Abstract

This paper examines multiple sluicing constructions in Mandarin Chinese (henceforth, MC) experimentally. The acceptability status of such constructions in MC is controversial, and the judgments reported in the previous literature vary. Obtaining experimental evidence on the acceptability status is, therefore, important to advance the research on multiple sluicing in MC. Consequently, the present study conducts two sets of experiments to investigate factors affecting the acceptability of multiple sluicing sentences and the influence of the distribution of shi preceding wh-remnants on acceptability ratings. The results show that multiple sluicing in MC is generally a marked construction. Nevertheless, factors including prepositionhood and specificity have ameliorating effects on the acceptability of such constructions. Moreover, the influence of the distribution of shi on the acceptability ratings is related to the nature of wh-remnants; that is, its presence significantly improves the acceptability of cases of multiple sluicing when it precedes bare wh-arguments. We argue that the observed ameliorating effects on multiple sluicing can be explained by a cue-based retrieval approach to cross-linguistic elliptical constructions. Compared to bare wh-arguments, prepositional and discourse-linked wh-phrases provide cues to facilitate the retrieval of information from antecedent clauses.

1. Introduction

Coined by Ross (1969), sluicing is the ellipsis process by which questions like (1a) are converted into reduced forms like (1b).

| (1) | a. | He is writing something, but you can’t imagine [what he is writing]. |

| b. | He is writing something, but you can’t imagine [what]. | |

| (Ross 1969, p. 252) | ||

| c. | He is writing something, but you can’t imagine [CP whati [TP he is writing ti]] |

The embedded clause in (1a), indicated by the brackets, contains a wh-question, which is reduced to only contain a wh-phrase in (1b). The full-fledged wh-question and the reduced wh-question have the same interpretation (e.g., Ross 1969; Lasnik 2001; Merchant 2001). The remaining wh-phrase in (1b), namely, what, is called a wh-remnant, which has a corresponding counterpart in the preceding clause, i.e., something, called a correlate. As discussed in the previous literature (e.g., Ross 1969; Merchant 2001), the sluicing sentence in (1b) is derived by moving the wh-phrase what into the specifier position of CP, which is followed by TP-ellipsis, indicated with grey shading, as illustrated in (1c).

The type of sluicing configuration containing one wh-remnant, as in (1b), is called single sluicing. Sluicing, however, also allows multiple remnants, a configuration known as multiple sluicing (Takahashi 1994). An example is shown in (2).1

| (2) | ? | Everybody brought something (different) to the potluck, but I couldn’t tell you who what. |

| (Merchant 2001, p. 112) |

(2) has two wh-remnants, who and what. In this paper, we focus on multiple sluicing in Mandarin Chinese (hereafter, MC). Consider the example below:2

| (3) | Mouren | tou-le | tade | yi | yang | dongxi, | wo | xiang | zhidao | *(shi) |

| someone | steal-pfv | his | one | clf | thing | I | want | know | shi | |

| shei | *(shi) | shenme. | ||||||||

| who | shi | what | ||||||||

| ‘lit. Someone stole one of his belongings, and I wonder who what.’ | ||||||||||

| (Adams and Tomioka 2012, p. 237) | ||||||||||

The first clause in (3) functions as the antecedent for the sluiced clause containing two bare wh-arguments, shei ‘who’ and shenme ‘what,’ both accompanied by shi, a copula in MC.

It is worth noting the particular usage of the term multiple sluicing we are following in this paper. Sluicing and multiple sluicing generally refer to the ellipsis process of movement of wh-remnants followed by ellipsis of TP, as illustrated in (1c) in English. In some languages like MC, the theoretical analysis of truncated indirect questions like (3) has been under debate. In MC, three approaches have been discussed in the previous literature: the movement-and-deletion analysis (e.g., Chiu 2007; Bai and Takahashi 2023), the pseudo-sluicing analysis (e.g., Adams and Tomioka 2012), and the combined analysis of the former two analyses (e.g., Wang and Han 2018). The detailed derivational process of truncated questions in MC is not the concern of the present paper. Therefore, multiple sluicing in this paper is used as a cover term referring to the phenomenon of reduced indirect questions in MC without committing to a specific syntactic derivation. Yet, in Section 4.2, we show that our experimental results do not seem to favor the pseudo-sluicing analysis.

Multiple sluicing in MC has been studied for over a decade, but its acceptability status is still debated (Chiu 2007; Adams and Tomioka 2012; Takahashi and Lin 2012; Park and Li 2013; Wang 2018; Wang and Han 2018; Bai and Takahashi 2023). Some linguists (Chiu 2007; Wang 2018) consider cases like (3) unacceptable, while others (Adams and Tomioka 2012; Park and Li 2013; Wang and Han 2018) make the opposite judgment. In addition, the reported judgments in the previous literature are elicited based on informal data collection. Experimental evidence on the acceptability of multiple sluicing under formal experimental settings is, therefore, essential for the in-depth investigation of this phenomenon in MC.

The purpose of this paper is twofold. It aims first to support the cue-retrieval analysis, which accounts for cross-linguistic multiple sluicing constructions (Cortés Rodríguez 2023), by adding another language, namely MC, into the dataset. The other purpose of the present study is to present experimental evidence to further the discussion on multiple sluicing in MC, particularly regarding the distribution of shi. In this paper, we report the results of two experiments. The first experiment was modeled after the cross-linguistic experiments on multiple sluicing conducted by Cortés Rodríguez (2023). The second was designed to examine the effect of the distribution of shi on the acceptability of multiple sluicing.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents debates on multiple sluicing in MC. Additionally, factors influencing the acceptability of multiple sluicing constructions cross-linguistically, such as prepositionhood and specificity, are reviewed. Section 3 details two acceptability judgment studies on multiple sluicing in MC. The first one investigates the influence of prepositionhood and specificity on the acceptability of such constructions. The second one examines how the distribution of shi affects acceptability ratings. Section 4 discusses the experimental results. Finally, Section 5 concludes this paper.

2. Background

2.1. The Debates on Multiple Sluicing in Mandarin Chinese

This section details the debates on multiple sluicing in MC. Let us start by describing single sluicing in the language. Consider examples (4) and (5):

| (4) | Zhangsan | kan-dao | mouren, | danshi | wo | bu | zhidao | *(shi) | shei. |

| Zhangsan | see-pfv | someone | but | I | not | know | shi | who | |

| ‘Zhangsan saw somebody, but I don’t know who.’ | |||||||||

| (Wei 2004, p. 165) | |||||||||

| (5) | Zhangsan | mai-le | mouwu, | danshi | wo | bu | zhidao | *(shi) | shenme. |

| Zhangsan | buy-pfv | something | but | I | not | know | shi | what | |

| ‘Zhangsan bought something, but I don’t know what.’ | |||||||||

| (ibid.) | |||||||||

The wh-remnants in the sluiced clauses in (4) and (5) are simplex/bare wh-arguments shei ‘who’ and shenme ‘what,’ respectively, which must be accompanied by shi, as discussed in the previous literature (Wang 2002; Adams 2004; Wei 2004; Wang and Wu 2006; Chiu et al. 2008; Park and Li 2013; Li and Wei 2014; 2017; Song 2016; Sun 2018; Zhang and Overfelt 2019; Lee 2020).

The status of shi in sluicing in MC has received much debate. While some linguists (Wang 2002; Wang and Wu 2006; Qin and Xu 2019) regard it as a kind of focus marker, others (Adams 2004; Adams and Tomioka 2012; Li and Wei 2017) claim that it is a copula. Both claims are reasonable given that shi in the language can function as a focus marker and as a copula, as shown in (6) and (7), respectively.

| (6) | Shi | wo | mingtian | cheng | huoche | qu | Guangzhou. |

| foc | I | tomorrow | ride | train | go | Guangzhou | |

| ‘It is I who will go to Guangzhou by train tomorrow.’ | |||||||

| (Xu 2003, p. 4) | |||||||

| (7) | Ta | shi | yi | ge | xuesheng. | ||

| he | cop | one | clf | student | |||

| ‘He is a student.’ | |||||||

| (ibid.) | |||||||

The claim that shi is a focus marker in reduced questions is used to support the movement-and-deletion analysis (e.g., Wang and Wu 2006). On the other hand, the claim that shi is a copula in reduced questions is employed to support the pseudo-sluicing analysis. Since we do not discuss the derivational process of truncated questions in MC, the specific status of shi is not the main concern of this paper. We will only discuss the usage and distribution of shi in reduced questions in Section 4.

In addition to bare wh-arguments, sluicing in MC allows specific wh-arguments, as illustrated in (8).

| (8) | Lisi | bu | xihuan | yi | shou | ge, | danshi | wo | bu | zhidao | (shi) |

| Lisi | not | like | one | clf | song | but | I | not | know | shi | |

| na | yi | shou | ge. | ||||||||

| which | one | clf | song | ||||||||

| ‘Lisi doesn’t like one song, but I don’t know which song.’ | |||||||||||

| (Adams and Tomioka 2012, p. 223) | |||||||||||

In the sluiced clause, the specific wh-argument nayishou ge ‘which song’ can be optionally accompanied by shi (Adams 2004; Wei 2004; Adams and Tomioka 2012; Park and Li 2013; Li and Wei 2014; 2017; Song 2016; Sun 2018; Zhang and Overfelt 2019).

Sluicing in MC also allows adjunct and prepositional wh-remnants, as in (9) and (10), respectively.

| (9) | Zhangsan | zai | mou | ge | difang | chu | shi | le, | danshi | wo | bu | |

| Zhangsan | at | some | clf | place | have | accident | prf | but | I | not | ||

| zhidao | (shi) | zai | nali. | |||||||||

| know | shi | at | where | |||||||||

| ‘Zhangsan had an accident at some place, but I don’t know where.’ | ||||||||||||

| (Wei 2004, p. 168) | ||||||||||||

| (10) | Zhangsan | gang | gen | mouren | likai-le, | danshi | wo | bu | zhidao | (shi) | gen/han | shei. |

| Zhangsan | just | prep | someone | leave-pfv | but | I | not | know | shi | prep | who | |

| ‘Zhangsan just left with someone, but I don’t know with whom.’ | ||||||||||||

| (ibid.) | ||||||||||||

As discussed in the literature, the occurrence of shi is optional in front of adjunct and prepositional wh-remnants (Adams 2004; Wei 2004; Wang and Wu 2006; Park and Li 2013; Song 2016; Zhang and Overfelt 2019; Lee 2020). Moreover, Adams (2004) mentions that these single sluicing sentences are more natural when shi appears with wh-remnants. Thus far, we can see that the presence of shi is obligatory with bare wh-arguments but optional with specific wh-arguments, wh-adjuncts, and prepositional wh-remnants.3

In addition to single sluicing, multiple sluicing is found in MC. Let us start our discussion with wh-arguments. Chiu (2007) states that cases of multiple sluicing with two wh-arguments are unacceptable, as illustrated in (11).

| (11) | * | Mouren | da-le | women | ban | de | ren, | dan | wo | bu | zhidao | *(shi) | shei | shei. |

| someone | hit-pfv | our | class | gen | person | but | I | not | know | shi | who | who | ||

| ‘Someone hit a person of our class, but I don’t know who whom.’ | ||||||||||||||

| (Chiu 2007, p. 23) | ||||||||||||||

As discussed in Adams and Tomioka (2012) and Wang and Han (2018), cases like (11) are indeed unacceptable. The unacceptability may be caused by the presence of two identical wh-remnants whose correlates in the first clause cannot be identified. The wh-remnants may not, therefore, be able to be properly interpreted. Similar cases of multiple sluicing in English are also judged unacceptable (e.g., Bolinger 1978; Richards 2010), as shown in (12).

| (12) | * | I know that in each instance one of the girls chose one of the boys. But which which? |

| (Bolinger 1978, p. 109) |

Identical wh-remnants are claimed to cause a homonymic conflict, which renders the relevant multiple sluicing sentences unacceptable (Bolinger 1978).

Adams and Tomioka (2012), on the other hand, observe that multiple sluicing with two different wh-arguments is allowed, as shown above in (3) and repeated below as (13).

| (13) | Mouren | tou-le | tade | yi | yang | dongxi, | wo | xiang | zhidao | *(shi) |

| someone | steal-pfv | his | one | clf | thing | I | want | know | shi | |

| shei | *(shi) | shenme. | ||||||||

| who | shi | what | ||||||||

| ‘lit. Someone stole one of his belongings, and I wonder who what.’ | ||||||||||

| (Adams and Tomioka 2012, p. 237) | ||||||||||

In (13), the two wh-arguments are shei ‘who’ and shenme ‘what’. Park and Li (2013) and Wang and Han (2018) agree with Adams and Tomioka (2012) that cases like (13) are acceptable. Wang (2018), on the other hand, rejects such cases. See the example (14) below provided by Wang (2018).

| (14) | * | Lisi | zhi | jide | you | ren | mai-le | dongxi, | dan | ta | wang-le | shi |

| Lisi | only | remember | have | person | buy-pfv | thing | but | he | forget-pfv | shi | ||

| shenme | (shi) | shei. | ||||||||||

| what | shi | who | ||||||||||

| ‘Lisi only remembered someone bought something, but he forgot what who.’ | ||||||||||||

| (Wang 2018, p. 1) | ||||||||||||

Although we agree with the judgment provided for (14), we suspect that rather than by the combination of two bare wh-arguments, the reported unacceptability is caused by the following two factors. First, the order of the wh-arguments in (14) should be reversed because multiple sluicing is reported to adhere to the superiority effect, according to which the order of wh-remnants should conform to that of their correlates (e.g., Merchant 2001; Adams and Tomioka 2012; Kotek and Barros 2018). Moreover, the second shi preceding the bare wh-argument, shenme ‘what,’ must be obligatory, based on discussions in the previous literature (Adams and Tomioka 2012; Park and Li 2013; Wang and Han 2018), as well as on the results of our exploratory test.4 The obligatory presence of shi in front of each bare wh-argument is not surprising since shi is also obligatory in front of bare wh-arguments in single sluicing in MC.

Multiple sluicing with two specific wh-arguments is allowed, as discussed in Wang and Han (2018). Consider the example in (15). Note that neither of the specific wh-arguments is preceded by shi.

| (15) | Mouren | mai-le | yi | yang | dongxi, | danshi | wo | bu | zhidao | na | ge | ren |

| someone | buy-pfv | one | clf | thing | but | I | not | know | which | clf | person | |

| na | yang | dongxi. | ||||||||||

| which | clf | thing | ||||||||||

| ‘lit. Someone bought something, but I don’t know which person which thing.’ | ||||||||||||

| (Wang and Han 2018, p. 611) | ||||||||||||

Moreover, cases of multiple sluicing with a wh-argument and a wh-adjunct are also allowed (Chiu 2007; Adams and Tomioka 2012). Consider the examples below:

| (16) | Mouren | da-le | women | ban | de | ren, | dan | wo | bu | zhidao | *(shi) | shei | zai |

| someone | hit-pfv | our | class | gen | person | but | I | not | know | shi | who | at | |

| nali. | |||||||||||||

| where | |||||||||||||

| ‘lit. Someone hit a person of our class, but I don’t know who where.’ | |||||||||||||

| (Chiu 2007, p. 23) | |||||||||||||

| (17) | Laoshi | chufa-le | mouren, | wo | xiang | zhidao | *(shi) | shei |

| teacher | punish-pfv | someone | I | want | know | shi | who | |

| (shi) | wei | shenme. | ||||||

| shi | for | what | ||||||

| ‘lit. Teacher punished someone, and I wonder who why.’ | ||||||||

| (Adams and Tomioka 2012, p. 237) | ||||||||

Adams and Tomioka (2012) and Park and Li (2013) mention that the occurrence of shi preceding wh-adjuncts is optional, which is also the case for single sluicing in MC.5 Moreover, according to Adams and Tomioka (2012), (17) is more natural if shi accompanies each wh-remnant.

Likewise, Wang and Han (2018) discuss multiple sluicing with a specific wh-argument and a wh-adjunct, as illustrated in (18).

| (18) | Mouren | zai | mou | ge | difang | mai-le | yi | jian | chenyi, | danshi | wo |

| someone | at | some | clf | place | buy-pfv | one | clf | shirt | but | I | |

| bu | zhidao | na | ge | ren | zai | nali. | |||||

| not | know | which | clf | person | at | where | |||||

| ‘lit. Someone bought a shirt at a certain place, but I don’t know which person where.’ | |||||||||||

| (Wang and Han 2018, p. 611) | |||||||||||

It is worth mentioning that neither of the wh-remnants in (18) is preceded by shi. Additionally, Adams and Tomioka (2012) provide examples with a complex wh-argument and a wh-adjunct, as in (19).

| (19) | Zhangsan | zai | moushi | qu | mai-le | yi | yang | ta | hen | xihuan | de |

| Zhangsan | at | sometime | go | buy-pfv | one | clf | he | very | like | gen | |

| dongxi, | danshi | wo | bu | zhidao | (shi) | zai | heshi | *(shi) | shenme | dongxi. | |

| thing | but | I | not | know | shi | at | when | shi | what | thing | |

| ‘lit. Zhangsan went to buy something he really liked at some time, but I don’t know when what thing.’ | |||||||||||

| (Adams and Tomioka 2012, p. 239) | |||||||||||

Here we can see that the authors regard the presence of shi as optional with the wh-adjunct but obligatory with the complex wh-argument.

In this section, we have reviewed the debates on multiple sluicing in MC involving different combinations of wh-remnants.6 First, varied judgments on the acceptability of multiple sluicing, such as cases involving two bare wh-arguments, have been reported. Next, research on cases with two specific wh-arguments has been shown to be lacking. Furthermore, the reported judgments in the previous literature were elicited based on informal data collection. Lastly, we have reiterated reports from the previous literature where various distributions of shi depending on the nature of wh-phrases have been presented. Thus far, no studies have provided a comprehensive discussion on the influence of the different distributions of shi on the acceptability of multiple sluicing sentences.

2.2. Aspects Affecting the Acceptability of Multiple Sluicing Cross-Linguistically

2.2.1. The Presence of a Preposition

Multiple sluicing in English has also been studied in the previous literature (Takahashi 1994; Nishigauchi 1998; Merchant 2001, 2006; Fox and Pesetsky 2003; Richards 2010; Hoyt and Teodorescu 2012; Takahashi and Lin 2012; Lasnik 2014; Barros and Frank 2016, 2022; Abels and Dayal 2017, 2022; Kotek and Barros 2018; Cortés Rodríguez 2022, 2023). As in MC, the acceptability of multiple sluicing sentences in English is also under debate. Some linguists mention that cases with two wh-arguments are degraded or unacceptable, as shown in (20). On the other hand, cases with a wh-argument and a prepositional wh-remnant are more acceptable (Fox and Pesetsky 2003; Richards 2010; Lasnik 2014), as in (21).

| (20) | ?* | Someone saw something, but I can’t remember who what. |

| (Lasnik 2014, p. 8) | ||

| (21) | ? | Someone talked about something, but I can’t remember who about what. |

| (ibid.) |

Note that the correlates of the wh-remnants in (20)–(21) are existential quantifiers, namely, someone and something. The previous literature also discusses cases where the first correlate is a universal quantifier and the second correlate is an existential quantifier (Bolinger 1978; Nishigauchi 1998; Merchant 2001, 2006; Richards 2010). Consider the following examples:

| (22) | * | I know every man insulted a woman, but I don’t know which man which woman. |

| (Richards 2010, p. 3) | ||

| (23) | I know every man danced with a woman, but I don’t know which man with which woman. | |

| (ibid.) |

Richards (2010) observes that while the multiple-sluicing sentence in (22) with two wh-arguments is not acceptable, the sentence in (23) with a wh-argument and a prepositional wh-remnant is acceptable. Nevertheless, some linguists (e.g., Bolinger 1978; Nishigauchi 1998; Merchant 2001, 2006; Barros and Frank 2016; Kotek and Barros 2018) mention that cases of multiple sluicing with two wh-arguments are acceptable or only mildly deviant when the first correlate is a universal quantifier, as shown in examples (2) and (24).

| (24) | ? | Everyone bought something, but I couldn’t tell you who what. |

| (Merchant 2006, p. 284) |

So far, we have briefly reviewed the varied judgments on multiple sluicing in English. Since the judgments reported in the previous literature are elicited through informal tests, Cortés Rodríguez (2023) initiates formal experimental studies to examine the acceptability of such constructions and the factors that could influence their acceptability. One of the tested factors is the presence of a prepositional wh-remnant as the second remnant in multiple sluicing. See the test items from Cortés Rodríguez (2023) in (25)–(26).

| (25) | Everyone completed something, but I just don’t know who what. |

| (26) | Everyone commented on something, but I just don’t know who on what. |

| (Cortés Rodríguez 2023, p. 7) |

The multiple-sluiced clause in (25) has two wh-arguments, and that in (26) has a wh-argument and a prepositional wh-remnant. Cortés Rodríguez (2023) conducts three experiments whose results demonstrate that cases with a wh-argument and a prepositional wh-remnant such as (26) are significantly more acceptable than those with two wh-arguments such as (25). The author concludes that the presence of a preposition is an ameliorating factor in improving the acceptability of multiple sluicing in English, which confirms the observations made in the previous literature (Richards 2010; Lasnik 2014).

This ameliorating effect is explained following a cue-based retrieval approach to ellipsis (e.g., Martin and McElree 2008, 2011; Nykiel et al. 2023). Understanding a sentence requires retrieving information from working memory. During the retrieving process, the syntactic and semantic information that enables direct access to relevant memory representations is called cues (McElree et al. 2003; Lewis et al. 2006). As discussed in the previous literature (Lewis and Vasishth 2005; Harris 2015, 2019; Cortés Rodríguez 2023), morphosyntactic and lexical features, such as morphological case, gender, plurality, nominal restrictors, and prepositions, constitute cues for the retrieval of information. In this respect, cues serve to identify a previously stored linguistic item and to disambiguate it from other interfering items. Information retrieval is carried out via matching stored items with retrieval cues (Van Dyke and Lewis 2003). The cue-base retrieval modal has been applied to explain many sentence constructions like relative clauses and elliptical constructions, such as sluicing and multiple sluicing constructions. Elliptical constructions are generally preceded by linguistic antecedents. Cues facilitate the information retrieval from antecedents and, as a result, facilitate the processing of elliptical constructions (e.g., Martin and McElree 2008, 2011; Nykiel et al. 2023). As discussed in Cortés Rodríguez (2023), prepositions function as a cue for identifying the argument-structural status/thematic role of a sluiced wh-phrase within the inferred proposition, i.e., whether the wh-phrase is understood as associated with a subject, or a direct or indirect object (or also other phrases associated with the verbal event of the inferred proposition). Prepositions facilitate the retrieval of information presented in antecedent clauses and the identification of the correlate–remnant relation. Two nominal wh-arguments, on the other hand, increase the difficulty of discerning which correlate a wh-remnant refers to and, as such, impose a processing burden because of containing fewer cues. Consequently, factors that facilitate processing lead to higher acceptability ratings.

2.2.2. Specificity

As discussed in Section 2.2.1, some cases of multiple sluicing in English are reported to be degraded, as in (20), repeated below as (27). Lasnik (2014) mentions that such cases become less degraded when the second remnant becomes “heavier”, as illustrated in (28).

| (27) | ?* | Someone saw something, but I can’t remember who what. |

| (Lasnik 2014, p. 8) | ||

| (28) | ? | Some linguist criticized (yesterday) some paper about sluicing, but I don’t know which linguist which paper about sluicing. |

| (ibid.) |

In (28), the second remnant which paper about sluicing, containing which plus a complex NP restrictor paper about sluicing, is heavier than the bare wh-argument what in (27). According to Lasnik (2014), cases like (28) with heavy remnants are less degraded than cases like (27).

Since Lasnik (2014) is the only study that mentions the influence of the weight of wh-remnants on the acceptability ratings of multiple sluicing in English, Cortés Rodríguez (2023) conducts three experiments to examine whether the weight of the second wh-remnant influences the acceptability of such constructions. See (29) for a test item from Cortés Rodríguez (2023).

| (29) | a. | Everyone completed something, but I just don’t know who what. |

| b. | Everyone completed some essay, but I just don’t know who which essay. | |

| c. | Everyone completed some essay about colonialism, but I just don’t know who which essay about colonialism. | |

| (Cortés Rodríguez 2023, p. 7) |

In Cortés Rodríguez (2023), three levels of weight were examined: bare wh-arguments in (29a), specific wh-arguments in (29b), and heavy wh-arguments in (29c). The overall experimental results showed no significant difference in acceptability between the levels bare and specific. However, there was a detrimental effect between bare/explicit and heavy: the acceptability ratings got lower as the second remnants got heavier. Cortés Rodríguez (2023) argues that heavy remnants include repeated information from antecedent clauses, which causes the lowering in acceptability ratings. Similar observations have been made for single sluicing; that is, the more repeated material, the lower the acceptability rating (Gordon et al. 1993; Sag and Nykiel 2011).

On the other hand, Bhattacharya and Simpson (2012) mention that some cases of sluicing in Hindi with specific wh-arguments are judged more acceptable than those with bare wh-arguments. They argue that this difference can be attributed to the nature of wh-remnants. Specific wh-arguments provide unambiguous clues for establishing the correlate–remnant matching relation. Bare wh-arguments, on the other hand, cause parsing difficulties. Furthermore, Harris (2015) conducts eye-tracking studies on single sluicing in English, and the results support the cue-based parsing model of sentence processing. Concretely, discourse-linked wh-phrases containing which and nominal restrictors, such as which wines, provide richer cues than wh-phrases such as which ones with fewer cues. The former cases are proven to be able to facilitate the correlate–remnant pairing in sluicing and the accurate retrieval of information from antecedent clauses (see Harris 2015 for details; see also Harris 2019).

Based on the discussions in this section, we can see that there are discrepancies in the literature with respect to the effects of specificity in multiple sluicing configurations. For this reason, we were motivated to examine whether specificity is an ameliorating factor in multiple sluicing in MC.

2.2.3. The Cue-Based Retrieval Approach to Ellipsis

The cue-based retrieval approach to ellipsis (Martin and McElree 2008, 2011; Harris 2015, 2019; Nykiel et al. 2023) is supported by the experimental results in Cortés Rodríguez (2023). Despite multiple sluicing in English being a marked construction whose acceptability rating is in the 4 range on a 7-point Likert scale (as per the results in Cortés Rodríguez 2023), there are ameliorating effects contributed by some factors such as prepositionhood (i.e., the presence of a preposition accompanying the non-initial wh-remnant). Furthermore, Cortés Rodríguez (2023) provides additional evidence to support the cue-based analysis by conducting experiments on multiple sluicing in Spanish and German (Cortés Rodríguez 2021, 2023). In Spanish, a language with poor case morphology, the prediction for multiple sluicing is similar to that in English: The preposition effect should be observed since the cues provided by prepositions can facilitate the correlate–remnant pairing when no morphological case can provide cues. The experiment results in Cortés Rodríguez (2021) show that this prediction is indeed borne out. Moreover, similar to English, multiple sluicing in Spanish is also a marked construction. On the other hand, in German, a language with rich case morphology, multiple sluicing is predicted to be more acceptable than in English and Spanish. In addition, since case morphology provides sufficient cues for processing, the preposition effect is predicted not to be observed in German. These predictions are also borne out (see Cortés Rodríguez 2023).

Cues provided by syntactic and semantic features are proven to facilitate the processing of cross-linguistic elliptical constructions, though the strength of the cues in helping information retrieval may vary depending on language-specific properties. Inspired by prior research, we examine whether the cue-retrieval analysis can be supported by multiple sluicing in another language, namely, MC, following the experimental design of Cortés Rodríguez (2023). Specifically, we aim to investigate whether cues provided by prepositions and specific wh-arguments are effective in helping the processing of multiple sluicing in MC.

3. Experiments on Multiple Sluicing in Mandarin Chinese

This section presents two sets of experiments on multiple sluicing in MC. The first one investigates the influence of the presence of prepositions and specific wh-remnants on the acceptability of multiple sluicing. The second one contains a series of sub-experiments examining the different distributions of shi.

3.1. Experiment 1: Prepositionhood and Specificity

3.1.1. Methods

Design and Materials

We conducted an acceptability judgment experiment to examine the influence of the factors prepositionhood and specificity on the acceptability of multiple sluicing in MC, following the experimental design of Cortés Rodríguez (2023). Twenty-four sentence quadruplets were created containing multiple sluicing using a 2 × 2 within-subject design. The two independent variables were (i) prepositionhood, representing the levels +P (presence of a preposition) and -P (absence of a preposition), and (ii) specificity, including the factor levels bare (wh-pronoun) and specific (which NP).

Each experimental sentence consists of three parts: antecedent, intro, and sluice. The antecedent encompasses a universal quantifier and an existential quantifier. Each of the initial correlates is an animate entity, and each of the second correlates is an inanimate entity. Second, the intro part is the governing expression, wo zhishi bu zhidao ‘I just don’t know,’ which selects an embedded clausal question. Lastly, the sluice part presents two adjacent wh-phrases in an elliptical context. Each test sentence displays harmony between the correlate and its corresponding sluiced wh-remnant. Here, harmony refers to equal weighting in each correlate–remnant pair. For instance, when the correlate is a complex phrase such as some student, the remnant is also a complex phrase such as which student. The test sentences were constructed in this manner to avoid the possible detrimental effect of disharmony on acceptability judgments (see Dayal and Schwarzschild 2010; Nykiel 2013). Furthermore, congruence is obtained between the two wh-remnants in each test item, meaning that the second remnant is in accordance with the first remnant with respect to specificity. Concretely, when the first remnant is a bare wh-phrase, the second remnant is also a bare wh-phrase (e.g., who what), and when the first remnant is a specific wh-phrase, the second remnant is also a specific wh-phrase (e.g., which student which project). Congruence is a factor examined in Cortés Rodríguez (2023), which is shown to affect acceptability, i.e., the acceptability is lower when there is incongruence between the two remnants.

Before presenting test items in the experiment, we note one important point with respect to the items. As reported in Section 2.1, multiple sluicing in MC shows various distributions of shi depending on the nature of the wh-phrases. Including all the distributions is beyond the scope of this experiment. To eliminate the influence of shi on experimental results, we used the most acceptable distribution (to our knowledge) in each condition. Section 3.2 will present an experiment series on the different distributions of shi, whose results demonstrate that the distribution of shi employed here is justified. Thus, the results obtained for Experiment 1 are not influenced by shi, and the obtained results are the product of the experimental manipulations.

Next, the items in each condition are explained. In the -P/bare condition, we used multiple sluicing sentences with shi preceding each wh-argument because the presence of shi is obligatory with each bare wh-argument (Adams and Tomioka 2012; Park and Li 2013; Wang and Han 2018), as shown in (30). In the -P/specific condition, we employed multiple sluicing sentences with shi preceding only the first wh-argument because cases with such distribution were more acceptable than those with shi preceding each specific wh-argument, according to the results of our exploratory tests.7 See (31) below for an illustration.

| (30) | Condition 1: -P/bare | |||||||||

| Mei | ge | ren | dou | wancheng-le | moushi, | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | |

| every | clf | person | all | complete-pfv | something | I | just | not | know | |

| shi | shei | shi | shenme. | |||||||

| shi | who | shi | what. | |||||||

| ‘Everyone completed something, I just don’t know who what.’ | ||||||||||

| (31) | Condition 2: -P/specific | |||||||||

| Mei | ge | daxuesheng | dou | wancheng-le | yi | ge | xiangmu, | wo | ||

| every | clf | college.student | all | complete-pfv | one | clf | project | I | ||

| zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | na | ge | daxuesheng | na | ge | xiangmu. | |

| just | not | know | shi | which | clf | college.student | which | clf | project | |

| ‘Every college student completed a project, I just don’t know which college student which project.’ | ||||||||||

Moving on to the items containing a preposition, namely, +P conditions, we must recall that in MC, prepositional phrases usually precede verbs (Li and Thompson 1981; Yuan 2010; Ross and Ma 2014; Liu et al. 2019), as shown in the examples below.8

| (32) | Lao | changzhang | zhengzai | gei | linzi | li | de | shu | jiaoshui. |

| old | farm.leader | now | prep | woods | inside | gen | tree | water | |

| ‘The farm leader is watering the trees in the woods.’ | |||||||||

| (Liu et al. 2019, p. 290) | |||||||||

| (33) | Nin | buyao | wei | wo | danxin. |

| you | don’t | prep | me | worry | |

| ‘Please don’t worry about me.’ | |||||

| (ibid.) | |||||

In the +P/bare and +P/specific conditions, we used multiple-sluicing sentences where the first remnant, i.e., a wh-argument, was preceded by shi and the second remnant, i.e., a prepositional wh-remnant, was not. This implementation was based on the following considerations. First, shi is optional in front of prepositional wh-remnants (Wei 2004; Wang and Wu 2006; Park and Li 2013; Song 2016; Zhang and Overfelt 2019; Lee 2020). Second, our informal consultation with native speakers for sentences such as (34) and (35) revealed that shi with a prepositional wh-remnant was redundant, resulting in lower acceptability ratings.

| (34) | Condition 3: +P/bare | |||||||||

| Mei | ge | ren | dou | gei | mouwu | qi-guo-ming, | wo | zhishi | bu | |

| every | clf | person | all | prep | something | name-pfv | I | just | not | |

| zhidao | shi | shei | gei | shenme. | ||||||

| know | shi | who | prep | what | ||||||

| ‘Everyone named something, I just don’t know who what.’ | ||||||||||

| (35) | Condition 4: +P/specific | |||||||||||

| Mei | ge | nvhai | dou | gei | mou | ge | wanju | qi-guo-ming, | ||||

| every | clf | girl | all | prep | some | clf | toy | name-pfv | ||||

| wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | na | ge | nvhai | gei | na | ge | wangju. | |

| I | just | not | know | shi | which | clf | girl | prep | which | clf | toy | |

| ‘Every girl named some toy, I just don’t know which girl which toy.’ | ||||||||||||

In short, in the -P/specific, +P/bare, and +P/specific conditions, only the first wh-remnant was preceded by shi. In the -P/bare condition, on the other hand, both wh-remnants were accompanied by shi. This implementation of the distributions of shi in the test items was decided based on the previous literature, informal exploratory tests, and consultation with native speakers to eliminate or lessen the influence of shi on the experimental results. We return to discussions on the distributions of shi in Experiment 2, presented in Section 3.2.

The distribution of test items followed a Latin square design, where four lists were created, and all items and fillers were randomized within each trial. Every participant saw a total of six items in each condition, thus 24 critical items in total. Additionally, 72 fillers were included in every list. Fifteen of those fillers served as control filler items, which included five degrees of acceptability from most natural to least natural. Each degree featured three sentences.9 The purpose of including control fillers was to check whether participants used the rating scale correctly. Another 15 fillers were multiple wh-questions containing wh-arguments, wh-adjuncts, and prepositional wh-phrases. The remaining 42 fillers included various sentence constructions cited from the Modern Chinese Corpus compiled by the Center for Chinese Linguistics of Peking University (CCL Corpus) (Zhan et al. 2003). Accordingly, each participant rated a total of 96 experimental tokens.

Participants and Procedure

An acceptability judgment test was created using PsychoPy 3 software (Peirce et al. 2019). Forty self-reported native speakers of MC (mean age = 25.5, SD = 1.89) studying at Tohoku University (Japan) were recruited via different social media channels. The task was deployed in lab, and thus participation occurred in person. Participants were instructed to read carefully and to rate the naturalness of sentences on a 7-point scale, from 1 (very unnatural) to 7 (very natural), based on their intuition. Additionally, they were informed that there were no “right” or “wrong” answers and that they should just follow their intuition. Each participant received a JPY 1000 Amazon gift card as compensation for their participation in this study, which lasted approximately 20 min. Based on the judgments participants gave to the control filler items, four participants were excluded for misusing the rating scale. Consequently, the data of 36 participants entered the statistical analysis. Lastly, a practice round with five sentences was conducted before participants began the critical trial. They were allowed to ask clarification questions about the procedure during this practice trial.

Predictions

For this experiment, we made the following predictions:

| (36) | Prediction regarding prepositionhood |

| Multiple sluicing in which the second remnant is a prepositional wh-remnant should be rated significantly more acceptable than that in which the second remnant is a wh-argument. | |

| (37) | Prediction regarding specificity |

| Multiple sluicing in which the remnants are specific wh-phrases should be rated significantly more acceptable than that in which the remnants are bare wh-phrases. |

The prediction in (36) is motivated by the cue-based retrieval approach to ellipsis and experimental results and discussions on multiple sluicing in English and Spanish (Cortés Rodríguez 2021, 2023). Like English and Spanish, MC lacks case morphology (Barrie and Li 2015), and multiple sluicing in this language should, therefore, rely on cues provided by prepositions so that the thematic roles can be properly discerned. Furthermore, constructions including a preposition consist of one more cue than those without a preposition. Consequently, the former cases are predicted to be more acceptable than the latter cases. Next, the prediction in (37) is motivated by the cue-based retrieval approach and the discussions in Bhattacharya and Simpson (2012) (see also Harris 2015, 2019). In MC, specific wh-arguments, such as nage daxuesheng ‘which college student’ and nage xiangmu ‘which project’ in (31), provide a set of cues for identifying the correlate–remnant pairing relation efficiently. By comparison, bare wh-arguments, such as shei ‘who’ and shenme ‘what’ in (30), lack the information provided by nominal restrictors, which are considered as cues in the previous literature. Without case morphology, the information provided by nominal restrictors should facilitate the processing of multiple-sluicing sentences, resulting in higher acceptability ratings.

3.1.2. Data Analysis and Results

The data were analyzed in statistics software R, Version 4.1.2 (R Core Team 2021). We employed an ordinal logistic regression, and in particular, we used the clmm function of the ordinal package (Christensen 2019). To find the model with the best fit, we implemented a manual backward model section process using the anova function. We started checking the full model, namely the one including all experimental factors and interactions as fixed effects, as well as random effects for both items and subjects with their maximal random slopes and respective interactions.10 Then the model was progressively checked against a minimally simplified model until the model with the most complex random effect structure that would converge was reached (Barr et al. 2013). Here, we report the model with the best maximal fixed and random effect structure supported by the experimental data. The corresponding formula is provided in the tables with the statistical analysis.

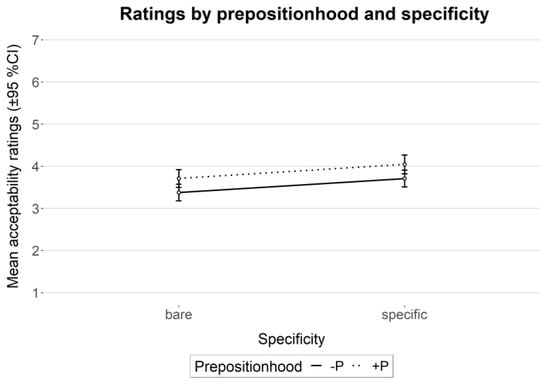

Figure 1 shows the mean acceptability ratings obtained for the four experimental conditions; the results of its statistical analysis are presented in Table 1. Additionally, Table 2 provides the means and standard deviation of the individual conditions. The model yielded two main effects for prepositionhood and specificity. Concerning prepositionhood, multiple sluicing sentences where a preposition was present in the non-initial wh-remnant were rated as significantly more acceptable. As for the main effect observed for specificity, participants rated specific conditions as significantly more acceptable than bare ones. The direction of those two main effects and the lack of individual difference between Conditions 2 and 3 are indicative of an additive effect. There was no significant interaction between the factors. Finally, the overall mean ratings for multiple sluicing in MC were in the 3.7 range on a 7-point Likert, as shown in Figure 1. This result indicates that multiple sluicing is a marked construction in MC, just like that in English and Spanish (Cortés Rodríguez 2021, 2023).

Figure 1.

Mean acceptability ratings (n = 36). Error bars show 95% confidence interval.

Table 1.

Cumulative Link Mixed Model fitted with the Laplace approximation.

Formula: rating ~ prepositionhood + specificity + (prepositionhood | subject) + (1 | item). item). The significance levels used in across all experiments reported here are the following: p < 0.05 = *; p < 0.01 = **; p < 0.001 = ***.

Table 2.

Mean acceptability ratings in Experiment 1.

Table 2.

Mean acceptability ratings in Experiment 1.

| Condition | Rating (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | bare wh | -P bare wh | 3.36 (1.46) |

| 2 | specific wh | -P specific wh | 3.69 (1.47) |

| 3 | bare wh | +P bare wh | 3.70 (1.56) |

| 4 | specific wh | +P specific wh | 4.00 (1.65) |

The predictions made for this experiment are borne out. We will further discuss the results in Section 4.1.11 In particular, we will discuss how the cue-retrieval approach suggested for parallel studies in English and German (Cortés Rodríguez 2023) can capture the differences observed here.

3.2. Experiment 2: The Distribution of shi

We conducted a series of experiments to examine the distribution of shi in multiple sluicing in MC, motivated by the following two points. On the one hand, since the previous literature reports varied distributions of shi in multiple sluicing, we were motivated to define the distributions based on the results of controlled experimentation. On the other hand, given that our implementation of the distribution of shi in Experiment 1 was determined based on a small set of informally collected judgments (besides our own intuition), we sought to confirm that our implementation could be supported by formal experimentation.

3.2.1. Methods

Design and Materials

We conducted four sub-experiments in this series, all of which followed a 2 × 2 within-item and within-subject design. The two independent variables were (i) shi-wh1, representing the presence or absence of shi accompanying the first wh-remnant, thus the factor levels were simply yes (shi is present) and no (shi is not present), and (ii) shi-wh2, likewise modulating the presence or absence of shi in the second wh-remnants. The test conditions are illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3.

The distribution of shi in each test condition.

The four tested conditions in Experiment 1, i.e., -P/bare, -P/specific, +P/bare, and +P/specific, were separately tested in sub-experiments 1–4, respectively. Each of the sub-experiments tested all the possible distributions of shi, as presented in Table 3. Moreover, the sentence structure used across all experimental items in the four sub-experiments mirrored the same pattern introduced for Experiment 1. See (38)–(43) for example test items in each sub-experiment.

In sub-experiment 1, the distributions of shi in the -P/bare condition were tested, as shown in the example test item (38). In sub-experiment 2, the distributions of shi in the -P/specific condition were tested, as in (39). Sub-experiments 1 and 2 each included 24 critical items in four conditions.

| (38) | Sub-experiment 1 [nominal bare—nominal bare] | ||||||||

| Mei | ge | ren | dou | wancheng-le | moushi, | ||||

| every | clf | person | all | complete-pfv | something | ||||

| ‘Everyone completed something,’ | |||||||||

| C1. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | shei | shi | shenme. | |

| I | just | not | know | shi | who | shi | what | ||

| C2. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | shei | shenme. | ||

| I | just | not | know | shi | who | what | |||

| C3. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shei | shi | shenme. | ||

| I | just | not | know | who | shi | what | |||

| C4. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shei | shenme. | |||

| I | just | not | know | who | what | ||||

| ‘I just don’t know who what.’ | |||||||||

| (39) | Sub-experiment 2 [nominal specific—nominal specific] | |||||||||||

| Mei | ge | daxuesheng | dou | wancheng-le | yi | ge | xiangmu, | |||||

| every | clf | college.student | all | complete-pfv | one | clf | project | |||||

| ‘Every college student completed a project,’ | ||||||||||||

| C1. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | na | ge | daxuesheng | shi | na | ge | xiangmu. |

| I | just | not | know | shi | which | clf | college.student | shi | which | clf | project | |

| C2. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | na | ge | daxuesheng | na | ge | xiangmu. | |

| I | just | not | know | shi | which | clf | college.student | which | clf | project |

| C3. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | na | ge | daxuesheng | shi | na | ge | xiangmu. |

| I | just | not | know | which | clf | college.student | shi | which | clf | project | |

| C4. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | na | ge | daxuesheng | na | ge | xiangmu. | |

| I | just | not | know | which | clf | college.student | which | clf | project | ||

| ‘I just don’t know which college student which project.’ | |||||||||||

In sub-experiment 3, we tested the distributions of shi in the +P/bare condition, as exemplified in (40). Additionally, this sub-experiment tested the distributions of shi in cases where the second correlate was an adjunct, as in (41). We decided to include cases with adjuncts for the following reasons. First, although cases with adjuncts have been discussed in the previous literature, they have not been experimentally tested. Second, the adjuncts used in multiple sluicing in MC all have an underlying prepositional structure. For instance, the wh-adjunct in (41) zai heshi ‘at when’ includes the preposition zai. Accordingly, sub-experiment 3 had 32 critical items: 16 including a PP argument and another 16 including an adjunct. Similarly, sub-experiment 4 also contained 32 item quadruplets: 16 including a PP argument in the +P/specific condition and another 16 including a specific adjunct as the second wh-remnant, as exemplified in (42) and (43), respectively. The sub-experiments containing adjuncts are referred to as sub-experiments 3’ and 4’, respectively, both including an equal number of locative and temporal adjuncts (i.e., 8 locative and 8 temporal).

| (40) | Sub-experiment 3 [nominal bare—prepositional bare] | |||||||||

| Mei | ge | ren | dou | gei | mouwu | qi-guo-ming, | ||||

| every | clf | person | all | prep | something | name-pfv | ||||

| ‘Everyone named something,’ | ||||||||||

| C1. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | shei | shi | gei | shenme. | |

| I | just | not | know | shi | who | shi | prep | what | ||

| C2. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | shei | gei | shenme. | ||

| I | just | not | know | shi | who | prep | what | |||

| C3. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shei | shi | gei | shenme. | ||

| I | just | not | know | who | shi | prep | what | |||

| C4. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shei | gei | shenme. | |||

| I | just | not | know | who | prep | what | ||||

| ‘I just don’t know who what.’ | ||||||||||

| (41) | Sub-experiment 3’ [nominal bare—bare adjunct] | |||||||||

| Mei | ge | ren | dou | zai | moushi | qu-guo | Beijing, | |||

| every | clf | person | all | at | sometime | go-pfv | Beijing | |||

| ‘Everyone went to Beijing at sometime,’ | ||||||||||

| C1. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | shei | shi | zai | heshi. | |

| I | just | not | know | shi | who | shi | at | when | ||

| C2. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | shei | zai | heshi. | ||

| I | just | not | know | shi | who | at | when | |||

| C3. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shei | shi | zai | heshi. | ||

| I | just | not | know | who | shi | at | when | |||

| C4. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shei | zai | heshi. | |||

| I | just | not | know | who | at | when | ||||

| ‘I just don’t know who when.’ | ||||||||||

| (42) | Sub-experiment 4 [nominal specific—prepositional specific] | ||||||||

| Mei | ge | nvhai | dou | gei | mou | ge | wanju | qi-guo-ming, | |

| every | clf | girl | all | prep | some | clf | toy | name-pfv | |

| ‘Every girl named some toy,’ | |||||||||

| C1. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | na | ge | nvhai | shi | gei | na | ge | wangju. |

| I | just | not | know | shi | which | clf | girl | shi | prep | which | clf | toy | |

| C2. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | na | ge | nvhai | gei | na | ge | wangju. | |

| I | just | not | know | shi | which | clf | girl | prep | which | clf | toy | ||

| C3. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | na | ge | nvhai | shi | gei | na | ge | wangju. | |

| I | just | not | know | which | clf | girl | shi | prep | which | clf | toy | ||

| C4. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | na | ge | nvhai | gei | na | ge | wanju. | ||

| I | just | not | know | which | clf | girl | prep | which | clf | toy | |||

| ‘I just don’t know which girl which toy.’ | |||||||||||||

| (43) | Sub-experiment 4’ [nominal specific—specific adjunct] | |||||||||

| Mei | ge | xuesheng | dou | zai | mou | ge | shijian | qu-guo | Beijing, | |

| every | clf | student | all | at | some | clf | time | go-pfv | Beijing | |

| ‘Every student went to Beijing at some time,’ | ||||||||||

| C1. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | na | ge | xuesheng | shi | zai | shenme | shijian. |

| I | just | not | know | shi | which | clf | student | shi | at | what | time | |

| C2. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | shi | na | ge | xuesheng | zai | shenme | shijian. | |

| I | just | not | know | shi | which | clf | student | at | what | time | ||

| C3. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | na | ge | xuesheng | shi | zai | shenme | shijian. | |

| I | just | not | know | which | clf | student | shi | at | what | time | ||

| C4. | wo | zhishi | bu | zhidao | na | ge | xuesheng | zai | shenme | shijian. | ||

| I | just | not | know | which | clf | student | at | what | time | |||

| ‘I just don’t know which student at what time.’ | ||||||||||||

The distribution of test items followed a Latin square design, where four lists were created for each sub-experiment, and all items and fillers were randomized within each trial. In sub-experiments 1 and 2, every participant saw a total of six items in each condition, thus a total of 24 critical items. In sub-experiments 3 and 4, every participant saw a total of four items in each condition of prepositions and adjuncts, thus a total of 32 critical items. Additionally, 72 fillers were included in every list, resulting in a final amount of 96 experimental tokens that each participant rated in sub-experiments 1 and 2 and a final amount of 104 experimental tokens that each participant rated in sub-experiments 3 and 4.

Participants and Procedure

We conducted four web-based acceptability judgment experiments. As in Experiment 1, we used PsychoPy 3 as the experiment creation software. For online participation, we hosted the experiments in Pavlovia.12 Using WeChat, the following number of participants were recruited: 32 for sub-experiment 1, 31 for sub-experiment 2, 30 for sub-experiment 3, and 33 for sub-experiment 4. Participants were self-reported adult native speakers of Mandarin Chinese. They were not informed of the purpose of the experiment; their instructions were only to rate the naturalness of the presented sentences on a 7-point scale from 1 (very unnatural) to 7 (very natural) based on their intuition. They were also informed that there was no “right” or “wrong” answer. Each participant received CNY 30 as cash remuneration for their participation in the study, which lasted approximately 20 min. Based on the judgments the participants gave to a set of control fillers, which were the same control fillers as in Experiment 1, the following number of participants were excluded from the analysis for misusing the scale: 5 from sub-experiment 1, 3 from sub-experiment 2, 5 from sub-experiment 3, and 8 from sub-experiment 4. Consequently, the data from 105 participants (27 from sub-experiment 1; 28 from sub-experiment 2; 25 from sub-experiment 3; 25 from sub-experiment 4) were included in the analysis. Lastly, a practice round with five sentences was conducted before participants began the critical trial. During this practice trial, they were allowed to ask clarification questions about the procedure.

Predictions Regarding the Distribution of shi

In this experiment, we made the following predictions:

| (44) | a. | The presence or absence of shi should significantly influence the acceptability of multiple sluicing sentences with bare wh-arguments. |

| b. | The presence or absence of shi should not significantly influence the acceptability of multiple sluicing sentences with specific wh-arguments, prepositional wh-arguments, or wh-adjuncts. |

Since the influence of the different distributions of shi on the acceptability of multiple sluicing in MC has not been comprehensively discussed in the previous literature, the predictions in (44) are motivated by the reported usage of shi in single sluicing in the language, as reviewed in Section 2.1.

3.2.2. Data Analysis and Results

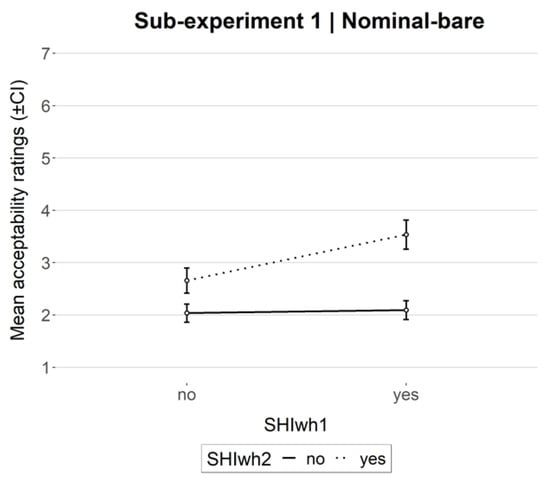

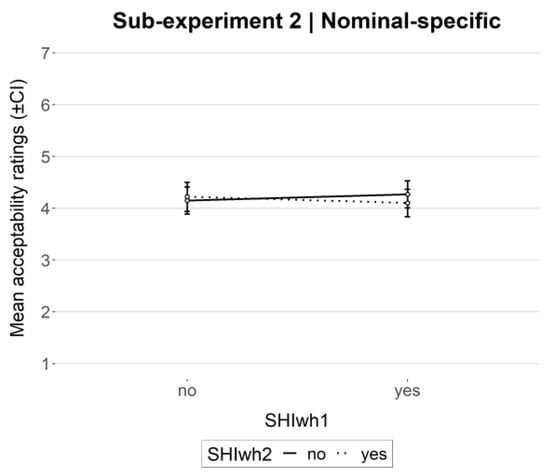

The data of the four sub-experiments were analyzed using the same procedures as in Experiment 1. First, we present the descriptive statistics for sub-experiments 1 and 2. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the mean acceptability ratings (±95% CI) obtained for the four experimental conditions, and the results of its statistical analysis are presented in Table 4 and Table 5, respectively. Additionally, Table 6 and Table 7 provide the means and standard deviation of the individual conditions.

Figure 2.

Mean acceptability ratings (n = 27). Error bars show 95% confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Mean acceptability rating (n = 28). Error bars show 95% confidence interval.

On the one hand, the model for the data in sub-experiment 1 yielded a main effect for shi-wh2, as well as an interaction. No significant effect was observed for shi-wh1. Concerning shi-wh2, the results showed that multiple sluicing configurations where a shi was present in the non-initial wh-remnant produced significantly more acceptable sentences. Given the significant interaction, a post hoc Tukey test was performed to check for individual comparison between each level. Crucially, the only comparison levels that did not show a significant difference were the conditions where the non-initial wh-remnant was not accompanied by shi.

On the other hand, the results for sub-experiment 2 did not show any significant effect.

Table 4.

Cumulative link mixed model fitted with the Laplace approximation. (Sub-experiment 1 | Nominal-bare.)

Table 4.

Cumulative link mixed model fitted with the Laplace approximation. (Sub-experiment 1 | Nominal-bare.)

| Estimate | Std. Error | z Value | Pr (>|z|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| shi-wh1 (yes) | 0.1664 | 0.2810 | 0.592 | 0.553793 | |

| shi-wh2 (yes) | 1.0798 | 0.2966 | 3.641 | 0.000272 | *** |

| shi-wh1: shi-wh2 | 1.3254 | 0.3103 | 4.271 | 1.94 × 10−5 | *** |

Formula: rating ~ SHIwh1*SHIwh2 + (SHIwh1+SHIwh2 | subject) + (1 | item).

Table 5.

Cumulative link mixed model fitted with the Laplace approximation. (Sub-experiment 2 | Nominal-specific.)

Table 5.

Cumulative link mixed model fitted with the Laplace approximation. (Sub-experiment 2 | Nominal-specific.)

| Estimate | Std. Error | z Value | Pr (>|z|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| shi-wh1 (yes) | 0.05954 | 0.22163 | 0.269 | 0.788 |

| shi-wh2 (yes) | −0.18676 | 0.22988 | −0.812 | 0.417 |

Formula: rating ~ SHIwh1+SHIwh2 + (SHIwh1*SHIwh2 | subject) + (1 | item)

Table 6.

Mean acceptability ratings in sub-experiment 1.

Table 6.

Mean acceptability ratings in sub-experiment 1.

| Condition | Rating (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | shi bare wh | shi bare wh | 3.54 (1.78) |

| 2 | shi bare wh | bare wh | 2.09 (1.16) |

| 3 | bare wh | shi bare wh | 2.66 (1.55) |

| 4 | bare wh | bare wh | 2.04 (1.12) |

Table 7.

Mean acceptability ratings in sub-experiment 2.

Table 7.

Mean acceptability ratings in sub-experiment 2.

| Condition | Rating (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | shi specific wh | shi specific wh | 4.10 (1.74) |

| 2 | shi specific wh | specific wh | 4.27 (1.72) |

| 3 | specific wh | shi specific wh | 4.22 (1.85) |

| 4 | specific wh | specific wh | 4.15 (1.70) |

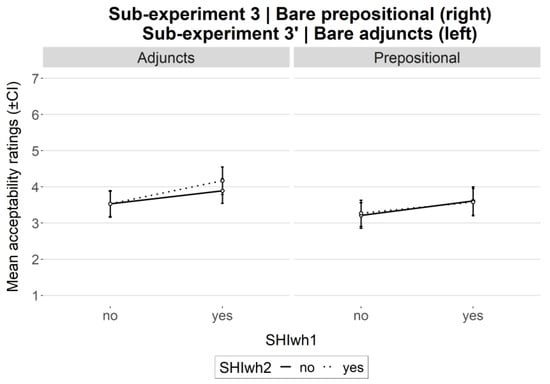

Second, Figure 4 illustrates the mean acceptability ratings (±95% CI) obtained for sub-experiments 3 and 3’. Two separate models were calculated for the items containing a prepositional phrase as the non-initial wh-remnant and for the items where the non-initial wh-remnant was an adjunct (a locative or temporal adverb, to be precise). Table 8 and Table 9 demonstrate the statistical analysis for sub-experiments 3 and 3’, respectively. Furthermore, the means and standard deviation of the individual conditions are presented in Table 10 and Table 11.

Figure 4.

Mean acceptability ratings (n = 25). Error bars show 95% confidence interval.

In both cases, the results showed a main effect shi-wh1; that is, significantly higher acceptability ratings were obtained for conditions where the initial wh-phrase, i.e., a bare wh-argument, was preceded by shi.

Table 8.

Cumulative link mixed model fitted with the Laplace approximation. (Sub-experiment 3 | Bare-Prepositional.)

Table 8.

Cumulative link mixed model fitted with the Laplace approximation. (Sub-experiment 3 | Bare-Prepositional.)

| Estimate | Std. Error | z Value | Pr (>|z|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| shi-wh1(yes) | 0.4840 | 0.2379 | 2.034 | 0.042 | * |

Formula: rating ~ SHIwh1 + (SHIwh1 | subject) + (1 | item)

Table 9.

Cumulative link mixed model fitted with the Laplace approximation. (Sub-experiment 3’ | Bare-Adjunct.)

Table 9.

Cumulative link mixed model fitted with the Laplace approximation. (Sub-experiment 3’ | Bare-Adjunct.)

| Estimate | Std. Error | z Value | Pr (>|z|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| shi-wh1(yes) | 0.6939 | 0.2766 | 2.509 | 0.0121 | * |

Formula: rating ~ SHIwh1 + (SHIwh1 | subject) + (1 | item)

Table 10.

Mean acceptability ratings in sub-experiment 3.

Table 10.

Mean acceptability ratings in sub-experiment 3.

| Condition | Rating (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | shi bare wh | shi bare prepositional wh | 3.73 (1.91) |

| 2 | shi bare wh | bare prepositional wh | 3.66 (1.98) |

| 3 | bare wh | shi bare prepositional wh | 3.37 (1.82) |

| 4 | bare wh | bare prepositional wh | 3.32 (1.76) |

Table 11.

Mean acceptability ratings in sub-experiment 3’.

Table 11.

Mean acceptability ratings in sub-experiment 3’.

| Condition | Rating (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | shi bare wh | shi bare adjunct wh | 4.26 (1.87) |

| 2 | shi bare wh | bare adjunct wh | 3.94 (1.73) |

| 3 | bare wh | shi bare adjunct wh | 3.75 (1.73) |

| 4 | bare wh | bare adjunct wh | 3.67 (1.82) |

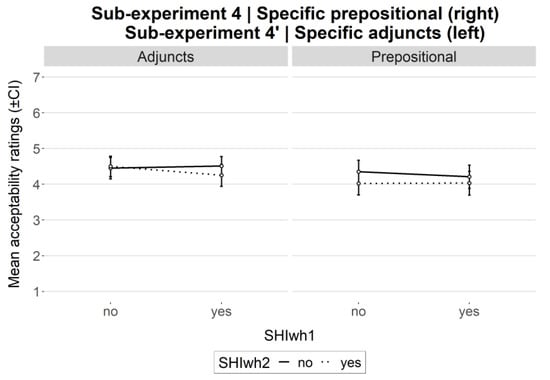

Third, the mean acceptability ratings obtained for sub-experiments 4 and 4’ are presented in Figure 5. The statistical analysis for the model containing specific prepositional phrases is given in Table 12; the means and standard deviation of the individual conditions are provided in Table 13. The results for the model including specific adjunct phrases are provided in Table 14; the means and standard deviation are presented in Table 15. Similar to the results obtained in sub-experiment 2, none of the factors reached significance in sub-experiments 4 and 4’.

Figure 5.

Mean acceptability ratings (n = 25). Error bars show 95% confidence interval.

Table 12.

Cumulative link mixed model fitted with the Laplace approximation. (Sub-experiment 4 | Specific-Prepositional.)

Formula: rating ~ SHIwh1 + (SHIwh1 | subject) + (1 | item)

Table 13.

Mean acceptability ratings in sub-experiment 4.

Table 13.

Mean acceptability ratings in sub-experiment 4.

| Condition | Rating (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | shi specific wh | shi specific prepositional wh | 4.03 (1.67) |

| 2 | shi specific wh | specific prepositional wh | 4.21 (1.64) |

| 3 | specific wh | shi specific prepositional wh | 4.02 (1.61) |

| 4 | specific wh | specific prepositional wh | 4.35 (1.62) |

Table 14.

Cumulative link mixed model fitted with the Laplace approximation. (Sub-experiment 4’ | Specific-Adjunct.)

Table 14.

Cumulative link mixed model fitted with the Laplace approximation. (Sub-experiment 4’ | Specific-Adjunct.)

| Estimate | Std. Error | z Value | Pr (>|z|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| shi-wh1 (yes) | −0.1568 | 0.2284 | −0.687 | 0.492 |

Formula: rating ~ SHIwh2 + (SHIwh1+ SHIwh2 | subject) + (1 | item)

Table 15.

Mean acceptability ratings in sub-experiment 4’.

Table 15.

Mean acceptability ratings in sub-experiment 4’.

| Condition | Rating (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | shi specific wh | shi adjunct specific wh | 4.25 (1.55) |

| 2 | shi specific wh | adjunct specific wh | 4.51 (1.35) |

| 3 | specific wh | shi adjunct specific wh | 4.50 (1.43) |

| 4 | specific wh | adjunct specific wh | 4.45 (1.51) |

We will further discuss the results of this series of experiments in Section 4.2.

4. General Discussion

4.1. On Experiment 1

As presented in Section 3.1, the results of Experiment 1 show that prepositionhood and specificity improve the acceptability of multiple sluicing in MC, which aligns with the cue-retrieval approach to ellipsis. First, the presence of a prepositional wh-remnant as the second remnant makes multiple sluicing sentences more acceptable, which can be attributed to the cues provided by prepositions in discerning argument structures. Prepositions in MC facilitate the processing of multiple sluicing sentences, resulting in higher acceptability ratings, which is in accordance with the observations made in Cortés Rodríguez (2021, 2023) for multiple sluicing in English and Spanish. These three languages all lack case morphology, making cues contributed by prepositions necessary in processing multiple sluicing constructions.

The experimental results also demonstrate that, in MC, multiple sluicing sentences with specific wh-arguments are significantly more acceptable than those with bare wh-arguments, which can be attributed to the additional cues supplied by specific wh-phrases. Specific wh-phrases composed of which and an NP restrictor are discourse linked, presupposing that there is a set of individuals and objects salient to discourse participants (Pesetsky 1987; Comorovski 1996). The experiment contains cases of multiple sluicing with a universal quantifier and an existential quantifier as correlates, which are more complex than multiple sluicing sentences with two existential quantifiers because the former forces pair-list interpretation, while the latter produces single-pair reading. Processing the former cases is difficult in formal experimental settings where no contexts are provided. Discourse-linked wh-phrases contribute to the association of multiple sluicing sentences with concrete contexts and discourse containing salient sets of individuals and objects, which can facilitate processing. For example, nage daxuesheng ‘which college student’ and nage xiangmu ‘which project’ in (31) presuppose that there is a set of college students and projects in the discourse. Moreover, nominal restrictors help the establishment of the correlate–remnant matching relation and the retrieval of information from antecedent clauses. On the other hand, bare wh-arguments cannot refer to any pre-established information in the discourse, thus increasing the difficulty in processing the relevant multiple sluicing sentences. For instance, shei ‘who’ and shenme ‘what’ in (30) refer to all humans and things.

Furthermore, although our experiment shows that specific wh-phrases improve the acceptability of multiple sluicing in MC, the specificity effect is not observed in English or Spanish (Cortés Rodríguez 2021, 2023). Since our experiment is modeled after Cortés Rodríguez (2021, 2023), we would like to make a preliminary assumption explaining this difference. We conjecture that cues function differently in different languages in accordance with language-specific properties. In a language with rich case morphology, cues provided by overt case marking are sufficient to facilitate the processing of elliptical constructions. For instance, in German, the overall mean ratings for multiple sluicing constructions are in the 5 range on a 7-point Likert scale, irrespective of the presence or absence of a preposition or a specific wh-argument (Cortés Rodríguez 2023). The fact that the preposition and specificity effects are not observed in German multiple sluicing indicates that cues provided by case markers are sufficient. On the other hand, in languages with poor case morphology such as English, Spanish, and MC, syntactic cues provided by a preposition are effective in facilitating the processing of multiple sluicing constructions, as discussed in Cortés Rodríguez (2021, 2023) and the present paper. Furthermore, discourse-related cues provided by discourse-linked wh-phrases work differently in different languages. In MC, a discourse-oriented language (Huang 1984; Shei 2019), discourse-related cues could play a significant role in ellipsis processing.13 English and Spanish, on the other hand, are sentence-oriented languages (Wakabayashi 2002), where discourse-related cues may not significantly affect the processing of multiple sluicing in the two languages.14

In summary, the results of our experiment on MC support the cue-retrieval analysis explaining the differences in acceptability ratings of cross-linguistic multiple sluicing constructions (Cortés Rodríguez 2021, 2023).

4.2. On Experiment 2

This section discusses the results of the series of sub-experiments we conducted in Section 3.2. In sub-experiment 1 with bare wh-arguments, the overall result was that the presence of shi affected acceptability ratings. First and foremost, condition 1 with shi preceding each bare wh-argument received the highest rating, supporting our implementation of the distribution of shi in Experiment 1. Moreover, in conditions 2–4, where one of the bare wh-arguments or neither were preceded by shi, the ratings were rather low, demonstrating that the relevant constructions were completely unacceptable.15 In accordance with the results from sub-experiment 1, we maintain that bare wh-arguments in multiple sluicing in MC require the support of shi, which is in line with the observations made in the previous literature.

In sub-experiment 2 with specific wh-arguments, the general result was that there were only minimal differences among the different distributions of shi. Nevertheless, as demonstrated in Table 7, the mean acceptability rating for condition 2 was the highest among the four conditions, supporting our implementation of the distribution of shi in Experiment 1. Interestingly, condition 1 with shi accompanying each specific wh-argument received the lowest rating, which was in direct contrast to the result from sub-experiment 1 with bare wh-arguments. Based on the results from sub-experiment 2, we claim that specific wh-arguments do not necessarily require the support of shi. Moreover, these results confirm the observations made for single sluicing in MC, namely, the occurrence of shi is optional in front of specific wh-arguments. The results from sub-experiments 1 and 2 further consolidate our conclusion from Experiment 1 that specificity is an ameliorating factor in multiple sluicing in MC, since the overall mean in sub-experiment 2 was higher than that in sub-experiment 1.

In sub-experiments 3 and 3’ including bare prepositional wh-arguments and bare wh-adjuncts, the results showed that acceptability ratings were significantly higher when the first remnant, i.e., the bare wh-argument, was preceded by shi. This result is not surprising because a bare wh-argument requires shi-support. Furthermore, the presence or absence of the second shi did not significantly affect the acceptability ratings, indicating that the distribution of shi we used in Experiment 1 was correct. Based on the results, we claim that the occurrence of shi is optional with prepositional wh-phrases and wh-adjuncts in multiple sluicing, which parallels the observations made for single sluicing in MC. Moreover, the results strengthen the argument that bare wh-arguments require the support of shi.

In sub-experiments 4 and 4’, which included specific prepositional wh-arguments and specific wh-adjuncts, the overall result showed that there were minimal differences among the different distributions of shi, just as in the results of sub-experiment 2 with specific wh-arguments. Thus, we claim that specific wh-remnants do not require the support of shi.

In general, the influence of the distributions of shi on the acceptability of multiple sluicing in MC is related to the nature of the wh-remnants; that is, the presence of shi in front of bare wh-arguments significantly improved acceptability ratings, whereas shi in front of specific wh-arguments, prepositional wh-phrases, and wh-adjuncts did not influence acceptability ratings significantly. In other words, only bare wh-arguments obligatorily require shi-support.16 With regard to the obligatory or optional presence of shi in front of wh-remnants in sluicing and multiple sluicing in MC, the previous literature has provided various explanations, all of which are related to different theoretical analyses of sluicing constructions, i.e., the pseudo-sluicing analysis and the wh-movement followed by TP-ellipsis analysis (see the referenced literature in Section 2.1 for details). It is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a definite answer to this line of inquiry. Nevertheless, the present study lays a solid empirical ground for further discussion.

Before concluding this paper, we would like to mention that the results of our experiments do not seem to favor the pseudo-sluicing analysis, which involves the conjunction of two copular clauses with null subjects, as discussed in Adams and Tomioka (2012). Consider (45) and (46):

| (45) | Mouren | tou-le | tade | yi | yang | dongxi, | wo | xiang | zhidao | [pro |

| someone | steal-pfv | his | one | clf | thing | I | want | know | he | |

| *(shi) | shei] | yiji | [pro | *(shi) | shenme] | |||||

| be | who | and | it | be | what | |||||

| ‘Someone stole one of his belongings, and I wonder who he was and what it was’ | ||||||||||

| (46) | Laoshi | chufa-le | mouren, | wo | xiang | zhidao | [pro | *(shi) | shei] |

| teacher | punish-pfv | someone | I | want | know | he | be | who | |

| yiji | [pro | (shi) | wei | shenme] | |||||

| and | that | be | for | what | |||||

| ‘Teacher punished someone, and I wonder who he was and why that was’ | |||||||||

Sentences in (45) and (46) illustrate the pseudo-sluicing analysis of example (3) with two wh-arguments and (17) with a wh-argument and a wh-adjunct, respectively. As predicted by the pseudo-sluicing analysis, the conjunction of two copular clauses is fully acceptable. That is, (45) and (46) are equally acceptable. Consequently, the pseudo-sluicing analysis can neither explain the degraded acceptability judgments nor capture the differences between wh-arguments and wh-adjuncts observed in our experiments. The detailed theoretical analysis of multiple sluicing in MC is left for future research.

5. Conclusions

Multiple sluicing constructions in MC have been investigated in terms of its general acceptability and distributions of shi. The previous literature has not conducted extensive examinations into either of these two aspects. Moreover, previous arguments were largely based on informal data collection. The current study advances the research on multiple sluicing in MC by initiating experimental studies, following Cortés Rodríguez (2021, 2023). The experiments presented in this paper show four important findings. First, similar to English and Spanish, multiple sluicing in MC was confirmed to be a marked construction with acceptability ratings in the 3.7 range on a 7-point Likert scale. Second, factors like the presence of prepositions and specific wh-remnants were found to improve the overall acceptability of these constructions. Third, the distribution of shi was shown to have an effect on the acceptability of multiple sluicing. The presence of shi preceding bare wh-arguments significantly improved acceptability ratings, while shi in front of specific wh-arguments, prepositional wh-remnants, and adjunct wh-remnants did not significantly influence acceptability ratings. Finally, the (non-)optionality of shi in multiple sluicing parallels that found in single sluicing in MC. Based on these findings, we argue that the ameliorating effects of prepositionhood and specificity can be explained by a cue-retrieval approach to ellipsis. Specific wh-phrases, adjuncts, and prepositions provide cues to help the retrieval of information from antecedent clauses. Bare wh-arguments, on the other hand, increase the processing burden because of a lack of cues. Our experimental findings are in line with the cross-linguistic experimental studies of Cortés Rodríguez (2021, 2023). Multiple sluicing constructions are marked in languages with poor case morphology, such as English, Spanish, and MC. On the other hand, in languages with rich case morphology, such as German (e.g., Merchant 2006; Richards 2010; Cortés Rodríguez 2023) and Japanese (Takahashi 1994), multiple sluicing constructions are more acceptable. We further argue that the need for shi-support depends on the nature of wh-phrases; that is, only bare wh-arguments obligatorily require support from shi. This paper contributes to the study on multiple sluicing in MC by providing experimental evidence, thereby laying a solid foundation for further theoretical analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.B., Á.C.R. and D.T.; methodology, X.B. and Á.C.R.; software, Á.C.R.; data collection, X.B.; data analysis, Á.C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, X.B. and Á.C.R.; writing—review and editing, X.B., Á.C.R. and D.T.; revision, X.B., Á.C.R., D.T.; funding acquisition, X.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding