Abstract

In this study, we report on results of a preliminary acoustic–phonetic analysis of the Hidatsa vowel system. We conducted acoustic measurements of Hidatsa vowels in terms of averaged temporal and spectral properties of these phones. Our durational analysis provides strong evidence that Hidatsa has a ten-vowel system with phonemically long and short vowels, in addition to two diphthongs. Our spectral measurements consisted of averages and time-evolution dynamic properties of the first three formants (F1, F2 and F3) at 30 equally spaced time points along the central portion of each vowel. The centers and distributions of the F1 and F2 formants, as well as their time-averaged trajectories, provide strong evidence for separate vowel qualities for both the short and long vowels. These measurements also show that all Hidatsa vowels have some degree of time-dependent spectral change, with the back vowels generally displaying a longer time-evolution track. Lastly, our results also indicate that in Hidatsa mid-short vowels do not appear with the same frequency as the other vowels, and that the short [é] has no unstressed counterpart.

1. Introduction

Hidatsa is a member of the Missouri Valley branch of the Siouan language family and is primarily spoken on and around the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota. They share this reservation with two other tribes, the Mandan and Arikara. Today they are known as the Three Affiliated Tribes. The modern reservation is a greatly reduced portion of the original Hidatsa lands. Historically, their life style was one of semi-sedentary horticulturists living in earth lodge villages close to the Missouri River and its northern tributaries, the Little Missouri and Knife Rivers. The Hidatsa utilized the river flood plains to grow garden crops, most notably corn, beans, squash and sunflowers. They also hunted in the adjoining upland grasslands for game, especially bison but also antelope and deer (Boyle 2007, pp. 1–2; Lehmer 2001, p. 248; Wood 2001, p. 188). Archeological evidence suggests that earth-lodge villages existed in this area as far back as 900 years ago (Wood 1986, p. 22, 2001, p. 186).

Hidatsa is an extremely endangered language with approximately 301 fluent native speakers, all of whom are over the age of 50. It is an agglutinating language with a wide variety of affixes which include a set of instrumentals, an active–stative pronominal system, causatives, a series of aspectual and tense markers, and a large number of illocutionary force markers (see Robinett 1955; Boyle 2007 and Park 2012 for a detailed description). These are all hallmarks of Siouan languages.

All researchers who have worked on Hidatsa have focused primarily on the morphology of the language and, more recently, its interaction with syntax (specifically Matthews (1965); Boyle (2007) and Park (2012)). No detailed study of the phonology of Hidatsa exists. Most descriptions claim that Hidatsa has a typical five-vowel system that shows contrastive length [i/iː, e/eː, a/aː, o/oː, u/uː] (Harris and Voegelin (in Lowie 1939), Robinett (1954, 1955), Matthews (1965), Jones (1978), and Boyle (2007)). Park (2012) argues that only the cardinal vowels [i/iː, a/aː, u/uː] are contrastive for length and the mid-vowels only have long members [eː, oː]. None of these studies have provided any phonetic evidence for these claims. They have all been based on impressions and perception of the linguist which is often influenced by their own first language. Bowers (1996) asserts that all vowels are phonemically short, but can be lengthened via various phonological processes. Bowers posits an underlying vowel system of [i, a, u] with a “lenis–fortis” distinction. While Bowers provides a few spectrograms of various Hidatsa words, it is unclear what exactly he means by this “lenis–fortis” distinction, but he states that it is not a length distinction. In addition, all authors claim there are two diphthongs, [ia] and [ua].

The aim of this study is to present a preliminary acoustic–phonetic analysis to determine the phonetic inventory of the vowels in Hidatsa as best as possible given the limitation imposed by language endangerment and the low number of speakers. While an acoustic–phonetic description of vowels in Crow was published in 2019 (Elvin et al. 2019), nothing similar exists for Hidatsa.2 In this paper, we argue that Hidatsa has two diphthongs and five long and short vowels that are clearly distinguishable by duration. However, while the long vowels show unambiguous separation when plotted in an F1–F2 vowel space, the short vowels are not as clearly separated in their respective vowel spaces, showing significant overlap when unstressed. In addition, the mid-vowels, particularly [e], have a severely restricted distribution. Much of the acoustic analysis with regards to procedure follows that done by Elvin et al. (2019). In the following section, we discuss where in our methodology we followed some of these procedures in detail.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The data used in this study were a subset of individual words recorded for a dictionary database project. The speakers who took part in that project were six female (Martha Birdbear, Mary Gachupin, Dora Gwin, Lila Gwin, Carol Maxwell and Arvela White) and three male (Delvin Driver Sr., Delvin Driver Jr. and Ed Lonefight) speakers.3 From this set we used a subset of recordings from three of the female speakers. The number of speakers from whom we could include data in this study was limited due to (1) the types of elicitations each consultant produced,4 (2) the number of tokens we could use for our analysis from different individual’s recordings and (3) the normalization procedures discussed below in Section 2.5. All are native speakers of Hidatsa and at the time of the recordings were between approximately 45 and 705 years old. As stated above, at the time of this writing, there are approximately 30 fluent people who speak Hidatsa as an L1. The nine speakers6 we worked with for this project constitute approximately 30% of the world’s Hidatsa speakers. All Hidatsa speakers are bilingual, also being fluent speakers of English. None reported speaking any other language, although some knew a number of words in Mandan and Spanish.

2.2. Vowel Tokens

The target words were obtained from a large-scale dictionary project that is comprised of approximately 5000 recorded words. The data were collected during fieldwork that occurred over the summers of 2015–2017.7 The recordings are of words in isolation, recorded in a foam-padded, quiet, isolated room. Equipment included a Shure microphone,8 pre-amplifier, and an AD conversion device to record directly onto a computer. Sessions were recorded using Audacity, set to a minimum sampling rate of 44.1 kHz.

For our analysis, we tried to select at least 20 words for each vowel from our larger database. These words contained at least one of the target vowels ([iː], [i], [eː], [e], [aː], [a], [oː], [o], [uː], [u]) or one of the two diphthongs ([ia], [ua]).9 This larger grouping of tokens was then divided into stressed and unstressed categories. This breakdown is shown in Tables 1 and 2 below. A word was considered a target word if it contained one of the 12 Hidatsa vowels or diphthongs surrounded by supra-laryngeal obstruents (preferably at least one of which was voiceless, e.g., [p], [t], [k], [š], [x]) produced in stressed and unstressed positions.

When choosing our examples, we wanted to restrict our selection to context where the vowel boundaries of the monophthong could be clearly identified. For this reason, we did not use words where the vowel was word initial or word final. When following or preceding a sonorant (particularly nasals), we had to make a decision on an individual token basis whether to include it or not. For example, if the nasal coarticulation was not significant, we kept the token in our study, but if the nasality spread into the vowel was significant (greater than 25% into the vowel) we discarded the token. It should be noted that nasals only occur word initially in Hidatsa. Approximately 8% of our tokens followed nasals. Furthermore, the voiceless aspirated stops are rare in Hidatsa. In addition, in some of the recordings, the signal-to-noise ratio was low, and in other instances recordings were simply clipped. For these reasons, our target pool of potential vowels shrinks dramatically from the 5000-word database. It should also be noted that the original purpose of these recordings was not for a phonetic study (see note 4), but this still remains the largest Hidatsa database in existence.

2.3. Stress Marking in Hidatsa

Stress marking is somewhat problematic in Hidatsa. All authors mark words with stress, but none ever define exactly what stress is. Harris and Voegelin (in Lowie 1939), Robinett (1954, 1955), Jones (1978) and Boyle (2007) all argue that it is lexical. Park (2012) proposes that Hidatsa has a pitch accent system similar to Crow. Rivera (2017) and Metzler (2021) have shown Park’s claims to be erroneous. In this study, we noted that in each word there is one syllable that is prominent (i.e., what we term stress). Metzler (2021) found that intensity and pitch are typically aligned, and when this occurs, this is the stressed syllable. For our current study of Hidatsa vowels, we followed Metzler (2021) and when intensity and pitch aligned, we marked that as the stressed syllable.10 When intensity and pitch did not line up on the same syllable, we marked the vowel with the highest intensity as the most prominent. If vowel intensity was very close on multiple syllables, we marked the vowel with the highest pitch as most prominent.

2.4. Acoustic Analysis

The start and end boundary of each vowel token was hand segmented by one of the four authors and then checked by another. For determining the boundary between voiceless obstruents and adjacent vowels, we used Praat’s (Boersma and Weenink 2023) track pitch feature, correlating the pitch tracks with the voicing bars in the accompanying spectrogram for visual verification. To differentiate vowels from voiced obstruents, changes in overall intensity along with declines in measurable F2 and F3 values were used for plosives, while the presence of high-frequency noise was used for identification of vowel-fricative boundaries. In some cases, we needed to segment vowels from nearby nasals. In such contexts, we relied on the general observation that nasal segments of speech have a lower amplitude than vowels (Ladefoged and Maddison 1996, pp. 102–9), and that this overall lower intensity also manifests in the form of significantly faded formant structures compared to adjacent vowels. Furthermore, the nasal segmentation for [m] and [n] is aided by the presence of a somewhat low intensity baseline formant bar at around 200 Hz. Tokens for which the nasal consonants resulted in significant passive co-articulatory nasalization of the adjacent vowels were not included in our datasets.

For obtaining formant measurements of the vowels, we used a Praat script which allows for manual verification of formant values at fifty equally spaced points along the length of the vowel. For each token, we discarded the first and last ten points obtaining F1, F2 and F3 for each token vowel at 30 equally spaced time points in the central portion (20–80%) of the vowel. These formant measurements were output into a file, transposed, and smoothed using a script in Matlab. The method employed was as follows: The 30 F1, F2, and F3 values for each measurement were discrete cosine transformed (DCT) in order to obtain a smooth characterization of the formants. The DCT produces a series of coefficients which are amplitudes of increasing frequency cosines making up the original sequence of formant values. There are 0th, 1st, 2nd, and higher order coefficients, each of which characterizes different aspects of the formant trajectories, with increasing coefficients capturing more detailed shapes of these trajectories. We followed insights from previous studies (Morrison 2013; Elvin et al. 2016) that the first and second DCT coefficients k0 and k1, respectively, are sufficient for characterizing smooth F1, F2, and F3 trajectory shapes in vowels.

2.5. Normalization

As stated in Section 2.1, the word list for the current study of Hidatsa vowels is based on tokens sampled from three different speakers. Given the general acoustic consequences of physiological differences between speakers, we found it necessary to try to partially factor out such inter-speaker variations so as to facilitate the comparison and representation of vowel measurements across our dataset. The factoring out of such differences is referred to as vowel normalization. For the current study, we adopted a vowel normalization model which uses a direct measure of average formant spacing (ΔF) to (a) estimate the vocal tract length for each speaker, and (b) remove the effect of vocal tract length differences from the formant measurements via a re-scaling of the F1, F2, F3 values by this ΔF factor (see Johnson 2020 for details).

3. Results

3.1. Duration

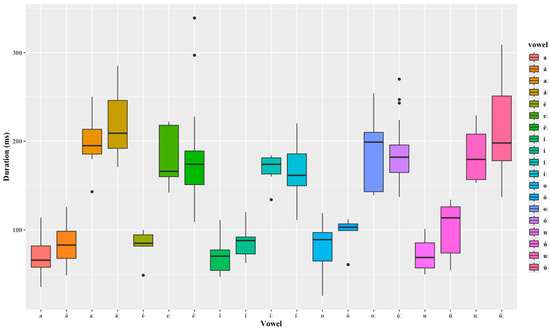

The average durations of the Hidatsa vowels are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Duration (in milliseconds) of long and short stressed and unstressed vowels in Hidatsa.

A clear length distinction can be observed for all five vowels between the long and short counterparts. We believe this offers conclusive evidence that Park’s (2012) and Bower’s (1996) claims of a reduced vowel inventory are incorrect. While the short mid-vowels do occur less often than the [i/iː], [a/aː] and [u/uː], and the front mid-vowel [e] has a restricted distribution which will be discussed below in Section 4, all five short vowels are accounted for. We also see that for the three corner vowels [i/iː], [a/aː] and [u/uː], the stressed counterpart, for both long and short, seems to have a slightly longer phonetic duration.

3.2. Formant Measurements

Table 1 shows the average values of the F1, F2, and F3 along with their standard deviation, (all in Hz) for the ten normalized unstressed Hidatsa vowels and Table 2 shows the average values of the F1, F2, and F3 along with their standard deviation, (all in Hz) for the ten normalized stressed Hidatsa vowels.

Table 1.

Average duration (ms) and F1, F2 and F3 values (in Hz) of normalized unstressed vowels. Standard deviations are provided in parentheses.

Table 2.

Average duration (ms) and F1, F2 and F3 values (in Hz) of normalized stressed vowels. Standard deviations are provided in parentheses.

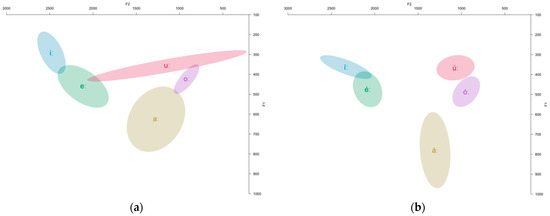

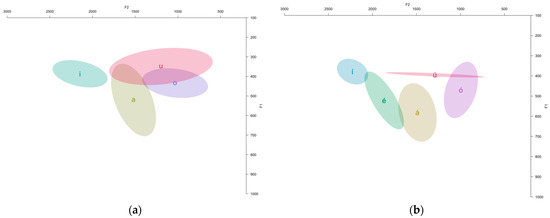

The plots in Figure 2a,b and Figure 3a,b display the mean values of F1 and F2 (indicated by the vowel character, for each vowel) in the F1–F2 plane. In the following Figures, the ovals are statistically created. Where the vowel character is written is the median average of the F1 and F2. The size, shape and orientation of the ellipsis is +/− one sample standard deviation along the major and minor axes. Ninety-five percent of all tokens for the given vowel fall inside its ellipsis. Figure 2a shows the unstressed long vowels, Figure 2b the stressed long vowels, Figure 3a the unstressed short vowels and Figure 3b the stressed short vowels. When stressed, each vowel becomes, on average, tighter and better defined within the space in terms of the spread of its (F1, F2) values. However, this is hard to see for the [a/aː] set of vowels. The stressed [á] seems to be a little more spread (less tight) in the vowel space with regards to F1. As can be observed, stress makes all of the vowels occupy a smaller, tighter, more prototypical11 vowel space.

Figure 2.

(a) F1 and F2 of Hidatsa normalized unstressed long vowels. (b) F1 and F2 of Hidatsa stressed normalized long vowels.

Figure 3.

(a) F1 and F2 of Hidatsa normalized unstressed short vowels. (b) F1 and F2 of Hidatsa stressed normalized short vowels.

Figure 2a shows the vowel space of the median average F1 and F2 values of the Hidatsa unstressed long vowels, whereas Figure 2b shows the vowel space of the median average F1 and F2 values of the Hidatsa stressed long vowels. Figure 3a shows the vowel space of the median average F1 and F2 values of the Hidatsa unstressed short vowels, whereas Figure 3b shows the vowel space of the median average F1 and F2 values of the Hidatsa stressed short vowels.

As can be observed, the long vowels show unambiguous separation, but this is even clearer when the vowel is stressed, although there is some overlap between the [íː] and [éː]. The short unstressed vowels show considerable overlap with the exception of the [i], although again, when stressed this overlap decreases markedly. Also, as can be seen in Figure 3a, there are no examples of the unstressed front mid-vowel [e]. This is a gap in the vowel inventory which is further discussed below.

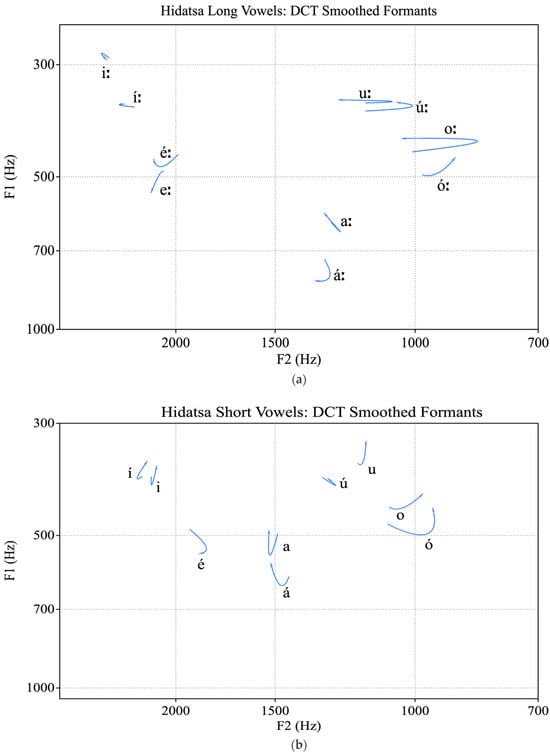

To determine how Hidatsa monophthongs change over time, we mapped the average F1 and F2 trajectories over the central portion of each vowel. The results of a DCT12 smoothed average formant trajectories for Hidatsa long and short vowels are shown in Figure 4a and b, respectively. The arrows in Figure 4a,b show the movement of the vowel from the first point measured until the thirtieth (the arrowhead).

Figure 4.

(a) Formant trajectories of the Hidatsa long vowels. (b) Formant trajectories of the Hidatsa short vowels.

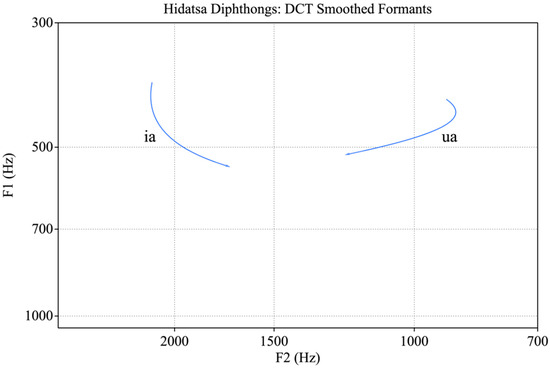

We next looked at the Hidatsa diphthongs’ trajectories. As with the monophthongs, we again calculated the DCT smoothed average F1 and F2 trajectories over the central portion of the diphthongs. The results for these are shown in the vowel space trajectory plot in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Acoustic plotting of the formant trajectories of the Hidatsa diphthongs.

Visual observation of the vowel plots shows some degree of formant movement in either F1, F2 or both. With regard to the long vowels, we see only slight movement in the high front vowel [iː/íː] whereas all the other vowels tend to show fronting, particularly with the [uː/úː] and the unstressed [oː]. The stressed [óː] shows only backwards movement and slight raising in the F1. The short vowels all show upwards movement, with the exception of the stressed [é] which moves downwards and then fronts. The two diphthongs behave exactly as we would expect, starting high and moving down and towards the central portion of the mouth. Unlike the findings of Elvin et al. (2019) for Crow, we see no overlap for any of the vowels. In addition, the vowels of Hidatsa are more spaced out, in comparison to Crow, although the [ú/u] and [úː/uː] are more fronted than might be expected for a cardinal [u].

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study is to present a preliminary acoustic analysis of the vowel system of Hidatsa and to determine the number and nature of those vowels. Following Elvin et al. (2019), we also employed a detailed DCT smoothed measure of spectral change (formant trajectories) to determine the dynamic properties that characterize these vowels.

Our duration analysis shows a clear length distinction among all five vowels, [iː]-[i], [eː]-[e], [aː]-[a], [oː]-[o] and [uː]-[u], counter to both Park’s (2012) and Bowers’s (1996) claims regarding gaps in the five-vowel system. Likewise, our formant measurements show a similar pattern. There is a clear separation of all the vowels offering more evidence that Hidatsa has a ten-vowel system. One interesting finding from this study is that long vowels tend to attract stress, and this gives us an asymmetry in the distribution of tokens for stressed and unstressed vowels. As a result, we have a larger number of tokens of stressed long vowels than unstressed long vowels and a larger number of unstressed short vowels than stressed short vowels. This introduces an unevenness in our sample, but it is consistent with Metzler (2021) in that Hidatsa has a quantitate sensitive stress pattern.

When we look at Figure 2a,b, Figure 3a,b, and Figure 4a,b, we see that the vowels do not always match phonetically with how they have been described in the previous literature. That is, as a five-vowel system as proposed by Harris and Voegelin (Lowie 1939), Robinett (1954, 1955), Matthews (1965), Jones (1978), and Boyle (2007)). Looking at the long vowels (Figure 2a,b), we see that the [iː/íː] are more or less where we would expect them to be, but that when stressed, the F1 and F2 distribution switch in the range of their values. In the unstressed [iː], the F1 has a greater range than the F2, but just the opposite occurs when the [íː] is stressed. The unstressed [eː] has a very large vowel space and could easily be represented with both the [eː] and [ɛː] vowel symbols. When stressed, this vowel narrows down to what we expect from [éː] in the vowel space. The [aː/áː] has an interesting distribution. When stressed, the range of this vowel’s F2 narrows. It might best be characterized as the vowel [ɐ́ː]. When unstressed, it shifts up and might be best characterized as [ɜː]. The [oː/óː] have a fairly standard distribution for what we would expect. The [uː/úː] vowel is very intriguing in Hidatsa (as is its short counterpart) with regards to the shape and orientation of its ellipsis. When unstressed, the [uː] has a wide distribution in its F2 whereas its F1 is fairly tight. This observation indicates that the phonetic quality of this vowel varies between [uː] and [ʉː] and may be even more fronted in its vowel space. We could not find any clear phonological conditions for this variation in the dataset we have. When stressed, the [úː] behaves more like we would expect it to, but it is still more fronted than the prototypical [úː].

When looking at the short vowels, we see a great deal of overlap in the unstressed [a], [o] and [u]. The unstressed [i] also has a wider range in its F2 than we might expect. It is also important to reiterate that there is no unstressed [e] in the data used in this study. While there may be unstressed [e]s in Hidatsa, if they do exist, they are extremely rare and none were found existing in the environments we examined. Graczky (2007) has proposed that the short mid-vowels in Crow have merged with their short high counterparts (that is, [e] has merged with [i], and [o] has merged with [u]). This is also what Park (2012) argued for Hidatsa, and while this may be a process that is occurring, we have clear examples of short stressed [é] as well as numerous tokens of both stressed [ó] and unstressed [o]. As stated above, stressed [é] has a very restricted distribution. The front mid-vowel only occurs as a stressed vowel before a geminate consonant.13 The unstressed [a] is really a [ə] as its vowel space is very central. Looking at the back vowels, we see considerable overlap between the [o] and [u]. This may be evidence of a merger in progress. Again, we see that the [u] has a great deal of variance in its F2, and like its long counterpart, might best be described as being realized both as [u] and [ʉ]. We could find no phonological conditions for this variation. When stressed, the short vowels disambiguate, although we still see some overlap in Figure 3b. The stressed [ú] flattens out like its unstressed long counterpart [uː] which is seen by its very narrow F1. The stressed [á] moves down a bit in the vowel space to a more prototypical low mid-vowel, but it still takes up considerable space in the central region of the mouth and seems to vary between [ɘ] and [ɐ].

Looking now at our analysis of spectral change in the formant trajectory shown in Figure 4a,b, we see movement in all of the Hidatsa vowels. Although this movement is not as dynamic as that reported for Crow vowels by Elvin et al. (2019), the monophthongs are still far from static in their F1 and F2s. The long [iː/íː] show the least amount of movement. In the [eː/éː], we see both dropping in their F1 and fronting in their F2. The stressed [éː] then raises in its F1 which distinguishes it from its unstressed counterpart. As already stated, the stressed [áː] starts at a lower F1 than its unstressed counterpart. Both [áː] and [aː] move forward in their F2, and the unstressed [aː] also raises in its F1. The back mid-vowels [oː/óː] act almost in opposition to their front counterparts [eː/éː]. The stressed [óː] moves up and back, whereas the unstressed [eː] moves down and forward. The unstressed [oː] moves back in its F2 and then forward, returning almost to its starting place. The unstressed and stressed [uː/úː] show the most movement of the long vowels. Both move back and then move forward. As stated above, neither of these long back vowels are as far back in the mouth as we might expect, giving us the vowel quality better represented by [ʉː/ʉ́ː].

The short vowels also show movement, but again less than Elvin et al. (2019) showed for Crow. The [i/í] vowels both raise. The short [é], unlike its long counterparts, moves back and down before slightly fronting. The short [a/á] both can clearly be seen as mid-central vowels. Both drop in F1 before fronting slightly and raising higher than their original starting point. This vowel really seems to be an [ə/ɘ́] in pronunciation. The short [o/ó] vowels both move back and up with a slight dip in the F1 of the stressed [ó] before raising upwards. Both the short [u/ú] vowels begin more forward than expected if they were prototypical high back vowels. Both move back slightly and then raise, with the greatest F1 change seen in the unstressed [u]. Again, this vowel seems best represented by the symbols [ʉ/ʉ́] as this is a much more central vowel than a typical [u].

The diphthongs [ia] and [ua] act just as expected. This can be seen in Figure 5. The [ia] starts high and front, then drops and moves back to a central position. This might be best represented by the vowel combination [ɪə]. Likewise, the [ua] starts high, moves slightly back, then drops and fronts. It is interesting to note that the first part of this diphthong starts further back in the mouth where we would expect the monophthong [u] to be positioned. Like its front counterpart, it too ends in the mid-region of the mouth. This might be best represented by the vowel combination [uə]. These findings are summarized below in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 3.

Hidatsa unstressed long vowels.

Table 4.

Hidatsa stressed long vowels.

Table 5.

Hidatsa unstressed short vowels.

Table 6.

Hidatsa stressed short vowels.

Table 7.

Hidatsa diphthongs.

5. Limitations

This study is a preliminary study. We hope that it encourages further research in this vein, not only for Hidatsa but other Siouan languages as well. We are keenly aware that by only having three participants in the study, it limits the amount of variation in the ability to apply statistical methods to account for the variation. As one of our reviewers pointed out, one of the main shortcomings of this paper is the lack of statistical modeling of the data. Because we have a limited number of speakers that represent a sizeable portion of the Hidatsa speaking population, the standard descriptive statistic may not be the best way to capture generalization about Hidatsa vowels. A future study should probably include something like a Bayesian approach for statistical inference in order to draw conclusions about the vowels of Hidatsa.

In addition, since our three consultants are from the same area on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation and are of the same generation, it limits our ability to examine potential variation across regions and generations that may exist in Hidatsa. In 1953, the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers built a series of dams along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. The Garrison dam was built several miles outside of the southeast corner of the Fort Berthold Indian reservation. The water behind the dam flooded most of the productive bottom land of the reservation which was where many tribal members lived. As people were forced to move, entire communities were destroyed (Schneider 2001, p. 396). Prior to the construction of the dam, most tribal members were multilingual, with Hidatsa and English being the common language among them. The construction of the Garrison Dam and the formation of Lake Sakakawea destroyed this community, with 90% of the Three Affiliated Tribes being forced to move. Communities and families that were once separated by a fordable river now found themselves cut off from each other by a huge lake (Boyle 2007, p. 12). Most Hidatsa speakers relocated to Mandaree, North Dakota, which is where our three consultants in this study now reside. So, while in the past, there may have been dialect variation, and we certainly know in the distant past there was, that may not be the case today given the small number of speakers. However, that being said, we realize this limits the conclusions we can reach.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, our acoustic analysis of the vowels in Hidatsa indicates that it is not like previous descriptions—that is, a typical five-vowel system that varies with length (Harris and Voegelin (in Lowie 1939), Robinett (1954, 1955), Matthews (1965), Jones (1978), and Boyle (2007)). We have shown that there are five long and five short vowels. The short unstressed vowels show a great deal of overlap with the exception of the [i], but when stressed, that overlap decreases dramatically and the vowel sounds that are produced are more prototypical. What has been described as a short [a/á] is really a central vowel better represented as [ə/ɘ́]. What has been described as a back high vowel is really more fronted than previously thought. This observation describes both the long and short vowels in both their stressed and unstressed forms. The quality of the high back vowel is better represented as an [ʉ]. The high back vowels are also unusual in that the long unstressed and short stressed members have a very narrow range for their F1 formants. Lastly, the diphthongs [ia] and [ua] behave as predicted with the caveat that the [a] is really a mid-central vowel.

As Hidatsa is a highly endangered language, it is important to use this study for language revitalization purposes. In the future, we can use the findings presented here as targets for vowel production by L2 learners. We could then examine the vowel spaces of these L2 speakers, which include both children in immersion programs and adults, and compare them to our findings to gauge how accurately learners are producing Hidatsa vowels. It would also be instructive to learn what kinds of changes are taking place as language revitalization programs move forward.

As this is the largest and most thorough phonetic description of vowels in a Siouan language, it can be used as a reference point for studies on other Siouan languages. With the exception of Crow (Elvin et al. 2019) and a small sub-study on Lakota (Mirzayan 2010), more acoustic–phonetic descriptions need to be done on the remaining spoken Siouan languages. This would allow us to accurately compare the vowels of these languages to each other and would thus facilitate a better understanding of how vowels in the different sub-branches have changed over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.B. and A.M.; methodology, J.P.B., J.D., A.M. and V.B.S.; field work and recordings, J.P.B. and A.M.; spectrograms, J.P.B., J.D., A.M. and V.B.S.; analysis, J.P.B., J.D., A.M. and V.B.S.; statistics, A.M. and V.B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.B.; writing—review and editing, J.P.B., J.D., A.M. and V.B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was carried out using data (recordings) collected by The Language Conservancy (TLC) during fieldwork conducted during the summers of 2015, 2016 and 2017. TLC was contracted by the Three Affiliated Tribes (Hidatsa, Mandan & Arikara) (TAT) to produce prelogical material. As this was a business contract between TLC and TAT there is no grant or funding number.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was given by all consultants involved in this project.

Data Availability Statement

The data is in the possession of the authors, The Language Conservancy and archived at The Nueta, Hidatsa, Sahnish College in New Town, North Dakota.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Bob Rugh and Elliot Thornton at The Language Conservancy for all their help in making the sound files used in this paper accessible. We would also like to thank Sean Fulop for his comments on an earlier draft of this paper as well as the three referees whose comments during the publication process were invaluable. Lastly and most importantly, we would like to thank the Hidatsa people for their wisdon, generosity and hospitaliy. Any mistakes are our own.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Hidatsa14 Word List

| Short unstressed [a] | Short stressed [á] | |||||

| a | aabaci | throat | á | aradáhshi | to tap the foot | |

| a | ababca15 | shrew | á | araxáhpi | to kick off of | |

| a | ababca | shrew | á | báhdahbi | to roll, roll over | |

| a | ágagitaa | to fail | á | bátagi | to knead | |

| a | ágagitaa | to fail | á | cagácgi | flea | |

| a | aradáhshi | to tap the foot | á | cagácgi | flea | |

| a | aradáhshi | to tap the foot | á | cáhdi | salve, ointment | |

| a | araxáhpi | to kick off of | á | dátahe | to mistreat | |

| a | báhdahbi | to roll over | á | háshicee | to provoke | |

| a | bashga | to poke something | á | idáxpe | to make someone nervous | |

| a | bátagi | to knead | á | ixbácgi | screech owl | |

| a | cagácgi | flea | á | ixbácgi | screech owl | |

| a | cagácgi | flea | á | nakápee | to blow away | |

| a | cíidahacgi | cougar | á | nakápee | to blow away | |

| a | cíidahacgi16 | cougar | á | sháhbua | seven | |

| a | dáhdahxi | to make a click | ||||

| a | dáhdahxi | to make a click | ||||

| a | dátahe | to mistreat | ||||

| a | gaccí | to extinguish | ||||

| a | habáadi | file | ||||

| a | íihcagi | to be alone | ||||

| a | kaccíi | to put the light out | ||||

| a | macagíria | arrogant | ||||

| a | nagapí | to pick out, select | ||||

| a | nagapí | to pick out, select | ||||

| a | nakápee | to blow away | ||||

| a | nakápee | to blow away | ||||

| a | napé | to elect | ||||

| a | naxbí | leather, hide | ||||

| Long unstresses [aː] | Long stressed [áː] | |||||

| aː | abádaaxi | to snore | áː | agudáaba | what kind | |

| aː | adaaté | to let someone out | áː | báahxu | to dump out | |

| aː | ahbaaxhí | cloud, sky | áː | dáaxi | grunt | |

| aː | ahbaaxhí | cloud, sky | áː | gáadi | real, true | |

| aː | arácaadi | to climb | áː | habáahba | to have chills | |

| aː | góoxaadi | corn | áː | iikáadi | tent peg | |

| aː | irúudaadi | a trigger | áː | itáaci | pants | |

| áː | itáaci | pants | ||||

| áː | náaga | calf | ||||

| áː | náaga | calf | ||||

| áː | nooháaga | in-laws | ||||

| áː | sháagi | hand | ||||

| áː | shigáaga | fellow, young man | ||||

| Short stressed [é] | ||||||

| é | adagéhgada | blackbird | ||||

| é | doʔhishéhbi | dark blue | ||||

| é | hishishéhpi | maroon | ||||

| é | íidashéhbi | blue roan | ||||

| é | néhba | belly button | ||||

| é | néhba | belly button | ||||

| é | shébishi | maroon | ||||

| é | shéhpi | dark, shadow | ||||

| Long unstresses [eː] | Long stressed [éː] | |||||

| eː | áraeexi | hold in the arms | éː | béericga | raven | |

| eː | aruréeʔeeca | all kinds or sorts | éː | céece | to hang from | |

| eː | aruréeʔeeca | all kinds or sorts | éː | céesha | wolf | |

| eː | garáceeda | to refuse | éː | gagéeki | to creak | |

| eː | húageebí | whooping cough | éː | giréeccee | to spend, use up | |

| eː | íaheeta | to mark something | éː | héeru | among | |

| eː | iceegí | heel of the foot | éː | ihgaréexi | star | |

| éː | macéecagi | a handsome man | ||||

| éː | miréete | to let in | ||||

| éː | muacéesha | wolf fish | ||||

| éː | néeccee | to use up | ||||

| éː | néeha | no | ||||

| Short unstressed [i] | Short stressed [í] | |||||

| i | aágixi | to urinate | í | aadíguda | parents | |

| i | áccisha | udder | í | abísha | liver | |

| i | arágici | singed | í | agagítaa | to fail | |

| i | arugigíhdi | dangerous | í | arugigíhdi | dangerous | |

| i | báhdihshi | to touch, nudge | í | gigíshgia | to examine | |

| i | báxishi | to scoop, shovel | í | guxíccee | to take by surprise | |

| i | cíicipiša | blacktail deer | í | híhshu | peppermint | |

| i | cíicipiša | blacktail deer | í | mikaaírutihge | hay baler | |

| i | gidáhe | slaughter | í | naxbícci | grizzly bear | |

| i | gidáhe | slaughter | ||||

| i | gigíshgia | to examine | ||||

| i | giréeccee | to spend, use up | ||||

| i | macidó | awl | ||||

| i | magibí | digging stick | ||||

| i | mashigá | chewing gum | ||||

| i | mikaaírutihge | hay baler | ||||

| i | mikaaírutihge | hay baler | ||||

| i | míruxipi | ice cream | ||||

| i | náhdihshi | to taste | ||||

| i | nihshá | a dance | ||||

| i | nóodishga | ghost | ||||

| i | úucica | weasel | ||||

| Long unstressed [iː] | Long stressed [íː] | |||||

| iː | áagciishi | to peek, peer | íː | aashíita | new antlers | |

| iː | abáariʔciida | porcupine tail comb | íː | abíicga | moustache | |

| iː | hiidá | fast, quick | íː | bacgíidi | to fit tight | |

| iː | hiidá | fast, quick | íː | cíicipiša | blacktail deer | |

| iː | hiidá | fast, quick | íː | cíidacgi | cougar | |

| iː | igikhiidá | to run fast | íː | cíitiru | tailbone | |

| íː | díiši | far, distant | ||||

| íː | híirahbi | complicated | ||||

| íː | híitaa | absent | ||||

| íː | miriʔíiwaxbi | sunset | ||||

| íː | shíiba | tripe | ||||

| íː | šíiri | brown | ||||

| íː | šíiši | to hiss | ||||

| Short unstressed [o] | Short stressed [ó] | |||||

| o | agodáari | to ford | ó | badóhdi | to shake, ruffle | |

| o | bóhorobe | to make round | ó | gohgógshi | chipmunk | |

| o | gohgógshi | chipmunk | ó | igóʔxba | friend | |

| o | hobíhe | to cut/drill a hole | ó | nagóxdi | light in weight | |

| o | íidohdi | plume | ó | nóhci | armpit | |

| o | íixoki | fox | ó | nóhshhi | chewed food | |

| o | íixokihishi | red fox | ||||

| o | nagadohdí | to shake something | ||||

| o | nágoxdi | light in weight | ||||

| o | núdoʔohdi | to sift | ||||

| o | núdoʔohdi | to sift | ||||

| Long unstressed [oː] | Long stressed [óː] | |||||

| oː | ígoogi | to be hanging | óː | abóoga | butterfly | |

| oː | doobá | four | óː | ahbóogsha | earring | |

| oː | gahgoorí | firm | óː | baxóoxi | to smooth a hide | |

| oː | nácoobi | kiss | óː | cóobi | to chirp, squeak | |

| oː | nóorooba | jaw | óː | cóoda | grey | |

| óː | cóoda | grey | ||||

| óː | góogii | companion | ||||

| óː | góoxaadi | corn | ||||

| óː | hicóogi | to be chilly | ||||

| óː | hóopaa | to go slowly | ||||

| óː | igóogi | hang something up | ||||

| óː | maaróoga | male elk | ||||

| óː | maaʔóote | a head-dress | ||||

| óː | móohcaa | coyote | ||||

| óː | naxóogi | to paddle, row | ||||

| óː | nóodishga | ghost | ||||

| óː | nóorooba | jaw | ||||

| óː | shóogi | blunt, dull | ||||

| óː | shóogi | blunt, dull | ||||

| óː | xaxóoxi | to breath nosily | ||||

| Short unstressed [u] | Short stressed [ú] | |||||

| u | aadíguda | parents | ú | aadigúda | family | |

| u | áaxuhga | kidney | ú | apúhga | cap | |

| u | barupee | shorten | ú | arúcaʔwi | prong | |

| u | buhí | speckled | ú | haxúdi | open by cutting | |

| u | gáxukee | to fool someone | ú | iirúhbaa | second | |

| u | gicugi | to thaw | ú | shirúhshi | to be greasy | |

| u | gukáa | at last, finally | ||||

| u | guxdí | to help someone | ||||

| u | íiguhba | to dislike | ||||

| u | mikaaírutihge | hay baler | ||||

| u | miribuhxi | beer | ||||

| u | míruxipi | ice cream | ||||

| u | náaxukee | saddle | ||||

| u | náaxukee | saddle | ||||

| Long unstressed [uː] | Long stressed [úː] | |||||

| uː | cúucuudi | slippery | úː | ahbúudi | back of the head | |

| uː | ibíidibuuxi | appaloosa | úː | arashúugi | to erase marks with the foot | |

| uː | máhbuushi | housefly | úː | búubudi | bubble | |

| uː | nagabuurí | to blow around | úː | búuxaga | sand | |

| úː | cúucuudi | slippery | ||||

| úː | gúuc | He fetches it. | ||||

| úː | ichúuba | shin | ||||

| úː | icúuga | Girl’s younger brother | ||||

| úː | icxúugi | feather | ||||

| úː | idúuxi | jacket | ||||

| úː | idúuxiihdia | parka | ||||

| úː | iibúuxi | gourd rattle | ||||

| úː | irigúudi | thigh | ||||

| úː | múubi | to smell | ||||

| úː | múubi | to smell | ||||

| úː | múubi | to smell | ||||

| úː | múubi | to smell | ||||

| [ia] diphthong | [ua] diphthong | |||||

| ia | bacgiríaʔooge | prickly pear | ua | awúaʔdi | sweat lodge | |

| ia | cíahe | cool down, extinguish | ua | cúada | brain | |

| ia | dibíarugarees | Parshall, ND | ua | cúahee | erect | |

| ia | gidiriáhge | to start a machine | ua | duáhgarug | when | |

| ia | giwiáhge | to drive back, repel | ua | dúahsha | heron | |

| ia | iihshíare | to forbid | ua | gúahee | to put back on | |

| ia | iihshíare | to forbid | ua | gúaxi | catch up with | |

| ia | iiragcíahee | to balance, weigh | ua | iigúahe | to get dressed | |

| ia | íiwiagsh | to cry | ua | ixuáhxa | knee | |

| ia | iríahi | to breathe | ua | ixúaʔihshi | clothes | |

| ia | maashíare | a dreamy | ua | ixuaʔíhshi17 | clothes | |

| ia | agihdíawa | very | ua | ixuaʔíiri | blood | |

| ia | magshíakaa | simultaneously | ua | maaʔíihuadi | a store | |

| ia | miáhdi | female transvestite | ua | macuáhca | sweet grass | |

| ia | míarahcaa | good girl | ua | mikáaduahisha | green | |

| ia | míaxde | jealous over a woman | ua | míruahee | boil | |

| ia | miritiáhgua | at a lake | ua | múaceesha | pike fish | |

| ia | aruʔóogciac | It will be dark. | ua | muaʔíshgi | fish scales | |

| ia | náhawiabiraga | thirty | ua | nuágsha | male animal | |

| ua | adicúahe | tepee | ||||

Notes

| 1 | This number is from a survey conducted on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation by Bernie Youngbird in 2023. The purpose of this survey was to help determine cultural and linguistic resources for the Maagarishda Hidatsa immersion program. Mrs. Youngbird shared the speaker number with the authors of this paper. |

| 2 | Crow and Hidatsa are the two languages that comprise the Missouri Valley branch of the Siouan language family, and while they are not mutually intelligible, they are closely related. Bowers (1965) and Wood (1986) state that according to tradition, there were three bands or villages of Hidatsa-speaking people. The largest were the Hidatsa proper, and the other two were the Awatíxa and the Awaxawi. The Crow seem to have split from these groups in two waves (Boyle 2007, p. 3). Wood (1986, p. 28) states that the Mountain Crow split from the Awatíxa in pre-contact times. Parks and Rankin (2001, p. 104) believe the split occurred approximately 600 years ago. Wood (1986, p. 28) then states that the River Crow split from the Hidatsa proper at a later date, although this was also in the pre-European contact period. |

| 3 | We name our consultants here as we believe it is very important to give them full credit for their participation in this project. All of our consultants feel strongly about this and have given us permission to do so. We feel this is important to do in the actual text of the paper and not relegate them to a footnote. It is an unfortunate consequence of colonialist and paternalistic racist attitudes that, in the past, many North American researchers in the fields of linguistics and anthropology failed to give credit to the many people who made their work possible. |

| 4 | This was a three-year-long project that had several priorities. The first was to create an online dictionary (https://dictionary.hidatsa.org/), the second was to gather narrative texts with specific cultural value, and the third was to help create pedagogical material. The consultants who worked on the vast majority of the dictionary portion of the project were Martha Birdbear, Mary Gachupin and to a lesser degree Arvela White. Carol Maxwell also participated in this portion of the project but only for a short time, hence we do not have many tokens from her. Delvin Driver Sr., Delvin Driver Jr. and Ed Lonefight produced a number of narrative recordings that were not used in this study as many of the text remain untranscribed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Martha Birdbear, Mary Gachupin, Dora Gwin and Lila Gwin helped to create pedagogical material which is currently in use in Hidatsa classroom throughout the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. |

| 5 | It is considered culturally inappropriate among the Hidatsa to ask someone their age, and while we have the birthdates of all of our consultants, we felt it was more respectful to just give a more general age range for them. |

| 6 | Delvin Driver Sr. and Ed Lonefight both passed away prior to the completion of this paper. All of our other consultants remain active in various documentation and revitalization projects on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. |

| 7 | This project was funded by a series of three language grants from The Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara), Ft. Berthold Indian Reservation, ND. |

| 8 | It should be noted that the exact distance between the speaker and the microphone could not be controlled for, and therefore, might not have been a constant. |

| 9 | We could not find 20 tokens of [e] and [o] because of the distribution of the short mid-vowels. |

| 10 | Metzler found that intensity and pitch aligned in 85% of the words he examined (Metzler 2021, pp. 23, 32). Using the same set of data we used for this study, he examined 279 recordings representing 176 unique words (Metzler 2021, p. 21). |

| 11 | We define a prototypical five-vowel system as the canonical vowels [i, e, a, o, u] that are equally spread and symmetrical. Typologically, these are the most common type of five-vowel systems found throughout the world’s languages (Velupillai 2012, p. 73). This is what all previous researchers have proposed for Hidatsa. |

| 12 | The procedure we employed followed Elvin et al. (2016). |

| 13 | Unlike Crow, Hidatsa has no geminate sonorants; only the obstruents can be geminates. We considered the hypothesis that the [é] may be an allophone of [éː] in that its environment is restricted to before geminates, but this is not the case. We have several examples of the long [eː] and [éː] also occurring before geminates. These are fairly rare, but we have examples of all the long vowels in this position (before geminates). These create super-heavy syllables. Graczky (2007) has reported that this also occurs in Crow. Distributional restrictions on the short mid-vowels and their interaction with the surrounding consonants have been reported for other Siouan languages as well; for instance, see Ullrich (2011, p. 752) for Lakota. |

| 14 | The words in this Appendix A are written in the Standard Hidatsa Orthography (SHO). We felt it was important to use the SHO rather than the IPA as we feel strongly that Hidatsa speakers and learners should see their language in an orthography they are familiar with. The <b, d, g> represent a plain series of stops [p, t, k] that voice to varying degrees intervocalically. The <p, t, k> are aspirated stops [pʰ, tʰ, kʰ] that never voice in any position. The affricates pattern with the stops. The <c> is the alveolar affricate [t͡s]. The <cc> is the aspirated variant, not a geminate. It is lengthened on the sibilant off-glide [t͡sʰ]. The <sh> is the alveopalatal fricative [ʃ] and the <x> is the velar fricative [x]. The clusters <hb, hd, hg, hc, hsh, hx> are geminates [pː, tː, kː, t͡ːs, ʃː, xː], with the affricate being lengthened on the stop on-glide. The sonorants <m, n, w, r> are their IPA equivalents, with the <r> being the alveolar tap [ɾ]. The <h> is an [h] and patterns with the sonorants. The <ʔ> is a glottal stop [ʔ]. |

| 15 | If a word had multiple entries (i.e., multiple recordings of the same word), we used the different recordings as individual tokens for our study. |

| 16 | If words had multiple tokens of the vowel, we used all possible tokens in the word. |

| 17 | Note that in this word the stress has shifted from the identical word above this one. This is a compound, and that may have caused the shift. |

References

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2023. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer program]. Version 6.4.01. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Bowers, Alfred W. 1965. Hidatsa social and ceremonial organization. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 194: 1–528. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, Norman. 1996. Hidatsa Suprasegmentals: A Phonological Analysis of a Siouan Native North American Language. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, John P. 2007. Hidatsa Morpho-Syntax and Clause Structure. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Elvin, Jaydene, Daniel Williams, and Paola Escudero. 2016. Dynamic acoustic properties of monophthongs and diphthongs in Western Sydney Australian English. Journal of the Acoustic Society of America 140: 576–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elvin, Jaydene, John Simonian, John Boyle, and Paola Escudero. 2019. An acoustic-phonetic description of vowels in Crow (Apsáalooke). In Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. Edited by Sasha Calhoun, Paola Escudero, Marija Tabain and Paul Warren. Canberra: Australasian Speech Science and Technology Association Inc., pp. 3598–601. [Google Scholar]

- Graczky, Randolph. 2007. A Grammar of Crow. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Keith. 2020. The ΔF method of vocal tract length normalization for vowels. Laboratory Phonology 11: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. Wesley. 1978. Hidatsa Writing for Hidatsa Speakers. Bismarck: North Dakota Indian Language Program, Mary College. [Google Scholar]

- Ladefoged, Peter, and Ian Maddieson. 1996. Sounds of the World’S Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmer, Donald J. 2001. Plains village traditions: Postcontact. In Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 13 (Plains), pt. 1. Edited by Raymond J. DeMallie. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Lowie, Robert H. 1939. Hidatsa Texts (with Grammatical Notes and Phonograph Transcriptions by Zellig Harris and C. F. Voegelin). (Prehistory research series 1:6). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, G. Hubert. 1965. Hidatsa Syntax. The Hague: Mouton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Metzler, Zachary Alan. 2021. Iambic intensity in Hidatsa. Master’s thesis, California State University, Fresno, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzayan, Armik. 2010. Lakota Intonation and Prosody. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Geoffrey S. 2013. Theories of vowel inherent spectral change. In Vowel Inherent Spectral Change. Edited by Geoffrey S. Morrison and Peter F. Assmann. Berlin: Springer, pp. 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Indrek. 2012. A Grammar of Hidatsa. Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Parks, Douglas R., and Robert L. Rankin. 2001. Siouan languages. In Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 13 (Plains), pt. 1. Edited by Raymond J. DeMallie. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, Amanda Leigh. 2017. Metrical Prominence in Hidatsa: An Acoustic and Phonological Analysis. Master’s thesis, California State University, Fresno, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Robinett, Florence M. 1954. Hidatsa Grammar. Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Robinett, Florence M. 1955. Hidatsa I: Morphophonemics, Hidatsa II: Affixes, and Hidatsa III: Stems and themes. International Journal of American Linguistic 21: 1–7, 160–77, 210–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Mary Jane. 2001. Three affiliated tribes. In Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 13 (Plains), pt. 1. Edited by Raymond J. DeMallie. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, Jan. 2011. New Lakota Dictionary. Bloomington: Lakota Language Consortium. [Google Scholar]

- Velupillai, Viveka. 2012. An Introduction to Linguistics Typology. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, W. Raymond. 1986. The Origins of the Hidatsa Indians: A Review of the Ethnohistorical and Traditional Data. Reprints in Anthropology. Lincoln: National Park Service, Midwest Archeological Center, vol. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, W. Raymond. 2001. Plains village tradition: Middle Missouri. In Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 13 (Plains), pt. 1. Edited by Raymond J. DeMallie. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).