Abstract

In Peru, large-scale migration from the provinces to Lima in the second half of the twentieth century has created a context of intense language and dialect contact. This study examines /s/ variation among migrants from the Andean region, where Quechua, Aymara, and varieties of Andean Spanish—shaped through long-standing contact with these indigenous languages—are spoken. We analyze the speech of 59 participants representing “classic Limeños,” whose families have lived in Lima for several generations, and three generations of Andean migrants, using corpora collected in 1999–2002 and 2012–2013 to trace linguistic change in apparent time. Univariable analyses show significant generational differences: as distance from migration increases, aspiration becomes more frequent and elision declines, while [s] remains relatively stable after the first generation. Multivariable models incorporating migrant generation, family origin, neighborhood, education, and sex reveal that while a combined variable of migrant generation and family origin is significant, neighborhood, education, and sex are stronger predictors. Speakers from established neighborhoods, those with university education, and female speakers favor aspiration and [s], aligning with prestige norms. Mixed-effects logistic regression of linguistic variables confirms structured sociolinguistic change: the following segment is the strongest linguistic predictor, and there is a clear intergenerational shift from elision toward aspiration. However, constraint hierarchies—especially following segment and stress—remain stable, indicating change in rates rather than in linguistic conditioning.

1. Introduction

Migration often results in language and/or dialect contact and, as a consequence, can play a significant role in language change. In Peru, migration from rural areas to urban centers, especially to the capital city of Lima, has been a major factor in demographic change in the second half of the twentieth and into the twenty-first century. Internal migration between 1950 and 1980 resulted from immense population growth in rural areas that brought migrants to urban areas in search of better economic and educational opportunities (Fernández-Maldonado, 2014). The 1980s and early 1990s saw a sharp increase in internal migration due to the internal conflict with the Shining Path insurgency, which led to widespread violence and instability in rural areas. The resulting demographic shifts over the past eighty years have transformed Lima and brought speakers of Andean Spanish, a variety that has been influenced by Quechua and Aymara, into contact with coastal Limeño Spanish.

One of the salient phonetic differences between Andean Spanish and the Spanish of Lima is the pronunciation of syllable final /s/. In Andean Spanish, /s/ is almost always pronounced as a sibilant (Hundley, 1983), while in Lima /s/ weakening occurs (Caravedo, 1983). While the sibilant is still the most commonly produced variant in coda position in Lima, social factors influence the distribution of the aspirated ([h]) variant and elision (Ø) (Caravedo, 1983, 2009). The current study is an analysis of the social and linguistic factors that condition sibilant variation in Lima. By examining the sibilant productions of 59 participants representing “classic Limeños,” whose parents and grandparents were born in Lima, as well as three generations of migrants from the Andean provinces, we seek to determine how the distribution of /s/ weakening has evolved in a situation of intense dialect contact. In the following sections, we provide an overview of the literature on sibilant weakening in Peruvian Spanish and the social and linguistic factors that condition it. We then move to a description of our study and the methods that were employed in our analysis, followed by a presentation of the results, the discussion, and conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sibilant Weakening in Spanish

As a sociophonetic phenomenon in Spanish, coda /s/ weakening has been extensively studied in a number of varieties across the Spanish-speaking world (See Núñez-Méndez, 2022 for a summary). Lipski (2011) states that sibilant weakening occurs in more than half of all the dialects of Spanish. The historical origins of /s/ weakening date back centuries with some scholars (Alvar, 1955; Frago Gracia, 1983; Seklaoui, 1989) asserting that /s/ reduction began in Latin. Others (Lapesa, 1942; Lipski, 1984; Lloyd, 1987; among others) cite evidence from 15th and 16th century Spanish manuscripts suggesting that sibilant weakening in coda-final position dates from that period in which the Spanish sibilant paradigm underwent major changes that resulted in a reduced inventory of phonemes. Although the historical emergence of /s/ weakening is in dispute, it appears likely that by the first half of the sixteenth century aspiration of /s/ was common in Andalucia, Spain (Romero, 1995). According to Lipski (1984), as sibilant weakening spread within different Spanish-speaking groups, it most likely was a gradual process that started in syllable-final position before consonants. A wide variety of factors, both language-internal and social, have been shown to influence this phenomenon. In the sections that follow, we will briefly review the studies that are most relevant to our research.

2.1.1. Geographic and Social Factors

In Latin American Spanish, Penny (2000) has noted that the geographical division in regions where coda /s/ is usually retained vs. those where /s/ weakening is common has a sociopolitical and economic basis that dates from the early years of Spanish colonization. Penny (2000, pp. 148–149) states that “those areas which, because of their political and economic importance in the Empire, attracted prestigious speakers of central Castilian varieties are the ones that retain /-s/ most frequently (most of Mexico, much of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia).” The geographical areas in Latin America where coda /s/ undergoes intense weakening or loss are those where central Castilian varieties were less prevalent during the colonial period, i.e., the Caribbean, the Pacific coast, and the southern Cone. Although Lima is on the Pacific coast, it was the seat of the richest viceroyalty and maintained sustained contact with Spain throughout the colonial period. As a result, Penny (2000) believes that /s/ weakening may be a relatively recent change from below in Lima given its patterns of distribution.

Escobar (1978) observed that the retention of /s/ as a sibilant in coda position distinguished Andean Spanish from coastal Peruvian varieties in the latter half of the twentieth century. This is confirmed in Hundley’s (1983) quantitative study in which he examined sibilant variation across a number of factors in spontaneous Andean Cuzqueño and Limeño Spanish produced by males between the ages of 50 and 65. As can be seen in Table 1, his results indicate that the Andean speakers rarely reduced /s/ (only 3.1%) while the speakers from Lima reduced the sibilant at notably higher levels (41.7%). When speakers in Cuzco did reduce /s/, they deleted slightly more than they aspirated (1.9% vs. 1.2%), while the opposite was true in Lima, where speakers aspirated notably more than they elided (24.7% vs. 17.0%).

Table 1.

Distribution of /s/ in Lima and Cuzco (created from data in Hundley, 1983).

As part of the Proyecto de la norma culta hispánica, Caravedo (1983, 1989, 1990) conducted a large-scale sociolinguistic study of Limeño Spanish. In her analysis of sibilant variation in Lima (Caravedo, 1990), she found that both the upper-middle and working class produced [s] with relatively similar frequency (74.1% and 72.7%, respectively). However, she reported notable differences between these two groups with respect to aspiration and elision. Among upper-middle class speakers, aspiration was much more frequent than elision (15.3% vs. 4.4%), while elision rates were higher in working-class speakers than aspiration (11.3% vs. 6.0%), as illustrated in Table 2.1

Table 2.

Distribution of /s/ variants by social class in Lima (adapted from Caravedo, 1990, p. 136).

Consistent with what has been reported for other dialects of Spanish (Cedergren, 1978; Lafford, 1986; Samper, 1990; and others), Caravedo (1987) found production differences based on gender and age, albeit in the case of Lima, the differences were small: women produced the sibilant more than men (79% vs. 77%) and elided less than men (4% vs. 5%). Younger speakers also tended to aspirate more and elide less than older generations.

Klee and Caravedo (2006) introduced for the first time the concept of migration or demographic mobility as an important factor in the analysis of linguistic variation and change in Lima. Their study sought to determine whether the migration of Andean speakers to the capital city influenced the direction of linguistic change. In a pilot study, they compared the Spanish of classic lower middle class Limeños, i.e., residents of Lima whose parents and grandparents were also born in Lima, with that of first- and second-generation migrants living in long-established shantytowns. One of their most notable findings was that of all the social factors that were connected to /s/ variation, migrant status was the most important when comparing elision and aspiration, followed by gender. They report that the adult children of Andean migrants elided /s/ at higher rates than classic Limeños. They also show that men elided more than women, which is similar to Caravedo’s (1990) results. Klee & Caravedo also indicate that elision was more common among the migrants than the classic Limeños because the primary model of Limeño Spanish to which migrants and their children were exposed is that of working class speakers, who have been shown in previous studies (Caravedo, 1990) to exhibit the highest levels of elision in Lima. Migrant generation was not a factor when comparing elision and aspiration, as both the first and second generations showed similar levels of deletion.

Klee et al. (2018) examined /s/ weakening in second- and third-generation speakers who lived in the Limeño neighborhood of Los Olivos, which is one of Lima’s most prosperous migrant districts. Using a proportional odds model to analyze their data, they report that the most important social factor connected with /s/ variation among second- and third-generation speakers in this specific neighborhood was migrant generation, with a progressive increase in /s/ weakening between second- and third-generation speakers, while higher levels of education correlated with less sibilant reduction. They assert that these results are indicative of a possible accommodation by speakers, especially of the third generation, to coastal Limeño norms of sibilant reduction, effectively distancing themselves from the sibilant conservancy of their Andean predecessors. However, they also propose the possibility that these speakers may be forming their own norm.

Finally, Klee and Caravedo (2020) reported on the partial results of an analysis of /s/ variation in 108 participants from three migrant generations and a group of classic Limeños. They focused solely on the results for two social variables: migrant generation and origin. They found that there were no significant differences between second- and third-generation migrants and classic Limeños in /s/ production, although all three groups were significantly different than first-generation speakers, who produced higher rates of the sibilant. In regard to origin, there were no significant differences based on the origin of participants’ families, confirming that second- and third-generation speakers had adopted coastal norms in the production of the sibilant vs. weakening in coda position.

2.1.2. Language-Internal Factors Associated with Sibilant Weakening in Spanish

A number of studies on different dialects have indicated that Spanish sibilant weakening occurs at higher rates depending on the phonetic and phonological contexts. Terrell (1979) indicated that word-final tokens were reduced more frequently in Cuban Spanish if they preceded a consonant or a vowel, with tokens preceding consonants reduced or deleted the most. When preceding a pause, the levels of sibilant retention increased significantly. These findings are supported by numerous other studies of various dialects that have found that sibilants that precede vowels and pauses are conserved at higher rates than those preceding consonants (e.g., Mason, 1994; Lipski, 1995; Cepeda, 1995; Cid-Hazard, 2003; Fox, 2006; among others). Preceding segments have not been shown to have as much of an influence on sibilant conservation or reduction, although E. K. Brown (2009a) indicates that preceding high vowels potentially can contribute to higher levels of /s/ conservation.

In Lima, Caravedo (1990) found that [s] occurred most frequently before a vowel or a pause and was especially prevalent in the speech of upper-middle class speakers (98.6% and 92.8%) in contrast to the working class, where [s] occurred in prepausal position only 57.6% of the time, as seen in Table 3 and Table 4 below. Aspiration occurred primarily before a consonant in both social groups (44.5% in the upper-middle class vs. 14.4% in the working class). Elision was most frequent before a consonant (24.5%) and before a pause (23.1%) in the working class, but occurred less frequently and primarily before a consonant (11.9%) in upper-middle class speech.

Table 3.

Production of /s/ in word final position in the working class (Caravedo, 1990, p. 137).

Table 4.

Production of /s/ in word final position in the upper-middle class (Caravedo, 1990, p. 137).

Word length, or whether a word is mono- or polysyllabic, also has a documented role in /s/ reduction in Spanish. Various studies have shown that sibilant reduction occurs more in polysyllabic words (e.g., Terrell, 1978; Cepeda, 1995; Cid-Hazard, 2003; among others). Guitart (1982, 1983) asserts that sibilants in longer words are potentially not produced with as much available energy as those in shorter words. However, File-Muriel and Brown (2011) indicate that in Colombian Caleño Spanish, word length does not appear to affect /s/ weakening. Guitart (1983) also states that unstressed syllables favor reduction as well, due to speakers producing these syllables with less physical effort or energy. Similarly, E. L. Brown and Torres Cacoullos (2002, 2003), File-Muriel and Brown (2011), and Hoffman (2001) indicate that reduction is more frequent in unstressed syllables. Lexical frequency has also been identified as a significant predictor of /s/ weakening, with /s/ more likely to be reduced in more frequent words (E. K. Brown, 2009b; Bybee, 2002; File-Muriel & Brown, 2011; among others). Nonetheless, frequency does not have the same effect across all varieties of Spanish (E. K. Brown, 2009a; E. K. Brown et al., 2014).

2.2. Migration, Demographics, and Linguistic Change in 20th and 21st Century Lima

Given that migration is a central factor in our analysis, it is important to understand the shifting demographics and resulting linguistic changes that have occurred since the middle of the 20th century in Lima. During the second half of the 20th century, the population of Lima increased dramatically, principally as a result of a large increase in migration to Lima from the provinces. While in 1940 its population comprised 13 percent of Peru’s population, by 2005 it encompassed 30 percent of the country (Alcázar & Andrade, 2008). According to Arellano Cueva and Burgos Abugattas (2004), by the early 21st century, the vast majority of the population of Lima was made up of migrants from the provinces (36%), their children (43.5%), and their grandchildren (8%). Classic Limeños only made up 13% of the total population. It might be expected that with this vast demographic imbalance, some of the features of Andean Spanish would be maintained cross-generationally and perhaps even integrated into classic Limeño Spanish. This has not generally occurred, though, due to the largely negative reception of migrants by the classic Limeños, stigmatizing migrants based on their origin, socioeconomic status, culture, and language. As a result of this discrimination, migrants who speak indigenous languages tend to abandon them as they become more fluent in Spanish, consequently severely limiting the extent to which their mother tongues are taught and transferred to subsequent generations (Marr, 1998). In addition, Andean Spanish, which has been influenced by indigenous languages, is stigmatized and speakers of that variety often evaluate their own Spanish as “incorrect” (Caravedo, 2014; Salcedo Arnaiz, 2013). As a result, despite the overwhelming majority of the population having at least grandparents of Andean origin, many of the more characteristic features of Andean Spanish, such as assibilated /r/ and the voiced palatal lateral /ʎ/, are limited to the first-generation speakers, with speakers of subsequent generations adopting Limeño features such as the trilled /r/ and the voiced palatal fricative (Klee & Caravedo, 2006). Similar circumstances and results have been reported in migrant populations in Madrid, Spain (Martín Butragueño, 2004) and Mexico City (Serrano, 2000).

The current study focuses on differences between classic Limeños and three different migrant groups in Lima, taking into account social and linguistic factors. Specifically, the present investigation seeks to determine whether migrants and their descendants exhibit high levels of sibilant maintenance, a characteristic feature of Andean Spanish, or if they accommodate to the coastal norms of /s/ weakening. Likewise, linguistic factors are analyzed to better understand how coda /s/ weakening or retention is conditioned across different migrant generations. The research questions that guide our research are the following:

- (1)

- Do the children and grandchildren of Andean migrants maintain the coda /s/ production patterns of first-generation Andean migrants, or do they accommodate to the sociophonetic norms of classic Limeños?

- (2)

- What other social factors condition coda /s/ weakening in Lima, Peru?

- (3)

- What linguistic factors condition /s/ variation in word final position? Do these differ across migrant generations?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participant Selection

The data were gathered from 59 participants from two different corpora of sociolinguistic interviews conducted in different neighborhoods in Lima, as part of the research project Language Change as a Result of Andean Migration to Lima, Peru begun in 1999 by Klee and Caravedo. Participants were divided into three different migrant generations. First generation participants were individuals born in an Andean region of Peru who migrated to Lima after the age of seven. Second generation migrants were those who were born in Lima and who had at least one first generation parent. Third generation migrants were also born in Lima and had at least one first generation grandparent and second generation parent. “Classic” Limeños, or those born in Lima who did not have migrant parentage for at least three generations were labeled as the 4th generation. The first corpus was gathered in 1999–2002 in both traditional Limeño neighborhoods and more established migrant settlements by fieldworkers who were familiar with or resided in the area of the city in which they conducted interviews. In all, the first corpus comprised 82 participants, of which 20 were from traditional Limeño neighborhoods, 62 were from older migrant settlements. The second corpus consisted of 26 interviews gathered in 2012–2013 from the established migrant neighborhood of Los Olivos by a fieldworker from the community. Los Olivos is unique among other migrant neighborhoods because it is the most affluent of these neighborhoods in the northern metropolitan area of Lima and it is made up of several generations of immigrants. The overall population of Los Olivos is 365,921 (INEI, 2014) and is relatively young with a mean age of around 29 years old. Unlike the majority of other migrant settlements, residents of Los Olivos enjoy more upward social mobility and more educational opportunities. Overall, 21% of Los Olivos is considered to be upper-middle or middle class (Alcázar & Andrade, 2008), a high number for a district made up of primarily migrants, although there still are notable rates of poverty (37%) among first generation Andean migrants on the outskirts.

A subset of the corpus was analyzed to balance the number of participants by generations. Fifteen participants were selected from generations one, two, and three as well as 14 classic Limeños, labeled “fourth generation.” The social variables taken into account include Migrant Generation, Family Origin, Neighborhood, Biological Sex, and Education. There is some degree of correlation between migrant generation and some of the other social variables. In terms of family origin, all first-generation (G1) participants are of Andean origin; second-generation (G2) participants are either of Andean or mixed origin; third-generation (G3) participants represent all three categories—Andean (4), mixed (6), and non-Andean (5); and, fourth-generation (G4) participants are exclusively of non-Andean origin. With respect to neighborhood distribution across migrant generations, all G1 participants reside in shantytowns. Among G2 participants, 11 live in shantytowns and 4 in Los Olivos. In G3, the majority (10) reside in Los Olivos, while 3 live in shantytowns, and 2 in established neighborhoods. In G4, 13 participants live in established neighborhoods and 1 in Los Olivos. Efforts were made to balance gender representation; however, G4 includes a disproportionate number of women (11) compared to men (3). Regarding educational attainment, G1 is the only generation with participants (8) who have only primary education, and none who have received technical or higher education. See Table A1 in the Appendix A for the social characteristics by migrant generation and Table A2 in the Appendix A for the social characteristics of each participant.

3.2. Data Measurement and Instruments

The larger Lima corpus was coded impressionistically for [s], [h] and Ø in coda position, in both word-internal ([’mues.tra]) and word final phonetic contexts ([sa. ’li.mos]), as has been done in the vast majority of similar studies on Spanish /s/ variation, primarily due to the perceptual salience between categories (e.g., Cepeda, 1990; Caravedo, 1990; Hundley, 1983; Klee & Caravedo, 2006; among many others). Consecutive orthographic representations of /s/ (e.g., {los sordos}) and instances of [h] followed by [x] (e.g., [loh.’xu̯e.ɣ̞os]) were excluded. For each speaker, 200 tokens were coded after the 10 minute mark in the interview, when the speakers were more acclimated and comfortable with the interviewer and the overall conversation, for an overall total of 8798 tokens2 from 44 speakers. One of the difficulties coding for /s/ is how quickly background noise can alter or overlap the acoustic signal, making it impossible at times to accurately code /s/. Thus, in cases where background noise was too high, the coders skipped forward to where there was no more background interference in the recordings and continued to code. Files that had too much ambient noise throughout were excluded from the sample size. After being coded, two linguists impressionistically verified the coding. Afterwards, for purposes of inter-rater reliability, a third linguist, using Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 2023) acoustically verified a random sample of 589 tokens to compare to the impressionistic results. The overall rate of agreement between the impressionistic and acoustic verifications regarding the classification of each instance of /s/ (i.e., [s], [h] or elision) was 77.6%.

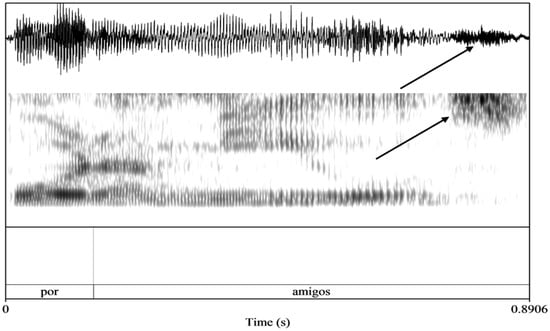

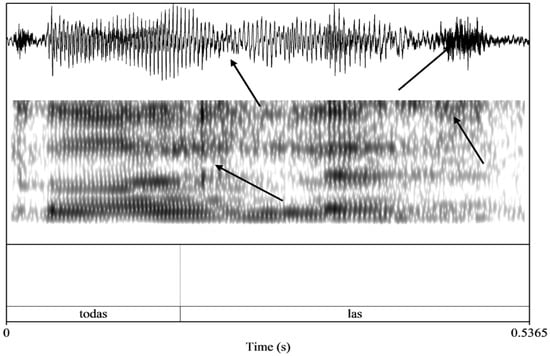

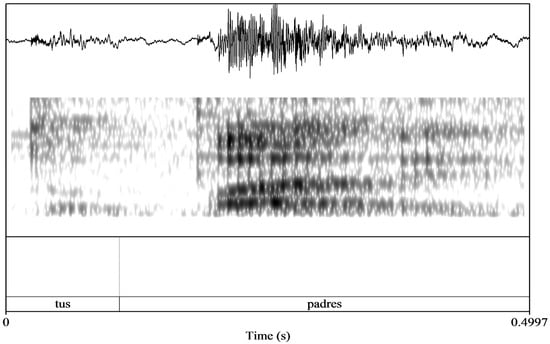

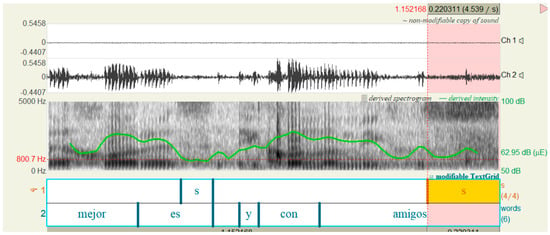

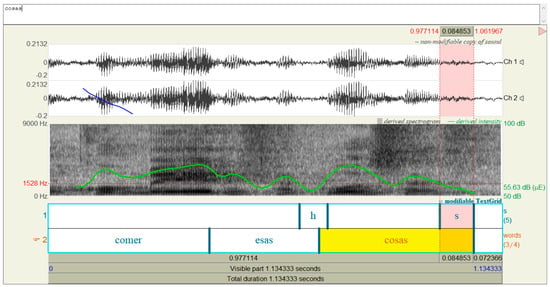

The Los Olivos data were coded acoustically using Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 2023) for the same three allophonic variants of /s/ in the same phonetic contexts as the larger Lima corpus. 201 tokens of /s/ were coded per speaker after the 10 minute mark of each interview for an overall total of 3015 tokens from 15 speakers. Several methods were used to classify /s/ as either a sibilant, aspirated, or elided. First, the sibilant was considered to be present when aperiodicity was observed in waveform along with turbulence in the spectrogram. Aspiration was determined based on the presence of glottalized turbulence, or glottalization, in the spectrogram. The turbulence that is indicative of sibilants differs from that of [h] principally along the lines of how it is distributed in the spectrogram as a result of the different manners of articulation of each segment. When [s] is produced, generally, the blade of the tongue approximates or makes contact with the alveolar ridge, resulting in greater constriction of the airflow from the lungs. As a consequence, especially in the upper limits of the spectrogram, a great deal of strong and strident turbulence is observable. The aspirated [h] is articulated with a notably lesser amount of oral constriction and thus does not result in the same strong and strident turbulence that is characteristic of [s]. Turbulence characteristic of [h] is weaker and more evenly distributed throughout the observable spectrogram. Tokens were coded as elided if there was no visible evidence of turbulence or glottalization and no aperiodicity in the waveform. These criteria were also used during the acoustic verification of the larger corpus. Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate how [s], [h] and Ø were acoustically verified. Figure 1 is a case of [s] and the arrows indicate the presence of strident turbulence in the spectrogram and aperiodic waves in the waveform. In Figure 2, [h] is observed, with the arrows denoting the spectral turbulence and aperiodicity typical of the voiceless glottal fricative. Figure 3 is an example of elision with no observable evidence of sibilancy or aspiration at the end of the words “tus” and “padres”.

Figure 1.

Example of [s] according to the criteria used in the current study.

Figure 2.

Example of [ɦ] (voiced [h]) and [s] according to the criteria used in the current study.

Figure 3.

Two instances of elided /s/ according to the criteria used in the current study.

Even though tokens were grouped into three distinct categories, it must be noted that phonetic variation in each category was observed in both corpora. In addition to the [s], [h], and elision the following allophones were also observed: [ɦ] (voiced glottal fricative, i.e., [’miɦ.mo]), [x] (voiceless velar fricative, i.e., [’max.ke]), [z] (voiced alveolar fricative, i.e., [’miz.mo]), [ʔ] (glottal stop, i.e., [’ko.saʔ],), and [θ] (voiceless interdental fricative, i.e., [miθ.’ko.sas]), and [ɸ] (voiceless bilabial fricative, i.e., [loɸ. ’po.βɾes]). The following allophones were categorized as [s]: [s], [s̺], [θ], [ʃ], [z], [ˢ] (weakened voiceless alveolar fricative), and [z] (weakened voiced alveolar fricative). The following segments were categorized as [h]: [h], [ɦ], [ɸ], [h] (weakened voiceless glottal fricative), and [ɦ] (weakened voiced glottal fricative). It must be noted that in instances of [z] and [ɦ], because these segments are generally fully voiced, the aperiodic oscillations normally present in voiceless productions were frequently absent in the waveform, and as a result, the spectrographic turbulence patterns were used to confirm their presence. Elision occurred where there was no evidence of [s] or [h] or in cases where /s/ was realized as a glottal stop. In all, 11,813 tokens of /s/ were coded.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Separate analyses were conducted for the social and linguistic variables. The analysis of the social variables included a total of 11,813 /s/ tokens, comprising both word-internal and word-final positions. Word-internal tokens were included in the analysis of social variables as the following segment in that position is always a consonant. Previous studies have shown that coda /s/ weakening originates in preconsonantal environments both diachronically and synchronically (Núñez-Méndez, 2022). To determine whether the degree of /s/ weakening changes across migrant generations, preconsonantal environments, both internal and final, were particularly important to include in the analysis. In contrast, the analysis of the linguistic variables focused exclusively on word-final /s/, in line with previous literature (see Section 2.1.2). This restriction is methodologically justified, as only in word-final position can coda /s/ be followed by a vowel or a pause, segments that have been shown to significantly condition the realization of coda /s/. Limiting the analysis to this position allows for a more precise examination of the phonological factors influencing /s/ weakening.

Originally we used a proportional-odds (ordinal regression) mixed effects model of the social and linguistic variables separately. We selected this approach because although /s/ was coded categorically in our study, phonetically it exists along an acoustic continuum. Within the framework of a proportional odds model, the researcher is able to model an ordered, or categorically coded, dependent variable while assuming that there is variation and continuity with categories. The model accomplishes this by restricting its overall complexity based on the assumption that the categories respond in similar manners to changes in the independent variables. The model assumes that for /s/, the true underlying acoustic value, represented as ψ, can only be captured by way of observable ordinal categories. In other words, the sibilant undergoes weakening along an assumed continuum within its category before it is considered [h]. The aspirated variant must also weaken before being considered elided. An analysis that makes the overarching assumption that [s], [h], and Ø are unordered categories, does not take into account the natural ordering of the response.

One of the reviewers raised a concern regarding our use of ordinal regression, noting that while the model appropriately captures the ordered nature of /s/ variants in terms of articulatory constriction, it may not reflect the indexical social meanings associated with these variants. Specifically, the reviewer pointed out that aspiration [h], despite being less constricted than sibilance [s], may carry greater prestige due to its association with middle-class Limeño Spanish. We acknowledge that the relative social prestige of [s] versus [h] in Lima remains an open empirical question. Nevertheless, we took this critique seriously and evaluated the suitability of the ordinal model. Our diagnostics revealed that the ordinal regression model applied to social variables exhibited poor fit and limited explanatory power. In contrast, the ordinal model for linguistic variables (e.g., phonological environment) demonstrated strong predictive performance, suggesting that ordering is more appropriate in that domain. Consequently, we adopted a multinomial regression with mixed effects for the analysis of social factors, although we begin our analysis with a univariable model with just migrant generation as it is the variable of interest. We then see how those results change in a multivariable model with the other social factors. All computations were performed using R version 4.5.1 (13 June 2025) (R Core Team, 2025). We tested multiple model configurations to identify the best-fitting structure, including one that combined migrant generation and family origin to address collinearity, as suggested by the referee. The final model was selected based on its superior performance across several metrics—Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and residual deviance—as well as its predictive accuracy. These diagnostics collectively support the robustness of the model presented in the results section and its ability to capture the sociolinguistic patterns in the data more effectively than alternative approaches.

The goal of the current study, as is the case with many sociolinguistic investigations, was to generalize to the extent possible for a larger population in Lima. Therefore, random effects were studied to better comprehend the variability of the populations used. Thus, the effect of individual variation on the data is taken into account by including speaker as a random effect in the model.

Analysis of the Linguistic Variables

For the linguistic variables, we focused on factors that have been shown to be relevant in previous studies cited in the review of the literature section of this paper:

- Position of syllable-final /s/ in the word: internal or final. For the analysis of linguistic factors that condition variation, we focused only on /s/ in word final position.

- Following segment, coded as vowel, pause, voiceless consonant or voiced consonant.

- Preceding segment. For the analysis only two categories were included (i.e., high vowels and non-high vowels) as there were only 143 consonants in preceding position out of 11,813 tokens.

- Prosodic stress of the syllable containing /s/, coded as tonic or atonic.

- Word length, coded as monosyllabic or polysyllabic.

Three separate models were developed to compare the production of the four migrant generations: (1) the first was an ordinal model with all three variants, i.e., [s], [h], and Ø; (2) the second was a logistic model comparing the production of /s/ as a sibilant vs. weakened variants; and (3) the third was a logistic model comparing aspiration and elision. Each of the three models was fit for word final coda /s/ by migrant generation. A random effect for speaker was included. To test the fit of each model, estimated marginal means were computed for the probability of each response for each variable. Averages, weighted by the proportions present in the data, were used over the predicted values of other variables. Although—as mentioned above—the ordinal model demonstrated good predictive performance, the two logistic models, one of the sibilant vs. the weakened variants and the other comparing aspiration and elision, demonstrated the best fit and are presented below. Two additional logistic models were developed to determine whether the effects of the linguistic constraints were consistent across the four generations.

4. Results

As can be seen in Table 5, the sibilant was the most common production overall, comprising 61.5% of the tokens. Elision was the next most common variant with 21.2% of the realizations of /s/, followed by aspiration with 17.3%. In comparison with Caravedo’s (1990) study, there are lower levels of sibilant production and higher levels of elision.

Table 5.

Overall number and percentage of /s/ variants.

4.1. Social Factors

4.1.1. Univariable Model

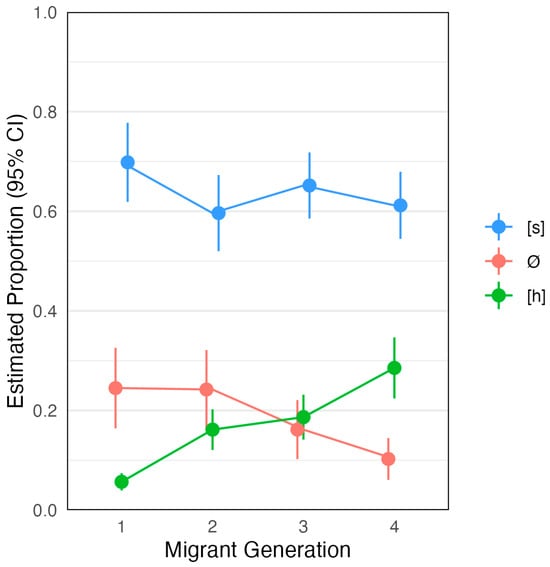

Because migrant generation is of primary interest, we first fit a univariable model with migrant generation alone to estimate the probabilities of [s], [h], and elision, with elision specified as the reference category. The resulting coefficients indicate how each independent variable affects the log-odds of producing aspiration [h] or a retained sibilant [s] relative to elision. Positive coefficients indicate an increase in the log-odds—and therefore in the likelihood—of the corresponding outcome relative to elision, while negative coefficients indicate a decrease. The reference group is the first generation. The coefficients presented in Table 6 were used to calculate the estimated marginal means shown in Figure 4, which reveal a clear generational trend: as the generation increases from first to fourth, the proportion of aspiration rises, while the proportion of elision declines. Both first- and second-generation speakers use a higher proportion of elision than aspiration, while in the third generation the proportion of aspiration and elision is similar. In contrast, classic Limeños produce a higher proportion of aspiration than elision. The proportion of [s] is slightly higher in generation 1 but otherwise is similar across the four groups.

Table 6.

Fixed effect coefficients from univariable model with migrant generation only.

Figure 4.

Estimated proportion of [s], [h], and elision across generations.

The overall differences between the migrant generations are statistically significant, as indicated in Table 7. Pairwise comparisons presented in Table 7 reveal that the only difference that was not statistically significant was between the second- and third-generation speakers; we can see in the figure that they share similar patterns of /s/ realization. In contrast, both generations differ significantly from first-generation Andean migrants and classic Limeños, indicating that while second- and third-generation speakers have begun to diverge from the speech of the first generation, they have not yet fully converged with the sociophonetic norms of long-established Limeño residents.

Table 7.

Overall tests and pairwise comparisons from univariable multinomial model with migrant generation only.

4.1.2. Multivariate Analysis

Given the strong association between migrant generation and other social variables, we fitted a multivariable model that incorporated migrant generation and family origin (as a combined variable), along with neighborhood, education level, and biological sex. This approach allowed for a more nuanced analysis of the social factors underlying generational differences in /s/ realization. We used a multinomial logistic regression to estimate the probabilities of producing [s], [h], or elision, specifying elision as the reference category. The model coefficients capture the effect of each predictor on the log-odds of producing aspiration [h] or a retained sibilant [s] relative to elision. Importantly, all coefficients are interpreted while holding the other predictors constant, isolating the independent contribution of each social factor to the probability of variant selection. Positive coefficients indicate an increased likelihood of selecting the corresponding variant over elision, whereas negative coefficients indicate a decreased likelihood. The intercept represents the log-odds for the reference group (Gen 1_Andean, Female, Primary Education, Shantytown).

The multinomial regression analysis reveals that all four social factors tested significantly influence the realization of coda /s/ in Lima, as shown in Table 8. However, the most important variables in conditioning /s/ variation are neighborhood, education and biological sex. In regard to neighborhood, speakers from established neighborhoods are markedly more likely to produce aspiration (Estimate = 1.923) and the sibilant (Estimate = 1.493) compared to elision, suggesting closer alignment with middle-class speech norms, as documented by Caravedo (1990). Similarly, higher education levels correlate with increased use of [h] and [s], with university-educated speakers showing the strongest effect (Estimate = 1.390 for [h]; Estimate = 0.938 for [s]). Male speakers are less likely to produce either [h] (Estimate = −0.402) or [s] (Estimate = −0.711) than females, favoring elision. Migrant origin also plays a role: second- and third-generation migrants, and classic Limeños show reduced likelihood of producing [s] compared to elision in comparison to first-generation Andean migrants. In contrast, the estimates for aspiration [h] among migrant groups are generally low and inconsistent, suggesting that while high rates of [s] are strongly indexical of first-generation Andean speakers, [h] may be adopted more variably across generations.

Table 8.

Fixed effect coefficients (SE) from the multivariable multinomial model with social variables only.

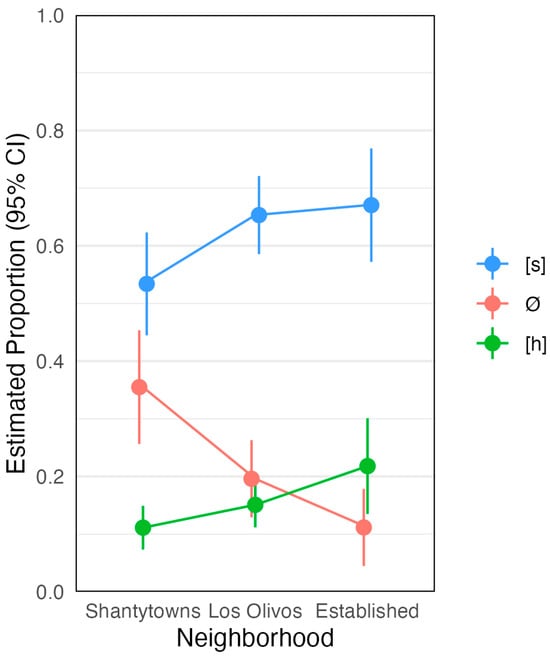

Pairwise comparisons were conducted to assess whether the differences between each category were statistically significant. Focusing first on neighborhood distinctions, the results presented in Table 9 reveal significant differences between shantytowns and more established neighborhoods inhabited by working-class and lower-middle-class classic Limeños. Notably, no significant differences were found between established neighborhoods and Los Olivos. Although Los Olivos is predominantly inhabited by migrants and their descendants, it is recognized as a predominantly lower-middle-class suburb undergoing increasing economic and social integration into the broader urban landscape of Lima. This growing integration may help explain the linguistic convergence observed, as residents of Los Olivos begin to adopt speech patterns more closely aligned with those of established Limeño neighborhoods. While some differences exist between shantytowns and Los Olivos, they do not reach statistical significance at the 0.05 level.

Table 9.

Pairwise comparisons (significant at the 0.05 level) for neighborhoods.

Figure 5 illustrates a clear trend in the estimated proportion of elision and aspiration across neighborhoods. The proportion of elision declines between shantytowns and Los Olivos and decreases further in the more established neighborhoods. In contrast, aspiration is relatively infrequent in the shantytowns but shows a modest increase in Los Olivos and a more pronounced rise in the established neighborhoods. This pattern suggests that residents of more established neighborhoods—and to a lesser extent, those in Los Olivos—are more likely to use aspiration or retain the sibilant rather than elide it. This linguistic behavior aligns with middle-class prestige norms, as previously noted.

Figure 5.

Estimated proportion of [s], [h], and elision across neighborhood.

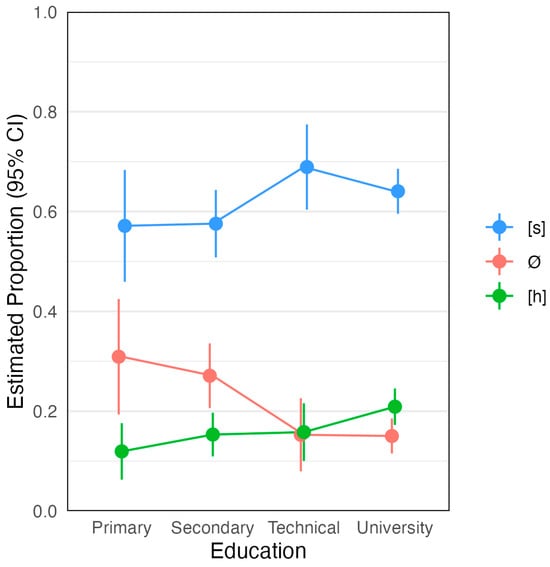

Turning now to education level, Table 10 shows significant differences between those with primary or secondary education and those with university education. There were no other significant differences across education levels.

Table 10.

Pairwise comparisons (significant at the 0.05 level) for education.

Figure 6 illustrates that as educational level increases, the likelihood of aspiration rises, while the likelihood of elision declines. There is also a slight increase in the retention of the sibilant. Individuals with more formal education are significantly more likely to use aspiration and maintain the sibilant rather than elide it. This pattern suggests that university levels of education, in particular, are associated with linguistic practices aligned with middle-class prestige norms.

Figure 6.

Estimated proportion of [s], [h], and elision across educational levels.

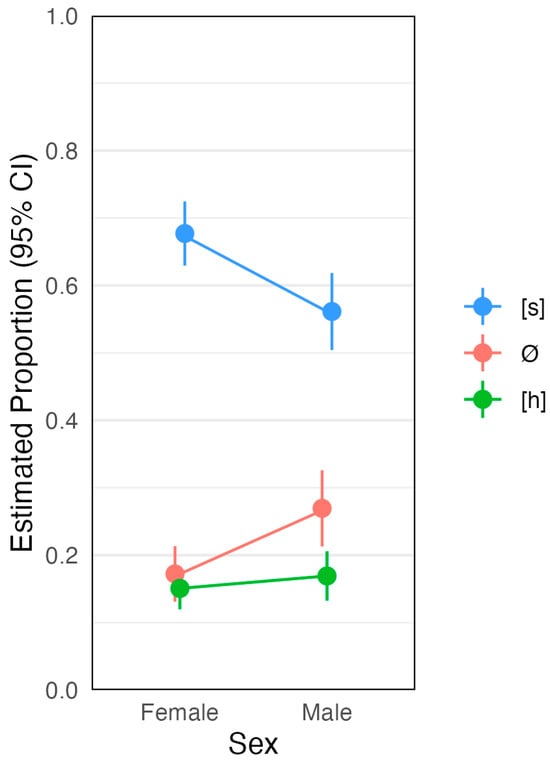

In addition to the influence of neighborhood and educational attainment, biological sex also emerges as a significant social factor in conditioning /s/ variation. As shown in Table 11, there are statistically significant differences in the pronunciation of /s/ according to sex, with female speakers more likely to retain the sibilant and less likely to elide, compared to their male counterparts.

Table 11.

Pairwise comparisons (significant at the 0.05 level) for biological sex.

Interestingly, females only slightly favor aspiration over elision as shown in Figure 7. This would seem to suggest that [s] continues to index prestige in Lima and, as Caravedo (1990) indicated, elision is stigmatized.

Figure 7.

Estimated proportion of [s], [h], and elision across biological sex.

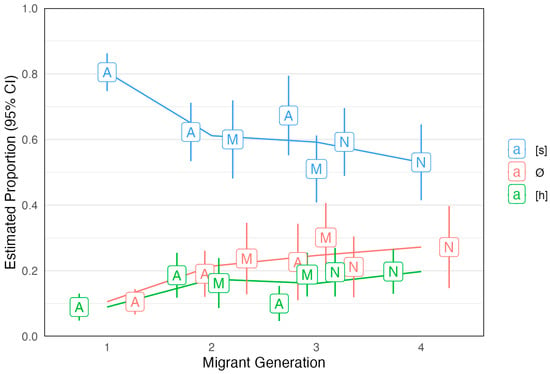

As noted above, the combined variable of migrant generation and family origin has a less pronounced effect on /s/ variation in Lima than neighborhood, education, and biological sex. Nonetheless, it still plays a role in conditioning /s/ variation. As shown in Table 12, there are significant differences between first-generation Andean migrants (1A) and all other generations, with one exception. There are no significant differences between the first-generation Andean participants (1A) and the third generation, whose grandparents were born in the Andean region (3A). The similarity in /s/ variation between first-generation and third-generation Andean-descended speakers suggests that identity—particularly ethnic and regional affiliation—can play a significant role in shaping and maintaining linguistic patterns across generations, even in the face of broader sociolinguistic pressures to assimilate. Nonetheless, there are no significant differences between any other groups, regardless of generation or family origin.

Table 12.

Pairwise comparisons (significant at the 0.05 level) for migrant generation and origin 1.

As shown in Figure 8, all groups have lower odds of using a sibilant relative to elision when compared to first-generation Andean migrants. Overall, speakers from later generations—as well as classic Limeños—exhibit a significantly different pattern of /s/ variation than those from the first generation. This suggests that second- and third-generation speakers tend to align more closely with Limeño norms of /s/ pronunciation. The absence of statistically significant differences between classic Limeños (4N) and all second- and third-generation groups, regardless of family origin, reinforces the idea that linguistic accommodation occurs across generations.

Figure 8.

Estimated proportion of [s], [h], and elision across migrant generations and family origin. The letters refer to Origin (A = Andean, M = Mixed, N = NonAndean).

In summary, the multinomial regression analysis demonstrates that all four social factors—neighborhood, education, biological sex, and migrant generation/ family origin—significantly influence the realization of coda /s/ in Lima. Among these, neighborhood, education, and biological sex emerge as the strongest predictors of variation. Speakers from established neighborhoods and those with university education are more likely to produce aspiration [h] and retain the sibilant [s], aligning with middle-class prestige norms identified by Caravedo (1990). Female speakers also favor [s] over elision, while males tend to elide more frequently, as has been found in previous studies of other Spanish varieties (Cedergren, 1978; Lafford, 1986; Samper, 1990; among others). Although migrant origin plays a less prominent role, it still contributes to variation. Third-generation speakers with Andean ancestry show patterns similar to first-generation migrants, suggesting that ethnolinguistic identity can persist across generations. In contrast, second-generation speakers with Andean ancestry and speakers from mixed backgrounds across generations increasingly adopt Limeño norms, through reduced use of [s] and higher use of elision, and, to a lesser degree, aspiration. This shift indicates a process of linguistic accommodation in the children and grandchildren of migrants, which is reinforced by factors such as neighborhood and/or access to university education. These findings collectively highlight how linguistic variation in Lima is shaped by intersecting social factors with neighborhood, educational level, biological sex, and migrant generation and family origin playing key roles in conditioning the realization of coda /s/.

4.2. Linguistic Factors

In addition to social factors, we examined linguistic factors across the four migrant generations. Although migrant generation is not the strongest social predictor of coda /s/ realization in Lima, comparing linguistic constraints across first-, second-, and third-generation migrants alongside classic Limeños is essential for tracing the dynamics of change in progress. By examining how linguistic factors condition variant choice within each generational cohort, we can assess whether these distinct distributions are associated with stable constraint hierarchies or with shifts across generations. We focused on four primary linguistic factors that have been shown to be significant conditioning factors for /s/ in word final position in previous studies: (1) the preceding segment (high vowel, non-high vowel, non-coronal consonant or coronal consonant); (2) the following segment (i.e., voiceless consonant, voiced consonant, vowel or pause); (3) syllable stress (stressed vs. unstressed); and (4) word length (monosyllabic vs. polysyllabic). In the final model, only the following factors were included as they provided the best fit: (1) the preceding segment (high vowel or non-high vowel); (2) the following segment (i.e., voiceless consonant, voiced consonant, vowel or pause); and (3) syllable stress (stressed vs. unstressed). As noted earlier, the two logistic models, one of the sibilant vs. the weakened variants and the other comparing aspiration and elision, demonstrated the best fit and for that reason, we will report solely on those two models in the results. Below we present the results of the logistic regressions, the first examining the factors that condition the choice of sibilant vs. weakening (i.e., [h] and Ø), and a second focusing on the linguistic factors that condition aspiration vs. elision. In this section, we analyze /s/ only in word final position.

4.2.1. Multivariable Logistic Models with Linguistic Variables Only

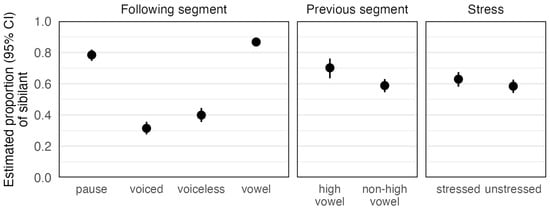

[s] vs. Weakening

Table 13 shows the results of the mixed effects multivariable logistic regression of [s] vs. weakening, which reveals that the following factors significantly condition /s/ weakening: the following segment, the type of previous vowel (i.e., high vs. non-high), and syllable stress. The regression estimates indicate that [s] is significantly more likely to be retained when followed by a vowel or a pause, and less likely to be retained when followed by consonants, particularly voiced consonants, which exert the strongest weakening effect. Additionally, when /s/ is preceded by a non-high vowel, it is more prone to weakening. Stress also plays a role: /s/ is less likely to be realized as a sibilant in unstressed syllables, reflecting a general tendency toward reduction in prosodically weaker positions. Among the linguistic constraints examined, the following segment exerts the greatest influence on /s/ realization, followed by stress, and then the preceding vowel.

Table 13.

Mixed effects logistic regression: linguistic factors for [s] vs. weakening.

The pairwise Tukey comparisons shown in Table 14 revealed a clear effect of the following segment on /s/ realization. As seen in Table 14 and in Figure 9, pause and vowel contexts strongly favor [s] retention, whereas consonantal contexts, particularly voiced consonants, promote weakening. The odds of [s] realization are nearly eight times higher before a pause than before a voiced consonant and more than five times higher than before a voiceless consonant. Moreover, [s] is significantly more likely to be realized before vowels than in any other context, most likely reflecting the well-known tendency for resyllabification in intervocalic environments. In contrast, both voiced and voiceless consonants strongly favor aspiration or deletion. All differences are statistically significant (p < 0.0001), underscoring the robust role of following phonetic environment as a conditioning factor in Spanish coda /s/ variation.

Table 14.

Pairwise results of Tukey comparisons (significant at the 0.05 level) for following segment.

Figure 9.

Estimated proportion of [s] vs. weakening in linguistic contexts.

The preceding segment also conditioned the production of /s/. When preceded by a high vowel rather than a non-high vowel, the odds of [s] were 1.65 higher, as shown in Table 14 and in Figure 9.

Syllable stress was also a significant factor in conditioning /s/. The pairwise Tukey comparisons in Table 14 and in Figure 9 revealed significant differences between stressed and unstressed syllables; the odds of producing [s] were 1.21 times higher in stressed than in unstressed syllables.

To summarize this subsection, the results of the logistic regression showed that a number of linguistic factors condition the probability of the sibilant occurring in contrast to weakening (i.e., aspiration or deletion). The occurrence of the sibilant is more likely when the following segment is a pause or a vowel and is less likely when the following segment is a voiced or an unvoiced consonant. The preceding segment also conditions the occurrence of the sibilant, which is more likely to occur when the preceding segment is a high rather than a non-high vowel. Finally, when /s/ occurs in a stressed syllable, the sibilant is more likely to occur than when /s/ is in an unstressed syllable. These results coincide with those of the previous research (E. K. Brown, 2009b; E. L. Brown & Torres Cacoullos, 2002, 2003; Caravedo, 1990; Cepeda, 1995; Cid-Hazard, 2003; File-Muriel & Brown, 2011; Fox, 2006; Guitart, 1983; Hoffman, 2001; Lipski, 1995; Mason, 1994; among others).

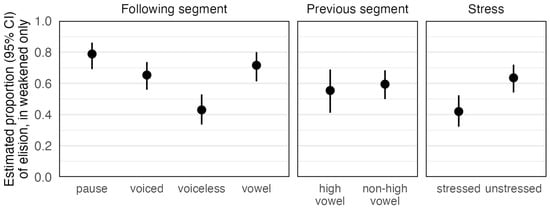

Aspiration vs. Deletion

To determine whether the factors that condition aspiration and deletion were the same as those that conditioned the sibilant vs. weakening, we carried out a second logistic regression focusing on /s/ in word final position. The results of the logistic regression in Table 15 show that two factors—the following segment and syllable stress—condition aspiration and deletion. In contrast, the previous segment did not have a significant effect.

Table 15.

Mixed effects logistic regression: linguistic factors for aspiration vs. deletion.

We conducted pairwise Tukey comparisons of each of the variables. As shown in Table 16 and Figure 10, the following segment significantly conditions the likelihood of deletion versus aspiration. Deletion is more likely than aspiration before pauses and consonants, especially voiceless consonants. The odds of deletion relative to aspiration are nearly twice as high before a pause than before a voiced consonant and almost five times higher before a pause than before a voiceless consonant. In contrast, the difference between pause and vowel contexts is not statistically significant, suggesting that aspiration and deletion occur at comparable rates in these environments. Voiced consonants significantly favor deletion compared to voiceless consonants, but not compared to vowels (p = 0.22). Finally, deletion is much less likely before voiceless consonants than before vowels, confirming that voiceless consonants strongly favor aspiration. Taken together, these results indicate that pause, vowel, and voiced consonant contexts promote deletion, whereas voiceless consonants strongly favor aspiration.

Table 16.

Pairwise results of Tukey comparisons (significant at the 0.05 level) for following segment.

Figure 10.

Estimated proportion of elision vs. aspiration in linguistic contexts.

As shown in Table 16 and Figure 10, whether the preceding segment was a high or non-high vowel had no significant effect on elision vs. aspiration. In contrast, syllable stress significantly conditioned the choice between aspiration and deletion; the odds of elision were 0.41 higher in unstressed than in stressed syllables.

To summarize the analysis of aspiration vs. deletion, a mixed effects logistic regression revealed that both following segment and syllable stress conditioned aspiration vs. deletion. Pairwise Tukey comparisons demonstrated that pauses favored deletion over aspiration when compared to other following segments. Deletion of /s/ was also more probable when the following segment was a voiced consonant rather than a voiceless consonant, while aspiration was more likely when the following segment was a voiceless consonant rather than a pause, a voiced consonant or a vowel. In addition, aspiration was more likely to occur in stressed than in unstressed syllables.

In the next section, we will compare the factors that condition variation across the four migrant generations to determine whether their choice of allophone is influenced by the same linguistic constraints.

4.2.2. Multivariable Logistic Models with Linguistic Variables, Migrant Generation, and Interactions

To determine whether the linguistic factors that condition variation were similar across all four migrant generations, a mixed effects multivariable logistic regression model that included migrant generation and the linguistic variables was run for [s] vs. weakening and another for aspiration vs. elision.

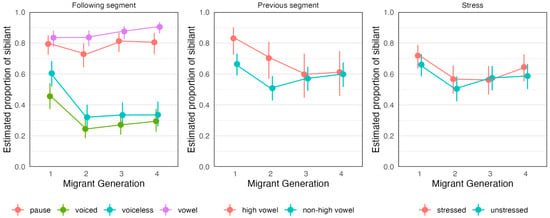

[s] vs. Weakening

The analysis of [s] vs. weakening across the four migrant generations is shown in Table 17. The analysis includes Migrant Generation (four groups) and three linguistic factors—following segment, previous segment, and stress—as well as their interactions with generation. The results reveal that all main effects are statistically significant. The following segment stands out as by far the most powerful predictor (χ2 = 1594.89, p < 0.0001). The previous segment (χ2 = 12.03, p = 0.0005) and stress (χ2 = 7.62, p = 0.0058) also significantly affect variation, though to a much lesser degree. Migrant group (χ2 = 9.01, p = 0.029) is a significant factor, indicating differences in /s/ realization patterns across the four generational groups analyzed. Moreover, there are significant interactions between migrant group and following segment (χ2 = 96.19, p < 0.0001) and between migrant group and previous segment (χ2 = 8.09, p = 0.044). This suggests that the effect of phonetic environment is not uniform across social groups—in different migrant generations, linguistic constraints condition /s/ variation in distinct ways, possibly reflecting the effect of dialect contact and language change. In contrast, the interaction between stress and migrant group is not significant (χ2 = 4.17, p = 0.24), which—together with the similar estimates as shown in Figure 11—indicates that the effect of stress is stable across groups.

Table 17.

Mixed effects logistic regression: linguistic factors for [s] vs. weakening.

Figure 11.

Migrant Generation x Following Segment, Previous Segment and Stress in word final position: comparison of productions of weakening (n) vs. the sibilant (s).

As illustrated in Figure 11, the conditioning effect of the following segment on the realization of [s] versus its weakening shows greater similarity among second- and third-generation speakers and classic Limeños. In contrast, first-generation migrants exhibit a distinct pattern, particularly when /s/ is followed by a voiced or voiceless consonant. In these contexts, first-generation speakers produce the sibilant at a significantly higher frequency than the other three groups. However, when /s/ precedes a vowel or a pause, all four groups demonstrate a more aligned preference for the sibilant. Additionally, differences emerge when the preceding segment is a high vowel: both first- and second-generation speakers tend to favor the sibilant, whereas third-generation speakers and classic Limeños are more likely to weaken /s/. As previously noted, the influence of syllable stress remains consistent across all four groups.

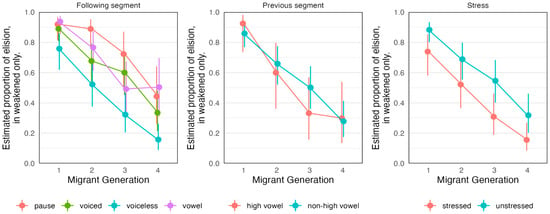

Elision vs. Aspiration

Table 18 reveals the results of likelihood ratio tests from a mixed-effects logistic regression model predicting elision versus aspiration. Once again, the analysis includes migrant generation (four groups) and three linguistic factors—following segment, previous segment, and stress—as well as their interactions with generation. The results indicate that migrant generation is highly significant (χ2 = 29.81, df = 3, p < 0.0001), reflecting clear intergenerational differences in the distribution of deletion and aspiration. As Figure 12 shows, earlier generations—particularly first-generation Andean migrants—favor deletion more strongly, while later generations show increasing rates of aspiration. Among the linguistic factors, following segment exerts the strongest effect (χ2 = 150.69, df = 3, p < 0.0001). Deletion is most likely before a pause and least likely before voiceless consonants, with vowels and voiced consonants occupying intermediate positions. Stress is also highly significant (χ2 = 70.00, df = 1, p < 0.0001): unstressed syllables show a greater propensity for deletion than stressed ones. By contrast, previous segment does not reach significance (χ2 = 0.02, df = 1, p = 0.88), suggesting that vowel height in the preceding context plays a relatively minor role once other factors are controlled. The interaction between migrant generation and following segment approaches significance (χ2 = 16.15, df = 9, p = 0.064), indicating some evidence of generational differences in the conditioning effect of the following segment. In contrast, the migrant generation by previous segment and migrant generation by stress interactions are not significant, which together with the visual evidence in Figure 12, indicates that the effects of these factors remain stable across generations.

Table 18.

Mixed effects logistic regression: linguistic factors for elision vs. aspiration.

Figure 12.

Migrant Generation by Following Segment in word final position: comparison of productions of elision (Ø) vs. aspiration (h).

Figure 12 provides a more detailed view of these effects by showing the proportion of deletion among weakened tokens across the four migrant generations, disaggregated by following segment, previous segment, and stress. Across all three panels, the most striking pattern is a steady intergenerational decline in deletion rates, consistent with the highly significant main effect of generation. Generation 1 (Andean migrants) shows uniformly high deletion rates across contexts, whereas deletion becomes progressively less frequent in Generations 2 and 3, and reaches its lowest levels among Generation 4 speakers (classic Limeños). Deletion is strongly favored before pauses and least favored before voiceless consonants, and this hierarchy remains stable across groups. However, the steepest generational declines occur in contexts with voiceless following segments. The previous segment panel shows parallel declines across high and non-high vowel contexts, consistent with the nonsignificant main and interaction effects. Both contexts follow similar trajectories, indicating that preceding vowel height does not play a meaningful role in the ongoing change. Finally, the stress panel reveals consistently higher deletion rates in unstressed syllables than in stressed ones for all generations. Although both contexts exhibit clear declines in deletion and increases in aspiration across generations, the relative difference between them remains stable, in line with the nonsignificant interaction in the model.

In sum, the analyses of both [s] vs. weakening and elision vs. aspiration provide a clear picture of how patterns of /s/ realization evolve across migrant generations in Lima. For [s] vs. weakening, the results demonstrate that linguistic factors—particularly following segment—play a dominant role, while previous segment and stress exert smaller but still significant effects. Migrant generation also emerges as a significant factor, and the interactions with following and previous segment indicate that the influence of phonetic environment varies somewhat across social groups. First-generation Andean migrants display a distinct profile, producing [s] at notably higher rates before voiced and voiceless consonants than later generations and classic Limeños, who show more homogeneous patterns. These generational differences likely reflect the impact of dialect contact: migrants bring Andean Spanish patterns to Lima, while their descendants increasingly align with urban norms. At the same time, the stable effect of stress across groups points to constraint stability despite social change.

The analysis of elision vs. aspiration confirms and extends this picture. Migrant generation is again highly significant, revealing a steady intergenerational shift from deletion toward aspiration. This change is most pronounced in contexts with voiceless following consonants, while overall linguistic constraints—favoring deletion before pauses and in unstressed syllables—remain stable. Preceding vowel height has little impact on this change. These results point to structured variation in which linguistic constraints are stable, but rates shift across generations.

Taken together, the findings illustrate a process of sociolinguistic change driven by migration and dialect contact, in which successive generations move away from Andean Spanish patterns toward urban Limeño norms. First-generation migrants maintain higher levels of sibilant production and deletion, whereas later generations increasingly adopt aspiration as the dominant weakening variant. Throughout this change, the relative strength of linguistic constraints remains relatively constant, indicating that language change proceeds through shifting frequencies rather than through a reorganization of the constraint hierarchy.

5. Discussion

The phenomenon of /s/ weakening is linked to the long-term history of linguistic change in the phonological distinctions among sibilants in Spanish, a gradual process that has developed differently across diverse Spanish-speaking communities. In the present analysis, gradual linguistic change is evident in apparent time, seen in differences across migrant generations. However, linguistic change in Lima involves not only the temporal dimension but also the spatial one, occurring through the interaction of both dimensions. This requires a reevaluation of the traditional approach to linguistic variation in Peru, which assumes that space is a fixed entity. Instead, we have adopted a dynamic view of space, as developed in humanistic geography, where speaker mobility through large-scale migration has brought together varieties of Spanish that were previously separated. This dynamic view of space facilitates the understanding of linguistic diversity and language change by taking into account the significant influence of population movements, which have resulted in contact between different varieties of Spanish and given rise to a variety of linguistic changes. This concept is central to the Project Language Change as a Result of Andean Migration to Lima, Peru, which has found that migration of Andean settlers to the capital is a significant driver of sociolinguistic change, as demonstrated in studies of other linguistic phenomena (Caravedo & Klee, 2012; Klee & Caravedo, 2005, 2006, 2020; Klee et al., 2011, 2021).

In regard to the behavior of the sibilant in Lima, the results support several interpretative hypotheses. Firstly, the influence of internal linguistic factors, such as the previous and following segment and syllable stress, which has remained constant in the evolution of sibilants in many Spanish-speaking areas, is confirmed. Secondly, social factors, such as biological sex, neighborhood, and educational level, along with different migratory generations, shape linguistic change in unique ways compared to other Spanish-speaking communities.

For example, different variants of /s/ have gained particular social significance in Lima, where in the second half of the twentieth and first part of the twentieth centuries there has been constant contact between classic Limeño speakers and those who speak Andean Spanish. In Lima, where Andean migrants have faced widespread discrimination, the contact between Andean and Limeño varieties has been conflictive. In previous analyses of the perception of linguistic variants in Lima (Caravedo, 2014), it has been noted that Andean Spanish speakers have assigned an indexical meaning to the aspiration found in classic Limeño speech. Conversely, the preservation of [s] in syllabic coda identifies Andean speakers from the perspective of classic Limeños, thus also having an indexical value. In our study, first-generation Andean speakers in Lima produced the sibilant in word final position in significantly higher proportions than the second, third and fourth generations when the following segment was a voiced or an unvoiced consonant. Because Andean culture and speech have traditionally indexed rurality, poverty, and backwardness in Lima, a high proportion of word final [s] is perceived negatively by classic Limeños (Caravedo, 2014). In addition, the Andean /s/ is perceived as different from the Limeño /s/ from an articulatory standpoint. The former is characterized in the literature (Escobar, 1978) as apico-alveolar with a high degree of stridency and is reinforced in coda position, while the latter is dental and shorter than the Andean [s]. These differences are apparent in the spectrograms below of sibilants in final prepausal position of a first-generation Andean migrant (Figure 13) and a classic Limeño speaker (Figure 14). The spectrograms reveal the longer duration and intensity of word final [s] in Andean Spanish in contrast to the [s] produced by the classic Limeño, which has resulted in classic Limeños perceiving greater phonetic intensity as characteristic of the Andean variety.

Figure 13.

Example of word final [s] before a pause of a first generation Andean migrant.

Figure 14.

Example of word final [s] before a pause of a classic Limeño.

Regarding the aspirated Limeño variant, Andean speakers consider it deviant, despite recognizing it as typical of Lima (Caravedo, 2014). While the articulation of the sibilant is weaker in Lima, at the same time, Limeño aspiration does not constitute articulatory weakening, as the aspirated variant tends to be reinforced, approaching the velar fricative phoneme /x/, especially before velar consonants, such as [’axko] [’kuxko], which can be interpreted as assimilation to the place of articulation of the following consonant. Interestingly, this variant, common among upper-middle class Limeños, is not considered prestigious among Andeans (Caravedo, 2014) and does not seem to serve as a model for imitation for most first-generation Andean migrants, although to confirm this hypothesis a perception test is needed.

When first-generation Andean migrants weaken /s/, they overwhelmingly favor elision, with aspiration playing only a marginal role. The second generation continues to elide frequently but begins to show a modest increase in aspiration as well as a decrease in the sibilant. Third-generation speakers further advance this shift, increasing their use of aspiration and reducing elision, which signals an emerging alignment with urban Limeño patterns. Nonetheless, some second- and third-generation speakers with strong ethnolinguistic ties to the Andes continue to follow the norms of earlier generations, reflecting the persistence of Andean linguistic features within certain segments of the community. Overall, while both the second- and third-generations produce the sibilant at rates comparable to classic Limeños, they still aspirate less and elide more, particularly in specific phonetic contexts. These findings indicate a gradual but incomplete convergence toward Limeño norms across generations. Understanding this divergence more fully will require further research on how different sectors of Limeño society perceive and evaluate /s/ variants and how these social meanings influence the trajectory of linguistic change.

Regarding the first-generation speakers and the speakers from the two subsequent generations with more social ties to G1 speakers, the lower rates of [h] and [x], as well as the lack of prestige for [x] in Andean Spanish (Caravedo, 2014) could be due, in part, to the structure of Quechuan phonology. With respect to the overall lower rates of [h], various Quechua varieties such as Cuzco Quechua, Bolivian Quechua, and Ayacucho Quechua, do have /h/ as a phoneme but, not as an allophone of /s/ and with very different phonotactic constraints from Spanish [h]. While in Spanish, [h] occurs as an allophone of /s/ in syllable-final and word-final positions, as well as word-initial position in some varieties, in Quechua, /h/ is almost strictly limited to syllable-initial position, especially in Ayacucho Quechua (Parker, 1971, SAPhon Database). Thus, while /h/ and [h] exist in both Quechua and Andean Spanish, their phonotactic distributive differences in either language would potentially impede this process in Andean Spanish. Similar proposals for the lower levels of intervocalic spirantization of /d/ in Cuzco Spanish have been made by Eager (2018) and Rogers et al. (in press), namely, the lack of voiced obstruents in Quechua, has slowed the process of intervocalic lenition of /d/ in bilinguals, and subsequently been passed down as a feature of monolingual Spanish in the region through language shift. Similar phenomena have been documented in Yucatan Spanish due to contact with Yucatec Maya (Michnowicz, 2009). A similar process may be occurring in the present dataset, in that speakers prefer [s] and elision to [h] in syllable-final position due to the passing down of this feature from Quechua-Spanish bilinguals to Spanish monolinguals, and subsequently to G2 and G3 speakers with more ties to G1 speakers. In other words, the shift of [h] from strictly syllable-initial contexts to syllable-final contexts may present a larger phonotactic and typological gap for bilinguals than other features, thus resulting in a lower frequency of [h] in syllable-final position in Andean Spanish.

Likewise, in the case of [x] preceding velar consonants, Quechua completely lacks phonemic velar fricatives. Taken in tandem with the phonotactical differences in /h/ and [h] in Quechua and Spanish, it is possible that [x] in syllable final position is even less common due to a potentially even larger phonotactic and typological gap between languages given that [x] is entirely absent from Quechuan segmental phonology. Notably, the appearance of G1 tendencies in some G2 and G3 speakers with more ties to G1, creates the interesting possibility that these tendencies could be identity markers to speakers, similar to [l] in Chicano English (Van Hofwegen, 2009) and Miami Cuban English (Rogers & Alvord, 2019), as well as vowels in Chilean Spanish (Sadowsky, 2012). The possibilities of Quechua influence as well as lower levels of aspiration being an identity marker of the G1 linguistic community are intriguing and merit further study. Initial steps would be to compare /x/ in Andean Spanish to /x/ in Limeño Spanish to tease out any acoustic differences that could be attributed to contact with Quechua, as well as gathering perceptual data.

While these linguistic tendencies shed light on micro-level processes of contact and identity construction, understanding their distribution and social meaning requires situating them within the macro-level dynamics of Limeño society. The social factors influencing the Limeño sibilant extend beyond biological sex, socioeconomic strata, or differences in educational levels. They also include spatial mobility and the resulting social restructuring within the city. Therefore, objective quantitative results should be interpreted in light of the unique characteristics of a society like Peru’s. Future research using ethnographic methodology is needed to confirm our impressions of the social significance of these variants and to shed light on how they continue to evolve within this social restructuring.

6. Conclusions

Our analyses of /s/ variation in the demographic context of the city of Lima have shown the results of dialect contact between classic Limeño Spanish and Andean Spanish following a period of major demographic change. In spite of the presence in Lima of large numbers of speakers of Andean Spanish, a variety of Spanish in which the sibilant is maintained, /s/ weakening has seemingly expanded in the city since the 1980s when comparing our results with those of Caravedo (1990). First-generation Andean migrants maintain high levels of the sibilant in syllable-final position. In contrast, their descendants (i.e., second- and third-generation migrants in the city) display lower proportions of sibilant maintenance, to the point that they approach the values of classic Limeños, suggesting an accommodation to the perceived patterns of the city.

When /s/ weakening occurs in the speech of first-generation Andean migrants, elision is favored over aspiration, unlike the working-class classic Limeños in our study, who more frequently use aspiration. This preference for elision may reflect the influence of Quechua on the migrants’ speech patterns. We hypothesize that both aspiration and elision have taken on distinct social meanings in Lima and that aspiration is not considered prestigious among Andean Spanish speakers. However, the social perceptions of aspiration and elision seem to change by the third generation as speakers produce lower levels of elision and higher rates of aspiration, approaching but not aligning completely with the speech of classic Limeños. Elision is a phenomenon linked primarily to males and social groups with lower educational attainment in poorer neighborhoods of the city. It is noteworthy that in Los Olivos, a neighborhood of socially ascending migrants, the rate of elision decreases compared to traditional migrant neighborhoods.

In regard to linguistic factors, our results are similar to those in most previous studies. The sibilant was produced at higher frequencies in a stressed syllable and when followed by a vowel or a pause in contrast to a voiced or voiceless consonant. It also occurred more frequently when the preceding vowel was high rather than non-high. Elision occurred more frequently than aspiration in unstressed syllables and when followed by a pause, a vowel, or a voiced consonant.

The results presented here confirm the predominance of the sibilant in Lima over a period that spans from the late 20th to the early 21st century and show change across migrant generations. Further studies with more recent corpora comprising the third and fourth generations of migration, the new Limeños, are necessary to confirm or nuance the evolutionary trends of one of the most variable phonemes in Spanish in a historically conservative city.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization of the research on dialect contact in Lima, C.A.K. and R.C.; Methodology, C.A.K., R.C. and B.M.A.R.; Statistical Analysis, A.R., K.T.T. and L.D.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.A.K., R.C. and B.M.A.R.; Writing—Review and Editing, C.A.K., R.C., B.M.A.R., A.R., L.D. and K.T.T.; Funding Acquisition, C.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Minnesota Grant-in-aid of Research [(Proposals #17888, #2038)] and a University of Minnesota Imagine Fund Award awarded to C.A.K.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Minnesota (protocol code 9812S00120, date of approval 27 January1999 and protocol code 1207E17105, date of approval 20 July 2012).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is not publicly available due to lack of permission to share.

Acknowledgments