Abstract

Romance free choice items (FCIs) are frequently pointed out as resulting from the grammaticalization of the relative determiner qual ‘which’ and an element derived from a volition verb, such as querer ‘want’. Contrary to other Romance FCIs, Portuguese qualquer ‘any’ remains understudied, therefore motivating the current research. In this article, I investigate the syntax and semantics of qualquer, from a diachronic perspective, based on examples extracted from 13th and 14th century texts. Analysis of contexts of occurrence of qualquer showed that, in Old Portuguese, the elements qual and quer could combine in different configurations, corresponding to different structures. On the one hand, the relative determiner qual could combine with a form of the volition verb in ever free relative clauses. On the other hand, qual and quer were also combined in appositive relative clauses, which seem to be at the core of postnominal qualquer. However, similar to what is argued for Old Spanish, qualquer was also a quantifier-like element, occurring in prenominal position and giving rise to universal interpretations. The different origins of prenominal and postnominal qualquer may help explain the different readings in contemporary data.

1. Introduction

The term free choice item (FCI) was first coined by Vendler (1967) to refer to a particular property of the English item any: its freedom of choice. The term has been used to refer to items that can express both quantification and indetermination, giving rise to universal and existential readings, as illustrated with the English FCI any in (1) and (2), respectively:

| (1) | Any student will pass the exam. |

| (2) | Take any apple from the basket. |

In (1), any student can be considered equivalent to every student, therefore conveying a universal reading, while in (2), any apple carries an existential reading. This seems to be a feature of FCIs in general and not exclusive of English any and has been a central topic of debate within the semantic analysis of FCIs (cf. Giannakidou 2001).1

The fact that these items allow both universal and existential readings poses the problem of knowing whether they should be considered universal quantifiers (cf. Dayal 2004) or existential indefinites (cf. Giannakidou 2001).

Despite the considerable amount of literature on the topic, FCIs have been mainly studied from a synchronic point of view and the diachronic perspective is still roughly explored. Nevertheless, the origin and syntactic/semantic features of FCIs in old stages of a language can help shed some light on their synchronic interpretation.

The comparison of some FCIs in Romance languages shows that these items share a common origin: they frequently result from the combination of a relative determiner or pronoun with a verbal form, most likely a volition or a copula verb, in the early stages of the language (cf. Lombard 1938; Haspelmath 1995). This is the case of Spanish items cualquier(a) ‘whatever’, quienquiera ‘whoever’, and dondequiera ‘wherever’ (cf. Rivero 1986, 1988; Company Company and Pozas Loyo 2009; Company Company 2009; Mackenzie 2019; Elvira 2020); Italian qualsiasi and qualunque ‘whatever’ (cf. Degano and Aloni 2021; Kellert 2021); and Catalan qualsevol (cf. Colomina I Castanyer 2002) and Galician calquer ‘whatever’ (cf. Ferreiro 1999), among others.

Old Portuguese data show that the relative determiner qual ‘which’ was frequently combined with a form of the volition verb querer ‘want’ in ever free relative clauses. Nevertheless, I argue that this is probably not the direct source of Portuguese FCI qualquer.

This paper aims to (i) provide empirical data on early uses of the FCI qualquer, while offering a syntactic and semantic description of its properties; (ii) argue against the idea that Portuguese qualquer directly results from ever free relative clauses with an additional internal head; (iii) put forth the hypothesis that prenominal and postnominal uses of qualquer have different origins and emerge in different chronological periods, resulting in the existence of a prenominal qualquer with quantifier-like properties and a postnominal qualquer with adjectival properties in Old Portuguese.

FCI qualquer in Synchrony

Before looking at the properties of qualquer in Old Portuguese, I briefly refer to the values and uses associated with the contemporary item qualquer, in order to highlight the possible differences regarding diachronic uses of the item.

First of all, it is worth mentioning that contrary to the vast literature surrounding the English FCI any, there are not many studies on Portuguese qualquer. We highlight the work by Móia (1992a), Peres (1987, 2013), and Moreno (2009), which offer mainly a semantic description of the item; and the works by Pires de Oliveira (2005) and Medeiros (2022), which analyze qualquer in the Brazilian variety. All of these works have in common the need to account for the several different interpretations displayed by qualquer, according to its position regarding the noun and the combination with other indefinite elements.

Qualquer associates with nouns and is traditionally paired either with indefinite pronouns or with quantifiers due to the different interpretations it may trigger. Nevertheless, as Peres (2013) observes, none of the classifications seems to totally translate the behaviour of qualquer.

Let us look at examples (3) and (4):

| (3) | Qualquer | criança | faz | birra | quando | lhe | dizem | ‘não’ |

| any | child | do.3sg.Pres. | tantrum | when | her.3sg.Dat | say.3pl.Pres. | ‘no’ | |

| ‘Any child will make a tantrum when told ‘no’.’ | ||||||||

| (4) | Não | devias | conduzir | tão | depressa. | Qualquer | dia | apanhas |

| neg | should.3sg.Imp. | drive | so | fast | any | day | catch.2sg.Pres. | |

| um | susto. | |||||||

| a | fright | |||||||

| ‘You shouldn’t drive so fast. One of these days you will be given a fright.’ | ||||||||

As can be seen from the comparison between the two contexts, qualquer can trigger a universal reading as in (3), being interpreted as every child. On the other hand, it can also convey an existential reading, as in (4), where it is equivalent to a day, does not matter which. This duality of meanings is usually a feature associated with other FCIs, as we have mentioned before.

Apart from the universal and the existential readings, qualquer may also trigger other values and combine with other elements within the determiner phrase (DP). Peres (2013) accounts for three different values associated with qualquer, namely ‘equivalence’, ‘unknown’, and ‘restriction’ values,2 as exemplified below:

| (5) | Será que ele tem quaisquer hipóteses de vencer (por poucas que sejam)? |

| ‘I wonder if he has any chances of winning (no matter how few).’ |

| (6) | Eu já li qualquer livro desse autor (não sei qual). |

| ‘I already read some book by this author (I don’t know which).’ |

| (7) | O presidente não recebe qualquer pessoa. |

| ‘The president will not receive anyone.’ | |

| (Peres 2013, p. 798)3 |

The examples above all display qualquer in the prenominal position. However, contrary to FCIs such as any, qualquer may also occur in the postnominal position. In this last configuration, there is usually the presence of the indefinite determiner um ‘a’ before the noun and a tendency to favour readings with depreciative flavour as in (8).4

| (8) | Ela não era uma rapariga qualquer. |

| ‘She was not an ordinary girl.’ |

The combination with the indefinite determiner um ‘a’ and the values assumed by qualquer under such a configuration have motivated the proposal by Móia (1992a), with the distinction between three values for qualquer: universal, existential, and cardinal.

Qualquer also combines with the indefinite outro ‘other’, allowing different word orders, as illustrated from (9) to (11):

| (9) | Qualquer outra pessoa teria sido mais simpática. |

| ‘Any other person would have been nicer (apart from this one).’ |

| (10) | Outra qualquer pessoa teria sido mais simpática. |

| ‘Any other person would have been nicer.’5 |

| (11) | Outra pessoa qualquer teria sido mais simpática. |

| ‘Another person, no matter who, would have been nicer.’ |

The major difference in meaning is found between (9) and (11), showing that prenominal and postnominal qualquer do not always produce the same interpretation. While in (9), prenominal qualquer can refer to every single person, except a particular one, in (11), the existence of at least one person apart from the one at stake is presupposed. I will not elaborate on the issue here (but cf. Peres 1987 and Móia 1992a for a detailed description of contemporary data).

Qualquer does not occur with absolute pronominal reading, as, for instance, the indefinites alguém ‘someone’ or ninguém ‘anyone/no one’. Instances such as (12) are considered ungrammatical6 in contemporary data (agrammaticality is indicated by *), even though they are registered in 13th and 14th century texts. It can, however, occur in partitive constructions both in prenominal and postnominal positions as in (13) and (14), respectively:

| (12) | *Qualquer que seja corajoso vencerá a batalha |

| ‘Whoever that is brave will win the battle.’ |

| (13) | Qualquer (um) dos vestidos te fica bem. |

| ‘All of the dresses suit you well.’ |

| (14) | Um vestido qualquer dos que compraste ontem fica-te bem. |

| ‘Any random dress from the ones you bought yesterday suits you well.’ |

In (13) and (14), qualquer occurs with a partitive prepositional phrase (PP). According to Pires de Oliveira (2005), the presence of the partitive construction determines that the set of alternatives underlying the freedom of choice of qualquer must be known to the speaker. This type of context lacks investigation and raises several questions regarding the indefinite or quantificational nature of qualquer.

Despite the presence of the partitive PP in (13) and (14), there are crucial differences, resulting from the position occupied by qualquer. First of all, only in (13) is the presence of the indefinite um ‘a’ optional. Secondly, only in (13) is the partitive PP being directly selected by qualquer. Partitive complements are traditionally selected by quantifiers, which would position prenominal qualquer as a quantifier-like element.

As far as sentence (14) is concerned, the quantificational reading of qualquer in such contexts is frequently associated with the presence of um. However, the exact nature of um remains undetermined, since we can be in the presence of the indefinite determiner or the cardinal numeral. I am inclined to consider that the element um that combines with qualquer is an indefinite determiner instead of the cardinal element. The reason why I argue in this direction is related to the agrammaticality of contexts such as (16) and (17) where the adverb of exclusion só ‘only’ or the (prenominal) adjective único ‘single’ force a cardinal interpretation of um.7 If um was interpreted as a cardinal, we would expect these contexts to be felicitous, but they are not, suggesting that um is the indefinite determiner. Furthermore, cardinal um is incompatible with the idea of freedom of choice, since it is impossible to choose if the set only contains one element.

| (15) | Escolhe | uma | maçã | qualquer. | |||

| Choose | a | apple | any | ||||

| ‘Choose any apple. | |||||||

| (16) | *Escolhe | uma | só | maçã | qualquer. | ||

| Choose | a | only | apple | any | |||

| *‘Choose just one any apple.’ | |||||||

| (17) | *Escolhe | uma | única | maçã | qualquer. | ||

| Choose | a | single | apple | any | |||

| *‘Choose one single any apple.’ | |||||||

Finally, one last note on qualquer is related to the existence of the plural form quaisquer. The morpheme -s marking plural is still added after qual and not at the end of the word.8 This fact is still a reminder of the compositional nature of qualquer, as will be shown in the next sections.

2. Materials and Methods

In this section, I present a few considerations concerning the sources and methodology on which the present work relies.

The data under analysis are circumscribed to the chronological period corresponding to Old Portuguese, which comprehends the 13th and 14th centuries, roughly following the periodization proposal for Portuguese by Cintra (cf. Castro 1999).9 This short timespan seems to be crucial for the development of the FCI qualquer, since it is only during this period that we find different configurations of the construction involving the relative qual and a form of the volition verb querer ‘want’.

In order to constitute a sample corpus, searches were performed semi-automatically, by searching the word qual and extracting only the relevant examples. All sentences containing a form of qualquer were then inserted in a database, using the program FileMaker Pro 12 Advanced,10 and they were annotated with relevant information, such as the order of the elements in the compound and their position in relation to the nominal element; the presence of modifiers; tense of the verbal form querer ‘want’; and other relevant features. The encoding of the examples and the annotation of relevant parameters allowed an easier comparison of the contexts.

As far as the textual sources are concerned, for the 13th century sample, I have considered the following texts:

Demanda do Santo Graal (DSG)—the full version of the edition by Piel and Nunes (1988), in an electronic format;

Foro Real (FR)—the full version of the edition by Ferreira (1987), available online through the corpus CIPM (cf. Xavier 1993–2003);11

Legal documents edited by Martins (2001) in Documentos Portugueses do Noroeste e da Região de Lisboa (DPNRL);

Medieval Galician-Portuguese poetry (GP-poetry), in the edition compiled by Brea (1996), and available through the TMILG12 corpus platform (cf. Varela Barreiro 2004).

For the 14th century sample, I have chosen the sources below:

Crónica Geral de Espanha (CGE)—the full version of the editions by Pedrosa (2012) and Miranda (2013), as part of their masters’ thesis;

Diálogos de São Gregório (DG)—the full text of the electronic edition by Machado Filho (2013);

Dos Costumes de Santarém (DCS)—the texts written between 1340–1360, in the edition by Rodrigues (1992), available online through the corpus CIPM.

Due to the scarcity of sources for Old Portuguese, I have considered some texts which have been transmitted by later copies. That is the case of Demanda do Santo Graal (DSG), Crónica Geral de Espanha (CGE), and Medieval Portuguese-Galician poetry (GP-poetry) on which some clarifications should be added.

Starting with the DSG text, it corresponds to a 15th century copy of an allegedly early 13th century translation from French. Despite the dating issues, I have considered it to be representative of 13th century Portuguese, based on the works by Castro (1993), Toledo Neto (2012), Martins (2013), and Pinto (2021), among others.

As far as the CGE text is concerned, the edition used is based on manuscript L, which is from the first quarter of the 15th century (cf. Cintra 1951–1990) and closer to the original text from 1344 (the original manuscript, called manuscript Y by Cintra (1951–1990), was lost).

Finally, Medieval Galician-Portuguese poetry is transmitted by three manuscripts, two of which are from the end of the 15th or beginning of the 16th century (Cancioneiro da Vaticana and Cancioneiro da Biblioteca Nacional) and one from the end of the 13th century (Cancioneiro da Ajuda). The edition used by the corpus TMILG, and which we have consulted here, is based on the three manuscripts. Despite the chronology of the manuscript, they are said to reflect 13th century Portuguese.

Table 1 shows the estimated number of words contained in each text and the total number of words per century.

Table 1.

Number of words per century and text.

As one can see, the total number of words is higher in the 14th century, due to the nature of the sample, which contains a very long text (the CGE text). On the other hand, textual sources for the 13th century are not abundant, resulting in a lower number of words. I was not able to determine the number of words for the 13th century part constituted by Galician-Portuguese poetry. Searches were performed using the corpus TMILG, which contains the edition compiled by Brea (1996), but to which there is no indication of the exact number of words.

I have collected the occurrences where qualquer takes the exact same form as in contemporary Portuguese,13 but I have also considered the occurrences displaying (i) the elements qual and quer in adjacency but graphically separated (that is qual quer); (ii) the elements qual and quer separated by a lexical element (as in qual X quer); and (iii) the elements qual and quer with the previous two configurations, but with the verbal element displaying variable inflection (as in qual quiser or qual X quiser).

As Table 1 also shows, the FCI qualquer is not a frequent item in any of the texts, being, however, more expressive in the text of Foro Real (FR), representing 0.098% of all the words in the document.

The corpus has a total of 166 occurrences of qualquer, with 90 belonging to the 13th and 76 to the 14th century. It should be noticed that, despite having a higher number of total words in the 14th century, the number of occurrences found for qualquer is lower than the one for the 13th century14.

In the next sections, I present the data collected for medieval qualquer. The description of some particular syntactic features of qualquer is made under a generative grammar perspective. I very briefly refer to classical projections, such as determiner phrase (DP) (cf. Abney 1987), complementizer phrase (CP) (cf. Rizzi 1997), and quantifier phrase (QP) (Cardinaletti and Giusti 1992).

3. Qualquer in Medieval Portuguese

3.1. General Distribution and Patterns of Occurrence

The data collected shows that medieval qualquer displayed different behaviour from the contemporary item, being able to occur in some syntactic configurations that seem to have been lost after the 14th century.15

Looking at the data, we identify three main configurations for qualquer, in terms of word order. The first one corresponds to qualquer preceding a nominal element and which we call prenominal. The second configuration presents qualquer following a nominal element, therefore in postnominal position. The third configuration presents the two elements qual and quer separated by a lexical item, which, in most cases, is a noun. These cases are illustrated from (18) to (20), respectively. To these three patterns, we add a pronominal use, therefore without the presence of any nominal element, as in (21).

| (18) | […] e | rogamos | a | qualquer | Tabellion | que | esta | carta | ujr | |

| and | ask.1pl.Pres | to | any | notary | that | this | letter | see | ||

| que | faça | ende | a | carta | da | dita | partiçõ. | |||

| that | do.3sg.Pres.Subj | of.that | the | letter | of.the | said | division | |||

| ‘and we ask any notary who sees this legal document that writes the legal document of the aforementioned division.’ | ||||||||||

| (DPNRL) | ||||||||||

| (19) | […] defendemos | que | nenhua | das | pessoas | sobredictas | |||

| prohibit.1pl.Pres | that | none | of.the | persons | aforementioned | ||||

| nõ | possa | meter | a | juyzo | nenhua | villa | |||

| neg | can.3sg.Pres.Subj | put | to | judgement | none | village | |||

| nen | castello | nen | outro | herdamẽto | qualquer | ||||

| nor | castle | nor | other | property | any | ||||

| “we prohibit that none of the aforementioned people can put under trial any village, nor castle, nor any other inheritance.’ | |||||||||

| (Foro Real) | |||||||||

| (20) | […] e | manda | seu | cavallo | a | qual | parte | quer |

| and | send.3sg.Pres | your | horse | to | which | part | want | |

| pello | freo | e | o | faz | star | quando | quer | |

| by.the | bridle | and | it | make.3sg.Pres | be | when | want.3sg.Pres | |

| “and sends his horse where he wants by the bridle and makes it stand when he wants.’ | ||||||||

| (Demanda do Santo Graal) | ||||||||

| (21) | E | por | esto | maldicto | he | qualquer | que |

| and | by | this | cursed | be.3sg.Pres | anyone | that | |

| treiçom | faz, | ca | des | ally | adiante | nunca | |

| betrayal | do.3sg.Pres | because | since | there | forward | never | |

| se | nẽ huu | quer | chamar | do | seu | linhagem, | |

| se.Reflx | no one | want.3sg.Pres | call | of.the | his | lineage | |

| assy | como | foy | deste. | ||||

| this.way | as | be.3sg.Past | of.this | ||||

| ‘And for this reasone, anyone who commits betrayal is cursed, because from that moment afterwards, no one wants to be called from his lineage, as it happened with him.’ | |||||||

| (Crónica Geral de Espanha) | |||||||

These configurations reflect different syntactic structures and may be assigned to three different groups, which are adopted from this moment on. I refer to prenominal qualquer, where pronominal uses are included; postnominal qualquer, which includes instances of an already lexicalized qualquer modifying a nominal element; and finally, I refer to relative qualquer to account for the cases where the underlying structure is still a relative clause. This group includes all the examples of discontinuous qual and a verbal form of querer (which we identify as ever free relative clauses and appositive relative clauses). Table 2 presents the distribution of each pattern in terms of number of occurrences, as well as in percentage.

Table 2.

Distribution of occurrences of qualquer by source and century.

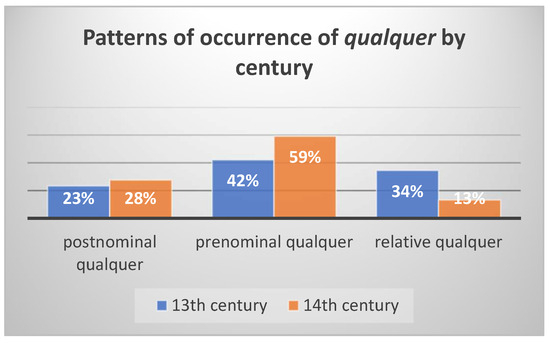

When we compare the frequency of each pattern in the two centuries, we see that there are some changes from the 13th to the 14th century, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patterns of occurrence of qualquer by century.

Figure 1 shows that prenominal qualquer was the most frequent configuration in 13th century data, followed by relative clauses with the elements qual and quer. However, while occurrences of prenominal qualquer continued to increase in the following century, the relative clause configuration decreased. Finally, there was also an increase in postnominal qualquer (N qualquer) from the 13th to the 14th century, although it is not as accentuated as in the previous configurations.

The frequencies presented above show that relative clauses with qual and quer started declining after the 13th century and ever free relatives disappeared from the language after the medieval period. On the other hand, prenominal and postnominal occurrences become the widespread patterns, probably filling in the gap left by the disappearance of the relative clause pattern.

In the following sections, I argue in favour of the existence of two items qualquer in Old Portuguese. There was a use of qual and quer associated with relative clauses (both ever free and appositive relatives) and displaying different levels of grammaticalization; and there was also a specifier qualquer, which already behaved as an independent constituent (even though it may have originated in a relative clause in a much earlier period).

3.2. Relative Qualquer

Medieval Romance FCIs are said to originate in relative clauses (cf. Rivero 1984, 1988; Haspelmath 1995; Company Company 2009). Old Portuguese also displayed relative clauses involving the relative qual and a verbal form of querer, both in adjacency and in a discontinuous configuration. In this section, we look at occurrences of qualquer that correspond to instances of relative clauses.

The relative determiner qual is said to originate in the Latin form qualis, which was used as a wh-element in interrogative and exclamative clauses, but also participated in correlative constructions with the form qualis…talis (cf. Ernout and Thomas 1972, p. 156). Its use as a relative element is not registered in Latin, though. It has, therefore, been considered a Romance innovation, but this is a question still open to debate, since some authors situate its emergence already in Latin (cf. Ramat 2005).

In Old Portuguese, qual is registered in the corresponding contexts listed for Latin qualis and as a relative determiner/pronoun, introducing relative clauses.

Data from our corpus attests the possibility in Old Portuguese, with qual being a relative determiner in combination with a form of the volition verb querer ‘want’, as illustrated in (22) and (23) bellow:

| (22) | «Certas | gram | folia | buscades.» | «Qual | folia | quer | |

| certainly | great | amusement | search.2pl.Pres | which | amusement | want.3sg.Pres | ||

| que | seja», | disse | Ivam | o | Bastardo, | «a | ||

| that | be.3sg.Pres.Subj | say.3sg.Past | Ivam | the | Illegitimate | to | ||

| mim | teer | me | convem | pois | que | o | ||

| me | have | me | suit.3sg.Pres | because | that | it | ||

| comecei | ||||||||

| start.1sg.Past | ||||||||

| ‘You certainly search for great amusement. Whichever amusement that is, said Ivam, the Illegitimate, having it suits me since I have started it.’ | ||||||||

| (Demanda do Santo Graal) | ||||||||

| (23) | mais | escolhi | tu | huma | morte | qual |

| but | choose:2sg.Imp | you | a | death | which | |

| quiseres | e | darch’a-emos | ||||

| want.2sg.Fut.Subj | and | give.1pl.Fut_it.acc | ||||

| ‘but choose any death you want and we will give it to you’ | ||||||

| (Diálogos de São Gregório) | ||||||

In (22), the element qual introduces a relative clause and combines with a verbal form quer, but the two items are separated by lexical material, namely the noun folia ‘amusement’. In fact, qual folia ‘which amusement’ corresponds to the head (that is, a head and an additional internal head) of the relative clause, while quer is the verbal form, initially selecting a clausal complement introduced by que ‘that’. This relative clause seems to be a free relative clause since there is no lexical antecedent.

On the other hand, in (23), the relative determiner qual is immediately followed by the verbal form quer, but contrary to (22), there is a nominal antecedent, which indicates that this is an appositive relative clause, modifying the noun. The two examples show us that qual and quer could combine in two types of relative clauses—free relatives and appositives.

Let us start by looking at free relative clauses. There are two different types of free relatives described in the literature: plain free relatives and ever free relatives. While it is generally assumed that plain free relatives have a definite interpretation, ever free relatives are associated with universal readings (cf. Dayal 1997). Examples (24) and (25), taken from Dayal (1997, p. 99), illustrate the two types of free relatives:

| (24) | I ordered what he ordered for dessert. (=the thing he ordered for dessert); |

| (25) | John will read whatever Bill assigns. (=everything/anything Bill assigns). |

The plain free relative in (24) produces an interpretation similar to a definite determiner phrase (DP), while the ever free relative in (25) has a prototypical universal reading.16

It is not my goal to investigate the semantics of plain and ever free relatives here (cf. Šimík 2020 for a semantic analysis), but a few comparative considerations should be made regarding ever free relatives, due to their parallel with free relatives with volition verbs in Romance languages, such as Portuguese. In Portuguese, the equivalent structure of ever free relative clauses involves the presence of an element originating from a volition verb meaning want,17 that is, the case of the element quer, which results from the third person singular form of the verb querer ‘want’ in the Simple Present Indicative, as in (26b). The pairs in (26) and (27) illustrate the differences between a plain free relative and a relative with quer in Portuguese.

| (26) | a. | Quem | vier | à | festa | irá | divertir-se | ||||||||

| who | come:3sg.Fut-Subj | to.the | party | will | have.fun | ||||||||||

| ‘Who comes to the party will have fun.’ | |||||||||||||||

| b. | Quem | quer | que | venha | à | festa | irá | divertir-se | |||||||

| who | ever | that | come.3sg.Pres.Subj | to.the | party | will | have.fun | ||||||||

| ‘Whoever comes to the party will have fun.’ | |||||||||||||||

| (27) | a. | Vou | contigo | onde | fores. | |||||

| go.1sg.Pres | with.you | where | go.2sg.Fut | |||||||

| ‘I will go with you where you go.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Vou | contigo | onde | quer | que | vás. | ||||

| go.1sg.Pres | with.you | where | ever | that | go.2sg.Pres.Subj | |||||

| ‘I will go with you wherever you go.’ | ||||||||||

Although the relative clauses in each pair (26) and (27) may refer to the same entity/place, there are differences in meaning, as well as in the syntax, with free relatives with quer being modified by a restrictive relative clause with the subjunctive mood.

Ever free relatives can be considered semantically equivalent to free relatives with quer ‘ever’ in Portuguese, as seems clear from the comparison between the pairs in (28) and (29).

| (28) | a. | I will do whatever the teacher asks me. |

| b. | I will do anything/everything the teacher asks me. |

| (29) | a. | Farei | o | que | quer | que | a | professora | peça. | ||

| do.1sg.Fut | the | what | ever | that | the | teacher | ask.3sg.Pres.Subj | ||||

| b. | Farei | qualquer | coisa/ | tudo | o | que | a | professora | peça. | ||

| do.1sg.Fut | any | thing/ | everything | the | that | the | teacher | ask.3sg.Pres.Subj | |||

As shown in (28b) and (29b), it is possible to assume both a universal and an existential reading for the two sentences since the relevant strings ‘whatever’/’o que quer’ can be replaced by anything/qualquer coisa, activating a free choice reading or by everything/tudo, which corresponds to universal quantification.

This seems to show that free relatives with quer are parallel to ever free relatives. Therefore, I adopt the term ever free relative to refer to free relatives combining the relative determiner qual and the particle quer resulting from a volition verb, whenever there is no nominal antecedent. This type of free relative clause is also known as a non-specific free relative (cf. Haspelmath 1995).

3.2.1. Ever Free Relative Clauses in Old Portuguese

Ever free relative clauses with a volition verb are frequently found in Old Portuguese texts as a strategy to introduce non-specific or indefinite references.18 Relative elements in ever free relatives can refer to [+/−human] or [+/−animate] entities, but they can also have a [+locative], [+temporal], or a [+manner] reading. Examples (30) to (35) illustrate these possibilities, with the following relative elements: quẽ ‘who’, que ‘what’, u ‘where’, quando ‘when’, como ‘how’, and qual ‘which’ in Old Portuguese:

| (30) | E | quẽ | quer | que | contra | isto | ueer | ou |

| and | who | want.3sg.Pres | that | against | this | see.3sg.Fut.Subj | or | |

| fazer | algũa | cousa | moyra | porende | e | nõ | seya | |

| do | some | thing | die | for.that | and | neg | be.3sg.Pres.Subj | |

| leyxado | uiuo. | |||||||

| left | alive | |||||||

| ‘And whoever sees or does something against this, must die for it and not be left alive.’ | ||||||||

| (Foro Real) | ||||||||

| (31) | Mais | nom | me | chal, | que | quer | que | me | |

| more | neg | me.1sg.Dat | heat | what | want.3sg.Pres | that | me.1sg.Dat | ||

| avenha | desta | batalha, | ca | ataa | aqui | ouve | |||

| come.3sg.Pres.Subj | of.this | battle | because | until | here | have.3sg.Past | |||

| ende | a | honra | e | vos | a | desonra. | |||

| of.that | the | honour | and | you | the | dishonour | |||

| ‘But it doesn’t matter whatever comes to me from that battle because until now I only had the honour and you the dishonour.’ | |||||||||

| (Demanda do Santo Graal) | |||||||||

| (32) | «Nom», | disse | el, | «mas | Deos | os | guarde | |

| No | say.3sg.Past | he | but | God | them | protect.3sg.Pres.Subj | ||

| todos, | u | quer | que | elles | sejam!» | |||

| all | where | want.3sg.Pres. | that | they | be.3pl.Pres.Subj. | |||

| ‘No, he said, but God protects them all, wherever they are!’ | ||||||||

| (Demanda do Santo Graal) | ||||||||

| (33) | E | todos | (co)munalmẽte | seyã | teodos | de | fazerlhy | |

| and | all | communally | be.3pl.Pres.Subj | have.Past.Part. | of | do.him.3sg.Dat | ||

| menagẽ | a | el | ou | a | quẽ | el | mandar | |

| homage | to | he | or | to | who | he | send.3sg.Fut.subj | |

| en | seu | logo | quando | quer | que | mãde. | ||

| in | his | place | when | want.3sg.Pres. | that | order.3sg.pres.subj | ||

| ‘And all should pay him homage, to him or to whom he sends on his behalf, whenever he orders.’ | ||||||||

| (Foro Real) | ||||||||

| (34) | […] a | [ey]greia | receba | todo | o | seu | como |

| the | church | receive.3sg.Pres.Subj | all | the | his | as | |

| quer | que | seya | achado | ||||

| want.3sg.Pres. | that | be.3pl.Pres.Subj | found. | ||||

| ‘may the church receive all that belongs to it, however it is found.’ | |||||||

| (Foro Real) | |||||||

| (35) | […] | outorga-me | que | a | minha | alma | seja |

| grant.me.1sg.dat | that | the | my | soul | be.3sg.Pres.Subj. | ||

| com | a | sua | de | pos | minha | morte | |

| with | the | your | of | after | my | death | |

| e | de | pos | a | sua | em | qual | |

| and | of | after | the | your | in | which | |

| lugar | quer | que | el | seja | |||

| place | want.3sg.Pres. | that | it | be.3sg.Pres.Subj. | |||

| ‘and grant me that my soul be with hers after our deaths, whichever place it might be.’ | |||||||

| (Demanda do Santo Graal) | |||||||

As is visible in the examples above, these ever free relatives display a universal/existential interpretation due to the maximality effect observed for free relatives (cf. Jacobson 1995).

Ever free relatives with querer were frequent in Old Portuguese and were kept in the language with all relative items (quem, onde, quando, o que), as attested by examples (36) to (40).19 The exception is the relative qual, which is ungrammatical in constructions such as (41a), which were attested in Old Portuguese. This is so because in CEP, qual cannot occur as a relative determiner taking an internal head.20 It is, however, possible to have a context such as (41b), but in this case, the relevant constituent is no longer a relative element, but the FCI qualquer.

| (36) | Quem | quer | que | use | este | vestido | ficará | ridículo |

| who | want.3sg.Pres | that | wear.3sg.Pres.Subj | this | dress | be.3sg.Fut | ridiculous | |

| ‘Whoever wears this dress will be ridiculous.’ | ||||||||

| (37) | Onde | quer | que | vás, | irei | contigo. | ||

| where | want.3sg.Pres | that | go.2sg.Pres.Subj. | go.1sg.Fut | with.you | |||

| ‘Wherever you go, I will go with you’ | ||||||||

| (38) | Esperarei | por | ti, | quando | quer | que | venhas. | |

| wait.1sg.Fut | for | you | when | want.3sg.Pres | that | come.2sg.Pres.Subj | ||

| ‘I will wait for you whenever you come.’ | ||||||||

| (39) | O | que | quer | que | digam | não | é | verdade. |

| the | what | want.3sg.Pres | that | say.3pl.Pres.Subj | neg | be.3sg.Pres | truth | |

| ‘Whatever they say, it is not truth.’ | ||||||||

| (40) | Venderei | o | carro | como | quer | que | esteja. |

| sell. 1sg.Fut | the | car | how | want.3sg.Pres | that | be.3sg.Subj | |

| ‘I will sell the car how ever it is’. | |||||||

| (41a) | *Qual | problema | quer | que | seja, | será | resolvido | ||

| what | problem | want.3sg.Pres | that | be.3sg.Pres.Subj | be.3sg.Fut | solved | |||

| ‘Whatever problem it is, it will be solved.’ | |||||||||

| (41b) | Qualquer | que | seja | o | problema, | será | resolvido |

| whatever | that | be.3sg.Pres.Subj | the | problem | be.3sg.Fut | solved | |

| ‘Whatever the problem is, it will be solved.’ | |||||||

An anonymous reviewer called attention to the possibility of ever free relatives with qual involving a referentially vague noun to have competed with other relative items. Although we find different nouns in ever free relatives, Table 3 shows that some nouns with generic interpretation appeared more often.

Table 3.

Nouns occurring between qual and quer in ever free relative.

For instance, occurrences of qual cousa quer ‘which thing want’ or qual tempo quer ‘which time want’ may be considered equivalent to o que quer ’what (you) want’ and quando quer ‘when you want’, respectively.

Although there are no grammaticalized forms involving ever free relatives headed by other relatives in Portuguese, in such contexts, the volition verb is not interpreted as a full lexical verb anymore. It seems to correspond to what Haspelmath (1995) called an indefiniteness marker since it occurs under the frozen form quer at all times and it is emptied from its original lexical meaning.21 Contrary to Portuguese, in other Romance languages, such as Spanish, we find grammaticalized forms such as cualquier, as well as also quienquier.

In fact, Romance FCIs from the WH-quer series have similarities with WH-ever FCIs in English, or with WH-immer constructions in German, showing that the emergence of FCIs from relative constructions is a much broader phenomenon. However, unlike Portuguese qualquer and its Romance cognates, English WH-ever FCIs keep their clausal status, not being able to take an NP argument (cf. Giannakidou and Cheng 2006).22

3.2.2. Ever Free Relative Clauses with Qual and Quer

In (42), we find qual introducing an ever free relative clause, in association with a form of the volition verb querer ‘want’,

| (42) | […] devo | encobrir | a | todo | meu | poder | minha |

| should | hide | to | all | my | power | my | |

| catividade, | qual | pecador | quer | que | eu | seja. | |

| captivity | which | sinner | want.3sg.Pres | that | I | be.1sg.Pres.Subj. | |

| ‘I should hide my captivity by all means, whichever sinner I may be.’ | |||||||

| (Demanda do Santo Graal) | |||||||

Ever free relative clauses with qual distinguished themselves from similar relatives headed by other elements due to the possibility of selecting a nominal additional internal head. Free relative clauses are usually considered headless relatives since they do not have a lexical antecedent.23 In an ever free relative like (42) above, qual is a relative determiner followed by a nominal internal head—the noun pecador ‘sinner’. The sequence qual pecador ‘which sinner’ can then be considered a wh-phrase, in the sense of Caponigro (2019).

Sentences such as (43) below indicate that variable verbal inflection was possible in earlier uses of the construction, confirming its clausal status.

| (43) | -Vai | per | teu | conto | a | qual | terra | quiseres […] |

| go.2sg.Imp | by | your | tale | to | which | land | want.2sg.Fut.Subj | |

| ‘-Go by your means to whatever land you want’ | ||||||||

| (Diálogos de São Gregório) | ||||||||

Despite the high frequency of ever free relative clauses in 13th century corpus, data already point to the ongoing grammaticalization of the volition verb querer into an indefiniteness marker (cf. Haspelmath 1995). In (43), the volition verb is inflected in the second person, Future Subjunctive,24 but the majority of the examples in the corpus already display the fixed form quer, which may have been ambiguous during this period between a verbal form and non-verbal marker expressing indefiniteness.

For instance, in (44), the form quer that follows the noun hora ‘hour’ can no longer be interpreted as the lexical verb. Hora ‘hour’ cannot be the subject or object of quer; in other words, there are no arguments of quer in this sentence. In (44), it seems that qual hora quer is being interpreted as a nominal constituent with a free choice reading, followed by a restrictive relative clause. The form quer functions as an indefiniteness marker, rather than a full lexical verb, not selecting a complement.25

| (44) | Mays | qual | hora | quer | que | sabhia | dalguu |

| but | which | hour | want.3sg.Pres | that | know.3sg:Pres.Subj | of.some | |

| erege | logo | o | faça | a | saber | ao | |

| heretic | soon | it.acc | do.3sg.Pres.Subj | to | know | to.the | |

| bispo | da | terra | |||||

| bishop | of.the | land | |||||

| ‘but at whatever time you learn of a heretic, tell it to the bishop of that land right away.’ | |||||||

| (Foro Real) | |||||||

This takes us to another particular feature of ever free relative clauses with qual and the volition verb—the frequent presence of que clauses after the verb, as in (45):

| (45) | «qual | vilani(a) | quer | que | eu | faza | i |

| which | villainy | want.3sg.Pres | that | I | do.1sg.Pres.Subj | there | |

| contra | vos, | a | justar | vos | convem | ou | |

| against | you.2pl-acc | to | fight | you.2pl-dat | suit.3sg.Pres. | or | |

| queirades | ou | nom.» | |||||

| want.2pl.Pres.Subj | or | neg | |||||

| ‘Whatever villainy I do against you, you should fight it, whether you want it or not.’ | |||||||

| (Demanda do Santo Graal) | |||||||

The nature of these que clauses is not consensual due to the initial ambiguity between a complement clause of the volition verb and a restrictive relative clause introduced by a relative pronoun. In early examples, the exact nature of the element quer (still a verb or already an indefiniteness marker) may not be straightforward.

Based on Old Spanish data, both Rivero (1988) and Company Company (2009) consider these que clauses to be dominantly restrictive relative clauses already in the medieval period. However, a different analysis is suggested by Mackenzie (2019), with the interpretation of que clauses still as complement clauses selected by the volition verb. Mackenzie (2019, p. 195) considers that contexts with a que clause represent «a violation of Chomsky and Lasnik’s (1977) ‘doubly-filled Comp’ filter, a constraint requiring the complementizer to be silent if an overt wh-word is also present in the same area of clause structure». I will comment on this later.

Even though que clauses have allegedly started as complement clauses of the volition verb, data from our corpus fails to attest this construction, since sentences displaying the volition verb with different inflection from the ambiguous third person singular Present tense quer do not occur with a que clause.

Additionally, the large majority, if not all, of the examples with a que clause seem to favour its interpretation as a restrictive relative. This aligns with the idea that the verbal form quer was losing its lexical properties and becoming an indefiniteness marker. Sentences such as (46) below rule out the complement clause interpretation.

| (46) | Porque | os | comendadores | de | qual | ordĩ | quer |

| because | the | commanders | of | which | order | want.3sg.Pres | |

| que | sõ | postos | enas | baylias | nõ | poden | |

| that | be.3pl.Pres.Ind | put | in.the | bailia26 | neg | can.3pl.Pres | |

| auer | seus | mayores | pera | demandar | seus | dereytos | |

| have | their | superiors | to | demand | their | rights | |

| sobellas | cousas | que | perteeçen | as | baylias | ||

| over.the | things | that | belong | to.the | bailias | ||

| ‘Because the commanders of whatever order who are assigned for the bailias cannot have their superiors to demand their rights over things belonging to the bailias.’ | |||||||

| (Foro Real) | |||||||

In (46), the que clause is a restrictive relative clause modifying the noun comendadores ‘commanders’ (i.e., it restricts the set of commanders to the subset of those who are assigned to the bailias). In this particular context, the form quer is no longer interpreted as the volition verb, therefore not selecting a complement anymore. Furthermore, if the que clause was a complement clause of querer, we would expect the main verb to be in the subjunctive mood, as in sentence (45) above. However, ‘sõ postos’ displays an indicative mood.

It seems that in the 13th century, ever free relative clauses were no longer unambiguously clausal instances since in most, if not all, of the examples, the volition verb is not fully behaving as a lexical verb anymore. The grammaticalization of the volition verb into an indefiniteness marker could have been the trigger for the reanalysis of ever free relative clauses such as the FCI qualquer. However, this proposal faces some challenges as far as Portuguese data are concerned.

In their analysis of Old Spanish data, Company Company and Pozas Loyo (2009) propose a three-step grammaticalization path for FCI cualquier. The authors consider that the first stage consisted of an ever free relative clause with an additional internal head, like the one presented in (46) for Portuguese. In a second stage, the free relative would occupy a prenominal position, but with the nominal element remaining in situ (as in cual quiera castigo ‘which want.3sg.Pres.Subj punishment’), until it was reanalyzed as a non-clausal element, therefore reaching the third stage.

Also referring to Old Spanish, we find the proposal by Mackenzie (2019), who gives as an example of an ever free relative clause with qual and a form of the volition verb, the context presented in (47).

| (47) | que por [CP de quales quier malas costumbres que ell omne sea]. |

| ‘… that whatever bad habits a man might be prone to […]’ | |

| (Mackenzie 2019, p. 194, General estoria I, fol. 272v) |

At this point, I would like to address the problem of the violation of the ‘doubly-filled Comp’ filter introduced by Mackenzie (2019) that has been referred to earlier in this section. The context presented below in (47) is given by Mackenzie (2019) as an example of the violation of the ‘doubly-filled Comp’ filter involving ever free relatives with qual and a volition verb in Old Spanish. I consider that there is no violation of the ‘doubly-filled Comp’ filter here since quales quier does not correspond to an ever free relative but to a specifier of the noun, as we will see later on.

The example in (47) raises, however, a crucial question relative to the emergence of an independent item qualquer. Is it possible that ever free relative clauses with qual and quer taking an additional nominal head gave place to both prenominal and postnominal qualquer? This has been the evolution initially proposed by Cuervo (1893) and which has been followed by some authors (cf. Company Company and Pozas Loyo 2009) but rejected by others (cf. Elvira 2020) for Old Spanish.

Let us assume that the starting point of qualquer in (47) was an ever free relative clause like (46), with qual selecting an additional internal head. This configuration would determine that two relevant elements—qual and quer—would have first been separated by a nominal item, as in qual maneyra quer ‘which manner wants’. The presence of the nominal element between the relative determiner and the verbal form/indefiniteness marker would block the adjacency required for reanalysis. The nominal element could not be interpreted as the additional internal head anymore since it would occur after the verbal form, and therefore already under inflection phrase (IP), as the hypothetical representation in (48) illustrates.

| (48) | [DP [CP [C qual[IP quer [NP maneyra]]]] |

Following Company Company and Pozas Loyo (2009), Kellert (2021, p. 17) considers that a configuration such as (48) corresponds to a relative clause with the NP in situ, which would be the second stage of grammaticalization of Spanish cualquier(a) and Italian qualunque. Although such a hypothesis should not be ruled out for Portuguese, I found no empirical evidence in the data to sustain such a stage.27 Even though split DPs are registered in Old Portuguese (cf. Martins 2004), this configuration seems to apply mainly to modifiers and not to the splitting of the relative determiner and the additional internal head (cf. Cardoso 2011), as would be the case for (48). Furthermore, for the same chronological period, I did not find cases of NP in situ with the only other relative determiner taking an additional internal head: the relative quanto(s) ‘how.many/much’. Finally, ever free relative clauses with the NP in situ seem incompatible with the cases where qualquer combines with the indefinite element outro ‘other’ to its left as in outro qualquer N.28 We look at these examples further on.

Germanic constructions with WH-immer seem to parallel ever free relatives with qual, due to the presence of an additional internal head, despite the non-verbal origin of immer ‘ever’. According to Bossuyt and Leuschner (2020, p. 207), WH-immer constructions in German are still not grammaticalized due to the impossibility of splitting the complex WH formed by the relative welcher ‘which’ and the nominal element (welches *immer Buch ‘whichever book’), similar to what we saw in ever free relatives with qual.

So far, we have argued that a merge of qual and quer seems unlikely due to the presence of an additional internal head. However, it is also relevant that ever free relative clauses with qual and quer ceased to be available after the 14th century. Elvira (2020) claims that the relative qual disappears from Old Spanish and that is the reason why ever free relatives with qual cease to occur. The same explanation fits the Portuguese case. As we have seen previously, ever free relative clauses existed in Old Portuguese introduced by different relative items. They all continue to occur in CEP, except for the ones introduced by qual. As such, it is not the case that the paradigm of ever free relatives disappeared or changed, but only that qual stopped being available. In fact, all instances of bare qual as a relative element have disappeared from the language. Only the relative pronoun o-qual is kept, but contrary to what was verified in Old Portuguese, it stops occurring with an additional internal head (cf. Cardoso 2008, 2011)29.

In the next subsection, we look at appositive relative clauses, which were another clausal context of occurrence of qual and quer. Appositive relative clauses seem more likely to have favoured the reanalysis of the two elements.

3.2.3. Appositive Relative Clauses with Qual and Quer

Apart from ever free relative clauses, the relative determiner qual also combines with a form of the volition verb querer in appositive relative clauses as the one illustrated in (49):

| (49) | Custume | h(e) | do | peõ | q(ue) | uẽde | o | |

| Custom | be.3sg.Pres | of.the | peasant | that | sell.3sg.Pres | the | ||

| vio | da | jugada | q(ue) | deue | a | el | ||

| wine | of.the | tax | that | owe.3sg.Pres | to | the | ||

| Rey | a | dar | q(ue) | en | pod(er) | seía | ||

| king | to | give | that | in | power | be.3sg.Pres.Subj | ||

| do | íugadeyro | de | demãdar | o | vinho | ou | ||

| of.the | land.owner | to | demand | the | wine | or | ||

| os | dín(hei)r(o)s | qual | quís(er). | |||||

| the | money | which | want.3sg.Fut.Subj | |||||

| ‘If the peasant sells the wine with which he would pay his tax to the king, may the land owner have the right to demand the wine or the money, whichever he wants.’ | ||||||||

| (Dos Costumes de Santarém) | ||||||||

It is quite clear that in (49), we are in the presence of a clause since we still find the volition verb inflected—in this case, in the future subjunctive. Furthermore, despite the presence of a coordinated DP with the last DP in the chain being plural, there is no number agreement between the DP and qual, which points to a parenthetical status of the clause. In this particular example, the sequence qual quís(er) corresponds to an appositive relative clause (or a parenthetical clause), which I argue to be a relevant context for the emergence of postnominal qualquer.

We find in the corpus only five examples where the verb did not correspond to the form quer but displayed different tense/mood (subjunctive mood, either future or imperfect tenses) and person/number inflection, as in (23), repeated below as (50).

| (50) | […] mais | escolhi | tu | huma | morte | qual | quiseres […] |

| but | choose.2sg.Imp | you | a | death | which | want.2sg.Fut.Subj | |

| ‘but choose a death, whatever you want.’ | |||||||

| (Diálogos de São Gregório) | |||||||

Examples (49) and (50) correspond to additional information on the nominal item on the left and they usually constitute a comment on the existing freedom to choose any element from a list presented before.

Appositive relative clauses could also display discontinuity between the relative determiner qual and the volition verb querer, as in (51) and (52), but differently from ever free relatives, the element in between does not correspond to an additional internal head selected by the determiner. Both in (51) and (52), it is the subject of the clause, which could be lexically empty. As expected, appositive clauses always associate with a nominal element, which they modify.

| (51) | e | que | eu | mande | lavrar | moeda | qual | eu | quiser. |

| and | that | I | order.1sg.Pres.Subj | mint | coin | which | I | want.1sg.Fut.Subj | |

| ‘and that I order to mint coin, whatever I want.’ | |||||||||

| (Crónica Geral de Espanha) | |||||||||

| (52) | E, | cõ | cada | huu, | devẽ | dar | ao |

| and | with | each | one | should.3pl.Pres | give | to.the | |

| retador | cavallo | e | armas | e | de | comer | |

| challenger | horse | and | weapons | and | of | eat | |

| e | de | bever | vinho | ou | auga | qual | |

| and | of | drink | wine | or | water | which | |

| elle | quisesse. | ||||||

| he | want.3sg.Fut.Subj | ||||||

| ‘And with each other, you should give the challenger horse and weapons and food and drink, wine or water, whichever he wants.’ | |||||||

| (Crónica Geral de Espanha) | |||||||

For example, in (52), the relative appositive clause introduces a comment regarding the set of possible drinking choices presented before, reinforcing the freedom of choice.

Occurrences of qualquer as a postnominal modifier of the noun may have originated in appositive relative constructions as the ones presented in (50), with a null subject.

At this point, we hypothesize that instances of qualquer in postnominal position may have first originated in appositive relative clauses, instead of ever free relatives. Contrary to what we saw for ever free relatives, there is no additional internal head, leaving space for the reanalysis of the two elements as a non-clausal adjectival modifier of the noun.

Although the scarcity of examples does not allow one to present solid arguments for this hypothesis, the comparison with other Romance FCIs may add some strength to the discussion. The Italian FCI qualsiasi contains the pronoun si in postverbal position. However, according to (Kellert 2021, p. 17), it originated in the relative clause qual si sia, with the pronoun si between the relative determiner and the verb.30 Degano and Aloni (2021) also argue in the same direction, stating that the forms qualsiasi and qualsivoglia occurred in medieval Italian as relative clauses, before being reanalyzed as independent items. The presence of the pronoun between qual and the verb in the first stage shows that, at least for Italian, the origin of the two FCIs could not have been an ever free relative clause with an additional internal head since the reflexive pronoun does not correspond to the nominal internal head.

Examples with a pronoun appearing between qual and quer, as exemplified in (53), are rare in Portuguese data, showing that this was not a productive construction.

| (53) | Mais | en | grave | dia | naci,| | se | Deus | |

| but | in | unhappy | day | be.born.1sg.Past | if | God | ||

| conselho | non | m’ | i | der’; | | ca | |||

| advice | neg | me.1sg.acc | here | give | because | |||

| d’estas | coitas | qual-xe-quer| | m’ | ca | ||||

| of.these | pains | which.se.Expl.want.3sg.Pres | me.1sg.acc | because | ||||

| é | min | mui | grave | d’endurar | min | |||

| be.3sg.Pres | me.1sg.dat | very | hard | of.endure | me.1sg.dat | |||

| ‘But I was born in an unhappy day if God does not give me here advice, because of these pains, no matter which, are very hard for me to endure.’ | ||||||||

| (Galician-Portuguese poetry, TMILG) | ||||||||

The pronoun xe (se) is usually associated with an expletive use or is interpreted as an ethic dative (Huber 1933, p. 176). It does not correspond to an additional internal head of the relative clause but seems to correspond to an expletive item. What is interesting here is the fact that, contrary to Portuguese, other Romance languages present grammaticalized FCIs that contain the expletive pronoun, as is the case of Old Italian.

Example (53) is the only occurrence found in the sample corpus, though. Due to the scarcity of examples, we may assume that this was not a frequent construction in Old Portuguese and, therefore, it seems logical that the grammaticalized form of the FCI does not preserve the pronoun in its interior. This does not invalidate the emergence of postnominal qualquer from appositive relative clauses, similar to what is argued for Italian by Degano and Aloni (2021).

In any case, unambiguous occurrences of qual quer as an appositive relative clause are not frequent in the corpus. Most cases of qualquer in the postnominal position can already be interpreted as non-clausal, resulting from the merge between the relative determiner qual and quer, which was already an indefiniteness marker. However, assuming that postnominal qualquer originates from reanalysis of appositive relative clauses poses a problem to prenominal occurrences of qualquer. We could consider that, after lexicalizing as an independent item, postnominal qualquer starts to occur in prenominal position. Under this hypothesis, we would expect to find a higher frequency of postnominal qualquer in the 13th century, but what we find is prenominal occurrences as the most widespread pattern. In the next section, I investigate prenominal and postnominal occurrences of lexicalized qualquer and I argue in favour of the existence of two different items: a prenominal qualquer that was a quantifier-like item and postnominal qualquer, functioning as an adjectival-like modifier.

3.3. Prenominal and Postnominal Instances of Qualquer

In this section, I look at prenominal and postnominal occurrences of qualquer as a lexicalized item. I argue that prenominal qualquer was already a quantifier-like element in 13th century texts, while postnominal qualquer behaved as an adjectival element, resulting from the reanalysis of appositive relative clauses, as we have seen before.

Examples (54) and (55) show the most common patterns of occurrence of qualquer in prenominal position31, where it is the only specifier for the nominal element.

| (54) | E | ella | disse | que | ante | queria | morrer | de | |

| and | she | say.3sg.Past | that | before | want.3sg.Imperf | die | of | ||

| qual | quer | morte | ante | que | seer | christãa. | |||

| which | ever | death | before | than | be | Christian | |||

| ‘And she said that she would rather die of any death rather than being a Christian.’ | |||||||||

| (Demanda do Santo Graal) | |||||||||

| (55) | […] e | rogamos | a | qualquer | Tabellion | que | esta |

| and | ask.1pl.Pres | to | whichever | notary | that | this | |

| carta | uj’r | que | faça | ende | a | carta | |

| letter | see.3sg.Fut.Subj | that | do.3sg.Pres.Subj | of.this | the | letter | |

| da | dita | partiçõ | |||||

| of.the | said | partition | |||||

| ‘and we ask any notary who sees this letter that he makes the letter of the aforementioned partition.’ | |||||||

| (DPRNL) | |||||||

Prenominal qualquer also occurs more than half of the times with a que clause, but the que clause in question is always a restrictive relative clause that modifies the DP in which qualquer occurs, as in (56).

| (56) | Mas, | per | qual | quer | maneyra | que | elle | morresse, | ||

| but | by | which | ever | manner | that | he | die.3sg.Imperf.Subj | |||

| ouve | o | poboo | delle | grande | perda. | |||||

| have.3sg.Past | the | people | of.he | great | loss | |||||

| ‘But, by whatever manner he died, the people suffered a great loss.’ | ||||||||||

| (Crónica Geral de Espanha) | ||||||||||

The examples above seem to indicate that 13th century prenominal instances of qualquer were independent of any possible clausal origin.

Prenominal qualquer seems to behave as other quantifier-like elements, as I try to demonstrate in the next paragraphs.

While in prenominal position, qualquer usually precedes a noun, as in (57), or a prepositional phrase, as in (58).

| (57) | E | ella | disse | que | ante | queria | morrer | de | ||

| and | she | say.3sg.Past | that | before | want.3sg.Imperf | die | of | |||

| qual | quer | morte | ante | que | seer | christãa. | ||||

| which | ever | death | before | than | be | Christian | ||||

| ‘And she said that she would rather die of any death rather than being a Christian.’ | ||||||||||

| (Demanda do Santo Graal) | ||||||||||

| (58) | E | qualquer | de | vos, | meus | filhos, | que |

| and | whichever | of | you | my | sons | that | |

| as | herdar, | delhe | Deus | a | minha | beençõ. | |

| them.3pl.acc | inherit | give.3sg.pres.Subj.him.3sg.dat | God | the | my | blessing | |

| ‘And whichever of you, my sons, inherits them, may God give you my blessing.’ | |||||||

| (Crónica Geral de Espanha) | |||||||

Both configurations are compatible with its classification as a quantifier. According to Cardinaletti and Giusti (1992, 2006), quantifiers should be seen as an independent projection—quantifier phrase (QP)—above DP. Quantifiers select DP as their complement, but the nominal element may be lexically null. The structure in (59) represents the internal architecture of QP:

| (59) | [QP [Q qualquer] [DP [PP [NP [N maneyra]]]]] |

Assuming the structure in (59), we can assume that prenominal qualquer is the head of the QP and it takes a nominal complement as in the case of example (57). However, the nominal element may be null, and we can find qualquer taking a partitive PP, as is the case of (58) above. In such contexts, qualquer is a quantifier-like element, taking scope over the noun (or pronoun) contained in the PP. This is the type of configuration where other quantifiers/indefinites, such as nenhum ‘none’ and algum ‘some’ also appear in Old Portuguese texts. Examples (60) and (61) show these items in a similar configuration, where they select a lexically empty noun and quantify over the noun/pronoun contained in the PP.

| (60) | -Como | daria | nenhum | de | nos | outros | semelhante | voz, |

| how | give.3sg.Cond | no one | of | us.1pl.dat | others | similar | voice | |

| se | nos | nom | sabiamos | parte | da | outra | çillada? | |

| if | we | neg | know.1pl.Imperf | part | of.the | other | trap | |

| ‘- How would any of us give similar voice if we did not know part of the trap?’ | ||||||||

| (CDPM) | ||||||||

| (61) | Quando | elle | esto | ouvio, | deteve | seu | golpe, | ca | ||||

| when | he | this | hear.3sg.Past | hold.3sg.Past | his | coup | because | |||||

| ouve | gram | pavor | de | seer | algũu | de | seus | irmãos. | ||||

| have.3sg.Past | great | fear | of | be | some | of | his | brothers | ||||

| ‘When he heard this, he held his coup, because he was afraid it was one of his brothers.’ | ||||||||||||

| (Demanda do Santro Graal) | ||||||||||||

Apart from these two configurations, quantifiers can also assume a bare form, as argued by Cardinaletti and Giusti (2006). The authors considered the existence of two types of bare quantifiers: one that takes a covert DP complement and another that they call ‘intransitive’ quantifier and that never takes any complement, resembling (personal) pronouns. Examples such as (62) and (63) seem to correspond to a bare quantifier configuration.32

| (62) | E | por | esto | maldicto | he | qualquer | que |

| and | by | this | cursed | be.3sg.Pres | anyone | that | |

| treiçom | faz, | ||||||

| betrayal | do.3sg.Pres | ||||||

| ‘And for this reason anyone, who commits betrayal is cursed’. | |||||||

| (Crónica Geral de Espanha) | |||||||

| (63) | […] e | começou | de | ferir | dhua | e | da |

| and | start.3sg.Past | of | hurt | of.one | and | of.the | |

| outra | parte, | de | tal | guisa | que | qualquer | |

| other | part | in | such | manner | that | anyone | |

| a | que | elle | dava | hua | paancada | nõ | |

| to | who | he | give.3sg.Imperf | one | hit | neg | |

| avia | mester | mais | ferida. | ||||

| have.3sg.Imperf | need | more | wound | ||||

| ‘and he started to attack in all directions in such a way that anyone whom he hit would be knocked out’ | |||||||

| (Crónica Geral de Espanha) | |||||||

Notice that in (62) and (63), qualquer functions as a pronominal element, referring to a human entity. It seems to be equivalent to other indefinites, such as algum ‘someone’ or nenhum ‘nobody’ with a [+human] feature. Interestingly, during earlier stages of Portuguese, the indefinites algum ‘someone’ and nenhum ‘no one’ could also occur as full pronouns with a [+human] feature. This possibility was lost until the end of the 16th century. Although I cannot indicate the exact period in which qualquer stops occurring as a bare quantifier, the loss of the [+human] feature can likely be paired with the same event affecting algum and nenhum.33 Galician calquera and Spanish cualquiera have kept that possibility though (cf. Álvarez and Xove 2002, p. 5005; Company Company and Pozas Loyo 2009).

Occurrences of qualquer as a bare quantifier are, however, always followed by a que clause, which is unambiguously a restrictive relative clause. The presence of the preposition a ‘to’ between qualquer and the element que in (63) indicates that it is a relative clause due to preposition pied-piping (the preposition introduces the dative selected by the verbal form dava ‘give.3sg.Imperf’). In these cases, the relative clause seems to set the domain of restriction of the quantifier since qualquer appears in a bare configuration.

The examples presented so far seem to point to the existence of a quantifier-like element qualquer, which could be paired with other quantifiers/indefinites available in Old Portuguese and which seems to be independent from the clausal instances we have seen before.

Although quantifier qualquer occurs mostly as the only specifier of the nominal element, there are a few examples that require some clarification. I refer to the cases where prenominal qualquer coocurs with the indefinite outro ‘other’ before the noun (cf. Brugè 2018; Brugè and Giusti 2021). There is a total of nine occurrences of prenominal qualquer with outro ‘other’ in the corpus (it represents 20% of all prenominal entries). In two examples, qualquer precedes outro ‘other’, while in the remaining entries, qualquer appears after outro ‘other’, as illustrated in (64) and (65), respectively.

| (64) | […] e | carta | ou | cartas | ende | fazer | pelos | tabellioes | de | Lixbõa |

| and | letter | or | letters | of.this | do | by.the | notaries | of | Lisbon | |

| ou | de | qualquer | outro | logar | ||||||

| or | of | whichever | other | place | ||||||

| ‘and make letter or letters of this through the notaries of Lisbon or any other place’ | ||||||||||

| (DPRNP) | ||||||||||

| (65) | […] ou | desse | alguu | aver | por | alguu | beneficio | |

| or | give.3sg.Imperf.Subj | some | good | by | some | benefit | ||

| da | Sancta | Igreja | ao | rey | ou | ao | ||

| of.the | Saint | Church | to.the | king | or | to.the | ||

| prellado | ou | a | outro | qualquer | padroeiro, | asi | ||

| prelate | or | to | other | whichever | patron | like.this | ||

| eclesiastico | como | sagral | ||||||

| ecclesiastic | as | sacred | ||||||

| ‘or give any good by any benefit from the Holy Church to the king or the prelate or any other patron as ecclesiastic as sacred.’ | ||||||||

| (Crónica Geral de Espanha) | ||||||||

The combination with outro is usually found as a way to introduce the last nominal item of a coordination displaying two or more nouns in alternative. Although the sequence in (64) does not pose problems to a quantifier-like interpretation, sentences such as (65) seem incompatible with qualquer being the head of QP because we have outro, an adjectival element, preceding the quantifier. This may be a reflex of the different nature of qualquer in sentences (64) and (65)34. I return to this point in Section 4.

Let us now look at occurrences of lexicalized qualquer in the postnominal position.

While in the postnominal position, qualquer is almost always part of an indefinite DP. The most frequent pattern (it represents 66% of the occurrences) is the one containing the indefinite outro ‘other’ in the prenominal position, as illustrated in (66). Other elements such as um ‘a’ or algum ‘some’ can also be found, as in examples (67) and (68), respectively, but they are infrequent. There are only three occurrences of um ‘a’ and one of algum ‘some’.

| (66) | E | se | iustiça | fezer, | aya | a | pẽa |

| and | if | justice | do.3sg.Fut.Subj | have.3sg.Pres.Subj | the | penalty | |

| que | auerya | outro | ome | qual | quer | que | |

| that | have.3sg.Cond | other | man | whichever | that | ||

| tal | feyto | fezesse. | |||||

| such | deed | do.3sg.Imperf.Subj | |||||

| ‘And if justice is made, may he have the same penalty any other man would for such a deed.’ | |||||||

| (Foro Real) | |||||||

| (67) | […] nõ | lhe | daram | mayor | corrigimento | q(ue) |

| neg | him.3sg.dat | give.3pl.Fut | bigger | correction | than | |

| dua | pínquada | que | lhe | dem | nos | |

| of.one | stroke | that | him.3sg.dat | give.3pl.Pres | in.the | |

| narizes | de | que | saya | sangue | ou | |

| noses | of | that | go.out.3sg.Pres.Subj | blood | or | |

| dua | chaga | símplx | qual | q(ue)r | ||

| of.one | wound | simple | whichever | |||

| ‘they will not give him any correction other than a stroke in the nose, from where blood runs or from any simple wound.’ | ||||||

| (Dos Costumes de Santarém) | ||||||

| (68) | E | vós | mentes | non | metedes,| | se | ela | filho |

| and | you | minds | neg | put.2pl.Pres | if | she | son | |

| fezer,| | andando, | como | veedes,| | con | algun | peon | qual | |

| make | walking | as | see.2pl.Pres | with | some | peasant | which | |

| quer | ||||||||

| ever | ||||||||

| ‘And can you not notice that she may get pregnant, going out, as you see, with some ordinary peasant.’ | ||||||||

| (Galician-Portuguese poetry) | ||||||||

Postnominal qualquer also occurs with modification using a restrictive relative clause with the subjunctive mood in 23% of the contexts. The relative clause frequently displays the copula ser ‘be’, as in (69).

| (69) | Os | scriuaans | publicos | tenhã | as | notas | primeyras |

| the | scribes | public | have.3pl.Pres.Subj | the | notes | first | |

| de | todalhas | cartas | que | fezerẽ, | assy | ||

| of | all.the | letters | that | make.3pl.Fut.Subj | this.way | ||

| as | dos | juyzos | coma | das | uendas | ||

| the | of.the | judgments | as | of.the | sales | ||

| come | doutro | preyto | qual | quer | que | seya | |

| as | of.other | contract | whichever | that | be.3sg.Pres.Subj | ||

| ‘The public scribes must have the first notes of all letters they do, the ones from the judgments, as well as the ones from the sales or from other contract, whatever may be.’ | |||||||

| (Foro Real) | |||||||

Apart from the examples above, postnominal qualquer is also registered in what we can call a bare noun configuration, without the presence of any prenominal element, as illustrated in (70). This pattern corresponds to approximately 17% of the occurrences of postnominal qualquer.

| (70) | Se | alguu | ome | fezer | demanda | a | outro | ||||

| if | some | man | do.3sg.Fut.Subj | demand | to | other | |||||

| sobre | casa | ou | uinha | ou | herdade | qualquer, | |||||

| over | house | or | vineyard | or | property | whichever | |||||

| ((demande)) | an(te) | aquel | alcayde | u | é | morador | |||||

| demand.3sg.Pres.Subj | before | that | mayor | where | be.3sg.Pres | resident | |||||

| aquel | a | quẽ | demandẽ | ||||||||

| that | to | whom | demand.3pl.Pres.Subj | ||||||||

| ‘If any man makes a demand to other over a house or vineyard or any property, ask before the mayor where lives the man to whom demands are made.’ | |||||||||||

| (Foro Real) | |||||||||||

Sentences such as the one above are ruled out in contemporary Portuguese due to the fact that CEP does not allow singular bare nouns, except in very specific contexts. Singular bare nouns (and bare nouns in general) have been pointed out as occurring more freely in earlier stages of the language, which can explain examples such as (70). The combination with bare nouns is also registered for Old Italian qualunque, with this pattern being more frequent than the one including an indefinite determiner (cf. Kellert 2021). In any case, bare nouns are usually associated with an indefinite or generic interpretation.

4. On the Emergence of Two Qualquer: General Discussion

Up to this point, I have argued that postnominal instances of qualquer most likely originated in appositive relative clauses. I have therefore rejected the assumption that they resulted from ever free relative clauses with the nominal additional internal head in situ.

On the other hand, I have claimed that postnominal qualquer seems to behave as an adjective-like modifier of the noun, while prenominal qualquer is close to a quantifier-like item. However, it is yet to be explained how prenominal qualquer emerged.

I follow the insights by Rivero (1984, 1988) for Old Spanish. The author suggests that the relative qual had “a double lexical classification” in medieval Spanish, still occurring in ever free relative clauses with the volition verb, but also occurring as part of the word qualquer, a member of the quantifiers’ paradigm. To ever free relatives, I also add the intervention of relative qual and the volition verb in appositive relative clauses.

Nevertheless, the ambiguity of relative qual is not enough to explain the emergence of prenominal qualquer. Data from medieval Italian qualsisia show us a context of use that we did not find in Portuguese data, namely the occurrence of a relative clause in prenominal position, as illustrated in (71) and (72), to which Degano and Aloni (2021) associate different interpretations: a no matter (71) and an FC indefinite interpretation (72).

| (71) | Qual | si | sia | la | cagione, | oggi | poche | o | non |

| what | clitic | is.Subj | the | reason | today | few | or | not | |

| niuna | donna | rimasa | ci | è | la | qual… | |||

| no-one | women | left | to-us | is | the | who | |||

| ‘Whatever the cause is, today few or no women felt is such that … | |||||||||

| (Boccaccio, Decameron VI: 1–10, 1353; apud Degano and Aloni 2021, p. 464) | |||||||||

| (72) | i | quali | sì | timorosamente | mostrano | di | dare | le | openioni | sopra |

| the | who | so | timidly | show | to | say | the | opinions | on | |

| qual | si | sia | proposta. | |||||||

| What | clitic | is:subj | proposal | |||||||

| ‘who so timidly show that they say their opinions on any proposal’ | ||||||||||

| (Della Casa, Galateo ovvero de’ costume, 1558; apud Degano and Aloni 2021, p. 464) | ||||||||||

I hypothesize that Old Portuguese may have had similar structures, involving the volition verb querer, and those may have been reanalyzed as independent prenominal qualquer. In Foros de Castelo Rodrigo, a collection of local laws written in the first half of the 13th century, Cintra (1984) accounts for the occurrence of a construction with the form qual que quer eglesia ‘what that want church’, with the relative clause preceding the nominal element. In any case, if this type of relative is at the core of prenominal qualquer, reanalysis must have occurred very early in the language, prior to the reanalysis of postnominal qualquer.

Finally, one last question that needs to be addressed is related to differences in meaning associated with the prenominal or postnominal position of qualquer. Even though prenominal and postnominal qualquer seem to originate in a relative clause, the clauses were different, and the chronology of the reanalysis was also different. This may have had some implications for the meanings associated with qualquer, depending on its position in relation to the noun. In CEP, when occurring in the postnominal position, qualquer never displays a universal reading, while in the prenominal position, it is usually interpreted as a universal quantifier, but it can also be associated with an existential interpretation.

I start by recalling that prenominal qualquer was paired with quantifiers, while postnominal qualquer was associated with an adjectival-like nature. However, examples such as (73) were considered problematic for a quantifier-like status due to the presence of the indefinite outro to the left of the quantifier.

| (73) | E | guareceu | daquella | gordura | tam | bem | que | |