1. Introduction

Exchanging signals through facial expressions of emotions is a crucial part of human social communications. We read others’ emotions from their facial expressions relatively effortlessly and accurately (

Ekman 1984). Most studies on the judgment of facial expressions, however, primarily utilized prototypical, high-intensity expressions (

Matsumoto and Hwang 2014), and comparatively little is known about the perception of neutral expressions. A neutral expression can be defined as “absence of emotion” (

Sato and Yoshikawa 2010), but simply recognizing an expression as “neutral” appears to be a complex process, and humans are not very good at it.

Lewinski (

2015) found that humans are generally reluctant to label any expressions as “neutral” while automated facial coding software has no such reluctance. Thus, humans judge a face as showing neutral expression much less frequently than the software. The reason for this phenomenon is not yet clear, but our firm intention to read others’ emotions likely plays a large part. Contextual information accompanying neutral expressions (e.g., written scenarios or emotion labels) are readily processed and provide meaning to the expression (

Carrera-Levillain and Fernandez-Dols 1994;

Fernández-Dols et al. 2008). The expressor’s disposition can also be reflected in neutral expressions. For example, the neutral facial expression of individuals with a hostile disposition is perceived as angrier than the similar expression of non-hostile individuals (

Malatesta et al. 1987). Brain activation studies back up the notion that we spend a significant amount of cognitive effort to read emotional content from neutral faces in a social context. Although neutral and emotional faces activate some common neural pathways (

Haxby et al. 2000), some unique activations for neutral face processing have been found. Those activations are related to integrating signals from multiple sensory modalities (e.g., integrating emotional cues coming from voice and face) and processing ambiguous stimuli (

Carvajal et al. 2013).

In regard to displaying neutral expressions, it is questionable whether portraying a truly neutral (absent in emotion) state is possible. Facial expressions can be evoked unconsciously, demonstrated in the unconscious mimicking of a smile (

Arias et al. 2018;

Dimberg et al. 2000). Thus, our internal state can be easily displayed on our faces even if we intend to show a neutral expression. The present research focuses on such subtle expressions (or altered facial appearance) hidden behind “consciously portrayed” neutral expressions. It is specifically interested in what can elicit such changes and whether they are accurately perceived.

The present study is based on research by

Lõhmus et al. (

2009). In their study, female models were asked to pose neutral expressions while wearing attractive, unattractive, and comfortable clothes, and their faces (but not clothes) were photographed. Those facial images were then rated for attractiveness by male participants. It was revealed that the neutral expressions portrayed while wearing attractive clothing were perceived as more attractive than those portrayed with unattractive clothing. It is argued that the attractive clothing altered the models’ internal state, most likely by eliciting confidence, and influenced the appearance of their neutral expressions. The male observers then interpreted the change of facial appearance as facial attractiveness.

Lõhmus et al. (

2009) asked the female models to rate their self-confidence and comfort of being photographed after the pictures were taken. It was found that the perceivers detected the models’ confidence and comfort from the facial expression and rated this as attractiveness. This is taken as evidence that confidence elicited by the attractive clothing altered the models’ facial appearances.

The present research aims to replicate the study by

Lõhmus et al. (

2009). Instead of using clothes to alter photographic models’ internal state, it used personal names (e.g., given name, nickname, and formal title) others use to address them. Our names are a crucial aspect of our identity (

Allport 1937) and self-concept (

Bugental and Zelen 1950), and whether or not individuals like their name can affect self-esteem (

Gebauer et al. 2008). Names also work as a social label, influencing how others evaluate us (

Mehrabian 1997,

2001). People associate names’ meaning, sound, and spelling with the owners’ dispositions. It is reported that a person with an easily pronounceable name is perceived as more likable than a person with a difficult name (

Laham et al. 2012). Chinese names written with complex characters tend to be judged as belonging to males, and the bearers of such names are perceived as untrustworthy (

Du et al. 2021). The meaning of names can also influence the evaluation of owners’ disposition. People whose names and occupations match (e.g., Mr. Judge being a judge) tend to be evaluated as being more suited for the job than people with unrelated names to their jobs (

Guéguen and Pascual 2011). This is a phenomenon commonly called nominative determinism. Therefore, names must be strongly associated with individuals’ self-esteem and confidence and likely to alter facial appearances. There is evidence that names can even permanently change people’s facial structures. Consequently, it is possible to guess strangers’ names from their faces with an above chance level of accuracy (

Zwebner et al. 2017). However, the present study focuses on the temporary increase in self-esteem or self-confidence brought by envisaging being addressed by a specific name.

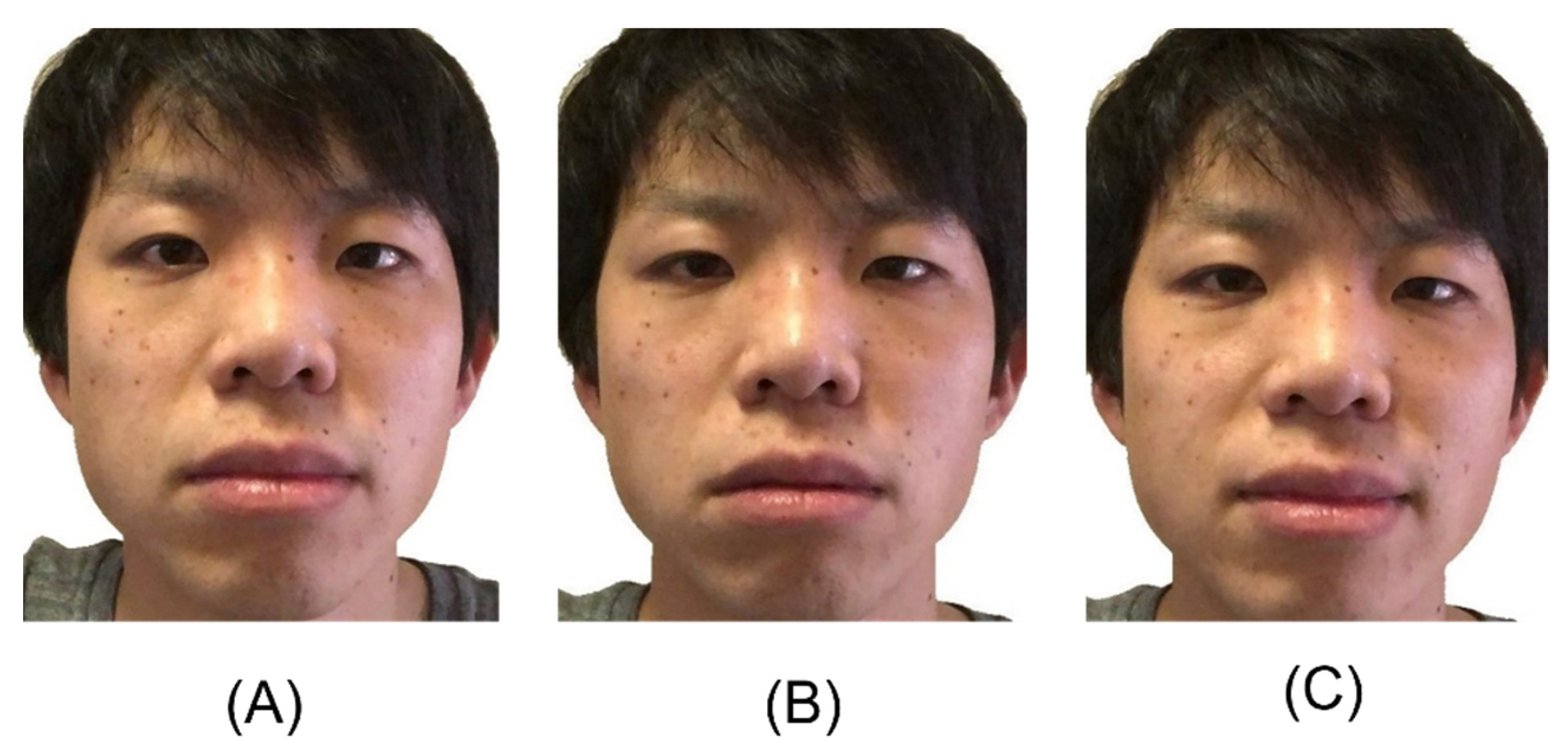

The present research collected images of neutral facial expressions from 21 Japanese models and asked Japanese participants to rate their attractiveness. Each model provided three images taken while envisaging the following situations: being addressed by a name they like (positive condition), being addressed by a name they dislike (negative condition), and being addressed by their actual name with titles (neutral condition). The way people address us can directly affect our life experiences and self-esteem.

Gebauer et al. (

2008) found that the extent to which individuals like their names strongly correlates with their self-esteem. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the models’ self-esteem in the present study would increase when they are addressed in ways they like, while it will decrease when others use names they dislike. The resulting change of self-esteem is likely to make itself apparent on the blank canvas of the neutral faces, which may translate to different levels of perceived attractiveness. One shortcoming of the study by

Lõhmus et al. (

2009) is that they did not confirm if the facial images used in the experiment were actually perceived as displaying neutral expressions (unemotional). The present research conducted a test to assure the stimulus quality to address this problem.

The “names” in the present research include all kinds of names: surnames and given names with or without titles, nicknames, or any nouns used in a place name, such as occupational titles and ranks in an organization (e.g., “governor” or “sergeant”). In the present studies a surname with a title was used in the neutral condition which served as a controlled condition; and the names in other conditions could be any of those above. The most common way to address others in public for Japanese is to add the title “san” after the surname. A person called “Hanako Yamada”, therefore, is most commonly addressed as “Yamada san”, which is equivalent to Mr. (Mrs., Miss) Yamada. This “Surname san” format was used for the neutral condition of the current studies.

Regarding nicknames, the most common ones for English names are shortened versions of given names (e.g., Tom for Thomas). Altering the end of the names with y is also common (e.g., Tommy). Japanese often create nicknames by adding a prefix or suffix to the given or family names. Importantly, a Japanese name can be associated with many more varieties of nicknames than an English name. Possible nicknames for the forementioned “Hanako Yamada” would be “Ohana”, “Hana-chan (chan is a suffix indicating small, thus sounds affectionate)”, “Hana-hana”, “Yakkun”, “Yama-chan”, “Yama-gon”, and many others (

Kiyomi 2010). Of course, some nicknames are unrelated to real names, for example, those based on the person’s physical appearance. There is no evidence, at least to the authors’ knowledge, showing the association between types of nicknames and their evaluations in Japanese. The same name can be evaluated positively or negatively depending on the person. Therefore, the present study did not control the imagined names for the positive and negative conditions.

The present research findings will provide significant implications for 1) the importance of perceiving hidden confidence in a collectivistic culture such as Japan and 2) how the name-driven confidence expression influences interpersonal relationships. Japan belongs to a collectivistic cultural group, in which interpersonal harmony is prioritized over the autonomy of individuals (

Markus and Kitayama 1991). Such a culture requires people to behave humbly to others and encourages them to suppress expressions of true feelings within a social group (

Ekman and Friesen 1975;

Matsumoto and Ekman 1989). In such a society, the experience of self-confidence tends to be suppressed. Thus, the experimental condition of the current study, confidence being hidden behind the neutral expression, is a very realistic situation for people in a collectivistic culture, and it is meaningful to investigate whether observers can perceive such hidden emotion accurately.

It is also important that the present study examined the emotion triggered by names, as an important aspect of interpersonal interactions. One’s emotional expressions influence not only his/her own cognitive processes but also observers’ information processing and reactional behaviors (

Keltner and Haidt 1999). For example, when one shows a happy expression, observers would infer that the communication is going well and decide to stay on course (

Van Kleef 2009). The influence of emotional expressions on observers is explained by the Emotion As Social Information (EASI) model. How to address each other in a conversation reflects relational proximity between the communication participants. Addressing someone inappropriately, either too casually or too formally, could disrupt the interpersonal relationship. Therefore, it is highly likely that being called by a specific name triggers an emotional response (which can be subtle), and observers can receive the signal. The results of the present study, therefore, can be regarded as an example of the EASI model in communicating with someone when using specific names.

4. General Discussion

The present research investigated if individuals’ internal state can alter the appearance of neutral expression and whether or not observers can perceive the subtle appearance change. Envisaging of being addressed by particular names was used to alter individuals’ internal states, especially the levels of self-esteem and confidence. Numerous studies have reported that humans tend not to perceive neutral expressions as simply an absence of emotion. They are keen to read some emotional components from them, often referring to contextual information (

Carrera-Levillain and Fernandez-Dols 1994;

Fernández-Dols et al. 2008;

Lewinski 2015;

Malatesta et al. 1987). This tendency goes hand in hand with our sensitivity to subtle emotional cues (

Matsumoto and Hwang 2014), resulting in varied interpretations of neutral expressions. The expressions used in the present study were perceived as neutral at the quality test. However, the participants readily processed slight differences across three images of the same model, replicating the study by

Lõhmus et al. (

2009).

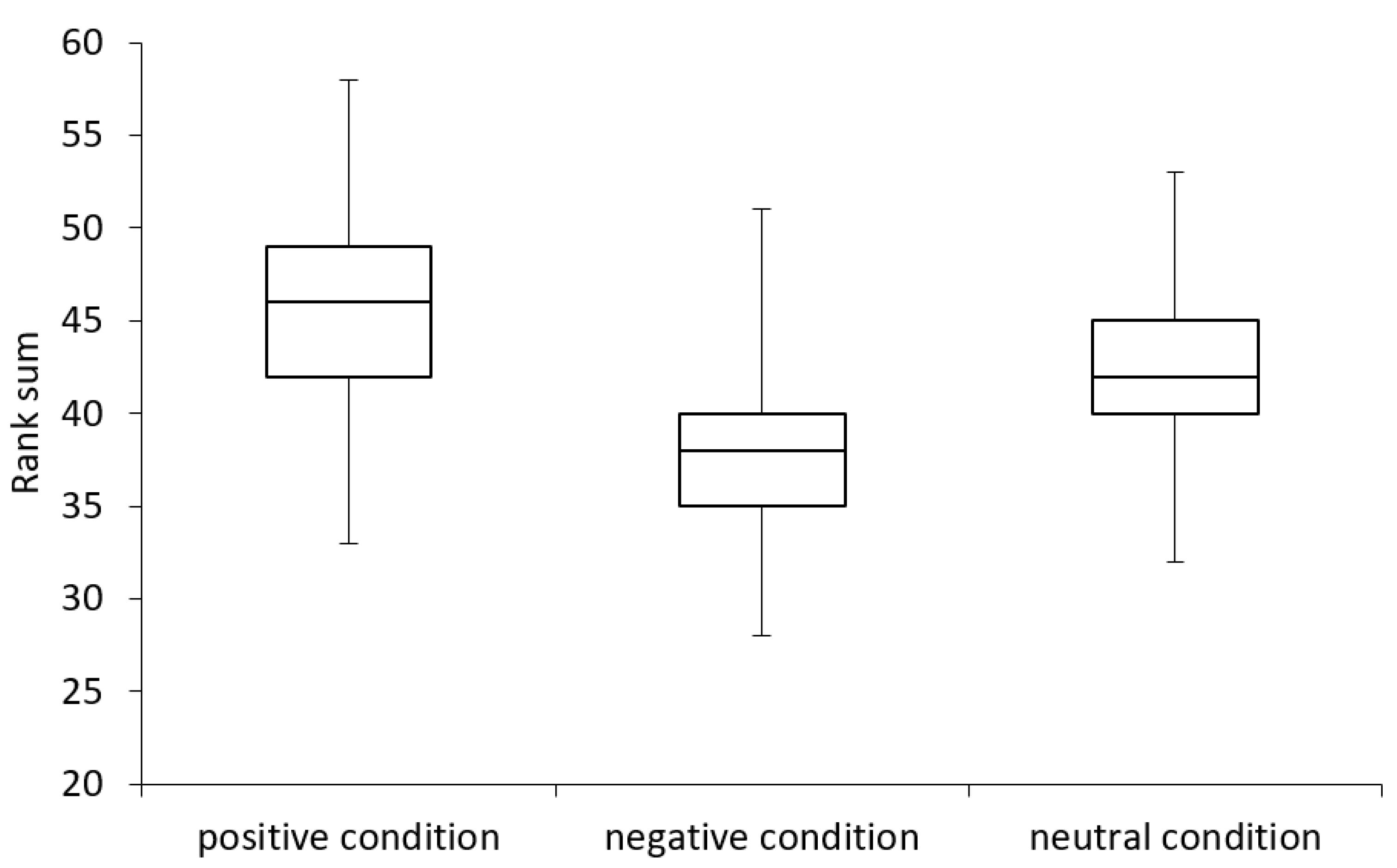

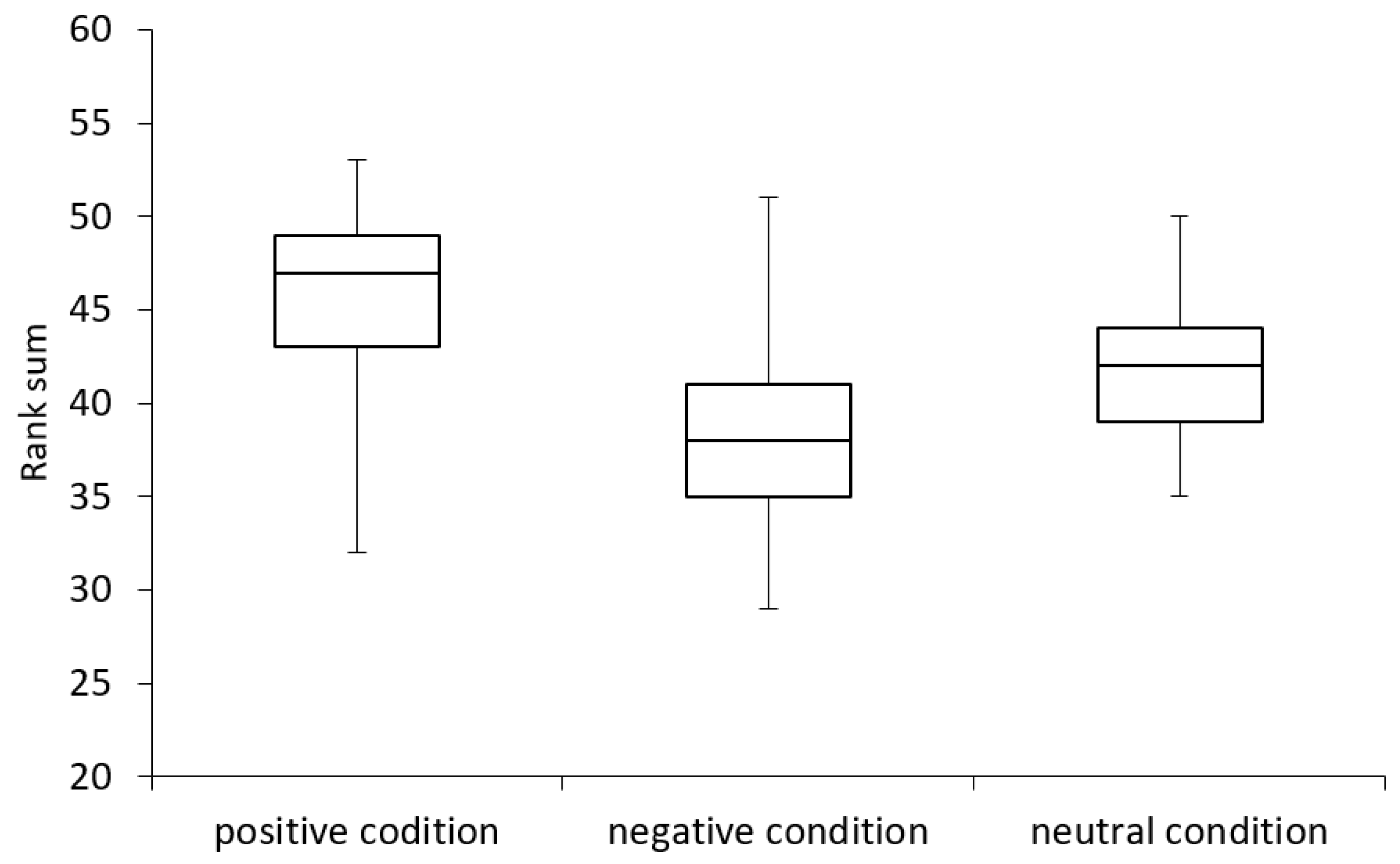

The present study results demonstrated that the imagination of being addressed by specific names could alter our internal states. The attractiveness/confidence rank order was higher for the images associated with preferred names than with titled surnames. The lowest rank order was given to images associated with disliked names. This pattern indicates that the models’ confidence increased when imagining being addressed by names they like compared to being addressed by titled surnames. On the contrary, the confidence level decreased from the neutral condition when they imagined being addressed by disliked names. There was a very high correlation between the attractiveness rank in Study 1 and the confidence rank in Study 2. It shows that facial changes brought by the models’ raised confidence translated to increased attractiveness, and the observers readily perceived it.

Lõhmus et al. (

2009) only used female faces, and their observers were all males, and therefore the concept of attractiveness in their study was associated with mate selection. Indeed, in the context of mate selection, it is reported that individuals’ level of confidence and their perceived physical attractiveness by another sex are strongly connected (

Brand et al. 2012;

Roberts et al. 2009). In the present study, however, the positive condition images were perceived as more attractive than other images regardless of the sex of the observers and models. It suggests that confidence-related attractiveness is not limited to sexual context, and instead, it is perceived as a generally positive facial quality.

While

Lõhmus et al. (

2009) found a correlation between the models’ self-confidence and perceived attractiveness for the images with attractive clothing, this trend was absent in the present study. This discrepancy is most likely due to the types of self-confidence being measured. The present research measured the models’ general confidence level while

Lõhmus et al. (

2009) asked their models to report confidence about being photographed. People’s consistent disposition, such as a general confidence level, may influence their facial structure, as

Malatesta et al. (

1987) report that neutral expressions of hostile people look rather angry. Therefore, the general confidence level may create a difference in perceived attractiveness across models but may not greatly influence the within-individual change in appearance. The changes within individuals may be more strongly associated with temporarily altered internal states. As evidence, the present study found moderate (albeit statistically insignificant) relationships between the rank order of the positive images and the models’ comfort level while taking their photographs.

The present research demonstrated that being addressed by the preferred names is associated with positive self-esteem. Being accepted by others is a significant factor in raising self-esteem (

Leary et al. 1995). When others call us by the name we like, we experience a sense of acceptance and friendliness towards others. Such experience would raise our self-esteem and self-evaluation (

Gebauer et al. 2008). In the present data, the models’ level of confidence in themselves and the extent to which they like their names in the positive condition were correlated,

r (20) = 56,

p = 0.009, showing that the models with higher self-esteem liked their positive names (or the self which is addressed by those names) more.

In contrast, negative psychological effects are brought by disliked names. Interpersonal communications involving negative name calling elicit a sense of rejection and alienation to the person concerned, reducing his/her self-esteem (

Leary et al. 1995). An everyday example of such negative interpersonal communication is bullying. Bullied individuals often suffer from low self-esteem (

Hawker and Boulton 2000), and calling the victims using non-preferred nicknames is an extremely common bullying strategy among children (

Crozier and Dimmock 1999). Names are a crucial part of self-concept (

Bugental and Zelen 1950); thus, the experience of being called by disliked names cultivates negative self-concepts. Bullying victims often ignore the callers who use nasty names to eliminate such a negative self-concept (

Crozier and Skliopidou 2002). The present research showed that simply imagining being called by negative names affects people’s internal state so strongly that it alters the facial appearances of consciously portrayed neutral expressions. This demonstrates the significance of names in our self-concept and self-esteem.

Importantly, the impact of the names on our feelings manifests only when the names are associated with actual experiences. In the present studies, the effect of name conditions significantly diminished for images unrelated to the models’ actual experiences. This confirms that the impact of names is associated with the memory of situations involving them, rather than simply caused by the characteristics (e.g., acoustic/visual characteristics or literal meaning) of the names themselves. It also supports the argument that the change in facial appearance is related to self-esteem or confidence because real experience is essential to influence those psychological elements.

The name-driven facial changes demonstrated in the present study are, in real-life communication, signals indicating whether the relational distance between the communicators is appropriate. According to the EASI model, the observers of emotional expressions infer the expressor’s intention and decide their next move (

Van Kleef 2009). Detecting expression changes triggered by names would help the observers steer the communication in a better direction. Addressing someone in a socially appropriate way, for example, addressing someone older in an honorific manner, does not necessarily result in desirable communications (e.g., when the person being addressed wants more friendly communication). The ability to detect the subtle expressions demonstrated in the present study is, therefore, crucial to achieve effective communication. As mentioned in the introduction, Japanese culture is collectivistic and people tend to hide their true feelings in public (

Ekman and Friesen 1975). This means that negative feelings associated with being addressed by unpreferable names are likely to be shown subtly, as in the stimuli of the present study, and Japanese people might be getting used to reading such subtle expressions. Although a similar finding is reported by

Lõhmus et al. (

2009) with Western participants, the ability to read subtle expressions may differ depending on the culture. Thus, cross-cultural comparison of the ability is necessary to determine, for example, whether it is culturally variant or more innately constrained.

The observers’ information processing described in the EASI model is synonymous with social cognition, often defined as information processing regarding other individuals’ dispositions and intentions (

Brothers 1990). Accurate readings of others’ facial expressions lead to a better understanding of their dispositions and intentions, hence, a higher social cognition ability. For example, facial expression recognition ability and the extent of Theory of Mind are likely to be correlated (

Bora et al. 2005;

Brüne 2005). The stimuli with subtle expressions would enable very sensitive assessments of emotion recognition ability. Therefore, a similar study to the current research can be conducted in the context of social cognition measurement.

Regarding subtle emotional expressions, focusing on the expressors might also be valuable. Although the observers of the present study readily perceived the subtle expressions, the level of emotion concealment must have varied across models. It would be interesting to investigate individual characteristics related to the ability to conceal emotion. Personality traits such as extroversion are strong candidates to influence such ability. In addition, individuals’ level of obedience to the cultural norm, whether to express or hide particular emotions in a culturally appropriate manner (

Matsumoto and Ekman 1989), may play a significant part. This line of research will help further reveal the mechanism of human motivation for emotional expressions.

Finally, we discuss the limitations and cultural implications of the present research. The stimuli in the research were gathered online; thus, the photographic environment and quality were not strictly controlled. Contents of the imagined situations were not clear either. Although the results imply that the models’ imagination involved their episodic memories, this cannot be concluded with certainty unless the imagined contents for all conditions are recorded.

Similarly, experimental control might have been insufficient since the current studies were conducted online. The devices used to view the faces and the stimulus viewing time must have varied across participants. Fortunately, the current studies managed to secure relatively large samples, and there is no clear indication that insufficient control affected the results. No participant answered randomly or inappropriately, so it is reasonable to assume that all participants viewed the images carefully. On the variation in viewing time, the past research reports that attractiveness assessment is not significantly influenced by the face-viewing time once the duration reaches over 500 ms (

Saegusa and Watanabe 2016;

Willis and Todorov 2006). A time of 500 ms should not have been enough to complete the present task (ordering three images according to attractiveness/confidence), so most participants must have taken longer than that on each trial. Thus, the variation in viewing time is less likely to have affected the results. Nevertheless, it is preferable to repeat the studies in more controlled environments. Additionally, the rank order task can be replaced with an attractive/confidence rating task. The current study used the rank order to match the procedure used by

Lõhmus et al. (

2009) but using an interval scale to measure attractiveness/confidence level would be more precise, and this should be considered for a future study.

How people address each other is strongly influenced by culture and language. In East Asia, for example, people commonly address others using words describing relationships or roles rather than using actual names. In addition, the use of given names, which is common in most relationships in Western countries, is limited to very close relationships in East Asia (

Mogi 2002). Culture and language determine the appropriate ways to address people in particular situations. How nicknames are created may also vary across cultures. Some cultures may create nicknames based on the sound of real names, while other cultures may do so based on people’s disposition or physical characteristics. These cultural variations are likely to be reflected in the extent to which names influence our internal states.

The influence of culture is also strongly evident for perception and display styles of facial expressions. Although expression styles across cultures share huge similarities, especially for basic emotions (

Ekman 1984), cultural variations are often reported (see

Cordaro et al. 2018).

Elfenbein and Ambady (

2002) argue that culturally specific display styles can be very subtle but accurately perceived by people of the same cultural group. Therefore, the attractiveness or confidence of the current stimuli (Japanese faces) may be judged differently by non-Japanese observers. Cross-cultural studies investigating neutral face perception are still rare; therefore, it will be meaningful to examine the interaction among names, self-esteem, and neutral expression across different cultures in the future.