Developing L2 Intercultural Competence in an Online Context through Didactic Audiovisual Translation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- Attitudes refer to holding an open outlook towards other cultures, respecting and valuing them, being intrinsically motivated to learn, and avoiding an ethnocentric assumption of one’s own culture (Gopal 2011).

- Knowledge and comprehension pertain to acquiring in-depth understanding of the target language (including verbal and nonverbal cues) and developing cultural self-awareness, for instance, how one’s own culture influences one’s identity, behaviours, values and way of thinking (Gopal 2011).

- Skills relate to experimenting with meaning, being critical of one’s communication with others for meta-cognitive knowledge, having communication skills, and self-reflection regarding noticing, coding and interpreting (Gopal 2011).

3. Materials and Methods

Culture is an important factor affecting happiness. International surveys of subjective well-being (SWB) show consistent mean level differences across nations. For example, in a survey carried out last year 65% of Danes were very satisfied with their lives, while only 5% of the Portuguese said they were very satisfied. In the several surveys before that, the proportion of Danes who were very satisfied with life was also around 12 times that of the Portuguese.

Culture of individualism prevails in Western countries in Europe and America. People emphasise individual freedom, individual achievement, and the pursuit of individual positive feelings. Thus, the relationships between SWB and individual effort and achievement are more direct, possibly making happiness levels higher.

In the collectivist culture zones including Japan, Korea, and China, people put relatively more emphasis on human relationships, including families, colleagues and neighbours. Happiness feelings are affected relatively more by the evaluation of others. The relationships between SWB and individual effort and achievement are not clear. This may make their happiness levels lower than in the individualist countries.

Health and Tradition

Dairy products like milk, yogurt, cheese, and cottage cheese, are good sources of calcium, which helps maintain bone density and reduces the risk of fractures. Adults up to the age of 50 need 1000 milligrams (mg) of calcium per day. Women older than 50 and men older than 70 need 1200 mg. Milk is also fortified with vitamin D, which bones need to maintain bone mass.

British people are cheese lovers and they have traditional delicious cheeses such as: Cheshire, Red Leicester, Double Gloucester and Cheddar.

Cheshire Cheese is a traditional cheese which is one of the oldest made in England with an open, crumbly and silky-smooth texture. Red Leicester…

“I think maybe Dan has something to add” means…

Taking a break

Dealing with names

Making sure everyone has a chance to speak

Talking about documents

Checking what someone means

Checking who said something […]

Read the following sayings and quotes about dating and find an equivalent in Spanish for at least two of them (you don’t need to translate them word by word, just look for a phrase that could mean the same):

Example: Real magic in relationships means an absence of judgement from others. La verdadera magia de una relación reside en la ausencia de juicios externos.

Virginia was asked to talk about women and fiction…

4. Sample Description

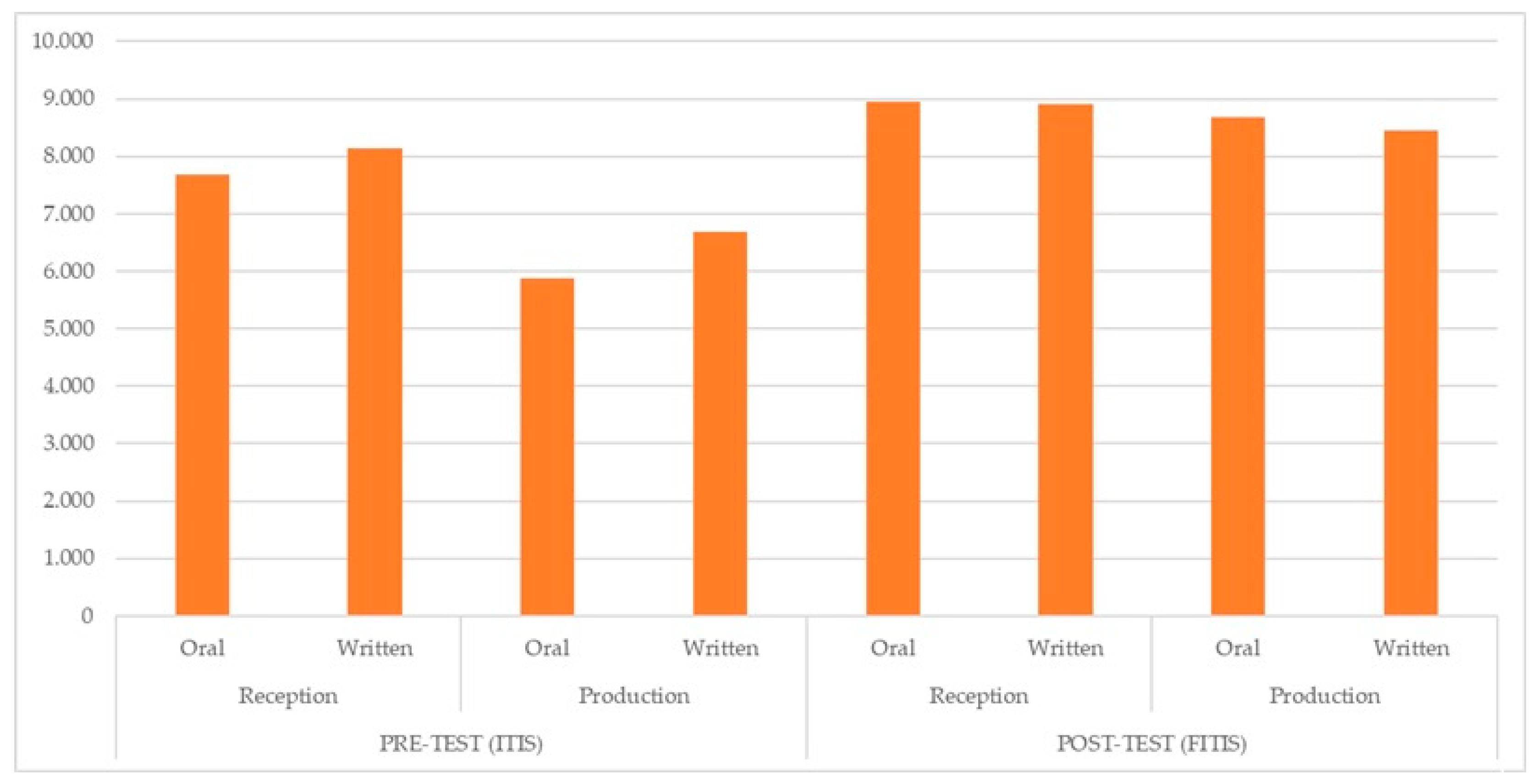

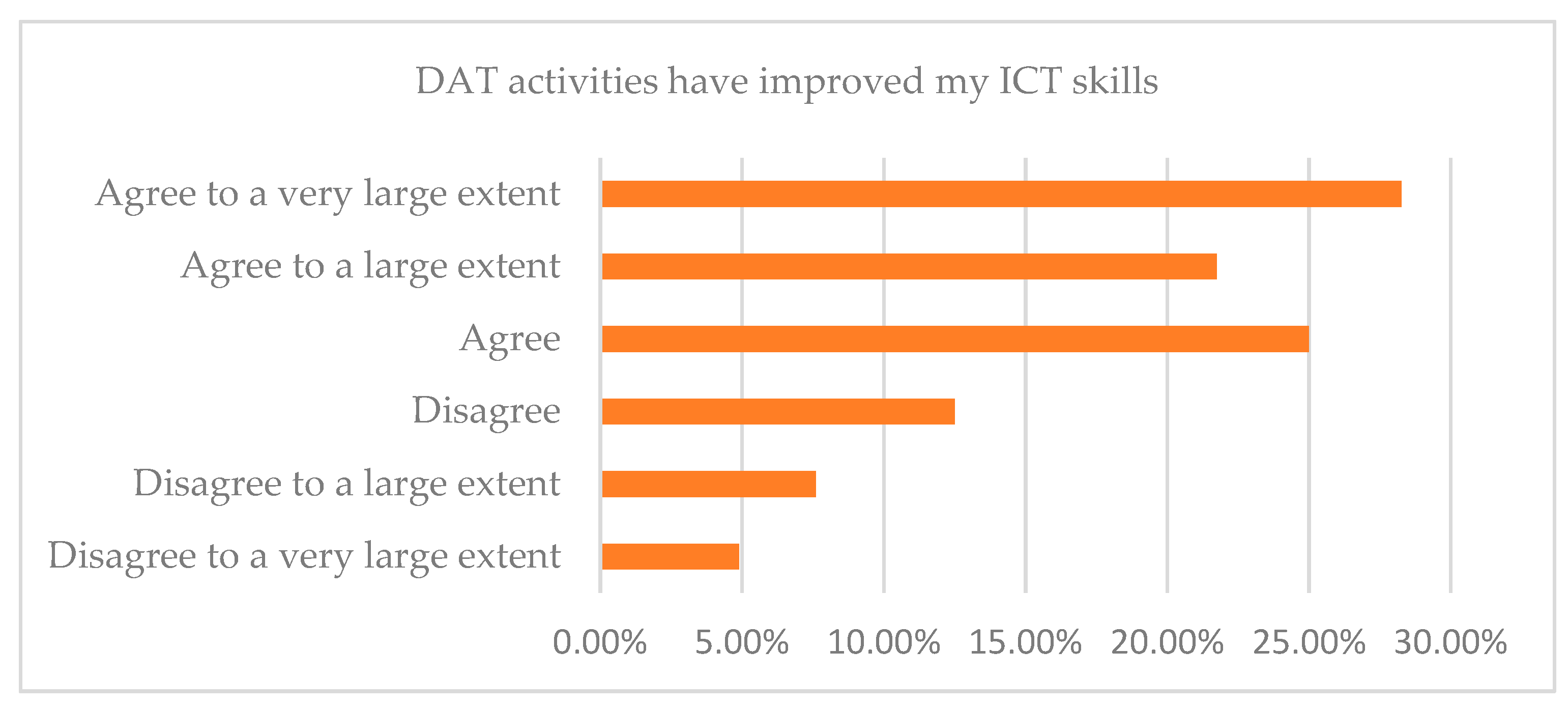

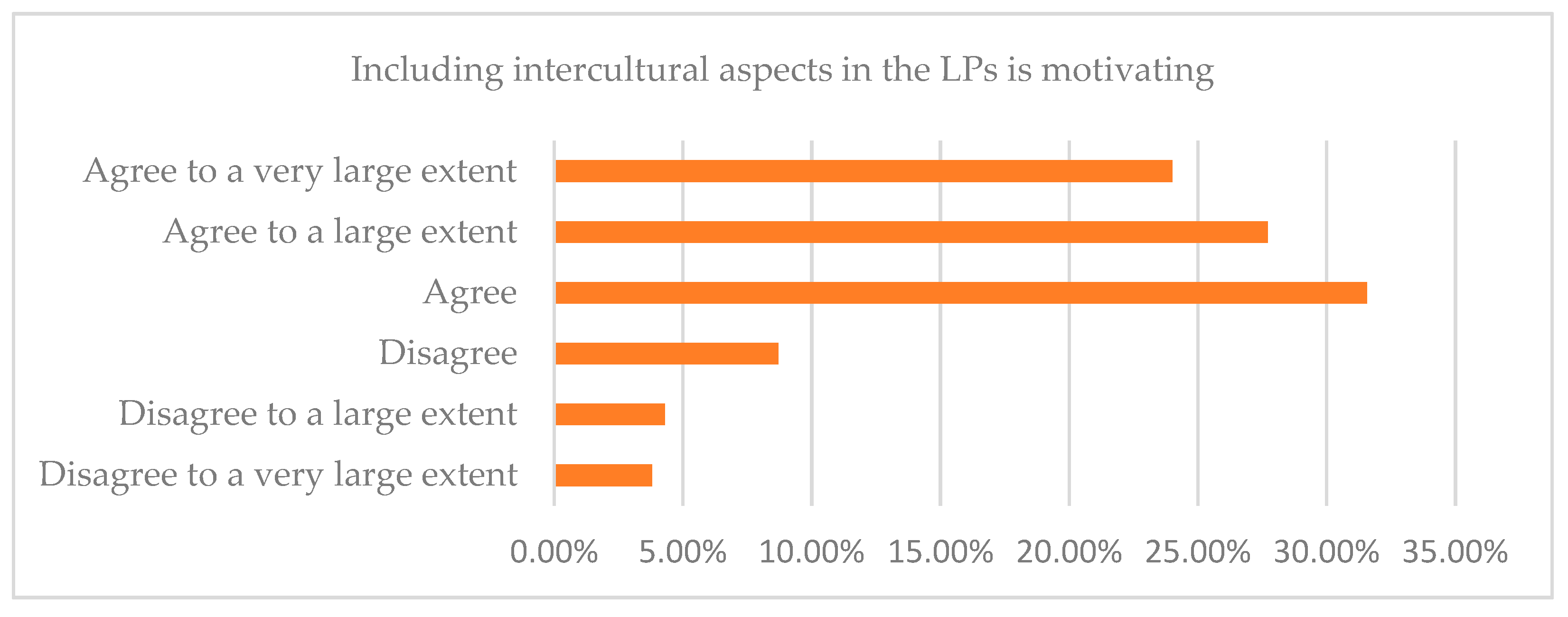

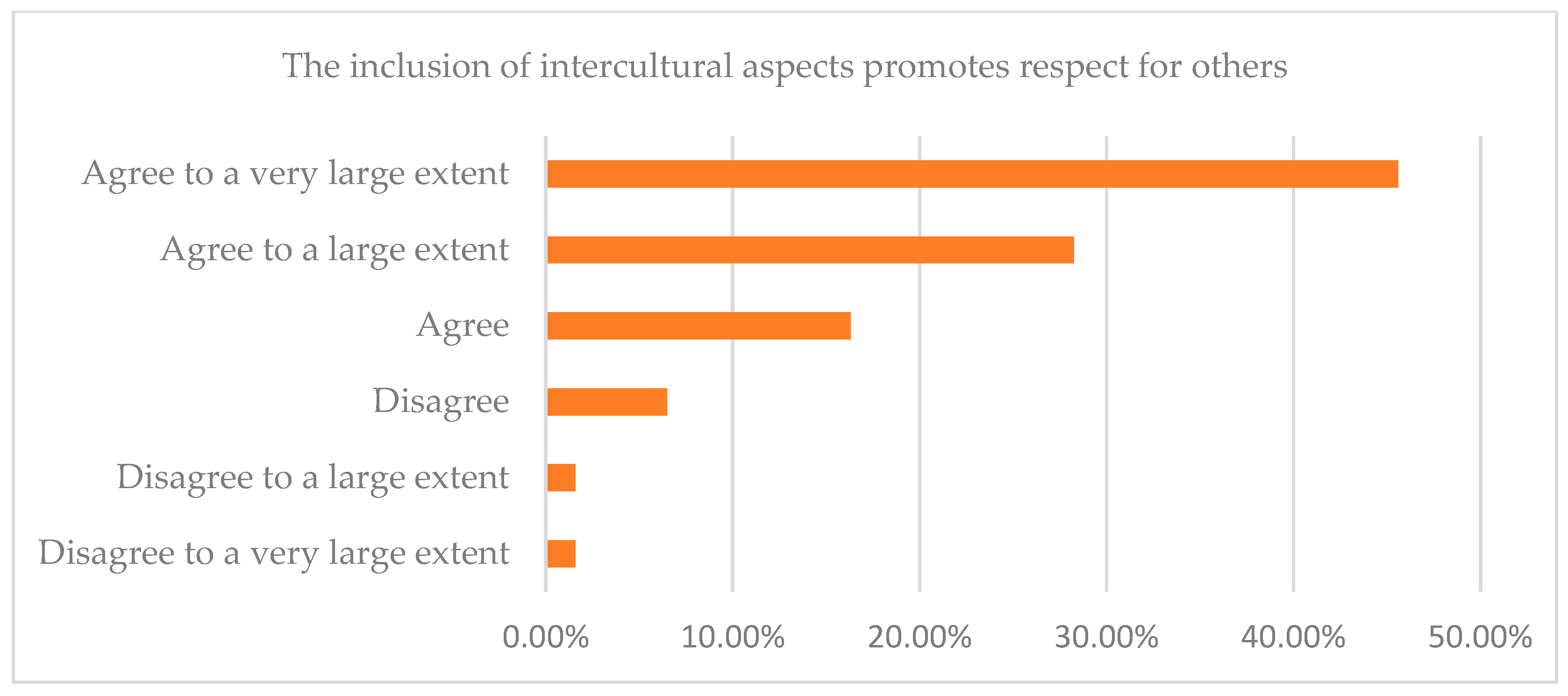

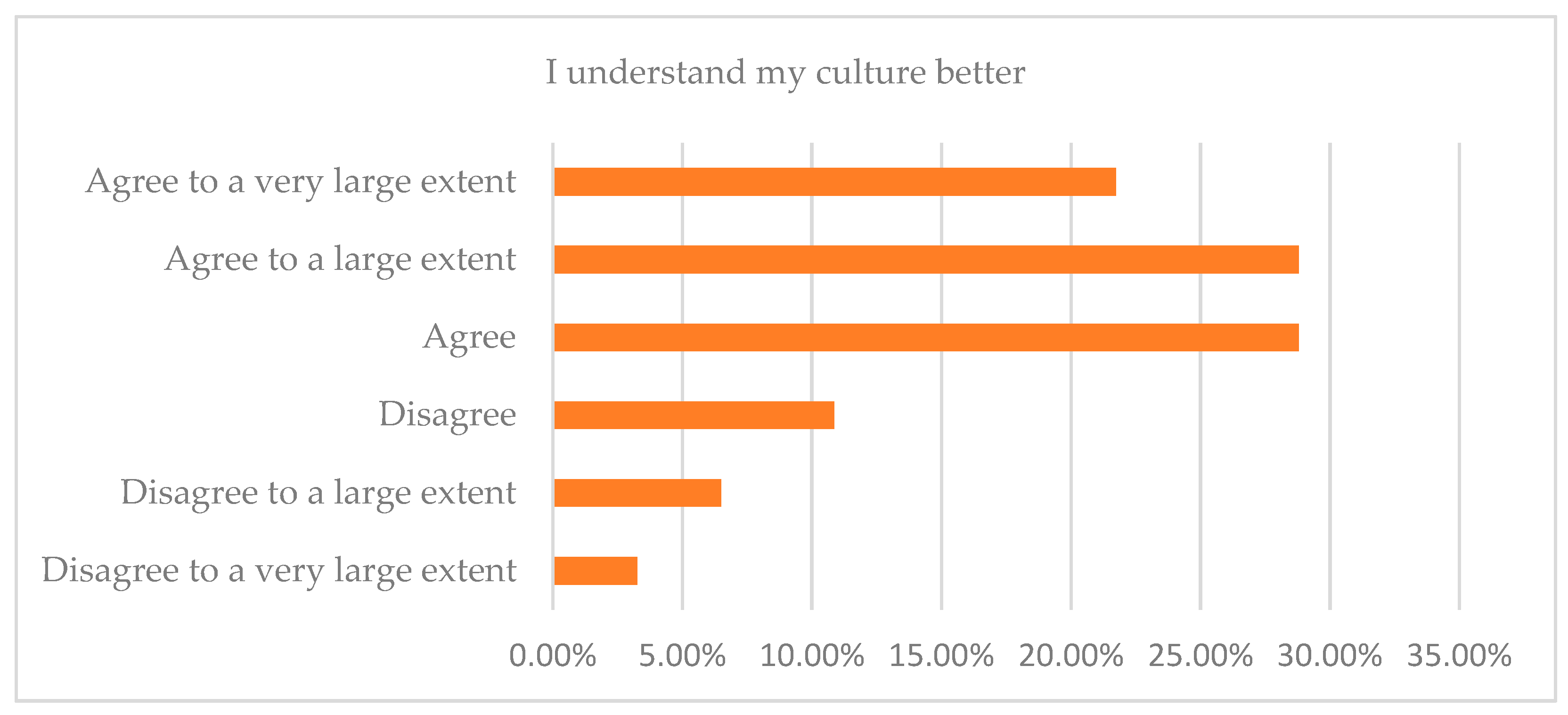

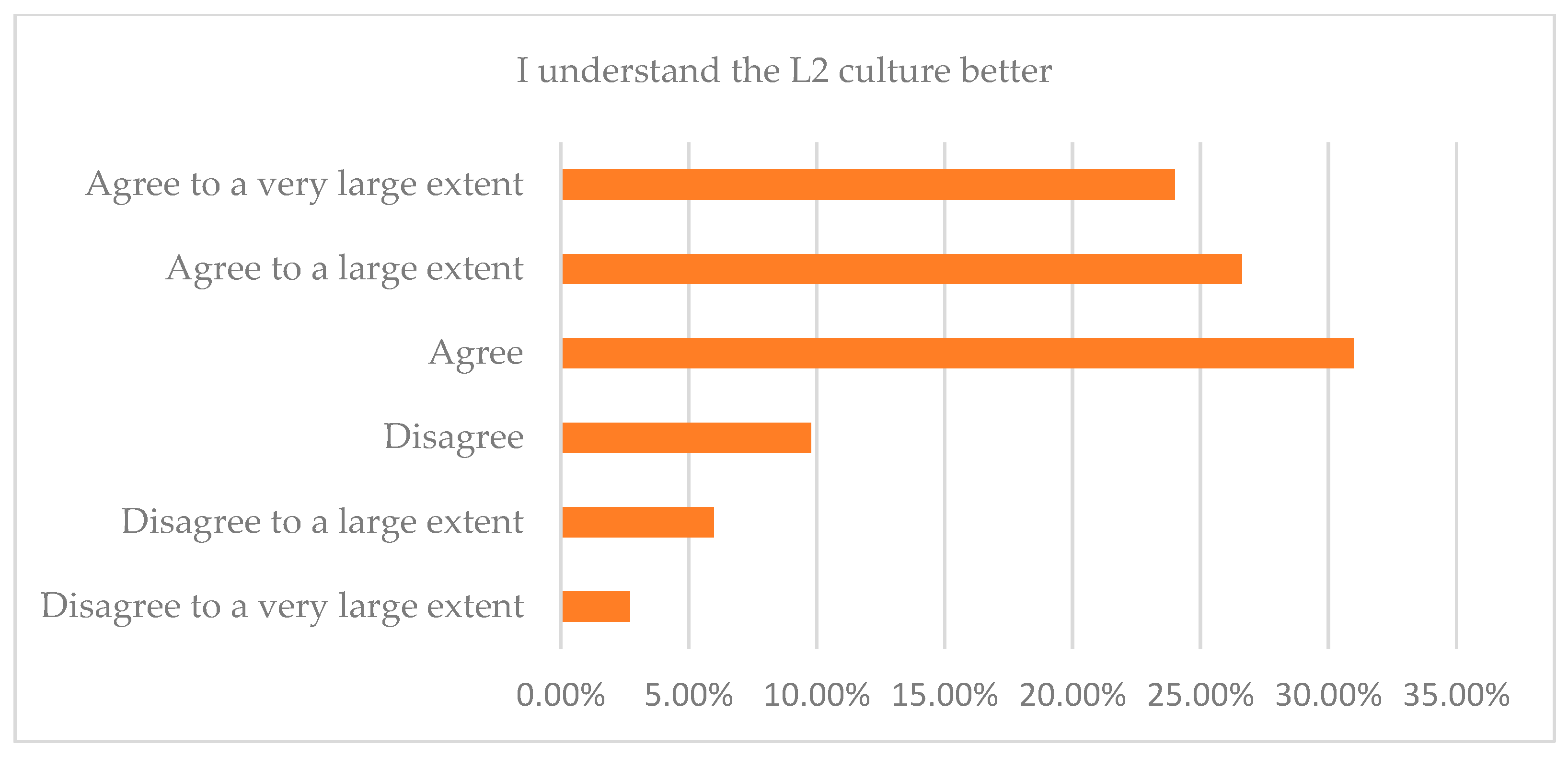

5. Results

6. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Aegisub: https://aegisub.org/, accessed on 31 May 2023. |

| 2 | Windows MovieMaker: https://apps.microsoft.com/store/detail/movie-maker-video-editor/9MVFQ4LMZ6C9?hl=es-es&gl=es, accessed on 31 May 2023. |

References

- Aguado Odina, Teresa. 2003. Pedagogía Intercultural. Madrid: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Cabrera, José J., and Pilar Rodríguez-Arancón. 2021. The use of active subtitling activities for students of Tourism in order to improve their English writing production. Ibérica: Revista de la Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos 41: 155–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Cabrera, José J., and Pilar Rodríguez-Arancón. Forthcoming. The TRADILEX Project: Dubbing in foreign language learning within an integrated skills approach. In Empirical Studies in Didactic Audiovisual Translation. Abingdon: Routledge, in press.

- Baños, Rocío, Anna Marzà, and Gloria Torralba. 2021. Promoting plurilingual and pluricultural competence in language learning through audiovisual translation. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts 7: 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, Julie, and Steven L. Thorne. 2006. Internet-Mediated Intercultural Foreign Language Education. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. [Google Scholar]

- Benet Gil, Alicia, María Odet Moliner García, and María Auxiliadora Sales Ciges. 2020. Cómo somos, qué queremos y compartimos. Percepciones y creencias acerca de la cultura intercultural inclusive que promueve la Universidad. Revista de la Educación Superior 49: 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Borghetti, Claudia, and Jennifer Lertola. 2014. Interlingual subtitling for intercultural language education: A case study. Language and Intercultural Education 14: 423–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, Michael. 1997. Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Calduch, Carme, and Noa Talaván. 2018. Traducción audiovisual y aprendizaje del español como L2: El uso de la audiodescripción. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching 4: 168–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. 2020. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Companion Volume with New Descriptors. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Couto-Cantero, Pilar, Mariona Sabaté-Carrové, and María Carmen Gómez Pérez. 2021. Preliminary design of an Initial Test of Integrated Skills within TRADILEX: An ongoing project on the validity of audiovisual translation tools in teaching English. REALIA. Research in Education and Learning Innovation Archives 27: 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, Darla K. 2006. The Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence. Journal of Studies in International Education 10: 241–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, Darla K. 2009. The Sage Handbook of Intercultural Competence. Thousand Oakes: Sage Publication, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Cintas, Jorge. 2019. Audiovisual translation in mercurial mediascapes. In Advances in Empirical Translation Studies. Edited by Meng Ji and Michael Oakes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 177–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fantini, Alvino. 2009. Assessing intercultural competence: Issues and Tools. In The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence. Edited by Darla K. Deardorff. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 456–76. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Costales, Alberto. 2021. Subtitling and Dubbing as Teaching Resources in CLIL in Primary Education: The Teachers’ Perspective. Porta Linguarum 36: 175–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Costales, Alberto, Noa Talaván, and Antonio J. Tinedo-Rodríguez. 2023. Didactic audiovisual translation in language teaching: Results from TRADILEX. Comunicar Revista Científica de Comunicación y Educación 77: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Parra, María E. 2020. Measuring intercultural learning through CLIL. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 9: 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, Anita. 2011. Internationalization of Higher Education: Preparing Faculty to Teach Cross-culturally. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 23: 373–81. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, Zehra. 2018. International Mindedness and Intercultural Competence: Perceptions of Pakistani Higher Education Faculty. Journal of Education and Educational Development 5: 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, Carmen, and Isabelle Vanderschelden. 2019. Using Film and Media in the Language Classroom: Reflections on Research-Led Teaching. Bristol: Multiligual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Ibañez Moreno, Ana, and Anna Vermeulen. 2014. La audiodescripción como recurso didáctico en el aula de ELE para promover el desarrollo integrado de competencias. In New Directions on Hispanic Linguistics. Edited by Rafael Orozco. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 263–92. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Qinxu, Shimin Soon, and Yuandong Li. 2021. Enhancing teachers’ intercultural competence with online technology as cognitive tools: A literary review. English Language Teaching 14: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramsch, Claire. 1993. Context and Culture in Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kramsch, Claire. 1998. Language and Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krashen, Stephen D. 1988. Second Language Acquisition and Second Language Learning. Prentice-Hall: Prentice Hall International. [Google Scholar]

- Lertola, Jennifer. 2018. From translation to audiovisual translation in foreign language learning. TRANS 22: 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertola, Jennifer. 2019a. Audiovisual Translation in the Foreign Language Classroom: Applications in the Teaching of English and Other Foreign Languages. Viollans: Research-publishing.net. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertola, Jennifer. 2019b. Second language vocabulary learning through subtitling. Revista española de lingüística aplicada/Spanish Journal of Applied Linguistics 32: 486–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustig, Myron W., and Jolene Koester. 1993. Intercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication across Cultures. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Malmqvist, Johan, Kristina Hellberg, Gunvie Möllås, Richard Rose, and Michael Shevlin. 2019. Conducting the pilot study: A neglected part of the research process? Methodological findings supporting the importance of piloting in qualitative research studies. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, Laura Incalcaterra, and Jennifer Lertola. 2016. Traduzione audiovisiva e consapevolezza pragmatic nella classe d’italiano avanzata. In Orientarsi in rete. Didattica delle lingue e tecnologie digitale. Edited by Donatella Troncarelly and Matteo La Grassa. Siena: Becarelli, pp. 244–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mede, Enisa, and Zeynep Mutlu Cansever. 2016. Integrating Culture in Language Preparatory Programs: From the Perspectives of Native and Non-native English Instructors in Turkey. In Intercultural Responsiveness in the Second Language Learning Classroom. Edited by Kathryn Jones and Jason R. Mixon. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Pamala V., and Shalyse I. Isemiger. 2017. Understanding the Basics of Culture. In Communicating across Cultures, 10th ed. Edited by Pamala V. Morris. New York: Pearson, pp. 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete, Marga. 2020. The use of audio description in foreign language education: A preliminary approach. In Audiovisual Translation in Applied Linguistics: Educational Perspectives. Edited by Laura Incalterra, Jennifer Lertola and Noa Talaván. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 131–52. [Google Scholar]

- Plaza Lara, Cristina, and Carolina Gonzalo Llera. 2022. La audiodescripción como herramienta didáctica en el aula de lengua extranjera: Un studio piloto en el marco del Proyecto TRADILEX. DIGILEC Revista Internacional de Lenguas y Culturas 9: 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risager, Karen. 2007. Language and culture: Global flows and local complexity. Journal of Pragmatics 39: 436–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Arancón, Pilar. 2023. How to Develop and Evaluate Intercultural Competence in a Blended Learning Environment. Madrid: Sindéresis. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Requena, Alicia. 2020. Intralingual dubbing as a tool for developing speaking skills. In Audiovisual Translation in Applied Linguistics: Educational Perspectives. Edited by Laura Incalterra, Jennifer Lertola and Noa Talaván. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 104–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Requena, Alicia, Paula Igareda, and María Bobadilla-Pérez. 2022. Multimodalities in didactic audiovisual translation: A teachers’ perspective. Current Trends in Translation Teaching and Learning 9: 337–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoli, Stavroula, and Patrick Zabalbeascoa. 2019. Audiovisual Activities and Multimodal Resources for Foreign Language Learning. In Using Film and Media in the Language Classroom. Edited by Carmen Herrero and Isabelle Vanderschelden. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 170–87. [Google Scholar]

- Talaván, Noa. 2013. La subtitulación en el aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras. Barcelona: Octaedro. [Google Scholar]

- Talaván, Noa. 2019. Using subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing as an innovative pedagogical tool in the language class. International Journal of English Studies 19: 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaván, Noa. 2020. The didactic value of AVT in foreign language education. In The Palgrave Handbook of Audiovisual Translation and Media Accessibility. Edited by Łukasz Bogucki and Mikołaj Deckert. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 567–92. [Google Scholar]

- Talaván, Noa, and Jennifer Lertola. 2016. Active audiodesciption to promote speaking skills in online environments. Sintagma 28: 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Talaván, Noa, and Jennifer Lertola. 2022. Audiovisual translation as a didactic resource in foreign language education. A methodological proposal. Encuentro 30: 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaván, Noa, and Pilar Rodríguez-Arancón. 2014a. The use of interlingual subtitling to improve listening comprehension skills in advanced EFL students. In Subtitling and Intercultural Communication. European Languages and Beyond. Edited by Beatrice Garzelli and Michela Baldo. Pisa: InterLinguistica, ETS, pp. 273–88. [Google Scholar]

- Talaván, Noa, and Pilar Rodríguez-Arancón. 2014b. The use of reverse subtitling as an online collaborative language learning tool. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 8: 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaván, Noa, and Pilar Rodríguez-Arancón. 2018. Voice-over to improve oral production skills. In Focusing on Audiovisual Translation Research. Edited by John D. Sanderson and Carla Botella. Valencia: Publicacions Universitat de Valencia, pp. 211–29. [Google Scholar]

- Talaván, Noa, and Pilar Rodríguez-Arancón. Forthcoming. Didactic Audiovisual Translation in Online Context: A Pilot Study. Hikma: Revista de traducción, in press.

- Talaván, Noa, and Tomás Costal. 2017. iDub—The potential of intralingual dubbing in foreign language learning: How to assess the task. Language Value 9: 62–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaván, Noa, Jennifer Lertola, and Ana Ibáñez. 2022. Audio description and subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing. Media accessibility in foreign language learning. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts 8: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaván, Noa, Jennifer Lertola, and Tomás Costal. 2016. iCap: Intralingual captioning for writing and vocabulary enhancement. Alicante Journal of English Studies 29: 229–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Catherine E. 2009. Interculturalidad, estado, sociedad. Luchas (de)colonials de nuestra época. Quito: Abyayala. [Google Scholar]

| SPEAKING | Poor (0–5%) | Adequate (6–10%) | Good (11–15%) | Excellent (16–20%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation and intonation | ||||

| Range of vocabulary | ||||

| Grammar | ||||

| Fluency | ||||

| General coherence |

| WRITING | Poor (0–5%) | Adequate (6–10%) | Good (11–15%) | Excellent (16–20%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spelling | ||||

| Grammatical precision | ||||

| Punctuation | ||||

| Word usage | ||||

| Text composition, coherence and cohesion |

| PHASE | DESCRITION | OBJECTIVE |

|---|---|---|

| Warm-up Reception and/or production task (reading, writing, listening, speaking and/or mediation) 10 min | Anticipating video content, characters and events and presenting new vocabulary, structures or cultural information | To gather the necessary background knowledge to face the video viewing and the didactic AVT phases |

| Video viewing Reception and mediation task (listening, reading and mediation) 5/10 min | The video extract is watched at least twice, with or without subtitles, and accompanied by related tasks | To understand the messages to be translated and to become familiar with the key linguistic content |

| Didactic AVT Reception, production and mediation task (listening, writing and/or speaking, and mediation) 30 min | Students work on the AVT of the one-minute clip extracted from the video, making use of the recommended software in each case | To work on AV mediation skills and strategies and to develop lexical, grammatical and intercultural competence |

| Post-AVT task Production and/or reception task (writing, speaking, reading, listening and/or mediation) 15 min | Related production (and/or reception) tasks to practice elements present in the video | To make the most of the linguistic and cultural content of the video and to complement the previous mediation practice |

| DUBBING | Poor (0–5%) | Adequate (6–10%) | Good (11–15%) | Excellent (16–20%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linguistic accuracy (pronunciation and intonation) | ||||

| Lip synchrony | ||||

| Fluency and speed of speech (naturalness) | ||||

| Technical quality | ||||

| Dramatisation |

| Initial questionnaire |

| ITIS (Reception skills) (60′) by Couto-Cantero et al. (2021) ITIS (Production skills) (60′) by Couto-Cantero et al. (2021) |

| Lesson Plan 1 on subtitling: The worst that could happen (1 h) Lesson Plan 2 on subtitling: A shorter letter (1 h) Lesson Plan 3 on subtitling: If 2020 was a boyfriend (1 h) Lesson Plan 4 on voice-over: Why do languages borrow words (1 h) Lesson Plan 5 on voice-over: Brave art (1 h) Lesson Plan 6 on voice-over: The snow guardian (1 h) Lesson Plan 7 on dubbing: The controller (1 h) Lesson Plan 8 on dubbing: Alternative Math (1 h) Lesson Plan 9 on dubbing: Being good (1 h) Lesson Plan 10 on audio description: The right way (1 h) Lesson Plan 11 on audio description: Pip (1 h) Lesson Plan 12 on audio description: Too quick to judge (1 h) Lesson Plan 13 on subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing: Tangled (1 h) Lesson Plan 14 on subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing: Come prepared! (1 h) Lesson Plan 15 on subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing: New boy (1 h) |

| FITIS (Reception skills) (60′) by Couto-Cantero et al. (2021) FITIS (Production skills) (60′) by Couto-Cantero et al. (2021) |

| Final questionnaire |

| Certificate of participation |

| Initial questionnaire |

| ITIS (Reception skills) (60′) by Couto-Cantero et al. (2021) ITIS (Production skills) (60′) by Couto-Cantero et al. (2021) |

| Lesson Plan 1 on subtitling: One-minute time machine (1 h) Lesson Plan 2 on subtitling: Post-it (1 h) Lesson Plan 3 on subtitling: The milkman (1 h) Lesson Plan 4 on voice-over: What makes ‘Star Wars’ so immersive? (1 h) Lesson Plan 5 on voice-over: Machine learning (1 h) Lesson Plan 6 on voice-over: Creative sparks (1 h) Lesson Plan 7 on dubbing: Chicken (1 h) Lesson Plan 8 on dubbing: Alternative Math (1 h) Lesson Plan 9 on dubbing: Our prices have never been lower (1 h) Lesson Plan 10 on audio description: Eggs change (1 h) Lesson Plan 11 on audio description: Pip (1 h) Lesson Plan 12 on audio description: Too quick to judge (1 h) Lesson Plan 13 on subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing: In a heartbeat (1 h) Lesson Plan 14 on subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing: Who are you? (1 h) Lesson Plan 15 on subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing: The mirror (1 h) |

| FITIS (Reception skills) (60′) by Couto-Cantero et al. (2021) FITIS (Production skills) (60′) by Couto-Cantero et al. (2021) |

| Final questionnaire |

| Certificate of participation |

| (a) Inclusion of Cultural Aspects Is Motivating | (b) Cultural Contents Foster Respect for Other Cultures | (c) Improvement of Understanding of Own Culture | (d) Improvement of Understanding of L2 Culture | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Inclusion of cultural aspects is motivating | Pearson correlation | 1 | 0.606 ** | 0.708 ** | 0.735 ** |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| n | 184 | 184 | 184 | 184 | |

| (b) Cultural contents foster respect for other cultures | Pearson correlation | 0.606 ** | 1 | 0.603 ** | 0.630 ** |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| n | 184 | 184 | 184 | 184 | |

| (c) Improvement of understanding of own culture | Pearson correlation | 0.708 ** | 0.603 ** | 1 | 0.882 ** |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| n | 184 | 184 | 184 | 184 | |

| (d) Improvement of understanding of L2 culture | Pearson correlation | 0.735 ** | 0.630 ** | 0.882 ** | 1 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| n | 184 | 184 | 184 | 184 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Arancón, P. Developing L2 Intercultural Competence in an Online Context through Didactic Audiovisual Translation. Languages 2023, 8, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030160

Rodríguez-Arancón P. Developing L2 Intercultural Competence in an Online Context through Didactic Audiovisual Translation. Languages. 2023; 8(3):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030160

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Arancón, Pilar. 2023. "Developing L2 Intercultural Competence in an Online Context through Didactic Audiovisual Translation" Languages 8, no. 3: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030160

APA StyleRodríguez-Arancón, P. (2023). Developing L2 Intercultural Competence in an Online Context through Didactic Audiovisual Translation. Languages, 8(3), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030160