1. Introduction

Speech accommodation, which refers to altering one’s speech in response to an interlocutor (

Giles et al. 1991;

Gallois et al. 2005;

Dragojevic et al. 2016), is a hallmark of human interaction.

Gasiorek et al. (

2015) assert that it is part of human nature, and

Britain and Trudgill (

2009) suggest that it occurs as a natural outcome of dialect contact between speakers of mutually intelligible varieties and becomes a driving force for language variation and change (

Pardo 2006;

Garrett and Johnson 2013). Speech accommodation has been examined and attested across different languages and in different contexts (

Giles et al. 2023). Such accommodation can be manifested as convergence, divergence, or maintenance whereby speakers may adapt their language use to the interlocutor, distance it from the interlocutor, or maintain their own speech patterns, respectively (

Giles et al. 1991;

Gallois et al. 2005;

Dragojevic et al. 2016;

Giles 2016). Speakers may accommodate to their interlocutors through a variety of linguistic features including lexical items, syntactic forms, or phonological variants, among others (

Giles et al. 1987,

1991). This would involve adaptation of familiar features over which speakers already have control when accommodation occurs within a speech community but would entail learning new forms in situations of new or unfamiliar varieties (

Trudgill 1986;

Dragojevic et al. 2016). As such, speakers’ linguistic knowledge and repertoires, which can be dependent on several factors including age, education, and exposure to certain linguistic features (

Andersen 1992), would play a key role in the degree and patterns of accommodation (

Dragojevic et al. 2016;

Gasiorek et al. 2022). Other factors are also projected to influence accommodation including similarities and/or differences between the varieties in contact (

Hernández 2002); underlying beliefs and attitudes towards both the interlocutor and the linguistic forms of choice in each interaction (

Giles et al. 1991;

Gasiorek and Giles 2012); identity perceptions (

Giles et al. 1991;

Miller 2005); and linguistic prestige (e.g.,

Miller 2005;

Giles and Ogay 2007;

Habib 2010). For example, when contact occurs between high prestige and low prestige varieties, speakers of stigmatized dialects may view convergence to the prestigious norms as a necessity for social mobility and integration (

Miller 2005;

Habib 2010). Likewise, speakers converge to individuals they respect and admire or to those they associate with a socially attractive group (

Giles et al. 1991;

Giles 2008,

2016). On the other hand, identity perceptions may prompt divergent behaviour whereby speakers accentuate their own speech forms to disassociate themselves from the interlocutor, which, in turn, would enhance their identity and their sense of self (

Giles et al. 1991;

Gasiorek 2016;

Zhang and Giles 2018). Convergence and divergence can also have long-lasting effects on speech communities, especially in situations of dialect contact. Long-term societal and personal convergence may contribute to language change (

Trudgill 1986;

Giles et al. 1991), while long-term intergroup divergence could contribute to language maintenance and survival (

Giles et al. 1991).

Auer and Hinskens (

2005, pp. 335–36) propose that for interpersonal accommodation to lead to language change, three hierarchically ordered components must be in place. The first relates to the ‘interactional’ episode whereby speakers may demonstrate short-term accommodation by converging to their interlocutor; either by adopting the interlocutor’s, usually innovative or prestigious, forms, or by abandoning their own, usually traditional, features. The second relates to the speaker who would demonstrate long-term accommodation by adopting such features in their own speech (i.e., outside of the interactional episode). The third component relates to the speech community at large whereby such innovations are spread into the community.

As such, while it can be argued that accommodative behaviour, especially phonetic convergence, maybe an automatic reflex (e.g.,

Goldinger 1998;

Delvaux and Soquet 2007), patterns of speech accommodation are impacted by a number of socio-cognitive factors including age, gender, linguistic knowledge, linguistic prestige, and linguistic attitudes (

Giles et al. 1991;

Dragojevic et al. 2016). Indeed,

Hinskens et al. (

2005) assert that accommodative acts are conscious choices of socially aware individuals.

6. Discussion

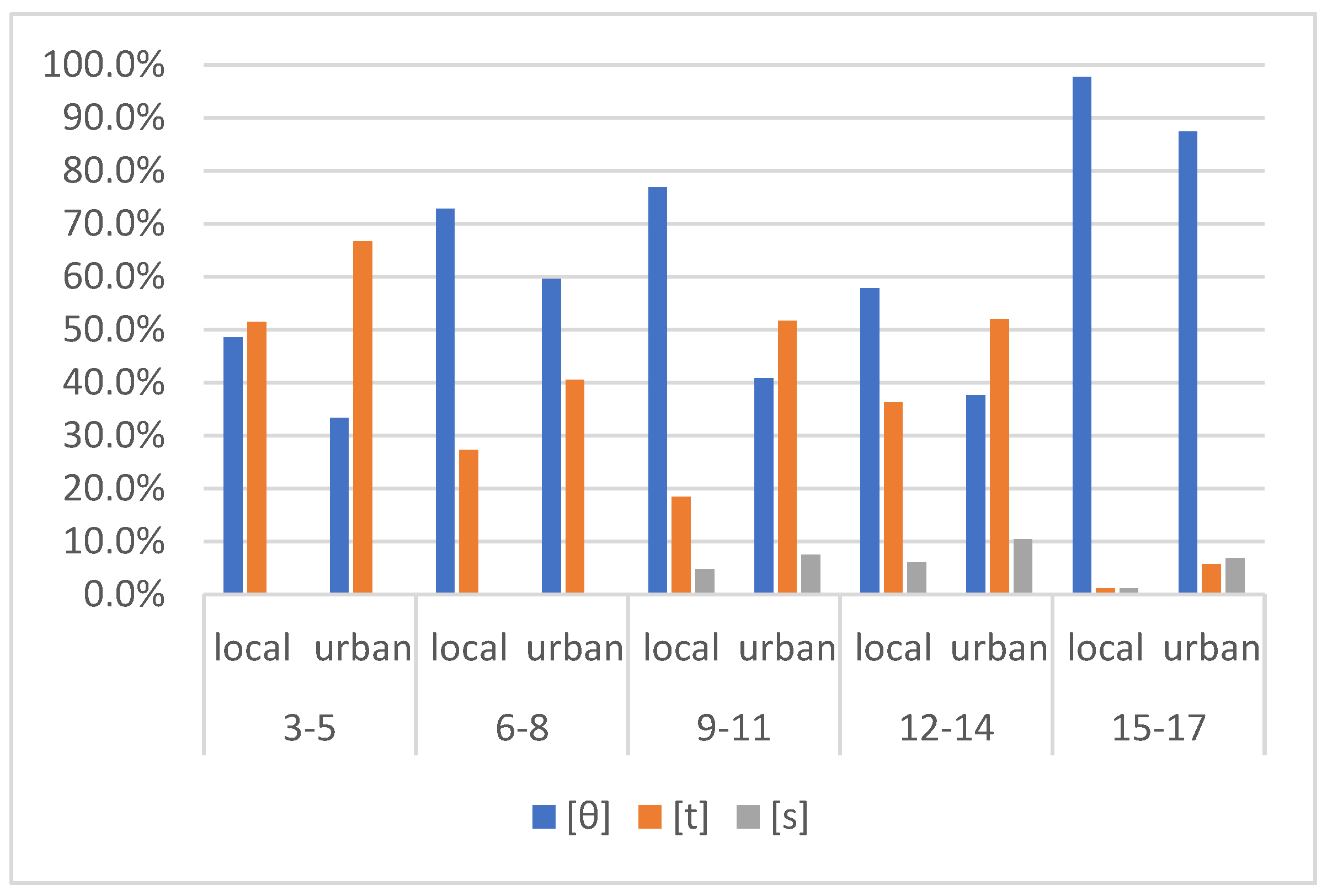

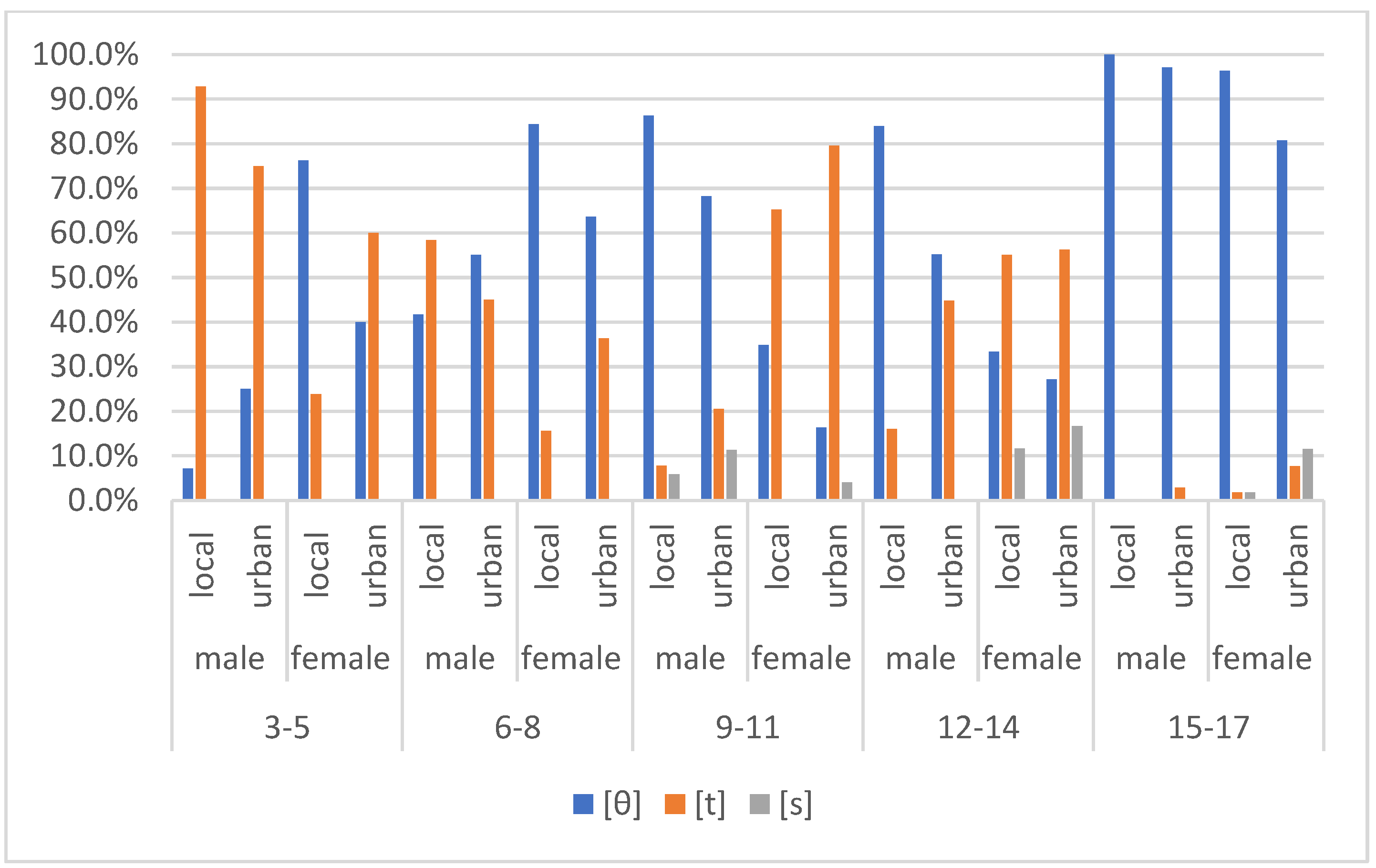

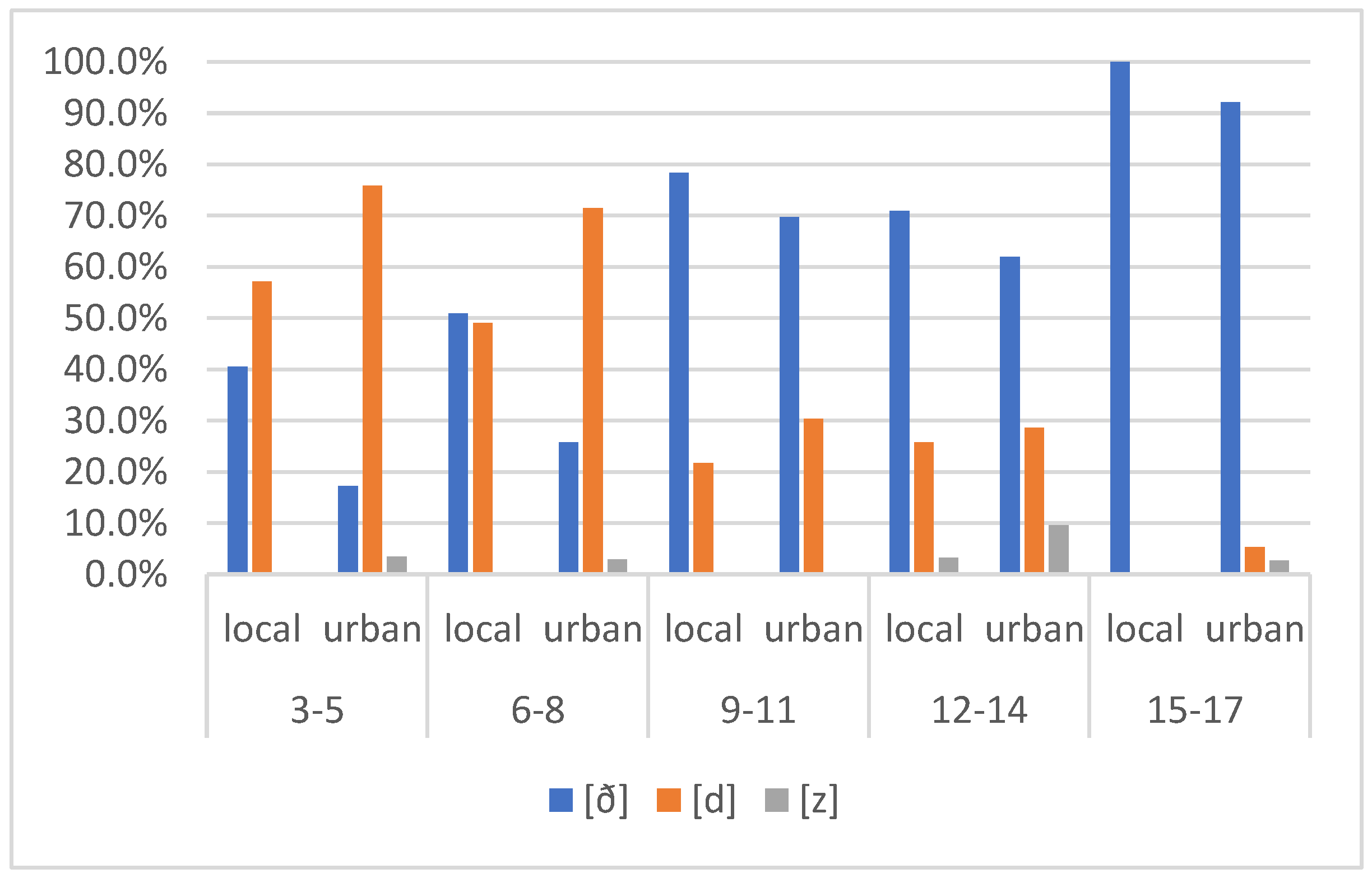

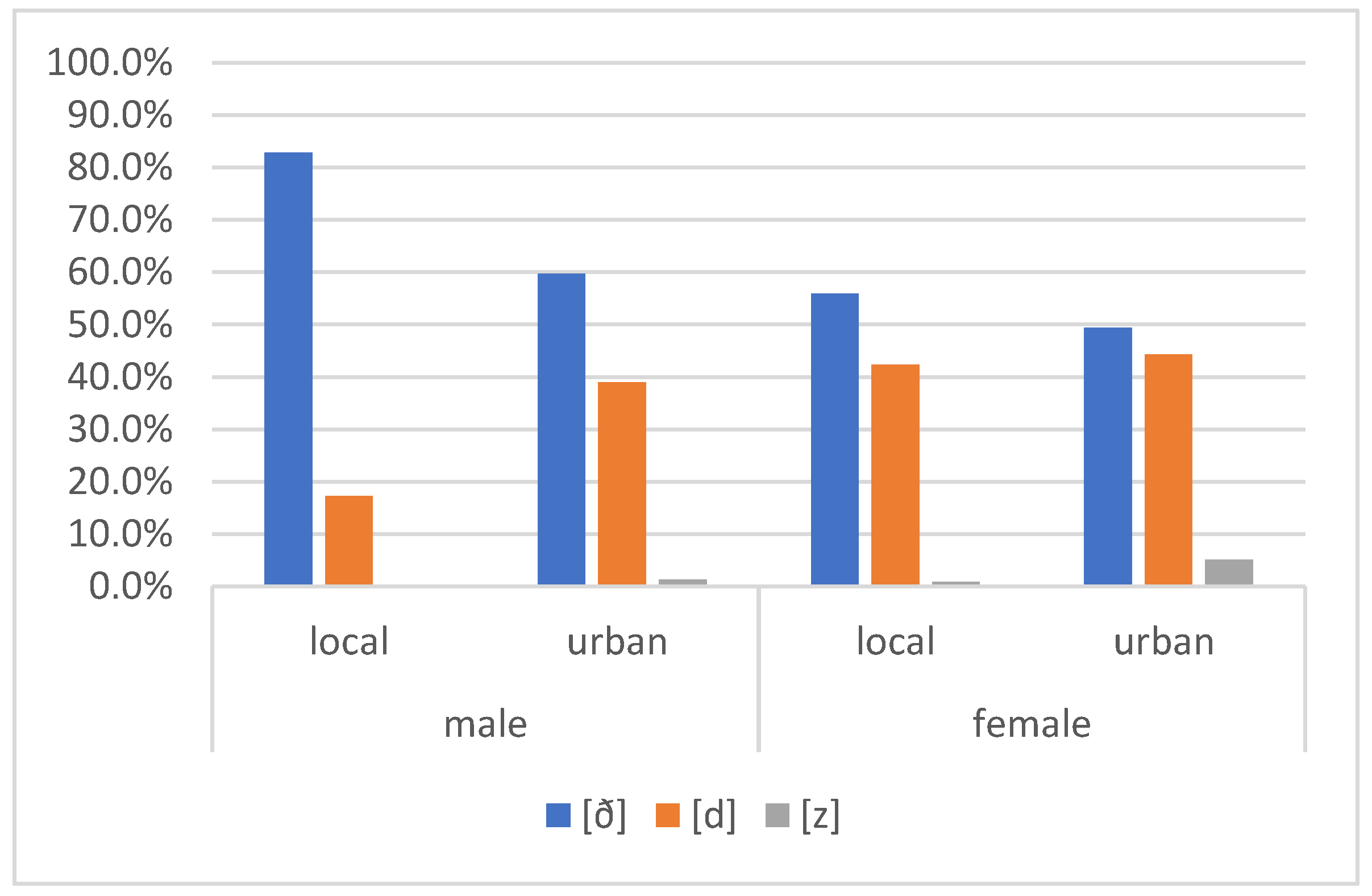

The results above reveal obvious patterns of linguistic accommodation in the speech of Arabic-speaking children and adolescents experiencing dialect contact. Accommodation patterns in the speech of participants were impacted by a number of factors including age, gender, and the linguistic features being accommodated, as revealed by the results and as will be detailed in this discussion.

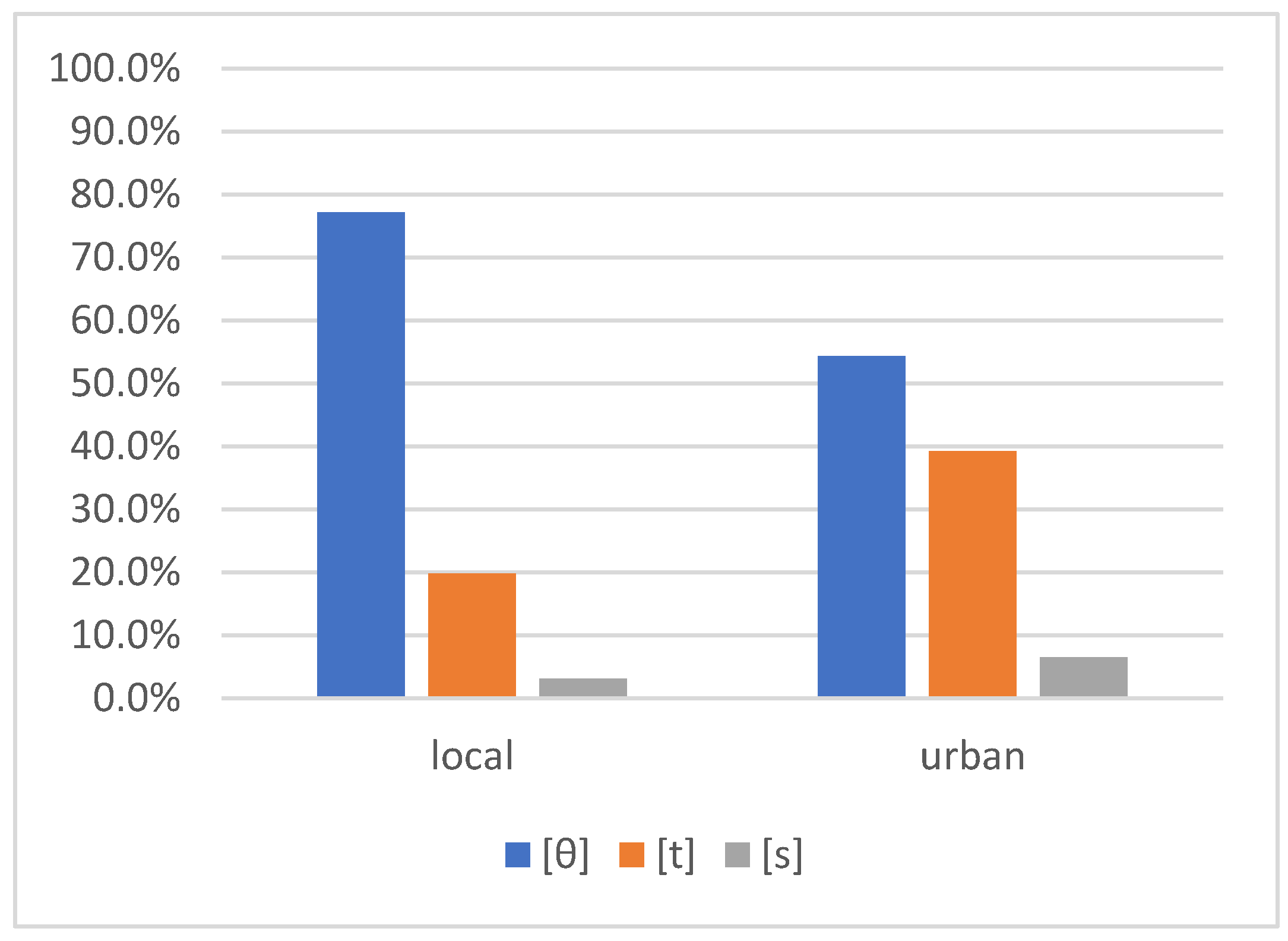

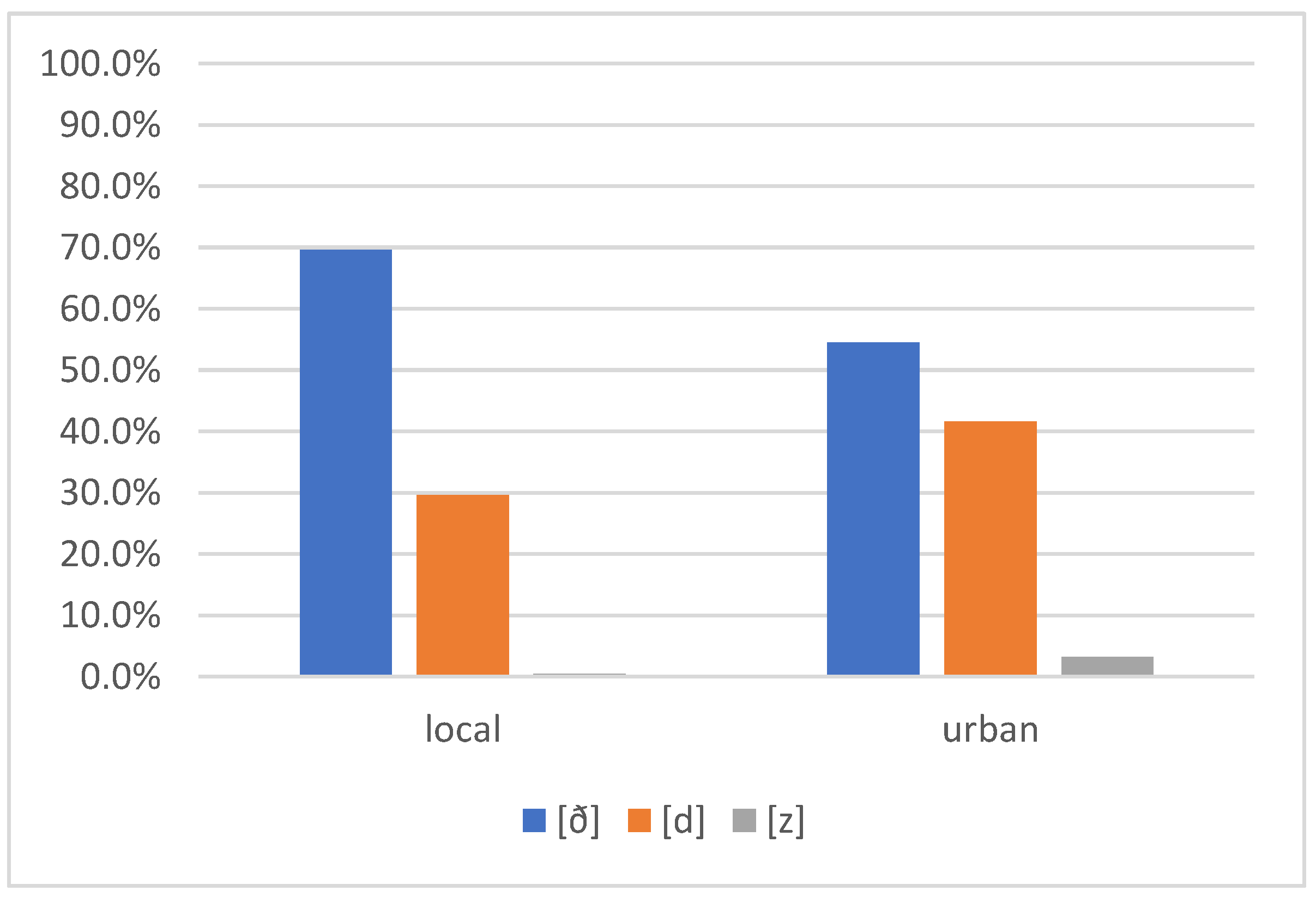

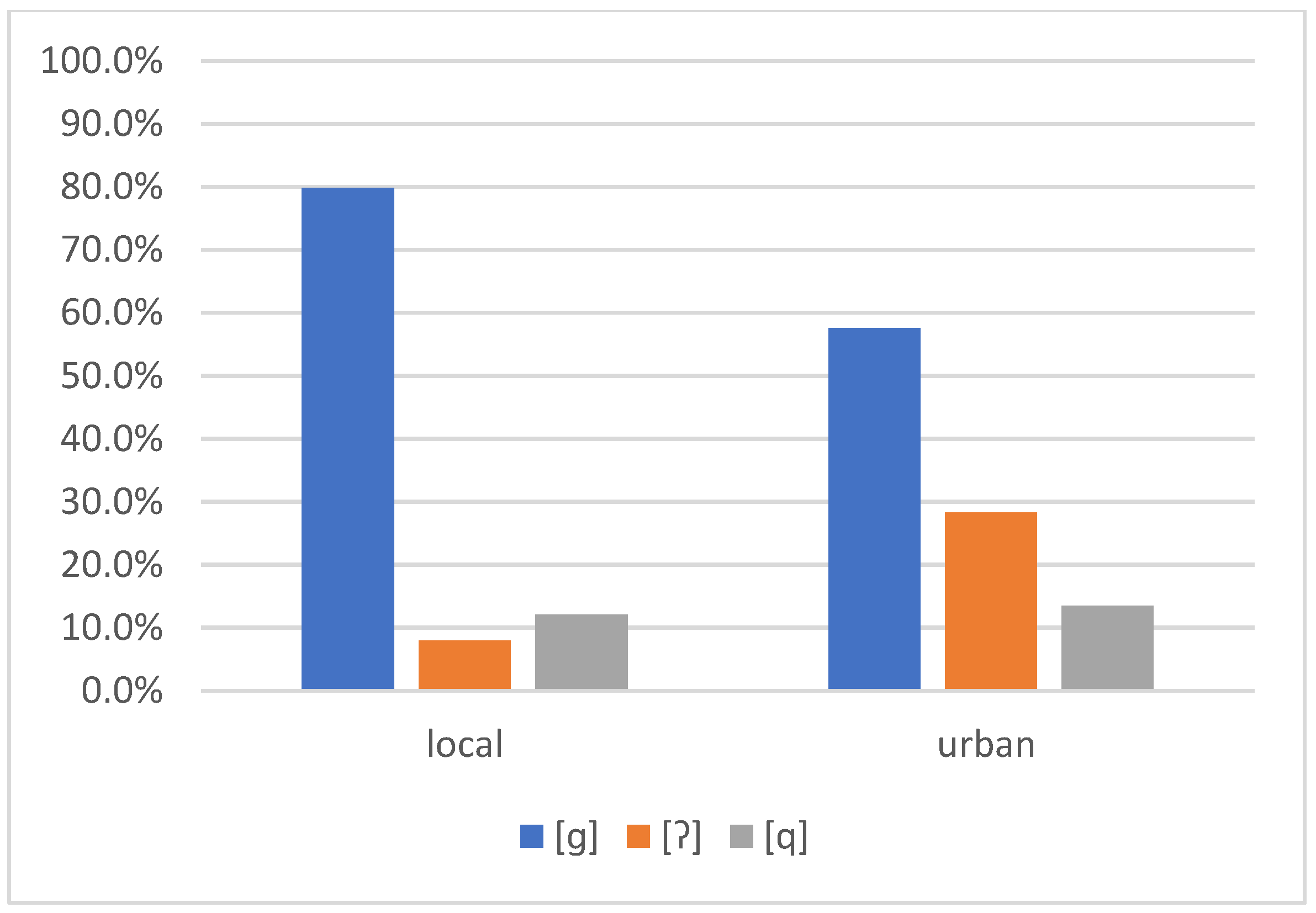

Although differences in variant distribution across the two interlocutors were not always significant, an obvious trend of convergence towards the urban interviewer occurred in the realization of all variables to varying degrees. Indeed, use of the local variant decreased from about 70% to about 54% in the case of (ð), from about 77% to about 54% in the case of (θ), from about 80% to about 58% in the case of (q), and from categorical use to about 92% in the case of (-a), while use of the urban variants increased. Convergence to an overtly prestigious variety, or what is referred to as upward convergence (

Giles et al. 1991;

Giles and Ogay 2007), is well attested in the literature, especially in situations of dialect contact (e.g.,

Miller 2005;

Habib 2010). It can convey social and linguistic awareness on the part of speakers (

Hinskens et al. 2005) and may express a desire for social mobility, belonging, and social approval (

Giles and Ogay 2007). It might also indicate a positive perception of both the urban interlocutor and the urban variety as accommodative behaviour is shaped by speakers’ perceptions and attitudes towards their own variety and that of the interlocutor (

Thomason and Kaufman 1988;

Gasiorek and Giles 2012). Indeed, speakers tend to converge to those they like and respect or to those they may perceive as belonging to a socially desirable group in an attempt to be associated with them and their positive values (

Giles et al. 1991;

Giles 2008).

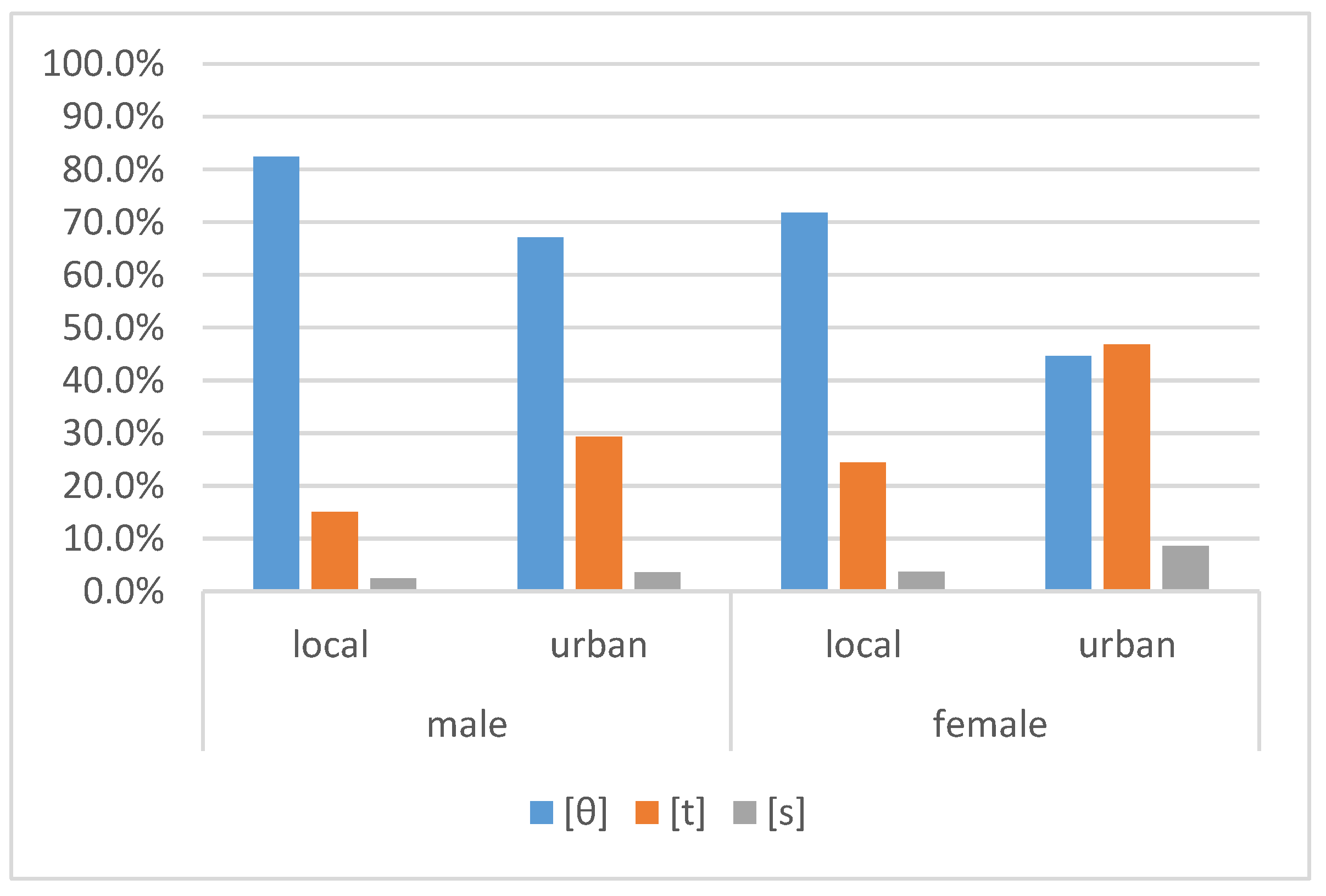

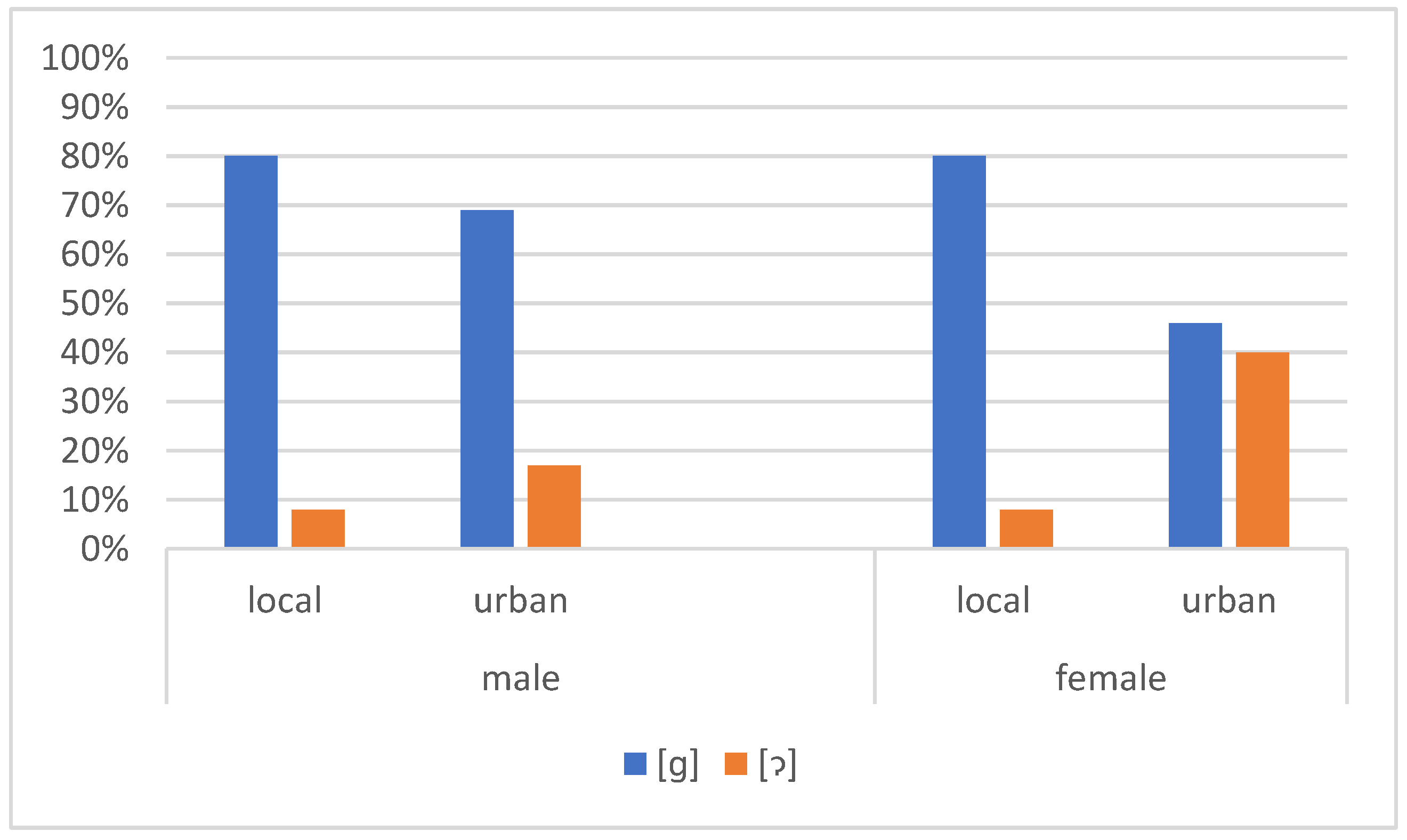

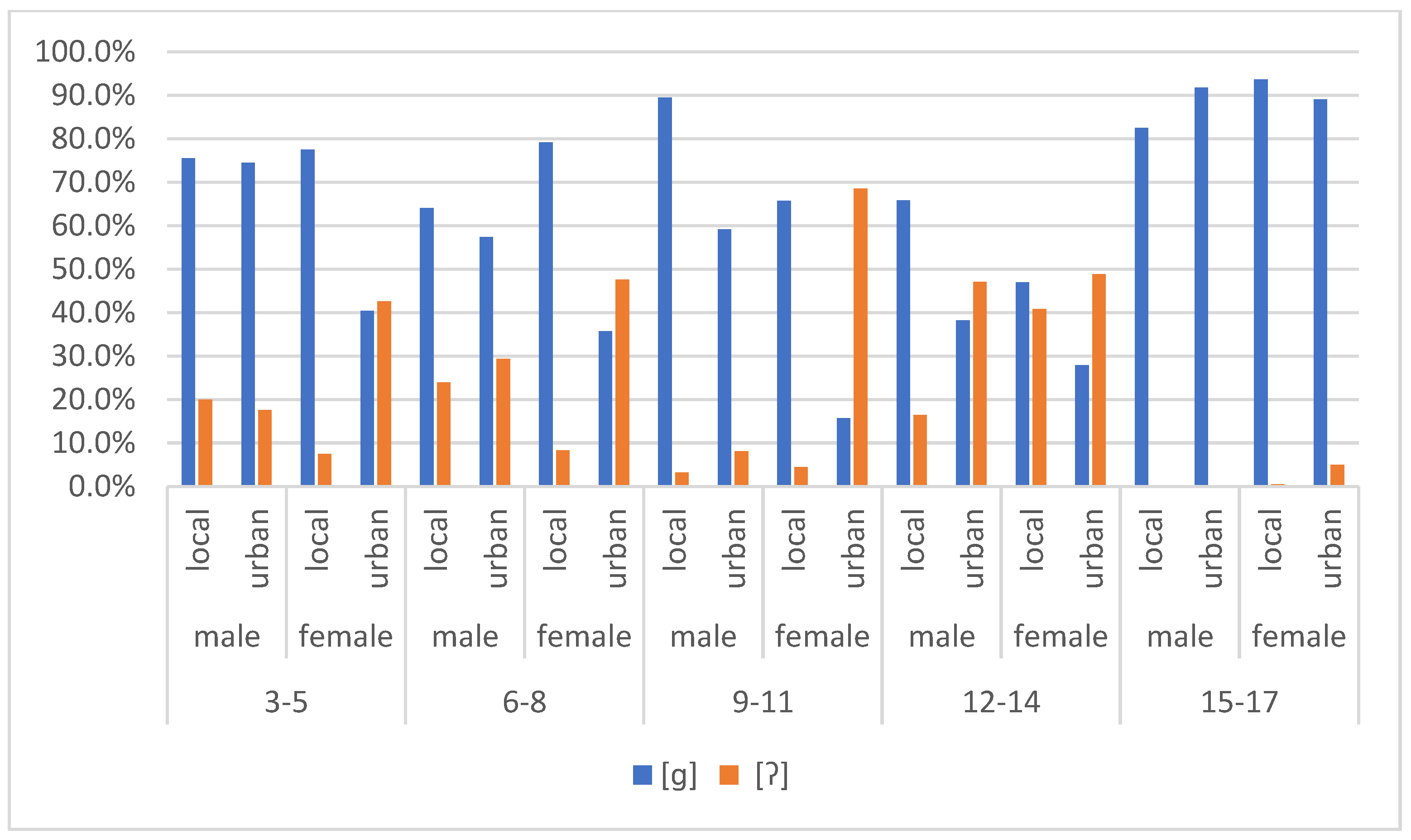

Convergence towards the urban interviewer occurred to varying degrees in the speech of both girls and boys, apart from male speakers in the oldest group. Such convergence was generally higher in the speech of female speakers and gender had an overall significant effect on accommodation patterns in the case of (q), (θ), and (-a). This is in line with previous research which suggests that female speakers are more likely to converge to their conversational partners (

Namy et al. 2002;

Giles and Ogay 2007;

Lelong and Bailly 2011). On some occasions, convergence appeared to be quantitatively higher in the speech of boys than it was in the speech of girls. For example, use of the local variant of (ð) decreased by 23.1% across interview contexts in the speech of boys (from 82.8% with the local interlocutor to 59.4% with the urban interviewer), while it only decreased by 6.5% in the speech of girls (from 55.9% with the local interviewer to 49.4% with the urban interviewer). This was largely because girls generally used the local variants less than boys, even in the local interview context. Gender differences in accommodation appeared even in the youngest age cohort, though not consistently in all variables. For example, while the use of the urban variant of (q) increased from 7.5% with the local interviewer to 42.6% with the urban interviewer in the speech of 3–5-year-old girls, it remained relatively stable in the speech of boys in that age group. This result supports the assertion that gender differences in accommodation appear early on in the speech of children (

Sheldon 1990;

Robertson and Murachver 2003). This pattern persisted with all age groups, despite some notable exceptions. For example, convergence to the urban interlocutor appeared higher in the speech of 12–14-year-old boys, whose use of the urban variant of (q) increased by 30.6% across interview contexts (from 16.5% to 47.1%) compared to girls in the same age group whose use of the variant only increased by 8% (from 40.8% to 48.8%). Similarly, use of the local variant of (θ) decreased by 28.7% in their speech (from 83.9% to 55.2%) but only by 6.2% in the speech of girls (from 33.3% to 27.1%). As discussed above, this was mainly due to girls, especially in these age groups, using the local variants less than boys even in the local interview contexts, as is clear from variant frequencies in their speech.

A relatively similar pattern is reported by

Van Hofwegen (

2015), who examined accommodation patterns in 11–15-year-old African American children. Convergence in the speech of boys in her sample increased at the age of thirteen but decreased again at the age of fifteen, whereas girls’ accommodation patterns were consistent across all age points.

Van Hofwegen (

2015) also found that girls were more likely to accommodate to peers as well as unfamiliar interlocutors, which may explain the relatively modest convergence in the speech of females in the oldest group, given the urban interlocutor’s age as well as her position as a familiar figure in the community. The lack of convergence on the part of boys in the oldest group may also be due to the interlocutor’s age and gender as adolescent boys are more inclined to accommodate to peers in same-sex dyads (

Tuten 2008;

Van Hofwegen 2015). Research also shows that speakers who are intrinsically more variable are more likely to converge to their conversational partners (

Lee et al. 2021), which may explain the diminished convergence in the speech of the oldest group compared to younger speakers in the sample. Indeed, the results show an overwhelming preference for local variants by 15–17-year-old participants, indicating little variability in their speech and leaving little room for convergence. On the other hand, the speech of participants younger than 15 is highly variable, leading to more convergence.

In addition to the quantitative results summarized above, accommodative behaviour in the speech of participants was manifested through various other strategies. For instance, on some occasions, convergence to the urban interviewer occurred as direct imitation, as indicated by the following example from the speech of a boy in the 3–5-year-old group:

| (1) | Urban interviewer | hai | ɣazæ:le |

| | | this | a deer |

| | This is a deer (Referring to a toy figurine) |

| | Child: | ɣazæ:le? | |

| | A deer? | |

This interaction features the urban realization of the feminine marker (-a) in the pronunciation of the word [ɣazæ:l

e] ‘deer’. As indicated by the results, little variation occurred in the realization of this variable, which suggests that the child in this interaction was engaging in direct imitation. Predictably, overgeneralisations in an attempt to converge to the urban interviewer also occurred in the speech of some young children. For example, for

ɡæto- ‘cake’ as borrowed and modified from French, a six-year-old boy used the word [

ʔæto] in a clear overgeneralization of the urban [ʔ] for what he perceived as the local realization [ɡ] of (q). Overgeneralization of [ʔ] also occurred in the speech of a 9-year-old girl who used [ma

Ɂdu:s] for [ma

gdu:s]

2—a traditional Syrian breakfast staple—in a clear attempt to converge to the urban speaker. Various such ‘mistakes’, some of which result from not yet mastering the lexical or phonological conditioning of non-native variants (

Kerswill 1995), occurred in the speech of participants as they aimed to converge to the urban interlocutor. For example, a 10-year-old girl, who had not yet mastered the lexical split in the urban realization of (ðˁ), used [zˁ] in the realization of (Ɂɑ

ðˁɑːfɪɾ) ‘fingernails’, rather than [dˁ]. Interestingly, using the urban fricative realizations of interdental fricatives (i.e., [s] for (θ), [z] for (ð) and [dˁ] for (ðˁ)), whether erroneously or otherwise, was extremely sporadic in the data, which may suggest a general disfavouring of these variants as too urban (see

Shetewi 2018 for more detailed insights). At the same time, this may indicate an earnest effort of convergence on the part of this young speaker, as well as a strong preference for urban realizations. Her realization is also an example of interdialectal or intermediate forms (

Trudgill 1999), which were, expectedly, abundant in the data. In this instance, the speaker only modified her realization of (ðˁ), keeping the vocalic pattern of her native dialect rather than using the urban [Ɂɑ

dˁɑf

i:ɾ]. Other such examples where the native vocalic structure is maintained and only one phonological feature is modified include: i) [

Ɂal

atli] ‘she told me’ for the urban [

Ɂæ:litli] where only the realization of (q) is modified from the local [ɡ] to the urban [Ɂ], ii) [ʔanɑ

dˁdˁifha] ‘I clean it’ for the urban [bnɑ

dˁdˁifa] where only the realization of (ðˁ) is modified from the local [ðˁ] to the urban [dˁ]. Interdialectal forms where surface features are retained while the vocalic structure is changed also occurred in the data. For example, some speakers used the urban vocalic pattern in words like [

ɡamaɾ] ‘moon’ and [b

aɡara] ‘cow’ in place of the traditional [

ɡumaɾ] and [b

ɡara], but used the local realization of (q) rather than the urban glottal stop. In these examples, the local vocalic structure seems to be more indicative of ‘Bedouinesss’ than [

ɡ] and is, therefore, abandoned. Indeed, the traditional vocalic pattern of these words never occurred as part of participants’ typical speech in the present study. One male speaker in the 15–17-year-old group jokingly used the word [b

aɡara] ‘cow’, which may indicate that such features are viewed as ‘outdated’ and are overtly stigmatized.

These examples suggest that (socio)linguistic competence has an impact on speakers’ ability to accommodate, as well as on the level of such accommodation (

Pitts and Harwood 2015). Overgeneralization may, thus, occur in situations where speakers do not have full command of the sociolinguistic constraints of their interlocutor’s variety. This is especially true in the case of young children who do not have access to the full range of styles in language (

Kerswill 1996).

Giles et al. (

1991) also note that accommodation can either be manifested on a large scale whereby a completely different mode of communication is adopted, or it can simply occur in a small aspect of speech but not in another. Likewise, speakers may converge to certain features while diverging on others. This is a unique characteristic of accommodation as it pays attention to both micro and macro communicative modes (

Giles et al. 1991). Indeed,

Trudgill (

1986,

1999) also argues that convergence is about reducing differences rather than eliminating them and does not have to result in a complete change to one’s phonology. He proposes that such adjustments may result in intermediate forms, as evident from the examples above. What features may be subject to change depends on their social and linguistic constraints, as

Kerswill (

1995) explains that surface features that have sociolinguistic salience and are consciously recognised by speakers are the first to undergo change, whereas complex underlying features are harder to change. The examples above show that both surface and underlying features may be subject to change, which indicates that features that are regarded as more stigmatized are abandoned first, whether they are surface or structural features. Indeed,

Hinskens et al. (

2005) suggest that convergence may be achieved by either approximating linguistic forms of the other group or by avoiding one’s own marked features, and previous research shows that highly stigmatized features are, in fact, found to be particularly susceptible to change in contact situations (e.g.,

Miller 2005 on rural speakers in Cairo).

As observed above, in addition to being impacted by age and gender, accommodation patterns were also influenced by linguistic variables under examination. For example, convergence towards the urban interlocutor seems to be most drastic in the use of the (q). Use of the urban variant of (q) increases from 8.3% with the local interviewer to 48% in the interview with the urban interviewer in the speech of 6–8-year-old female speakers, whereas use of the local variant drops from 79% with the local interlocutor to 35% with the urban interlocutor. In the speech of 9–11-year-old girls, use of the urban variant of (q) rises from just 5% with the local interviewer to 69% with the urban interviewer and their use of the local variant drops from 66% in the interview with the local interlocutor to 16% in their speech with the urban speaker. This indicates that the variable is highly marked in the community as girls in these groups appear to be the most conscious of prestige features, as evidenced by their linguistic choices in general and in their speech to the urban interlocutor, in particular. Indeed, in conversations with adult members of the community, a few of them remarked that they made a conscious decision not to use [ɡ] with their children and to discourage them from using it as not to be ‘ridiculed’ when they eventually go to Damascus to study in the university.

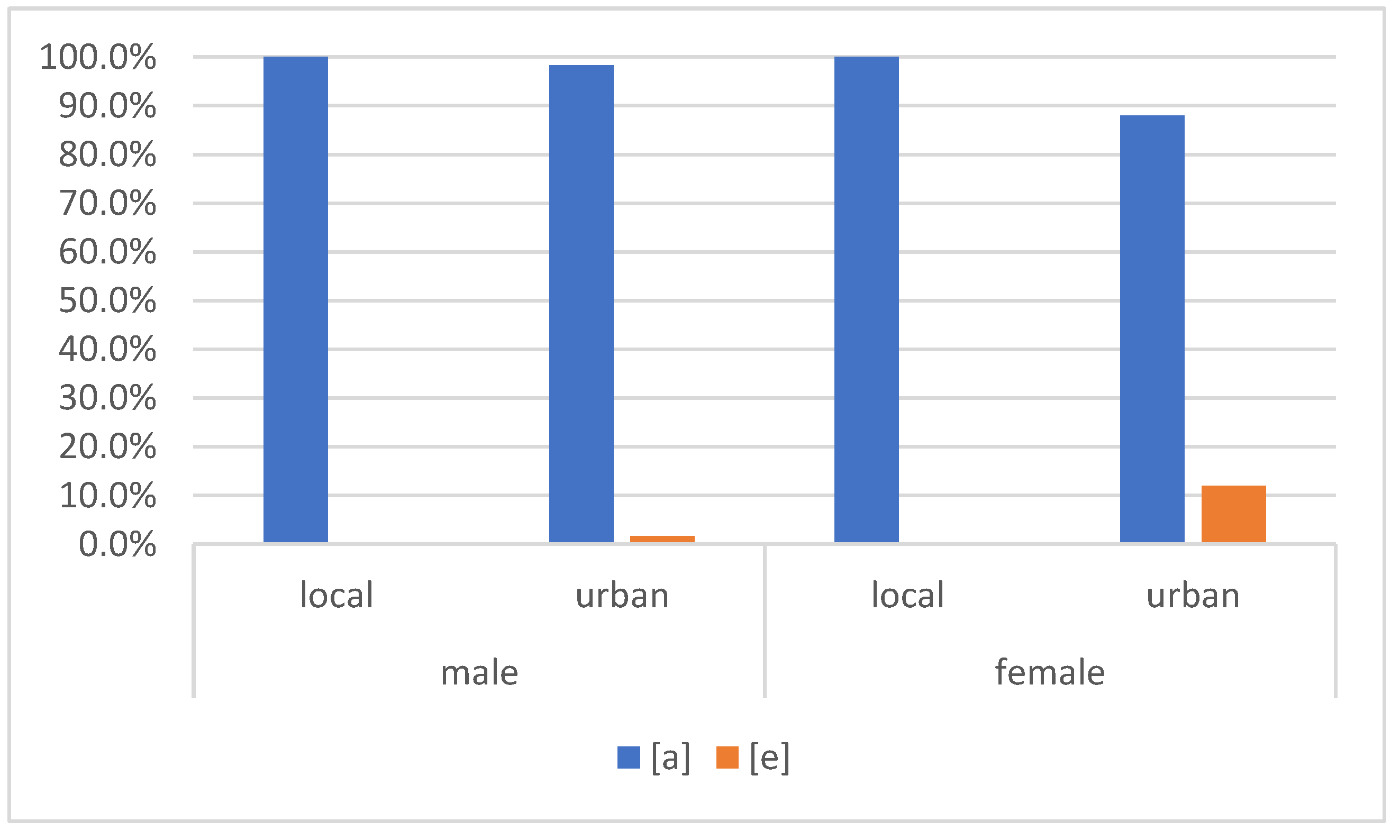

3 Conversely, little accommodation occurred in the realization of the feminine suffix (-a) despite the significant difference in variant frequencies across interview contexts. A closer look at accommodation patterns of (-a) revealed that convergence to the urban speaker was largely limited to girls in the 9–11 and 12–14-year-old groups, who were found to overwhelmingly favour urban variants throughout (see

Shetewi 2018 for more detail). Limited accommodation, and indeed variation (cf.

Al-Wer et al. 2022), in the realization of this variable may be due to the complex phonological conditioning involved in its urban realization, compared to the simple rule of no raising that applies in the local dialect.

Kerswill (

1995) explains that complex dialect features require early exposure for complete acquisition, and

Miller (

2005) observes that a high degree of difference between contact varieties complicates the process of accommodation. This feature may also carry what

Trudgill (

1986) refers to as “extra-strong salience”, and, as such, is not adopted by speakers in the community (

Watt et al. 2010). Indeed, an adult female speaker from the community remarked that while she uses the urban variant of (q) in her speech, she would never use the urban variant of (-a). Evoking (-a) as a feature that she would not change was not prompted, so in response to a follow up question, she explained that using it would feel like going ‘too far’ and putting on a fake accent when her goal is to simply ‘tone down’ her accent and not sound so ‘Bedouin’ and she achieves that by abandoning [ɡ]. Patterns of accommodation in the realization of interdental fricatives were relatively variable, especially for female speakers between 6 and 14 years old, given the higher rates of adoption of the urban stop variants in their speech (e.g., in comparison to (q) and (-a)). Accommodation patterns in the use of interdental fricatives, in comparison to those in the use of (q), may also have been impacted by the retention of interdentals by the Urban interviewer. Still, obvious convergence to the urban interviewer appeared in realizations of these variables throughout (apart from speakers in the 15–17-year-old group). Interestingly, accommodation to, and indeed adoption of, urban variants in realizations of interdental fricatives was almost exclusively manifested through use of the urban stop variants (i.e., [t] for (θ) and [d] for (ð)), and not the urban fricative variants (i.e., [s] for (θ) and [z] for (ð)). As the split in urban realizations of interdental fricatives is primarily lexically conditioned, with the fricative variants being mainly used in lexical borrowing from SA (see

Habib 2011a), it can be argued that speakers in this community have no need for those variants since they have access to the interdental fricatives in their own native repertoire (see

Shetewi 2018 for further details). Indeed, the same adult speakers who expressed a positive attitude toward the urban variety and explicitly discouraged their children from using local variants (primarily [ɡ]) remarked that ‘we are able to pronounce interdental fricatives ‘correctly’ and have no ‘need’ for [s] or [z].

7. Summary and Conclusions

The results and discussion above give various important insights on the language development and linguistic practices of these children and adolescents, as well as shed some light on patterns of variation and change in the community.

For example, convergence to the urban speaker by children in the youngest age group, which is in line with previous research that finds accommodative behaviour to emerge early in children (e.g.,

Paugh 2005;

Montanari 2009;

Kaiser 2022), suggests a good level of social and linguistic awareness on the part of these children. Such convergence was manifested through direct imitation on some occasions, as noted in example one above. However, this does not discount the level of social and linguistic awareness on the part of children in this young group, but rather serves to show their ability to observe differences between their speech and that of the urban interlocutor (

Hernández 2002;

Paquette-Smith et al. 2019). Moreover, imitation, especially in phonetic convergence, is well-attested in the literature, even for adult speakers (

Namy et al. 2002;

Babel 2012;

Nielsen 2011;

Babel et al. 2014;

Paquette-Smith et al. 2022). Indeed, children become aware of the social value of the linguistic features in their environment at an early age, which may, in turn, impact their language use (

Cornips 2020). On the other hand, previous research also shows that children’s ability to adapt their speech to context/interlocutor is not dependent on their knowledge of the social value of linguistic features (

Chevrot et al. 2000). So, while the results show young children’s ability to accommodate and may suggest a positive evaluation of the urban interlocutor and dialect (

Giles et al. 1991), their patterns of accommodation may simply be influenced by their input, which in this speech community is mostly female-oriented (see

Shetewi 2018 for more detail). As such, convergence in their speech might denote conformity to what is perceived as ‘female’ speech patterns, which is a conclusion that is supported by the overall preference for urban variants in the speech of this group.

Such preference for urban variants persists, and even increases, in the speech of girls between 6 and 14, while an opposite trend emerges for boys in the same age groups. This results in some drastic differences in rates of accommodation between girls and boys in this age range, as detailed in the previous section. This is because, despite their overall preference for local variants, boys in this age range exhibit considerable convergence towards the urban interviewer. The higher overall use of the urban variants by girls in this age range may indicate long-term accommodation, given that they adopted such variants in their own speech and are using them outside of interactions with urban interlocutors (

Auer and Hinskens 2005, p. 336). Likewise, higher proportions of urban features in the speech of the youngest group, presumably reflective of their primarily ‘female-oriented’ input, may reflect long-term accommodation in the speech of their primary caregivers (see

Shetewi 2018 for more details). Indeed, given the model of dialect contact in this speech community, which is in the form of geographical diffusion as explained in

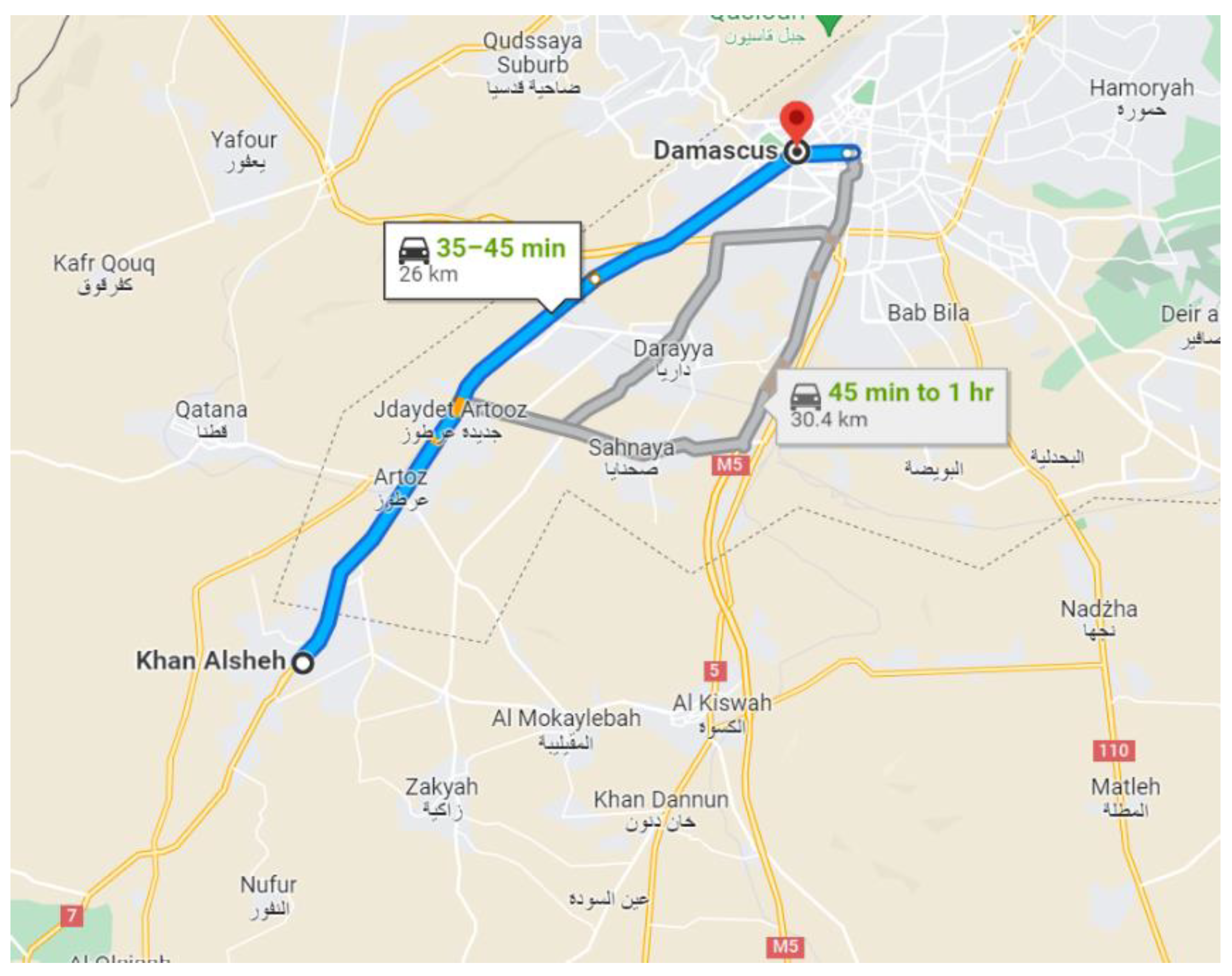

Section 3 above, children’s variable input, which is most clearly reflected in the speech of the least mobile participants, is indicative of language change in the community. While it may not be reliably concluded, based on the results from this dataset, that such language change is a result of interpersonal accommodation, some aspects of dialect levelling are ‘foreshadowed’ (

Auer and Hinskens 2005, p. 347) in some of the accommodation patterns manifested in this study.

Conversely, accommodation patterns in the 15–17-year-old group, with slightly decreased convergence in the speech of girls and overwhelming maintenance in the speech of boys, may also indicate a conscious effort to conserve group identity (

Bourhis 1984;

Giles and Ogay 2007), especially given the prominence of identity practices in the lives of adolescents (e.g.,

Van Hofwegen 2015;

Tuten 2008). They indicate a positive attitude towards the local variety and community. In the context of this study, such an attitude may have been enhanced by the fact that interviews were carried out in participants’ houses and, as such, these speakers were operating within their physical and emotional space, while the urban interviewer was viewed as the outsider in the situation. Moreover, convergence to an overtly prestigious norm is argued to be an attempt at membership of a socially attractive group (

Giles and Ogay 2007), which is a sentiment that is not expressed by this age group, as evident by their overwhelming preference for the local variants throughout the data (

Shetewi 2018,

2023). In fact, adolescents are found to be rebellious rather than seeking approval and integration, especially when interacting with adults (

Labov 2001;

Eckert 2017). They use language to construct independent social identities and express belonging to peer groups, rather than identify with adults (

Eckert 2004, pp. 112–13), and such strong identity practices often manifest in divergence from adult speech norms (

Garrett and Williams 2005). In dialect contact settings, such focus on constructing independent identities coupled with a general tendency towards the vernacular may manifest in adolescents preserving their own dialect features. This is attested in situations of contact involving minority and dominant varieties where a local/ethnic orientation is an especially strong index in peer group affiliation (

Rampton 1995;

Van Hofwegen 2015) and may, by extension, apply in situations involving regional or national identities, such as in the case of the present study. Indeed, speakers in this group seem to be using language to index a Palestinian identity. They seem to view linguistic variation in their environment as not simply urban vs. Bedouin but rather Syrian vs. Palestinian (

Shetewi 2018,

2023). As such, it is not surprising to find maintenance and even divergence patterns in the speech of adolescent boys, especially. Indeed, one of the male speakers in this group seemed to diverge his speech even further from the urban interlocutor after she commented that it is

ħɑrɑ:m ‘forbidden in Islam’ for him to become a hair stylist. This divergence was expressed by affricating (k) into [tʃ] in the second singular feminine suffix, a feature that did not occur in his speech with the local interlocutor and one that may be viewed as ‘outdated’ and ‘too traditional’. Indeed, this feature only occurred twice in the data set, with the other occurrence being in the speech of a 17-year-old girl who laughed as she used it and commented embarrassingly that people laugh when she ‘talks like this’, indicating that it is viewed negatively by some people. The speaker’s divergence on this occasion appeared to signal a conscious effort to further distance himself from the interviewer in response to a negative comment she made about his career goals (

Giles et al. 1991;

Zhang and Giles 2018). Convergence in the speech of boys younger than 15 also implies that a strong sense of local identity is more pronounced in adolescents in the community regardless of age.

The above observations presume that children’s and adolescents’ accommodative behaviour in this study is socially motivated. This is supported by various indications in the data, including divergent behaviour in the speech of 15–17-year-old speakers. More importantly, low rates of accommodation in the realization of (-a), which is consistently realized as [e] by the urban interviewer, compared to the high rates of accommodation in the realization of (θ) and (ð), which are overwhelmingly retained in her speech, suggest that convergent behaviour in the speech of participants is not always motivated by the objective speech patterns of the interlocutor but rather by the expectations of how she should sound, based on certain stereotypical features.

Wade (

2022) refers to this as ‘expectation-driven’ accommodation as opposed to ‘input-driven’ accommodation and notes that while the latter might occur as an automatic response, the former is largely based on social motivations. This is well-attested under the framework of Communication Accommodation Theory, whereby accommodative acts are often based on underlying beliefs and attitudes, which do not always match objective reality (

Thakerar et al. 1982;

Dragojevic et al. 2016). Listeners use their conversational partners’ speech norms, especially phonological features (

Coupland 1985), to form their own social perceptions of them, which, in turn, would impact their own accommodation patterns (

Gasiorek and Giles 2012;

Garrett 2010;

Auer and Hinskens 2005). This also echoes

Bell’s (

1984,

2001) referee design, whereby speakers may adapt their speech beyond their conversational partners based on their own perceptions and associations of the interaction. According to

Bell (

1984, p. 185), the shift in speakers’ language use in such cases is ‘initiative’ rather than ‘responsive’, and often involves hyperconvergence beyond the interlocutors’ own speech patterns. This suggests that children’s convergent behaviour in this current study is primarily socially motivated. The overgeneralizations and speech ‘mistakes’ noted above support this conclusion and show that, although not fully competent in the urban variety they attempt to emulate, children in the community use the linguistic resources available to them in a strategic and socially appropriate manner. This study examined accommodation patterns across a wide range of ages encompassing children as young as three, at the early stages of structured variation, all the way up to the last year of secondary school, which marks the threshold of sustained mobility that follows it. Further research that examines accommodation patterns in the speech of adult members of the community, who are generally more mobile and experience more face-to-face contact with speakers of other varieties, may uncover interesting insights on the linguistic practices and language attitudes that may result from a different mode of contact. Additionally, the mobility caused by the unfortunate events in Syria offers further opportunities for examining such themes in the speech of children and adolescents who now reside in nearby localities outside of the speech community. Diverse modes of contact, in addition to varying considerations of identity, may have different implications on their language use but will, equally, offer important insights on their linguistic development.