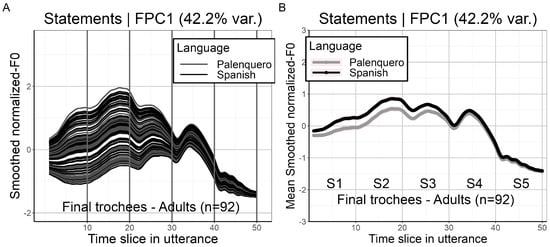

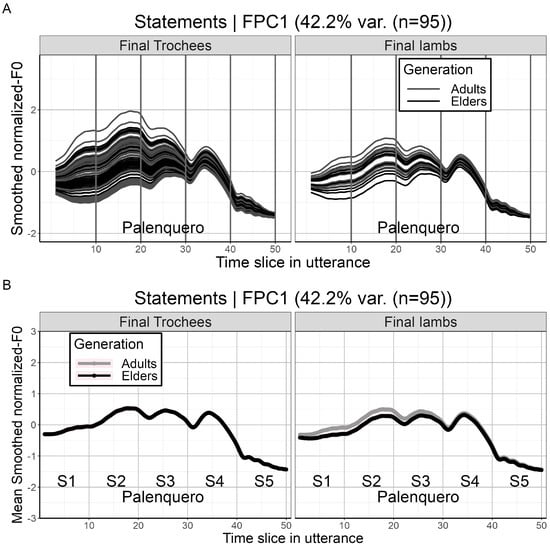

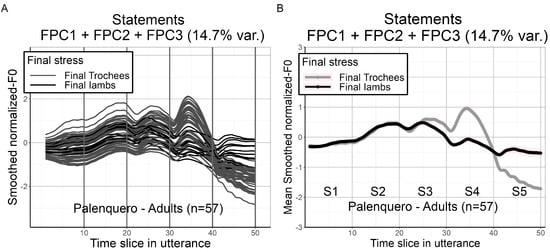

F0 variance captured by FPC1 was best explained by the linear model presented in Table 2. The model has yielded significant effects of language, and the two-factor interactions from final stress and language, as well as final stress and generation (F(5, 190) = 8.63, p = 2.17 ). As presented in Figure 9A4, the first substantial variance covers 42.2% of the total variance, and stretches across the first four syllables (i.e., S1–S4). On the whole, adult bilinguals showed two different trends upon which language-specific intonation might be based. The predicted average for FPC1 increased 1.64 units for Spanish statements ending in trochees, relative to Palenquero (B = 1.64, 95% CI [0.75, 2.54], p = 4 ). This implies that the intonation from Spanish statements trends towards wider pitch excursions in utterance-initial position, which results in steeper declinations, as illustrated in Figure 9B. Palenquero statements, on the other hand, exhibit shorter pitch excursions, whereby F0 peaks occur roughly at a similar height, showing a less pronounced declination across prenuclear intonation (see Figure 9B). In line with Correa (2017)’s results, the realization of plateau-shaped contours in Palenquero could be grounded in the realization of high F0 peaks that are occurring at a similar height, as effects of language in FPC1 suggest.

Table 2.

Linear mixed-effects model for FPC1 in statements (n = 196).

Figure 9.

(A) Variance scheme in FPC1 by language. (B) Variance scheme in FPC1 averaged by language.

The linear regression model presented in Table 2 also indicates that the intonation of elderly bilinguals was not sharply distinguished from adults when producing Palenquero statements ending in trochees (B = 0.21, 95% CI [−0.81, 1.22], p = 0.70). Therefore, within FPC1, there is no evidence to reject the idea that elderly speakers use language-specific intonation in statements similarly to adults. Consequently, the elderly have also yielded to the phonetic implementation of plateau-shaped contours in Palenquero (see statements ending in trochees, in Figure 10).

Figure 10.

(A) Variance scheme in FPC1 by final stress and generation. (B) Variance scheme in FPC1 averaged by final stress and generation.

Despite that, generational differences were attested from the two-factor interaction of final stress and generation (B = −1.91, 95% CI [−3.79, −0.04], p = 0.046). Thus, while both generations showed similar variability across Palenquero statements ending in trochees, they differed when these statements ended in final iambs. Palenquero statements from adults trended towards slightly wider pitch excursions in initial position, compared to the elderly (see Figure 10B). As was explained previously, wider and higher initial pitch excursions appeared to be a phonetic pattern that seems to be more closely related to the Spanish intonation of these bilinguals.

Nevertheless, language distinctions were also conditioned by final stress at the first most F0 variance (i.e., FPC1), given that adults showed a wider intonational distance between their two languages when statements ended with final iambs (B = 2.36, 95% CI [0.51, 4.20], p = 0.013). Figure 11A,B show, respectively, the variance scheme in FPC1 by final stress and language, and the predicted average contours for this interaction within FPC1. Initial pitch excursions tended to be high and steeper in Spanish statements ending in trochees, but were much higher in statements with final iambs, as shown in Figure 11B. As the model did not yield a three-factor interaction with final stress, language, and generation, differences based on the generational group do not seem to go beyond the ones presented in Figure 10, at least for the first most substantial variance. Therefore, it all leads to believe that elderly bilinguals would also exhibit a wider distance between the intonation of their two languages when statements end in final iambs, in the same way as adults did (see Figure 11).

Figure 11.

(A) Variance scheme in FPC1 by final stress and language. (B) Variance scheme in FPC1 averaged by final stress and language.

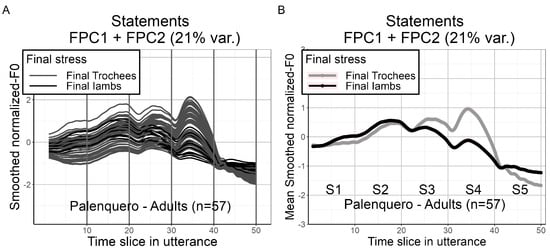

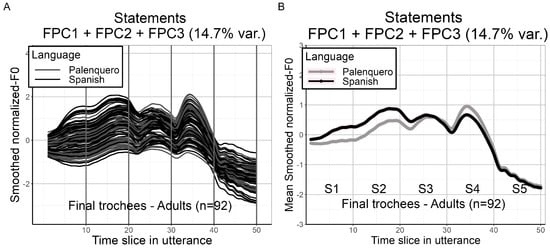

3.2.2. Second Most F0 Variance, FPC2

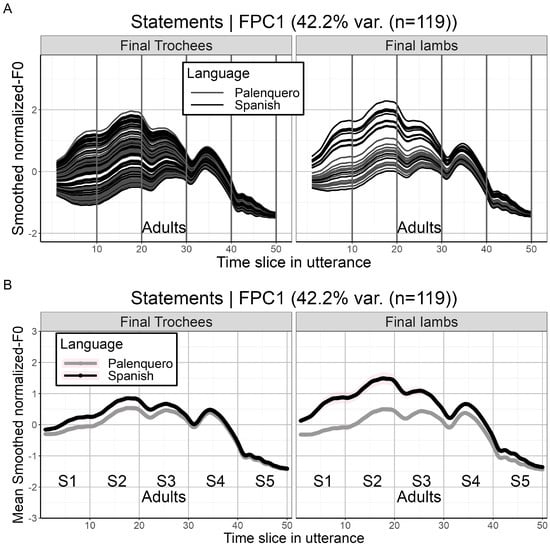

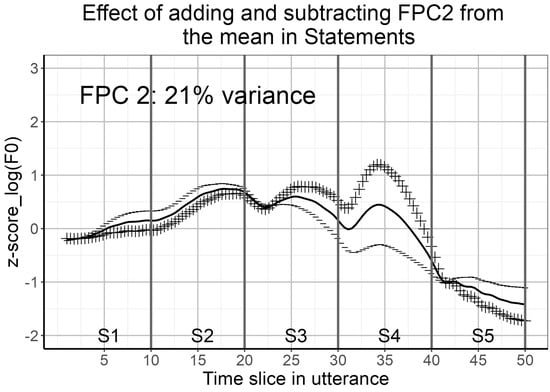

The second most substantial F0 variation (i.e., FPC2) is illustrated in Figure 12, which represents the effect of adding and subtracting FPC2 from the mean. The variance in FPC2 covers 21% of the total variance, and targets two different trends whose main locus is on the fourth syllable. More specifically, F0 was found to be high on this syllable, when FPC2 was added to the grand mean, and low, when FPC2 was subtracted from the grand mean. F0 variance captured by FPC2 was explained by the linear mixed-effects model presented in Table 3. The model indicates that the intonation variance contained in FPC2 was conditioned by final stress, language, and the two-factor interaction of language and generation (F(4, 191) = 74.03, p = 8.70 ). In order to better understand F0 variance in FPC2, it was cumulatively added to the variance in FPC1. Therefore, effects are described incrementally, as illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Effect of adding (+++ line) and subtracting (−−− line) FPC2 from the grand mean (solid line).

Table 3.

Linear mixed-effects model for FPC2 in statements (n = 196).

Figure 13.

(A) Variance scheme in FPC2 by language. (B) Variance scheme in FPC2 averaged by language.

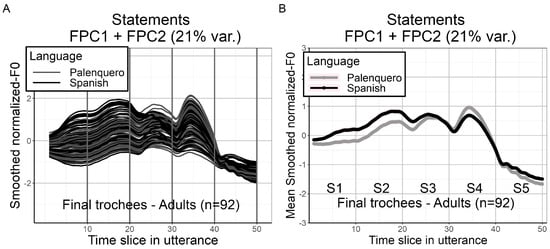

The predicted average for FPC2 decreased −1.16 units for Spanish statements ending in trochees, compared to Palenquero (B = −1.16, 95% CI [−1.62, −0.70], p = 1.55 ). As adult bilinguals are the reference group, this means that, within the second most F0 variance, adults decreased FPC2 in Spanish statements trending towards the F0 contour that resulted from subtracting FPC2 from the mean, in Figure 12. F0 peaks over final trochees in Spanish statements were lower than Palenquero peaks, as illustrated in Figure 13B. The variance scheme in FPC2 by language condition is shown in Figure 13A, and it seems to be partly connected to FPC1, given that wider pitch excursions in statement-initial position also manifested when FPC2 was subtracted from the mean (see Figure 12). Since FPC2 decreased in Spanish statements, the fact that wider pitch excursions were followed by a steeper declination appears to have significantly affected F0 height in the nuclear position of Spanish statements, as presented in Figure 13B. Palenquero statements, on the contrary, showed shorter pitch excursions in initial position, and high peaks occurring at a similar height. This latter might explain why Palenquero’s high F0 peaks over final trochees were higher than Spanish (see Figure 13).

Did elderly bilinguals show the same variance exhibited by adults in FPC2? Indeed, both generations showed the same language-specific patterns. However, the intonational distance between the two languages was wider for the elderly (B = −0.76, 95% CI [−1.49, −0.02], p = 0.043). Figure 14A,B show, respectively, the variance scheme in FPC2 by language and generation, and the predicted average contours for this interaction within FPC2. Spanish statements from elderly bilinguals exhibited much wider pitch excursions in utterance-initial position, and lower F0 peaks over final trochees, maintaining their two languages slightly more intonationally distinct than adults (see Figure 14B).

Figure 14.

(A) Variance scheme in FPC2 by language and generation. (B) Variance scheme in FPC2 averaged by language and generation.