1. Introduction

A writing system can be employed in multiple languages, e.g., Latin alphabet, Arabic alphabet, and Brahmic scripts. Sometimes, the symbols are modified in order to adapt to the target languages. For example, Chinese characters have been “loaned” to many nearby ethnic groups in history, including Korean, Vietnamese, Japanese, Khitan, Jurchen, Tangut, Sawndip Zhuang, Sinoxenic Bai, Bouyei, and Sui (cf.

Zhao and Song 2011;

Poupard 2022). These varieties of Chinese developed into the cluster known as sinography (

Handel 2018).

Among the ethnic writing systems in China, Dongba script is one of the few unique pictographic scripts still in use in the world, known as a “living fossil” among the writing systems (

Song 2010, p. 31). Dongba manuscripts, the ritual texts written using Dongba script, were declared a World Memory Heritage by UNESCO in 2003.

This hieroglyph shows resemblance to sinographs dating back to an earlier stage. As Dong Zuobin described, Dongba script represents the childhood of a writing system (

Li et al. 1972, p. 3).

Y. Wang (

1988, pp. 150–52) compared the correspondence between written symbols and linguistic units and pointed out that ancient Chinese scripts, such as the oracle bone script and bronze inscriptions, are word-syllabic writing systems, while Dongba Script is at a transitional stage between primitive script and word-syllabic writing system. According to

Zhou (

1994), among the glyphs documented in

Fang and He (

1981), 1076 are pictograms (47%), 761 compound indicatives and simple indicatives (33%), and 437 phonosemantic compound characters and phonetic loans (19%). In comparison to the statistics of Chinese, Dongba script is close to the stage of the oracle bone script. The percentage of phonosemantic compound characters accounts for around 20% of the oracle bone script and increases to 82% in the small seal script (7697/9553).

The creator of Dongba script remains unknown.

Fang and He (

1981, pp. 38–40) listed three legends about the origin of Dongba script and stated that Dongba script could have a long history; however, the creator cannot be identified.

J. Li (

2009, pp. 5–16) took Dongba pictographs as references to reconstruct the customs of Moso in history and concluded that Dongba script underwent a long endeavor before becoming a writing system.

Jiang (

1984) pointed out that Dongba script existed before the Song dynasty, since feudal society was described in

Mushi Huanpu (“The Genealogy of Mu Family”), the historical literature about the Naxi lords.

G. Li (

1986) assumes that it could date back to the 7th century. This assumption, however, has not been corroborated, and Western scholarship tends to date the script much later than early Chinese scholarship: the consensus seems to be that it does not predate the 13th century and may be much more recent (

Jackson 1979, pp. 59–62).

Dongba script is named after the shamans of Moso (/to˧mbɑ˩/, derived from the Tibetan word “སྟོན་པ ston pa”). “Moso” is the conventional name used to refer to this ethnic group, which dates back to the Jin dynasty (317~420 AD) and was used until the 1950s. The endonyms of Moso People generally consist of the syllable “na” (/nɑ˨˦/), which is homophonic to the word for “black” and “noble”, and the word for “people” (e.g., /ɕi˧/, /hĩ˧/, /zɯ˧/). Therefore, in some contemporary research, Moso is addressed as “Naish People”. Meanwhile, the term “Moso” is still kept as the official endonym of some minor branches living in Yunnan province.

During the nationwide identification of ethnic groups, the western branch of Moso was assigned a new designation, “Naxi” (/nɑ˩ɕi˧/), based on the related endonym, in 1954 (

Zhiwu He 1989, p. 3). “Naxi” and “Na” are often used as the name of the linguistic variety, with the addition of the designation of the branch or location, such as “Yongning Na” (

Lidz 2010), “Daju Naxi” (

Zhili He 2017).

Ruke (/ʐɯ˧kʰʌr˧/) is a branch of Moso with a population of around 7000 who live in Labo township, Ninglang county; Shangrila township, Sanba county; Luoji county, Yunnan province; and the Yiji and E’ya townships of Muli county. The transliteration “Ruke”, in the present study, is based on the accent of the Ruke Naxi in Yomi (/jo˩mi˧/) village, Labo township, Ninglang county, Yunnan province, one of the major hamlets of Ruke Naxi, and has obtained approval of the native speakers. Before that, the endonym of Ruke was transliterated as “zher-khin” (

Rock 1937), “Ruoka” (/ʐur˧k‘ɑ˧/;

Li et al. 1972, p. 125), “Ruanke” (/ʐʅ˧kho˧/;

He and Guo 1985, p. 40;

Guo and He 1999, p. 7), and “Ruka” (/ʐuə˧khɑ˧/, /ʐuə˧kho˧/, /ʐʅ˧tɑ˧/;

Zhong 2010b, p. 132).

Being a cultural and linguistic branch of Dongba, Ruke Naxi is characterized by dialectal distinctions as well. There are some descriptions of Ruke Naxi, e.g.,

Rock (

1937),

Li et al. (

1972),

Zhong (

2010a),

Lijiangshi Dongba Wenhua Yanjiuyuan (

2018). The phonemic system in this article is elicited from my fieldwork data collected from Yomi village. Between 2011 to 2015, I interviewed Ruke Dongba priests from Yomi village. As an initial contact with Dongba culture, I collected around 3000 daily vocabularies in order to ascertain the phonemic system of Ruke Naxi, transcribed a number of sentences and narratives for grammar description, and interpreted a few Dongba scriptures. In 2022, I had the opportunity to work with Ruke Dongba priests on the interpretation of their hemerology.

Ruke Naxi maintains phonemic features of both Na and Naxi. For example, it contains pre-nasal initials similar to Naxi (e.g., /ndʐɯ˧/ “dew”, /dʐɯ˧/ “crime”; /dʏ˩/ “ground”, /ndʏ˩/ “stomach”), nasalized rhymes like in Na (e.g., /hʏ̃˩/ “red”; /hĩ˧/ “people”), and contrasts between retroflexive and alveolar initials are attested in a few words (e.g., /læ˧/ “telic”, /ɭæ˩/ “flat”; /lu˨˦/ “stone”, /ɭu˩/ “dragon”). Similar to Na and Naxi, the uvular plosives are conditional varieties of the corresponding velar initials.

2. Dongba Glyphs in Fieldwork

The linguistic value carried by a visual symbol varies from phoneme, syllable, word, phrase, and prosodic feature (

Gelb 1952, p. 14). As a mnemonic device, fully developed writing has close correspondence to the language, but encompasses all elements of speech (

Chao 1968, pp. 101–12). Basically speaking, a writing system is a conventional tool for communication. In addition to recording the original language, the scripts can also be used for other purposes, such as transcribing other languages and encryption.

There are plenty of discussions on the nature of Dongba script. Scholars have described it as “symbols for chapters” (

Zhou 1998, p. 59), “keywords of verses of traditional stories” (

Fu 1982, p. 6), “prompts for the chanting” (

Mair 2014), as well as “syllabic representation of the texts”, as attested in vernacular documents (

Yu 2003;

Poupard 2019, p. 54). Moreover, examples of varieties in the written forms of the same verses can be found in

X. Lin (

2002, p. 85).

He Zhiwu provided examples of three types of correspondences between Dongba pictographs and the oral chanting texts: (1) a few pictographs represent a passage of verses; (2) a few pictographs represent a verse; (3) each pictograph represents a word (

Fang and He 1981, pp. 494–564). As for the first type, the Dongba glyphs are organized as rebus. The same plot may be realized as distinctive verses.

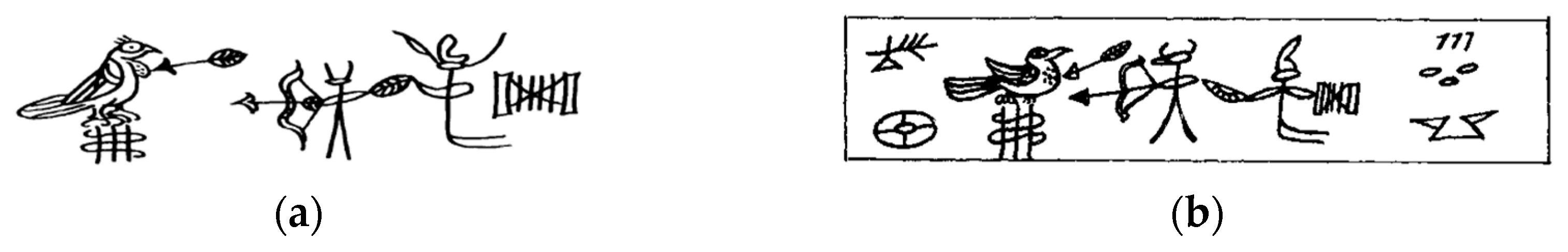

Figure 1 contains two similar grids of Dongba scriptures elicited from the

Genesis of Naxi, entitled “Comburtu” (/ts‘o˩mbur˧t‘u˧/, human–migrate–arrive) or “Cobbertv” (/ts‘o˨˩bər˧t‘v̩˧/). The tonal letters in the transcriptions of manuscript titles are omitted for abbreviation. Since there is contrast between /mb/ and /b/ in Ruke Naxi (as well as in Ludian naxi), /mb/ and /bb/ are applied to Romanized transcriptions of the manuscript titles in order to distinguish the two phonemes. On the other hand, minimal contrast is not attested between /u/ and /v̩/. Therefore, I use /u/ for both phonemes in the Romanized transcriptions. The text behind

Figure 1a consists of 14 verses and 78 syllables. The text corresponding to

Figure 1b consists of 13 verses and 79 syllables.

Bai (

2013) analyzed the evolution of linguistic units carried by Dongba script. The Dongba glyphs were divided into pictographs (“danzi 单字”), complex pictographs with loose combinations of units (“zhun hewen 准合文”), and complex pictographs—fusion units (“hewen 合文”). The translation of terms are quoted from

Zamblera (

2018). Under this framework, the author pointed out that the complex pictographs–fusion units were developed due to the correspondence between written symbols and speech, and the settings of handwriting.

Indeed, this ancient script evolved over time and is still evolving. Under this lens, the multiple characteristics of Dongba script reflect different phases of a writing system. Among the currently available repertoire, it has been used to transcribe traditional Dongba scriptures, secular documents in Naxi community, and Tibetan Buddhism sutras (cf.

Yu 2003;

Zhao 2011;

J. He 2018). In addition to functioning as a set of syncretistic paintings, it can be used in a syllabic mode, while homophonic variants could be chosen on a random basis to transcribe the syllables. In other words, Dongba script shows features of a logographic writing system. However, Dongba script is generally referred to as a pictographic writing system due to the form of its characters.

During the fieldwork, I occasionally witnessed Ruke Dongba glyphs being actively utilized to write down messages, words, and IPA symbols based on the Latin alphabet.

For example, the Dongba applied their pictographs to provide answers to questions, such as the pronunciation of barely used vocabularies.

Table 1 displays a list of words with Dongba script transcriptions collected during an interview with native speakers about their daily vocabulary. It was written by Dongba Yang in 2011. While Dongba Yang was interpreting the manuscripts with other team members, I was conducting language documentation with his brother, who had doubts about the expressions of some daily vocabularies. He collected the word list and consulted Dongba Yang in the evening and brought back the answers written using Dongba pictographs the following day. With this reference, we filled these slots with IPA transcriptions.

Some of the loanwords are, in fact, translated with explanatory phrases. The word “weather” (/mɯ˧dʑɑ˨˦mɯ˧ndzɑ˧/, sky–good–sky–bad), literally means “sunny or rainy”; the word “school” (/tʰe˧ɯ˧-so˧-sæ˧/, book–study–compl.) is translated as “(the place) studied book(s)”; and the word “prison” (/lo˩dʑi˧/, prison–house), also shows to be an explanatory compound. Some pictographs are used repeatedly for the transcription. However, the syllables written with the same pictographs may vary in tones and rhymes, as spotted in “thunder” and “armpit”, “leprosy” and “corpse”, “steam” and “breathe”, and “brow bone” and “bridge of the nose”.

The flexibility in the correspondences between rhymes and tones with the actual syllables is represented by “Guzong Yinzi” (古宗音字 “Tibetan syllabics”) as well. It is a subcategory of Dongba glyphs transcribing Tibetan syllables. “Guzong” is the Chinese transliteration of the designation of “Tibetan” in local languages: /ɡv̩˧dzɯ˩/ (Naxi;

Li et al. 1972, p. 41), /ʁu˧dzɯ˩/ (Na; my fieldwork notes). Among the 32 Guzong glyphs documented in

Li et al. (

1972, pp. 128–30), 5 belong to the “Qieyin” category (切音 “combination of the initial and the rhyme”;

J. He 2013). It is possible to notice that the initials of the Guzong syllabary and the glyphs providing initials are identical, while the rhymes do not distinguish strictly between /ɑ/ and /ʌ/, and the tones do not either (cf. No. 1685, No. 1689, No. 1693, and No. 1706).

In another instance, Dongba script was employed to send a message between Dongba priests. The original image and Dongba text, along with Chinese translation, can be found in

Zhao (

2011, p. 77). It was compiled by Dongba Yang in 2010. This message was a letter of introduction for the visitor to take a look at the collection of manuscripts of his colleague Dongba Shi, who lives in Shuzhi, another hamlet belonging to Jiaze Village, like Yomi. With this bilingual note, Prof. Zhao was received by Dongba Shi and received access to his collection, which Dongba Yang does not have. According to the catalogue of fieldwork data (which I helped to systematize), the collection of Dongba Shi amounted to 78 out of the 487 Ruke Dongba manuscripts preserved in Jiaze Village, Labo Township, Ninglang County.

| 1. | a. | Dongba | ![Languages 08 00162 i048]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i049]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i050]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i051]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i052]() | |

| | | IPA | jɑ˩ | po˨˦ | ʂo˩ | ɡɯ˩ | zɯ˧: | |

| | | Ch. | 杨 | 宝 | 寿 | 弟 | |

| | | En. | Yang Baoshou | Younger brother | |

| | b. | Dongba | ![Languages 08 00162 i053]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i054]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i055]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i056]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i057]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i058]() |

| | | IPA | pe˧ | tɕi˧ | hĩ˧ | ni˧ | ni˧ | me˧ |

| | | Ch. | 北京 | 人 | (施事) | 要 | (肯定) |

| | | En. | Beijing | People | agt | Need | cert.m |

| | c. | Dongba | ![Languages 08 00162 i059]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i060]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i061]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i062]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i063]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i064]() |

| | | IPA | tʰe˧ | ɯ˧ | ŋɑ˧ | mɑ˧ | ndʑʏ˧ | me˧ |

| | | Ch. | 经书 | 我 | 没 | 有 | (肯定) |

| | | En. | Manuscript | I | neg | Have | cert.m |

| | d. | Dongba | ![Languages 08 00162 i065]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i066]() | | | |

| | | IPA | ʌr˨˦ | pʏ˩ | me˧, | | | |

| | | Ch. | 骨节 | 诵 | (肯定) | | | |

| | | En. | Bone joint | To chant | cert.m | | | |

| | e. | Dongba | ![Languages 08 00162 i067]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i068]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i069]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i070]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i071]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i072]() |

| | | IPA | ɯ˧ | kʰo˨˦ | ʂu˩ | ɖɯ˩ | be˩ | me˧, |

| | | Ch. | 牛 | 杀 | 除秽 | 做 | (肯定) |

| | | En. | Bull | To kill | To exorcise misfortune | Do | cert.m |

| | f. | Dongba | ![Languages 08 00162 i073]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i074]() | | |

| | | IPA | ʈɯ˧ | zɯ˧ | (jʌ˩) | me˧ | | |

| | | Ch. | 凶鬼 | 掌控 | (压) | (肯定) | | |

| | | En. | “Dee” ghost | Control | (To suppress) | cert.m | | |

| | g. | Dongba | ![Languages 08 00162 i075]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i076]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i077]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i078]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i079]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i080]() |

| | | IPA | hĩ˧ | ɡʌ˨˦ | pɑ˧ | lɑ˩ | ɡu˩ | be˩ |

| | | Ch. | 人 | 上 | 拍照 | 整 | 做 |

| | | En. | People | Above | Take photo | Make | Do |

| | h. | Dongba | ![Languages 08 00162 i081]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i082]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i083]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i084]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i085]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i086]() |

| | | IPA | ɖɯ˩ | lʏ˩ | ni˧ | kʰo˧ | kɑ˧ | mu˧ |

| | | Ch. | 一 | 看 | (强调) | 放置 | 好 | (下) |

| | | En. | One | To look | emph | Settle | Good | prosp |

| | i. | Dongba | ![Languages 08 00162 i087]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i088]() | ![Languages 08 00162 i089]() | | | |

| | | IPA | jɑ˩ | ʈæ˧ | ɕi˩ | | | |

| | | Ch. | 杨扎实 | | | |

| | | En. | Yang Zhashi | | | |

| | | Trans. | “Shi Baoshou brother:

The manuscripts that Beijing people want which I do not have:

Xinjiu Kunhuo Jing (‘to clarify misunderstanding between the old and the new’),

Shaniu Xiaozai Jing (‘to exorcise misfortune by sacrificing cattle’),

Ya Xiongsigui Jing (‘to suppress ghosts who died in accidents’),

Please let them take a photo clearly!Yang Zhashi” |

This short text consists of 45 syllables, and every syllable has been transcribed. The titles of two Dongba manuscripts are written with complex pictographs–fusion units (“hewen 合文”), while the other multisyllabic words are written syllable-by-syllable, with basic pictographs (“danzi 单字”). Among these 42 glyphs (consisting of 45 components), 8 pictographs retain their original meanings, namely: “people” (2), “I”, “bone joint” (the lower part of the glyph

![Languages 08 00162 i090]()

), “bull”, “to kill”, “‘Dee’ ghost” (the lower part of the glyph

![Languages 08 00162 i091]()

), and “to look”. The former four cases are common nouns, while the latter four cases are attested in the titles of Dongba manuscripts. The other ones are used as phonetic loans, which account for 82.2% of all the components in this message.

Another cultural fact that can be highlighted from this text is Dongba Shi’s surname. In the original message, he is addressed with the same surname as Dongba Yang (

![Languages 08 00162 i092]()

). Despite the divergence in their Chinese surnames, indeed, that is one of the four traditional Naxi clans.

3. Learning Notes of IPA

In contemporary linguistic studies, the IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) is a universal tool used for language documentation. These phonetic notations provide details of pronunciation that an alphabetic writing system does not manifest (

Phonetic Teachers’ Association 1888). The IPA has undergone revisions ever since. Scholars working on Chinese also created symbols for sounds attested in Chinese languages, e.g., the vowels /ɿ/ and /ʅ/ (

Karlgren [1915] 1940), and tonal letters (

Chao 1930). The latest version was released in 2015.

Dongba script is a syllabic and pictographic writing system. Besides IPA transcriptions, other approaches have been used to depict the pronunciations of the glyphs. For example, since IPA is not conventional to users of logographic scripts,

Li et al. (

1978, p. 14–18) created a chart of corresponding Chinese characters with Moso/Naxi syllables.

Conversely, Dongba script is an efficient tool for Dongba priests to mark phonetic value. Two learning notes of IPA are interpreted in

Xu (

2022). The two notes were compiled by Ruke Dongba priests during their field work interviews at Tsinghua University in 2011. In one of the notes, compiled by Dongba Yang, the Dongba glyphs were chosen to represent initials and rhymes, respectively. In the other note, compiled by Dongba Shi, there are 88 syllables, with distinctions between velar and uvular initials, alveolar and retroflexive initials, and without distinctions between alveolar nasal and alveolo-palatal nasal, without distinctions of tones among the syllables.

These two learning notes show Dongba priests’ observations and reflections on their own language with their script considered as a technical tool. Dongba glyphs transcribed initials quite efficiently, such as in the complementary distribution pattern of velar and uvular consonants, while it was difficult for Dongba glyphs to differentiate rhymes and tones due to their intrinsic nature. They reflect the phonemic system of Yomi Ruke in a “natural” status before phonological analysis. Further on, they contribute to the current techniques of conversion between syllabic scripts and target languages. The notes, therefore, can be interpreted as a simulation of the evolution of Dongba pictographs towards Geba script, i.e., of a logographic script towards a syllabic writing system.

Table 2 displays 134 Ruke Dongba glyphs used to transcribe IPA symbols and syllables, which represent 106 syllables in Ruke Naxi. The Dongba glyphs from the two learning notes are reorganized according to their pronunciations, after removing the mismatched ones. The heading of the row consists of 10 monophthongs. The column consists of 44 initials (including the two glides, /j/ and /w/). Other four words with glides in the rhymes are attested, namely,

![Languages 08 00162 i093]()

/

![Languages 08 00162 i094]()

/nɖwɑ˧/ “pond”,

![Languages 08 00162 i095]()

/hwæ˩/ “stream (cl.)”,

![Languages 08 00162 i096]()

/ʈʰwʌ˧/ “drop”,

![Languages 08 00162 i097]()

/ʐwʌ˧/, along with one word with nasalized rhymes,

![Languages 08 00162 i098]()

/hĩ˧/ “people”. The numbers after the glyphs indicate that the same glyphs were used repeatedly. The variants of the glyphs are shown in the table for completeness of information.

Dongbawen Guifan Shiyong Shouce (“Practical Manuscript of Normalized Dongba Script”, pp. 96–97), published in

Lijiang Shi Gucheng Qu Wenhua Tiyu Guangdian Xinwen Chuban Ju (

2017), contains a table that displays a complete syllabary of the Naxi language (Dayan dialect), corresponding to the Naxi Dongba glyphs. There are 33 initials (31 consonants, 2 glides), 19 rhymes (11 monophthongs, 8 rhymes with glides), and 247 syllables documented in the chart. According to the table of syllabaries in Naxi displayed in

Li (

1984, pp. 173–74), there are 372 combinations among initials and rhymes, without a distinction of the tones. In comparison, 111 syllables, represented by 140 glyphs, are documented in the two learning notes of the IPA by Ruke Dongba priests. They account for between one-third to half of the total number of syllables in Naxi.

As mentioned above, the application of pictographs to transcribe IPA symbols emblematized the initial attempt to analyze the language. Similarly, the history of traditional Chinese phonology can be traced back to the late Han dynasty (25–220 AD), when “Fanqie 反切” was invented to annotate the pronunciation of Chinese characters (

Y. Lin 1959, pp. 107–8). In the traditional dictionaries of rhymes, Chinese characters were used to name the clusters of initials and the sections of rhymes. For example, the

sramana Shouwen, who lived during the late Tang dynasty, used 30 Chinese characters to represent the initials in Chinese. This set was expanded to 36 characters during the Song dynasty. These initials are categorized into seven groups according to the articulations, namely: lips (for labial, plosives, and nasals), tongue (for dental and retroflexive, plosives, and nasals), tooth-head (for alveolar and retroflexive, affricates, and fricatives), back-tooth (for velar, plosives, and nasals), throat (for laryngeals), half-tongue (lateral approximant), and half-tooth (alveolo-palatal nasal; cf.

L. Wang 1980, pp. 61–62;

Baxter 1992, pp. 45–60). In another instance, 206 characters were chosen to stand for the rhymes (61 clusters after removing the distinctions among the tones) in

Guangyun, a dictionary of Chinese from the 11th century.

4. Tendency of Romanization of Writing Systems

Naxi people have developed different types of writing systems, such as the pictographic Dongba script, syllabic Geba script, and phonemic Naxi

pinyin. Geba is a script invented after the Dongba hieroglyphs, not earlier than the 7th century. The creator could be considered

Acong, who lived in the 13th century (

Zhiwu He 1989, pp. 75–76). Conversely, according to

Li et al. (

2001, pp. 428–32), it was created by Dongba

He Wenyu, who lived during the late Qing dynasty, in the last century.

In

Li et al. (

2001), the Geba script contains 2411 symbols for 241 syllables. Among them, glyphs for 17 syllables distinguish the tones, including: /p‘ɯ/, /mu/, /mo/, /fu/, /ts‘ɯ/, /ts‘o/, /sɯ/, /ndʐæ/, /ʂɯ/, /ru/, /tɕi/, /hæ/, /hɯ/, /k‘wɑ/, /æ/, /i/, /o/. For the syllable /tɕi/, the syllabaries for tones 55 and 33 are not distinguished, while there are glyphs specifically used to transcribe syllables with tone 31. Each syllable may correspond to multiple glyphs.

Fang and He (

1981, pp. 369–481) recorded 688 symbols for 249 syllables in Naxi, among which 41 syllables remain without corresponding Geba symbols, namely: /pæ/, /pə/, /p‘o/, /my/, /mo/, /mv̩/, /fe/, /fæ/, /tə/, /t‘y/, /t‘ə/, /t‘ər/, /ni/, /nər/, /læ/, /lə/, /k‘uə/, /ŋæ/, /ŋɑ/, /ɣə/, /tɕæ/, /tɕɑ/, /tɕo/, /tɕ‘æ/, /tɕ‘ɑ/, /tɕ‘o/, /tɕ‘ə/, /dʑæ/, /dʑər/, /ȵæ/, /ȵɑ/, /ɕæ/, /ɕɑ/, /ɕo/, /dʐə/, /dʐuɑ/, /tsy/, /dzɑ/, /zi/, /iæ/, and /iɑ/. According to the

E-Dongba font database, the first keyboard for inputting Dongba hieroglyphs and Geba syllabaries, 661 Geba glyphs are included.

In general, Geba is a script that is still at an early stage of development and evolution. There are variants, missing syllables, unfixed tones, and irregular additional symbols. However, in comparison to the Dongba script, Geba can transcribe oral texts syllable by syllable.

Naxi

pinyin, on the other hand, was initially developed by linguists in the 1950s and completed in the 1980s (

He and Jiang 1985, pp. 130–31). As an alphabetic writing system, it transcribes the language in an accurate manner, and distinguishes the tones as well. Instead of being religious, as a script, in nature, this alphabetic script has been promoted as a standard writing system for the Naxi community.

A number of other ethnic groups, who live on the borderland of China, have also used writing systems of different types. Pumi people have an indigenous pictorial script used by priests called Hangui script, with signs for numbers and locations, while the Tibetan alphasyllabary is widely used (

Yan and Chen 1986, pp. 82–83). Tibetan script was formed in the 7th century, taking reference from Sanskrit (

Zhou 1958, pp. 101–2). The introduction of Tibetan script to Pumi was under the influence of Tibetan Buddhism. Similarly, Brahmic scripts are used throughout Southeast Asia due to the spread of Buddhism.

Latin alphabet, originated from ancient Rome, has been the writing system with the largest population around the world since the 19th century (

Haarmann 2004, p. 96). As attested in many ethnic communities, various

pinyin systems were developed based on the Latin alphabet in order to record languages before the introduction of IPA. For instance, since the beginning of the 20th century, Lisu people used alphabets called “Fraser script” (Old Lisu script) and “Frame script”, invented by missionaries, and the New Lisu script, an alphabetic writing system developed in the 1950s, along with a set of syllabaries (1051 logographs) invented by the peasant

NGual SSeix BBo (

Xu et al. 1986, pp. 114–26).

A number of ethnic groups adopted sinographs before Romanized

pinyin. Yi people maintain voluminous manuscripts written in logographic syllabaries, which were on a pictographic basis handed down by the shamans of Yi (

Bradley 2011;

Mueggler 2022). The priests of the Sui people use Sui script, which consists of ancient Chinese characters and pictograms, to write divination scriptures (

Zhang 1980, pp. 86–87). Zhuang people created “sawndip”, known as the old Zhuang characters, which was an ideographic script as well, consisting of components of Chinese characters (

Wei and Qin 1980, pp. 97–101;

Holm 2013). The same happened to the Bai, Hmong, Yao, etc., (

Nie 1998, pp. 30–34). Around China, among others, Chữ Nôm, in Vietnam, and Kana, in Japan, can be considered.

The Chinese script, with a vast literature of phonological studies of the language using logographs, is also equipped with a recently created alphabet. The preliminary Romanization of Chinese can be dated back to 1605, when Matteo Ricci wrote

Xizi Qiji 西字奇迹 (

Cordier 1904–1924, pp. 36, 77). Since then, a number of

pinyin were designed for Chinese. The widely used sets include but are not limited to the Wade System, postal Romanization, and Gwoyeu Romatzyh for Mandarin (

Luo 1959, pp. 6, 20–22). Besides language learning, the application of the Lundell alphabet and IPA brought historical reconstruction methodology to the studies on Chinese phonology (

International Phonetic Association 2008, p. 1).

Among these cases, it is possible to notice the influence of religious cults in the transmission of writing systems. The indigenous scripts of the Moso, Pumi, Lisu, Yi, Sui, and Zhuang people were mastered by priests of the local community. The broadly used scripts, such as Indic and Latin, were introduced to ethnic communities geographically distant from Buddhism and Christianity.

Worldwide, the development of writing systems shows a general tendency from primitive drawings to word-syllabic scripts, to syllabic writings, and to the alphabet (

Istrin 1987, pp. 550–51). Mesopotamian cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and Latin alphabet (derived from the ancient Greek alphabet), all went through, with their intrinsic differences, this process. Among other possible reasons, the need to record the language acts as an internal drive for the evolution of scripts (

Sun 2020, p. 13). The alphabet, as well as abugida, provides easier access to the pictographic or logographic scripts and to the language. Orthographies derived from alphabets function as the bridge between ideographs and their sounds. Further on, IPA, developed on the basis of the Latin alphabet, provides learners a more precise idea of the phonemic system.

5. Conclusions

The present study described the application of Ruke Dongba script in assisting fieldwork in the region. It documented two notes written using Ruke Dongba pictographs collected during linguistic fieldwork interviews. One served the purpose of transcribing daily vocabulary, which is not exactly an everyday practice for a hieroglyphic writing system such as Ruke Dongba script. Nevertheless, it proves useful in answering questions on the lexicons, as well as providing an additional reference for the scrutinization on the correspondences between the pictographs and IPA transcriptions. The other one was a short message between religious practitioners, in order to introduce a scholar in fieldwork to take a look at his special collection of Ruke Dongba manuscripts. These notes, compiled in indigenous script, facilitated the communication and language data collection during the fieldwork interview.

This article also analyzed two learning notes of IPA, by inserting the attested Dongba pictographs into the table of Ruke Naxi syllabary. The two Dongba priests selected different glyphs to record the IPA symbols for the phonemes in Ruke Naxi. Moreover, there are some mismatched cases according to the author’s fieldwork data. This table aimed at figuring out an accurate idea of the range of syllables covered in the two learning notes of IPA by Ruke Dongba priests. It compared the Dongba script with other syllabic scripts by analyzing the languages, dealing with phenomena such as the emergence of studies on Chinese rhymes in the seventh century.

These Dongba notes connected with IPA transcriptions provide reliable references for the analysis of the phonemic system of Ruke Naxi and the feature of Ruke Dongba script. Besides the dialectal variety behind these symbols, three of them are joined with language documentation, therefore, a contemporary discipline, which is beyond the other secular usages of Naxi Dongba recorded in several articles and books, including property deeds (the most ancient can be dated back to the Qing Dynasty, according to the chronology reconstructable using the texts), letters, banners, speeches, and panels findable everywhere in the town of Lijiang. Moreover, they can be interpreted in the context of the general tendency of Romanization spotted in Naxi, various ethnic communities in China, as well as other scripts around the world. In comparison to alphabets, IPA symbols carry fundamental descriptions of the language. With pictographic scripts, they facilitate language learning, fieldwork documentation, and allow a better understanding of non-alphabetic writing systems.

Ruke Dongba script is traditionally used in oral chanting texts. The related notes, naturally composed by Dongba priests, add new dimensions to this writing system. The application of this pictographic script in secular communications, as well as in the development of learning materials, makes manifest two facts: (1) it is an indispensable component of the life of Ruke Naxi people; (2) it is a well-rounded tool for recording the culture of Ruke Naxi.

The documentation of Ruke Dongba is at its initial stage, if compared to the work already conducted on Naxi Dongba. This study provides an interpretation of original documents of Ruke Dongba and produces an initial phonemic chart of Ruke Naxi corresponding to its indigenous script. It contributes to a clearer illustration of the phonemic system, with dual annotations in its own writing system and the IPA symbols. It may lead to a more accurate transcription of the manuscripts and, therefore, better understanding of this ancient culture. Furthermore, the present research is significant to the preservation and transmission of this endangered cultural heritage and the development of smoother everyday communication between Ruke Naxi and other ethnic groups.

This study is based on some pieces of secular Ruke Dongba documents generated during language description fieldwork. In addition to its linguistic value, the data under discussion also has value from an educational perspective and has a significant potential for both documentation of the language and writing of a community and interaction among speakers and learners. This original fieldwork experiment, conducted on the basis of the indigenous script, has shown to be efficient and inspiring. A similar procedure could be replicated, therefore, among other minority and/or aboriginal communities, which could lead to the development of a framework and/or protocol for both documenting and teaching language, producing a new standard for this method.

), “bull”, “to kill”, “‘Dee’ ghost” (the lower part of the glyph

), “bull”, “to kill”, “‘Dee’ ghost” (the lower part of the glyph  ), and “to look”. The former four cases are common nouns, while the latter four cases are attested in the titles of Dongba manuscripts. The other ones are used as phonetic loans, which account for 82.2% of all the components in this message.

), and “to look”. The former four cases are common nouns, while the latter four cases are attested in the titles of Dongba manuscripts. The other ones are used as phonetic loans, which account for 82.2% of all the components in this message. ). Despite the divergence in their Chinese surnames, indeed, that is one of the four traditional Naxi clans.

). Despite the divergence in their Chinese surnames, indeed, that is one of the four traditional Naxi clans. /

/ /nɖwɑ˧/ “pond”,

/nɖwɑ˧/ “pond”,  /hwæ˩/ “stream (cl.)”,

/hwæ˩/ “stream (cl.)”,  /ʈʰwʌ˧/ “drop”,

/ʈʰwʌ˧/ “drop”,  /ʐwʌ˧/, along with one word with nasalized rhymes,

/ʐwʌ˧/, along with one word with nasalized rhymes,  /hĩ˧/ “people”. The numbers after the glyphs indicate that the same glyphs were used repeatedly. The variants of the glyphs are shown in the table for completeness of information.

/hĩ˧/ “people”. The numbers after the glyphs indicate that the same glyphs were used repeatedly. The variants of the glyphs are shown in the table for completeness of information.

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,

,

,  (2)

(2)

,

,

,

,

(2)

(2)

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,

(2)

(2)

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

(2)

(2)

,

,

,

,

,

,

(2)

(2)

,

,

,

,

,

,