Abstract

This paper explores the evolution of the conversational formula pues eso in Peninsular Spanish through the framework of constructionalization, so as to describe how form–meaning pairings have been consolidated. Additionally, the Val.Es.Co. model for discourse segmentation is introduced as part of the form pole in the construction. The findings suggest that PE has become a consolidated parenthetical, procedural device during the 20th century, but that previous centuries are also key in understanding how the new functions were developed from pues.

1. Introduction

The Peninsular Spanish conversational formula pues eso (henceforth, PE) covers five different functions: formulation (1), self-affirmation (2), back-to-topic (3), agreement (4), and closing mark (5) (Salameh Jiménez 2020b). Observe examples (1)–(5) (see Section 3 for a more detailed explanation of each function of PE):

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

These five functions, in turn, are associated with various prosodic, structural, and contextual features that work together, reflecting a completed process of constructionalization (Traugott and Trousdale 2013) which remains unexplored. This paper aims to trace the diachronic evolution of PE as a construction by analyzing linguistic patterns related to pre- and post-constructional processes, including syntactic (e.g., structural integration, variation in the placement of PE), semantic (e.g., shifts in meaning, bleaching, combination with new words), and pragmatic features (e.g., acquisition of new invited inferences in new contexts). In addition, our proposal incorporates units and positions from the Val.Es.Co. model of discourse segmentation (henceforth, VAM).

The analysis seeks to achieve several research objectives, such as (i) detecting how pues and eso were combined in different contexts, (ii) under which conditions their fixation was possible, and (iii) determining whether PE results from a recent language change consolidated in the 20th century. Data were retrieved from the CDH corpus (Corpus del Diccionario histórico de la lengua Española, Real Academia Española) (CDH n.d.), with particular attention to written texts reproducing orality, in accordance with the concept of “imitation of orality” (López Serena 2023).

The results suggest a shift in PE towards a free, non-integrated sentence structure that preserves anaphoric–cataphoric values in novel interactive contexts. Agreement marks and self-reinforcement functions have been documented in texts published in the late 19th and 20th centuries by authors such as Pérez-Galdós, Aub, Sánchez Ferlosio, etc. Formulation and back-to-topic have also been consolidated during the 20th century, with some closing mark examples found as late as the 1990s. However, examining examples from previous centuries, specifically the 16th and 17th centuries, is crucial for observing the development of these functions through changes in morphological, structural, and pragmatic features. The VAM contributes to a better delineation of such functional development, allowing for the systematic categorization of the construction by considering combinations of functions, units, and positions. This approach aligns with previous works (Estellés Arguedas and Pons Bordería 2014; Salameh Jiménez 2020a).

From a broader perspective, the results encourage further research on the constructionalization of similar interactive formulas in Peninsular Spanish, such as pues nada, pues bueno, or pues bien (Salameh Jiménez, Forthcoming(a)), as well as other general extenders, such as y nada, y eso, no sé qué, etc. (López Serena 2018; Llopis-Cardona 2020; see also Borreguero Zuloaga 2023, for the diachronic study of general extenders in Spanish). The existence of these constructions sharing similar properties in other Romance languages such as French, Portuguese, or Italian also suggests potential relationships at a higher, abstract level of a constructional network, which should be explored diachronically (Gras 2011).

The contents of this paper are distributed across the following sections: Section 2 draws upon the frameworks of grammaticalization and construction grammar (Section 2.1) and summarizes the basic units of the VAM, illustrating how they can be integrated into a constructional approach (Section 2.2). Section 3 briefly describes how PE functions in Peninsular Spanish. Section 4 is subdivided into two subsections: Section 4.1 details the methodology, addressing how the data have been handled and specifying the main linguistic parameters employed in the analysis; Section 4.2 presents the results through three sections dealing with the different stages of evolution detected in PE. Finally, Section 5 discusses the theoretical background regarding the results obtained, highlighting areas for future research.

2. Theoretical Backgrounds

2.1. Beyond Grammaticalization: Construction Grammar and Constructionalization Processes

Research in grammaticalization has been the focus of several works across languages during the 20th century (see some foundational studies, such as Givón 1971; Hopper 1991; Sweetser 1988; Traugott 1982, 1995; Traugott and Heine 1991, among others). These works describe how linguistic items develop grammatical functions in specific contexts (Hopper and Traugott 2003, p. 2), with special interest in the cognitive and functional mechanisms under the changes carried out throughout different time spans (Traugott and Dasher 2002, p. 6). Some basic features commonly assumed in grammaticalization studies are: (i) changes are unidirectional, which means that they are not usually reversible (Haspelmath 1999; Hopper and Traugott 2003, p. 99); (ii) there are generalization processes involving modifications in class words and uses in new contexts (Hopper 1991, p. 22; Arguedas 2011, p. 30); and (iii) meaning bleaching tends to be produced, which can differ depending on the linguistic item addressed (e.g., the development of verbal items, Garachana and Sansiseña 2023; the constitution of prepositional systems, Fagard and Mardale 2015; or the rise of discourse markers, Salameh Jiménez 2020b; Deng 2023; general extenders, Brinton 2023).

More recently, the field has been opened towards construction grammar (CxG): it describes language as a system based on form–meaning pairings (Fillmore 1988, p. 36), incorporating prosodic, morphosyntactic, and semantic features underlying their basis (Boas 2010, p. 2). Constructions are interconnected within conventional networks, exhibiting varying degrees of size and complexity along a continuum. This continuum encompasses abstract constructions governed by general rules to more specific constructions with variable morphosyntactic and semantic properties (Fried and Östman 2004, pp. 18–22). Consequently, grammar (or language, from a broader perspective) is viewed as a holistic framework wherein no single level of grammar is autonomous or central. Instead, semantics, morphosyntax, phonology, and pragmatics collaborate within a construction (Traugott and Trousdale 2013, p. 3). Some recent studies have applied CxG in interactive, conversational contexts so as to address different grammatical and discursive elements (e.g., discourse markers, conversational formulas, etc.). These devices can be regarded as procedural constructions based on the combination of formal, functional, and contextual properties. This branch of CG is known as interactive construction grammar (ICG) (Gras 2011; Fischer and Alm 2013).

The diachronic approach to CxG is the so-called constructionalization: this framework explains how new constructions are created and gradually developed as a result of language change (Trousdale 2014; Petré 2020). Constructionalization posits that language change occurs when “new patterns come to be entrenched not only in individual minds (‘innovations’) but come to be shared and entrenched within a community of speakers (‘changes’)” (Traugott 2020, p. 129). Specifically, constructionalization arises from conventionalization, signifying that mere innovations are insufficient to initiate the constructionalization process. Conventionalized constructions involve the emergence of new type nodes with novel syntax or morphology and coded meaning within the linguistic network of a speech community, as well as “changes in schematicity, productivity, and compositionality” (Traugott and Trousdale 2013, p. 22).

Constructionalization involves two general stages for change which can occur before or after the process of constructionalization itself: pre-constructionalization and post-constructionalization (Traugott 2015). Pre-constructionalization refers to small and local changes in specific contexts which can lead to the creation of a new micro-construction through gradualness (i.e., through small-step neoanalyses triggering changes; Traugott and Trousdale 2013, p. 22). Pre-constructionalization processes are usually associated with small semantic distributional changes (do Rosário and de Oliveira 2016, p. 244), without expecting big formal or syntactic modifications in the form–meaning pairing (Enghels and Garachana 2021). For their part, post-constructionalization processes reveal a stage in which a new meaning is completely associated with a new form, thus emerging a new consolidated construction (e.g., the periphrasis ir a + inf in Peninsular Spanish; Enghels and Garachana 2021, p. 325). Some main post-constructional features are the increase in frequencies of use, the employment of the construction with new words and contexts not previously allowed, and the change by which the new construction can become the basis for further developments in other, new, or derived constructions. Also, constructions at this stage typically involve expansion of collocations, morphological and phonological reduction (e.g., a lot of large quant experimenting expansion and phonological reductions after first pre-constructionalization processes; Traugott and Trousdale 2013, p. 27).

In this paper, we adopt an analysis model based on the [F] (form) and [M] (meaning) correlation from Croft’s 2001 model (Traugott and Trousdale 2013, p. 8; Zhuo and Peng 2016; see also Traugott 2022). Considering the orality of PE, although the total amount of data retrieved may seem small in specific timespans, it allows for the recreation of the change pattern developed by PE to serve as the basis for future research. This constructional analysis is combined with the Val.Es.Co. model (VAM). The next subsection provides a brief description of the VAM units employed in the analysis.

2.2. The Val.Es.Co. Model of Discourse Segmentation (VAM): A Complementary Tool

The VAM (Val.Es.Co. Group 2014) draws on various approaches, including conversation analysis and discourse analysis (see some foundational references in Briz et al. 2003). This model, designed for discourse segmentation, consists of eight units, hierarchically and recursively related: subact, act, intervention, exchange, turn, turn-alternance, dialogue, and discourse. These units are categorized into three orders, informative, structural, and social, and distributed across two levels, monological and dialogical, depending on whether they reflect the speaker’s individual production or the way speakers interact (see further details in Pons Bordería 2022).

Additionally, the VAM units occupy four positions: initial, medial, final, and independent. These positions are relative, implying that a specific position can be associated with different units depending on the linguistic phenomenon analyzed: for example, discourse markers can occupy the same position (e.g., initial) in different units (e.g., act, intervention, dialogue) depending on the function addressed (e.g., turn-taking, reformulation, etc.). This relative nature of positions allows for a high level of accuracy in the analysis, as well as for a closed grid crossing units and positions in a visual way (see Table 1):

Table 1.

Units and positions in the Val.Es.Co. model.

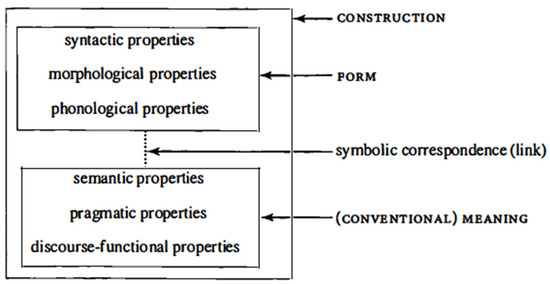

From a constructional perspective, the VAM enables a systematic description of discursive constructions, as units and positions can be integrated as part of the formal pole in constructions, connected, in turn, to the meaning pole as the basis of the functions they elicit (see Croft’s model in Figure 1). The meaning pole relies on the notion of conventionalization, which can be measured by changes in frequencies or by how a node in a consolidated construction leads to new constructions and productive subschemas (Flach 2020, p. 18).

Figure 1.

Constructional analysis proposed by Croft (Croft 2001, p. 18).

That said, transformations in units and positions in the constructional description can be seen as changes in the formal pole involving changes in the meaning pole. For the purposes of this paper, we will focus specifically on dialogues, interventions, acts, and subacts applied to examples showing a big degree of orality.1

2.2.1. Intervention

Intervention is the maximal, structural unit resulting from the content uttered by speakers in a conversation. Interventions are associated with turns, which are produced once participants accept and validate the speaker’s intervention (Pons Bordería 2022, p. 79). They can be classified into three types: initiative (iI), reactive (rI), and reactive–initiative (r-iI). Initiative interventions trigger responses from other speakers, which are reactive interventions. When a reactive intervention triggers, in turn, new responses, it becomes reactive–initiative (Espinosa 2016, p. 15). Example 6 presents these three types:

- (6)

Interventions are composed by smaller and larger units. Specifically, different interventions combine to form exchanges, which then give rise to dialogues.

2.2.2. Dialogue

Dialogue is a high-level structural unit which results from the combination of different interventions and exchanges made by different speakers. Dialogues are based on the notion of topic change, also related to interventions in the VAM: a new topic involves an initiative intervention at the beginning and a reactive intervention at the end. This can be represented schematically as follows (see Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Succession of initiative and reactive interventions within a specific dialogue (Pons Bordería and Fischer 2021, p. 106).

Dialogues also require interventions to be recognized as turns (i.e., they are based in turn-alternance). All these features of dialogue can be observed in examples 7 and 8, in which a dialogue starts with a first initiative intervention (see 7), and a new dialogue is introduced after closing the previous one with a last reactive intervention (see 8):

- (7)

- (8)

Interventions, as the basis of exchanges and dialogues, depend on their immediate, monological constituent in the VAM: the act.

2.2.3. Act

The act is the monological, structural unit, hierarchically dependent of interventions (Briz et al. 2003, p. 31; Pons Bordería 2016, p. 547). Acts in the VAM are defined by the combination of three main features: illocutionary force, propositional content, and intonation groups. The illocutionary force is recognized as a primary, main identifiable feature which can be completed with semantics and prosody as secondary features (Pons Bordería 2022, p. 95). Example 9 represents how acts are segmented in the VAM:

- (9)

Example (9) presents different interventions composed by acts: B1 produces a statement; A1 asks through an interrogation; B2 produces an affirmation; and, last, A2 also makes another statement. These different illocutionary forces are the core of each intervention produced by Speakers A and B. All these acts are annotated by using the symbol “#”.

Finally, acts are made up of lower units, the subacts. The relationship between acts and subacts establishes a bridge between the structural and the informative levels in the VAM.

2.2.4. Subact

Subacts are semantic–informative units which constitute the minimal informative, monologic level in the VAM (Val.Es.Co. Group 2014, p. 54). These units are identified by prosodic and semantic marks. Subacts are key units in the VAM since they represent the space where discourse markers, constructions, etc., can be analyzed (Pons Bordería 2022, p. 101). Depending on the type of semantic information they introduce (i.e., causes, conditions, consequences, etc.), subacts can be substantive (SS) or adjacent (AS), as observed in the following examples:

- (10)

Example (10) presents different SS based on substantive content, which can be more relevant or secondary within the intervention produced. Depending on such relevance, SS can be classified as directive substantive subacts (DSSs) and subordinate substantive subacts (SSSs). DSSs are highly informative; SSSs are semantically and informatively dependent on DSSs. In this case, the SSS expands the information included in the previous DSS.

SS are combined with AS. Adjacent subacts are namely based on procedural meaning and can also be subclassified into further categories: textual adjacent subacts (TASs), modal adjacent subacts (MASs), and interpersonal adjacent subacts (IASs). The meaning behind AS does not affect the propositional content underlying acts (i.e., their logical form; Pons Bordería 2016). As a result, they could be deleted from any example without provoking a loss of conceptual meaning as would happen with SS. The following example includes different types of AS:

- (11)

In Example (11), TASs organize and distribute the flow of speech; they reflect the relationship between the ideas expressed and the discourse. MASs allow speakers to modalize the discourse they are related to; they highlight the relationship between the speaker and his/her own discourse. Last, IASs show how speakers interact to each other in a discourse; then, they highlight the relationship between speaker and hearer(s).

3. General Features of PE in Peninsular Spanish

Peninsular Spanish PE has been commonly described as a conversational formula derived from the Spanish discourse marker pues (Álvarez 1999; Briz 1993; Pons Bordería 1998; see also Iglesias 2000 for a diachronic approach until the 15th century). As argued in Salameh Jiménez (2020b, pp. 110–11), the pragmatic uses of pues (e.g., formulation, or cataphoric–anaphoric values introducing non-preferred answers; Briz 1993, p. 156) have triggered new, fixed combinations with other linguistic items (e.g., pues nada, pues bueno, pues bien, pues vale; Salameh Jiménez, Forthcoming(a)). Also, PE is determined by the deictic, neutral pronoun eso, which creates a cognitive space leading to non-tangible elements such as ideas or concepts without explicit mention (De Cock 2013, p. 11). In particular, the neutral pronoun eso is related to vagueness processes produced in the so-called abstract region (Achard 2001), in which any discursive content could be placed (i.e., fillers, formulative devices, etc.).

All these features have contributed to the fixation of pues and eso even earlier than other formulas based on a schematic abstraction of pues (Salameh Jiménez, Forthcoming(a)). In PE, some original properties from both items have been integrated into its meaning basis to some extent; however, some new properties have been acquired in new contexts (Croft and Cruse 2008, p. 350). Thus, the functions of PE cannot be addressed as only the compositional combination of the meanings behind the original forms. This formula presents five different functions (see Section 1): formulation, reinforcement, back-to-topic, agreement, and closing mark (Salameh Jiménez 2020b).

Formulations with PE are produced when the speaker discusses a specific topic and further information needs to be added to make the conversation progress. Whether the speaker cannot find immediately the most precise words, PE establishes a pause to search for the new content and also allows them to maintain the floor in the conversation, like in Example (12):

- (12)

Reinforcement allows speakers to emphasize the illocutionary force associated with their statement, which constitutes a propositionally complete content, as shown in (13). Most parts of reinforcement contexts are also related to self-conclusions, especially employed in the final position.

- (13)

The back-to-topic use of PE is very common in colloquial conversations: speakers tend to make (micro-)changes of topic in the flow of a conversation and, later, they decide to come back again to one of the topics previously addressed by the group. In these cases, the speaker also employs PE as a turn-taking device, as observed in (14):

- (14)

In dialogical contexts, PE can work as an agreement mark, in some cases even functioning itself as a response intervention. It becomes an explicit expression of acceptance of what is said by another speaker, as in (15):

- (15)

Last, the closing mark in PE highlights how speakers end a topic they were talking about and allows for introducing a new one, which can be made by the same speaker or by another speaker. In these contexts, PE can be combined with other discourse markers, such as nada or bueno, as shown in (16):

- (16)

As said, these five functions have been developed by combining form and meaning changes throughout time, abandoning compositional processes. To detect how these changes happened, we adopt a constructionalization approach incorporating some useful descriptive notions, such as the pre- and post-constructional changes (also, see Brinton’s 2023 recent work on the evolution of what-general extenders in English).

4. Results

4.1. Data Compilation and Analysis Parameters

The diachronic study of orality through written texts is commonly assumed by researchers, given that recreations of interaction can be found in literary texts, which allows for understanding how real variation was in the past (Del Rey Quesada 2020). Thus, a play presenting an oral use of a linguistic item could reveal that this specific linguistic item was being diffused or conventionalized in a time period (see also López Serena and Rivera 2018).

All the samples of PE in Peninsular Spanish have been compilated from the Corpus del diccionario histórico de la lengua Española (CDH) from the Real Academia Española (RAE), which is composed of 355,740,238 items distributed as follows: (a) the nuclear CDH section, covering more than 32 million texts from Peninsular Spanish; (b) the CORDE section, which includes texts from the Corpus Diacrónico del Español since the 12th century to 1975; and (c) the CREA section including texts from 1975 to 2000. The fact that the CDH includes a big number of materials from CORDE and CREA supports its representativity for the purposes of our study.

All the examples have been manually extracted and classified depending on the degree of fixation in PE (i.e., cases without fixation (17) and cases with fixation (18)):

- (17)

- (18)

Examples without fixation of pues and eso have also been analyzed so as to detect first documentations of non-compositional uses of PE, especially in those cases related to bridging contexts in the language change process. This part of the study has been key also in detecting pre-constructional changes previous to the complete constructionalization. The analysis is based in the following linguistic properties: morphosyntactic (syntactic integration or liberation, scope, including positions and units, as well as changes from the monological to the dialogical level), semantic (bleaching in meaning, changes in meaning in pues and eso, etc., acquisition of new degree(s) of (inter)subjectivity), and pragmatic (new contextual invited inferences). The VAM will be considered part of the form pole within the construction.

4.2. Results

A general approach to the quantitative data suggests some relevant information from frequencies. There are a total of 733 tokens of pues and eso in the CDH, including both compositional and constructionalized cases. Table 2 summarizes the distribution of the 733 cases per century and the normalized frequencies from the CDH corpus (all the words per century):

Table 2.

Total amount of compositional/constructionalized cases of pues and eso in the database, with normalized frequencies from the CDH corpus (Spain).

A focus on the data reveals a first, intuitive idea of the dialogicity behind this conversational formula: a total of 170 tokens of 733 in the database are related to dialogical texts. This means that the combination of pues and eso, fixed or not, has appeared almost 200 times in the database in contexts reproducing interaction in novels and plays, specifically introducing answers to the interventions made by others. As observed in Table 3, a clear increase in PE in these dialogical contexts is detected since the 19th century, which would reveal that the constructionalization of this formula would be apparently completed in these centuries:

Table 3.

Cases of pues and eso related to dialogical contexts in the database (Spain).

Nevertheless, an automatic search alone is insufficient to draw definitive conclusions. The analysis of the remaining 562 tokens is essential to understand why PE became established as a construction and why its scope expanded from monological to dialogical contexts. It is also crucial to examine the earlier stages of the construction, even before it functioned as a parenthetical device, in order to trace the pattern by which a connective followed by a neutral deictic changed into a fixed response and how it acquired textual, modal, and interactive uses.

That said, the PE data reveal three primary stages in the constructionalization process: non-constructionalized PE (Section 4.2.1), constructionalization in progress (Section 4.2.2), and constructionalized PE (Section 4.2.3). These stages, in turn, are associated with pre- and post-constructionalization processes. Pre-constructional changes are initiated in the first and, notably, in the second stage, while post-constructional processes are a part of the third stage, where the constructionalization of PE appears to be completed for at least four out of five values.

4.2.1. First Stage: Non-Constructional PE

As anticipated, the initial instances of PE found in the database exhibit a compositional, non-constructional meaning. This implies that pues and eso are not part of the same integrated structure, which can be verified through various formal linguistic tests. Consider the following example from the 15th century:

- (19)

In (19), there is a combination of pues and eso in which pues works as a conjunction, relating the utterance it introduces to a previous cause expressed through the preceding utterances, while eso functions as a neutral pronoun, serving as a deictic reference to all previously mentioned information (i.e., functioning as an anaphoric device). Morphosyntactically, eso is fully integrated into the sentence, as evidenced by its predication relationship with the verb “es” (to be) and other complements. It admits the substitution of the deictic “eso” by other neutral devices that refer to the preceding content (e.g., pues lo que tú dices, pues aquello que tú dices, pues la cosa que tú dices, etc.). Importantly, eso is used within lengthy sentences and even subordinate clauses. Semantically, there is no bleaching or reanalysis that leads to new pragmatic uses of pues + eso; instead, they retain their original, fundamental meanings that are not associated with a potential schematic construction based on pues. Finally, according to the VAM, pues and eso would be categorized within the directive substantive subact (DSS) with scope over the following subordinate substantive subact (SSS). This reflects their non-liberation or non-consolidation as a construction.

Example (20) also presents uses of PE which are part of the sentence level, without syntactic complete freedom:

- (20)

The difference regarding cases like (19) is that pues introduces a conclusion derived from the previous utterances (i.e., it does not only mark a cause–consequence relationship within a sentence) and that it works as a connective mark which could be deleted from the sentence without a loss of meaning:

(…) y tornándolo a traer, luego torna a desaparecer, y como una anguila se nos cuela por entre las manos. Eso es lo que principalmente hace dificultosísimo este ejercicio.And when we bring it back, it immediately disappears again, slipping through our hands like an eel. This is what primarily makes this exercise extremely difficult.

Nevertheless, these examples are still compositional and do not show any degree of constructional (semi)fixation. The database retains a total of ca. 170 compositional contexts of pues and eso, which is expected since the connective pues has not disappeared or been replaced by other constructions that it may have triggered (indeed, pues and other derived constructions, such as PE, pues nada, or pues bien would not be placed at the same level within a constructional network). Table 4 provides a summary of their distribution throughout centuries in the corpus, including normalized frequencies:

Table 4.

Cases of pues and eso in the first, compositional stage in our database (Spain).

4.2.2. Second Stage: Constructionalization in Progress

The second stage encompasses initial, bridging uses of pues and eso, involving some reanalysis processes that alter specific aspects of meaning and pragmatic values. Continuative and illative original values of pues are key in this second stage so as to lead to pre-constructionalization constructional shifts. Notably, during the 16th and 17th centuries, agreement and reinforcement marks appear to be activated in contexts where the construction is not yet fully established. Of particular relevance for the analysis is the combination of pues and eso with specific verbal constructions and, in a more fixed form, with mismo (adj.; pues eso mismo) in dialogic contexts, where it serves as a response, or in monological contexts, reinforcing the speaker’s own statements. A closer examination of these initial uses suggests a formal–functional specialization of PE, contributing to a new, less compositional meaning that precedes new parenthetical uses (see Section 4.2.3).

4.2.2.1. Agreement Mark

Examples (21) and (22) illustrate the emergence of the first continuative values marked by the agreement feature, represented schematically as PE + V:

- (21)

- (22)

In these instances, pues eso remains integrated at the sentence level, albeit with a degree of syntactic liberation reflected in certain morphosyntactic features. In contrast to examples (19) and (20), pues eso now reduces the number of verbal complements and limits its compatibility with subordinate clauses (e.g., pues eso que). As a result, the length of the utterance containing pues eso is shorter. Both pues and eso are used in a dialogical context, where pues serves to introduce a continuation of the previous discourse through a response.

These dialogical contexts may trigger reanalysis derived from the continuative original value of pues, employed specifically to accept something stated by others or provide further information to a previous intervention (Briz 1993). However, it is essential to note that the constructionalization process is not yet complete. The neutral pronoun eso can function as both a subject and a direct object, indicating a lack of morphosyntactic freedom and suggesting that its removal would result in a loss of grammatical meaning. Additionally, segmentation using the VAM units confirms that pues and eso do not yet constitute a fully adjacent subact (AS). “Pues” can be tagged as a textual adjacent subact (TAS), while the remainder of the sentence, including eso, belongs to the directive substantive subact (DSS). This pattern is consistent across other examples in the corpus, indicating some degree of compositionality.

In summary, the combination of form and meaning parameters reveals an ongoing change. The possibility of new pragmatic interpretations stemming from pues and their expression through eso within a broader paradigm of neutral devices signifies a change, as reflected in formal parameters (e.g., morphosyntactic reduction, verbal restrictions). Furthermore, there is a positional and scope transformation evident in the VAM units: examples from the initial stage were typically positioned within the medial part of the DSS, whereas the new uses in agreement contexts are now placed at the initial position of the intervention, creating a new context for the use of pues.

Similarly, (23) shows an instance of first uses of pues and eso within a more specific agreement construction:

- (23)

Morphosyntactically, both elements are still integrated into the sentence structure and allow for additional verbal complements. However, there is a reduction in length. Additionally, combinations with other verbs appear less frequent, resulting in clearer, explicit agreement, functioning as an echoic marker. Semantically, the meaning of pues and eso becomes more constrained due to the explicit agreement expressed through devices like mismo, which unambiguously refer to the preceding information in conjunction with the neutral deictic eso.2

From a pragmatic perspective, this structure can be interpreted in two ways due to the illocutionary force expressed: a literal reading, where Speaker B is simply echoing Speaker A, and a non-literal reading that triggers an invited inference of acceptance, further reinforced. This functional specialization in using pues and eso restricts the introduction of refusals in these contexts, which involves a bleaching process in the meaning, particularly with the inferential value of eso becoming more prominent.

In contrast to the previous examples, these cases cannot be segmented in the same manner according to the VAM. Pues eso mismo te digo or Pues eso mismo as parentheticals might possess a procedural meaning in dialogic contexts, contributing to the constructionalization process (see Cuenca 2017). However, these examples cannot be categorized as pure textual adjacent subacts (TASs), given that a conceptual basis is evident in the structure. Pues would be clearly tagged as a TAS, as summarized in the following schema comparing the first and second stages through the VAM:

- -

- First stage of PE > # ACT # {DSS} (pues eso within the Directive Substantive Subact)

- -

- Second stage of PE > Reactive intervention #ACT# {TAS} (pues eso as Textual Adjacent Subact)

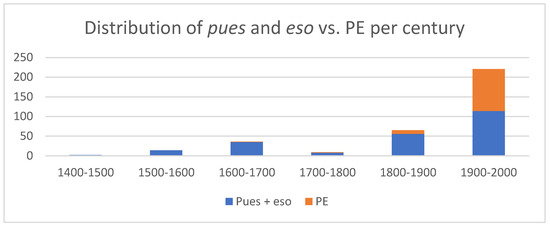

To sum up, the agreement mark function of PE seems to be directly originated from pues used in clear dialogical contexts introducing responses since the 15th century (see Iglesias 2000). These responses do not only agree with what is said but also allow for evaluating and adding further information to the previous intervention. This association of eso with pues in dialogic contexts will facilitate the evolution into more restrictive contexts linked to specialized responses geared towards explicit agreement. As observed in Figure 3, these uses of pues have been kept in the database until the present in coexistence with the constructionalized PE, triggered in the 19th century and consolidated in the 20th century (see also Section 4.2.3):

Figure 3.

Distribution of pues and eso vs. PE per century in the database (Spain).

4.2.2.2. Development of the Reinforcement Value

The reinforcement value developed concurrently with the agreement mark value, as seen in Example (24):

- (24)

In (24), there is a monological context in which pues introduces a response to a preceding rhetorical question uttered by the same speaker. Morphosyntactically, this response, which includes pues and eso, forms a compact structure with a copula. There is limited syntactic flexibility and removing pues and eso would alter the propositional basis of the sentence. There is no semantic bleaching since the use of pues is connective, and eso works as a subject, referring to the immediate content introduced (eso es ser Jesús, En. This is Jesus Christ). In this context, the utterance can be interpreted literally, and no additional inferences are implied pragmatically. Nevertheless, a crucial point for analysis is the new position occupied by pues and not found in other previous monological texts, potentially leading to further developments for this connective involving changes in scope and new functional uses combined with eso.

Example (25) exhibits similar features, with eso clearly referencing the preceding rhetorical question:

- (25)

Examples such as (25) appear later in our database (since the 17th century). They reflect a shift in pues, previously used in reproduced dialogues to introduce responses by different speakers: now, it mirrors a dialogic structure based on an adjacent “question–answer” pair apparently produced by different speakers but presented by the same writer/speaker. This shift also introduces a degree of polyphony and reflects an influence from the expletive value. In Example (25), pues and eso can accommodate additional elements that reinforce the anaphoric reference (e.g., the adjective mismo). As observed, the illative value is more relevant than the original, basic consequence meaning of pues, which is not activated in these new contexts. Unlike Example (24), modifying or even omitting the rest of the utterance in this context does not result in a complete loss of meaning.

A total of 35 examples spanning from the 16th to the 19th centuries display these characteristics, marking a preceding micro-stage in the development of reinforcement values. Specifically, the position occupied by pues in conjunction with eso creates room for the emergence of new pragmatic meanings related to intangible elements like ideas or concepts without explicit mention (see Section 4.2.3). This is corroborated by the analysis using the VAM, which clearly illustrates the modification affecting the form pole: apparently, pues occupies a medial position. A zoom through the VAM, however, shows an initial position of act; pues would be tagged, again, as a TAS.

This said, agreement and self-reinforcement functions in the second stage are experimenting a (semi)fixation, not a completed process. This is supported by the VAM since PE cannot be addressed as a free, adjacent unit (i.e., TAS, MAS, or IAS). The only item that can be tagged as a TAS is pues, showing specific modifications in the scope which are key to be fixed with eso as part of the same construction. There are no instances neither bridging formulation, back-to-topic, or closing mark uses in this stage.

4.2.3. Third Stage: Constructionalized PE

According to the data, the agreement and self-reinforcement values in progress in the second stage are established during the 19th century and consolidated in the 20th, especially during the second half of the century. This third stage is also related to post-constructionalization changes, which is supported by frequencies and by the development of new functions not previously detected, such as formulation and back-to-topic, as well as by the development of similar constructions based on pues (see Section 5).

Regarding the agreement mark, there are some first examples in the 17th century. However, the increase in frequencies takes place since ca. 1850. Observe Examples (26) and (27):

- (26)

- (27)

Example (26) was documented in the 17th century. This dialogical context shows a first parenthetical use of pues eso in which the meaning is not compositional and goes beyond the continuative value derived from pues in the second stage. As observed, Franco replies to Federico through pues eso and even introduces further content to the discourse, but this new content does not depend on pues and eso. Morphosyntactically, there is a wider reduction of the structure: from <pues eso + subordinate sentence with “que”> to <pues eso + verbal complements> and, finally, to <PUES ESO>. This agreement construction could still admit “to say” verbs (pues eso digo), but they are not very frequent in our database, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries. This structure does not admit negation (e.g., pues no eso), which also reveals a high degree of fixation.

Semantically, there is a bleaching on the original meaning of pues and eso, also derived from the acquisition of meanings from other elements they were combined with previously (pues eso mismo, pues eso claro está, verbs such as decir, etc.). Pragmatically, there are new invited inferences by which the interpretation is not literally an echoic repetition of what is said, but rather a clear intention of agreeing with the other speaker. In these contexts, pues eso could be substituted by agreement marks, such as exacto. Example (27) confirms this change: Speaker B replies to A through this PE construction with a new codified meaning: total agreement as answer in an adjacent pair. As mentioned earlier, the bleaching process appears to be complete, as the use of PE now allows reference to intangible elements, even those not previously mentioned.

As summarized in Table 5, the number of cases documented in our database has increased since the 20th century, suggesting a consolidation of these oral uses (see Table 4). The construction PE as an agreement mark still allows for some variation, including verbs (e.g., pues eso digo, pues eso es lo que digo yo, pues eso es), but this occurs only in a few cases in poems and novels, seemingly determined by the stylistic choices of their authors.

Table 5.

PE as consolidated agreement mark in our database (Spain).

The consolidation of the agreement function involves a new analysis with the VAM, reflecting changes in the form–meaning features through positions and units: contrary to first and second stages, PE as a parenthetical is tagged as interactive adjacent subact (IAS) in an independent intervention, with a new scope over the whole previous intervention. Also, it can be related to further content, thus tagged as an IAS placed at the initial position of the intervention. As observed, pues and eso are part of the same structure and cannot be addressed as different units (i.e., pues is an IAS and eso as part of a DSS, like in previous examples). The new position and unit acquired by PE are linked to its semantic bleaching and the new pragmatic readings developed, which also differ from previous cases employing pues as a continuative mark introducing responses.

Regarding the self-reinforcement function, the first examples of the completed construction are detected since 1900, as observed in (28):

- (28)

In (28), PE shows features similar to example (27): morphosyntactically, it is a free item which can be replaced or deleted from the discourse without provoking a loss of meaning, and there is a clear semantic bleaching by PE expressing a meaning not coded only in the combination of pues and eso but also complemented by a new inferential meaning by which information or an opinion can be highlighted by the speaker himself. This function goes beyond the agreement mark or the answer value detected in the database during previous centuries. There is even a certain degree of liberation from the rhetorical question–answer structure found before, which constitutes the point of departure for this function, as observed in the next example:

- (29)

According to the VAM, PE would be placed at the final position of an act, over which it has scope, and tagged as a modal adjacent subact (MAS). Again, this involves a change in the parameters of the construction: PE working as an agreement mark can only be addressed as an IAS in a different position and with a different scope compared to self-reinforcement, oriented to the way the speaker put illocutionary force in the message.

Our database reveals the consolidation of PE in self-reinforcement contexts also during the 20th century (see Table 6). These data include the completely parenthetical stage of the construction, as a continuation of the data retrieved in the second stage (see Section 4.2.2.2). Interestingly, contexts of rhetorical question–answer continue being employed by contemporary speakers in Peninsular Spanish.

Table 6.

PE as a self-reinforcement construction consolidated mark in our database (Spain).

Last, the formulation and the back-to-topic functions are detected as part of the complete constructionalization process since the 19th century onwards. The database, however, shows only a few cases of closing mark. Observe Examples (30) and (31):

- (30)

- (31)

A total of 41 examples in the database, all extracted from novels and authentic discourses (interviews in radio or TV) from the 20th century onwards, exhibit the same structure as (30). These examples reflect a complete PE construction, including all the linguistic features associated with the third stage. This results in a new, reanalyzed form–meaning pairing oriented towards formulation (i.e., parenthetical, new meaning beyond the combination of pues and eso, employed in new pragmatic contexts, etc.). PE functions as a type of oral pause, allowing the speaker to think on the next idea to be introduced (e.g., que está contenta con lo nuestro). According to the VAM, formulation introduces new units and positions, specifically in the medial position within the uttered act, over which PE holds influence as a textual adjacent subact (TAS).

Beyond formulation, the most recent developments of PE identified in the database pertain to the back-to-topic function. As illustrated in Example (31), PE enables the speaker to return to a previously mentioned topic or idea that had been set aside following a digression. In this instance, Miss Dolores and Maria were discussing job opportunities at their home. After receiving a negative response and engaging in an extended discussion about Maria’s qualifications as a housekeeper, Maria revisits the main topic regarding the possibility of working at Luisa’s house. Although the number of back-to-topic examples in the database is limited, their documentation suggests that this function became established at a later stage. The VAM analysis also reveals functional distinctions compared to other functions of PE: it is once again categorized as a textual adjacent subact (TAS), but it is positioned at the initial position within the intervention, with influence over prior interventions.

This is similar to cases involving closing marks: there are no conversational instances in which PE is employed to conclude a first topic in the final position of a reactive intervention and dialogue (as discussed in Section 3). Instead, there are only five cases (from 1995 to 1997) that appear to exhibit this function, as the writer closes one topic and may open another:

- (32)

In these cases, there is a reanalysis by which PE presents only textual properties organizing the discourse. According to the VAM, it would be tagged as a TAS in the final position of the dialogue and even discourse.

To sum up, the functional development of PE across the units and positions within the VAM enables us to create a visual representation of the constructionalization process completed in the third stage. Initially, the values of pues were confined to the act or the intervention, with a more limited scope (see Table 7):

Table 7.

PE in the VAM grid.

Each unit and position, in turn, is associated with the set of form and meaning features described in Section 4.2. In turn, the evolutive pattern followed by PE in the third stage can be traced by including the date of the first documentation of each function developed in the combination unit × position (see Pons Bordería 2018 for further diachronic evolutions of discourse markers in Peninsular Spanish through the VAM). See Table 8:

Table 8.

First documentations of PE in the VAM grid.

As seen, PE abandons subacts and develops a new preference for medial and final positions in the 20th century, which differs from the original values of pues with a narrower scope and a more reduced positional distribution.

5. Discussion

The findings of the analysis show that PE becomes a complete conversational formula in the 20th century, but that there is a bridging change stage (i.e., the second stage) which is relevant for this constructionalization process. In particular, the agreement and self-reinforcement functions seem to be developed earlier before the consolidation of the parenthetical combination of pues and eso. This second stage corresponds to pre-constructional changes leading to the new construction (e.g., contextual restrictions, changes in the morphosyntactic features, such as combinations with new complements and more specific verbs, new pragmatic readings, and gradual expansion, etc.). In addition, post-constructional changes take place in the third stage, as shown by the development of new functions derived from the new consolidated ones, not previously found in the database (i.e., formulation, back-to-topic, and closing mark), as well as by the clear loss of compositionality and structural reduction (Traugott and Trousdale 2013). Also, PE seems to be integrated into a bigger constructional network, as shown by other formulas such as pues nada or pues vale, commonly employed in colloquial, spoken discourses and also popularized during the 20th century (e.g., pues nada; Salameh Jiménez, Forthcoming(a); see also pues bien in Octavio de Toledo 2018). The development of other similar constructions suggests a productive constructional schema behind pues which must be diachronically addressed.

As shown, constructionalization as a framework explains how conversational formulas such as PE are conventionalized (i.e., an increase in frequencies of use in the 19th and 20th centuries in tandem with the acquisition of new form and meaning features), in line with other discursive devices which are not discourse markers but develop similar functions (e.g., general extenders; Borreguero Zuloaga 2023). While certain features of PE can be elucidated through grammaticalization, such as reduction, decategorialization, and layering in Hopper’s framework, the complete spectrum of features associated with PE does not conform entirely to grammaticalization processes (e.g., there is no phonetic reduction; rather, there is a case of elision from complete clauses to truncated clauses; Brinton 2023, p. 25; in addition, the bleaching process is less transparent since the neutral deictic eso keeps some kind of referential meaning which cannot be completely erased). A constructional approach is also compatible with some basic principles of grammaticalization and would also explain the way pues and eso become PE: a “conversational formula” would be the more abstract level, composed of instances of the second stage of PE working as a (semi)fixated construction (e.g., pues X as an answer, rhetorical question–answer introduced by pues) which, in turn, includes fewer schematic formulas triggered later (e.g., pues eso mismo le advierto, pues eso digo, pues eso es, etc.), before the definitive rise of PE. These more abstract levels would also be related to the development of other pues-based constructions (Salameh Jiménez, Forthcoming(a)).

Regarding the data, some specific aspects can also be discussed: this first diachronic analysis of PE allows for proposing specific periods explaining its evolution. These periods are based on the data retrieved from a representative corpus in Peninsular Spanish covering different centuries and examples from the 20th century (i.e., the CDH). Form and meaning changes detected in each stage can constitute the point of departure for deeper research on PE which requires new data sources. For example, some of the first examples of constructionalized PE belong to texts published by specific authors writing novels and plays reproducing oral interaction since the 19th century (e.g., Pérez Galdós, Aub, Sánchez Ferlosio, Pardo Bazán, etc.). Thus, a focus on this period is suggested so as to retrieve further examples of agreement and self-reinforcement functions in oral contexts and, especially, to check whether formulation, back-to-topic, or closing marks were triggered later or maybe before the 20th century. Similarly, examples from the second stage could also be explored from discourse traditions (Llopis-Cardona 2022) by addressing specific types of texts and stylistic features in writers employing pues and eso (e.g., religious texts; Traugott 2010). This, again, invites us to address a possible relationship between those first uses, probably idiosyncratic, and their diffusion.

Last, the analysis shows that the incorporation of the VAM units and positions as part of the form meaning allows for a clearer association with the semantic and pragmatic changes experimented by PE as a new construction (Pons Bordería 2018): the uses of pues and eso in the first stage are part of directive substantive subacts (DSSs) within acts; cases of pues and eso developing dialogical features in the second stage involve a new segmentation by which pues works as a textual adjacent subact (TAS) introducing the rest of the DSS in which eso is inserted; finally, PE parenthetical cases in the third stage can be tagged as interactive adjacent subacts (IASs) for the agreement function, modal adjacent subacts (MASs) for the self-reinforcement, and textual adjacent subacts (TASs) for formulation, back-to-topic, and closing marks. This suggests an interpersonal > modal > textual cline, in line with other works in different languages (Scivoletto 2023). These transformations in units are also combined with positional changes (from medial in subacts to initial in interventions, and medial and final in acts and even dialogues).

6. Conclusions

The diachronic study of PE in Peninsular Spanish has remained unexplored, mainly due to the spoken, colloquial nature of this conversational formula, which could hinder data obtention. However, a first analysis of the CDH (RAE) has shed some light on its evolution, with a total of 732 tokens classified into three stages according to the degree of fixation detected. By adopting a constructional approach (Traugott 2020), results reveal that the different current functions covered by PE were consolidated during the 20th century, with special attention to previous developments in the 16th and 17th centuries, when agreement and self-reinforcement functions seem to have originated. In turn, formulation, back-to-topic, and closing marks were triggered later, as part of post-constructional changes.

Our results allow comparisons with the development of other similar discursive devices, such as general extenders (e.g., y eso, y nada, y todo; López Serena 2018) and fit results from other works dealing with grammaticalization processes finished in the 20th century (see Salameh Jiménez 2020b; Pardo-Llibrer, Forthcoming). Some tasks, however, need future research to be done: first, the second and third stages require further data focusing on specific text types, especially in the 20th century with other complementary corpora to be explored (Biblioteca Virtual de Prensa Histórica; or spoken colloquial corpora, such as Val.Es.Co. in its initial era—i.e., 1990s—spontaneous interviews from PRESEEA, etc.). Additionally, the consolidation of formulation, back-to-topic, and closing marks could be checked through interviews with 60–80-year-old speakers, complementing the data retrieved. Second, a diachronic approach to other closer conversational formulas, such as pues nada, pues bien, or pues vale, is needed to complete the constructional network to which pues belongs, as well as to measure the schematicity and productivity behind PE as a possible influence for their development. Again, the use of the VAM units as part of the form pole will be useful in systematizing all the functional transformations experimented by (semi)completed constructions.

Funding

This research was funded by the projects CIPROM/2021/038 Hacia la caracterización diacrónica del siglo XX (DIA20), Generalitat Valenciana, and I+D+I PID2021-125222NB-IOO Aportaciones para una caracterización diacrónica del siglo XX, MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/ and FEDER, Una manera de hacer Europa.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it involved no experimenting with humans. The analysis was carried out through an already existing corpus from the Real Academia Española (Spain), which is publicly accessible online.

Informed Consent Statement

Not aplicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the examples retrieved for this analysis can be found at https://apps.rae.es/CNDHE/. Accessed on: 28 September 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The diachronic application of the VAM is possible, as shown by previous studies dealing with grammaticalization processes in discourse markers (Salameh Jiménez 2020a). Although the VAM was initially created to analyze colloquial conversations, further developments have been carried out to address other oral–written genres (interviews and social gatherings, Briz 2013; football broadcastings; Salameh Jiménez, Forthcoming(b); and, more recently, written journalistic texts, Pons Bordería 2022). |

| 2 | A search for “eso mismo” in the CDH to determine whether it functions as a consolidated formula in parallel with “pues eso mismo” reveals that there is no interdependence between them. “Eso mismo” is often combined with “E eso mismo” or “Y eso mismo”, but these combinations have a different, non-continuative meaning. |

References

- Achard, Michel. 2001. French ça and the Dynamics of Reference. In LACUS Forum 27: Speaking and Comprehending. Edited by Ruth M. Brend, Alan K. Melby and Arle R. Lommel. Toronto: Linguistic Association of Canada and the United States, pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, Alfredo. 1999. Las construcciones consecutivas. In Gramática de la lengua española. Tomo III. Directed by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa Calpe, p. 3741. [Google Scholar]

- Arguedas, Maria Estellés. 2011. Gramaticalización y paradigmas. Un estudio a partir de los denominados marcadores de digresión en español. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Boas, Hans. 2010. Comparing constructions across languages. In Contrastive Studies in Construction Grammar. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Borreguero Zuloaga, Margarita. 2023. La gramaticalización de los apéndices generalizadores en español. Fenómenos de diacronía del s. XX. Boletín de Filología 58: 211–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinton, Laurel. 2023. The rise of what-general extenders in English. Journal of Historical Pragmatics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briz, Antonio. 1993. Los conectores pragmáticos en la conversación coloquial (II): Su papel metadiscursivo. Español Actual: Revista de español vivo 59: 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Briz, Antonio. 2013. Variación pragmática y coloquialización estratégica. El caso de algunos géneros televisivos (la tertulia). In (Des)cortesía para el espectáculo: Estudios de pragmática variacionista. Edited by Catalina Fuentes. Madrid: Arco Libros, pp. 89–125. [Google Scholar]

- Briz, Antonio, Antonio Hidalgo, Xose Padilla, Salvador Pons, Leonor Ruiz Gur1llo, Julia Sanmarhn, Elisa Benavent, Marta Albelda, María José Eernández, and Montserrat Pérez. 2003. Un sistema de unidades para el estudio del lenguaje coloquial. Oralia 6: 7–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDH. n.d. CDH from the Real Academia Española. Available online: https://www.rae.es/banco-de-datos/cdh (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Croft, William. 2001. Radical Construction Grammar: Syntactic Theory in Typological Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, William, and Alan Cruse. 2008. Lingüística Cognitiva. Madrid: Editorial Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, Maria Josep. 2017. Connectors gramaticals i connectors lèxics en la construcció discursiva del debat parlamentari. Zeitschrift für Katalanistik 30: 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cock, Barbara. 2013. Entre distancia, discurso e intersubjetividad: Los de mostrativos neutros en español. Anuario de Letras: Lingüística y Filología 1: 5–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey Quesada, Santiago. 2020. Hacia una diacronía de la oralidad: El inicio de turno y la inmediatez comunicativa en un corpus de traducciones de Plauto y Terencio (ss. XVI y XIX). Lexis 44: 41–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Delin. 2023. The Grammaticalization of the Discourse Marker genre in Swiss French. Languages 8: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Rosário, Ivo da Costa, and Mariângela Rios de Oliveira. 2016. Funcionalismo e abordagem construcional da gramática. Alfa Revista de Lingüística 60: 233–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enghels, Renata, and Mar Garachana. 2021. Grammaticalization, lexicalization and constructionalization. In The Routledge Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics. Edited by Wen Xu and John R. Taylor. London: Routledge, pp. 314–32. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, Guadalupe. 2016. Dientes de sierra: Una herramienta para el estudio de la estructura interactiva del discurso dialógico. Normas 6: 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estellés Arguedas, Maria, and Salvador Pons Bordería. 2014. Absolute Initial Position. In Models of Discourse Segmentation in Romance Languages. Edited by Salvador Pons Bordería. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 121–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fagard, Benjamin, and Alexandru Mardale. 2015. The pace of grammaticalization and the evolution of prepositional systems: Data from Romance. Folia Linguistica 46: 303–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillmore, Charles J. 1988. The mechanisms of ‘Construction grammar’. Paper presented at the Fourteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Berkeley, CA, USA, February 14–15; vol. 14, pp. 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Kerstin, and Maria Alm. 2013. A radical construction grammar perspective on the modal particle-discourse particle distinction. In Discourse Markers and Modal Particles: Categorization and Description. Edited by Liesbeth Degand, Bert Cornillie and Paola Pietrandrea. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 47–88. [Google Scholar]

- Flach, Susanne. 2020. Constructionalization and the Sorites Paradox. The emergence of the into-causative. In Nodes and Networks in Diachronic Construction Grammar. Edited by Lotte Sommerer and Elena Smirnova. Constructional Approaches to Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 27, pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, Mirjam, and Jan-Ola Östman. 2004. Construction Grammar in a cross-language perspective. Studies in Language 31: 479–85. [Google Scholar]

- Garachana, Mar, and María Sol Sansiseña. 2023. Combinatorial Productivity of Spanish Verbal Periphrases as an Indicator of Their Degree of Grammaticalization. Languages 8: 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givón, Talmy. 1971. Historical syntax and synchronic morphology: An archaeologist’s field trip. Chicago Linguistic Society 7: 394–415. [Google Scholar]

- Gras, Pedro. 2011. Gramática de Construcciones en Interacción. Propuesta de un modelo y aplicación al análisis de estructuras independientes con marcas de subordinación en español. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Haspelmath, Martin. 1999. Why is grammaticalization irreversible? Linguistics 37: 1043–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, Paul. 1991. On some principles on grammaticalization. In Approaches to Grammaticalization. Edited by Elizabeth Closs Traugott and Bernd Heine. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, vol. I, pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Paul, and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. 2003. Grammaticalization. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, Silvia. 2000. La evolución histórica de pues como marcador discursivo hasta el siglo XV. Boletín de la Real Academia Española LXXX: 209–307. [Google Scholar]

- Llopis-Cardona, Ana. 2020. Funciones, posición y unidades discursivas en no sé y yo qué sé. In Aportaciones desde el español y el portugués a los marcadores discursivos treinta años después de Martín Zorraquino y Portolés. Edited by Antonio Da Silva, Catalina Fuentes and Manuel Martí-Sánchez. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, pp. 249–72. [Google Scholar]

- Llopis-Cardona, Ana. 2022. El cambio de entorno y evocación en las tradiciones discursivas: Propuesta y aplicación al caso de en definitiva. ELUA: Estudios De Lingüística. Universidad De Alicante 37: 185–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Serena, Araceli. 2018. Hacia una revisión de la caracterización semántica y discursiva de la locución y eso que en español actual. ELUA: Estudios De Lingüística. Universidad De Alicante 32: 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Serena, Araceli. 2023. Discourse traditions and variation linguistics. In Manual of Discourse Traditions in Romance, 1st ed. Edited by Esme Winter-Froemel and Álvaro S. Octavio de Toledo y Huerta. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, vol. 30, pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- López Serena, Araceli, and Daniel Sáez Rivera. 2018. Procedimientos de mímesis de la oralidad en el teatro español del siglo XVIII. Estudios Humanísticos: Filología 40: 235–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octavio de Toledo, Álvaro. 2018. Paradigmaticisation through Formal Ressemblance: A History of the Intensifier bien in Spanish Discourse Markers. In Beyond Grammaticalization and Discourse Markers. Edited by Salvador Pons Bordería and Óscar Loureda Lamas. Studies in Pragmatics: New Issues in the Study of Language Change, 18. Leiden: Brill, pp. 160–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Llibrer, Adrià. Forthcoming. From vocative contexts to digressive uses. On Spanish ‘ah’. In From Intersubjective to Textual Meaning: Motivation for the Rise of Discourse Markers/Pragmatic Elements. Edited by Giulio Scivoletto and Ryo Takamura. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Petré, Peter. 2020. How constructions are born. The role of patterns in the constructionalization of be going to INF. In Patterns in Language and Linguistics. Edited by Beatrix Busse and Ruth Möhlig-Falke. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 157–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pons Bordería, Salvador. 1998. Conexión y conectores: Estudio de su relación en el registro formal de la lengua. València: Publicacions de la Universitat de València. [Google Scholar]

- Pons Bordería, Salvador. 2016. Cómo dividir una conversación en actos y subactos. In Oralidad y análisis del discurso: Homenaje a Luis Cortés Rodríguez. Edited by Antonio Miguel Bañón Hernández, María del Mar Espejo Muriel, Bárbara Herrero Muñoz-Cobo and Juan Luis López Cruces. Almería: Universidad de Almería, pp. 545–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pons Bordería, Salvador. 2018. Introduction. New insights in Grammaticalization studies. In Beyond Grammaticalization and Discourse Markers. New Issues in the Study of Language Change. Edited by Salvador Pons Bordería and Óscar Loureda Lamas. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pons Bordería, Salvador. 2022. Creación y análisis de corpus orales: Saberes prácticos y reflexiones teóricas (Sprache-Gesellschaft-Geschichte). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Pons Bordería, Salvador. 2023. Corpus Val.Es.Co. 3.0. Available online: http://www.valesco.es (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Pons Bordería, Salvador, and Kerstin Fischer. 2021. Using discourse segmentation to account for the polyfunctionality of discourse markers: The case of well. Journal of Pragmatics 173: 101–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh Jiménez, Shima. 2020a. ¿Por qué el español peninsular no reformula con digamos? Una reflexión sincrónica y diacrónica a partir de su comparación con el portugués europeo. In Marcadores discursivos. O português como referência contrastiva. Edited by Isabel Duarte and Rogelio Ponce de Leon. Theorie und Vermittlung der Sprache. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, vol. 63, pp. 312–41. [Google Scholar]

- Salameh Jiménez, Shima. 2020b. Pues eso como construcción interactiva desde el modelo Val.Es.Co. Zeitschrift für Katalanistik 33: 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh Jiménez, Shima. Forthcoming(a). The consolidation of the ‘pues’-based constructional network in Peninsular Spanish during the 20th century.

- Salameh Jiménez, Shima. Forthcoming(b). The study of colloquialization through the VAM units: A visual approach to football broadcastings.

- Scivoletto, Giulio. 2023. Il siciliano bì e l’espressione della miratività. Cuadernos de Filología Italiana 30: 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetser, Eve E. 1988. Grammaticalization and semantic bleaching. Paper presented at the Fourteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Berkeley, CA, USA, February 14–15; vol. 14, pp. 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 1982. From Propositional to Textual and Expressive Meanings: Some Semantic-Pragmatic Aspects of Grammaticalization. In Perspectives on Historical Linguistics. Edited by Winfred P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins, pp. 245–71. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 1995. The role of the development of discourse markers in a theory of grammaticalization. Paper presented at the Twelfth International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Manchester, UK, August 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 2010. (Inter)subjectivity and (inter)subjectification: A Reassessment. In Subjectification, Intersubjectification and Grammaticalization. Edited by Kristin Davidse, Lieven Vandelanotte and Hubert Cuyckens. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 29–74. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 2015. Toward a coherent account of grammatical constructionalization. In Diachronic Construction Grammar. Edited by Jóhanna Barðdal, Elena Smirnova, Lotte Sommerer and Spike Gildea. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 2020. Constructional pattern-development in language change. In Patterns in Language and Linguistics. Edited by Beatrix Busse and Ruth Möhlig-Falke. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 125–56. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 2022. Discourse Structuring Markers in English. A Historical Constructionalist Perspective on Pragmatics. Constructional Approaches to Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs, and Bernd Heine. 1991. Approaches to Grammaticalization. Theoretical and Methodological Issues. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs, and Graeme Trousdale. 2013. Constructionalization and Constructional Changes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs, and Richard B. Dasher. 2002. Regularity in Semantic Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trousdale, Graeme. 2014. On the relationship between grammaticalization and constructionalization. Folia Linguistica 48: 557–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val.Es.Co. Group. 2002. Corpus de Conversaciones Coloquiales. Madrid: Arco Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Val.Es.Co. Group. 2014. Las unidades del discurso oral. La propuesta Val.Es.Co. de segmentación de la conversación coloquial. Estudios de lingüística del español 35: 13–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, Jing-Schmidt, and Xinjia Peng. 2016. The emergence of disjunction: A history of constructionalization in Chinese. Cognitive Linguistics 27: 101–36. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).