Abstract

The distinction between weak and strong islands has been extensively explored in the literature from both a descriptive and analytical perspective. In this paper, I document and analyze island constructions and constraints in Mende, an understudied Mande language spoken in Sierra Leone. Mende has both weak islands (left branch and wh-islands) and strong islands (adjunct clauses, sentential subjects, and coordinate structures). Intriguingly, it has a third class of islands, that I call mixed islands which show a subject–non-subject asymmetry in allowing for movement out of relative clauses, only when they modify the subject. As such, subject-modifying RCs cannot be classified as (strong/weak) islands in Mende. This is the first systematic work on islands and island constraints in the Mande language family, and, as such, it brings novel data from an understudied language family to bear on our understanding of A-bar dependencies and the study of island escape in African languages. It also calls into question a neat paradigm of cross-linguistic island constraints. Importantly, this work also lays down a baseline for future research on island constraints in the broader Mande language family. In order to discuss island constraints, this paper also lays out the first analysis of relative clauses in Mende, while integrating new research on the left periphery, focus constructions, and wh-constructions.

1. Introduction

The literature on resumptive pronouns (RPs) indicates that they can amnesty island violations in many languages (c.f. Christensen and Nyvad 2014; McCloskey 2017). Recent work on African languages, however, shows that numerous languages do not fit neatly within the traditional categories of islandhood (c.f. Wolof: Torrence 2005, 2012; Krachi: Torrence and Kandybowicz 2015; Asante Twi: Hein and Georgi 2020; Igbo: Georgi and Amaechi 2020; Shupamem: Schurr et al. 2024; Akan: Murphy and Korsah, forthcoming; and Ikpana: Kandybowicz et al. 2021, 2023). In this paper, I show that islandhood in Mende, an understudied OV Mande language spoken in Sierra Leone, challenges the current theory. While there are both weak and strong islands in the language (Smith 2023), I propose that relative clauses are Mixed Islands, as they show a subject–non-subject asymmetry in permitting extraction, only when they modify the subject. This asymmetry can be seen in (1) and (2).

In (1a), the subject is modified by the string-adjacent relative clause, while (1b) shows that wh-movement out of the relative clause to the matrix left periphery is permitted with the 3rd person plural RP ti (glossed 3pl.rp) surfacing in the relative clause.1 In (2a), the pre-verbal direct object is modified by an obligatorily stranded post-verbal relative clause. In this context, extraction out of the relative clause is blocked, even with the RP (2b).

| (1) | a. | nyápú-í-sìà | [tí | netí-í-síà | vέlὲ-ngá] | Subject-modifying RC |

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | net-def-pl | weave-prf | |||

| tí | Mὲlí | gbáfà-ngà | ||||

| 3pl.sm | Mary | insult-prf | ||||

| ‘The girls who wove the nets insulted Mary.’ | ||||||

| b. | gbὲ-ngái | mìá | nyápú-í-sìà | [tí | ||

| what-pl | foc.l | girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | |||

| tíi | vέlὲ-ngá] | tí | Mὲlí | gbáfà-ngà | ||

| 3pl.rp | weave-prf | 3pl.sm | Mary | insult-prf | ||

| ‘What are they that the girls who wove them insulted Mary?’ what is x, such that the girls who wove x insulted Mary? | ||||||

| (2) | a. | Mὲlí | ndúpú-í-sìà | {*[tí | nétí-í-sìà | Object-modifying RC |

| Mary | child-def-pl | 3pl.sm | net-def-pl | |||

| vέlὲ-ngá]} | l -ngá | {[tí | nétí-í-sìà | vὲlέ-ngá]} | ||

| weave-prf | see-prf | 3pl.sm | net-def-pl | weave-prf | ||

| ‘Mary saw the children who wove the nets.’ | ||||||

| b. | *gbέ-ngái | mìá | Mὲlí | ndúpú-í-sìà | ||

| what-pl | foc.l | Mary | child-def-pl | |||

| l -ngá | [tí | tíi | vέlὲ-ngá] | |||

| see-prf | 3pl.sm | 3pl.rp | weave-prf | |||

| Intended: ‘What did Mary see the children who wove them?’ what is x, such that Mary saw the children who wove x? | ||||||

In this paper, I investigate this distinction. I discuss the structure and distribution of relative clauses, investigating the clausal structure of Mende, while also considering the obligatory stranding of relative clauses below their head. I conclude by comparing the factors that influence the permissibility of extraction in Mende with the factors that influence extractability out of relative clauses in Mainland Scandinavian languages.

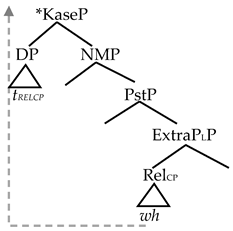

I show that extraction out of relative clauses is sanctioned only when the RC modifies the subject and is blocked for object-modifying RCs. As such, I refer to them as mixed islands, since their status as an island is dependent on the position of the relative clause within the matrix clause. When the relative clause CP is in a high position in the matrix clause (SpecExtraPh), which immediately dominates SubjP, extraction is possible. On the other hand, when it is below the matrix verb in SpecExtraPl, movement is blocked. Since wh-movement is sanctioned out of subject-modifying RCs in Mende, they cannot be classified as (strong/weak) islands.

To my knowledge, this is the first systematic work on islands and island constraints in the Mande language family. As such, it brings novel data from an understudied language family to bear on our understanding of A-bar dependencies. Similar to the other African languages noted above, it calls into question a neat paradigm of cross-linguistic island constraints. Importantly, this work also lays down a baseline for future research on island constraints in the broader Mande language family. In order to discuss island constraints, this paper also lays out the first analysis of relative clauses in Mende, while integrating new research on the left periphery, focus constructions, and wh-constructions (see Smith 2021b, 2023 for initial research on these topics).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces the language and previous research while also sketching relevant Mende syntax. Section 3 argues that a movement analysis, and not base generation, best captures the facts of A-bar constructions in Mende. Section 4 introduces and describes relative clause mixed islands. Section 5 is a conclusion.

2. Previous Research and Mende Syntax

Mende is part of the broader Mande language family spoken throughout west Africa and is classified as a Western Mande language, most similar to Loko and Bandi. The Mande language family is considered an early offshoot of the Niger-Congo family (Williamson and Blench 2000).

Mende is a Southwestern Mande language, with about 2.5 million speakers in Sierra Leone and Liberia. There are four main dialects: Kpa, Kɔɔ, Wanjaama, and Sewama with a high degree of lexical similarity (Eberhard et al. 2023). While most previous research has focused on the Kɔɔ and Kpa dialects, this research focuses on Sewama Mende, a dialect that has been relatively unstudied. The data were gathered both in person and over Zoom, working with native speakers in Bo, Sierra Leone.

A number of Mende grammars have been produced over the years, including work by Schön (1884), Migeod (1908), Aginsky (1935), Crosby and Ward (1944), Innes (1961, 1967, 1969), Spears (1967), and Brown (1982). Most previous research in the language focuses on tone (c.f. Dwyer 1971, 1978; Leben 1973, 1978; and Goldsmith 1976) and word-initial consonant mutation (c.f. Dwyer 1969; Conteh et al. 1983, 1986). In my investigation of Sewama Mende, its tone does not align with that reported in the literature. I have marked surface tone throughout. I will indicate contexts in which word-initial consonant mutation occurs when relevant to the discussion.

Very little syntactic analysis has been developed for Mende. Sengova (1981) considers tense and aspect in the language and includes a good deal of syntactic description to lay out his arguments regarding the connection between syntax and the semantics of tense and aspect. Other syntactic analyses include Smith (2023, forthcoming a, forthcoming b).

2.1. Mende Syntax

Typical of Mande languages (Vai: Welmers 1976; Lorma: Dwyer 1981; Wan: Nikitina 2009, 2011, 2012, 2019; Bambara: Fofana and Traoré 2003; Mandinka: Creissels 2024), Mende has SOVX word order. In this remainder of Section 2, I move beyond this generalization and describe the clausal structure of Mende in more detail.

| (3) | S(ubject) | SM | O(bject) | V(erb) | X | ||

| nyápú-í-sìà | tí | mángú-í-sìà | màjíá-ngá | sùkú-í-sìà | hùn | gbóì | |

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | mango-def-pl | sell-prf | school-def-pl | in | yesterday | |

| ‘The girls sold the mangoes at the schools yesterday.’ | |||||||

Mende does not have a noun classification system as seen in the forms of the plural nouns in (3), which show no noun class marking. Welmers (1971, p. 131) notes that this is true of the Mande languages more broadly.

In many Mande languages (Bearth 2009; Creissels 2019), including Mende (Innes 1967; Sengova 1981; Smith, forthcoming a) various clauses contain a subject marker that follows the subject in the TAM position agreeing with it in number and person, while also encoding habituality and negation, when present (glossed as hab for habitual constructions and sm (subject marker) for non-habitual constructions).2 I provide a more detailed analysis in Section 2.3, but for now note the contrast between the subject markers in (3) and (4). While the 3rd person plural subject marker for the past tense in (3) is ti, it is ta for the present/habitual tense in (4a). The 3rd person singular subject marker for the habitual tense in (4b) surfaces as a, pointing towards a polymorphemic structure.

| (4) | a. | nyápú-í-sìà | t.á | mángú-í-sìà | màjíà | l | sùkú-í-sìà | fóló | gbí | Habitual |

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.hab | mango-def-pl | sell | nm | school-def-pl | day | all | |||

| ‘The girls sell the mangoes at the school every day.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | nyápú-í | ø.á | mángú-í-sìà | màjíà | l | sùkú-í-sìà | fóló | gbí | ||

| girl-def | 3sg.hab | mango-def-pl | sell | nm | school-def-pl | day | all | |||

| ‘The girl sells the mangoes at the schools every day.’ | ||||||||||

Negation is marked immediately after the subject marker.

| (5) | S | SM | NEG | O | V-TNS | X | ||

| nyápú-í-sìà | tí | ì | mángú-í-sìà | màjíà-ní | sùkú-í-sìà | hùn | gbóì | |

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | neg | mango-def-pl | sell-pst | school-def-pl | in | yesterday | |

| ‘The girls did not sell the mangoes at the schools yesterday.’ | ||||||||

Tense is marked as a suffix on the verb, as seen in comparing the past tense marker—(n)i in (3) with the future marker ma in (6).3

| (6) | S | SM | O | V-TNS | X | |||

| nyápú-í-sìà | tí | mángú-í-sìà | màjíà-má | á | sùkú-í-sìà | hùn | síná | |

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.fut | mango-def-pl | sell-fut | nm | school-def-pl | in | tomorrow | |

| ‘The girls will not sell the mangoes at the schools tomorrow.’ | ||||||||

Anticipating a more detailed discussion in Section 3.1, I highlight three types of focus in the language here. Mende has two mutually exclusive focus markers: mia (glossed as foc.l), which occurs in the left periphery and lɔ which surfaces in TP. The marker lɔ occurs in two distinct contexts—it can either mark a narrow focus within the clause (glossed as foc.i) or surface as part of the verbal complex (glossed as nm—neutral marker). When mia is used, lɔ cannot surface in the clause, nor can lɔ surface twice. In contexts where lɔ is used, it can surface as a lengthening of the preceding word’s final vowel, as seen in (6) where the a following the future marker -ma is a manifestation of lɔ. While they seem to be related, I set aside questions related to the connection between lɔ as an in situ focus and lɔ that occurs within the verbal complex as a topic for future research.4

| (7) | a. | Kpànâ | nyápú-í-sìà | làtù-(n)í | *(l ) | Neutral focus | |

| Kpana | girl-def-pl | praise-pst | nm | ||||

| ‘Kpana praised the girls.’ | |||||||

| b. | nyápú-í-sìà | mìà | Kpànâ | tíi | làtù-ngá | Left peripheral focus | |

| girl-def-pl | foc.l | Kpana | 3pl.rp | praise-prf | |||

| ‘It is the girls that Kpana praised.’ | |||||||

| c. | Kpànâ | nyápú-í-sìà | l | làtù-ngá | In situ focus | ||

| Kpana | girl-def-pl | foc.i | praise-prf | ||||

| ‘Kpana praised the girls.’ | |||||||

Similar to most Mande languages (c.f. Mahou: Koopman 1984; Wan: Nikitina 2012; Jalkunan: Heath 2017), Mende is postpositional.

| (8) | Kpànâ | nyápú-í-sìà | làtù-í | l | sùkú-í-sìà | hùn |

| Kpana | girl-def-pl | praise-pst | nm | school-def-pl | in | |

| ‘Kpana praised the girls in the schools.’ | ||||||

In the following sections, I review in more detail some foundational aspects of Mende syntax that lay the groundwork for the ensuing discussion on island constructions and constraints in Mende.

2.2. Verbal Complements

In this section, I motivate an analysis of Mende clauses, working upwards from VP.

The Mande languages have traditionally been classified as having a strict SOVX order (Gensler 1994; Nikitina 2012; Creissels 2024). In Mende, the subject and object precede the verb with the dative object (encoded in a PP) and adjuncts following it.

| (9) | S | O | V | X | ||

| Kpànâ | nìké-í-sìà | g k -ngá | kpáá | hùn | gbóì | |

| Kpana | cow-def-pl | find-prf | farm | on | yesterday | |

| ‘Kpana found the cows on the farm yesterday.’ | ||||||

| (10) | S | O | V | Dat | X | ||

| Kpànâ | nèsí-í-sìà | vè-ngá | Mὲlí | wέ | nj p wà | hùn | |

| Kpana | pineapple-def-pl | give-prf | Mary | to | market | at | |

| ‘Kpana gave the pineapples to Mary at the market.’ | |||||||

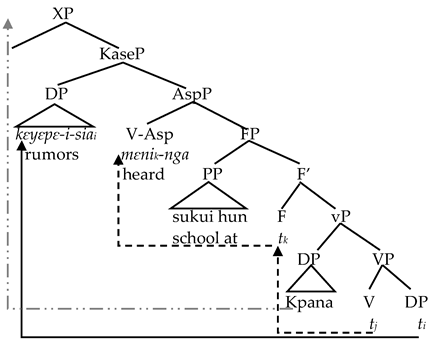

Following Kayne (1994), I argue that underlyingly Mende has a head-initial verb phrase and that the surface structure is derived via leftward movement (Smith 2021a). Similar to Aboh’s (2004) analysis for the Gbe languages, I argue that both the object and verb raise out of the vP. The verb head raises, through the functional head hosting the locative oblique, before adjoining the aspect (Asp) head, then the DP direct object raises into a higher position for Case (c.f. Koopman (1984, 1992) for the Mande languages Mahou and Bambara respectively.)5 Specifically, I argue that this position is the specifier of a Kase head (c.f. Major and Torrence, forthcoming for a similar analysis of Avatime).

| (11) | a. | Kpànâ | kέyὲpὲ-í-sìà | mέnì-ngá | sùkú-í-sìà | hùn |

| Kpana | rumor-def-pl | hear-prf | school-def-pl | at | ||

| ‘Kpana heard the rumors at school.’ | ||||||

| b. | Deriving SOV | |||||

| ||||||

In contrast to DP objects of verbs, CP objects do not raise into a pre-verbal Case position (along the lines of Stowell’s (1981) Case Resistance Principle). CP objects instead surface in an ‘extraposed’ position, a construction which has been documented in a number of languages (Major and Torrence, forthcoming for Avatime, Aboh (2004) for Gungbe, Zwart (1997) for Dutch).

| (12) | CP objects | |||||||

| Kpànâ | {hùngέ-ngá} | [kέ | nyápú-í-sìà | tí | mángú-í-sìà | yéyà-ngá] | {*hungɛ-nga} | |

| Kpana | explain-prf | c | girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | mango-def-pl | buy-prf | explain-prf | |

| ‘Kpana explained that the girls bought the mangoes.’ | ||||||||

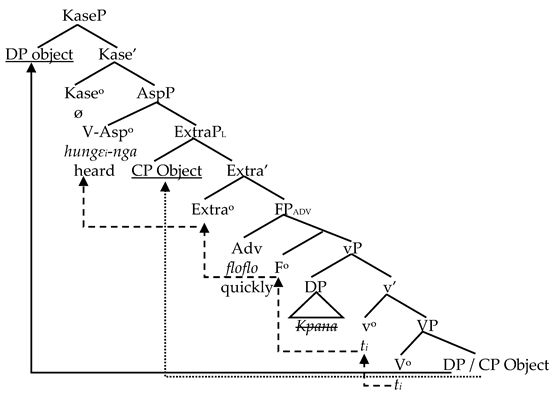

CP complements of the verb can raise, however, it is to a position below the surface position of the verb, as suggested by (13). Following Cinque (1999), I suggest that the celerative adverb floflo ‘quickly’ is in a fixed position above the verb phrase. In (13a), both the DP direct object and verb must raise into a position above the adverb, while in (13b) the verb obligatorily raises out of vP above the adverb, while the CP can optionally do so. My language consultant has confirmed that floflo ‘quickly’ in (b) modifies the matrix verb, not the embedded verb.

| (13) | a. | S | Odp | V | ADV | ||

| Kpànâ | {*floflo} | nd mí-í-sìà | {*floflo} | hùngέ-ngá | {flófló} | ||

| Kpana | quickly | story-def-pl | quickly | explain-prf | quickly | ||

| ‘Kpana quickly explained the story.’ | |||||||

| b. | S | V | ADV | Ocp | |||

| Kpànâ | hùngέ-ngá | {flófló} | [kέ | nyápú-í-sìà | tí | ||

| Kpana | explain-prf | quickly | c | girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | ||

| ADV | |||||||

| mángú-í-sìà | yéyà-ngá] | {flófló} | |||||

| mango-def-pl | buy-prf | quickly | |||||

| ‘Kpana quickly explained that the girls bought the mangoes.’ | |||||||

I sketch this derivation out in (14). The verb hungɛ ‘explain’ can take either a DP or CP object as its complement. The verb raises out of vP, head moving to the aspect marker. If the direct object is a DP, it raises into SpecKaseP (indicated by the solid-line arrow), but if it is a CP, it can either remain in situ, or raise. If it raises, an extraposition phrase (ExtraPL) with a null head merges above vP, and the CP modifier moves into its specifier (indicated by the dotted arrow).6

| (14) | DP/CP raising |

|

2.3. Subject Markers

As noted above, Mende subjects are followed by an obligatory subject marker. In (15a), the 3rd person plural subject marker is ta, and in (15b), the 3rd person singular is a.

| (15) | a. | nyápú-í-sìà | t.á | Kpànâ | làtú | l | Habitual SM |

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.hab | Kpana | praise | nm | |||

| ‘The girls praise Kpana.’ | |||||||

| b. | nyápú-í | ø.á | Kpànâ | làtú | l | ||

| girl-def | 3sg.hab | Kpana | praise | nm | |||

| ‘The girl praises Kpana.’ | |||||||

In past tense constructions, however, the 3rd person plural subject marker surfaces as ti, while the singular counterpart is null.

| (16) | a. | nyápú-í-sìà | tí | Kpànâ | làtú-í | l | Past tense SM |

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | Kpana | praise-pst | nm | |||

| ‘The girls praised Kpana.’ | |||||||

| b. | nyápú-í | ø | Kpànâ | làtú-í | l | ||

| girl-def | 3sg.sm | Kpana | praise-pst | nm | |||

| ‘The girl praised Kpana.’ | |||||||

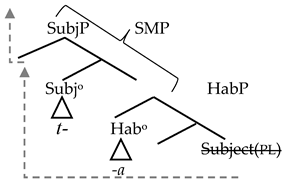

In light of these data, I suggest that subject markers are polymorphemic. Even though these subject markers have traditionally been orthographically written as a unit, they are the surfacing of a series of heads at the top of the middlefield. Syntactically, subject markers are structured as in the tree in (17), though I use the SMP (subject marker phrase) shorthand through the rest of the paper. The [t] encodes 3rd person plural agreement with the subject, which is triggered when the subject moves through SpecSubjP, while [a] encodes habitual aspect. The subject of the clause moves into a higher position, namely, SpecFinP (Rizzi 1997, 2001; Cardinaletti 1997; Smith, forthcoming a).

| (17) | The articulated structure of a Mende subject marker |

|

2.4. The Left Periphery

In this section, I consider in more detail the articulated structure of the left periphery in Mende, in which both topics and focused constituents can surface (Smith, forthcoming a).

| (18) | a. | nyápú-í-sìà | tí | Kpànâ | làtú-ngá | sùkú-í-sìà | hùn | ||

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | Kpana | praise-prf | school-def-pl | at | ||||

| ‘The girls praised Kpana at the schools.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Kpànâi | vá, | nyápú-í-sìà | tí | ngíi | TOP | |||

| Kpana | for | girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | 3sg | |||||

| làtú-ngà | sùkú-í-sìà | hùn | |||||||

| praise-prf | school-def-pl | at | |||||||

| ‘As for Kpana, the girls praised him at the schools.’ | |||||||||

| c. | Kpànâi | vá, | sùkú-í-sìàj | mìà | nyápú-í-sìà | TOP, FOC | |||

| Kpana | for | school-def-pl | foc.l | girl-def-pl | |||||

| tí | ngíi | làtú-ngá | tìj | hùn | |||||

| 3pl.sm | 3sg.rp | praise-prf | 3pl.rp | at | |||||

| ‘As for Kpana, it is the schools that the girls praised him at.’ | |||||||||

| d. | sùkú-í-sìàj | mìà, | Kpànâi | vá, | nyápú-í-sìà | FOC, TOP | |||

| school-def-pl | foc.l | Kpana | for | girl-def-pl | |||||

| tí | ngíi | làtú-ngá | tíj | hún | |||||

| 3pl.sm | 3sg.rp | praise-prf | 3pl.rp | at | |||||

| ‘It is the schools that, as for Kpana, the girls have praised him at.’ | |||||||||

Based on (18a), in (18b) the direct object Kpana surfaces in the left periphery as a topicalized constituent introduced by the postposition va ‘(as) for.’ In (18c), the topicalized constituent is followed by the focused constituent, while in (18d), the order of the topic and focused constituent changes, indicating that they are unordered in the left periphery.

Focus and topic constructions can also occur in embedded phrases where they follow the complementizer. The data in (19) show that both a topicalized and focused constituent can follow kɛ, the complementizer for an embedded statement.

| (19) | Mende left periphery (ForceP > TopP/FocP > FinP) | ||||||

| forceP | topP | focP | |||||

| Mὲlí | kítí-ngá | [kὲ | Kpànâj | vá, | sùkú-í-sìài | mìà | |

| Mary | doubt-prf | c | Kpana | for | school-def-pl | foc | |

| finP | tp | ||||||

| nyápú-í-sìà | tí | ngíj | làtú-ngá | tíi | hún] | ||

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | 3sg.rp | praise-prf | 3pl.rp | in | ||

| ‘Mary doubted that, as for Kpana, it is the schools in which the girls praised him.’ | |||||||

Following Rizzi (1997, 2001) in Smith, forthcoming a, I argue that kɛ heads a Force Phrase, taking the remainder of the clause as its complement and that mia heads a Focus Phrase, with the focused constituent moving into its specifier. Similarly, va heads a Topic Phrase, with the topicalized constituent moving into its specifier. In the previous section, I argued that the matrix subject moves into the specifier of a Finite Phrase. In (19), I have marked each of these phrases in the embedded clause.

3. Movement

3.1. Focus

Evidence for A-bar movement in Mende includes quantifier stranding and reconstruction effects. In (20a), the DP and quantifier are shown, while (20b) shows that they can surface in the left periphery and (20c) shows the quantifier stranded with the resumptive 3rd person plural pronoun ti surfacing in the canonical position. Following the reasoning in Sportiche (1988) and Fitzpatrick (2006), I take this as evidence that the DP in SpecFocP moved from its immediate preverbal position.

| (20) | Stranded DP object quantifier | ||||||

| a. | Kpànâ | lùmbé-í-sìà | kpέlέ | gáw -ngá | |||

| Kpana | lemon-def-pl | all | peel-prf | ||||

| ‘Kpana peeled all of the lemons.’ | |||||||

| b. | [lùmbé-í-sìà | kpέlέ]i | míá | Kpànâ | tii | gáw -ngá | |

| lemon-def-pl | all | foc.l | Kpana | 3pl.rp | peel-prf | ||

| ‘It is all the lemons that Kpana peeled.’ | |||||||

| c. | lùmbé-í-sìài | mìà | Kpànâ | tíi | kpέlέ | gáw -ngá | |

| lemon-def-pl | foc.l | Kpana | 3pl.rp | all | peel-prf | ||

| ‘It is all the lemons that Kpana peeled.’ | |||||||

In the remainder of this section, I use evidence from reconstruction effects to argue for a movement analysis, with resumptive pronouns functioning as traces of moved constituents. Reconstruction effects occur when a constituent surfaces in one part of the clause but acts as if it were in a lower part. I show two examples of these effects: Principle A binding and ideophone movement.

I turn first to Principle A binding. In (21a), the embedded statement has a DP subject Mary, which binds its reflexive object ta kpe ‘herself.’ In example (21b), the reflexive object surfaces in SpecFocP, where it cannot be bound by Mary. Since this sentence is grammatical and the reflexive is not bound in the left periphery, I conclude that it behaves as if it were in its canonical position, where it is bound by Mary.

| (21) | Principle A binding | |||||||

| a. | ndùpú-í-sìà | tí | ngí-ngá | {kὲ | Mὲlíi | [tà | kpé]i | |

| child-def-pl | 3pl.sm | remember-prf | c | Mary | 3sg | self | ||

| l -ngá | mὲmὲ | hùn} | ||||||

| see-prf | mirror | in | ||||||

| ‘The children remembered that Mary saw herself in the mirror.’ | ||||||||

| b. | [tà kpé]i | mìà | ndùpú-í-sìà | tí | ngí-ngá | |||

| 3sg self | foc.l | child-def-pl | 3pl.sm | remember-prf | ||||

| {kὲ | Mὲlíi | ngíi | l -ngá | mὲmὲ | hùn} | |||

| c | Mary | 3sg.rp | see-prf | mirror | in | |||

| ‘It is herself that the children remembered that Mary saw in the mirror.’ | ||||||||

A second example of a reconstruction effect concerns movement of an ideophone. Ideophones are relatively common in Niger-Congo languages and have been described as vivid sensory words (Dingemanse 2018; Downing 2019). Following Tamba et al. (2012) and Torrence (2013), I analyze ideophones as similar to adverbs in modifying a verb, with there being a strong selectional relationship between the ideophone and the verb, such that ideophones cannot appear with any verb, but only a few, or even just one. A surface discontinuity, therefore, is a result of movement. The following data show two ideophones: kpe which describes ‘a cut all the way through something’ and fikifiki which describes ‘a back-and-forth sawing motion.’ In (22a), the verb lewe ‘cut’ is modified by the ideophone kpe. In (22b), the verb bɔ ‘shoot’ is used. While in English something can be described as having been shot ‘clean through’ (e.g., ‘He was shot clean through the leg.’), kpe cannot be used with the verb bɔ ‘shoot’ in Mende (22c). Note that given the close selectional relationship, the verb and ideophone are string adjacent.

| (22) | a. | Pìtá | nèsí-í-sìà | lèwè-ngá | kpé | Ideophone |

| Peter | pineapple-def-pl | cut-prf | clean.through | |||

| ‘Peter cut the pineapple clean through.’ | ||||||

| b. | Pìtá | k lí-í | b -ngá | |||

| Peter | leopard-def | shoot-prf | ||||

| ‘Peter shot the leopard.’ | ||||||

| c. | *Pìtá | k lí-í | b -ngá | kpé | ||

| Peter | leopard-def | shoot-prf | clean.through | |||

| Intended: ‘Peter shot the leopard clean through.’ | ||||||

Based on (23a), in (23b) the verb lewe ‘cut’ is modified by the ideophone fikifiki, indicating the cutting motion as being ‘back and forth.’ In (23c), the ideophone surfaces in the left periphery, while the verb remains in its canonical position. The most straightforward explanation for this separation of the ideophone from the verb it modifies is that the ideophone has moved from its canonical post-verbal position to the left periphery, from which it still modifies the verbal action.

| (23) | a. | Pìtá | mbèké-í-síà | lèwè-ngá | ||||

| Peter | branch-def-pl | cut-prf | ||||||

| ‘Peter cut the branches.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Pìtá | mbèké-í-síà | lèwè-ngá | fíkífìkì | ||||

| Peter | branch-def-pl | cut-prf | sawing.motion | |||||

| ‘Peter cut the branches with a sawing motion.’ | ||||||||

| c | fíkífíkí | mìà | Pìtá | mbèké-í-síà | lèwè-ngá | Ideophone movement | ||

| sawing.motion | foc.l | Peter | branch-def-pl | cut-prf | ||||

| ‘It is with a sawing motion that Peter cut the branches.’ | ||||||||

3.2. Wh-Questions

Wh-questions in Mende are structured similarly to focus constructions in that they can occur in situ or in the left periphery, they require a focus particle (lɔ or mia, respectively), and they utilize RPs in movement constructions. In this section, I briefly introduce relevant wh-constructions. For further description and analysis, see Smith (2021b). Table 1 is a summary of Mende wh-phrases, an indication of which can be marked as plural, as well as the corresponding resumptive pronouns.

Table 1.

Wh-expressions in Mende.

Questions in Mende can be formed either in situ or in the left periphery. Based on (24a), in (24b) the subject has been transformed into the wh-word yɔ-ɔ, which is derived from a phonological process that occurs when ye ‘who’ is focus marked by lɔ.7 In (24c), an in situ construction, the direct object surfaces as plural-marked wh-word gbɛ-nga-a ‘what (pl),’ with the focus marker lɔ, surfacing as a lengthening of the morpheme final [a]. In (24d), it is shown that the wh-word can also surface in the left periphery.

| (24) | Argument wh-questions | |||||||

| a. | ndùpú-í | nìké-í-síà | g k -ngá | |||||

| child-def | cow-def-pl | find-prf | ||||||

| ‘The child found the cows.’ | ||||||||

| b. | y - | nìké-í-síà | g k -ngá | Wh-subject | ||||

| who-foc.i | cow-def-pl | find-prf | ||||||

| ‘Who found the cows?’ | ||||||||

| c. | ndùpú-í | gbὲ-ngá-á | g k -ngá | In situ object | ||||

| child-def | what-pl-foc.i | find-prf | ||||||

| ‘What did the child find?’ | ||||||||

| d. | gbὲ-ngái | mìà | ndùpú-í | tíi | g k -ngá | Fronted object | ||

| what-pl | foc.l | child-def | 3pl.rp | find-prf | ||||

| ‘What did the child find?’ | ||||||||

Turning next to adjuncts, in (25a) the locative phrase njɔpɔwa hun ‘at the market’ and temporal phrase gboi ‘yesterday’ both occur post-verbally. In (25b), a locative wh-phrase mindo ‘where’ focused in situ is shown, while (25c) shows that the wh-phrase can surface in the left periphery. In (25d), it is shown that the temporal adverb can be transformed into the wh-phrase migbe ‘when’, with (25e) showing that migbe can move to the left periphery. Note that there is no resumptive pronoun that surfaces for migbe.

| (25) | Adjunct wh-questions | ||||||

| a. | Pìtá | mángú-í-sìà | mὲ-ngá | nj p wá | |||

| Peter | mango-def-pl | eat-prf | market | ||||

| hùn | gbóí | ||||||

| at | yesterday | ||||||

| ‘Peter ate the mangoes at the market yesterday.’ | |||||||

| b. | Pìtá | mángú-í-sìà | mὲ-ngá | míndò | In situ adjunct | ||

| Peter | mango-def-pl | eat-prf | where | ||||

| l | gbóí | ||||||

| foc.i | yesterday | ||||||

| ‘Where did Peter eat the mangoes yesterday?’ | |||||||

| c. | míndói | mìà | Pìtá | mángú-í-sìà | mὲ-ngá | Fronted adjunct | |

| where | foc.l | Peter | mango-def-pl | eat-prf | |||

| nài | gbóí | ||||||

| loc.rp | yesterday | ||||||

| ‘Where is it that Peter ate the mangoes yesterday?’ | |||||||

| d. | Pìtá | mángú-í-sìà | mὲ-ngá | nj p wá | hùn | In situ adjunct | |

| Peter | mango-def-pl | eat-prf | market | at | |||

| mígbè | l | ||||||

| when | foc.i | ||||||

| ‘When did Peter eat the mangoes at the market?’ | |||||||

| e. | mígbè | mìà | Pìtá | mángú-í-sìà | mὲ-ngá | Fronted adjunct | |

| when | foc.l | Peter | mango-def-pl | eat-prf | |||

| nj p wá | hùn | ||||||

| market | at | ||||||

| ‘When is it that Peter ate the mangoes at the market?’ | |||||||

In multi-clause wh-constructions, Mende permits in situ, partial movement, and full movement. In (26a), the verb mɛni ‘hear’ takes a CP complement. In (26b), the wh-phrase surfaces in situ in the embedded clause, while in (26c) it partially moves to the left periphery of the embedded clause. In both (26b-c), the wh-phrase in the embedded clause has a matrix scope. Full movement is shown in (26d).

| (26) | Multi-clause Wh-movement | ||||||

| a. | Kpànâ | mὲnì-ngá | [kὲ | nyàpú-í-sìà | tí | Embedded clause | |

| Kpana | hear-prf | c | girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | |||

| mángú-í-sìà | yèyà-ngá] | ||||||

| mango-def-pl | buy-prf | ||||||

| ‘Kpana heard that the girls bought the mangoes.’ | |||||||

| b. | Kpànâ | mὲnì-ngá | [kὲ | nyàpú-í-sìà | tí | Wh-In situ | |

| Kpana | hear-prf | c | girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | |||

| gbὲ-ngá-á | yèyà-ngá] | ||||||

| what-pl-foc.l | buy-prf | ||||||

| ‘What (PL) did Kpana hear that the girls bought?’ | |||||||

| c. | Kpànâ | mὲnì-ngá | [kὲ | gbὲ-ngái | mìà | Partial movement | |

| Kpana | hear-prf | c | what-pl | foc.l | |||

| nyàpú-í-sìà | tí | tíi | yèyà-ngá] | ||||

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | 3pl.rp | buy-prf | ||||

| ‘What (PL) did Kpana hear that it is that the girls bought?’ | |||||||

| d. | gbὲ-ngái | mìà | Kpànâ | mὲnì-ngá | [kὲ | Full movement | |

| what-pl | foc.l | Kpana | hear-prf | c | |||

| nyápú-í-sìà | tí | tíi | yèyà-ngá] | ||||

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | 3pl.rp | buy-prf | ||||

| ‘What (PL) is it that Kpana heard that the girls bought?’ | |||||||

I turn next to relative clauses and their status as mixed islands.

4. Mixed Islands

The distinction between weak and strong islands has been extensively explored in the literature from both a descriptive and analytical perspective (Ross 1967; Chomsky 1977; Szabolcsi and den Dikken 2002; Szabolcsi and Lohndal 2017). In this section, I discuss relative clause islands, which do not neatly fit into either category. Instead, I refer to them as mixed islands, because, as I show, there is a subject–object extraction asymmetry. Before considering these constructions, I first lay the groundwork by describing the structure of DPs. I then look at relative clauses and their distribution before considering their status as islands.

4.1. Mende DP Structure

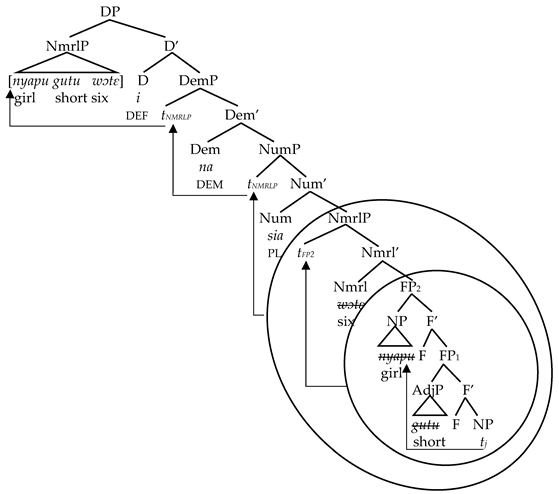

The noun is the leftmost element in Mende DPs, with number and (in)definite markers following (27a). Adjectives precede numerals, and both precede the definite and number markers (27b-c). Demonstratives surface between the definite marker and number (27d). I assume minimally that NPs raise into SpecDP (Ritter 1991). I further assume that adjectives are in a fixed hierarchy above the NP, in the specifier of Functional Phrases (Sproat and Shih 1990; Cinque 1994). The surface structure of a Mende DP is shown in (27e).

| (27) | a. | nyàpú-í-sìà | n-def-pl | |||

| girl-def-pl | ||||||

| ‘the girls’ | ||||||

| b. | nyàpú | gùtú-í-sìà | n-adj-def-pl | |||

| girl | short-def-pl | |||||

| ‘The short girls.’ | ||||||

| c. | nyàpú | gùtú | w tέ-í-sìà | n-adj-numb-def-pl | ||

| girl | short | six-def-pl | ||||

| ‘The six short girls.’ | ||||||

| d. | nyàpú | gùtú | w tέ-í | ná-sìà | n-adj-numb-def-dem-pl | |

| girl | short | six-def | dem-pl | |||

| ‘Those six short girls’ | ||||||

| e. | N-(Adj)-Det-(Dem)-Num | |||||

I propose that the order in (40d) is derived as follows in (41). Immediately above the NP is a functional phrase (FP1), which hosts the adjective in its specifier (Cinque 1993; Crisma 1993). Above it is FP2, into whose specifier the NP raises.8 The NP raises again, pied-piping FP2 with it, into the specifier of the Numeral Phrase. The entire Numeral Phrase then raises into the SpecNumP, before raising again into SpecDemP, and finally into SpecDP, yielding the surface structure.9

| (28) | Complex NP raising to SpecDP |

|

4.2. Relative Clauses in Mende

As noted in the introduction, this is the first analysis of relative clauses in Mende in the generative tradition of which I am aware.10 As such, the following sections provide a detailed description and analysis of their structure. I analyze relative clauses in Mende under a Kaynian (D+CP) approach (Kayne 1994), arguing that the head of the relative clause originates inside of a CP complement to a head in the DP functional structure, and raises to SpecDP. As I show below, this is strikingly similar to what is found in ordinary DPs.

In (29a), a relativized subject nyapuisia ‘the girls’ as the head of the relative clause is shown. The object and verb follow, with temporal and locative adjuncts occurring post-verbally. Mende RCs do not have a relative pronoun, and relativized subjects do not have a resumptive pronoun. Differing from a matrix clause, it is ungrammatical for a neutral marker (lɔ) to surface on the verb. In (29b), a relativized object is shown, which precedes the clause. In contrast to relativized subject in (29a), the 3rd person plural resumptive pronoun ti surfaces in the object position, resuming the object tɛisia ‘the chickens.’ The verb is marked for past tense, but, again, no neutral marker can appear.11

| (29) | a. | Subject Relativization | |||||

| nyàpú-í-sìài | [ti | tá | tέ-í-sìà | màjíá | |||

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.hab | chicken-def-pl | sell | ||||

| (*l ) | wàtì | gbí | nj p wá | hùn] | |||

| nm | time | all | market | at | |||

| ‘The girls who always sell the chickens at the market.’ | |||||||

| b. | Object Relativization | ||||||

| tέ-í-sìàj | [nyàpú-í-sìà | tí | tíj | yèyá-nì | |||

| chicken-def-pl | girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | 3pl.rp | buy-prf | |||

| (*l ) | nj p wá | hùn] | |||||

| nm | market | at | |||||

| ‘The chickens that the girls bought at the market.’ | |||||||

In (30), the parallel structure between a relativized subject (a), relativized object (b), and ordinary DP (c) is shown.

| (30) | Structure of relative clauses | |||||||||

| a. | srel | def | num | [__ | sm | do | v | tns | x] | |

| b. | orel | def | num | [s | sm | rp | v | tns | x] | |

| c. | np | def | num | [__ | ] | |||||

Having argued that the head of the relative clause begins within the clause, I next show that the relative clause is a CP. Evidence for this includes the presence of topic and focus constructions in the left periphery of the relative clause. In (31a), the head of the relative clause is the subject of the matrix clause, while (31b) is a topic construction and (31c) is a focus construction. In Section 2.4, I argued that both topics and focus constructions occur in the left periphery, and these data show that left peripheral constructions can occur in a relative clause. We can conclude, therefore, that the relative clause is, in fact, a CP.

| (31) | Relative clause left periphery | |||||||

| a. | nyàpú-í-sìài | [Kpànâ | tìi | l -nì | kpàà | hùn | ||

| girl-def-pl | Kpana | 3pl.rp | see-pst | farm | on | |||

| gbóí] | tí | mbè-í | m l -ì | l | ||||

| yesterday | 3pl.sm | rice-def | burn-pst | nm | ||||

| ‘The girls that Kpana saw yesterday on the farm burned the rice.’ | ||||||||

| b. | nyàpú-í-sìài, | [gbóí | vá, | Kpànâ | tíi | l -nì | ||

| girl-def-pl | yesterday | for | Kpana | 3pl.rp | see-prf | |||

| kpàà | hùn] | tí | mbè-í | m l -ì | l | |||

| farm | on | 3pl.sm | rice-def | burn-pst | nm | |||

| ‘The girls, as for yesterday, Kpana saw them on the farm (they) burned the rice.’ | ||||||||

| c. | nyàpú-í-sìài | [kpáá | hùn | mìà | Kpànâ | tìi | ||

| girl-def-pl | farm | on | foc.l | Kpana | 3pl.rp | |||

| l -nì | nà | gbóí] | tí | mbè-í | m l -ì | l | ||

| see-pst | loc | yesterday | 3pl.sm | rice-def | burn-pst | nm | ||

| ‘The girls, it is on the farm that Kpana saw them yesterday (they) burned the rice.’ | ||||||||

4.2.1. The Derivation of Relative Clauses

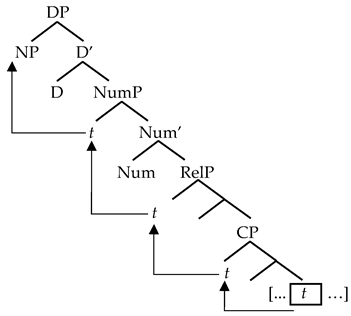

The derivation of a relative clause is set out in (45). The relativized nominal (‘NP’) begins within the CP. The NP raises to SpecCP, and it subsequently raises into the specifier of a relative phrase (RelP) (as proposed by Collins 2015). Paralleling the structure laid out in (28), I suggest, instead, that it is the Num head that selects the Relative Phrase with the NP raising into the DP left periphery, via SpecNumP before surfacing in SpecDP. In the remainder of this section, I motivate this analysis.

| (32) | Derivation of a relative clause |

|

I want to briefly point out that the tree in (32) does not capture the full derivation. Crucially, under this analysis the DP head of the relative clause is not a constituent. I propose that relative clause constructions in Mende are derived when the CP portion of the clause raises into the specifier of a functional phrase that I call an ExtraP (see Section 2.2 for a similar argument for CP complements). The DP remnant then raises into a higher position. This can be seen in the following data, where in (33a) the object appears in a pre-verbal position, with the CP portion remaining post-verbal. Though not as clearly evident, I propose that a similar process yields the word order in (33b). I discuss ‘extraposition’ in greater detail in the following section.

| (33) | a. | Object-modifying RC | |||||||||||||

| Kpànâ | njè-í-sìài | màjìà-í | l | [ti | tí | ngì | lέ-ngá | gbálè-nì] | |||||||

| Kpana | goat-def-pl | sell-pst | nm | 3pl.sm | 3sg | chicken-pl | hurt-pst | ||||||||

| ‘Kpana sold the goats that hurt his chickens.’ | |||||||||||||||

| b. | Subject-modifying RC | ||||||||||||||

| nyàpú-í-sìài | [ti | tí | njé-í-sìà | g k -ní] | tí | káté-í | kpàyà-í | l | |||||||

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | goat-def-pl | find-pst | 3pl.sm | fence-def | strengthen-pst | nm | ||||||||

| ‘The girls who found the goats strengthened the fence.’ | |||||||||||||||

I turn next to reconstruction effects to argue that the head of the relative clause originates within the clause. The first evidence that I consider is reflexive binding. In (34a) and (34b), the DO is bound by the subject, with the object in (34a) being non-reflexive, while the object in (34b) is reflexive. In both cases, it is a possessive construction. In (34c), the nominal constituent containing the reflexive ta kpe ‘himself’ is the head of the relative clause and has raised into a pre-verbal position, with the relative clause in a post-verbal position. In this position, ta kpe ‘himself’ can take either Kpana or John as antecedent. Since ta kpe can be understood as referring to John, we can conclude that it reconstructs into the relative clause. In other words, in regards to binding, it behaves as if it were in its canonical position between the subject and verb of the relative clause. In (34d), the reflexive surfaces in the left periphery of the matrix clause, but can reconstruct into the c-command domain of John (as indicated by the subscripts).

| (34) | Reconstruction effects: reflexive binding | ||||||||||

| a. | J ni | [ngìj/Kpànâj | nὲnέ-í-sìà | gbá | kòló | má] | ndàlá-í | l | |||

| John | 3sg/Kpana | shadow-def-pl | stuck | paper | on | draw-pst | nm | ||||

| ‘John drew pictures of him/Kpana’ | |||||||||||

| b. | J ni | {[tá | kpé]i | nὲnέ-í-sìà | gbá | ||||||

| John | 3sg | self | shadow-def-pl | stuck | |||||||

| kòló | má} | ndàlá-í | l | ||||||||

| paper | on | draw-pst | nm | ||||||||

| ‘John drew pictures of himself.’ | |||||||||||

| c. | Kpànâj | {[tá | kpé]i/j | nὲnέ-í-sìà | gbá | kòlò | |||||

| Kpana | 3sg | self | shadow-def-pl | stuck | paper | ||||||

| má}k | l -í | l | [J ni | tìk | ndálá-nì | ||||||

| on | see-pst | nm | John | 3pl.rp | draw-pst | ||||||

| ‘Kpana saw pictures of himself that John drew.’ | |||||||||||

| d. | {[tá | kpé]i/j | nέnέ-í-sìà | gbá | kòlò | mà}k | |||||

| 3sg | self | shadow-def-pl | stuck | paper | on | ||||||

| mìà | Kpànâj | tìk | l -nì | [J ni | tìk | ndálá-nì] | |||||

| foc.l | Kpana | 3pl.rp | see-pst | John | 3pl.rp | draw-pst | |||||

| ‘It is pictures of himself that Kpana saw that John drew.’ | |||||||||||

Further evidence for the promotion analysis comes from quantifier scope. In (35a), it is scopally ambiguous. Under the subject wide scope reading, every boy works on a possibly different book (∀ > ∃). When the object takes a wide scope, this corresponds to a situation in which there is a particular book that every boy worked on (∃ > ∀). In (35b), the direct object of the RC-internal verb has been relativized (and the RC extraposed so that it follows the matrix verb). Crucially, (35b) is still scopally ambiguous. Specifically, ‘book’ can reconstruct into a relative clause and scope under the RC-internal subject. (The wide scope reading of ‘book’ would be expected from its surface position). Given the evidence from binding and quantifier scope, I conclude that the promotion analysis is on the right track for Mende.

| (35) | Quantifier scope | ||||||||

| a. | híndólópò | gbí | tí | k l | jèwé-í | l | |||

| boy | all | 3pl.sm | book | write-pst | nm | ||||

| ‘Every boy wrote a book.’ (√ A book x, such that every boy wrote x ∃ > ∀ √ Every boy x wrote a possibly different book y ∀ > ∃) | |||||||||

| b. | Kpànâ | k l | yèyá-í | l | [híndólòpò | gbí | tí | sèwè-nì] | |

| Kpana | book | buy-pst | nm | boy | all | 3pl.sm | write-pst | ||

| ‘Kpana bought a book that every boy wrote.’ (√ A book x, such that every boy wrote x ∃ > ∀ √ Every boy x wrote a possibly different book y ∀ > ∃) | |||||||||

4.2.2. Relative Clause Extraposition as Stranding

In order to more fully understand the process, in this section I explore the distribution of subject and object relative clauses in Mende. Crucially, I will argue that relative clauses always extrapose in Mende.

I begin by setting out in the following examples the position of object and subject- modifying relative clauses.12 In the object-modifying relative clauses in (36), the head of the RC functions as the direct object of the matrix clause. The DO/head of the RC surfaces pre-verbally, with the actual RC occurring post-verbally. In both (36a) and (36b), the subject marker in the RC agrees in number with the RC subject and in tense/aspect with the RC verb. In (36a), a subject relativizing clause, there is no resumptive pronoun for the head of the clause nyapuisia ‘the girls’, which surfaces as the clausal direct object above the verb, while in (36b), an object relativizing clause, the 3rd person plural resumptive pronoun ti surfaces in the canonical direct object position of the head of the RC.

| (36) | Object-modifying RC | ||||||||

| a. | Kpànâ | nyàpú-í-sìài | màlé-í | l | [ti | ||||

| Kpana | girl-def-pl | meet-pst | nm | ||||||

| tá | tέ-í-sìà | màjíà | wátí | gbí] | |||||

| 3pl.hab | chicken-def-pl | sell | time | all | |||||

| ‘Kpana met the girls who always sell the chickens.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Kpànâ | wátí | gbí | à | tέ-í-sìàj | vàwé | l | ||

| Kpana | time | all | 3sg.hab | chicken-def-pl | disturb | nm | |||

| [nyàpú-í-sìà | tí | tíj | yéyà-nì | nj p wá | hùn] | ||||

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | 3pl.rp | buy-pst | market | at | ||||

| ‘Kpana always disturbs the chickens that the girls bought at the market.’ | |||||||||

In (37a), a grammatical construction with a pre-verbal DP object and post-verbal modifying RC is shown, which I argue results from stranding. In (37b), it is shown that it is ungrammatical for the DP and RC to both surface pre-verbally, while (37c) shows that they cannot both follow the verb.

| (37) | Stranded RC modifier of a DP object | |||||||||||

| a. | Pìtá | nìké-í-sìài | mὲní-í | l | [nyàpú-í-sìà | tí | tíi | g k -nì] | ||||

| Peter | cow-def-pl | hear-pst | nm | girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | 3pl.rp | find-pst | |||||

| ‘Peter heard the cows that the girls found.’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | *Pìtá | nìké-í-sìài | [nyàpú-í-sìà | tí | tíi | g k -nì] | mὲní-í | l | ||||

| Peter | cow-def-pl | girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | 3pl.rp | find-pst | hear-pst | nm | |||||

| ‘Peter heard the cows that the girls found.’ | ||||||||||||

| c. | *Pìtá | mὲní-í | l | nike-i-siai | [nyàpú-í-sìà | tí | tíi | g k -nì] | ||||

| Peter | hear-pst | nm | cow-def-pl | girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | 3pl.rp | find-pst | |||||

| ‘Peter heard the cows that the girls found.’ | ||||||||||||

Consider next the data in (38), in which the Relative Clause CP can surface either in a position to the left or right of the aspectual adverb kpɔ ‘already.’ If the CP surfaces above the adverb, I assume that it has raised out of the verb phrase. In either case, the CP is stranded below the surface position of the verb.

| (38) | CP raising | |||||||||

| Pìtá | nìké-í-sìài | mὲní-í | l | {kp } | [nyàpú-í-sìà | tí | tíi | g k -nì] | {kp } | |

| Peter | cow-def-pl | hear-pst | nm | already | girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | 3pl.rp | find-pst | already | |

| ‘Peter already heard the cows that the girls found.’ | ||||||||||

The structure of an object-modifying relative clause is laid out in (39) with the source and surface position of the relativized constituent underlined. The head of the relative clause has raised into a pre-verbal position, while the relative clause CP is stranded.

| (39) | Object-modifying relative clause | |||

| S SM O V {X] [RC] {X} | ||||

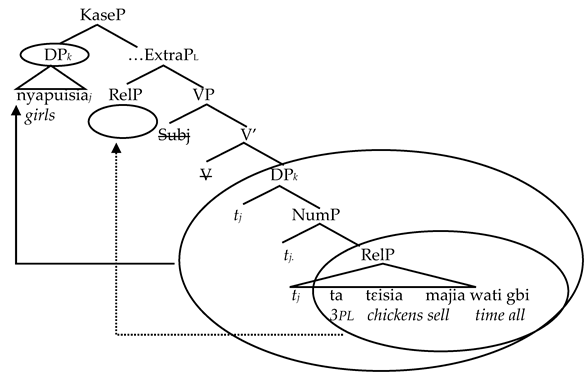

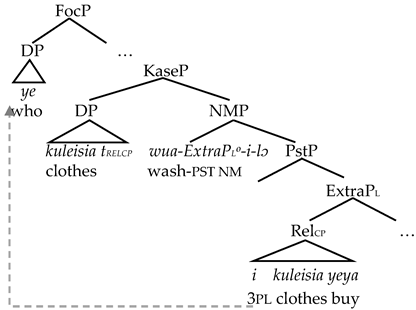

In the following example, I suggest a derivation for how the surface structure of a direct object-modifying relative clause surfaces in Mende. Consider (40), in which the head of the relative clause nyapu ‘girl’ merges within the relative CP. It raises through SpecCP and SpecRelP into SpecNumP then SpecDP. The CP portion of the relative clause, which is a constituent, subsequently raises into the specifier of the Extraposition Phrase.13 I refer to this extraposition phrase above the vP as ExtraPl. This leaves the derived DP to remnant movement, raising for Case into SpecKaseP.

| (40) | a. | Kpànâ | nyàpú-í-sìài | màlé-í | l | [ti | tá | tέ-í-sìà |

| Kpana | girl-def-pl | meet-pst | nm | 3pl.hab | chicken-def-pl | |||

| màjíà | wátí | gbí] | ||||||

| sell | time | all | ||||||

| ‘Kpana met the girls who always sell the chickens.’ | ||||||||

| b. | DP and CP Raising from an Object-Modifying Relative Clause | |||||||

| ||||||||

This analysis aligns with Kayne’s (1994, p. 121) proposal that relative clauses remain stranded in a non-Case marked position below the normal Case-marked positions, with the verb raising above this position, as well (c.f. Bianchi 1999).

I turn next to subject-modifying relative clauses. In (41), the head of the RC nyapuisia ‘the girls’ functions as the matrix subject. The modifying RC follows the subject and is in turn followed by the subject marker of the matrix clause. The direct object, verb, and any post-verbal material follow. Note in (41a), with a subject relativizing clause, that the subject marker in the RC ta agrees with the matrix subject (the promoted subject of the RC) and encodes habitual aspect. The matrix subject marker ti surfaces after the relative clause and agrees with the matrix subject. In (41b), with an object relativizing clause, the subject marker of the RC ti agrees with the number of the RC subject and the tense of the verb, while the clausal subject marker ta agrees in number with the matrix subject and in habitual aspect with the matrix verb. As expected, the resumptive pronoun ti occurs in the direct object position in the relative clause from which the clausal subject raised.

| (41) | Subject-modifying relative clauses | ||||||||

| a. | nyàpú-í-sìài | [ti | tá | tέ-í-sìà | màjíá | wátí | |||

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.hab | chicken-def-pl | sell | time | |||||

| gbí] | tí | Kpànâ | màlé-í | l | |||||

| all | 3pl.sm | Kpana | meet-pst | nm | |||||

| ‘The girls who always sell the chickens met Kpana.’ | |||||||||

| b. | tὲ-í-sìài | [nyàpú-í-sìà | tí | tíi | yèyà-nì | nj p wá | hùn] | ||

| chicken-def-pl | girl-def-pl | 3pl.sm | 3pl.rp | buy-pst | market | at | |||

| tá | Kpànâ | vàwé | l | wátí | gbí | ||||

| 3pl.hab | Kpana | disturb | nm | time | all | ||||

| ‘The chickens that the girls bought at the market always disturb Kpana.’ | |||||||||

Similar to object-modifying relative clauses, the head of a subject-modifying relative clause raises out of the clause into a higher position. Being the matrix subject, I argue that it raises into SpecFinP. The surface structure of a subject-modifying relative clause is laid out in (42).

| (42) | Subject-modifying relative clause |

| S [RC] SM O V {X} |

In (43), it is shown that an adverb can intervene between the subject and the relative clause, and I conclude that the DP and relative CP have split.

| (43) | Stranded RC modifier of subject | ||||||

| nyàpú-í-sìài | {kp } | [ti | tá | tὲ-í-sìà | màjíá | wátí | |

| girl-def-pl | already | 3pl.hab | chicken-def-pl | sell | time | ||

| gbí] | tí | Kpànâ | màlé-í | l | |||

| all | 3pl.sm | Kpana | meet-pst | nm | |||

| ‘The girls who always sell the chickens (already) met Kpana.’ | |||||||

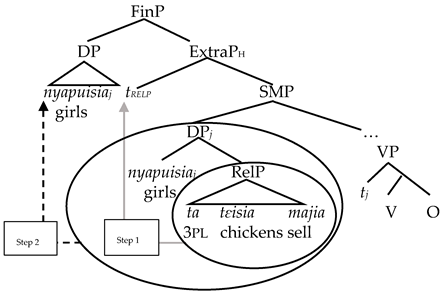

In this construction, the subject is in SpecFinP with the relative clause intervening between the subject nyapuisia and the matrix subject marker ti. I propose the following derivation (leaving out the adverb for simplicity). The DP subject (including the RC) raises from the vP into SpecSubjP, triggering agreement with the Subj head. At this point, similar to the object-modifying relative clause, the CP portion of the relative clause raises into an extraposition phrase (SpecExtraPh). The DP subject then raises into SpecFinP, yielding the surface word order.

| (44) | a. | nyàpú-í-sìài | [ti | tá | tέ-í-sìà | màjíá | wátí |

| girl-def-pl | 3pl.hab | chicken-def-pl | sell | time | |||

| gbí] | tí | Kpànâ | màlé-í | l | |||

| all | 3pl.sm | Kpana | meet-pst | nm | |||

| ‘The girls who always sell the chickens met Kpana.’ | |||||||

| b. | Derivation of subject-modifying RC | ||||||

| |||||||

In summary, I have shown a parallel process for both object- and subject-modifying relative clauses. In both instances, the CP portion of the relative clause raises into an extraposition phrase, leaving the DP portion to raise into its surface position (SpecKaseP for the object and SpecFinP for the subject). Baltin (1981, 2006) argues that constituents extraposed from subjects adjoin to IP, while constituents extraposed from objects adjoin to VP. He argues that an extraposed phrase adjoins to the first maximal phrase that dominates its phrase of origin (Baltin 2006, p. 241). While my analysis does not support this assertion, it does seem that in Mende the extraposition phrases are adjoined at the positions for which he argues.

4.2.3. Relative Clause Mixed Islands

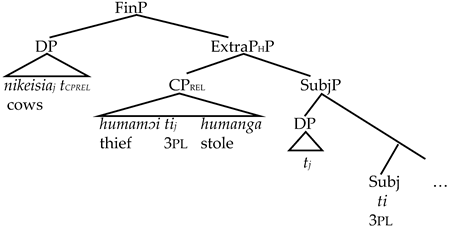

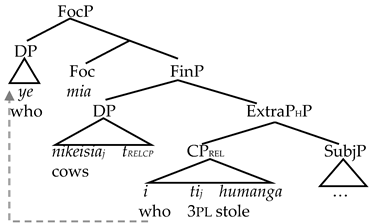

Having established the distribution of subject- and object-modifying relative clauses, I turn next to their status as mixed islands. Consider the subject-modifying relative clauses in (45), in which the head of the relative clause is promoted from within the clause to the matrix subject position. The DP (including the relative clause) raises to SpecSubjP, triggering agreement with the Subject Marker. The relative clause CP then raises into SpecExtraPh, while the matrix subject raises into SpecFinP.

| (45) | a. | nìké-í-sìài | [hùmám -í | tìi | hùmá-ngá] | tí | lùgbá-ì | l |

| cow-def-pl | thief-def | 3pl.sm | steal-prf | 3pl.sm | stumble-pst | nm | ||

| pὲlέ-í | hùn | |||||||

| road-def | on | |||||||

| ‘The cows that the thief stole stumbled on the road.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Subject-modifying RC | |||||||

| ||||||||

In this type of construction, the subject of the relative clause can be wh-questioned and move out of the relative clause and into the left peripheral focus position.

| (46) | yèi | míà | nìké-í-sìàj | [ìi | tìj | hùmá-ngá] |

| who | foc.l | cow-def-pl | 3sg.rp | 3pl.rp | steal-prf | |

| tíi | lùgbá-ní | pὲlὲ-í | hùn | |||

| 3pl.sm | stumble-pst | road-def | on | |||

| ‘Who is it that stole the cows that stumbled on the road?’ | ||||||

In (62), the wh-questioned subject of the relative clause moves into SpecFocP, with a resumptive pronoun surfacing in its pre-movement position. In this construction, the relative clause is not an island.

| (47) | Movement out of subject-modifying RC |

|

Consider next a subject-modifying RC (bracketed in (48a)) in an embedded clause (in curly brackets). In (48b), partial movement to the left periphery of the embedded clause is shown, while (48c) shows that wh-word can move to the clausal left periphery.

| (48) | Embedded clause with subject-modifying RC: partial and full movement | ||||||||

| a. | Mὲlí | mὲní-í | {kὲ | nìké-í-sìài | [hùmám -í | tíi | |||

| Mary | hear-pst | c | cow-def-pl | thief-def | 3pl.rp | ||||

| hùmá-ngá] | tí | lùgbá-ì | l | pὲlὲ-í | hùn} | ||||

| steal-prf | 3pl.sm | stumble-pst | nm | road-def | on | ||||

| ‘Mary heard that the cows that the thief stole stumbled on the road.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Mὲlí | mὲní-í | {kὲ | yèj | míà | nìké-í-sìài | [ìj | ||

| Mary | hear-pst | c | who | foc.l | cow-def-pl | 3sg.rp | |||

| tíi | hùmá-ngá] | tí | lúgbà-nì | pὲlὲ-í | hùn} | ||||

| 3pl.rp | steal-prf | 3pl.sm | stumble-pst | road-def | on | ||||

| ‘Mary heard that it was who that stole the cows that stumbled on the road?’ | |||||||||

| c. | yèj | míà | Mὲlí | mὲní-í | {kὲ | nìké-í-sìài | [ìj | ||

| who | foc.l | Mary | hear-pst | c | cow-def-pl | 3sg.rp | |||

| tìi | hùmá-ngá] | tí | lúgbà-nì | pὲlὲ-í | hùn} | ||||

| 3pl.rp | steal-prf | 3pl.sm | stumble-pst | road-def | on | ||||

| ‘Who is x such that Mary heard that x stole the cows that stumbled on the road?’ | |||||||||

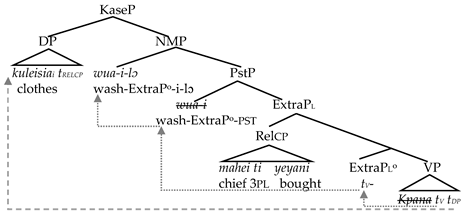

In contrast to the subject-modifying relative clause, movement out of an object-modifying relative clause is not sanctioned. As noted above, the DP head of an object-modifying relative clause obligatorily moves into a pre-verbal position for Case assignment.14 The relative CP moves into SpecExtraPl, remaining below the verb, as it does not need to raise for Case. This structure is shown in (49).

| (49) | a. | Kpànâ | [kúlé-í-sìà]i | wúá-ì | l | [màhé-í | tìi | yéyá-nì] |

| Kpana | cloth-def-pl | wash-pst | nm | chief-def | 3pl.rp | buy-pst | ||

| ‘Kpana washed the clothes that the chief bought.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Object-modifying relative clause | |||||||

| ||||||||

In contrast to subject-modifying clauses, movement out of an object-modifying relative clause is blocked, as seen in (50) with the analysis in (51). The head of the RC raises into SpecKaseP with the relative CP stranded in SpecExtraPl. In this construction, the relative clause is an island.

| (50) | *yèi | míà | Kpànâ | [kúlé-í-sìà]j | wúá-nì | [ìi | tìj | yéyá-nì] |

| who | foc.l | Kpana | cloth-def-pl | wash-pst | 3sg.rp | 3pl.rp | buy-pst | |

| ‘Who is it that Kpana washed the clothes that he bought?’ | ||||||||

| (51) | *Movement out of an object-modifying RC |

|

This same pattern occurs in partial- and full-movement constructions. In (52a), the verb mɛni ‘hear’ takes a CP complement (in curly brackets) containing an object-modifying relative clause (bracketed). Partial movement out of the relative clause to the embedded clause left periphery is blocked (52b), as is movement out of the RC to the matrix left periphery (52c).

| (52) | Embedded clause with an object-modifying RC: partial and full movement | ||||||

| a. | Mὲlí | mὲní-í | l | {kὲ | Kpànâ | [kúlé-í-sìà]i | |

| Mary | hear-pst | nm | c | Kpana | cloth-def-pl | ||

| wúá-ì | l | [màhé-í | tìi | yéyá-nì]} | |||

| wash-pst | nm | chief-def | 3pl.rp | buy-pst | |||

| ‘Mary heard that Kpana washed the clothes that the chief bought.’ | |||||||

| b. | *Mὲlí | mὲní-í | l | {kὲ | yèj | míà | |

| Mary | hear-pst | nm | c | who | foc.l | ||

| Kpànâ | [kúlé-í-sìà]i | wúá-nì | [ìj | tìi | yéyá-nì]} | ||

| Kpana | cloth-def-pl | wash-pst | 3sg.rp | 3pl.rp | buy-pst | ||

| Intended: Who is x such that Mary heard that Kpana washed the clothes that x bought? | |||||||

| c. | *yèi | míà | Mὲlí | mὲní-í | {kὲ | Kpànâ | |

| who | foc | Mary | hear-pst | c | Kpana | ||

| [kúlé-í-sìà]j | wúá-ì | l | [ìi | tìj | yéyá-nì]} | ||

| cloth-def-pl | wash-pst | nm | 3sg.rp | 3pl.rp | buy-pst | ||

| Intended: Who is x such that Mary heard that Kpana washed the clothes that x bought? | |||||||

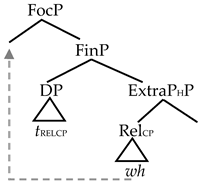

The previous data highlight an asymmetry between subject-modifying and object-modifying relative clauses in regards to their status as islands. While movement is possible out of subject-modifying relative clauses, it is blocked for object-modifying RCs. As such, I refer to them as mixed islands, since their status as an island is dependent on the position of the relative clause within the matrix clause. When the relative clause CP is in SpecExtraPh, which immediately dominates SubjP, extraction is possible. On the other hand, when it is in SpecExtraPl, movement is blocked.

In both cases, the relative clause is in SpecExtraP, and, as such, it is the position of the extraposition clause which determines whether movement out of the RC is permitted. This can be seen in comparing the structures in (53a), where the subject-modifying RC is in SpecExtraPh and (53b), where the object-modifying RC is in SpecExtraPl.

| (53) | a. | Subject-Modifying configuration |

| ||

| b. | Object-Modifying configuration | |

|

Extraction out of relative clauses has been indicated in the literature, particularly in African (Kandybowicz et al. 2021, 2023; Schurr et al. 2024; Murphy and Korsah, forthcoming) and Mainland Scandinavian languages (Engdahl 1997; Kush et al. 2013, 2019; Müller 2014, 2015). Studies indicate that there is an A-bar movement from relative clauses (Christensen and Nyvad 2014; Lindahl 2014, 2017, 2022), and there is consensus that relative clauses are weak islands in various languages, including Danish (Müller and Eggers 2022) and Swedish (Lindahl 2014), as well as English (Vincent et al. 2022) and Hebrew (Sichel 2018). However, acceptability ratings have been shown to be low (Poulsen 2008; Müller 2015, 2019). Factors such as the embedding verb (Erteschik-Shir 1973; Lindahl 2022), whether the sentence is existential or not (Kush et al. 2021; Lindahl 2022; Vincent et al. 2022), as well as the content of what is extracted (Müller and Eggers 2022) influence acceptability.

While both Mainland Scandinavian and Mende allow for extraction out of relative clauses, the contexts in which it is permitted vary. For Mainland Scandinavian, factors include the embedding verb, whether the clause is existential or not, and the content of what is fronted. In Mende, the factor seems to be syntactic. Movement out of subject-modifying RCs is sanctioned, and it is otherwise blocked. Mende does not fit the traditional notion of a weak island, in the sense that some phrase types can be moved out while others cannot (Szabolcsi and den Dikken 2002), and it therefore seems to represent a unique island variety cross-linguistically. Further research on other types of relative clauses in Mende, as well as the structure and distribution of relative clauses in other Mande languages might prove insightful.

In this section, I have sought to describe the structure and distribution of relative clauses in Mende. I have argued that they obligatorily raise, so that the head of the clause can move as a constituent into a higher position (either SpecKaseP or SpecFinP.) The relative clause raises first into SpecExtraP before the DP head of the clause remnant moves into its higher position. I have shown that while wh-movement is possible out of a subject-modifying RC, it is blocked out of object-modifying RCs. Therefore, subject-modifying RCs do not have the status of (strong/weak) islands in Mende.

5. Conclusions

The literature on island constraints has typically argued for a bifurcation—weak islands permit some types of extraction while strong islands categorically block it. In this paper, I argue for a third type of island, namely, mixed islands, where permeability seems to be conditioned by the syntactic position of the island.

Specifically, I propose that relative clauses are mixed islands: when they modify the subject, extraction is permitted; when they modify the object, extraction is blocked. I show how in both constructions the CP portion of the relative clause raises into the specifier of an Extra(position) P(hrase). The remaining DP portion then raises into a higher position (SpecFinP for subjects and SpecKaseP for objects). When the relative clause modifies the object, the ExtraP is indicated as ExtraPl, out of which wh-movement is blocked. When the relative clause modifies the subject, the ExtraP is indicated as ExtraPh, and wh-movement is sanctioned.

Beyond this distinction in extraction out of relative clauses, this paper makes several further contributions to research. First, it joins the other papers in this issue in contributing to the role of African languages in shaping the landscape of island research.

Second, it provides support for a promotion analysis of relative clauses from a language family that has thus far not been analyzed. By looking at reconstruction effects and the obligatory raising of the head, I have argued for a promotion analysis of relative clauses in Mende.

Third, these data have shown that resumptive pronouns do not play a role in ameliorating island violations. In some contexts, they allow for movement out of islands (e.g., subject-modifying RCs), while in other contexts they do not sanction movement (e.g., object-modifying RCs). As such, they do not line up with McCloskey’s (2017) assertion that resumptive pronouns are insensitive to constraints on movement.

Finally, it provides a detailed syntactic analysis of a Mande language, a family for which there is little research in the generative enterprise. As such, it highlights some syntactic characteristics of these understudied languages providing a basis for further research on subject markers, verbal complements, focus constructions, and the left periphery. Each of these areas warrants further study, not just in Mende, but in the broader Mande family.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by Michigan State University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

I thank two anonymous Languages reviewers for their feedback and questions which greatly improved this research. Thank you to my language consultants Lawrence Nyango and Saidu Challay. I am grateful to feedback from Harold Torrence, Deo Ngonyani, Jason Kandybowicz, and Komeil Ahari, as well as audiences at the 14th Annual Meeting of the Illinois Language and Linguistics Society and the Graduate Linguistics Expo at Michigan State (GLEAMS) where portions of this material were presented. Finally, I wish to thank the African Studies Center, The Graduate School, and The Linguistics Program at Michigan State University for funding this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In this paper, I use 3rd person plural objects as much as possible. In movement constructions, they are resumed by the pronoun ti. I use these constructions to make clear when movement has occurred, as the 3rd person singular non-human pronoun is null, while the 3rd person singular human pronoun is i or ngi. I also distinguish between resumptive pronouns, which are marked 3pl.rp and the plural subject marker, which is also ti (see Section 3.1 for analysis). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | In Mende, for example, subject markers do not appear in copular constructions or imperatives. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | See Sengova (1981) and Innes (1961) for additional information on the realization of (n)i. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | The neutral focus marker lɔ surfaces in many verbal constructions in Mende. When the in situ focus marker lɔ or the left peripheral focus marker mia occur in a phrase, it is ungrammatical for the neutral focus marker lɔ to surface.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | A reviewer pointed out that this analysis differs from Nikitina’s (2019) analysis of the position of PPs in the clausal structure of the Mande language Wan. It seems that Mende has a different structure from the data that she presents in the paper for other Mande languages. Consider the following Mende data.

The data she presents are exemplified by the following data from Mwan (for example, 3).

In Mende, the PP complement of the subordinate verb occurs in a post-verbal position immediately following the subordinate verb. This seems to contrast with the Mwan data in which the subordinate verb occurs prior to the main verb, while the subordinate verb’s PP modifier occurs in an extraposed position at the end of the clause. Based on this, I argue that the PP is much lower in Mende. Following Chomsky (1995) and Koopman and Sportiche (1991), I argue that the binding domain is the verb phrase, e.g., the verb and all of its arguments denote the Complete Functional Complex. In the Mende verb phrase, the DP object binds to the DP dative. It would seem, then, that underlyingly a ditransitive verb would take the direct object in its specifier and the dative object as its complement.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | I refer to this phrase ExtraPl (extraposition phrase low), as I argue later in Section 4.2.2. that there is also an extraposition phrase that occurs above the middle field (the traditional TP level) of the clausal structure, which I call ExtraPh. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Regressive vowel harmony yields yɔlɔ, and the intervocalic [l] is elided, yielding yɔɔ. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | There exists no detailed description or analysis of the functional structure in Mende DPs. Therefore, I leave the precise identity of FP2 for future research. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | This analysis is similar to Aboh’s (2004, pp. 110–114) ‘snowballing’ movement for Gungbe (Kwa) DPs. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Relative clauses have been discussed in the wider Mande literature. Correlatives have been discussed in a number of languages including Mwan (Perekhvalskaya 2007), Mandingo (Dramé 1981), Kakabe (Vydrina 2017), and Wan (Nikitina 2012). Bambara has correlatives, in addition to internally and externally headed relative clauses (Bird 1968; Zribi-Hertz and Hanne 1995). While Mende has correlative clauses, in this paper, I specifically consider externally headed relative clauses. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | These relative clause structures resemble wh-questioned subjects and objects in two ways. First, there is a prohibition against a neutral marker surfacing on the verb in relative clauses. Second, there is no resumptive pronoun for relativized subjects, as is the case for wh-moved subjects. These parallel processes point towards a movement analysis for relative clause constructions. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Relative clauses can surface in other positions (e.g., modifying datives or adjuncts), where they behave similarly to object-modifying relative clauses. For the sake of space, I focus only on subject- and object-modifying relative clauses. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | In Section 2.2, I noted that this extraposition phrase has been proposed for Avatime (Major and Torrence, forthcoming), Gugbe (Aboh 2004), and Dutch (Zwart 1997). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | The same pattern follows for dative and oblique-modifying relative clauses. The DP object moves into a pre-verbal position and the RC modifier remains stranded. The A-bar movement out of the RC is blocked. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Aboh, Enoch. 2004. The Morphosyntax of Complement-Head Sequences: Clause Structure and Word Order Patterns in Kwa. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aginsky, Ethel. 1935. A grammar of the Mende language. Language 11: 7–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltin, Mark. 1981. Strict Bounding. In The Logical Problem of Language Acquisition. Edited by Carl Baker and John McCarthy. Boston: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baltin, Mark. 2006. Extraposition. In The Blackwell Companion to Syntax. Edited by Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, vol. 2, pp. 237–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bearth, Thomas. 2009. Operator second and its variations in Mande languages. In The Verb and Related Areal Features in West Africa. Continuity and Discontinuity within and across Sprachbund Frontiers. Edited by Peter Zima, Radovan Síbrt, Mirka Holubová and Vladimír Tax. Munich: LINCOM, pp. 10–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Valentina. 1999. Consequences of Antisymmetry: Headed Relative Clauses. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, Charles. 1968. Relative clauses in Bambara. Journal of West African Languages 5: 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. 1982. A Mende Grammar with Tones. Bo: U.C.C. Literature Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna. 1997. Agreement and control in expletive constructions. Linguistic Inquiry 28: 521–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1977. On Wh-movement. In Formal Syntax. Edited by Peter Culicover, Thomas Wasow and Adrian Akmajian. New York: Academic Press, pp. 71–132. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Boston: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Ken, and Anne Nyvad. 2014. On the nature of escapable relative islands. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 37: 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 1993. A null theory of phrase and compound stress. Linguistic Inquiry 2: 239–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 1994. On the evidence for partial N-movement in the Romance DP. In Paths towards Universal Grammar. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque, Jan Koster, Jean-Yves Pollock, Luigi Rizzi and Raffaella Zanuttini. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and Functional Heads: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Chris. 2015. Relative clause deletion. In 50 Years Later: Reflections on Chomsky’s Aspects. Edited by Ángel J. Gallego and Dennis Ott. Cambridge: MIT Working Papers in Linguistics, pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Conteh, Patrick, Elizabeth Cowper, and Keren Rice. 1986. The environment for consonant mutation in Mende. Current Issues in African Linguistics 3: 107–16. [Google Scholar]

- Conteh, Patrick, Elizabeth Cowper, Deborah James, Keren Rice, and Michael Szamosi. 1983. A reanalysis of tone in Mende. Current Approaches to African Linguistics 2: 127–37. [Google Scholar]

- Creissels, Denis. 2019. Grammatical relations in Mandinka. In Argument Selectors. A New Perspective on Grammatical Relations. Edited by Alena Witzlack-Makarevich and Balthasar Bickel. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 301–48. [Google Scholar]

- Creissels, Denis. 2024. A Sketch of Mandinka. In The Oxford Guide to the Atlantic Languages of West Africa. Edited by Friederike Lüpke. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crisma, Paola. 1993. On Adjective Placement in Romance and Germanic Event Nominals. Rivista Di Grammatica Generativa 18: 61–100. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, Kenneth, and Ida Ward. 1944. An Introduction to the Study of Mende. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dingemanse, Mark. 2018. Redrawing the margins of language: Lessons from research on ideophones. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, Laura. 2019. Tumbuka prosody: Between tone and stress. In Theory and Description in African Linguistics: Selected Papers from the 47th Annual Conference on African Linguistics. Edited by Emily Clem, Peter Jenks and Hannah Sande. Berlin: Language Science Press, pp. 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dramé, Mallafe. 1981. Aspects of Mandingo grammar. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, David. 1969. Consonant mutation in Mende. Master’s thesis, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, David. 1971. Mende tone. Studies in African Linguistics 2: 117–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, David. 1978. What sort of tone language is Mende? Studies in African Linguistics 9: 167–208. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, David. 1981. A Reference Handbook of Lorma. East Lansing: Michigan State University. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard, David, Gary Simons, and Charles Fennig, eds. 2023. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 26th ed. Dallas: SIL International. [Google Scholar]

- Engdahl, Elisabet. 1997. Relative clause extractions in context. Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 60: 51–79. [Google Scholar]

- Erteschik-Shir, Nomi. 1973. On the Nature of Island Constraints. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, Justin. 2006. The Syntactic and Semantic Roots of Floating Quantification. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Fofana, Amadou, and Mamery Traoré. 2003. Bamankan Learners’ Reference Grammar. Binghamton: Global Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gensler, Orin. 1994. On reconstructing the syntagm S-Aux-OV-Other to Proto-Niger-Congo. In Twelfth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: Special Session on Historical Issues in African Linguistics. Berkely: Linguistic Society of America, Volume 20, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Georgi, Doreen, and Mary Amaechi. 2020. Resumption and islandhood in Igbo. Paper presented at the 50th Annual Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, Cambridge, MA, USA, October 25–27; pp. 261–74. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, John. 1976. Autosegmental Phonology. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, Jeffrey. 2017. A Grammar of Jalkunan (Mande, Burkina Faso). Electronic Publication. Language Description Heritage Library (MPI). [Google Scholar]

- Hein, Johannes, and Doreen Georgi. 2020. Asymmetries in Asante Twi A’-movement: On the role of noun type in resumption. Paper presented at the 51st Annual Meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, Montréal, QC, Canada, November 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, Gordon. 1961. The Structure of Sentences in Mende. London: University of London, School of African Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, Gordon. 1967. A Practical Introduction to Mende. London: Luzac. [Google Scholar]