Attention will be turned now to grammatical features of Spanish varieties spoken in Castile-La Mancha in order to test and complete these initial considerations on the phonetics of the region. Again, there will be two main guidelines through the following description: the presence of specific regional features of significant extension and the existence of internal boundaries corresponding (or not) to those just found for phonetic features.

The available literature on Spanish in Castile-La Mancha lists some relevant traits regarding syntax and morphology but, contrary to phonetical descriptions, they have not been examined in detail. As mentioned before, there is of course a variable of crucial importance in Peninsular Spanish, third-person clitic pronouns, which is clearly relevant in the region (

Moreno Fernández 1996, p. 225;

González Pérez 2016, pp. 225–26). Another significant variable in Castile-La Mancha is the presence of a prepositional complementiser

de in subordinate clauses that result in the so-called

deísmo (and

dequeísmo) structures (

Camus 2013;

de Benito and Pato 2015).

There are also important syntactic variables that are not well-represented in Castile-La Mancha Spanish. One of them is the transitive/causative use of verbs such as

caer ‘to fall’ or

quedar ‘to stay’, a western feature that can be found from León, in the north, to Andalusia (

Jiménez-Fernández and Tubino-Blanco 2019;

Camus and Gutiérrez Rodríguez 2021, p. 165). In ALeCMan, however, this use is only documented in some places of the far west of Toledo or Ciudad Real (

García Mouton and Moreno Fernández 2003, map SIN-73

quedar (dejar) la cartera). On the other hand, the transitive use of

entrar ‘to go in’ is, as in most of western and southern sub-standard Spanish, well attested in the west, centre and south areas of Castile-La Mancha (

García Mouton and Moreno Fernández 2003, map SIN-71

entrar (meter) la leña):

| (8) | a. | Cuidado, | no | caigas | el vaso. | (non-standard) |

| | | Attention | NEG | fall 2SING IMP | the glass | | |

| | | ‘Pay attention, do not let the glass fall’. | |

| | b. | Puedes | quedar | el libro | ahí mismo. | (non-standard) |

| | | can 2PRE | stay INF | the book | over there | | |

| | | ‘You can leave the book over there’. | |

| | c. | Entra | el coche | en el garaje. | | (non-standard) |

| | | Go in 2SING IMP | the car | in the garage | | | |

| | | ‘Get the car in the garage’ | |

Finally, most of the recorded features in inflectional morphology are confined to scattered, isolated areas or scarcely documented. This is the case for some of the alleged archaisms in verbal forms such as non-standard second and third conjugation imperfects in -

iba (

traíba vs.

traía2), conditionals and imperfects in -

íe in the south-eastern Toledo province and second-person plural imperatives in -

ái,

éi:

jugái,

hacéi vs.

cantad,

haced…3 (

Moreno Fernández 1996, p. 224;

Álvarez Rodríguez 1999, p. 34;

Pato 2018). Nevertheless, not all morphological features in Castile-La Mancha are of such a limited extension. The deviant desinences of second-person plural (

entreguéis,

cogís instead of

entregais,

cogís …4) that are found in eastern and central areas, in La Mancha, are a good example of innovative morphology. They deserve further attention and will be described in detail later in this work.

As has been claimed, most of the aforementioned grammatical features do not seem to be useful to establish significant external boundaries and internal divisions of geographical nature within Castile-La Mancha. We have just seen that they are shared with the rest of spoken Peninsular Spanish or are not sufficiently widespread in the territory. But there are at least three grammatical traits that can be identified for that purpose: They either correspond to important variables that define Peninsular Spanish (clitic pronoun systems), partially define Southern Peninsular Spanish grammar (syntax of complementation) or can be considered as specific regional features due to their considerable extension in all the five provinces of the community (reduced forms of second plural verb desinences). The following discussion will be dedicated to the description of these three traits.

3.2.1. Referential System of Clitic Pronouns in Castile-La Mancha

Spanish, like the rest of the Romance languages, has a system of unstressed or clitic pronouns that are co-referent with direct or accusative complements or indirect or dative complements. The third-person forms are inherited from the Latin

ille and marked distinctively for case, gender and number. This close relation to Latin forms justifies the usual denomination of this paradigm as an etymological system of third-person clitic pronouns, and is shown in

Table 1 below with its relevant features and forms:

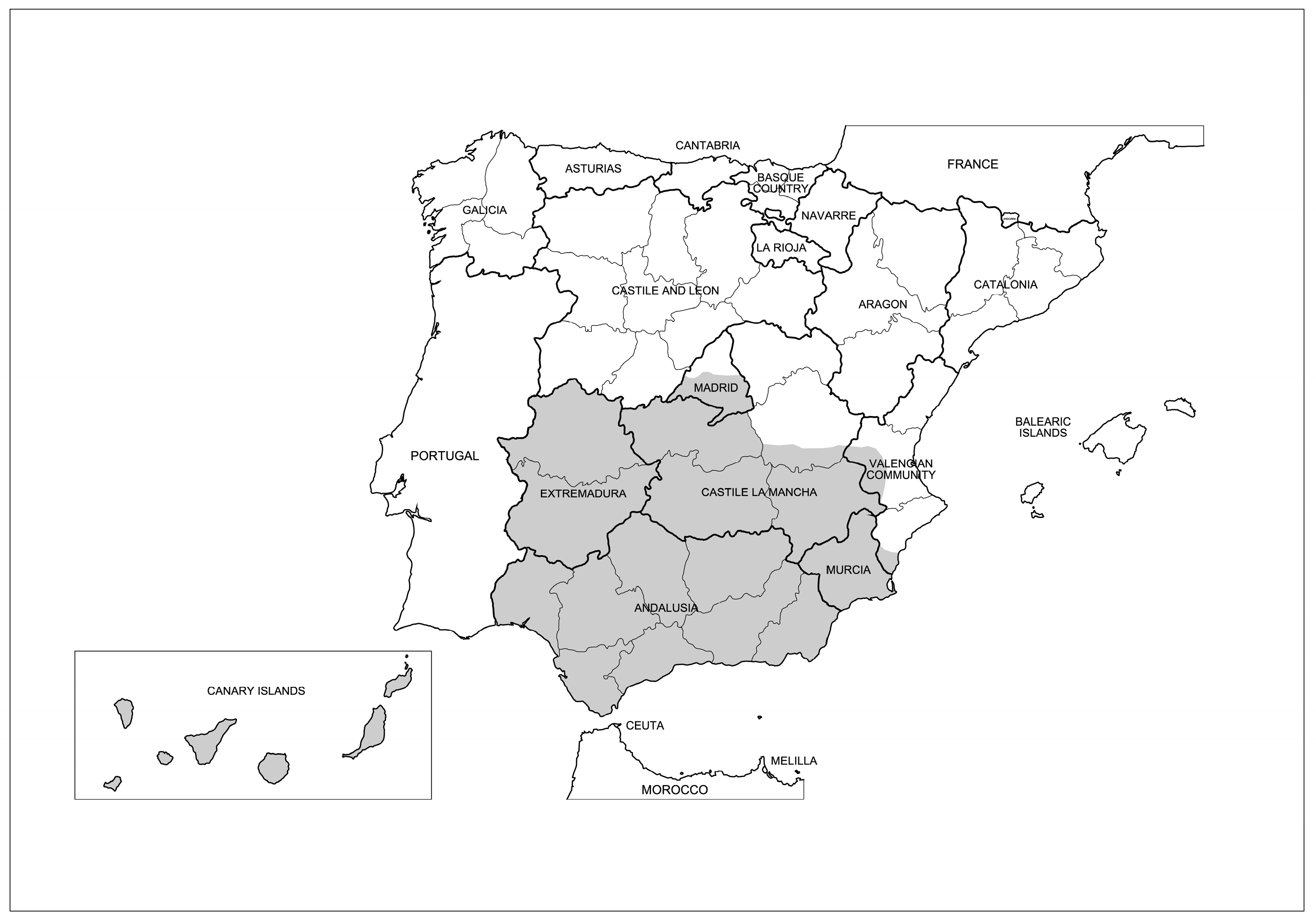

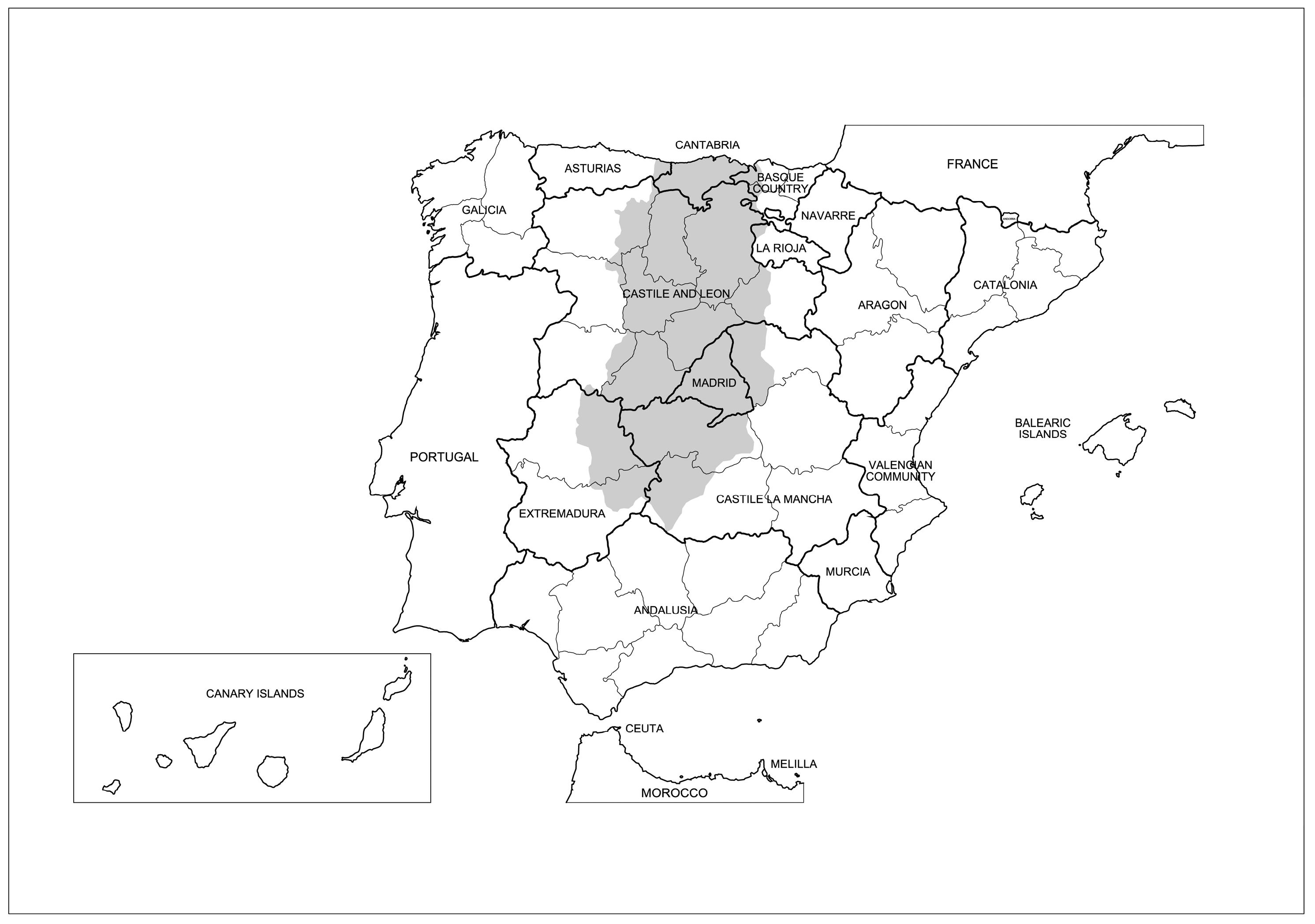

This etymological system is present throughout all the Spanish-speaking areas. It is practically the only one in America, save for some contact areas in the Andes and Paraguay. And it is also the most extended in Spain, where it is predominant in the Canary Islands, Southern Peninsular Spanish and in western and eastern areas of Northern Peninsular Spanish (see the blank spaces in

Figure 2 above). The examples in 9–10 serve as an illustration of its actual use in these areas:

| (9) | a. | A Juani, | loi | vi | ayer |

| | | To Juan | 3rd SING ACC MASC | see1st SING PERF | yesterday |

| | | ‘Talking about John, I saw him yesterday’ |

| | b. | A Maríai, | lai | vi | ayer |

| | | To María | 3rd SING ACC FEM | see1st SING PERF | yesterday |

| | | ‘Talking about Mary, I saw her yesterday’ |

| | c. | A Juan y Pedroi, | losi | vi | ayer |

| | | To Juan and Pedro | 3rd PL ACC MASC | see1st SING PERF | yesterday |

| | | ‘Talking about John and Peter, I saw them yesterday’ |

| | d. | A María y Anai, | las | vi | ayer |

| | | To María and Ana | 3rd PL ACC FEM | see1st SING PERF | a present |

| | | ‘Talking about Mary and Ann, I saw them yesterday’ |

| (10) | a. | A Juan/Maríai, | lei | di | un regalo |

| | | To Juan/María | 3rd SING DAT | give1st SING PERF | a present |

| | | ‘Talking about John/Mary, I gave him/her a present’ |

| | b. | A Juan y Maríai, | lesi | di | un regalo |

| | | To Juan and María | 3rd PL DAT | give1st SING PERF | a present |

| | | ‘Talking about John and Mary, I gave them a present’ |

In Castile-La Mancha, where Southern Peninsular Spanish is predominant, this etymological system is the most extended one and is found in Ciudad Real and the easternmost provinces of Guadalajara, Cuenca and Albacete. This said, there exists a vast area where this system is not present and, instead, the use of third-person clitic pronouns corresponds to the innovative referential system, the same that is found in the Northern Peninsular Spanish spoken in the central strip that goes from Cantabria in the north to Toledo in the south (see

Figure 2). This innovative referential third-person clitic pronoun system differs from the etymological system inherited from Latin mainly because it does not maintain the original case distinctions and generalises gender—or referential—differences. In

Table 2, a simplified version of this system is represented

5.

As

Table 2 shows, in some of these “referential” varieties, the use of the original dative clitic pronoun has been extended to cover the reference to accusative masculine in singular and plural (

leísmo). In other cases, as will be seen,

los becomes the clitic pronoun for dative plural masculine nouns, thus giving way to the so-called

loísmo (example 13b) below). And in yet another variety, the original accusative feminine pronoun has extended to cover feminine singular and plural references both in accusative and dative (

laísmo). The following sentences in (11) and (12) exemplify these uses of clitic pronouns in the referential system, with or without

loísmo:

| (11) | a. | A Juani, | lei | vi | ayer | (leísmo) |

| | | To Juan | 3rd SING ACC MASC | see1st SING PERF | yesterday | |

| | | ‘Talking about John, I saw him yesterday’ | |

| | b. | A Maríai, | lai | vi | ayer | |

| | | To María | 3rd SING ACC FEM | see1st SING PERF | yesterday | |

| | | ‘Talking about Mary, I saw her yesterday’ | |

| | c. | A Juan y Pedroi, | lesi/losi | vi | ayer | (leísmo if les is selected) |

| | | To Juan and Pedro | 3rd PL ACC MASC | see1st SING PERF | yesterday | |

| | | ‘Talking about John and Peter, I saw them yesterday’ | |

| | d. | A María y Anai, | lasi | vi | ayer | |

| | | To María and Ana | 3rd PL ACC FEM | see1st SING PERF | yesterday | |

| | | ‘Talking about Mary and Ann, I saw them yesterday’ | |

| (12) | a. | A Juani, | lei | di | un regalo | |

| | | To Juan | 3rd SING DAT MASC | give1st SING PERF | a present | |

| | | ‘Talking about John, I gave him a present’ | |

| | b. | A Maríai, | lai | di | un regalo | (laísmo) |

| | | To María | 3rd SING DAT FEM | give1st SING PERF | a present | |

| | | ‘Talking about Mary, I gave her a present’ | | |

| | c. | A Juan y Pedroi, | lesi/losi | di | un regalo | (loísmo if los is selected) |

| | | To Juan and Pedro | 3rd PL DAT MASC | give1st SING PERF | a present | |

| | | ‘Talking about John and Peter, I gave them a present’ | |

| | d. | A María y Anai, | lasi | di | un regalo | (laísmo) |

| | | To María and Ana | 3rd PL DAT FEM | give1st SING PERF | a present | |

| | | ‘Talking about Mary and Ann, I gave them a present’ | |

The referential system found in Castile-La Mancha usually includes—together with

leísmo and

laísmo—the selection of the pronoun

los instead of

les as accusative/dative plural with masculine reference (see

Table 2 above), as these sentences from the COSER survey at the village of Pulgar in Toledo testify:

| (13) | a. | Ahora | no | los [los cerdos] | matan | así | (COSER, Pulgar, TO, p. 4) |

| | | Now | NEG | 3rd PL ACC MASC | kill3rd PL PRES | that way | |

| | | ‘They don’t kill them [the pigs] that way now’ | |

| | b. | Los [los novios] | quitemos | toda la ropa | (COSER, Pulgar, TO, p. 15) |

| | | 3rd PL Dat MASC | take away1st PL PERF | all the c`lothes | |

| | | ‘We took away all their [the newlyweds’] clothes’ | |

The following

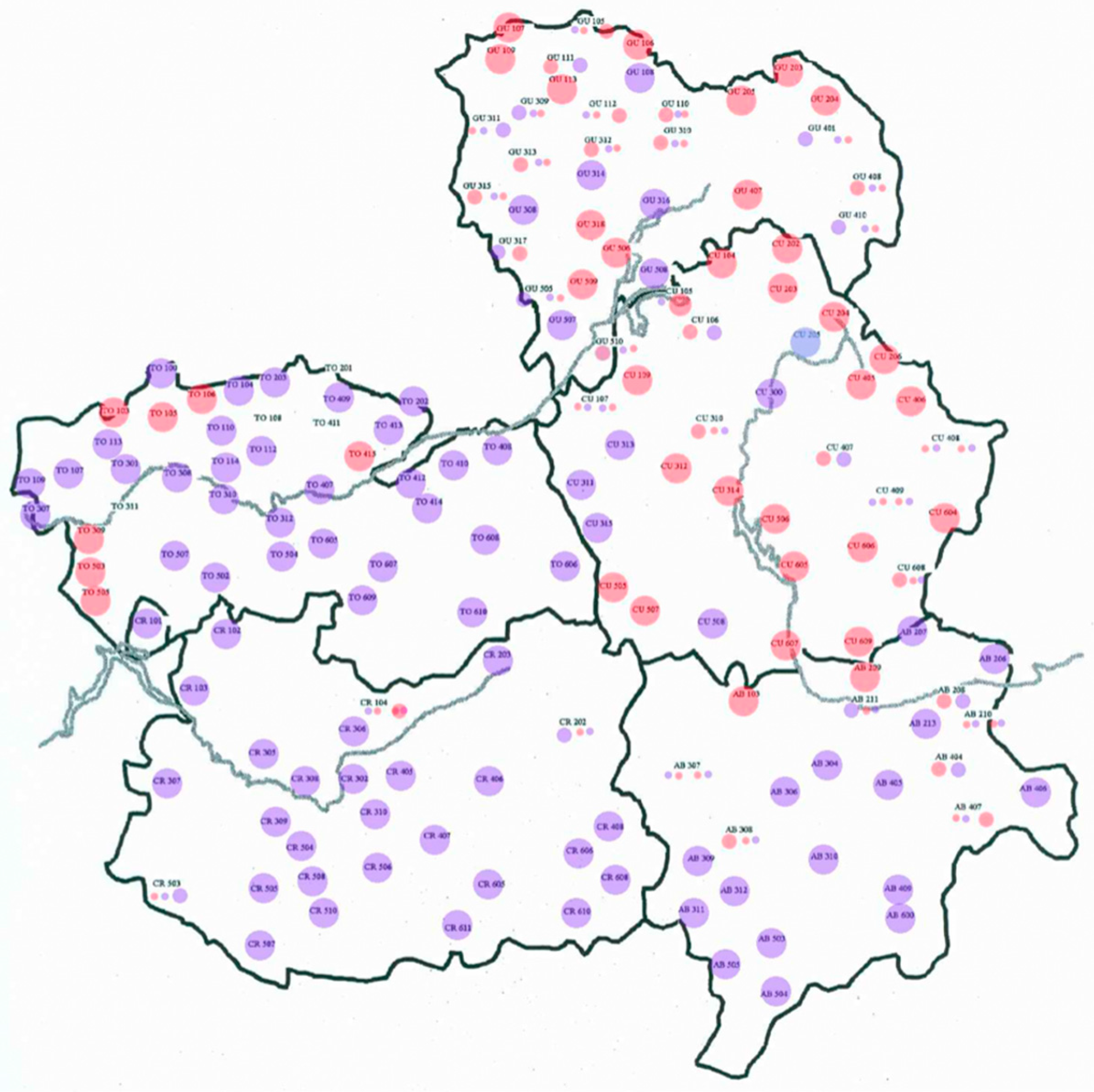

Figure 7 represents the extension of

leísmo in ALeCMan. It refers to its use in a sentence where the clitic pronoun has human masculine reference, which is the most widespread variant of

leísmo:

As shown in

Figure 7, this maximum extension of

leísmo covers most of the Toledo province, western Guadalajara and some north-western areas in Ciudad Real. It is important to mention that this human reference

leísmo is part of Standard Spanish and ‘prestigious’ Madrid Spanish (

Fernández-Ordóñez 1999, pp. 1386–90). Thus, the pressure exerted on Castile-La Mancha’s formal speech could account for this greater diffusion (

García Mouton 2011, p. 83).

Precisely because of this, we would expect

laísmo, not part of Standard Spanish, to be less widespread in the area. This is indeed the case, as

Figure 8 demonstrates:

However, both

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 clearly draw a north-western area in Castile-La Mancha whose syntax includes northern pronominal innovations. It could be described as a kind of linguistic wedge that crosses the Central Range through the mountain passes of Gredos and Guadarrama in Ávila and Segovia and breaks into Madrid and Toledo in the southern Spanish plateau. It is another of the relevant internal divisions inside Castile-La Mancha, but one of a really different nature to those previously considered. It corresponds to an innovation that arrived from the north that leaves in the south another large area of conservative syntax that partly coincides with the area of innovative phonetics.

To resume and complete the description of the presence of the referential system in Castile-La Mancha beyond this preliminary consideration on

leísmo of human reference and

laísmo, we should note that

leísmo in the oral varieties of this north-western corner of the region always includes the reference to all count names, both animate and inanimate, as was represented by the canonical display of referential system in

Table 2. But the coincidence with the pronoun systems that are found in the north-central strip of

Figure 2 does not finish here. The varieties spoken in those north-western areas present another notorious feature, the existence of a specific set of pronouns to refer to non-count nouns (

Fernández-Ordóñez 1999, pp. 1360–63), as can be seen in

Table 3.

Some examples from the COSER surveys in central Toledo province serve as an illustration of this use of the form

lo as the pronoun to refer to non-count nouns:

| (14) | a. | La sangrei, | loi | cogían | las mujeres | (COSER, Pulgar, TO, p. 2) |

| | | The bloodFEM | 3rd SING ACC | collect3rd PL IMPERF | the women | |

| | | ‘As for the the blood, the women collected it’ | |

| | b. | El caldoi, | loi | movían… | | (COSER, Pulgar, TO, p. 3) |

| | | The brothMASC | 3rd SING ACC | stir3d PL IMPERF | | |

| | | ‘As for the broth, they stirred it…’ | |

| | c. | Loi | llaman | leche Pascuali | | (COSER, Pulgar, TO, p. 8) |

| | | 3rd SING DAT | call3rd PL PRES | milk PascualMASC | | |

| | | ‘They call it milk Pascual (a trademark)’ | |

This kind of pronominal agreement for count and non-count nouns is shared by all the territory where the referential system is found in Spain, the shaded area of

Figure 2. The village of Pulgar in Toledo province, the provider of examples (13) and (14), is located in that area, near the border with the southern province of Ciudad Real.

3.2.2. Complementisers and Deísmo in Castile-La Mancha

The syntax of many varieties of spoken and rural/sub-standard Spanish in Castile-La Mancha incorporates a feature that is worth describing and mapping. This feature is the so-called

deísmo, the insertion of the preposition

de in infinitive sentences that was already presented in

Section 1 with example (2). This example is again repeated below (15a) together with two more sentences with this construction:

| (15) | a. | Me | hacen | de | reír | (with causative verb) |

| | | 1st SING ACC | make3rd PL PRES | of | laughINF | |

| | | ‘They make me laugh’ | |

| | b. | Me | sintieron | de | venir | (with perception verb) |

| | | 1st SING ACC | hear3rd PL PERF | of | comeINF | |

| | | ‘They heared me come’ | |

| | c. | Intentó | de | disparar | (with control verb) |

| | | try3rd SING PERF | of | shootINF | |

| | | ‘He tried to shoot’ | |

As these sentences show, this non-standard

de can precede different types of infinitive clauses. It is really common in causative clauses or with perception verbs (15a-b), but its original locus corresponds to typical infinitives controlled either by subjects, as the one in (15c), or by complements (

Camus 2013, pp. 22–28). This latter context seems to correspond to the same construction of control verbs with

de that is sometimes documented in Medieval Spanish and can still be regularly found in French, Italian or Catalan, where it is part of the standard variety (

Camus and Gómez Seibane 2015). The construction in sub-standard Spanish is, thus, a continuation of this usage that was already present in the Middle Ages but has been lost in Standard Modern Spanish. It has, however, continued to live in some dialects (15c). Even more, in most of these dialects, the construction would have been extended in recent centuries to other contexts such as those with causative or perception verbs (15a,b).

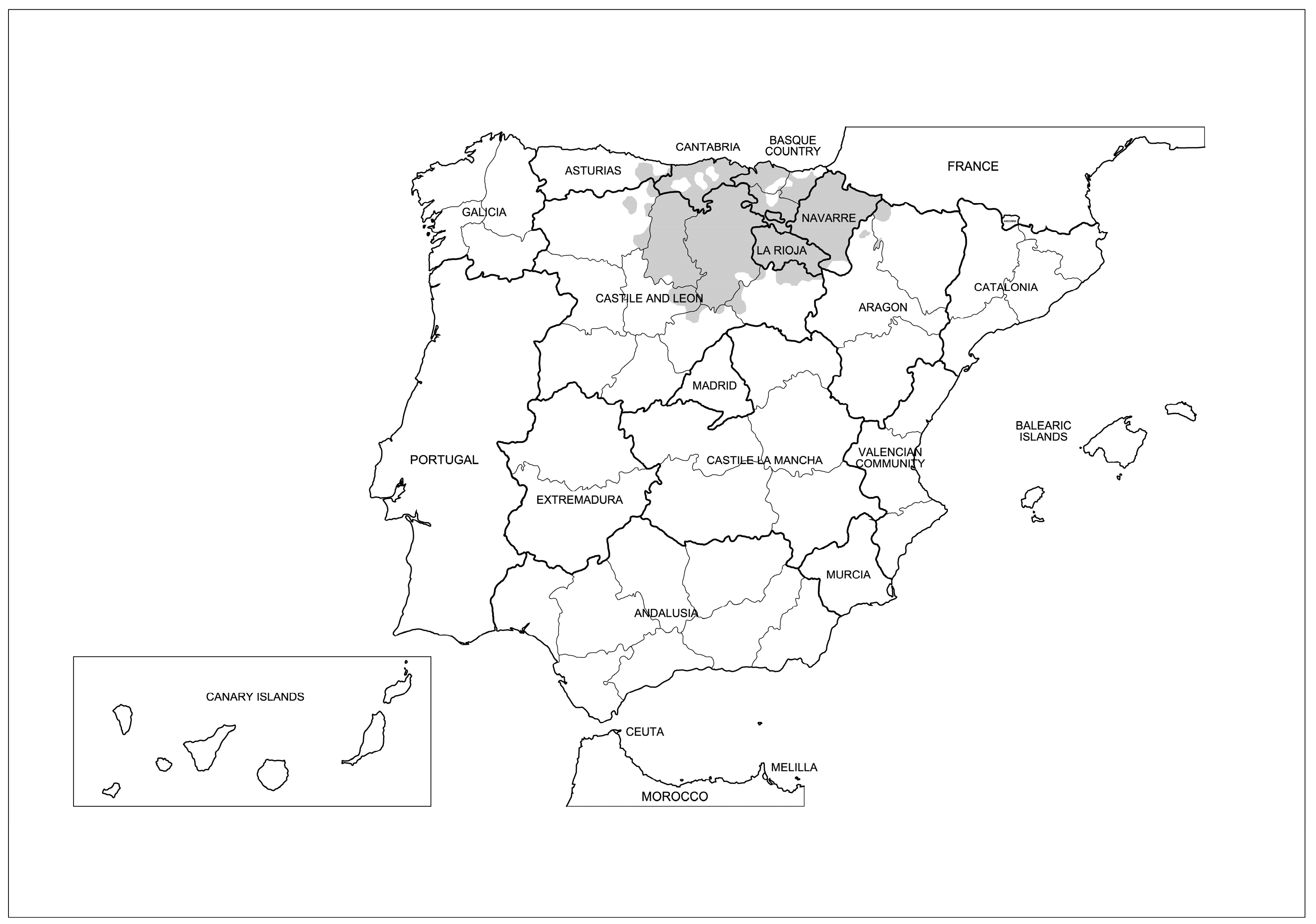

As

Figure 9 shows, the type of

deísmo most extended in the region corresponds to infinitive clauses with causative verbs (

hacer de reír: blue dots), which is present even in the mountainous and isolated east areas of Guadalajara and Cuenca provinces. But, save for this case,

deísmo is only common in the Toledo and Ciudad Real provinces, south-western Guadalajara and the western half of Cuenca. In the southwestern province of Albacete, however, it is rare and can be exceptionally found in some southwestern villages.

Data from COSER seem to show similar results, except for the fact that there are some more examples of

deísmo from all throughout Albacete (

de Benito and Pato 2015, p. 33). However, it should be noted that these and other examples from Guadalajara and Cuenca in COSER are mostly limited to infinitive clauses with control verbs (specially

gustar ‘to like’). Considering data from both sources,

deísmo should be described as a common feature of the Spanish varieties of Castile-La Mancha with a stronger foothold in western and central areas.

And it is worth mentioning that

deísmo is also a common feature of other southern Peninsular dialects. Following

de Benito and Pato (

2015, pp. 33–34) and their account of COSER data, examples with

de in front of infinitive sentences are regularly found in Andalusia, Extremadura and Murcia, in addition to in Castile-La Mancha. They have also been exceptionally documented in Northern Spain, where this old construction seems to have almost disappeared.

3.2.3. Reduced Variants of Second-Person Plural Desinences

With this simplified label, we will refer to the preference shown by different varieties of Peninsular Spanish for innovative forms of this desinence. Forms of second-person plural have been generally studied in relation to the types of

voseo morphology in America that become an alternative to the original second singular desinences corresponding to the second singular pronoun

tú (

Real Academia Española and Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española 2009, §§ 4.4d and 4.7). As opposed to these, the Peninsular Spanish non-standard desinences are still desinences of the second plural original pronoun

vosotros and differ substantially from most American

voseo variants, and therefore can be easily recognisable. Curiously enough, they have received little attention in the current literature (

Hernando Cuadrado 2009, p. 175), and the reference grammar does not even mention them (see

Alcoba 1999, pp. 4924–26;

Real Academia Española and Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española 2009, §4.4). Some of these alternative desinences, for both present indicative and present subjunctive of verbs

entregar ‘to deliver’,

querer ‘to want’ and

salir ‘to go out’, are listed in

Table 4 below:

6,

7As can be seen, new forms in this

Table 4 show some kind of phonetic reduction and tend to simplify the variation in this second-person plural morphology to only two possibilities (-

éis and -

ís) in the most frequent paradigm or just one (-

ís) when even the specific desinence for verbs in -

ar suffers an extreme phonetic reduction.

These new present desinences are actually also found in other tenses, such as imperfect indicative (although only in second and third conjugation verbs), conditional and future:

In these latter tenses in

Table 5, desinences are derived from a second conjugation verb (

haber) in the imperfect and present tense, respectively. That explains the coincidence of conditional desinences with the imperfect ones and the one between future desinences and those of the second conjugation verbs in the present indicative (see

Table 4). This coincidence allows us to limit the attention from now on to just the reduced desinences of present tenses in

Table 4, and particularly to the better-documented reductions, that is, the new forms in -

ís that come from -

éis, corresponding either to present indicative of second conjugation verbs in -

er or present subjunctive of first conjugation verbs in -

ar.

Data from old surveys of ALPI already showed the diffusion of these forms in -

ís (

querís < queréis), mainly in eastern areas of the Peninsula. The forms were found in all three provinces of Aragon except for central and northern Huesca. It was also frequent to find them in the neighbouring Castilian province of Soria and eastern Cantabria, to the north. And they were also very common in Castile-La Mancha, with the only exception of the province of Toledo.

8 Regional Spanish atlases developed in the second half of the 20th century broadly confirm this distribution. Almost every form in

Table 4 and

Table 5 above can be found in those surveys, mainly in Aragon and Cantabria (

Alvar et al. 1979–1983;

Alvar 1995, respectively) but also in eastern Andalusia (

Alvar et al. 1961–1973). The corresponding maps confirm an eastern distribution of this change in second-person plural desinences in Peninsular Spanish that more recent data from COSER corroborate with actual informal spoken records (

Fernández-Ordóñez (dir.) 2005-). Examples like

conocís (<

conocéis ‘you know’),

entendís (<

entendéis ‘you understand’),

habís (<

habéis ‘you have’),

querís (<

queréis ‘you want’),

sabís (sabéis ‘you know’),

tenís (<tenéis ‘you have’)… are found in the COSER online files. They come from Aragon, eastern Cantabria, Soria and Jaén, the same places where they had been previously documented. But they also come in large numbers from Castile-La Mancha (mostly from locations in Guadalajara, Cuenca, Albacete and Ciudad Real, but also from eastern Toledo).

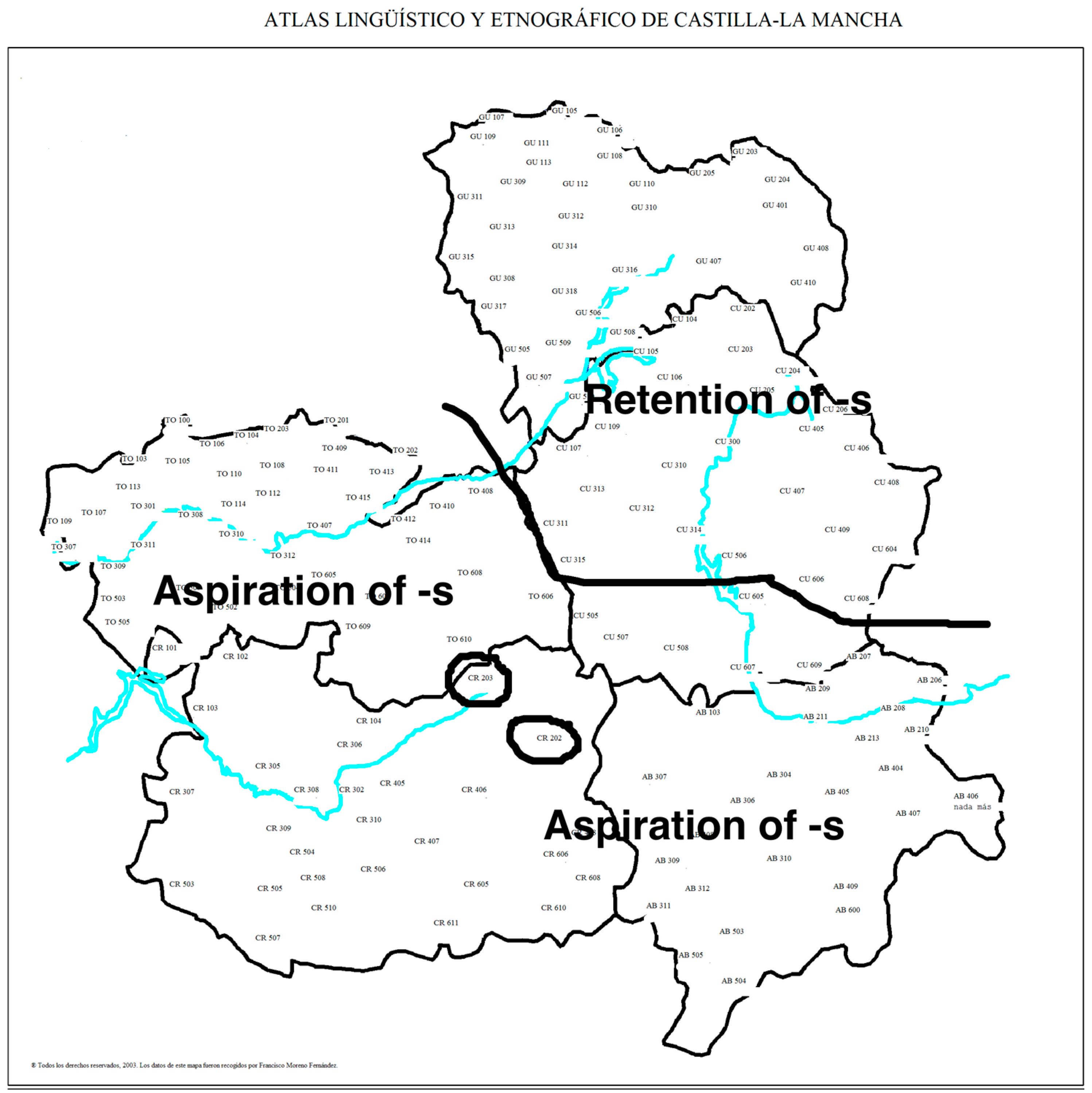

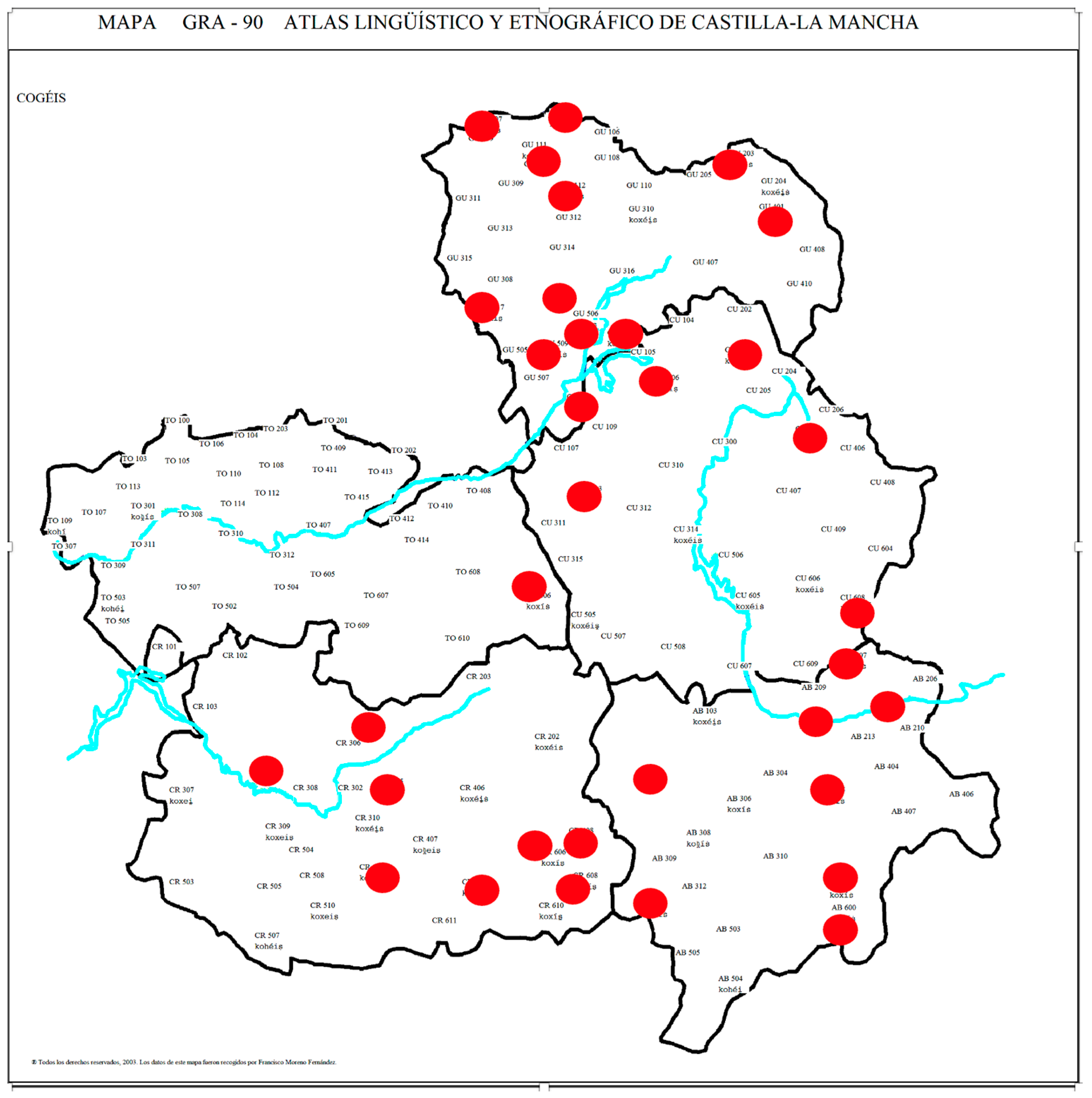

Data of

Figure 10 refer to the most common reduced variant of second-person plural forms of the present indicative of verbs in -

er (

coger ‘to take’:

cogéis >

cogís). Other questions in ALeCMan regarding these forms receive few answers and therefore are less representative, unless they show an identical distributional pattern. As

Figure 10 shows,

cogís—and other similar reduced forms—is present everywhere in the three eastern provinces of Guadalajara, Cuenca and Albacete and in Ciudad Real. In Toledo, these forms are not completely unknown, and they can sometimes be found in eastern areas, such as Quintanar de la Orden (point of survey code TO-606), a place belonging to the natural region of La Mancha, as shown in

Figure 10.

This distributional pattern draws a new linguistic space within Castile-La Mancha that covers northern, eastern and southern mountainous borders and the great central plain of La Mancha. This might be explained by the fact that this vast area has been open to changes coming from the northeast (Soria) and east (Aragon). This kind of influence is of a very different nature to the one seen in

Section 3.2.1, which explains the referential clitic system in the north-western corner of the region. The distribution across this large eastern area has to do again with medieval repopulation, but also with enduring contact through tracks of annual cattle migrations across the mountains of the Central Range to the plains of La Mancha. It is probably part of a well-known lexical area shared by Aragon and eastern Old Castile, eastern Castile-La Mancha, eastern Andalusia and Murcia (

Catalán [1975] 1989). In fact, it cannot be a surprise that this common linguistic space also emerges when dealing with inventories, even if they are of a morphological nature, such as inflectional desinences.

To summarise, the detailed attention to grammatical features of Castile-La Mancha Spanish varieties has revealed new internal divisions that do not coincide with the boundaries traditionally defined by the phonetical features considered in the previous subsection. The heterogeneous configuration of grammar-based limits in this community overthrows the reducing idea of a transitional dialect in Castile-La Mancha. These limits draw new linguistic spaces, exposing the need for new proposals that account for the Spanish spoken in this region and a closer examination of past definitions.