1. Introduction

| (1) | What happens? |

| | a. | Estos teléfonos | se | reparan | fácilmente. |

| | | these telephones | RFL | repair | easily |

| | | ‘These phones are easy to repair.’ |

| | b. | *Teléfonos se reparan fácilmente. |

| | c. | ?Se reparan estos teléfonos fácilmente.1 |

This situation differs from what happens in other related unaccusative se-sentences, such as se-passives, where the grammatical subject commonly occurs postverbally and it can be a bare nominal (2).

| (2) | What happens? |

| | a. | Se | repararon | (estos) teléfonos. |

| | | RFL | repaired | these telephones |

| | | ‘(These) telephones were repaired.’ |

| | b. | ?(Estos) teléfonos se repararon. |

The verb’s internal argument in middle passives may be a body-part noun. These are classified as relational nominals, for they inherently denote an inextricable part-whole or possession relationship with another entity; in other words, their meaning necessarily involves an inalienable possessor, unlike what happens with most common nouns (

Picallo and Rigau 1999). In Spanish, the possessor may be expressed internally by means of a possessive determiner (3a) or a genitive PP (3b).

| (3) | a. | Sus arrugas se ven fácilmente. |

| | | his wrinkles RFL see easily |

| | | ‘His wrinkles are easily visible.’ |

| | b. | Las arrugas de Ismael se ven fácilmente. |

| | | the wrinkles of Ismael RFL see easily |

| | | ‘Ismael’s wrinkles are easy to see.’ |

| (4) | What happens? |

| | a. | Minerva lei | vio | [las arrugas]i | a Albusi. |

| | | Minerva 3SG.DAT saw | the wrinkles | Albus.DAT |

| | | ‘Minerva saw Albus’ wrinkles.’ |

| | b. | Minerva lei vio a Albusi [las arrugas]i. |

| | c. | ?A Albusi Minerva lei vio [las arrugas]i. |

| | d. | ?A Albusi lei vio [las arrugas]i Minerva. |

On the contrary, the unmarked position for the dative DP in out-of-the-blue middle-passive contexts is preverbal, either as the sole fronted constituent, therefore forcing the theme DP to remain inside the VP (5a), or together with the theme DP (5b,c), but not postverbally (5d).

| (5) | What happens? |

| | a. | A Ismaeli | se | lei | ven [las arrugas]i fácilmente. |

| | | Ismael.DAT RFL | 3SG.DAT | see the wrinkles easily |

| | | ‘Ismael’s wrinkles are easy to see.’ |

| | b. | A Ismaeli, [las arrugas]i se lei ven fácilmente. |

| | c. | [Las arrugas]i, a Ismaeli se lei ven fácilmente. |

| | d. | ?[Las arrugas]i, se lei ven a Ismaeli fácilmente. |

The idiosyncrasy of middle-passive sentences with respect to their word order, along with their interaction with dative arguments, can therefore be used to gain further insight into the hotly debated positions that preverbal subjects and dative DPs occupy in Spanish.

Among the different generative analyses of dative possessors in Romance languages in general, and in Spanish in particular,

Cuervo (

2003) proposes that these DPs are introduced in the specifier of a low applicative projection (

Pylkkänen 2002), i.e., an argument-introducing functional head responsible for relating two entities: a possessor in its specifier and a possessee in its complement position. The dative clitic pronoun, whose phi features match those of the possessor DP, spells out the applicative head, and the entire applicative projection merges as the verb’s complement. Because middle-passive configurations lack an external argument, Tº would probe the closest DP—the dative DP—to its specifier, while the theme DP would remain inside the VP, as shown in (6).

| (6) | [TP a Ismaeli [T se lei ven [VoiceP [vP [√P [ApplP ti [Appl le [DP las arrugas]]] √v-]]]]] |

While this approach accounts for the sentence in (5a) straightforwardly, I will show that it runs into a minimality violation (

Rizzi 1990,

2012) when deriving the sentence in (5b), where it appears that the dative DP is left dislocated, and the theme DP sits in the preverbal subject position. If that was the case, the theme DP would be probed to subject position over the empty dative pronoun that must necessarily sit in the specifier of the applicative head for the relationship of possession to hold.

| (7) | ![Languages 09 00015 i001]() |

Instead, I will present data suggesting that preverbal dative DPs and theme DPs in Spanish middle passives are left dislocated. This will lead me to pursue an analysis within the minimalist generative framework (

Chomsky 1995) that is in line with

Barbosa’s (

2009) account for preverbal subjects in consistent null subject languages like European Portuguese, whereby these constituents are left dislocations coreferring with empty pronouns inside the sentence. I will show how this proposal avoids any potential intervention effects. Finally, I will also explore how these data can be accommodated within a biclausal/paratactic approach (

Ott 2014,

2015;

Fernández-Sánchez and Ott 2020;

Villa-García and Ott 2022,

inter alia).

The article is structured as follows:

Section 2 discusses how inalienable possession can be analyzed in Spanish, focusing particularly on instances of external possession.

Section 3 is devoted to Spanish middle-passive sentences; in it, I provide a brief survey of the most salient structural properties of middle-passive sentences in Spanish and show how they can be analyzed syntactically. In

Section 4, I describe how middle-passive sentences interact with dative possessors, paying special attention to the different possible word orders; moreover, I explain why a low applicative analysis of dative possessors in these constructions along the lines of

Cuervo (

2003) is susceptible to run into intervention effects. I contend that this technical shortcoming can be done away with if preverbal dative and theme DPs are extrasentential, i.e., left dislocations, and I provide evidence to support this idea. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Dative Possessors and (in-)Alienable Possession

The inextricable connection between a body-part noun and its possessor, or that between two entities in a part-whole relation, is known as inalienable possession (

Guéron 2006). This construal is also possible with relational nouns, i.e., nominals denoting items pertaining to someone’s personal sphere (

Bally 1926), including those referring to personality traits, family members, and familiar objects such as items of clothing. The grammar of Spanish offers different strategies to encode (in)alienable possession. On the one hand, the possessor—be it inalienable or not—can be conveyed internally, i.e., inside the DP containing the possessum, by means of a possessive determiner (8a), a strong possessive (8b),

2 or as a DP inside a PP (8c).

| (8) | a. | Sus | arrugas/cartas. | |

| | | his.PL | wrinkles/letters | |

| | | ‘His wrinkles/letters.’ |

| | b. | Las | arrugas/cartas | suyas. |

| | | the.F.PL | wrinkles/letters | his.F.PL |

| | | ‘His wrinkles/letters.’ |

| | c. | Las arrugas/cartas de Javier. |

| | | the wrinkles/letters of Javier |

| | | ‘Javier’s wrinkles/letters.’ |

| (9) | Tania lei | vio | [*susi/las/varias arrugas]i | (a Albertoi). |

| | Tania 3SG.DAT | saw | his/the/several wrinkles.ACC | Alberto.DAT |

| | ‘Tania saw (several of) Alberto’s wrinkles.’ |

In her theory of dative arguments in Spanish,

Cuervo (

2003) establishes a parallelism between dative possessors and datives in double object constructions (henceforth, DOCs), and notes that these arguments are structurally identical in terms of case, hierarchical position, word order, and spell-out form, i.e., the dative clitic. Moreover, dative possessors and datives in DOCs are semantically related directly to the object, not the verb. Thus, Cuervo concludes that Spanish dative possessors are indeed instances of DOCs.

| (10) | Tania lei | envió un mensaje | a Luisi. |

| | Tania 3SG.DAT | sent | a message.ACC | Luis.DAT |

| | ‘Tania sent Luis a message.’ |

Cuervo assumes

Pylkkänen’s (

2002) analysis of DOCs, whereby dative arguments in these configurations are introduced in the specifier of a low applicative head, i.e., an argument-introducing functional head relating two arguments, the dative DP in its specifier, and the theme in its complement position; the entire ApplP merges as the verb’s internal argument. According to Pylkkänen, the particular semantics of the applicative determines whether the argument in its specifier is interpreted as a goal (11a) or a source (11b). Furthermore, Cuervo adds a third kind of low applicative head, a possessor applicative, whose semantics convey a static relation of possession, and which is responsible for introducing dative possessors (11c).

| (11) | a. | APPLTO (Goal applicative): |

| | | λx.λy.λf<e<s,t>>.λe. f(e,x) & theme (e,x) & from-the-possession-(x,y) |

| | b. | APPLFROM (Source applicative): |

| | | λx.λy.λf<e<s,t>>.λe. f(e,x) & theme (e,x) & to-the-possession-(x,y) |

| | c. | APPLAT (Possessor applicative): |

| | | λx.λy.λf<e<s,t>>.λe. f(e,x) & theme (e,x) & in-the-possession-(x,y) |

Thus, Cuervo analyzes sentences containing a possessor dative as shown in (12).

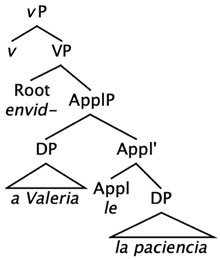

| (12) | a. | Cuervo (2003, p. 76; example 86a) |

| | | Pablo lei | envidia [la | paciencia]i | a Valeriai. |

| | | Pablo 3SG.DAT | envies the | patience | Valeria.DAT |

| | | ‘Pablo envies Valeria for her patience.’ |

| | b. | ![Languages 09 00015 i002]() |

In (12), the root √envid- takes a low applicative of possession (Low-APPLAT) projection, in whose specifier merges the dative DP a Valeria that is related to the DP la paciencia in complement position, thus allowing the relationship of possession to obtain; the dative clitic le, whose phi features mirror those of the dative DP, spells out the applicative head.

Cuervo points out that the dative possessor construction is not restricted to inalienable possession and proposes the same derivation for sentences like (13), where the possessum is alienably possessed. In her proposal, the applicative is needed to establish the possessive relationship between the possessor originating in its specifier and the possessee in its complement position. Cuervo does not delve into how the inalienable possession construal arises in these structures, and one must assume it is determined by the type of noun the possessum DP contains.

| (13) | Cuervo (2003, p. 74; example 87a) |

| | Pablo lei | envidia | [el | auto]ia Valeriai. |

| | Pablo 3SG.DAT | envies | the | car | Valeria.DAT |

| | ‘Pablo envies Valeria for her car.’ |

Here, I will adopt

Suárez-Palma’s (

forthcoming) analysis of possession, which is based on an adaptation of

Alexiadou et al.’s (

2007) proposal of the possible positions where possessors can merge or be licensed inside the possessum DP, captured in (14).

| (14) | Adapted from Alexiadou et al. (2007, p. 575) |

| | 1. | Lexical DP possessives | John’s book | (English) |

| | 2. | Clitic possessives | Su libro | (Spanish) |

| | 3. | ‘Weak’ pronoun possessives | El seu llibre | (Catalan) |

| | 4. | Postnominal strong possessors | El seu llibre | (Spanish) |

| | 5. | Alienable possessors | | |

| | 6. | Inalienable possessors (PRO) |

| | | ![Languages 09 00015 i003]() |

Suárez-Palma argues that all possessors originate in the specifier of Spec,nP, and later move within the DP to be licensed with genitive case. What distinguishes alienable from inalienable possession is the fact that relational and body-part nouns take a PRO as an argument in their specifier, which is controlled by the possessor in Spec,nP.

5 The latter can be an empty pronominal

pro or a full DP, both of which will require case licensing. When genitive case is available inside the possessum DP,

pro will surface as a clitic (

sus ojos; ‘her eyes’), weak (

els seus ulls; ‘her eyes’),

6 or strong possessive (

los ojos suyos; ‘her eyes’), depending on the position this argument raises to within the DP. On the other hand, if it is a full DP, it will be case-marked by genitive preposition

de (

los ojos de Marina; ‘Marina’s eyes’).

7 In the event that genitive case is not available inside the possessum DP, the possessor DP will need to exit it and raise to a position where it can be case-licensed, i.e., the specifier of an applicative phrase. In other words, for Suárez-Palma, the function of the low applicative of possession is merely to case-license the possessor DP when no functional projection inside the possessum DP is able to do so. This straightforwardly accounts for the complementary distribution between possessives and dative possessors in most Spanish dialects and in other Romance languages.

8 Thus, a sentence containing a dative possessor would show the derivation in (15).

| (15) | a. | Marta mei | pintó | [las uñas]i. |

| | | Marta 1SG.DAT | painted | the nails |

| | | ‘Marta painted my nails.’ |

| | b. | ![Languages 09 00015 i004]() |

In (15b), the relational noun uña takes PRO as an argument in its specifier, from where it is controlled by the empty pronominal pro, originating in Spec,nP, and standing for the possessor. The noun undergoes head movement to Agr° from where it establishes an agreement relation with the c-commanding determiner; pro, on the other hand, raises to the specifier of the low applicative head—spelled out by the dative clitic pronoun me—to value dative case. The dative clitic incorporates into the verb, which raises to Tº; finally, the external argument Marta is introduced in the specifier of a Voice projection and is later probed by Tº to its specifier to check its EPP feature, where it is also assigned nominative case. In the next section, I describe the most salient properties of middle-passive sentences in Spanish and discuss how these configurations interact with dative possessors.

3. Middle-Passive Constructions in Spanish: Description and Analysis

Cross-linguistically, the middle voice refers to a number of stative, generic configurations denoting atemporal intrinsic properties of the verb’s internal argument, which surfaces as the grammatical subject (

Ackema and Schoorlemmer 2006, inter alia).

| (16) | Cotton shirts iron easily. |

Languages differ in the way their grammars encode this construal.

Lekakou (

2005), for instance, explains that middle constructions in languages such as Dutch, German, or English are syntactically unergative, while in others like Greek or French, they are unaccusative predicates, being syntactically indistinguishable from generic passives. Such crosslinguistic variation resulted in the development of numerous analyses of different natures, including syntactic (

Keyser and Roeper 1984;

Hale and Keyser 1988;

Roberts 1987;

Stroik 1992;

Lekakou 2005;

Schäfer 2008;

Suárez-Palma 2019;

Suárez-Palma 2020;

Fábregas 2021), semantic (

O’Grady 1980;

Dixon 1982;

Condoravdi 1989;

Chierchia 2003;

Lekakou 2005), and lexicalist accounts (

Fagan 1992;

Ackema and Schoorlemmer 1995), to name a few. Despite this heterogeneity, there is consensus in the literature regarding several common traits these structures share across languages, namely the lack of an explicit external argument, the internal argument’s promotion to grammatical subject, their generic, nonepisodic nature, their modal interpretation, as well as the quasi-mandatory modification by an adjunct.

The structures under consideration here have been traditionally known as middle-passives in the canonical descriptive work on Spanish grammar (

Mendikoetxea 1999). These sentences contain the reflexive clitic pronoun

se in its third person form, and their generic, stative nature makes them compatible only with imperfective tenses, i.e., present or imperfect. Moreover, middle-passive constructions denote the participation of a generic implicit agent in the event, which can be rephrased as ‘anyone,’ although its explicit realization by means of a by-phrase is banned.

| (17) | Esta blusa | se | lava | fácilmente | (*por Pedro). |

| | this blouse | RFL | washes | easily | by Pedro |

| | ‘This blouse washes easily.’ |

| | ‘Anyone can wash this blouse easily.’ |

Mendikoetxea (

1999) argues that the implicit external argument in middle-passives must necessarily be an agent; therefore, only verbs denoting activities or achievements would be eligible to enter these configurations (18a), while those whose external arguments are experiencers would be ungrammatical, as shown in (18b), which contains a predicate denoting a durative accomplishment (18b).

| (18) | a. | La historia de España | se | aprende fácilmente. |

| | | the history of Spain | RFL | learns easily |

| | | ‘The history of Spain is easy to learn.’ |

| | b. | Mendikoetxea (1999, p. 1656) |

| | | *La historia de España | se | Sabe de memoria. |

| | | the history of Spain | RFL | knows of memory |

| | | Intended: ‘The history of Spain is known by heart.’ |

The lack of an explicit external argument in middle-passive configurations favors the promotion of the verb’s internal argument to grammatical subject, triggering agreement with the verb; in fact,

Hale and Keyser (

1988) consider this argument to be a semiagent in these sentences, since its intrinsic properties are somehow responsible for the event. In (18a), for instance, it is the idiosyncratic properties of the history of Spain that favor its learnability.

As mentioned above, the grammatical subject in middle passives occurs preverbally in unmarked contexts and cannot be a bare NP, as shown by the ungrammaticality of (19a) should the determiner

estas be removed; this has been interpreted as evidence for the internal argument’s externalization from the VP (

Suñer 1982;

Fernández Soriano 1999).

9 The reason for this externalization would be the fact that the grammatical subject in middle-passive sentences has a discursive function, i.e., it is a sentential topic (

Fodor and Sag 1982;

Mendikoetxea 1999;

Sánchez López 2002;

Suárez-Palma 2019).

| (19) | What happens? |

| | a. | Estas | blusas | se | lavan fácilmente. |

| | | these | blouses | RFL | wash easily |

| | | ‘These blouses wash easily.’ |

| | b. | *Blusas se lavan fácilmente. |

| | c. | ?Se lavan estas blusas fácilmente.10 |

However,

Mendikoetxea (

1999) notes that this argument remains inside the verbal domain when another constituent is focalized and fronted (20).

| (20) | EN LA LAVADORA se | lavan estas blusas | fácilmente, no a mano. |

| | in the washer RFL | wash these blouses | easily | not by hand |

| | ‘IN THE WASHER these blouses wash easily, not by hand.’ |

In this respect, middle passives differ from other unaccusative se-sentences like se-passives, whose grammatical subject—which is also the verb’s internal argument—can be a bare NP and tends to occur postverbally (21).

| (21) | What happens? |

| | a. | Se | lavaron blusas. |

| | | RFL | washed blouses |

| | | ‘Blouses were washed.’ |

| | b. | *Blusas se lavaron. |

Finally, it is generally agreed that middle-passive constructions convey a modal interpretation (

Mendikoetxea 1999;

Sánchez López 2002), which is evidenced by the fact that they can be rephrased as a prototypical modal sentence (e.g.,

anyone can wash these blouses easily). Moreover, these structures are often modified by an adverbial or prepositional phrase, which enhances their modal reading.

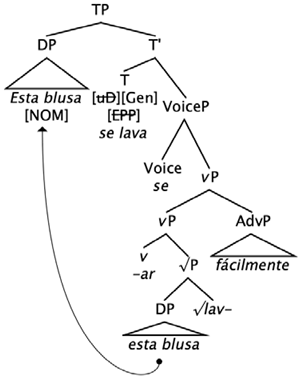

11Considering all the above, a middle-passive sentence like the one in (22) would show the following derivation:

| (22) | a. | Esta blusa se lava fácilmente. |

| | b. | ![Languages 09 00015 i005]() |

In (22), I follow

Schäfer (

2008) and

Suárez-Palma (

2019,

2020) in assuming that middle-passive constructions contain a Voice head (

Kratzer 1996), which is spelled out by the reflexive clitic

se and does not introduce an external argument. Furthermore, the combination of a generic operator (Gen) and an uninterpretable [D] feature in T° would cause the probing of the only DP available in the derivation, i.e., the theme DP

esta blusa, to the specifier of the TP to cancel its EPP feature, thus becoming the grammatical subject and valuing nominative case. Finally, the root

√lav- undergoes head movement, incorporating any clitics it finds on its way to T°.

In this section, I have outlined some of the most salient structural properties of middle-passive sentences in Spanish. For a more in-depth examination of the latter, I refer the reader to the thorough descriptions by

Mendikoetxea (

1999) and

Sánchez López (

2002), or the work by

Suárez-Palma (

2019,

2020) and

Fábregas (

2021) for more recent discussions. Next, I will discuss the interaction between middle-passive sentences and dative possessors in Spanish, paying particular attention to issues concerning word order in these configurations.

4. Dative Possessors, Middle-Passive Constructions and Word Order

Nevertheless, this does not seem to be the case for dative possessors in middle-passive configurations, which unmarkedly occur preverbally, presumably due to the lack of an external argument in these structures.

| (24) | What happens? |

| | a. | A Ismaeli se | lei | ven [las arrugas]i | fácilmente. |

| | | Ismael.DAT RFL | 3SG.DAT | see the wrinkles | easily |

| | | ‘Ismael’s wrinkles are easy to see.’ |

| | b. | A Ismaeli, [las arrugas]i se lei ven fácilmente. |

| | c. | [Las arrugas]i, a Ismaeli se lei ven fácilmente. |

| | d. | ?[Las arrugas]i, se lei ven a Ismaeli fácilmente. |

In this respect, dative possessors in Spanish middle-passive constructions resemble preverbal dative experiencers.

Masullo (

1992) notes that negatively quantified dative experiencer DPs, which also tend to occur preverbally, lose their quantificational scope if they are left dislocated, and are thus interpreted referentially, as shown in (25).

| (25) | Masullo (1992, p. 90) |

| | a. | A nadie | le | gusta la música pop en esta casa. |

| | | nobody.DAT 3SG.DAT | likes the music pop in this house |

| | | ‘Nobody likes pop music in this house.’ |

| | b. | *A nadie, le gusta la música pop en esta casa. |

| | | ‘Nadie likes pop music in this house.’ |

In (25a), the dative DP must be sitting in an A-position inside the sentence, hence its quantificational scope obtains. However, in (25b), the dative phrase is left dislocated outside the TP, therefore losing such interpretation. Masullo takes this as evidence for the fact that these phrases have subject-like properties and occupy the preverbal subject position, presumably Spec,TP. Interestingly, the same phenomenon is attested with dative possessor DPs in Spanish middle-passive sentences.

| (26) | a. | A nadiei | se | lei | ven [las arrugas]i fácilmente. |

| | | nobody.DAT RFL | 3SG.DAT see the wrinkles easily |

| | | ‘Nobody’s wrinkles are easily visible.’ |

| | b. | *A nadie, las arrugas se le ven fácilmente. |

| | | ‘Nadie’s wrinkles are easily visible.’ |

The dative DP in (26a) appears to have raised to preverbal subject position, where the quantificational reading of

nadie (‘nobody’) obtains. The theme DP is forced to remain inside the VP, which is not normally the case in Spanish middle-passive sentences without dative DPs. On the other hand, the dative DP in (26b) is left dislocated, which results in the loss of its quantificational reading, and allows the theme’s promotion to a preverbal subject position.

12 Note that despite the ungrammaticality of (26b), the dative DP and the theme may both surface together before the verb when no quantifiers are involved, as shown in (24b) and (24c) above. Considering the data above, a plausible derivation of a middle-passive sentence containing a preverbal dative possessor DP would be the following:

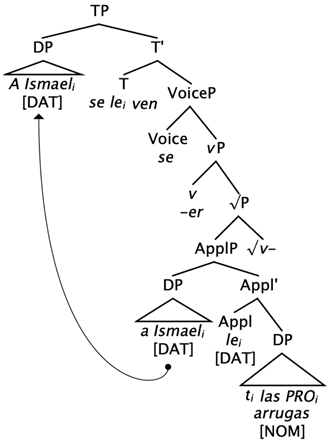

| (27) | a. | A Ismaeli | se | lei | ven [las arrugas]i | fácilmente. |

| | | Ismael.DAT RFL | 3SG.DAT see the wrinkles | easily |

| | | ‘Ismael’s wrinkles are easy to see.’ |

| | b. | ![Languages 09 00015 i006]() |

In (27), the possessor DP Ismael originates inside the possessum DP, in Spec,nP, from where it controls the PRO in the specifier of the relational noun arrugas. The possessor DP later exits the possessum DP to raise to Spec,ApplP, where it values dative case; the entire applicative projection merges as the complement of the verbal root √v-. Because this is a middle-passive configuration, no external argument is projected in the specifier of VoiceP, which is spelled out by se. In order to value its EPP feature, T° probes the closest DP to its specifier: in this case, the dative DP a Ismael; because this DP is already case-marked, Tº assigns nominative case to the theme DP las arrugas via Agree. Finally, the verb undergoes head movement to T, incorporating all the clitics it finds on its way.

While the derivation in (27b) straightforwardly accounts for middle-passive sentences where the possessor dative DP is the sole preverbal constituent, a problem arises in cases where both the dative DP and theme DP occur preverbally, as is shown in (28).

| (28) | a. | A Ismaeli, [las arrugas]i se lei ven fácilmente. |

| | b. | ![Languages 09 00015 i007]() |

In (28), the dative DP

a Ismael merges outside the TP as a dislocated constituent in the left periphery (

Rizzi 1997), here in Spec,TopicP, and bears an identity relation with the dative clitic

le inside the sentence; in other words, this is a clitic left-dislocation (CLLD) configuration (

Cinque 1990). The verbal root

√v- takes a low applicative head as its complement, containing the possessee

las arrugas. Because the dative DP is dislocated, the clause-internal argument standing for the possessor inside the sentence must be a null pronoun

pro which is unable to license genitive case inside the possessum DP, and therefore raises to the specifier of the low applicative phrase. Note that assuming that nothing sits in Spec,ApplP would violate the semantic definition of the low applicative of possession (low-APPL-AT) given in (11c). If

pro sits in Spec,ApplP then, when T° looks down to probe a DP to its specifier, it would find

pro rather than the theme, since the former is the closest DP to T°. In other words, probing the possessee over

pro would lead to a violation of minimality (

Rizzi 1990). In the next section, I explore a possible way to avoid these intervention effects.

4.1. Intervention Effects: A Solution

As seen above, a low applicative analysis of dative possessors in middle-passive configurations is likely to run into a locality violation when dealing with the configuration in which both the dative DP and theme DP occur preverbally, if we assume that the former is left dislocated and the latter sits in Spec,TP. An empty pronoun standing for the possessor must sit in Spec,ApplP in order to abide by the semantic notation of the low applicative of possession (low-APPL-AT) (cf. (11c) above), and this argument would intervene when T° tries to probe the theme DP sitting in Appl°’s complement position. In order to overcome this technical obstacle, I propose that dative DPs and preverbal subjects in middle-passive constructions are left-dislocated constituents, base-generated outside of the sentence, and coreferencing with empty pronominals in argument positions; in other words, these are instances of CLLDs.

Rigau (

1988) noted the different distributions that

pro and lexical subjects have, and showed that

pro’s behavior parallels that of clitics, not strong pronouns. Similarly,

Olarrea (

2012) explains that the coreferential element in CLLDs has to be an empty pronominal licensed by agreement, or a clitic, but never a tonic pronoun or a phrase (29).

| (29) | *Con Chloei, siempre | viajo | con Chloei/ellai. |

| | with Chloe always | travel | with Chloe/she |

| | ‘I always travel with Chloe/her.’ |

Finally,

Baker (

1995) proposed that lexical DP arguments are always associated with a

pro, which is the real argument, while lexical DPs are adjoined to a more peripheral position; he argued that the latter are not derived by movement but computed representationally through coindexation, following

Cinque’s (

1990) intuition for CLLDs. Let us look at the data more closely to see whether this proposal is on the right track.

| (30) | a. | [Las arrugas]i, | a nadiei | se | lei | ven | fácilmente. |

| | | the wrinkles | nobody.DAT | RFL | 3SG.DAT | see | easily |

| | | ‘Nobody’s wrinkles are easy to see.’ |

| | b. | Las arrugask [TP a nadiei se lei ven prok fácilmente] |

In (30), the dative DP

a nadie must be sitting in the preverbal subject position, i.e., Spec,TP, since a quantificational reading obtains; this implies that the theme DP

las arrugas is therefore left dislocated. If we assume a base generation approach for left-dislocated constituents (

Cinque 1990;

Frascarelli 1997,

2000),

13 then a third person plural null object pronoun

pro coreferring with

las arrugas must sit in the applicative’s complement position in (30a), which later becomes the grammatical subject via “Agree” (30b); these two constituents would enter a binding chain

à la Cinque (

1990), hence the identity relation they bear in terms of case and theta roles. Recomplementation data suggest that this is the case (

Demonte and Fernández Soriano 2009;

López 2009);

Villa-García (

2012,

2015) explains that clitic left-dislocated phrases that are sandwiched between two complementizers must be base generated, and that these phrases fail to show reconstruction effects, unlike their counterparts without recomplementation. In (31), the DP

las arrugas appears sandwiched between two complementizers, which reinforces the idea that this constituent is left dislocated. Additionally, (31) shows that, should the negatively quantified dative DP be followed by a complementizer, the quantificational reading fails to obtain, proving that this position is indeed extrasentential; unlike the DP

las arrugas, the quantified dative DP

a nadie must sit in an A-position inside the sentence in (31), i.e., in Spec,TP.

| (31) | Dice que las arrugas, | que a nadie | (*que) se le | ven | fácilmente. |

| | says that the wrinkles | that nobody.DAT that RFL 3SG.DAT see | easily |

| | ‘He says that, the wrinkles, that nobody’s, that they are easy to see.’ |

Notice, however, that when neither the dislocated theme DP nor the dislocated dative DP contain a quantifier, both can be sandwiched between complementizers.

| (32) | a. | Dice que a Ismael, | que las arrugas, (que) se le | ven fácilmente. |

| | | says that Ismael.DAT | that the wrinkles that RFL 3SG.DAT see easily |

| | | ‘He says that Ismael’s wrinkles, that they are easy to see.’ |

| | b. | Dice que las arrugas | que a Ismael, | (que) se le ven fácilmente. |

| | | says that the wrinkles | that Ismael.DAT that RFL 3SG.DAT see easily |

| | | ‘He says that the wrinkles, that Ismael’s, that they are easy to see.’ |

| (33) | a. | Complex NP island |

| | | *Estoy convencido de que | a Paulai | la | enfermera | conoce |

| | | I-am convinced of that | Paula.ACC | the | nurse | knows |

| | | a | la | doctora | que lai | examinó. | |

| | | to | the | doctor.ACC | that her | examined | |

| | | ‘I am convinced that the nurse knows the doctor who examined Paula.’ |

| | b. | Adjunct island |

| | | *Nos | parece mejor que a Paulai | cocinemos | la | cena |

| | | 1PL.DAT | seems better that Paula.ACC | we-cook | the | dinner |

| | | antes | de | avisarlai. | | | |

| | | before | of | tell-her | | | |

| | | ‘We believe it is best we cook dinner before telling Paula.’ |

| | c. | Wh-island |

| | | A Paulai | no sé | cómo | podríamos averiguar | quién |

| | | Paula.ACC | not I-know | how | we-could | guess | who |

| | | lai | invitó. | | | | |

| | | her | invited | | | | |

| | | ‘Paula, I don’t know how we could figure out who invited her.’ |

If preverbal subjects and dative DPs in middle-passive constructions are indeed instances of CLLDs, we should expect the same behavior regarding strong and weak islands; the data in (34) prove this hypothesis correct.

| (34) | Complex NP island |

| | a. | *Estoy seguro de que las arrugasi, | la | doctora conoce |

| | | I-am sure of that the wrinkles | the | doctor knows |

| | | a la persona | a la | que se le | ven proi | fácilmente. |

| | | the person.ACC | to the | that RFL 3SG.DAT | see pro | easily |

| | | ‘I am sure that the doctor knows the person whose wrinkles are easily visible.’ |

| | b. | *Estoy seguro de que, a Ismaeli, | la | doctora | examinó |

| | | I-am sure of that Ismael.DAT | the | doctor | examined |

| | | las arrugas | que se lei | ven | fácilmente. |

| | | the wrinkles.ACC | that RFL 3SG.DAT | see | easily |

| | | ‘I am sure that the doctor examined Ismael’s wrinkles that are easily visible.’ |

| | Adjunct island |

| | c. | ?Nos | parece mejor que, las arrugasi, cocinemos | la | cena |

| | | 1PL.DAT | seems better that the wrinkles.ACC we-cook | the | dinner |

| | | antes de | que se le | vean | proi | a Juan | fácilmente.14 |

| | | Before of | that RFL 3SG.DAT | see | pro | Juan.DAT | easily |

| | | ‘We believe it is best we cook dinner before Juan’s wrinkles are easily visible.’ |

| | d. | *Nos | parece mejor que, a Juani, | cocinemos | la | cena |

| | | 1PL.DAT | seems better that Juan.DAT | we-cook | the | dinner |

| | | antes | de que se | lei | vean las arrugas | fácilmente. |

| | | before | of that RFL | 3SG.DAT | see the wrinkles | easily |

| | | ‘We believe it is best we cook dinner before Juan’s wrinkles are easily visible.’ |

| | Wh-island |

| | e. | A Ismaeli | no sé | cómo | podríamos | averiguar | si |

| | | Ismael.DAT not I-know | how | we-could | guess | if |

| | | se | lei | ven las arrugas | fácilmente. |

| | | RFL | 3SG.DAT | see the wrinkles | easily |

| | | ‘As for Ismael, I don’t know how we could figure out whether his wrinkles are easy to see.’ |

| | f. | Las arrugasi, no sé | cómo | podríamos | averiguar | si |

| | | the wrinkles not I-know | how | we-could | guess | if |

| | | a Juan | se | le | ven proi | fácilmente. | |

| | | Juan.DAT | RFL | 3SG.DAT | see pro | easily | |

| | | ‘As for Ismael’s wrinkles, I don’t know how we could figure out whether they are easy to see.’ |

| | g. | A Ismaeli, las arrugask, no sé | cómo | podríamos | averiguar |

| | | Ismael.DAT the wrinkles not I-know | how | we-could | guess |

| | | si se | lei | ven | prok | fácilmente. |

| | | if RFL | 3SG.DAT | see | easily | |

| | | ‘As for Ismael, I don’t know how we could figure out whether his wrinkles are easy to see.’ |

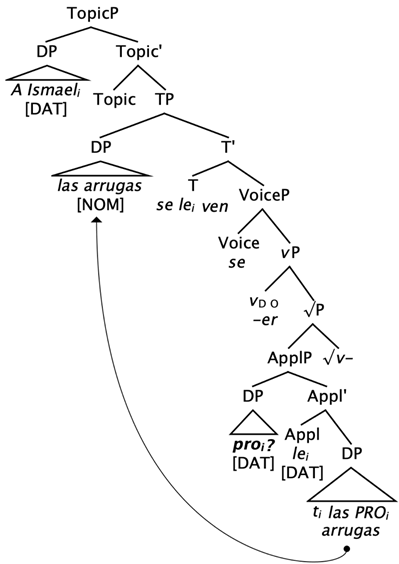

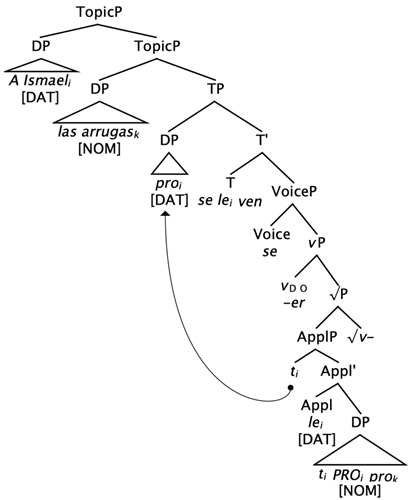

The middle-passive examples in (34), which contain dative DPs, mirror the contrasts of those in (33), involving CLLD configurations. Therefore, we can establish that middle-passive constructions with preverbal lexical DPs—dative or otherwise—are instances of CLLDs. I propose that the derivation of a middle-passive sentence where both a dative possessor DP and the theme DP appear preverbally is the following:

| (35) | a. | A Ismael, las arrugas, se le ven fácilmente. |

| | b. | ![Languages 09 00015 i008]() |

Assuming

Rizzi’s (

1997) cartographic approach to the sentence’s left periphery, whereby left-dislocated constituents merge in recurring Topic projections outside the sentence, the dative possessor DP

a Ismael and theme DP

las arrugas in (35) are base generated extrasententially inside two different Topic projections. These two constituents corefer with two empty pronouns inside the sentence; the

pro standing for the external possessor originates inside the possessum DP containing the

pro coreferring with

las arrugas, specifically in Spec,nP, from where it binds the PRO in Spec,NP. The possessor argument, unable to be case-marked inside the possessum DP, exits it and raises to the specifier of the low applicative head, where it licenses dative case. When T° looks down to probe a DP to check its EPP feature, it finds the possessor

pro in Spec,ApplP first, for it is the closest one to T°, and it probes it to its specifier. Because the possessor argument is already case-marked, T° later assigns nominative case to the null possessee via Agree, which also triggers verbal agreement. In this derivation, no intervention effects arise, minimality is respected, and the desired word order is obtained. Furthermore, this proposal harkens back to classic analyses contending that preverbal subjects in Spanish are CLLDs, such as

Contreras (

1976),

Olarrea (

1996), and

Ordóñez and Treviño (

1999), or

Barbosa (

1996) for European Portuguese.

Something is still to be said about middle-passive sentences with quantified DPs, like (36).

| (36) | Dice que a Ismaeli, | que [ninguna arruga]k (*que) se lei | ve |

| | says that Ismael.DAT | that none | wrinkle that RFL 3SG.DAT | see |

| | fácilmente. | | | |

| | easily | | | |

| | ‘He says that none of Ismael’s wrinkles is easily visible.’ |

In (36), the negatively quantified theme DP

ninguna arruga appears to have raised to the preverbal subject position over the null pronoun standing for the external possessor in argument position, i.e., in Spec,ApplP; note that the theme’s quantificational reading is obtained, and it cannot be followed by a complementizer. In other words, minimality seems to have been violated.

Barbosa (

2009) explains that there is a subset of quantificational expressions that are fronted by A’-movement without requiring contrastive focus, and this seems to be one of those cases. Therefore, I propose that the negatively quantified theme in (36) is fronted and adjoined to an A’-position above the null external possessor in Spec,TP, as shown in (37).

| (37) | Dice que a Ismaeli, que [TP [ninguna arruga]k [TP proi [T se lei ve tk fácilmente]]] |

Evidence for the fronting of this constituent via A’-movement comes from the fact that in Asturian, as well as in other Romance languages like European Portuguese (cf.

Barbosa 2009), when these quantificational expressions appear preverbally, they trigger proclisis (38c), as in other contexts where A’-movement takes place; this is shown in (38d).

| (38) | a. | Les engurries | vénse-y | fácil. |

| | | the wrinkles | see.RFL-3SG.DAT | easy |

| | | ‘His wrinkles are easily visible.’ |

| | b. | A Ismaeli | vénse-yi | les engurries | fácil. |

| | | Ismael.DAT | see.RFL-3SG.DAT | the wrinkles | easy |

| | | ‘Ismael’s wrinkles are easily visible.’ |

| | c. | Diz que a Ismaeli, que nenguna engurria se-yi | ve fácil. |

| | | says that Ismael.DAT that none | wrinkle RFL-3SG.DAT | see easy |

| | | ‘He says that none of Ismael’s wrinkles is easily visible.’ |

| | d. | A ISMAELi | se-yi | ven | les engurries fácil. |

| | | Ismael.DAT | RFL-3SG.DAT | see | the wrinkles easy |

| | | ‘It is Ismael’s wrinkles that are easily visible.’ |

In this section, I have shown evidence supporting the idea that preverbal lexical dative and theme DPs in Spanish middle-passive constructions are left-dislocated constituents coreferring with empty pronominals in argument position, i.e., CLLDs. This analysis avoids the intervention effects that a low applicative analysis of dative possessors in these structures would run into, if we assume that lexical DPs are generated inside the sentence, specifically, when accounting for the derivation where both the dative possessor DP and theme DP occur preverbally. In the next section, I will discuss how these data can be accounted for within a biclausal analysis of left dislocations (

Ott 2014,

2015).

4.2. Biclausal/Paratactic Approach

Base generation and movement analyses of CLLDs face what some authors call Cinque’s paradox (

Cinque 1983,

1990;

Ott 2014,

2015), i.e., while dislocated XPs are extrasentential constituents, in some respects, they behave as though they have moved from within the host clause. On the one hand, base-generation accounts must posit that the dislocated constituent and the resumptive element in CLLDs enter a special type of binding chain in order to derive the connectivity between the two, as well as their sensitivity to strong islands. On the other, movement approaches must find answers for CLLDs’ insensitivity to weak islands, lack of weak crossover effects, ability to license parasitic gaps, and the lack of subject–verb inversion in languages like Spanish (

Ott 2014,

2015).

Recently,

Ott (

2014,

2015) elaborated a noncartographic analysis of left dislocations that appears to be able to do away with said paradox. This author claims that left-dislocated XPs are elliptical sentence fragments surfacing in linear juxtaposition to their host clause; in other words, dislocated constituents do not move to or are base generated in a left-peripheral projection. According to this author, two clauses are parallel, differing only in that CP1 contains Σ, i.e., the segment fragment, whereas the host clause contains K in its place, a free weak proform that is cross-sententially connected to Σ, thus enabling redundant material to delete. The biclausal representation of a Spanish CLLD is sketched in (39):

| (39) | [CP1 Ya leímos [Σ ese libro]i ] | |

| | | [CP2 ya [K lo]i leímos] |

| | ‘That book, we already read it.’ |

Technically, the two sentences in (39) are not syntactically connected, but doubly endophorically linked through cataphoric ellipsis and anaphoric K; semantically speaking, the second sentence is a reformulation of the first one. Finally, the fact that the dislocate constituent merges in the specifier of a left-peripheral projection in monoclausal analyses does not explain how this constituent is case-marked or how it receives its theta role; on the other hand, under a biclausal approach, Σ and K bear an identity relation because they enter identical case and theta relations in their respective clauses.

Because preverbal dative DPs and subject DPs in middle-passive sentences are left dislocated, a biclausal analysis of these configurations would involve three juxtaposed CPs, the third of which, the host CP, has two proforms, i.e., two Ks, one standing for the dative possessor and another one instantiating the theme argument, as shown in (40). The three CPs would account for the fact that each dislocated element may surface preceded by the complementizer que and in different intonational contours.

| (40) | [CP1 (que) [Σ1 a IsmaelDAT]i se le ven las arrugas fácilmente] |

| | | [CP2 (que) a IsmaelDAT se le ven [Σ2 las arrugasNOM]k fácilmente] |

| | | | [CP3 (que) [K1 proDAT]i se le ven [K2 proNOM]k fácilmente] |

Alternatively, cases where the theme and dative DPs surface preverbally, the former preceding the latter, would be derived as follows:

| (41) | [CP1 (que) a IsmaelDAT se le ven [Σ2 las arrugasNOM]k fácilmente] |

| | | [CP2 (que) [Σ1 a IsmaelDAT]i se le ven las arrugas fácilmente] |

| | | | [CP3 (que) [K1 proDAT]i se le ven [K2 proNOM]k fácilmente] |

The derivations in (40) and (41) still account for the fact that the dative possessor—be it a full DP or an empty pronominal—is the structurally higher constituent, and therefore, the closest one to T°, for it sits in the specifier of ApplP, whereas the theme DP merges in Appl’s complement position. Consequently, T° will always probe the dative possessor to its specifier, never the theme DP, thus, avoiding any potential minimality violation.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, I have examined data from Spanish middle-passive constructions containing dative possessor DPs. These arguments originate inside the possessum DP and raise to the specifier of a low applicative of possession head to be case-licensed. I showed that an applicative analysis of these structures runs into a minimality violation when accounting for the configuration where both the dative possessor DP and the theme DP occur preverbally, if we assume that the former is left dislocated and the latter sits in the preverbal subject position: here, Spec,TP. When Tº looks down to probe a DP to its specifier, it would have to skip an empty pronominal in SpecApplP standing for the possessor, in order to attract the theme DP in argument position.

| (42) | ![Languages 09 00015 i009]() |

Instead, I have provided evidence supporting the idea that preverbal lexical dative and theme DPs are CLLDs coreferring with empty pronominals in argument position. Thus, the null dative possessor pronoun in Spec,ApplP will always raise to Spec,TP, while the empty theme pronoun will remain inside the verbal domain, therefore avoiding any intervention effects.

| (43) | [a Ismaeli][las arrugask][TP proi [T se lei ven [VoiceP [vP [√P [ApplP ti [Appl le [DP prok]]] √v-]]]]] |

Moreover, the fact that these constituents are extrasentential straightforwardly derives their unmarked preverbal position and their aforementioned status as sentential topics. Finally, I have also explored how these data can be successfully analyzed within a biclausal analysis of left dislocations, whereby left-dislocated XPs are elliptical sentence fragments surfacing in linear juxtaposition to their host clause. These constituents do not move to or are base generated in a left-peripheral projection; instead, two clauses are parallel, differing only in that CP1 contains Σ, i.e., the segment fragment, whereas the host clause contains K in its place, a free weak proform that is cross-sententially connected to Σ, thus enabling redundant material to delete. This type of approach also avoids any minimality violation.

| (44) | [CP1 (que) [Σ1 a IsmaelDAT]i se le ven las arrugas fácilmente] |

| | | [CP2 (que) a IsmaelDAT se le ven [Σ2 las arrugasNOM]k fácilmente] |

| | | | [CP3 (que) [K1 proDAT]i se le ven [K2 proNOM]k fácilmente] |

The data presented in this study contribute to the much-debated position that preverbal subjects and dative DPs occupy in Spanish, aligning with classic proposals by

Contreras (

1976),

Olarrea (

1996), and

Ordóñez and Treviño (

1999), who claim that Spanish preverbal subjects are left-dislocated constituents. Similarly,

Barbosa (

1996) arrived at the same conclusion for preverbal subjects in European Portuguese. Moreover, these results also support

Baker’s (

1995) intuitions for polysynthetic languages, where lexical DPs merge extrasententially and are coindexed with empty pronominals in argument position. Finally, further research is still required to establish whether this is a common trend in other Romance languages as well; I leave this question open for future inquiry.