Abstract

Collocations are one of the most studied types of word combinations. Their intricate nature, based on varying degrees of restriction, begs the question as to how modifications in their typical form influence the way they are processed by native speakers and learners. In this study, an eye-tracking experiment was carried out. We compared native speakers and learners of Italian when processing typical (i.e., common) and atypical (i.e., uncommon) collocations of Italian. Atypical collocations were developed by manipulating the grammatical and lexical components of a set of typical collocations. We also investigated how the online processing was affected by the different modifications (i.e., lexical and grammatical) performed and proficiency levels included. Both kinds of modifications disrupt collocation processing, with lexical modification being generally more salient than grammatical modification in terms of processing costs. Further, proficiency level influences phraseological processing, with varying effects related to the different kinds of modifications. The findings of our study are largely in line with previous research, while providing new insights into how lexis and grammar affect phraseological processing. They contribute to the evidence on languages other than English, a still under-researched domain in second language acquisition as a whole.

1. Introduction

Phraseological units, specifically collocations, are highly conventionalised word combinations that differ in terms of frequency and lexical and semantic properties, such as compositionality and lexical fixedness (Cowie 1998; Howarth 1998; Siyanova-Chanturia and Pellicer-Sánchez 2018). In this study, we define collocations—adopting the frequency-based approach (Evert 2005)—as frequently repeated and statistically significant co-occurrences (Moon 1998; Biber et al. 1999, p. 998) “whose semantic and/or syntactic properties cannot be fully predicted from those of its components” (Evert 2005, p. 1).

One theory that explains the pervasiveness of collocations is lexical priming theory (Hoey 2005), which argues that collocations result from “psychological” associations between words. This psychological association “is evidenced by their occurrence together in corpora more often than is explicable in terms of random distribution” (2005, p. 5). In the lexical priming theory, collocations are postulated as “a psycholinguistic phenomenon” which can be explained in terms of the psycholinguistic phenomenon of priming (Meyer and Schvaneveldt 1971), a mechanism whereby a word (e.g., doctor) is recognised faster when it is preceded by a related word (e.g., nurse) than when it is preceded by an unrelated one (e.g., lion).

As Hoey (2005) argues, priming mechanisms are at the root of collocation learning and use. Language users store information about the tendency of words to co-occur with other words in the mental lexicon. Further, collocations are produced in a predictable way because of the priming relationships between their constituents. For instance, when speakers encounter the first element of a collocation (e.g., heavy), they easily recall the second one (e.g., rain) and produce the collocating form (e.g., heavy rain).

Collocation mastery facilitates fluent language use and quick processing of linguistic input (Henriksen 2013). Recent research indicates that native speakers and fluent learners process collocations faster than novel phrases, driven by the familiarity and frequency of phraseological sequences (Siyanova-Chanturia and Van-Lancker Sidtis 2018). Further, the processing advantage of collocations over novel phrases suggests that experienced language users keep track of co-occurrence information in their mental lexicon.

While lexical priming theory suggests similarities in collocation processing between native speakers and learners, differences arise from learners’ exposure to the target language (Hoey 2005). Indeed, studies on this topic have highlighted differences in the processing of phraseological sequences between native speakers and learners. While native speakers demonstrate faster processing of phraseological units compared to novel phrases, this is not always the case in learners. This difference may stem from learners having less experience with the target language than native speakers (Hoey 2005): more proficient learners with a greater amount of experience with the L2 are expected to process collocations similarly to native speakers, unlike less proficient learners who have limited experience with the target language.

Aligning with Hoey’s theory (Hoey 2005), usage-based models assert that L1 and L2 mental lexicons are shaped by frequency of occurrences (Abbot Smith and Tomasello 2006; Bod 2006). L2 learning—as well as L1 acquisition—can be constructed as a statistical accumulation of language experience through exposure to linguistic input (Bod 2006)1. Learners, like native speakers, show sensitivity to the frequency of occurrences of single words and phrase units (Bod 2006).

Associative relationships between collocations’ elements have been mostly demonstrated through the priming paradigm in both L1 and L2, proving that frequency of and exposure to collocations lead to a strong priming effect between collocations’ constituents (Durrant and Doherty 2010; Wolter and Gyllstad 2011; Cangır et al. 2017; Toomer and Elgort 2019; Öksüz et al. 2020; Cangır and Durrant 2021). Recent eye-tracking studies confirm the facilitative effects of collocations, mainly attributed to conventionality and frequency (Sonbul 2015; Vilkaitė 2016; Carrol and Conklin 2020; Vilkaitė-Lozdienė 2022). However, most of the eye-tracking studies have mainly targeted English, with little consideration for languages other than English (LOTEs), and compared typical collocations with atypical word pairs at a lexical level by replacing one of the collocations’ constituents (Sonbul 2015; Carrol and Conklin 2020). Morphological and grammatical violations between the elements of a collocation have received less attention in previous publications within the literature.

One unanswered question is whether collocational elements prime each other during online processing and whether collocations retain their processing advantage when they are modified at a grammatical level. Furthermore, there is still a need to investigate whether learners’ proficiency modulates L2 processing. Indeed, more advanced learners, having more experience with L2, may process phraseological combinations (e.g., collocations) like native speakers, contrary to less advanced learners.

To bridge these gaps, this study employs the eye-tracking procedure in Italian to analyse L1 and L2 collocation processing. We investigated how native speakers and two groups of learners (intermediate and advanced) of Italian process typical Verb+Noun collocations (e.g., allacciare la cintura, ‘put on the belt’) over modified phrases (e.g., collegare la cintura, ‘connect the belt’). We considered both lexical and grammatical modifications to investigate whether both variations disrupt the priming mechanisms at the root of collocation recognition during online processing.

The impact of lexical and grammatical modifications on collocation processing is explored, along with potential differences between L1 and L2 processing. We assume that typical collocations are processed faster during online processing with respect to modified collocations due to their conventionality and to the priming relationships between their elements. Further, we expect differences in L1 and L2 processing as phraseological units are more entrenched in native speakers’ mental lexicon with respect to learners’ mental lexicon as learners have had less experience with L2 phraseological units compared to native speakers (Hoey 2005; Siyanova-Chanturia and Martinez 2015). However, we expect a role of learners’ proficiency, with advanced learners processing collocations and their modifications more similarly to native speakers compared to intermediate learners as they have had a great amount of experience with the target language (Hoey 2005).

To this end, the next section reviews previous studies that have investigated different kinds of phraseological units with a focus on collocations, on the basis of eye-tracking data and through stimuli modification, while identifying some of the remaining gaps which the present study seeks to address.

1.1. Evidence from Previous Eye-Tracking Studies

Recent studies have employed eye-tracking to investigate whether modified phraseological units maintain their processing advantage and the extent of the cost associated with altering their form (Kyriacou et al. 2021; Senaldi et al. 2022; Vilkaitė-Lozdienė 2022). In this review, we focus on eye-tracking studies that have investigated the processing of different types of phraseological units by modifying their typical form.

Studies on the processing of idiom modification indicate that modified idioms retain their processing advantage due to their familiarity. For instance, passivised idioms are processed faster than their control phrases as well as their active counterparts when used figuratively (Kyriacou et al. 2020). Further, modifying typical idioms with the insertion of adjectives (spill the [spicy/red] beans) induces longer reading times, although their final word is processed easily, suggesting that modifying an idiom does not impede idiom recognition (Kyriacou et al. 2021). Furthermore, language users show difficulties in the processing of modified idioms when used in their figurative sense (Hauser et al. 2020).

Similar findings emerge from research on other types of phraseological sequences. Processing of binomials (bride and groom) and their reversed forms (groom and bride) has been investigated in native speakers and learners with different levels of proficiency (Siyanova-Chanturia et al. 2011). Native speakers and advanced learners were found to be sensitive to the configuration (binomial vs. reversed) in which a phrase occurred. On the contrary, low-proficiency learners read binomials and their reversed forms in a similar way (Siyanova-Chanturia et al. 2011). Further, replacing binomials’ elements (king and queen vs. prince and queen/king and prince) produces a processing cost (Carrol and Conklin 2020), while inserting a non-typical conjunction in a binomial (salt and pepper vs. salt and also pepper) did not affect the processing advantage of typical binomials over control conditions (Chantavarin et al. 2022).

We now turn to eye-tracking studies that investigate the processing of collocations by altering their typical phrasal template. Sonbul (2015) looked at online collocational processing in native speakers and learners of English. She focused on Adjective+Noun collocations (e.g., fatal mistake) and created control phrases by replacing the adjective of the target collocations with a synonym (e.g., awful) and with a non-collocate (e.g., extreme), obtaining low-frequency collocations and non-attested word pairs. Results reveal that high-frequency collocations exhibit an early processing advantage, with proficiency having minimal impact. This processing advantage of high-frequency collocations over low-frequency and non-attested collocations disappeared in the late stages.

Further, Vilkaitė (2016) and Vilkaitė and Schmitt (2017) highlight the influence of adjacency on processing speed. Adjacent (provide information) and non-adjacent (provide some of the information) collocations were processed faster than their control conditions by native speakers. Similarly to native speakers, learners processed adjacent collocations faster than their control conditions (Vilkaitė and Schmitt 2017). Furthermore, investigation into morphological variations of collocations indicate that different morphological forms do not diminish their processing advantage over control phrases (Vilkaitė-Lozdienė 2022).

The reviewed studies yield three key insights: (1) phraseological units are processed faster than novel phrases, suggesting the evidence of priming effects that are driven by different properties; (2) modified phraseological units (e.g., passivised idioms and non-adjacent collocations) are not always processed slower than control phrases, suggesting that elements of a phraseological unit still recall each other despite variations in the form; and (3) native speakers and advanced learners process phraseological units in a similar way, indicating that the mechanisms at the basis of L1 and L2 processing might be the same.

Despite these findings, there is a gap in understanding the impact of both lexical manipulation and grammatical violation on the online processing of phraseological units, especially in languages with high inflectional variability (e.g., Italian). Existing studies have primarily focused on modifying individual components without altering grammatical structure, leaving a need for empirical evidence.

Recently, the eye-tracking technique has been employed in the investigation of the L1 and L2 processing of morphosyntactic features. Hopp and León Arriaga (2016) explored whether L2 learners whose L1 does not use differential object marking (e.g., German) process Spanish case marking in a native-like way. Results indicate that, while native speakers showed processing difficulties in all types of case violations, L2 learners demonstrated differential sensitivity to case marking in online processing. Further, Lim and Christianson (2015) carried out an eye-tracking study to investigate how Korean learners of English show sensitivity to subject–verb agreement violations. Participants read a series of English sentences, half of which contained subject–agreement violations in English. Researchers found that the sensitivity of learners to agreement violation was modulated by their proficiency: advanced learners showed processing difficulties in reading morphological violations.

However, there is a lack of empirical evidence on whether grammatical information is accessed during online processing of phraseological units with the exception of a few studies that suggest that altering the syntactic and morphological structure of phraseological units does not always produce a processing cost (Kyriacou et al. 2020, 2021, 2022; Vilkaitė-Lozdienė 2022). We argue that grammatical violation could be helpful in understanding more deeply how phraseological units are processed. Thus, it could be helpful to better understand whether a grammatical violation disrupts the priming mechanism at the root of the processing of phraseological units. On the one hand, grammatical violations are potentially problematic for language users, as well as lexical or syntactic modifications. Indeed, a disruption may indicate that grammatical information is accessed during real-time processing of phraseological units and a grammatical violation might negatively affect the recognition of the phraseological sequence. On the other hand, grammatical violations may not be problematic as they alter the form of phraseological units to a lesser extent with respect to lexical manipulations, and language users should be able to recognise a phraseological unit despite the grammatical violation.

To address this gap, we investigated how native speakers and learners processed typical and non-typical collocations in Italian, a still under-researched language in the field of phraseological processing, especially when considering languages exhibiting inflectional variability. In doing so, we observed whether and how lexical and grammatical modifications affected online processing. We argue that lexical and grammatical manipulations can help us to investigate whether the alteration of both the grammatical and lexical structure of a collocation affects the real-time processing of collocations and whether there are similarities or differences between L1 and L2 processing.

1.2. The Present Study

The present research aims to explore whether lexical manipulation and grammatical violation equally disrupt the processing of typical Italian collocations. Previous studies created control phrases of typical phraseological units by replacing constituents with synonyms or non-attested collocates, showing that lexical manipulation affects the processing of phraseological units. However, to the best of our knowledge, previous studies did not focus on altering the grammatical structure of a phraseological sequence. Thus, we still do not know whether grammatical violations disrupt phraseological processing to a similar extent as lexical manipulations do.

In the present study, we address the following research questions:

- How do native speakers and learners process typical collocations compared to their modified counterparts?

- To what extent do grammatical violations and lexical manipulations disrupt the processing of collocations in native speakers and learners?

- How does proficiency influence the processing of typical and non-typical collocations in learners of Italian?

To investigate these research questions, we extracted a series of stimuli from a reference corpus of L1 Italian (Spina 2014) on the basis of specific quantitative measures (i.e., phrase frequency, usage, and log dice). We then modified these stimuli at the level of lexis (i.e., by replacing the element of a collocation with a synonym) and grammar (i.e., by inserting an agreement error between collocation’s elements). Subsequently, we developed an eye-tracking experiment, which we administered to both native speakers and learners of Italian, in order to evaluate the processing of typical (i.e., non-manipulated) and non-typical (i.e., modified) Verb+Noun (object) combinations.

The following sections outline the characteristics of the participant sample, the criteria adopted in identifying and manipulating the stimuli, and the procedures followed in the development of the eye-tracking experiment and in analysing the collected data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Given the exploratory nature of the present study, special care was taken to select a small but homogeneous participant cohort2. Thirty-six language users (twelve native speakers (mean age = 24.3), twelve intermediate (mean age = 22) and twelve advanced (mean age = 30.5) learners of Italian) took part in the study. Native speakers were undergraduate and graduate students enrolled at Sapienza University of Rome, while learners were either students on exchange programs or professionals with a secondary or higher level of education. Classification of learners into intermediate and advanced groups was based on their language certification or on the Italian language class in which they were enrolled. Learners had either obtained certification of their Italian proficiency in the past or were currently studying Italian at an intermediate or advanced level (based on the Common European Framework of Reference, CEFR) in a language course. All participants were asked to fill out a pre-test questionnaire with some basic personal information for screening and technical purposes (name, age, and whether they had normal or corrected-to-normal vision). Native speakers all had Italian as their sole L1, while learners came from the following L1 backgrounds: Spanish (7); French (5); Romanian (3); German (2); Polish (2); Bulgarian (1); Georgian (1); Greek (1); Korean (1); and Portuguese (1). Learners completed a language background questionnaire reporting their prior experience with the Italian language. They further rated their speaking, writing, listening, and reading skills on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very poor; 2 = weak; 3 = ok; 4 = good; 5 = excellent). Table 1 summarises learners’ experience with and knowledge of Italian. A lexical decision task in Italian, which assessed participants’ vocabulary (LexITA, Amenta et al. 2021), was administered to both native speakers and learners. Intermediate learners scored a median of 38/60 points on the LexITA, while advanced learners scored a median of 51/60 on the same test. As expected, native speakers ranked higher on the vocabulary test (Median = 59/60) and served as a control group.

Table 1.

Learners of Italian self-reported L2 experience.

2.2. Identification of Stimuli

In this section, we illustrate how the stimuli used in the eye-tracking experiment were identified on the basis of corpus-derived data and how they were then manipulated. A total of twelve Verb+Noun (object) collocations were extracted from the DICI-A (Spina 2016), a dictionary for second language learners of Italian collocations, classified into different CEFR levels. The DICI-A is based on the Perugia Corpus (Spina 2014), a reference corpus of L1 Italian, containing over 26 million tokens and consisting of 10 different textual genres (i.e., academic writing; administration; movies; literature; spoken language; essay writing; school essays; newspapers; television; and web). Only CEFR levels A (i.e., basic proficiency levels, A1 and A2) and B (i.e., intermediate proficiency levels, B1 and B2) from the dictionary were considered. Three lists were compiled for each level: one based on phrasal frequency, one based on usage, and one based on log dice. Phrase frequency is defined as the total number of occurrences for the entire combination. Usage is defined as the product of phrase frequency and the dispersion of the collocation (i.e., to what extent the collocation occurs in the different sections of the reference corpus). Log dice3 is defined as a measure of collocation strength that expresses “the tendency of two words to co-occur [...] in the corpus” (Gablasova et al. 2017, p. 164). All measures were calculated using the Perugia Corpus (Spina 2014). The top two collocations were selected from each of the three lists (phrase frequency; usage; log dice) in each of the two levels (levels A and B of the DICI-A). This allowed us to identify our stimuli by considering three different measures and the importance of the information they are each able to convey. Care was taken to avoid the repetition of collocates among the different collocations, in order to prevent bias or priming effects in the stimuli. These stimuli were left intact.

Six of the identified stimuli were modified lexically, while the other six were modified grammatically. The selection of stimuli for each type of modification was performed at random. The lexical manipulation was performed so as to produce a combination not attested in our reference corpus of L1 Italian, the Perugia Corpus. The manipulation was conducted on the basis of the following procedure: first, a collocation from the randomised list of stimuli was selected; second, the list of synonyms of the verb contained in the collocation was retrieved from the online Treccani4 vocabulary and sorted according to usage; third, the first verb in the list was chosen and its length, in terms of letters, and frequency were checked against the original one in order to make sure there would be no significant differences in this respect5; fourth, the presence of the verb in the lexical syllabi for the A and B CEFR levels was then checked, so as to ensure that the verb would have a good likelihood of being recognised by the learners; and finally, the manipulated combination was looked up in the Perugia Corpus, in order to verify whether it exhibited an occurrence equal to zero, despite the semantic affinity between the two verbs. For example, the collocation passare + esame (‘pass + exam’) was changed into *attraversare + esame (*‘pass through + exam’). The other six collocations were modified grammatically by inserting an agreement error between the article and noun that were part of the collocation. In half of the cases, the agreement error was inserted in the article. For example, aprire gli occhi (‘open the[plural] eyes[plural]’) was transformed into aprire lo occhi (‘open the*[singular] eyes[plural]’). In the other half of the cases, the agreement error was inserted in the noun. For example, vivere una esperienza (‘live an[singular] experience[singular]’) was transformed into vivere una esperienze (‘live an[singular]experiences*[plural]’). Table 2 shows the final set of the stimuli. Finally, original collocations and their modified counterparts were controlled for length (in terms of letters) at the phrase level in order not to have phrase length differences between conditions (Original collocations length: Mean = 16; SD = 3.06; Lexically manipulated collocations length: Mean = 16; SD = 2.52; Grammatically violated collocations: Mean = 16; SD = 2.95).

Table 2.

Final set of original and manipulated stimuli.

Original and manipulated collocations were embedded in 24 context sentences, half of which contained intact collocations. The other half contained a lexical manipulation (6), a grammatical manipulation with the agreement error inserted in the noun (3), and a grammatical manipulation with the agreement error inserted in the article (3). A sample sentence in each condition is provided below:

- Quando siamo in macchina è molto importante allacciare la cintura/*collegare la cintura anche nei sedili posteriori. (Original/Lex manipulation)(When we are in the car, it is very important to fasten the belt also in the back seats);

- Svegliarsi in vacanza e aprire gli occhi/aprire *lo occhi davanti al mare è la cosa più bella del mondo. (Original/Art manipulation)(Waking up on holidays and opening the eyes in front of the sea is the most gorgeous thing in the world);

- Lea è abituata ad accendere una sigaretta/accendere una *sigarette fuori dalla scuola per fumarla insieme al fratello. (Original/Noun manipulation)(Lea is used to lighting a cigarette outside the school to smoke with her brother).

2.3. Procedure

For the screen-based eye-tracking experiment, we used Tobii Pro Lab (1.118 version; sample rate = 600 Hz). Participants sat approximately 60 cm (23″) from the screen and were asked to use a chin rest to avoid head movements. Before starting the calibration routine, we made sure that participants could easily reach for the mouse while looking at the screen. Calibration was assessed on a nine-point grid, and the procedure was run as many times as needed to minimise artifacts. Stimuli were presented centrally on a 24″ monitor with a 1920–1080 pixel resolution. Sentences were written in yellow on a black background using a monospaced font (Courier new) on a single line of text. In addition to the final set of critical stimuli (24), we inserted 24 fillers and 24 pairs of yes–no questions. Participants were asked to read silently for comprehension and then to click the mouse button to move forward, while questions needed to be answered out loud. Critical stimuli and distractors were arranged together in 4 randomised blocks, which in turn were interchanged with 4 sequential blocks for question pairs. Therefore, a total of 9 alternate groups made up the trial, including the initial set of instructions and practice items. Due to the small sample of participants and stimuli, they were not counterbalanced in different lists. Thus, participants saw all the 24 experimental items. It could not be excluded that participants may have noticed similarity across the original and the variant collocations. However, care was taken in not inserting original collocations and their variant forms in the same experimental block.

2.4. Data Analysis

Areas of Interest (AOI) were drawn for each item over the Verb+Noun (object) region (see Table 2, second column). In order to reduce the risk of obtaining zero-value data points, gaze plots and heatmaps were visually inspected to establish the height of the AOI and to adjust its position on the text in relation to the participants’ actual eye trajectory. Within these areas, we analysed the number of fixations and the total duration of fixations6.

As we were interested in investigating how native speakers and learners process typical and non-typical Verb+Noun (object) collocations, with respect to different conditions (i.e., original, grammatical violation, and lexical manipulation), we considered only total duration of fixations (i.e., total reading time), as it is acknowledged that integration from processing difficulties is more likely to happen in the final stages of real-time comprehension (Siyanova-Chanturia and Pellicer-Sánchez 2018).

We used mixed-effect modelling (Cunnings and Finlayson 2015; Gries 2015; Linck and Cunnings 2015; Murakami 2016) to analyse eye-tracking data. Linear mixed-effects models were separately run for each of the two measures of total duration of fixations (TDF) and number of fixations (NF). As, in this last case, the dependent variable is discrete, we used a generalised linear mixed-effect model with a Poisson distribution when fitting the model. The numeric response variable (TDF) was used with its log-transformed score to avoid skewness in the data and improve model fit. Continuous predictors were scaled and centred. Table 3 provides a summary of the numeric dependent variables for each experimental condition.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the dependent variables for each condition.

In order to model variation due to individual differences in the processing of typical and non-typical collocations, participants and items were included in the models as a random effect, by fitting by-subject and by-item random intercepts and slopes for each of them (Barr et al. 2013; Brown 2021).

The following predictors were included in each of the two models as fixed effects: Proficiency as a three-level factor (native, intermediate, and advanced); LexITA (the score assessing vocabulary knowledge); Condition as a three-level factor (original, lexical, and grammatical); and Length (in number of letters). The native and the original condition were each set as the reference levels in all analyses. Further, we included collocation length because of its acknowledged potential effect on the online processing of single words and multi-word expressions (Kliegl et al. 2004; Ellis et al. 2008; Rayner 2009). Neither frequency nor association measures were included as predictors, as these were the values that guided the identification of stimuli as well as the selection of high-frequency and strongly associated combinations. Stimuli did not differ in phrase frequency and association measure; they were balanced for phrase frequency and log dice. Since we hypothesised a relationship between Condition and Proficiency, the models included an interaction between these two predictors. Table 4 provides a summary of the two numeric variables included as fixed effects.

Table 4.

Summary of numeric variables included in the models as fixed effects.

We built the two models using R (Version 4.1.3; R Core Team 2022) and the R package lme4 (Version 1.1-28; Bates et al. 2015). For each of the two models, we adopted a top–down stepwise approach for the model selection procedure (Gries 2015). We started with a model that included the most comprehensive structure, with a maximum number of fixed effects and interactions. Initially, by-item and by-subject intercepts and slopes were included as random effects, but due to singularity issues, models were simplified to by-subject and by-item intercepts (Kyriacou et al. 2021, p. 21). We then explored fixed effects to create the optimal structure. At each step of this model selection process, we used likelihood ratio tests to compare pairs of models and to find the best fit (Baayen et al. 2008) as well as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), which indicates the amount of variance that is left unexplained by the model (Cunnings 2012). Finally, we compared each of the two final models to the respective null model that contained only the random effects. Assumptions of the final models (linearity, normality of residuals, normality of random effects, and homogeneity of variance) were checked by producing validation graphs. Finally, we checked for multicollinearity using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF): all VIF scores were smaller than 2 (Zuur et al. 2009, p. 387). p values of each predictor were estimated by using the lmerTest package (version 3.1-3); effect sizes for each significant effect were measured using effectsize package (version 0.8.3).

3. Results

Table 5.

Fixed effects and interactions of Model 1 with logarithmic TDF as a dependent variable.

Table 6.

Fixed effects and interactions of Model 2 with NF as a dependent variable.

Model 1 (a linear mixed-effects model with TDF as a dependent variable) provided a significantly better fit in comparison to the baseline model (χ2(8) = 20.44, p < 0.01). Its total explanatory power is substantial (conditional R2 = 0.31) and the part related to the fixed effects alone (marginal R2) is equal to 0.08. The fact that the fixed effects account for less variability than the random ones indicates that the variability is due more to the individual behaviour of participants than to the influence of the independent variables. Model 2 (a generalised mixed-effect model with NF as a dependent variable) fitted significantly better with respect to the baseline model (χ2(8) = 28.163, p < 0.001). The explanatory power of Model 2 is substantial (conditional R2 = 0.39) and the part related to the fixed effects alone (marginal R2) is equal to 0.10. Again, the variability is due more to the individual behaviour of learners than to fixed effects. Although the sample and the number of stimuli are rather limited, the two models have strong explanatory power and produce cohort results that answer our research questions. Specifically, we wanted to investigate three different aspects, specifically whether i. typical collocations are processed faster than their modified counterparts by native speakers and learners; ii. whether grammatical and lexical modification produce a processing cost in native speakers and learners; and iii. whether proficiency level influences the processing of typical and modified collocations in learners of Italian.

We start the description of results from the model based on the processing measure (i.e., TDF; Model 1). Proficiency was found to significantly affect (effect size = 0.50) reading times, with intermediate (β = 0.16; SE = 0.05; t = 3.448; p < 0.01) and advanced (β = 0.12; SE = 0.05; t = 2.564; p = 0.01) learners showing longer reading times with respect to native speakers. Further, Condition (effect size = 0.44) strongly affected the online processing of collocations with lexically manipulated collocations read significantly slower than original collocations (β = 0.13; SE = 0.06; t = 2.291; p = 0.02). The negative effect of the interaction between Proficiency and Condition on the reading times of the different types of conditions suggests that collocations were not processed symmetrically across the three levels of proficiency. However, the interaction between Proficiency and Condition had a weak effect on the reading times of collocations (effect size = 0.09) and barely reached the threshold of significance at the level of intermediate learners and lexical condition (β = −0.09; SE = 0.04; t = −1.94; p = 0.05) suggesting that intermediate learners took more time in reading lexically manipulated collocations compared to native speakers. No significant difference was found between advanced learners and native speakers. Although the interaction between Proficiency and Condition weakly affected the reading times of learners and native speakers in the three experimental conditions, this suggests a non-symmetrical processing of collocations across the three levels of proficiency.

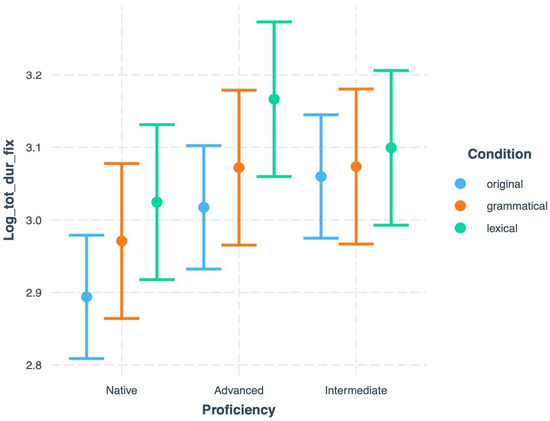

We further investigated more deeply the interaction by plotting it (Figure 1). Native speakers read original collocations faster than grammatically violated and lexically manipulated collocations; the same pattern of processing emerged in advanced speakers who took more time in reading collocations with both lexical manipulation and grammatical violation compared to the original collocations. Although the difference was less marked in the intermediate level of proficiency (Figure 1), intermediate learners also processed original collocations faster than the grammatically and the lexically modified collocations. The most striking effect concerned lexically manipulated collocations: their reading times significantly increased in the intermediate learners compared to native speakers (Table 5).

Figure 1.

The interaction between Proficiency and Condition on the TDF measure.

Moving to Model 2, the one with NF as a dependent measure, the first relevant finding is that this model, based on the number of fixations, shows similar results to those obtained in Model 1, suggesting a correlation between the processing measures and the quantitative measures. Proficiency (effect size = 0.19) affected the number of fixations on the AOIs. Consistent with what was observed for processing times, intermediate learners (β = 0.36; SE = 0.09; z = 3.764; p < 0.001) and advanced learners (β = 0.24; SE = 0.09; z = 3.764; p < 0.001) fixated on collocations more frequently than native speakers. We also observed a significant effect of Condition (effect size = 0.10): grammatically violated (β = 0.26; SE = 0.11; z = 2.28; p = 0.02) and lexically manipulated collocations (β = 0.25; SE = 0.11; z = 2.16; p = 0.03) elicited a number of fixations higher than the number produced on the original collocations. Although its effect size was small (=0.10), Proficiency and Condition significantly interacted on the NF. Specifically, grammatically violated collocations were fixated on more frequently by intermediate learners with respect to native speakers (β = −0.24; SE = 0.08; z = −2.93; p < 0.01). Further, although the threshold of significance was barely reached, intermediate learners produced more fixations on lexically manipulated collocations compared to native speakers (β = −0.16; SE = 0.08; z = −1.95; p = 0.05). Again, no significant difference was found between native speakers and advanced learners.

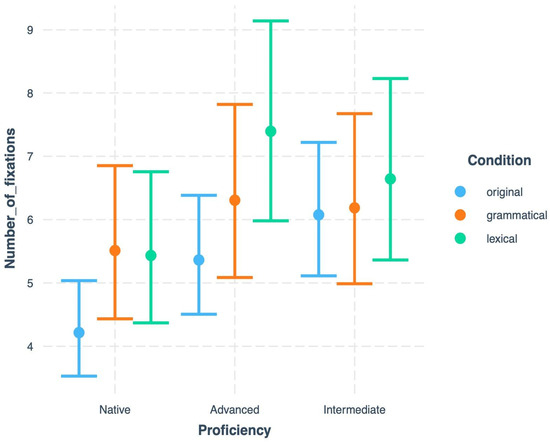

As Figure 2 suggests, the intermediate and advanced learners showed a similar pattern to the one found in the analysis of the reading times (Model 1); both intermediate and advanced learners fixated more often on the modified collocations (with lexically manipulated collocations fixated on more frequently than grammatically violated collocations) with respect to native speakers. Again, the difference is more marked in advanced learners than in intermediate learners (Figure 2). Contrary to learners, native speakers fixated in a similar way on the collocations under the two conditions of modifications with respect to the original ones, although they showed a difference in reading times (Figure 1). However, the difference in the number of fixations on lexically manipulated and grammatically violated collocations was significant only between intermediate learners and native speakers (Table 6).

Figure 2.

The NF predicted by the interaction between Proficiency and Condition.

To investigate more deeply any possible difference in the processing of original collocations and modified collocations between intermediate and advanced learners, we built the two models again, following the same procedure described above but setting the intermediate as the reference level. Model 3 (the one with TDF as a dependent measure and intermediate level as the baseline for comparisons) shows a significant effect of the interaction between Proficiency and Condition. Specifically, advanced learners took more time in reading lexically manipulated collocations with respect to intermediate learners (β = 0.10; SE = 0.05; t = 2.346; p = 0.01). Consistently, Model 4 (the one with NF as a dependent measure and intermediate level as the baseline for comparisons) shows similar results to the third model. The interaction between Proficiency and Condition significantly affects the number of fixations on the AOIs with the advanced learners fixating more frequently on the collocations with lexical manipulation compared to intermediate learners (β = 0.23; SE = 0.07; t = 2.961; p < 0.01). Results of the two new models indicate a significant difference between intermediate and advanced learners in reading and fixating on lexically manipulated collocations.

4. Discussion

This study was aimed at exploring the following three main aspects of phraseological processing in native speakers and learners: first, whether typical collocations are processed faster than their manipulated counterparts; second, whether different kinds of stimuli manipulation (lexical and grammatical) equally affect the processing of identified collocations in three samples of participants; and third, whether proficiency can modulate processing dynamics under different conditions. In order to investigate these issues, we selected twelve collocations on the basis of three quantitative corpus-based measures and then modified them lexically (by replacing the verb of the collocation with a synonym) and grammatically (by inserting an agreement error between the article and the noun of the collocation). We then developed an eye-tracking experiment which was administered to thirty-six participants (twelve native speakers, twelve intermediate, and twelve advanced learners of Italian). We analysed the total duration of fixations and number of fixations through mixed-effects modelling. In the following subparagraphs, we discuss one research question at a time and then we address how our results can provide new insights into the processing of phraseological units through different kinds of stimuli manipulation.

- RQ1: How do speakers and learners process typical collocations compared to their manipulated counterparts?

Our first research question addressed the issue of whether conventional Verb+Noun collocations are processed faster than their manipulated counterparts by L2 intermediate leaners, L2 advanced leaners, and native speakers of Italian. Both the TDF and the NF models exhibit a similar linear pattern: in both cases, in fact, the reading times and the number of fixations increase in modified collocations compared to typical collocations. Specifically, lexically manipulated and grammatically violated collocations were read slower compared to original collocations and both lexically and grammatically violated collocations received more fixations compared to original stimuli. In our models, the differences are significant between the intermediate leaner and native speaker groups and between the advanced and intermediate learners. On the contrary, advanced learners and native speakers did not process collocations and their manipulated counterparts differently.

This finding confirms the processing advantage of typical phraseological units over control conditions found in the literature (Siyanova-Chanturia et al. 2011; Vilkaitė 2016; Kyriacou et al. 2020; Carrol and Conklin 2020). Siyanova-Chanturia et al. (2011) found that native speakers and advanced learners were sensitive to the configuration of binomials and they read binomials faster than their reversed forms. Moreover, Sonbul (2015) focused on Adjective+Noun collocations and found a processing advantage of the typical form of collocations over their non-typical forms only in the early stages of processing both in native speakers and learners but not in late measures. Contrary to Sonbul (2015), we did find a processing advantage of typical collocations over their modified phrases in the final stages of processing. We hypothesise that the difference between our results and Sonbul’s (2015) might be due to the fact that Adjective+Noun collocations are likely to be perceived as less restricted by language users than Verb+Noun collocations. In light of a lower degree of restriction, speakers might be more tolerant of deviant collocations (Sonbul 2015). On the contrary, our results are in line with the findings of Vilkaitė (2016) and Vilkaitė and Schmitt (2017). The authors report a processing advantage of adjacent and non-adjacent typical collocations over their control phrases in native speakers. However, the processing advantage of non-adjacent typical collocations over their control conditions was not found in learners, which is not in line with our findings that show that learners process original collocations faster than their control phrases. Keeping together our results and the results of previous studies, we argue that the processing advantage of typical collocations over atypical collocations could be explained by a lexical priming mechanism through collocation elements (Hoey 2005). When our participants read the first element of collocations, they expected the second element, and satisfaction of this expectation (original condition) resulted in less reading time of original collocations compared to modified collocations.

Our results are also in line with usage-based theories of language learning. In this theoretical framework, language learning is seen as a result of the entrenchment of lexical connections which is, in turn, determined by frequency of exposure. The occurrence of a word combination within our concrete experience with the language leaves a trace which will then facilitate the processing of subsequent occurrences of the same (or similar) word combination(s) (Kemmer and Barlow 2000; Ellis et al. 2008; Hoey 2005). As a result, learners who have had a more limited exposure to the target language in general and with the typical, most frequent combinations characterising that language will have a reduced processing advantage related to phraseological units in comparison to other learners with more extensive experience and with native speakers. Our findings, in fact, show non-significant differences between advanced learners and native speakers in the processing of stimuli. This finding is fairly in line with previous research (Siyanova-Chanturia et al. 2011), where advanced learners exhibited a similar behaviour to native speakers, with no marked differences.

- RQ2: To what extent do grammatical violations and lexical manipulations disrupt the processing of collocations in native speakers and learners?

Stimuli manipulation produced a processing cost in terms of reading times and number of fixations. We then asked how different types of manipulations (i.e., grammatical and lexical) are processed in native speakers and learners. Here, again, we noticed a similar pattern for both the TDF and the NF models for the learners’ measurements. On the contrary, for native speakers, the two models slightly differ: we observe larger differences in reading times than in fixation counts over the two types of manipulations. Further, intermediate learners took more time in processing lexically manipulated collocations compared to native speakers. Interestingly, advanced learners processed more slowly and fixated more frequently on lexically manipulated collocations compared to intermediate learners. On the contrary, no significant difference was found between advanced learners and native speakers. Indeed, for both native speakers and advanced learners, the total reading time gradually increased from the typical to the non-typical collocations, but more interestingly, the largest values were found for lexical transformations in both cases.

Lexical manipulation significantly affected the processing times of modified collocations compared to grammatical violation. This finding suggests that altering the typical form of a collocation could disrupt the priming mechanisms at the root of collocation processing (Hoey 2005). Indeed, when readers encountered a synonym of the verb that substituted the first element of the collocation, the recall of the second element of the collocation was not prompted and readers could not expect the second constituent. This mismatch in expectation resulted in a longer reading time for the lexically manipulated collocations than for the intact collocations. Interestingly, grammatical violation did not significantly produce a processing cost. Grammatical violation did not alter the form of the typical collocations. Thus, an agreement error between collocation elements could not disrupt the priming mechanism at the root of collocation processing and readers could be more tolerant with grammatical violations compared to lexical manipulations.

However, grammatical violation as well as lexical manipulation significantly affected the number of fixations, with grammatically violated collocations receiving more fixations compared to original collocations. This result suggests that grammatical information is integrated during online processing as readers noted the agreement error between collocation elements, which is in line with previous research (Lim and Christianson 2015). However, contrary to lexical manipulation, grammatical violation did not significantly increase reading times, suggesting that readers recovered more quickly from agreement error between collocation elements compared to lexical substitution. Thus, lemma manipulation is still more salient than phrase-level grammatical incongruency.

All things considered, our findings show that lexical and grammatical manipulation disrupt the processing of collocations in native speakers and learners, with lexical manipulation being more problematic than grammatical manipulation. On the contrary, a clear distinction between lexical and grammatical manipulation was not found in intermediate learners. Further, native speakers and advanced learners took more time in reading both lexically and grammatically manipulated collocations compared to typical collocations, suggesting that they might have activated a compositional route in resolving the processing cost induced by manipulated items.

- RQ3: How does proficiency influence the processing of typical and non-typical collocations in learners of Italian?

We now turn to our third research question. As we have seen, both the TDF and the NF models show significantly different values for intermediate learners compared to advanced learners. This result is in line with previous studies which confirmed a significant effect of proficiency on phraseological processing (Siyanova-Chanturia et al. 2011; Vilkaitė and Schmitt 2017) with the exception of Sonbul (2015), who found no evidence of proficiency interacting with the processing of Adjective+Noun collocations in L2 learners.

Both learner groups processed lexically manipulated collocations slower than original collocations. Interestingly, intermediate learners took less time to read and fixated less on frequent collocations with lexical manipulation compared to advanced learners. Further, the difference in the processing and number of fixations between the original collocations and their modified counterparts is less marked in intermediate learners compared to advanced learners. This could depend on the fact that intermediate learners may be less aware of lexical restrictions on collocations compared to advanced learners, as they have less experience with the target language and, thus, they might be more tolerant of deviations from the typical form of collocations. Further, our results found no evidence of a significant difference between native speakers and advanced learners, showing a similar trend in the processing of collocations and their counterparts between the two groups. This is in line with Hoey’s (2005) and usage-based theories, which are based on the entrenchment of connections due to exposure to and experience with the target language. Specifically, in the lexical priming theory (Hoey 2005), there may be little difference between the mechanisms at the root of the collocation process when comparing native speakers and learners. The key difference between native speakers and learners is exposure to the target language. Therefore, the more learners are exposed to the target language, the more they process collocations in a similar way to native speakers, as our results showed.

5. Conclusions

We investigated how native speakers and learners (intermediate and advanced) of Italian processed phraseological units that were lexically and grammatically modified. Our results showed that lexical and grammatical modifications produce a processing cost, confirming that typical collocations are processed faster during online processing then their manipulated counterparts. Moreover, intermediate learners processed lexically manipulated collocations differently than native speakers and advanced learners, while advanced learners showed a processing pattern similar to native speakers.

However, some limitations need to be considered. First of all, although this is an exploratory study and the power of the models is substantial, the first critical point concerns the small sample of items and participants. Increasing the number of items and subjects in future studies could reach a stronger significant effect and more powerful models. Second, another limitation concerns the eye-tracking measures analysed in this study: we looked only at the final stages of processing as we were interested in how participants recover from processing disruptions. However, in future research, early eye-tracking measures should also be taken into account to investigate whether grammatical and lexical violations affect the early stages of reading.

As far as we are aware, no previous study has deeply looked into how both lexical and grammatical manipulations affect collocation processing. As we focus on both the lexical and grammatical levels of phraseological units, our aim is to suggest new insights into the relationship between direct and a compositional processing of phraseological units. In this regard, our results suggest that both native and learner groups have access to the internal structure of collocations. This is in line with recent studies that have suggested that highly fixed phraseological sequences (e.g., idioms) have an internal structure and their constituents are partly analysed during online processing. We assume that this processing advantage might be due to the salient properties of collocations (frequency and conventionality) and to the priming relationship between collocations’ elements (Hoey 2005). Altering the internal structure of collocations at both lexical and grammatical levels disrupts the priming mechanisms at the root of collocation processing. However, grammatical violations are less problematic—as they do not alter the typical form of a collocation—compared to lexical manipulations.

Further, looking at learners’ data, it should be pointed out that advanced learners process original and modified collocations in a more similar way to native speakers compared to intermediate learners. According to Hoey’s theory (Hoey 2005) and usage-based models, language acquisition is based on the entrenchment of connections due to exposure to the language. It is likely that advanced learners tend to process collocations in a more similar way to native speakers and they are more exposed to L2 than intermediate learners. With a greater amount of exposure, learners are more likely to become sensitive to phraseological units’ properties and to process them as native speakers do.

Finally, our results, together with findings from previous studies, confirm that collocation processing is driven by priming mechanisms and modifying collocations at both a lexical and grammatical level disrupts those mechanisms at the root of collocation processing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.F., L.F., M.R., S.S. and S.K.G.; methodology, I.F., V.D. and M.R.; data collection, V.D. and M.R.; data analysis, I.F. and S.S.; data curation, I.F.; writing–original draft preparation, I.F., L.F., V.D. and S.S.; writing–review editing, I.F., L.F., V.D., M.R. and S.S.; visualization, I.F.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, S.S.; funding acquisition, S.S. and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research; grant number PRIN 20178XXKFY.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study can be found here: https://osf.io/npqvj/?view_only=2eb14dc471a2470b8e5d2855a33d4946 (accessed on 16 December 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Experience with language can be defined as the cumulative exposure a speaker has with a language. In the view of usage-based models, experience with language is accumulated whenever the speaker in exposed (i.e., comes into contact) with language (Tomasello 2003; Bod 2006). Experience changes each time the speaker is exposed to the linguistic input. Therefore, exposure to the target language shapes linguistic experience (Bod 2006). Language acquisition can be viewed as a statistical accumulation of language experience. In the case of L1 acquisition, the speaker is currently exposed to and surrounded by linguistic input, which enables firmer acquisition of language structures and vocabulary. In contrast, in L2 acquisition, the learning context is different, and learners are less exposed to the target language (i.e., in the case of foreign language). This makes second-language learning more vulnerable. However, greater exposure to the L2 involves greater accumulation of language input, which strengthens L2 learning. |

| 2 | The number of participants is lower than what is usually found in similar studies. This is motivated by the fact that this study is part of a larger exploratory study aimed at evaluating the relationship between production and processing of phraseological units in a group of Italian L2 learners. As we wanted to connect production data with processing data based on the same sample of participants, the number was inevitably low. This affected the parallel study (i.e., the present one), in which the aim was not to compare production and processing of phraseological units in a single sample of participants but rather to compare native and learners with respect to the single dimension of processing. |

| 3 | We used log dice instead of MI—the canonical association measure employed in identifying collocations in corpora—as, contrary to MI, it is not dependent on corpus dimensions. Considering the small size of our reference corpus, we used log dice to derive a more reliable and standardised measure of association. |

| 4 | https://www.treccani.it/vocabolario (accessed on 1 March 2021). |

| 5 | t-tests show no significant difference in length (t (8) = −0.193; p = 0.85) as well as in frequency (t (9) = 0.387; p = 0.71) between the original and the manipulated verb. |

| 6 | These measures are most commonly known as total reading time and fixation count. However, we adopt the terms used in the software version employed in collecting the data for the present study. |

References

- Abbot Smith, Kirsten, and Michael Tomasello. 2006. Exemplar-learning and schematization in a usage-based account of syntactic acquisition. The Linguistic Review 23: 275–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenta, Simona, Linda Badan, and Marc Brysbaert. 2021. A quick and reliable assessment tool for Italian L2 receptive vocabulary size. Applied Linguistics 42: 292–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baayen, Rolf H., Doug J. Davidson, and Douglas M. Bates. 2008. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language 59: 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Cristoph Scheepers, and Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68: 255–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, Douglas M., Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad, and Edward Finegan. 1999. Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Bod, Rens. 2006. Exemplar-Based Syntax: How to get productivity from examples. The Linguistic Review 23: 275–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Violet A. 2021. An Introduction to Linear Mixed-Effects Modeling in R. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 4: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangır, Hakan, and Philip Durrant. 2021. Cross-linguistic collocational networks in the L1 Turkish-L2 English mental lexicon. Lingua 258: 103057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangır, Hakan, S. Nalan Büyükkantarcıoğlu, and Philip Durrant. 2017. Investigating Collocational Priming in Turkish. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies 13: 465–86. [Google Scholar]

- Carrol, Garreth, and Kathy Conklin. 2020. Is all formulaic language created equal? Unpacking the processing advantage for different types of formulaic sequences. Language and Speech 63: 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantavarin, Suphasiree, Emily Morgan, and Fernanda Ferreira. 2022. Robust Processing Advantage for Binomial Phrases with Variant Conjunctions. Cognitive Science 46: e13187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, Anthony P. 1998. Phraseology: Theory, Analysis, and Applications. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cunnings, Ian. 2012. An overview of mixed-effects statistical models for second language researchers. Second Language Research 28: 369–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunnings, Ian, and Ian Finlayson. 2015. Mixed effects modeling and longitudinal data analysis. In Advancing Quantitative Methods in Second Language Research. Edited by Luke Plonsky. New York: Routledge, pp. 159–81. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant, Philip, and Alice Doherty. 2010. Are high-frequency collocations psychologically real? Investigating the thesis of collocational priming. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory 6: 125–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Nick C., Rita Simpson-Vlach, and Carson Maynard. 2008. Formulaic language in native and second language speakers: Psycholinguistics, corpus linguistics, and TESOL. TESOL Quarterly 42: 375–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evert, Stefan. 2005. The Statistics of Word Cooccurrences. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stuttgart University, Stuttgart, Germany. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gablasova, Dana, Vaclav Brezina, and Tony McEnery. 2017. Collocations in corpus-based language learning research: Identifying, comparing, and interpreting the evidence. Language learning 67: 155–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, Stefan Th. 2015. The most under-used statistical method in corpus linguistics: Multi-level (and mixed-effects) models. Corpora 10: 95–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, Katja I., Shari Baum, and Debra A. Titone. 2020. Effects of aging and noncanonical form presentation on idiom processing: Evidence from eye-tracking. Applied Psycholinguistics 42: 101–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, Birgit. 2013. Research on L2 learners’ collocational competence and development—A progress report. In L2 Vocabulary Acquisition, Knowledge and Use. Edited by Camilla Bardel, Christina Lindqvist and Batia Laufer. Eurosla Monographs Series, 2. Amsterdam: EuroSLA, pp. 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hoey, Michael. 2005. Lexical Priming: A New Theory of Words and Language. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hopp, Holger, and Mayra E. León Arriaga. 2016. Structural and inherent case in the non-native processing of Spanish: Constraints on inflectional variability. Second Language Research 32: 75–108. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth, Peter. 1998. Phraseology and second language proficiency. Applied Linguistics 19: 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmer, Michael, and Suzanne Barlow. 2000. Introduction: A usage-based conception of language. In Usage-Based Models of Language. Edited by Michael Barlow and Suzanne Kemmer. Stanford: CSLI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kliegl, Reinhold, Ellen Grabner, Martin Rolfs, and Ralf Engbert. 2004. Length, frequency, and predictability effects of words on eye movements in reading. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology 16: 262–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, Marianna, Kathy Conklin, and Dominic Thompson. 2020. Passivizability of Idioms: Has the Wrong Tree Been Barked Up? Language and Speech 63: 404–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriacou, Marianna, Kathy Conklin, and Dominic Thompson. 2021. When the Idiom Advantage Comes Up Short: Eye-Tracking Canonical and Modified Idioms. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriacou, Marianna, Kathy Conklin, and Dominic Thompson. 2022. Ambiguity resolution in passivized idioms: Is there a shift in the most likely interpretation? Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology 77: 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Jung H., and Kiel Christianson. 2015. Second language sensitivity to agreement errors: Evidence from eye movements during comprehension and translation. Applied Psycholinguistics 36: 1283–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linck, Jared A., and Ian Cunnings. 2015. The utility and application of mixed-effects models in second language research. Language Learning 65: 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, David E., and Roger W. Schvaneveldt. 1971. Facilitation in recognizing pairs of words: Evidence of a dependence between retrieval operations. Journal of Experimental Psychology 90: 227–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Rosamund. 1998. Frequencies and forms of phrasal lexemes in English. In Phraseology: Theory, Analysis and Applications. Edited by Anthony P. Cowie. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, Akira. 2016. Modeling systematicity and individuality in nonlinear second language development: The case of English grammatical morphemes. Language Learning 66: 834–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öksüz, Doğuş, Vaclav Brezina, and Patrick Rebuschat. 2020. Collocational Processing in L1 and L2: The Effects of Word Frequency, Collocational Frequency and Association. Langauge Learning 1: 55–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, Keith. 2009. Eye movements in reading: Models and data. Journal of Eye Movement Research 2: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaldi, Marco S. G., Junyan Wei, Jason W. Gullifer, and Debra Titone. 2022. Scratching your tête over language-switched idioms: Evidence from eye-movement measures of reading. Memory & Cognition 50: 1230–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyanova-Chanturia, Anna, and Ron Martinez. 2015. The Idiom Principle Revisited. Applied Linguistics 36: 549–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyanova-Chanturia, Anna, and Ana Pellicer-Sánchez, eds. 2018. Understanding Formulaic Language: A Second Language Acquisition Perspective. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Siyanova-Chanturia, Anna, and Diana Van-Lancker Sidtis. 2018. What online processing tells us about formulaic language. In Understanding Formulaic Language: A Second Language Acquisition Perspective. Edited by Anna Siyanova-Chanturia and Ana Pellicer-Sánchez. New York: Routledge, pp. 38–61. [Google Scholar]

- Siyanova-Chanturia, Anna, Kathy Conklin, and Walter J. B. Van Heuven. 2011. Seeing a phrase “time and again” matters: The role of phrasal frequency in the processing of multiword sequences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 37: 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonbul, Suhad. 2015. Fatal mistake, awful mistake, or extreme mistake? Frequency effects on off-line/online collocational processing. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 18: 419–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, Stefania. 2014. Il Perugia Corpus: Una risorsa di riferimento per l’italiano. Composizione, annotazione e valutazione. In Proceedings of the First Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics CLiC-it 2014. Edited by Roberto Basili, Alessandro Lenci and Bernardo Magnini. Pisa: Pisa University Press, pp. 354–59. [Google Scholar]

- Spina, Stefania. 2016. Learner corpus research and phraseology in Italian as a second language: The case of the DICI-A, a learner dictinary of Italian collocations. In Collocations Cross-Linguistically. Corpora, Dictionaries and Language Teaching (Mémoires de la Société Néophilologique de Helsinki). Edited by B. Sanromán. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, pp. 219–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, Michael. 2003. Constructing a Language. A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Toomer, Mark, and Irina Elgort. 2019. The development of Implicit and Explicit Knowledge of Collocations: A Conceptual Replication and Extension of Sonbul and Schmitt (2013). Language Learning 69: 405–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaitė, Laura. 2016. Are nonadjacent collocations processed faster. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 42: 1632–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaitė, Laura, and Norbert Schmitt. 2017. Reading Collocations in an L2: Do Collocation Processing Benefits Extend to Non-Adjacent Collocations? Applied Linguistics 40: 329–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaitė-Lozdienė, Laura. 2022. Do Different Morphological Forms of Collocations Show Comparable Processing Facilitation? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 48: 1328–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, Brent, and Henrik Gyllstad. 2011. Collocational links in the L2 mental lexicon and the influence of L1 intralexical knowledge. Applied Linguistics 32: 430–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuur, Alain F., Elena N. Ieno, Neil Walker, Anatoly A. Saveliev, and Graham M. Smith. 2009. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).