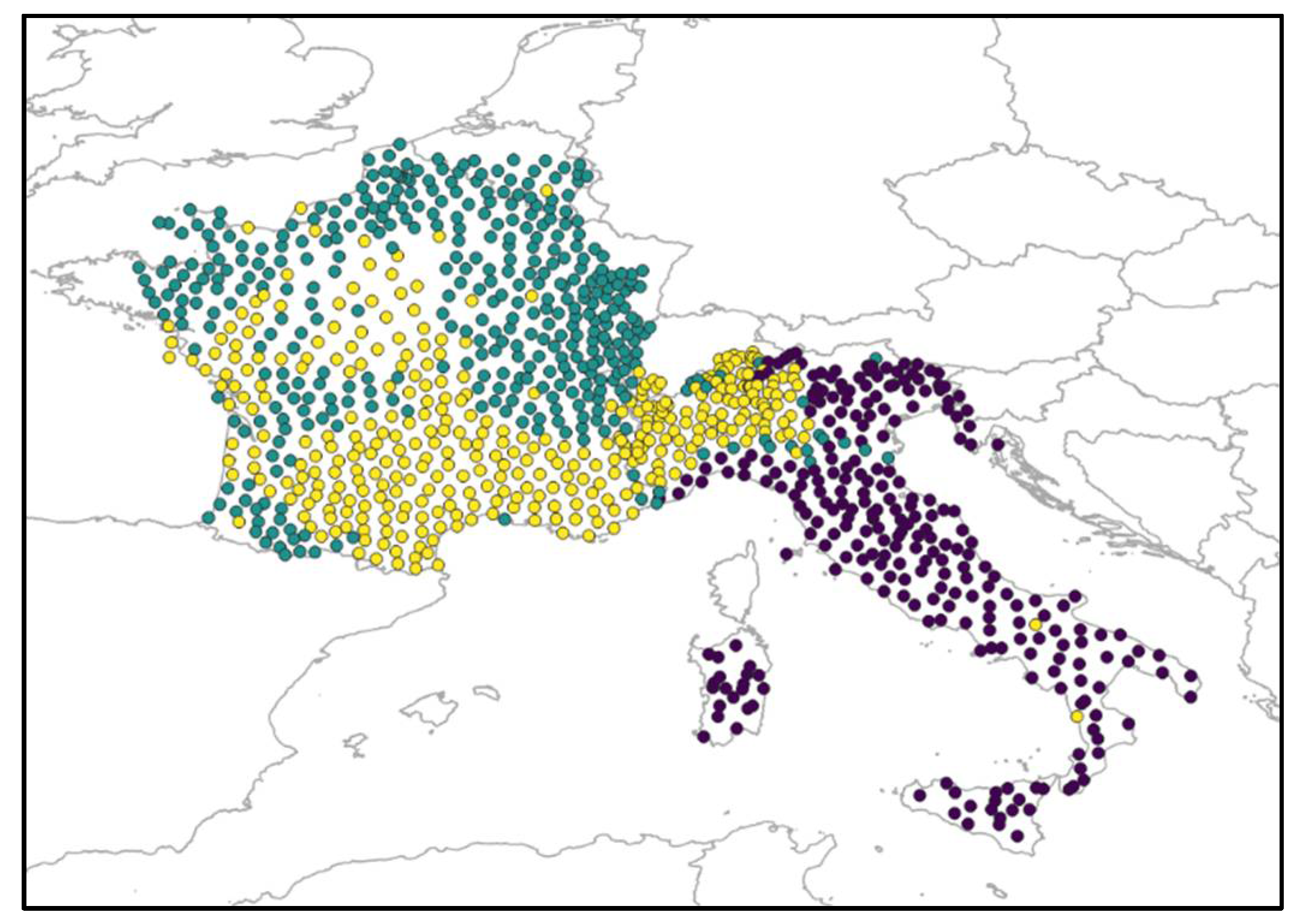

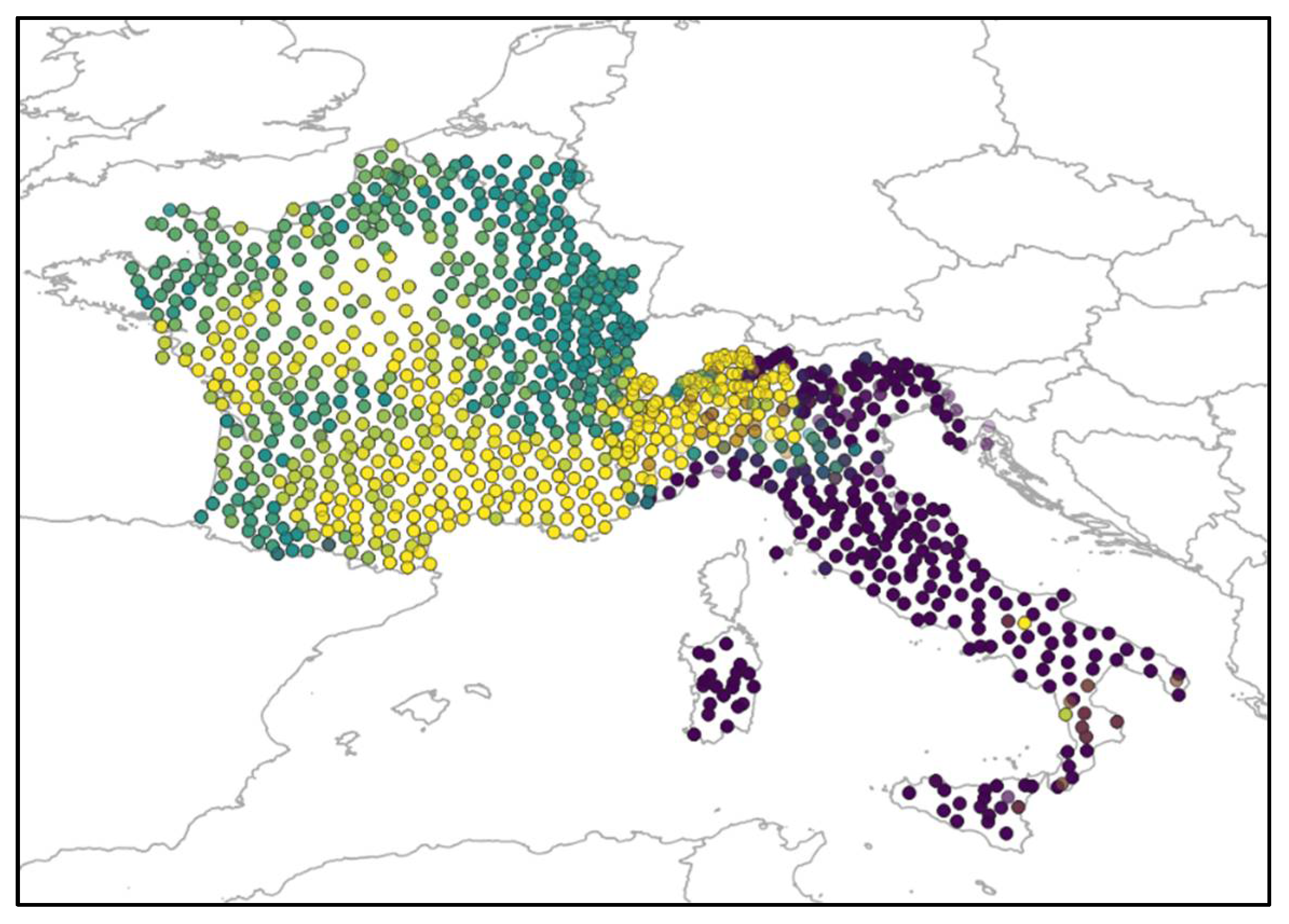

3.1. N1 (AIS)

As mentioned in

Section 2, the sample of northern Italo-Romance dialects exhibiting discontinuous negation is quite narrow. A second issue with the AIS dataset (in fact, an issue with all linguistic atlases) is collinearity, i.e., too many tokens are elicited by using the same input sentence, and therefore exhibit the same syntactic properties. For instance, all sentences containing a certain NPI are also subjunctive clauses and vice versa. In this condition, logistic regression provides no reliable result, because the algorithm cannot dissociate the two factors at play.

To avoid collinearity (or at least limit its effect), I decided to test two separate subsets of data, as shown in

Table 4: (a) indicative clauses containing NPIs and (b) all clauses containing no NPIs. In the remaining clauses, in fact, the presence/absence of N1 might be conditioned either by the presence of an NPI or by a nonveridical operator, such as a modal verb.

For each subset of data, I tested mixed models containing both geolinguistic and grammatical factors to find out whether region alone accounted for the data or mixed models including external and grammatical factors have better predictive power. I found that region is always a significant factor, as expected in a dataset containing data from tightly related languages. For this reason, the results concerning the factor region will be systematically omitted from now on. In general, however, I found that region is seldom sufficient to account for the distribution of N1 and N2, and mixed models including syntactic factors usually fit the data best. This preliminary conclusion confirms the results of previous statistical analyses of microvariation, such as those of

van Craenenbroeck et al. (

2019).

First of all, I tested whether the factors region and clause are significant predictors of the distribution of N1 in the subset of tokens that do not contain NPIs. Rbrul found that both factors are statistically significant (region

p = 2.3 × 10

−249; clause

p = 0.00053). The weight of each value of clause is given in

Table 5. All of the following tables are organized in the same way: for each group of factors, they report the number of tokens (i.e., the number of negative clauses per type) and the relative frequency of N1 in each type of clause (the number of clauses in which N1 is present divided by the number of clauses with available data), and the last column reports an index ranging from 0 and 1 indicating the probability that N1 will occur in a given type of sentence. Notice that probability may differ from frequency, because the former is calculated by taking into account all types of factors, e.g., both clause and region. By excluding and including factors, Rbrul tests different scenarios until it finds the model that fits the data best (the winning model can be the one without factors) and eventually weights the single factors in the distribution of the dependent variable.

Table 5 shows that (embedded) subjunctive clauses are the environment in which N1 is most probably found, whereas imperatives are the context with the lowest incidence of N1.

Imperatives, however, deserve further attention (and probably a separate analysis), because there is a great deal of variation in the ways that negative imperatives are syntactically encoded. In most dialects, negative imperatives are not obtained by adding a negative marker to the positive imperative form, but are instead expressed by a periphrasis with the verb “stay” (e.g., Ven.

No sta partir, “do not leave”, lit. “not stay to leave”), a subjunctive form, or an infinitive.

Zanuttini (

1997, pp. 105–7) claimed that suppletive imperatives are found in dialects without N2, while in dialects in which N2 is available, negative and positive imperatives may have the same form (see

Garzonio and Poletto (

2018, p. 5) for apparent counterexamples and discussion). At present, I cannot verify whether Zanuttini’s generalization is confirmed or not by the AIS/ALF dataset because the data on imperatives still need to be coded in our spreadsheet. However, without a clear indication about the incidence of suppletive imperatives, it seems to me that the comparison between imperatives vs. other clauses is not trustworthy because other orthogonal factors are probably at play.

Another issue with imperatives is that they cannot exhibit subject clitics, which—according to previous corpus studies on French—may play a role in the retention of N1 (

Ashby 1981). Northern Italo-Romance, as well as northern Occitan, is a promising area to investigate the relationship between subject clitics and negation. In these areas, subject clitics are mandatory (even if a DP subject occurs), but inventories of subject clitics are often defective (

Poletto 2000;

see Pescarini (

2019) for a quantitative overview). In principle, we can therefore verify whether the probability of finding N1 increases or decreases in the contexts and dialects in which subject clitics are missing. This kind of study, however, requires a painstaking reconstruction of each clitic system, a goal that goes beyond the limits of the present paper. I therefore limited myself to checking how N1 varies depending on person (and number), a factor that might be in turn related, albeit indirectly, to the syntax of clitics. I found that person is a significant factor in a model containing the factors region, clause, and person (region

p = 7.7 × 10

−169; person

p = 0.0066; clause is not significant). The data in

Table 6 therefore provide some first indications regarding the interaction between subject clitics and N1: the frequency of N1 is lower at the 2/3sg and higher at the 3pl and 1sg (sentences containing 1pl subjects were omitted, as 1pl clitics are easily mistaken for N1). The data in

Table 6 point toward various avenues of research. Phonologically, 1sg and 3pl clitics in many dialects have a vocalic formative that provides a nucleus on which the N1 marker -

n can syllabify. A higher incidence of N1 may therefore have a morphophonological explanation. Alternatively, one can argue that the ranking in

Table 6 correlates with syntactic factors, as vocalic clitics often occupy a higher syntactic position than other clitics (

Poletto 2000) and therefore tend to precede N1, whereas the other clitics occur between N1 and V. As previously mentioned, these issues will remain open until a fine-grained analysis of subject clitics in the AIS datapoints is carried out.

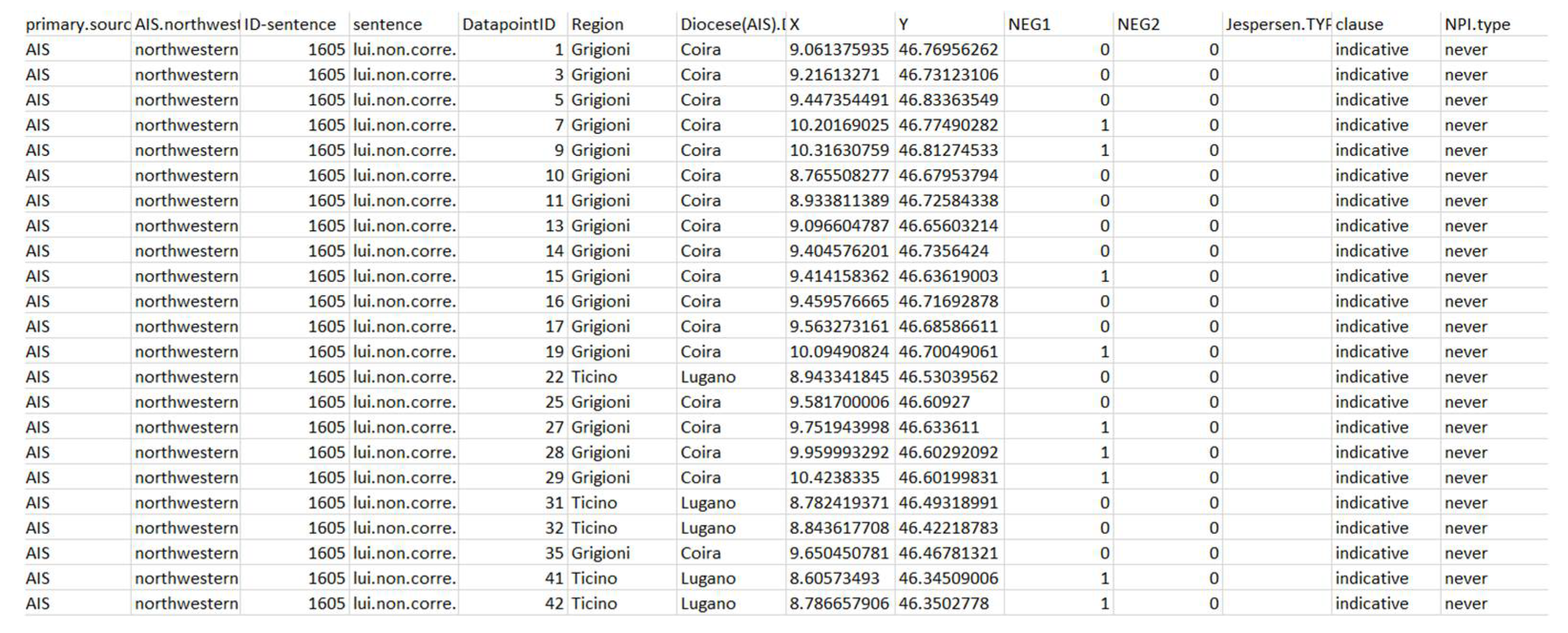

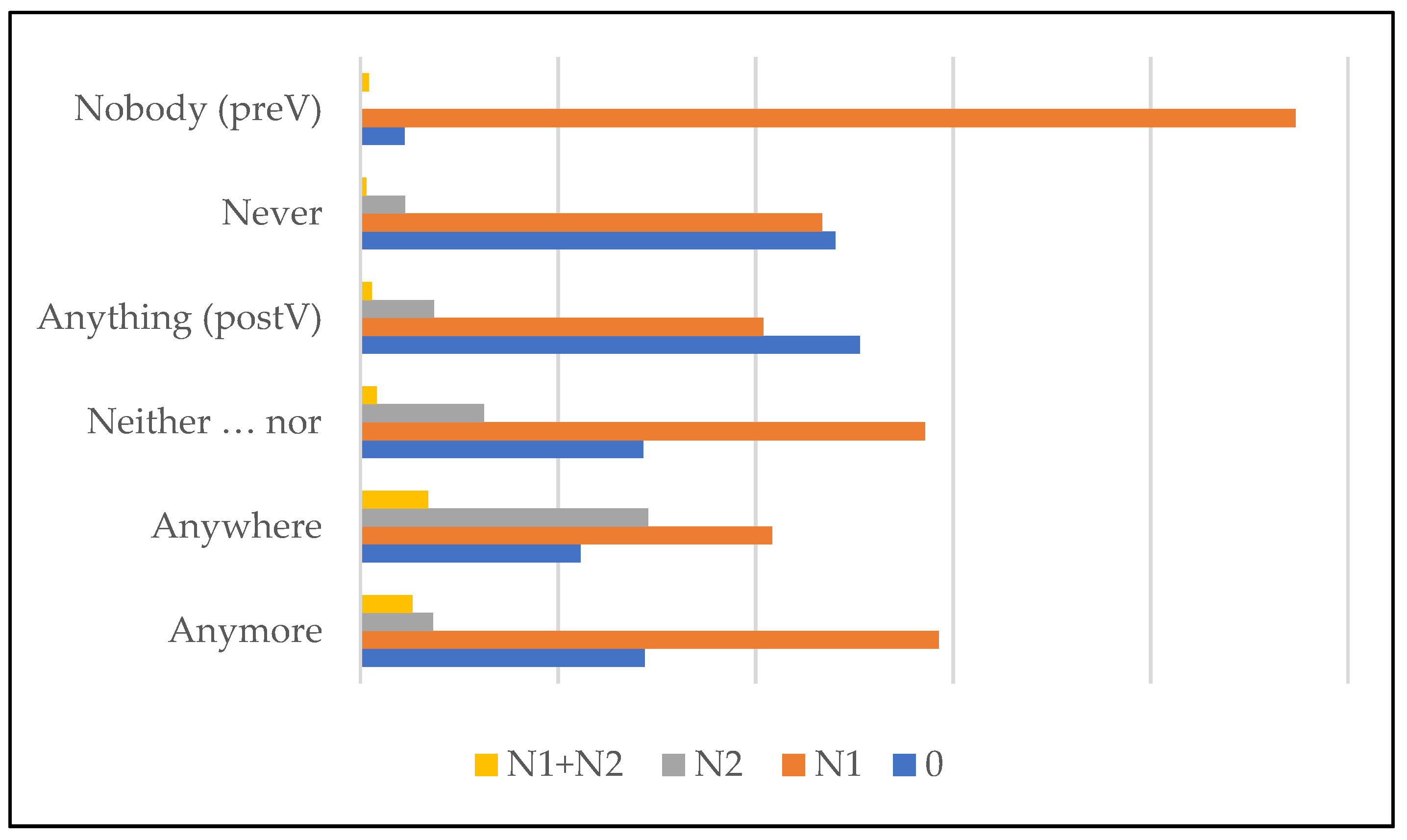

I then tested how NPIs affect the distribution of N1 in the AIS dataset. The data in

Table 7 show the frequency and probability of N1 with respect to various classes of NPIs and in negative sentences without NPIs. Consider that the following probability rates were obtained in a model containing the factors region and NPI type; only the subset of indicative clauses was taken into consideration to avoid collinearity (

Table 4). Both factors (region and NPI type) proved significant.

If we take negative sentences lacking NPIs as the baseline, we find that, on average, NPIs tend to favor the retention of N1, although the difference between clauses containing and not containing NPIs is quite narrow. N1 is most likely to occur when an NPI is embedded in an adjunct prepositional phrase, e.g., in nessun luogo, “in any place”.

The syntax of the adverb “yet”, which seems to disfavor N1, needs elaboration, because in most Italo-Romance dialects, it corresponds to a polysemous adverb (It. ancora) that conveys two aspectual values, repetitive (“again”) and continuative (“up till now”), that are not sensitive to polarity. Analogously, most Italo-Romance dialects do not display a polarity-sensitive alternation of the kind “still”/”yet”, except for 25 datapoints that exhibit negative adverbs, e.g., [ɲaˈmɔ], [ɲaŋˈkora], which are negative counterparts of positive adverbs [ˈmɔ] “now” and [aŋˈkora] “again”. These negative adverbs occur predominantly in dialects without N1 and might be therefore analyzed as n-words (like Eng. nothing, never, etc.) that do not need to be licensed by N1. This explains why the occurrence of N1 in clauses containing “yet” is less frequent/probable than in other negative clauses.

After removing sentences containing “yet”, I grouped the values “anymore”, “anything”, “never”, and “anywhere” (PP) together, thereby obtaining a binary factor of presence vs. absence of NPI, which proved not to be statistically significant in a model containing the factors region (p = 2.1 × 10−170) and NPI type (as above, the model was tested on the subset of indicative clauses). This amounts to saying that the presence of generic NPIs is not predictive of the distribution of N1 in the AIS dataset. Specific NPIs, on the contrary, are good predictors of the behavior of N1, which is more likely retained when the NPI is embedded in an adjunct PP.

Before addressing N2 (

Section 3.2), the remainder of this section elaborates on the occurrence of N1 in sentences with N2 doubling, i.e., sentences in which N2 co-occurs with an NPI. In languages with discontinuous negation, N2 usually triggers a double-negative reading when it co-occurs with another NPI, e.g., Fr.

Il n’a pas rien vu, “It is not the case that he saw nothing”. However, in a few AIS datapoints, we find examples of N2 + NPI combinations that, instead of triggering a double negation effect, yield a pattern of bona fide negative concord. Theoretically, this may mean that in these varieties, N2 has become a fully-fledged clausal negator that is able to license NPIs (a property that normally characterizes N1-type negators, according to the preliminary typology given at the beginning of

Section 1). We may therefore hypothesize that N2 doubling is allowed only if N1 is missing. In fact, however, I found a number of sentences in which both N1 and N2 co-occurred with an NPI, mostly in examples in which the NPI was the argument of a preposition (as in the case of expressions such as It.

in nessun luogo, “anywhere”, literally “in no place”) and in sentences containing a “neither … nor” coordination. If PPs and coordinations are removed, the number of cases of N2 doubling drops to six. N2 doubling therefore proved to be a significant factor in the distribution of N1 (along with region;

p = 0.00021). As previously mentioned, the frequency and probability of N1 were found to drop in sentences featuring N2 doubling, as shown in

Table 8, although it is worth recalling that N1 is more likely to be found if the NPI is embedded in an adjunct PP.

3.3. Interim Conclusion (AIS)

Mixed models including grammatical and geographical factors often perform better than models containing only geographical factors. As for N1, clause, person, and NPI type, all proved significant, but I was not able to model all grammatical factors together due to collinearity.

As for clause, (embedded) subjunctive clauses proved to be the environment in which N1 is more likely retained, but no clear distinction emerged between, e.g., veridical and non-veridical contexts. The range of probability, in general, is quite narrow, and the overall ranking of values is difficult to interpret under current analyses of negation marking. Conversely, I noticed that nonveridical clauses, such as if clauses, questions, and embedded subjunctive clauses, are the contexts in which N2 occurs less frequently.

Person seems to play a role in the distribution of N1, and I briefly commented on the possible morphophonological and syntactic reasons that might link person and negation marking in dialects with subject clitics. The role of subject clitics, however, remains open to further research.

The absence vs. presence of a generic NPI does not play a significant role in the distribution of N1 in the AIS dataset, but N1 is retained more frequently in combinations with specific types of NPIs, such as adjuncts. Analogously, N2 and certain NPIs (adjunct PPs and negative coordinators) can marginally co-occur in a negative concord configuration. If NPIs are licensed by N2, N1 seldom occurs.