Abstract

The rapid growth of air traffic demand and limited airspace resources have made efficient coordination in multi-airport systems a critical challenge. This paper develops a bi-level air–ground collaborative scheduling model for the Beijing-Tianjin-Airport cluster, integrating terminal-area departure sequencing (upper level) with airport surface taxi and pushback scheduling (lower level), where the upper-level model minimizes departure delays, maximizes airport satisfaction, and reduces fairness deviation, while the lower-level model optimizes taxi routing and pushback timing. To solve the model, NSGA-II is applied to the upper-level sequencing problem and a Genetic-Simulated Annealing algorithm is used for surface scheduling. Empirical evaluation using operational data from Beijing Capital, Beijing Daxing, and Tianjin Binhai airports shows that the proposed approach reduces total departure delay by 49.4%, lowers average taxi time by up to 40.4%, and improves overall airport satisfaction by 5.2%, while reducing fairness deviation by 52.6%. These results demonstrate that the framework effectively enhances efficiency and equity in multi-airport departure operations.

1. Introduction

Following a rapid post-pandemic recovery, China’s civil aviation flight volume had surpassed its 2019 level by 3.67% by 2024, with demand concentrated in metropolitan multi-airport systems (MAS). The Beijing-Tianjin-Airport (BTA) cluster, encompassing Beijing Capital (ZBAA), Beijing Daxing (ZBAD), and Tianjin Binhai (ZBTJ), is a key national strategic project, handling 15.98% of the nation’s flight volume [1]. However, their proximity and overlapping airspace create complexity: departure routes intersect at shared terminal fixes, leading to downstream congestion and inter-airport interference [2,3]. Current practice involves each airport optimizing departures in isolation, resulting in fragmented operations and reduced overall efficiency.

This “metroplex” problem of competing departures for shared airspace has been observed in other multi-airport regions (e.g., New York, London) and is now emerging in BTA [4]. This dynamic undermines punctuality, regional throughput, and fairness. Therefore, addressing it is essential. Smoothing departure flows and reducing inter-airport conflicts can raise on-time performance and ensure that no single airport monopolizes departure slots. Accordingly, this paper focuses on the departure side of multi-airport terminal operations. We intentionally exclude arrival sequencing because arrivals are governed by strict ATC safety procedures, and coordinating arrivals across airports (e.g., merging inbound streams) adds significant complexity and increases controller workload [5]. By focusing on departures, we posit that substantial efficiency gains are achievable through improved surface and takeoff scheduling without interfering with critical arrival management [6]. Our working hypothesis is that an integrated departure strategy covering gate pushback, taxi-out, runway queuing, and airborne slot allocation will yield significant improvements in both efficiency and equity. We further assume that small, coordinated adjustments to each airport’s departure sequence can reduce overall system delay while maintaining safety. Additionally, aligning the planned takeoff times with actual taxi-out trajectories can prevent unnecessary holding at gates and on taxiways.

In light of the above, we propose a bi-level optimization model for integrated departure scheduling in BTA. The model comprises an upper level and a lower level with distinct but linked functions. The upper-level model optimizes the coordinated departure sequence (takeoff scheduling) across multiple airports. Its goal is to allocate target takeoff times (TTOTs) for each flight in a way that balances efficiency and fairness between airports, with explicit fairness criteria to prevent any single airport from experiencing disproportionate delay. The lower-level model then performs detailed airport-surface optimization at each airport. Given the upper-level TTOT assignments, the lower-level model determines each departure flight’s pushback timing, pushback order (holding at the gate if necessary), and a conflict-free taxi route to reach the runway in time for its assigned slot. At the same time, without altering the arrival sequence, the model computes conflict-free taxi routes for arriving flights from the runway to the gate, ensuring that surface movements for arrivals and departures do not conflict. Although arrival sequences are treated as fixed inputs, arrival–departure interactions are still captured through mixed-mode runway separations and runway-occupancy constraints in the upper-level model. By splitting the problem, the bi-level framework mirrors actual ATM decision layers: a strategic slot allocation at the upper level and a tactical surface management problem at the lower level. A key objective is to ensure consistency between the two levels, i.e., that the lower-level surface schedules comply with the upper-level TTOT assignments. In this study, the two levels are coupled in an offline sequential manner: the upper level assigns TTOTs and the lower level seeks a feasible surface plan consistent with these TTOTs. A real-time feedback loop (e.g., rolling-horizon re-optimization when disturbances occur) is left for future work.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- Metroplex-wide coordination at shared terminal fixes: We formulate a multi-airport departure sequencing model that explicitly enforces separation constraints at shared handover points (e.g., ELKUR/PEGSO), enabling system-wide coordination across three airports.

- End-to-end linkage from TTOT to surface realizability: We couple TTOT assignment with airport-surface pushback and taxi planning, ensuring that strategic takeoff slots are operationally realizable under surface conflict constraints.

- Airport-level equity as an explicit optimization objective: We embed an airport-level satisfaction and fairness-deviation objective to quantify and control inter-airport equity–efficiency trade-offs in metroplex departure management.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly reviews the related work. Section 3 presents the materials and methods, including the problem statement, bi-level optimization model formulation (upper-level multi-airport departure sequencing and lower-level surface scheduling), and the corresponding solution algorithms (Yen’s algorithm for taxi route generation, NSGA-II for upper-level optimization, and a Genetic-Simulated Annealing hybrid for lower-level optimization). Section 4 details the empirical evaluation of the Beijing-Tianjin-Airport (BTA) cluster case, encompassing operational characteristics, taxi route set establishment, computational processes, and in-depth analysis of key results (including departure delay, airport satisfaction, handover point resource allocation, and surface taxiing performance). Section 5 concludes the paper with core findings, practical implications, and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Multi-Airport Flight Scheduling

In congested metroplexes, flights at different airports are interdependent via shared fixes and airspace constraints; therefore, uncoordinated scheduling can cause “cascading delays” across airports.

Recent work has begun to model and optimize MAS departure scheduling. Li et al. [7] propose a multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) framework. In this approach, departure times across all airports are first optimized jointly to minimize overall delay and taxi queue congestion. Next, optimal departure routes (SIDs) are assigned to each flight. This two-step MARL (using algorithms like multi-agent DDPG) learns cooperative policies that reduce multi-airport delay. Jiang et al. [8] formulate a bi-level collaborative model: the upper level sets arrival sequences (to incorporate arrival–departure interactions) and the lower level schedules departures. In their scheme, efficiency is prioritized during peak demand, whereas in off-peak periods, the lower-level objective maximizes fairness among airport departure routes. Liu et al. [9] introduce a two-stage no-wait hybrid flow-shop model for MAS departure scheduling: aircraft are processed through parallel “machines” (stages) representing runways or taxiways, with no waiting between stages allowed. They use simulated annealing to sequence departures under these constraints. Other authors [10,11] have empirically contrasted different U.S. metroplexes (Atlanta, Los Angeles, New York, etc.), identifying structural differences in traffic flow that affect scheduling flexibility. Sidiropoulos et al. [12] cluster demand patterns in a metroplex (New York), using distributionally robust optimization to identify major flow regimes under uncertainty. These studies reveal that airport demand and routes can shift by time of day or weather, suggesting that MAS schedules must adapt dynamically.

In parallel, several slot-allocation models now incorporate fairness. Zografos and Jiang [13] formulate a bi-objective model balancing total displacement (efficiency) and schedule fairness across airlines. Fairbrother et al. [14] propose a two-stage slot assignment mechanism. In stage one, a ‘fair’ baseline schedule is constructed across all airlines. In stage two, each airline then adjusts its allocated slots among its flights according to its own preferences. Pellegrini et al. [15] develop SOSTA, an integrated MILP that simultaneously allocates slots at all airports in a European network, respecting “minimum” and “maximum” slot regulations. Ribeiro et al. [16] and their colleagues further embed IATA scheduling rules and priorities into multi-airport slot models. Overall, these works find that small sacrifices in pure efficiency (total delay) can greatly improve fairness metrics.

Despite these advances, MAS scheduling research remains mostly strategic (i.e., aggregate slot allocation) and rarely spans all levels of execution. Most models stop at setting TTOTs or slot times, without “end-to-end” linkage to individual pushbacks and taxi routes. Taxi operations are usually simplified (e.g., assumed fixed route/fixed travel time). In short, there is little coordination between airspace-level slotting and airport-level departure fairness or surface flows.

2.2. Taxi Scheduling

A vast literature addresses single-airport taxi scheduling (often under ‘surface management’ or ‘ground movement’ optimization). Many propose mathematical models (MILP, A* search, heuristics) to route taxiing aircraft and allocate taxiways subject to safety constraints. For example, Lee and Balakrishnan [17] review such models: they show that such optimization can reduce fuel burn, but note that most schemes assume fixed target takeoff times set by the runway schedule. In practice, these taxiway plans often use time-window or path-assignment methods to avoid conflicts. For instance, Atkin et al. [18] study multi-objective optimization of taxi routes using “time-window” algorithms to ensure runway access constraints are met. Ravizza et al. [19] and Benlic et al. [20] develop conflict-resolution schemes that adjust taxi clearance sequences when two aircraft on adjacent taxiways would collide, effectively coupling taxi routing with runway scheduling. Others (Baik et al. [21]; Marín [22]; Smeltink et al. [23]; Deau et al. [24]; Eun et al. [25]) have applied network-flow, constraint-programming, or heuristic techniques to sequence taxiing aircraft, often minimizing total taxi time or emissions.

However, many of these taxi models impose simplifying assumptions. They often pre-compute a shortest-path route for each flight (ignoring dynamic congestion) or use loose time discretization. Critically, most taxi scheduling studies have not considered the full multi-airport system context or tactical equity (fair resource allocation among airports). They tend to focus on single airports with simplified taxi-routing assumptions and lack integration with airspace slot allocation constraints.

2.3. Pushback Control

Pushback control strategies regulate when aircraft leave their gates to taxi, acting as a throttle to regulate surface queues. Pioneering work by Burgain, Simaiakis, Balakrishnan and others proposes dynamic pushback metering: Simaiakis et al. [26] field-tested a pushback rate control at Boston Logan. They set a rolling limit on how many planes may push back per minute to avoid exceeding taxiway capacity. In field tests, this strategy significantly reduced total taxi engine-on time. Fuel burn dropped by approximately 12,250–14,500 kg (4000–4700 US gallons) over 4 h peak periods at the cost of only a few extra minutes of gate delay per flight. Similarly, later models (Lian et al. [27]) use Markov-chain or queueing models to set a pushback threshold dynamically: Stage I optimizes a queue-length threshold (minimizing taxi-queue delays vs. gate-hold penalties), and Stage II then schedules individual pushbacks to minimize total delay, fuel and emissions under that threshold.

Gate-holding and “Collaborative Virtual Queue” (CVQ) concepts have also emerged. In these schemes, ready-to-pushback aircraft are held in a queue (physically at gates) and only released when the taxiway can accommodate them. Simaiakis and Balakrishnan [28] demonstrated via simulation that gate-holding can decouple gate pushbacks from runway departures, thereby smoothing departure peaks. Khadilkar and Balakrishnan [29] later formalized the Collaborative Virtual Queue (CVQ) protocol to manage congested ramps more fairly. These methods consistently find that controlling gate queues yields large fuel and emission savings and can scale effectively even under high-demand scenarios. Desai [30] even proposes “penalty-based” pushback controls: they assign costs for delaying each flight and solve an optimization to trade off delays vs. efficiency, thereby improving flexibility.

Pushback control studies often assume a fixed TTOT sequence or a simple runway operation model. While they cut fuel/emissions under congestion, they are typically tested on single runways or terminals—coordination with multi-airport slot schedules remains unexplored. Moreover, they usually assume known taxi times.

2.4. Summary

In every area above, a common gap is the missing end-to-end link from initial slot allocation (TTOT) through pushback and taxi to runway takeoff. Slotting models assume the ground system will conform; taxi models assume takeoff times; and pushback models assume a runway schedule—but no model ties them all together. Likewise, all fairness models are strategic (airline-level at network scale) and do not capture how to enforce equity at individual airports or gates. Finally, many models use simplified paths or ignore uncertainty (e.g., fixed taxi paths, static weather), limiting their realism. These gaps highlight open research needs in truly integrated, fairness-aware MAS departure scheduling. Different from existing bi-level studies that primarily optimize slot times or sequencing at one layer, our framework explicitly enforces separations at shared handover fixes across three airports and couples TTOT assignment with airport-surface realizability while also embedding airport-level equity as an explicit objective.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preliminaries

For each departure flight , SOBT denotes the scheduled off-block time, TTOT denotes the target takeoff time assigned by the upper-level model, and ATOT denotes the realized takeoff time. The runway-entry time refers to the time when the aircraft reaches the runway queue (threshold). A handover point is a terminal-area fix where departure flows from different airports merge into shared routes; separation constraints are enforced at these fixes to prevent downstream conflicts. In current operations, each airport typically applies a first-come-first-served (FCFS) rule locally, which does not explicitly coordinate departures at shared handover points. Our bi-level framework replaces this fragmented practice by jointly sequencing metroplex departures (upper level) and realizing TTOTs through pushback and taxi planning under surface-conflict constraints (lower level).

3.2. Problem Statement

Current tactical departure management operates independently per airport, resulting in uncoordinated convergence at shared waypoints under first-come, first-served (FCFS) principles. This fragmented approach causes three main issues. First, it leads to congestion and inefficient airspace utilization due to unplanned merging at shared waypoints. Second, it elevates controller workload because frequent manual interventions are required. Third, it creates systemic inequities in which certain airports gain persistent timing advantages.

In summary, independent airport scheduling yields suboptimal throughput and fragmented decision-making, failing to achieve system-wide optimization. These limitations necessitate an integrated air–ground coordination framework for the Beijing multi-airport system, which is achieved through a bi-level optimization model. The upper level coordinates departure sequencing across airports to allocate takeoff slots, while the lower level manages surface control (pushback timing and taxi routing) at each individual airport.

This integrated approach aims to minimize total departure delay and improve inter-airport fairness, ensuring that no single hub bears disproportionate waiting time while maintaining tactical-level consistency. Accordingly, our goal is a system-wide optimization that coordinates takeoff slots across airports while ensuring surface-level realizability and inter-airport equity.

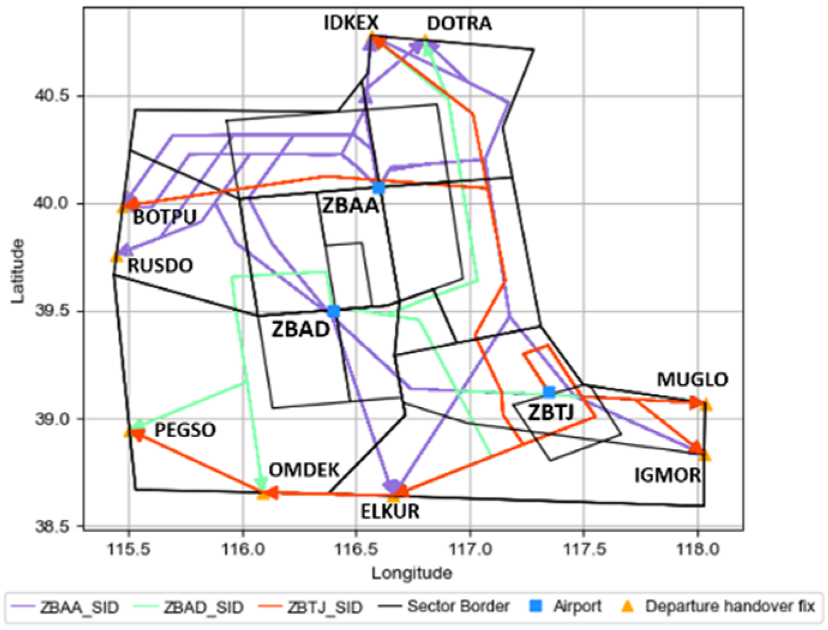

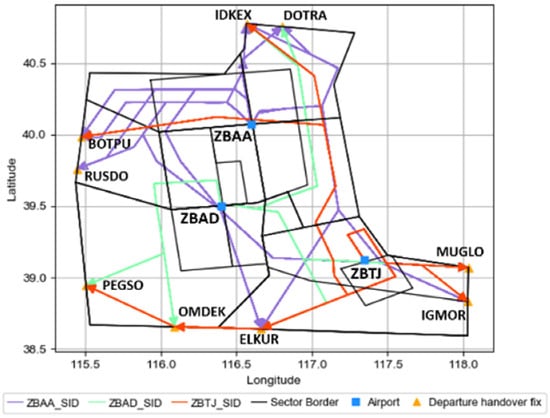

The Beijing terminal airspace comprises a multi-airport system with three major hubs: Beijing Capital (ZBAA), Beijing Daxing (ZBAD), and Tianjin Binhai (ZBTJ). The terminal airspace boundaries and the departure routes layouts are shown in Figure 1. These airports share common departure waypoints, as shown in Table 1, particularly ELKUR, IDKEX, and MUGLO, which serve as critical merge points for departures. ELKUR handles approximately one-quarter of total departures (ZBAA: 27.16%, ZBAD: 23.46%, ZBTJ: 25.47%), establishing it as a primary bottleneck during peak operations. While IDKEX and MUGLO accommodate lower traffic volumes, all shared points constrain departure throughput under high demand.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of departure routes in the Beijing Terminal Airspace.

Table 1.

Proportion of traffic volume at departure handover points.

3.3. Model Architecture

This section formulates the proposed bi-level optimization model tailored for the Beijing-Tianjin-Airport cluster, integrating terminal airspace sequencing with airport surface operations.

The upper-level model optimizes the coordinated departure sequence across the three airports within the terminal airspace. It is a multi-objective model designed to: (1) minimize total departure delay, (2) maximize aggregate airport satisfaction, and (3) minimize inter-airport fairness deviation. Its output is a set of TTOTs for all departure flights, facilitating equitable slot allocation at shared handover points.

The lower-level model, executed per airport, uses the TTOTs as inputs to schedule pushback times and taxi routes for departures. Its objective is to ensure runway readiness for the assigned slot while minimizing surface conflicts, taxi inefficiencies, and runway holding.

3.3.1. Model Assumptions

- Aircraft follow standard SIDs/STARs. Segment flight times are modeled as deterministic baseline values estimated from historical averages by aircraft category; deviations caused by winds or ATC vectoring are not explicitly optimized and are discussed as a limitation.

- Taxi movements are constrained by airport topology. For each flight, a small candidate set of feasible departure (gate–runway) or arrival (runway–gate) routes is generated via a k-shortest-path method and used as the decision space in the lower-level model.

- Taxiing is represented using unimpeded (no-stop) travel times as a baseline. Potential stops and conflicts are mitigated indirectly through pushback holding and route switching decisions, rather than being modeled as explicit stop-and-go dynamics.

- Arrival sequences are treated as exogenous inputs (FCFS in this study) and are not optimized. Departure sequences are optimized based on available runway slots.

- This article does not consider the impact of weather or unexpected flight events (such as special flights, flight emergencies, air force training, airport surface maintenance, etc.) on airport operations.

3.3.2. Variable Definitions

The model construction involves multiple airports, runways and attributes of individual flight arrivals and departures and so on. Therefore, the formulation introduces many symbols, making it difficult to explain their specific meanings in the main text. The specific meanings of these symbols are presented in Appendix A and Appendix B.

3.3.3. Upper-Level Model: Multi-Airport Departure Sequencing

The upper-level model is a multi-objective optimization framework with three primary goals: (1) minimizing total departure delay, (2) maximizing aggregate airport satisfaction, and (3) minimizing inter-airport fairness deviation. This integrated approach ensures a balance between system-wide efficiency, individual airport service quality, and equitable resource allocation.

- Minimizing Total Departure Delay

This objective seeks to minimize the cumulative delay across all departure flights, directly enhancing system efficiency. The mathematical formulation is:

where represents the delay for flight i, with denoting the optimized takeoff time and is calculated as the scheduled pushback time plus unimpeded taxi time.

- 2.

- Maximizing Overall Airport Satisfaction

This objective aims to maximize a composite satisfaction metric across all airports, incorporating both temporal and sequential performance indicators. The formulation is:

where , the satisfaction index of airport , aggregates normalized time deviation () and sequence position deviation () for all its departures:

The constituent deviations for flight are computed as:

Here, and represent extreme delay and sequence deviation values across all flights, ensuring normalized scoring.

The satisfaction metric is defined at the airport level to reflect inter-airport equity in terminal resource allocation. If airline preferences or flight priorities (e.g., emergencies, wide-body operations, passenger connections) are available, the formulation can be extended by introducing flight-specific weights in the aggregation, so that higher-priority flights contribute more to the satisfaction score. Such airline-level preference modeling is not included here due to data availability and to keep the focus on airport-level fairness.

- 3.

- Minimizing Fairness Deviation between Airports

This objective promotes equitable resource allocation by minimizing pairwise disparities in satisfaction levels among airports. The mathematical formulation is:

where and denote satisfaction values for distinct airports. Minimizing this sum ensures balanced operational performance and prevents systemic biases toward any single airport.

The upper-level model must satisfy the following constraints:

- 1.

- Handover Point Timing Relationship

The transit time between an airport and a handover point is modeled using historical average flight durations:

For departure flights:

For arrival flights:

- 2.

- Minimum Handover Separation Constraint

Consecutive flights passing through the same handover point must maintain a minimum safe separation to prevent conflicts:

- 3.

- Takeoff Interval Constraint

A minimum interval must be maintained between consecutive departures from the same runway, dependent on aircraft wake turbulence categories:

- 4.

- Mixed Interval Constraint

When an arrival follows a departure on the same runway, a safe mixed-mode separation must be ensured:

- 5.

- Segregated Departure–Arrival (DA) Interval Constraint

When a departure flight takes off from one of the segregated parallel runways, the subsequent arrival flight on the other runway must maintain a sufficient interval to avoid conflicts during landing. The constraint is formulated as:

- 6.

- Runway Occupancy Constraint

A departure can only be scheduled after a preceding arrival has vacated the runway:

- 7.

- Wake Turbulence Separation Constraint

Consecutive arrival flights on the same runway must comply with wake turbulence separation requirements (varying by aircraft type). The constraint is formulated as:

- 8.

- Dependent Parallel Approach Separation Constraint

For airports operating dependent parallel runways, a minimum diagonal separation must be maintained between successive arrivals on the closely spaced runways and to ensure safe simultaneous approach operations. The constraint is formulated as:

- 9.

- Maximum Delay Constraint

The target takeoff time of each departure flight must not exceed its earliest feasible runway entry time by more than the maximum allowable delay (set to 15 min in this study). The constraint is formulated as:

- 10.

- Position Deviation Constraint

To balance optimization benefits with schedule stability, the resequencing of flights is constrained. The deviation of a flight’s position in the optimized sequence from its original scheduled position must not exceed a predefined limit (set to 10 positions). The constraint is formulated as:

3.3.4. Lower-Level Model: Surface Scheduling and Conflict Resolution

The lower-level model optimizes airport surface operations, with the objective of minimizing a weighted combination of the total runway holding time of departure flights (from runway entry to target takeoff) and the total taxi time of both arrival and departure flights. The weights and (both positive coefficients) are introduced to balance these two objectives: prioritizes reducing runway holding time for departure flights (from runway entry to target takeoff), while prioritizes minimizing total surface taxi time (including departure taxi-out and arrival taxi-in). By adjusting these coefficients, the model allows flexible trade-offs between departure punctuality and surface traffic efficiency. In the multi-airport system, each airport can determine its optimal (,) combination via grid search, tailoring the trade-off between runway punctuality (minimizing holding) and surface efficiency (minimizing taxi time) to its unique operational features. Here, the runway entry time window and the runway holding-time term explicitly represent runway-threshold management (i.e., controlling how aircraft enter the runway system and how long they wait at the runway before takeoff).

Mathematically, this bi-objective optimization is formulated as:

where denotes the runway entry time of departure flight ; denotes the pushback start time of departure flight ; denotes the gate arrival time of arrival flight ; and denotes the runway exit time of arrival flight .

The lower-level model must satisfy the following constraints:

- 1.

- Node Separation Constraint

For any taxiway node and any two different flights the arrival times at node must satisfy a minimum separation:

- 2.

- Segment Speed Limit Constraint

For any flight i and its selected taxi path (with ), and for any segment :

- 3.

- Maximum Pushback Delay Constraint

The actual pushback time of each departure flight must not exceed its scheduled pushback time by more than the maximum allowable delay (set to 15 min in this study). This ensures predictable pushback operations and avoids excessive gate holding:

- 4.

- Runway Entry Time Window Constraint

For any departure flight , the runway entry time must fall within a feasible window defined by the earliest feasible runway entry time and the upper-level target takeoff time. This ensures alignment between ground operations and the target slot:

This constraint guarantees temporal consistency between ground operations and the target takeoff slot: aircraft will not arrive too early to wait unnecessarily at the runway threshold, nor too late to miss the allocated slot.

- 5.

- Overtaking Prohibition Constraint

For any taxiway segment and any two flights using the same segment (i.e., ), the order of flights must remain consistent to prohibit overtaking:

where and denote the relative order of flights and at nodes and , respectively.

- 6.

- Head-On Conflict Avoidance Constraint

For any undirected segment and any two flights (), if flight uses (from to ) and flight uses the opposite direction :

where is a binary variable, and M is a sufficiently large constant. This ensures temporal separation between conflicting direction flights. This constraint enforces temporal separation on the shared segment so that two flights cannot traverse it in opposite directions at the same time, thereby preventing head-on conflicts.

The surface taxiing structure in the Beijing Terminal Area is well-developed. Detour taxiing routes can be selected to replace runway crossings, thus avoiding conflict risks from runway crossings. Therefore, the impact of runway crossings during ground taxiing is not considered.

3.4. Algorithms

3.4.1. Overall Solution Framework

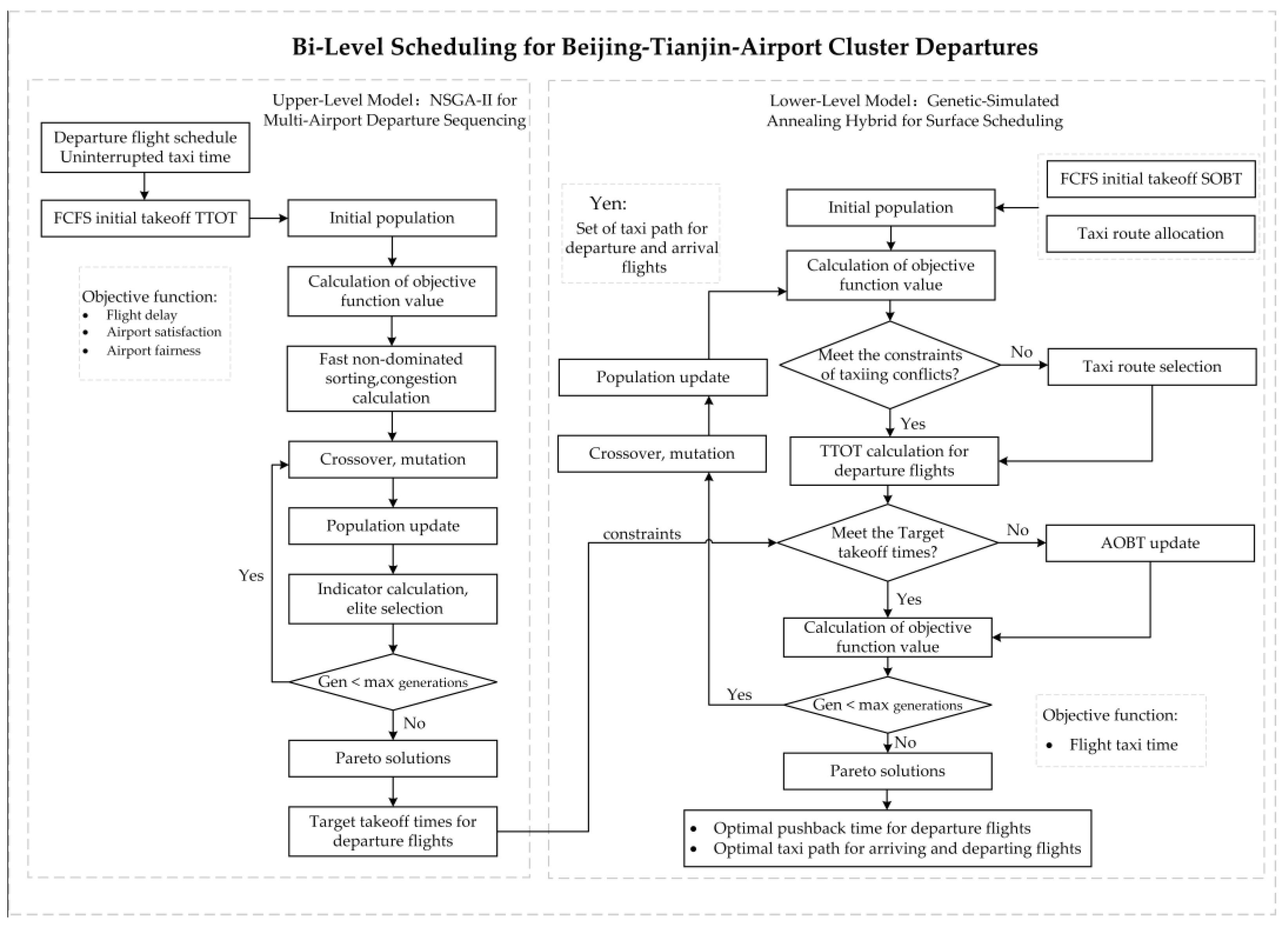

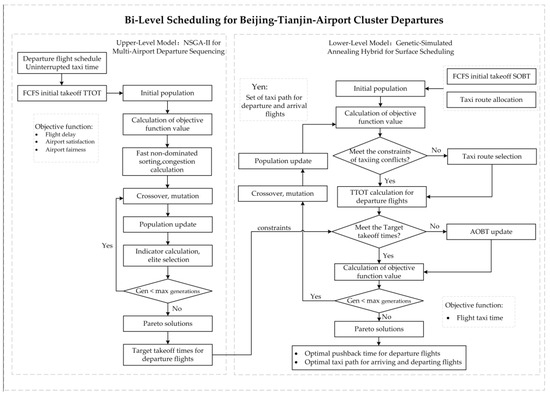

The proposed integrated scheduling model adopts a bi-level optimization structure. As shown in Figure 2, its solution process is divided into three sequential stages to ensure feasibility, efficiency, and consistency between airspace sequencing and surface operations:

Figure 2.

Bi-Level optimization flowchart for Beijing–Tianjin airport cluster departures solution.

- Preprocessing: Yen’s algorithm generates feasible taxi route sets.

- Upper-Level Optimization: NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II) solves the multi-objective problem to determine optimal target takeoff times () for all departures across the three airports.

- Lower-Level Optimization: A hybrid Genetic Algorithm-Simulated Annealing (GA-SA) algorithm refines surface operations—determining pushback times () and selecting taxi routes from precomputed sets—using upper-level as a constraint.

3.4.2. Preprocessing: Taxi Route Set Generation with Yen’s Algorithm

Each airport surface is represented as a directed graph , with nodes for stands, intersections, and runway entry/exit points, and edges for taxiway segments characterized by length and maximum allowable taxi speed . For each departure (stand → runway entry) and arrival (runway exit → stand), Yen’s [31] -shortest paths algorithm is used to construct a candidate set of feasible taxi routes. Here, k is set to 4, but due to topology constraints, the actual number of feasible alternatives per flight may be fewer (≤4). The output of this step is a path set for each flight , with associated unimpeded taxi times. These path sets constrain the decision variables of the lower-level optimization.

Yen’s algorithm (proposed in 1971) computes up to loopless shortest paths in weighted directed graphs via iterative perturbation of the shortest path tree. Its general procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. Yen’s -Shortest Paths for Taxi Route Generation |

| Inputs: Directed graph with edge weights w(e) Source node s, destination node t Maximum number of paths k |

| Outputs: Path set = {, , …, } (≤ k loopless shortest paths) |

| 1: ← ∅ ▷ Set of shortest paths

2: C← ∅ ▷ Candidate path set 3: ← Dijkstra(s, t, G) ▷ Compute first shortest path 4: P ←P∪{} 5: for r = 2 to k do 6: for = 1 to length() − 1 do 7: spur_node ←[i] 8: root_path ← prefix(, spur_node) 9: G’ ← G 10: Remove all nodes of root_path except spur_node from G′ 11: spur_path ← Dijkstra(spur_node, t, G′) 12: if spur_path exists then 13: total_path ← root_path ⊕ spur_path 14: C ← C∪{total_path} 15: end if 16: end for 17: if C = ∅ then 18: break ▷ No more feasible candidates 19: end if 20: ← path in C with minimum cost 21: Remove from C 22: P ← P ∪ {} 23: end for 24: return P |

3.4.3. Upper-Level Optimization: NSGA-II for Departure Sequencing

The upper-level model is solved using NSGA-II. Each solution encodes the departure order, which is decoded into feasible target takeoff times (TTOTs) while respecting all constraints (e.g., runway and handover separations, time windows). The specific algorithm flow is shown in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2. NSGA-II for Multi-Airport Departure Sequencing |

| Input: Departures with (runway, handover point, type) Arrivals with (landing time, runway, type) Separation parameters (runway, handover, mixed, wake/paired) Time windows , ; terminal flight times |

| Output: Pareto set of feasible schedules with target takeoff times |

| 1: Initialize population P with N = 400 individuals (random + FCFS seeds) 2: For each solution: 3: Decode chromosome → assign target takeoff times with repair 4: Evaluate objectives (Equations (1)–(3)) with penalties if needed 5: Fast non-dominated sort P; compute crowding distances 6: repeat 7: Select parents (binary tournament, preferring lower rank & larger crowding) 8: Apply crossover (dynamic probability ) and mutation (swap/insertion) 9: Decode offspring; repair and evaluate objectives 10: Merge parents and offspring into R 11: Perform fast non-dominated sorting on R 12: Select top N = 400 individuals by rank and crowding distance for next generation 13: until maximum generation reached or Pareto hypervolume stagnates 14: Return non-dominated set of schedules with target takeoff times |

In the upper-layer model, to ensure NSGA-II performance, the initial population is generated as follows: First, for each departing flight, a feasible take-off time window is calculated. The earliest take-off time is determined by adding conflict-free taxiing time to the scheduled pushback time. The latest take-off time accounts for a maximum 15 min delay. Subsequently, within each flight’s time window, take-off times are randomly selected to form multiple random take-off sequences (the initial solution set). The FCFS-derived take-off queue is also incorporated into this set to enhance population diversity.

For encoding, a sort-based integer method is used. Flights are numbered in order of planned pushback time (e.g., 0, 1, 2…), and the chromosome sequence indicates the take-off order.

Subsequently, Partially Mapped Crossover (PMX) generates offspring. Evolution proceeds via non-dominated sorting and elitism strategies, finally yielding the Pareto solution set.

The algorithm parameters are: population size = 400, generations = 200, crossover probability = 0.9, mutation probability = 0.02. Solutions are initialized from FCFS and random seeds. The three objectives (delay, satisfaction, fairness) are evaluated for each individual. Feasibility is maintained through repair strategies. Selection is based on non-dominated sorting and crowding distance.

For the upper level, infeasible TTOT assignments caused by separation violations are repaired by forward time-shifting the affected flights until all runway and handover constraints are satisfied; solutions exceeding the maximum delay or time-window limits receive penalty terms in the objective evaluation. For the lower level, node/edge conflicts are handled by (i) delaying pushback within the allowable bound, and/or (ii) switching to an alternative taxi route from the candidate set; remaining violations are penalized to guide the GA-SA search toward feasible regions.

3.4.4. Lower-Level Optimization: Genetic-Simulated Annealing Hybrid

This paper addresses the surface scheduling problem using a Genetic–Simulated Annealing (GSA) hybrid algorithm, which combines the global search capability of Genetic Algorithms with the local refinement capability of Simulated Annealing. This combination effectively balances exploration and exploitation while also avoiding premature convergence. Each feasible solution encodes the pushback times and selected taxi routes for all departures, as well as the taxi routes for all arriving flights. A repair procedure is applied to ensure that safety separation requirements, runway entry time windows, and other conflict constraints are all satisfied.

In the lower-level model, each departing flight in the initial population has two at-tributes: pushback time and taxiing route. First, flights are sorted by their initial scheduled pushback times. Within the maximum allowable delay of 15 min, a random delay duration is generated for each departing flight. This duration is added to the scheduled pushback time to determine the actual pushback time for each flight in the population. Available taxiing routes are encoded as 1, 2, 3, 4. One encoded route is randomly assigned to each arriving and departing aircraft to define its taxiing path attribute. These steps generate the lower-level initial population with complete attributes (pushback time and taxiing route). New individuals are created by crossover and mutation of the generated delay durations and route sets. In each iteration, the fitness of newly generated individuals is calculated and used to update the population, allowing the algorithm to gradually converge to the final solution set.

The algorithm processes inputs including taxi safety separations, scheduled pushback times and windows, predicted arrival runway-exit times, candidate taxi paths from Section 3.4.2, target takeoff times from the upper-level model, and taxiway geometry data, as shown in Algorithm 3. GA parameters are: population size , max generations , crossover probability , mutation . SA parameters are: initial temperature , terminal , cooling coefficient .

| Algorithm 3. Genetic-Simulated Annealing Hybrid for Surface Scheduling |

| Input: Candidate path sets for departures and arrivals ( ≤ 4) Target takeoff times {} Scheduled pushback times {}, max delay Segment data {, }, safety taxi separations |

| Output: Best feasible surface schedule minimizing Equation (4) |

| 1: Initialize GA parameters () and SA parameters (, ,) 2: Generate initial population of N individuals 3: Evaluate feasibility and compute objective with penalties 4: for gen = 1 to do 5: Apply selection, crossover, and mutation to generate offspring 6: For each child solution: 7: Apply repair for feasibility 8: Compute fitness (Equation (4)) 9: Apply SA local search around the child: 10: —Generate neighbor by perturbing pushback time or switching route 11: —If neighbor improves fitness, accept 12: —Else accept with prob 13: —Cool ← until below |

During each generation, GA operators generate offspring solutions that subsequently undergo SA-based local refinement. Neighbors are created by perturbing pushback times or swapping taxi routes, with fitness evaluated using Equation (4). The Metropolis criterion governs solution acceptance. Improved solutions are always accepted, whereas inferior solutions may still be accepted with a certain probability to escape local optima. The population updates through selection of optimal individuals, ensuring progressive enhancement across generations.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Operational Characteristics

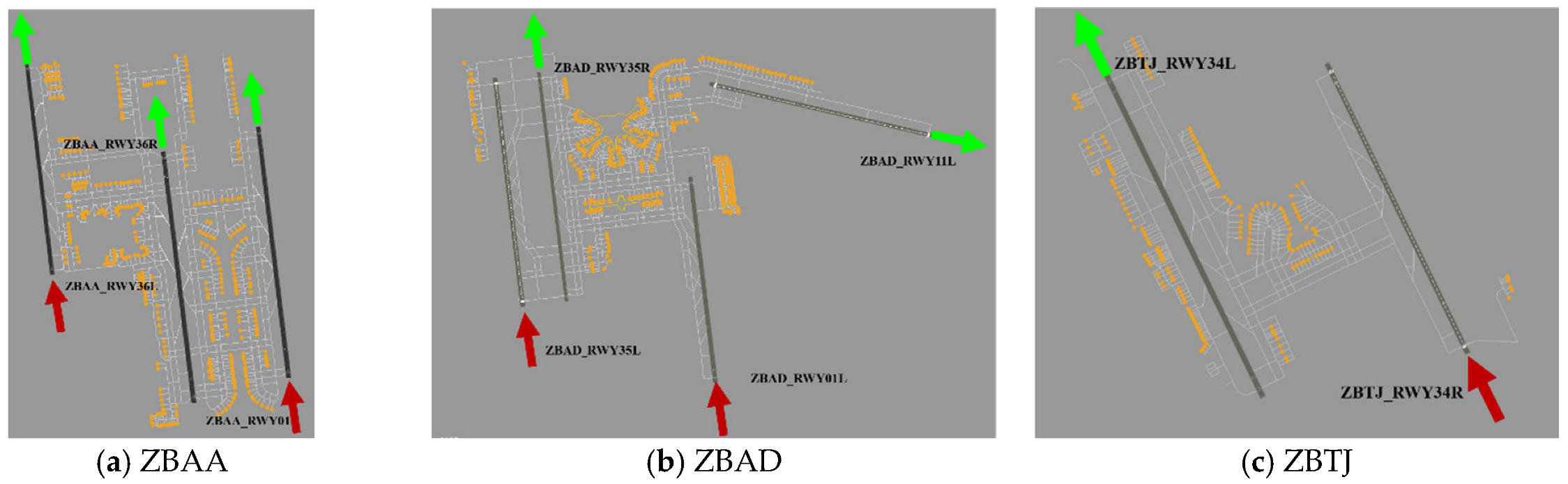

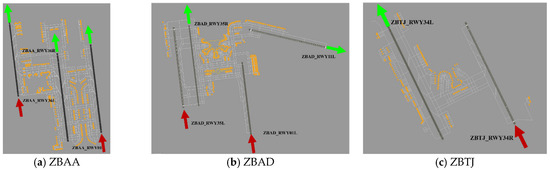

The evaluation utilizes real operational data from the Beijing-Tianjin-Airport (BTA) cluster, focusing on northbound operations at Beijing Capital (ZBAA), Beijing Daxing (ZBAD), and Tianjin Binhai (ZBTJ). The runway configurations for each airport are detailed in Table 2 and depicted in Figure 3, where red arrows indicate arrival directions and green arrows indicate departure directions.

Table 2.

BTA runway operation modes.

Figure 3.

Runway operation modes—northbound operations. (Red arrows indicate the runway landing direction, the green arrows indicate the runway takeoff direction, and the orange dots denote the parking stands.).

Data from 7 April 2023, obtained from the national Air Traffic Flow Management (ATFM) system, form the baseline scenario. The model was applied to the morning peak departure period (08:00–11:30). This window contained 252 departure flights (104 from ZBAA, 102 from ZBAD, 46 from ZBTJ) and 129 arrival flights (64, 46, and 19, respectively). Detailed schedules, including flight numbers, aircraft types, runway assignments, and Scheduled Off-Block Times (SOBT), are provided in Table 3. The “AD” column indicates the arrival and departure attributes of flights.

Table 3.

Sample flight schedule of BTA.

Unimpeded taxi times and average flight times to handover points were calculated from a week-long dataset (3–9 April 2023) to parameterize the model. Statistical summaries of these values are presented in Table 4 (unimpeded taxi times) and Table 5 (flight durations). This comprehensive data preparation establishes a robust foundation for evaluating the scheduling model under realistic conditions.

Table 4.

Sample statistics of unimpeded taxi times for departure flights at BTA (unit: s).

Table 5.

Sample statistics of average flight times from runway to handover points (unit: s).

4.2. Establishment of Taxi Route Sets

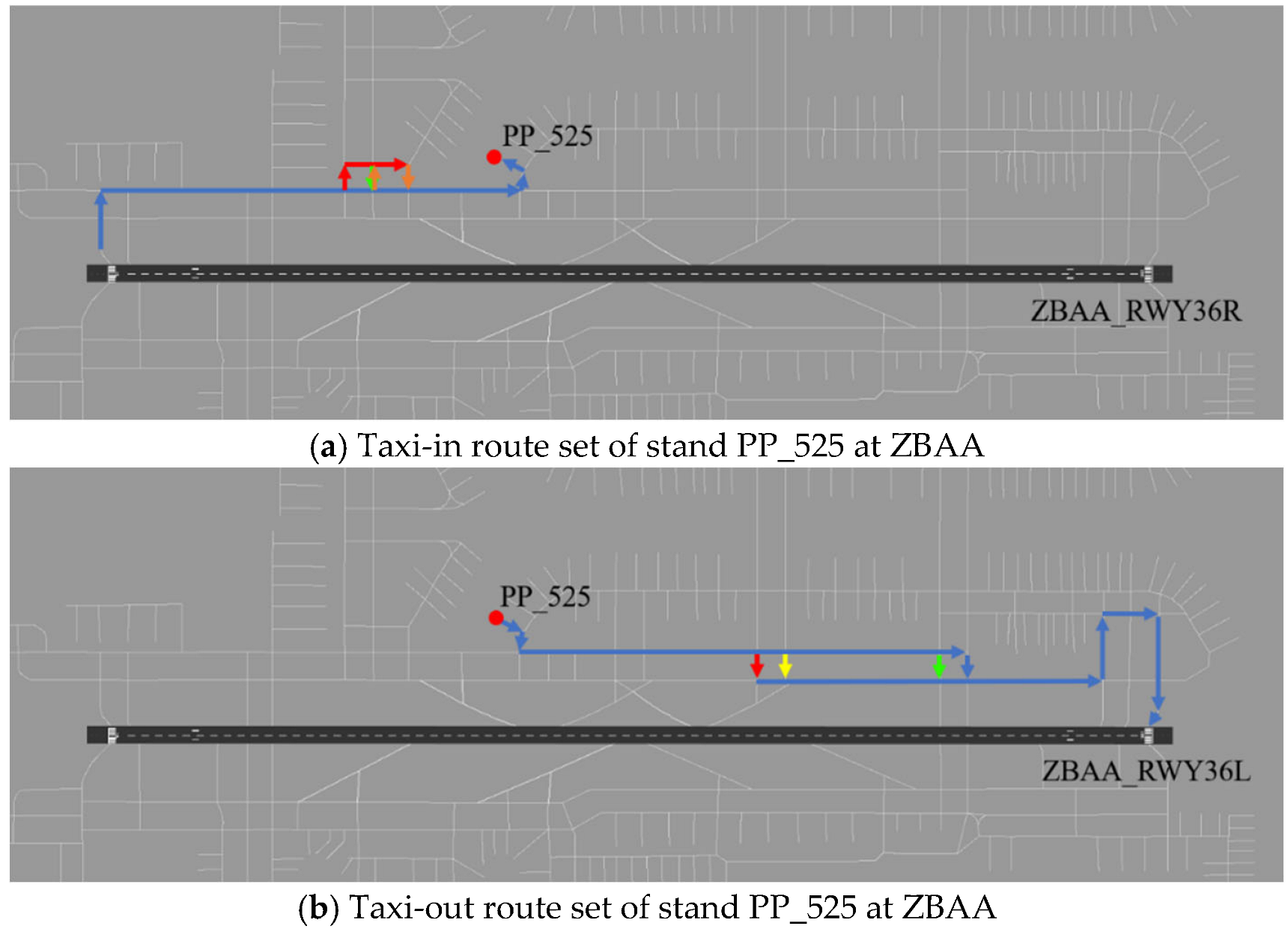

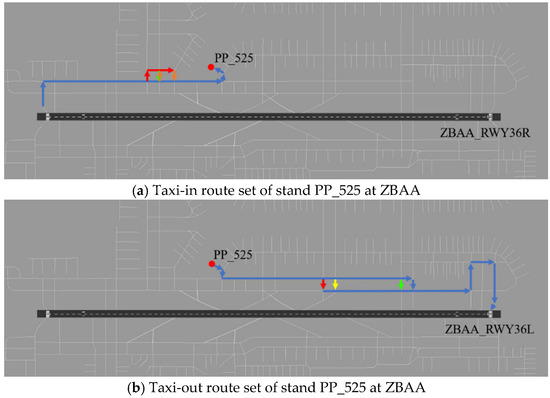

This section details the generation of taxi route sets for ZBAA, ZBAD, and ZBTJ. For each airport stand, four shortest paths to or from its corresponding runway were precomputed using the k-shortest path algorithm (k = 4) to ensure operational efficiency and minimize congestion.

The scale of the generated route sets is as follows: ZBAA (404 stands) yielded 4216 departure and 3232 arrival routes; ZBAD (330 stands) produced 2640 routes for both departures and arrivals; and ZBTJ (193 stands) generated 732 departure and 772 arrival routes.

Figure 4 exemplifies the resulting taxi route set for a stand (PP 525) at ZBAA, displaying the four candidate paths (distinguished by color) for both departure (gate-to-runway) and arrival (runway-to-gate) movements.

Figure 4.

Example of apron stand taxi route set (taxi-in/taxi-out routes for Stand PP_525 at ZBAA (arrows in different colors represent different shortest routes in the taxi-route set).

4.3. Computational Results

The upper-level and lower-level models were solved using the NSGA-II and GSA hybrid algorithms, respectively, with parameter settings as described in Section 3.4 The chromosome length for the upper-level model was set to 252, corresponding to the number of departure flights. Computational experiments performed on a Windows 10 system (Intel i5-7300HQ CPU @ 2.50 GHz) showed that the upper-level model required 16 min 48 s to converge, while the taxi scheduling models for ZBAA, ZBAD, and ZBTJ took 5 min 16 s, 4 min 58 s, and 3 min 46 s, respectively.

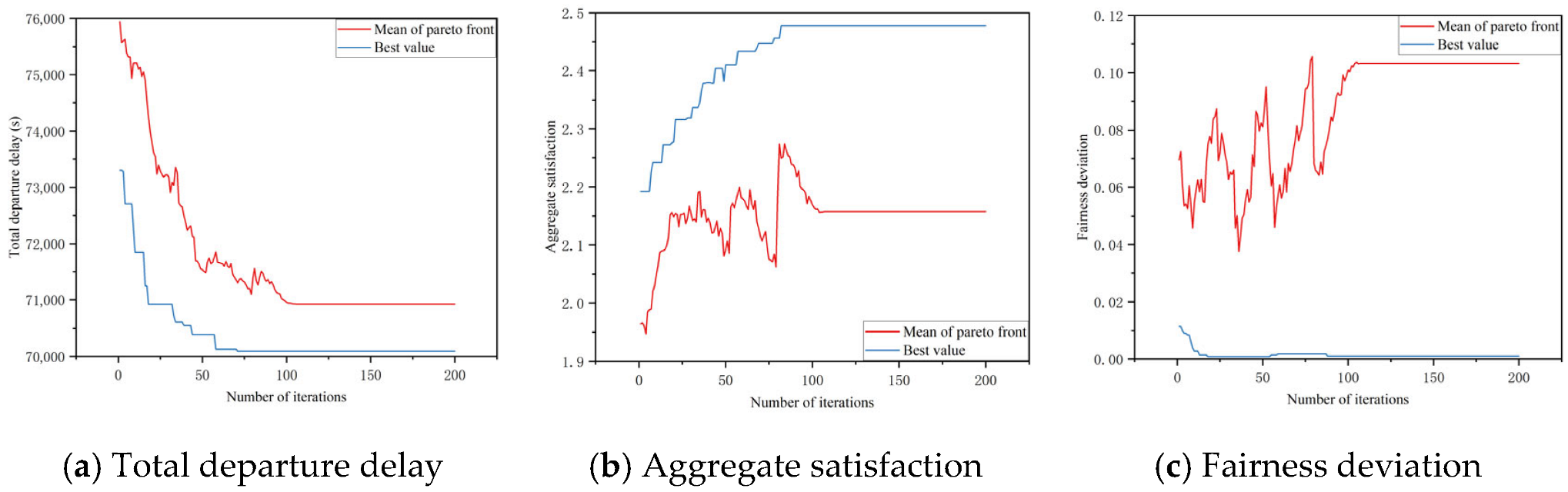

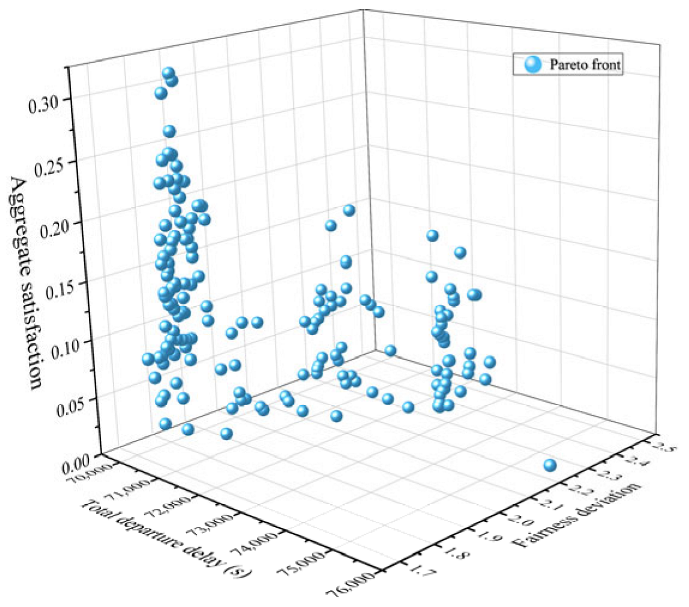

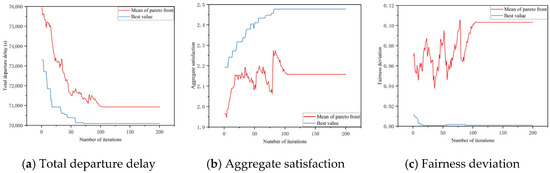

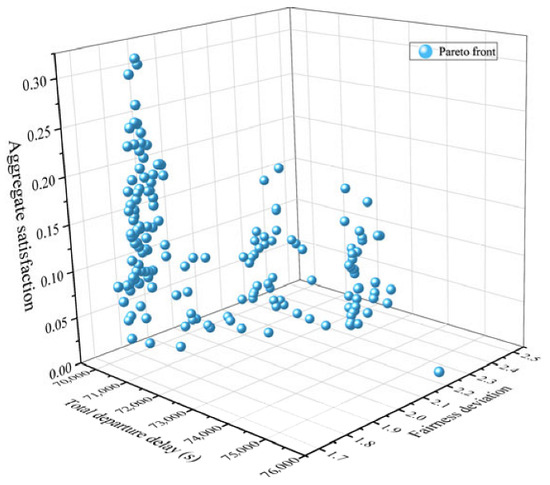

Figure 5 illustrates the convergence process of the upper-level model, clearly showing that the algorithm reaches a stable state after 100 iterations. Figure 6 then displays the final Pareto front after 200 iterations, where the population maintains this stable state. A representative solution (total delay: 70,968 s; aggregate satisfaction: 2.2766; fairness deviation: 0.1718), which corresponds to a 49.4% delay reduction and a 52.6% fairness improvement, was selected for subsequent lower-level optimization.

Figure 5.

Convergence process of the upper-level NSGA-II algorithm.

Figure 6.

Pareto front solutions for the upper-level model.

This selected Pareto solution was then used as input for the lower-level taxi scheduling models. The lower-level model employs a dual-objective function, minimizing a weighted sum of departure delay time and total taxi time. A grid search was conducted to determine the optimal weight coefficients (,) for each airport, which balance the trade-off between these two objectives. The resulting optimal parameters and corresponding performance for each airport are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Performance of and coefficient combinations for the lower-level model’s objective function (unit: s).

- For ZBAA, = 0.98 and = 0.02, resulting in an optimized runway holding time of 2259 s and total taxi time of 113,728 s;

- For ZBAD, = 0.96 and = 0.04, resulting in an optimized runway holding time of 2400 s and total taxi time of 78,949 s;

- For ZBTJ, = 0.90 and = 0.10, resulting in an optimized runway holding time of 1623 s and total taxi time of 36,181 s.

The optimized scheduling results for the upper- and lower-level models are shown in Table 7 and Table 8 respectively.

Table 7.

The optimization results of takeoff time of upper-level model.

Table 8.

The optimization results of pushback time of lower-level model (unit: s).

4.4. Analysis

4.4.1. Departure Flight Delay Time Analysis

This section presents a comparative evaluation of the First-Come-First-Served (FCFS) strategy and the proposed Air–Ground Collaborative Scheduling approach for multi-airport departure operations. The optimized strategy utilizes a bi-level model to generate efficient departure sequences and target takeoff times, while coordinating ground operations to minimize delays and enhance overall efficiency.

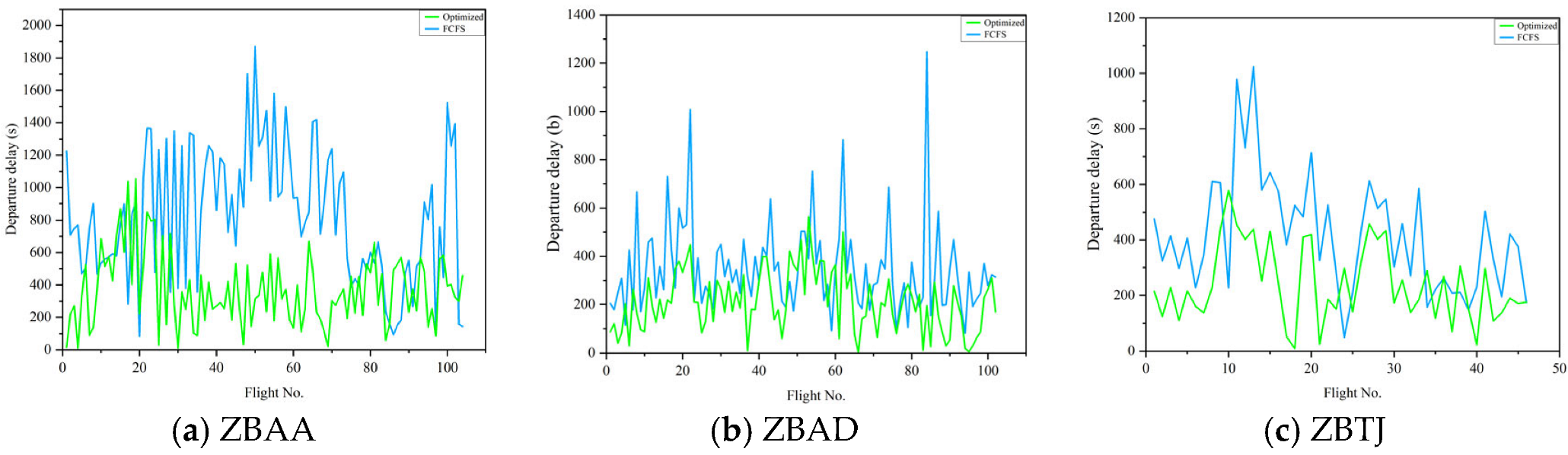

Based on operational data from the Beijing-Tianjin-Airport (BTA) cluster, the optimized strategy demonstrates substantial improvements across key performance metrics. As summarized in Table 9, it achieves a 49.4% reduction in total departure delay (69,351 s) compared to FCFS. Among all 252 departure flights, 207 (82.1%) experience lower delays under the optimized strategy. Notably, the optimized approach not only reduces total and average delays but also effectively controls maximum delay.

Table 9.

Comparison of departure flight delay times under different strategies (unit: s).

Table 10 details the delay improvements at each airport. Under FCFS, total delays at ZBAA, ZBAD, and ZBTJ are 85,801 s, 35,394 s, and 19,124 s, with average delays of 825 s, 347 s, and 415 s, respectively. The optimized strategy reduces these totals to 38,425 s (55.2% reduction), 21,525 s (39.2% reduction), and 11,018 s (42.4% reduction), with average delays decreasing to 369 s, 211 s, and 239 s. At the individual flight level, 81 (77.9%), 87 (85.3%), and 39 (84.8%) flights at ZBAA, ZBAD, and ZBTJ, respectively, show reduced delays compared to FCFS.

Table 10.

Comparison of departure flight delay times at each BTA airport under different strategies.

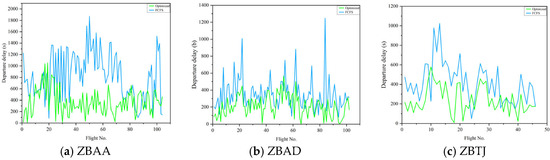

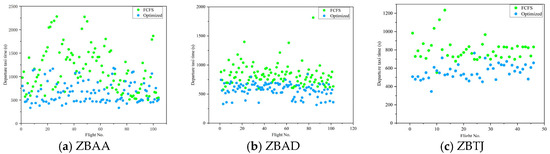

The standard deviation of average delays across airports decreases from 211.0 s to 68.8 s, indicating enhanced operational stability and consistency. Figure 7 visually confirms these improvements, showing reduced delay distributions across all three airports under the optimized strategy.

Figure 7.

Comparison of delay time distribution under different strategies.

4.4.2. Airport Satisfaction and Fairness Deviation Analysis

The optimized strategy significantly enhanced both airport-level satisfaction and system-wide fairness compared to the FCFS approach. As summarized in Table 11, satisfaction increased at ZBAA (from 0.7212 to 0.7902, +9.6%) and ZBTJ (from 0.6304 to 0.7043, +11.7%), while ZBAD experienced a slight reduction (0.8118 to 0.7821, −3.7%) due to scheduling adjustments aimed at balancing multi-airport efficiency. Overall, aggregate satisfaction rose by 5.2% (from 2.1634 to 2.2766). More notably, fairness deviation—reflecting inter-airport satisfaction disparity—decreased dramatically by 52.6% (from 0.3628 to 0.1718), indicating a more equitable distribution of terminal resources.

Table 11.

Airport satisfaction and fairness deviation under different strategies.

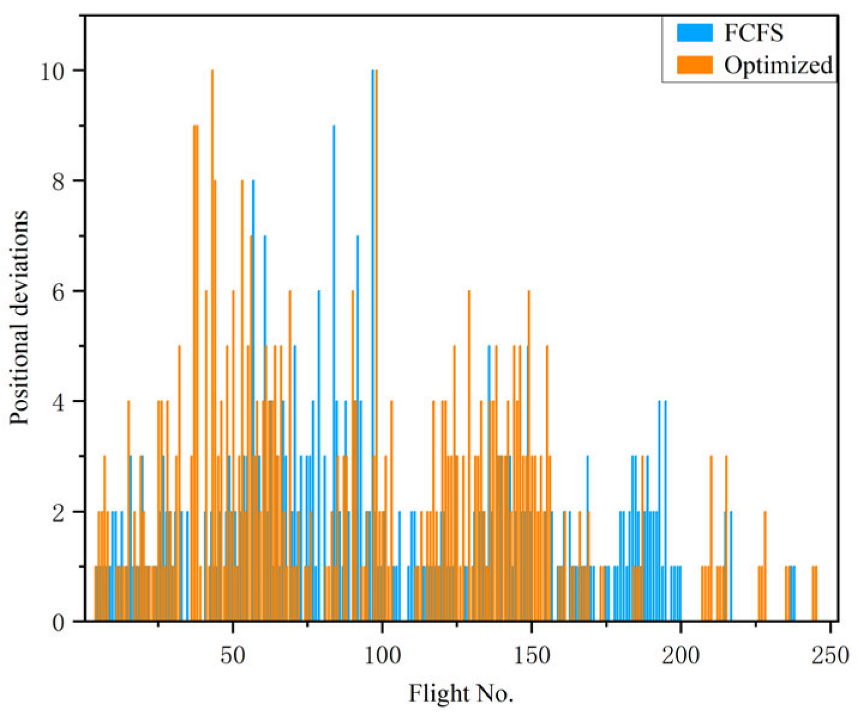

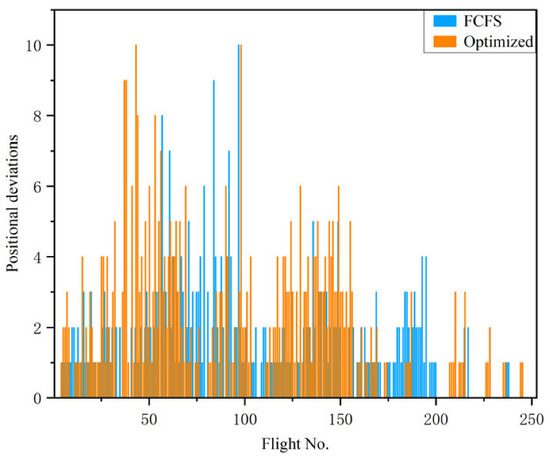

Position deviation analysis (measuring sequence adjustments from the initial FCFS order) revealed that the optimized strategy induced marginally higher but well-controlled deviations, as shown in Figure 8 and Table 12. The average deviation increased from 1.32 to 1.72 units, while the maximum deviation remained capped at 10 units. Flights with zero deviation decreased slightly from 96 to 94, confirming that sequence changes were minimal and operationally stable.

Figure 8.

Comparison of departure flight position deviation under different strategies.

Table 12.

Departure flight position deviation statistics under different strategies (mean and maximum).

Critically, the optimized strategy balanced deviation levels across airports—narrowing the inter-airport gap in sequence adjustments—which alleviated uneven departure pressure and promoted coordinated use of terminal airspace. This approach thus achieved dual goals: enhancing operational efficiency and ensuring fairness across the multi-airport system.

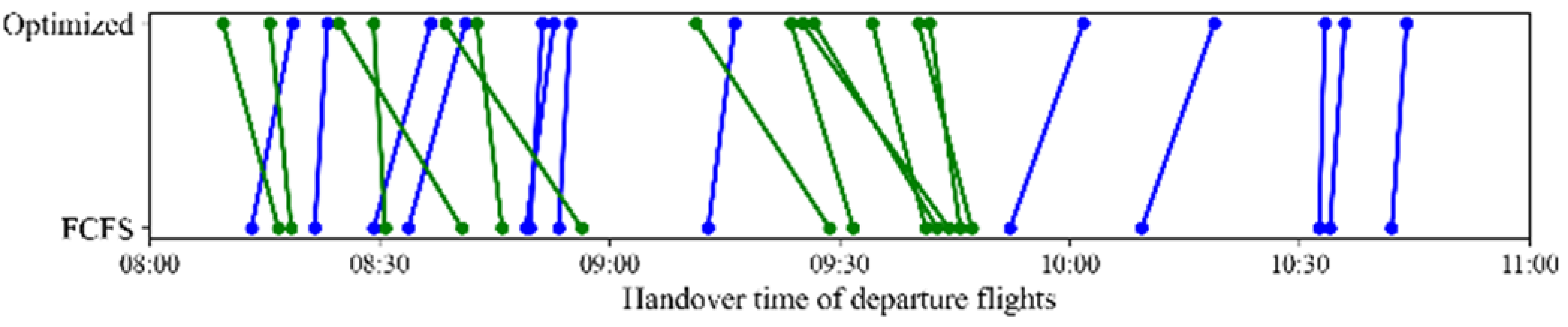

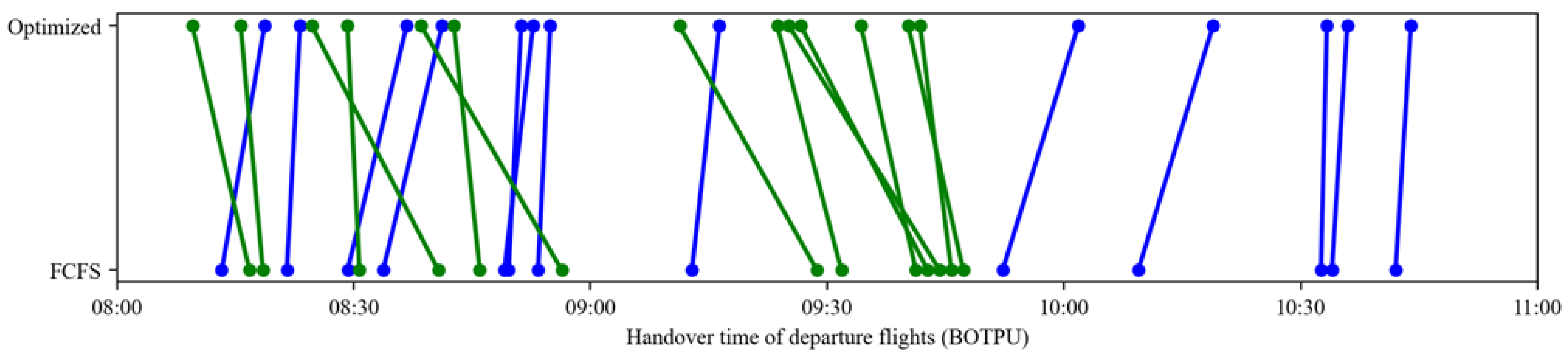

4.4.3. Departure Handover Point Resource Allocation Analysis

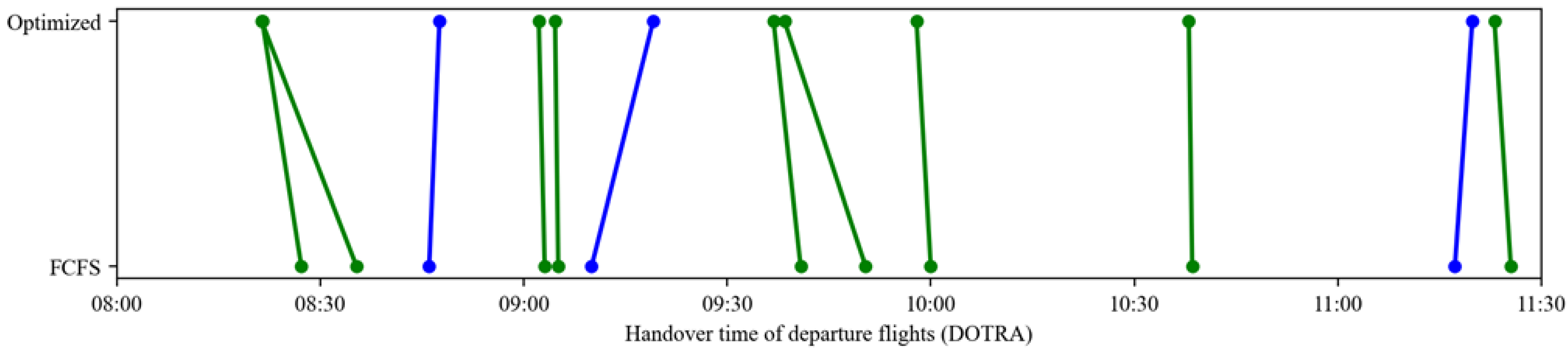

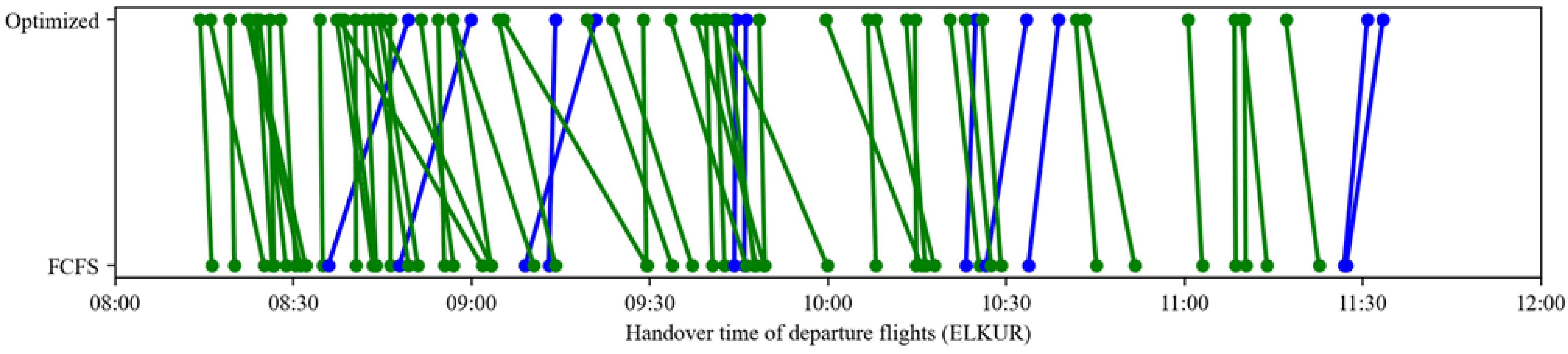

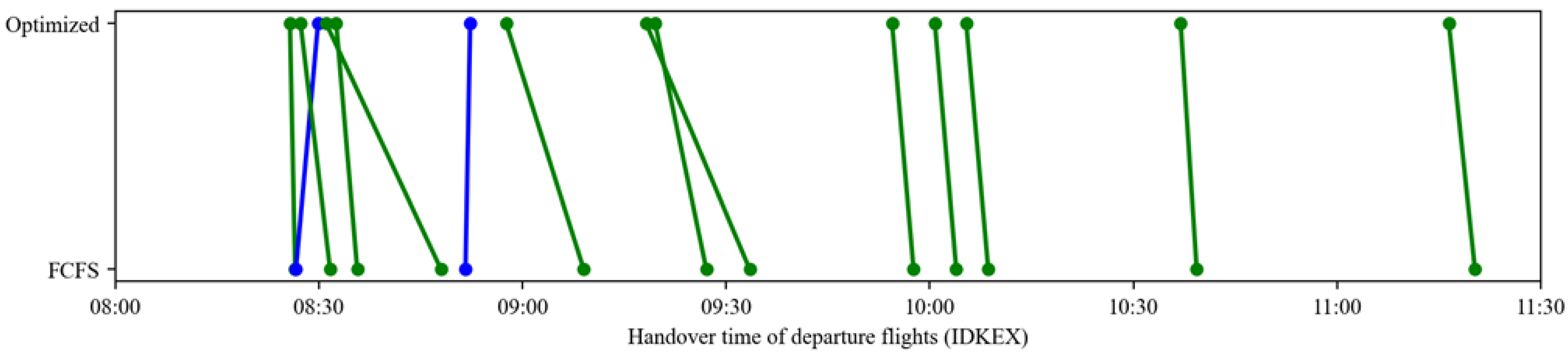

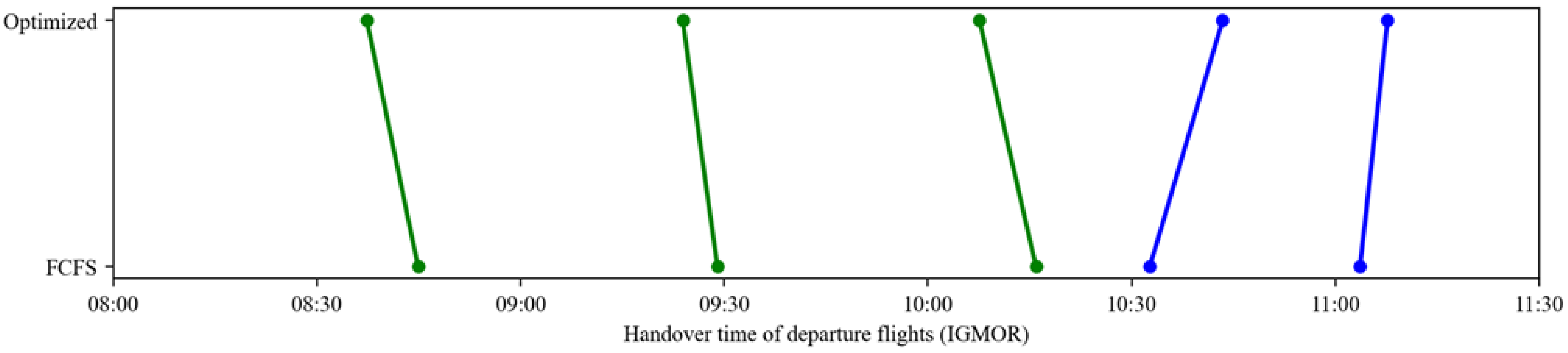

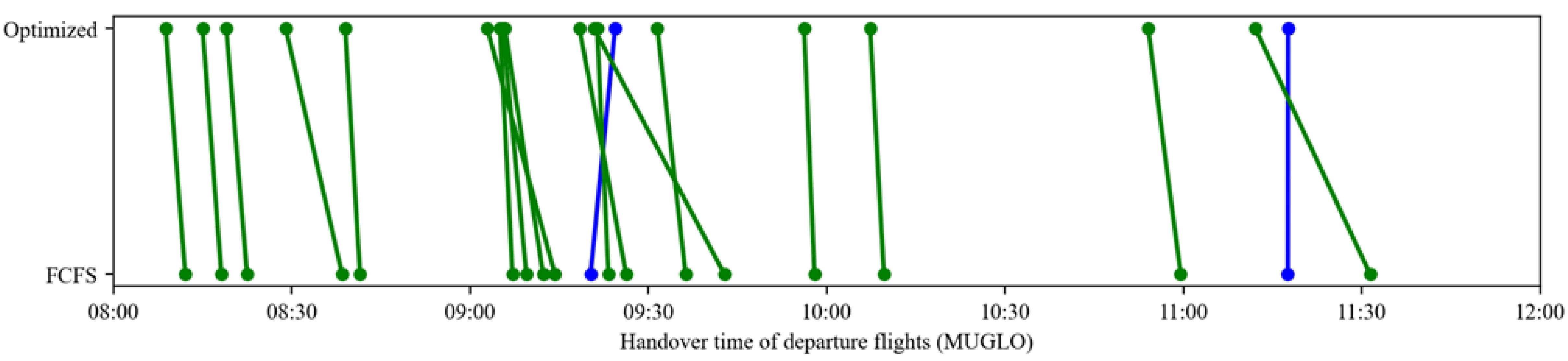

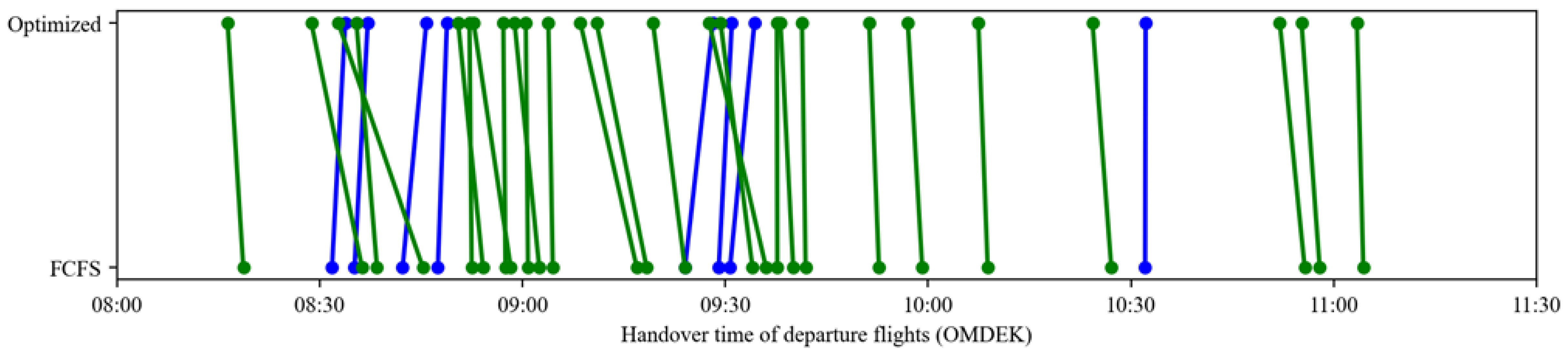

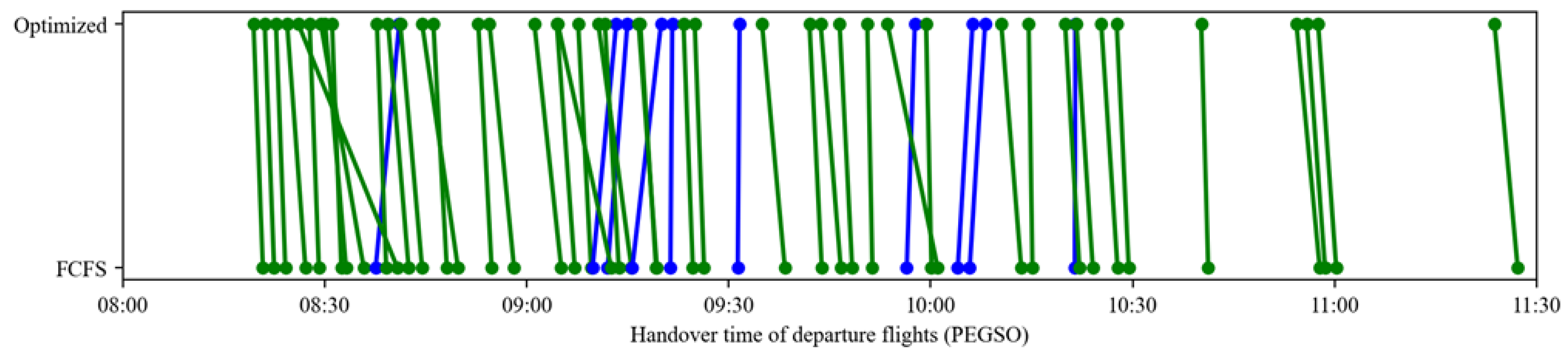

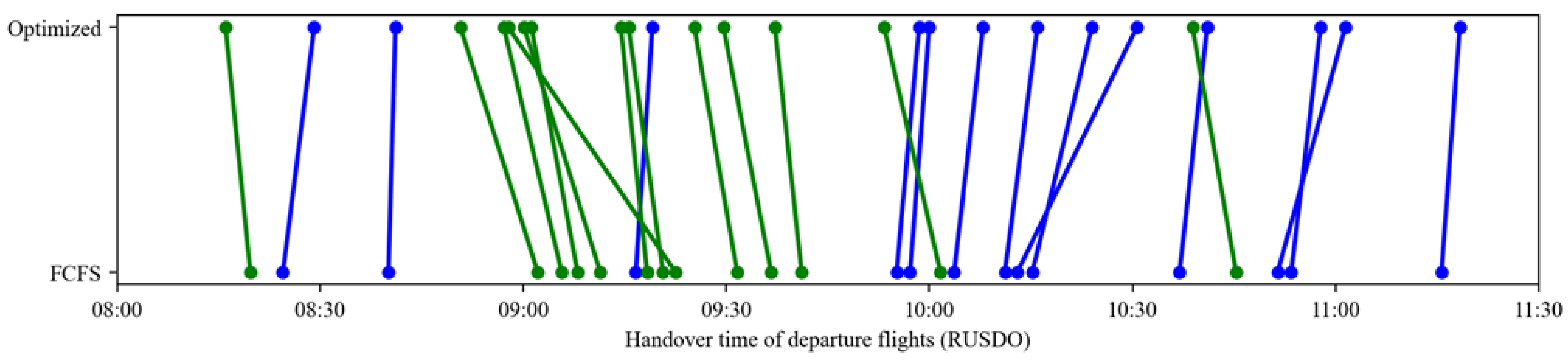

Table 13 compares flight sequencing changes at the nine departure handover points under the optimized and FCFS strategies. Green lines represent flights arriving earlier with optimization, while blue lines indicate later arrivals. The results demonstrate that the optimized strategy enables most flights to reach handover points ahead of their FCFS schedules, directly reducing waiting times and improving throughput efficiency at these critical nodes.

Table 13.

Comparison of flight sequencing at departure handover points under different strategies (green lines denote flights with earlier optimized arrival times, whereas blue lines denote flights with later optimized arrival times).

Notably, sequence adjustments are most significant at high-traffic handover points (e.g., ELKUR, PEGSO), where dynamic departure time optimizations alleviate congestion caused by resource saturation under FCFS. In contrast, low-traffic points (e.g., DOTRA, IGMOR) maintain stable sequencing with minimal changes, avoiding unnecessary adjustments. This differentiated performance highlights the strategy’s targeted optimization capabilities, enhancing efficiency at bottleneck nodes while preserving stability elsewhere, thus adapting effectively to diverse operational scenarios in the multi-airport system.

The delay reduction mainly stems from two coupled effects. First, the upper-level metroplex sequencing redistributes departure demand across airports while enforcing separations at shared handover fixes, which mitigates queue spillback and compression at bottleneck fixes. Second, the lower-level gate holding and route switching convert the assigned TTOTs into conflict-free surface trajectories, reducing stop-and-go taxiing and runway-threshold waiting. Therefore, the benefits are most pronounced during peak periods when handover-point and runway constraints are binding; under light traffic, FCFS and the optimized strategy tend to perform similarly.

4.4.4. Surface Taxiing Results Analysis

The optimized strategy demonstrates significant improvements in surface operations compared to the FCFS approach, as summarized in Table 14. Under FCFS, total runway waiting times for departures were 7682 s (ZBAA), 8412 s (ZBAD), and 7716 s (ZBTJ), with average waits of 74 s, 82 s, and 168 s, respectively—highlighting ZBTJ’s disproportionately higher delays. The optimized strategy drastically reduced these times: total runway waiting decreased by 70.6% (to 2259 s), 71.5% (to 2400 s), and 79.0% (to 1623 s) across the three airports, while average waits fell to 22 s, 24 s, and 35 s. This reduction also narrowed inter-airport disparities, achieved through the fairness-oriented design of the upper-level model, which balances airport satisfaction to ensure equitable terminal airspace allocation.

Table 14.

Comparison of taxiing, runway waiting, and pushback waiting times under different strategies (unit: s).

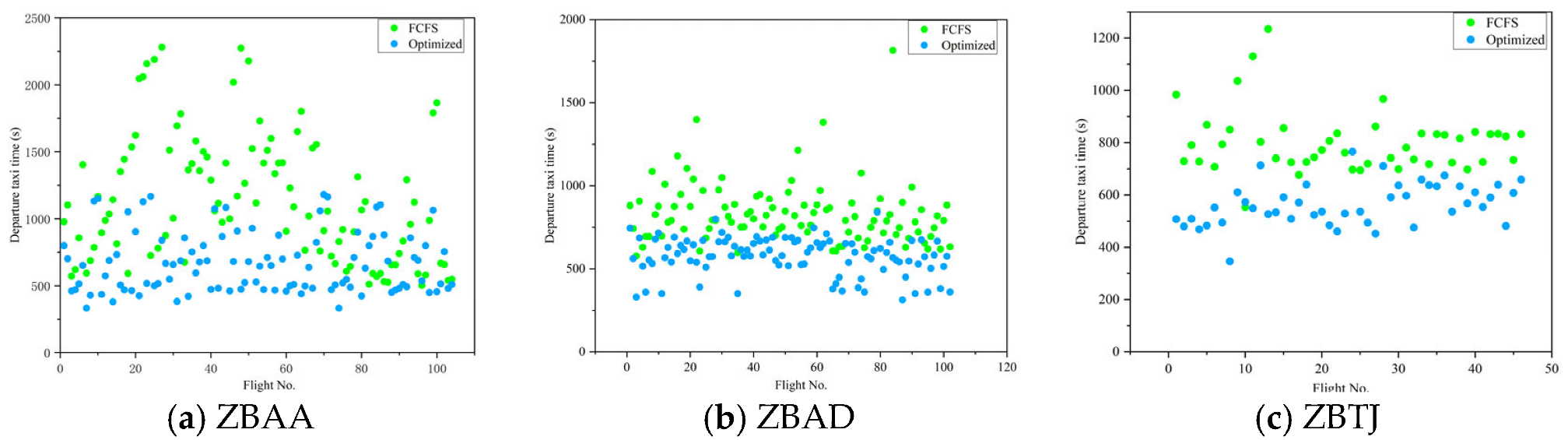

Taxi times saw substantial reductions under optimization. FCFS resulted in total taxi times of 115,818 s (ZBAA), 81,820 s (ZBAD), and 33,831 s (ZBTJ), with averages of 1114 s, 802 s, and 735 s, respectively. The optimized strategy lowered these values significantly, as visualized in Figure 9, due to reduced taxi conflicts and optimized path selection. This improvement stems from the algorithm’s ability to minimize holding points and ensure smoother taxi flows, directly addressing congestion issues under FCFS.

Figure 9.

Comparison of departure taxi times under different strategies.

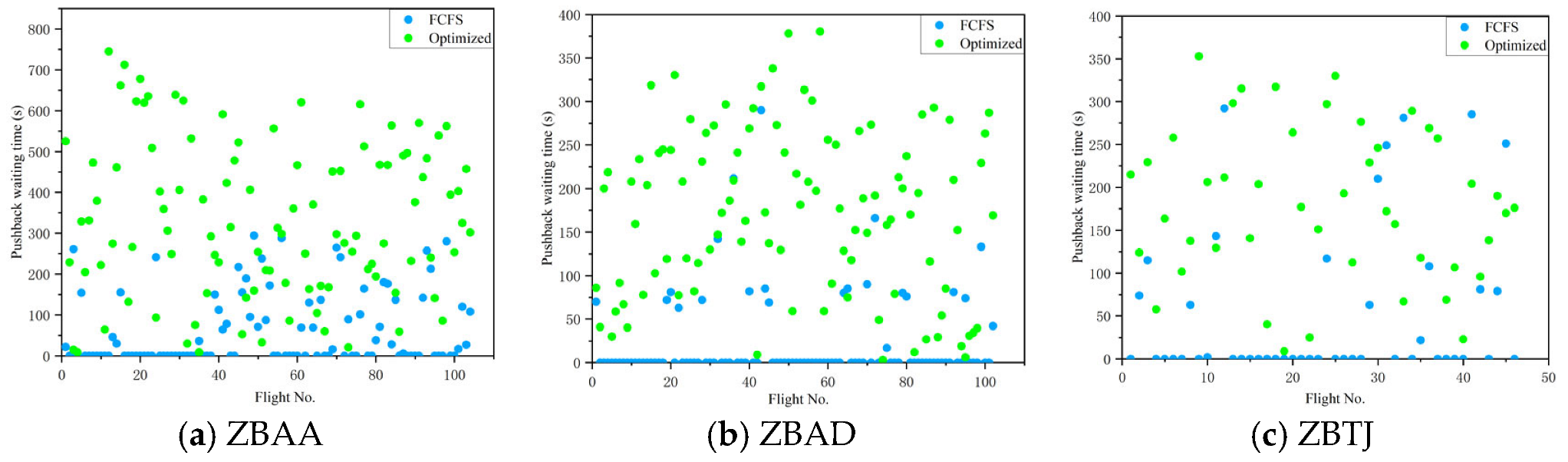

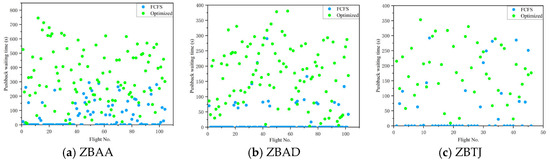

Figure 10 compares the pushback waiting times for departure flights under both strategies. Under the optimized strategy, pushback waiting times increased by 28,424 s (ZBAA), 15,363 s (ZBAD), and 5877 s (ZBTJ) compared to FCFS. However, this increase was offset by larger reductions in total taxi time: 46,840 s (ZBAA), 23,221 s (ZBAD), and 7891 s (ZBTJ), which lowered average departure taxi time to 663 s (40.4% reduction), 575 s (28.4% reduction), and 564 s (23.3% reduction), respectively. More importantly, the total surface stay time (a comprehensive metric encompassing taxi time, runway waiting time, and pushback waiting time) for departure flights decreased significantly: from 129,736 s to 105,897 s (18.4% reduction) at ZBAA, 92,394 s to 78,524 s (15.0% reduction) at ZBAD, and 43,982 s to 35,875 s (18.4% reduction) at ZBTJ, as shown in Table 14. These results confirm that while the optimized strategy led to a partial increase in pushback waiting time, it ultimately reduced overall surface stay time through rational pushback time control and taxi path optimization, effectively improving the overall operational efficiency of the airports.

Figure 10.

Comparison of pushback waiting times under different strategies.

Pushback waiting times increased under the optimized strategy—by 28,424 s (ZBAA), 15,363 s (ZBAD), and 5877 s (ZBTJ)—as shown in Figure 10. However, this was more than offset by larger reductions in taxi time (46,840 s, 23,221 s, and 7891 s, respectively), leading to net gains in efficiency. Average taxi times fell to 663 s (40.4% reduction), 575 s (28.4% reduction), and 564 s (23.3% reduction). Crucially, total surface stay time (combining taxi, runway waiting, and pushback times) decreased across all airports: by 18.4% at ZBAA (to 105,897 s), 15.0% at ZBAD (to 78,524 s), and 18.4% at ZBTJ (to 35,875 s). This confirms that the optimized strategy’s rational pushback control and taxi path optimization enhance overall operational efficiency despite localized increases in pushback delays.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a bi-level optimization model for coordinated departure scheduling across the Beijing-Tianjin-Airport cluster, addressing the integration of terminal-area sequencing and surface operations. The upper-level model minimizes total delays, maximizes airport satisfaction, and reduces fairness deviation, while the lower-level model optimizes taxi routes and pushback times to mitigate surface congestion. Empirical evaluation using operational data demonstrated that the proposed approach significantly outperforms the traditional FCFS strategy: it achieved a 49.4% reduction in total departure delay, a 5.2% improvement in aggregate airport satisfaction, and a 52.6% decrease in inter-airport fairness deviation. These results highlight enhanced operational efficiency and more equitable resource allocation.

The proposed model is formulated as a deterministic baseline using historical-average flight times and unimpeded taxi times. In practice, weather, ATC interventions, and stochastic surface interactions may introduce variability that can reduce feasibility margins (e.g., tighter runway-entry windows) and alter the delay trade-offs. Incorporating stochastic buffers, robust optimization, or online state-updated rolling-horizon re-optimization would be an extension.

Additionally, the strategy reduced taxi times and runway holding through optimized ground coordination, lowering overall surface stay times and improving system resilience. Methodologically, this work showcases the value of multi-objective optimization in balancing efficiency and equity in complex air traffic management. Practically, it offers actionable insights for developing collaborative decision-support tools in congested multi-airport environments. Future research will focus on incorporating stochastic disturbances (e.g., weather and demand uncertainty) and exploring real-time adaptive scheduling via digital twin simulations, with deployment requiring integration into existing ATFM systems and stakeholder training. In particular, a rolling-horizon implementation can be developed by updating TTOT assignments every Δt minutes using the latest surface states and predicted uncertainties. The lower level can return feasibility indicators (e.g., minimal required gate holding or infeasibility penalties) as feedback signals to guide the upper-level re-optimization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.P. and B.J.; Methodology, Z.W.; Software, Z.W.; Formal analysis, Z.W.; Writing—original draft, Z.W.; Writing—review and editing, Z.W. and Y.P.; Visualization, L.R.; Supervision, Y.P.; Project administration, Y.P.; Funding acquisition, Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFB2602401) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52472345).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with the airport authority. These data contain sensitive operational information related to real-world airport surface movements and cannot be shared publicly for privacy and security reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely acknowledge this funding support, which laid a critical foundation for the implementation of this study. The authors would also like to express gratitude to Capital Airports Holdings Co., Ltd. for providing the historical operation data required for this research. The availability of this data was essential to the analysis and conclusions of the study. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors did not use generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools for content creation, data analysis, model design, or result interpretation. Minor grammar and formatting checks were performed using standard editing tools, and all authors have reviewed, edited, and take full responsibility for the entire content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zhaokun Wan was employed by the company Xiaomi Communications Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATFM | Air Traffic Flow Management |

| BTA | Beijing-Tianjin-Airport |

| FCFS | First-Come-First-Served |

| GA-SA | Genetic-Simulated Annealing |

| MAS | Multi-Airport Systems |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming |

| NSGA-II | Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II |

| SID | Standard Instrument Departure |

| SOBT | Scheduled Off-Block Time |

| AOBT | Actual Off-Block Time |

| STARs | Standard Terminal Arrival Routes |

| TTOT | Target Takeoff Time |

| ZBAA | Beijing Capital Airport |

| ZBAD | Beijing Daxing Airport |

| ZBTJ | Tianjin Binhai Airport |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Variables and definitions.

Table A1.

Variables and definitions.

| Type | Variable | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Set | set of airports | |

| set of departure flights across all airports | ||

| set of all runways across all airports | ||

| set of taxiway nodes | ||

| set of handover points | ||

| Parameter | length of taxiway segment (u, v) | |

| maximum deviation from the scheduled departure sequence positions across all flights | ||

| minimum deviation from the scheduled departure sequence positions across all flights | ||

| maximum departure delay among all flights | ||

| minimum departure delay among all flights | ||

| maximum allowable departure delay | ||

| ) under the scenario of segregated parallel runway operations | ||

| , depending on aircraft types | ||

| minimum required wake turbulence separation between two consecutive arrival flights to the same runway, determined by the wake turbulence categories defined in operational standards | ||

| under dependent parallel runway approach operations | ||

| minimum safe separation at taxiway | ||

| optimized by upper-level model | ||

| , which varies depending on the aircraft type and runway structure | ||

| weighting coefficients that balance runway holding time and taxi time. | ||

| Decision Var | binary variable equal to one if flight i chooses taxi path p, and equal to zero otherwise | |

| binary variable equal to one if flight i enters the taxi segment (u,v) before flight j in the opposite direction, and equal to zero otherwise | ||

| Others | arbitrarily large number (i.e., big-M) |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Handover separation (unit: km).

Table A2.

Handover separation (unit: km).

| Handover Point | ||

|---|---|---|

| Same Route, Same Altitude Departure | Other Situations | |

| BOTPU | 25 | 15 |

| DOTRA | 25 | 15 |

| ELKUR | 25 | 25 |

| IDKEX | 25 | 15 |

| IGMOR | 25 | 25 |

| MUGLO | 25 | 25 |

| OMDEK | 25 | 15 |

| PEGSO | 25 | 15 |

| RUSDO | 25 | 15 |

Table A3.

Wake turbulence separation (unit: km).

Table A3.

Wake turbulence separation (unit: km).

| Succeeding Aircraft | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preceding Aircraft | Heavy | Medium | Light |

| Heavy | 7.4 | 9.3 | 11.1 |

| Medium | 6 | 6 | 9.3 |

| Light | 6 | 6 | 6 |

Table A4.

Operational parameter settings.

Table A4.

Operational parameter settings.

| Airport | Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZBAA | 100 s (heavy followed by medium); 90 s (other combinations) | 36L:7.5 km; 01:5 km | / | / |

| ZBAD | 100 s | / | 01L&35L:4 km | 35L/35R:6.5 km |

| ZBTJ | 120 s | / | / | 34L/34R:7 km |

Table A5.

Runway occupancy time for arrival flights (unit: s).

Table A5.

Runway occupancy time for arrival flights (unit: s).

| Airport | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Aircraft Type | ZBAA | ZBAD | ZBTJ |

| Heavy | 61 | 61 | 60 |

| Medium | 56 | 56 | 60 |

| Light | / | / | 60 |

Table A6.

Taxi safe separation (unit: m).

Table A6.

Taxi safe separation (unit: m).

| Succeeding Aircraft | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preceding Aircraft | Heavy | Medium | Light |

| Heavy | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| Medium | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Light | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Table A7.

Maximum taxi speed (unit: km/h).

Table A7.

Maximum taxi speed (unit: km/h).

| Parameter | Ramp Speed | Taxiway Speed | Vacate Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 90 | 55 |

References

- Civil Aviation Administration of China. 2024 National Civil Aviation Flight Operation Efficiency Report; CAAC: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, L.; Gardi, A.; Sabatini, R. Operational Efficiency Analysis of Beijing Multi-Airport Terminal Airspace. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Z.; Ryerson, M.S. A data-driven approach to modeling high-density terminal areas: A scenario analysis of the new Beijing, China airspace. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2017, 30, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Qu, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Ma, L.; Sun, Z. A Flight Slot Optimization Model for Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Airport Cluster Considering Capacity Fluctuation Factor. Aerospace 2025, 12, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. Optimization of Arrival Flight Sequencing and Flexible Trajectory Combination in Terminal Area. Master’s Thesis, Civil Aviation University of China, Tianjin, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, C.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Z. Research on Surface Scheduling Optimization for Departing Aircrafts under Large-Scale Delays. Aeronaut. Comput. Technol. 2020, 50, 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Cai, K.; Zhao, P. Departure Scheduling for Multi-airport System using Multi-agent Reinforcement Learning. In 2023 IEEE/AIAA 42nd Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zeng, W.; Wei, W.; Tan, X. A bilevel flight collaborative scheduling model with traffic scenario adaptation: An arrival prior perspective. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 161, 106431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, X.; Chu, F. A two-stage no-wait hybrid flow-shop model for the flight departure scheduling in a multi-airport system. In 2017 IEEE 14th International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control (ICNSC); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, A.P.; Clarke, B.; McClain, E. Discussion and comparison of metroplex-wide arrival scheduling algorithms. In Proceedings of the 10th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations (ATIO) Conference, AIAA, Fort Worth, TX, USA, 13–15 September 2010; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.L.; Clarke, J.P.B. Contrast and Comparison of Metroplex Operations An Air Traffic Management Study of Atlanta, Los Angeles, New York, and Miami. In Proceedings of the 9th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference (ATIO), AIAA, Hilton Head, SC, USA, 21–23 September 2009; p. 7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiropoulos, S.; Han, K.; Majumdar, A.; Ochieng, W. Robust identification of air traffic flow patterns in metroplex terminal areas under demand uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 75, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zografos, K.G.; Jiang, Y. A Bi-objective efficiency-fairness model for scheduling slots at congested airports. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 102, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamie, F.; Konstantinos, G.Z.; Kevin, D.G. A Slot-Scheduling Mechanism at Congested Airports that Incorporates Efficiency, Fairness, and Airline Preferences. Transp. Sci. 2019, 54, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paola, P.; Tatjana, B.; Lorenzo, C.; Raffaele, P. SOSTA: An effective model for the Simultaneous Optimisation of airport SloT Allocation. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2017, 99, 34–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuno, A.R.; Alexandre, J.; António, P.A. A Large-Scale Neighborhood Search Approach to Airport Slot Allocation. Transp. Sci. 2019, 53, 1772–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Balakrishnan, H. A comparison of two optimization approaches for airport taxiway and runway scheduling. In 2012 IEEE/AIAA 31st Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC); IEEE: Williamsburg, VA, USA, 2012; Volume 4E1, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, J.A.D.; Burke, E.K.; Ravizza, S. The Airport Ground Movement Problem: Past and Current Research and Future Directions. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Research in Air Transportation (ICRAT), Budapest, Hungary, 1–4 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ravizza, S.; Atkin, J.A.D.; Burke, E.K. A more realistic approach for airport ground movement optimisation with stand holding. J. Sched. 2014, 17, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlic, U.; Brownlee, A.E.I.; Burke, E.K. Heuristic Search for the Coupled Runway Sequencing and Taxiway Routing Problem. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 71, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, H.; Sherali, H.D.; Trani, A.A. Time-Dependent Network Assignment Strategy for Taxiway Routing at Airports. ransp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2002, 1788, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, Á.G. Airport management: Taxi planning. Ann. Oper. Res. 2006, 143, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeltink, J.W.; Soomer, M.J.; De-Waal, P.R. An optimisation model for airport taxi scheduling. In Proceedings of the INFORMS Annual Meeting, Denver, CO, USA, 24–27 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Deau, R.; Gotteland, J.B.; Durand, N. Airport surface management and runway scheduling. In Proceedings of the 8th USA/Europe Air Traffic Management R&D Seminar, Napa, CA, USA, 29 June–2 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eun, Y.; Jeon, D.; Lee, H. Optimization of airport surface traffic: A case-study of Incheon International Airport. In Proceedings of the 17th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference, AIAA, Denver, CO, USA, 5–9 June 2017; p. 4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simaiakis, I.; Khadilkar, P.; Balakrishnan, H. Demonstration of reduced airport congestion through pushback rate control. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2014, 66, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, G.; Wu, Y.; Luo, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. A Two-Stage Optimization Method for Multi-Runway Departure Sequencing Based on Continuous-Time Markov Chain. Aerospace 2025, 12, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simaiakis, I.; Balakrishnan, H. Impact of Congestion on Taxi Times, Fuel Burn, and Emissions at Major Airports. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2010, 2184, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadilkar, H.; Balakrishnan, H. Optimal Control of Airport Operations with Gate Capacity Constraints. In 2013 European Control Conference (ECC); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, J. Dynamic departure pushback control at airports: Part A—Linear penalty-based algorithms and policies. Nav. Res. Logist. 2024, 71, 960–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, J.Y. Finding the K Shortest Loopless Paths in a Network. Manag. Sci. 1971, 17, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.