Abstract

This project investigates English–Spanish codeswitching in internet memes posted to the Facebook page, We are mitú (mitú), and analyzes how lexical insertions and quotatives contribute to the enregisterment of linguistic patterns and the construction of collective identity among U.S. Latinx millennials in virtual social spaces. Data include instances of lexical insertion (n = 280) and quotative mixed codes (n = 114) drawn from a collected corpus of 765 image–text memes. The most frequent lexical insertions included food items (e.g., elote and pozole), kinship terms (e.g., abuelita and tía), and culturally specific artifacts or practices (e.g., quinceañera and lotería), which reflect biculturalism and rely on a shared set of references for the construction of a group identity. Additionally, the quotatives in the data construct Spanish-speaking characterological figures that enregister a particular brand of U.S. Latinx millennial identity that includes being bilingual, having Spanish-speaking parents, and having strong ties to Latinx culture. Overall, this work highlights not only internet memes as a vehicle for enregisterment, but also, and more importantly, how the language resources employed within them work to enregister linguistic and cultural norms of U.S. Latinx millennials, and thereby, play a role in identity construction in virtual social spaces.

1. Introduction

The combined use of English and Spanish on social media in the United States represents the confluence of two phenomena: (1) the coexistence of Spanish and English in the U.S. (Ortman and Shin 2011; U.S. Census Bureau 2015) and (2) the widespread use of social media for virtual community interaction. This project is situated at the intersection of these two phenomena, investigating the use of English–Spanish mixed code in image–text internet memes (henceforth referred to simply as “memes”). The goal of this paper is to analyze the ways in which the language resources employed in these memes can work to enregister linguistic and cultural norms of U.S. Latinxs, and thus, play a role in identity construction.

This project focuses on the Facebook page, We Are mitú (mitú),1 a U.S.-based Latinx2 online media organization, and analyzes how codeswitching practices within the memes posted by the page both illustrate Spanish–English contact in the U.S. and work to construct U.S. Latinx millennial identity.3 This site was chosen for several reasons. First, it represents a large repository of bilingual meme content in a single location. Second, mitú describes itself as “100% American and 100% Latino”, inspired by its community “to create authentic, culturally relevant stories”, and it frequently posts videos, articles, and humorous content in English and Spanish. This express goal of engaging with U.S. Latinx experiences makes it an interesting site for analyzing the ways in which language can be used to construct identities. Third, as of December 2019, the group’s Facebook page had over four million followers. While it is not possible to ascertain the number of individuals who regularly consume the media posted to the page, the sheer number of followers reflects its popularity and potential for reaching a large audience. Overall, this page offers a unique opportunity for the investigation of the enregisterment of linguistic forms in memes targeted to U.S. Latinx individuals.

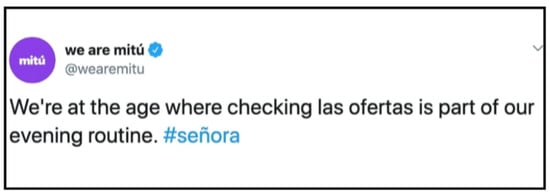

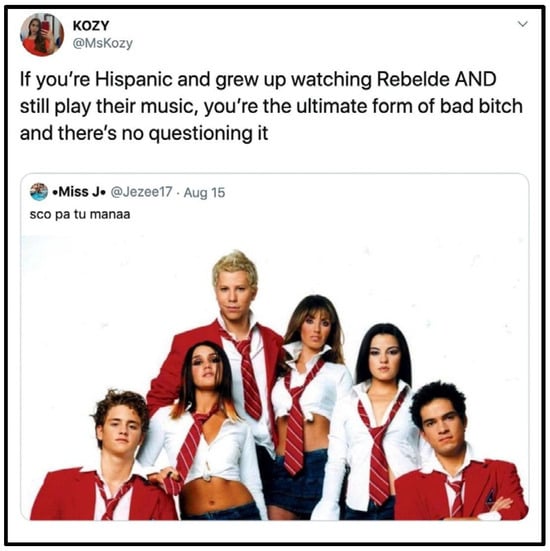

The target audience of the page is listed as internet users between the ages of 18 and 44. In a 2015 interview, the mitú cofounder, Beatriz Acevedo, noted that one of the goals of the organization was to be the “voice of the millennial generation”.4,5 In this vein, much of the page’s content contains overt acknowledgement of the age of its intended audience. For example, the post in Figure 1 claims that “we”, referring to both the poster and the intended audience, are old enough to be spending time looking for shopping deals (las ofertas). Furthermore, the post includes the hashtag #señora, a term used in Spanish to refer to either a married or an older woman. Additionally, many cultural references within these posts relate to things that were popular among adolescents in the early 2000s, when millennials were coming of age. For example, Figure 2 and Figure 3 refer to the Mexican television show, Rebelde, which aired during this time of millennial adolescence.

Figure 1.

Generational reference on mitú.

Figure 2.

Rebelde reference #1 on mitú.

Figure 3.

Rebelde reference #2 on mitú.

In this paper, I use both quantitative and qualitative analyses to illustrate how the communicative functions of the lexical and quotative codeswitching patterns employed in these memes are not only a reflection of U.S. Latinx millennials’ day-to-day experiences, but also work to construct and enregister an ethnolinguistic identity in a dynamic internet community. More broadly, this work highlights the role of the internet as a sociolinguistic space, the recruitment of image–text memes as a vehicle for the transmission of meaning, and how the linguistic resources employed within these memes can enregister linguistic practices.

2. Background

The present work draws on theoretical insights from a number of related fields, including previous research on codeswitching, computer-mediated communication, social theory, and third-wave sociolinguistics. In what follows, I synthesize some of the important findings from these fields that inform the analysis of linguistic practices in the memes under consideration.

Memes, in the broadest sense, are units of cultural transmission that are replicated and reproduced in human communities through imitation, as defined by evolutionary biologist and social theorist, Richard Dawkins (Dawkins 1976, p. 205). According to Blackmore (1999, p. 7), “Everything that is passed from person to person in this way is a meme”, including skills, ideas, and elements of language. Memes and their transmission have greatly increased with the rise of the internet as means a communication (Blackmore 1999), as the internet provides an ideal platform for the exchange of ideas across space and time.

In present-day popular culture, the term “meme” refers to a cultural or community idea that is replicated and mutated on internet-based platforms. According to Lankshear and Knobel (2007, p. 202), the term “meme” is used among internet users in “describing the rapid uptake and spread of a particular idea presented as a written text, image, language ‘move,’ or some other unit of cultural ‘stuff.’” While it is still an emerging area of analysis, various authors have endeavored to identify the shared characteristics of internet memes. Zappavigna (2012) describes internet memes as a display of interpersonal, semiotic bonding used by in-group members to signal solidarity. Memes continually evoke a shared set of references that enhance a particular group of users’ sense of unity (Baym 1995; Miltner 2014) by tapping “into shared popular culture experiences and practices” (Lankshear and Knobel 2007, p. 207). According to Zappavigna, memes are a kind of “inside joke”, where the shared ideas of a particular community, which are not necessarily humorous in isolation, are combined in novel and surprising ways. Furthermore, Miltner (2014) discusses how particular referential knowledge is required to “get the joke” of a particular meme, creating a sort of “communal wall” between those who understand the joke and those who do not, making memes part of an interconnected, self-referential network of meaning bound to the context of their creation and dissemination.

The very nature of internet memes facilitates processes of enregisterment, or the process by which linguistic forms become ideologically associated with social identities (Agha 2003). In later work, Agha (2005, p. 38) elaborates on enregisterment as “processes whereby distinct forms of speech come to be socially recognized (or enregistered) as indexical of speaker attributes by a population of language users”, such as “Japanese women’s language” (Inoue 2003) or “internet language” (Squires 2010). In Section 4, I apply this framework to show how the repetitive nature of internet memes can facilitate enregisterment in mitú’s content.

Internet memes can also represent performances that reinforce existing links between linguistic features and particular identities. For example, Shifman (2013) analyzes the popular 2007 video “Leave Britney Alone”, in which an internet user tearfully and forcefully defends pop icon, Britney Spears. The author describes how the resulting memes emphasized the communicative strategies and codes used by the video’s creator, such as high emotionality and yelling. Additionally, in their analysis of the “It Gets Better” internet movement supporting LGBTQ youths, Gal et al. (2016, p. 1710) conceptualize the memes in the campaign as “performative acts”, designed either to persuade an audience or to construct collective identity and community norms.

The representations and performances that link language forms and social identities are often referred to as “characterological figures”, or stereotypical personae that can be linked to speech (Agha 2006, p. 177). For example, in Johnstone’s (2017) analysis of talking plush dolls meant to represent people from Pittsburgh, she finds that the speech attributed to the dolls both presupposes and helps to create the characterological figure of a “Yinzer”, i.e., a working-class person from Pittsburgh. In other words, the linguistic characteristics and appearance of the dolls work to re-enregister an already enregistered variety by reinforcing the link between communicative style and the local working class. The fact that such characterological figures can be crafted by companies and media organizations and can implicitly promote the processes of enregisterment via their broadcasting to a particular audience are important for the current study.

The relationship between form and meaning can be different depending on who is listening and who the players are in a given interaction. For example, Johnstone (2011) analyzes enregisterment processes through a character in a radio DJ skit whose speech patterns are used to perform several identities, including a mother, a working-class person, and a Yinzer. The author notes that Pittsburgh-specific linguistic features are more likely to be salient to those listeners familiar with the local vernacular, while other features invoke more broad-reaching cultural schemas of motherhood to a more general audience. In this way, enregisterment does not create fixed associations between language forms and social meaning, but rather it is a process of “constituting possibilities” for the creation of varied sets of meaning for both speakers and hearers in a given interaction (Goebel 2007, p. 523).

The potential for characterological figures to perform multiple identities and to project diverse sets of meanings depending on the context and the listener is particularly relevant to the enregisterment of language on the internet, where messages are frequently repeated and altered and can be observed by a vast number of people. In his study of Jamaican Creole and English use on the internet, Hinrichs (2006, p. 110) describes switches between the two languages as explicit performances of “a typical Jamaican in conversation”. Through this performance of “Jamaicanness”, in-group members recruit stylistic, sociopragmatic resources as part of identity construction to position themselves in relation to the content of the discourse. Regarding Spanish in particular, in her study of the use of Mexican Spanish by transnational second-generation Mexican bilinguals on Facebook, Christiansen (2015a) found that individuals use multiple linguistic strategies to index their identity and counter-identity as ranchero (a social group associated with rural life in Mexico). The author interprets group members’ alternation between embracing and distancing themselves from ranchero culture as a performance that is “reminiscent of their collective past but fitted to contemporary U.S. Mexican culture” (Christiansen 2015a, p. 699). In another study of the same online ranchero community, Christiansen (2015b) found that individuals use their perceived degree of “centrality” to ranchero culture, social networks, and the Spanish language to position themselves as more or less Mexican in an online environment.

Similarly, the memes on the mitú page often use characterological figures to construct and reinforce a particular kind of U.S. Latinx millennial identity, which may or may not reflect the real lives of the page’s followers. For some followers, the memes can reinforce and re-enregister their own realities. For those with divergent experiences, the meme content can work to enregister the linguistic and cultural patterns they display as part of a generalized U.S. Latinx millennial experience. In both cases, the content of the memes can work to construct a particular U.S. Latinx millennial identity, relying on the perception of shared community experiences and understanding. Previous work on identity building in mitú’s content has shown that this perception of shared experiences is a critical element of the organization’s content. Gutiérrez (2021, p. 80) describes the cultural and language practices in mitú content videos on the Pero Like channel as “emblematic of a generation, elucidating how Latinx millennials come to mediate panethnicity while creating new forms of Latinx media representation”. Additionally, the author notes how the use of characters such as the abuela (‘grandmother’) by the content creator, Jenny Lorenzo, based on her own grandmother, are meant to exemplify a sort of universal Latina immigrant grandmother figure (p. 90) and represent the Latinx millennial experience as well as generational differences.

Given that the present study focuses on how codeswitching is deployed within the memes posted to mitú, it is critical to establish what is meant by the term. There has been a debate in linguistics about codeswitching typologies and what exactly constitutes true codeswitching. Nevertheless, it is generally agreed that the terms intersentential and intrasentential codeswitching refer to complete switches from one language or variety to another between and within sentence boundaries, respectively (Poplack 1980; MacSwan 2014; inter alia). A more contested type involves the use of a lexical item from one language within a different matrix language. The literature has used a variety of terminologies to describe this, including insertion and borrowing (Poplack 1980; MacSwan 2014; Muysken 2000; Woolford 1983; inter alia), though these phenomena have often been differentiated from other types of language mixing and have traditionally been classified as falling outside of the umbrella of codeswitching (Poplack 1993, pp. 255–56, 279). However, Muysken (2000, p. 69) suggests that, while there may be formal, structural differences between borrowing and codeswitching, they can fulfill similar discursive functions, such as the symbolic role of marking multicultural identity. Backus (2015) also follows this assertion, stating that, while borrowings and codeswitching may differ diachronically, their synchronic function and sociopragmatic indexicality are often the same. Therefore, codeswitching is used in the present work as a pre-theoretical term that encompasses all of the aforementioned types of language mixing, including all instances of Spanish and English being used together in the same discursive context. Following Androutsopoulos (2015 p. 187), multilingualism can be better examined when considering “any discourse that draws on resources associated with more than one language”. Additionally, so-called hybrid linguistic forms (e.g., stress-itos, an English word with a Spanish diminutive suffix) can be included in this umbrella, going beyond a simple mixture of first and second languages (Wei 2018), and can play a role in identity construction (Wei 2011; Wei and Lin 2019). Importantly, this approach to codeswitching allows more robust analysis in that it permits us to observe all possible cases of multilingual discourse rather than being unnecessarily restrictive.

The social and linguistic processes that motivate codeswitching are critical to the present analysis. Previous research has explored this from several perspectives, including functional motivators, language dominance and shifts, lexical and structural mutual influences, and discursive sociopragmatic functions. For example, Muysken (1997, p. 364) suggests that language dominance is reflected in the direction of lexical insertion; first-generation immigrants tend to insert words from the host country into their native language, while subsequent generations tend to insert words from their family language into the language of the host country. Relatedly, Bentahila and Davies (1992) found that speakers of later generations in a host country tend to switch smaller constituents than earlier generations do. These patterns of smaller, often single-word codeswitches in Spanish are frequent in the memes posted to mitú, reflecting the sociodemographic reality for 65% of Latinx millennials, a critical target audience for the page, who are U.S.-born (Patten 2016).

Additionally, previous studies have shown that words that are switched from one language into another tend to be highly specific in meaning or may have differing connotations between the two languages (Backus 2001; Myers-Scotton and Jake 1995), such that biculturalism is often the motivation for lexical switches (Montes-Alcalá 2007). De Fina (2007) shows an example of this in her analysis of the maintenance of Italian food terms in an immigrant community as a means of the construction of an ethnic identity. Similarly, Gutiérrez (2017) discusses the use of food symbolism in selfies taken by Latinx individuals, which employ culturally specific dishes such as tacos and maize as identity representations. A similar trend will be shown in the data from mitú, whereby the content of lexical switches reflects patterns of biculturalism and culturally specific meanings.

3. Materials and Methods

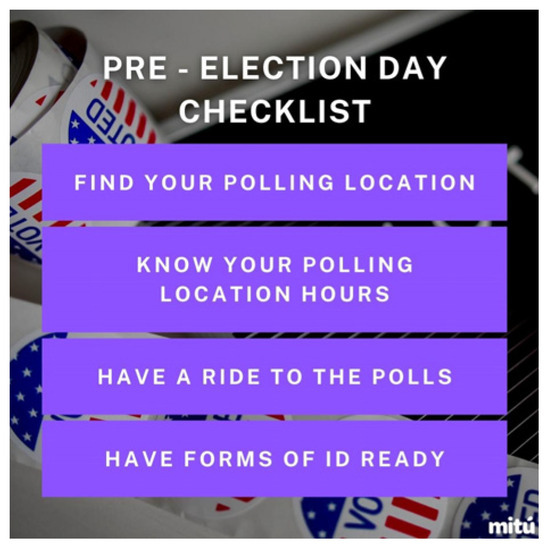

To determine how codeswitching works to enregister linguistic and cultural norms of U.S. Latinx millennials in virtual social space, data were collected from the Facebook page, We are mitú. On Facebook, pages are places where businesses, brands, musicians, organizations, and other groups can connect with fans or customers by posting content that can appear on individual followers’ timelines. Facebook users who follow the mitú page can receive regular updates about the content posted by the media organization.6 Image–text memes were identified from among this content as photos that consisted of some combination of an image and saying and/or phrase, excluding advertisements (Figure 4), simple photos (Figure 5), or purely informational posts (Figure 6). This is not to say that these images do not portray cultural content and symbolism, but they do not fit the definition of a meme as adopted in this project.

Figure 4.

Advertisement on mitú.

Figure 5.

Photo post on mitú.

Figure 6.

Informational post on mitú.

All the memes that were posted by the page over the two-month period from 1 September to 31 October 2019 were collected.7 This was achieved by visiting the page each day and downloading all the memes that had been published since the previous day’s collection. Though the two-month period is limiting, I began this project with the goal of obtaining a large enough sample of memes for analysis. Having collected over 700 memes as the end of October neared, I elected to finalize and analyze the corpus I had gathered. The only items that were excluded were those that were reposted from previous dates already included in the corpus to avoid repetition. All the collected memes were given a unique ID tag and were transcribed into plain text. Then, each meme was examined to see if it contained mixed code. Those that did not include multiple languages were classified as monolingual and were coded as either monolingual English or monolingual Spanish.

After determining that a given meme included mixed code, the switch(es) within it were classified as intersentential, intrasentential, lexical, or quotative/attributive. The present work focuses only on the latter two types because they account for the majority of the data and most clearly reflect the processes of enregisterment discussed in Section 4. Fixed phrases, defined as instantiations of language use that are prefabricated, formulaic, and highly conventional (Kecskes et al. 2018), were excluded from the present analysis. These included proper names, such as the soda brand name, Jarritos, song lyrics, and idioms.

As defined in the present study, the term lexical switch refers to the insertion of elements from one language into an identifiable matrix base in another language, as exemplified in Figure 7. For lexical switches, the specific word being switched and its syntactic category were also recorded. The latter designation included the following categories: noun, adjective, verb, pronoun, or other, which included cases such as onomatopoeia and bound morphemes.

Figure 7.

Example of lexical insertion of a Spanish word in an English matrix.

Additionally, the terms quotative switch and attributive switch both refer to instances where words are credited to a specific speaker, with the former referring to situations where the language appears as a direct quote in quotation marks (Figure 8) and the latter referring to cases where the language is attributed to another speaker (Figure 9), for example, in a subordinate clause. Both types exhibited similar patterns in the present data set, and therefore, were collapsed into a single quotative/attributive classification. After determining the type of switch(es) included in each meme, the direction of the switch was categorized as either English-to-Spanish or Spanish-to-English.

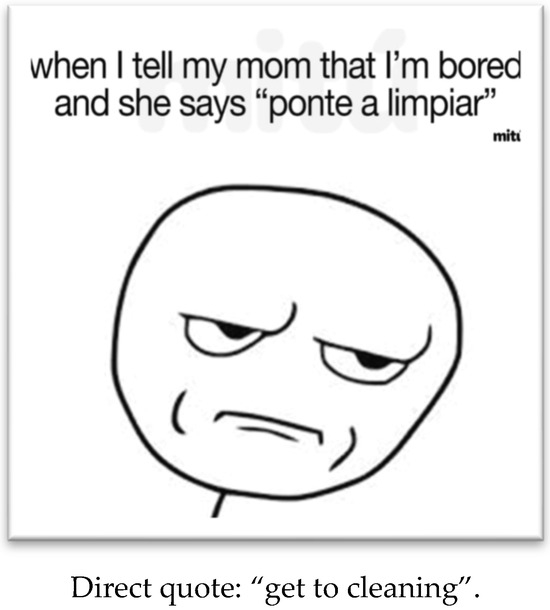

Figure 8.

Example of a Spanish quote in an English matrix attributed to “mother”.

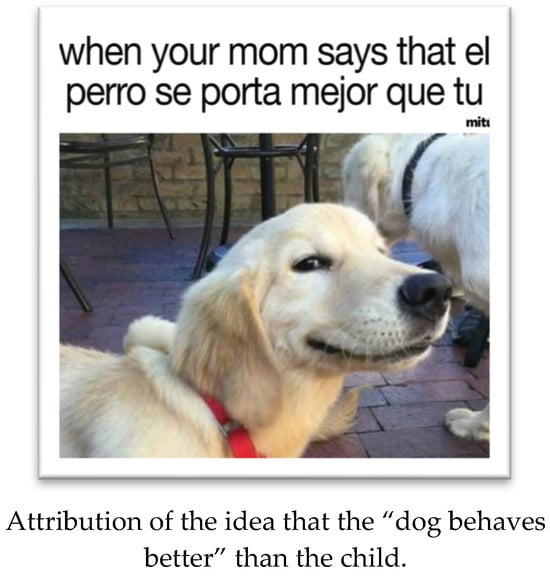

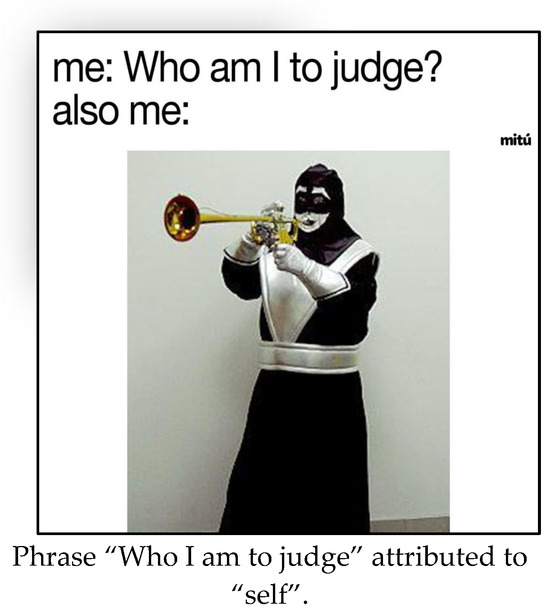

Figure 9.

Example of a Spanish speech attributed to “mother”.

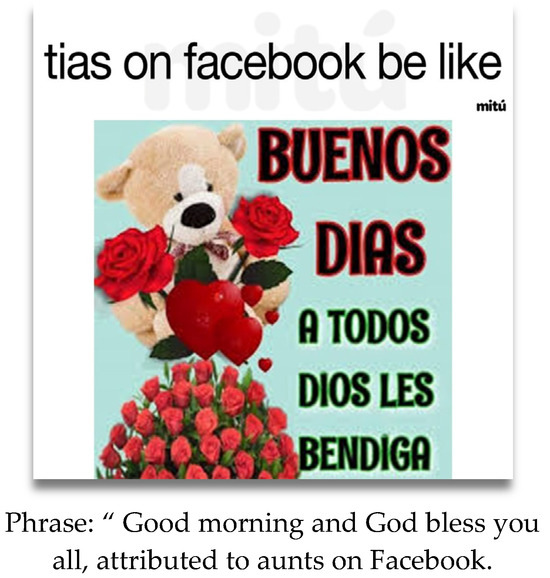

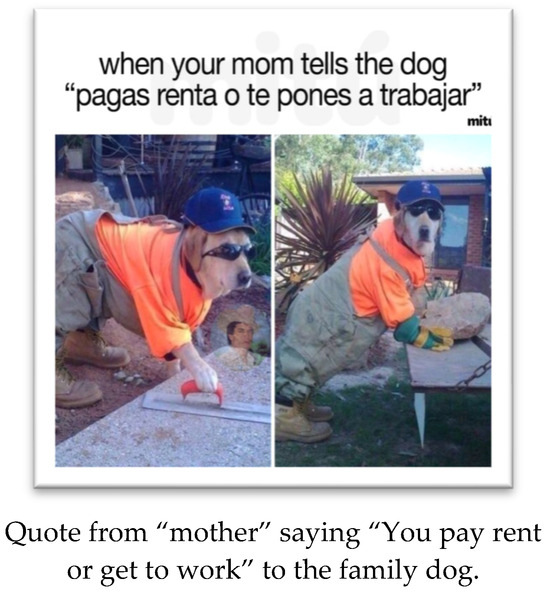

For quotative/attributive switches, the identity of the imagined speaker, or the person that the words were being attributed to, was recorded, e.g., aunts (Figure 10), mom (Figure 11), and me and friend (Figure 12). All the speaker classifications were determined from context and recorded as they appeared in the meme, e.g., “your mom”. Then, speakers were grouped into larger categories such as “mother”.

Figure 10.

Meme with speaker “aunts”.

Figure 11.

Meme with speaker “mother”.

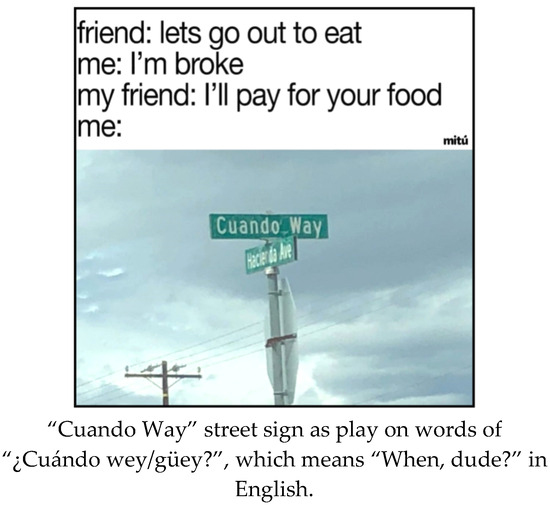

Figure 12.

Meme with imaged speaker “self” and “friend”.

In summary, all the memes were classified according to the switch type, lexical item, and imagined speaker following the procedures described in this section. The following section presents the results based on this coding and shows how these factors play a role in the construction of Latinx identity and the enregisterment of linguistic norms in the online community of mitú.

4. Results and Discussion8

4.1. Overview

I begin by presenting a description of the larger corpus that the memes under analysis are drawn from in order to highlight general trends and to justify my focus on a subset of the data. The corpus is made up of 765 image–text memes. Of these, 35.2% (n = 268) are monolingual, of which 84.0% (n = 225) are in English and 16.0% (n = 43) are in Spanish. Additionally, 3.1% (n = 24) of the memes contained Spanish-origin words that have been lexicalized in English, and therefore, could not be definitively attributed to either language (e.g., tequila, taco, and piñata), and 7.1% (n = 54) included fixed phrases (e.g., song lyrics and brand names), both of which were excluded from the quantitative analysis. The remaining 54.8% (n = 419) of the memes included a total of 526 instantiations of English–Spanish mixed code, including some cases in which there were multiple codeswitches per meme. Of these, 6.8% (n = 36) are switches from Spanish to English, 92.8% (n = 488) are switches from English to Spanish, and 0.4% (n = 2) are hybrid English–Spanish words, specifically stress-itos (English stress plus a Spanish diminutive suffix) and chikibaby (Spanish chiki, from chiquito ‘small,’ plus English baby). What follows is an analysis of a subset of the total 526 instances of codeswitching, including Spanish lexical insertions and Spanish quotative/attributive switches, which make up 51.3% (n = 270) and 21.7% (n = 114) of the instances of mixed code in the corpus, respectively.

The primacy of mixed code in the corpus reflects the critical roles of both English and Spanish in the enregisterment of U.S. Latinx linguistic patterns. In particular, the collected memes reflect Krogstad and Gonzalez-Barrera’s (2015) findings that 70% of participants of approximately millennial age reported using “Spanglish”. These previous findings, in combination with the frequent use of English and Spanish within a single meme in the present data, illustrate the processes of the enregisterment of these linguistic patterns in virtual social spaces. The following sections will detail the ways in which the patterns of language use in these memes enregister mixed code, cultural artifacts, and Spanish-speaking parents as part of the U.S. Latinx millennial experience, offering the possibility for the construction of a collective identity.

4.2. Lexical Switches

A total of 280 lexical switches were recorded. Of these, 96.4% (n = 270) were Spanish words within an English matrix, with just 3.6% (n = 10) representing English words within a Spanish matrix. A total of 136 unique words are represented in the data, as some words are repeated in multiple memes. The vast majority of the lexical items were nouns, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of Spanish insertions by lexical category.

As previously noted, other research has shown that younger generations tend to switch smaller linguistic elements of the language of their family’s country of origin into the majority language (Bentahila and Davies 1992; Muysken 1997), and these types of switches are frequent in U.S. bilingual media (Mahootian 2005). This pattern holds true in the present data. As noted above, 51.3% (n = 270) of all instantiations of codeswitching in the data were insertions of Spanish lexical items into English matrix clauses. In addition, the prevalence of lexical insertions in these data, namely nominal (89.3%) and adjectival (4.8%) insertions, aligns with previous findings on the lexical categories that are most often inserted (Poplack 1980).

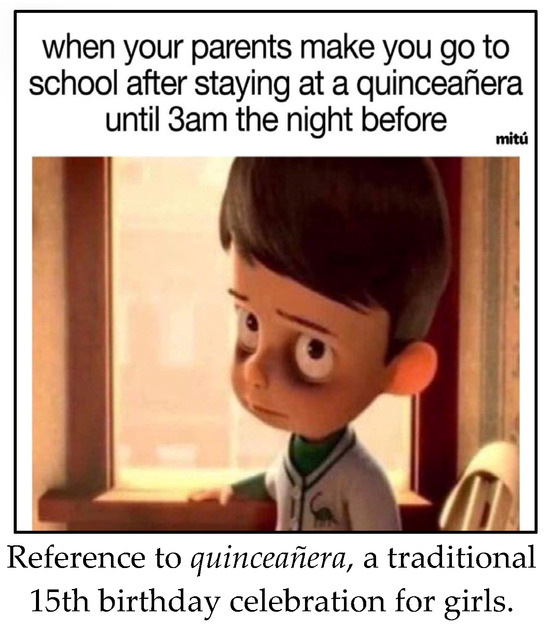

Figure 13 provides a visual representation of the distribution of the different words that constituted the lexical switches found in these memes. In this word cloud, the size of the word corresponds to its frequency of occurrence, i.e., words that are represented in larger text occurred more often than words that are represented in smaller text. For example, chisme (‘gossip’) occurred as a lexical insertion fourteen times, whereas padrinos (‘godparents’), as shown in the lower left corner of the image, occurred only twice. As can be observed in the image, many of the more frequent words represent food items (e.g., elote, a grilled corn dish typical of Mexico, and lomo saltado, a dish made with meat and French fries typical in Peru), kinship terms (e.g., abuela ‘grandmother’ and tía ‘aunt’), and culturally specific artifacts, traditions, or practices (e.g., quinceañera, a traditional 15th birthday celebration for girls, and lotería, a card-based game of chance typical in Mexico).

Figure 13.

Word cloud of lexical switches.

Notably, of the 270 Spanish lexical insertions, 29.6% (n = 80) are food items (Table 2), 35.2% (n = 95) are family or social terms (Table 3), 10.0% (n = 27) are other cultural items (Table 4), and 25.2% (n = 68) belong to other categories.

Table 2.

Lexical insertions related to food.

Table 3.

Lexical insertions related to family and society.

Table 4.

Lexical items related to culture.

The trends found in previous work related to cultural symbolism and bilculturalism have also been illustrated by the present data (De Fina 2007; Gutiérrez 2017; Montes-Alcalá 2007) For example, many of the lexical switches involved traditional food items of Latinx cultural groups, especially food traditional to Mexican–American communities, including agua fresca, carne asada, elote, horchata, pozole, and tamales, among others. Not only can these examples be considered from a utilitarian point of view, given that they have no direct translations in English, but their use invokes a shared set of references that are specific to in-group experiences and cultural practices.9

Relatedly, many familial and kinship terms appear as Spanish words inserted into English clauses in these data, including abuela (‘grandmother’), primo (‘cousin’), tía (‘aunt’), tío (‘uncle’), padre (‘father’), sobrino (‘nephew’), and suegra (‘mother-in-law’). These words provide a clear example that supports Backus’ (2001) proposal that highly specific words, as defined by the norms of the particular community they are used in, are more likely to be inserted. In some cases, as with the previously described food items, Spanish words are used where part of the meaning would be lost in translation. For example, the literal translation of amiguito would be something like ‘little friend’ in English, but in the memes analyzed here, it is used to talk about a romantic partner that is not necessarily serious or exclusive. This recruitment of familial and kinship terms in Spanish instead of using the corresponding terms in English suggests differences in the sociopragmatic meaning of the English and Spanish words. Therefore, upon closer examination, the words that are selected for lexical switches in these memes are not only highly specific and difficult to translate into English, but also reflect cultural practices that are closely connected to identity and are often meant to evoke meaning beyond the semantic meaning of the word (Kosoff 2014; Mahootian 2005).

4.3. Quotative/Attributive Switches

The corpus contained 153 instantiations of language attributed to a speaker in three general configurations: a Spanish quote within an English matrix (Figure 14), an English quote within an English matrix (Figure 15), and a Spanish quote within a Spanish matrix (Figure 16).

Figure 14.

Example of a Spanish quote in an English matrix.

Figure 15.

Example of an English quote in an English matrix.

Figure 16.

An example of a Spanish quote in a Spanish matrix.

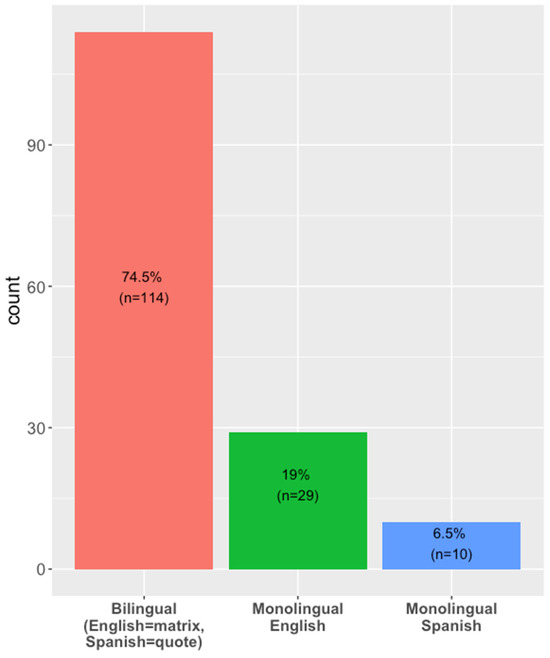

The majority of the quotative/attributive switches in the corpus consisted of Spanish quotes embedded within English matrix clauses (74.5%, n = 114), which are the focus of the present analysis. The remaining 25.5% (n = 39) of the memes based on the quotative template were monolingual, broken down into English quotes within English matrix clauses (19.0%, n = 29), and Spanish quotes within Spanish matrix clauses (6.5%, n = 10). There were no instances of English quotatives embedded in Spanish matrix clauses in the present data. These patterns are visualized in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Distribution of quotative switch types.

The corpus overall shows a strong tendency towards the use of quotatives in Spanish within English matrix clauses. This pattern can be considered reflective of the linguistic environments of many U.S. Latinx millennials (i.e., being surrounded by people who speak Spanish) and a desire to maintain quotes in their original language (Gumperz 1982; Halim and Maros 2014). Additionally, this tendency can work to enregister established patterns of language contact, intergenerational language shift, and the use of Spanglish among millennials (Krogstad and Gonzalez-Barrera 2015).

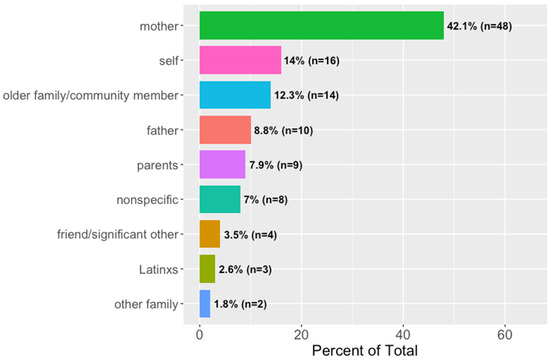

The imagined speakers to whom these English-to-Spanish quotative switches are attributed also follow a distinct pattern, as shown in Figure 18. The vast majority of Spanish quotative switches were attributed to older family members. A total of 42.1% (n = 48) of Spanish quotes were attributed to a “mother” figure, 16.7% (n = 19) were attributed to either “father” or “parents”, and 12.3% (n = 14) were attributed to other older family members (e.g., tía(s), suegra, or abuela) or community members (e.g., señora). Together, the quotes attributed to the aforementioned speakers account for over 70% of the quotative data. This reveals a pattern within these memes of imagined Latinx millennials that share the common ground of a close-knit community in which relatives are not only essential figures, but also speak Spanish. Another 14% (n = 16) were attributed to the “self”, and the remaining 14.9% (n = 17) were attributed to non-specific individuals, Latinxs in general, other family members (e.g., primos ‘cousins’), significant others, or friends.

Figure 18.

Distribution of imagined speakers of Spanish quotatives in English clauses.

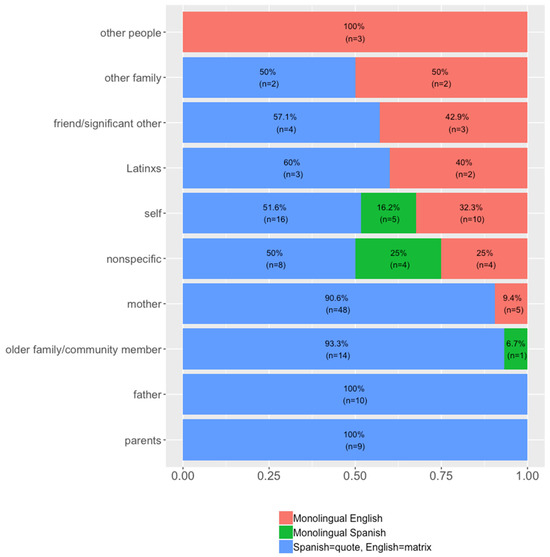

Figure 19 contextualizes these findings by showing the rates of quotes attributed to these imagined speakers across the different quotative templates. First, the quotes attributed to “parents”, “father”, and other family/community members occur categorically in Spanish. Second, the quotes attributed to the “mother” figure occur in Spanish 90.6% (n = 48) of the time and in English 9.4% (n = 5) of the time. Additionally, the figure of the “self” is depicted as frequently speaking both English (32.2%, n = 10) and Spanish (67.8%, n = 21). This reveals a tendency not only to attribute speech to the aforementioned figures, but also to attribute different language patterns to them. Finally, “other people” (e.g., Uber driver or teacher), “other family member” (e.g., cousins or aunts), “friends/significant others”, and “Latinxs”, in general, occur at higher rates in English quotatives.

Figure 19.

Distribution of quotative templates according to imagined by speaker.

While the instances of quotative mixed code in these memes may be, in part, reflective of the documented process of intergenerational language shifts, their messages also rely on more nuanced sociopragmatic and symbolic meanings. A wealth of previous studies have found that particular linguistic forms, in this case, codeswitching, can be used in internet communication to convey in-group membership and construct group identity (Androutsopoulos 2006; Dorleijn and Nortier 2009; Zappavigna 2012; inter alia). In the case of the present data, the expression of culturally specific lexical items and Spanish quotes attributed to older family members works to establish linguistic and cultural patterns that communicate the sociopragmatic meaning of being in an environment where Spanish is used, constructing a collective imagination of the U.S. Latinx millennial experience.

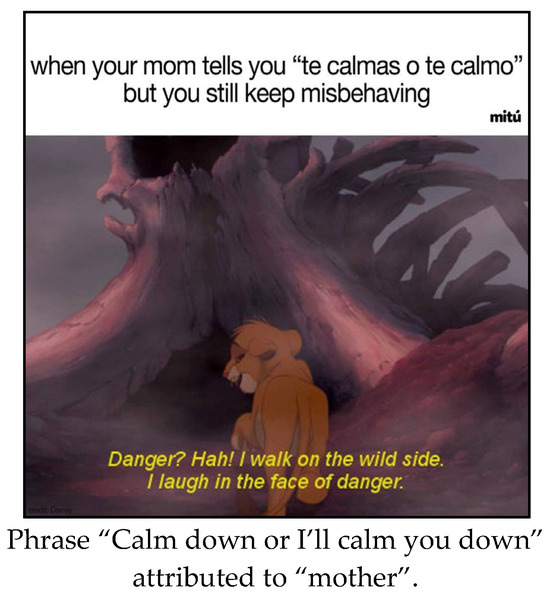

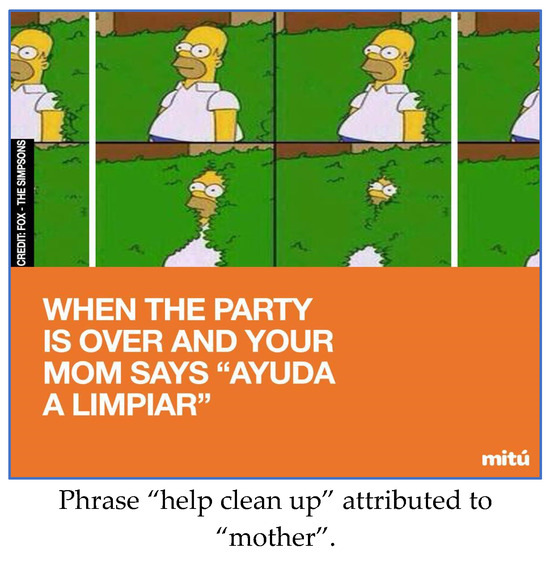

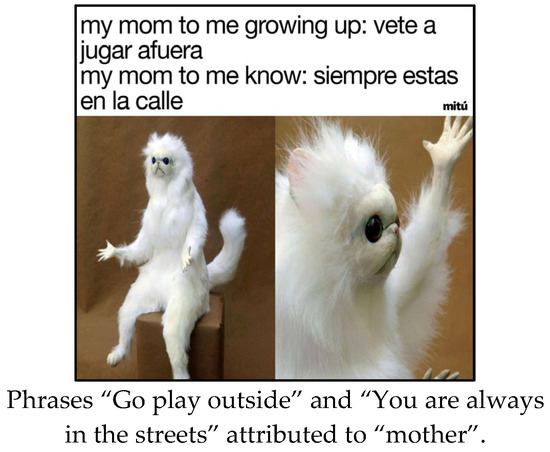

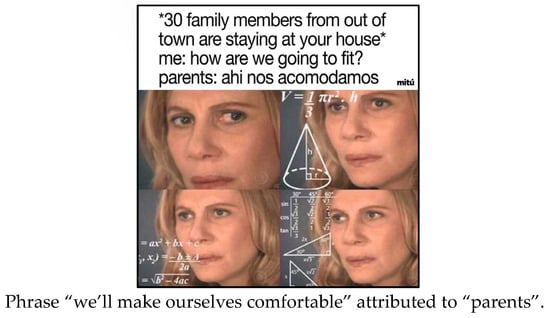

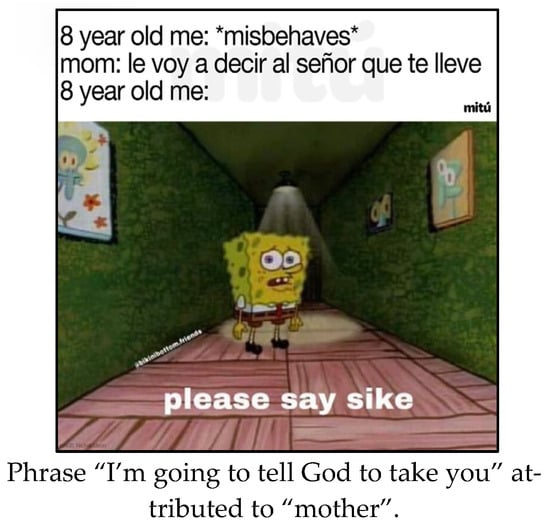

The communicative capacity of these memes relies on the construction of characterological figures and cultural symbolism to ideologically link the linguistic features employed within them to abstract social categories in a process of enregisterment (Agha 2003). The creation of these figures relies on the shared experiences of U.S. Latinx millennials, as previously described, but also uses the memetic template to create patterns of expression that can become enregistered through repetition and humor. One such characterological figure employed in these memes is the “mother”, who is constructed as a figure whose primary language of expression is Spanish. In addition, the content of the memes where language is attributed to the “mother” figure follow specific patterns, in particular, the frequency of activities related to domesticity and raising children. For example, Figure 20 depicts the figure of the “mother” reprimanding a child for misbehavior, and Figure 21 shows the “mother” telling a child to contribute to a group clean up. Figure 22 depicts an example of a “mother” questioning her child’s behavior at different life stages; first, at a younger age, the child is told to go and play outside, and second, at an older age, the child is told that they spend too much time out and about.

Figure 20.

Meme depicting a mother reprimanding child.

Figure 21.

Meme depicting a mother telling child to do chores.

Figure 22.

Meme depicting a mother questioning a child’s behavior.

As in Johnstone’s (2011) description of the characterological figures in radio skits, the depictions of motherhood displayed in these memes have the potential to enregister language forms within more than one cultural schema, because what is salient depends on the listener or, in this case, the internet audience. For example, for U.S. Latinx millennials who grew up with Spanish-speaking mothers, this pattern can serve to further enregister the relationship between use of the Spanish language and motherhood, not unlike the abuela figure described in Gutiérrez (2021). More broadly, even for those audience members for whom there is not a strong personal connection between speaking Spanish and motherhood, the content of the memes themselves may enregister certain practices stereotypically associated with motherhood,10 such as domestic activities and monitoring children’s behavior. In this way, both what is depicted in these memes and how it is depicted play a role in (re)enregistering the “mother” figure for U.S. Latinx millennials.

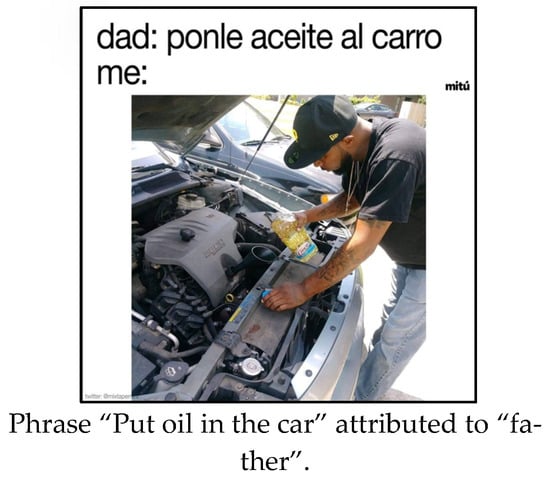

The present data show similar patterns, albeit not as frequently, related to the construction of the characterological figure of the “father”. As with the “mother” figure, the “father” is characterized as speaking Spanish. Regarding the content of the memes related to the “father”, they often depict stereotypically masculine behaviors, such as protectiveness, fixing things, and a hard emotional exterior that can be softened. For example, Figure 23 portrays the figure of the “father” secretly supervising his teen or adult female offspring, who has a male friend in their room, and Figure 24 shows a “father” figure telling their child to replace the oil in their car. Lastly, Figure 25 depicts a scenario in which the “father” figure sternly states that he does not want a dog, but later falls in love with it. As with the characterological figure of the “mother” described above, the repeated depiction of “father” as using Spanish can enregister or re-enregister these language forms, depending on the audience.

Figure 23.

Meme depicting a father supervising child.

Figure 24.

Meme depicting a father in relation to chores.

Figure 25.

Meme depicting a father’s changing attitude towards a family dog.

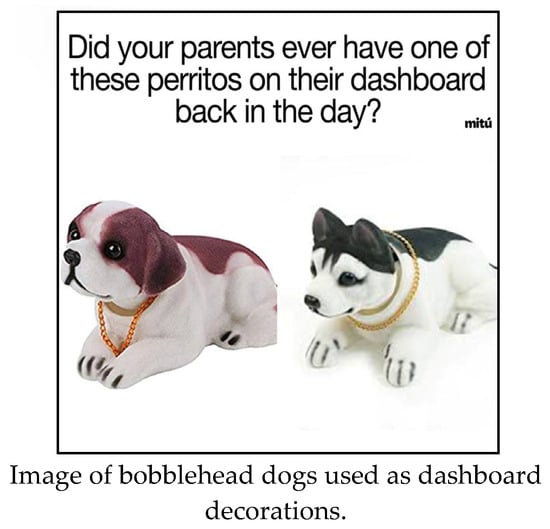

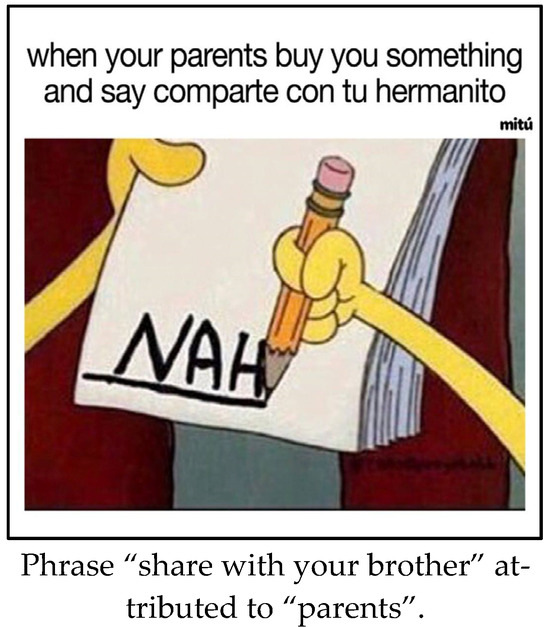

This frequent depiction of the Spanish-speaking “mother” and “father” works to construct the U.S. Latinx millennial as having Spanish-speaking parents. This is supported by representations such as Figure 26, where both parents are portrayed as speaking Spanish, and the continued reiteration of this pattern in successive memes enregisters the relationship between these figures and the use of the Spanish language. In addition to the use of Spanish, memes such as Figure 26, which depict the imagined speakers as having large extended families, function to further construct strong family ties as part of the U.S. Latinx millennial identity. These memes represent several different behaviors that are attributed specifically to the parents of Latinx millennials, including referring to particular aesthetics (Figure 27), engagement in cultural activities (Figure 28), and sayings (Figure 29).

Figure 26.

Meme depicting parents using Spanish.

Figure 27.

Meme depicting parents’ aesthetics.

Figure 28.

Meme depicting cultural activities.

Figure 29.

Meme depicting parents’ sayings.

Finally, the last characterological figure salient in these data is the “self”, which is portrayed as speaking both English and Spanish, constructing the Latinx millennial as someone who is bilingual. For example, the “self” figure is depicted using English in Figure 30,11 using Spanish in Figure 31, and codeswitching in Figure 32. In fact, the text of the meme in Figure 32 points directly to the idea of seeing oneself in a meme and identifying with it. These examples demonstrate how the characterological figure of the “self” works to further enregister U.S. Latinx millennial use of both English and Spanish and provides the possibility for followers to personally identify with internet content.

Figure 30.

Meme depicting English used by the “self” figure reacting to “mother’s” scolding in Spanish.

Figure 31.

Meme depicting use of Spanish by the “self” figure.

Figure 32.

Meme depicting a codeswitch by the “self” figure.

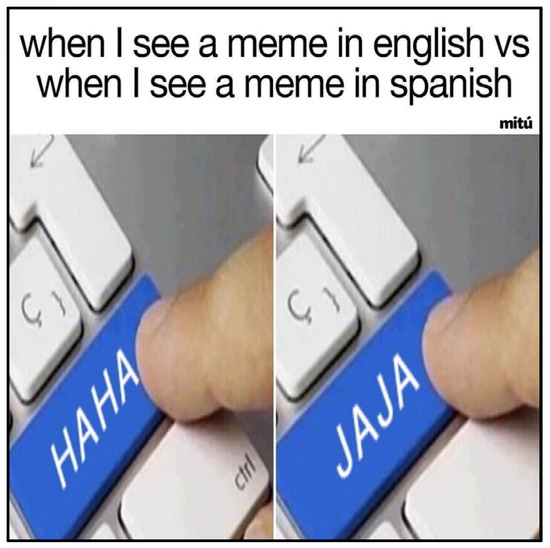

The bilingual status of U.S. Latinx millennials is constructed through the use of English and Spanish both separately and together, as well as examples that demonstrate the ability to adapt one’s mode of expression based on social context. Consider Figure 33, where the U.S. Latinx millennial fluidly uses English and Spanish depending on the context. The option on the left side shows the orthographic representation of laughing in English, “haha”, while the option on the right side shows the orthographic representation of laughing in Spanish, “jaja”.

Figure 33.

Spanish and English laughing.

The characterological figures of “mother,” “father,” “parents,” and “self” are constructed within these memes not only individually, but also in contrast to each other. Looking back at Figure 30, we see that the “parent” figures speak in Spanish, and the child, the U.S. Latinx millennial, replies in English. Another example of this is shown in Figure 34, where the “mother” speaks in Spanish, but the “self” speaks in English. Interactions like these construct the U.S. Latinx millennial in opposition to the previous Spanish-dominant generation and subsequently align with Gutiérrez’s (2021) analysis that the abuela figure on the Pero Like channel illustrates generational differences and Latinx millennials’ experiences. This example not only contrasts the difference in language use of the “mother” and the “self” figures, but also highlights generational differences in media consumption. The television program mentioned, Primer Impacto, is a weekday evening news program produced by the Spanish-language network Univisión that first aired in the 1990s and is known for sensationalist stories.

Figure 34.

Meme depicting use of Spanish by a mother and English by the child.

The way that the memes analyzed in the present project are instantiated is a product of several factors, including the norms of internet communication, the social and linguistic experiences of Latinx millennials engaged with the mitú platform, and the characterological figures that they construct in the enregisterment process. These memes tend to follow similar structural patterns, such as the insertion of culturally specific Spanish words into English matrices and the use of Spanish quotatives attributed to older family members. These norms appear to represent a sort of template, which is a common characteristic of successful internet memes (Lankshear and Knobel 2007; Zappavigna 2012). Importantly, part of the success of a particular memetic template is its relevance to the experiences and identities of those who engage with it. The content and structure of the memes posted to the mitú page are not random, but are part of complex, interconnected networks that are bound to a specific context and require a particular set of referential knowledge to be wholly understood (see Miltner 2014), which also speaks to the indeterminacy of social meaning in general. More specifically, these memes tap into shared popular culture experiences (Lankshear and Knobel 2007) via their references to foods, traditions, and familial relationships that are culturally specific to Latinxs in the United States. In other words, the memes investigated in the present project not only follow widespread internet norms for the creation of memes but are also constructed around content that is specific to mitú’s primary community of users, Latinx millennials in the United States.

5. Conclusions

The data presented here illustrate that the representations and use of language in English–Spanish bilingual memes posted by mitú are not static or isolated, but rather are connected to and participate in a larger sociopolitical dynamic. In particular, the content of these memes, on the one hand, is representative of the cultural and linguistic norms shared by many U.S. Latinx millennials, and, on the other hand, works to construct a particular brand of U.S. Latinx millennial identity that is based on a specific set of social signifiers. The use of culturally specific lexical insertions and the development of characterological figures through quotatives construct and reinforce a specific kind of experience of Latinx millennial identity in the U.S., including being bilingual, having Spanish-speaking parents, and having strong ties to Latinx culture. Overall, the motivations for and outcomes of the content of the memes posted to the mitú Facebook page are multi-faceted and dynamic. These memes allow the representation of Spanish–English language contact and multicultural identity on a social platform and work to construct U.S. Latinx millennial identity through the enregisterment of particular linguistic forms and cultural behaviors.

Looking forward, the findings of this project can be applied to a variety of contexts. Dovchin’s (2022) work on translingual discrimination finds that the delegitimation of the practices of multilingual individuals can have wide-reaching social repercussions with regard to education, employment opportunities, and conceptions of identity. Bucholtz et al.’s (2014) framework for sociolinguistic justice presents potential recourse to these processes of delegitimation and the social consequences that result from them. Specifically, this framework calls for (1) the valorization and legitimation of the linguistic resources and practices of minoritized communities, (2) access to all varieties of language that these individuals desire to use, and (3) the affirmation of individuals’ own linguistic repertoires. In particular, both Dovchin’s and Bucholtz’s work is applied to multilingual education contexts, stressing the importance of sociolinguistic justice in education. While the present study does not specifically address educational contexts, it may be a useful resource for linguists, educators, and communities alike by showcasing online community building and reaffirming the importance of language variation, multilingualism, and their connection to identity construction.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the data collection methodology was based on the observation of public behavior. The information obtained is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that the identity of the human subjects cannot readily be ascertained, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects (Federal Code of Regulations Title 45, Subchapter A, Part 26, section (d)(2)(i)).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Anna Babel for her support of this project at its inception. I am grateful for the insightful feedback, dedication, and patience of Whitney Chappell, Sonia Barnes, and three anonymous reviewers who all helped me improve this work. Any remaining errors are my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | https://www.facebook.com/wearemitu (accessed on 1 September 2019). |

| 2 | I use the term “Latinx” to be inclusive to gender non-conforming and non-binary individuals, as has increasingly been the tradition in academic writing. As used in this paper, the term is meant to include Latinas, Latinos, Latines, and Latin@s, and anyone who identifies as being of Latino origin. See Guidotti-Hernández (2017) for further discussion. |

| 3 | Not only does the content posted to mitú lend itself to a multitude of areas of analysis (e.g., Morrison 2020), but the images in the memes in conjunction with the linguistic material are also worthy of future multimodal discursive analysis, which involves multiple modes of communication (such as visual and spatial) in conjunction with written text. |

| 4 | https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/mitus-beatriz-acevedo-wants-be-voice-millennial-generation-n396381 (accessed on 1 November 2019). |

| 5 | While it is difficult to define precisely what constitutes a millennial, a report from the Pew Research Center (Dimock 2019) categorized those born between 1981 and 1996 as millennials, which would have made them from 23 to 38 years old at the time the data were collected for this project. This means that they represent a large portion of the age range of the listed target audience for the page. According to data from the 2014 American Community Survey, approximately 14.6 million Latinxs are considered millennials, accounting for 26% of the Latinx population in the U.S. (Patten 2016). A 2019 report from the Pew Research Center (Perrin and Anderson 2019) indicates that individuals from the millennial generation fall squarely within the age range that has the highest rate of active Facebook users. For example, in 2019, 84% of 25 to 29 year olds and 79% of 30 to 49 year olds were active users, as compared to 76% of 18 to 24 year olds, 68% of 50 to 64 year olds, and just 46% of those aged 65 and older. While there is no way to verify with absolute certainty the identities of consumers of online media (Varis and Blommaert 2015), much of the content posted to mitú’s page appears to be aimed, at least in part, at this expressed target audience. |

| 6 | Still, it is critical to note that “following” does not necessarily entail interaction (Zappavigna 2014, p. 156) due to the fact that users have the option to “mute” and “see less” of the content posted by Facebook pages they follow. |

| 7 | All the memes presented visually in this work are meant to be illustrative of larger trends in the data set as a whole. A full catalog of all 765 memes can be provided upon request. |

| 8 | I acknowledge my position as a white, non-Latina woman who has only ever experienced Spanish through the lens of white, English speaking privilege. I must note that despite having worked with Spanish speakers and Latinx communities throughout my life and career, I am writing about experiences that are not my own. What I am able to offer are my insights into this particular phenomenon based on my knowledge of language and society. I take full ownership of any errors, inaccuracies, and biases presented herein, and acknowledge that my interpretation of these data may be flawed and/or not represent the experiences of all U.S. Latinx individuals. |

| 9 | Future work would do well to investigate the degree to which Facebook users who interact with the meme content posted by mitú feel that it is derived from real-life connections to and experiences of U.S. Latinx millennial identity via the analysis of likes, shares, comments, etc. |

| 10 | Not only is the use of Spanish enregistered with these portrayals of “mother” and “father”, the representations of the behaviors associated with each (re)enregister and reinforce stereotypical gender roles. Though beyond the scope of the present analysis, the ways in which the “mother” and “father” are associated with traditional gender roles are worthy of investigation in their own right. For review of previous work on gender roles in U.S. Latinx communities and the cultural systems that underlie them, see Raffaelli and Ontai (2004) and Miville et al. (2017). For previous work related to the portrayal of gender roles in mitú’s content, see Morrison (2020) and Wallace et al. (2020). Gutiérrez (2021) notes that the characters featured by content creators on the Pero Like channel similarly mimic stereotypical behavior as a means of satire. |

| 11 | As an interesting note, the use of the word sike (also written psych) in Figure 30, a slang interjection meaning ‘just kidding’ that gained widespread popularity in the 1980s and 1990s (Green 2008, p. 1038), further reinforces the millenial age group as one of mitú’s target audiences. |

References

- Agha, Asif. 2003. The Social Life of Cultural Value. Language and Communication 23: 231–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, Asif. 2005. Voice, Footing, Enregisterment. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15: 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, Asif. 2006. Language and Social Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2006. Introduction: Sociolinguistics and Computer-Mediated Communication. Journal of Sociolinguistics 10: 419–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2015. Networked Multilingualism: Some Language Practices on Facebook and their Implications. International Journal of Bilingualism 19: 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backus, Ad. 2001. The Role of Semantic Specificity in Insertional Codeswitching: Evidence from Dutch-Turkish. In Codeswitching Worldwide II. Edited by Rodolfo Jacobson. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 125–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backus, Ad. 2015. A usage-based approach to code-switching: The need for reconciling structure and function. Code-switching Between Structural and Sociolinguistic Perspectives 43: 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baym, Nancy K. 1995. The Emergence of Community in Computer-Mediated Communication. In CyberSociety: Computer-Mediated Communication and Community. Edited by Stephen G. Jones. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 138–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bentahila, Abdelâli, and Eirlys E. Davies. 1992. Code-Switching and Language Dominance. In Advances in Psychology. Edited by Richard Jackson Harris. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 443–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, Susan J. 1999. The Meme Machine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholtz, Mary, Audrey Lopez, Allina Mojarro, Elena Skapoulli, Chris VanderStouwe, and Shawn Warner-Garcia. 2014. Sociolinguistic Justice in the Schools: Student Researchers as Linguistic Experts. Language and Linguistics Compass 8: 144–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, M. Sidury. 2015a. ‘A ondi queras’: Ranchero Identity Construction by U.S. Born Mexicans on Facebook. Journal of Sociolinguistics 19: 688–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, M. Sidury. 2015b. Mexicanness and Social Order in Digital Spaces: Contention Among Members of a Multigenerational Transnational Network. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 37: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, Richard. 1976. The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Fina, Anna. 2007. Code-Switching and the Construction of Ethnic Identity in a Community of Practice. Language in Society 36: 371–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimock, Michael. 2019. Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Dorleijn, Margreet, and Jacomine Nortier. 2009. Code-Switching and the Internet. In The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Code-Switching. Edited by Brenda Bullock and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 127–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovchin, Sender. 2022. Translingual Discrimination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, Noam, Limor Shifman, and Zohar Kampf. 2016. “It Gets Better”: Internet Memes and the Construction of Collective Identity. New Media and Society 18: 1698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, Zane. 2007. Enregisterment and Appropriation in Javanese-Indonesian Bilingual Talk. Language in Society 36: 511–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Jonathon. 2008. Chambers Slang Dictionary. Edinburgh: Chambers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti-Hernández, Nicole M. 2017. Affective Communities and Millennial Desires: Latinx, or Why My Computer Won’t Recognize Latina/o. Cultural Dynamics 29: 141–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumperz, John J. 1982. Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, Arcelia. 2021. Pero Like and mitú: Latina Content Creators, Social Media Entertainment, and the Politics of Latinx Millenniality. Feminist Media Histories 7: 80–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, Cynthia. 2017. Exploring Latino Acculturation and Code-Switching through Self-Portraiture (Selfies). Master’s thesis, Notre Dame de Namur University, Belmont, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Halim, Nur Syazwani, and Marlyna Maros. 2014. The Functions of Code-Switching in Facebook Interactions. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 118: 126–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, Lars. 2006. Codeswitching on the Web: English and Jamaican Creole in E-Mail Communication. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Miyako. 2003. The Listening Subject of Japanese Modernity and His Auditory Double: Citing, Sighting and Siting the Modern Japanese Woman. Cultural Anthropology 18: 156–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, Barbara. 2011. Dialect Enregisterment in Performance. Journal of Sociolinguistics 15: 657–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, Barbara. 2017. Characterological Figures and Expressive Style in the Enregisterment of Linguistic Variety. In Language and a Sense of Place: Studies in Language and Region. Edited by Chris Montgomery and Emma Moore. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kecskes, Istvan, Olga Obdalova, Ludmila Minakova, and Aleksandra Soboleva. 2018. A Study of the Perception of Situation-Bound Utterances as Culture-Specific Pragmatic Units by Russian Learners of English. System 76: 219–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosoff, Zoë. 2014. Code-switching in Egyptian Arabic: A sociolinguistic analysis of twitter. Al-ʿArabiyya: Journal of the American Association of Teachers of Arabic 47: 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad, Jens Manuel, and Ana Gonzalez-Barrera. 2015. A Majority of English-Speaking Hispanics in the US Are Bilingual. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2015/03/24/a-majority-of-english-speaking-hispanics-in-the-u-s-are-bilingual (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Lankshear, Colin, and Michele Knobel. 2007. Researching New Literacies: Web 2.0 Practices and Insider Perspectives. E-Learning and Digital Media 4: 224–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacSwan, Jeff. 2014. Grammatical Theory and Bilingual Codeswitching. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahootian, Shahrzad. 2005. Linguistic Change and Social Meaning: Codeswitching in the Media. International Journal of Bilingualism 9: 361–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltner, Kate M. 2014. “There’s No Place for Lulz on LOLCats”: The Role of Genre, Gender, and Group Identity in the Interpretation and Enjoyment of an Internet Meme. First Monday 19: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miville, Maria L., Narolyn Mendez, and Mark Louie. 2017. Latina/o Gender Roles: A Content Analysis of Empirical Research from 1982 to 2013. Journal of Latina/o Psychology 5: 173–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes-Alcalá, Cecilia. 2007. Blogging in Two Languages: Code-Switching in Bilingual Blogs. In Selected Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 162–70. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Hannah Grace. 2020. Snapchat Page Mitú: Challenging the Patriarchy? Or just Obsessing over Flaming Hot Cheetos? Prose Studies 41: 253–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muysken, Pieter. 1997. Code-Switching Processes: Alternation, Insertion, Congruent Lexicalization. In Language Choices: Conditions, Constraints, and Consequences. Edited by Martin Pütz. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 361–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muysken, Pieter. 2000. Bilingual Speech: A Typology of Code-Mixing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Myers-Scotton, Carol, and Janice L. Jake. 1995. Matching Lemmas in a Bilingual Language Competence and Production Model: Evidence from Intrasentential Code Switching. Linguistics 33: 981–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortman, Jennifer M., and Hyon B. Shin. 2011. Language Projections: 2010 to 2020; Census Working Papers. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/2011/demo/2011-Ortman-Shin.html (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Patten, Eileen. 2016. The Nation’s Latino population Is Defined by Its Youth. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2016/04/20/the-nations-latino-population-is-defined-by-its-youth (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Perrin, Andrew, and Monica Anderson. 2019. Share of U.S. Adults Using Social Media, Including Facebook, Is Mostly Unchanged since 2018. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Poplack, Shana. 1980. Sometimes I’ll Start a Sentence in Spanish Y TERMINO EN ESPAÑOL: Toward a Typology of Code-Switching. Linguistics 18: 581–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplack, Shana. 1993. Variation Theory and Language Contact. In American Dialect Research. Edited by Dennis R. Preston. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 251–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaelli, Marcela, and Lenna L. Ontai. 2004. Gender Socialization in Latino/a Families: Results from Two Retrospective Studies. Sex Roles 50: 287–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifman, Limor. 2013. Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a Conceptual Troublemaker. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 18: 362–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, Lauren. 2010. Enregistering Internet language. Language in Society 39: 457–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2015. American Community Survey. Available online: https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/data-profiles/2015 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Varis, Piia, and Jans Blommaert. 2015. Conviviality and Collectives on Social Media: Virality, Memes, and New Social Structures. Multilingual Margins: A Journal of Multilingualism from the Periphery 2: 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, Ryan, Olga Lazitski, Kirsi Cheas, Maiju Kannisto, Noora Juvonen, Carolyn Nielsen, and Mark Poepsel. 2020. “We are the 200%”: How Mitú Constructs Latino American Identity Through Discourse. International Symposium on Online Journalism 10: 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Li. 2011. Moment Analysis and Translanguaging Space: Discursive Construction of Identities by Multilingual Chinese Youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics 43: 1222–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Li. 2018. Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language. Applied Linguistics 39: 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Li, and Angel M. Y. Lin. 2019. Translanguaging Classroom Discourse: Pushing Limits, Breaking Boundaries. Classroom Discourse 10: 209–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolford, Ellen. 1983. Bilingual code-switching and syntactic theory. Linguistic Inquiry 14: 520–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zappavigna, Michele. 2012. Discourse of Twitter and Social Media: How We Use Language to Create Affiliation on the Web. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Zappavigna, Michele. 2014. Coffeetweets: Bonding Around the Bean on Twitter. In The Language of Social Media: Identity and Community on the Internet. Edited by Philip Seargeant and Caroline Tagg. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 139–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).