3.2.1. Modals Within vP

To begin with, we will discuss modal elements that appear within

vP. We will first introduce

Rudin (

2019)’s discussion on modal verbs in German, and discuss his response to the data and its conceptual problem for his proposed licensing condition for sluicing. We will then discuss a novel set of data from Japanese concerning directive sentences, which will turn out to give rise to the same problem as German modal verbs.

Let us first discuss German. In German, modals appear as verbs in sentences, unlike in English, where a modal appears on T (e.g., (4)). This means that in German a modal is accompanied by an independent

vP. Recall here that, according to

Rudin (

2019)’s licensing condition for sluicing, an element cannot be freely deleted under sluicing if it is within the highest

vP. It is then predicted that German modal verbs cannot be mismatched under sluicing.

Rudin (

2019) observes, however, that this prediction is not borne out; mismatches of modal verbs are possible in German, as shown in (16), which he credits to Andreas Walker p.c.

| (16) | ![Languages 10 00237 i007 Languages 10 00237 i007]() |

| ‘This was a problem that physics had to solve, but for a long time it wasn’t clear how.’ |

| | | (Rudin, 2019, p. 271) |

To capture this observation, Rudin revises the definition of the eventive core in (8) and presents (17).

| (17) | Eventive core (final definition) |

| | The eventive core of a clause is its highest vP that is associated with an event-introducing predicate. |

| | (Rudin, 2019, p. 271) |

Rudin notes that modal verbs are not event-introducing predicates, given that they “only communicate something about the modal status of their prejacent proposition [and] thus they are parasitic on the event introduced by the matrix verb of that prejacent” (

Rudin, 2019, p. 271). Hence, in (16), the modal verb in the elided clause is outside of the eventive core, or

vP associated with the event-introducing predicate

lösen ‘solve’, and thus can be freely deleted. This solution is not without any problems, however. Notice in particular that the revised definition of the eventive core (17) draws on the semantic notion “an event-introducing predicate”. This seems to be incongruent with

Rudin (

2019)’s original intention to propose a

syntactic licensing condition for sluicing. In fact, Rudin himself makes a remark on this point in a footnote.

5 To add to this conceptual problem, below we will discuss novel data regarding directive sentences in Japanese.

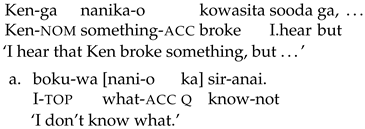

Consider next Japanese directive sentences. In Japanese, there are several typical expressions that show directive speech acts. Here we will focus on two such expressions. One is imperatives, where an imperative morpheme is attached to a verb stem. Ref. (18) shows two examples of Japanese imperatives.

| (18) | ![Languages 10 00237 i008 Languages 10 00237 i008]() |

As (18) shows, the imperative morpheme has two allomorphs: One is -e, which is used when a verb stem ends with a consonant (e.g., (18a)), while the other is -ro, which is appended to vowel-ending verb stems (e.g., (18b)). Another expression that shows a directive speech act is sentences with yooni, which follows a verb with the present tense. We will refer to this type of expression as a yooni-sentence. Ref. (19) shows examples of yooni-sentences.

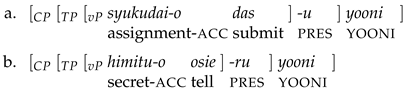

| (19) | ![Languages 10 00237 i009 Languages 10 00237 i009]() |

To discuss the crucial data involving these two directive expressions, we will now establish the assumptions of their syntax and semantics. Concerning the syntax, notice that the two expressions differ in what element the relevant morphemes follow. On the one hand, imperative morphemes are attached to verb stems, as observed in (18); they cannot be appended to tensed predicates, as (20) shows (

Saito, 2015).

| (20) | ![Languages 10 00237 i010 Languages 10 00237 i010]() |

With the plausible assumption that a verb stem composes

vP with its arguments, the above morphological fact suggests that an imperative morpheme merges with

vP. Specifically, we follow

Mihara and Ebara (

2012) and

Mihara (

2015), and assume that an imperative morpheme is an adjunct of

vP (cf.

Saito, 2015). Under this assumption, the examples in (18) can be structurally represented as in (21).

| (21) | ![Languages 10 00237 i011 Languages 10 00237 i011]() |

On the other hand,

yooni follows present-tensed predicates (see (19)), which suggests that the element in question merges with TP. It is then plausible to assume that

yooni is the head of CP; I refer the reader to

Uchibori (

2000) for more discussion on the syntactic status of

yooni as a complementizer. With this assumption, (19) can be structurally represented as in (22).

6| (22) | ![Languages 10 00237 i012 Languages 10 00237 i012]() |

Concerning the semantics, we will adopt the modal-based analysis of imperatives proposed by

Schwager (

2006)/

Kaufmann (

2012), according to which imperatives involve a special necessity modal called an

imperative modal. A more detailed definition of this modal will be provided in the next section. Here, we assume that the directive force of imperatives and

yooni-sentences in Japanese derive from the special necessity modal in them and that that modal is encoded in the imperative morpheme and

yooni respectively (cf.

Ihara & Noguchi, 2018;

Ihara, 2020,

2021). Incidentally, under this assumption, if (i) an imperative or a

yooni-sentence serves as the antecedent clause of sluicing and (ii) the elided clause is interpreted with the meaning of a necessity modal like

must/

should, this sluicing can be viewed to involve a matching with respect to a modal element (

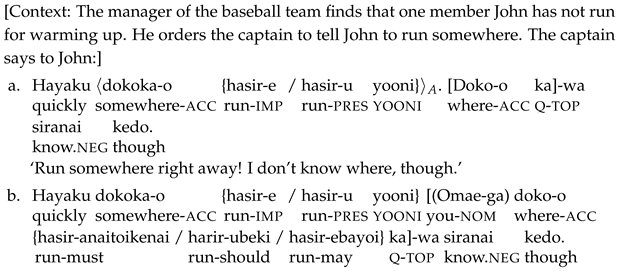

Noguchi & Ihara, 2020). The relevant example is shown in (23), where the elided clause in (23a),

doko-o ka ‘where-

acc q’, is interpreted to involve a necessity modal as in (23b).

| (23) | ![Languages 10 00237 i013 Languages 10 00237 i013]() |

With this much background, consider now the predictions that

Rudin (

2019)’s syntactic licensing condition for sluicing makes with regard to the two directive expressions under consideration. Recall that according to Rudin’s proposal, mismatches under sluicing are allowed for elements outside of

vP, but not for those within

vP. It is then predicted that the necessity modal in

yooni-sentences, which appears on C, can be mismatched under sluicing, while the one in imperatives, which occurs within

vP, cannot. To examine whether these predictions are borne out, consider first the baseline example in (24).

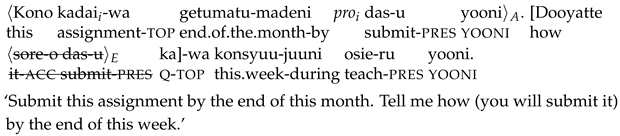

7| (24) | ![Languages 10 00237 i014 Languages 10 00237 i014]() |

Notice in particular that in (24) the embedded wh-question in the second sentence cannot be interpreted with the necessity modal; such an interpretation would make the sentence infelicitous under the given context. This means that if sluicing applies to the embedded wh-question in (24) with the first directive sentence being the antecedent clause, a mismatch will be forced with respect to the modal elements. With this baseline in mind, consider now the two crucial cases that obtain by applying sluicing to (24). The first case is displayed in (25), where the first sentence is the yooni-sentence.

| (25) | [The context is the same as (24):] |

| | ![Languages 10 00237 i015 Languages 10 00237 i015]() |

(25) can be felicitously interpreted. This means that a mismatch is allowed in (25) with respect to the modals. With our assumption that the necessity modal in

yooni-sentences appears at C, this is correctly predicted from

Rudin (

2019)’s syntactic licensing condition on sluicing, according to which elements above

vP can be unconditionally elided. Consider next the second case in (26), where the imperative is used in the first sentence.

8| (26) | [The context is the same as (24):] |

| | ![Languages 10 00237 i016 Languages 10 00237 i016]() |

(26) can be felicitously construed, as (25) can. This means that a mismatch is allowed with respect to the modals in this case as well. Notice, however, that this felicity is not predicted from

Rudin (

2019)’s ‘original’ licensing condition for sluicing, according to which elements within the highest

vP cannot be freely deleted; under our assumption, the necessity modal of imperatives occurs within

vP. In other words, the felicity of (26) brings the same conceptual problem to Rudin’s proposal as modal verbs in German.

3.2.2. Polarity Mismatches in Japanese

The second data that makes dubious

Rudin (

2019)’s licensing condition on sluicing concerns polarity mismatches. An English example of this mismatch is already shown in (5), repeated in (27). (28) exhibits another example from

Kroll (

2019).

| (27) | Mismatches in polarity |

| | 〈Either turn in your final paper〉A by midnight or explain why 〈you didn’t turn it in by midnight〉E! |

| | | (Rudin, 2019, p. 266) |

| (28) | I don’t think that 〈California will comply〉A, but I don’t know why 〈California won’t comply〉E. |

| | (Kroll, 2019, p. 2) |

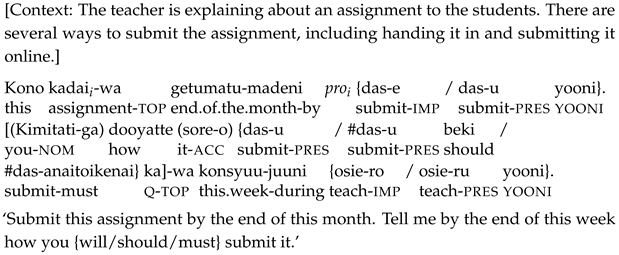

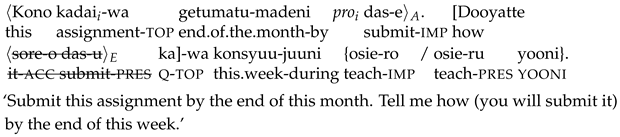

We now observe that polarity mismatches are possible in Japanese as well. See, for example, (29a), whose (possible) interpretation is shown in (29b), with the polarity differing between the antecedent and (prospective) elided clause.

| (29) | ![Languages 10 00237 i017 Languages 10 00237 i017]() |

Recall that according to Rudin’s licensing condition on sluicing, elements outside of vP can be elided without any condition. Hence, his proposal can capture the possibility of mismatches of the polarity, which appears above vP, at least in some languages including English. However, we will show that polarity mismatches in Japanese pose a problem to the licensing condition for sluicing under consideration, in particular by examining the morphology of negation in Japanese.

In Japanese, the negative form of a verb is obtained by attaching -nai ‘not’ to the verb stem. However, if a verb stem ends with a consonant, another exponent -a appears between the verb stem and -nai. See relevant examples in (30).

| (30) | a. | Negative forms of verbs with a vowel-ending stem |

| | tabe-nai ‘not eat’, ne-nai ‘not sleep’, oki-nai ‘not get up’, mi-nai ‘not look’, etc. |

| b. | Negative forms of verbs with a consonant-ending stem |

| | hanas-a-nai ‘not speak’, kik-a-nai ‘not listen’, sitagaw-a-nai ‘not comply’, etc. |

Regarding the exponent

-a, the recent work by

H. Takahashi and Nakajima (

2023) claims that it is the head of

vP. In terms of semantics, they argue that the head of

vP

-a encodes the inchoative aspect, indicating ‘emergence’ or ‘existence’.

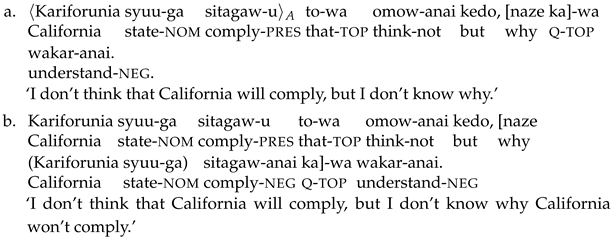

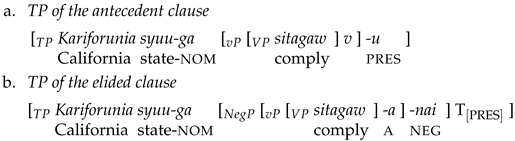

9 With their claim, a negative sentence in Japanese compositionally denotes the negation of the ‘emergence’ or ‘existence’ of the event denoted by VP. For example, consider the negative sentence in (31a), whose syntactic structure is represented in (31b).

| (31) | ![Languages 10 00237 i018 Languages 10 00237 i018]() |

According to the structure in (31b), (31a) is compositionally interpreted as follows: the event of Ken’s drinking beer did not ‘emerge’ or ‘exist’.

Assuming

H. Takahashi and Nakajima (

2023)’s claim regarding the negation in Japanese, let us now turn back to (29a), the example of a polarity mismatch under sluicing in Japanese. Suppose that (29a) is the result of applying sluicing to the embedded

wh-question in (29b). Then, under the current assumption, TP of the antecedent and elided clause can be structurally represented as in (32a) and (32b), respectively.

| (32) | ![Languages 10 00237 i019 Languages 10 00237 i019]() |

Recall that according to

Rudin (

2019)’s licensing condition for sluicing, elements within

vP cannot be elided unconditionally; to be elided, they must have (structure-matching) correlates in the antecedent clause (see (7)–(10)). With this in mind, notice now that the

v,

-a, in (32b) does not have a correlate in (32a), whose

v is distinct from the one in (32b). It is then predicted that sluicing cannot apply to the embedded

wh-question in (29b), which is contrary to fact, as the acceptability of (29a) indicates. This observation thus suggests that Rudin’s licensing condition for sluicing should be reconsidered.

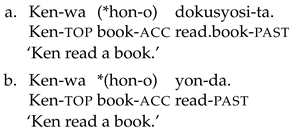

3.2.3. Verb Mismatches

The final data that casts doubt on

Rudin (

2019)’s licensing condition for sluicing involves the deletion of a verb that lexically differs from but is semantically similar to the one in the antecedent clause. More concretely, we will focus on the two verbs:

dokusyosu- ‘read books’ and

yom- ‘read’. They are semantically similar in that they share the meaning of reading. However, they are semantically different in whether they include the meaning of books as the object of reading. This difference is reflected in their syntax;

dokusyosu- cannot take an object while

yom- must, as exemplified in (33).

10| (33) | ![Languages 10 00237 i020 Languages 10 00237 i020]() |

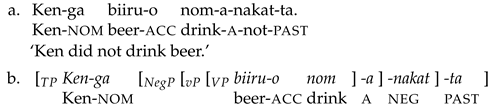

With this syntactic difference in mind, consider now the crucial data in (34a), where sluicing applies to the embedded wh-question in the second sentence.

| (34) | ![Languages 10 00237 i021 Languages 10 00237 i021]() |

According to

Rudin (

2019)’s licensing condition for sluicing, the verb must have a (structure-matching) correlate in the antecedent clause so that it can be deleted under sluicing (see (7)–(10)). It is then expected that in (34a), the verb that is deleted in the embedded

wh-question in the second sentence is

dokushyosu- ‘read books’, which is also used in the antecedent clause. This expectation cannot be correct, however, given that the remnant

wh-phrase in (34a) is an object

wh-phrase;

dokushyosu- cannot take an object, as shown in (34b) (and (33a)). Rather, given the interpretation of the elided clause, the verb that is deleted under sluicing in (34a) should be

yom- ‘read’, which can take an object as shown in (34b) (and (33b)). Therefore, (34a) can be viewed to exemplify a mismatch of verbs under sluicing, which cannot be captured by Rudin’s licensing condition on sluicing. The condition under consideration thus needs to be re-examined.

To recap this section, under the assumption that the licensing condition on sluicing applies to similar constructions in Japanese as well, we have discussed three data sets from Japanese which suggest that

Rudin (

2019)’s syntactic licensing condition on sluicing should be reconsidered; the first data, which concern modals that appear within

vP, point to a conceptual problem of that condition, while the other two, which concern polarity and verb mismatches, provide more serious empirical issues.