1. Introduction

Prosody contributes significantly to our understanding of pragmatic meaning, as utterances can be interpreted in various ways depending on their prosodic features (

Escandell-Vidal and Prieto 2020;

Wichmann and Blakemore 2006). Speakers’ phonological choices provide important contextual information beyond the literal word meaning, including focus or information status, illocutionary force, and affective meaning (

Cole 2015). Studies on conversational humor, especially those focusing on verbal irony, have addressed this phenomenon as an intersection between prosody and pragmatics because ironic utterances, which are characterized by being humorous and indirect (i.e., often involving saying something different than what is meant), vary significantly from non-ironic utterances in terms of rhythm, duration, pitch (F0), amplitude, and voice quality (

Bryant 2010).

Verbal irony is a form of conversational humor that is recognized as mockery by the audience (

Goddard 2018) and involves an inconsistency or contrast between a verbal expression and a situation in which a speaker “directly refers to prior statements, predictions, expectations, or desires in the midst of the current situation that violates those statements” (

Colston 2000, p. 98). Such discrepancy between expectation and reality is conducive to a good feeling or laughter, and serves a variety of pragmatic functions, including mitigating criticism or conveying solidarity (

Davies 2004;

Gibbs 2000;

Gibbs and Colston 2007). From a sociocultural perspective, research has also identified that verbal irony can manifest and be interpreted differently based on factors such as the interlocutors’ common ground, social distance, gender, and occupation (

Colston and Lee 2004;

Dews et al. 1995;

Gibbs 2000;

Jorgensen 1996;

Lee and Katz 1993;

Katz and Pexman 1997;

Kreuz and Link 2002;

Pexman et al. 2000;

Pexman and Olineck 2002;

Pexman and Zvaigzne 2009).

The aim of the present paper is to contribute to scholarship on the prosody–pragmatics interface and examine how prosody in female talk contributes to the creation of pragmatic meaning of verbal irony in Spanish. That is, this paper offers an acoustic analysis of a pragmatic phenomenon. Our study examines naturally occurring ironic utterances in the casual speech of 15 Chilean women residents of La Pintana, a low-income Santiago neighborhood. The conversations revolved primarily around relationships with friends and family members and talk about the local community, with the aim of eliciting vernacular speech for an unrelated project. However, topics such as neighborhood-based discrimination and drug addiction and violence in the community also arose spontaneously. In this paper, we examine the frequency of the subtypes of verbal irony in our data, namely jocularity, rhetorical questions, understatements, hyperbole, and sarcasm (following

Gibbs 2000), and provide a detailed analysis of how each subtype manifests prosodically in contrast to the speech that comes before it.

Though this paper does not compare the use of verbal irony across genders or levels of social distance and status, our findings are representative of conversations between unacquainted women (i.e., interviewer and interviewees). Thus, we would also like to acknowledge up front the positionality of the interviewer (the first author) and the interviewees. Specifically, the interviewer was a white, cisgender, L1 English speaker from the United States, who was privileged to speak to these women during fieldwork in 2015. As we describe later in this paper, the women belong to a marginalized community: they are women of color and find themselves in a precarious socioeconomic situation. Though they received payment in return for their participation, we acknowledge that this interview structure was inherently unequal.

Surprisingly, studies of the prosody–pragmatics interface are relatively uncommon in Spanish, a language which is known to use intonation largely for pragmatic purposes, as suggested by

Regan (

2016, p. 212). By focusing on Spanish, we address this significant gap in the literature. Furthermore, we chose to work with Chilean Spanish because its prosody is fairly understudied in spite of its unique intonation patterns, such as the “hat patterns” or “intonational plateaus” noted by

Rogers (

2013) and

Rogers et al. (

2020). Similarly, little is known about the other prosodic features of this Spanish dialect (

Peralta 2021). Additionally, the Chilean dialect that is often represented in linguistics research focuses on the normative variety. Other voices, such as those from marginalized communities in the Chilean capital city outskirts, are invisible. Finally, while scholars working in pragmatics are aware of the important contribution of prosody, to our knowledge, no study has teased apart the different manifestations of irony and characterized the acoustic properties of each type. Our approach to the study of irony enabled us to uncover subtle differences within this phenomenon at the discursive and suprasegmental levels from within naturally occurring instances of irony.

3. The Study

Our study is similar in many respects to

Bryant (

2010), such as, for example, including the five irony subtypes proposed by

Gibbs (

2000). However, it differs in three important ways. First, instead of conversational dyads among friends, our data derive from casual conversations via informal sociolinguistic interviews, in which the interviewer and the interviewees were unacquainted. Second, our data derive from conversations in Chilean Spanish, allowing us to contribute to the body of work on the prosody–pragmatics interface in Spanish. Third, we examined more acoustic features than

Bryant (

2010), such as voice and vowel quality, to potentially discover additional systematic correlations between prosody and irony in Spanish (cf.

Escandell-Vidal and Prieto 2020, p. 157).

To identify the most prevalent subtypes of irony and to determine what prosodic correlates of irony are obtained in Chilean Spanish, our study examined verbal irony in the casual speech of 15 female lifelong residents of the La Pintana neighborhood in Santiago, Chile. The research questions that guided our study were the following:

Which of the subtypes of irony (jocularity, rhetorical questions, hyperbole, understatements, and sarcasm) occur in our Chilean Spanish data?

How are these subtypes conveyed prosodically?

We posit that jocularity will be the most common form of irony in our data. Even though many studies on irony have generally suggested that sarcasm is the most common subtype in oral discourse (as noted by

Gibbs 2000), we predict that given the nature of our speech sample, which involved an informal, conversational tone between two unacquainted women (interviewer and interviewee), sarcasm and the critical tone that accompanies this subtype might not be the one that arises the most in our data. In contrast, and following

Gibbs (

2000) and

Brown and Levinson (

1987), we expect that jocularity will be used as a mechanism that brings the speaker and the hearer closer together, allowing them to discuss serious real-life events with a touch of humor. We acknowledge that the interviewer is a foreigner from a privileged racial group, and an L2 Spanish speaker, who is not from the immediate local community. Thus, because the interviewer is an outsider in the community in multiple ways, this might affect the way in which irony is used.

The second hypothesis states that ironic utterances will be prosodically differentiated from non-ironic utterances via several measures. First, we expect longer syllable durations in all ironic utterances (cf.

Bryant 2010). We also expect lower F0 (

Rao 2013;

Cheang and Pell 2008;

Attardo et al. 2003) and differences in voice quality (

Niebuhr 2014;

Cheang and Pell 2008) in sarcastic utterances. Rhetorical questions are one of the subtypes of speech acts used by

Gazdik (

2022) in her examination of the use of the tag question

¿No? in Peninsular Spanish, and the author finds that nearly all occurrences of

¿No? as a tag question use a rising contour. For this reason, we expect to observe rising intonation (increased F0 toward the end of the utterance) in rhetorical question irony types. As previous work in Spanish has not explicitly included other irony subtypes, we generally expect that we may find differences along each of the five acoustic measures examined here (F0, F0 range, syllable duration, and two measures of voice quality, namely H1*–H2* and HNR, explained below). We also expect that some of these measures may overlap. That is, given that humor may be signaled in myriad ways, it is possible that the same measures may act in similar ways across different types of verbally ironic utterances, since prosody is a paralinguistic feature that “helps speakers communicate a wide array of affect and intentions” (

Bryant 2010, p. 548).

5. Analysis and Results

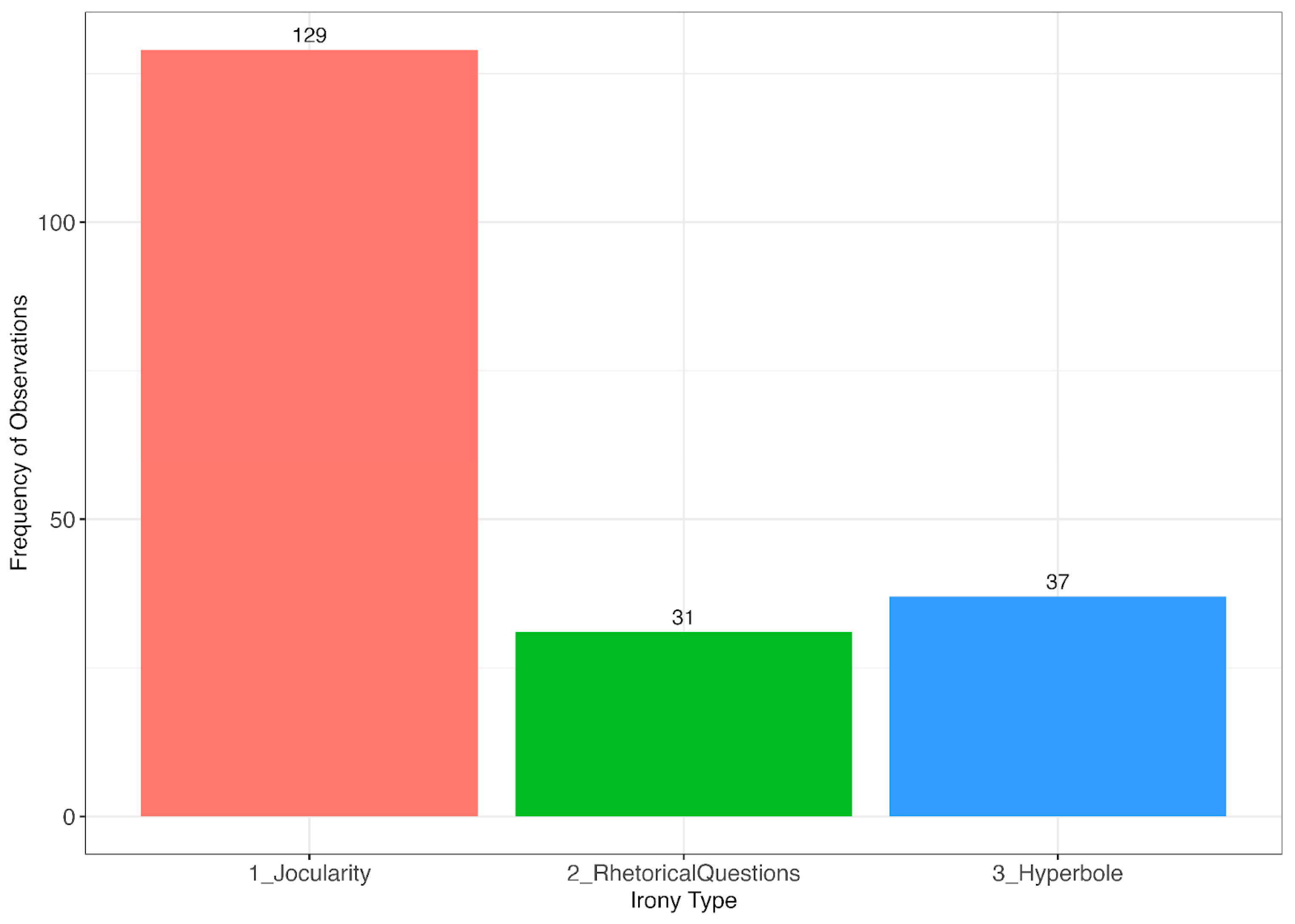

The participants produced a total of 197 ironic utterances, with an average of 13.06 ironic utterances per speaker (ranging from 3 to 30 per speaker; SD = 7.41). In response to research question one which asked which of the subtypes of irony occurred in our data, we found that 66% of the ironic utterances produced were coded as jocularity, described by

Gibbs (

2000) as playful ironic teasing. Approximately 16% of the data were comprised of rhetorical questions, while hyperbolic utterances represented 19% of the utterances. This difference is represented visually in

Figure 1. Interestingly, the speakers did not produce any instances of understatements or of sarcasm.

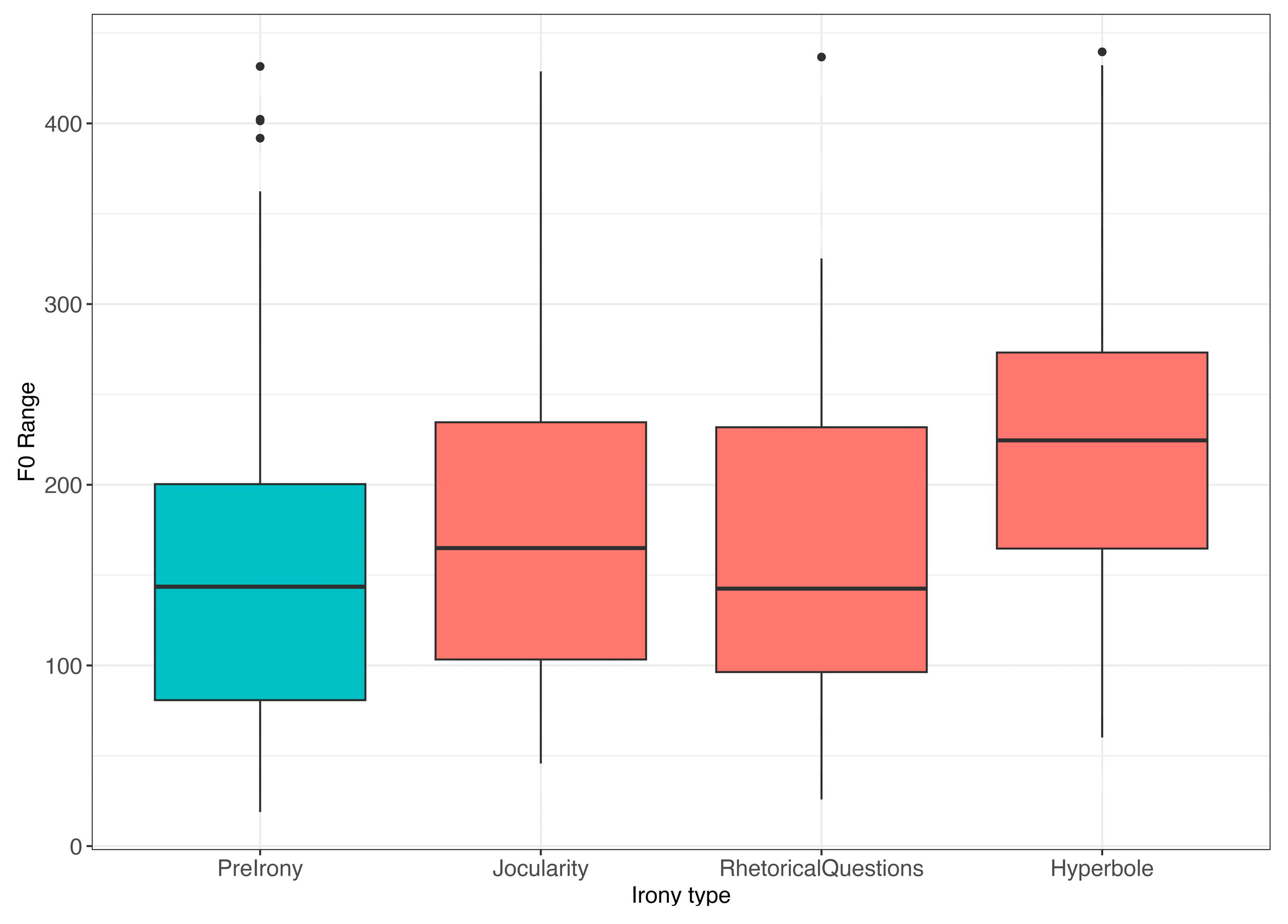

5.1. Pitch Range

A linear mixed model, taking F0 range as the dependent variable and the speaker age and irony type as the independent variables, showed that two irony categories resulted in a wider pitch range as compared to pre-ironic utterances: jocularity and hyperbole. These differences are visualized in

Figure 2, with the model summary presented in

Table 2.

There were no significant differences in pitch range for the rhetorical questions irony type as compared to the pre-ironic baseline utterances, and no significant differences according to the speakers’ age.

5.2. Jocularity

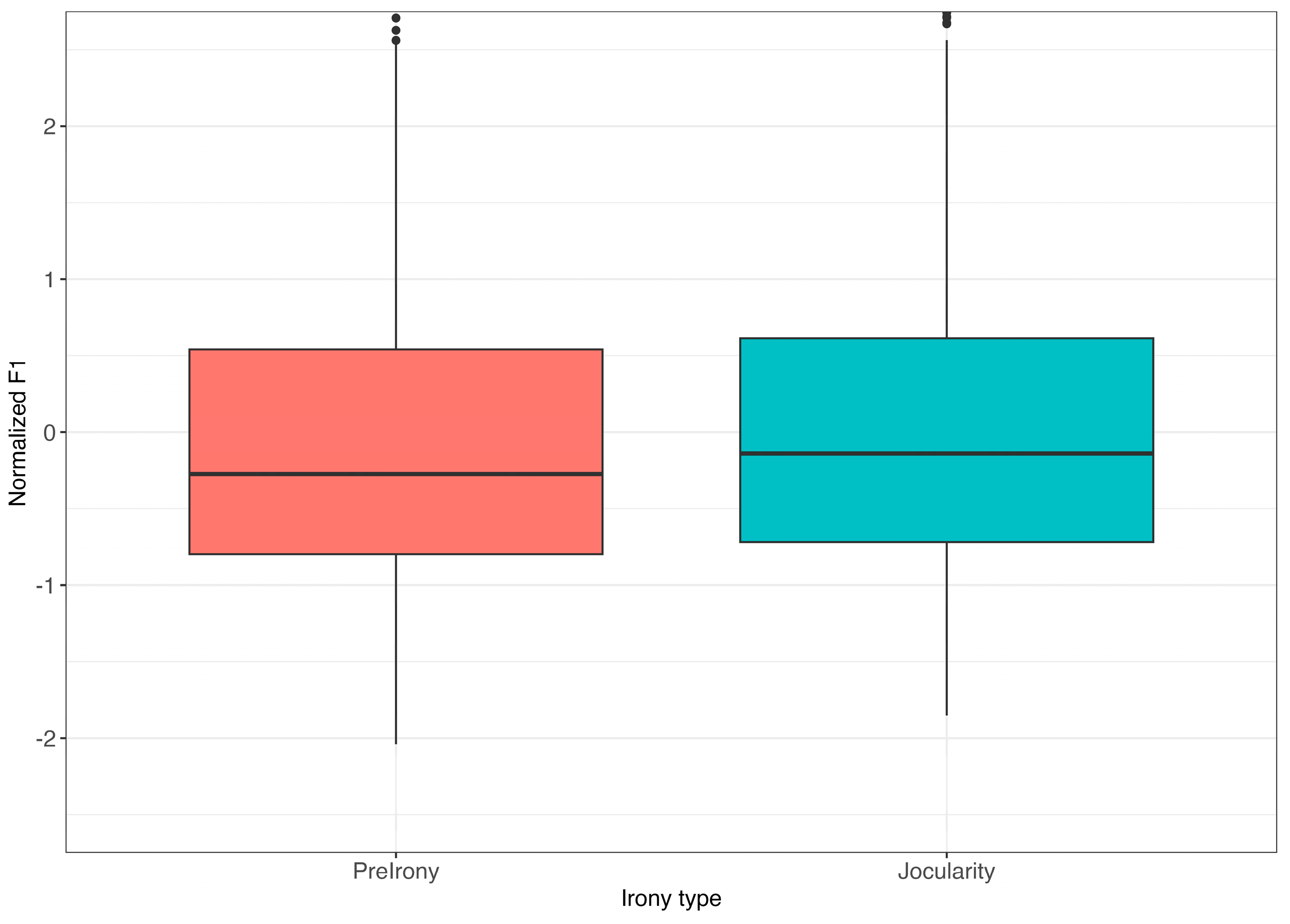

For the first six linear models taking the acoustic and prosodic measures as dependent variables, we first subset the data into only jocular irony utterances and their corresponding pre-ironic utterances (n = 2480). In the first model, taking F0 as the dependent variable, only the ratio variable significantly contributes to the outcome. Specifically, this finding demonstrates that the pitch increases over the utterance in both pre-ironic and ironic utterances. No other predictors in this model significantly affected the outcome of the pitch variable, including whether the syllable was located in the pre-ironic baseline utterance or in the jocular irony utterance.

The second model taking F1 as the dependent variable shows that jocular irony vowels have a significantly higher F1 than the vowels in the pre-ironic baseline utterances. That is, when speakers produced jocular irony utterances, they did so with significantly higher F1s (lowered vowels; consistent across all five vowels). This effect is visualized in

Figure 3, below.

Additionally, as expected, F1 significantly differs according to the vowel’s identity. Vowels’ F1s also differ according to stress: stressed vowels have a significantly higher F1 (are lowered).

The model taking F2 as the dependent variable shows that, as expected, F2 significantly differs according to the vowel identity. However, there were no differences in F2 according to the irony type.

Only the ratio variable significantly conditioned H1*–H2*. That is, as the ratio increased (signaling syllables later in the utterance), H1*–H2* decreased. Decreased H1*-H2* is associated with creakier phonation, providing additional evidence for increased creaky voice toward the end of utterances.

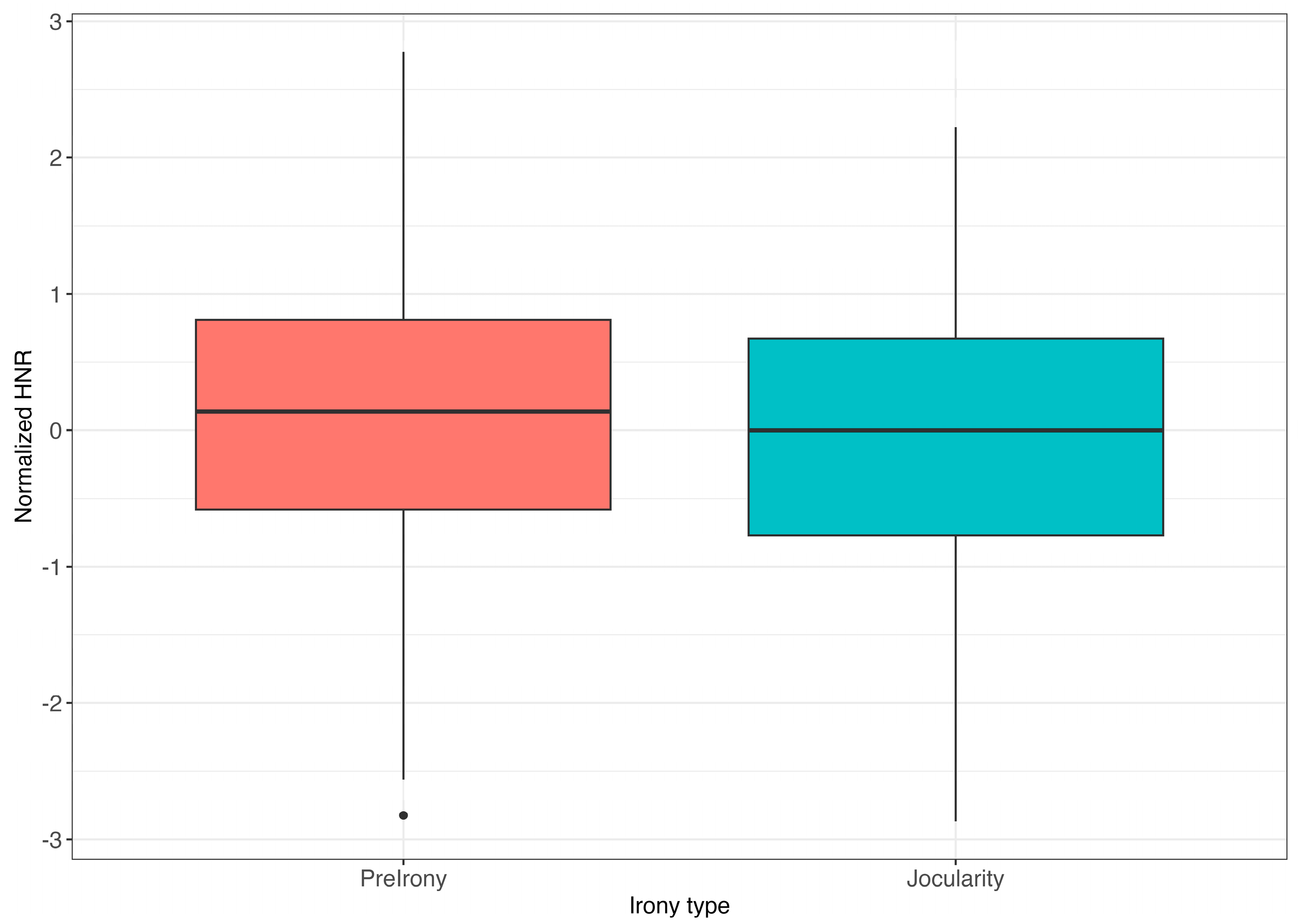

According to the model taking normalized HNR as the dependent variable, irony category, vowel, and ratio significantly affect HNR. The best-fit model summary is shown in

Table 3, below. Similar to the results from the H1*–H2* model, as ratio increased, HNR decreased. This suggests that syllables produced later in the utterance are noisier (i.e., less modally voiced) in both pre-ironic utterances and in jocular irony utterances. There were also significant differences in HNR according to the identity of the syllable nucleus (i.e., the vowel).

Importantly, there was also a significant difference according to the irony category. That is, the syllables produced within jocular irony utterances had a significantly lower HNR than syllables produced in the pre-ironic utterances, indicating increased noise. This difference is represented visually in

Figure 4.

Finally, in the model taking duration as the dependent variable, only the identity of the vowel and stress affected duration in expected ways. Certain vowels were longer than others, and stressed vowels were significantly longer than unstressed vowels. There were no effects for the irony type, signaling that there were no differences in duration based on whether the syllables were found in the pre-ironic baseline utterances or the jocular irony utterances.

In sum, only HNR was found to be significantly different between the jocular irony utterances as compared to the pre-ironic baseline.

5.3. Hyperbole

We then created a subset of the data comprised of only the syllables from the hyperbolic irony utterances and the corresponding syllables from the pre-ironic utterances (n = 830). According to the best-fit model taking F0 as the dependent variable, only syllable stress and ratio significantly affected the outcome. That is, stressed syllables were associated with a significantly higher pitch, as were the syllables farther along in the utterance (i.e., there was increased pitch over later syllables in the utterance), for both the pre-hyperbolic and hyperbolic utterances. No results were found for the hyperbolic irony type as compared to the pre-ironic baseline, signaling that there is no difference in pitch in the syllables in the hyperbolic utterances as compared to the baseline.

According to the best-fit model taking F1 as the dependent variable, only the syllable stress and vowel identity significantly affected the outcome variable. That is, as expected, the identity of the vowel significantly affected the value of the vowel’s F1. Additionally, stressed vowels were produced with a significantly higher F1 (or as lowered in the vowel space).

Similarly, the vowel identity affected the outcome of the model taking F2 as the dependent variable. That is, as expected, there is a significant difference between a vowel’s F2 and its identity. Additionally, there was an effect for the ratio predictor: over the course of both the hyperbolic irony and baseline types of utterances, speakers produced their syllables with a decreased F2.

The results of the best-fit model, taking H1*–H2* as the dependent variable, also showed effects for ratio and syllable stress. In stressed syllables, H1*–H2* was significantly higher than for unstressed syllables, signaling a breathier-like voice quality. Similarly, speakers’ syllables got creakier (H1*–H2* decreased) over the course of the utterance. There were no effects for the irony type.

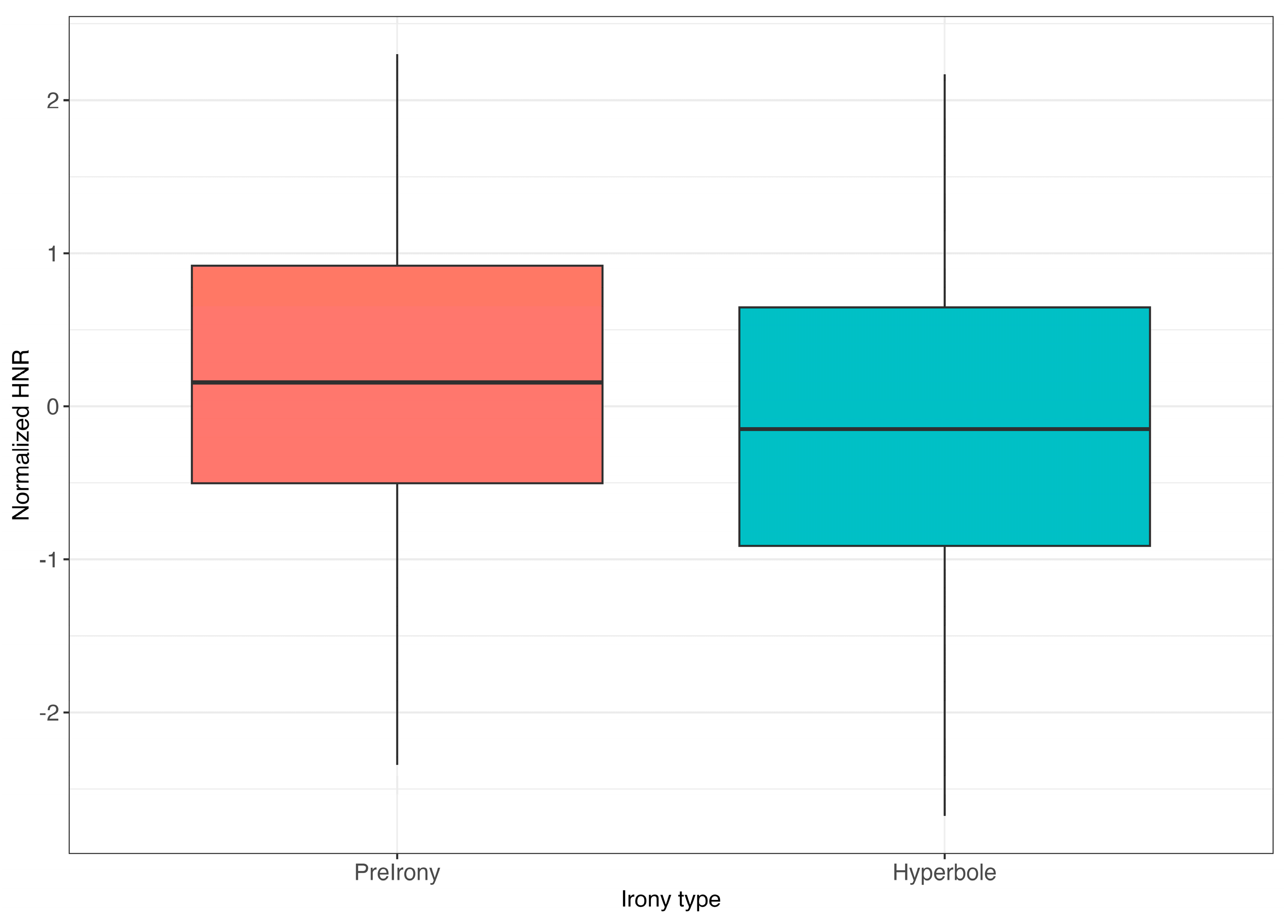

Importantly for the purposes of the present paper, the irony category was also selected as significantly affecting the HNR (as seen in the model summary in

Table 4).

HNR was significantly lower for syllables within hyperbolic utterances, signaling higher rates of noise, or increased non-modal voice quality, as compared to syllables in the pre-ironic baseline. This effect is shown below in

Figure 5.

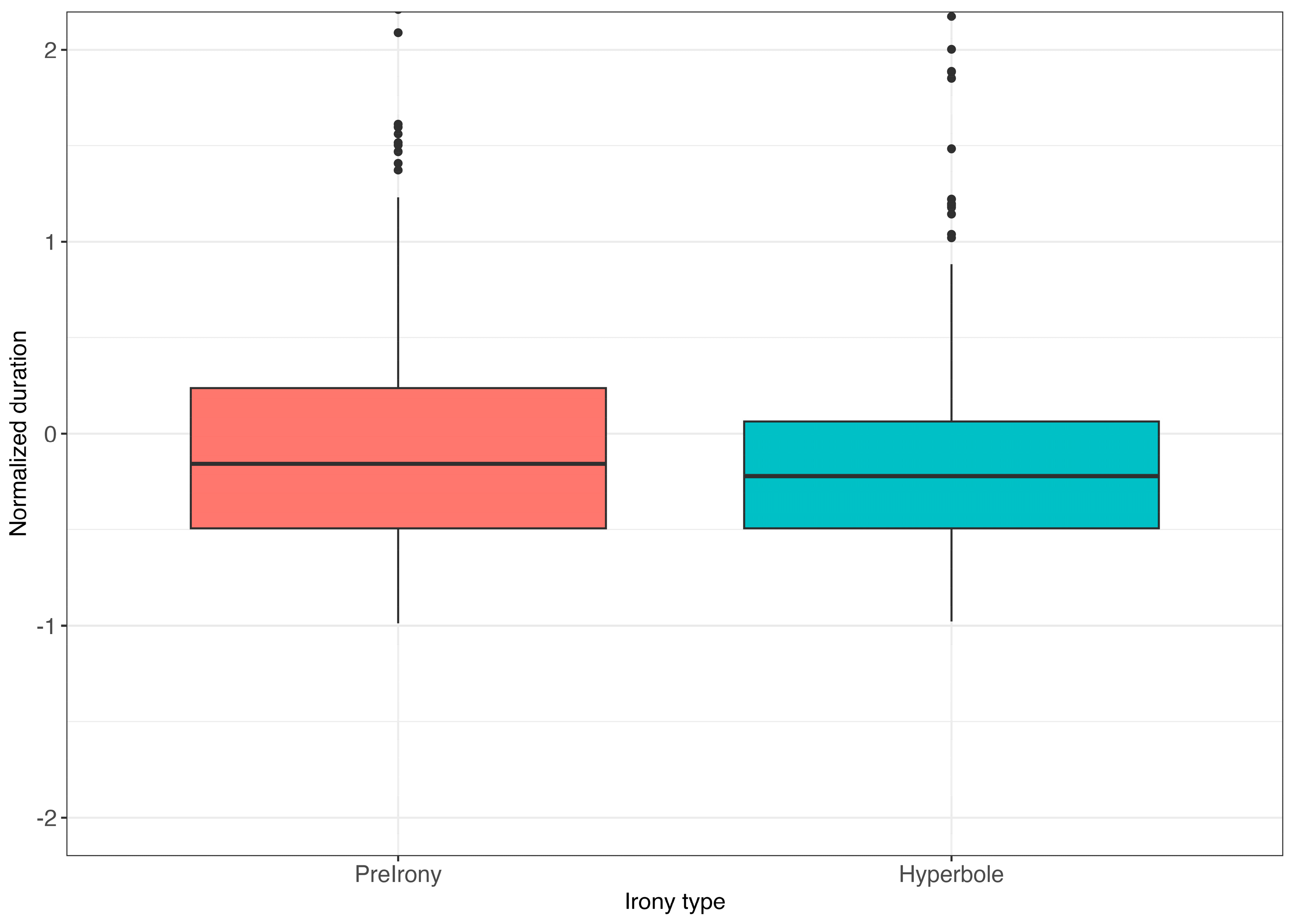

In the final model for the hyperbolic irony dataset, in which normalized duration is used as the dependent variable, vowel duration is shown to be significantly shorter for syllables within hyperbolic utterances as compared to the pre-ironic baseline (see

Table 5 below for the model summary). This effect is represented in

Figure 6.

In sum, syllables in utterances of the hyperbolic irony type are associated with decreased HNR, signaling more noise or less modal phonation, and significantly shorter durations as compared to the pre-ironic baseline.

5.4. Rhetorical Questions

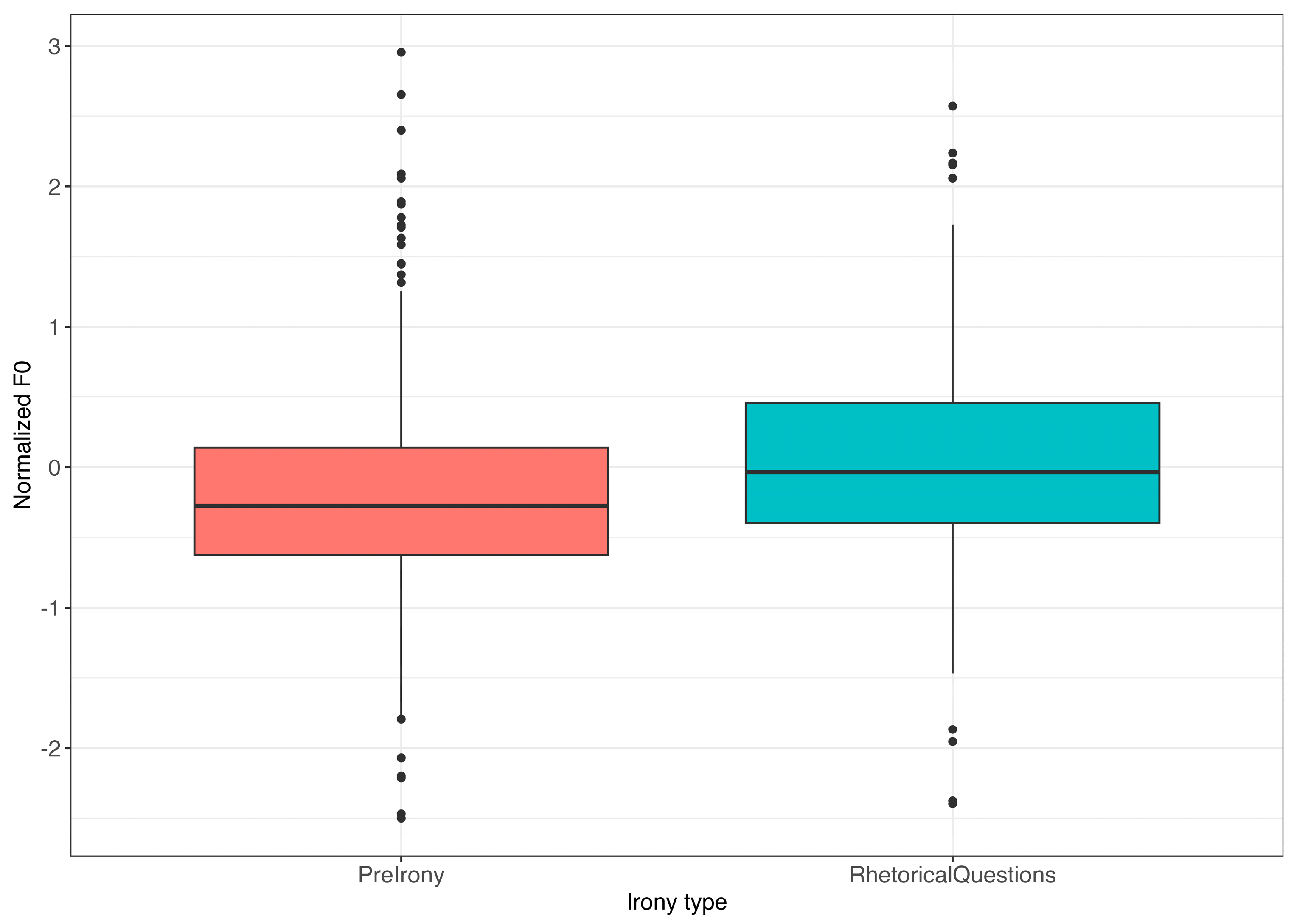

Finally, we created a subset of the data using only syllables from rhetorical question irony utterances and their corresponding syllables from the pre-ironic utterances (

n = 597). According to the best-fit model taking normalized F0 as the dependent variable, only the irony category significantly affected the outcome (see

Table 6 for the model summary).

That is, for syllables within the rhetorical questions irony subtype, F0 (heard as pitch) was significantly higher than for syllables in the pre-ironic baseline (as seen in

Figure 7 below). Interestingly, there was no effect for ratio, suggesting that instead of a rising terminal as might be expected in a rhetorical question intonational pattern, syllables within the rhetorical question utterance had a higher pitch overall than those within the pre-ironic baseline utterances. No other independent variables were selected by the model to affect the pitch.

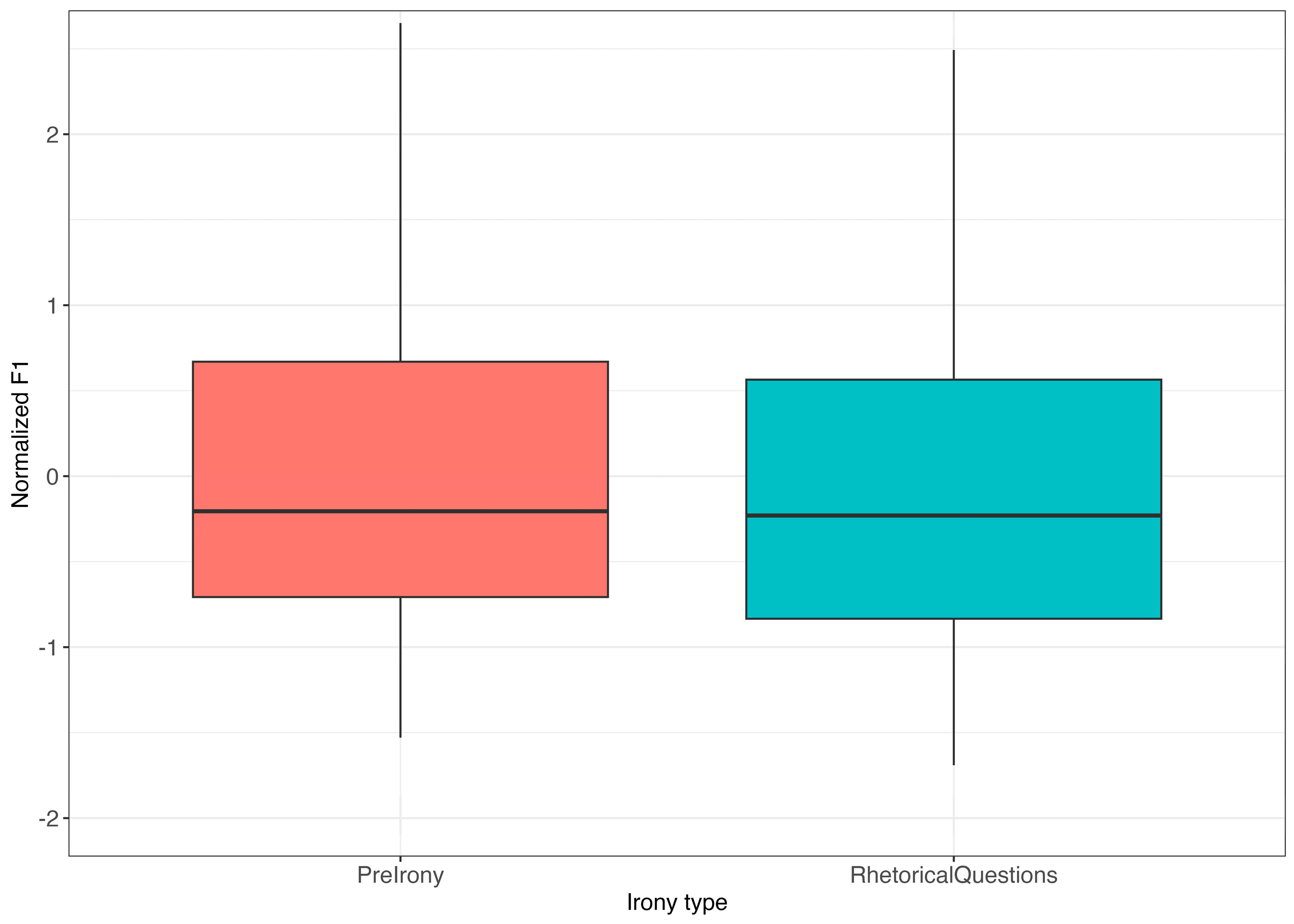

The results of the model taking normalized F1 as the dependent variable reveal several significant effects (see

Table 7 for the best-fit model summary).

Specifically, as expected, the vowels’ F1 varied according to vowel identity, since F1 is inversely correlated with vowel height. Additionally, stressed syllables had a significantly higher F1 (signaling lowered vowels) than unstressed syllables. Finally, and importantly, vowels within the rhetorical questions irony subtype were produced with a lower F1 (signaling raised vowels) than syllables within the pre-ironic baseline utterances. This effect is visualized in

Figure 8.

Only the vowel identity significantly affected the normalized F2 variable, as expected, due to the correlation between F2 and vowel frontness. There was no effect on the F2 for the rhetorical questions irony subtype.

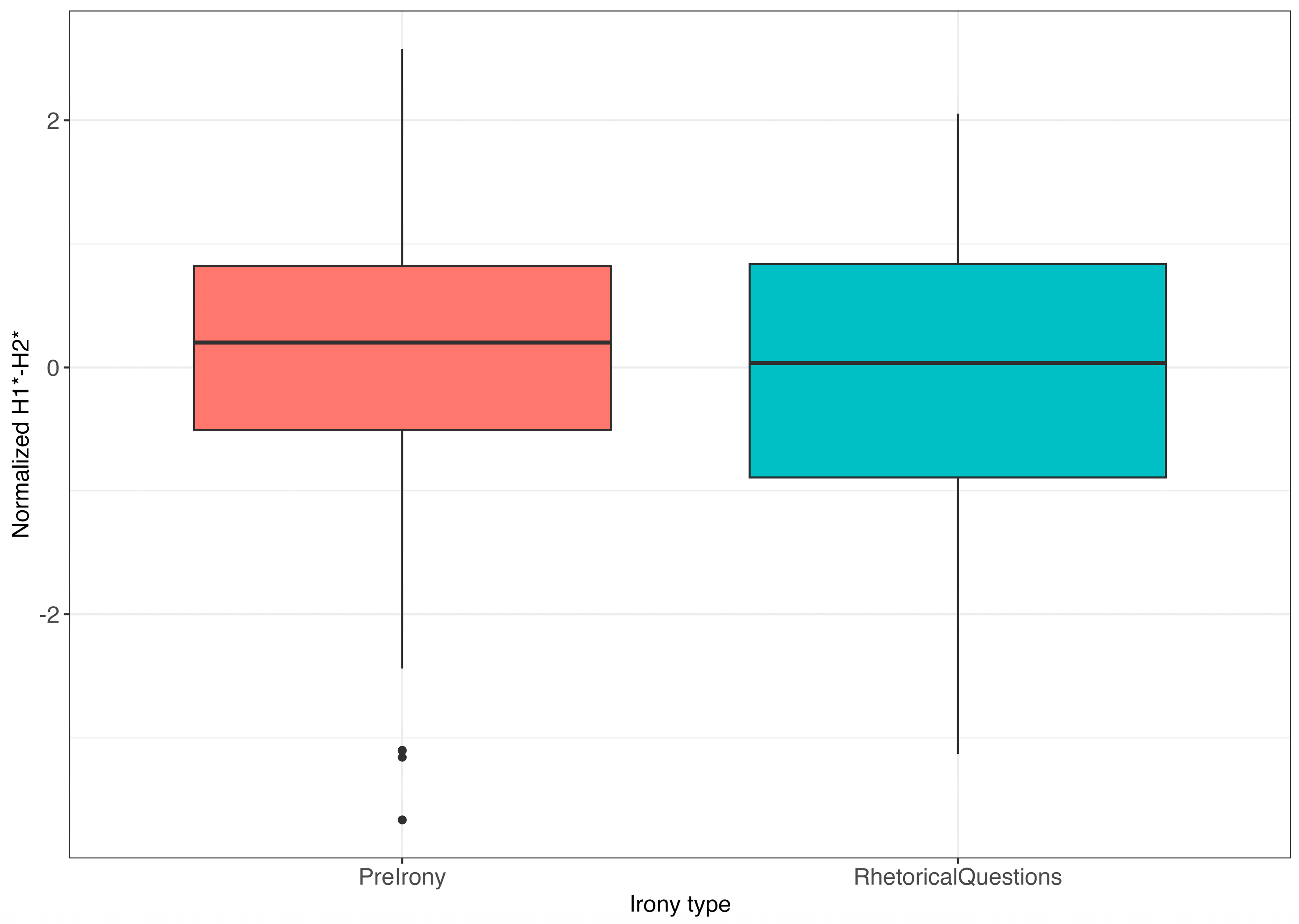

For syllables within the rhetorical questions utterances, H1*–H2* was significantly lower than for syllables within the pre-ironic baseline (see best-fit model results in

Table 8).

This signals a creakier-like voice quality in the rhetorical questions utterances as compared to those in the pre-ironic baseline utterances. This difference is visualized in

Figure 9.

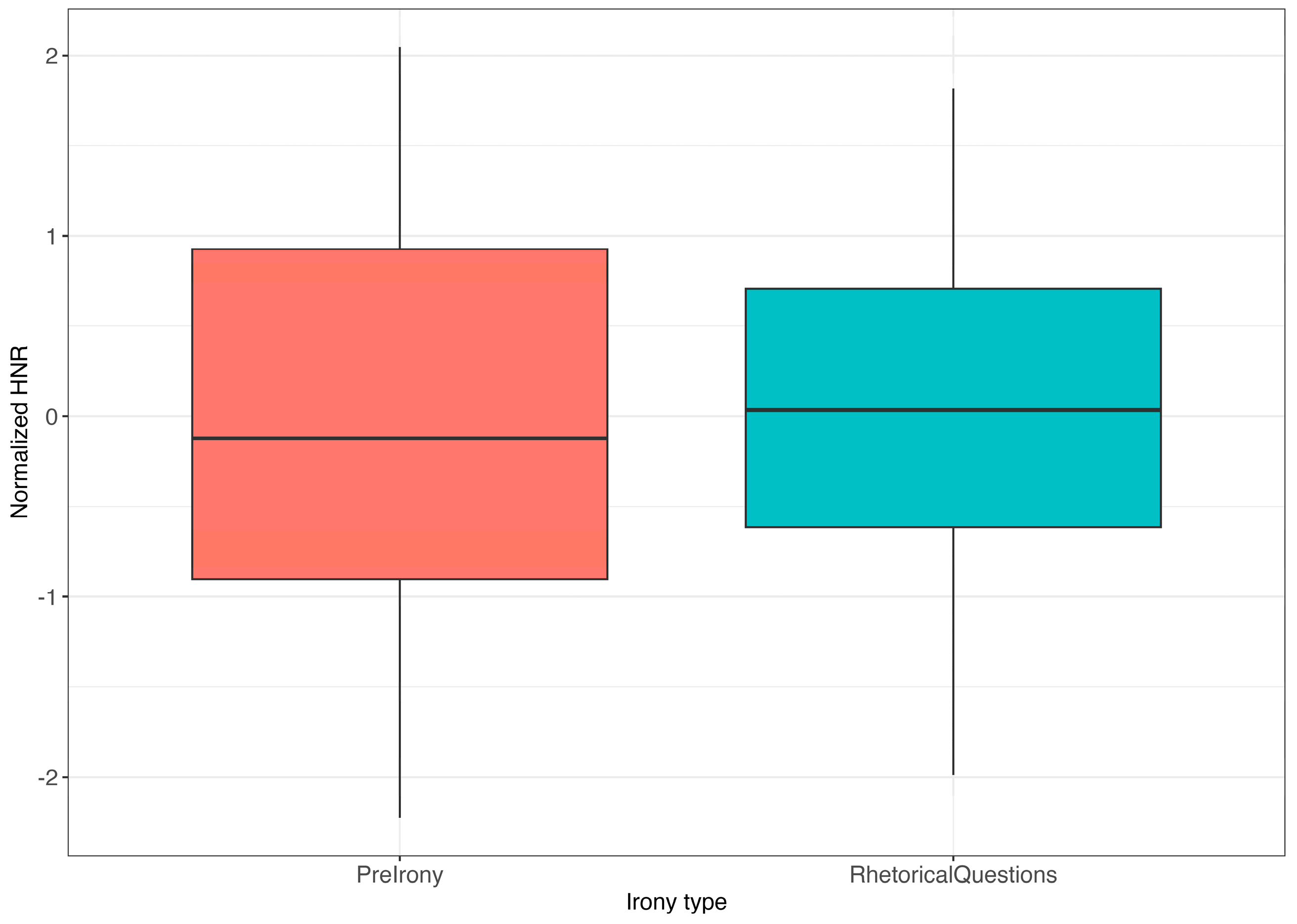

The results of the model evaluating HNR as the dependent variable reveal that HNR is significantly lower for syllables within rhetorical questions utterances as compared to the pre-ironic baseline (see the best-fit model summary in

Table 9, and the figure of this effect in

Figure 10).

Taken together with the previously mentioned finding that H1*–H2* is significantly lower for syllables within the RQ irony subtype, these findings provide evidence that rhetorical questions are produced as creakier than the pre-ironic baseline utterances.

Duration was only found to be conditioned by the syllable stress (with stressed syllables associated with longer duration, as expected); there was no effect for duration in the comparison of rhetorical questions versus pre-irony baseline utterances.

In sum, syllables within utterances of the rhetorical questions irony subtype are associated with an increased F0, a decreased F1 (or raised vowels), and creakier voice quality (as indicated by both a lower H1*–H2* and a lower HNR).

6. Discussion

In this section, we discuss our findings, overall and according to the subtype of irony, and engage with the discussion on prosody and pragmatics more generally. Our analyses revealed both expected and unexpected results related to irony.

Our first research question focused on uncovering the subtypes of irony that were more prevalent in our data, which consisted of casual speech samples from Chilean women extracted from informal sociolinguistic interviews. We hypothesized that jocularity (i.e., the teasing of a person, object, or event, in a playful way) was going to be the most common form of irony, and we confirmed our hypothesis. Jocularity was strongly favored by the speakers in our study, followed by hyperbole and rhetorical questions. Interestingly, sarcasm and understatements were not found in the data.

The speech samples in this paper were extracted from interviews conducted by the first author, who, despite her efforts at maintaining an informal, conversational mood, was a stranger to the interviewees. While we agree with

Davies (

2004, p. 224) in that “irony assumes extensive shared knowledge, including concerning participants’ attitudes, and for that reason might be considered too risky for sociable conversation (e.g., small talk) among strangers”, we also propose that this might not be the case for all subtypes of irony and for all types of conversational encounters, based on our results. That is, jocularity, which seems to be the least face-threatening form of irony, might be appropriate in certain sociocultural contexts even among strangers and during brief conversational encounters. According to

Davies (

2004), in some languages (such as English), using playful irony in conversations is a form of solidarity behavior that assumes shared knowledge, assumptions, and attitudes that might be expected between two individuals who know each other well. This might not be the case in Spanish.

In the context of the present study, rapport was developed through the conversation via the willingness of the interviewees to discuss the sensitive nature of the topics that arose, and the empathetic listening of the interviewer, as well as smiling, nodding, and the use of other verbal and nonverbal communication on the parts of both parties. We posit that the frequent use of jocularity in our data occurs as an outgrowth of the resulting established rapport, since it signals some level of comfort and closeness between the interlocutors. Jocular irony is then used as a mechanism to allow speakers to discuss serious real-life events in a humorous way without engaging in risky behavior. Jocular irony (and other subtypes of irony seen here) can therefore be seen as a form of interpersonal stance taking (

Kiesling 2009).

On the other hand, sarcasm can be much more face threatening and, therefore, is less likely to occur between two unfamiliar interlocutors, as it can be potentially perceived as carrying some level of criticism (

Gibbs 2000). The finding that sarcasm did not spontaneously occur in our data between unfamiliar interlocutors is especially salient given that many studies of verbal irony (and its prosodic correlates) specifically address sarcasm.

With regard to understatements, it is possible that we simply did not have enough background knowledge shared with the speakers in order to recognize understatements when they occurred. For instance, one speaker said the following when asked what her hobbies were, saying that she and friends play in a band:

[Pre-ironic utterance] va a la casa y toca guitarra

[Ironic utterance] intentamos de tocar (risa)

He goes to the house and plays guitar

We try to play (laughter)

We did not have the background information about this speaker’s and their friends’ skills at playing in their band. If they were actually very talented, this utterance could be categorized as an understatement. However, we did not have sufficient knowledge to make this claim.

We now turn to our second research question, targeting how irony is conveyed prosodically. Our first set of findings demonstrated that utterances from the jocularity and hyperbole irony subtypes co-occur with a wider F0 (pitch) range than the pre-ironic baseline utterances, while the rhetorical questions subtype did not. Sentences with a wide pitch range in Spanish are usually interpreted as lively or involved, or perhaps overexcited or urgent, while utterances with a narrow pitch range are usually interpreted as detached, sad, or bored (

Estebas-Vilaplana 2014).

Hidalgo Navarro (

2011) argued that spontaneous humorous utterances in Peninsular Spanish are accompanied by increased intensification, which has the purpose of contributing to the affinity between the speaker and hearer (p. 275). We posit that this pitch range widening serves a similar purpose in our data, as well as indicating that the utterance should be somehow salient to the listener. By differentiating these ironic utterances prosodically from the speech that precedes them, the speakers attempt to make the mismatch between reality and expectation salient, while also conveying their attitudes towards a given situation. In future research, it would be interesting to interrogate listener perceptions of these three irony types, given that sarcasm and rhetorical questions have been shown in English to be perceived as more aggressive, critical, and negative than jocularity, hyperbole, and understatements, which are generally perceived as funny, playful, and innocent.

The most frequent subtype of irony in our data, jocularity, was distinguished at the syllable level from its pre-ironic baseline in only one way: our findings showed that syllables in the jocularity utterances were associated with a lower HNR (additional noise in the speech signal, or less modal phonation).

Hyperbolic utterances were also produced with a lower HNR, indicating the production of syllables with noisier phonation. Interestingly, syllables in hyperbolic utterances were also shorter than those in baseline utterances. This differs from the findings by

Bryant (

2010), who found that syllables in all five types of ironic utterances were longer than pre-ironic baseline utterances.

Bryant (

2010) claimed that this lengthening was related to the increased cognitive load needed for decoding ironic utterances. That is, in order for the utterances to be recognized by the interlocutor as ironic, the speaker produced them more slowly. However, we find the opposite, and only for this one subtype of irony. We posit that this particular characteristic of hyperbole in our data may be related to its nature. Hyperbole, unlike rhetorical questions and jocular irony, can be lexically identifiable as ironic in both English and Spanish due to the speaker’s choice of adjectives and adverbs, such as quantifiers (e.g., all, every, none), numerals (e.g., millions, thousands), superlatives (e.g., sunniest, worst), adverbs of frequency (e.g., always, never), and other extreme language choices. In contrast, other types of irony may have different interpretations based on the conversational context. For instance, some structures such as statements or commands, such as “Lift your game, Martina!” (in Example 1), are only jocular if they are interpreted within a certain context. Otherwise, they can be mistakenly taken at face value (i.e., not going beyond the literal meaning and ignoring the context). Perhaps, then, since hyperbole is already indicated via lexicogrammatical cues, increased duration is not necessary for the speaker to mark the statement as ironic and, in fact, speakers can articulate hyperbolic utterances even more quickly given the presence of these cues. We acknowledge that this finding might be particular to Spanish, since marking hyperbole lexicogrammatically happens in both languages.

Rhetorical questions were associated with several acoustic and prosodic differences in comparison to the pre-ironic baseline: increased F0, decreased F1, lower H1*–H2*, and lower HNR. Regarding the increase in F0,

Ortiz et al. (

2010) indicated that in Chilean Spanish elicited utterances, rhetorical questions tend to be produced with a rising pitch movement (L + H* pitch accent). However, we did not find a rising pitch movement (or an increase in F0 over the course of the utterance), but rather, that the pitch values were higher

overall in the rhetorical question utterances as compared to the baseline. Interestingly, rhetorical questions were the only irony subtype that were not produced with a wider pitch range as compared to the pre-ironic baseline utterances. Rather, each of the syllables in the rhetorical questions utterances were produced with a higher (if less variable) pitch than the baseline utterances. This could be related to the findings of

Tritou (

2021), who found that rhetorical questions were more likely to trigger negative reactions among Peninsular Spanish speakers because they challenge the addressee more directly than other subtypes of irony (

Gibbs (

2000) reports a similar finding in English). Perhaps speakers, when using rhetorical questions, articulate them with a higher F0 in order to mitigate those potentially negative reactions.

Escandell-Vidal and Prieto (

2020) review the literature on the increased F0 in Spanish and posit a direct connection to politeness, invoking

Ohala’s (

1984,

1994) frequency code, postulating a universal relationship between prosodic features and politeness.

Additionally, vowel F1 was found to decrease in rhetorical questions, suggesting that these questions are less prominent than pre-ironic utterances. An increase in F1 has been associated with stress (

Romanelli et al. 2018;

Torreira and Ernestus 2011), suggesting a relationship between the F1 increase and prominence.

Wennerstrom (

2013) argued that de-accenting of the prosodic features of utterances (or reducing them) creates a humorous effect. Essentially, they argue, humor arises from the “unexpected incongruity that occurs between the hearer’s initial mental model of the joke discourse and a humorous alternative” (p. 121). It is also possible that reducing or de-accenting rhetorical questions serves as an additional way to lessen or mitigate their result.

Finally, rhetorical questions were also found to have lower H1*–H2* and lower HNR than their pre-ironic baseline utterances. These two findings taken together offer compelling evidence that rhetorical questions are produced with creakier phonation than pre-ironic baseline utterances.

Interestingly, we found that all three subtypes of irony share one characteristic: all three consistently exhibited lower HNR as compared to the pre-ironic baseline utterances. While we are not advocating for HNR to be thought of as “an ironic voice quality”, meaning that not everything that has low HNR will be ironic, we are suggesting that speakers use lowered HNR to differentiate their ironic utterances from regular, baseline, non-ironic utterances. To explain why speakers do this, we can turn to

Bolyanatz (

2023) who recently examined spontaneously occurring creaky voice in sociolinguistic interviews in Chilean Spanish.

Bolyanatz (

2023) determined that creak was primarily used to invoke alignment with the listener via ensuring that their messages or stances (

Du Bois 2007) were understood and potentially endorsed. Similarly, we posit that the decreased HNR in the present study (which may signal either increased creaky or breathy phonation) found for syllables in all three subtypes of ironic utterances may serve the same purpose: that of aligning the speaker and hearer via a combination of humor and prosody.

While we are not the first to posit connections in Spanish between voice quality and affective or attitudinal states (cf.

Gil 2007, p. 219), this study does contribute to laying the groundwork for further exploration of the connection between pragmatics and voice quality (among other types of acoustic and prosodic features).

Finally, we did not find any acoustic differences relating to age. This may be due to the fact that our “older” age speakers ranged from 42–66 years old, and previous work has found that normal aging in voices may begin in the 40s and 50s (

Ning 2019). We also acknowledge that the sample size differences across the three subtypes of irony may contribute to differences in the findings. That is, our jocularity dataset was about four times larger than our rhetorical questions dataset, but this was due to the spontaneously occurring nature of the ironic utterances. As previously mentioned, we also cannot know based on this particular study whether irony production would be similar or different with interlocutors from different genders, more local backgrounds, or other native Chilean Spanish speakers, but this is a potential consideration for future research.

7. Conclusions

Our study addressed the prosody of ironic speech in Chilean Spanish, a phenomenon lying at the prosody–pragmatics interface. By examining the acoustic correlates of different subtypes of verbal irony that occurred in our data, we were able to outline the prosodic characteristics of speech practices that carry a heavy pragmatic component.

First, our findings uncovered that jocularity, rhetorical questions, and hyperbole spontaneously occurred in our data, which involved casual conversations with an unfamiliar interlocutor. Of these three subtypes, jocularity was the most commonly used. Jocular irony involves a playful teasing or mockery, without necessarily involving criticism, minimization, or exaggeration like sarcasm, understatements, and hyperbole do. In future work, we would like to examine whether jocularity and its co-occurring prosodic features could be conceptualized as a linguistic resilience strategy. That is, might the women in our study be using jocular irony as a strategy for coping with difficulties related to their socioeconomic realities, such as the ones shared in their interviews (e.g., being forcibly relocated by the government, or the prevalence of drug addiction in the community affecting many families)?

Second, each of these three types of irony were prosodically distinct from the preceding non-ironic utterances. Syllables in all three subtypes of irony were found to have lower HNR, which we posit may help to make the ironic utterance salient and potentially align the speaker and hearer via a combination of humor and prosody. Jocularity and hyperbole also have wider pitch ranges from the pre-ironic baseline utterances, which may similarly be related to marking salience or developing an affinity between the speaker and hearer. Rhetorical questions were not significantly different from the baseline utterances in terms of the pitch range, but rhetorical questions did exhibit a higher overall pitch than the baseline utterances. We posit that this may be due to the more negative or critical nature of rhetorical questions, and that the higher pitch for these utterances helps to mitigate that negativity.

Finally, a large number of ironic utterances were categorized as representing jocular irony in our data. It is possible that, upon incorporating more targeted subdivisions such as dividing the jocularity category according to topics of conversation, additional pragmatic and prosodic distinctions may be revealed.

In sum, our data offer insight into spontaneous verbal irony between two unfamiliar interlocutors in a casual speech situation and contribute to the connection between prosody and pragmatics in Chilean Spanish. This study also lays the groundwork for further examination of irony and prosody in this and other Spanish dialects.