The Sociolinguistics of Quotatives in Sri Lankan English: Corpus-Based Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Quotatives in World Englishes

- (1)

- they might would probably ask me that okay (,) fine, ‘I need five thousand rupees’. (HCNVE-India IE35; Davydova, 2016, p. 185)

- (2)

- So that used to be okay (,) fine, ‘We are sitting in an English class’. (HCNVE-India IE35; Davydova, 2016, p. 185)

- (3)

- (4)

- the guinea pig ask me say ah but where is the surgical knife <ICE-GHA:S1A-015> (Hansen, 2021, p. 38)

2.2. Sri Lankan English

- (5)

- He called to tell he might be getting late kiyala.

- (6)

- Customer is going abroad kiyala.

- Which forms are used as quotatives in SLE and how frequent are they?

- Which structural and sociobiographic factors significantly influence quotative choices in SLE and what effects do these factors exert?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Corpus Data

3.2. Data Extraction and Annotation

- person_subject encodes the person of the grammatical subject of the quotative. In absolute frequencies, there were 151 first-person, 12 second-person, and 248 third-person subjects. As the number of 12 second-person subjects appeared too low to constitute a variable level in its own right, first- and second-person subjects are treated collectively in the variable level non-third, which contrasts with the variable level third. Third-person subjects have a tendency to be realised with BE like (58.87%; 146 out of 248 examples), but this tendency is even stronger for non-third-person subjects (71.17%; 116 out of 163 examples).

- content_quote captures the nature of the quoted material. Oral stands for quoted speech (e.g., she said I smiled because I was embarrassed <ICE-SL:S1A-003#108:1:B>), mental for the re-creation of imagined content as well as feelings, i.e., generally material that was previously not explicitly uttered (e.g., I felt like okay if I was meeting you guys I would have kept a bit of time <ICE-SL:S1A-084#90:1:B>), and indigenous for passages—explicitly uttered or not—using predominantly Sinhala or Tamil instead of English (e.g., he’s asking uh ewunata aunty hadanawada coffee <ICE-SL:S1A-003#143:1:B>). Indigenous material is always accompanied by BE like (100%; 12 out of 12 examples) while mental (84.85%; 28 out of 33 examples) and oral material (60.66%; 222 out of 366 examples) also shows a preference for BE like.

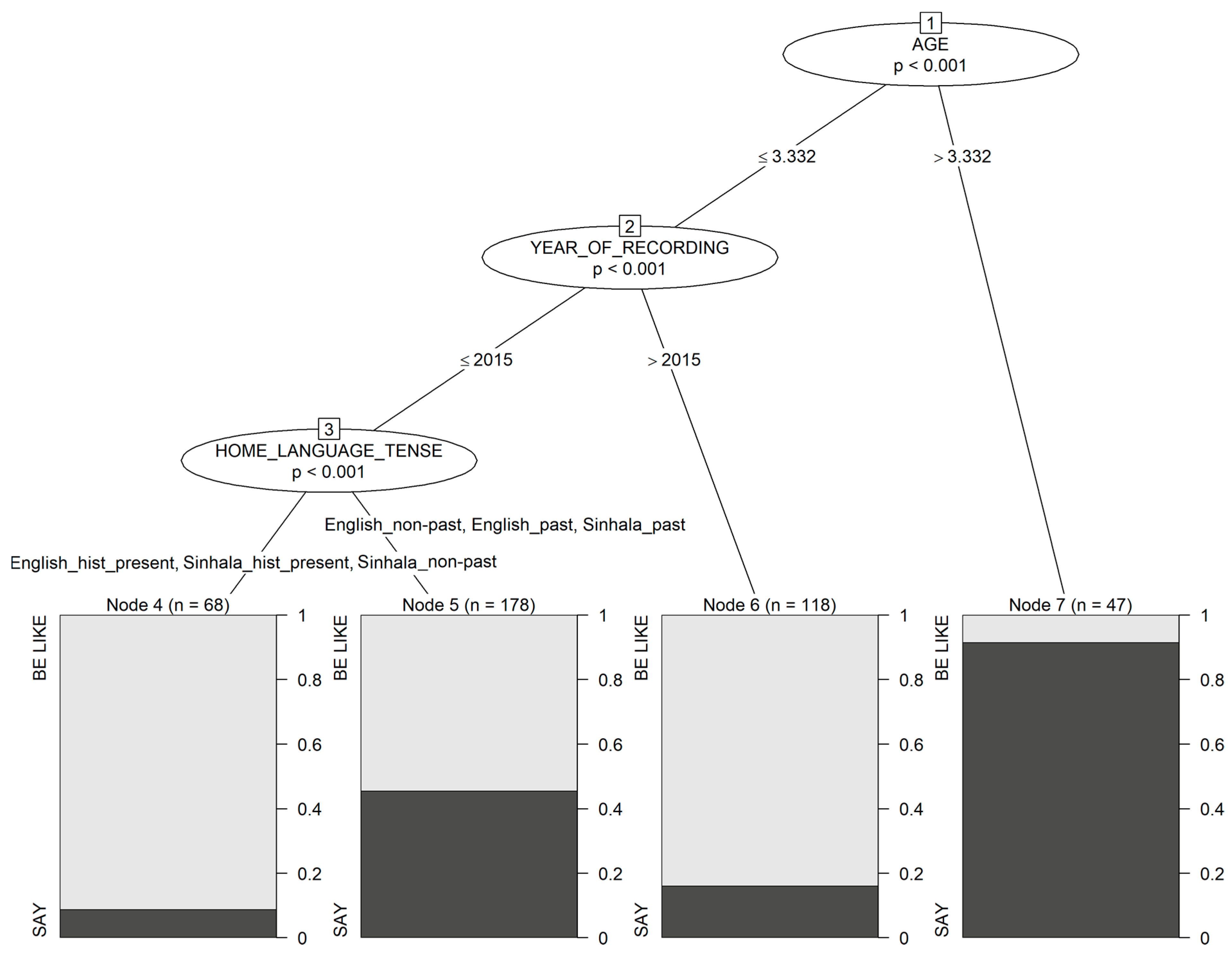

- tense encodes the tense of the verb phrase in which the quotative occurs. The levels of tense are past, historical present, and non-past, which includes present and future tense, the latter of which was only attested in two cases and was thus combined with the present-tense cases into one level. Modal verbs occurred extremely rarely in the data and have been assigned to tense categories based on their morphological realisation and context, but do not—because of their low frequencies of occurrence—constitute a category in their own right. Corpus examples were considered instances of historical present when the quotative occurred in present tense in an otherwise past-tense narrative. In case the tense is historical present, BE like (95.38%; 62 out of 65 examples) is the dominant choice. In non-past (60.87%; 42 out of 69 examples) and past (57.04%; 158 out of 277 examples) contexts, BE like is still dominant, but not as prevalent as in the historical present.

- quote_length documents the logged length of the quoted material in number of words. Quotations introduced with BE like are on average slightly shorter (mean = 1.67, sd = 0.86) than those introduced by SAY (mean = 1.7, sd = 0.94).

- number_subject documents whether the grammatical subject of the quotative is singular or plural. Both singular (62.91%; 229 out of 364 examples) and plural (70.21%; 33 out of 47 examples) subjects show a tendency towards BE like.

- age represents the logged speaker age when the quotative was produced. On average, speakers are younger when they use BE like (mean = 3.13 (22.87 non-log-transformed age), sd = 0.12) than when they use SAY (mean = 3.36 (28.79 non-log-transformed age), sd = 0.45). The non-log-transformed age values range from 18 to 73.

- education is a variable with three levels: GCE, BA, and BA+. GCE stands for speakers whose highest educational qualification is the General Certificate of Education (GCE). The GCE Ordinary Level is usually awarded in Sri Lanka over the course of grades 10 and 11 of senior secondary school and the GCE Advanced Level during grades 12 and 13 at collegiate school level. The variable level GCE thus captures speakers with their highest academic achievement at the advanced school level. BA stands for speakers with a BA university degree and BA+ for speakers with more advanced university degrees such as a Master’s or a PhD. Across these educational levels, BE like (GCE = 61.38% (116 out of 189 examples), BA = 65.91% (116 out of 176 examples), BA+ = 65.22% (30 out of 46 examples)) is consistently more frequent than SAY.

- ethnicity captures the ethnic group corpus speakers identify with. The majority of corpus speakers are Sinhalese (68.17%), 15.33% are Tamil, and the remaining corpus speakers belong to other ethnic groups (16.55%). The Sinhalese (67.86%; 190 out of 280 examples) and speakers of other (67.65%; 46 out of 68 examples) ethnic belonging tend towards BE like, whereas Tamil speakers prefer SAY (58.73%; 37 out of 63 examples).

- gender encodes the gender group the informants associate themselves with. Female corpus speakers’ preferred quotative choice is BE like (68.65%; 219 out of 319 examples), while male corpus speakers display a slight tendency towards SAY (53.26%; 49 out of 92 examples).

- home_language describes the language that corpus speakers profiled as the language predominantly used in their homes. Speakers with English (62.44%; 128 out of 205 examples) or Sinhala (73.33%; 132 out of 180 examples) as the main language at home employ BE like more often than SAY, while SAY (92.31%; 24 out of 26 examples) is particularly dominant when Tamil is the home language.

- ame_media_frequency describes whether corpus speakers consume American English media on a daily or non-daily basis. While BE like is preferred under both conditions, daily consumers of American English have a stronger inclination towards BE like (67.07%; 167 out of 249 examples) than non-daily consumers (58.64%; 95 out of 162 examples).

- bre_media_frequency captures whether corpus speakers expose themselves to British English media on a daily or non-daily basis. BE like is the dominant variant in both cases, with daily consumers of British English displaying slightly lower frequencies of BE like (62.28%; 175 out of 281 examples) than non-daily consumers (66.92%; 87 out of 130 examples).

- occupation classifies the corpus speakers into three groups, that is people with a non-teaching profession in contrast to teachers and students. The preference for BE like is strongest with students (70.79%; 206 out of 291 examples), but also notable with teachers (68.75%; 22 out of 32 examples). In contrast, speakers with a non-teaching profession prefer SAY (61.36%; 54 out of 88 examples) over BE like.

- year_of_recording documents the year in which the quotative was produced to potentially observe a change in quotative preference in the course of the compilation period of ICE-SL. On average, BE like is employed later (mean = 2014.73, sd = 1.68) than SAY (mean = 2014.52, sd = 1.63).

- stays_abroad describes whether a corpus speaker spent more than six months at a time outside Sri Lanka. Corpus speakers without a stay abroad prefer BE like (69.02%; 205 out of 297 examples) while speakers with a stay abroad use BE like (50%; 57 out of 114 examples) and SAY (50%; 57 out of 114 examples) equally often.

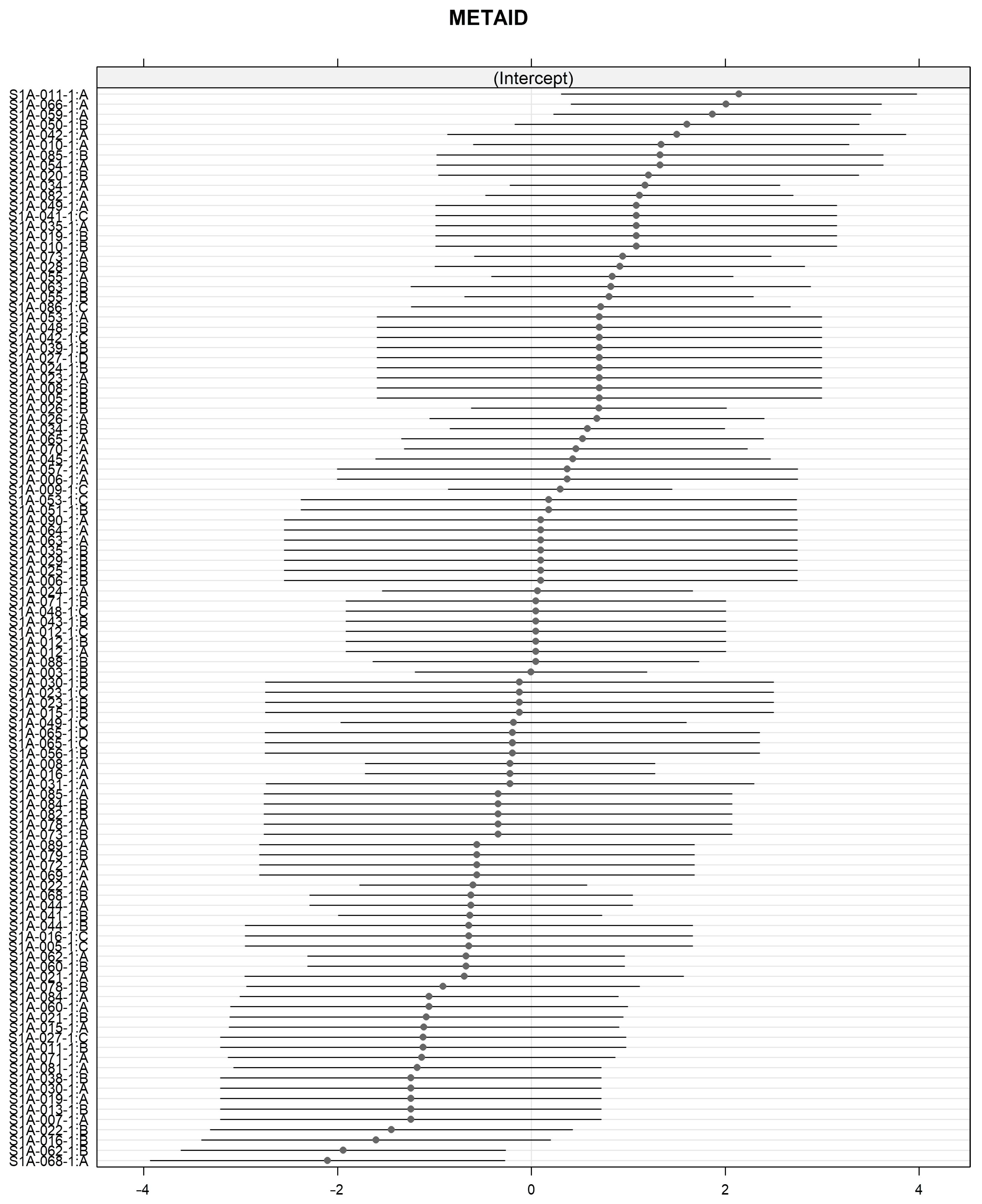

3.3. Statistical Modelling

4. Results

4.1. Quotatives in Sri Lankan English

- (7)

- <ICE-SL:S1A-060#284:1:A> So tenth season they were like if you want us to do it you have to pay us

- (8)

- <ICE-SL:S1A-001#191:1:A> I said that is the trend then you know this is not a new one

- (9)

- <ICE-SL:S1A-071#417:1:B> One day she just told me you know you don’t ask for permission anymore

- (10)

- <ICE-SL:S1A-053#6:1:C> He he asked me can I get a photocopy of this to keep

- (11)

- <ICE-SL:S1A-007#219:1:B> And then yeah I thought she’ll come at around six-thirty

- (12)

- <ICE-SL:S1A-034#226:1:B> Or he’ll say okay I’ll drop you home<ICE-SL:S1A-034#227:1:B> He lives close by<$A><ICE-SL:S1A-034#228:1:A> Ahh in Dehiwala<$B><ICE-SL:S1A-034#229:1:B> [zero] So I’ll pick you in the morning on the way to work you can tell me about it<$A><ICE-SL:S1A-034#230:1:A> but that’s good so you get a ride to work

- (13)

- <ICE-SL:S1A-025#164:1:B> On his one knee <,> goes down on one knee and proposes to her like <,> and she goes oh my god oh my god you know the usual

- (14)

- <$B><ICE-SL:S1A-003#280:1:B> Not sad she gets all <O>imitation</O><ICE-SL:S1A-003#281:1:B> Child you haven’t eaten

- (15)

- <$A><ICE-SL:S1A-015#242:1:A> then she was like I don’t know <O>imitation</O><ICE-SL:S1A-015#243:1:A> And now they’re all on texting terms and everything

- (16)

- <ICE-SL:S1A-010#266:1:B> Ama didn’t say I mean Ama said that you know <,,><ICE-SL:S1A-010#267:1:B> I don’t think it’s going to go the way I was thinking it’ll go

- (17)

- <ICE-SL:S1A-070#87:1:A> I asked him that <,,> tch <,,> where are you

- (18)

- Nimal - kiuwa - [Ravi- ka:reka - seeduwa - kiyala]N(NOM) - said - [Ravi(NOM) - car - washed - COMP]‘Nimal said that Ravi washed the car.’ (Ananda, 2011, p. 84)

- (19)

- oya dannawada eya kiwwa ‘you look gorgeous’ kiyala (Wickramasinghe, 2024, p. 20)

- (20)

- <ICE-SL:S1A-019#149:1:A> So I thought I’ll join the next <,> round kiyala

- (21)

- <ICE-SL:S1A-022#166:1:A> So they were like do that if you want kiyala

4.2. Quotatives BE like vs. SAY in Sri Lankan English

- (22)

- <$B><ICE-SL:S1A-016#325:1:B> It was <,> okay it was just after Jaff I mean during camp no<$A><ICE-SL:S1A-016#326:1:A> Ahh they would have met up afterwards<$B><ICE-SL:S1A-016#327:1:B> Yeah they met <,> April eighteenth they met and by that time nangi also told Arshada<ICE-SL:S1A-016#328:1:B> Then Arshada is like I can’t wait without telling when we meet

- (23)

- <ICE-SL:S1A-019#228:1:B> I told him <,> if you want go for classes and I said <,> even if I ask him do it in Sinhala I don’t have Sinhala notes no

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EFL | English as a Foreign Language |

| ESL | English as a Second Language |

| ICE-SL | The Sri Lankan Component of the International Corpus of English |

| SAVE | The South Asian Varieties of English Corpus |

| SAVE2020 | The 2020 update of the South Asian Varieties of English Corpus |

| SLE | Sri Lankan English |

| 1 | For comprehensive overviews of research on SLE, please consult Meyler (2013) or Ekanayaka (2020). For detailed descriptions of the history of (English in) Sri Lanka, please refer to de Silva (1981), Yogasundram (2008) or Coperahewa (2009). |

| 2 | Please note the critical discussion of GloWbE in the World Englishes community—also with regard to the Sri Lankan data available there (Mukherjee, 2015). |

| 3 | Earlier research on quotatives in World Englishes as presented in Section 2.1 has habitually contrasted the use of BE like with all other quotative forms found in the datasets under scrutiny. This paper departs from this approach in that it explicitly zooms in on the choice between the quotatives BE like and SAY in SLE since (a) they together constitute the vast majority of quotative forms in SLE (80.39%) and (b) SAY—with a relative frequency of 28.14%—appears too frequently in comparison to the other rarer quotative forms, which individually are all below relative frequencies of 7%, to group them together because it would mask the dominance of and the primary applicability of results to SAY in this group. |

References

- Ananda, M. G. L. (2011). Complementizer distribution in Sinhala. Vidyodaya Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 3, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, F. (2005). Quotative use in American English: A corpus-based, cross-register comparison. Journal of English Linguistics, 33(3), 222–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, F. (2009). Quotative be like in American English: Ephemeral or here to stay? English World-Wide, 30(1), 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaisch, T. (2015). The lexis and lexicogrammar of Sri Lankan English. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaisch, T. (2022). Comparing generalised linear mixed-effects models, generalised linear mixed-effects model trees and random forests: Filled and unfilled pauses in varieties of English. In O. Schützler, & J. Schlüter (Eds.), Data and methods in corpus linguistics: Comparative approaches (pp. 163–193). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernaisch, T. (in press). Sri Lankan English. In R. Hickey (Ed.), The new Cambridge history of the English language. Cambridge University Press.

- Bernaisch, T., Heller, B., & Mukherjee, J. (2021). Manual for the 2020-update of the South Asian varieties of English (SAVE2020) corpus. Version 1.1. Department of English, Justus Liebig University. [Google Scholar]

- Bernaisch, T., Koch, C., Mukherjee, J., & Schilk, M. (2011). Manual for the South Asian varieties of English (SAVE) corpus: Compilation, cleanup process, and details on the individual components. Justus Liebig University, Department of English. [Google Scholar]

- Bernaisch, T., Mendis, D., & Mukherjee, J. (2019). Manual to the international corpus of English—Sri Lanka. Department of English, Justus Liebig University. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth, C. J., Recktenwald, S., & Wang, J. (1990). I’m like, “Say what?!”: A new quotative in American oral narrative. American Speech, 65(3), 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogetić, K. (2014). Be like and the quotative system of Jamaican English: Linguistic trajectories of globalization and localization. English Today, 30(3), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, W., & Bernaisch, T. (2025). Social network effects on particle variation among Singapore students. World Englishes, 44(1–2), 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchstaller, I. (2006). Diagnostics of age-graded linguistic behaviour: The case of the quotative system. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 10, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchstaller, I. (2008). The localization of global linguistic variants. English World-Wide, 29(1), 15–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchstaller, I., & D’Arcy, A. (2009). Localized globalization: A multi-local, multivariate investigation of quotative be like. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 13(3), 291–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchstaller, I., Rickford, J., Traugott, E., Wasow, T., & Zwicky, J. (2010). The sociolinguistics of a short-lived innovation: Tracing the development of quotative all across spoken and internet newsgroup data. Language Variation and Change, 22, 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butters, R. (1980). Narrative go “say”. American Speech, 55, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butters, R. (1982). Editor’s note. American Speech, 57, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, J., Kerswill, P., Fox, S., & Torgersen, E. (2011). Contact, the feature pool and the speech community: The emergence of multicultural London English. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 15, 151–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coperahewa, S. (2009). The language planning situation in Sri Lanka. Current Issues in Language Planning, 10(1), 69–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcy, A. (2010). Quoting ethnicity: Constructing dialogue in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 14(1), 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcy, A. (2012). The diachrony of quotation: Evidence from New Zealand English. Language Variation and Change, 24(3), 343–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcy, A. (2013). Variation and change. In R. Bayley, R. Cameron, & C. Lucas (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of sociolinguistics (pp. 484–502). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- D’Arcy, A. (2015). Quotation and advances in understanding syntactic systems. Annual Review of Linguistics, 1, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M. (2013). Corpus of global web-based English. Available online: https://www.english-corpora.org/glowbe/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Davies, M. (2016). Corpus of news on the web (NOW). Available online: https://www.english-corpora.org/now/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Davydova, J. (2016). Indian English quotatives in a diachronic perspective. In E. Seoane, & C. Suárez-Gómez (Eds.), World Englishes: New theoretical and methodological considerations (pp. 173–204). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, J. (2019). Quotation in indigenised and learner English: A sociolinguistic account of variation. De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, J. (2021). The role of sociocognitive salience in the L2 acquisition of structured variation and linguistic diffusion: Evidence from quotative be like. Language in Society, 50(2), 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, J. (2025). Parentheticals in spoken Indian and Sri Lankan English. World Englishes, 44(1–2), 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Silva, K. M. (1981). A history of Sri Lanka. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deuber, D., Hänsel, E. C., & Westphal, M. (2021). Quotative be like in Trinidadian English. World Englishes, 40(3), 436–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DHLab—Department of English. (2022). The Sri Lanka English newspaper corpus 1.0. University of Colombo. Available online: https://dhlab.cmb.ac.lk/slenc (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Ekanayaka, T. N. I. (2020). Sri Lankan English. In K. Bolton, W. Botha, & A. Kirkpatrick (Eds.), The handbook of Asian Englishes (pp. 337–353). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, K., & Bell, B. (1995). Sociolinguistic variation and discourse function of constructed dialogue introducers: The case of be + like. American Speech, 70(3), 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokkema, M., Smits, N., Zeileis, A., Hothorn, T., & Kelderman, H. (2018). Detecting treatment-subgroup interactions in clustered data with generalized linear mixed-effects model trees. Behavior Research Methods, 50(5), 2016–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S. (2012). Performed narrative: The pragmatic function of this is + speaker and other quotatives in London adolescent speech. In I. Buchstaller, & I. van Alphen (Eds.), Quotatives: Cross-linguistic and cross-disciplinary perspectives (pp. 213–257). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gair, J. W. (1970). Colloquial Sinhalese grammar and clause structure. Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, S. (1996). Introducing ICE. In S. Greenbaum (Ed.), Comparing English worldwide: The international corpus of English (pp. 3–12). Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Gries, S. T. (2020). On classification trees and random forests in corpus linguistics: Some words of caution and suggestions for improvement. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistics Theory, 16(3), 617–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, S. T., & Bernaisch, T. (2016). Exploring epicentres empirically: Focus on South Asian Englishes. English World-Wide, 37(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunesekera, M. (2005). The postcolonial identity of Sri Lankan English. Katha Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, B. (2021). Localisation, globalisation and gender in discourse-pragmatic variation in Ghanaian English. In T. Bernaisch (Ed.), Gender in world Englishes (pp. 23–46). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hothorn, T., & Zeileis, A. (2015). partykit: A modular toolkit for recursive partytioning in R. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 16, 3905–3909. [Google Scholar]

- Höhn, N. (2012). “And they were all like ‘What’s going on?’”: New quotatives in Jamaican and Irish English. In M. Hundt, & U. Gut (Eds.), Mapping unity and diversity world-wide: Corpus-based studies of New Englishes (pp. 263–290). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M. (1999). Ghanaian Pidgin English in its West African context: A sociohistorical and structural analysis. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundt, M., Dallas, B., & Nakanishi, S. (2024). The be- versus get-passive alternation in world Englishes. World Englishes, 43(1), 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortmann, B., Lunkenheimer, K., & Ehret, K. (Eds.). (2020). The electronic world atlas of varieties of English. Zenodo. Available online: http://ewave-atlas.org (accessed on 21 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Meyerhoff, M. (2003). Formal and cultural constraints on optional objects in Bislama. Language Variation and Change, 14, 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyler, M. (2007). A dictionary of Sri Lankan English. Mirisgala. [Google Scholar]

- Meyler, M. (2013). Sri Lankan English. In B. Kortmann, & K. Lunkenheimer (Eds.), The mouton world atlas of variation in English (pp. 540–547). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, J. (2015). Response to mark Davies and Robert Fuchs: Expanding horizons in the study of World Englishes with the 1.9 billion word global web-based English corpus (GloWbE). English World-Wide, 36(1), 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, G. (1996). The design of the corpus. In S. Greenbaum (Ed.), Comparing English worldwide: The international corpus of English (pp. 27–35). Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Rautionaho, P., & Hundt, M. (2021). Primed progressives? Predicting aspectual choice in World Englishes. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory, 18(3), 599–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rickford, J. R., Wasow, T., Zwicky, A., & Buchstaller, I. (2007). Intensive and quotative all: Something old, something new. American Speech, 83, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E. W. (2007). Postcolonial English: Varieties around the world. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Senaratne, C. D. (2009). Sinhala-English code-mixing in Sri Lanka: A sociolinguistic study. LOT. [Google Scholar]

- Singler, J. V. (2001). Why you can’t do a VARBRUL study of quotatives and what such a study can show us. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 7(3), 257–278. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, S., & D’Arcy, A. (2004). He’s like, she’s like: The quotative system in Canadian youth. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 8(4), 493–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, S., & D’Arcy, A. (2007). Frequency and variation in the community grammar: Tracking a new change through the generations. Language Variation and Change, 19(2), 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, S., & Hudson, R. (1999). Be like et al. beyond America: The quotative system in British and Canadian youth. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 3(2), 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, S. T. A. (2024). Sinhala-English code-switching in text messaging: A study based on undergraduates of two state universities in Sri Lanka. In 5th SLIIT International Conference on Advancements in Sciences and Humanities (pp. 196–201). Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology, Faculty of Humanities and Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, R. (2009). Multidimensional analysis and the study of world Englishes. World Englishes, 28(4), 421–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogasundram, N. (2008). A comprehensive history of Sri Lanka: From prehistory to tsunami (2nd ed.). Vijitha Yapa Publications. [Google Scholar]

| Höhn (2012) on BE like and SAY in Irish and Jamaican English | D’Arcy (2013) on BE like in Hong Kong, Kenyan, Philippine, and Singapore English | Bogetić (2014) on BE like in Jamaican English | Davydova (2016) on BE like and SAY in Indian English | Davydova (2019) on BE like in Indian English | Davydova (2021) on BE like in Indian English and English in Germany | Deuber et al. (2021) on BE like in Trinidadian English | Hansen (2021) on BE like in Ghanaian English | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STRUCTURAL PREDICTORS | ||||||||

| Mimesis | ✓+ | ✓+ | ||||||

| Person of grammatical subject | ✓+ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓+ | ✓+ | ✓+ | ✓ | |

| Quoted material | ✓+ | ✓ | ✓+ | ✓+ | ✓+ | ✓+ | ✓+ | |

| Tense | ✓+ | ✓+ | ✓+ | ✓+ | ✓+ | |||

| SOCIOBIOGRAPHIC PREDICTORS | ||||||||

| Age | ✓+ | ✓+ | ✓+ | |||||

| Education | ✓+ | |||||||

| Gender | ✓+ | ✓+ | ✓ | ✓+ | ✓+ | |||

| Language context | ✓ | |||||||

| Media exposure | ✓ | |||||||

| Occupation | ✓+ | |||||||

| Region | ✓ | |||||||

| Time | ✓+ | ✓ | ||||||

| Quotative | Absolute Frequency | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| BE like | 325 | 52.25% |

| SAY | 175 | 28.14% |

| TELL | 38 | 6.11% |

| ASK | 32 | 5.14% |

| THINK | 23 | 3.7% |

| zero | 14 | 2.25% |

| GO | 4 | 0.64% |

| Other | 11 | 1.77% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernaisch, T. The Sociolinguistics of Quotatives in Sri Lankan English: Corpus-Based Insights. Languages 2025, 10, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090236

Bernaisch T. The Sociolinguistics of Quotatives in Sri Lankan English: Corpus-Based Insights. Languages. 2025; 10(9):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090236

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernaisch, Tobias. 2025. "The Sociolinguistics of Quotatives in Sri Lankan English: Corpus-Based Insights" Languages 10, no. 9: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090236

APA StyleBernaisch, T. (2025). The Sociolinguistics of Quotatives in Sri Lankan English: Corpus-Based Insights. Languages, 10(9), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090236