Abstract

R-pronouns are R-words which feature as pronouns in prepositional phrases (among other things). They are common in Dutch and German (e.g., D. daarmee, G. damit, lit. ‘therewith’, ‘with that’, D. erna, G. danach, lit. ‘hereafter’, ‘after this’). This contribution concerns a quantitative study of variation in R-pronouns in modern Moroccan and Turkish ethnolectal Dutch. In conversational speech of bilingual speakers of Moroccan Dutch, Turkish Dutch and two groups of monolingual ‘white’ Dutch (one of them being the control group), R-pronouns appear to vary in three dimensions: the R-pronoun can or cannot be realized (with the latter option violating the norms of Dutch); if it is realized, the R-pronoun and the preposition can or cannot be split (both options conform the norms of Standard Dutch), if the R-pronoun is not realized, then either another pronoun is used instead or there is no substitute (both variants violate the norms of Dutch). For all three dimensions of variation, statistical analyses were carried out, starting from a total of 1160 realizations by 52 representatives of the four groups. The analyses involved three internal parameters and four social ones. The results serve to answer research questions concerning the origin of the variation, its place in the verbal repertoires and the social spread of the variation.

1. Introduction

Germanic languages such as Dutch, German and English have a category that syntacticians refer to as R-words. R-words are adverbs (such as e.g., Dutch er, ‘there’, and hier, ‘here’) and an occasional Wh-word (such as waar, ‘where’) that contain an /r/ and that can occur as pronouns in prepositional phrases (henceforth PPs), among other things.1 Whenever R-words serve as pronouns, they are also called R-pronouns. (In the context of the phenomenon at issue we use both notions as synonyms). Here are first some examples to elucidate the phenomenon and its distribution.

Independent of the semantic properties of the antecedent, Dutch pronouns can appear as a subject (1a, 2a) or object (1b, 2b). In PPs, pronouns which do not refer to human beings are typically replaced by R-words2 (2c and compare 1c):

| (1a) | Waar is Jan? Hij is met vakantie. |

| ‘Where is Jan? He is on holiday.’ | |

| (1b) | Ik heb hem al een tijd niet gezien. |

| ‘I have not seen him for a while.’ | |

| (1c) | Ik wacht al enkele dagen op hem. |

| ‘I have been waiting for him for several days.’ | |

| (2a) | Waar is de auto? Hij is in de garage. |

| ‘Where is the car? It is in the garage.’ | |

| (2b) | Ik heb hem gisteren naar de garage gebracht. |

| ‘I took it to the garage yesterday.’ | |

| (2c) | Ik wil *met hem/er mee op vakantie. |

| ‘I want to go on holiday with it.’ |

R-pronouns can, but need not, be split without changing the meaning, e.g.,

| (2c’) | Ik wil er morgen mee op vakantie. |

| ‘I want to go on holiday with it tomorrow.’ | |

| (3a) | Hij zegt niks er over. |

| (3b) | Hij zegt er niks over. |

| ‘He says nothing about it’ |

As in endogenous varieties, in emerging Moroccan and Turkish varieties of Dutch3 both unsplit and split PPs with an R-pronoun occur.

In contrast to the variation between split and unsplit PPs with an R-pronoun, using a regular pronoun instead of an R-pronoun in contexts such as those in (3c) violates the standard norms and the same applies to the omission of an R-pronoun without a substitute as in (3d).

| (3c) | Hij zegt niks over het. |

| (3d) | Hij zegt niks over. |

Apart from er, there are also other R-words that may appear in PPs in these and similar contexts; these include daar, ‘there’, hier, ‘here’, waar, ‘where’, but also ergens, ‘somewhere’, nergens, ‘nowhere’ and overal, ‘everywhere’ (the phonological form of all these adverbs contains /r/, hence the designation). e.g.,

| (4a) | Daar over bestaan nog veel misverstanden |

| ‘There are still many misunderstandings about this’ | |

| (4a’) | Daar bestaan nog veel misverstanden over |

| ‘There are still many misunderstandings about this’ | |

| (4b) | Ik klim hierop |

| ‘I climb on this’ | |

| (4b’) | Ik klim hier zo meteen op |

| I will climb up here in a moment |

R-words can also function as locative adverbs, see e.g.,

| (5a) | Hij is er dit jaar al drie keer geweest |

| ‘He has been there three times already this year’ | |

| (5b) | Je moet hier je handtekening zetten |

| ‘You have to sign here’ | |

| (5c) | Zullen we vanavond ergens iets gaan eten? |

| ‘Shall we have dinner somewhere tonight?’ |

In this contribution, we focus on ethnolectal variation in the pronominal use of R-words. Ethnolects are language varieties which originated in specific ethnic groups, initially as L2 systems. In Section 2 of this contribution, we briefly discuss the phenomenon of ethnolectal variation and the main approaches to its study. The presentation goes on to describe (in Section 3) the central research questions, the methodology, the data and a number of findings from the ‘Roots of Ethnolects’ project, which has been carried out for over fifteen years now at the Meertens Instituut (Amsterdam) and Radboud Universiteit (Nijmegen). The project focuses on ethnolectal variation in present-day Turkish and Moroccan Dutch.

From Section 4 onwards, this contribution will focus on variation in the realization of R-words in PPs, Following a summary of the data and the methods (Section 5), the findings from the analyses of the variation in PPs with an R-pronoun in interactional speech collected for the Roots of Ethnolects project (in Section 6) will serve to address the three main research questions central in the Roots of Ethnolects project (Section 7).

2. Ethnolectal Variation

What makes ethnolects unique is that they are often rooted in substrate effects of the original language of an ethnic minority group, in L2 acquisition phenomena and the surrounding native dialects. In other respects, much is still unclear about ethnolects. How stable can they become? Do they spread?4

There has been much debate on the definition of the notion of ethnolects and its relation to the concept of youth language. Whereas, ethnolects are more or less stable and typically their usage is at most semi-conscious, ethnicity plays an role through the background of the speakers, and involved features are phonological and syntactic, youth language is dynamic and its usage is (semi-)conscious; ethnicity plays a role only temporarily and the features are usually lexical and pragmatic in nature (cf. Auer 2003; Muysken 2013). Youth language5 thus seems to be more of a register or even jargon. However, there may not be a sharp dividing line between ethnolects and youth languages; perhaps they form the extreme ends of a continuum.

Useful overviews of important early work and more recent studies, both from an international perspective and regarding past and present ethnolects of Dutch, can be found in Muysken (2013) and Hinskens (2019).

In general, there are two distinct approaches to the study of ethnolects: the language centered and the ethnographic approach. Whereas the ethnographic approach conceives language systems as infinite resources from which speakers may freely choose to shape their identity, the language centered approach tries to disentangle the laws, generalizations and restrictions on these resources. The language centered approach typically stands out by:

• The use of terminology such as ‘ethnolect’, ‘multi-ethnolect’ and ‘multicultural variety’,

• ‘Objective’ definitions of ethnicity (language, race, descent);

• Quantitative methodology (often in the Labovian tradition);

• Focus on form, structure and the distribution of variation;

Representative studies include Cheshire et al. (2011), Hoffman and Walker (2010) and Van Meel (2016).• A macro-social angle.

The ethnographic approach typically stands out by

• The use of terminology such as ‘style’ and ‘(pan-)ethnic style’6;

• ‘Subjective’ definitions of ethnicity as a social construction, in which perception plays a role7;

• Attention for both responsive and initiative (agency-driven) uses of linguistic features;

• Interpretive methods;

• Focus on social meaning (‘indexicality’) and its fluidity;

Representatives of this type of approach include Eckert (2008, 2012) and Benor (2010).• A micro-social perspective.

In contrast to the language centered approach, in the ethnographic approach language change is not a central concern.

3. The Roots of Ethnolects Project

The research project ‘The roots of ethnolects. An experimental comparative study’ focuses on variation in the speech both of young people with mainly Dutch-born forebears and of Dutch-born children of migrants of Turkish and Moroccan descent (N speakers = 96). It zooms in on ethnolects of Dutch in the cities of Amsterdam and Nijmegen and addresses a number of research questions8.

The approach is language-centered rather than ethnographic (Hinskens 2011). One set of research questions concerns the linguistic makeup of ethnolects: to what extent are they rooted in substrates, in surrounding endogenous non-standard varieties, or typical of second language acquisition phenomena? A second set concerns the place of the ethnolect in speaker repertoires. Can speakers of an ethnolect shift to more standard varieties and to non-ethnic non-standard varieties? A third set concerns the distribution of features across ethnic groups.

The data for this project were collected following a factorial design (see Table 1), with equal numbers of 10 to 12 and 18 to 20 years old male speakers from Amsterdam and Nijmegen (cities which are located in different dialect areas), and from three backgrounds: Moroccan, Turkish and mainly Dutch-born forebears.

Table 1.

Speaker design of the Roots of Ethnolects project.

The speakers with Moroccan (M) and Turkish (T) backgrounds grew up bilingually in the Netherlands and are also native speakers of a Dutch variety. The (monolingual) Dutch teenagers with mainly Dutch-born forebears were split into a group with strong ties (D) and one with weak or no network ties (C) with boys from other ethnic groups.

Except for the boys who have few, if any, friends from other ethnic groups, four recordings were made of every single speaker; three involved conversations, one with a peer whose main background was Moroccan, one with a peer with a Turkish background and one with a peer with mainly Dutch forebears but with friends from other ethnic groups. Additional recordings comprised individual elicitation sessions.

The features studied so far include the dentalization and devoicing of /z/, the monophthongization and lowering of the diphthong /ɛi/, the contrast /ɑ-a/ in particular with regard to duration and place of articulation, the marking of grammatical gender in determiners and adnominal flection and, recently, the palatalization of /s/ before velar fricatives9.

For the three sets of research questions, the findings from the quantitative analyses of ample data for these linguistic variables can be summarized as follows. Substrate effects are only discernible for the dental variant of /z/ (which is probably rooted in Arabic), as in, [z̪ɪn] for Dutch [zɪn] in geen zin meer10, ‘not in the mood anymore’, and possibly for s-palatalization (which may well be rooted in Turkish), as in,[ʃɣitə], Dutch [sɣitə], schieten, ‘to shoot’. L2 effects only occur in variation in grammatical gender marking in both determiners and adnominal flexion, such as, deze plein is een beetje raar, Dutch [dit plein], ‘this square is a bit strange’, and hij had gele haar [geel haar], ‘he had yellow hair’. Effects of the surrounding endogenous dialects dominate—they are visible in the devoicing of /z/–as in, [s]enuwen, Dutch [z]enuwen, zenuwen, ‘nerves’, the monophthongization and variation in the height of /ɛi/, as in, Amsterdam tr[aː]n, standard Dutch tr[ɛi]n, trein, ‘train’ and Nijmegen f[ɛː]n, standard Dutch f[ɛi]n, fijn, ‘fine’, in the place of articulation of the low vowels /a/ and /ɑ/, e.g., Amsterdam m[ɑ̩]n and m[ɛ]n for standard Dutch m[ɑ]n, man, ‘man’, g[a:ɔ]n, standard Dutch g[a]n, gaan, ‘to go’, Nijmegen vand[ɑ]n, standard Dutch vand[a]n, vandaan, ‘from’, and possibly s-palatalization (a grave realization of /s/ is not uncommon in the Amsterdam urban dialect).

Stylistic variation due to accommodation of the interlocutor was found in the use of the dental variant of /z/, in the fact that fewer standard grammatical gender determiners were used in interactions with speakers of Moroccan and Turkish Dutch, and in variation in the realization of /a/ before obstruents. As to the latter effect, Turkish Dutch speakers produce the shortest /a/’s when speaking to endogenous ‘white’ Dutch, whereas Moroccan Dutch speakers produce the longest /a/’s when speaking to endogenous ‘white’ Dutch. For both groups, whilst speaking with members of the other ethnic minority group, there is hardly any difference in /a/ duration. All these effects are instances of audience design (Bell 1984); that does not hold for the style effect in the variable use of monophthongal variants of /εi/. Of the various groups of speakers (two cities, two age groups, three types of language background), only in the case of 20-year-old Turkish-Dutch speakers from Amsterdam does the variation in the monophthongization of /εi/ in speech towards the different groups replicate the relative production of each of those groups.

Spread to other groups has been established for the dental variant of /z/, which originated in Moroccan Dutch (which has a certain covert prestige, indexing roughness and toughness; Nortier and Dorleijn 2008), but has clearly been adopted by the Turkish Dutch. Spread to other groups has also been established for the endogenous local dialect variants of /ɛi/, which are being abandoned by teenagers from monolingual Dutch families in favor of new, supra-regional non-standard [ai]. The older dialect variants [ɛ:] (Nijmegen) and [a:] (Amsterdam) are being rescued by speakers of Moroccan and Turkish Dutch; the dialect features are thus being recycled as ethnolect features.

Other aspects of Turkish Dutch are discussed in Backus (2015) and Indefrey et al. (2015), among others. A brief but thorough sketch of Moroccan Dutch can be found in Ruette and Van de Velde (2013).

3.1. The Present Study

In the conversations recorded for the Roots of Ethnolects project, we find variation between the following types of realizations of R-pronouns (illustrated with variants of the same sentence in (6)):

with the unsplit and split construction, respectively (6a, b), omission of the R-pronoun without a substitute (6c) and R-pronoun omission with another pronoun as a substitute (6d). In one of the conversations recorded for the Roots of Ethnolects project, the variant without a substitute pronoun, (6c), occurs in the utterance in (7):

| (6a) | Ja, maar hij zegt niks er over |

| (6b) | Ja, maar hij zegt er niks over |

| (6c) | Ja, maar hij zegt niks over |

| (6d) | Ja, maar zegt niks over het |

| ‘Yes, he says nothing about it’ |

| (7) | Voor de rest weet ik niks over | (a12d01) |

| ‘For the rest I know nothing about [it]’ |

Here and in all subsequent examples taken from the interviews, the code between brackets identifies a specific individual speaker. Here and generally ‘a’ and ‘n’ stand for Amsterdam and Nijmegen, respectively, 12 and 20 for the age groups 10–12 and 18–20 year olds, and ‘m’, ‘t’, ‘c’ and ‘d’ for Moroccan Dutch, Turkish Dutch and white Dutch (specifically those without and with strong network ties with boys from other ethnic groups), respectively.

All four variants illustrated in (6), including (6c) and (6d) which are ungrammatical, occur in the recorded language use of the Turkish Dutch and the Moroccan Dutch boys—and remarkably also in the groups of Dutch young men with a non-migrant background, but not to the same extent in the different groups.

As will have become clear from the above, there are several interrelated dimensions of variation in our data for R-pronouns in prepositional phases. The variation in the various dimensions will be studied quantitatively on the basis of conversational speech data collected for the project. Before presenting the methods (in Section 5) and the results (Section 6), we will first pay more attention to R-pronouns.

4. R-Pronouns

4.1. R-Pronouns in Dutch

An R-word that functions as a pronoun, hence an R-pronoun, is called a ‘voornaamwoordelijk bijwoord’, i.e., ‘pronominal adverb’, in Dutch school grammar. The adverbial nature is evident in the differences in form that we observe in the prepositions tot (‘to’) and met (‘with’) when they combine with an R-pronoun to form a PP that functions as a pronominal adverb:

| (8a) | tot | We rijden vandaag tot de Poolse grens |

| ‘Today we drive to the Polish border’ | ||

| toe | Waar toe/*waar tot dient deze mand? | |

| ‘What is this basket for?’ | ||

| (8b) | met | Schilder je dit het best met een dunne kwast? |

| ‘Is this best painted with a thin brush?’ | ||

| mee | Hier mee/*hier met kom je nog niet tot de Duitse grens | |

| lit. This with come you not to the German border | ||

| ‘This will not take you as far as the German border’ |

The forms toe and mee can only occur as adverbs and not as prepositions:

| (8a’) | *We rijden vandaag toe de Poolse grens |

| (8b’) | *Schilder je dit het best mee een dunne kwast? |

All other prepositions do not change form when combined with an R-word in a PP.

Confusingly, the term ‘voornaamwoordelijk bijwoord’ (pronominal adverb) is also used for the entire compound (i.e., the entire PP). This is due to the fact that NPs in PPs follow the preposition, but if the NP contains an R-pronoun rather than a noun, the order is the other way round—and the final part is thus the preposition (which serves as an adverb, as seen in (8) above). The fact that moving an NP containing a noun out of a PP is not possible in Dutch but moving an R-pronoun out of a PP is, is related to this. Compare the following sentences (from Bennis and Hoekstra 1989, p. 285):

| (9a) | *Welke jongens heb je op gerekend? |

| lit. Which boys did you on count? | |

| ‘Which boys did you count on?’ | |

| (9b) | Waar heb je op gerekend? |

| lit. What have you on counted? | |

| ‘What have you counted on?’ |

Strictly speaking, given the placement, we cannot speak of prepositions in PPs such as waarop, but of postpositions or, in general terms, adpositions.

When the R-words er, hier, daar of waar (‘there’, ‘here’, ‘there’ or ‘where’, respectively) form a pronominal adverb together with a preposition, they are often written as one word11 (e-ANS 2021: 9.5); however, this does not apply to the R-words overal, ergens and nergens (‘everywhere’, ‘somewhere’ and ‘nowhere’):

| (10) | Je moet ergens in geloven. |

| lit. You have to somewhere in believe | |

| ‘You have to believe in something’ |

It is by no means possible to construct a PP with an R-pronoun with every preposition; there are about 40 Dutch prepositions (mostly from more formal registers or jargon) with which that is out of the question (e-ANS 2021: section 8.7.1.3).

As already pointed out in Section 1 and Section 3.1, one of the syntactic properties of Dutch PPs containing an R-pronoun is that they can be split without any consequences for the meaning. As a result of the splitting, the preposition is left behind; this phenomenon is therefore generally referred to as preposition stranding.12

There are three types of splitting. One type (further referred to here as type 1-splitting) results from the presence of an adverbial clause (11a), an NP (which is then an object—(11b)) or a PP (11c). Examples are:

| (11a) | ik wacht al lang er op |

| ik wacht er al lang op | |

| ‘I have been waiting for a long time’ | |

| (11b) | Eva koopt een boot er van |

| Eva koopt er een boot van | |

| ‘Eva buys a boat from it’ | |

| (11c) | hij kijkt met een verrekijker er naar |

| hij kijkt er met een verrekijker naar | |

| ‘he looks at it with binoculars’ |

Another type of splitting (henceforth type 2-splitting) results from fronting of the R-pronoun without pied-piping.13 Examples are

| (12a) | hier wacht ik op |

| ‘this is what I am waiting for’ | |

| (12b) | daar droomt ze van |

| ‘that is what she dreams of’ |

which again results in preposition stranding 14. Pied-piping would have resulted in:

| (12a’) | hier op wacht ik |

| (12b’) | daar van droomt ze |

The 3rd type is somewhat like type 1, although the NP is invariably the subject and er (and variants) is here a dummy subject (Bennis 1986) or expletive element. Examples are (from the data dealt with in this study):

| (13a) | D’r is een tekenfilm van | (a12d02) |

| Daar van is een tekenfilm | ||

| ‘There is a cartoon of it’ | ||

| (13b) | Er moesten batterijen in | (a12m01) |

| batterijen moesten er in | ||

| ‘It needed batteries’ | ||

| (13c) | Zit er iets in? | (n12t02) |

| Zit iets er in? | ||

| ‘Is there something in it?’ |

Unlike type 2, er (or a variant of er) in this type can be fronted, but pied-piping is not possible—it is possible with a related, phonologically heavier R-word like daar (13a). In the last two utterances, the R-pronoun also seems to have a locative meaning.

As the examples show, the three types of splitting can also be analyzed as extraction and fronting of the R-pronoun resulting in preposition stranding.

In standard German (possibly with the exception of standard spoken North German), PPs with an R-pronoun cannot be split as a rule (thus Beermann and Hellan 2011). English only knows a few PPs with an R-pronoun, such as thereof, herewith and wherein, with fixed combinations whose use seem to be largely confined to written language and the more elevated style levels; it is more common to use PPs such as of that, with this and in which instead (cf. e-ANs 2021: section 9.5). In Dutch and German, the use of PPs with an R-pronoun is not subject to stylistic specialization.

4.2. Turkish, Moroccan Arabic and Berber Equivalents of Prepositional Phrases Containing an R-Pronoun

The Turkish equivalent of the Dutch PP with an R-pronoun is a postposition with a complement. There are four such postpositions, but one of the forms hakk-iX-da, ‘about’, is by far the most popular; it is a very frequently occurring postposition, in which variable X is a possessive suffix that agrees with the grammatical person of the complement. This postposition governs the nominative, but in the case of pronouns and demonstratives, it governs the genitive. If the object of the postposition is explicitly expressed, then this could look like this, for example:

| (14) | Evlilik hakkında hiçbir şey söylemiyor |

| lit. Marriage about it says nothing | |

| ‘It doesn’t say anything about marriage’ |

The following utterance shows the usage of the demonstratives bu, ‘this’, and o, ‘that’, as the object of the postposition:

| (15) | Fatma’ya bun-un/on-un hakkında bir şey deme lütfen |

| lit. To Fatma this-gen/that-gen about don’t say anything please | |

| ‘Please don’t say anything to Fatma about this/that’ |

Both human and non-human antecedents are referred to with a 3sg pronoun, for example:

| (16) | onun hakkında |

| lit. 3sg-gen about | |

| ‘about her’/‘about him’/‘about it’ |

onun is also the genitive form of the pronoun o, which stands for ‘he’, ‘she’, and ‘it’. The last ‘reading’ would correspond to Dutch er over, ‘about it’. Thus, the Turkish equivalent of ‘about it’ (Dutch erover, *over het) is formed analogously to ‘about me’:

The Turkish equivalents of Dutch PPs with an R-pronoun are not split up.

| (17) | ben-im hakkımda |

| lit. 1sg-gen about | |

| ‘about me’ |

R-pronouns and pre- or postpositional phrases with an R-pronoun do not occur in Turkish. Instead, in Turkish a combination of object pronoun and postposition is used, as in (15) and (16).

In Berber (and Riffian Berber is the most relevant, given the origin of most Dutch Moroccans immigrants) there is no equivalent of an R-pronoun. Locative/quantitative Er zijn …, ‘There are...’, is expressed in Riffian Berber with din ‘there’. A preposition + person suffix is probably closest to the R-pronoun in terms of composition. So, for example:

| (18) | x ‘on’ + -s ‘3rd person’ → xas ‘on/about him/her/it’ |

However, these two elements can never be split. What does happen is the so-called attraction. Depending on the syntactic context, verbal clitics and prepositions + pronouns can occur either before or after the verb, as in, for example:

| (18a) | Wah, maca war xas iqqar walu |

| Yes, but NEG about-3SG he says-IMPF nothing | |

| ‘Yes, but he says nothing about it’ |

Here, xas precedes the verb because of the presence of the negative element war; however, xas is always mandatory (cf. Kossmann 2012).

For Moroccan Arabic, the same applies to the preposition + suffix, with the difference being that the element does not move.

5. R-Pronouns in the Roots of Ethnolects Data. Method and Approach

5.1. Speakers

The present study is based on data from 52 speakers (a proper subset of the speaker sample for the Roots of Ethnolects project at large), divided into groups determined by the speakers’ ethnic and linguistic backgrounds (Moroccan Dutch, Turkish Dutch and white Dutch with and without strong interethnic ties), age (10 to 12 years old versus 18 to 20 years old) and city of residence (Amsterdam versus Nijmegen).15 Table 2 below illustrates the speaker design for this study and the number of speakers in each group. This subset is referred to in the project as the ‘core corpus’.

Table 2.

The speaker design for the present study.

5.2. Material and Data

This study on R-pronouns is based on conversational speech (see Section 3 above). The interlocutors were peers from the same school, usually classmates. The topics were chosen by the young men themselves. To keep the conversation from falling silent, the fieldworker ensured that there were always some free newspapers as well as pictures of soccer players, pop stars, films, etc. on the table. The register was invariably casual; during most recordings the field worker would leave the room for a while.

In an earlier phase of the larger project, from each conversation ten to fifteen minutes had been roughly orthographically transcribed and annotated in ELAN (Brugman and Russel 2004). The first three minutes of each conversation were not transcribed. All transcriptions were checked by a second transcriber.

The aim of the present study was to gather at least 15 utterances containing a PP with a (realized or unrealized) R-pronoun per speaker per conversation. The transcribed and checked parts of the recordings were examined first and, wherever necessary, more observations were collected from the same recording. For the 52 speakers in the ‘core corpus’, a total of 1160 observations were eventually documented, making an average of over 22 observations per speaker.

5.3. Coding and Transcription

With the help of ELAN, each occurrence per speaker per conversation was registered with the exact time of occurrence in the conversation. Next, each occurrence of a PP with a (realized or unrealized) R-pronoun was orthographically transcribed in detail, annotated and coded for a range of social and linguistic variables. On the basis of the exploration of the data and general understanding of the phenomenon under study, per observed occurrence the following data were stored:

Social:

- speaker code (‘code spreker’)

- city (‘stad’)

- age group (‘leeftijd’)

- language background of the speaker (‘taalachtergrond spreker’)

- language background of the addressee (‘taalachtergrond gesprekspartner’)

Linguistic:

- which preposition? (‘prep’)

- does an R-word occur, yes or no?

- if an R-word occurs, then which one? ((e)r-hier-daar-waar’)

- if no R-word occurs, is there a substitute, yes, or no? (‘iets/niets’)

- if no R-word occurs and there is a substitute, is it one of these pronouns: (he)t-dit-dat-wat?

- can the PP containing an R-pronoun be split? (‘splitsing mogelijk’)

- if splitting is possible, then does it occur, yes or no? (‘splitsing?’)

- type of split (‘type splitsing’); the three types briefly discussed in Section 4.1 above

- the relevant part of the utterance in orthographic transcription (‘uiting’)

- file name (‘bestandsnaam’)

- time in the recording (in hour:minutes:seconds:milliseconds) (‘tijdstip’).

This very labor-intensive part of the study was carried out by Ariën van Wijngaarden MA.

The implementation of the variable ‘splitting possible’ (building on Section 4.1 above) needs some clarification. The variable has the values ‘yes’ and ‘no’. On the one hand, there are utterances such as:

where splitting is never possible. On the other hand, there are also utterances where splitting would have been possible if there had been an adverbial clause, an object or a PP. An example is:

| (19) | Dat is het punt waar op het leuk gaat worden | (a20c03) |

| ‘That’s the point where it’s going to be fun’ | ||

| (20) | Moet je er op slaan? | (n12t03) |

| lit. Do you have to hit on it? | ||

| ‘Do you have to hit it?’ | ||

With an adverbial clause, this utterance would have been splittable—e.g.,

| (20’) | Moet je er heel hard op slaan? |

| ‘Do you have to hit it really hard? |

and also with a PP, e.g.,

| (20”) | Moet je er met een hamer op slaan? |

| ‘Do you have to hit it with a hammer?’ |

However, because the utterance lacks an adverbial clause, an object as well as a PP (i.e., they are altogether absent in the utterance), the original utterance is coded as ‘not splittable’.

With type 2, splitting is always possible when the R-pronoun is fronted.

If, in addition to a pronominal function, er also has a presentational function (type 3), it is well-nigh obligatory in Standard Dutch to separate it from the preposition with which it forms a PP, e.g.,

Compare the unsplit variants:

| (21) | Er staat een standbeeld naast |

| ‘There is a statue next to it’ |

| (21’) | Een standbeeld staat er naast |

| (21”) | Er naast staat een standbeeld |

There were four social16 and eight linguistic parameters.17 All parameters have been coded numerically, although in the subsequent statistical analyses (see next subsection), all 12 variables have been treated as nominal in nature.

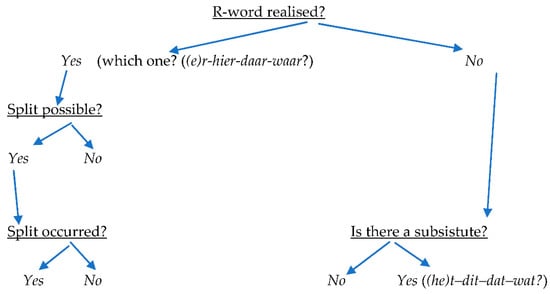

The structure of the main linguistic parameters can be visualized, as in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1.

The structure of the linguistic data.

Each scenario is illustrated here with one or more utterances from the Roots of Ethnolects conversations:

with R-pronoun—splitting is not possible:

| (20) | Moet je er op slaan? | (n12t03) | |

| ‘Do you have to hit it?’ | |||

| (19) | Dat is het punt waar op het leuk gaat worden | (a20c03) | |

| ‘That’s when it starts to get fun’ | |||

splitting is possible—splitting not occurred:

| (22) | Je had gewoon een willekeurige d’r uit kunnen pakken | (a20c02) |

| ‘You could have just picked a random one from there’ |

splitting is possible—splitting occurred:

| (23) | Misschien iets waar we dit op kunnen leggen | (n20m01) |

| lit. Maybe something where we can put this on | ||

| ‘Maybe something we can put this on’ |

no R-pronoun—no substitute pronoun

| (24) | Ik heb wel eens een keer van gehoord | (a12d01) |

| ‘I have heard of [it] once’ |

with a substitute pronoun

| (25) | Als je nou mee komt helpen met dit | (n20t04) |

| ‘If you come and help with this’ |

‘er op’ in (20) cannot be split because there is nothing in the expression to split with—that is, no object or PP (e.g., met een hamer, ‘with a hammer’) or adverbial clause (e.g., heel hard, ‘very hard’). Similarly, (19) cannot be split in any case.

5.4. Data Analyses

There are three interrelated dimensions of variation. The first dimension concerns the question of whether or not the R-pronoun is realized and what plays a role in this variation. To find this out on the basis of the conversational data, generalized linear mixed models logistic regression analyses (SPSS) were carried out. The dependent variable was R-word yes or no; this was recoded as ‘R-word drop’ no and yes, respectively. The independents were, for the random effects, speaker (‘code speaker’) and preposition and, for the fixed effects, the four social parameters. The analyses and the results will be presented in Section 6.1 below.

The second dimension of variation (to be addressed in Section 6.2 below) concerns the cases where no R-pronoun was used, and the question is whether some other pronoun has taken its place. There were a total of 101 cases where no R-pronoun was used and these were distributed among 36 speakers (for all four groups, C, D, M and T); with only representatives of groups D, M and T, there were 32 speakers and 91 observations. In both scenarios, the average number of observations per speaker (less than 3) was too small for inferential statistical analysis by (mixed models or not) logistic regression or bivariate tests. It was therefore decided not to use the individual occurrences of utterances with a PP and a realized or unrealized R pronoun as the unit of analysis, but rather speakers who either never or always appear to use another pronoun instead of an R-pronoun.

The third dimension of variation (which will be analyzed in Section 6.3 below) concerns the cases where an R-pronoun has been used and the question is whether or not the PP has been split and what plays a role in this variation. Table 3 shows the number of relevant observations aggregated over all four groups (C, D, M and T):

Table 3.

The numerical relationship between the realization or non-realization of the R-word and the splitting of the PP containing an R-pronoun in the RoE data for groups C, D, M and T.

The PPs in the remaining 603 utterances were in principle splittable; 477 of them were indeed split, the remaining 126 were not. Generalized linear mixed models logistic regression analyses were conducted on these remaining cases, albeit with 468 rather than 603 observations, as only the data for the D, M and T speakers were used.18 In the analyses the dependent variable was splitting (with yes = 1, no = 0); the independents were, for the random effects, speaker (‘code speaker’), preposition and (e)r-hier-daar-waar, and, for the fixed effects, the four social parameters and the internal factor group type of splitting.

6. Findings

6.1. Variable R-Word Drop

The central variable ‘does an R-word occur, yes or no?’ has been recoded for the analyses as ‘R-word Drop no or yes’, respectively. The analyses were based on a total number of observations of 975 for a total of 38 speakers of the groups Moroccan Dutchmen (M), Turkish Dutchmen (T) and white Dutchmen with strong inter-ethnic ties (D); in 91 cases the R-word had been dropped, in 884 cases it was realized. In the mixed models logistic regression analyses, the four social parameters were included as fixed effects.19

Restricting the analyses to a single parameter to begin with, age group emerges as the best predictor (there is a negative effect for 18–20 year-olds—i.e., they drop less than 10–12 year-olds).

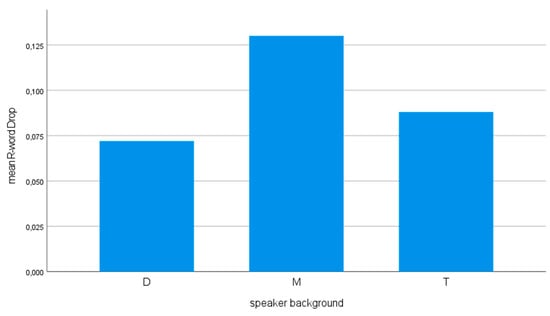

Looking at two parameters per analysis and restricting ourselves to the main effects, then the model with the speakers’ language background and the city do best, but only the speakers’ language background has a significant effect (positive for Moroccan Dutch, so they drop more than white Dutch with strong interethnic ties). The proportion of R-word-less variants, expressed in estimated marginal means, is about 0.13 among the Moroccan Dutch, 0.09 among the Turkish Dutch and 0.07 among the white Dutch of group D.

When investigating both main and interaction effects for each of the two parameters, the model with language background and speakers’ age group turns out to do best (again with a negative effect for 18–20 year-olds); however, given the AIC of 5027.143, this is worse than the speakers’ language background and city with only main effects (AIC 4995.059). Therefore, for two parameters we may have to choose the results of the latter analysis.

With three parameters, no analysis with both main and interaction effects produces an interpretable model. Of the analyses with only main effects, the model with city, age group and the language background of the interlocutor performs best, but only the factor of age had a significant effect (more specifically, a negative effect for the group of the 18–20 year-olds).

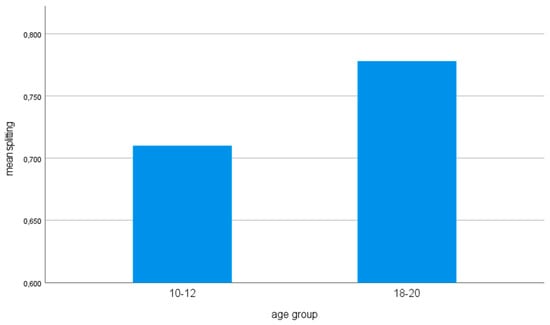

Considering the results from all the rounds of analysis, we can conclude that the background of the speakers, especially Moroccan Dutch (positive), and age group (18–20 year-olds, negative) systematically influence the omission of the R-word in PPs. The Moroccan Dutch are in the lead in omission (Figure 2 top), the 18–20 year-olds in realizing the R-word (Figure 2 bottom). The latter, and the fact that there appears to be no significant interaction effect between the age group and the language background of the speakers20, seems to indicate that language acquisition in general plays a role here. The fact that the language background of the interlocutor does not play a role anywhere probably means that there is no style variation à la Bell (1984). We will discuss and interpret the findings in Section 7 below.

Figure 2.

The relationship between R-word drop (estimated marginal means) and the language background (above) and the age group of the speakers (below).

The random factor preposition appeared to have a significant effect in all analyses as well. Are we dealing with a frequency effect or do semantic factors play a role?

In terms of their frequency of occurrence, the top 5 prepositions are as follows:21

| in | ’in; into’ | n = 137 (11 of which are R-pronounless) | ||

| +R-pron | (26) | Uh je doet ‘r schilderijen uh zeg maar in | (a12c01) | |

| ‘Uh you put paintings uh say in it’ | ||||

| −R-pron | (27) | Wordt vaak ge*a in geraced 22 | (a12d02) | instead of daar…in |

| lit. Is often raced in, ‘They often race in it’ |

| van | ‘of; from’ | n = 128 (25 R-pronounless) | ||

| +R-pron | (28) | Zijn er ook schoenen van? | (a12m02) | |

| ‘Are there shoes of this kind?’ | ||||

| −R-pron | (29) | Ja van wat? (a12t01) | iso waar van | |

| ‘Yes, of what?’ |

| op | ‘on; at’ | n = 115 (12 R-pronounless) | ||

| +R-pron | (30) | Daarop staat een kerstboom | (a12t02) | |

| ‘On it is a Christmas tree’ | ||||

| −R-pron | (31) | Ja ik ken mensen die vroeger op zaten | (a20d06) | iso er … op |

| [talking about a school] ‘Yes, I know people who used to go [there]’ |

| na | ‘after’ | 101 (1 R-pronounless) | ||

| +R-pron | (32) | En daarna heb ik ook gezegd van ja maakt niet uit | (n12d02) | |

| ‘And after that I also said: yes, it doesn’t matter’. | ||||

| −R-pron | (33) | Ben je d’r na dit nog? (a12d01) | iso hier na | |

| ‘Are you still here after this?’ |

and ex aequo:

| bij | ‘at; with’ | n = 95 (11 R-pronounless) | ||

| +R-pron | (34) | Daar kan je ook bij praten als je hebt gewonnen | (n12m02) | |

| lit. There you can also with talk when if you have won | ||||

| ‘Doing so, you can also talk when/if you have won’ | ||||

| −R-pron | (35) | Niks hoort bij dit, niks hoort bij dat | (n12m02) | iso hier bij |

| … daar bij | ||||

| ‘Nothing goes with this; nothing goes with that’ |

| voor | ‘for; before’ | n = 95 (8 R-pronounless) | ||

| +R-pron | (36) | Waarvoor komen we eigenlijk hier? | (n12t02) | |

| ‘What are we actually here for?’ | ||||

| −R-pron | (37) | Hoef je geen diploma voor te hebben, niks | (n20m04) | iso daar … bij |

| ‘You don’t have to have a diploma for [that], nothing’ |

A total of 38 different prepositions were used in the studied conversations and 16 of these prepositions have their own usage frequency. For 34 of the 38 prepositions, usage frequencies are also available for an independent source of modern spoken Standard Dutch, the Corpus Gesproken Nederlands (CGN), ‘Corpus Spoken Dutch’.23 The rankings in the usage frequencies of the 34 prepositions in both collections correlate highly significantly (Pearson’s r = 0.739, two-tailed sign. 0.000). Thus, the (proportions of) token frequencies of the prepositions in the Roots of Ethnolects material are not idiosyncratic.

However, the proportion of RwordDrop (i.e., the proportion of RwordYes to RwordYes + RwordNo) does not correlate significantly with either the frequency of use of the prepositions in the data examined (r = −0.038, two-tailed sign 0.823) or with that in the CGN (r = 0.248, two-tailed sign 0.157).

For the prepositions which occur at least 10 times in the investigated Root of Ethnolects material24 and where R-word drop occur at least once, the proportion of R-word drop (‘RwdDrop’) to the frequency of occurrence of the preposition has been calculated; this is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The percentage of R-word drop on the total number of occurrences of the prepositions (occurring at least 10 times in the data).

The measure labeled % RwdDrop shows the percentage of R-pronoun omission for the preposition in question in the ‘Roots of Ethnolects’ conversational data analyzed. These percentages are for all prepositions smaller than 20. The top 5 is formed by van (‘of; from’), naar (to), bij (‘at; with’), op (‘on; at’) and over (about, over), respectively. Insofar as there is a semantic core, these prepositions are successively generic, directional, locative, locative, and generic or locative, so also in this respect there does not seem to be a clear pattern in the effect of prepositions on R-pronoun omission.

We establish that neither frequency of use nor semantics play a role in the effect of prepositions on R-word drop and we conclude that this effect is most likely lexically specific.

6.2. Substitute Pronouns?

Where no R-pronoun is used, a speaker has two options: either to use another pronoun (the fourth type of variant, illustrated by over het, in (6d) in Section 3.1 above) or no pronoun at all (the third type above under (6c): over).

In the conversational data, an R-pronoun is sometimes replaced by another pronoun, e.g., an interrogative pronoun or a demonstrative, as in

| (29) | Ja van wat? | (a12t01) |

| ‘Yes, of what?’ | ||

| (33) | Ben je d’r na dit nog? | (a12d01) |

| ‘Are you still here after this?’ |

Sometimes nothing replaces an R-pronoun, e.g.,

| (31) | Ja ik ken mensen die vroeger op zaten | (a20d06) |

| ‘Yes, I know people who used to go [there]’ | ||

| (37) | Hoef je geen diploma voor te hebben niks | (n20m04) |

| ‘You don’t have to have a diploma for [that], nothing’ |

For the scenario in which no R-pronoun is realized, the number of observations (101 for the 36 speakers of all four groups; 91 observations for the 32 speakers of groups D, M and T) and thus also the average number of observations per speaker (less than 3) is very small, so that it is not surprising that mixed models logistic regression analyses did not yield anything.25 Indeed, any type of advanced inferential statistics seems pointless here.

Neither do the chi-square analyses for bivariate relations between the use or non-use of a substitute pronoun and each of the four social parameters26 show any significant correlation—neither for all groups (101 observations) nor for speakers of groups D, M and T (91 observations). This is probably due to the small numbers of observations per speaker. The proportion of the use of a substitute pronoun is considerably higher for the Turkish Dutch speakers (40.7%) than for the Moroccan Dutch speakers (17.1%). Conversely, the Moroccan Dutch speakers show a much higher proportion of no substitute pronouns (82.9%) than the Turkish Dutch speakers (59.3%). Overall, however, these differences are not significant.

It was therefore decided not to use the utterance with a PP and a realized or unrealized R-pronoun as the unit of analysis, but the speaker. It was determined how many speakers never use another pronoun instead of an R-pronoun and how many speakers always do so. In order to cast the net as far as possible at this level of analysis, here we look at all four groups of speakers.

36 speakers appear not to use an R-pronoun one or more times. Of these 36 speakers, 18 never use another pronoun instead of an R-pronoun. Table 5 shows the number of speakers per group for whom this is true, broken down for city and age group.

Table 5.

Number of Speakers per subgroup with No substitute pronoun27.

There are, on the other hand, 5 speakers who always use a different pronoun instead of an R-pronoun. These are one 10–12-year-old from Nijmegen in the C-group, one 10–12 year-old from Nijmegen in the D-group, two 10–12 year-olds from Amsterdam in the T-group and two 18–20 year-olds from Amsterdam in the T-group.

The group of speakers who never use another pronoun instead of an R-pronoun seem the most interesting. As shown in Table 5, this group includes twice as many Amsterdammers as Nijmegenaars, while the older age group is considerably more represented than the younger ones. As far as the linguistic and cultural background is concerned, it is the Moroccan Dutch who most often do not use any pronouns at all; the Turkish Dutch are remarkably underrepresented here. But as we saw in Section 6.1 above, the Turkish Dutch also omit significantly less R-pronouns (0.09) than the Moroccan Dutch (0.13). Remarkably, it is members of the group of the white boys with strong inter-ethnic network ties who are in second place here, while at the same time their R-word drop proportion (approx. 0.07) is slightly more than half of that of the Moroccan Dutch boys.

To what extent does the interlocutor influence the non-use of a substitute pronoun instead of an R-pronoun? Table 6 shows, per subgroup, the number of interlocutors to whom one or more speakers used (a) PP(s) without any pronoun whatsoever.

Table 6.

No substitute pronoun for a missing R-pronoun; number of addressees per subgroup.

There are some striking patterns. The difference between the age groups (20 addressees of the oldest, 11 of the youngest group) is quite large; that between Amsterdam (17 addressees) and Nijmegen (14) was less so; that between the four groups (11 D > 9 T > 8 M > 3 C), however, is not very pronounced, certainly when C is not taken into account.28 It is remarkable that the difference between Turkish Dutch and Moroccan Dutch addressees is very small, whereas it is considerable in relation to speakers (8 Moroccan Dutch, 2 Turkish Dutch).

6.3. Variable PP Splitting

There are 468 cases where splitting is possible. For these data (from 38 speakers of groups D, M and T), the question of which factors contribute to or favor splitting was investigated through mixed model logistic regression analyses, in which the four social parameters and the linguistic parameter split type are the fixed factors.

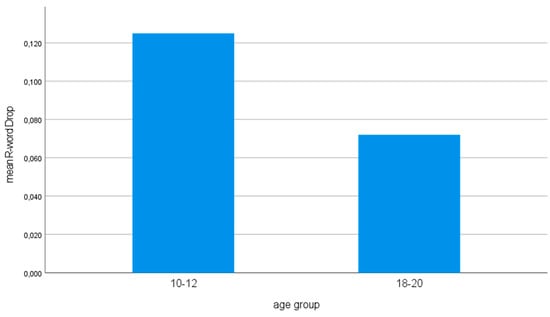

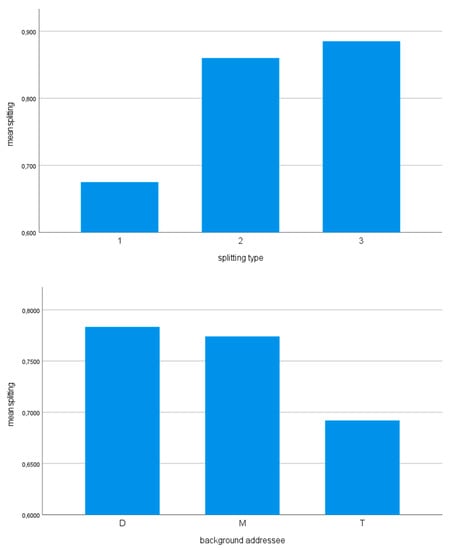

Looking at one single parameter per analysis, the type of splitting turns out to be the best predictor (there are positive effects for types 3 and 2, i.e., those types were split significantly more than type 1).

Looking at two parameters per analysis and only at the main effects, then the model with age group and language background of the addressee performs best, but only the language background of the addressee has a significant effect there (sign 0.051): there is a negative effect for the conversations with Turkish Dutch speakers, which means significantly fewer splits towards Turkish Dutch speakers than towards white Dutch speakers (with strong interethnic ties, group D). Most splits (estimated marginal mean over 0.78) occur in conversations with white Dutch speakers with strong interethnic ties, slightly less (0.77) in conversations with Moroccan Dutch speakers, and the least (0.69) with Turkish Dutch speakers.

In the analyses for two parameters each with both main and interaction effects, the language background of the speakers and age group perform best. Here, too, only the language background of the addressee has a significant effect (sign 0.051, with a positive effect for 18–20 year-olds), but given the AIC (2137.273), this model fits the data somewhat less than the one with only main effects of age and the language background of the addressee (AIC 2126.207). So, for two parameters, we opt for the results of that earlier analysis.

Looking at three parameters per analysis and only at main effects, the model with city, age group and language background of the addressee comes out best (AIC = 2127.819), but the only factor that had a significant effect (0.052, barely significant) is interlocutors with a Turkish background.

Among the analyses with three parameters and both main and interaction effects, the one with language background of the speakers, city and age group comes out best—but only the age group has a significant effect (a positive effect for 18–20 year-olds). Because of the AIC (2159.790), however, the three-parameter model discussed in the previous paragraph with only the main effects of city, age and language background of the interlocutor and an almost significant negative effect of Turkish Dutch interlocutors seems preferable.

In short, in the Roots of Ethnolects data, in addition to the split type, the addressee’s language background and age group have an effect on the split of the PP with an R-pronoun. See Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The relationship between the splitting of PPs containing an R-pronoun (estimated marginal means) and the splitting type (above), the language background of the addressees (middle) and the age groups of the speakers (below).

We establish that splitting types 2 and (even more so) 3 favor splitting (Figure 3 above). There are 51 type 3 cases in the data; of these, no more than 4 (less than 8%) are unsplit—including, e.g.,

| (38) | ’t is een spinnenweb en zit een oog erin | (n12m02) |

| ‘It is a spider’s web and [there] is an eye in it’ |

The remaining 47 type 3 cases are split and this is in accordance with the standard language norm. As is evident from (13a–c) above, not splitting is not necessarily ungrammatical in type 3, where the R-word is an expletive, but not very common. Whereas, in type 1 the splitter is an object (direct, indirect or oblique) or an adverbial clause, in type 2 the finite verb is usually immediately followed by the subject (in main clauses) or the subject (in embedded clauses), in type 3 it is the subject.

Four out of the 51 or 8% non- or sub-standard variants may seem few. But 101 out of 1160 (all groups of speakers) or 91 out of 975 (D, M and T only) for R-word drop, which violates standard standards even more, is approximately the same proportion.

We stay with the language-internal parameters for a moment. Does the type of pronoun affect variable splitting? Although the random factor R-pronoun er-hier-daar-waar does not have a significant impact in any model (in the winning models the significance is at best 0.123, elsewhere at best 0.062),29 on closer inspection, the question of whether splitting occurs seems to be somewhat related to the R-pronouns used (χ2 = 66.02 df = 3 p < 0.001). See Table 7.

Table 7.

The number of split and unsplit PPs per (realized) R-pronoun.

While in the case of er and waar (‘there’ and ‘where’, respectively), there is a relatively large number of splits, with hier and daar (‘here’ and ‘there’) there are relatively many unsplit constructions. While er is a generic adverb that is phonetically mostly reduced (cf. e-ANS 2021: section 9.5) and cliticized and waar, in addition to a Wh-word, is also a relativizer, hier and daar are adverbs with a demonstrative (respectively proximal and distal) meaning. But whatever the explanation, in the multivariate overall picture the pattern in Table 7 is at best a weak tendency.

Of the social parameters, the language background of an addressee exerts the greatest influence; in particular there is a dampening effect of Turkish Dutch interlocutors on the splitting behavior (Figure 3 in the middle). There is also an unmistakable effect of the age group factor, which involves 18–20 year-olds splitting more than 10–12 year-olds (Figure 3 below). The latter fact seemed to indicate that language acquisition also plays a role throughout. The even more prominent role of the language background of the interlocutor means that splitting is subject to style variation à la Bell (1984).

7. Discussion and Issues for Further Research

In this concluding section, we first examine the findings from the perspective of the three research questions. A brief summary is given in Table 8.

Table 8.

Answering the research questions on the basis of the findings for the R-pronouns; three dimensions of variation.

R-pronouns in PPs appear to vary in three dimensions. The first main dimension concerns the question of whether or not the R-word is dropped; dropping the R-pronoun violates the norms of Standard Dutch and is not common in other varieties of the language either.

In connection with research question 1 on the origin of ethnolect features, we first focus on sub-question 1.1: is there a substrate effect? Wherever Dutch has a PP with an R-pronoun, Turkish has a combination of a (regular) object pronoun plus postposition plus complement. And in Berber and (Moroccan) Arabic, there is always a preposition + person suffix in such contexts. Therefore, if there is an effect from Turkish, Moroccan Arabic and Berber, it is not in the direction of omitting the pronoun. In other words, there are no substrate effects from the relevant heritage languages as far as the omission of R-pronouns from PPs is concerned.

Does (second) language acquisition play a role? (sub-question 1.2)? PPs with R-pronouns are a rather complex phenomenon because of, among other things, the semantic conditioning (according to the standard norm only for non-human referents), the internal structure of the PP itself (which contains a de-adverbial pronoun; unlike any corresponding structures, here the preposition is in postposition) and the syntactic conditioning of the split. This makes it complex for L1 acquisition,30 but even more so for the acquisition of Dutch as an L2 for speakers of languages such as Turkish, Arabic and Berber, which do not have this phenomenon. R-word drop may have been a language acquisition phenomenon for the first generations of migrants, and it may continue to exist because some second language acquisition is still taking place, also for the later generations of speakers. The significant effect of the age group factor in our data (i.e., decrease in R-word drop with age) suggests that it is a language acquisition phenomenon for our speakers, for all groups actually, not only for the Moroccan and Turkish Dutch speakers.

Is R-word drop perhaps adopted from the surrounding Dutch dialects (sub-question 1.3)? In the documentation on the Amsterdam and Nijmegen urban dialects there are no indications for R-word drop from PPs. Nor did a significant effect appear anywhere in the analyzed data for the factor group city. An influence from the surrounding endogenous dialects can therefore hardly be assumed.

Research question 2 addressed the place of the ethnolect in speaker repertoires and style-shifting to non-ethnic (standard or non-standard) varieties. Judging from the research findings (presented in Section 6.1 above) there are no such effects, as shown by the lack of significance of the effect of the interlocutors’ background, our operationalization of style.

Does R-word drop spread to other groups? (research question 3). The Moroccan Dutch speakers show the highest proportion of R-word drop, the Turkish Dutch and white Dutch with strong interethnic ties significantly less. It is not inconceivable that the phenomenon spreads from the Moroccan Dutch group to the Turkish Dutch (say, to flag non-nativeness) and white Dutch (as part of a general teenage ‘anti-language’—Halliday 1976), but without further evidence this is little more than speculation.

In connection with the second dimension, ‘if R-word drop occurs, is another pronoun used instead of an R-pronoun?’, we can answer the research questions only tentatively. This is a consequence of the relatively small amount of relevant data available. Unlike for the other two dimensions of variation, the analyses are not based on the individual occurrences of the linguistic variable, but on the numbers of relevant speakers or addressees.

Concerning research question 1.1 for the scenario of no substitute pronoun: in Turkish as well as in Arabic and Berber, a pronoun is always used in the corresponding construction; so, also in connection with the use of a variant without a substitute for a lacking R-pronoun, there is no question of a substratum effect. The fact that the heritage languages always use a pronoun in the corresponding construction is consistent with the fact that there are relatively few speakers of Turkish Dutch in our data who never use a substitute pronoun. On the other hand, this is not consistent with the finding that less than 1 in 5 (to be exact 17.1%) speakers of Moroccan Dutch use another pronoun in the case of R-word drop and that primarily Moroccan Dutch speakers never use a substitute pronoun in the case of R-word drop (Table 5 in Section 6.2).

The variant with a substitute pronoun (40.7% for Turkish Dutch speakers in our sample without an R-word, and 17.1% for Moroccan Dutch speakers) may be attributable to a substrate effect; Turkish has in the relevant context a combination of object pronoun plus postposition, Berber and Arabic preposition + person suffix. The variant without a substitute pronoun may go back to the L2 Dutch of the first generations of Turkish and Moroccan Dutch, the immigrants, who had difficulty with R-pronouns since they were not transparent and were therefore difficult for L2 learners; moreover, the grammars of the heritage languages give no reason to expect that there should be such forms.

Concerning sub-question 1.3: it cannot be completely ruled out that R-word drop without a substitute pronoun is a new and as yet undocumented property of the Amsterdam vernacular, although indications from our research (Table 5 in Section 6.2) are not exactly overwhelming.

In connection with sub-question 1.2, R-word drop without a substitute pronoun (which, in as far is possible, violates the norms even more than replacing the R pronoun by another pronoun) is not a matter of language acquisition. On the contrary (and this touches on research question 2), the fact that it occurred considerably more among 18- to 20-year-old speakers, suggests that it may well be a recent sociolinguistic phenomenon, specifically an Amsterdam youth language feature. R-word drop without replacement may have covert prestige among these young people; it may also be an in-group feature and remain in use for these reasons. The analyses of our data show that R-word drop without a substitute pronoun may be sensitive to the age and city of residence of the person being addressed.

If the non-use of a substitute pronoun for a missing R-pronoun has exogenous roots, it is also conceivable, given the (admittedly scarce and relatively poor) data, that it spreads to Dutch speakers without a migration background. As is so much for research question 3.

The third dimension of variation concerns the situation where the R-word has not been dropped and the variable in question is the splitting or non-splitting of the PP.

For the findings for this phenomenon, we first discuss research question 1: where does it come from? Turkish, Moroccan Arabic and Berber do not split, so in relation to splitting, a substrate effect could be that the Moroccan Dutch and Turkish Dutch speakers split less than their white Dutch friends (group D). However, the finding that splitting in our data was not related to the language background of the speakers shows that there was no such substrate effect.

Given the significant effect of the age group factor, language acquisition (re sub-question 1.2) is indeed at issue here: the older boys split more. However, this language acquisition effect, like that for ‘unlearning’ R-word drop, applied to all groups of speakers.31

Research question 2 is whether the phenomenon is subject to style-shifting. Judging by the finding that there was slightly less splitting in the case of a Moroccan Dutch addressee and significantly less in the case of a Turkish Dutch addressee, splitting is indeed subject to style variation Bell (1984).

Finally, regarding research question 3: both splitting (or extraction and fronting) and non-splitting is in accordance with the grammar of Standard Dutch and this is no different for the dialects of Dutch, including those spoken in Amsterdam and Nijmegen (re sub-question 1.3). Only in the case of type 3 is non-splitting less common in Standard Dutch, but since there is no significant interaction effect between the type of splitting and the background of the speaker, there was no indication of the spread of non-splitting type 3 from one group to another.

We can hence conclude that there is no evidence of substrate effects anywhere, that language acquisition plays a role in R-word drop (which decreases with age) as well as in the splitting of PPs with an R-word (which increases with age), and that the surrounding native dialects probably do not play a role. Stylistic variation occurs in the non-use of a substitute pronoun in R-word-less preposition phrases and in the splitting of prepositional phrases with an R-word. Finally, insofar as R-word drop without a substitute pronoun has exogenous roots, it is possible that the phenomenon spreads to white Dutch young men with strong interethnic ties.

An additional benefit of this study is that both the variable drop of the R-pronoun and (in case of a realized R-pronoun), the variable splitting of the PP seems to be subject to lexical effects, statistically significant and sharply delineated in the first case, whereas weak and at most tendentious in the second. Both have in common that they are linguistically elusive; in the first case, the effect is demonstrably not due to the token frequency or the semantics of the preposition, in the second (to the extent that there is any effect at all) possibly to grammatical and semantic properties of the four R-pronouns used in the conversations.

The study presented here is based on analyses of the conversational data. But for some variable phonetic and morpho-syntactic phenomena, including R-pronouns in PPs, there are also recordings of individual elicitation sessions. What are the variation patterns of the R-pronouns there? Since the elicited individual data have not yet been analyzed, this is still an open research question.

There is one desideratum that goes beyond the possibilities of the Roots of Ethnolects project. The insights into the emergence and development of ethnolects could be deepened enormously in a comparative perspective. This can be achieved through the comparison with other ethnolects of Dutch as the societally dominant language, like Jewish Dutch (although that may be almost extinct), Polish Dutch, but also Surinamese Dutch as spoken in the Netherlands today. We can also enrich our insights by comparing the ethnolects of the heritage languages studied here with ethnolectal varieties of other dominant languages, say, Turkish German, Moroccan French and the like.

Funding

This research was funded in 2005-15 by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO; project number 254-70-040), the Meertens Instituut and Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Researchers interested in the data can contact the author at the e-mail address listed.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Many thanks to Ariën van Wijngaarden for the thorough work with which he transformed the recorded material into a most usable database, to Hans Bennis for the advice which came at just the right time as well as to Folkert Kuiken for his reference to literature on the acquisition of the phenomenon and to Elma Blom for the advice. Many thanks also to Ad Backus, Khalid Mourigh, Gerjan van Schaaik and Kees Versteegh for generously sharing their deep knowledge of Turkish, Berber and (Moroccan) Arabic. Many thanks to Janine Berns, Peter-Arno Coppen and Ans van Kemenade for discussing the initial findings with me and for their help and advice. Many thanks, finally, to the anonymous reviewers for the many invaluable comments and suggestions and, of course, to the 52 speakers. It goes without saying that none of these colleagues are responsible for any shortcomings of this text. The research presented here was originally to be carried out by Pieter Muysken and me, but it was not to be; before we could start, Pieter fell fatally ill. I dedicate this study to him in respectful memory. |

| 2 | There is a rule in the normative grammar of Standard Dutch that prohibits R-pronouns from referring to people, but the rule is variably violated (Broekhuis 2013, pp. 297–306; Bennis and Hinskens 2014, p. 138; 2022, p. 225), especially in informal colloquial speech (e-ANS 2021: sections 8.7.3, 8.7.3.1 and 9.5.2). |

| 3 | More on these varieties in Section 3 below. |

| 4 | Parts of the present section are based on parts of Hinskens (2019) and of Hinskens et al. (2022). |

| 5 | Dutch: jongerentaal. The late modern urban manifestations are also referred to as straattaal, lit. ‘street language’. |

| 6 | On concepts and terminology, see (Kern 2011, pp. 4–10). |

| 7 | Cf. (Fought 2013). |

| 8 | This section is based in part on Sections 2.2 and 4.1 in Hinskens et al. (2022). |

| 9 | The variation in the realisation of /z/ is focused on in Van Meel et al. (2013), that in the realisation of the diphthong in Van Meel et al. (2014) and that in the contrast of /ɑ-a/ in Van Meel et al. (2019). The study of these three variable phenomena is also at the heart of Van Meel (2016). The variation in the marking of grammatical gender is discussed in Hinskens et al. (2021) and s-palatalisation in Hinskens and Ooijevaar (2023). |

| 10 | In the speech of a 20-year-old Moroccan-Dutch young man from Nijmegen. All the examples given in this paragraph (without much elaboration) are taken from the ‘Roots of Ethnolects’ recordings. |

| 11 | In this text we do not do so in order to keep the examples transparent. |

| 12 | As far as Dutch is concerned: according to e-ANS 2021: section 8.7.4, unsplit constructions are slightly more common in written language and in Flanders. |

| 13 | Here: the operation through which the preposition that is left behind (stranded) as a consequence of fronting of the R-pronoun equally moves to the front of the clause to follow its object. |

| 14 | Preposition stranding in Old English has been studied in Van Kemenade (1987, pp. 144–72). |

| 15 | |

| 16 | To wit: city; age group and language background of the speaker; language background of the addressee. |

| 17 | Viz. which preposition? does an R-word occur, yes or no? if so, then which one: (e)r-hier-daar-waar ? if no R-word occurs, is there a substitute, yes or no? if no R-word occurs and there is a substitute, is it one of these pronouns (he)t-dit-dat-wat? can the PP containing an R-pronoun be split? if splitting is possible, then does it occur, yes or no? type of split. |

| 18 | Group C is not included in any of the mixed model logistic regression analyses because the representatives of this group only spoke to speakers with the same background; their output is therefore not fully comparable with that of the other groups. |

| 19 | The analyses were carried out in several rounds. In the first round, one parameter was analyzed at a time (i.e., four analyses in total). In the second round, two parameters were analyzed at a time (i.e., six analyses, as there are six possible pairs), first only main effects, then main effects as well as all logically possible first order interaction effects. In the third round, three parameters were analyzed at a time (i.e., four analyses, as there are four possible trios), main effects only and main as well as first order interaction effects, respectively. |

| 20 | Nor, for that matter, between age group and city or between the speakers’ language background and city. |

| 21 | More aspects will be presented in Table 4 below. |

| 22 | “ge*a” indicates that the word was interrupted by the speaker and was therefore pronounced incomplete. |

| 23 | https://taalmaterialen.ivdnt.org/download/tstc-corpus-gesproken-nederlands/, (accessed on 30 December 2021). The corpus contains 900 h of recordings, almost 9 million words. The list of woordvormen (‘word forms’) has been consulted, not the lemmata. There are no CGN counts for binnenin, onderin, tegenin en tussenin (‘inside’, ‘at the bottom’, ‘against’ and ‘in between’, respectively), which also occur in the ‘Roots of Ethnolects’ conversational data. |

| 24 | In order to exclude chance fluctuations. |

| 25 | The analyses concerned the effects on the use or non-use of a substitute pronoun of the four social parameters, for all speakers or for the speakers of groups D, M and T, with one parameter each and also with two parameters (both main effect only and main and interaction effects). However, none of the models (not even those with the best fit, i.e., the lowest AICs) are interpretable. In other words, there were no significant effects to report. |

| 26 | Chi-square test (and Fisher’s exact test) assume the independence of the data. In the present data, however, most speakers produce several observations. So strictly speaking, the independence requirement is not met. |

| 27 | In the vast majority of cases, there were three representatives per subgroup; only for the 18–20-year-old Amsterdam Moroccan-Dutch and Turkish-Dutch and for the Nijmegen white Dutch with weak inter-ethnic ties of both age groups were there four representatives in the core sample. See Table 2 above. |

| 28 | When interpreting these patterns too, we must remember that the representatives of the C-group (white Dutch without strong interethnic ties) only spoke with other C-groupers. |

| 29 | In 8 of the 46 regression models, the significance of the R-pronoun effect was <0.1, but nowhere was it ≤0.05. |

| 30 | It can get even more complex. Berends 2019 reports on a study of the L1 acquisition of er as an R-pronoun in PPs (‘prepositional ER’) compared to that in ‘quantitative ER’—as in Verkoopt u boeken over ruimtevaart? lit. Sell you books about space-travel ‘Do you sell books about space travel?’ Ja, ik heb er nog vier lit. yes I have ER still four ‘Yes, I have four.’ For the seven toddlers studied, the first occurrence of prepositional ER was on average six months before that of quantitative ER (p. 30). Van Dijk and Coopmans (2013) report a similar finding for five young children from a different corpus of child speech. |

| 31 | The seven toddlers for whom Dutch was the L1 (examined by Berends 2019, pp. 29–30, 38) first used split PPs with an R-pronoun (‘non-adjacent prepositional ER’) on average three months later than non-split equivalents (‘adjacent prepositional ER’). |

References

- Auer, Peter. 2003. ‘Türkenslang‘: Ein jugendsprachlicher Ethnolekt des Deutschen und seine Transformationen. In Spracherwerb und Lebensalter. Edited by A. Häcki Buhofer. Tübingen and Basel: Francke, pp. 255–64. Available online: http://www.forum-interkultur.net/Beitraege.45.0.html?&tx_textdb_pi1[showUid]=8 (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Backus, Ad. 2015. Codewisseling tussen Turks en Nederlands: Nederturks, Turks Nederlands, of allebei tegelijk? [Codeswitching between Turkish and Dutch: Dutch Turkish, Turkish Dutch, or both at the same time?]. Praagse Perspectieven 10: 125–42. [Google Scholar]

- Beermann, Dorothee, and Lars Haellan. 2011. Preposition stranding and locative adverbs in German. In Organizing Grammar: Linguistic Studies in Honor of Henk van Riemsdijk. Edited by Hans Broekhuis, Norbert Corver, Riny Huijbregts, Ursula Kleinhenz and Jan Koster. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Alan. 1984. Language style as audience design. Language in Society 13: 145–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, Hans, and Frans Hinskens. 2014. Goed of Fout: Niet-standaard inflectie in het hedendaags Standaardnederlands. Nederlandse Taalkunde 19: 131–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, Hans, and Frans Hinskens. 2022. Coherent patterns in nonstandard inflection in modern colloquial Standard Dutch? In The Coherence of Linguistic Communities. Orderly Heterogeneity and Social Meaning. Edited by Karen Beaman and Gregory Guy. London: Routledge, pp. 221–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis, Hans, and Teun Hoekstra. 1989. Generatieve Grammatica. Dordrecht and Providence: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis, Hans. 1986. Gaps and Dummies. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Benor, Sarah Bunin. 2010. Ethnolinguistic repertoire: Shifting the analytic focus in language and ethnicity. Journal of Sociolinguistics 14: 159–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berends, Sanne. 2019. Acquiring Dutch Quantitative ER. Ph.D. thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam/LOT, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Broekhuis, Hans. 2013. Syntax of Dutch. Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brugman, Hennie, and Albert Russel. 2004. Annotating Multi-media/Multi-modal Resources with ELAN. Paper presented at the Fourth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’04), Lisbon, Portugal, May 26–28; Available online: https://aclanthology.org/L04-1285/ (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Cheshire, Jenny, Kerswill Paul, Fox Sue, and Torgersen Eivind. 2011. Contact, the feature pool and the speech community: The emergence of Multicultural London English. Journal of Sociolinguistics 15: 151–96. [Google Scholar]

- e-ANS = Electronische Algemene Nederlandse Spraakkunst. General Dutch Grammar. 2021. Available online: https://e-ans.ivdnt.org (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Eckert, Penny. 2008. Where do Ethnolects Stop? International Journal of Bilingualism 12: 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penny. 2012. Three Waves of Variation Study: The Emergence of Meaning in the Study of Sociolinguistic Variation. Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fought, Carmen. 2013. Ethnicity. In The Handbook of Language Variation and Change, 2nd ed. Edited by J. Chambers and N. Schilling. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 388–406. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1976. Anti-Languages. American Anthropologist New Series 78: 570–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinskens, Frans. 2011. Emerging Moroccan and Turkish varieties of Dutch: Ethnolects or ethnic styles? In Ethnic Styles of Speaking in European Metropolitan Areas. Edited by Friederike Kern and Margret Seltin. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: Benjamins, pp. 103–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hinskens, Frans. 2019. Ethnolects: Where language contact, language acquisition and dialect variation meet. In Proceedings of the 7th Ιnternational Conference on Modern Greek Dialects and Linguistic Theory. Edited by Ioanna Kappa and Marina Tzakosta. Patras: University of Patras, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hinskens, Frans, and Etske Ooijevaar. 2023. Social patterns in s-palatalisation in Moroccan and Turkish ethnolectal Dutch. One half of a sociolinguistic study. In The continuity of linguistic change: Essays in Honour of Juan Andrés-Villena. Edited by Matilde Vida Castro and Antonio Ávila-Muñoz. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Hinskens, Frans, Khalid Mourigh, and Pieter Muysken. 2022. The Netherlands Urban contact dialects. In Urban Contact Dialects and Language Change. Edited by Paul Kerswill and Heike Wiese. London: Routledge, pp. 223–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hinskens, Frans, Roeland van Hout, Pieter Muysken, and Ariën van Wijngaarden. 2021. Variation and change in grammatical gender marking: The case of Dutch ethnolects. Linguistics 59: 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Michol F., and James Walker. 2010. Ethnolects and the city: Ethnic orientation and linguistic variation in Toronto English. Language Variation and Change 22: 37–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indefrey, Peter, Hülya Sahin, and Marianne Gullberg. 2015. The expression of spatial relationships in Turkish–Dutch bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20: 473–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, Friederike. 2011. Introduction. In Ethnic Styles of Speaking in European Metropolitan Areas. Edited by Friederike Kern and Margret Selting. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kossmann, Marten. 2012. Berber. In The Afroasiatic Languages. Edited by Zygmunt Frajzyngier and Erin Shay. Cambridg: Cambridge University Press, pp. 18–101. [Google Scholar]

- Muysken, Pieter. 2013. Ethnolects of Dutch. In Language and Space: Dutch. Edited by Frans Hinskens and Johan Taeldeman. Belin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 739–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nortier, Jacomine, and Margreet Dorleijn. 2008. A Moroccan accent in Dutch: A sociocultural style1 restricted to the Moroccan community? International Journal of Bilingualism 12: 125–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruette, Tom, and Freek Van de Velde. 2013. Moroccorp: Tien miljoen woorden uit twee Marokkaans-Nederlandse chatkanalen [Moroccorp: Ten million words from two Moroccan-Dutch chat-channels]. Lexikos 23: 456–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]