In Between Description and Prescription: Analysing Metalanguage in Normative Works on Dutch 1550–1650

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Building the Corpus of Codification of Standard Dutch ca. 1550–1650

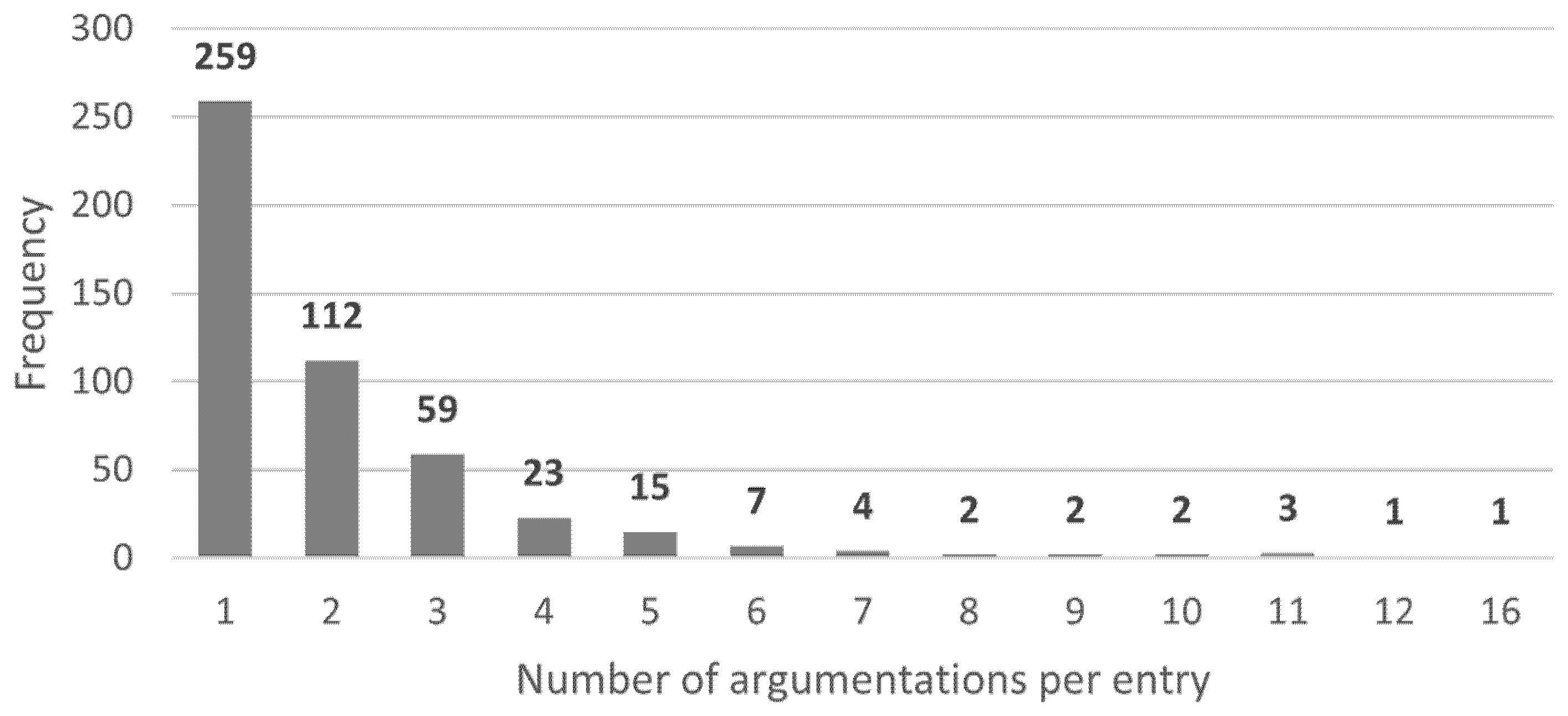

2.2. Selecting Entries

| Een-voudt. | ‘Singular. |

| N. Du. | Nominative: Du. |

| B. Dijns óft Dijnes, óft Dijner. | Genitive: Dijns or Dijnes or Dijner. |

| G. Dy. | Dative: Dy. |

| A. Dy. | Accusative: Dy. |

| Meêrvoudt. | Plural. |

| N. Ghy. | Nominative: Ghy. |

| B. Uwer. | Genitive: Uwer. |

| G. U. | Dative: U. |

| A. U. | Accusative: U.’ |

| (Kók 1649, p. 21; Dibbets 1981, p. 31) | |

2.3. Annotating Arguments

2.4. Analysis

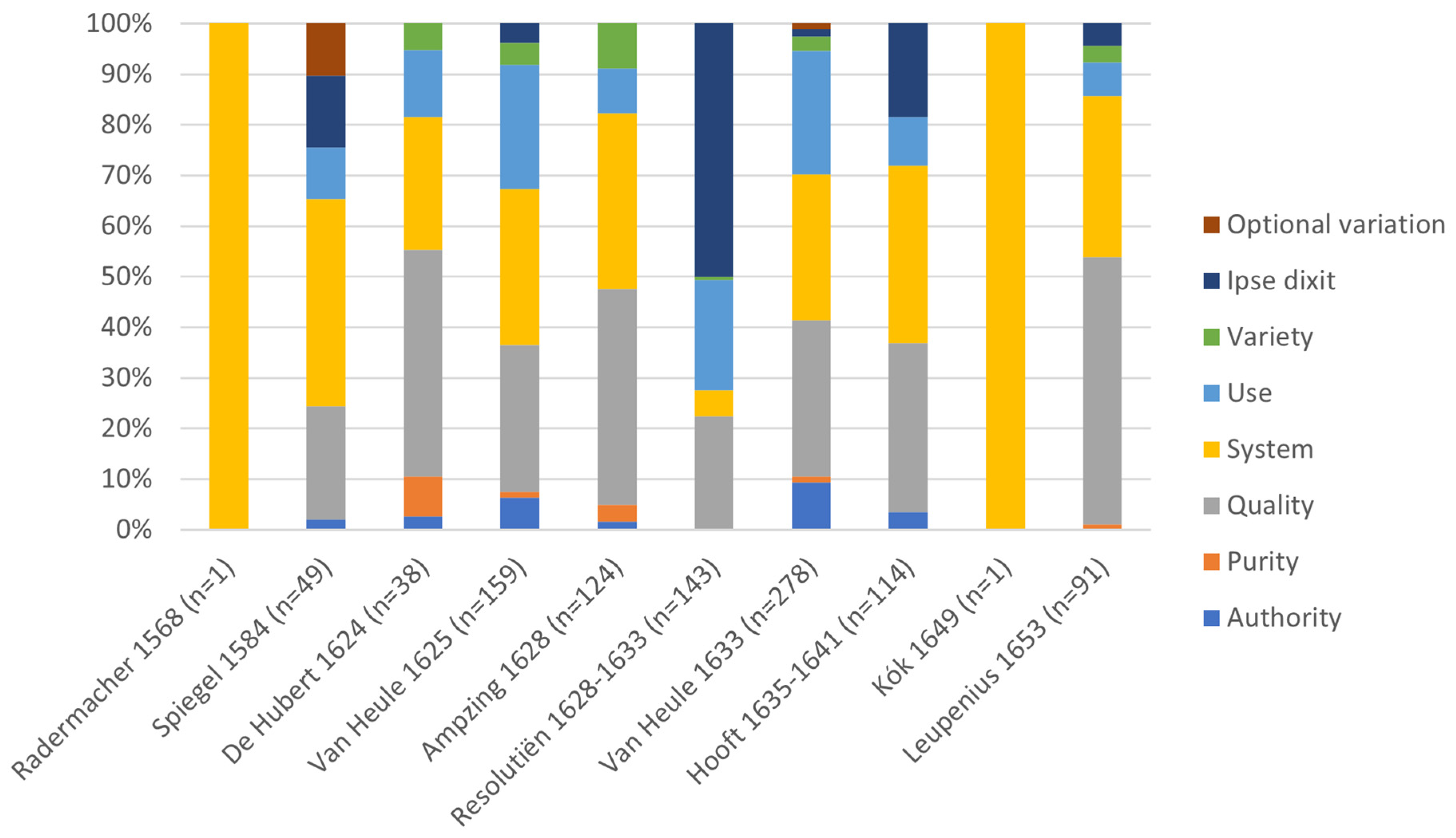

3. Results

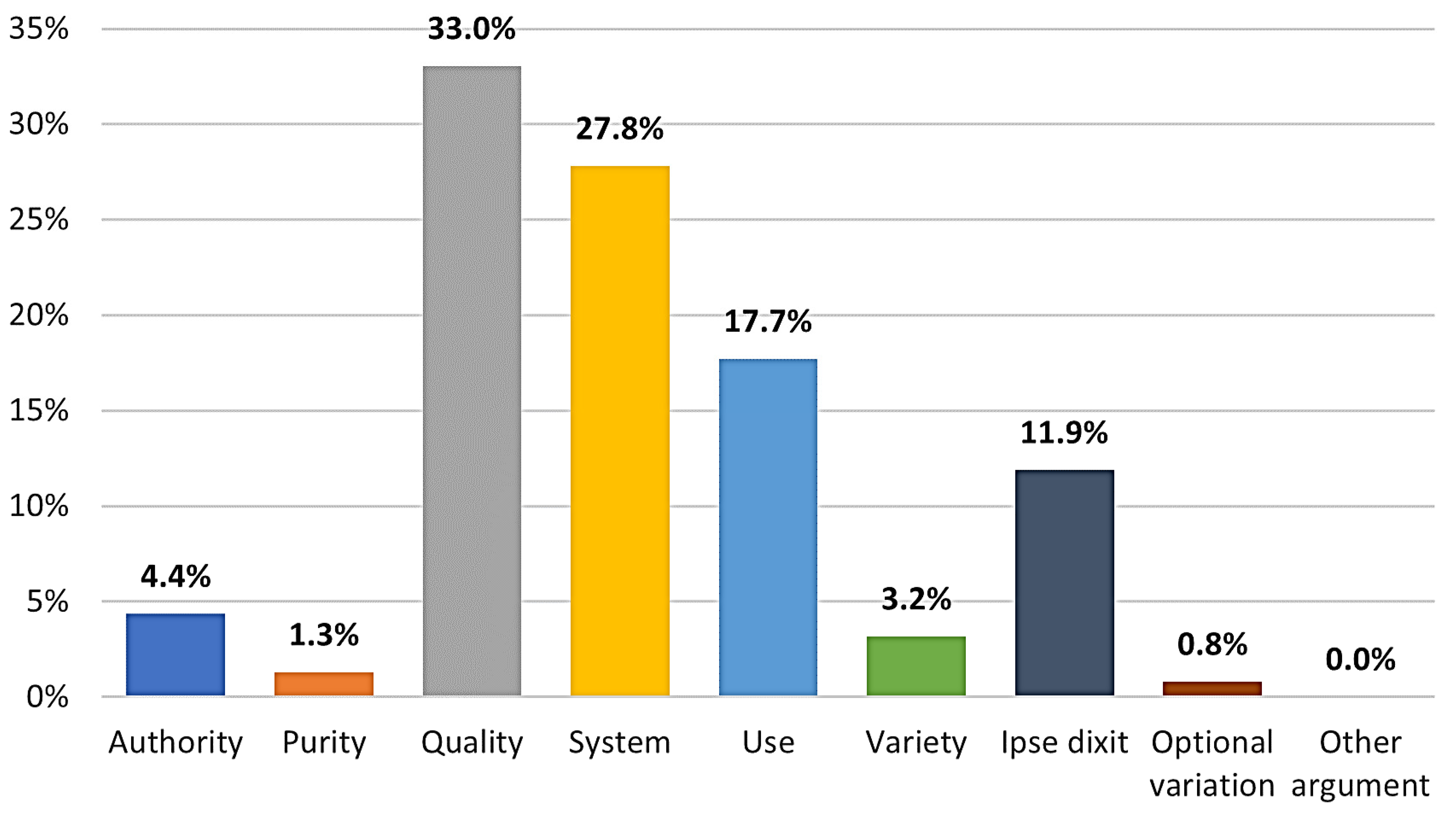

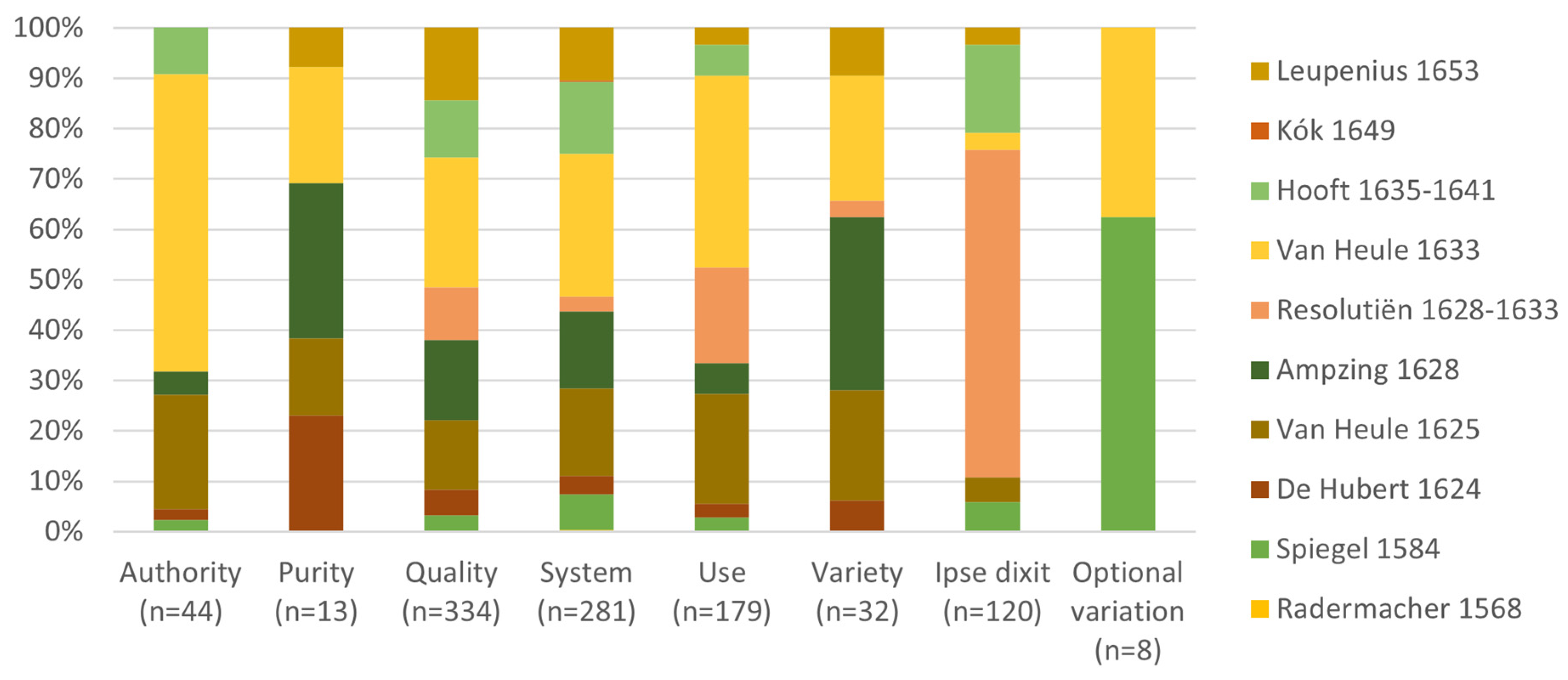

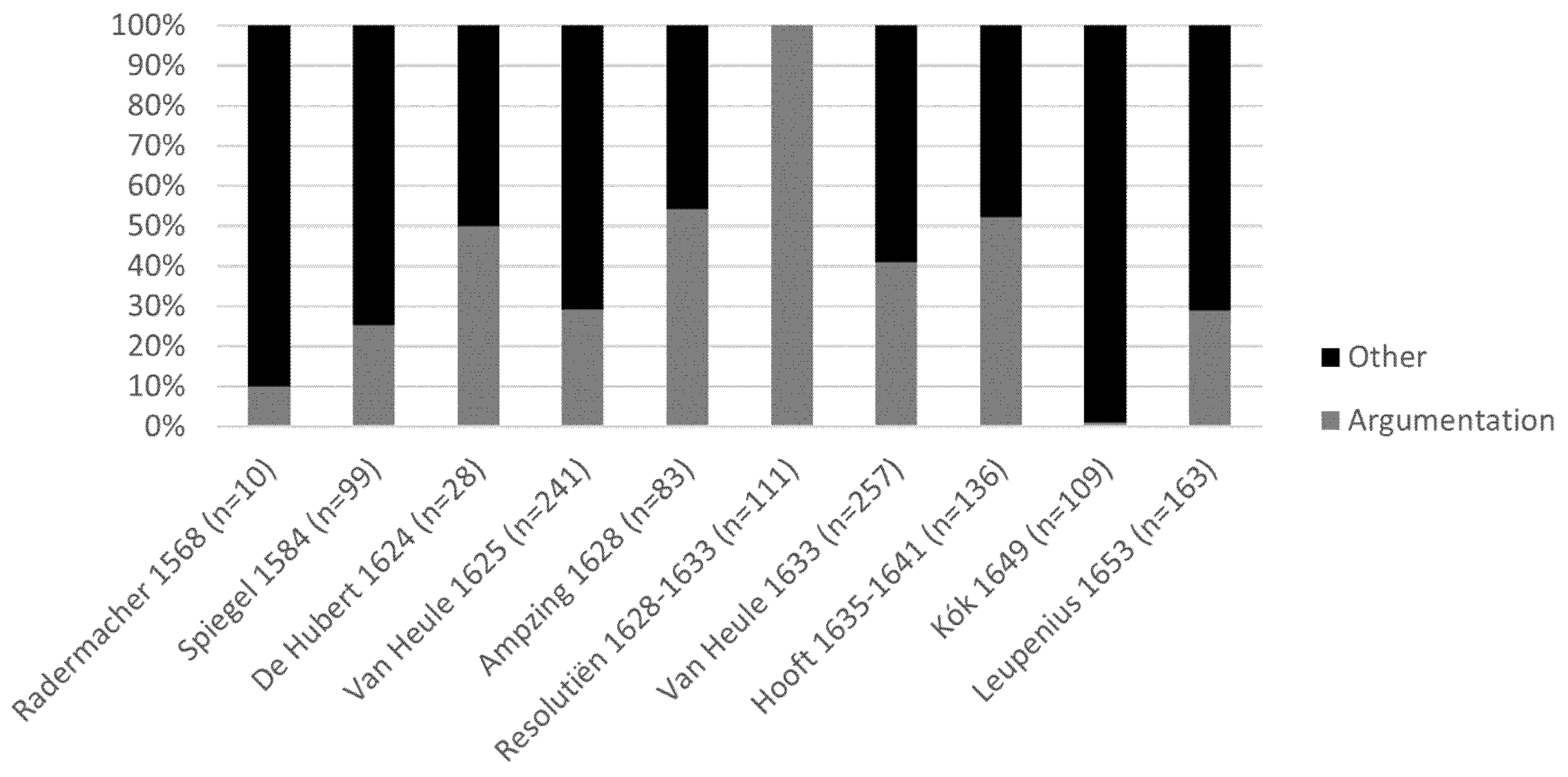

3.1. Arguments: Top-Level Categories

3.1.1. Comparison between the 16th/17th and the 20th/21st Centuries

3.2. Arguments: Lower-Level Categories

3.2.1. Comparison between the 16th/17th and the 20th/21st Centuries

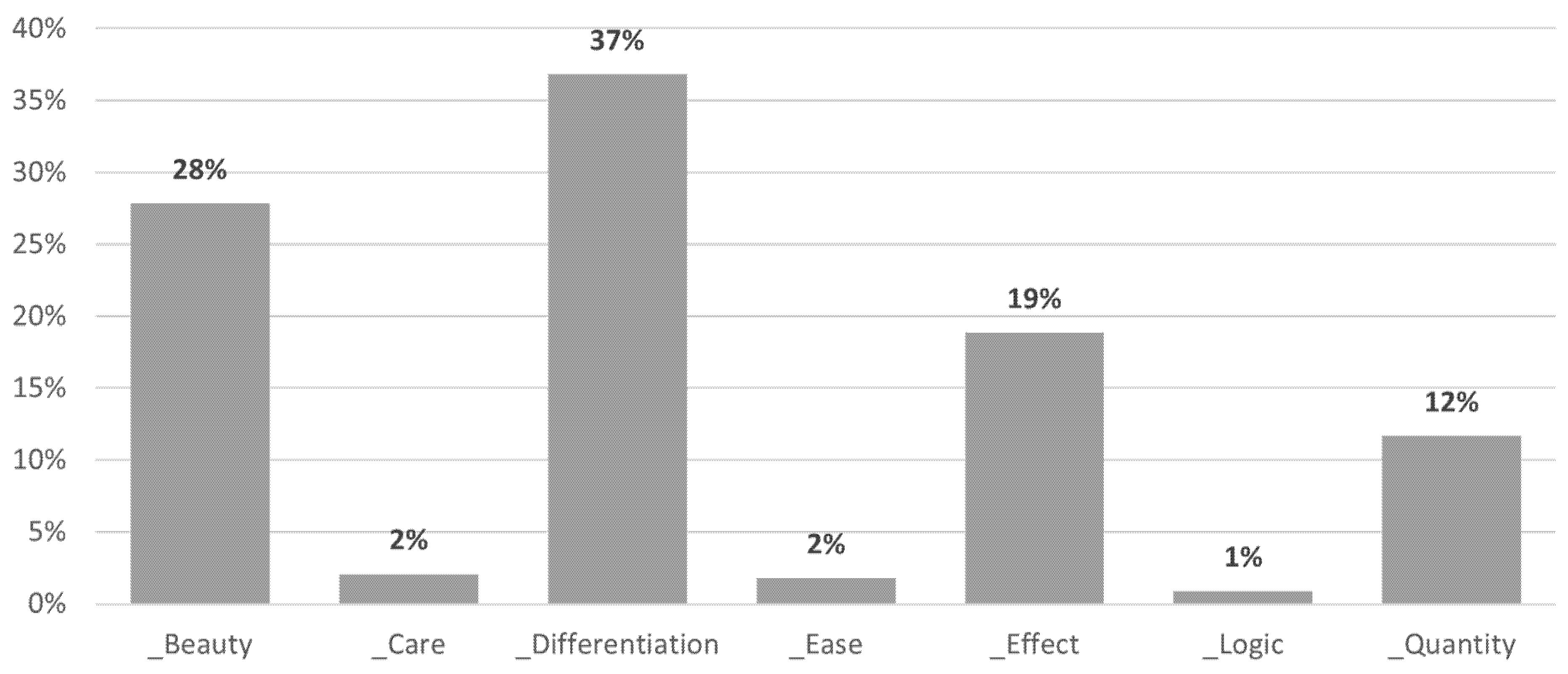

3.2.2. Quality

- Quality_Differentiation: Liever seggen wy ook ‘gy bent’, dan ‘gy syt’, tot onderscheid van den tweeden persoon in het meervoud, dat men altyd moet betrachten, wanneer men het krygen kann. ‘We also rather say gy bent ‘you are [sgl.]’ to distinguish it from the second person plural gy syt ‘you are [pl.]’, a distinction one should always observe when one can.’ (Leupenius 1653, p. 65; Caron 1958, p. 46).

- Quality_Beauty: Maer noch af-sienelicker is het dus-danige Tael-spreuken in plaetse van het twede geval te gebruyken, als ‘Mijn oom Zijn kint’, ‘Mijn Vader zijn Broeder’, ‘Der vrouwen Haer dochter, &c.’ ‘But it is even more disagreeable to use such phrases instead of the genitive, for instance: Mijn oom Zijn kint ‘My uncle his child’, Mijn Vader zijn Broeder ‘my father his brother’, Der vrouwen Haer dochter ‘the woman her daughter’, etc.’ (Van Heule 1633, p. 56; Caron 1971b, p. 42).

- Quality_Effect: De oorzaeke dat het woordeken ‘Zich’ zomwijlen voor ‘Hem’ gestelt wort, is om deze volgende twijffelachticheden te vermijden, als ‘Hy heeft hem daer mede gemoeyt’, uyt deze woorden en kan men niet verstaen of hy eenen anderen ofte zich zelven gemoeyt, heeft, maer alle twijffel wort weg genomen, als men zegt ‘Hy heeft zich daer mede gemoeyt’. ‘The reason that the word Zich ‘himself’ is sometimes used for Hem ‘him’ is to avoid the following dubiousness, for example in Hy heeft hem daer mede gemoeyt ‘He has involved him therein’. From these words, one cannot know whether he has involved another person or himself, but all doubt is removed when one says Hy heeft zich daer mede gemoeyt ‘He has involved himself therein’.’ (Van Heule 1625, p. 92; Caron 1971a, p. 74).

- Quality_Quantity: Jacop van der Schure, oordeelt de laetste E, in de Deel-woorden des generleyen geslachts heel overtollich, ic en zoude het zelve niet wel durven tegen-spreken. ‘Jacop van der Schure judges the final e in participles of the neutral gender entirely superfluous, I would not dare contradict it.’ (Van Heule 1633, p. 26; Caron 1971b, p. 23).

- Quality_Care: ‘Kennen’ noscere, ende ‘konnen’ posse, ‘ik ken’, ende ‘ik kan’, sijn van seer grooten onderscheyd, gelijk wy alle weten: doch worden dickwils onbedacht van den gemeynen man vermengd. ‘Kennen ‘to know’ and konnen ‘can’, ik ken ‘I know’ and ik kan ‘I can’ greatly differ from each other, as we all know, yet they are often carelessly confused by the common man.’ (Ampzing 1628, p. F1v; Zwaan 1939, p. 182).

- Quality_Ease: …: het onderscheid van beteekenisse kann uit de reeden lichtelyk gemerkt worden. Noch dat achten wy geen onvolmaaktheid, maar een groot gemakk voor onse taale: want hoe sy minder veranderinge onderworpen is, hoe sy lichter vallt om geleert te worden. ‘… the difference in meaning can easily be inferred from the sentence. Yet we do not see that as an imperfection, but as a great convenience for our language: for the fewer inflections it is subject to, the easier it is learnt.’ (Leupenius 1653, p. 44; Caron 1958, p. 31).

- Quality_Logic: Daar het een groot misbruik is dat ‘en’ somtyds genoomen wordt voor een ontkenninge, gestellt synde by ‘geen’ of ‘niet’: soo wordt gemeenlyk geseidt, ‘gy en sullt niet dooden’, ‘gy en sullt niet steelen’, ‘gy en sullt geen overspel doen’: doch dat is teegen den aard der ontkenningen: want daar twee ontkenningen by een komen, doen sy soo veel als eene bevestiginge: nu ‘geen’ en ‘niet’ syn ook ontkenningen, daarom kann ‘en’, als een ontkenninge, daar by geen plaatse hebben. ‘For it is a great abuse that en is sometimes added to geen ‘none’ or niet ‘not’ and so taken for a negation: thus it is commonly said gy en sullt niet dooden ‘you shall not kill’, gy en sullt niet steelen ‘you shall not steal’, gy en sullt geen overspel doen ‘you shall not commit adultery’: yet that is contrary to the nature of negations: for when two negations are combined, they add up to a confirmation: well, geen and niet are also negations, therefore en, as a negation, cannot be put next to it.’ (Leupenius 1653, p. 70; Caron 1958, p. 51).

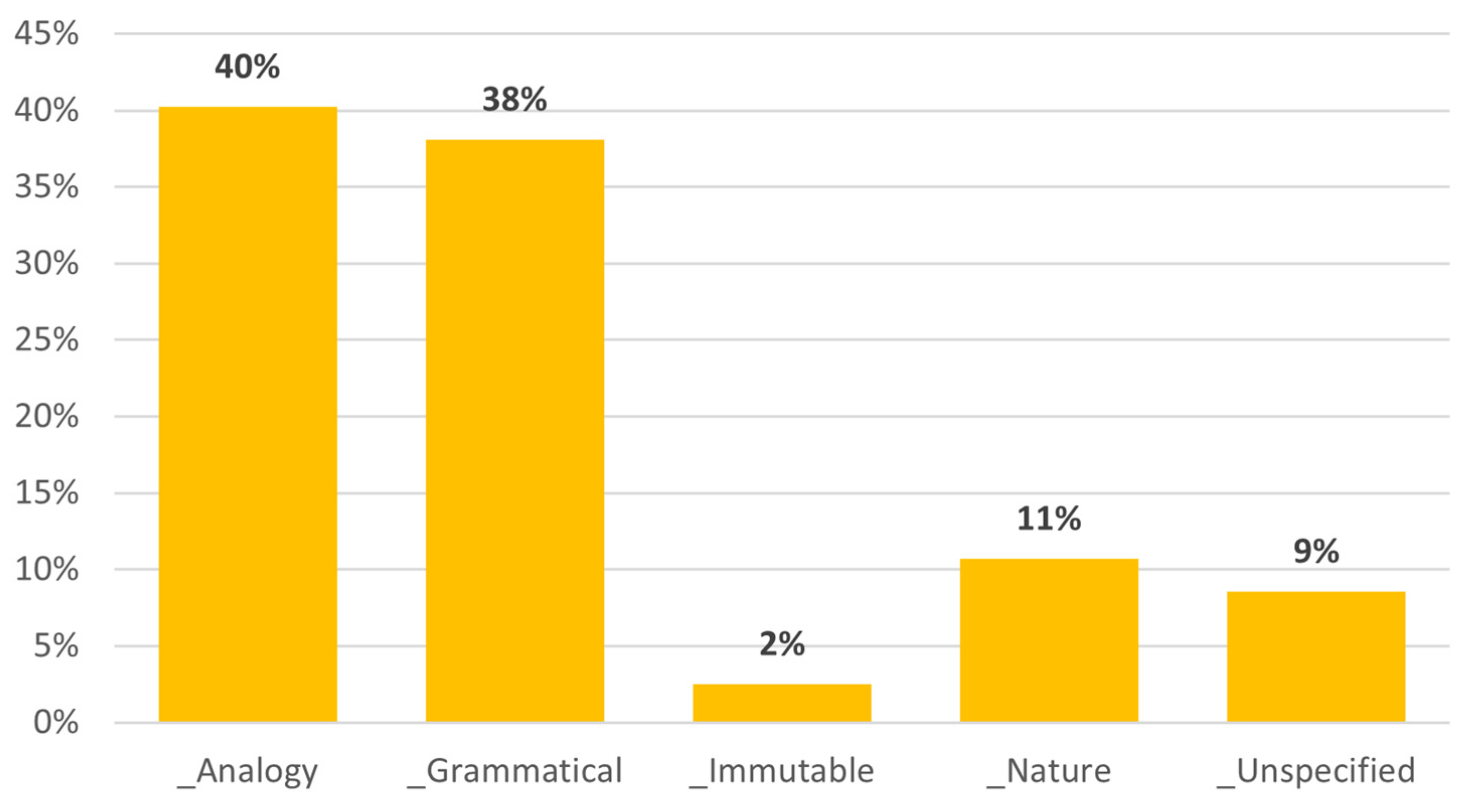

3.2.3. System

- System_Analogy: ’Ten is ook so vremd niet in onse tale, als wel sommige meenen, dat het woordeken ‘gij’ eens ende onveranderlick soude blijven in sijn enkel ende veelvoudig getal: want dit en is niet alleenlick in dit woordeken ‘Gij’, maar ook in eenige andere woorden gebruijkelick: so seijtmen; ‘die looft God’, ‘die loven God’, ‘sy looft God’, ‘sy loven God’. blijvende de woorden ‘die’ ende ‘sy’, gelijk het woordeken ‘gij’, onveranderlick in haare buijginge, ende nochtans niet te min onderscheijdelick in haar getal door het gevolg der t’samenvouginge. ‘And it is also not so strange that the word gij ‘you’ in our language, as some argue, has one form for the singular and plural: for this is not only the case in this word Gij, but also common in some other words: for one says die looft God ‘they [sgl.] praise God’, die loven God ‘they [pl.] praise God’, sy looft God ‘she praises God’, sy loven God ‘they praise God’. The words die and sy, just like the word gij, remain unaltered in their inflection, and are nonetheless distinguishable in number because of what follows.’ (de Hubert 1624, pp. *4r–*4v; Zwaan 1939, p. 394).

- System_Grammatical: XVI. EEN VOORTVAEREND MAN, EEN MAN VOORTVAERENDE VAN AERDT, Liever een MAN VOORTVAEREND VAN AERDT; om dat VOORTVAEREND hier geen Participum is, maer Nomen. ‘XVI. Een voortvaerend man ‘an expeditious man’, een man voortvaerende van aerdt, ‘a man expeditious in nature’. It is better to use een man voortvaerend van aerdt, because voortvaerend is not a participle here, but an adjective.’ (Zwaan 1939, p. 283).

- System_Nature: …, maer al hoewel deze maniere, niet geheel hart en valt, zo wijkt het nochtans van den aert onzer sprake. ‘…, but although this is not completely displeasing, yet it deviates from the nature of our language’ (Van Heule 1633, p. 35; Caron 1971b, p. 29).

- System_Unspecified: XLV. D’ANDER staende zonder Substantyf kan bequaemelijk in Dativo Singulari hebben DEN ANDRE. ‘XLV. D’ander ‘the other’ can, when it is used independently without a noun, appropriately have den andre in dative singular.’ (Zwaan 1939, p. 246).

- System_Immutable: Want wy en seggen niet, ‘het saed Jans’, ‘het huys Pieters’, maar ‘Jans saed’, ‘Pieters huys’, ofte ‘het saed van Jan’, ‘het huys van Pieter’. …: niettemin wanneermen wat sal schrijven, ende het licht laten sien, het welke de nakomelingen ook gebruyken sullen, so behoren wy vlijtig acht te nemen, ten eersten, dat wy Duytsch, ende daer na, goed ende suyver Duytsch mogten spreken: op dat de nakomelingen sich met der tijd daer aen mogten gewennen, ende onse tale toekomstig niet vervalscht, ende gebroken, maer oprecht, ende naer haeren oorspronkelijken aerd mogte uytgesproken worden. ‘For we do not say het saed Jans ‘the seed John’s’, het huys Pieters ‘the house Peter’s’, but Jans saed ‘John’s seed’, Pieters huys ‘Peter’s house’, or het saed van Jan ‘the seed of John’, het huys van Pieter ‘the house of Peter’. …: nevertheless, when we write and publish something which will also be used by our descendants, then we should diligently take into account, firstly, that we use Dutch, and secondly, that we use good and pure Dutch: so that, over time, our descendants may get accustomed to it, and our language will not be garbled and mispronounced in the future, but will be pronounced in the right way according to its original nature.’ (Ampzing 1628, p. A3r; Zwaan 1939, p. 141).

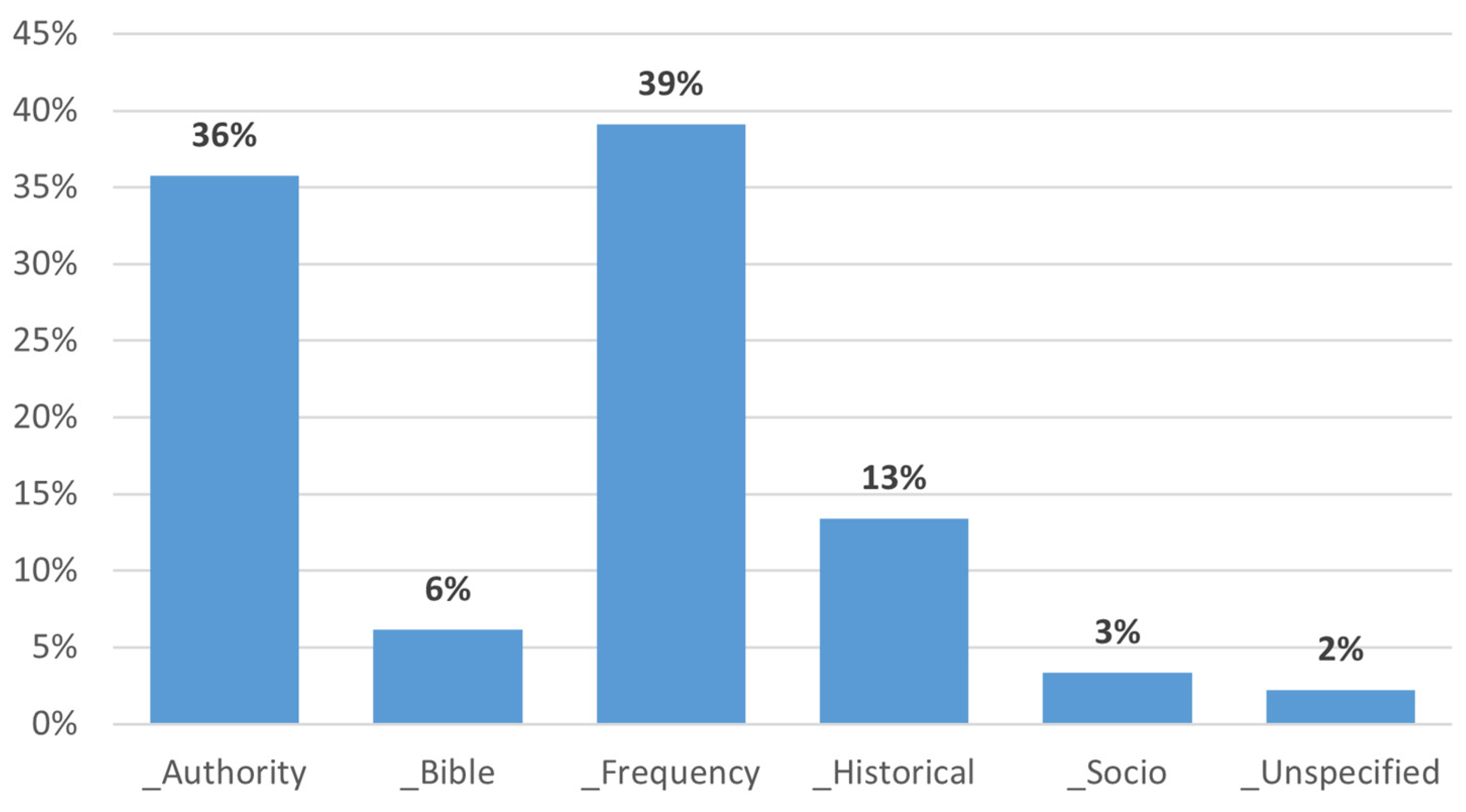

3.2.4. Use

- Use_Frequency: Anderzins so wanneer het Gevall blijkt uijt het voorgaande ledeken, ofte dat het met eenige vvoorden meer bekleed vvord, so en is sulks so seer niet van noode, immers in dit woord: so seijt men, ‘den goeden God sij lof’, ‘doet des hemels God belijd’: ende niet so seer gebruijkelick, ‘den goeden Gode’, ‘des hemels Gode’. ‘Something else happens when the case becomes apparent from the article in front of it, or when it is accompanied by a couple more words, for then this [inflection] is not necessary in the noun: for one says den goeden God sij lof ‘praise be to the good God’, doet des hemels God belijd ‘confess to the heavenly God’: and not so commonly used is den goeden Gode, des hemels Gode.’ (de Hubert 1624, p. *8r; Zwaan 1939, p. 127).

- Use_Authority: Dit waernemen der Gevallen in het Veelvoudig, is by de Ouden altijt gebruykt geweest, ook by Koornhert, Aldegonde, Grotius, Ampsingius, ende andere. ‘Observing cases in plural was common use for the Elders, also for Koornhert, Aldegonde, Grotius, Ampzing, and others.’ (Van Heule 1625, p. 24; Caron 1971a, p. 25).

- Use_Historical: Ende so wenschte ik wel, dat de woordekens ‘dij’, ende ‘dijn’, in heur oud gebruyk mogten hersteld worden, …. ‘And so I wish that the words dij ‘you’, and dijn ‘yours’, may be restored in their old use, ….’ (Ampzing 1628, p. E4v; Zwaan 1939, p. 180).

- Use_Bible: DE PAT, DEN PAT, an HET PAT, ut nostra et vulgatum est.(HET PAT) ‘De pat, den pat or het pat ‘the path’ like in ours [i.e., the Deux-Aes Bible] and in the Vulgate. ([decision:] Het pat)’ (Zwaan 1939, p. 216).

- Use_Socio: D. MY (nunquam MYN, ut vulgus hic loquitur) ‘Dative: my ‘me’ (never myn ‘mine’, like the common people say here)’ (Zwaan 1939, p. 212).

- Use_Unspecified: NEVEN, BENEVEN, NEFFENS, BENEFFENS, promiscue: spectetur usus. ‘Neven, beneven, neffens, beneffens ‘next to’, indiscriminately: it depends on its use.’ (Zwaan 1939, p. 209).

3.2.5. Ipse Dixit

3.2.6. Authority

- Authority_Grammar: … het welke de E. Christiaen van Heule, Mathematicus, in sijne Spraekkonste ook seer wel gemerkt, ende aengeteykend heeft. ‘…which was also noticed and noted by the honourable Christiaen van Heule, Mathematician, in his Spraekkonste ‘Grammar’.’ (Ampzing 1628, p. A2v; Zwaan 1939, p. 140).

- Authority_Unspecified: …zo en hebben wy ons tegens dat out ende noch het tegenwoordig gemeyn gebruyk niet dorven stellen, alhoewel het zelf eerst ons voornemen geweest is, te doen, maer door het oordeel eeniger hoochgeleerden, hebben wy bewogen geweest, dat naer te laeten, …. ‘…thus we have not dared to disapprove of that old nor of the present-day common use, even though it was our intention to do so first, but the opinion of a couple of scholars has persuaded us to leave it be, ….’ (Van Heule 1625, p. 11; Caron 1971a, p. 17).

- Authority_Frequency: Wy vougen hier in het out gebruyc der Werc-woorden, zonder welc gebruyc wy in onze Sprake zeer veel verliezen, ooc zijn tot de herstellinge des zelven, alle Tael-geleerde gheneycht geweest, als Koornhert, Aldegonde, Ampsingius, …. ‘We add here the old use of verbs, because without it we would lose a lot in our language, and all grammarians too have been in favour of revitalizing these, such as Koornhert, Aldegonde, Ampzing, ….’ (Van Heule 1633, pp. 87–88; Caron 1971b, p. 61).

3.2.7. Variety

- Variety_Genre: Dit onderscheyt der geslachten en behouft in den rijm altijt niet nagevolgt te worden, want om die oorzaeke zouden de Rijmers al te nouw gebonden zijn, in het waernemen der voeten, dewijl dan dat eenen afbreuk van onze spraekx cierlickheyt zoude veroorzaeken, zo wort den Rijmers, eene volle vryheyt gelaten, om de byvouglicke worden somtijts te verkorten. ‘This distinction of gender does not always need to be followed in poetry, because Poets would then be too restricted whilst observing poetic feet, which would then cause an impairment of our language’s grace, thus Poets are given full freedom to shorten adjectives sometimes.’ (Van Heule 1625, p. 16; Caron 1971a, p. 20).

- Variety_Geographic: In het verkleijnen der woorden hebben de Brabanders de meeste volkomenheyt. ‘In the diminutives, the people from Brabant have the most perfection.’ (Van Heule 1633, p. 161; Caron 1971b, p. 110).

- Variety_Mode: … om kortheids wille wordt somtyds voor ‘my’ en ‘wy’, ‘me’ en ‘we’ gebruikt, insonderheid daar sy achter een werkwoord gestellt worden, ‘sy hebbenme’, ‘soo seggenwe’: Wy laaten toe, datmen om de soetvloeijentheid soo spreeke: maar de letteren ten vollen uitschryve, ‘sy hebben my’, ‘soo seggen wy’. ‘… for brevity’s sake, me ‘me’ and we ‘we’ are sometimes used for my ‘me’ and wy ‘we’, especially when placed behind a verb: sy hebbenme ‘they have me’, soo seggenwe ‘so say we’. We allow speaking thus for euphonic reasons, but in writing, the letters need to be written out in their entirety: sy hebben my ‘they have me’, soo seggen wy ‘so say we’.’ (Leupenius 1653, p. 48–49; Caron 1958, p. 35).

3.2.8. Purity

- Purity_Unspecified: Geen weyniger misslag word-er in het stellen der by-worpige woorden begaen, als de selve niet voor, maer achter hunne selfstandige woorden geplaetst worden: als ‘een man groot’, ‘een kind kleyn’, ‘een paerd sterk’, voor ‘een groot man’, ‘een kleyn kind’, ‘een sterk paerd’, het welke te gansch ongerijmd is, ende onder deckzel van rijm-verlof geenzins te lijden: want men en mag so niet rijmen datmen de tale geweld doet: ende dat geen goed Duytsch en is, kan dat wel goed rijm wesen? Wy en mogen ons hier niet behelpen met andere spraken. Ygelijke tale heeft haere eygenschap: maer de onse en kan dit niet lijden. ‘There is no greater mistake in the use of adjectives than to place them not in front, but after their nouns: e.g., een man groot ‘a man great’, een kind kleyn ‘a child small’, een paerd sterk ‘a horse strong’, for een groot man ‘a great man’, een kleyn kind ‘a small child’, een sterk paerd ‘a strong horse’, which is entirely preposterous and cannot be suffered under poetic license: for even in rhyme the language must not be violated: and that which is not good Dutch, can that even be good poetry? We cannot make do with other languages here. Every language has their own characteristics: but ours cannot suffer this.’ (Ampzing 1628, p. F3r; Zwaan 1939, pp. 185–86).

- Purity_Latinism: Hier uyt is ook ontstaen, dat men de aengenomene vreemde woorden in de eyge namen in hunne gevallen naer de Latijnsche wijse liever heeft willen buygen, als naer onse eygene: so seggen onse geleerden, Petrus, Petri, Petro, Petrum, Petre, Petro: Samuel, Samuelis, Samueli, Samuelem, Samuel, Samuele, &c. dat dan immers geen goed Duytsch en kan wesen, ‘From this it has also arisen that people have preferred to use Latin case inflections in accepted foreign proper names rather than our own: so our scholars say Petrus, Petri, Petro, Petrum, Petre, Petro: Samuel, Samuellis, Samueli, Samuelem, Samuel, Samuele, etc. which cannot be good Dutch.’ (Ampzing 1628, p. A2v; Zwaan 1939, p. 140).

- Purity_Gallicism: VVant onder deckzel van rijmen, den VVaal te spelen, is ganz ongerijmd, ende te seggen; … ‘Hij is genegen niet’, voor; ‘Hij is niet genegen’. ‘De gunste goed’, voor; ‘de goede gunst’’. …, ende diergelijke wijse van spreken meer; is het Nederduijtz VValzelick, ende valzelick verdraijd…. ‘For to play the Walloon disguised by rhyme is entirely preposterous, and to say: … Hij is genegen niet ‘He is inclined not’ for Hij is niet genegen ‘He is not inclined’. De gunste goed ‘The favour good’ for De goede gunste ‘The good favour’. …, and such ways of speaking is twisting Dutch Walloonishly and falsely….’ (de Hubert 1624, p. *6r; Zwaan 1939, p. 123).

3.2.9. Optional variation

4. Discussion

5. Summary

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Normative Works Included in the Corpus in Chronological Order (Edition Used)

Appendix B. Annotation Schema for the Type of Entry with Definitions

| Type of Entry | Definition |

| argumentation | A certain variant or use is discouraged or advocated, possibly motivated by the use of argumentation(s) |

| definition | A definition of a linguistic term or concept, either a proper definition or a definition by ways of explaining certain properties of the term/concept, is given, sometimes followed by illustrative examples |

| enumeration | An enumeration, i.e., a (somewhat, or meant to be) exhaustive list is given either of the words that are covered by a certain linguistic term or concept or of the types of that particular term/concept |

| paradigm | A paradigm of the inflection of a certain part of speech is offered in the form of a paradigm or table |

| paradigm_text | An entry detailing the inflection of a certain part of speech not in a table or paradigm but enumerated in words |

| question | A question about a certain linguistic phenomenon is raised without being answered |

| rule | A rule is posed without the presence of a rejected or preferred use: no verdict and/or argumentation |

| 1 | The edition primarily used for Hooft’s Waernemingen is from 1723 (Ten Kate 1723), so the 1700 edition is, technically speaking, not a later edition. However, it contains fewer observations than the 1723 edition, leading us to treat the 1723 edition as the core edition and to include the 1700 edition for comparison only. |

| 2 | Poplack et al. (2015), for instance, do include posited rules without explicit acknowledgement of variation in their study of what they call ‘pertinent mentions’ of certain linguistic topics. This is possible because of their top-down approach: they have first decided what linguistic variables to study and have subsequently looked for mentions in normative works on those variables. The variables studied were selected because of the presence of competing variants, thereby presupposing that the rules found could indeed be read as judgements on variation. |

| 3 | Some of the categories in the schema correspond to the seven different ‘standards of correctness’ distinguished by Jespersen in linguistic judgements made by ordinary language users (Jespersen 1925, pp. 94–122): the standard of authority (corresponding to all lower-level categories of Authority arguments), the geographical standard (Variety_Geographic), the literary standard (Use_Literary), the aristocratic standard (Use_Socio), the democratic standard (equal to Use_Frequency), the logical standard (corresponding to Quality_Logic but also System_Grammatical and System_Analogy, esp. _Latin), and the aesthetic standard (Quality_Beauty). He denounces them all as inadequate for use ‘as a trustworthy scientific standard which will enable us to pass an infallible judgement in any doubtful cases that may turn up’ (Jespersen 1925, pp. 121–22). |

| 4 | Ipse dixit in the early modern period = Optional variation in the (post)modern period. Optional variation receives a different interpretation in the early modern period (see Section 2). |

| 5 | The lower-level category Quality_Ease was also added to the schema to accommodate it to this time period. It was applied when a certain variant was advocated because of its ease to use or learn (or proscribed for the opposite reason). Its low frequency of n = 6, however, indicates that it cannot be seen as truly characteristic for this time period. |

| 6 | The lower-level tag System_Immutable was also added for the purposes of this study. It is used to indicate that a (new) variant is repressed because language should not change, according to the grammarian. Like with Quality_Ease, its low frequency (n = 7) indicates no particular relevance of the presence of this type in the formative period of Standard Dutch. |

| 7 | In addition to _Authority, the lower-level category _Bible was added for the study of the early modern period. These references to biblical usage, however, were not present across the board but mostly found in de Hubert’s normative work and in the Resolutiën, which correlates to the nature of these works: de Hubert’s Noodige waarschouwinge aan alle liefhebbers der Nederduijtze tale ‘Necessary Warnings to All Lovers of the Dutch Language’ (de Hubert 1624) was published as a preface to his translation of the Psalms of David; the Resolutiën (1628–1633) consists of the linguistic decisions made by the translators of the first official Bible translation. Both works thus had to relate themselves to the Bible. |

| 8 | In total, 16 different authors were referenced, in order of frequency: Aldegonde (9), Grotius (8), Heyns (7), Cats (6), Coornhert (5), Ampzing (4), Kiliaan (3), Stevin (2), Cornelius (1), ‘de Amsterdamse letter-konstenaars’ (probably a reference to Spiegel, 1), de Hubert (1), Helmichius (1), De Heuiter (1), De Brune (1), Kamphuizen (1), and Wttenhove (1). |

References

- Amorós-Negre, Carla. 2008. Norma y Estandarización. Salamanca: Luso Española. [Google Scholar]

- Amorós-Negre, Carla. 2020. 12.2 Normative Grammars. In Manual of Standardization in the Romance Languages. Edited by Lebsanft Franz and Tacke Felix. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 581–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampzing, Samuel. 1628. Nederlandsch tael-bericht. In Beschrijvinge Ende Lof der Stad Haerlem. Haarlem: Adriaen Rooman, pp. A1r–G2r. [Google Scholar]

- Anderwald, Lieselotte. 2012. Clumsy, awkward or having a peculiar propriety? Prescriptive judgements and language change in the 19th century. Language Sciences 34: 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres-Bennett, Wendy. 2019. From Haugen’s codification to Thomas’s purism: Assessing the role of description and prescription, prescriptivism and purism in linguistic standardisation. Language Policy 19: 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blommaert, Jan. 1999. Language Ideological Debates. Language, Power and Social Process. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bostoen, Karel. 1985. Kaars en Bril: De Oudste Nederlandse Grammatica. Middelburg: Koninklijk Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen. [Google Scholar]

- Britain, David, and Peter Trudgill. 2005. New dialect formation and contact-induced reallocation: Three case studies from the english fens. International Journal of English Studies 5: 183–209. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Peter. 2004. Languages and Communities in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, Willem J. H. 1958. Petrus Leupenius, Aanmerkingen op de Neederduitsche Taale en Naaberecht (1653–1654). Groningen: J.B. Wolters. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, Willem J. H. 1971a. Christiaan van Heule, De Nederduytsche Grammatica ofte Spraec-konst (1625). Volume 1. Trivium, Nr. I. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff N.V. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, Willem J. H. 1971b. Christiaen van Heule, De Nederduytsche Spraec-Konst Ofte Tael-beschrijvinghe (1633). Volume 2. Trivium, Nr. I. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff N.V. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, Don. 2019. “Splendidly prejudiced”. Words for Disapproval in English Usage Guides. In Norms and Conventions in the History of English. Edited by Birte Bös and Claudia Claridge. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory, 0304-0763. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 347, pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, Don. 2021. ‘Not just a few dozen trouble spots’. Tallying the Rules in English Usage Guides. Paper presented at the 6th Prescriptivism Conference, Vigo, Spain, September 25. [Google Scholar]

- de Hubert, A. 1624. Voorrede & Noodige waarschouwinge aan alle liefhebbers der Nederduijtze tale. In De psalmen des Propheeten Davids. Leiden: Pieter Muller. [Google Scholar]

- de Vos, Machteld. Forthcoming. ‘Deze verscheydenheyt der Voornamen’: Codification of third-person pronouns in Early Modern Dutch. Taal en tongval.

- de Vos, Machteld, and Marten van der Meulen. 2021. Suppressed no more: Prescriptivism and the evaluation of (optional) variability. Paper presented at the 6th Prescriptivism Conference, Vigo, Spain, September 24. [Google Scholar]

- Deumert, Ana, and Wim Vandenbussche. 2003a. Standard languages. Taxonomies and histories. In Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present. Edited by Ana Deumert and Wim Vandenbussche. In Impact, 1385-7908. Amsterdam: Benjamins, vol. 18, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Deumert, Ana, and Wim Vandenbussche. 2003b. Research directions in the study of language standardization. In Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present. Edited by Ana Deumert and Wim Vandenbussche. In Impact, 1385-7908. Amsterdam: Benjamins, vol. 18, pp. 455–69. [Google Scholar]

- Dibbets, Geert R. W. 1981. A.L. Kok, Ont-Werp der Neder-Duitsche Letter-Konst (1649). Assen: Van Gorcum. [Google Scholar]

- Dibbets, Geert R. W. 1985. Twe-Spraack Vande Nederduitsche Letterkunst (1584). Assen and Maastricht: Van Gorcum. [Google Scholar]

- Dibbets, Geert R. W. 1995. De Woordsoorten in de Nederlandse Triviumgrammatica. Amsterdam: Stichting Neerlandistiek VU, Münster: Nodus Publikationen. [Google Scholar]

- Ebner, Carmen. 2016. Language guardian BBC? Investigating the BBC’s language advice in its 2003 News Styleguide. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37: 308–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, Michel. 1966. Les Mots et les Choses: Une Archéologie des Sciences Humaines. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, Susan, and Kathryn A. Woolard, eds. 2001a. Constructing Languages and Publics: Authority and representation. In Language and Publics: The Making of Authority. Manchester: St. Jerome. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, Susan, and Kathryn A. Woolard. 2001b. Language and Publics: The Making of Authority. Manchester: St. Jerome. [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum, Sidney. 1988. Good English and the Grammarian. English Language Series 17; London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Grondelaers, Stefan, and Roeland van Hout. 2011. The standard language situation in The Netherlands. In Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe. Edited by Tore Kristiansen and Nikolas Coupland. pp. 113–18. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2066/94744 (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Grondelaers, Stefan, Roeland van Hout, and Paul van Gent. 2016. Destandardization is not destandardization. Taal en Tongval 68: 119–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, Einar. 1966. Dialect, Language, Nation. American Anthropologist 68: 922–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüning, Matthias, Ulrike Vogl, and Olivier Moliner. 2012. Standard Languages and Multilingualism in European History. Volume 1: Multilingualism and Diversity Management. Amsterdam: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, Judith T., and Susan Gal. 2000. Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In Regimes of Language. Ideologies, Polities, and Identities. Edited by Paul V. Kroskrity. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, pp. 35–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jespersen, Otto. 1925. Mankind, Nation and Individual from a Linguistic point of View. Instituttet for Sammenlignende Kulturforskning. Serie A, Forelesninger. 4. Oslo: Aschehoug. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, John E., Gijsbert Rutten, and Rik Vosters. 2020. Dialect, language, nation: 50 years on. Language Policy 19: 161–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kók, Adam. L. 1649. Ont-Werp Der Neder-Duitsche Letter-Konst. Amsterdam: Johannes Troóst. [Google Scholar]

- Kostadinova, Viktorija. 2018. Language Prescriptivism: Attitudes to Usage vs. Actual Language Use in American English. Ph.D. dissertation, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Kroskrity, Paul V. 2000. Regimes of Language. Ideologies, Polities, and Identities. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leupenius, Petrus. 1653. Aanmerkingen op de Neederduitsche Taale. Amsterdam: Hendryk Donker. [Google Scholar]

- Milroy, James, and Leslie Milroy. 1999. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschonas, Spiros. 2020. Correctives and language change. In La Correction En Langue(s) = Linguistic Correction-Correctness. Edited by Sophie Raineri, Martine Sekali and Agnès Leroux. Nanterre: Presses Universitaires de Paris Nanterre. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual Rodríguez, José A., and Emilio Prieto de los Mozos. 1998. Sobre el estándar y la norma. In Visiones Salmantinas (1898/1998). Edited by Conrad Kent and María Dolores de la Calle. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca and Ohio Wesleyan University, pp. 63–95. [Google Scholar]

- Poplack, Shana, Lidia-Gabriela Jarmasz, Nathalie Dion, and Nicole Rosen. 2015. Searching for standard French: The construction and mining of the Recueil historique des grammaires du français. Journal of Historical Sociolinguistics 1: 13–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutten, Gijsbert. 2016. Standardization and the myth of neutrality in language history. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2016: 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutten, Gijsbert. 2019. Language Planning as Nation Building. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rutten, Gijsbert, and Rik Vosters. 2020. Revisiting Haugen: Historical-Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Standardization. Language Policy 19: 161–326. [Google Scholar]

- Rutten, Gijsbert, Rik Vosters, and Wim Vandenbussche. 2014a. The interplay of language norms and usage patterns: Comparing the history of Dutch, English, French and German. In Norms and Usage in Language History, 1600–1900: A Sociolinguistic and Comparative Perspective. Edited by Gijsbert Rutten, Rik Vosters and Wim Vandenbussche. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rutten, Gijsbert, Rik Vosters, and Wim Vandenbussche. 2014b. Norms and Usage in Language History, 1600–1900: A Sociolinguistic and Comparative Perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmons, Joe. 2018. A History of German: What the Past Reveals about Today’s Language, 2nd ed. Oxford Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schieffelin, Bambi B., Kathryn A. Woolard, and Paul V. Kroskrity. 1998. Language Ideologies: Practice and Theory. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Siegenbeek, Matthijs. 1804. Verhandeling over de Nederduitsche Spelling ter Bevordering van de Eenparigheid in Dezelve. Amsterdam: J. Allart. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, Michael. 1979. Language Structure and Linguistic Ideology. In The Elements: A Parasession on Linguistic Units and Levels. Edited by Paul R. Cline, William F. Hanks and Carol L. Hofbauer. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel, Hendrik Laurensz. 1584. Twe-Spraack Vande Nederduitsche Letterkonst. Leiden: Christoffel Plantijn. [Google Scholar]

- Straaijer, Robin. 2018. The usage guide: Evolution of a genre. In English Usage Guides: History, Advice, Attitudes. Edited by Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sundby, Bertil, Anne Kari Bjørge, and Kari E. Haugland. 1991. A Dictionary of English Normative Grammar, 1700–1800. Studies in the History of the Language Sciences 63. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Kate, Lambert. 1723. Aenleiding tot de Kennisse van het Verhevene deel der Nederduitsche Sprake. Amsterdam: Rudolph en Gerard Wetstein, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, George. 1991. Linguistic Purism. London and New York: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meulen, Marten. 2018. Do we want more or less variation? Linguistics in the Netherlands 35: 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meulen, Marten. 2019. Obama, SCUBA or gift? English Today 36: 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van der Meulen, Marten. 2020. 7 Language Should Be Pure and Grammatical: Values in Prescriptivism in the Netherlands 1917–2016. In Language Prescription. Values, Ideologies and Identity. Edited by Don Chapman and Jacob D. Rawlins. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 121–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Sijs, Nicoline. 2021. Taalwetten Maken en Vinden: Het Ontstaan van het Standaardnederlands. Gorredijk: Sterck & De Vreese. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Wal, Marijke J. 1995. De moedertaal Centraal. Standaardisatie-Aspecten in de Nederlanden Omstreeks 1650. Volume 3: Nederlandse Cultuur in Europese Context, Monografieën en Studies. Den Haag: Sdu Uitgevers. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Wal, Marijke J., and Cor Van Bree. 1992. Geschiedenis van Het Nederlands. Utrecht: Het Spectrum. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hardeveld, Ike. 2000. Lodewijk Meijer (1629–1681) als Lexicograaf. Ph.D. dissertation, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Van Heule, Chr. 1625. De Nederduytsche Grammatica ofte Spraec-Konst. Leiden: Daniel Roels. [Google Scholar]

- Van Heule, Chr. 1633. De Nederduytsche Spraeck-Konst Ofte Tael-Beschrijvinghe. Leiden: Jacob Roels. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoogstraten, David. 1700. Aenmerkingen over de Geslachten der Zelfstandige Naemwoorden. Amsterdam: François Halma. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, Richard J. 2011. Language Myths and the History of English. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weiland, P. 1805. Nederduitsche Spraakkunst, Uitgegeven in Naam en op Last van het Staatsbestuur der Bataafsche Republiek. Amsterdam: J. Allart. [Google Scholar]

- Willemyns, Roland. 2003. Dutch. In Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present. Edited by Ana Deumert and Wim Vandenbussche. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 93–125. [Google Scholar]

- Woolard, Kathryn A. 1992. Language Ideology: Issues and Approaches. Pragmatics 2: 235–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolard, Kathryn A. 1998. Introduction: Language Ideology as a Field of Inquiry. In Language Ideologies: Practice and Theory. Edited by Bambi B. Schieffelin, Kathryn A. Woolard and Paul V. Kroskrity. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zwaan, F. L. 1939. Uit de Geschiedenis Der Nederlandsche Spraakkunst. Grammatische Stukken van de Hubert, Ampzing, Statenvertalers en Reviseurs, en Hooft, Uitgegeeven, Samengevat en Toegelicht. Groningen and Batavia: J.B. Wolters’ Uitgevers-maatschappij N.V. [Google Scholar]

| Top-Level | Lower-Level | Subcategory | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authority | _Unspecified | Good language is determined by what an authority says | |

| _Dictionary | Good langue is determined by what a dictionary says | ||

| _Frequency | Good language is determined by what a number of people say | ||

| _Grammar | Good language is determined by what a grammar or grammarian says | ||

| _Literary | Good language is determined by what an author says | ||

| _Socio | Good language is determined by what a certain group of people says | ||

| Purity | _Unspecified | Language should be pure, free of influences of other language | |

| _Anglicism | Language should be free of English influence | ||

| _Gallicism | Language should be free of French influence | ||

| _Germanism | Language should be free of German influence | ||

| _Latinism | Language should be free of Latin influence | ||

| _Other_Language | Language should be free of the influence of another language | ||

| Quality | _Unspecified | Language should be qualitative | |

| _Beauty | Language should be beautiful | ||

| _Care | Language should be well taken care of | ||

| _Differentiation | Language should differentiate | ||

| _Ease | Language should be easy | ||

| _Effect | Language should have good effects | ||

| _Logic | Language should be logical | ||

| _Quantity | Language should be used in the right quantities | ||

| System | _Unspecified | Language should adhere to the system | |

| _Analogy | _Unspecified | It should (not) work the same as in another (unspecified) language | |

| _Dutch | It should (not) work the same as in another Dutch construction | ||

| _German | It should (not) work the same as in German | ||

| _Greek | It should (not) work the same as in Greek | ||

| _Hebrew | It should (not) work the same as in Hebrew | ||

| _Latin | It should (not) work the same as in Latin | ||

| _Grammatical | Language should be grammatical | ||

| _Immutable | Language should not be changed | ||

| _Nature | Language should be used according to the nature of the language | ||

| Use | _Unspecified | Good language is determined by what is done | |

| _Authority | Good language is determined by what an authority does | ||

| _Dictionary | Good language is determined by what a dictionary does | ||

| _Grammar | Good language is determined by what a grammar or grammarian does | ||

| _Literary | Good language is determined by what an author does | ||

| _Bible | Good language is determined by what the Bible does | ||

| _Frequency | Good language is determined by what a number of people do | ||

| _Historical | Good language is determined by what was done in the past | ||

| _Socio | Good language is determined by what a certain group of people says | ||

| Variety | _Unspecified | A specific variety of language is the right one | |

| _Genre | Language should be used in the proper genre (e.g., poetry vs. prose) | ||

| _Geographic | The language spoken in certain geographic regions is right/wrong | ||

| _Mode | Language should be used in the proper mode (i.e., written vs. spoken) | ||

| _Register | Language should be used in the proper register (i.e., formal vs. informal) | ||

| _Standard | Language should be used in accordance to the standard | ||

| Ipse dixit | No argument is given | ||

| Optional variation | Language should (not) contain variation | ||

| Other argument | There is some other reason why language is good or bad |

| Grammarian | Number of Arguments (Absolute Frequency) |

|---|---|

| Van Heule 1633 | 278 |

| Van Heule 1625 | 159 |

| Resolutiën 1628–1633 | 156 |

| Ampzing 1628 | 124 |

| Hooft 1635–1641 | 114 |

| Leupenius 1653 | 91 |

| Spiegel 1584 | 49 |

| de Hubert 1624 | 38 |

| Kók 1649 | 1 |

| Radermacher 1568 | 1 |

| Total | 1011 |

| Top-Level Category | % of Total Number of Arguments | |

|---|---|---|

| 16th/17th Century (ca. 1550–1650) | 20th/21st Century (1917–2016) | |

| Quality | 33.0% | 15.1% |

| System | 27.8% | 28.2% |

| Use | 17.7% | 4.6% |

| Ipse dixit4 | 11.9% | NA |

| Authority | 4.4% | 8.1% |

| Variety | 3.2% | 7.7% |

| Purity | 1.3% | 25.1% |

| Optional variation (see note 4) | 0.8% | 10.6% |

| Other argument | NA | 0.7% |

| Top-Level Category | Lower-Level Categories | Absolute Frequency (% of Total) |

|---|---|---|

| Quality (334, 33.0%) | _Differentiation, | 123 (12.2%) |

| _Beauty, | 93 (9.2%) | |

| _Effect, | 63 (6.2%) | |

| _Quantity, | 39 (3.9%) | |

| _Care, | 7 (0.7%) | |

| _Ease, | 6 (0.6%) | |

| _Logic, | 3 (0.3%) | |

| _Unspecified | NA | |

| System (281, 27.8%) | _Analogy, | 113 (11.2%) |

| _Grammatical, | 107 (10.6%) | |

| _Nature, | 30 (3.0%) | |

| _Unspecified, | 24 (2.4%) | |

| _Immutable | 7 (0.7%) | |

| Use (179, 17.7%) | _Frequency, | 70 (6.9%) |

| _Authority (incl. _Dictionary, _Grammar, _Literary), | 64 (6.3%) | |

| _Historical, | 24 (2.4%) | |

| _Bible, | 11 (1.1%) | |

| _Socio, | 6 (0.6%) | |

| _Unspecified | 4 (0.4%) | |

| Ipse dixit | 120 (11.9%) | |

| Authority (44, 4.4%) | _Grammar, | 26 (2.6%) |

| _Unspecified, | 14 (1.4%) | |

| _Frequency, | 4 (0.4%) | |

| _Dictionary, _Literary, _Socio | NA | |

| Variety (32, 3.2%) | _Genre, | 18 (1.8%) |

| _Geographic, | 10 (1.0%) | |

| _Mode | 4 (0.4%) | |

| _Register, _Standard, _Unspecified | NA | |

| Purity (13, 1.3%) | _Unspecified | 7 (0.7%) |

| _Latinism, | 5 (0.5%) | |

| _Gallicism, | 1 (0.1%) | |

| _Anglicism, _Germanism, _Other_Language | NA | |

| Optional variation | 8 (0.8%) | |

| Other argument | NA |

| Category | % of Total Number of Arguments | Category | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16th/17th Century (ca. 1550–1650) | 20th/21st Century (1917–2016) | ||

| Quality_Differentiation | 12.2% | 22.4% | System_Grammatical |

| System_Analogy | 11.9% | 12.1% | Purity_Germanism |

| Ipse dixit (see note 4) | 11.2% | 10.6% | Optional variation (see note 4) |

| System_Grammatical | 10.6% | 9.7% | Purity_Unspecified |

| Quality_Beauty | 9.2% | 5.6% | Quality_Effect |

| Use_Frequency | 6.9% | 4.3% | Variety_Mode |

| Use_Authority | 6.3% | 4.1% | Quality_Unspecified |

| Quality_Effect | 6.2% | 3.9% | Use_Frequency |

| Quality_Quantity | 3.9% | ||

| System_Nature, Authority_Grammar, Use_Historical, System_Unspecified | 2 to 3% | 2 to 3% | Authority_Grammar, Authority_Dictionary, Quality_Logic, System_History |

| Variety_Genre, Authority_Unspecified, Use_Bible, Variety_Geographic | 1 to 2% | 1 to 2% | Variety_Geographic, Purity_Gallicism, Variety_Register, System_Unspecified, Authority_Unspecified, Quality_Quantity, Purity_Anglicism, Authority_Freq, System_Nature |

| Purity_Unspecified, Quality_Care, System_Immutable, Optional variation (see note 4), Quality_Ease, Use_Socio, Purity_Latinism, Authority_Frequency, Use_Unspecified, Variety_Mode, Quality_Logic, Purity_Gallicism | <1% | <1% | Authority_Socio, Authority_Literary, Purity_Other_Language, Use_Socio, Use_Unspecified, Variety_Unspecified, System_Standard, Quality_Beauty, Other argument, Quality_Care |

| Authority_Dictionary, Authority_Literary, Authority_Socio, Purity_Anglicism, Purity_Germanism, Purity_Other_Language, Quality_Unspecified, Variety_Register, Variety_Standard, Variety_Unspecified,Other argument | NA | NA | Purity_Latinism, Quality_Differentiation, Quality_Ease, System_Analogy (and all its subtypes), System_Immutable, Use_Authority, Use_Bible, Variety_Genre (, Ipse dixit) (see note 4) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Vos, M. In Between Description and Prescription: Analysing Metalanguage in Normative Works on Dutch 1550–1650. Languages 2022, 7, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020089

de Vos M. In Between Description and Prescription: Analysing Metalanguage in Normative Works on Dutch 1550–1650. Languages. 2022; 7(2):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020089

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Vos, Machteld. 2022. "In Between Description and Prescription: Analysing Metalanguage in Normative Works on Dutch 1550–1650" Languages 7, no. 2: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020089

APA Stylede Vos, M. (2022). In Between Description and Prescription: Analysing Metalanguage in Normative Works on Dutch 1550–1650. Languages, 7(2), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020089