Abstract

Childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) is characterized by atypical timing between segments, leading to prosodic disruption at the lexical level. This study tested whether prosodic impairment in CAS extends to the intonational level by examining declination of fundamental frequency (f0). Eleven children with CAS and ten typically developing (TD) peers aged 5 to 11 years old produced real and nonce multisyllabic words embedded in carrier phrases. Acoustic measures of inter-segment duration (within-word, between-word) and average f0 across segments were extracted. Children with CAS exhibited significantly longer inter-segment durations both within and between words, influenced by lexical stress position (first syllable, second syllable) and word status (real, nonce). They also showed shallower f0 declination slopes than TD peers, indicating reduced overall pitch fall. Segmentation and declination were not significantly correlated, suggesting distinct mechanisms underlying timing and pitch organization. Consistent with prior work, segmentation was greatest for nonce words with non-initial stress. Reduced declination in CAS may reflect limitations in prosodic planning or programming at the intonational level. These findings highlight dissociable disruptions in timing and pitch patterning in CAS, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of prosodic control in motor speech disorders.

1. Introduction

Childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) is a motor speech disorder that affects the planning and programming of speech (; ). The primary symptoms of CAS include inconsistent speech sound errors, speech segmentation, and errors in prosody (; ; ), all of which can impact the intelligibility and naturalness of speech. Among prosodic errors, lexical stress has been identified as a critical area of difficulty. Children with CAS exhibit equal and/or excess stress on syllables or incorrectly shifting stress onto nearby syllables (; ). However, prosody encompasses more than lexical stress alone—it operates across multiple levels of the prosodic hierarchy, from the syllable to the intonational phrase (; ). While lexical stress patterns have been extensively studied, little research has examined how children with CAS produce broader prosodic patterns, such as intonation, or how these interact with other timing-based features, such as segmentation. Understanding these interactions provides insight into how speech motor planning deficits manifest across prosodic levels and may ultimately aid in refining differential diagnosis and treatment of CAS. Thus, the central aim of this study is to explore how intonation, and more specifically declination, relates to segmentation in CAS, and how these features may differ between children with CAS and typically developing (TD) peers.

1.1. Childhood Apraxia of Speech and Motor Programming

Numerous studies have investigated the diagnostic features of CAS, showing that they share similarities with apraxia of speech (AOS) but with distinct developmental manifestations, particularly in lexical and phrasal stress (; ; ; ; ). Models of motor programming describe CAS as involving breakdowns in the processes that encode an abstract linguistic (phonological) message into a temporally organized sequence of motor commands (). These breakdowns result in increased inter-segment durations between speech sounds and syllables (i.e., segmentation), distortions of speech sounds, and dysprosody (; ). According to the Directions Into Velocities of Articulators (DIVA) model, such deficits reflect impaired feedforward and feedback control mechanisms that govern both segmental timing and suprasegmental modulation (e.g., pitch, lexical stress) (). Thus, prosodic and timing disruptions in CAS may share a common underlying planning deficit, linking lower-level temporal segmentation with higher-level intonational control.

Most studies use perceptual and/or acoustic characteristics for identifying and diagnosing CAS/AOS, including the examination of syllable segmentation and how feedback from word production affects motor output (). () showed that syllable segmentation contributed to the differentiation of children with CAS from those with other speech sound disorders when evaluated alongside other diagnostic features. Similarly, () found that fifteen of twenty school-aged participants with CAS exhibited syllable segmentation during the Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation (GFTA-2) (), whereas only three of ten participants with speech delay exhibited this feature. However, syllable segmentation alone is not fully diagnostic of CAS and may be susceptible to diagnostic circularity when classification includes syllable segmentation, as children are sometimes classified based partly on its presence. Relatedly, () reported that individuals with AOS have considerable difficulty with multisyllabic words due to the increased motor programming load. In terms of lexical stress, Shriberg and colleagues have identified equal/excess stress as a diagnostic marker of CAS, distinguishing it from speech delay using the Lexical Stress Ratio (LSR) metric (). Together, these findings suggest that both timing and prosodic features are clinically informative, though their diagnostic specificity remains debated. Unlike prior studies that emphasize identifying diagnostic markers, the present study instead examines how two prosodic features—segmentation and declination—relate to each other in CAS to understand their shared motor planning basis.

1.2. Treatments and Theoretical Grounding

Treatment programs for CAS target these underlying motor planning deficits to improve speech fluency and prosodic control. The Rapid Syllable Transition Treatment (ReST) program () uses multisyllabic pseudo-words to strengthen motor programming and lexical stress accuracy, while the Nuffield Dyspraxia Programme 3rd Edition (NDP3) () employs a structured hierarchy progressing from individual phonemes to multisyllabic real words to increase articulatory accuracy and consistency. In the first randomized controlled trial comparing these two treatments, () found that both approaches demonstrated improvements from pre- to post-treatment. Although ReST appeared to maintain gains more effectively at the one-month follow up, () reanalyzed the data, excluding the potentially biased 4-month post-treatment data, and cautioned that treatment effects could not be interpreted in terms of treatment efficacy due to the absence of a no-treatment control group. Therefore, while both ReST and NDP3 show promising clinical potential, causal claims regarding their effectiveness require cautious interpretation until additional controlled studies are available. These treatment outcomes are consistent with theoretical accounts that attribute speech disruptions in CAS to impaired motor planning and programming processes rather than phonological deficits alone (; ).

Building on these approaches, Treating Establishment of Motor Program Organization (TEMPOSM) combines pseudo-words and real words to target distortions, segmentation, and lexical stress (). Based on the principles of motor control, TEMPOSM stimuli consist of three- to four-syllable sequences with stop plosives or fricatives and strong-weak or weak-strong stress patterns (e.g., pseudo-words: TAgibu, taGIbu; real words: CUcumber, poTAto). These stimuli were used as baseline probes prior to treatment, offering controlled materials for assessing timing and stress coordination. () reported improvements in speech sound accuracy, reduced segmentation, and better lexical stress marking in children with CAS following TEMPOSM. Since the present study analyzes pre-treatment recordings from that dataset, these stimuli provide a consistent foundation to evaluate baseline differences in timing and intonation between children with CAS and TD peers.

Other studies have also investigated lexical stress in CAS, measuring the fundamental frequency (f0, or perceived pitch), duration, and intensity patterns across syllables (; , ; ; ). () further demonstrated that children with CAS exhibit reduced control of stress timing and pitch contrast during multisyllabic word production, underscoring prosodic planning difficulties. () introduced the Lexical Stress Ratio (LSR), an acoustic index used to quantify strong-weak stress contrasts and showed that children with CAS produce reduced stress contrast compared to TD peers. More recent work by () found that children with CAS showed reduced kinematic and acoustic contrasts between strong and weak syllables during an imitation task, even when segmental accuracy was adequate, suggesting that prosodic errors are not solely the by-product of speech sound distortions. Cross-linguistic work has also shown prosodic disturbances. Related work in Cantonese-speaking preschoolers with CAS shows difficulty with f0 variation during tone-sequencing tasks (, ). () found that this population produced reduced f0 contrasts in comparison to TD children and children with non-CAS speech sound disorder. These findings indicate that prosodic impairment in CAS may reflect limitations in higher-level speech planning rather than articulation alone. However, nearly all empirical research on prosody in CAS has focused on word-level stress, leaving a gap in understanding of how children with CAS produce phrase-level prosody, including intonation across utterances.

1.3. Segmentation

Segmentation refers to inappropriate lengthening and pausing between syllables or words, commonly seen in CAS and AOS. In adults, longer inter-segment intervals are reported for AOS but not for individuals with conduction aphasia or TD speakers (). Mechanistically, such segmentation is AOS has been linked to deficits in spatiotemporal and kinesthetic aspects of speech motor programming (, ; ). Although () examined adults with acquired impairment, similar hypotheses of disrupted motor planning have been proposed to account for segmentation behaviors in children with CAS (; ). Unlike adults with AOS, children with CAS are still developing phonological and prosodic representations, and therefore segmentation in CAS may reflect both motor programming deficits and immature linguistic planning.

() further proposed that segmentation reflects a working memory “loading delay” when linking syllables together. They described two underlying processes known as integration (INT) and sequencing (SEQ). INT preprograms shorter speech units in advance, while SEQ manages the serial ordering and execution of these preplanned units (; ). INT has higher processing demands for multisyllabic words, which helps explain the increased number of segmentation errors observed in longer and more complex utterances (; ). This account is conceptually consistent with (), who interpreted excessive pausing in AOS as reflecting difficulty transitioning between motor plans. In both accounts, transition difficulty is not a separate behavior from segmentation, but rather an explanation for why longer inter-segment durations occur.

Although theories differ in whether segmentation arises primarily from motor planning constraints (), limited working memory capacity (), or impaired feedforward control (; ; ), these accounts converge on the idea that segmentation reflects reduced fluency in speech planning. The present study does not attempt to distinguish among these mechanisms but uses segmentation as an established behavioral marker associated with impaired speech timing in CAS.

A growing body of research has focused on developing ways to detect and quantify segmentation. (, ) introduced the Pause Marker (PM) as an acoustic-aided perceptual feature to differentiate CAS from speech delay. The PM is defined as an inappropriate between-word pause of at least 150 milliseconds (ms) and has shown strong utility in characterizing one of the core timing-based features of CAS. Longer and more frequent pausing contributes to reduced fluency and naturalness, affecting intelligibility as well as overall prosody.

Importantly, segmentation has implications beyond timing alone. Continued investigation is needed to determine whether children with CAS plan speech one syllable at a time—as segmentation would suggest—or whether they plan larger units but experience breakdowns during execution (; ). This raises a key theoretical question: do prolonged inter-segment intervals interfere with prosodic organization at higher levels of the prosodic hierarchy (; )? Since segmentation disrupts temporal coordination within an utterance, it may also affect suprasegmental features such as intonation, potentially altering how pitch contours like declination unfold across speech. Examining how segmentation relates to intonation in CAS therefore provides a window into how temporal and prosodic planning interact in this disorder.

1.4. Intonation

Prosody is the melody and rhythm of speech expressed through suprasegmental features such as pitch, duration, and loudness. According to the prosodic hierarchy (; ), prosody is organized across levels ranging from the syllable to the utterance. From bottom to top, these levels include the syllable, foot, prosodic word, phonological phrase, intonational phrase, and utterance. The present study focuses on two of these levels, segmentation at the syllable level and intonation at the intonational phrase level, to determine how timing-based disruptions may influence higher-level pitch organization in CAS. Although segmentation could be described at the level of the foot when it occurs between syllables in a word, here it is operationalized at the syllable level to align with previous work in CAS that defines segmentation as prolonged pauses either within or between words (, ).

Lexical stress, the primary marker of word-level prominence in English, has been well studied in CAS and is widely documented as a diagnostic feature that distinguishes CAS from TD children (; ; ). For example, lexical stress contrasts strong-weak and weak-strong stress patterns that can discriminate between certain noun/verb pairs in English (REcordnoun vs. reCORDverb) (). At higher prosodic levels, accentuation marks informational focus, while intonation organizes pitch movements across phrases and utterances to convey pragmatic, syntactic, and discourse-level meaning (). Acoustically, these changes are reflected in f0, duration, intensity, and segmental quality (). Despite increased research attention to lexical stress in CAS, little is known about whether phrase-level prosody—particularly intonation—is also affected.

A key component of intonation is declination, defined as the overall downward trend of f0 across an utterance, also referred to as downtrend or downdrift (; ). Although declination can be described across different prosodic levels, it is most robustly observed at the intonational level, where it is aligned with natural pause structure (; ). Declination contributes to global prosodic organization by signaling the progression and completion of an intonational phrase (). Competing explanations have been offered regarding its origin: physiological accounts attribute declination to a gradual decrease in subglottal pressure and vocal fold tension over the course of an utterance (; ), while linguistic accounts argue that declination is under speaker’s control and serves communicative functions (). Some theories integrate both views and propose that global declination patterns interact with localized pitch movements (highs and lows) to convey semantic emphasis or discourse structure (; ; ).

Declination interacts with pitch reset (or f0 reset), a rise in f0 that occurs at the onset of a new intonational phrase following a pause (). In English, evidence from connected speech suggests that speakers adjust their initial f0 based on anticipated utterance length, producing steeper declination slopes in shorter utterances and shallower slopes in longer utterances (). These findings suggest that aspects of intonation, including declination and pitch reset, may be planned in advance rather than emerging solely from physiological decline (). In speech models, this global pitch planning is thought to reflect prosodic planning processes that operate before motor execution ().

Typical development research shows that children are sensitive to prosodic structure early in life and use prosodic cues in the input to segment speech and identify phrase boundaries (; ). However, little is known about how intonation develops in populations with motor speech disorders such as CAS. In acquired disorders, declination is often disrupted. For example, () found that Italian speakers with Broca’s aphasia exhibited disrupted declination due to excessive pausing, syllable lengthening, and abnormal f0 resetting. Similarly, () found reduced f0 range across utterances in French speakers with Broca’s aphasia. While these findings are informative and demonstrate that disruptions to timing and fluency can affect global pitch organization in connected speech, they reflect adult disorders and may not generalize to children, who are still developing both phonological and prosodic representations.

Limited research has been conducted for developmental disorders on declination and f0 reset and their relationship to utterance lengthening and segmentation. Only one known study used acoustic measurements to analyze f0 reset in 5- to 13-year-old speakers with language delay and (what was then referred to as) high-functioning autism (LD-HFA), Asperger’s syndrome (AS), and TD speakers (). Results showed a greater degree of f0 reset for the LD-HFA group than the TD peers, but no significant differences form the AS group. This was thought to be partially due to an increased pitch span in the LD-HFA group, signaling what was described as ‘exaggerated’ prosody. However, no published studies have examined f0 declination patterns in children with CAS, despite well-documented timing disruptions and stress errors in this population (; ). Given that segmentation disrupts temporal cohesion within an utterance, it may interfere with the implementation of global intonational patterns such as declination, which are typically associated with prosodic phrasing and utterance-finality marking ().

Previous work has identified differences in both timing control (segmentation) and prosodic structure (lexical stress errors) in CAS (; ). What remains unclear is whether these disruptions are restricted to syllable-level timing or whether they scale upward to affect higher-order prosodic planning. Theories of speech production differ in their assumptions about the scope of planning. Some models propose look-ahead planning over only a few words (), while others allow for more global organization across an entire utterance (). In this framework, prosodic planning refers to the organization of f0 movements and prominence patterns before speech execution, whereas motor programming involves generating the articulatory commands to implement that plan (; ). For children with CAS, who present with impairments in prearticulatory planning, the question arises as to whether they plan intonation globally (like TD speakers) or whether segmentation reflects a breakdown in motor programming that limits forward organization of pitch. Early models propose that segmental and prosodic processes may initially operate independently but interact during online speech planning (; ; ). Examining declination in CAS therefore provides a test of whether higher-level pitch structure is preserved despite timing disruptions and offers insight into how prosody is represented and controlled in this disorder. This motivation leads to the present study, which examines whether declination differs between children with CAS and TD peers and whether it is influenced by segmentation during connected speech.

1.5. Current Study

In summary, understanding the relationship between declination and segmentation offers insight into online motor programming and the extent to which prosodic planning is preserved in children with CAS. Rather than re-establishing known diagnostic characteristics of CAS, this study focuses on how two prosodic features—segmentation and declination—interact within the same utterances to clarify whether timing disruptions influence higher-level pitch organization.

Building on the dataset from (), the current study provides an acoustic comparison of intonation and segmentation features with CAS and TD children before the children with CAS received the TEMPOSM treatment. While segmentation and prosodic abnormalities are part of the perceptual profile of CAS, the goal of this study is not to confirm their presence but to quantify the relationship between these features. By examining how segmentation (syllable-level timing) relates to declination (intonational-level f0 organization), this study tests whether timing disruptions in CAS scale upward to affect global prosodic structure. Although this study includes CAS and TD groups, future work should include children with other speech disorders to determine whether observed patterns are specific to CAS.

Recent work suggests that prosodic difficulties in CAS extend beyond lexical stress. () observed reduced strong-weak contrast in children with CAS even when segmental accuracy was preserved, indicating disruption in prosodic planning. Similarly, () reported reduced f0 modulation in Cantonese-speaking children with CAS, suggesting limited pitch control across languages. Together, these findings motivate investigation into whether children with CAS show disruptions not only at the word level but also in phrase-level prosody, including declination.

The aims of this study are three-fold: (1) analyze segmentation, measured by inter-segment durations between and within words, in children with CAS compared to TD children; (2) compare the degree to which the two groups exhibit declination across declarative utterances; and (3) examine whether segmentation and declination are related in either group.

First, it is hypothesized that segmentation will be a strong differentiating variable between these two populations. Previous work has found increased inter-segment duration between syllables of multisyllabic words produced by children with CAS (; ). Based on this literature, we predict that children with CAS will present with significantly longer inter-segment durations between and within words compared to TD children. Additionally, due to the structure of the words utilized from TEMPOSM, we hypothesize differences in the degree of segmentation based on lexical status (nonce vs. real) and primary stress location (first vs. second syllable). Real words are expected to produce shorter pauses since they are practiced more often and have faster lexical retrieval, resulting in less disruption (; ). Words with second-syllable lexical stress are also expected to show greater segmentation due to increased planning demands partially due to the coordination of prior unstressed syllables (; ; ).

Second, we predict that children with CAS will demonstrate reduced declination compared to TD children, reflected by flatter f0 slopes. If children with CAS engage in reduced prosodic preplanning of utterance-level pitch contours, consistent with speech motor control accounts of reduced feedforward control (), they may be less able to produce global f0 decline. Previous studies have documented f0 modulation differences in CAS (), but declination has not yet been explored.

Third, we hypothesize that there will be a relationship between declination and segmentation. Specifically, longer inter-segment durations are expected to disrupt the continuity of f0 decline, potentially increasing opportunities for f0 reset and reducing the magnitude of declination across the utterance. Alternatively, if declination remains stable even in the presence of segmentation, this may suggest that prosodic planning is preserved despite timing disruptions. Testing the relationship between segmentation and declination allows us to examine whether temporal and prosodic control operate independently or interactively in CAS. Understanding whether timing and prosody interact in CAS may also inform future intervention approaches targeting both segmentation and prosodic control.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were ten TD children aged 5;10–11;0 (M = 8;11, SD = 1;7) and 11 children with a diagnosis of CAS aged 5;10–8;00 (M = 7;06, SD = 0;9). The TD group included 4 females and 6 males; the CAS group included 2 females and 9 males, consistent with the higher prevalence rate of CAS in males (). All participants were native speakers of United States English and passed a hearing screening at 25 dB for frequencies of 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz, and 4000 Hz in both ears. All participants—except those in the CAS group—had no developmental, neurological, genetic, or speech disorders, as confirmed via parent questionnaire.

Data for the CAS group were drawn from the TEMPOSM treatment study (). In that study, diagnoses were established by two licensed speech-language pathologists using a multi-task protocol with the Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale (). This protocol included oral-mechanism and motor speech examinations (i.e., diadochokinesis, production of multisyllabic words, and connected speech samples) (). For the present study, a senior author verified eligibility against the same criteria; no re-classification was performed. Diagnostic characterization follows the American Speech Language Hearing Association’s (ASHA) core features (). Segmentation was documented but not used as an inclusion requirement. Acoustic segmentation measurements were obtained by raters blinded to group.

Similarly, TD participants were evaluated to ensure they did not exhibit symptoms of CAS using the same oral and motor speech examinations. For the Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation (GFTA-2; ), the CAS group had an overall lower standard score than the TD group with a statistically significant difference, M = 48.18, 95% CI [36.36, 60.01], t(10.85) = 8.982, p < 0.001. Four children with CAS scored below the average range (85–110) for the Core Language Score of the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-Fifth Edition (CELF-5; ), and the CAS group had an overall lower average score than the TD group, with a statistically significant difference, M = 29.34, 95% CI [19.51, 39.16], t(19) = 6.250, p < 0.001. Table 1 provides details on each individual participant as well as group means and standard deviations.

Table 1.

Participant age, sex, oral and motor speech exam results, standard score for the GFTA-2, and CELF-5 Core Language score. Bold indicates overall means (standard deviations) by group.

2.2. Procedure

This study had Institutional Review Board approval at [suppressed for peer review]. Following legal guardian/parental consent and child assent, hearing screenings were conducted in a soundproof booth. The remainder of the screening was conducted in a quiet room and recorded using a Samson XPD2 Headset USB Digital Wireless System, with the microphone placed 5 cm from the child’s mouth. The screening consisted of asking a general set of conversation questions, completing a picture description task, and administering the core language portion of the CELF-5 (). Following a five-minute break, the remainder of the screening consisted of administering an oral mechanism exam, a motor speech exam, and the GFTA-2 (, see Table 1 for participant scores).

After the screening, the experimental portion of the study began. Participants were asked to produce a baseline word list by repeating back a list of 120 different stimuli that were randomly matched to one of 10 different carrier phrases. The stimuli list was originally developed for TEMPOSM (). Words were a combination of real and nonce words made up of three or four syllables with primary lexical stress on the initial or second syllable. The nonce words contained consonants of either all stop plosives or fricatives (real word examples: CUcumber, poTAto, spaGHEtti; nonce word examples: BIgatu, giBUta, fuSIsha). Carrier phrases varied in length from two to four words. (e.g., Here’s the <target>, It’s a red <target>, I went to the <target>). Stimuli order was semi-randomized with four different list orders used. See Supplementary Material for a list of all stimuli and carrier phrases. Both groups completed screening and the baseline word-list recording within a two-hour session with frequent short breaks; when attention waned, additional breaks were provided to maintain data quality.

2.3. Acoustic Measures

Acoustic measures were selected to capture prosodic control across hierarchical levels (syllable, word, utterance), following recommendations for acoustic quantification of lexical stress in CAS (). Acoustic measurements of inter-segment duration and f0 were taken on all real and nonce productions from the baseline lists from TEMPOSM (). Here, inter-segment denotes inter-syllabic (within-word) and inter-word junctures (between-word); it does not refer to phonemic/segmental boundaries. Transcriptions and acoustic analyses of all stimuli were completed using Praat ().

Inter-segment duration was calculated in milliseconds (ms) by marking the start and end of words and syllable intervals. For unvoiced junctures, the interval boundary spanned from the last glottal pulse (as indicated by cessation of voicing of energy through F1 and F2) to the onset of the following segment (plosive burst or frication). For voiced consonants where glottal pulses may continue across a juncture, boundaries were placed at the primary acoustic landmark for the following onset (e.g., plosive burst onset, frication onset, or sustained increase in aperiodic energy) rather than at pulse cessation. Spectro-temporal cues (release burst, onset of frication, abrupt F1/F2 energy change) guided placement.

Between-word durations were calculated for each juncture between words 1–2 (W1), 2–3 (W2), 3–4 (W3), and 4–5 (W4). Within-word inter-segment durations were calculated between syllables 1–2 (S1), 2–3 (S2), and 3–4 (S3). Two of the eleven CAS participants (CAS03, CAS04) produced only target words of three syllables, while the remaining nine participants produced target words of three and four syllables. Only three-syllable words were analyzed as they comprised the vast majority of the dataset. See Figure 1 for the Praat coding schematic.

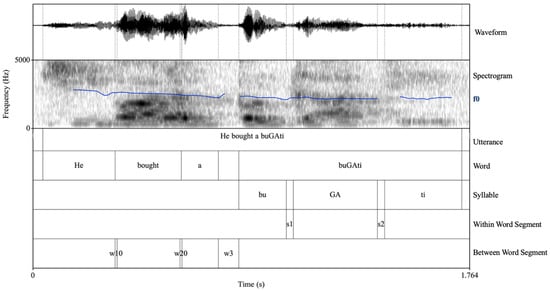

Figure 1.

Example utterance of a waveform, spectrogram, and textgrid with five tiers. Interval boundaries mark the start and end of each segment (utterance, word, syllable, or inter-segment). The blue line indicates the f0 track between the range of 50 and 400 Hz for this speaker. Note that a 0 is added to a segment label (e.g., w10 vs. w1) to indicate no pause (0 ms).

Average and maximum f0 in Mels were computed within the labeled word/syllable intervals, excluding silent/aperiodic pause intervals. Praat settings used the autocorrelation method with a default time step of 0.01 s. F0 floor/ceiling were adapted per child (typical: 50–500 Hz baseline) to optimize tracking.

2.4. Reliability

For the acoustic measures, a second rater coded a randomly selected 25% of the first rater’s samples to calculate inter-rater reliability of the boundary placements. To do this, we calculated intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and absolute average point-to-point differences (APD) for between-word pause interval boundaries (a metric of boundary placement) to assess the level of agreement between raters. An ICC(2,1) was calculated to determine the consistency of ratings among two raters for 604 items. The ICC was 0.96, 95% CI [0.95, 0.97], indicating high inter-rater reliability across raters (p < 0.001). Average APD for between-word pauses was 11.37 ms (SD = 25.39 ms). Pitch measures were taken from within these boundaries.

2.5. Analyses

There were 2520 utterances recorded across all participants (120 utterances × 21 participants). Initial exclusions were made due to poor recording quality (e.g., child whispering, quiet talking, incomplete audio files, or background noise; n = 34), child influences (e.g., responding with an interrogative, yawning, coughing, laughing, yelling, or silly voice; n = 54), research clinician influenced (e.g., incorrect or segmented model production; n = 15), and including an interrogative carrier phrase (n = 183). Other exclusions and final totals used for analyses are presented in the following sections. All analyses were conducted in R (v. 4.2.3, ) using packages car, dplyr, forcats, ggplot2, ggpubr, lme4, pbkrtest, and tidyverse (; ; ; ; , ; , ). Figures were made with the color blind palette package viridis ().

2.5.1. Segmentation Analyses

Two measures were extracted to analyze segmentation: (1) between-syllable pauses (pauses between syllables in the target words), and (2) between-word pauses (pauses between each word in the full utterance). After initial exclusions, there were 3566 between-syllable pauses in the target words in the data set. Next, we filtered down to only three-syllable target words to ensure consistency across the analysis leaving 2295 data points. Additionally, after filtering out any missing data or errors, excluding data beyond the second between-syllable pause (applying to cases where additional syllables may have been added to the word), and averaging over the pause durations within an utterance, 1034 data points remained for the final between-syllable pause analysis. Thus, in these analyses, if a child produced more than three syllables in a target word, we only averaged the first two between-syllable pauses. Moreover, if a child only had one pause in the target word, we excluded that data point from analyses. An alternative analysis (see Supplementary Material) was conducted that leaves in data where we only have one pause available to analyze in a target word and does not exclude pauses after the first two in the averaging. For the between-word dataset, after the initial exclusions, there were 4775 between-word pauses. We then filtered down to utterances with only three-syllable target words, leaving 3509 data points. After filtering out any missing data or errors, 3369 data points remained for the final between-word pause analysis. Note that the between-word pauses were not averaged like they were in the between-syllable analyses because this would have required us to average over different numbers of pauses for utterances of different lengths. Because the variance of a sample average depends on the number of data points averaged, this could have produced the undesirable result that the data have systematically differing variance, violating the modeling assumption of homogeneity of variance. Rather, each data point is an individual pause.

Since a large proportion of the between-syllable and between-word segmentation data are zero (i.e., no pause between words), these data cannot be analyzed as continuous. Rather, they are more appropriately analyzed as semi-continuous with separate analyses for (1) the continuous between-word (or average between-syllable) data, conditional on those data being greater than length zero and (2) whether or not the between-word (or average between-syllable) data have length zero. To analyze the impact of child group, stress location in target word, and target word status, we fit two types of models for each analysis. The first is a linear mixed effects model of (1) the average pause length between syllables in the target word and (2) between words in the utterance, conditional on that value being greater than zero. Fixed predictors include group (TD, CAS), stress location in target word (first syllable, second syllable), target word status (real, nonce), the interaction of group and stress location, and the interaction of group and target word status. Each model additionally includes a random intercept per child, target word, and carrier phrase to account for the possible correlation among data. A Box–Cox transformation was applied to the outcome for each model to help the data better conform to modeling assumptions (). Model assumptions were checked after data transformations, and the Box–Cox approach consistently resulted in the data meeting those assumptions. Estimates and confidence intervals are reported on the analytical (i.e., transformed) scale. Degrees of freedom and standard errors are estimated using the method of (). Linear hypothesis tests are utilized to explore the key questions of interest.

The second model is a logistic regression model estimated using generalized estimating equations (GEE) of whether or not the average pause length between segments (i.e., between syllables in target word or between words in the utterance) is greater than zero (i.e., average pause length > 0 is coded as 1; average pause length = 0 is coded as 0). For the between-word segmentation analyses, we fit models using the same predictor structure as in the continuous models. However, in the between-syllable segmentation models, we get complete separability of the outcome zeros and ones when the interaction of child group and target word status is included. This is because children with CAS always produced average between-syllable durations greater than zero milliseconds for nonce target words. Thus, being in that category produced perfect prediction of the dichotomous outcome. Because of the challenge of fitting the model in cases like this and the instability of model estimates for predictors causing such complete separability (), we decided to fit a simpler predictor structure to the dichotomized outcome in order to eliminate this issue. We only include main effects predictors for group, stress location, and target word status. While in the linear mixed effects models we could simultaneously account for the correlation among data from the same child and the same target word, the implementation of GEEs in R only allows us to account for one source of possible correlation via a set type of working correlation structure.

Thus, for both models, we examined the estimated correlation among data from the same child and separately from the same utterance; the grouping variable (i.e., child or utterance) that produced the higher correlation was selected. For the between-syllable model, target word was chosen as the grouping variable; for the between-word model, child was selected. An exchangeable working correlation structure was used in both models; this structure allowed the data from each child or associated with each target word (depending on which grouping variable was chosen) to all be equally correlated. In the between-syllable model, the sandwich estimate of the estimated parameter variance-covariance was used (); in the between-word model, the fully iterated jackknife estimate was used. The sandwich estimator has the advantage of being robust to misspecifications of the selected working correlation matrix. However, when there are less than or equal to 30 groups in the selected grouping structure (i.e., ≤30 children or ≤30 target words), the sandwich estimator is biased, and the fully iterated jackknife estimator is thus preferred (; ). Results from these models are presented as odds ratios, and the associated tests of whether or not the odds ratios are equal to one are chi-squared tests.

2.5.2. Declination Analyses

The goal of the declination analysis was to test group, stress location, and target word status differences in the across-utterance f0 slope. After initial exclusions, there were 5215 data points, representing individual pitch points of all words across utterances. Word-level average and maximum f0 were computed from the continuous f0 track within the labeled word interval. Next, we filtered down to only utterances containing three-syllable target words to ensure consistency across the analysis, leaving 3666 data points. We also filtered out any missing data or f0 tracking errors, which left 3632 data points for the declination analysis. We conducted separate analyses on (1) the average f0 (in Mels) of words across utterances (declination analysis), (2) the average f0 (in Mels) of the target words in each utterance (average target word pitch analysis) and (3) the maximum f0 (in Mels) of the target words in each utterance (maximum target word pitch analysis). For the analyses of target words only, there were 949 data points.

The declination analysis fit a linear mixed effects model to the average f0 in Mels of the words in each utterance. Fixed predictors included word number in utterance, group (TD, CAS), stress location in target word (first syllable, second syllable), and target word status (real, nonce). The three-way interactions of (1) group, stress location, and word number and (2) group, target word, and word number were included, as well as all two-way interactions involving variables in each three-way interaction. Random intercepts per child, target word, and carrier phrase were included to account for the possible correlation among data from the same child, from utterances with the same target word, and from utterances of the same carrier phrase. In these models, f0 slope is defined as the change in f0 from one word to the next in an utterance and is captured by the coefficient for word number (and modifications to that coefficient given by interactions). In other words, when the speaker moves from word n to word n + 1, the f0 slope captures how much their f0 changed. Linear hypothesis tests are utilized to compare f0 slope across various conditions.

We examined utterance-final f0 values by modeling the average and maximum f0 values of the target words since target words occurred at the end of each utterance. To do this, a linear mixed effects model was fitted to the maximum f0 in Mels of the target word in each utterance. Fixed predictors include group (TD, CAS), stress location in target word (first syllable, second syllable), target word status (real, nonce), the interaction of group and stress location, and the interaction of group and target word status. Random intercepts were included per child, target word, and carrier phrase. However, because the variance of the random intercepts per carrier phrase was estimated to be zero, a reduced version of the model that removes the random intercept per carrier phrase is reported. A Box–Cox transformation was applied to the target word maximum pitch data because they displayed deviations from model assumptions (). The transformation resulted in better adherence of the data to modeling assumptions.

2.5.3. Declination and Segmentation Interaction Analysis

The between-word pause data and the f0 data across utterances data (in Mels) were used to analyze whether or not pitch slope (i.e., declination) depends on the average between-word duration in the utterance and whether that relationship depends on child group (CAS, TD). After joining the pitch and between-words datasets such that corresponding data points across the two datasets have the same ID, target word, carrier phrase, target word status, and target word stress location, there were 3544 usable data points (i.e., those that have a counterpart in both datasets). Like in the declination analyses, these analyses fit a linear mixed effects model to the average pitch in Mels of each word in the utterances. Fixed predictors include word number (e.g., first word, second word) in the utterance, group (CAS, TD), the average between-word duration in the utterance, the three-way interaction of word number, group, and average between-word duration, and all associated two-way interactions. Following previously described models, this model additionally includes a random intercept per child, target word, and carrier phrase to account for the possible correlation among data from the same child, from utterances with the same target word, and from utterances of the same carrier phrase.

3. Results

3.1. Segmentation Results

3.1.1. Analyses of Between-Unit Pause Duration Conditional on Between-Unit Pause > 0

Between-Syllable Results

Fixed parameter estimates for the full model are shown in Table 2 but note that key results are derived from linear hypothesis tests, which address the questions and contrasts of interest in this study. Note on reference levels: in all models, TD is the reference group for Group, first syllable stress for Stress Location, and real words for Target Word Status.

Table 2.

Fixed effect parameter estimates for the transformed model of the average duration between syllables in a target word, conditional on that value being greater than zero.

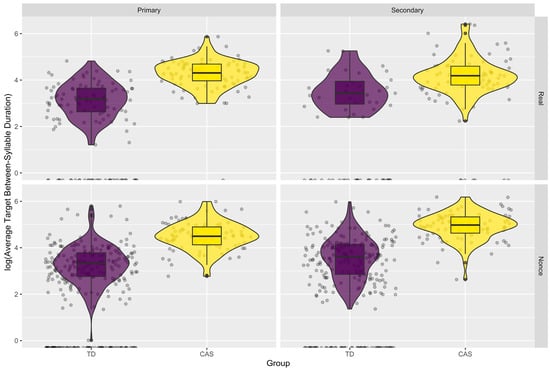

The model of between-syllable pause durations revealed a statistically significant group difference with children with CAS showing significantly longer durations (β = 1.68, 95% CI [1.28, 2.08], t(20.56) = 8.72, p < 0.001; MCAS = 88.31 ms, MTD = 28.81 ms). On average, pauses between syllables in nonce words were longer than in real words (β = 0.42, 95% CI [0.18, 0.66], t(94.54) = 3.51, p < 0.001; Mnonce = 67.95 ms, Mreal = 49.17 ms), with this difference significant for children with CAS (β = 0.57, 95% CI [0.27, 0.87], t(224.64) = 3.75, p < 0.001; MCAS-nonce = 104.84 ms, MCAS-real = 72.78 ms) but not for TD children (β = 0.27, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.56], t(154.76) = 1.85, p = 0.066; MTD-nonce = 31.06 ms, MTD-real = 25.57 ms). Finally, the comparison between target words with primary stress on the first versus the second syllable showed longer durations between syllables in words with primary stress on the second syllable (β = −0.40, 95% CI [−0.58, −0.23], t(381.43) = −4.46, p < 0.001; Mfirst = 51.20 ms, Msecond = 65.42 ms). This difference was significant for both CAS (β = −0.37, 95% CI [−0.61, −0.12], t(614.85) = −2.92, p = 0.004; MCAS-first = 78.48ms, MCAS-second = 99.13 ms) and TD groups (β = −0.44, 95% CI [−0.66, −0.21], t(409.31) = −3.82, p < 0.001; MTD-first = 23.91 ms, MTD-second = 32.71 ms). Table 2 provides exact estimates and model results while Figure 2 visualizes distributions and modeled effects for the two groups, and all other tested contrasts were not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Log of the average target word between-syllable pause duration split by child group (TD = purple, CAS = yellow) along the x-axis, target word stress location (first, second) in the vertical panels, and target word status (real, nonce) in the horizonal panels. Box plots show medians and inter-quartile ranges. A Box–Cox transformation was applied (λ = 0.1).

Between-Word Results

Parameter estimates for the full model are presented in Table 3 but note that like with the between-syllable results, key results are derived from the linear hypothesis tests to more accurately address our study questions. Figure 3 provides visualizes distributions and modeled effects for the two groups.

Table 3.

Fixed effect parameter estimates for the transformed model of the duration between words in an utterance, conditional on that value being greater than zero. A Box–Cox transformation was applied to the outcome with parameter lambda = −0.1.

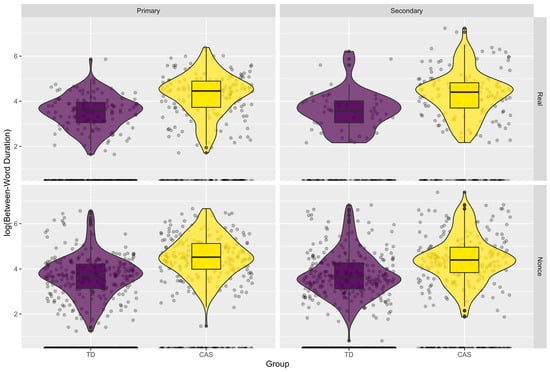

Figure 3.

Log of the utterance between-word pause duration split by child group (TD = purple, CAS = yellow) on the x-axis, target word stress location (first, second) in the vertical panels, and target word status (real, nonce) in the horizontal panels. Box plots show medians with inter-quartile ranges.

The between-word pause linear mixed model showed a significant effect of group with longer between-word pauses for the CAS group (β = 0.50, 95% CI [0.30, 0.71], t(19.61) = 5.05, p < 0.001; MCAS = 78.88 ms, MTD = 37.45 ms). Mirroring the between-syllable pause testing, pauses between words in utterances with a final nonce word were longer than in utterances with real words (β = 0.12, 95% CI [0.04, 0.19], t(101.39) = 3.02, p = 0.003; Mnonce = 62.93 ms, Mreal = 52.90 ms), with this difference significant for children with CAS (β = 0.13, 95% CI [0.03, 0.23], t(273.33) = 2.57, p = 0.011; MCAS-nonce = 86.33 ms, MCAS-real = 70.39 ms) but not for TD children (β = 0.10, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.21], t(264.20) = 1.77, p = 0.078; MTD-nonce = 39.53 ms, MTD-real = 34.37 ms). No other contrasts reached statistical significance.

3.1.2. Analyses of Presence vs. Absence of Between-Unit Pause

Between-Syllable Results

For the between-syllable model (Table 4), only group was significant, indicating that children with CAS were 10.49 times more likely to have a pause between syllables than TD children. The features of the target word in the utterance did not significantly impact whether there was pausing (i.e., if the target was nonce or real or if it had primary stress on the first or second syllable).

Table 4.

Parameter estimates for the logistic regression model using GEEs of the average duration between syllables in target word, dichotomized such that an outcome of 1 corresponds to the average duration between syllables in target word being greater than 0 and an outcome of 0 corresponds to the average duration between syllables in target word being equal to 0. Each target word defined a cluster of data.

Between-Word Results

For the between-word model (Table 5), group also significantly impacted the odds of having a pause between words, with the children with CAS 3.53 times more likely to produce between-word pauses than TD children.

Table 5.

Parameter estimates for the logistic regression model using GEEs of the duration between words in in an utterance, dichotomized such that an outcome of 1 corresponds to the average duration between syllables in target word being greater than 0 and an outcome of 0 corresponds to the average duration between syllables in target word being equal to 0. Each child defined a cluster of data.

The interaction between group and target word status was also significant (Odds Ratio = 1.44, 95% CI on Odds Ratio [1.14, 1.82], χ2 = 9.44, p = 0.002). Follow up linear hypothesis tests show that this is driven by the children with CAS who were 1.37 times more likely to produce pauses between words in utterances where the target word was nonce versus a real word (Odds Ratio = 1.37, 95% CI on Odds Ratio [1.10, 1.70], χ2 = 8.19, p = 0.004) compared to a non-significant difference for TD children (p > 0.05). All other interactions were not significant. A full list of all linear hypothesis test comparisons for all segmentation models is reported in the Supplementary Material.

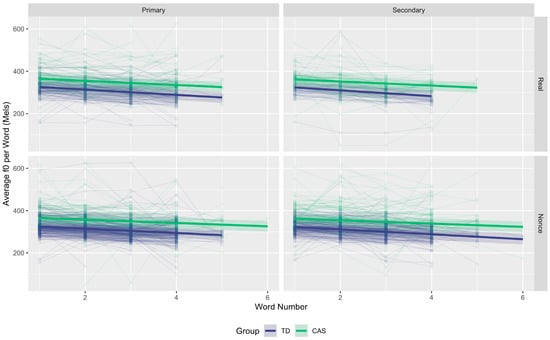

3.2. Declination Results

Fixed effect parameter estimates for all main effects and interactions are reported in Table 6; word number indexes each word in an utterance and operationalizes f0 slope (change from word n to word n + 1). Average f0 across the utterance (reflecting the degree of declination) was significantly predicted by word number, a proxy of pitch slope change over time, and by group. Linear hypothesis tests show that children with CAS had significantly less steep negative slopes over utterances than TD children (β = 3.05, 95% CI [0.31, 5.78], t(3586.71) = 2.19, p = 0.029; MCAS = −8.86 Mels, MTD = −11.91 Mels) (Figure 4). No other main effects or interactions reached significance.

Table 6.

Fixed effect parameter estimates for the un-transformed model of Average f0 Over Word (Mels).

Figure 4.

Average f0 (Mels) by word in utterance, split by target word stress location (vertical panels) and target word status (horizontal panels). Child group: TD (purple), CAS (green). Lines connect points to illustrate within-utterance trajectories; shading indicates 95% CIs.

A linear fixed effects model was also fitted to the maximum f0 in Mels of the final word in the utterance to examine the relative differences in pitch at the end of the utterance between group and across different types of target words (i.e., nonce vs. real; first vs. second syllable primary stress). There was a significant main effect of group as well as a significant interaction between group and target word status (Table 7). Linear hypothesis tests show that children with CAS had significantly higher maximum f0 at the end of their utterances (β = 1.38, 95% CI [0.72, 2.04], t(19.26) = 4.37, p < 0.001; MCAS = 402.20 Mels, MTD = 317.12 Mels). Since this endpoint reflects absolute f0 at the end of the utterance, group differences may partly reflect individual anatomical or habitual pitch differences. We therefore interpret this effect cautiously and emphasize the slope analyses for inferences about declination. See Supplementary Material for all linear hypothesis comparisons across declination analyses.

Table 7.

Fixed effect parameter estimates for the transformed model of Max Target Word Pitch (Mels). A Box–Cox transformation was applied to the outcome with parameter lambda = 0.3.

3.3. Declination and Segmentation Relationship Results

There was no impact of between-word average duration on the f0 slope across the utterance on average (β = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.03], t(3473.28) = 0.45, p = 0.655). Additionally, there was not a statistically significant difference between the effects of between-word average duration on f0 slope between TD and CAS children (β = 0.00, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.06], t(3473.07) = 0.14, p = 0.888). Taken together, average between-word duration did not predict declination f0, and this effect did not differ by group. Analyses focused on between-word pauses by design; between-syllable pauses were not modeled in this portion. Full model parameter estimates and linear hypothesis tests are available in the Supplementary Material.

4. Discussion

This study examined prosodic production in children with CAS relative to TD peers, focusing on segmentation, declination, and their potential interaction. We found (i) robust group differences in segmentation that were modulated by stress pattern and lexical status, (ii) reduced declination in CAS at the utterance level, and (iii) no evidence that longer between-word pauses reduced declination slopes.

4.1. Segmentation Discussion

Consistent with prior work, children with CAS produced longer inter-segment pauses than TD children and were more likely to insert pauses between syllables and between words. Lexical status modulated these effects, with nonce targets eliciting longer (and more frequent) pauses than real words, an effect driven by the CAS group. This pattern aligns with accounts in which familiar lexical items benefit from more established feedforward programs and faster retrieval than novel forms (; ; ). Stress patterns also mattered, demonstrating that words with second syllable (iambic) stress yielded longer between-syllable pauses than words with initial (trochaic) stress in both groups, consistent with the trochaic bias in English and its motor-programming economy (; ; ). Although absolute between-syllable durations were greater in CAS overall, the stress-by group difference did not reach significance.

In terms of whether children paused between syllables or words, children with CAS were far more likely to insert pauses between segments. Specifically, they were over ten times more likely to pause between syllables and three times more likely to pause between words than TD children (see Section 3.1.2 in the Segmentation Results). This increased frequency of pauses is related, though not equivalent, to the duration of pauses, and is reflected in the findings that children are more likely to pause as well as have longer pauses before nonce words (vs. real words). Although frequency and duration index different aspects of temporal control, both patterns point to greater disruption in speech timing and increased segmentation demands, especially for nonce targets. Overall, the segmentation results replicate prior showing that increased inter-segment pauses occur significantly more for nonce words, iambic stress patterns, and children with CAS. This study extends those findings by examining these patterns in a controlled set of baseline sentences and target words from the TEMPOSM protocol and by directly comparing performance with a TD control group ().

Although within-word pauses were numerically longer than between-word pauses for children with CAS, we did not test this difference statistically because the two measures differ analytically—within-word pauses were averaged per target word and between-word pauses modeled per juncture—and such a comparison was beyond our original hypotheses. Future analyses could examine this contrast directly to clarify whether segmentation patterns differ across levels of the prosodic hierarchy.

4.2. Declination Discussion

We operationalized declination as the change in average f0 (Mels) across successive words in an utterance (word-indexed slope). Our work extends measurement of prosodic control beyond word-level stress () to utterance-level f0 decline (declination), thereby addressing higher levels of the prosodic hierarchy. Here, children with CAS showed shallower negative slopes and higher utterance-final f0, indicating reduced global f0 downtrend and a compressed overall pitch range relative to TD children. We interpret this cautiously since while many accounts posit physiological contributors to downtrend (e.g., subglottal pressure, laryngeal muscle dynamics), our data do not measure these mechanisms directly. Thus, we treat such factors as plausible influences rather than established causes in the present context. At the same time, cross-linguistic and discourse finding suggest prosodic/linguistic control also shapes the presence and rate of declination (e.g., final lowering, focus) (, ). Our slope result converges with reports of reduced f0 modulation in other pediatric samples (e.g., Cantonese tone-sequencing tasks; , ), extending those findings from local tonal contrasts to phrase-level pitch organization in connected speech.

The question arises of why declination might be reduced in CAS. Within a motor framework, two non-exclusive explanations may account for our findings. One possibility is an implementation constraint, in which impairments in prearticulatory motor planning and programming limit the stability or span of the intended pitch trajectory. This constraint could yield an overall flatter contour even when higher-level prosodic targets are appropriately specified (; ; ). A second explanation involves multi-level interaction, whereby increased timing variability and weaker strong-weak contrasts at the syllable or foot level diminish successive local f0 peaks. This reduction in local prominence could produce a shallower global decline in pitch despite intact prosodic plan (; ; ). Thus, the reduced declination in CAS is consistent with a generally compressed pitch contour across the utterance.

These group patterns also align with evidence that children with CAS exhibit greater spatiotemporal variability in speech motor control than their TD peers (). Such variability may reduce the consistency and amplitude of f0 trajectories across utterances, contributing to flatter declination slopes and increased segmentation. Thus, group differences in prosody may reflect both reduced average stability and heightened variability in motor implementation.

4.3. Segmentation–Declination Relationship Discussion

We predicted that longer pauses might introduce opportunities for f0 reset, thereby attenuating declination (; ). Using mean between-word duration per utterance as the timing covariate, we found no effect on slope and no group difference in that effect. Two interpretation remain viable: (a) declination is already sufficiently compressed in CAS such that any additional reset-related impact is small relative to slope variance; or (b) segmentation and declination are partly dissociable, governed by two overlapping but separable control processes, for example, temporal gating of articulatory sequences versus global pitch organization (; ; ). Importantly, we did not quantify explicit pitch resets at phrase boundaries. Future analyses using time-indexed models of elapsed time or word-to-word onset intervals and explicit f0 reset detection (e.g., ; ) could test this mechanism more directly within a motor-prosodic integration framework (; ).

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

This study used controlled stimuli from the TEMPOSM baseline lists and included a modest sample size typical for research in CAS, which remains a low-prevalence disorder (; ; ). The use of controlled materials allowed systematic manipulation of lexical status and stress pattern, enhancing internal validity but potentially limiting ecological generalizability. Since these materials were elicited rather than spontaneous, they may not capture the full variability of connected speech prosody in naturalistic contexts. Another limitation is that stress perception was not assessed. Although prior research suggest that children with CAS often exhibit typical phonetic perception abilities (), perceptual processing of prosodic features such as lexical stress may still differ and could influence pitch organization or declination. Future work incorporating perceptual as well as production measures will help clarify the perception-production interface in CAS prosody.

Several additional constraints narrow interpretation. First, diagnostic circularity remains a potential concern. Although segmentation was documented in the source clinical characterization, it was not used as an inclusion criterion in the present analyses, and all acoustic coding was completed by raters blinded to group. Nevertheless, partial overlap between diagnostic descriptors (e.g., segmentation, stress errors) and analytic outcomes cannot be fully excluded. To mitigate this, future studies should employ diagnostic protocols that are independent of the outcome measures being analyzed. Second, the absence of a non-CAS comparison group (e.g., children with phonological disorder or speech delay) limits claims of CAS-specificity. Without such a group, we cannot determine whether the observed effects are unique to CAS or reflect broader speech-motor or timing difficulties shared across disorders (). Third, group difference in language ability—as indicated by significantly lower CELF-5 Core Language scores for the CAS group—introduce the possibility that language-level planning rather than purely motor implementation contributed to the prosodic effects observed (; ). Future adaptations should balance or control for receptive and expressive language ability to separate these effects.

From a methodological perspective, declination analyses modeled word-indexed slopes (change in f0 per word). While this approach aligns with prior work examining across-utterance pitch downtrend (), complementary time-indexed analyses—such as those using segment-to-segment or word-onset intervals—may capture dynamic timing effects (). Explicit detection of f0 resets at phrase boundaries could also reveal whether pause-induced pitch resets contribute to the flattening observed in CAS. Longitudinal and intervention-based studies could further assess whether declination and segmentation evolve at different rates with treatment, clarifying whether learning can improve global pitch control independently of timing. Finally, cross-linguistic investigations would help determine whether prosodic structure and language typology modulate pausing, f0 range, and declination patterns in children with CAS (, ). Future work should extend validated acoustic metrics () from word-level to intonational-phrase level and across languages. Analyses of local f0 maxima and minima would help specify group differences in intonational contour shape and reveal potential edge effects or pitch resets. Continued investigation of prosody at multiple hierarchical levels, from the syllable to the utterance, is essential for understanding how timing and intonation are motorically planned, programmed and integrated in CAS.

5. Conclusions

Children with CAS demonstrated greater segmentation and reduced declination relative to TD peers when producing controlled connected speech stimuli. Lexical status and stress pattern influenced segmentation, with longer inter-segment durations for nonce words compared to real words and for iambic stress patterns compared to trochaic stress patterns, consistent with prior evidence of increased planning demands for less familiar and complex forms (; ; ). Differences in declination emerged with shallower word-indexed f0 slopes and higher utterance-final f0 in CAS, suggesting reduced global pitch decline across utterances. Notably, longer between-word pauses did not predict shallower declination slopes, indicating that temporal segmentation and global pitch organization may be governed by overlapping but distinct control processes (; ; ). Together, these findings refine the characterization of prosody in CAS by highlighting how timing and pitch interact, or dissociate, across prosodic levels. Future research should aim to disentangle the respective contributions of motor implementation and linguistic ability in prosodic planning, accounting for individual variability, cross-linguistic structure, and the inclusion of clinical comparison groups to strengthen diagnostic specificity.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/languages10120296/s1. Figure S1. Between-syllable segmentation sensitivity analyses 1. Results from the continuous outcome variable: average pause length between syllables in the target word (conditional on pause duration > 0). Note that averages may reflect a single pause or the mean of multiple pauses, depending on the participant’s production. Figure S2. Between-syllable segmentation sensitivity analyses 2. Results from the dichotomous outcome variable: model on clustering by target word. Note that averages may reflect a single pause or the mean of multiple pauses, depending on the participant’s production. Figure S3: Linear hypothesis tests. Linear hypothesis test results for all models reported in the manuscript, organized by section. All estimated effects and all pairwise comparisons between groups and subgroups are included.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.T., K.J.B., and D.A.R.; methodology, J.C.T., R.T.B., K.J.B., and D.A.R.; software, J.C.T.; validation, J.C.T. and J.M.F.; formal analysis, J.M.F. and J.C.T.; investigation, J.C.T. and R.T.B.; resources, J.C.T. and D.A.R.; data curation, J.C.T. and J.M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.T. and R.T.B.; writing—review and editing, J.C.T., R.T.B., J.M.F., K.J.B., and D.A.R.; visualization, J.M.F. and J.C.T.; supervision, J.C.T. and D.A.R.; project administration, J.C.T.; funding acquisition, J.C.T. and D.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by startup funds of the first and last authors from the College of Health and Human Services at the University of New Hampshire.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of New Hampshire (IRB-FY2022-178, March 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all legal guardians of participants involved in the study, and verbal assent was obtained from the child participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the authors pending institutional review approval due to the use of HIPAA confidential datasets.

Acknowledgments

The authors express thanks to the participants and their families who were part of the study. Thank you to the UNH CAT Lab for assistance with data coding and analysis, particularly Piper MacLean and Haley McCreight.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Portions of this work were presented at the 2019 American Speech-Language Hearing Association Convention in Orlando, Florida, as well as forming part of the second author’s master’s thesis at the University of New Hampshire.

References

- Arciuli, J., & Ballard, K. J. (2017). Still not adult-like: Lexical stress contrastivity in word productions of eight-to eleven-year-olds. Journal of Child Language, 44(5), 1274–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASHA. (2007). Childhood apraxia of speech (Technical report). American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Available online: https://www.asha.org/practice-portal/clinical-topics/childhood-apraxia-of-speech/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Ballard, K. J., Azizi, L., Duffy, J. R., McNeil, M. R., Halaki, M., O’Dwyer, N., Layfield, C., Scholl, D. I., Vogel, A. P., & Robin, D. A. (2016). A predictive model for diagnosing stroke-related apraxia of speech. Neuropsychologia, 81, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, K. J., Djaja, D., Arciuli, J., James, D. G., & van Doorn, J. (2012). Developmental trajectory for production of prosody: Lexical stress contrastivity in children ages 3 to 7 years and in adults. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 55(6), 1822–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, K. J., Halaki, M., Sowman, P., Kha, A., Daliri, A., Robin, D. A., Tourville, J. A., & Guenther, F. H. (2018). An investigation of compensation and adaptation to auditory perturbations in individuals with acquired apraxia of speech. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, K. J., & Robin, D. A. (2021). Speech motor programming intervention. In L. Williams, S. McLeod, & R. McCauley (Eds.), Interventions for speech sound disorders. Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, K. J., Robin, D. A., McCabe, P., & McDonald, J. (2010). A treatment for dysprosody in childhood apraxia of speech. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 53(5), 1227–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, K. J., Tourville, J. A., & Robin, D. A. (2014). Behavioral, computational, and neuroimaging studies of acquired apraxia of speech. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., Walker, S., Christensen, R. H. B., Singmann, H., Dai, B., Scheipl, F., & Grothendieck, G. (2011). Package ‘lme4.’ Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes (R Package Version 1.1-35).

- Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2018). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (Version 6.0.40) [Computer software]. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Box, G. E., & Cox, D. R. (1964). An analysis of transformations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology, 26(2), 211–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, S. (2010). How does informativeness affect prosodic prominence? Language and Cognitive Processes, 25(7–9), 1099–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A., & ‘t Hart, J. (1967). On the anatomy of intonation. Lingua, 19, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J. (2015). Prosody in context: A review. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 30(1–2), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, R. (1975). Physiological correlates of intonation patterns. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 58(1), 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, B., & Ladd, D. R. (1990). Aspects of pitch realisation in Yoruba. Phonology, 7(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, A., & Carter, D. M. (1987). The predominance of strong initial syllables in the English vocabulary. Computer Speech & Language, 2(3–4), 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankovičová, J. (1999, August 1–7). Articulation rate variation within the intonation phrase in Czech and English. 14th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (pp. 269–272), San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, J. R. (2013). Motor speech disorders: Substrates, differential diagnosis, and management (3rd ed.). Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J., & Weisberg, S. (2018). An R companion to applied regression. Sage publications. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=uPNrDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Fox+J,+Weisberg+S+(2019).+_An+R+Companion+to+Applied+Regression_,+Third+edition.+Sage,+Thousand+Oaks+CA.&ots=MxH4bI4t12&sig=3-U6U9sgmhd0c_UZS7GlTiao8PE (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Fujisaki, H. (2004, March 23–26). Information, prosody, and modeling-with emphasis on tonal features of speech. Speech Prosody 2, Nara, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Garnier, S., Ross, N., Rudis, R., Camargo, P. A., Sciaini, M., & Scherer, C. (2023). Viridis(Lite)—Colorblind-friendly color maps for R (Version viridis package version 0.6.4) [Computer software]. Available online: https://sjmgarnier.github.io/viridis/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Goldman, R. (2000). Goldman-Fristoe test of articulation (GFTA). American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Guenther, F. H. (2016). Neural control of speech. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halekoh, U., & Højsgaard, S. (2014). A kenward-roger approximation and parametric bootstrap methods for tests in linear mixed models–the R package pbkrtest. Journal of Statistical Software, 59, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberg, J., & Pierrehumbert, J. (1986, July 10–13). The intonational structuring of discourse. 24th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 136–144), New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Højsgaard, S., Halekoh, U., & Yan, J. (2006). The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. Journal of Statistical Software, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Iuzzini-Seigel, J., Hogan, T. P., & Green, J. R. (2017). Speech inconsistency in children with childhood apraxia of speech, language impairment, and speech delay: Depends on the stimuli. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60(5), 1194–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jusczyk, P. W. (1999). How infants begin to extract words from speech. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 3(9), 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusczyk, P. W., Cutler, A., & Redanz, N. J. (1993). Infants’ preference for the predominant stress patterns of English words. Child Development, 64(3), 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A. (2018). Ggpubr:’ggplot2’based publication ready plots (R Package Version 0.6.1).

- Kent, R. D., & McNeil, M. R. (1987). Relative timing of sentence repetition in apraxia of speech and conduction aphasia. In Phonetic approaches to speech production in aphasia and related disorders (pp. 181–220). Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, R. D., & Rosenbek, J. C. (1983). Acoustic patterns of apraxia of speech. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 26(2), 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenward, M. G., & Roger, J. H. (1997). Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics, 53, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopera, H. C., & Grigos, M. I. (2020). Lexical stress in childhood apraxia of speech: Acoustic and kinematic findings. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 22(1), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, D. R. (1984). Declination: A review and some hypotheses. Phonology, 1, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, D. R. (2008). Intonational phonology. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levelt, W. J. M. (1993). Speaking: From intention to articulation. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, P. (1967). Intonation, perception, and language. MIT Research Monograph. [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn, M., & Maas, E. (2025). Acoustic measures of word-level prosody in childhood apraxia of speech: An initial validation study. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 34(4S), 2485–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, E., Robin, D. A., Wright, D. L., & Ballard, K. J. (2008). Motor programming in apraxia of speech. Brain and Language, 106(2), 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansournia, M. A., Geroldinger, A., Greenland, S., & Heinze, G. (2018). Separation in logistic regression: Causes, consequences, and control. American Journal of Epidemiology, 187(4), 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, G., Massimiliano, B., & Paolo, B. (2008). Prosody and Broca’s aphasia: An acoustic analysis. Studi Linguistici e Filologici Online, 6, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, M. R., Robin, D. A., & Schmidt, R. A. (1997). Apraxia of speech: Definition, differentiation, and treatment. In M. R. McNeil (Ed.), Clinical management of sensorimotor speech disorders (pp. 311–344). Thieme. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, H. E., Ballard, K. J., Campbell, J., Smith, M., Plante, A. S., Aytur, S. A., & Robin, D. A. (2021). Improvements in speech of children with apraxia: The efficacy of Treatment for Establishing Motor Program Organization (TEMPOSM). Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 24(7), 494–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H. E., & Guenther, F. H. (2021). Modelling speech motor programming and apraxia of speech in the DIVA/GODIVA neurocomputational framework. Aphasiology, 35(4), 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A. T., Murray, E., & Liegeois, F. J. (2018). Interventions for childhood apraxia of speech. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5, CD006278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E., McCabe, P., & Ballard, K. J. (2015a). A randomized controlled trial for children with childhood apraxia of speech comparing rapid syllable transition treatment and the nuffield dyspraxia programme—Third edition. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(3), 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E., McCabe, P., Heard, R., & Ballard, K. J. (2015b). Differential diagnosis of children with suspected childhood apraxia of speech. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(1), 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nespor, M., & Vogel, I. (2007). Prosodic phonology: With a new foreword. Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Odell, K. H., & Shriberg, L. D. (2001). Prosody-voice characteristics of children and adults with apraxia of speech. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 15(4), 275–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohala, J. J. (1978). Production of tone. In Tone (pp. 5–39). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, M., Jr. (2003). Pitch reset as a cue for narrative segmentation. Evaluation, 3(4), 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Paik, M. C. (1988). Repeated measurement analysis for nonnormal data in small samples. Communications in Statistics—Simulation and Computation, 17(4), 1155–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppé, S. (2007, August 6–10). Prosodic boundary in the speech of children with autism. 16th International Congress of the Phonetic Sciences, Saarbrücken, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrehumbert, J. (1980). The phonetics and phonology of English intonation [Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology]. [Google Scholar]