Abstract

Accurate prediction of network-wide delay is crucial for air traffic management and passenger service. However, the inherent complexity of large-scale air traffic networks, with their dense interconnectivity and multi-dimensional operational dynamics such as flight connectivity, makes this task highly challenging. While Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) offer a promising framework, prevailing models are constrained by a “node → edge → node” representation paradigm, which fails to preserve the high-fidelity, edge-centric operational data that encodes delay propagation paths. To overcome this limitation, we propose a novel edge-based GNN. Our approach begins with a flight-connectivity-informed delay characterization, introducing delay width and delay strength as core metrics. The model implements an “edge → node” message-passing mechanism that explicitly encodes inbound and outbound flights, enabling direct learning of delay diffusion dynamics along air routes. Extensive experiments on real-world datasets demonstrate that our method outperforms state-of-the-art benchmarks, achieving the lowest RMSE, MAE, and MSE. A layered performance analysis reveals a key strength: the model delivers superior accuracy at major hub airports—which are critical to network performance—while maintaining robust precision at small-to-medium-sized airports. This balanced capability underscores the model’s practical utility and its enhanced capacity to capture the essential spatial–temporal dependencies governing delay propagation across diverse airport tiers.

1. Introduction

The global air traffic network has evolved into an exceptionally large and structurally complex system. Focusing on mainland China, the network spans nine Flight Information Regions (FIRs), covering a total area exceeding 10 million square kilometers. This infrastructure encompasses over 236 commercial airports and more than 6800 direct domestic air routes. Collectively, this system facilitates an average of over 15,000 daily flight operations. Notably, in 2019 alone, more than 845,900 flights experienced delays [1]. This scale of disruption underscores a critical operational challenge and highlights that accurate network-wide delay prediction is a fundamental prerequisite for developing effective mitigation strategies.

The methodology for flight delay prediction has evolved from rudimentary statistical models [2,3] to increasingly sophisticated machine learning and deep learning models. Accordingly, research on flight delays can be categorized into three distinct levels: flight-level delay [4,5,6,7,8,9], airport-level delay [9,10,11,12,13,14] and network-wide delay.

Network delay prediction requires capturing the spatial–temporal propagation, a task for which deep learning is well-suited [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. These models achieve this by integrating previous states (e.g., delay, traffic flow, weather) from nodes (airports) or edges (air routes) to learn the underlying complex nonlinear relationships.

Graph Convolution Networks (GCNs) [16,17,18,19,20,21] have been predominantly employed to model the spatial delay dependencies inherent to the network. However, despite their effectiveness in capturing certain spatial–temporal patterns among airports, current GCN-based delay prediction methods are constrained by two primary limitations:

- (1)

- Ineffective Representation of Edge-Based Traffic Flow: The prevailing “node → edge → node” paradigm necessitates aggregating edge-centric flight records into node features, which inherently obscures credible flow paths of air traffic. As these paths are critical drivers of delay propagation, their loss directly undermines model prediction accuracy.

- (2)

- Inadequate Modeling of Directionality in Traffic and Delays: Existing methods fail to adequately capture the strong directionality inherent in air traffic flows and network delays, which exhibit significant asymmetry even for identical airport pairs. This shortcoming arises since the underlying cause—the specific flight connectivity patterns sustained by individual aircraft—remains unrepresented in current graph formulations.

To address these limitations, this paper proposes a novel edge-based Graph Neural Network (GNN) framework for network-wide flight delay prediction. The core of our approach is a dual-metric delay characterization—delay width and delay strength—derived from flight connectivity, which formally reframes the prediction task as a graph-structured spatial–temporal relation extraction problem. The proposed model implements an “edge → node” message-passing mechanism that explicitly encodes inbound and outbound flights, air traffic flow paths, and aircraft-based connectivity, thereby preserving essential directional and operational fidelity.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews background and related work in network delay prediction. Section 3 characterizes network delay through flight connectivity analysis. Section 4 formulates the network-wide delay prediction problem and details the corresponding network construction methodology. Section 5 presents the architecture and learning process of the proposed edge-based GNN framework. Section 6 reports experimental evaluations on real-world datasets. Section 7 concludes the paper with a summary and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

Network-wide flight delay prediction fundamentally involves modeling the complex spatial–temporal dependencies inherent in air traffic networks. To capture these intricate, nonlinear relationships, deep learning has become the predominant approach. Two primary paradigms have emerged: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). While CNNs are adept at processing grid-like data and have been applied to learn spatial patterns from airport-grid representations [15], they are fundamentally limited by the non-Euclidean, heterogeneous topology of air traffic networks. This structural mismatch hinders their ability to model the preferential connections and dynamic interactions between airports effectively.

Consequently, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as the more natural and powerful framework for this domain, as they are explicitly designed to operate on graph-structured data [16,17,18,19,20]. Recent advances demonstrate GNNs’ superior capability in capturing network topology. Bao et al. [16] proposed AG2S-Net for predicting network-wide departure and arrival delay predict the multi-step-ahead hourly departure and arrival delay of the entire network. The model includes a Graph Convolutional Neural Network that can uncover hidden heterogeneous correlations on network-structured data, and a bi-LSTM neural network that can capture temporal dependencies in two directions. Cai et al. [17] proposed a deep learning approach for airport network delay prediction. They explore spatial interactions hidden in airport networks via an adaptive graph convolutional block and mine the time-varying patterns of delay by a temporal convolutional block. Cai et al. [18] proposed a geographical and operational graph convolutional network for airport network delay prediction. It improves node features representation ability with operational and geographical spatial–temporal interactions in the network. Graph convolutional network-based operational aggregator and geographical aggregator are designed to extract global operational information and similarities among spatially close airports separately. Wu et al. [19] proposed a novel space–time-separable graph convolutional network for network-wide delay prediction. It utilizes a multi-graph convolution model that considers both geographic proximity and airline schedules to reveal spatial correlation. And it employs a multi-head self-attention mechanism for temporal dependencies in delay time series. Mamdouh et al. [20] proposed an “attention-based Bidirectional long short-term memory” integrated network for network delay prediction. The Bidirectional LSTM model extracts the spatial and temporal dependencies of network delay with weather features. The “attention mechanism” has been proposed to enable the model to discover significant discriminating features that contribute to delay categorization. Shen et al. [21] developed a hybrid federated deep learning model, which employs a diffusion graph convolutional network and a residual gated recurrent unit to capture the complex spatial and temporal delay dependencies within the airport network.

Despite these significant advancements, a critical analysis reveals two pervasive limitations in the current GNN-based approaches that constrain their predictive fidelity: (1) Prevailing methodologies follow a “node → edge → node” paradigm. This requires aggregating fine-grained, edge-based flight records (the actual traffic flow) into node-level features prior to learning. Consequently, the credible traffic flow path, which gives birth to delay propagation, is obscured, ultimately limiting prediction accuracy. (2) Air traffic flow and delay propagation are inherently directional and asymmetric. This directional asymmetry is fundamentally driven by aircraft-specific flight connectivity patterns (e.g., an aircraft creating a causal link from its arrival to its subsequent departure). Current graph convolution operators fail to explicitly model this edge directionality and the consequent dynamic, rendering them unable to capture the spatial delay interactions.

Therefore, a clear research gap exists: The development of a graph learning framework that can directly utilize edge-based operational data to preserve authentic traffic flow paths, while simultaneously explicitly modeling the directional dependencies and aircraft-induced flight connectivity that govern delay propagation. Addressing this gap is essential for achieving more accurate and explainable prediction of network delay.

3. Flight Delay

3.1. Flight Connectivity by the Same Aircraft

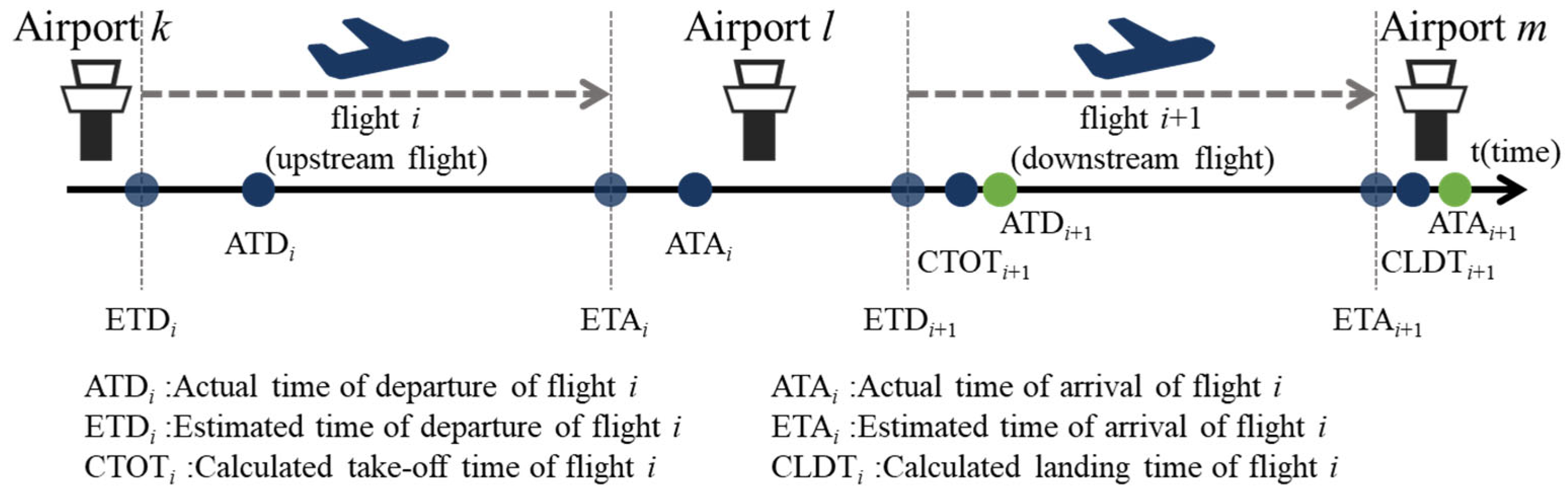

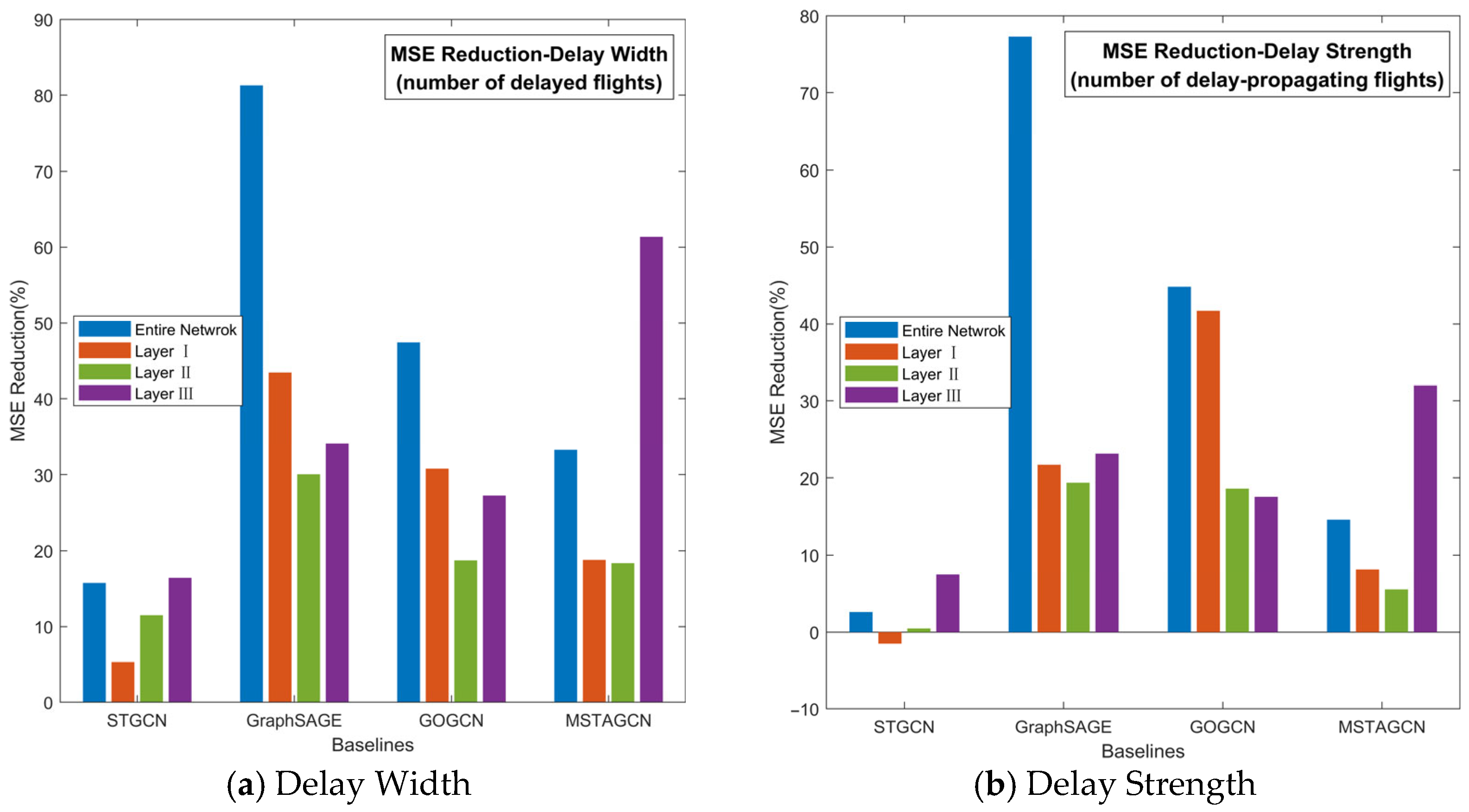

Each flight must submit a flight plan to the relevant air traffic service authority, typically one day prior, detailing the planned departure and arrival airports, estimated time of departure/arrival (ETD/ETA), planned air traffic route, and aircraft registration number. Upon execution, the actual time of departure/arrival (ATD/ATA) is recorded and updated, respectively. Together, the submitted flight plan and ATD/ATD constitute the flight record, which serves as the foundational data unit for air traffic service and flight surveillance. The temporal relationship among ETD, ETA, ATD, and ATA is schematically depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustration about upstream and downstream flight.

Modern aircraft utilization strategies often plan more than three flights per aircraft within a single day. Leveraging the unique aircraft registration number, it becomes feasible to establish temporal and operational linkages between consecutive flight segments, specifically, between an upstream flight (e.g., flight i, arriving at airport l) and its subsequent downstream flight (e.g., flight i + 1, departing from the same airport l), as shown in Figure 1.

With actual time of upstream flight and flight operation big data, it is possible to derive a more accurate estimation of the downstream flight’s calculated take-off/landing time (CTOT/CLDT). These calculations are formulated as follows:

where denotes the rotation time at airport l, which can be statistically derived from historical turnaround times of all the flights at airport l. represents the en-route time (ATA-ATD) from airport l to airport m, computed as the average airborne duration over a representative set of past flights on the same route segment.

Owing to their data-driven nature and incorporation of real-time operational feedback, CTOT/CLDT calculations typically exhibit closer alignment with actual operational outcomes (ATD/ATA) than the static, pre-filed ETD/ETA values usually submitted a day in advance. This dynamic calculation capability is essential for proactive delay propagation prediction in complex air traffic networks.

3.2. Delay Width and Delay Strength

A flight is classified as delayed if it fails to depart or arrive by the required time. When multiple delayed flights originate from airport l and propagate toward diverse destination airports, it is appropriate to assert that airport l has transmitted delay downstream, thereby broadening the delay across the network. However, such transmission does not necessarily imply that propagated delays are strong enough to be sustained at destination airports. Downstream flights may recover to normal with great effort. Consequently, delay width is conceptualized as a measure of delay range or scope, quantified by the number of delayed upstream flights, regardless of whether downstream flight i + 1 ultimately experiences a delay. This metric reflects the range or scope of delay rather than its strength or severity.

As illustrated in Figure 1, downstream flight i + 1 is particularly susceptible to the delay of upstream flight i since they share the same aircraft, due to tight operational coupling via air rotation constraints. To enhance flight schedule robustness, airlines have taken two preventative measures when making flight schedules. One is to add a time buffer into the required en-route time, yielding ATAi − ATDi < ETAi − ETDi. The other is to add a time buffer into the required rotation time, resulting in ATDi+1 − ATAi < ETDi+1 − ETAi. These time buffers are strategically designed to absorb delays from upstream flight i and prevent their cascading effects.

Nevertheless, when upstream delay is strong enough to exceed the capacity of these buffers, the disruption propagates to downstream flight i + 1. In such a case, upstream flight i and its downstream flight i + 1 are both delayed. Upstream flight i functions as a delay-propagating flight. Through the number of delay-propagating flights, it is possible to quantify delay strength across the network, which characterizes the propensity of delay to propagate, amplify or reproduce through successive operational linkages.

4. Problem Formulation and Network Construction

4.1. Problem Formulation

Network-wide flight delay prediction is conventionally formulated as a spatial–temporal sequence prediction problem. Let denote the vector of flight delay at time step t, where N represents the number of airports in the network. The underlying air traffic system is modeled as a directed graph , where V denotes the set of nodes (airports), and represents the set of directed edges (air routes between airport pairs). At time step t, let graph attribute metrices, and , represent node-level and edge-level delay features, respectively, where p and q denote dimensions of node and edge attributes, and is the edge size.

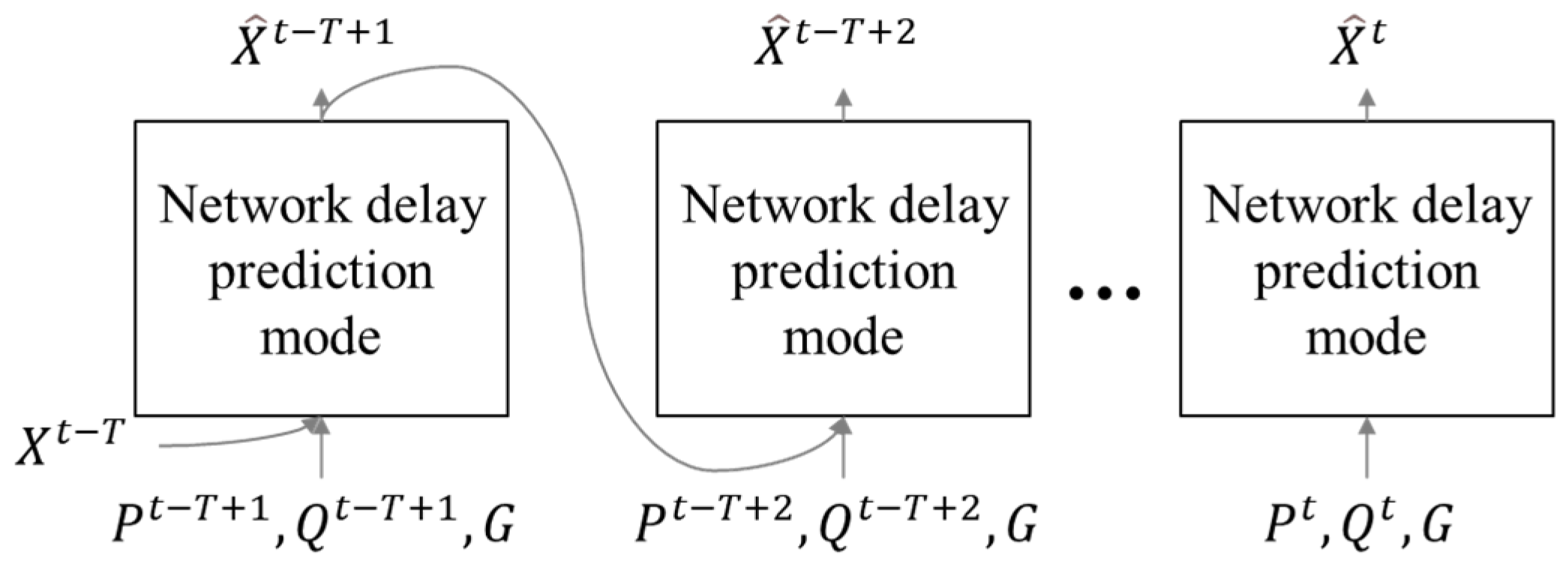

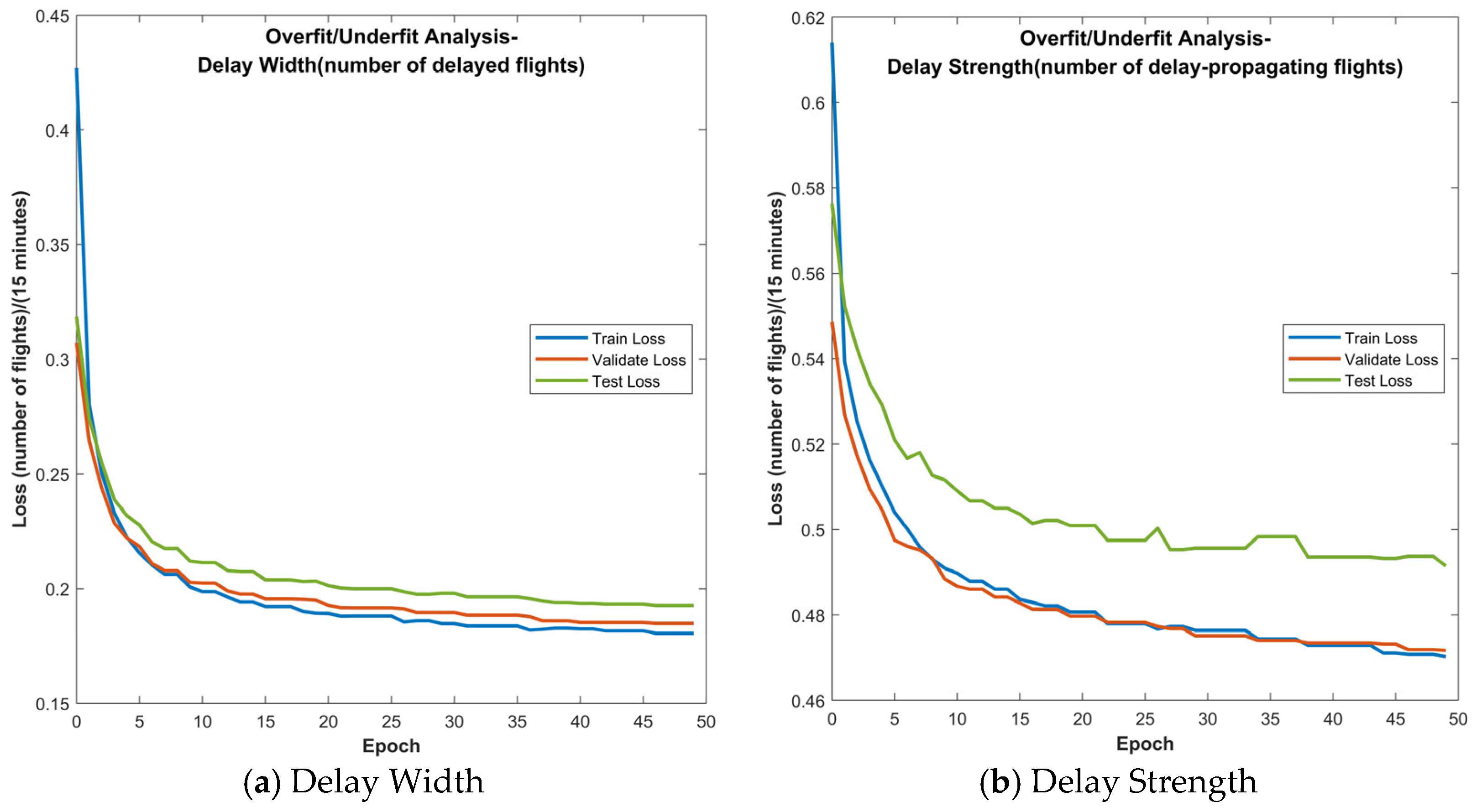

Formally, given the historical observations up to time t, the model takes as inputs: predicted delay vector from the previous time step, , sequence of node and edge attribute matrices over the past T time steps, and , graph structure G. The delay prediction task is thus formed as a mapping:

where denotes the learnable spatial–temporal predicting model parameterized by Θ.

As illustrated in Figure 2, this is implemented through an iterative application of the delay prediction model, denoted as in Equations (2) and (3), over T consecutive time steps. In the absence of prior predictions (e.g., at initialization when t = 0), the ground-truth delay vector is used as the initial input to bootstrap the prediction process.

Figure 2.

Illustration of delay prediction model process.

4.2. Network Construction by Flight Connectivity

Within each departure–arrival airport pair, multiple flights are typically planned. However, only some of them may experience delays. Based on the departure–arrival airport pair in flight records, we construct a directional airport network, where nodes represent airports and directed edges correspond to flight connections between them.

In addition to the departure–arrival airport pairs, flight records contain ETD/ETA, aircraft registration number and the ATD/ATA. By integrating these attributes—particularly the aircraft registration number together with ETD/ETA and ATD/ATA—it becomes possible to identify planned delays from upstream flights. Such edge-centric, directional data provide highly reliable signals for detecting and predicting flight connectivity and delay propagations across the network, as downstream flights are strongly coupled to the punctuality of their upstream delays (see Figure 1). Consequently, we associate flight connectivity with our modeling framework via these edge-level features. The selected edge features are delineated as follows.

Planned traffic flow (): Let denote the set of all flights planned to fly from airport l to airport m during the time window (t − 1, t), as determined by their ETD/ETA. The planned traffic flow for pair lm during time window (t − 1, t) is then defined as the cardinality of this set, .

Planned upstream arrival delay time (): Planned upstream arrival delay time for airport pair lm during time window (t − 1, t) quantified the cumulative arrival delay time of all upstream flights in .

Planned upstream arrival delay flights (): Planned upstream arrival delay flights for airport pair lm during time window (t − 1, t) represents the count of flights in who arrives late.

Rotation time (): Rotation time of airport l pertains to the statistical analysis of the actual rotation time of all executed flights in airport l, categorized by aircraft type.

En route time (): En route time for airport pair lm represents the statistical analysis of the actual en route time of all executed flights from airport l to airport m.

Collectively, these features constitute the edge attribute vector for the directed edge (l → m) at time t:

The constructed network and feature representation explicitly encodes both directional flow path and upstream punctuality at the airport pair level, thereby enabling the model to capture the directionality and flight connectivity of delay propagation.

5. Network Delay Prediction Model

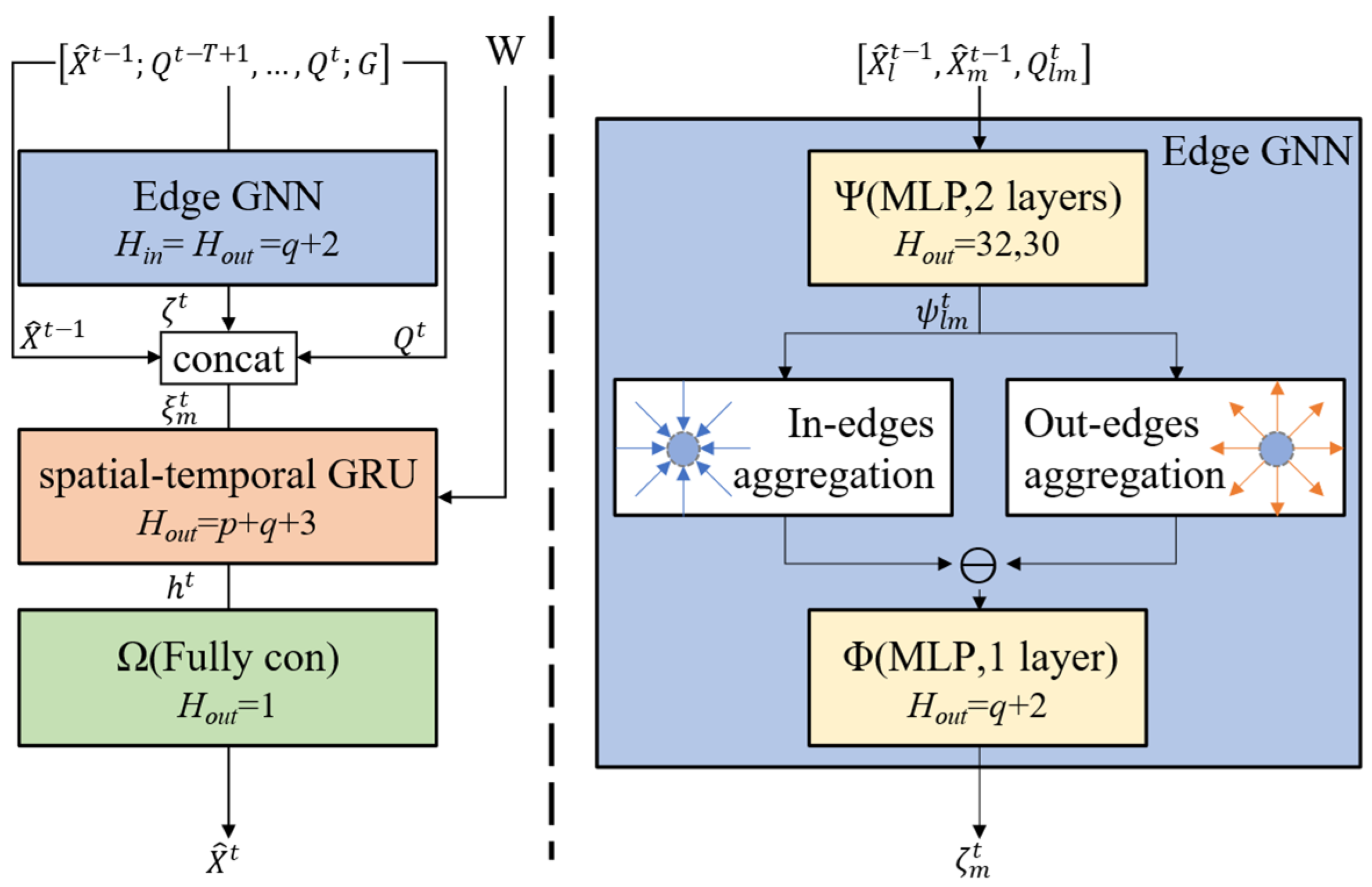

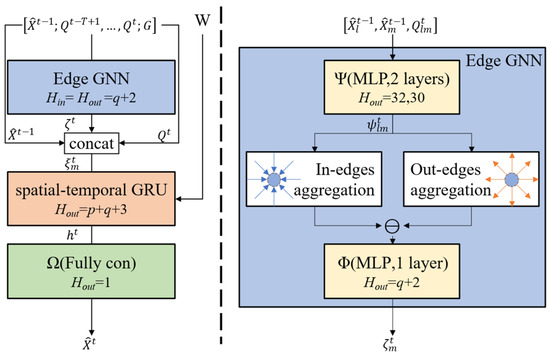

To effectively harness the credible and directional delay propagation path embedded in edge-centric flight records, we adopt an “edge → node” representation paradigm and propose an edge-based Graph Neural Network architecture for network-wide delay prediction. As illustrated in Figure 3, the proposed model comprises two core components. The blue block in Figure 3 is an edge-aware GNN module, designed to capture horizontal transmission of delays across the air traffic network via links and information to neighboring airports and iteratively refining node representations. The red block in Figure 3 is a spatial–temporal GRU, applied subsequent to GNN updates to model delay’s temporal accumulation and diffusion.

Figure 3.

Network delay prediction model architecture.

Following the “edge → node” message passing paradigm, the edge-aware GNN models learns latent representations through iteratively aggregating neighboring edge information on the graph. This recursive update mechanism is formally expressed in Equations (5)–(8), where and denote differentiable transformation functions that govern message construction and node updates, respectively. At each time step t, the representation of edge (l, m), denoted as in Equation (6), is initialized by concatenating the previously predicted delay states, and , with its current edge attribute vector in Section 4.2.

It is important to note that, under our formulation, both edge attributes and learned edge representation are direction-aware, preserving the inherent asymmetry of inbound flights and outbound flights. This directional encoding enables an explicit quantification of asymmetric influence between origin and destination airports. Specifically, for a given airport m, the delay diffusion from its neighbor l is approximated by the difference between the incoming influence () and outgoing influence (), as illustrated by the orange and blue directional lines in the blue block of Figure 3. The spatial correlation in Equation (7), associated with airport m at time step t, is then computed by aggregating these influence signals across all its neighbors.

In the proposed model, is implemented as a two-layer Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), while is designed as a single-layer MLP. The general forward pass of an MLP layer is defined by Equation (9), involving a learnable linear transformation parameterized by , followed by a non-linear activation function . Specifically, we employ the Sigmoid activation function, whose mathematical form is given in Equation (10). Through multiple rounds of recursive message passing, each node gradually incorporates information from increasingly distant airports of the network, thereby capturing long-range delay diffusion patterns.

To model the temporal evolution of network-wide delay, we integrate a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) as the fundamental recurrent building block, owing to its proven efficacy in capturing long-term temporal dependencies while mitigating vanishing gradient issues. At each time step t, the GRU cell receives the spatially enriched node representation in Equation (8) as input. This design ensures that the temporal dynamics modeled by GRU inherently account for concurrent spatial transmission effects. With the recursion of upstream delay or delay strength that is encoded in the edge representation, GRU takes flight connectivity into the message passing process. The complete update mechanism of our spatial–temporal GRU is formally described in Equations (11)–(14).

where , and W denote learnable parameters. The denotes the Sigmoid activation function (see Equation (10)), and represents the hyperbolic tangent activation function (defined in Equation (15)).

Based on the output of the proposed model, the ultimate delay prediction is then obtained via Equation (16).

where is defined as the linear transformation shown in Equation (17).

6. Experimental Results

In this section, we mainly introduce the dataset, experiment settings, evaluation metrics, baseline methods, and results of the proposed network delay prediction model.

6.1. Dataset

A real-world dataset is employed to evaluate the proposed model. The dataset is provided by the Air Traffic Management Bureau, Civil Aviation Administration of China. There are 1,061,250 recorded commercial domestic flights across 236 airports on the Chinese mainland during the period from 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2019. A total of 357,855 flights from January 2019 constitute the training set, 345,790 flights from February 2019 form the test set, and 357,605 flights from March 2019 serve as the validation set.

Each flight record includes the following operational attributes: mission date, flight number, aircraft type, aircraft registration number, planned/actual departure airport, planned/actual arrival airport, estimated/actual time of departure (ETD/ATD), and estimated/actual time of arrival (ETA/ATA). In accordance with standard air traffic management practice, a flight is classified as delayed if its actual departure delay is more than fifteen minutes (ATD − ETD > 15). The “fifteen minutes” threshold is widely adopted in air traffic operation, and the ATD/ATA/ETD/ETA are sourced directly from the flight records.

Given that the raw data are structured at the individual flight level, they undergo systematic statistical aggregation and transformation to align with the requirements of network delay prediction. Specifically, edge features , as formally defined in Section 4.2, are derived by summarizing relevant flight records within discrete temporal windows. The time horizon is discretized into 15 min intervals, such that each interval (t − 1, t) corresponds to a single time step in the spatial–temporal modeling framework.

6.2. Evaluation Metrics

The primary objective of this study is to predict delay width (number of delayed flights) and delay strength (number of delay-propagating flights) at each airport within the air traffic network over a given time horizon, with the aim of minimizing the discrepancy between predicted and observed delay at each time step. To this end, we adopt the Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the loss function for model training, defined at time step t, as follows:

where denote the predicted delay and ground truth of airport i for time step t, respectively. N represents the total number of airports in the network.

In addition to MSE, we employ two complementary evaluation metrics—Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE)—to provide a comprehensive assessment of the proposed method’s prediction performance.

6.3. Baseline Methods and Experiment Settings

To evaluate the performance of the proposed method, we select two widely adopted approaches for traffic flow prediction and two state-of-the-art methods specifically designed for flight delay prediction as baseline models.

- (1)

- STGCN [22]: A framework integrating graph and gated temporal convolutions within spatiotemporal blocks for traffic flow prediction.

- (2)

- GraphSAGE [23,24]: An inductive framework that generates node embeddings by sampling and aggregating features from local neighborhoods.

- (3)

- MSTAGCN [17]: Employs an adaptive graph convolutional block to learn time-evolving graph structures in airport networks, balancing accuracy and computational cost.

- (4)

- GOGCN [18]: A GCN-based spatiotemporal model that uses separate operational and geographical aggregators to enhance node representations for network-wide delay prediction, demonstrating superior accuracy.

Given that most domestic flights in mainland China are completed within three hours, the task is defined as predicting, for all airports, the number of delayed flights and delay-propagating flights over the next one-hour horizon. Predictions are based on spatial–temporal features aggregated from the preceding three hours and contextual information for the target hour.

The model is trained for 50 epochs (batch size = 32) by minimizing the MSE loss with the Adam optimizer, using an initial learning rate of 5 × 10−4 and a step decay of 1 × 10−4.

All experiments are conducted on a Windows 10 system (Python 3.11.6) with an Intel® Core™ i7-13700K CPU, 32 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU. The detailed configurations for all compared methods are provided below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Experimental settings.

Table 1.

Experimental settings.

| Method | Experimental Settings |

|---|---|

| STGCN | Kernel size of TimeBlock: 1 × 3 Out channels in each ST-Conv blocks: 64, 16, 64 |

| GraphSAGE | Number of message passing layers: 1 |

| MSTAGCN | Kernel size of temporal GCN: 1 × 5 Spatial and temporal GCN out channels in layer1: 64, 64 |

| GOGCN | Spatial GCN out channel of layer1 in OA: 32 |

| Proposed | Out channels of Ψ in Edge GNN: 32, 30 |

6.4. Results

- (1)

The one-hour-ahead delay width and strength prediction experiments (Table 2 and Table 3) yield two principal findings:

- (i)

- Superior Predictive Cccuracy: The proposed edge-based GNN achieves the best accuracy, minimizing all error metrics (train loss, MSE, RMSE, MAE). It outperforms the second-best model (STGCN) by up to 18.74% in delay width prediction and by up to 4.89% in delay strength prediction. This consistent superiority indicates the model’s enhanced capacity for capturing the complex spatiotemporal dynamics of network delays.

- (ii)

- Competitive Computational Efficiency: Although not the fastest in training, the proposed method maintains a highly competitive runtime. It strikes a practical balance between model complexity and prediction accuracy, demonstrating its viability for real-world deployment where both precision and operational efficiency are essential.

- (2)

- Prediction Accuracy Comparison in Layers: To reveal how the proposed method achieves such high prediction accuracy, we analyze prediction errors by layers [25], in which airports are categorized into three layers based on their influence on delay diffusion.

Table 2.

Overall performance comparison: delay width (number of delayed flights).

Table 2.

Overall performance comparison: delay width (number of delayed flights).

| Methods | Train Loss | MSE | RMSE | MAE | Train Epoch Execution Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STGCN | 0.244 ± 0.109 | 0.246 ± 0.08 | 0.268 ± 0.033 | 0.231 ± 0.031 | 32.864 ± 1.141 |

| GraphSAGE | 1.514 ± 3.885 | 1.108 ± 1.883 | 0.510 ± 0.312 | 0.447 ± 0.267 | 5.690 ± 0.407 |

| GOGOCN | 0.411 ± 0.332 | 0.394 ± 0.239 | 0.335 ± 0.106 | 0.292 ± 0.108 | 22.651 ± 0.529 |

| MSTAGCN | 0.302 ± 0.031 | 0.311 ± 0.020 | 0.446 ± 0.007 | 0.421 ± 0.007 | 35.566 ± 4.049 |

| Proposed | 0.198 ± 0.038 | 0.207 ± 0.023 | 0.234 ± 0.011 | 0.197 ± 0.009 | 24.714 ± 0.408 |

Table 3.

Overall performance comparison: delay strength (number of delay-propagating flights).

Table 3.

Overall performance comparison: delay strength (number of delay-propagating flights).

| Methods | Train Loss | MSE | RMSE | MAE | Train Epoch Execution Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STGCN | 0.511 ± 0.077 | 0.518 ± 0.052 | 0.344 ± 0.03 | 0.287 ± 0.029 | 30.563 ± 1.826 |

| GraphSAGE | 3.641 ± 13.346 | 2.22 ± 5.557 | 0.709 ± 0.745 | 0.578 ± 0.539 | 5.601 ± 0.36 |

| GOGOCN | 0.969 ± 0.422 | 0.914 ± 0.09 | 0.488 ± 0.049 | 0.419 ± 0.045 | 19.858 ± 0.242 |

| MSTAGCN | 0.58 ± 0.033 | 0.591 ± 0.017 | 0.503 ± 0.005 | 0.455 ± 0.004 | 66.282 ± 1.208 |

| Proposed | 0.486 ± 0.023 | 0.505 ± 0.016 | 0.332 ± 0.006 | 0.274 ± 0.005 | 21.317 ± 0.386 |

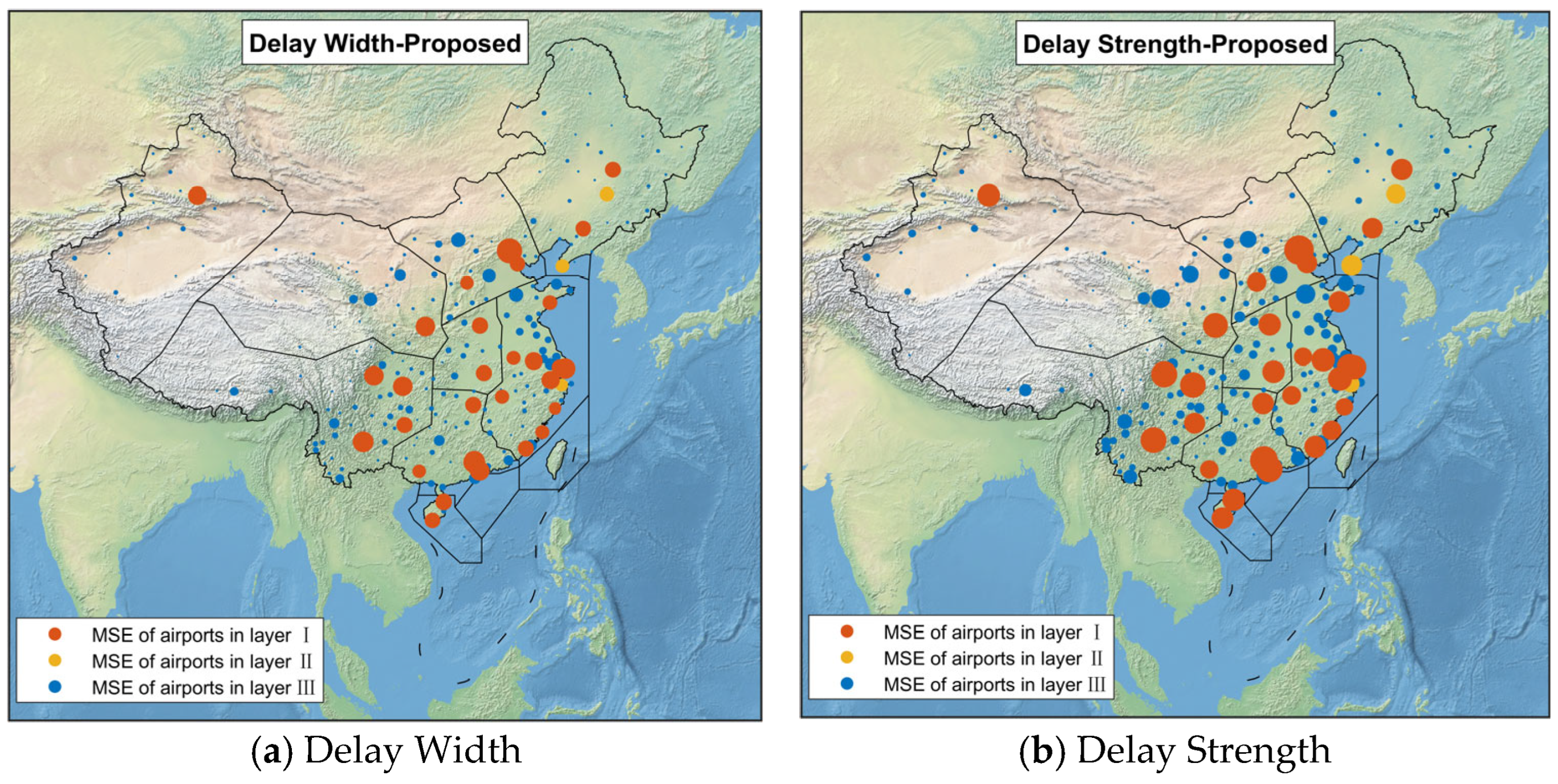

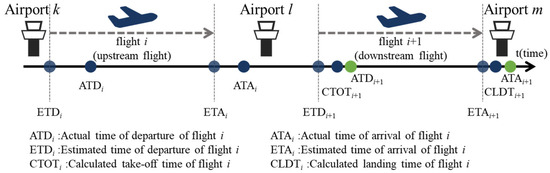

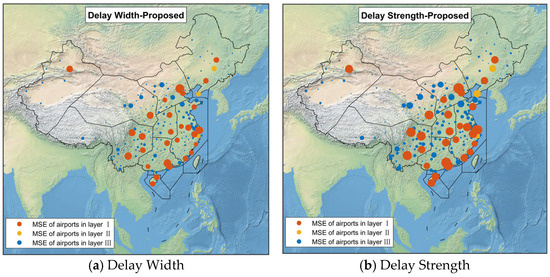

Layer I encompasses 29 major airports that play a pivotal role in governing delay propagation within the network. Layer III includes 204 airports, predominantly small–medium-sized, which exert minimal influence on network delay diffusion. Layer II comprises the remaining three airports. Figure 4 illustrates the airport MSE of the proposed method in the delay width and delay strength prediction experiment, where each node’s size corresponds to the MSE magnitude of the airport.

Figure 4.

Airport MSE of proposed method.

The detailed prediction errors across three layers in the delay width prediction experiment are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Prediction errors of 3-layer-delay width (number of delayed flights).

In the delay width experiment, the proposed method consistently outperforms the baseline models (STGCN, GraphSAGE, GOGCN, and MSTAGCN) on layer I. It achieves a relative reduction in mean MSE of 5.35%, 43.49%, 30.79%, and 18.79%, respectively. Corresponding improvements are observed in mean RMSE (3.42%, 22.43%, 14.80%, 12.06%) and mean MAE (3.89%, 24.36%, 15.78%, 13.82%). Notably, the standard deviations of all three error metrics are also reduced, indicating enhanced prediction stability.

This performance advantage is further amplified on layer II and layer III. On these layers, the proposed method delivers more substantial gains across all error metrics against each baseline. Most notably, on layer III, the improvements are most pronounced, especially over the MSTAGCN baseline, where reductions exceed 61% in mean MSE, 65% in RMSE, and 70% in MAE. Critically, across all three operational layers and every baseline model, the proposed approach consistently achieves lower standard deviations, which underscores its superior accuracy and greater robustness in diverse operational scenarios.

The detailed prediction errors of the three layers in the delay strength prediction experiment are illustrated in Table 5.

Table 5.

Prediction errors of 3-layer delay strength (number of delay-propagating flights).

On layer I, in terms of delay strength prediction, the proposed method outperforms GraphSAGE, GOGCN, and MSTAGCN across all three error metrics (MSE, RMSE, MAE), with improvements ranging from approximately 6% to 52%. However, it slightly underperforms the STGCN baseline by a marginal 0.69% to 1.51% on this layer. Notably, the standard deviations for all metrics are reduced, indicating improved stability.

This performance profile shifts markedly on layer II and layer III. The proposed method demonstrates broader and more substantial advantages. On layer II, it surpasses all four baseline models—including STGCN—in reducing MSE, RMSE, and MAE, with gains of up to 19.41% in MSE. On layer III, the superiority becomes unequivocal in most comparisons: it substantially outperforms GraphSAGE, GOGCN, and MSTAGCN, achieving reductions exceeding 23% in MSE and, in some cases, over 58% in MAE. Although it remains marginally behind STGCN (by 2.35% to 2.99%) on some layer III metrics, its performance against other baselines is dominant. Critically, across all layers and comparisons, the proposed method consistently achieves lower standard deviations, underscoring its robust and stable predictive capability for delay strength.

While all models exhibit lower errors on layer III—owing to its composition of smaller airports with simpler, lower air traffic flow—this result does not translate to effective network-wide prediction. The practical challenge lies in the core layers (I and II), which contain far fewer airports yet handle the majority of traffic and are responsible for most delay generation and propagation. Consequently, high accuracy on these two core layers is essential for meaningful system-level performance.

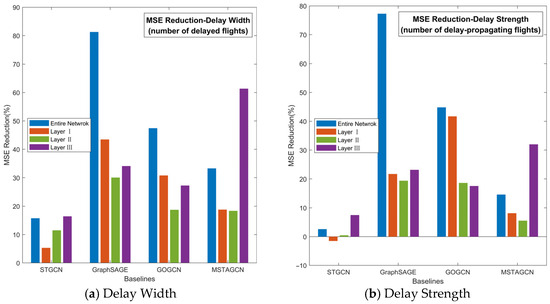

Figure 5 presents the layered MSE improvements of the proposed method over the four baseline models in both delay width and delay strength experiments.

Figure 5.

MSE improvement with baselines.

The results further reveal that performance on layer III contributes minimally to the aggregate improvement, whereas the prediction accuracy on layer I and layer II closely mirrors the global trend and constitutes the primary driver of overall gains.

Consequently, effective delay prediction requires a strategic emphasis on enhancing precision specifically for layer I and layer II, while maintaining acceptable (though not necessarily maximal) accuracy on layer III. Notably, both the proposed method and STGCN adopt such a prioritized approach, which underpins their superior and robust performance in network-wide delay prediction.

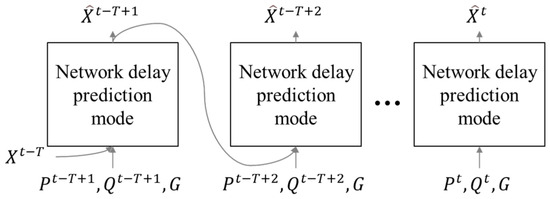

- (3)

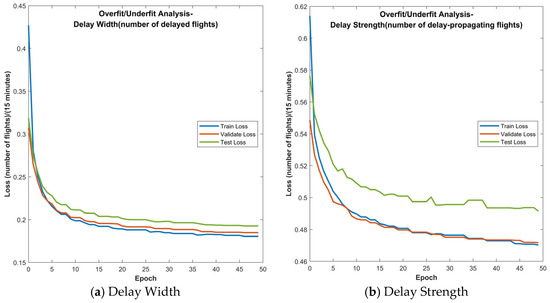

- Overfitting and Underfitting Analysis: Figure 6 presents the training, validation, and test loss curves of the proposed method in the delay width and delay strength prediction experiments, serving as an evaluation of its generalization performance.

Figure 6. Training, validation and test losses of proposed method.

Figure 6. Training, validation and test losses of proposed method.

As shown in Figure 6, the loss curves for both delay width and strength exhibit high consistency and stable convergence across training, validation, and test sets over 50 epochs, without significant oscillation or divergence. Given that the three data partitions are balanced in size and mutually exclusive, this tightly aligned convergence indicates minimal generalization gap and highly consistent model performance.

These observations confirm that the proposed model effectively mitigates both overfitting and underfitting. It thus demonstrates a robust capacity to capture the complex spatial–temporal dependencies of network delays while maintaining strong generalization to unseen data.

7. Conclusions

This study proposes a novel edge-based Graph Neural Network (GNN) framework for network-wide delay prediction. The framework leverages flight connectivity to construct a directed delay network, enabling an effective characterization of systemic delay propagation. At its core, the model adopts an “edge → node” representation paradigm, through which message-passing mechanisms naturally encode the relationships between inbound and outbound flights, as well as the actual paths of air traffic flow.

Experimental validation on real-world aviation datasets confirms the superior predictive accuracy of the proposed method over established baseline models. A layered performance analysis further reveals a key strength: the model achieves the highest precision at major hub airports characterized by high traffic flow and frequent delays, while concurrently maintaining robust accuracy at small-to-medium-sized airports. Its strong generalization capability is consistently supported by comparable loss metrics across the training, validation, and test sets.

The proposed →-centric architecture outlines several promising directions for future research. First, it readily accommodates the integration of dynamic en-route contextual factors—such as en-route weather and air traffic controller workload—which are critical to delay propagation. Second, capturing spatial–temporal dependencies within the network can be enhanced by incorporating more sophisticated graph operators (e.g., attention mechanisms or higher-order message passing), thereby potentially improving both model robustness and accuracy. Finally, the underlying methodology is adaptable to other large-scale transportation or infrastructure networks that require system-wide performance forecasting.

Author Contributions

Z.T.: Conceptualization, Methodology, and Writing—Original Draft. Z.N.: Writing—Review and Editing. X.C.: Data Curation. S.H.: Validation. X.Z.: Supervision and Funding Acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2024YFB2605201, and the Open Project of Sichuan Provincial Engineering Technology Research Center for Civil Aviation Flight Technology and Safety, grant number GY2024-03B.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is provided by the Air Traffic Management Bureau. CAAC. The dataset presented in this article is not readily available because the authors have no permission to share it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Civil Aviation Administration of China, Production Statistics of Chinese Civil Aviation in 2019. 2020. Available online: http://www.caac.gov.cn/XXGK/XXGK/TJSJ/202006/t20200605_202977.html (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Tu, Y.; Ball, M.O.; Jank, W.S. Estimating flight departure delay distributions—A statistical approach with long-term trend and short-term pattern. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2008, 103, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, N.; Zou, B. Modeling flight delay propagation: A new analytical-econometric approach. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2016, 93, 520–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcastro, L.; Marozzo, F.; Talia, D.; Trunfio, P. Using scalable data mining for predicting flight delays. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2016, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Yu, B.; Hao, M.; Wang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Z. A novel hybrid method for flight departure delay prediction using Random Forest Regression and Maximal Information Coefficient. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 106822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Jing, R.; Dong, Z.S. Flight delay prediction with priority information of weather and non-weather features. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 7149–7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, G.; Liu, F.; Sun, J.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, D. Flight delay prediction based on aviation big data and machine learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, E. Prediction of flight departure delays caused by weather conditions adopting data-driven approaches. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Guo, Z.; Asian, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, G. Flight delay prediction for commercial air transport: A deep learning approach. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 125, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, M.F.; Kamel, S.R.; Chabok, S.J.M.; Kheyrandish, M. Flight delay prediction based on deep learning and Levenberg-Marquart algorithm. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.A.; Ma, H.-L.; Chung, S.-H.; Wen, X. Hierarchical integrated machine learning model for predicting flight departure delays and duration in series. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 129, 103225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Prabowo, A.; Zhao, S.; Koniusz, P.; Salim, F.D. Predicting flight delay with spatio-temporal trajectory convolutional network and airport situational awareness map. Neurocomputing 2022, 472, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Hu, J.; Qiu, G.; Li, J.; Qu, F. Departure delay prediction and analysis based on node sequence data of ground support services for transit flights. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 153, 104217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisandu, D.B.; Moulitsas, I. Prediction of flight delay using deep operator network with gradient-mayfly optimisation algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 247, 123306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guan, X.; Liu, J. A CNN-LSTM framework for flight delay prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 224, 120287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Yang, Z.; Zeng, W.; Li, Z.; Guo, J. Graph to sequence learning with attention mechanism for network-wide multi-step-ahead flight delay prediction. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 130, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Li, Y.; Fang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, H.; Song, L. A deep learning approach for flight delay prediction through time-evolving graphs. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 11397–11407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Zhu, Y.; Fang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, C. A geographical and operational deep graph convolutional approach for flight delay prediction. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, H.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, L. Spatiotemporal propagation learning for network-wide flight delay prediction. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamdouh, M.; Ezzat, M.; Hefny, H. Improving flight delays prediction by developing attention-based bidirectional LSTM network. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Chen, J.; Yan, R.; Wang, Y. A spatial–temporal model for network-wide flight delay prediction based on federated learning. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 154, 111380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Yin, H.; Zhu, Z. Spatio-temporal graph convolutional networks: A deep learning framework for traffic forecasting. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1709.04875. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, W.L.; Ying, R.; Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1025–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Jiang, A.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Sun, J. GraphSAGE-based dynamic spatial–temporal graph convolutional network for traffic prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 11210–11224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhu, X.; Pan, W.; Han, S.; Gong, T. Research on the multilayer structure of flight delay in China air traffic network. Physica A 2023, 609, 128309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.