Professional Development of Pre-Service Language Teachers in Content and Language Integrated Learning: A Training Programme Integrating Video Technology

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Professional Development in CLIL: Integrating Video-Based Technology Programmes

3. Methods

3.1. The Study Context

3.2. Participants

3.3. A Video-Based Technology Training Programme

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Video for Reflective Teaching and Improvement of Practice

[Extract 1]: … because when you are explaining or you are the practical session, you are not really aware of what you are doing … it is like disconnecting and deliver a speech … because you have everything prepared and you feel the necessity to finish as soon as possible, after all, when you watch that in the video, you notice about the mistakes …/Porque cuando tú estás exponiendo, o estás en la sesión práctica, no eres realmente consciente de lo que estás haciendo … es como que desconectas y lo sueltas … porque lo tienes tan preparado que necesitas soltarlo cuanto antes para como quitártelo del medio, al fin y al cabo, y cuando lo ves en vídeo, te das cuenta de los errores …

[Extract 2]: … because it helps you to enhance. You see your mistakes and you can learn about solving them./… porque te ayuda a mejorar. Ves tus errores y puedes aprender para solucionarlo.

[Extract 3]: … you do not notice your mistakes … but when you really watch yourself talking and doing the simulation of the lesson, the truth is that you see yourself, do you know? you must improve …/no te ves tú tus propios fallos y tus cosas pero cuando tú te ves realmente hablando y dando como si fuera una clase, la verdad que te ves ¿sabes? Que tienes que mejorar tus cosas …

[Extract 4]: … lots of mistakes that you make unconsciously and then, when you realize about that you say: I can correct that. And, in the following session, you try to correct them, it might be right or wrong, but you are aware of that error, and you have to work on that. It is becoming aware of your own teaching./De muchísimos errores que cometes no eres consciente y después cuando lo ves dices: esto puedo corregirlo. Y en la siguiente práctica pues intentas corregirlo, te sale bien o no, pero ya eres consciente de ese error y que tienes que trabajar en eso. Es tomar conciencia de tu propia docencia.

[Extract 5]: … because you realize the things you thought you had a lot of confidence, and then it seems that you hadn’t; social skills, the way you look at your students, the way you talk to them, adapt yourself to their level. … porque te das cuenta de las cosas en las que tu pensabas que tenías muchísima seguridad, y luego parece, que no; habilidades sociales, como miras a tu alumnado, como le hablas, adaptarte a su nivel.

[Extract 6]: But when you are speaking in class, I think I were speaking too quickly, and the pronunciation was not good speaking in that way. Then, when you watch the video you notice that./Pero cuando estás en clase exponiendo, yo creo que lo decía muy rápido, y la pronunciación al decirlo tan rápido no era buena. Entonces luego al ver el vídeo te das cuenta de eso.

[Extract 7]: I think that it is a useful tool because it is handy. It is easy to use. I think it is a suitable tool./Yo creo que es una herramienta útil en el sentido de que es muy práctica. Y es fácil de usar. Yo creo que si es una herramienta apropiada.

[Extract 8]: I liked it a lot because you can go forward and back in the video, you can make notes, check what your partners have commented, things that I have commented …/Me gustó un montón porque, al poder darle para adelante para atrás, puedes añadir notas, ves lo que me han escrito mis compañeras, lo que había escrito yo …

4.2. Using the Additional Language in CLIL

[Extract 9]: Or see pronunciation mistakes that you have made when delivering the lesson …/O ver errores de pronunciación que has tenido durante la exposición …

[Extract 10]: My colleagues and I, what we saw was that there were a lot of expressions and things that we did not realize … I don’t know, it is something very ordinary but we do not see that …/Hombre mis compañeros y yo lo que vimos era eso que, había un montón de expresiones y de cosas que no caíamos … no sé, que es algo muy cotidiano pero que no vemos …

[Extract 11]: our concern is, are we qualified to use a second language? Do we know to use L1 to enrich the L2? We have a lot of concerns that are there …/… nuestra preocupación es ¿estamos a la altura en la lengua? ¿sabemos usar la lengua 1 para enriquecer la lengua 2? Tenemos muchas inquietudes que están ahí …

[Extract 12]: … we had a classmate who in our presentation, he wanted to present … but because he is better at doing the presentation part because he felt more insecure when giving the contents in English …/teníamos un compañero que en nuestra presentación, él quería presentar … pero porque a él se le da mejor hacer la parte de presentación porque él se sentía más inseguro al dar los contenidos en inglés …

[Extract 13]: … we need to make better because we were blocked … perhaps the pronunciation … we need to practice more English to give a lesson …/necesitamos mejorar porque es que nos quedamos pillados … a lo mejor la pronunciación … que necesitamos practicar más el inglés a la hora de dar una clase …

[Extract 14]: … We need to enhance our level of English a lot because you must be spontaneous./Y eso, y la mayoría necesitamos mejorar nuestro nivel de inglés bastante porque es que tienes que tener mucha espontaneidad.

[Extract 15]: … we worry too much about speaking well instead of doing things good. You … in class you do not have to be perfect, no one speak a language perfect even in their native language … We are worried about pronouncing things correctly and maybe we run out of time, or we do not do the activity the way we wanted to do it or …/… nos preocupamos demasiado por hablar bien, en vez de por hacer las cosas bien. Tu … en clase no tienes por qué ser siempre perfecto, nadie habla perfecto siempre ni en tu propio idioma, … Estamos preocupados por pronunciar bien y a lo mejor se nos va el tiempo o, no hacemos la actividad como queríamos hacerla o …

[Extract 16]: … on the other hand, contents of … you should adapt the contents to the learners, not only to the first level as this can be different in other courses./ por otra parte, los contenidos de, que tienes que adaptarlo también a los alumnos, no solo a un primero, pues un primero puede ser muy distinto en varios cursos.

[Extract 17]: Yes, what kind of expressions we are going to use if we want the students to learn …/Sí, qué expresiones vamos a utilizar si queremos que aprendan [los estudiantes].

4.3. Video as a Tool to Understand the CLIL Approach

[Extract 18]: … because you notice that CLIL is something more than giving an English lesson. It is building concepts from different perspectives …/porque te das cuenta de que AICLE es algo más que dar una clase en inglés. Es construir conceptos desde distintas perspectivas.

[Extract 19]: And to see that, to differentiate from one more class and a class of … a class of content and a foreign language that is completely different./Y de ver que, diferenciar de una clase más y una clase de … que sea de contenido y lengua extranjera que es completamente diferente.

[Extract 20]: And also, fear of falling into the different practices of “I’m going to give a list of English vocabulary, and I have already done my CLIL lesson … we want to avoid that./Y también miedo a caer en las distintas prácticas de “voy a dar una lista de vocabulario en inglés y ya he hecho mi AICLE” … queremos evitar eso.

[Extract 21]: There are times that we were delivering the class, and it seemed like we were giving a vocabulary lesson rather than a class on specific content. Then, how I explain myself … we focused a lot, for example, on the present simple, when what we should be giving is some content within English …/Hay veces que estábamos dando la clase y parecía que estábamos dando una clase de vocabulario y no una clase de un contenido concreto. A ver, cómo me explico, nos centrábamos mucho por ejemplo en el presente simple, cuando lo que tendríamos que estar dando es unos contenidos dentro del inglés …

[Extract 22]: … furthermore, as it was the CLIL syllabus, I have never studied CLIL before and … the truth is that it helped me to focus a little bit more on what CLIL was./… además, como era la asignatura de CLIL, yo nunca había tocado CLIL y me ha … la verdad es que me ha enfocado un poco más sobre lo que era CLIL.

[Extract 23]: … then, although in the theoretical classes I tried to understand it, it was in the practical lessons when I realized what it was. When I watched the video and see how we, my classmates too, had adapted the material, how they had made resources, all of that helped us unite what CLIL meant./… entonces, a pesar de que en las clases teóricas intentaba entenderlo, fue en las prácticas cuando me di cuenta de lo que era. Y, a la hora de ver el vídeo y ver cómo habíamos, mis compañeros también, cómo habían adaptado el material, cómo habían hecho recursos, todo eso nos ayudó a cohesionar lo que significaba CLIL.

[Extract 24]: … previously I did not know anything … now I have taken the subject and the practical lessons plus watching themselves on the video, see the activities that have done, that you have prepared, how you have adressed the contents, objectives, and all of that, it helps you to understand how CLIL works./… anteriormente no sabía nada, entonces ahora al hecho de dar la asignatura y hacer esas prácticas y verte en el vídeo y ver las actividades que has hecho, que has preparado, como has tratado los contenidos, los objetivos y todo eso, te ayuda a conocer un poco más cómo funciona.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

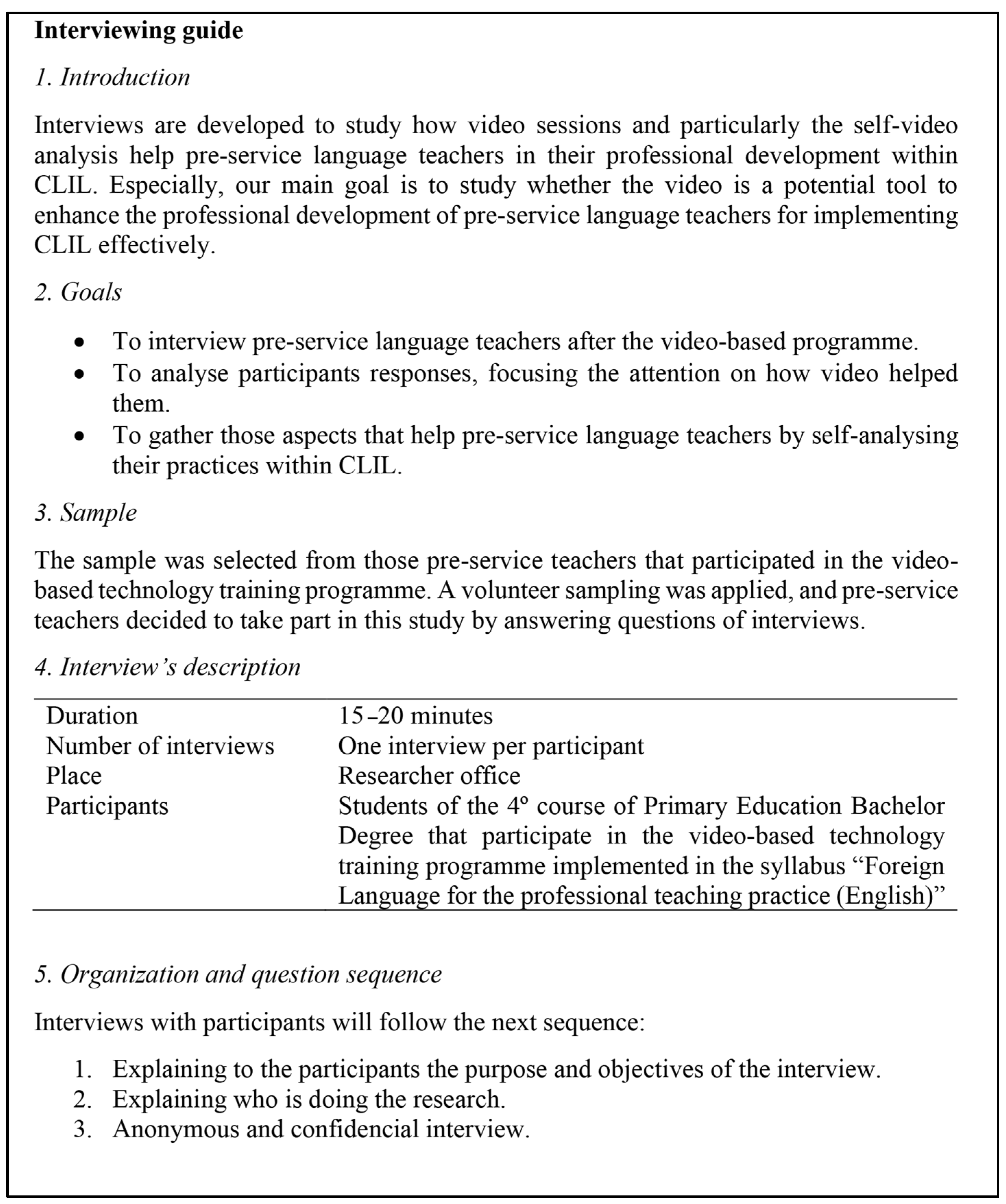

Appendix A. Interview Guide

Appendix B. Interview Final Questions

- How did you find VideoAnt as a tool to analyse your video?

- Did the analysis help you out? How?

- Do you think that video sessions helped in your teacher training in CLIL?

- Do you think watching yourself helps you in reflecting on your teaching practice? Why?

- Did video sessions help you understand the meaning of CLIL?

- Did video sessions influence the way you see your teaching practice in CLIL?

- How did video sessions help you in sharing teaching experiences with your partners?

- Do you believe video sessions help you share worries about CLIL with your partners?

- Did video sessions make you feel like part of a professional community?

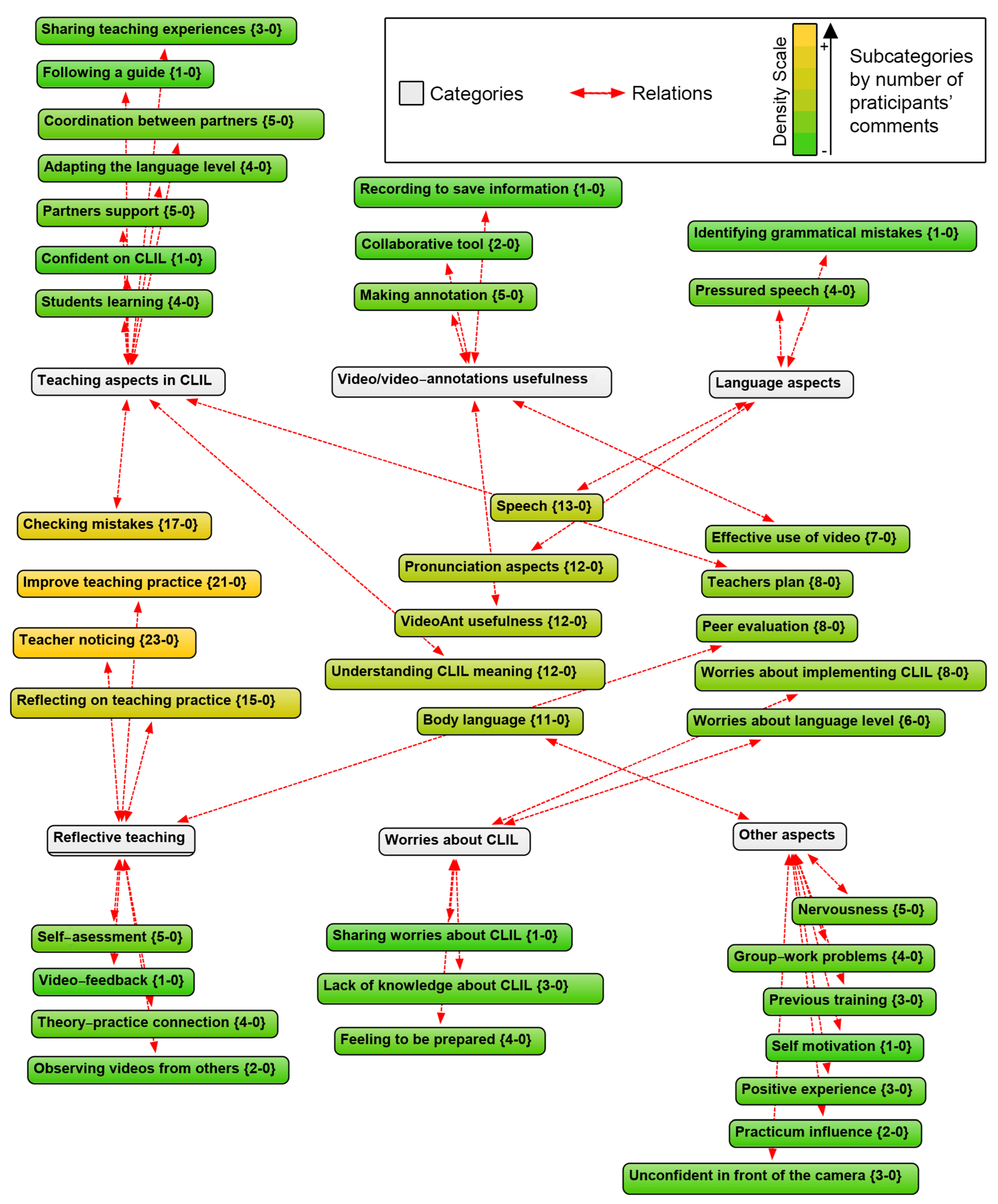

Appendix C. Results of Participants’ Responses: Categories and Subcategories

| 1 | VideoAnt is an online software for making annotations to an online video. Source: https://ant.umn.edu/ (accessed on 22 September 2023). |

References

- Arnáiz, Patricia. 2017. El inglés como lengua extranjera en España. ¿En qué convocatoria superaremos esta asignatura? In La Educación Bilingüe Desde una Visión Integrada e Integradora. Edited by María Isabel Amor, Rocío Serrano and Elisa Pérez. Madrid: Síntesis, pp. 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Azungah, Theophilus. 2018. Qualitative research: Deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qualitative Research Journal 18: 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, Elvira, and María Dolores Milla-Lara. 2018. CLIL methodology, materials and resources, and assessment in a monolingual context: An analysis of stakeholders’ perceptions in Andalusia. The Language Learning Journal 48: 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomberg, Geraldine, Miriam Gamoran Sherin, Alexander Renkl, Inga Glogger, and Tina Seidel. 2014. Understanding video as a tool for teacher education: Investigating instructional strategies to promote reflection. Instructional Science 42: 443–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borko, Hilda, Karen Koellner, Jennifer Jacobs, and Nanette Seago. 2011. Using video representations of teaching in practice-based professional development programs. ZDM Mathematics Education 43: 175–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calandra, Brendan, and Laurie Brantley-Dias. 2010. Using digital video editing to shape novice teachers: A generative process for nurturing professional growth. Educational Technology 50: 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarata, Laurent, and Corey Haley. 2018. Integrated content, language, and literacy instruction in a Canadian French immersion context: A professional development journey. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21: 332–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarata, Laurent, and T. J. Ó Ceallaigh. 2020. Teacher Development for Immersion and Content-Based Instruction. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Gaowei, and Carol K. K. Chan. 2022. Visualization-and analytics-supported video-based professional development for promoting mathematics classroom discourse. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 33: 100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. 2020. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Council of Europe Publishing. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/common-european-framework-of-reference-for-languages-learning-teaching/16809ea0d4 (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Coyle, Do. 2013. Listening to learners: An investigation into ‘successful learning’ across CLIL contexts. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 16: 244–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, Do, Phillip Hood, and David Marsh. 2010. Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Custodio Espinar, Magdalena, and José Manuel García Ramos. 2020. Are accredited teachers equally trained for CLIL? The CLIL teacher paradox. Porta Linguarum 33: 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- De Graaff, Rick, Gerrit Jan Koopman, Yulia Anikina, and Gerard Westhoff. 2007. An observation tool for effective L2 pedagogy in content and language integrated learning (CLIL). International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10: 603–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Martín, Cristina. 2020. Diseño y validación de un instrumento de observación para docentes en formación en AICLE. In Claves para la innovación pedagógica ante los nuevos retos: Respuestas en la vanguardia de la práctica educativa. Edited by Eloy López-Meneses, David Cobos-Sanchiz, Laura Molina-García and Alicia Jaén-Martínez y Antonio Hilario Martín-Padilla. Barcelona: Octaedro, pp. 1592–600. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Martín, Cristina, María-Elena Gómez-Parra, and Dara Tafazoli. 2022. Studying the professional identity of pre-service teachers of primary education in CLIL: Design and validation of a questionnaire. Aula Abierta 51: 329–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eröz-Tuğa, Betil. 2013. Reflective feedback sessions using video recordings. ELT Journal 67: 175–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, Cristina. 2013. Learning to become a CLIL teacher: Teaching, reflection and professional development. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 16: 334–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, Ilker, Sulaiman Abubakar Musa, and Rukayya Sunusi Alkassim. 2016. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics 5: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Peichang, and Angel M. Y. Lin. 2018. Becoming a “language-aware” content teacher: Content and language integrated learning (CLIL) teacher professional development as a collaborative, dynamic, and dialogic process. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education 6: 162–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüttner, Julia. 2019. Towards ‘professional vision’: Video as a resource in teacher learning. In The Routledge Handbook of English Language Teacher Education. Edited by Steve Walsh and Steve Mann. New York: Routledge, pp. 473–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hüttner, Julia, Christiane Dalton-Puffer, and Ute Smit. 2013. The power of beliefs: Lay theories and their influence on the implementation of CLIL programmes. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 16: 267–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Andalucía. 2016. Strategic Plan for the Development of Languages in Andalusia Horizon 2020. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/export/drupaljda/plan_estrategico.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Kim, Haemin, and Keith M. Graham. 2022. CLIL Teachers’ Needs and Professional Development: A Systematic Review. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning 15: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourieos, Stella. 2016. Video-mediated microteaching: A stimulus for reflection and teacher growth. Australian Journal of Teacher Education 41: 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasagabaster, David, and Yolanda Ruiz, eds. 2010. CLIL in Spain: Implementation, Results and Teacher Training. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, Yuen Yi. 2017. Development of the beliefs and language awareness of content subject teachers in CLIL: Does professional development help? International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22: 818–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Yuen Yi. 2020. Professional Development of CLIL Teachers. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, Francisco. 2010. CLIL in Andalusia. In CLIL in Spain: Implementation, Results and Teacher Training. Edited by David Lasagabaster and Yolanda Ruiz. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Steve, Andrew Davidson, Monika Davis, Jo Gakonga, Maricarmen Gamero, Tilly Harrison, Penny Mosavian, and Lynnette Richards. 2019. Video in language teacher education. ELT Research Papers 19: 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, Brian, and Nick Mitchell. 2014. The role of video in teacher professional development. Teacher Development: An International Journal of Teachers’ Professional Development 18: 403–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarranz, María. 2022. Aspectos clave de la profesionalización docente. Una revisión bibliográfica. Cuestiones Pedagógicas. Revista de Ciencias de la Educación 2: 129–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougald, Jermaine S. 2019. What is next for CLIL professional development? Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning 12: 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehisto, Peeter, David Marsh, and María Jesús Frigols. 2008. Uncovering CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning in Bilingual and Multilingual Education. Oxford: Macmillan Education. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, Sharan B., and Elizabeth J. Tisdell. 2015. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th ed. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, Tom. 2016. Being a language teacher in the content classroom: Teacher identity and content and language integrated learning (CLIL). In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Identity. Edited by Siân Preece. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 382–94. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Cañado, María Luisa. 2016. Are teachers ready for CLIL? Evidence from a European study. European Journal of Teacher Education 39: 202–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagasta, Pilar, and Begoña Pedrosa. 2018. Learning to teach through video playback: Student teachers confronting their own practice. Reflective Practice 20: 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, Rachel E., and Hope Kenarr Gerde. 2019. Personalized professional development. YC Young Children 74: 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yu-Chih. 2014. Microteaching writing on YouTube for pre-service teacher training: Lessons learned. CALICO Journal 31: 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydnor, Jackie. 2016. Using Video to Enhance Reflective Practice: Student Teachers’ Dialogic Examination of Their Own Teaching. The New Educator 12: 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafazoli, Dara. 2021. Language teachers’ professional development and new literacies: An integrative review. Aula Abierta 50: 603–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Steven J., Robert Bogdan, and Marjorie DeVault. 2015. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource, 4th ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Tripp, Tonya R., and Peter J. Rich. 2012. The influence of video analysis on the process of teacher change. Teaching and Teacher Education 28: 728–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villabona, Nerea, and Jasone Cenoz. 2021. The integration of content and language in CLIL: A challenge for content-driven and language-driven teachers. Language, Culture and Curriculum 35: 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phases | Session 1 | Session 2 | Session 3 | Session 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Brainstorming to come up with different ideas | Creating an activity to teach vocabulary | Introducing participants to using video annotation software and the observation guide | Planning a CLIL lesson of the designed IDUs |

| Phase 2 | Designing the title, objectives, and content of IDUs 1 | Presenting the activity to partners and recording themselves | Watching a real CLIL lesson on YouTube | Simulating a CLIL lesson and recording themselves |

| Phase 3 | Presenting the first draft and recording themselves with smartphones | Watching video recordings and filling out an observation template | Using the video annotation software and the observation guide in the analysis | Using the video annotation software and the observation guide for making the analysis |

| Phase 4 | Watching video recordings and discussing with partners | Providing a space for participants to discuss after filling out the template | Planning a CLIL lesson from the designed IDUs | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Díaz-Martín, C. Professional Development of Pre-Service Language Teachers in Content and Language Integrated Learning: A Training Programme Integrating Video Technology. Languages 2023, 8, 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040232

Díaz-Martín C. Professional Development of Pre-Service Language Teachers in Content and Language Integrated Learning: A Training Programme Integrating Video Technology. Languages. 2023; 8(4):232. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040232

Chicago/Turabian StyleDíaz-Martín, Cristina. 2023. "Professional Development of Pre-Service Language Teachers in Content and Language Integrated Learning: A Training Programme Integrating Video Technology" Languages 8, no. 4: 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040232

APA StyleDíaz-Martín, C. (2023). Professional Development of Pre-Service Language Teachers in Content and Language Integrated Learning: A Training Programme Integrating Video Technology. Languages, 8(4), 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040232