Abstract

This study relies on an interactional, conversational–analytic approach to elucidate what meanings Chilean Spanish speakers convey via creaky voice quality in informal conversations. Highly creaky utterances produced by 18 speakers were derived from a larger corpus of sociolinguistic interview speech from Santiago, Chile, and examined via an interactional approach that accounted for how creaky voice figured in the process of meaning-making and meaning negotiations throughout the conversation. Results indicate that approximately 40% of highly creaky utterances were used to organize the speaker’s discourse, signaling the end of turns, hedges or uncertainty, and a change in communicative purpose, while the majority of the highly creaky utterances were used to invoke alignment with the listener via ensuring that their messages or stances were understood and potentially endorsed. This study offers evidence from a non-English language for creaky voice as a tool for both discursive organization and interactional alignment.

1. Introduction

Cross-linguistically, non-modal phonation has been shown to have multiple meanings. Non-modal phonation may indicate phonological contrast in languages such as Hmong (Esposito and Khan 2012), Zapotec (Esposito 2003), and Gujarati (Esposito and Khan 2012). Creaky voice specifically has been shown to indicate phrase position as in English (Henton and Bladon 1988; Podesva 2013) and Finnish (Ogden 2001). Finally, and most importantly to the present paper, Podesva and Callier (2015) assert that non-modal phonation is a “rich phonetic resource through which speakers can display affect and take stances in interaction” (Podesva and Callier 2015, p. 173). They point to recent research in the fields of linguistic anthropology and sociolinguistics that exemplifies non-modal voice quality as a resource for the construction of social meaning (Podesva 2007; Sicoli 2010; Hildebrand-Edgar 2016).

The aim of this paper is to identify how speakers of Chilean Spanish use creaky voice to position themselves in interactions, with particular attention paid to the meaning being constructed in conversation. As Acton (2021) claims, “what speakers say and how they say it is not merely the product of exogenous forces but also depends on speakers’ beliefs about how listeners would evaluate a given variant—and, in turn, how useful the variant would be in helping them achieve their desired ends” (As Acton 2021, p. 2). This attention to the specific communicative goals of the speaker, as well as how their utterances would be perceived, is centrally located within the realm of third-wave sociolinguistics (Eckert 2012) as the speaker’s meaning as well as agency are foregrounded. This also aligns with Du Bois’ (2007, p. 171) definition of stance as a public action, not something you can perform individually or privately. Taking a stance entails, therefore, that speakers “simultaneously evaluate objects, position subjects (themselves and others), and align with other subjects, with respect to any salient dimensions of the sociocultural field” (Du Bois 2007, p. 163). As Podesva (2007, p. 498) indicates, situating phonetic forms in their discursive contexts and attempting to infer the social meaning of linguistic features is a new analytical tactic for determining the meaning of variation that my work aims to propel. It is also well aligned with conversation analysis, which identifies conversation as the most basic level of social organization that humans have (Sacks et al. 1978). In this view, the interlocutor is a necessary participant in the creation of meaning within the discourse, as is a thorough account of the broader sociocultural, political economic realities of the conversation (Sidnell 2013, p. 85).

In the remainder of this section, I first examine previous findings related to characteristics and uses of creaky voice in English and in other languages. I then review the literature related to my methodological approach.

1.1. Creaky Voice and Prosodic Phrasing, Cross-Linguistically

As Davidson (2021) describes, creaky phonation is not a monolithic phenomenon, and a variety of acoustic characteristics (such as low fundamental frequency, irregular spacing of glottal pulses in the spectrogram, and decreased amplitude in comparison with modal phonation) may signal what listeners perceive as creaky voice. Garellek and Keating (2011, p. 187) refer to this as the “plethora of physiological dimensions of voice quality variation”. In spite of this variation, one consistent finding related to the production of creak has to do with the aerodynamic requirements for speech production that also co-occur with higher prosodic domains. That is, several studies have found that creak is more likely to occur at the ends of utterances. For instance, Henton and Bladon (1988) examined United Kingdom English speech and found that the occurrence of creak was greater on the final syllable as compared to the other syllables in a sentence. In United States English, Redi and Shattuck-Hufnagel (2001) found a high rate of glottalization of words at the end of utterances and phrases, similar to the results of Slifka (2006). Podesva (2013) finds that of the six types of non-modal phonation analyzed in sociolinguistic interviews with English speakers, creaky phonation is more likely to occur in the intonation phrase-final position. Podesva (2013) relates this to declination, the gradual diminishing of fundamental frequency over the course of an utterance. Indeed, phrase endings have been shown to co-occur with the end of a breath, phonation-ending laryngeal gestures, and a drop in alveolar pressure, which presents a challenge for modal voicing (Redi and Shattuck-Hufnagel 2001; Slifka 2006; Wolk et al. 2012).

Creak has been shown to have similar functions in other languages. For instance, Ogden (2001) reported that in Finnish, a glottal stop was used as a turn-holding strategy (indicating that the speaker intended to repair or continue their discourse), while creaky syllables typically marked the end of a turn. Ogden (2001) demonstrated that creak co-occurred with other cues for turn transition such as intonation, tempo, and duration. Garellek and Keating (2015) and González et al. (2022) have provided evidence for creak in phrase-final position in Spanish, and Garellek (2014) also documented an utterance-initial glottalization effect in read Spanish akin to findings from English (Garellek 2014; Redi and Shattuck-Hufnagel 2001; Dilley et al. 1996).

1.2. Voice Quality and Its Uses beyond Prosodic Phrasing

Podesva and Callier (2015) delineated three ways that voice quality can serve as an index of identity. The first is as a signifier of belonging to a particular group or category such as gender, race, class, and linguistic identities. Podesva (2013) identified both gender- and ethnicity-based groupings of non-modal phonation in sociolinguistic interview speech among white and African American residents of Washington, D.C. Podesva and Callier (2015) also pointed to voice quality as a way for listeners to distinguish individual speakers. The third function of voice quality delineated by Podesva and Callier (2015) is that of stancetaking, particularly of affective or emotional stances (Du Bois 2007). While the authors cautioned against directly associating voice qualities with particular affective displays, they advocated for turning the analytical focus on voice quality to the various indexical possibilities for particular, situated productions of marked voice qualities (Podesva and Callier 2015, p. 183). For instance, Lee (2015) found that creaky voice was used in sociolinguistic interviews when a speaker temporarily suspended the ongoing discursive frame by inserting a sequence that was identified as belonging to a different frame, which she denoted parenthetical use. The parenthetical functions in Lee’s (2015) data included jokes, off-the-record comments, inner thoughts, and additional or preemptive provision of information. According to Lee (2015, p. 295), using creak allowed a speaker to both mark a proposition as parenthetical and also to create a parenthetical effect in order to perform some kind of stancetaking. Similarly, Torres et al. (2020) examined the production of creaky voice quality situated within patient/provider interactions. The authors found that English-speaking patients in medical interactions used both low pitch and creaky voice when narrating symptoms or describing pain and when requesting opiates. The authors centered the discussion of their findings on the national conversation about opioids in the United States, positing that using creaky voice when requesting opioids is a way to counter the stigmatization of their use.

1.3. Voice Quality Variation as Stancetaking in Non-English-Speaking Contexts

Podesva and Callier (2015) noted that little research has investigated the ways in which affective indexicalities of voice quality differ cross-culturally. They pointed to the work of Sicoli (2010) as an exception to the focus on English-speaking communities and as an illustration of other kinds of stances that can be constructed from voice material. Specifically, Sicoli (2010) examined the speech of Lachixío Zapotec speakers in various situations with different interlocutors to demonstrate that variations in voice quality copattern with audiences, pragmatic functions such as requesting, and voice registers. According to Sicoli’s analysis, falsetto phonation showed respect, breathy phonation indicated authority, creaky phonation sought commiseration, and whisper phonation marked urgency (Sicoli 2010, p. 545), revealing that voice qualities are enregistered through their co-occurrences with the participant roles taken up in speech situations. Similarly, Wilce (1997) examined patient and provider interactions in Bangladesh and showed that creaky voice frames pain in the patients’ talk. Wilce argued that creaky voice is an “icon” of weakness and low energy and also functions as a way to “underline and lend credibility to the speaker’s reference to her own pain” (Wilce 1997, p. 363).

The accounts above weave together the social context and linguistic functions of creak and other non-modal voice qualities. In the next subsections, I highlight the importance of conversational interaction for examining the interplay between creaky voice, a speaker’s communicative purpose and social context, and the role of the interlocutor.

1.4. Organizing Conversational Interaction

Earlier work in discourse and conversation analysis focused on the delineation of turns or determining which party talks at which time in a conversation (Sacks et al. 1978). As Clayman (2012) summarizes, turns are incrementally built out of a succession of turn-constructional units (TCUs), such as words, phrases, clauses, and sentences, and each TCU ends in a transition-relevant place (TRP) (Sacks et al. 1978) where an interlocutor may optionally retake the floor. More recent work has focused on deconstructing turns into higher-level discourse units. For instance, Selting (2000) argued that “big projects” such as storytelling create a single TCU that is organized internally into smaller units of other kinds. In the first study of its kind, rather than focusing on a particular or specialized speech genre such as a narrative or a joke, Biber et al. (2021) conducted a bottom-up analysis of a large English-speaking corpus that revealed that most conversational talk consists of sequences of coherent discourse units that have identifiable communicative purposes (p. 34). Biber et al. (2021) defined a communicative purpose as the more general communicative actions or tasks that interlocutors hope to achieve in conversation (Biber et al. 2021, p. 24). To make this claim, the authors first divided their conversational data consisting of informal face-to-face conversations between two or three people into discourse units (hereafter DUs). The authors operationalized the DUs as recognizably self-contained (their boundaries are noted by a shift in the conversation’s overarching communicative goal), coherent for their overarching communicative goal (that is, interlocutors have a particular goal in the conversation, such as complaining about annoying co-workers or making plans for buying holiday gifts), and at least five utterances (or 100 words) (Biber et al. 2021, p. 23).

From these DUs, the authors then developed a taxonomy of nine communicative purposes: situation-dependent commentary (when speakers comment on things that are present or occurring in their shared situational context); joking around (conversation intended to be humorous); engaging in conflict (including disagreement of any type); figuring things out (discussion aimed at exploring or considering options or plans); sharing feelings and evaluations (including feelings, evaluations, opinions, and beliefs, including the airing of grievances); giving advice and instructions (offering directions, advice, or suggestions to another speaker); describing or explaining the past (including narrative stories about true events from the past or references to people or events from the past); describing or explaining the future (including descriptions or speculations about future events and intentions); and describing or explaining (time neutral) (consisting of description or information about facts, information, people, or events in which time is either irrelevant or unspecified). Each DU could have up to three primary and secondary purposes, and the authors determined that two broad categories of sharing feelings and evaluations and of conveying information accounted for over 80% of the general communicative purposes. This approach is similar in some ways to Goffman’s (1974) notion of frame, which delineates how an individual categorizes or makes sense of their social interactions. However, in my view, Biber et al. (2021) offer a more clearly defined, empirically verified approach for determining the communicative purposes of discourse units within informal conversation. These categorizations are exhaustive, accounting for each of the components of the discourse, and the authors demonstrate that nearly all discourse is organized at a more micro level (albeit within a particular linguistic and social context, the English-speaking United Kingdom). The present paper demonstrates how creaky voice can be used to signal a change in communicative purpose types in Chilean Spanish conversational data.

1.5. The Relevance of the Interlocutor’s Response and Alignment

In addition to the organization of discourse into units, another key tenet of conversation analysis is the importance of the interlocutor to the construction of meaning (Schegloff et al. 1996, p. 40; Duranti 1986). Uniting the concepts of discourse organization and interlocutor response, Stivers (2008) posits that the TRP is the appropriate place for an interlocutor to respond to a speaker’s stance (though nodding and providing other short feedback such as “mhm” and “yeah” mid-turn is a way for the interlocutor to recognize that the speaker’s turn is still ongoing), suggesting that the “preferred response to a storytelling is the provision of a stance toward the telling that mirrors the stance that the teller conveys having […] whether that is as funny, sad, fabulous, or strange” (Stivers 2008, p. 33). Stivers (2008) calls this alignment, or supporting the ongoing talk of the speaker, in contrast with affiliation, denoting that a hearer displays support of and endorses the teller’s conveyed stance. Clayman and Raymond (2021) use alignment in a different sense. Instead of an appropriate response to an ongoing storytelling turn, Clayman and Raymond posit that what they term alignment may initialize a conversation, in that it may invoke “a state of alignment without asserting it as such, which prompts validating responses without making them obligatory” (Clayman and Raymond 2021, p. 294). In their analysis of the you know particle in English, they term this usage an alignment token (Clayman and Raymond 2021), an element that invokes a convergent orientation between recipient and speaker. As Clayman and Raymond (2021, p. 293) argue, this alignment token may be intersubjective (that the listener correctly grasps the speaker’s meaning), affiliative (that the recipient supports the action or stance being taken), or both.

Clayman and Raymond’s work illuminates the potential for conversation analysis to move the field of interactional sociolinguistics forward and highlights the importance of acknowledging that the sociolinguistic interview is essentially a conversation, bound by norms and rules, and subject to the disfluencies and speech production difficulties that arise in everyday conversation.1 For instance, as Clayman and Raymond (2021) describe, the you know particle can be used by speakers to ensure that in spite of their hesitation, disfluency, or self-repair, the recipient will still be able to grasp their meaning. You know may also be used when the speaker recognizes that what they are saying is not exactly what they mean to say, but they want to ensure that the recipients understand their meaning. Clayman and Raymond (2021, p. 300) define these as sub-optimal formulations, in that they “[fall] short of the speaker’s expressive aims, or [that they are] potentially problematic for recipients to grasp as intended, or both of these in combination. In these cases, understanding on the recipient’s part is important to continue the forward conversational movement.

Additionally, you know is often recruited for actions that aim to elicit or garner some sort of response, whether acceptance or rejection, such as assessment, recruitment actions and accounts, and misdeeds (Clayman and Raymond 2021, p. 303). For instance, assessments and other evaluative comments, especially those that are “relatively ‘extreme,’ negatively valenced, or have a critical edge, are recurrently accompanied by alignment tokens” (p. 303). You know may also be used when the speakers are engaged in or reporting misdeeds or acts that may be regarded as mischievous or in breach of societal norms. In these cases, you know “invokes support for the questionable action and often elicits confirmation” (p. 305).

I use the data presented below to argue that creaky voice in Chilean Spanish primarily serves as a tool to “invoke a convergent orientation between speaker and listener” (cf. Clayman and Raymond 2021, p. 294) via an interactional approach. Like the particle you know in Clayman and Raymond’s (2021) analysis, the domain of creak is basically unrestricted. That is, because it consists of a laryngeal configuration that can be deployed by all human language users, creak could appear anywhere, on any syllable. Therefore, when creak appears in certain places, we may assume that it serves a particular purpose. In the data below, I examine the purposes of creak in these Chilean Spanish sociolinguistic interviews. I show that creak has two primary functions: to organize discourse and to invoke alignment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Initial Coding

The data for this analysis derive from a larger corpus of sociolinguistic interviews with Chilean Spanish speakers about a variety of topics, such as how they had celebrated Chilean Independence Day, how they met their partners/spouses, and whether they had had strict upbringings. The speakers resided in two relatively homogeneous neighborhoods of Santiago, belonged to three age groups (18–25, 26–41, 42+),2 and comprised all six of the Chile-specific socioeconomic groups defined by Sadowsky (2021).3 In Bolyanatz (2023), I describe how I followed Podesva (2013) in selecting two topics of conversation that had been spoken on at length by nearly all 41 speakers: talk about relationships and talk about the local community. I hypothesized that both of these topics would be “non-neutral” (cf. Yuasa 2010) or be more likely to elicit increased emotional or affective stancetaking. For instance, the talk about the local community was of particular interest to residents of these two neighborhoods, both of which are characterized as socioeconomic extremes and perceived to be facing recent increases in crime.

Following the delineation of topics, I then coded utterances. In the transcriptions below, each line is a separate utterance organized by pauses at the beginning and end (Du Bois et al. 1993; Chafe 1993). Subsequently, I coded the first approximately 100 syllable nuclei within each topic for a total of 9030 coded syllables. Each syllable was coded for several features including position within the utterance and six types of voice quality (modal, breathy, creaky, whisper, harsh, and falsetto following Podesva (2013)). I used auditory–visual methods (Dallaston and Docherty 2020) to code for creaky voice. The auditory parameters included perception of rough or gravel-like quality, and the visual parameters included increased irregularity of pulses in the waveforms and/or widely spaced vertical striations in the spectrograms. Using binary coding (creaky vs. not creaky) accounts for the variation in types of creaky voice established cross-linguistically (Garellek and Keating 2011; Keating et al. 2015; Davidson 2021), but that are of less importance for the present project focused on the meaning of creak. The examples below show a few key elements of the coding.

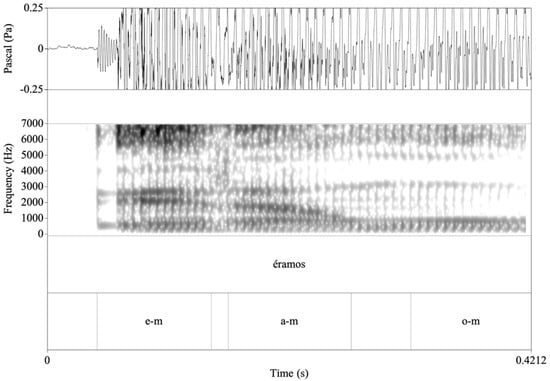

First, Crowhurst (2018) showed that Mexican Spanish listeners were sensitive to creak as a cue to utterance-finality when a syllable was at least 30% creaky. Therefore, syllables in the present study had to be at least 30% creaky (though often were >50% creaky) to be binary coded as creaky (though, of course, Chilean Spanish listeners may respond differently to creak than Mexican Spanish listeners, a topic I return to in the Discussion section). This restriction meant that some tokens, such as the utterance-initial /e/ in Figure 1, were excluded.

Figure 1.

Waveform, spectrogram, and textgrid noting orthographic transcription and syllable-level coding (vowel identity and voice quality identity noted; “m” = “modal”). Speaker lp.m.3.05.

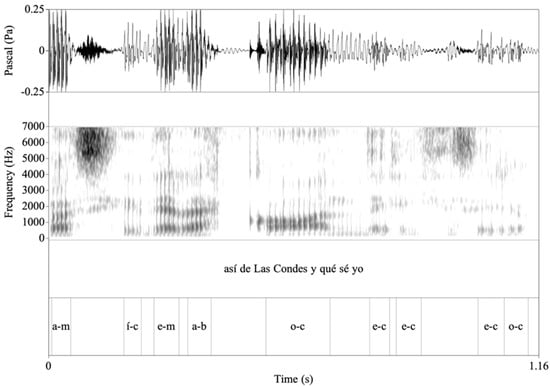

This utterance-initial vowel was produced with a small amount of glottalization but did not reach the 30% threshold to be coded as creaky. For this reason, this vowel was coded as modally voiced. In contrast, sometimes creak was readily apparent over the length of multiple syllables. For instance, in Figure 2, the speaker began creaking on the stressed/o/vowel of the word “Condes” (Las Condes is a wealthy neighborhood in Santiago), and creak was present on the remaining syllables in the utterance.

Figure 2.

Waveform, spectrogram, and textgrid noting orthographic transcription and syllable-level coding (vowel phoneme and voice quality identity noted; m = “modal”; c = “creaky”, b = “breathy”). Speaker lp.m.1.05.

2.2. Defining the Highly Creaky Utterances and Turns

From the larger dataset described above, I examined the 442 tokens of creaky voice that were not in utterance-initial or utterance-final position and selected utterances that had at least three creaky tokens within. Upon review of the data, I noted that nearly all the utterances within one speaker’s turns (v.m.3.01) were highly creaky. This speaker was the oldest in the sample (75 years of age at the time of data collection), and his voice was also accompanied by “roughness” or an overall gravelly quality of voice (Hollien 1987). These are likely correlates of chronological age that make it difficult to separate creak used for discursive purposes from creak as a function of aging vocal folds. This speaker’s highly creaky tokens were therefore excluded, leaving eighteen speakers’ highly creaky tokens for further analysis (age range 21–58). Similar to the methods of Podesva (2013) and Lee (2015), these strict criteria yielded ninety-two “highly creaky” utterances for analysis produced by eighteen speakers. The highly creaky utterances were produced by residents of both field sites and by both men and women.

Once I had identified the highly creaky utterances (henceforth HCUs), I turned to delineating the boundaries (beginning and end) of each of the turns that contained the HCUs. The onset of a highly creaky turn (HCT) was often the speaker’s response to a question I had posed or a topic change of the speaker’s own volition that began the DU. Two speakers produced two HCTs within the dataset while the other speakers produced one each, generating 20 HCTs for analysis. Each highly creaky turn had at least one HCU per turn, and one speaker had up to eleven HCUs within (mean = 3.98 HCUs per HCT). The turns were then categorized into discourse units following those established by Biber et al. (2021). The end of the turn coincided with syntactic, prosodic, and pragmatic completeness that indicated a transition-relevant place (Levinson and Torreira 2015).

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, I provide an overview of how creak is used within these data. I then examine each of the subtypes of the functions of creak using excerpts from the data and show several examples of how different functions may be used in tandem within single HCTs.

All 20 HCTs shared the same communicative purposes: all were primarily or secondarily focused on describing or explaining the past, describing or explaining time-neutral information, and sharing feelings and evaluations. If the primary focus was describing or explaining, the secondary focus of nearly all of them was sharing feelings and evaluations (in close alignment with the findings of Biber et al. (2021)). As described above, I posit that creak is used in two primary ways in these data: to organize discourse and to serve as tokens for alignment. In (1), I provide a brief explanation of each function.

- 1.

- Functions of creak present in the data

- a.

- Creak used to organize discourse (39%)

- i.

- At the end of turns, signaling a turn-yielding function (9/96 of the HCUs, 9%; 9/20 of the turns ended with several highly creaky syllables; 45% of the turns)4

- ii.

- To signal a pivot between discourse units (DUs) (7/96 uses of HCUs; 7%)

- iii.

- To signal a hedge or uncertainty or a site for self-repair (10/96 uses of HCUs; 10%)

- iv.

- To indicate a parenthetical (or outside the discourse unit) joke, off-the-record comment, inner thought, and additional or preemptive provision of information (cf. Lee 2015) (11/96 HCUs; 11%)

- b.

- Creak used to signal stance (61%)

- i.

- Understanding: situations in which understanding may be relevant or at risk (30/96 HCUs; 31%)

- ii.

- Affiliation: the recipient supports the action or stance being taken (28/96 HCUs; 29%)

3.1. Creak Used to Organize Discourse

Excerpts 1 through 7 detail the discourse-organizing functions of creak in these data. First, HCUs appeared at the end of HCTs, signaling a turn-yielding function. Of the 20 HCTs, HCUs ended 9 of them (45%). An example is included in Excerpt 1 below. In each of the excerpts, underlining indicates creaky voice, and arrows indicate HCUs. Breathy voice is indicated via italics, whisper voice via strikethrough, and falsetto voice in bold, and all non-creaky, non-modal phonation is described textually. In this excerpt, Marta was telling me about her relationship with her boyfriend and his son and noted that her boyfriend had just moved into her family home.

- (1)

- Marta describing a conversation between her and her boyfriend, who recently moved in with her; discourse unit: describe/explain the past (primary); sharing feelings and evaluations (secondary).

| 1 2 | Yo le pregunté el otro día po le dije <quote-past self> Oye, ¿qué tú hai echado de menos a tus papás? </quote> // <softer> // | |

| 3 4 5 | <quote> No, </quote> <lengthening> me dijo pero se le pusieron sus ojos llenos de <emphasis> lágrimas </emphasis, falsetto> y a mí me dio pena y lo abracé po // | |

| 6 7 | → | Lo abracé y me dijo <breathy>: <quote> Sí, sí igual los extraño pero me siento bien aquí contigo </quote> me dijo que él <lengthening/> // |

| 8 9 10 | → | Que él es hombre <emphasis; falsetto> me dijo <quote> Yo soy hombre <breathy>, a mí no me va a costar tanto como te hubiera costado a ti po </quote> me di |

| 1 2 | I asked him the other day po5 I said <quote-past self> <softer> Hey, have you been missing your parents? </quote> </softer> // | |

| 3 4 5 | <quote> No <lengthening> </quote> he told me but his eyes filled up with <emphasis> tears </emphasis; falsetto> and I felt sad for him and I hugged him po. | |

| 6 7 | I hugged him and he said to me <quote> yes, yes I do miss them but I feel good here with you </quote> he said that he <lengthening> | |

| 8 9 10 | He’s a <emphasis> man </emphasis, falsetto> he told me <quote> I’m a man, it’s not going to be as hard for me as it would have been for you po </quote> he told me. |

Utterance 4 (Lines 7–8) is one of only four HCUs in the dataset that comprise two sets of three-syllable stretches of creak in the same utterance. I focus on the final syllables of the utterance here. Of the last five syllables of the utterance (Line 8, starting with “ti po”), four are creaky. While the very final syllable in the utterance, and indeed the turn overall, is whispery (which is found in several turns throughout the dataset), I posit that these several syllables of creak in the turn-final position indicate that the turn is ending. These creaky syllables also co-occurred with syntactic completeness (Levinson and Torreira 2015) and pitch and intensity lowering.

Creak on utterance-final, turn-medial syllables is also prevalent. For instance, in this same turn, two of the three turn-medial utterances ended with one or two creaky syllables. A similar phenomenon is represented in Excerpt 2. In this excerpt, I had just asked the speaker (Carmen) if she was the ”regalona”, Chilean slang for the favorite, or the apple of the parent’s eye.

- (2)

- Carmen describing her relationships with her siblings; DU: sharing feelings and evaluations (primary); describing/explaining the past (secondary).

| 1 2 | sí <lengthening/> no <rising intonation> no la regalona <emphasis> tampoco <emphasis/> no no <silencio/> | |

| 3 | y con mi hermano ahí no más | |

| 4 | → | no me llevo bien con él <silence/> |

| 5 | con mi hermana– // | |

| 6 | → | <emphasis> más <emphasis/> todavía con mi hermana // |

| 7 8 | porque resulta que mi hermana eh <lengthening/> la casa donde vivo es donde vivo es de mi <emphasis> mamá <emphasis> // | |

| 9 | que <breathy> en paz descanse <breathy> / | |

| 10 | ella <emphasis> falleció <emphasis/> | |

| 11 | → | y resulta que <lengthening/> |

| 12 | → | la casa estaba en nombre de ella <breathy> /// |

| 13 | y qué es lo que pasa que ahora es mi <rising intonation > hermana la que <rising intonation; lengthening/> | |

| 14 | busca problemas por la ca | |

| 15 | → | que a ella le pertenece la <emphasis> casa <emphasis/> <lengthening/> |

| 16 | → | que ella <lengthening/> |

| 17 | → | que aquí ella «Oh» me sacaba varias veces en cara la casa / |

| 18 19 | [en]tonces le le digo yo que eso no es <emphasis> justo <emphasis; rising intonation> porque ahora le pertenece a los <emphasis> tres </emphasis> po / | |

| 20 | antes no porque antes existía había una ley que era pa las puras <lengthening> | |

| 21 | las que eran <emphasis> solteras <emphasis/> / | |

| 22 23 | → | pero ahora <emphasis> no <emphasis/> porque ahora ya está todo <emphasis> cambiado <emphasis/> ahora ya /// |

| 1 2 | Yes <lengthening/> no <rising intonation> no, not the <emphasis> regalona <emphasis> no no | |

| 3 | Me and my brother more or less | |

| 4 | I don’t get along with him | |

| 5 | with my sister-- | |

| 6 | even more with my sister | |

| 7 8 | because it turns out that my sister eh <lengthening> the house that I live in belongs to my <emphasis> mom <emphasis> | |

| 9 | may she rest in peace | |

| 10 | she passed away | |

| 11 | and it turns out | |

| 12 | the house was in her name | |

| 13 | and what happens is that now it’s my sister who is <rising intonation; lengthening/> | |

| 14 | looking for trouble over the house | |

| 15 | that it belongs to her | |

| 16 | that she | |

| 17 | that here she <quote> Ohh <quote> she’s thrown the house in my face several times | |

| 18 19 | so I’ve told her that that’s not fair because now it belongs to the <emphasis> three <emphasis> of us po | |

| 20 | before no because before there was a law that it was for only | |

| 21 | women who were <emphasis> single <emphasis/> / | |

| 22 | but not anymore because now all that is changed now |

Of the 23 syllables in the turn-final utterance, 14 of them are creaky. Additionally, of the 19 utterances within this turn, 11 are creaky on the final syllable. Perhaps, like Ogden (2001) describes for Finnish, short creak (creak on only one syllable) in utterance-final position in the middle of a larger project is a turn-holding strategy, while speakers may signal turn-ending with longer stretches of creak. It is also possible that this is simply the natural result of declination as air runs out toward the end of the utterance, as described by Podesva (2013).

The second use of creak to organize a turn is found at the adjunct of two discourse units that comprise differing communicative purposes. Seven of the 92 HCUs had this purpose. For instance, Excerpt 3 reveals how the communicative purpose of the speaker shifts within a single utterance. In this excerpt, after the speaker explains how she became involved with a neighborhood NGO, she shifts her communicative goal to reflect on the importance of the NGO’s presence in the community and to offer her own perception of the community center.

- (3)

- Mercedes describing the local community; DU: describing/explaining (time neutral) (primary); sharing feelings and evaluations (secondary)

| 1 | Porque muchas familias // | |

| 2 | Sobre todo en comunas <breathy voice> así // | |

| 3 | Existe mucho lo que <lengthening/> // | |

| 4 | Violencia intrafamiliar // | |

| 5 | Mucho mucho demasiado // | |

| 6 | Eh mucha drogadicción // | |

| 7 | Mucho alcohol // | |

| 8 | → | Entonces la iniciativa de La Colorada a mí me parece // |

| 9 | → | Pero <emphasis> excelente <breathy voice/> <emphasis/> <lengthening/> // |

| 1 | Because many families | |

| 2 | Especially in communities like this one | |

| 3 | There exists a lot of | |

| 4 | intrafamilial violence | |

| 5 | A lot a lot too much | |

| 6 | Eh a lot of drug addiction | |

| 7 | A lot of alcohol | |

| 8 | So the initiative of La Colorada to me seems | |

| 9 | Just excellent |

In Line 8, the speaker shifts from a time-neutral description of the community to an utterance that introduces the affective judgment in Line 9. In Line 8, the discourse marker “entonces” begins to mark the shift in communicative purpose, which is then doubly indicated by creaky voice later in the phrase. Additionally, the setup of the affective judgment is seen not only in the phrase “me parece” (it seems to me) but also in the grammatically optional unit of “a mí” (to me), essentially creating a phrase that doubly indicates that the speaker is about to offer her positive personal perception, set up in contrast to the negative portrayal of the community in the previous lines.

The third use of discourse-organizing creak indicates hedging or other uncertainty or signals self-repair. This use can be seen in Excerpts 4 and 5. For instance, Excerpt 4 below by Mauricio reengages a topic that we had been previously discussing (the socioeconomic differences present in my fieldwork neighborhoods) though I had just asked him an unrelated question: whether he had traveled outside of Chile.

- (4)

- Mauricio describing travel experiences; DU: describe/explain (time neutral) (primary); sharing feelings and evaluations (secondary).

| 1 | Eh, no | |

| 2 | No he salido de | |

| 3 | Tengo <lengthening> amigos sí que han salido mucho | |

| 4 | O sea | |

| 5 | Acá igual | |

| 6 7 | → | Por ejemplo como te digo así de Las <emphasis> Condes <emphasis/> y qué sé yo |

| 8 | Eh | |

| 9 | Sí me ha llamado harto la atención // | |

| 10 | Eso ha sido como una <lengthening> // | |

| 11 | Como diferencia // | |

| 12 | → | Así como bastante // |

| 13 | De estatus socioeconómico <rising intonation> // | |

| 14 | Y solamente me he dedicado a explorar acá lo que es Chile no más // | |

| 1 | Uh, no | |

| 2 | I haven’t left Chile | |

| 3 | I do have friends that have traveled a lot | |

| 4 | That is | |

| 5 | here the same | |

| 6 7 | For example like I was saying like from Las Condes and what do I know | |

| 8 | Uh | |

| 9 | That has really stood out to me | |

| 10 | That’s been a | |

| 11 | like a difference | |

| 12 | just like pretty… | |

| 13 | about socioeconomic status | |

| 14 | And I’ve dedicated myself to exploring here just within Chile |

In Line 12, Mauricio is using creak to hedge or signal his uncertainty about how to formulate the remainder of this sentence most appropriately. In Chile, socioeconomic status is highly salient, but like in the United States, explicit talk about class can be taboo, and so the appropriate formulation eludes him in this line.

Another reformulation is seen in Excerpt 5 by Gustavo. I had just asked him which of his siblings he got along with best or with whom he was closest. In Line 3, Gustavo offers more detail about how he is closest to his brother, who lives in the south of Chile, whom he had identified in Line 2. He describes how he is like that brother in that they share many things, including a commitment to and affinity for something that he begins to identify at the end of Line 4. He cuts himself off, and in HCU Line 5, identifies that this thing they share is social action. Using creaky voice, Gustavo creates a repair from the previous line that he had cut off.

- (5)

- Gustavo describing his relationships with his siblings; DU: sharing feelings and evaluations (primary); describe/explain the past (secondary).

| 1 | Em | |

| 2 | El que vive en el sur | |

| 3 4 | Que yo comparto con él <emphasis> muchas <emphasis/> cosas como que a los dos nos gusta mucho la- | |

| 5 | → | La acción social se podría decir // |

| 6 | Él también vivió en una población | |

| 7 | Y, y | |

| 8 | Y él estuvo trabajando en el Techo para Chile mucho tiempo | |

| 9 | Después trabajó en <emphasis> Chiloé <emphasis> en el Techo pa Chile <breathy> | |

| 10 | Y, hace poquito se salió po // | |

| 11 12 13 | → | Entonces como que los dos tenemos muchos temas en común siempre que nos juntamos como que salvamos el <emphasis> mundo <emphasis> por así decirle y creamos <emphasis> proyectos <emphasis> igual // |

| 14 | Nunca hacemos <breathy> nada pero igual nos quedamos ahí <breathy/laughter> // | |

| 15 | En la conversa // | |

| 1 | Um | |

| 2 | The one that lives in the south | |

| 3–4 | I share a lot of things with him like both of us really like the | |

| 5 | Social action you could say | |

| 6 | He also lived in a low-income community | |

| 7 | and, and | |

| 8 | and he worked for Techo para Chile for a long time | |

| 9 | After that he worked in Chiloé for the Techo para Chile | |

| 10 | And, a little bit ago he got out po | |

| 11 12 13 | So the two of us have a lot in common every time we get together it’s like we save the world for lack of a better way to say it and we come up with projects too | |

| 14 | We never do anything but it just stays there | |

| 15 | In our conversation |

Finally, the fourth category of creak used as a discourse organizer is similar to Lee’s (2015) parenthetical grouping, shown in Excerpts 6 and 7. In this category, creaky voice is used to indicate off-the-record comments, jokes, and additional or preemptive provision of information. For instance, in Excerpt 6, Claudio is responding to my question about whether he gets along with his siblings and goes on to say much more about their present versus past relationship.

- (6)

- Claudio responding to my question about whether he gets along with his siblings; DU: describe/explain (time neutral); share feelings and opinions (secondary).

| 1 | ¿con los, mis hermanos <rising intonation>? / | |

| 2 | Eh sí / | |

| 3 | Sí con mis hermanos / | |

| 4 | aparte que estamos todos <breathy voice> / | |

| 5 | <emphasis> desparramados <emphasis> <breathy voice> / | |

| 6 | tratamos de / | |

| 7 | estar lo <lengthening/> / | |

| 8 | lo <emphasis> máximo unidos </emphasis> / | |

| 9 | → | no es como <emphasis> antes <emphasis> de / |

| 10 | → | pucha a ver cómo le puedo explicar / |

| 1 | With the, my siblings? | |

| 2 | Eh yes | |

| 3 | Yes with my siblings | |

| 4 | Aside from the fact that we’re all | |

| 5 | scattered around | |

| 6 | We try to | |

| 7 | be the | |

| 8 | most connected | |

| 9 | it’s not like before that | |

| 10 | Jeez, let’s see, how can I explain it to you |

In Line 10, Claudio verbally expresses his uncertainty, stepping out of the frame of his response to my question about his siblings to make an off-the-record comment. He is frustrated at his inability to express himself exactly how he wants to (indicated by his creaky production of the gentle expletive “pucha”), which he then follows with the phrase “a ver cómo le puedo explicar” (how can I explain this to you).

Additional or preemptive information was also included in Excerpt 7. I had just asked the speaker how she had met her boyfriend, and this HCT begins with her response.

- (7)

- Carolina explaining how she met her boyfriend; DU: describe/explain the past (primary); sharing feelings and evaluations (secondary).

| 1 | Eh <lengthening> mi pololo <rising intonation/> | |

| 2 3 | → | En el colegio en mi primer colegio <falsetto> yo estuve en <emphasis> dos <emphasis> colegios // |

| 4 | Y <lengthening> lo conocí | |

| 5 | → | Cuando tenía <emphasis> doce <emphasis> a |

| 6 | Pololeamos <falsetto> | |

| 7 | Típico pololeo de cabros chicos | |

| 8 | De la <emphasis> mano <emphasis> no sé qué | |

| 9 | Y terminamos porque su papá es | |

| 10 | → | |

| 11 | Pasaron <emphasis> doce años <emphasis> <falsetto> | |

| 12 | Que no nos vimos más yo no supe de él | |

| 13 | Ni Facebook ni nada <rising intonation> | |

| 14 | Volvió <emphasis> este año <emphasis> <falsetto voice> | |

| 15 | El vivió doce años en Armenia <rising intonation> | |

| 16 | Y <lengthening> se vino <rising intonation> | |

| 17 | Se le acabó la visa creo <falsetto> | |

| 18 | Y y no po me agregó <falsetto> | |

| 19 | A Facebook <rising intonation> | |

| 20 | Lo invité a un matrimonio y quedamos | |

| 21 | Enamorados | |

| 22 | Otra vez | |

| 23 | → | Y <lengthening> ahora estamos pololean |

| E: | Wuau, ¡es como una película! | |

| 1 | Uh my boyfriend | |

| 2–3 | In high school in my first high school I was in two high schools | |

| 4 | And I met him | |

| 5 | When I was twelve years old | |

| 6 | We went out | |

| 7 | A typical relationship between young kids | |

| 8 | Holding hands and what have you | |

| 9 | And we broke up because his dad is | |

| 10 | His dad is a diplomat so they travel a lot | |

| 11 | Twelve years went by | |

| 12 | In which we didn’t see each other at all and I didn’t hear anything from him | |

| 13 | Not even Facebook or anything | |

| 14 | He came back this year | |

| 15 | He’d spent twelve years in Armenia | |

| 16 | And he came back | |

| 17 | His visa expired I think | |

| 18 | And and no po he added me | |

| 19 | on Facebook | |

| 20 | I invited him to a wedding and we fell | |

| 21 | in love | |

| 22 | again | |

| 23 | and now we’re back together | |

| E | Wow, it’s like a movie! |

In Utterance 2 (Lines 3 and 4), we see the first of two parenthetical additions of information. The speaker has begun the narrative of how she met her boyfriend but then deviates almost immediately to offer additional information regarding her primary school experience, specifically that she had been in one school but then changed to another (resulting in two different schools, as she mentions). I had asked her earlier what school she had gone to, and she had named one; here, she offers additional background information that is not immediately relevant to the current narrative. Another line of additional or background information is offered in Line 10 to explain why they had broken up: because her boyfriend’s father was a diplomat, they had to leave Chile for his next posting. This line serves to indicate that had her boyfriend not been required to leave; they would likely have stayed together. The creak in Line 23, the final utterance of the turn, serves to indicate that the turn has come to an end, creating a transition-relevant place (like those shown in Excerpts 1 and 2). I responded appropriately by remarking that it was like a movie, and she replied that yes, many people tell her that their story is like a movie or fairytale.

The final example of parenthetical usage of creaky voice in this dataset is that of humor or jokes. In Excerpt 5 seen above, Gustavo describes how close he is with his brother due to their shared commitment to social action. In Lines 11–13, he says:

“Entonces como que los dos tenemos muchos temas en común siempre que nos juntamos como que salvamos el <emphasis> mundo <emphasis> por así decirle y creamos <emphasis> proyectos <emphasis> igual //”

The use of creaky voice here follows a usage of irony in a hyperbolic sense (i.e., “salvamos el mundo” we save the world), and the creaky “creamos proyectos igual” (we come up with plans, too) conjures up a vision of the two brothers, affiliated in relationship and worldview, chatting and coming up with great plans. In the retelling, Gustavo downplays this project creation in a teasing fashion. This line also serves as the setup for the humorous, self-deprecating joke in Lines 14–15, in which he says “Nunca hacemos nada pero igual nos quedamos ahí” meaning but we never actually carry out those plans).

3.2. Creak Used to Invoke Alignment

I now turn to the use of creaky voice to invoke a convergent orientation between speaker and listener. Excerpts 8 through 10 reveal that creak is used to invoke alignment in two ways: to ensure understanding and to recruit affiliation on the part of the listener. Excerpt 8 exemplifies both types. Constanza lives with her parents, her sister, and her sister’s two children and essentially acts as a co-parent to them. I asked specifically about whether she was close with her sister. In Excerpt 8, we first see creaky voice used to ensure understanding and later in the turn to seek affiliation.

- (8)

- Constanza describing her relationship with her sister; DU: sharing feelings and evaluations (primary); describe/explain (time neutral) (secondary).

| 1 | A mi <emphasis> hermana <breathy voice> <emphasis/> <silencio> // | |

| 2 | Sí <lengthening/> // | |

| 3 | No tengo problemas con ella // | |

| 4 | De hecho, hay veces que parecemos <emphasis> matrimonio <breathy voice> </emphasis>// | |

| 5 | ||

| 6 | Sí, es muy divertido cuando nos em ponemos a conversar <rising intonation> // | |

| 7 | → | Y le digo las <breathy, emphasis> cosas </emphasis> // |

| 8 | → | y a veces le echo // |

| 9 10 11 | → | le digo un par de <emphasis> garabatos <emphasis/> y ella me los <emphasis> devuelve <emphasis> y nos ponemos a <emphasis> pelear <emphasis>, el <emphasis> manotazo <emphasis>, pare- <breathy voice> // |

| 12 | En serio que parecemos un matrimonio a veces // | |

| 13 | Es muy divertido // | |

| 1 | With my sister | |

| 2 | Yes | |

| 3 | I don’t have a problem with her | |

| 4 | In fact, there are some times that we act like a married couple | |

| 5 | It’s true | |

| 6 | Yes, it’s really fun when we um start to chat | |

| 7 | And I tell her things | |

| 8 | Sometimes I toss | |

| 9–11 | I throw out a couple of curse words, she throws them right back at me, and we start to fight, smack each other, we seem- | |

| 12 | Seriously we seem like a married couple sometimes | |

| 13 | It’s really fun |

In Line 4, the speaker makes an unexpected claim (that of sisters acting as a married couple). Though it is not recorded here, based on the response in Line 5 (“It’s true!”), I must have responded in a nonverbal way that indicated disbelief or doubt, which could have included raised eyebrows or other markers of incredulity. Highly creaky Lines 7–9 are aimed at ensuring comprehension on my part via additional detail and support for her claim. As Clayman and Raymond (2021) indicate, this type of alignment token is present in utterances that are potentially problematic for recipients to grasp as intended (p. 300). Conversely, the affiliation use of creak is seen specifically in highly creaky Line 9. This utterance includes mention of several socially deviant behaviors, including cursing at one another and slapping each other. As Clayman and Raymond (2021) indicate, throughout this reporting of misdeeds, when the listener’s affiliation may be seen as at risk, creaky voice as an alignment token “invokes support for the questionable action and often elicits confirmation” (p. 305). Interestingly, the slapping retell is overlaid not by creaky voice but by breathy voice. Perhaps, as other scholars have shown, non-modal voice quality may serve complementary purposes across the discourse (Podesva 2007, p. 487).

Other affiliation-seeking tokens are present throughout the dataset, such as above in Mauricio’s Excerpt 4. In Line 3, Mauricio responded to my question about whether he had traveled outside the country by saying no, but that several of his friends had. He then uses two separate utterances, “O sea” (I mean) and “Acá igual” (here the same), to appropriately formulate his next statement, which begins with two separate discourse markers: “por ejemplo” (for example) and “como te digo” (like I was saying) before the highly creaky portion of the utterance: “así de Las <emphasis> Condes <emphasis/> y qué sé yo” (like from Las Condes and what do I know). By using creaky voice in this utterance, Mauricio is not simply reporting where his friends are from but positioning Las Condes and its inhabitants as separate from himself, geographically but also socially, and inviting me to align with him in endorsement of this positioning. Las Condes, in this utterance, is emblematic of the moneyed social classes in Santiago (also comprising neighborhoods such as Vitacura, Lo Barnechea, and La Dehesa; (Rodríguez Vignoli 2007)). These neighborhoods are on the periphery of the city, difficult to access without a personal vehicle, and many of their residents are aligned with the political right (AS Chile 2020). Mauricio seeks my affiliation, my convergent orientation toward these neighborhoods, and perhaps negative valence or critical edge toward some of these characteristics of their inhabitants (Clayman and Raymond 2021, p. 303) in contrast with his own identity. I posit that creaky voice enables him to invoke this affiliation without explicitly stating it.

In the final two excerpts presented here, speakers Gonzalo and Mercedes use creak both to organize their discourse and to invoke alignment. Gonzalo uses creaky voice in Excerpt 9 to ensure understanding and to recruit affiliation for behavior that might be seen as controversial. At the beginning of the turn, I asked Gonzalo whether his parents are stricter with him than his younger female siblings and asked him about a specific example between Lines 8 and 9 or to expand upon his parents’ hopes for him.

- (9)

- Gonzalo responding to my question about whether his parents are stricter with him than with his younger (female) siblings; DU: sharing feelings and evaluations (primary); describing/explaining the past (secondary).

| E: | Y por ser el mayor, ¿tus papás son más estrictos contigo? <¿Más exigentes?> | |

| 1 | <Sí.> | |

| 2 | O sea <lengthening> sí | |

| 3 | No sé si ahora tanto porque las otras ya son mayores de edad, pero | |

| 4 | Antes, sí po a mí me llegaba el reto y después a la otra… | |

| 5 | Más o menos no más po ya porque me habían retado a mí | |

| 6 | Pero, sí aparte que soy el único hombre po entonces | |

| 7 | Yo creo que me ponen más… | |

| 8 | Más responsabilidades | |

| E: | ¿Y qué quieren para ti? ¿Quieren que tú seas ingeniero y esa cuestión? ¿O qué es lo que quieren para ti? | |

| 9 | ||

| 10 | Una de las carreras principales po <breathy> | |

| E: | ¿Y cuáles son esas? | |

| 11 | → | No sé como arquitectura, ingeniería comercial |

| 12 | Y yo como que no sabía mucho, no estaba ni ahí | |

| 13 | Pero tenía que estudiar porque no me iban a dejar no estudiar | |

| 14 15 | → | Dije, <quote> me convencí, ya ingeniería comercial po, si, debe ser lo mío po, si no sé qué hacer <quote> |

| 16 | Y chao, me terminé, metiéndome a la- | |

| 17 | A la U ahí | |

| 18 19 | → | Y como era una escuela de negocios igual, no sé po era entretenido, de repente, pero después ya empecé a chatear y los ramos y los ramos y los ramos y no <lengthening> |

| 20 | → | Ya no podía más |

| 21 | Por eso me, al final | |

| 22 | → | Por eso tomé la decisión de irme <lengthening> a Madrid |

| 23 | → | Pa cambiar un poco el aire |

| 24 | → | Pa seguir avanzando // |

| E | So because you’re the oldest, do you think your parents are stricter with you? More demanding? | |

| 1 | Yes | |

| 2 | I mean yes | |

| 3 | I don’t know about now so much because the girls are over 18 but | |

| 4 | before, yes po they always punished me and then to them | |

| 5 | They only got punished a little because they’d already punished me | |

| 6 | But yeah apart from that I’m the only boy so | |

| 7 | I think they put more | |

| 8 | more responsibilities [on me] | |

| E | And what do they want for you? Do they want you to be an engineer and all that? Or what do they want for you? | |

| 9 | I mean, when I was younger they always pressured me to study | |

| 10 | one of the primary careers po | |

| E | And which are those? | |

| 11 | I don’t know like architecture, commercial engineering | |

| 12 | And since I didn’t know that much, I didn’t really care | |

| 13 | But I had to study because they weren’t going to let me not study | |

| 14 15 | I said, I’m convinced, ok, commercial engineering, that must be my thing, I don’t know what else to do | |

| 16 | And bye, I eventually enrolled in the | |

| 17 | in the university there | |

| 18 19 | and since it was really a business school, I dunno, it was fun, sometimes, but after that I started to get fed up and the classes and the classes and the classes and I couldn’t | |

| 20 | I couldn’t do it anymore | |

| 21 | So then I, finally | |

| 22 | So then I made the decision to go to Madrid po | |

| 23 | For a change of scenery | |

| 24 | To keep moving forward |

In highly creaky Line 11, Gonzalo responds to my naïve question about what the primary degrees of study are in Chile. This line serves as a clarification or additional information but has the primary goal of enabling me to understand this relevant background information, leading to its categorization as an understanding-type alignment token. Its importance becomes even more apparent throughout the turn because, in Line 14, the speaker reports his own thought process that resulted in him undertaking the study of commercial engineering. This highly creaky utterance is also seeking understanding as to why he would embark on the study of a degree that he later realized he did not like. Lines 18, 19, and 20 are seeking affiliation, invoking the recipient’s support for an ostensibly “controversial” action or stance (Clayman and Raymond 2021, p. 303) of failing college courses. In Line 19, the speaker also repeats the same phrase (“los ramos” the courses) three times to indicate that the courses became overwhelming and contributed to his burnout. Repetition has been shown to be a formal expression of a speaker’s evaluative stance, emphasizing the speaker’s take on the relative importance of some narrative units (Labov and Waletsky 1967, p. 39). Line 20 is an explicit expression of the speaker’s affective stance toward his career choice, which he had been building up to in the previous lines. Similarly, Lines 22–24 comprise the resolution of the speaker’s narrative as he describes the choice he made to enroll in a university in Madrid. Overall, the creak in these lines enables the speaker to cast himself in a favorable light as he describes and emphasizes the strange and unusual character of his situation (Labov and Waletsky 1967, p. 34).

Finally, several different functions of creak as well as a critical examination of my role as the interlocutor, are present in Excerpt 10. In Line 5, as Mercedes is retelling the story of how her husband abandoned her, she jokingly downplays being left with only CLP 2000 (approximately USD 4) in her pocket by saying that it was all right because her mother treated her to lunch. She uses this joke to downplay the gravity of what had happened to her and ends this utterance with several creaky syllables. I hypothesize that the creaky voice here was not necessarily used to indicate a transition-relevant place nor simply as a joke-telling parenthetical use. Rather, I posit that the creaky syllables and downplaying jokes allow the speaker, who is momentarily portraying herself in an unfavorable light, both to acknowledge the delicateness of the situation and to try to remedy it (Haakana 2001, p. 213). The speaker may have been looking for some sort of indicator (a smile, a laugh, etc.) that her joke had been understood and that the remedy had served its purpose. However, I was expecting a continuation of the story rather than a humorous utterance and was not prepared to respond appropriately. While I do not have video evidence of this misstep, given her discourse marker in Line 7 and the hedge at the beginning of Line 8, I believe that this was a missed opportunity to respond and empathize in an appropriate way with the affiliation-seeking of the creaky, downplaying joke.

- (10)

- Mercedes explaining the ending of her relationship with her children’s father; DU: describing/explaining the past (primary); sharing feelings and evaluations (secondary).

| 1 | Eh <silencio/> // | |

| 2 | Se las <breathy, emphasis> llevó <breathy voice> </emphasis> // | |

| 3 | Él-- // | |

| 4 | → | Yo me quedé con dos mil pesos en el <emphasis> bolsillo <breathy, emphasis/>// |

| 5 6 | → | Pero mi mamá me invitaba a <emphasis> almorzar </emphasis> así que no era como <silencio/> // |

| 7 | Bueno // | |

| 8 | Eh yo dije <quote> bueno ni importa <breathy> // | |

| 9 | Cuando regrese con las niñas <breathy; rising intonation> // | |

| 10 | Eh me va a dar para tener yo <silencio/> <quote/> // | |

| 11 | → | No fue así // |

| 12 | Llegó con las niñas // | |

| 13 | → | Manejando curado y todo // |

| 14 | → | Y me dijo <quote> yo de aquí en adelante no te doy // |

| 15 | <emphasis> un pe | |

| 16 | Arréglatela como <emphasis> puedas <breathy voice><emphasis/> // | |

| 17 | Me demandas // | |

| 18 | Y ahí cuando– // | |

| 19 | Salga el // | |

| 20 | → | Eh <lengthening> lo que yo te tengo que dar para las niñas <falsetto voice/> // |

| 21 | → | Ahí conversamos <quote/> // |

| 1 | Uh | |

| 2 | He left with them | |

| 3 | He | |

| 4 | I was left with two thousand pesos in my pocket | |

| 5 | But my mom invited me to lunch so it wasn’t like | |

| 6 | Well | |

| 7 | Uh I said well it doesn’t matter | |

| 8 | When he gets back with the girls | |

| 9 | He’ll give me something so that I have… | |

| 10 | That didn’t happen | |

| 11 | He arrived with the girls | |

| 12 | driving drunk and everything | |

| 13 | and he said to me from now on I’m not giving you | |

| 14 | one peso | |

| 15 | Figure it out as you’re able | |

| 16 | Sue me | |

| 17 | And then when | |

| 18 | It arrives | |

| 19 | Uh, what I have to give you for the girls | |

| 20 | Then we’ll talk |

This excerpt also boasts several instances of creak used to organize discourse as well as additional alignment tokens. First, in Line 4, in addition to communicating information, the creaky voice enables the speaker to not only assert that what her ex-husband did was deplorable but also invites me to agree or align with this perspective. Other indicators of this alignment seeking are present throughout the turn. For instance, Lines 8–10 are reported speech from her own past self, optimistically expecting that upon her husband’s return, he will see the error of his ways. Line 11 is a creaky discourse-organizing marker, shifting the communicative purpose from optimistic expectation to reporting information from the past. It also has a dramatic effect of indicating an action contrary to the speaker’s (and therefore also the hearer’s) expectations.

Similarly, highly creaky Line 13 is also seeking affiliation. Mercedes reports that her husband was driving drunk with her daughters in the car. In this reporting of behavior in breach of societal norms, the creaky voice invokes support for her position as critical of her husband, who has carried out this questionable and dangerous action (cf. Clayman and Raymond 2021, p. 303). This enables the speaker to position herself as reasonable and empathetic in comparison to her husband, who was unnecessarily cruel and careless. His reported cruelty is again confirmed in Line 14, in which he says he will not give her a single peso more. The reported speech of her husband (Lines 14–21) contributes to this distancing and negative portrayal, enabling the speaker to adopt a different voice from her own (cf. Stivers 2008, p. 39).

Line 20 is a highly creaky discourse organizer, enabling the speaker to repair the thought she started in Line 18. Perhaps she could not recall the exact wording of her husband’s quote. However, it is more likely that she was not quoting verbatim but rather expressing his general sentiment to achieve a rough approximation of his positioning (cf. Clayman and Raymond 2021, p. 300). Lines 18 and 19 are both syntactically incomplete, and the speaker starts Line 20 with a filled pause “eh”, signaling that she was still searching for the most appropriate way to express the term or idea she was looking for (something like the court-ordered child support amount). Line 21 rounds out the turn, creating a transition-relevant place via creaky voice, syntactic completeness, and the end of the reported speech.

Via the analysis presented here, I have identified two major functions of creak in these Chilean Spanish data: creak is used to organize discourse and to invoke alignment. I have shown that highly creaky utterances are used to organize discourse in four ways: at the end of larger utterances to signal a turn-yielding function; to indicate a pivot between discourse units (DUs) or communicative purposes; to signal a hedge or uncertainty or a site for self-repair; and to indicate a parenthetical (outside the discourse unit) joke, off-the-record comment, or additional or preemptive provision of information. These discourse-organizational uses account for approximately 40% of the highly creaky utterances in the dataset. The first finding aligns with previous work in English (Henton and Bladon 1988; Podesva 2013; Lee 2015) and Spanish (Garellek and Keating 2015; González et al. 2022) that shows that creak coincides with higher-order prosodic final positions. It also suggests that in Chilean Spanish, creaky voice may signal a turn-yielding function as in Finnish (Ogden 2001). Previous studies have identified that prosody plays a role in turn-yielding in addition to lexico-syntactic and pragmatic cues. For instance, Bögels and Torreira (2015) tested Dutch listeners’ responses to the questions “Are you a student?” and “Are you a student at Radboud University?” to see whether they attended to lexico-syntactic cues or these plus prosodic cues to indicate turn-finality. The authors found that increases in both pitch and duration significantly contributed to quicker and more accurate turn-prediction. However, these scholars did not examine voice quality in their analyses. In a corpus-based examination of American English, Argentine Spanish, and Slovak, Heldner et al. (2019) found that the presence of creak is more likely in a turn-final, transition-relevant place (i.e., a transition where the next speaker starts talking following a short silence) than in turn-holding or backchannel positions. These findings point to the possibility of a more robust relationship between creaky voice and turn-finality than previously considered, and the results of the present study offer preliminary evidence for creaky voice as a turn-yielding cue. However, this brief review of previous studies draws attention to a body of work that has aimed to empirically define turn-ending. In contrast, the present study has taken a broader view of a turn as a recognizably complete utterance within a given context (Hoey and Kendrick 2017). To address this limitation, it would be helpful to examine the prosodic correlates of turn-finality more closely, such as voice quality, duration, and f0, and operationalize the lexico-syntactic features of turn-finality. Moreover, these judgments of turn-finality have not accounted for how Chilean Spanish listeners themselves interpret turn-ending and whether they attend to creak in making these judgments. Further perceptual support for this claim connecting highly creaky utterances with turn-finality is required.

Regarding the second organizational function, to my knowledge, this is the first study that has associated creak with discursive or communicative purpose-based shifting. As I have shown here, participants described events and people in the past and present and shared their feelings and opinions throughout the conversations, using creak to indicate a shift in communicative purpose. While this use is categorized as a discourse organizational tool, creak’s co-occurrence with changes in communicative purpose also exhibits a stancetaking function: it is up to participants to decide who and what they will talk about and how they will express their personal stances and evaluations toward these chosen topics of conversation. Speakers are, therefore, agents in determining not only what they say but how they say it. This finding aligns with previous work (Grieser 2019; Kiesling 2009) that has shown how speakers incorporate multiple linguistic tools to style different parts of themselves in their quest to make social meaning, and with recommendations to focus on the contribution of the listener to the meaning-making process (Soukup 2018).

Creaky voice used to indicate hedging, uncertainty, or sites for self-repair were also found in Lee’s (2015) English-speaking data, as were examples of parenthetical or preemptive provision of information. This may indicate a cross-linguistic tendency that should be verified further using data from other languages. Creak used in tandem with hedging or uncertainty may also be indicative of a type of embodied cognition (Lakoff and Johnson 1999; Fauconnier and Turner 2002; Gibbs 2003) which connects the thought process and bodily experience. That is, speakers physically represent their current inability to complete their thought via a bodily expression of creak, which studies have shown to be accompanied by lower pitch and intensity (Shayan et al. 2011; Lefkowitz and Sicoli 2007), perhaps indicative of communication directed internally toward the self rather than outwardly toward the listener.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, I have shown how speakers of Chilean Spanish use creaky voice to organize their discourse and to position themselves in interaction with an unfamiliar interlocutor. Creak is primarily used in these data as an alignment token that invokes the listener’s understanding or affiliation. Understanding may be at risk due to the speaker’s formulation of their thoughts (often accompanied by false starts or hesitations) or the listener’s non-local positioning (as an L2 speaker of Chilean Spanish and not a member of the local community). Affiliation may be at risk due to the speaker’s retelling of socially risky behavior or stance or because of their positioning regarding other actions or others’ perspectives. Similarities between the results of this study and Clayman and Raymond’s (2021) analysis of the particle you know confirm that it is not creaky voice per se that can act as an alignment token but rather that the co-occurrence of creaky voice with lexical, syntactic, and prosodic features within a particular setting and with a particular sociocultural backdrop can invoke a convergent orientation between speaker and listener.

This analysis is one of the first of its kind within Chilean Spanish sociolinguistics. It has allowed for an examination of communication that eschews macrosocial demographic groupings typical of the first wave of sociolinguistics and centers stance as a resource for individual action (Jaffe 2009, p. 20). This focus on speakers’ agency, affiliation, and their broader discursive purposes may inform other examinations of voice quality as an interactional resource, particularly given its focus on a non-English language.

Additional research in this area, including analyses of speakers’ perception of the meanings of creaky voice, could contribute to determining whether this may be an indexical change in progress (Hall-Lew et al. 2021a), but as it stands, this study has shown that creaky voice can help construct meaning in situated interactions, serving as a resource for taking stances and making social moves (Hall-Lew et al. 2021b, p. 1).

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Ben and Rue Pine travel award on behalf of the UCLA Department of Spanish and Portuguese.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of UCLA (approval code 15-001231, 20 August 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to IRB restrictions.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to my participants for sharing their time and personal stories with me. Many thanks also to Lex Owen for comments on earlier versions of this chapter, to Whitney Chappell and Sonia Barnes for their careful, insightful feedback, and to two anonymous reviewers for comments that substantively improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | I align with Briggs (1986), Speer (2002), and Van den Berg et al. (2003), who advocate for treating the sociolinguistic interview as a conversation. Briggs (1986) specifically recommends critical analysis of the interview to examine points at which the interviewer and interviewee have misunderstood each other, as well as exploring the “communicative roots” of the interview to examine its norms with attention paid to the speaker’s milieu as well as the discursive meaning being made. |

| 2 | The age classifications are based on the year of birth related to the Pinochet dictatorship, aligning with Delforge’s (2009) approach to relying on important historical and sociopolitical events to delineate age groups. The youngest speakers were at least 18 and were born post-dictatorship (so were 25 or younger at the time of data collection), 26–41-year-olds were born during the dictatorship, and 42+ were born prior to the 1973 coup. |

| 3 | The EMIS system created by Sadowsky (2021) determines socioeconomic stratification based on the level of education and the occupation of the individual (or, in the case of younger speakers in the present study, the individual’s parents). These groups are Chile-specific and, according to Sadowsky (2021), are approximately comparable in English to extreme upper (A), upper (B), upper middle (Ca), lower middle (Cb), lower (D), and extreme lower (E). |

| 4 | There were a total of 92 unique highly creaky utterances, but four of them had two groupings of three or more highly creaky syllables: one at the end of the utterance (co-occurring with the end of the turn) and an additional group of three or more highly creaky syllables not in utterance-final position. I only counted an utterance twice if it showed these specific characteristics, making the denominator for all proportions 96. |

| 5 | “Po” is a Chilean Spanish discourse marker deriving from the standard Spanish adverb “pues”. It is used frequently in informal Chilean Spanish, often to underscore a point, signifying something like ‘certainly’ (Makihara 2005). Pragmatic cross-dialectal work has indicated that pues as a discourse marker is not grammatically essential, but leaving it out can affect the force of the utterance and/or the discourse cohesion (Fuentes-Rodríguez et al. 2016). These authors also indicate that po(h) used in Chilean Spanish may have multiple functions, including intensification and closing, suggesting that its meanings may differ based on utterance position and pragmatic value. For this reason, I have chosen not to gloss discursive po in the transcriptions above. |

References

- Acton, Eric K. 2021. Pragmatics and the Third Wave: The Social Meaning of Definites. In Social Meaning and Linguistic Variation: Theorizing the Third Wave. Edited by Lauren Hall-Lew, Emma Moore and Robert Podesva. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 105–26. Available online: https://www.emich.edu/english/documents/faculty/pragmatics_and_the_third_wave.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- AS Chile. 2020. Resultados Plebiscito Nacional 2020: Mapa por comunas de Santiago de Chile. Diario AS, October 26. sect. Actualidad. Available online: https://chile.as.com/chile/2020/10/26/actualidad/1603716098_944619.html (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Biber, Douglas, Jesse Egbert, Daniel Keller, and Stacey Wizner. 2021. Towards a Taxonomy of Conversational Discourse Types: An Empirical Corpus-Based Analysis. Journal of Pragmatics 171: 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyanatz, Mariška. 2023. Non-modal voice quality in Chilean Spanish. Spanish in Context, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Bögels, Sara, and Francisco Torreira. 2015. Listeners Use Intonational Phrase Boundaries to Project Turn Ends in Spoken Interaction. Journal of Phonetics 52: 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, Charles L. 1986. Learning How to Ask: A Sociolinguistic Appraisal of the Role of the Interview in Social Science Research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chafe, Wallace. 1993. Prosodic and Functional Units of Language. In Talking Data: Transcription and Coding in Discourse Research. Edited by Jane Edwards and Martin Lampert. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Clayman, Steven E. 2012. Turn-Constructional Units and the Transition-Relevance Place. In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Edited by Jack Sidnell and Tanya Stivers. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 150–66. [Google Scholar]

- Clayman, Steven E., and Chase Wesley Raymond. 2021. ‘You Know’ as Invoking Alignment: A Generic Resource for Emerging Problems of Understanding and Affiliation. Journal of Pragmatics 182: 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowhurst, Megan J. 2018. The Influence of Varying Vowel Phonation and Duration on Rhythmic Grouping Biases among Spanish and English Speakers. Journal of Phonetics 66: 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallaston, Katherine, and Gerard Docherty. 2020. The Quantitative Prevalence of Creaky Voice (Vocal Fry) in Varieties of English: A Systematic Review of the Literature. PLoS ONE 15: e0229960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, Lisa. 2021. The Versatility of Creaky Phonation: Segmental, Prosodic, and Sociolinguistic Uses in the World’s Languages. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews Cognitive Science Cognitive Science 12: e1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delforge, Ann Marie. 2009. The Rise and Fall of Unstressed Vowel Reduction in the Spanish of Cusco, Peru: A Sociophonetic Study. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Davis, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dilley, Laura, Stefanie Shattuck-Hufnagel, and Mari Ostendorf. 1996. Glottalization of Word-Initial Vowels as a Function of Prosodic Structure. Journal of Phonetics 24: 423–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, John. 2007. The Stance Triangle. In Stancetaking in Discourse: Subjectivity, Evaluation, Interaction. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 139–82. Available online: http://dubois.faculty.linguistics.ucsb.edu/DuBois_2007_Stance_Triangle_M.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Du Bois, John, Stephan Schuetze-Coburn, Susanna Cumming, and Danae Paolillo. 1993. Outline of Discourse Transcription. In Talking Data: Transcription and Coding in Discourse Research. Edited by Jane Edwards and Martin Lampert. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Duranti, Alessandro. 1986. The Audience as Co-Author: An Introduction. Text 6: 239–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2012. Three Waves of Variation Study: The Emergence of Meaning in the Study of Sociolinguistic Variation. Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, Christina. 2003. Santa Ana Del Valle Zapotec Phonation. Master’s thesis, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]