Abstract

In this work, we will investigate hybridization, borrowing, and grammatical reorganization phenomena in the Arbëresh dialects of San Marzano (Apulia) and Vena di Maida (central Calabria). The data from the Arbëresh of S. Benedetto Ullano (northern Calabria) will be useful to provide a comparative frame. Arbëresh is the name of the Albanian varieties spoken in the villages/cities generally formed in the late fifteenth century by communities fleeing from Albania as a consequence of the Ottoman occupation. The long-time contact with neighboring Romance varieties is reflected in the extended mixing phenomena which characterize the lexicon and the morphosyntactic organization of Arbëresh as a heritage language. This is particularly evident in the two dialects that we investigate in this contribution, where relexification and grammatical reorganization phenomena provide us with an interesting testing ground to explain language variation.

1. Introduction

Arbëresh (Italo-Albanian)1 varieties have been spoken in several villages in Abruzzo, Molise, Campania, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria, and Sicily since the end of the fifteenth century (Savoia 2010, 2015a). Given the wide distribution and fragmentation of this minority, we find very different conditions of use and integrity between the different communities. Of course, the secular contact with neighboring Romance dialects and Italian has affected all communities. However, some varieties show stronger contact effects such as morphosyntactic reorganization processes and other types of mixing phenomena2. The contact phenomena include lexicon, as usual, phonology, and morphosyntax. We will dwell on two varieties, that of Vena di Maida, a village in central Calabria (Manzini and Savoia 2007; Savoia 2008), and the Arbëresh spoken in the South Apulian center of San Marzano (Savoia 1980; Belluscio and Genesin 2015); the latter has been isolated for centuries and is far from the other Italo-Albanian centers of North Apulia and Basilicata. In San Marzano, Arbëresh is still known and spoken by a part of the population and is characterized by some tendencies of certain crucial morphosyntactic patterns towards reduction caused by its coexistence in bilingual speakers with Salento dialects of the area. Its phonology has assumed the typical devoicing of voiced obstruents occurring in neighboring Romance dialects. The morphosyntax of the case and inflection of nouns and the prepositional constructs have been subject to reduction and reorganization processes. As to the variety of Vena, we find a complex situation of contact, which also created a specific Romance dialect used by speakers in alternation with local Arbëresh. Phonological and morphosyntactic overlaps emerge, giving rise to in-depth mixing phenomena3.

We will see that the mechanisms of variation in the last analysis are rooted in the fundamental structures of human language rather than being subject to the external pressure of cultural and communicative necessities, as maintained by current functionalist conceptions. We are obviously aware that the socio-cultural context and the communicative pertinence requirements can drive linguistic variation, selecting what is brought to the attention of the speakers and driving their communicative intentions. Contact, mixing, pidginization/creolization, and other mechanisms, such as ‘setting’ factors (Hymes 1974) and bilingual interaction, define the external conditions of variation. Nevertheless, we note that phenomena of language mixing and borrowing reflect constraints that form the faculty of language. For the sake of clarity, in the discussion that will follow, we adopt the interpretation of linguistic variation and change based on the theoretical framework that Chomsky characterizes as the Biolinguistic Program. More precisely, we assume that variation relies on and is restricted by the basic property of language, as defined by Chomsky (Hauser et al. 2002; Chomsky 2005, 2015, 2020). Referring to the framework defined by Chomsky (2005), the interaction between socio-linguistic and pragmatic factors and language can be traced back to the effect of experience, which modifies the input to which the speaker is exposed, and to the third factor, the cognitive principles limiting language acquisition or learning.

2. Descriptive and Theoretical Aspects of Contact

The preservation of an alloglot language for several centuries in a situation of contact with different morphosyntactic, phonological, and lexical systems involves code-switching and mixing processes and the production of mixed sentences and borrowings (Bakker and Muysken 1994). Needless to say, Arbëresh shows a wide range of lexical bases of Apulian or Calabrian origin, together with cases of syntactic hybridization. According to Thomason (2010), an intense contact situation can also induce changes in grammar components such as phonology, morphological paradigms, and syntax, altering the typological nature of the language. In these cases, convergence may also make the morphosyntactic patterns of the languages in contact more similar, as discussed in Matras (2010).

There is a conceptual link between interaction phenomena in multilingual competence and transfer (Verschik 2017). Code-switching and mixing, borrowing, and re-coding of semantic or morphosyntactic properties of a language stem from multilingual minds, as the effect of the intertwining of grammars in the competence of speakers. Contact morphosyntactic reorganization is induced by the transfer processes characterizing bi-/multilingual knowledge: in these communities, a certain number or majority of the speakers have been bilingual for many centuries, thus manifesting the usual outcomes of transfer and language mixing. In all cases, we expect that changing L2 during the acquisition process is not conceptually different from changing L2 during the acquisition process in social or cultural contact contexts (Foote 2009; Thomason 2001, 2010).

In keeping with Cook (2008, 2009), the L2 acquisition has access to basic properties of language, in part leveraging the parameterization fixed in L1, which, therefore, influences L2. However, L2 does not fail to influence L1 in turn, confirming the hypothesis that the speaker has a single overall system (Cook 2009; Thomason 2010). Its semantic-syntactic and phonological representations obey morphological and lexical restrictions, as well as syntactic order imposed by structural parameters and semantic cognitive principles (Baldi 2019, 2022). In other words, parameterization is the result of linguistic and cognitive restrictions mapping syntactic and phonological information onto representations available for interpretive sensory-motor and conceptual-intentional systems, regardless of whether L1 or L2 is the source. We must admit that the basic properties of computation (Chomsky 2015) are recoverable and available to the learner as a part of her/his internal language faculty not only in childhood but also in the subsequent process of language acquisition. Descriptive literature on mixing phenomena supports the conclusion that in mixed languages, the lexical bases of one language normally combine with the inflection system of the other (‘language intertwining’, Bakker and Muysken 1994). The relation between the language which supplies morphology and syntax and the language which supplies the lexical items refers to the distinction between ‘embedded language’ and ‘matrix language’ (Myers-Scotton 2003).

The properties of lexical and functional elements working in the influencing language, the source language, SL, and in the influenced language, the receiving language, RL (Thomason 2010), contribute to designing the syntax and the interpretation of sentences. In conclusion, with regard to the minds of multilingual people, we will identify Italo-Romance dialects as the source language, and the Arbëresh dialects as the receiving language, regardless of their original acquisitional status. In the present case studies, we can reasonably surmise that most of the speakers after the first generation grew up bilingual Arbëresh/Apulian or Calabrian and that their overall linguistic system was subject to a partial reorganization due to transfer from Lx, the Italo-Romance dialect, to Ly, the alloglot variety.

The main effects of contact between Arbëresh and the local Italian dialect include lexical borrowing, morphosyntactic convergence, and attrition phenomena (de Bot and Bülow 2021). As we shall see, borrowing is intertwined with the question of word-internal code-mixing, a point closely connected with attrition in speakers with declining lexical competence and diminishing grammatical capacity in L1 (Schmid 2011; Matras 2000).

Romance Relexification in Arbëresh

Let us first consider the relexification in the San Marzano and Vena dialects. In the literature, the tendency to prefer names is referred to the wider autonomy that nouns have in the discourse (Romaine 2000). On the contrary, verbs combine referentiality with predication, thus performing a complex task at the base of the sentence (Matras 2007). Another generalization concerns the fact that the loan process and the interference would preferably save the nuclear lexicon—nouns denoting body parts, numbers, personal pronouns, conjunctions, etc. (Romaine 2000; Muysken 2000). The acquisition of loanwords seems to reflect implicational generalizations, such as those in (1a) for categories and (1b) for lexical classes.

| (1) | a. | Lexical items | > derivational morphology > inflectional morphology > syntax |

| (Romaine 2000) | |||

| b. | Nouns > adjectives > verbs > prepositions | ||

| (Muysken 2000; Myers-Scotton 2006; partially Matras 2007). | |||

However, a prolonged bilingualism, as in the case of Arbëresh speakers, gave rise to an extensive relexification from Romance, in which, however, the preference for the nominal borrowings as opposed to the verbal ones does not appear. The borrowing of grammatical elements is in turn frequent, also including formatives such as inflections, which are generally immune from being borrowed.

The samples in (2a), (2b), (3a), and (3b) have only an illustrative role, presenting two small subsets of Romance borrowings in the San Marzano and Vena dialects, which include nouns in (a) and verbs in (b)4.

| (2) | a. | martjeʎ-i | ‘hammer-msg.Def’ |

| mandil-a | ‘apron-fsg.Def’ | ||

| vitr-i | ‘glass-msg.Def’ | ||

| fjerr-i | ‘iron-msg.Def’ | ||

| dəʃətunn-i | ‘thumb-msg.DFef’ | ||

| vaŋgarjeʎʎ-i | ‘chin- msg.Def’ | ||

| vaɲɲunn-i/vaɲɲunn-ja | ‘boy-msg.Def/-fsg.Def’ | ||

| kattiv-ɛ | ‘widow-pl.Def’ | ||

| tʃuttʃ-i | ‘donkey-msg.Def’ | ||

| rəndəneʎʎ-a | ‘swallow-fsgDef’ | ||

| krab-a | ‘goat-fsg.Def’ | ||

| vak-a | ‘cow-fsg.Def’ | ||

| b. | sart-ɔ-ɲ | ‘I jump’ | |

| jump-TV-1SG | |||

| tsap-ɔ-ɲ | ‘I hoe’ | ||

| hoe-TV-1SG | |||

| punt-ɔ-ɣ-əmə | ‘I button myself’ | ||

| button-TV-MP-1SG | |||

| pəndz-ɔ-ɲ | ‘I think’ | ||

| think-TV-1SG | |||

| mmaddʒin-ɔ-ɲ | ‘I imagine’ | ||

| imagine-TV-1SG | |||

| San Marzano |

| (3) | a. | haddal-ɛ | ‘apron-fsg’ |

| martɛʎ-i | ‘hammer-msg.Def’ | ||

| lɛndzol-i | ‘sheet-msg.Def’ | ||

| hɔrˈmikul-a | ‘ant-fsg.Def’ | ||

| buh-a | ‘toad-msg.DFef’ | ||

| aɲɛʎ-i | ‘lamb-msg.Def’ | ||

| kaprɛt-i | ‘kid- msg.Def’ | ||

| b. | pɛndz-a-ɲa | ‘I think’ | |

| think-TV-1SG | |||

| prɛɣ-a-ɲa | ‘I pray’ | ||

| pray-TV-1SG | |||

| sɛt-a-hɐ-mɐ | ‘I sit down’ | ||

| sit-TV-MP-1SG | |||

| hum-a-ɲa | ‘I smoke’ | ||

| smoke-TV-1SG | |||

| ripɛtts-a-ɲa | ‘I darn’ | ||

| darn-TV-1SG | |||

| kamin-a-ɲa | ‘I go away’ | ||

| go-TV-1SG | |||

| ntʃiɲ-a-ɲa | ‘I begin’ | ||

| begin-TV-1SG | |||

| krið-i-ɲa | ‘I believe’ | ||

| believe-TV-1SG | |||

| kapiʃ-i-ɲa | ‘I understand’ | ||

| understand-TV-1SG | |||

| lɛj-i-ɲa | ‘I read’ | ||

| read-TV-1SG | |||

| rispund-i-ɲa | ‘I answer’ | ||

| answer-TV-1SG | |||

| frij-i-ɲa | ‘I fry’ | ||

| fry-TV-1SG | |||

| ʃund-i-ɲa | ‘I untie’ | ||

| untie-TV-1SG | |||

| Vena |

Let us dwell on these data. As generally attested (MacSwan 2021), the loans incorporated in the Arbëresh system show the regular morphology, i.e., the gender, plural, case, and definiteness morphology in nouns and the tense and agreement morphology in verbs (Savoia 2008, 2010), as in (4) for nouns and in (5) for verbs. The properties of selection and subcategorization of verbs give rise to the syntactic organization of the sentence.

| (4) | a. | kammə | parə | vaɲɲunnə-ni | |||||

| have.1sg | seen | boy-Acc.Def | |||||||

| ‘I have seen the boy’ | |||||||||

| a’. | vaɲɲunn-i | kwa | siɟɟ-urə | ||||||

| boy-Def | have.MP | wake up-PP | |||||||

| ‘the boy woke up’ | |||||||||

| San Marzano | |||||||||

| b. | brɛst-a | stip-in | i | ri | |||||

| buy.Past-1sg | the.sideboard-Acc.Def | msg.Def | new | ||||||

| ‘I bought the new sideboard’ | |||||||||

| b.’ | hinɛʃtrə-tə | janə | tə | zbil-ur-a | |||||

| window-pl | be.3pl | pl | open-PP-pl | ||||||

| ‘the windows are open’ | |||||||||

| Vena | |||||||||

| (5) | a. | kammə | pənts-urə | ði-ðə | |||||

| have.1sg | think-PP | you-obl | |||||||

| ‘I have thought of you’ | |||||||||

| San Marzano | |||||||||

| b. | u | ntʃiɲ-a-v-a | t | ɛ | lɛj-iɲ | ||||

| I | begin-TV-past-1sg | Prt | it | read-1sg | |||||

| ‘I began to read it’ | |||||||||

| Vena | |||||||||

If we now come to the adjectival borrowings, we note that they are generally characterized by an inflection -u, in most varieties invariable, as in (6a) for San Marzano, or, possibly, inflected in the plural, where the ending –a is variably inserted, as illustrated in (6b) for Vena5. We can think that -u is nothing but the masculine singular inflection of the Romance nominal system, here generalized as the inflection of this subset of adjectives. Other solutions may emerge, as in the case of the form kontɛnti ‘content, glad’ for San Marzano and kontɛnt for Vena in (6c), where the exponent –i of the plural is generalized.

| (6) | a. | iʃt/jannə | jɛrt-u | ||

| (s)he is/they are | tall-Infl | ||||

| vaʃ-u | |||||

| short-Infl | |||||

| fridd-u | |||||

| cold-Infl | |||||

| ‘(s)he/it is/they are tall/short/cold’ | |||||

| ɲə gruɛ | vaʃʃ-u | ||||

| a woman | short-Infl | ||||

| ‘a short woman’ | |||||

| San Marzano | |||||

| b. | ɐʃt/jan | aut-u | (/aut-a) | ||

| (s)he is/they are | tall-Infl | /tall-pl | |||

| vaʃ-u | (/vaʃ-a) | ||||

| short-Infl | /short-pl | ||||

| kruð-u | (/kruð-a) | ||||

| raw-Infl | /raw-pl | ||||

| ‘(s)he/it is/they are tall/short/raw’ | |||||

| Vena | |||||

| c. | iʃt | kuntɛnt-i | |||

| is | content-Infl | ||||

| ‘(s)he is content’ | |||||

| San Marzano | |||||

| ɐʃt | kuntɛnt | ||||

| is | content | ||||

| ‘(s)he is content’ | |||||

| Vena | |||||

Moreover, these adjectives lack the pre-posed article, the linker6, regularly occurring in DP and in copular sentences with native adjectives (Turano 2002; Savoia 2008; Manzini and Savoia 2018), as in (7a,b,c,d). We will indicate the linker with its agreement features, pl, sg, m, f, Def.

| (7) | a. | diaʎ-i | i | maθ | |||

| boy-msg.def | msg | big | |||||

| ‘the big boy’ | |||||||

| b. | ɐʃt | ɛ | mað-ɛ | ||||

| is | fsg | big-fsg | |||||

| ‘she is big’ | |||||||

| Vena | |||||||

| c. | iʃt | ɛ | ssaðə | ||||

| is | fsg | thin | |||||

| ‘she is thin’ | |||||||

| d. | iʃt | i | mirə | ||||

| is | msg | good | |||||

| ‘he is good’ | |||||||

| San Marzano | |||||||

If the lexical elements fix the morphosyntactic content relevant to the C-I system in a language, borrowability (Matras 2007) should depend on this capability. The literature on language acquisition has highlighted that the word–world relation favors the words that refer to concrete things or events, perceptible and identifiable in the experience stream (Gleitman et al. 2005). We can wonder whether this basic level of conceptual organization causes a stronger resistance in the corresponding subpart of the vocabulary in each of the known languages by the speakers or whether it favors hybridization and borrowing. A purely observational answer is that perceptible and identifiable things or events favor borrowing, as shown by the loan words in (2) and (3) and generally by the data available on these varieties. In other words, this cognitive restriction seems to work in the second language learning, favoring the words connected to the concrete and current cultural experience. Other types of splits observed in the literature on language disorders and acquisition concern the different cognitive status of nouns and verbs (Luzzati and Chierchia 2002; Caramazza 1997). Caramazza and Shelton (1998) bear experimental evidence supporting the hypothesis that the animate/inanimate distinction is basic in the organization of the conceptual space. These authors relate this categorial split to an evolutionary pressure that has fixed a specialized cognitive tool.

The animate/inanimate category would include the sensorial distinction that separates meanings on the basis of the perceptive (visual) or functional nature of their definitory properties. Other categories discussed in Luzzatti et al. (2002) with regard to noun–verb dissociation phenomena are the imageability of a referent and the frequency of the words in the denomination tasks. Matras (2007) takes into consideration the semantic properties of the event such as the sensitivity to the number of arguments, the contrast between transitive and intransitive verbs, and modal properties. The research on linguistic disorders suggests that primitives such as imageability, animacy, argument structure, and frequency are in turn relevant in influencing naming capacity. The authors highlight that such categories belong to the cognitive system that organizes our lexical knowledge, thus also affecting acquisition processes that create mixed or secondary languages.

The distribution shown by the loanwords in the Arbëresh lexicon in (2)–(3) bears witness to different degrees of access to the borrowing and code-mixing, whereby the majority of the loanwords denote artifacts or animals. These terms involve properties such as imageability and use frequency, implying socio-cultural and pragmatic factors. As for verbal borrowings, perceptibility seems to be a relevant component. Nevertheless, the verbs for ‘think’ are generally borrowed, suggesting a crucial role in the discourse. Adjectival borrowings include both individual-level properties denoting spatial properties, such as aut-u, and stage-level properties, such as kundɛnd/kuntɛnti. The distribution of adjectives over spatial and dimensional attributes and inherent but perceptible properties recalls the distribution of verbal borrowings.

3. Bilingual Competence

Code-mixing and other processes of variation raise the question of the place of variation and its significance for language theory. According to Chomsky (2000, p. 119), “the human language faculty and the (I-)languages that are manifestations of it qualify as natural objects”. This approach—that “regards the language faculty as an ‘organ of the body’ ”—has been labeled the “biolinguistic perspective” (cf. Hauser et al. 2002; Chomsky 2005). In the internalist (i.e., biologically, individually grounded) perspective that we adopt, a variation in situations of contact between two or more dialects (linguistic communities) is in fact not qualitatively different from variation within the same community, or even within the productions of a single speaker. Again, according to Chomsky, “There is a reason to believe that the computational component is invariant, virtually... language variation appears to reside in the lexicon” (Chomsky 2000, p. 120). Suppose then that the lexicon is the locus of linguistic variation—in the presence of a uniform, invariant, computational component, and of an invariant repertory of interface primitives, both phonological and conceptual. We take this to mean that there is a universal conceptual space to be lexicalized, and variation results from different partitions of that space. Our idea is that the so-called functional space is part of the conceptual space defined by the lexicon, and there is no separated functional lexicon that varies along the axis of overt vs. covert realization.

The phenomena of code-switching and code-mixing show different degrees of regularity depending on the interaction between the languages involved. A classic approach of mixing phenomena is based on the idea that there are structural constraints on the mixed phrases. Poplack (1980), with regard to the code-switching of Spanish-English in a Puerto Rican community in New York, concludes that code-mixing is structurally restricted by the equivalence constraint in (8a), excluding (9a), and the free morpheme constraint in (8b), which excludes (9b) (Poplack 1980, pp. 585–86).

| (8) | a. | The equivalence constraint: |

| Code-switches will tend to occur at points in discourse where the juxtaposition of L1 and L2 elements does not violate a syntactic rule of either language, i.e., at points around which the surface structures of two languages map onto each other. | ||

| b. | The free morpheme constraint: | |

| Codes may be switched after any constituent in discourse provided that constituent is not a bound morpheme. |

| (9) | a. | *told le, le told | cf. | (Yo) | le | dije | |

| I | told | him | |||||

| b. | *eat-iendo’ |

In reality, it is far from clear that (8a) is generally valid. The literature on word-internal mixing (cf. Bokamba 1988; Muysken 2000, a.o.) argues against the free morpheme constraint on the basis of examples such as those provided by Albanian-inflected Romance nouns and verbs listed in Section 1. Nevertheless, (8b) is taken up again by MacSwan (2010, 2021), although in a minimalist approach. MacSwan (2021), in keeping with Chomsky (1995 and ff.), assumes that the syntactic structure is built on the basis of ‘the abstract properties encoded in each lexical item’:

A bilingual grammar has the special challenge of representing potentially conflicting requirements in a single system. For instance, a Farsi-English bilingual will use Farsi OV word order with a Farsi verb, even if the object is English, and English VO word order with an English verb, even if the object is Farsi. Despite these contradictory requirements for Farsi and English, bilinguals expertly navigate the two systems, never deviating from these patterns. To capture these facts, the architecture of a bilingual grammar must have the capacity to represent linguistic diversity in a way that captures the structure of each language separately and in interaction.MacSwan (2021, pp. 98–99)

The conclusion is that the new items added to the linguistic knowledge of a bilingual ‘take on’ the language-particular features. In bilinguals, different lexicons coexist, with different idiosyncrasies and syntactic properties, whereby “Code-switching is formally the union of two (lexically-encoded) grammars, where the numeration may draw elements from the union of two (or more) lexicons” (MacSwan 2005, p. 5). As to the constraint against the internal code-mixing, MacSwan, of course, is aware of well-known evidence against constraints such as (8b) and pursues a constraint-free approach. However, he concludes that this type of mixing is blocked by the fact that the interpretive PF components of the involved languages have different rules, and, therefore, we cannot expect code-mixing phenomena within a word (the PF Disjunction Theorem; MacSwan 2021, p. 100). In his terms, the hybrid forms that we have considered are loan words.

However, as we will discuss in the following sections, the ‘intertwining’ between Arbëresh and Romance lexical material also involves inflectional devices, for example, the inflection of the perfect—not just lexical bases. Moreover, mixing includes phonological properties, such as, for instance, the [h] outcome for *f in the native Albanian lexicon of Vena. Similarly, the shared vowel and consonant patterns in San Marzano’s and Vena’s Romance lexicon are compatible with the hypothesis that borrowing, specifically in contact contexts, involves a mechanism of code-mixing between shared grammars.

3.1. The Morphological Approach

In the treatment of bilingualism-dependent phenomena, obviously, a crucial role is played by the theoretical approach. A current morphological model such as Distributed Morphology identifies morphology with an autonomous component, in which sub-word elements (affixes and clitics) are seen as ‘dissociated morphemes’. They convey a type of information ‘separated from the original locus of that information in the phrase marker’ (Embick and Noyer 2001, p. 557) and involve post-syntactic rules of linear adjacency (local dislocation) (Embick and Noyer 2001). Thus, agreement and case morphemes are not represented in syntax, but they are added post-syntactically ‘during Morphology’ by the Late insertion mechanism. The undesirable result of this model is that there may be morphological elements devoid of any syntactic and interpretive import (Embick 2010). In other words, morphological rules may have the effect of modifying or deleting φ-features relevant to syntax, contributing to obscuring syntax. In this, Late Insertion has the role of deus ex machina, with ad hoc and distortive effects7.

We pursue a different approach to morphology, whereby morphology is part of the syntactic computation and there is no specialized component for the morphological structure of words (Manzini and Savoia 2017a, 2017b, 2011a; Savoia et al. 2018, 2019; Manzini et al. 2020a, 2020b)-a direction that is now also being pursued by other authors, such as Collins and Kayne (2021). The lexical elements, including morphemes, are fully interpretable and contribute to realizing the syntactic structure. This excludes late insertion and other adjustments provided by Distributed Morphology, such as impoverishment, fusion, and fission of φ-features, i.e., the ad hoc manipulation of terminal nodes. Finally, agreement, the property traditionally triggering head-raising, is understood as the result of the Minimal Search of (bundles of) features able to identify the same referent.

The formation of complex words is due to the Merge operation that takes roots and affixes, i.e., sub-word elements, and combines them, in the same way as other lexical or syntactic objects. This procedure includes the ‘head raising’, which is the classic movement of the head, i.e., the mechanism by which verbal (and nominal) heads are joined to affixes and positioned in the cartographic structure. In the more recent production of Chomsky, ‘head raising’ is seen as a problematic case insofar as it does not entail semantic effects, and, structurally, it is counter-cyclic (Chomsky 2020, p. 55). Along these lines, Chomsky (2021, p. 30 and 36 ff.) speaks of the illegitimate nature of head movement by observing that V-to-T raising is unjustified because ‘interpretation is the same whether a verb raises to INFL or stays in-situ’. He assumes that the Merge operation can create the combination of morphemes in complex words:

The first step in a derivation must select two items from the lexicon, presumably a root R and a categorizer CT, forming {CT, R}, which undergoes amalgamation under externalization, possibly inducing ordering effects […]. With head-movement eliminated, v need no longer be at the edge of the vP phase, but can be within the domains of PIC and Transfer, which can be unified. EA is interpreted at the next phase.(Chomsky 2021, p. 36)

The amalgamation gives rise to complex forms such as [INFL [v, Root]], subject to externalization. Now, the external argument is interpreted in the phase of T by the inflected form of the verb, and v is not involved in the procedure. In keeping with this approach, we conceptualize categorizers such as v, n, as the bundles of φ-features that characterize the functional content of words entering into the agreement operations (Manzini 2021; Baldi and Savoia 2021). Based on this approach, the syntax is projected directly from lexical items, including lexical bases and inflectional material.

Morphology substantially involves the combination of morphemic heads with roots. In the minimalist model we apply, the agreement is accounted for as the morphological manifestation of the identity between referential feature sets corresponding to the arguments of the sentence. If words are formed by combining the uncategorized lexical root with morphological elements, we must conclude that inflectional morphemes select for the contexts, the root and its immediately attached morpheme (cf. Marantz 2001, 2007), to which they merge8.

3.2. Code-Mixing

In keeping with this conceptualization of morphological objects, let us consider first the question of code-mixing within words. We compare the realization of the same nominal base, in (10a), in the Romance dialect of Vena, and in (10a’) for the indefinite and (10c) for the definite alternant in Arbëresh; the same verbal base is compared in (10b) in the Romance dialect of Vena, and, in (10b’), in Arbëresh.

| (10) | a. | hɔrmikul-a/hɔrmikul-i | b. | krij-u/krið-i/krið-ɛ/krið-i-mu |

| ant-fsg/-pl | believe-1sg/2sg/3sg/1pl | |||

| ‘ant/ants’ | ‘I believe, you believe/(s)he believes/ we believe | |||

| a’. | hɔrmikul/hɔrmikul-a | b’. | krið-i-ɲa/ krið-i-n | |

| ant/-pl | believe-1sg/2sg/3sg | |||

| ‘ant/ants’ | ‘I believe/you believe/(s)he believes’ | |||

| c. | hɔrmikul-a/hɔrmikul -ətə | |||

| ant-fsg.Def/ant-pl.Def | ||||

| ‘the ant/the ants’ | ||||

| Vena di Maida | ||||

A possible hypothesis is that the bilingual grammar of the speakers includes a single root, able to combine with the inflectional exponents of Arbëresh or the Romance dialect, as in (11a) for the noun and (11b) for verbs. Here, φ indicates the bundle of φ-features that characterize the plural form hormikul-a/i ‘ants’ or the third-person form krið-in/ɛ ‘(s)he believes’. The distribution of the inflectional exponents depends on two different morphological systems based on different lexical entries, as in (11a’)O and (11b’) and obeys two types of selection constraints in correspondence to the different syntactic contexts, as in (11a”) and (11b”).

| (11) | a. | [ φ [R hɔrmikul ] aArb/iCal ] | b. | [φ [R krið ] inArb/ɛCal ] | ||

| a’. | Arbëresh | a = pl | b’. | Arbëresh | in = sg | |

| Romance | i = pl | Romance | ɛ = 3sg | |||

| a”. | a/i ←→ R] __ | b”. in/ɛ ←→ R] ___Vena | ||||

By hypothesis, in bilingual grammars, the lexical bases which are identical both in the Romance dialect and Arbëresh can be recorded once in the grammar of the speaker. The specific morphosyntactic devices separate the two languages, as suggested in (11). This proposal is supported by the fact that in borrowed verbs, the thematic vowel, i.e., the vocalic element inserted between the root and the inflection, coincides with that of the corresponding Romance form. In fact, in the Arbëresh of Vena, the verbal borrowings are based on the thematic stem root+TV, whereby, for instance, hum-a-ɲa ‘I smoke’ has the TV -a- as Calabrian hum-a-mu ‘we smoke’, and krið-i-ɲa ‘I believe’ has -i- like the Calabrian verb krið-i-mu ‘we believe’. Unlike Vena, San Marzano’s Arbëresh uses the TV -ɔ- for the verbal loans, such as in pəndz-ɔ-ɲ ‘I think’.

3.3. Phonological Phenomena

Before we give up this data, let us consider how the forms of the source language, i.e., the Romance dialect, are phonologically connected to the corresponding forms of receiving language, i.e., Arbëresh. The point is relevant with regard to the relationship between the two lexical entries, that is, if the forms are in a loan relationship or in a code-mixing relationship. Venot languages, i.e., Arbëresh and the Romance dialect known by speakers, share crucial properties. The low-mid stressed vowels system [ɛ ɔ] contrasts with the system of neighboring Calabrian dialects, where metaphony creates a diphthongized alternant before –i/u. As shown below, (12a) compares the borrowings in Arbëresh, (12b), the outcomes of the Romance dialect of Vena, and (12c) the forms of the contact Calabrian dialect of Iacurso.

| (12) | a. | martɛʎ-i | ‘the hammer’ | |

| ‘hammer-msg.Def’ | ||||

| aɲɛʎ-i | ‘the lamb’ | |||

| ‘lamb-msg.Def’ | ||||

| lɛndzɔl-i | ‘the sheet’ | |||

| sheet-msg.Def | ||||

| Arbëresh (from contact) | ||||

| b. | martɛʎʎ-u/martɛʎʎ-i | |||

| ‘hammer-msg/mpl’ | ||||

| aɲɛʎ-u | ||||

| ‘lamb-msg’ | ||||

| lɛntsɔl-u/lɛntsɔl-a | ||||

| ‘sheet-msg/fpl’ | ||||

| Romance dialect of Vena | ||||

| c. | martiɐʐ-u/martɛʐ-a | |||

| ‘hammer-msg/fpl’ | ||||

| aɲiaʐ-u | ||||

| ‘lamb-msg’ | ||||

| lɛntsuɐl-u/lɛntsɔl-a | ||||

| ‘sheet-msg/fpl’ | ||||

| Romance dialect of Iacurso | ||||

The data in (11a,b) also show that Arbëresh and the Romance dialect present the outcome [ʎ]/[ʎʎ] instead of the retroflex of near dialects, realized as [ʐ] in Iacurso in (13c). Finally, all varieties considered share the outcome [h] after the original *f, as exemplified in (13a,b,c).

| (13) | a. | hɔrmikul-a | ‘the ant’ | |

| ant-fsg.Def | ||||

| hadalic-i | ‘the apron’ | |||

| apron-msg.Def | ||||

| buh-a | ‘the toad’ | |||

| toad-fsg.Def | ||||

| huma-ɲa | ‘I smoke’ | |||

| smoke-1sg | ||||

| Arbëresh (from contact) | ||||

| b. | haddal-ɛ | ‘apron’ | ||

| apron-msg | ||||

| hormikul-a | ‘ant’ | |||

| ant-fsg | ||||

| hum-u | ‘I smoke’ | |||

| smoke-1sg | ||||

| Romance dialect of Vena | ||||

| c. | himmin-i | ‘women’ | ||

| woman-pl | ||||

| huɐk-u | ‘fire’ | |||

| fire-msg | ||||

| hormikul-a | ‘ant’ | |||

| ant-fsg | ||||

| haddal-ɛʐ-a | ‘apron’ | |||

| apron-Eval-fsg | ||||

| Romance dialect of Iacurso | ||||

Arbëresh applies this phonological change to its original lexicon as well, as in the cases in (14).

| (14) | i | hɔrtə | ‘strong’ | (from the original Albanian i fortë) |

| msg.Def strong’ | ||||

| cah-a | ‘the neck’ | (from the original Albanian cafa) | ||

| neck-fsg.Def | ||||

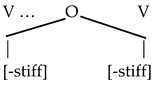

If we now move to the Arbëresh of San Marzano, we find a comparable situation, where the phonology of Arbëresh and that of the contact Southern-Apulian dialects share important features (for a detailed analysis of the phonology of San Marzano Arbëresh, cf. Belluscio and Genesin 2015). In particular, laryngeal properties of obstruents are affected by a process whereby the original voiced and voiceless consonants converge into partially voiceless outcomes, along a continuum between voicelessness and [-stiff] folds realization, i.e., weakly voiced segments, as suggested in (15) (cf. Savoia 1980, 2015b). This process favors partially voiced results in the intervocalic position, with the consequence that in these dialects the alternant with the voiceless obstruent tends to be the basic form, possibly realized also in the initial position. It is interesting to note that this type of pronunciation in the Abëresh of San Marzano was already documented in the traditional texts collected by Bonaparte (1884, 1891), Hanusz (1888), and Meyer (1891), which recorded both voiced and voiceless alternants (cf. Savoia 1980).

| (15) |  |

The most typical outcomes include the alternation [p] ~ [β], [t] ~ [ð], and [x k] ~ [ɣ], as in (16a) for San Marzano and (16b) for the Apulian contact variety of Monteparano.

| (16) | a. | u hapə ~ u haβə | ‘I open’ | |

| ujə-ðə ~ ujə-tə | ‘the water’ | |||

| ɲə ðɛmbə ~ ɲə təmbə | ‘a tooth’ | |||

| ja ðavv-a ~ ja tavv-a | ‘I gave it to her/him’ | |||

| krak-u ~ krag-u | ‘the arm’ | |||

| ʎʎa-ɣəʃ-ɲa ~ ʎʎa-kə-ʃ-ɲa‘I washed myself’ | ||||

| San Marzano | ||||

| b. | nipɔtɛ ~ nibɔt̬ɛ | ‘nephew’ | ||

| ʃtɛ ddurm-i ~ turm-i | ‘you are sleeping/you sleep’ | |||

| krɛt-u ~ krɛð-u | ‘I believe’ | |||

| Monteparano | ||||

These data seem to weaken the idea that the systems involved in bilingual grammar have different phonological constraints. Generally, in prolonged contact, phonologies overlap or, at least, end by including fundamental phonetic patterns.

An anonymous reviewer asks whether alternants such as Arbëresh hɔrmikul-a ‘the ant’ and Romance hormikul-a ‘ant’ (cf. (10a,a’)) are cases of code-mixing or imply loan. The previous discussion aims to overcome this contrast, insofar as it assumes that at least a part of the lexicon in the contact competence can be traced back to a single system comprising the bases available for different syntactic computations, i.e., the rules of word formation. This means that the language knowledge of speakers includes different selection rules expressing the distribution of the morphological exponents, as in (11a’,a”) and (11b’,b”), on which the same basic syntactic rule of Merge operates in forming inflected words (cf. Savoia and Baldi 2022).

4. Convergence in Verbal Structures

The Romance and Arbëresh systems of Vena share the pattern of auxiliary selection in which have occurs in active, middle-reflexive, and unaccusative, except in the passive and stative periphrasis, where be occurs. In Romance and Arbëresh, the participle does not agree in have contexts, in (16a,b,c) and (16a’,b’,c’). In be contexts, it agrees, as in (16d) for the Romance dialect and in (16d’) for Arbëresh. In fact, the Romance distribution is independently attested in Calabrian dialects (Manzini and Savoia 2005), and all Arbëresh dialects form the middle-reflexive with (j)u and the auxiliary have as in (16b). However, this congruence can in turn favor mixing effects.

| (16) | a. | (sta kamisa) | l | avia | ripɛtts-a-tu | ||

| a’. | (kumiʃə-nə) | ɛ | kɛʒ | ripɛtts-a-rə | |||

| this shirt(-Acc) | it | I.had | darn-TV-PP | ||||

| ‘(This shirt) I had darned it’ | |||||||

| b. | m | avia | sɛtt-a-t-u | ||||

| me | have.Impf-3sg | sit-TV-PP-msg | |||||

| ‘I sat down’ | |||||||

| b’. | ju | kiʃə | sɛt-a-rə | ||||

| MP | have.Impf-3sg | sit-TV-PP | |||||

| ‘I sat down’ | |||||||

| c. | avi-anu | vɛn-u-tu | |||||

| have.Impf-3pl | come-TV-PP | ||||||

| ‘They had come’ | |||||||

| c’. | kiʒ | ard-urə | |||||

| have.Impf.3sg | come-PP | ||||||

| ‘(s)he has come’ | |||||||

| d. | st-a | kamis-a | ɛ | ripɛtts-a-t-a | |||

| this-fsg | shirt-fsg | is | darn-TV-PP-fsg | ||||

| ‘This shirt is darned’ | |||||||

| d’. | kjɔ | kumiʃ | ɐʃt/kiʎɛ | ɛ | ʎa-rə/ʎaʃt-u-rə | (ŋga ajɔ) | |

| this | shirt | is/was | fsg.Def | wash-(TV)-PP | by her | ||

| ‘This shirt is/was washed (by her)’ | |||||||

| Vena | |||||||

A consequence of contact is provided by the fact that Vena’s Arbëresh grammar has acquired the participle suffix -t for be contexts from Romance. This inflection appears in the verbal bases of Romance origin, where it alternates with the Albanian inflection –r, cf. (17a) vs. (16b’) and (17b-b’) vs. (16d’). As we noted in the previous section, the verbal loans preserve the TV; thus, -t is merged to the TV and followed by the agreement inflection –a for the plural and lacks the pre-posed article. Specifically, it behaves like the adjectival borrowings examined in Section 2. The latter property separates these participles from a sub-class of the participle in -t(ə), which is independently documented in Albanian for some verbal classes (Demiraj 1986, 2002). These forms, unlike the participles -t considered here, select the appropriate article, as in (17c).

| (17) | a. | jiʒə | sɛt-a-t-a | ||

| be.impf-3pl | sat-TV-PP-pl | ||||

| ‘They were seated’ | |||||

| b. | kjɔ kumiʃ | ɐʃt | ripɛts-a- t | (ŋga ai) | |

| this shirt | is | darn-TV-PP | by him | ||

| ‘This shirt is darned (by him)’ | |||||

| b’. | kitɔ kumiʃ | ki:ʎɛn | ripɛtts-a-t-a | (ŋga ai) | |

| these shirts | were | darn-TV-PP-pl | by him | ||

| ‘These shirts were darned (by him)’ | |||||

| c. | kiˈʎɛ | i | ʎag-t | ||

| (s)he.was | msg.def | wetted | |||

| ‘(S)he has been wetted’ | |||||

| Vena | |||||

Again, we can assume that the participles of verbal loans and the corresponding forms in the Romance variety share the same internal structure. Applying the amalgamation procedure suggested by Chomsky (2021) (cf. Savoia and Baldi 2022), we can assume that these participles are created as in (18) by Merge, which operates on morphemes, the root, and the inflectional elements, combining them into a complex word. As shown, (18a) and (18b) amalgamate the participial form of Romance/Arbëresh type; meanwhile, (18c), i.e., the plural agreement, only applies to the Romance type. Furthermore, (18d) illustrates the selection constraints that regulate the distribution of the inflectional elements, whereby the TV is inserted only in the subset of roots that occur both in Arbëresh and in the Romance variety. φ indicates the bundle of features associated with amalgam formed by Merge.

| (18) | a. | < ripɛttsR, aTV/φ > → [φ [R ripɛtts]-a ] |

| b. | < [φ ripɛtts-a ], t/rə PP → [PP [φ ripɛtts-a ] t/rə] | |

| c. | < [PP [φ ripɛtts-a ] t], apl> → [φ ripɛtts-a-t-a] | |

| d. | TV ←→ R Romance___ | |

| t PP ←→ TV ___ | ||

| apl←→ tPP ___ | ||

| Vena | ||

Comparable conditions emerge in the perfect, which in the sub-set of Romance-Arbëresh roots is formed by the addition of the inflection -ʃt/-st, corresponding to the morpheme -st/-ʃt in the Romance variety. As indicated in (19a), Arbëresh inserts -ʃt/–st in all the persons, unlike the Romance paradigm which has -st/-ʃt only in second person, in (19b). Arbëresh also shows the morphological alternant –v in first/second singular and –u in third singular, which in turn coincide with the Romance inflection –v- in krið-i-v-i ‘I believed’ and –u in the third singular ‘(s)he believed’. This paradigm includes both the verbal bases with Romance etymology and native Albanian bases with the vocalic theme, as in (19c).

| (19) | a. | ripɛtts-a-st-a/ripɛtts-a-v-a | b. | ripɛtts-a-i |

| ripɛtts-a-st-ɛ/ripɛtts-a-v-ɛ | ripɛtts-a-st-i | |||

| ripɛtts-a-st-i/ripɛtts-a-u | ripɛtts-a-u | |||

| ripɛtts-a-st-əmə | ripɛtts-a-mɛ | |||

| ripɛtts-a-st-ətə | ripɛtts-a-sti-vu | |||

| ripɛtts-a-st-ərə | ripɛtts-a-ru | |||

| ‘I darned, etc.’ | ||||

| krið-i-st-a/kriði-v-a | krið-i-v-i | |||

| krið-i-st-ɛ/kriði-v-ɛ | krið-i-st-i | |||

| krið-i-st-i/kriði-u | krið-i-u | |||

| krið-i-st-əmə | krið-i-mɛ | |||

| krið-i-st-ətə | krið-i-sti-vu | |||

| krið-i-st-ərə | krið-i-ru | |||

| ‘I believed’, etc.’ | ||||

| c. | ʎ-a-st-a | |||

| ʎ-a-st-ɛ | ||||

| ʎ-a-st-i/ʎ-a-u | ||||

| ʎ-a-st-əmə | ||||

| ʎ-a-st-ətə | ||||

| ʎ-a-st-ərə | ||||

| ‘I washed’, etc. | ||||

| Vena | ||||

The internal structure of the forms in (19) brings to light an inflectional system partially shared by Arbëresh and Romance grammars. In the sub-set of Romance/Arbëresh roots, we find a common rule which inserts the TV, as in (18a). The inflected form is yielded by amalgamating the agreement inflection to this thematic form, as in (20a,b).

| (20) | a. | < [φ [kriðR] iTV ], stpast > → [φ [ [kriðR] iTV ] stpast ] |

| b. | < [φ [ [kriðR] iTV ] stpast], i/ɛ2sg > → [φ [[kriðR-iTV] st] i/ɛ2sg] | |

| Vena | ||

| (21) | C | T | v | VP |

| [φ/T [kriðR-iTV] stpast] i/ɛ2sg] | ||||

| Vena | ||||

As indicated, (20b), that is, the inflected verbal form, is able to realize the properties associated with the inflectional position of the sentence, at the phase C-T, in (21), as suggested by Chomsky (2021) (cf. the discussion in Section 3).

5. The Case System

The reduction and reorganization phenomena highlight the weakness of certain grammatical sub-systems, such as the case paradigm, on which contact with Romance grammar exerts a continuous influence. The changes in the case system seem to be particularly interesting insofar as the system is, all in all, preserved, but with morphophonological simplification and a general reduction of the forms. For the sake of clarity, shown in (22)–(23) is the paradigm of the case usually instantiated by Albanian varieties, including most of the Arbëresh dialects (here, that of San Benedetto Ullano). The definite and the indefinite paradigms must be distinguished, where the definite realizes three specialized case exponents.

| (22) SG | Definite | Indefinite | |||||

| F. | M. | F. | M. | ||||

| Nominative | vajz-a | burr-i | ɲə | vaiz | burr | ||

| Accusative | vaiz-ən | burr-i-n | ɲə | vaiz | burr | ||

| Oblique (gen/dat) | vaiz-ə-s | burr-i-t | ɲəi | vaiz-ɛ | burr-i | ||

| (23) PL | Definite | Indefinite | ||

| F. | M. | F. | M. | |

| Nominative | vajz-a-t | burr-a-t | vaiz-a | burr-a |

| Accusative | vaiz-a-t | burr-a-t | vaiz-a | burr-a |

| Oblique (gen/dat) | vaiz-a-vɛ-t | burr-a-vɛ-t | vaiz-a-vɛ | burr-a-vɛ |

| San Benedetto Ullano | ||||

The main properties are synthesized in the following scheme:

| (24) | -a | indefinite plural nominative and accusative in some sub-classes: burr-a ‘men’/vaiz-a girls’ |

| definite feminine nominative context: vajz-a ‘the girl’ | ||

| -ɛ | indefinite singular oblique in feminine (and indefinite plural in a sub-set of feminine)-i definite masculine singular nominative: burr-i ‘the man’ masculine singular oblique: burr-i ‘of/to a man’/burr-i-t ‘of/to the man’ | |

| -n | definite singular accusative: vaiz-ə-n ‘the girl’, burr-i-n ‘the man’ | |

| -t | definite plural nominative, accusative and oblique, both with bare stems, e.g., ʃpi-t ‘the houses’, kəmb-t ‘the feet’, cɛn-t ‘the dogs’ and with stems including the plural inflections, such as, for instance, -a, burr-a-t/vaiz-a-t ‘the men/the girls’, vaiz-a-vɛ-t ‘of/to the girls’, burr-a-vɛ-t ‘of/to the men’, in masculine singular oblique, burr-i-t ‘of/to the man’, in singular neuter nominative and accusative, diaθ-t ‘the cheese’ | |

| -s | definite feminine singular oblique: vaiz-ə-s ‘to/of the girl’ | |

| -vɛ | indefinite plural oblique: vaiz-a-vɛ ‘of/to girls’, burr-a-vɛ ‘of/to men’ | |

| i, t(ə), s(ə), ɛ/a occur also as linkers—pre-nominal articles—introducing the post-nominal or | ||

| predicative adjectives and genitives, as in burr-i i mað ‘man.the the big, i.e., the big man’ (Manzini and Savoia 2011b). |

Nominative and accusative generally coincide, except for the singular definite where accusative introduces the exponent -n; the inflection of plural can coincide with the definiteness element inserted in the nominative singular feminine, here -a. The distribution of the exponent -t in the singular oblique definite and in the plural definite suggests that -t is an element of definiteness.

Before making some brief considerations on the nature of the case, let us consider the type of change that has re-organized the system of post-positive articles and case markers in the dialect of San Marzano (Savoia 1980; Belluscio and Genesin 2015). We see that the exponent -i- of the singular masculine occurs on the right of the inflectional cluster, closing the inflectional string. The pattern exemplified in (25)–(26) for the lexical base vaɲɲun- ‘girl/boy’ encompasses all the lexical sub-classes, apart from the plural inflection, which includes the morpheme –(d)r- only in certain classes and not obligatorily.

| (25) SG | Definite | Indefinite | ||

| F. | M. | F. | M. | |

| Nominative | vaɲɲun-j-a9 | vaɲɲun-i | ɲə vaɲɲun-ɛ | ɲə vaɲɲun-ə |

| Accusative | vaɲɲun-ənə | vaɲɲun-ə-ni | ɲə vaɲɲun-ɛ | ɲə vaɲɲun-ə |

| Oblique | vaɲɲun-ə-sə | vaɲɲun-ə-ti | ɲəi-ti vaɲɲun-ɛ | ɲəi-ti vaɲɲun-ə |

| (genitive/dative) |

| (26) PL | Definite | Indefinite | ||

| F. | M. | F. | M. | |

| Nominative | vaɲɲun-(drə-)tə | vaɲɲun-(drə-)tə | vaɲɲun-dr-ɛ | vaɲɲun-dr-ɛ |

| Accusative | vaɲɲun-(drə-)tə | vaɲɲun-(drə-)tə | vaɲɲun-dr-ɛ | vaɲɲun-dr-ɛ |

| Oblique | vaɲɲun-drə-vɛ | vaɲɲun-drə-vɛ | vaɲɲun-drə-(vɛ) | vaɲɲun-drə-(vɛ) |

| (genitive/dative) | ||||

| San Marzano | ||||

Thus, we find preserved the original distribution of case morphemes in the relevant contexts in (27), although, as we will see, there are contexts in which the case system is not applied. As indicated, (27a,a’) illustrate the occurrence of the nominative, singular, and plural, while (27b) illustrates the occurrence of the accusative and (27c) that of the oblique.

| (27) | a | ka | ardrə | vaɲɲunn-i / | gru(v)-j-a | ||

| Have.3sg | come | boy-msg.Def/woman-fsg.Def | |||||

| ‘The boy/the woman has come’ | |||||||

| a’. | kannə | ardrə | vaɲɲun-drə- tə/ | burr-ə-tə /atɔ vaz-ə-rə | |||

| Have.3pl | come | girl-pl-Def/ | man-pl-Def/those girl-pl-Def | ||||

| ‘The girls/the men/those girls have come’ | |||||||

| b. | kammə parə | vaɲɲunn-ə-nə/gru-ə-nə | /burr-ə-ni/vaɲɲun-(drə-)tə/burr-ə-tə | ||||

| have.1sg seen | girl-Acc.fsg/woman-Acc.fsg/man-Acc.msg/boy-pl-def/man-Def | ||||||

| ‘I have seen the girl/the woman/the man/the boys/the men’ | |||||||

| c. | kamm- | j-a | tənnə | vaɲɲun-ə-ti/vaɲɲun-drə- vɛ/gru-ə-sə | |||

| have.1sg | Dat-it | given | boy-Dat.Def/boy-pl-Dat/woman-Dat.def | ||||

| ‘I have given it to the boy/to the boys/to the woman’. | |||||||

| San Marzano | |||||||

A crucial property of the Albanian case system (Manzini and Savoia 2012, 2014a, 2014b) is that in indefinite singular forms, only obliques are marked, in (22), by the morpheme -ɛ for the feminine and -i for the masculine, both exponents also associated with definiteness. In fact, -i is also the definite nominative, and both ɛ and i occur also as the pre-adjectival/genitival articles, as in (28a) for feminine and (28b) for masculine in the dialect of San Benedetto Ullano and, analogously, in (29a,b,c) for the dialect of San Marzano.

| (28) | a. | kjɔ | gru-a | əʃt | ɛ | ʎart | ||

| this.fsg | woman-fsg | is | fsg | tall | ||||

| ‘this woman is tall’ | ||||||||

| b. | ai | gaɲun | əʃt | i | mað | |||

| that.msg | boy | is | msg | big | ||||

| ‘that boy is big’ | ||||||||

| San Benedetto Ullano | ||||||||

| (29) | a. | ajɔ | gru-ɛ | iʃt | ɛ | mirə | |||

| that.fsg | woman-fsg | is | fsg | good | |||||

| ‘this woman is good’ | |||||||||

| b. | ai | burr | iʃt | i | mirə | ||||

| that.msg | boy | is | msg | good | |||||

| ‘that boy is good’ | |||||||||

| c. | vaɲɲunn-i | i | maðə | ||||||

| boy-Def | msg | big | |||||||

| ‘the big boy’ | |||||||||

| San Marzano | |||||||||

Our idea is that the content associated with these exponents encompasses two elementary predicates, i.e., definite/definiteness and the inclusion, part-whole relation ⊆, possibly together with φ-features of gender (Savoia and Manzini 2010; Manzini and Savoia 2011b, 2012, 2014a, 2014b; Manzini et al. 2020b). The interesting point is that its combination with a nominal root gives rise to a nominative, a definite form of accusative or oblique merging with -n and -t, but also to the simple oblique, as in (25). Let us now focus on the morphology of plural and definiteness. We note that i, substantially similar to Italian varieties, realizes the object clitic plural as in (30a), and the oblique, in (30b)10—in this Arbëresh variety, object clitics are doubled in pre- and post-auxiliary positions.

| (30) | a. | i | kamm- | i | bbə-nə | |

| Def.pl | have-1sg | Def.pl | make-PP | |||

| ‘I have made them’ | ||||||

| b. | i-a | kann- | i-a | ðə-nnə | ||

| Def.pl-Def.sg | have.3pl- | Def.pl-Def.sg | give-PP | |||

| ‘They have given it to them’ | ||||||

| San Marzano | ||||||

Following Manzini and Savoia (2011b, 2012, 2017a, 2017b) and Savoia et al. (2018, 2019), the conceptualization of plural on a par with that of the recipient (dative or genitive) can be connected to the property part-whole/inclusion, i.e., [⊆]. The insight is that in oblique contexts, such as the oblique in masculine nouns and the dative clitic, the exponent i expresses the inclusion relation, based on the notion of zonal inclusion, whereby all types of possession fall under the same basic relation (Belvin and den Dikken 1997, p. 170). In the case of plural, the predicate of inclusion [⊆] indicates that the argument of the root, the referent, can be partitioned into subsets, in the terms suggested by Chierchia (1997). All in all, the exponent i is able to denote a definite referent. In other words, the part-whole relation contributes to identifying the argument, thereby introducing a definite reading in the nominal paradigm, as in (25), and as a pre-adjectival/genitive article (Manzini and Savoia 2012, 2014a, 2014b; Manzini et al. 2014; Franco et al. 2015), as in (29), where it agrees with the head noun. This distribution can be expressed in (31).

| (31) | i⊆ ←→ __ Adj/Gen, R__ |

The definite plural -t is able to introduce the definite plural also combining with bare stems, as in the case of the system of San Marzano in (25) vaɲɲun-(drə-)tə ‘the boys’, but in general in all dialects, as in cɛn-t ‘the dogs’, suggesting that it introduces definiteness. Taking into account the standard examples in (22) and (23), when -t takes scope over the noun to which it attaches, it contributes plurality, as in (32), by individuating a subset of the set of all things that are ‘man’. [⊆] says that the set (the property) denoted by the lexical base can include subsets.

| (32) | t = Def, ⊆ |

Crucially, -t characterizes the sub-set as definite, i.e., anaphoric in relation to discourse, as in (33).

| (33) | a. | cɛn-t | ‘the dogs’ |

| b. | the x | [x ⊆ {dog}] | |

| i.e., ‘the x such that x is a subset of the set of things with the property ‘dog’ | |||

This analysis is confirmed by the occurrence of -t as the definite oblique, in cases such as burr-i-t ‘the man.obl’ (San Benedetto Ullano), but vaɲɲunə-t-i ‘the boy-obl’ in the Arbëresh of San Marzano. As discussed above, the property of inclusion [⊆] also characterizes the dative and, in general, the contexts possessed–possessor/locative inclusion, etc. Genitives and datives specify the inclusion within a spatial or abstract zone in relation to a possessor, while locatives specify the inclusion within a referential space. Hence, the occurrence of the exponent –t in the oblique, as the complement of a noun, in (34a,a’) for masculine and feminine, or of a ditransitive as in (34b), can be seen as the realization of the inclusion relation associated with genitives/datives (possession).

| (34) | a. | biʃt-i | i | cɛn- | i-t | |

| tail-Def.msg | msg | dog-msg. ⊆ -Def/⊆ | ||||

| ‘the tail of the dog’ | ||||||

| a’. | grik-a | ɛ | matʃ-əs | |||

| mouth-Def.fsg | fsg | cat-fsg.Def | ||||

| ‘the mouth of the cat’ | ||||||

| b. | j-a | ðɛv-a | cɛn- | i-t | ||

| to.him-it | give.Past-1sg | dog-msg-Def/⊆ | ||||

| ‘I gave it to the dog’ | ||||||

| San Benedetto Ullano | ||||||

Obviously, we must conclude that –t is subcategorized for the sub-set of lexical items that we label ‘masculine’, in (35a), if it specifies the oblique within a DP, where it alternates with –s for feminine, in (35b). The Elsewhere Condition (Kiparsky 1973) favors the distribution that we find.

| (35) | a. | t = Def, ⊆ (D__ Nmasculine) |

| b. | s = Def, ⊆, D__ Nfeminine |

The inflection -a in turn specifies the plural indefinite and, in singular feminine, definiteness. It is tempting to conclude that –a is also associated with a relator similar to, but not coinciding with, [⊆]. In fact, among others, the quantificational property introduced by -a is sufficient to legitimize a definite reading in the singular or a generic plural reading.

Concluding this discussion, (36) illustrates the derivation of the definite oblique cɛn-i-t ‘the dog.Obl’ (San Benedetto Ullano), where the plural inflection –i is merged to the root, yielding the amalgam [cɛn-i] in (36a), which, in turn, is merged to –t, giving the complex form of definite oblique, in (36b).

| (36) | a. | < cɛnR, iφ > → [φ [cɛnR] i] |

| b. | < [[cɛnR] iφ], tdef/⊆> → [def/⊆ [[cɛnR] i φ] t] | |

| San Benedetto Ullano |

Finally, we tentatively characterize the morpheme -n of the accusative as the mark of specificity, which introduces the other argument in addition to the subject in transitive or the argument of prepositional contexts.

As highlighted in the previous discussion, we analyze cases as exponents of two basic properties, inclusion and definiteness/specificity, without referring to traditional notions such as nominative, accusative, and oblique (dative, genitive, locative). We use the latter labels only for descriptive reasons, but cases are traced back to the signalization of the referential properties of nouns/DPs rather than properties of the abstract representation of the sentence. This idea, initially proposed in Manzini and Savoia (2014a, 2014b), allows us to explain the possibility that the morphology of cases occurs in unexpected contexts.

5.1. Reorganization and Reduction in the San Marzano System

Coming now to the system of San Marzano in (25)–(26), the comparison with the standard system in (22)–(23) shows that, in that of San Marzano, the masculine has reorganized the distribution of case and definiteness exponents. -i is now part of the accusative and oblique definite inflections, -n-i and –t-i. So, (36) is rewritten as in (37), where -i is associated with the definite reading of the nominative, in (37a), whereas the oblique or the accusative inflections include both the definiteness and the part–whole reading, as in (37b). Consequently, the indefinite is devoid of any case mark, and the lexical system has introduced two new inflectional exponents, in front of a simpler distributional pattern.

| (37) | a. | < cɛnnəR , tDef/⊆ > → [Def/⊆ [cɛnn(ə)R] t] |

| b. | < [Def/⊆ [cɛnnəR] t], i⊆> → [def/⊆ [cɛnnəR-t] i] | |

| San Marzano |

The feminine singular pattern retains the specialized inflectional exponents, with the difference that the base now incorporates -ɛ, that is, the inflection originally associated with the oblique indefinite. In the plural, -ɛ has been generalized as the vocalic exponent, however, in complementary distribution with -tə, which is also endowed with the properties of plural realized by -ɛ, as highlighted by the comparison between (38a) and (38b), with the difference that -tə implies the part–whole reading. We tentatively characterize -(d)rə- as specialized for the operator ⊆ in a sub-set of nouns, and -ɛ as a mark of specificity (Spc), restricted to the plural. As an anonymous reviewer reminds us, specificity involves ‘picking a specifying element within a set’ and highlighting the link with the sub-set reading of –tə. The amalgamation with -tə provides the definite reading.

| (38) | a. | < [[vaɲɲunR] drə⊆], ɛSpc > → [Spc/⊆ [vaɲɲun-dr] ɛ] |

| b. | < [[vaɲɲunR] drə⊆], tə def/⊆ > → [def/⊆ [vaɲɲun-drə ⊆] tə] | |

| San Marzano |

As concluded by Savoia (1980), under the re-distribution that we have described, a clear mechanism appears whereby the expression of the case (i.e., definiteness or part–whole relation) is now completely associated with the postpositive article or the indefinite pre-nominal article in indefinite contexts. The indefinite forms coincide with the lexical bases, devoid of any kind of case inflection.

The case system shows a second drift towards the reduction in the domain of demonstratives. In Albanian varieties, demonstratives present the same pattern with three cases as nouns, such as that in (39) for San Benedetto Ullano.

| (39) | Nominative | Accusative | Oblique | |||||

| M | F | M | F | M | F | |||

| sg | ai/ki | ajɔ/kjɔ | atə/kət | atij/ktij | asaj/ksaj | |||

| pl | ata/kta | ata/kta | atirɛ | |||||

| San Benedetto Ullano | ||||||||

In San Marzano dialect, demonstratives lost the distinction between nominative and accusative singular, while preserving the specialized oblique, singular, and plural, as in (40). The result is a system in which a direct form is opposed to an indirect form. First and second personal pronouns preserve the original paradigm, as in (40′), where a common form encompasses accusative and oblique, in first and second singular and in the plural an oblique form contrast with the direct form such as that in third person.

| (40) | Direct | Oblique | ||

| M | F | M | F | |

| sg | ai/ki | ajɔ/kjɔ | ati-j/kti-j | asa-j/ksa-j |

| ‘that/this.msg’ | ‘that/this.fsg’ | ‘that/this.msg-Obl’ | ‘that/this.fsg-Obl’ | |

| pl | atɔ/ktɔ | atirə-vɛ | ||

| ‘those/these.pl’ | ‘those/these.pl-Obl’ | |||

| San Marzano | ||||

| (40′) | Nominative | Oblique | Direct | Oblique | |

| 1st | u | mua | nɛ | nɛ-vɛ | |

| 2nd | ti | ti-ðə | ju | ju-vɛ | |

| San Marzano | |||||

As indicated, (41a) and (41b) illustrate the distribution of nominative, (41c) shows the accusative, and (41d) the oblique.

| (41) | a. | ka | ardrə | a-i burrə | /a-jɔ | vazə | ||

| have.3sg | come.PP | that-msg man | /that-fsg | girl | ||||

| ‘that man/that girl have come’ | ||||||||

| b. | kannə | ardrə | a-t-ɔ | burrə(-rə) | ||||

| have.3pl | come.PP | that-pl | men-pl | |||||

| ‘those men have cone’ | ||||||||

| c. | ka-mmə | parə | ajɔ vazə/atɔ | vaz-rə/ai burrə/atɔ burrə | ||||

| have-1sg | seen | that girl/those girl-pl/that man/those men | ||||||

| ‘I have seen that girl/those girls/that man/those men’ | ||||||||

| d. | ka-mm- ja | tənnə at-i-ðə burrə/as-a-j vazə/atirə-vɛ burrə/vazə | ||||||

| have-1sg Dat-it given that-Dat.msg man/that-Dat.fsg girl/those.Dat.pl men/girl | ||||||||

| ‘I have given it to that man/to that girl/to those men/to those girls’ | ||||||||

| San Marzano | ||||||||

We see that only the inclusion relationship is maintained. However, since bare nouns do not express cases even in these contexts, the expression of the case is associated only with the element of definiteness.

5.2. The Neuter

Arbëresh dialects spoken in Southern Italian communities preserve the so-called neuter inflection attested in old documents (Demiraj 1986) but now no longer surviving in standard and other varieties spoken in Albania, where it has been replaced by masculine morphology. The specialized morphology for neuter encompasses a sub-class of substance nouns such as diaθ ‘cheese’, uj ‘water’, miaʎ ‘honey’, miʃ ‘meat’, barr ‘grass’, etc. The data from S. Benedetto Ullano will provide us with the typical pattern of the neuter morphology, whose first characteristic is that the singular definite inflection of neuter nouns is -t, i.e., the same as in plural forms of count nouns (Manzini and Savoia 2012, 2018; Baldi and Savoia 2018a, 2018b).

The neuter attested in San Benedetto Ullano in (42) presents the definite nominative/accusative singular inflection –t in (42a), the demonstrative determiner at-a/kt-a in (42b), and the pre-adjectival article tə in (42b), all coinciding with definite plural forms. Meanwhile, (42c) illustrates the occurrence of the neuter as the object of a transitive, with –t in the definite form, preceded by a demonstrative and followed by an adjective introduced by the linker tə. The comparison with count nouns highlights the fact that the inflectional exponents and determiners of neuter nouns coincide with the plural inflectional exponents of the plural count nouns, as in (43c) and (43d), where the forms ata/kta ‘those/these’ of demonstratives and the inflection -t characterize the plural of feminine and masculine nouns; on the contrary, singulars have the demonstrative ki, kjɔ and ai, ajɔ as in (43a) and (43b). Moreover, these examples show that neuters agree with the third singular of the verb, as in (42a,b). On the contrary, (43c) illustrates the plural agreement of the verb with a plural count noun, introduced by the same inflectional properties that in the neuters do not trigger plural agreement.

| (42) | a. | diaθ-t | /kət-a diaθ | /at-a diaθ | ŋgə | mə | pəɾc-ɛ-n | ||||

| cheese-Def/this cheese | /that-pl cheese | not | 1ps | please-TV-3sg | |||||||

| ‘I don’t like (the) cheese/that cheese/this cheese’ | |||||||||||

| b. | at-a | diaθ | əʃt | tə | mir | ||||||

| that-pl | cheese | is | pl | good | |||||||

| ‘That cheese is good’ | |||||||||||

| c. | bie-it-a | diaθ-t | /kət-a diaθ frisku/diaθ-t | tə | barð | ||||||

| buy-Past-1sg | cheese-Def | /that-pl cheese fresh/cheese-Def | pl | white | |||||||

| ‘I bought (the) cheese/that fresh cheese/the white cheese’ | |||||||||||

| San Benedetto Ullano | |||||||||||

| (43) | a. | aj-ɔ/kj-ɔ | grua | əʃt | ɛ | ʎart | ||||

| that-fsg/this-fsg | woman | is | fsg | tall | ||||||

| ‘This/that woman is tall’ | ||||||||||

| b. | a-i/k-i | burr | əʃt | i | ʎart | |||||

| that-msg/this-msg | man | is | msg | tall | ||||||

| ‘This/that man is tall’ | ||||||||||

| c. | kət-a /at-a | gra | / | burr-a | jan tə | ʎart-a | ||||

| this-pl/that-pl | woman.fpl/ | man.m-pl | are pl. | tall-pl | ||||||

| ‘These/those women/men are tall’ | ||||||||||

| d. | burr-a-t | tə | mir | /vaiz-a-t | tə | mir-a | ||||

| man-pl-Def | pl | good | /girl-pl-Def.pl | pl | good-pl | |||||

| ‘the good men/the good girls’ | ||||||||||

| S. Benedetto Ullano | ||||||||||

In the Calabrian varieties, the neuter oblique has the singular inflection -i-(t) that we find in masculine count nouns, as evidenced by the comparison between (44a) for neuter and (44b) for masculine.

| (44) | a. | ɛ | vur-a | pəɾpaɾa | at- | ij | diaθ- i /miaʎ- i |

| 3sg | put.Past-1sg | in front of | that-msg- | Obl | cheese-Obl/honey-Obl | ||

| ‘I put it in front of this/that cheese/honey’ | |||||||

| b | ɛ | vur-a | purpaɾa | at- | ij | cɛlc- i | |

| 3sg | put.Past-1sg | in front of | that-msg. | Obl | glass-Obl.msg | ||

| ‘I put it in front of that glass’ | |||||||

| S. Benedetto Ullano | |||||||

Not all dialects retain this distribution. The loss of neuter leads to diverse possible solutions, whereby masculine or feminine inflection is selected on demonstratives and in adjectival constructions. However, in all the dialects that select the masculine or feminine agreement, nominative and accusative definite forms preserve the inflection–t; in other words, this exponent keeps characterizing this subset of nouns, separating it from the masculine class in –i and the feminine class in –a. What changes is the type of agreement, which implies masculine or feminine demonstratives and linkers/adjectives, according to the different varieties.

In the dialect of Vena (Central Calabria), with the sub-set of nouns in –t, as in (45a), the demonstratives, adjectives, and pre-nominal articles have the masculine inflection, in (45b), similar to the other masculine forms, in (45c).

| (45) | a. | diaθə-tə | |||||

| cheese-Def | |||||||

| ‘the cheese’ | |||||||

| b. | k-i | diaθə | ɐʃt | i | mirə | ||

| this-msg | cheese | is | msg | good | |||

| ‘this cheese is good’ | |||||||

| c. | k-i | ɲəʹri | /at-ɔ | ɲɛrəs | |||

| this-msg | man.msg | /those-pl | man.mpl | ||||

| ‘this man/those men’ | |||||||

| Vena di Maida | |||||||

Most Arbëresh dialects select feminine inflection on demonstratives and linkers/adjectives in agreement contexts. This system characterizes the varieties at the border between Apulia and Lucania and includes San Marzano’s variety (Savoia 1980; Manzini and Savoia 2007). As in the other varieties, the –t morphology embraces nominative and accusative, in (46a) and (46d). As shown, (46b) and (46c) illustrate the occurrence of the feminine agreement on the linkers in predicative and adjectival contexts and on demonstratives. The oblique is realized by the feminine inflection –sə, as in (46e).

| (46) | a. | mə pərc-ɛ-kə-tə | ujə-tə | /miʃ-tə | /miar-t | ||||||||

| 1sg please-MP-3sg | water-Def | /meat-Def | /honey-Def | ||||||||||

| ‘I like the water/the meat/the honey’ | |||||||||||||

| b. | aj-ɔ | /kj-ɔ | miɛlə | /ujə | /miʃə | ||||||||

| that.fsg /this.fsg | flour | /water | /meat | ||||||||||

| ‘that/this flour/water/meat’ | |||||||||||||

| b’. | a-i | /k-i | burrə | /aj-ɔ/kj-ɔ | gru-ɛ | ||||||||

| that.msg/this.msg | man.msg | / | that.fsg/this.fsg | woman.fsg | |||||||||

| ‘that/this man’ | ‘that/this woman’ | ||||||||||||

| c. | ujə-tə | iʃt | ɛ | ŋgrɔɣərə/friddu | |||||||||

| water-Def | is | fsg | hot | /cold | |||||||||

| ‘the water is hot/cold’ | |||||||||||||

| d. | biɛ-mmə | aj-ɔ | miɛlə/miʃ-tə | /cɔ | miaʎə | ||||||||

| give-1sg | that.fsg | flour/meat-Def | /this.fsg | honey | |||||||||

| ‘give me that flour/the meat/this honey’ | |||||||||||||

| e. | sapɔr-i | tə | miʃə-sə | /miaʎə-sə | |||||||||

| taste-msg | .Def | meat-Obl.fsg/honey-Obl.fsg | |||||||||||

| ‘the taste of the flour/the meat/the honey’ | |||||||||||||

| San Marzano | |||||||||||||

Other original neuter nouns have adopted the declension of feminine or masculine. For instance, diah ‘cheese’, has the feminine inflection –a. So, its morphosyntactic behavior comes to coincide with other mass nouns such as vɛr-a ‘the wine’ and kripp-a ‘the salt’, which have an original feminine inflection, as in (47a,b).

| (47) | a. | diah-a | /vɛr-a | /kripp-a | mə pərc-ɛ-kə-tə | |

| cheese.fsg/wine.fsg | /salt.fsg | me please-TV-MP-3sg | ||||

| ‘I like the cheese/the wine/the salt’ | ||||||

| b. | kammə | blɛrə | diahə-nə | /vɛrə-nə | /krippə-nə | |

| have.1sg | buy.PP | cheese-Acc.fsg/wine-Acc.fsg/salt-Acc.fsg | ||||

| ‘I bought the cheese/the wine/the salt’ | ||||||

| San Marzano | ||||||

On the whole, among the different varieties, a clear preference for feminine morphosyntax emerges, which led the original neuters to assume feminine agreement and feminine exponent in the oblique. The occurrence of a sub-set of feminine mass nouns such as vɛr ‘wine’ and krip ‘salt’ could contribute to enhancing this solution.

Before addressing the question of the change in the feminine agreement, consider the relation between the neuter and the plural inflection. It is natural to think that the selection of the plural inflection –t, corresponding to the part–whole relation (cf. (31)), and of plural demonstratives by neuters is connected to the mass content of this subset of nouns, a link documented in the literature for different languages (Baldi and Savoia 2018a, 2018b; Manzini and Savoia 2017a, 2017b, 2018). The occurrence of the plural exponent –t on a non-countable singular suggests that the same part–whole operator is relevant. In this context, however, the interpretation implies the existence of non-atomic parts in the mass continuum denoted by the base. In other words, a singular mass noun is treated like a type of plural count noun, as both include a multiplicity of parts. Manzini and Savoia (2017a, 2017b) and Savoia et al. (2018) argue for an analysis that identifies the mass content with the [aggregate] interpretive property, used by Chierchia (2010) to characterize the common core of mass and plural denotation, i.e., a weakly differentiated set of parts/atoms (in the terms of Acquaviva 2008). In (48a), the lexical root diaθ ‘cheese’ is merged with the exponent –t, [⊆]. In other words, the part–whole reading of -t is compatible with the (weakened) plurality of the base, making it visible, as suggested by the selection rule in (48b).

| (48) | a. | < [diaθR], tdef/⊆ > → [def/⊆diaθ-t] |

| b. | tdef/⊆ ←→ Raggregate__ | |

| San Benedetto Ullano | ||

An interesting point is that these formations trigger the singular form of the verb. In other words, in these nouns, -t is interpreted as the exponent of mass content, and a plurality of individuals is not involved. We simply appeal to the idea of the Minimal Search procedure whereby the inflection of third person is saturated by the mass noun. Within the DP, on the other hand, demonstratives express the implicit plurality of the mass noun by assuming in turn the plural form.

In cases where interference with Italian systems has worked in reducing the agreement to a twofold system of Romance, we must conclude that not only the verb but also the demonstratives in the DP agree in terms of the gender classes. We see that feminine is generally preferred in grammars where a new agreement system is introduced. We can only suppose that feminine introduces semantic properties more suitable to realizing the aggregate content of the neuter sub-class. In fact, the feminine inflection –a in Albanian is associated with both plural and feminine singular interpretations. In the case of Arbëresh varieties, we noticed that –a characterizes masculine and feminine plurals such as burr-a ‘men’/vajz-a ‘girls’ and feminine definite singular nominative vajz-a ‘the girl’. This distribution recalls behavior of –a in many Italian Romance varieties, including standard Italian, where –a specifies both feminine singular and (a class of) plural. Manzini and Savoia (2017a, 2017b), Savoia et al. (2018), and Manzini et al. (2020a) propose that the –a is associated with the [aggregate] reading.

Moreover, feminine in Albanian varieties is associated with mass reading, where it triggers the plural agreement, as in (46). This behavior could suggest that the feminine is also available for an aggregate interpretation in Albanian. In other words, this distribution seems to evoke a content including both singular and plural, similar to Romance feminine. Here, we only suggest that this referential property could explain the preference for feminine agreement for mass nouns in the reorganization phenomena occurring in Arbëresh dialects.

6. The Sentence: Causatives

In Italo-Albanian dialects, the causative verb, i.e., a form of bəɲ ‘I do’, embeds a finite inflected sentence introduced by the particle tə, which in the Arbëresh of Vena is preceded by the preposition pə ‘for’ (Savoia 1989a, 1989b; Manzini and Savoia 2007)11. In Vena, the causee can be lexicalized as nominative in (49a) or accusative in (49b) when the embedded verb is intransitive, and as a dative when the embedded verb is transitive, in (49c). If the causee is realized by a DP, it can occur both in the final position or between the causative verb and the introducer elements pə tə, as in (49b,c). The causee can furthermore be lexicalized on the higher causative verb as an accusative clitic, as in (49d,e):

| (49) | a. | bɐ-ɲɲa | (pə) | tə | ha-rə | diaʎ-i | ||||||||

| make-Pres.1sg | for | Prt | eat-Sub.3sg | boy-Def | ||||||||||

| ‘I make the boy eat’ | ||||||||||||||

| b. | u | bɐɾ-a | (ɲeriu-nə) | pə | tə | ikənə | (ɲeriu-nə) | |||||||

| I | make-Past.1sg | man-Acc | for | Prt | run-Pres.3sg man-Acc | |||||||||

| ‘I made the man run’ | ||||||||||||||

| c. | u bɐɾ-a | (buʃtri-tə) | tə | pi-ɾə | krumiʃti-nə | (buʃtri-tə) | ||||||||

| I make-Past.1sg dog-Dat.Def | Prt | drink.Subj.3sg milk-Acc | dog-Dat.Def | |||||||||||

| ‘I make the dog drink the milk’ | ||||||||||||||

| d. | mə | bɐ-ɲɲ-ənə | (pə) | t | ɛ | ʃɔxə | ||||||||

| 1sg | make-Pres-3pl | for | Prt | 3sg | see.Pres.3sg | |||||||||

| ‘They make me see him’ | ||||||||||||||

| e. | ɛ | bɐ-ɲɲ-ənə | (pə) | t | ɛ | ʃɔ-rə | ||||||||

| 3sg | make-Pres-3pl | for | Prt | 3sg | see-Subj.3sg | |||||||||

| ‘They make him/her see it’ | ||||||||||||||

| Vena | ||||||||||||||

The data in (49) are surprising, in that they display a realignment of the causative construction of Albanian on the Romance case pattern, despite the presence of an embedded finite verb. Manzini and Savoia (2007) use data such as (49b-e) to argue against the idea that agreement with I/T is a sufficient condition to determine the nominative assignment (Chomsky 2001, 2008). By the same token, examples such as (49b,d-e) show that agreement with v is not a necessary condition for the assignment of accusative, etc. (cf. Baker and Vinokurova 2010). Actually, if we follow the proposals of Chomsky (2020, 2021), the problem is no longer crucial.

We can think that the structures in (49) are influenced by Romance causative, where the case assignment is regulated by the causative verb fare. More precisely, the DP corresponding to the causee can assume the properties of accusative or dative/oblique insofar as the search procedure permits to identify it with the referent expressed by the agreement inflection of the embedded verb. We saw in Section 5.1 that both accusative and oblique express a definite reference. Naturally, deviant interpretation can be expected, but in this framework, nothing excludes this procedure, available in a grammar in which the transfer effect of the Romance structure is strong.

Something similar characterizes the Arbëresh variety of San Marzano, where the causative provides two possible constructs. In the present, an invariable causative verbal form bəðə/bətə, including the base bə ‘make’ and the particle tə, embeds an inflected verb, as in (50a). This construct is possible also when the causative is embedded under the auxiliary have, as in (50b). The examples show that, in these constructs, the subject of the embedded sentence is in the nominative, such as vaɲɲunn-ja ‘the girl’ and cɛnn-i ‘the dog’.

| (50) | a. | (u) bə ðə | frɛɲɲə | vaɲɲunn-ja | ||

| I causative | sleep-3sg | girl-fsg.Def | ||||

| ‘I make the girl sleep’ | ||||||

| b. | ka | bəðə | biei | cɛnn-i | ||

| have.3sg | made | fall.3sg | dog-msg.Def | |||

| ‘(s)he made the dog fall’ | ||||||

| San Marzano | ||||||

Past contexts introduced by have generally present a structure where the embedded verb has the form of a participle, as in (51a,b,c).

| (51) | a. | ka | bə ðə | iku-rə | /flɛttə-rə | cɛnnə-n-i | /cɛnn-i | |||