Pronoun Mixing in Netherlandic Dutch Revisited: Perception of ‘u’ and ‘jij’ Use by Pre-University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Building Blocks

2.1. Background on Netherlandic Dutch Address Pronouns

| 1. | Ik | weet | wel | dat | jullie | graag | vroeg | vertrekken |

| I | know | PART | that | you.PL | keen | early | depart | |

| maar | zou | je | niet | eerst | even | helpen | opruimen? | |

| But | should | you | not | first | a little bit | help | clean up? | |

| I know that you are keen to leave early, but shouldn’t you help clean up first? | ||||||||

| 2. | Jullie | moeten | zorgen | dat | ze | nu | opgenomen | wordt |

| You.PL | must | ensure | that | she | now | hospitalized | gets | |

| You (pl) have to make sure that she gets hospitalized now. | ||||||||

2.2. Pronoun Mixing in Netherlandic Dutch: Against the Norm but with Potential Pragmatic Benefits

2.2.1. Prescriptive Websites on Pronoun Mixing

| 3. | Het | is | belangrijk | om | consistent | te | zijn | in | je | keuze |

| It | is | important | to | consistent | to | be | in | your.T | choice | |

| It is important to be consistent in your choice | ||||||||||

| (Secretary Plus, 2024) | ||||||||||

| 4. | Wat de keuze ook wordt: voer hem consequent door. Dat is een schone taak voor tekstschrijvers en redacteuren. Zeker als een organisatie de overstap maakt van u naar je, want oude formuleringen blijken nog her en der verstopt te zitten (…) Consequent gebruik geldt overigens alleen binnen dezelfde tekstsoort van een organisatie; niet per se voor alle teksten van die club. Neem bijvoorbeeld een woningcorporatie. Het is heel goed te verdedigen dat die via de website de lezers met je aanspreekt en in brieven kiest voor u. Tenzij het een brief is aan huurders van studentenwoningen. |

| Whatever the choice may be: be consistent. That is a quite a task for copywriters and editors. This is especially the case when an organization changes from you.V to you.T, because old wordings tend to be hidden (…) Being consistent only applies to one text genre in an organization, not necessarily to all texts of that group. Take, for example, a housing cooperative. One could successfully argue that the organization address its readers with you.T on the website and with you.V in letters, unless the letter is written to tenants in student dormitories. | |

| (van Eerd, 2016) | |

| Wat je ook kiest: wees consequent! En misschien wel het allerbelangrijkst: ga geen ‘je’ en ‘u’ door elkaar gebruiken. Welke keuze je ook maakt: voer het consequent door. Niets zo vervelend als een tekst die met ‘u’ begint, verder gaat met ‘je’ en weer eindigt met ‘u’. | |

| Whatever you choose, be consistent! And perhaps most important, don’t go mixing you.T and you.V. Whatever choice you make, apply the choice consistently. Nothing is as annoying as reading a text that begins with you.V, continues with you.T and uses you.V again at the end. | |

| (Letterdesk, 2021) |

| 5. | Online lees je weleens dat het oké is om klanten op de website en via social media aan te spreken met je of jij en bijvoorbeeld bij klachten of een aankoopbevestiging te switchen naar u. Ik vind dit onverstandig omdat het rommelig en wispelturig overkomt. Dus wat je ook kiest, voer de aanspreekvorm consequent door op alle kanalen en in alle geschreven en gesproken communicatie. |

| Sometimes you read online that it is okay to address clients on a website and on social media with je (T) and jij (T) and to switch to u, for example, when there are complaints or when confirming an order. I find this unwise, because it comes across as messy and capricious. So, whatever you choose, be consistent by using the same address term in all written and spoken communication. | |

| https://doorlies.nl/welke-aanspreekvorm-kies-jij/ (accessed on 2 August 2025) |

2.2.2. Pronoun Mixing from a Theoretical Perspective

| 6. | Interview Antoine Bodar (AB) by Colet van der Ven (CV) (taken from Vismans, 2016, p. 125) | |

| CV: | Welkom Antoine Bodar. | |

| ‘Welcome, Antoine Bodar’ | ||

| AB: | Dankuwel. | |

| Thank you(V) | ||

| CV: | We zeggen gewoon je en jou op dit tijdstip van de dag. | |

| We just say you (T subject and object form) at this time of day | ||

| AB: | Oh ja? Zoals u wilt, zoals je wilt. | |

| Is this so? As you (V), as you (T) like | ||

| 7. | Ja, uw waarnemingsvermogen is bijzonder scherp gebleven. |

| Yes, your (v) sentence has remained exquisitely sharp. |

| 8. | Heeft u als directeur dat ook paraat dat soort kennis? |

| Do you (V) as director also have that kind of knowledge at hand? |

3. Study 1 Student Science Project and Categorizing Mixing as Strategic or a Mistake

3.1. Student Science Project

3.2. Participants

3.3. Coding Schema for the Student Science Project

3.4. General Results of Student Science Project

3.5. Folk Linguistics and the Perception of Pronoun Mixing

4. Study 2 Socrative Questionnaire

4.1. Participants

4.2. Socrative Survey

4.3. Procedure

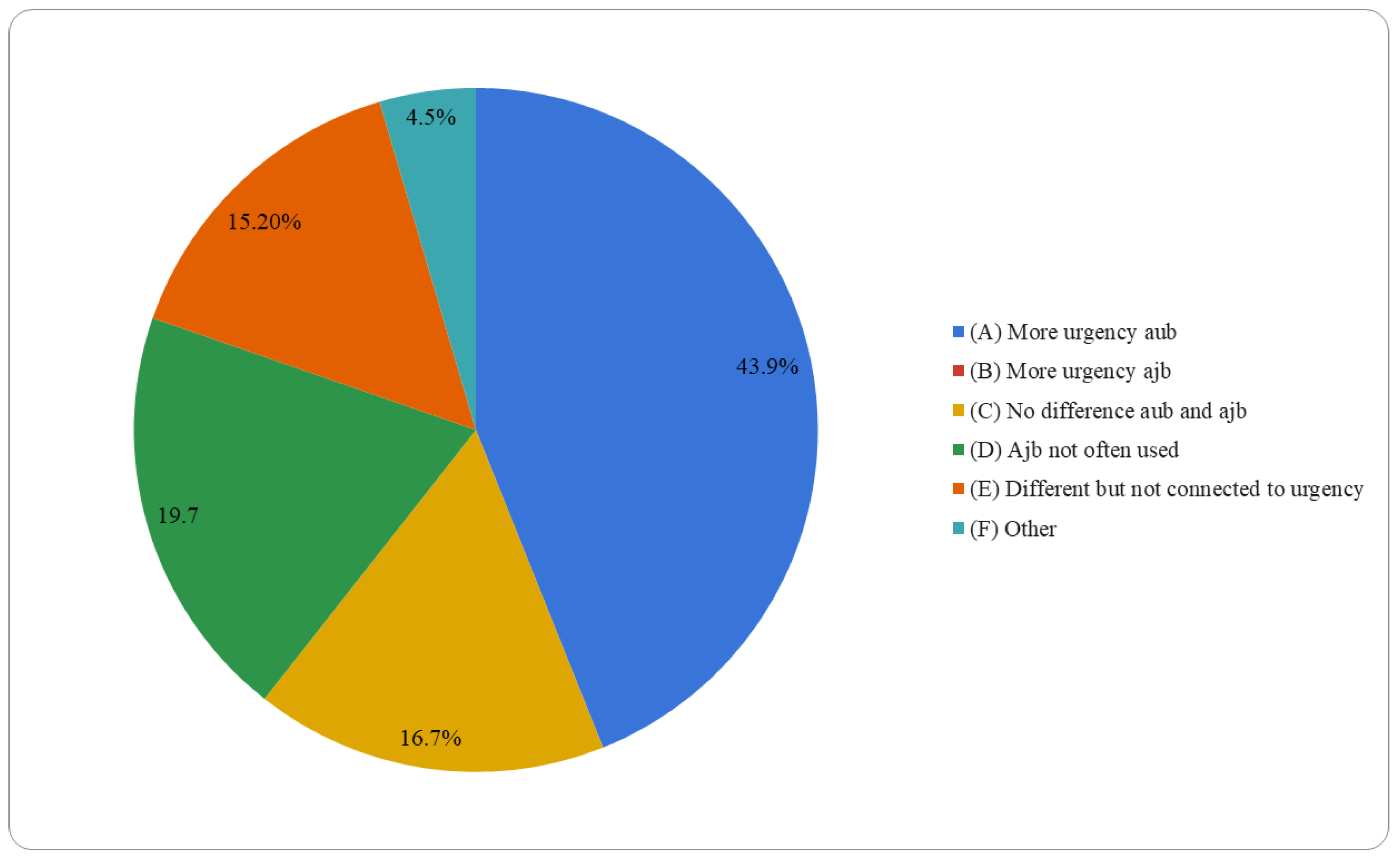

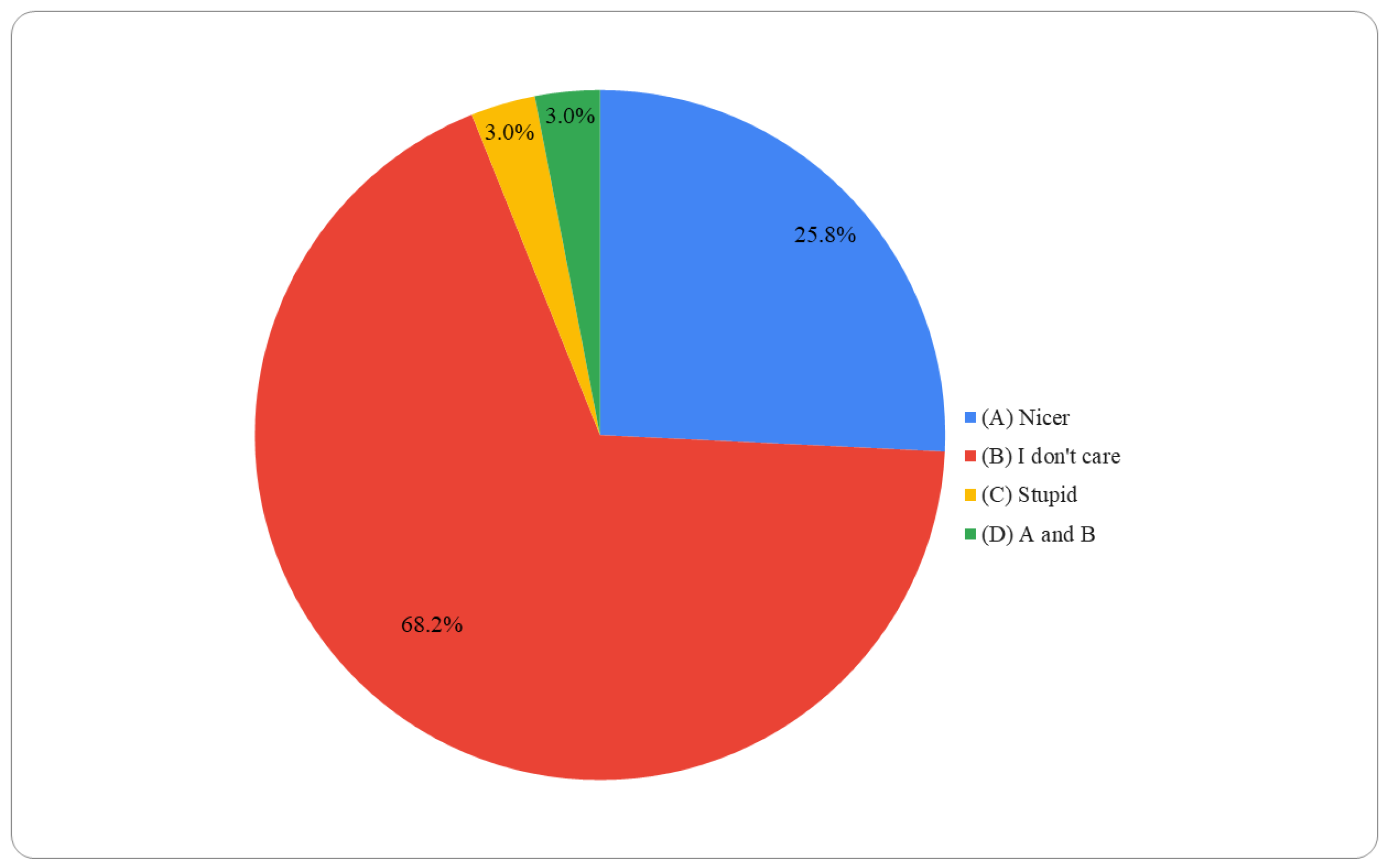

4.4. Open-Ended Questions: General Perception of Pronoun Switching

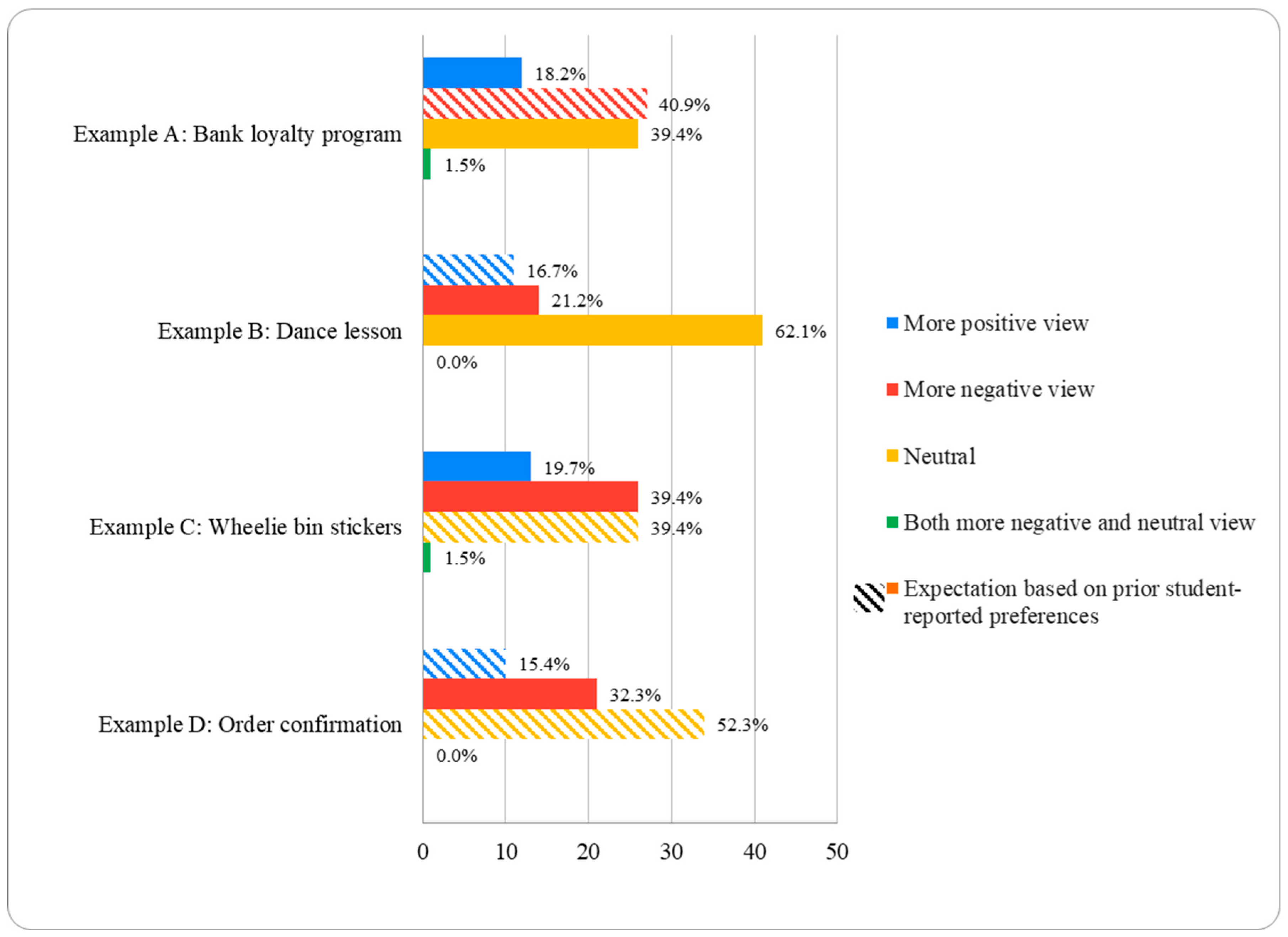

4.5. Perception of Fun and Urgency for V-Use in T-Contexts in Specific Real-World Examples

4.6. Ranking Real-World Examples of Mixing

| 9. | Heb | je | sinds | kort | een | digitale | spiegelreflexcamera | |

| Have | you.T | since | short | a | digital | single-lens reflex camera | ||

| of | wil | je | uw | camera | beter | leren | kennen? | |

| or | want | you.T | your.V | camera | better | learn.INF | know.INF? | |

| ‘Did you.T recently acquire a digital single lens reflex camera or do you.T want to get to know your.V camera better?’ | ||||||||

| 10. | Dance lessons (Example B) | ||||||

| Vink aan | voor | welke | les | je | een | proefles | |

| Select | for | which | lesson | you.T | a | try-out.lesson | |

| wil | aanvragen.(…) | ||||||

| want | apply.INF.(…) | ||||||

| Voor | actuele | tarieven | en | lestijden | kunt | u | |

| For | current | prices | and | lesson.times | can | you.V | |

| terecht | op | onze | website. | ||||

| land | on | our | website. | ||||

| Voor | vragen | kunt | u | contact opnemen | via | (…) | |

| For | questions | can | you.V | contact | via | (…)l. | |

| ‘Choose which time you.T would like to request a try-out lesson. (…) You.V can find current pricing and times on our website. You.V can contact (…) with questions.’ | |||||||

| 11. | ‘Choose which time you.T would like to request a try-out lesson. (…) You.V can find current pricing and times on our website. You.V can contact (…) with questions.’ | |||||

| Wheelie bin sticker ad (Example C) | ||||||

| Maak | uw | kliko | extra | herkenbaar | met | |

| Make | your.V | wheelie bin | extra | recognizable | with | |

| de | Kliko | stickers. | ||||

| the | wheelie bin | stickers. | ||||

| De | uitstekende | kwaliteit | van | de | sticker | |

| The | outstanding | quality | of | the | sticker | |

| zorgt ervoor | ||||||

| ensures | ||||||

| dat | de | stickers | goed | bevestigd | blijven | |

| that | the | stickers | well | attached | stay | |

| op | uw | container. | ||||

| on | your.V | bin. | ||||

| Uw | kliko | is | zodoende | altijd | te | |

| Your.V | wheelie bin | is | thus | always | to | |

| herkennen | in | een | groep | containers, | ||

| recognize | in | a | group | bins, | ||

| met | uw | eigen | persoonlijke | sticker. | ||

| with | your.V | own | personal | sticker. | ||

| Welke | sticker | kies | jij? | |||

| Which | sticker | choose | you? | |||

| ‘Make your.V wheelie bin extra recognizable with the wheelie bin stickers. The outstanding quality of the sticker ensures the stickers remain firmly attached to your bin. Your.V wheelie bin can therefore always be spotted in a group of bins, with your own personal sticker. Which sticker do you.T choose?’ | ||||||

| 12. | Order confirmation (Example D) | |||||||

| Bedankt | voor | uw | aankoop. | |||||

| Thanks | for | your.V | purchase. | |||||

| Wij | sturen | u | een | nieuwe | wanneer | uw | ||

| We | send | you.V | a | new | when | your.V | ||

| bestelling | onderweg | is. | ||||||

| order | underway | is. | ||||||

| Binnenkort | ontvang | je | je | bestelling. | ||||

| Soon | receive | you.T | your.T | order. | ||||

| ‘Thank-you for your.V purchase. We will send you.V a new message when your.V order is on its way. You.T will receive your.T order soon.’ | ||||||||

5. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| # | Question and Answer Options | ||||||||||

| 1 | Wat vond je vóór de les over aanspreekvormen van het mengen van u en je/jij? ‘Before the lesson about forms of address, what did you think of mixing you.V and you.T?’ | ||||||||||

| (Open) | |||||||||||

| 2 | Wat dacht je na de les over aanspreekvormen van het mengen van u en jij? ‘What did you think after the lesson about forms of address mixing you.V and you.T?’ | ||||||||||

| (Open) | |||||||||||

| 3 | Kun je een voorbeeld geven van wanneer het mengen van aanspreekvormen op jou een positief effect heeft? Leg uit waarom. ‘Can you give an example of when mixing forms of address has a positive effect on you? Explain why.’ | ||||||||||

| (Open) | |||||||||||

| 4 | Kun je een voorbeeld geven van wanneer het mengen aanspreekvormen op jou een negatief effect heeft? Leg uit waarom. ‘Can you give an example of when mixing forms of address has a negative effect on you? Explain why.’ | ||||||||||

| (Open) | |||||||||||

| 5 | Sommigen van jullie schreven dat ze tegen vrienden of klasgenoten normaal gesproken je zeggen, maar soms toch danku zeggen. Dat doen ze bijvoorbeeld om diegenen te bedanken voor een antwoord op een huiswerkvraag. Iemand van jullie schreef: “Danku klinkt leuker dan dank je”. Vind jij het inderdaad leuker als iemand danku zegt of schrijft dan dank je? ‘Some of you wrote that you normally say you to friends or classmates, but sometimes say thank-you.V. You do this, for example, to thank those who have answered a homework question. One of you wrote: “Thank-you.V sounds nicer than thank you.T.” Do you indeed like it more when someone says or writes thank-you.V than thank you.T?’ | ||||||||||

| A | Ja, dat vind ik leuker. ‘Yes, I think it is nicer.’ | ||||||||||

| B | Het maakt me niet uit. ‘I don’t care.’ | ||||||||||

| C | Nee, dat vind ik stom. ‘No, I think it is stupid.’ | ||||||||||

| D | A and B | ||||||||||

| 6 | Iemand schreef dat aub misschien gebruikt wordt om duidelijk te maken dat er haast is. Voel jij inderdaad meer haast bij aub? (De hoofdletters in het voorbeeld kun je negeren.) ‘Someone wrote that if you.V please might be used to make it clear that there is urgency. Do you indeed feel more urgency about please? (You can ignore the capital letters in the example.)’ AUB-voorbeeld Whatsapp ‘thank-you.V example Whatsapp’ WIL JIJ AUB KAARTJES KOPEN? ‘WOULD YOU.V PLEASE BUY TICKETS?’ Oke ‘Ok’ Voor twee? ‘For two?’ JAAA ‘YAAAAS’ | ||||||||||

| A | Ja, ik voel meer haast bij aub dan bij ajb. Yes, I feel a stronger sense of urgency with aub than with ajb. | ||||||||||

| B | Nee, ik voel meer haast bij ajb than bij aub. No, I feel more urgency with ajb than with aub. | ||||||||||

| C | Nee, aub en ajb geven voor mij evenveel haast weer, ze hebben op mij verder hetzelfde effect Nee, aub and ajb express the same sense of urgency; they affect me the same way. | ||||||||||

| D | Nee, want ajb komt volgens mij weinig voor, dus ik kan het niet goed vergelijken. No, ajb is used so infrequently that is hard for me to make comparisons. | ||||||||||

| E | Nee, voor mij is er wel een verschil tussen aub en ajb, en ik kom beide vormen tegen, maar dat verschil heeft niets te maken met haast of urgentie. No, I think aub and ajb are different, and I encounter both, but the difference is not related to a sense of urgency. | ||||||||||

| F | Other | ||||||||||

| 7 | Door deze mengvorm denk ik postiever/negatiever over de afzender dan als er geen mengvorm was gebruikt. This case of mixing makes me think more positively/negatively about the sender than if no mixing had been used. | ||||||||||

| Mengvormvoorbeeld (bank) ‘Mixing example (bank)’ | |||||||||||

| Heb | je | sinds | kort | een | digitale | spiegelreflexcamera | |||||

| Have | you.T | since | short | a | digital | single-lens reflex camera | |||||

| of | wil | je | uw | camera | beter | leren | kennen? | ||||

| or | want | you.T | your.V | camera | better | learn.INF | know.INF? | ||||

| ‘Did you.T recently acquire a digital single lens reflex camera or do you.T want to get to know your.V camera better?’ | |||||||||||

| A | postiever ‘more positive’ | ||||||||||

| B | negatiever ‘more negative’ | ||||||||||

| C | geen van beide ‘neither’ | ||||||||||

| 8 | Door deze mengvorm denk ik postiever/negatiever over de afzender dan als er geen mengvorm was gebruikt. This case of mixing makes me think more positively/negatively about the sender than if no mixing had been used. | ||||||||||

| Mengvormvoorbeeld (dansles) Mixing example (dance class) | |||||||||||

| Vink aan | voor | welke | les | je | een | proefles | wil | aanvragen.(…) | |||

| Select | for | which | lesson | you.T | a | try-out.lesson | want | apply.INF.(…) | |||

| Voor | actuele | tarieven | en | lestijden | kunt | u | terecht | op | onze | website. | |

| For | current | prices | and | lesson.times | can | you.V | land | on | our | website. | |

| Voor | vragen | kunt | u | contact opnemen | via | (…) | |||||

| For | questions | can | you.V | contact | via | (…)l. | |||||

| ‘Choose which time you.T would like to request a try-out lesson. (…) You.V can find current pricing and times on our website. You.V can contact (…) | |||||||||||

| A | postiever ‘more positive’ | ||||||||||

| B | negatiever ‘more negative’ | ||||||||||

| C | geen van beide ‘neither’ | ||||||||||

| 9 | Door deze mengvorm denk ik postiever/negatiever over de afzender dan als er geen mengvorm was gebruikt. ‘This case of mixing makes me think more positively/negatively about the sender than if no mixing had been used.’ | ||||||||||

| Mengvormvoorbeeld (kliko) ‘Mixing example (wheelie bin) | |||||||||||

| Maak | uw | kliko | extra | herkenbaar | met | de | Kliko | stickers. | |||

| Make | your.V | wheelie bin | extra | recognizable | with | the | wheelie bin | stickers. | |||

| De | uitstekende | kwaliteit | van | de | sticker | zorgt ervoor | |||||

| The | outstanding | quality | of | the | sticker | ensures | |||||

| dat | de | stickers | goed | bevestigd | blijven | op | uw | container. | |||

| that | the | stickers | well | attached | stay | on | your.V | bin. | |||

| Uw | kliko | is | zodoende | altijd | te | herkennen | in | een | groep | containers, | |

| Your.V | wheelie bin | is | thus | always | to | recognize | in | a | group | bins, | |

| met | uw | eigen | persoonlijke | sticker. | |||||||

| with | your.V | own | personal | sticker. | |||||||

| Welke | sticker | kies | jij? | ||||||||

| Which | sticker | choose | you? | ||||||||

| ‘Make your.V wheelie bin extra recognizable with the wheelie bin stickers. The outstanding quality of the sticker ensures the stickers remain firmly attached to your bin. Your.V wheelie bin can therefore always be spotted in a group of bins, with your own personal sticker. Which sticker do you.T choose?’ | |||||||||||

| A | postiever ‘more positive’ | ||||||||||

| B | negatiever ‘more negative’ | ||||||||||

| C | geen van beide ‘neither’ | ||||||||||

| 10 | Door deze mengvorm denk ik postiever/negatiever over de afzender dan als er geen mengvorm was gebruikt. ‘This case of mixing makes me think more positively/negatively about the sender than if no mixing had been used.’ | ||||||||||

| Mengvormvoorbeeld (bestelbevestiging) ‘Mixing example (order confirmation)’ | |||||||||||

| Bedankt | voor | uw | aankoop. | ||||||||

| Thanks | for | your.V | purchase. | ||||||||

| Wij | sturen | u | een | nieuwe | wanneer | uw | bestelling | onderweg | is. | ||

| We | send | you.V | a | new | when | your.V | order | underway | is. | ||

| Binnenkort | ontvang | je | je | bestelling. | |||||||

| Soon | receive | you.T | your.T | order. | |||||||

| ‘Thank-you for your.V purchase. We will send you.V a new message when your.V order is on its way. You.T will receive your.T order soon.’ | |||||||||||

| A | postiever ‘more positive’ | ||||||||||

| B | negatiever ‘more negative’ | ||||||||||

| C | geen van beide ‘neither’ | ||||||||||

| 1 | The abbrevation AUB stands for alsublieft (if you_V please) and the dictionarry van Dale states that it functions as a ‘versterking bij een nadrukkelijk verzoek (‘a reinforcement of an emphatic request’). Our personal experience is that the letters of the abbreviation can be sounded out in spoken language as a reinforcement as well. |

| 2 | The student originally wrote in Dutch: ‘want door de taalfouten in de tekst blijkt dat er te snel is getypt en niet goed is terug gelezen. |

| 3 | The student originally wrote in Dutch De website is sowieso al onveilig en de teksten op de website bevatten ook al veel taalfouten. |

| 4 | The students originally wrote in Dutch: ‘omdat er letterlijk in dezelfde zin ‘u’ en ‘je’ wordt gebruikt’. |

| 5 | The students originally wrote in Dutch: ‘omdat meerdere keren is gebeurd en totaal niet logisch is om te doen’. |

| 6 | The students orginally wrote in Dutch: er word niet onderscheid gemaakt in een gebeurtenis of onderwerp’. |

| 7 | The students originally wrote in Dutch: ‘want als ze je gebruiken dan kan het persoonlijker overkomen, maar ze willen hem wel formeel afsluiten’. |

| 8 | The questionnaire contained screenshot images of each example. For privacy reasons, we are only including the text of each example here. The effect of formatting on pronoun use (for example, visual distance between pronouns may also impact how pronouns are perceived or used) falls outside the scope of this paper. The glosses are provided line by line, but the general translation is given for the text as a whole to better approximate the original presentation. |

References

- Aalberse, S. (2004). Le pronom de politesse u est-il en voie de disparition? Langage and Société, 108(2), 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalberse, S. (2009). Inflectional economy and politeness: Morphology-internal and morphological-external factors in the loss of second person marking in Dutch [Ph.D. thesis, University of Amsterdam]. [Google Scholar]

- Audring, J., & Booij, G. (2009). Genus als probleemcategorie. Taal en Tongval, 61(3), 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, H. (2007). Featuring the subject in Dutch imperatives. In Imperative clauses in generative grammar: Studies in honour of Frits Beukema (pp. 111–134). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R., & Gilman, A. (1960). The pronouns of power and solidarity. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), Style in language (pp. 253–276). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R., & Gilman, A. (1989). Politeness theory and Shakespeare’s four major tragedies. Language in Society, 18(2), 159–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoop, H., Levshina, N., & Segers, M. (2023). The effect of the use of T or V pronouns in Dutch HR communication. Journal of Pragmatics, 20, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoop, H., & Tarenskeen, S. (2015). It’s all about you in Dutch. Journal of Pragmatics, 88, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Hartog, M., van Hoften, M., & Schoenmakers, G. J. (2022). Pronouns of address in recruitment advertisements from multinational companies. Linguistics in the Netherlands, 39(1), 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, B. (2013). The spatiotemporal dimensions of person. In A morphosyntactic account of indexical pronouns. LOT. [Google Scholar]

- Haeseryn, W., Romijn, K., Geerts, G., de Rooij, J., & van den Toorn, M. (1997). 5.2.4 De persoonlijke voornaamwoorden van de tweede persoon (versie 2.1). Algemene Nederlandse Spraakkunst. Available online: https://e-ans.ivdnt.org/topics/pid/ans050204lingtopic (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Haverkate, H. (1984). Speech acts, speakers, and hearers: Reference and referential strategies in Spanish [Pragmatics & Beyond V:4] (pp. 83–84). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, F., & Janssen, D. (2005). U en je in Postbus 51 folders. Tijdschrift voor Taalbeheersing, 27(3), 214–229. [Google Scholar]

- Letterdesk. (2021, September). U of jij gebruiken op je website: Welke aanspreekvorm kies jij? Available online: https://letterdesk.nl/2021/09/u-of-jij-gebruiken-op-je-website-welke-aanspreekvorm-kies-jij/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Leung, E., Lenoir, A., Puntoni, S., & van Osselaer, S. (2023). Consumer preference for formal address and informal address from warm brands and competent brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 33(3), 546–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberhofer, K. (2011). Bristol speech linguistic and folk views on a socio-dialectal phenomenon. Unpublished manuscript. Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhof, A., Heynderickx, P., & Meex, B. (2017). Gecombineerd gebruik van u en je in personeelsadvertenties: Over de grammaticale en culturele context van aanspreekvormen. Tijdschrift voor Taalbeheersing, 39(3), 329–346. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, D. R. (1993). The uses of folk linguistics. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(2), 181–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, L., Zenner, E., Faviana, F., & van Landeghem, B. (2024). The (lack of) salience of T/V pronouns in professional communication: Evidence from an experimental study for Belgian Dutch. Languages, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, S., de Hoop, H., & Meijburg, L. (2024). You can help us! The impact of formal and informal second-person pronouns on monetary donations. Languages, 9(6), 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmakers, G., Hachimi, J., & de Hoop, H. (2024). Can you make a difference? The use of (in) formal address pronouns in advertisement slogans. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 36(2), 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Science Europe. (2018). Science Europe briefing paper on citizen science. D/2018/13.324/2. Available online: https://www.scienceeurope.org/media/gjze3dv4/se_briefingpaper_citizenscience.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Secretary Plus. (2024). Wanneer gebruik je ‘u’en ‘je’. Gebruik deze vuistregels. Available online: https://secretary-plus.nl/plus-insight/vuistregels-gebruik-u-of-je (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Simon, H. J. (2003a). From pragmatics to grammar. Tracing the development of respect in the history of the German pronouns of address. In I. Taavitsainen, & A. H. Jucker (Eds.), Diachronic perspectives on address term systems (pp. 85–123). Pragmatics and Beyond. New Series 107. Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H. J. (2003b). Für eine grammatische kategorie” Respekt” im deutschen: Synchronie, diachronie und typologie der deutschen anredepronomina (linguistische arbeiten). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Taavitsainen, I., & Jucker, A. H. (Eds.). (2003). Diachronic perspectives on address term systems (Vol. 107). John Benjamins Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Tarenskeen, S. (2010). From you to me (and back) [Master’s thesis, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen]. [Google Scholar]

- Vandekerckhove, R. (2005). Belgian Dutch versus Netherlandic Dutch: New patterns of divergence? On pronouns of address and diminutives. Multilingua, 24(4), 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandekerckhove, R. (2007). ‘Tussentaal’ as a source of change from below in Belgian Dutch. In S. Elspaß, N. Langer, J. Scharloth, & W. Vandenbussche (Eds.), Germanic language histories ‘from below’ (1700–2000) (pp. 189–203). Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eerd, C. (2016, May 16). U of jij: Wat is het beste in een tekst? Available online: https://tekstnet.nl/u-of-jij/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- van Zalk, F., & Jansen, F. (2004). Ze zeggen nog je tegen me. Leeftijdgebonden voorkeur voor aanspreekvormen in de persuasieve webtekst. Tijdschrift voor Taalbeheersing, 26(4), 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Vermaas, H. (2002). Veranderingen in de Nederlandse aanspreekvormen van de dertiende t/m de twintigste eeuw [Changes in Dutch forms of address from the thirteenth to the twentieth century] [Ph.D. thesis, LOT]. [Google Scholar]

- Vermaas, H. (2004). Mag ik u tutoyeren? Aanspreekvormen in Nederland. L.J. Veen/het taalfonds. [Google Scholar]

- Vismans, R. (2013). Address choice in Dutch 1: Variation and the role of domain. Dutch Crossing, 37(2), 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vismans, R. (2016). Jojoën tussen u en je: Over de dynamiek van het gebruik van Nederlandse aanspreekvormen in het radioprogramma Casa Luna. Internationale Neerlandistiek, 54(2), 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerman, F. (2007). It’s the economy, stupid! Een vergelijkende blik op ‘men’ en ‘man’. In M. Hüning, U. Vogel, T. van der Wouden, & A. Verhagen (Eds.), Nederlands tussen duits en engels (pp. 19–47). SNL. [Google Scholar]

| Form | Singular | Plural | Informal | Formal | Generic | Outer Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jij | + | − | + | − | +/− | − |

| je | + | −/+ | + | −/+ | + | − |

| u | + | +/− | − | + | −/+ | + |

| jullie | −/+ | + | + | −/+ | − | − |

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waar las/hoorde je het voor-beeld? | Wanneer las/hoorde je het voor-beeld? | Strategie of stom? Geef argumen-ten voor en tegen strate-gisch gebruik voor het voor-beeld | Foto/screenshot/situatiebeschrijving | Jij | Je | jou | u | jullie | |

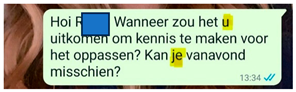

| 1 | WhatsApp Afzender: oppasser Ontvanger: oppasouder | 28 mei 2023 | Door het gebruik van ‘u’ kom je in eerste instantie formeel over en door het gebruik van ’je’ in hetzelfde bericht maak je een connectie tussen de oppasser en de ouders van het oppaskindje. (Dit was strategisch.) |  | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aalberse, S.P. Pronoun Mixing in Netherlandic Dutch Revisited: Perception of ‘u’ and ‘jij’ Use by Pre-University Students. Languages 2025, 10, 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090235

Aalberse SP. Pronoun Mixing in Netherlandic Dutch Revisited: Perception of ‘u’ and ‘jij’ Use by Pre-University Students. Languages. 2025; 10(9):235. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090235

Chicago/Turabian StyleAalberse, Suzanne Pauline. 2025. "Pronoun Mixing in Netherlandic Dutch Revisited: Perception of ‘u’ and ‘jij’ Use by Pre-University Students" Languages 10, no. 9: 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090235

APA StyleAalberse, S. P. (2025). Pronoun Mixing in Netherlandic Dutch Revisited: Perception of ‘u’ and ‘jij’ Use by Pre-University Students. Languages, 10(9), 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090235