Abstract

Lunar dust exhibits exceptionally strong adhesion, abrasiveness, and electrostatic charging due to long-term exposure to extreme temperature cycling (−183 °C to 127 °C), high vacuum, and intense radiation. With the rapid advancement of global lunar exploration programs and the planned construction of lunar bases, lunar dust has become a critical threat to exploration equipment, spacesuits, and spacecraft sealing systems. This paper systematically reviews recent progress in lunar dust mitigation technologies from the perspective of engineering application requirements. Key micro-mechanism factors governing dust adhesion and removal efficiency are analyzed, and the protection mechanisms and application scenarios of traditional lunar dust mitigation technologies are comprehensively discussed, including both active and passive approaches. Active protection technologies generally provide effective dust removal but suffer from high energy consumption, whereas passive strategies can reduce dust adhesion but face challenges in mitigating dynamic dust accumulation. To overcome these limitations, recent studies have increasingly focused on active–passive synergistic strategies that integrate surface modification with dynamic dust removal. Such approaches enable improved efficiency and adaptability by combining long-term dust resistance with real-time removal capability. Based on the latest research advances, this paper further proposes an integrated technical framework for the engineering design of efficient lunar dust protection.

1. Introduction

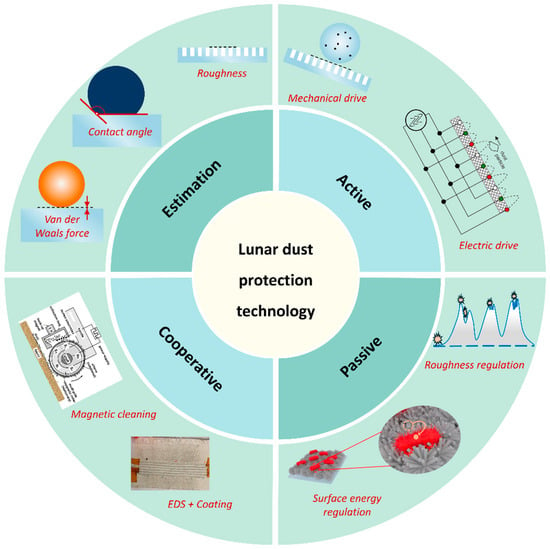

As the most significant milestone in the realm of deep space exploration, the technical challenges posed by lunar exploration and base construction have transitioned from an initial focus on transportation breakthroughs to the issue of extreme environmental adaptability [1,2,3,4]. The presence of lunar dust on the lunar surface has been shown to result in the formation of a distinctive secondary weathering layer [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Lunar dust exhibits a complex and diverse composition, dominated by silicate minerals and containing metallic iron–nickel alloys and meteoric iron sulfides. Its formation is closely related to the evolution of the Moon: the initial stage of magma ocean differentiated crystallization, giving birth to plagioclase feldspar, pyroxene, and other primary mineral particles; after a sustained impact, rocks were crushed and melted and both minerals were crushed into debris, became molten material, and rapidly cooled into vitreous or tiny crystalline particles; finally, the long-term weathering of space, the synergistic effect of ultra-high vacuum, extreme temperature alternation, and cosmic radiation, and the formation of unique surface chemical activity and interfacial adhesion properties [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The Apollo missions offer a pertinent illustration of the challenges posed by dust particles with diameters smaller than 20 μm [18,19]. In this instance, spacesuit components experienced malfunctions, and the efficiency of the solar panels diminished due to the adhesive and abrasive properties of these particles [20,21]. Furthermore, these particles have the capacity to penetrate traditional sealing systems, thereby causing irreversible damage to key equipment such as spaceship fittings, optics, and solar panels. This phenomenon can be attributed to the accumulation of surface charge, which hinders the reliable and sustained operation of lunar surface apparatus over extended periods [22,23,24,25]. It is evident that the accumulation of charge on the lunar surface has become a significant impediment to the long-term stable operation of lunar surface equipment [26]. The present paper focuses on lunar dust mitigation technologies, covering a variety of strategies and methods (Figure 1). The evaluation of the lunar dust protection effect is conducted through the measurement of parameters such as contact angle, roughness, and van der Waals force [27,28,29]. In terms of protection strategies, active protection technology employs mechanical and electric drives to detach lunar dust by dynamic means [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]; passive protection technology [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], in contrast, regulates surface energy and roughness to inhibit lunar dust adhesion. The technology integrates magnetic cleaning and energy spectrum analysis with coatings in order to enhance the protection effect. It is evident that these divergent protection techniques are not isolated, but rather, they have the capacity to collaborate in order to formulate multi-dimensional concepts for the development of an effective lunar dust protection system. Subsequently, examples of outstanding protection based on these techniques will be presented. Finally, this review will discuss the current challenges and future prospects of lunar dust protection technologies [45,46].

Figure 1.

Lunar dust protection strategies and methods.

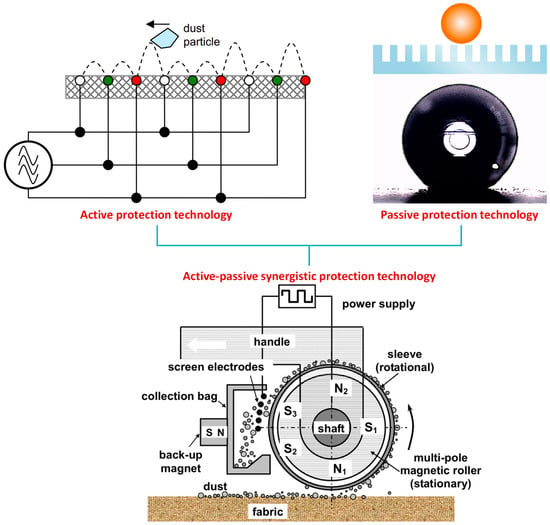

Classical lunar dust protection techniques can be categorized into two main types, active and passive protection; however, both approaches exhibit evident physical limitations in practical engineering applications. Active protection technology primarily relies on dynamic dust removal mechanisms, such as mechanical dust removal and electrostatic repulsion, which have been shown to be effective in addressing the issue of dust accumulation on the lunar surface [47]. Nevertheless, the elevated energy consumption and system complexity of the latter render it challenging to satisfy the requirements for long-term operation of the lunar base. Passive protection technology is a method of regulating the surface energy and roughness of the interface through surface engineering methods, such as low-adhesion coatings and micro- and nanostructure design, but it has obvious deficiencies in coping with the dynamic dust caused by lunar activities. This is particularly pertinent when considering the synergistic effects of the charged nature of lunar dust and extreme temperature variations [48,49,50,51,52,53]; a single protection strategy often fails to balance long-term protection effectiveness and dynamic responsiveness. In order to address the aforementioned technical challenges, scholars have proposed an innovative active–passive synergistic protection strategy [54,55], which integrates multi-scale surface modification with an intelligent dust removal system to construct a composite protection system with environmental adaptability. The strategy is founded on the principle of circumventing the unidimensional optimization approach of conventional protection technology. The implementation of a superhydrophobic surface design is intended to impede initial adhesion at the microscopic level, while the integration of an active dust removal module at the macroscopic level is aimed at ensuring the long-term maintenance of the system. As demonstrated in Figure 2, the technologies employed in active, passive, and synergistic active–passive protection are typically categorized in this manner.

Figure 2.

Lunar dust protection technology [30,56]. Copyright 2009, Elsevier. Copyright 2012 American Society of Civil Engineers.

This paper undertakes a systematic review of recent progress in this field from a system-level engineering perspective, with emphasis on deploy ability, reliability, and long-term operation under lunar surface conditions. The primary focus of this study is the micromechanical mechanism of lunar dust attachment, with the establishment of a quantitative evaluation system of lunar dust protection efficiency being a secondary objective. The system introduces key parameters such as van der Waals force, hydrophobic angle, rolling angle, lunar dust distribution area ratio, mass ratio, and so on [57,58]. The subsequent sections of this paper focus on active/passive protection techniques of space dust and systematically evaluate mechanical dust removal, electrostatic repulsion, and other active techniques. In conclusion, this paper elaborates on the innovative architecture of a synergistic active–passive protection strategy, which comprises an optimized surface interface design integrated with an intelligent dust removal system. The objective of this combination is to deliver superior long-term dust protection and dynamic dust removal functionality. Although lunar dust passive protection technologies were explored in previous work [59], with the rapid development of lunar dust protection technologies and the continuous emergence of new research results, especially those related to engineering applications, this review delves into the latest developments in lunar dust protection technologies. It integrates various protection strategies (including active, passive, and active–passive synergistic approaches) and proposes a more systematic technical roadmap and design concepts. This review places particular emphasis on the advantages of synergistic active–passive protection, exploring how to enhance lunar dust protection through surface engineering, nanotechnology, and the integration of smart materials. This novel and comprehensive perspective has strong foresight and practical value. This review primarily focuses on lunar dust environments generated during spacecraft landing and early surface exposure, where dust is mobilized by descent engine plumes and directly impacts spacecraft systems and nearby infrastructure. The following studies, which represent the latest research in the field of lunar dust protection research, provide technical routes for the engineering of efficient lunar dust protection technologies.

2. Lunar Dust Hazards

In the annals of lunar exploration, the seemingly inconspicuous lunar dust on the lunar surface has emerged as a significant predicament, with profound ramifications for all facets of lunar exploration endeavors. A comprehensive understanding of the hazards posed by lunar dust is paramount to emphasizing the significance of lunar protection technology and to directing future research and development in this field.

2.1. Hazards to Lunar Exploration Equipment

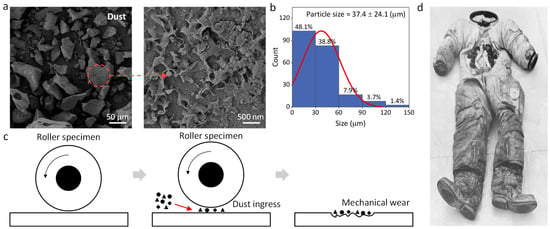

Lunar dust exhibits highly irregular morphological features at the micrometer scale (Figure 3a). The particles overall display a combination of angular, fragmented, and flaky structures, lacking the rounded edges commonly observed in Earth’s weathered environments. Enlarged SEM images reveal that the dust particles possess a highly textured surface, featuring numerous micro- and nanoscale protrusions, pores, and sharp edges. This multi-level roughness significantly increases the particles’ specific surface area, enhancing their mechanical interlocking and adhesion capabilities with solid surfaces. The particle size distribution of lunar dust spans a broad range, primarily concentrated in the tens of micrometers (Figure 3b), with an average diameter of 37.4 ± 24.1 μm. Fine particles smaller than 30 μm constitute nearly half of the total, while those below 60 μm dominate the distribution [60]. This multi-scale, fine particle-dominated size distribution implies that lunar dust readily deposits on macrostructures while also possessing the ability to infiltrate minute voids and penetrate complex internal structures.

Figure 3.

Lunar dust hazards. (a) SEM characterization of lunar dust and (b) particle size distribution [60]; Copyright 2026, Elsevier. (c) Mechanical wear schematic [61]; Copyright 2024, Elsevier. (d) Lunar dust-covered spacesuit [62]; Copyright 2017, Elsevier.

The threat of lunar dust to lunar exploration equipment is pervasive, with mechanical structures, optical systems, and power systems all potentially vulnerable. From a mechanical perspective, the first problem is material wear. To illustrate this point, consider the effect of dust particles on a system with rollers. It has been established that the rotation of the rollers serves to increase the friction between the dust and the structure, consequently leading to wear and tear on the mechanical structure [61] (Figure 3c). Furthermore, the effect of lunar dust particles of different sizes on material wear varies. Although the change in friction is negligible, smaller lunar dust particles—those smaller than 100μm—are more likely to infiltrate the microscopic gaps within the material. This phenomenon is believed to exacerbate the deterioration of the material’s internal structure, thereby expediting the wear process [63]. Ultimately, the fundamental components of the equipment will undergo gradual deterioration, thereby significantly impacting the stability and reliability of the mechanical structure.

Furthermore, mechanisms are also highly susceptible to clogging with lunar dust. The fine nature of lunar dust particles (with a size range from microns to millimeters) and their large specific surface area result in high adhesive properties. Consequently, these particles accumulate in key moving parts, such as joints, gears, and bearings, when the equipment is in operation. The accumulation of a significant quantity of lunar dust can be likened to the introduction of numerous minute wedges between mechanical components, thereby substantially augmenting the friction between these elements and impeding the standard operation of the mechanical parts. This, in turn, results in a reduction in the operational precision of the equipment and a decline in efficiency. In more severe cases, the mechanical structure may become immobilized, rendering it completely inoperable. It is hypothesized that the mechanical failure of China’s Jade Rabbit lunar rover after its first lunar night was caused by obstruction from lunar dust [64]. This suggests that lunar dust may pose a serious threat to the proper functioning of mechanical structures [65].

Moreover, the presence of lunar dust has the capacity to impede the operational efficacy of lunar exploration apparatus by interfering with its energy supply [66]. Solar panels are considered to be a pivotal energy source for lunar exploration missions. However, the presence of lunar dust on the surface of the panels can impede sunlight transmission, thereby reducing the overall efficiency of the solar panels. As the amount of lunar dust accumulates, the problem of energy supply will become more and more serious, and the energy available for the equipment will be reduced, which will directly affect the endurance and operating hours of the equipment and may eventually prevent the equipment from operating normally due to the lack of energy.

2.2. Hazards to Spacesuits

Damage to spacesuits caused by lunar dust represents a direct threat to the lives of astronauts and the successful execution of missions [67]. The physical properties of lunar dust are characterized by the presence of impact-formed silicate glass, which serves to weld together soil particles to form agglomerates with complex morphologies. These agglomerates are distinguished by sharp, jagged edges [68]. During the Apollo missions, this phenomenon was observed in the spacesuits worn by astronauts (Figure 3d). The damage sustained by the suit fabrics was attributable to the abrasive effect of lunar dust. This form of abrasion must be considered as a process that is not merely a superficial loss of material. In order to understand the phenomenon, it is necessary to consider the sharp edges of the lunar dust, which persist in scraping the fabric. This results in the gradual destruction of the fiber structure and a consequent reduction in tensile strength [69].

2.3. Hazards to Spacecraft Sealing Systems

It is imperative to acknowledge the significance of spacecraft sealing systems in ensuring the stability of the internal environment of a spacecraft. The potential hazards posed by lunar dust cannot be underestimated. Lunar dust particles are smaller than 100 μm, enabling them to easily penetrate the seams and interfaces of sealed systems. As the spacecraft operates within the lunar environment, lunar dust accumulates in these areas, gradually destroying the integrity of the sealing structure. It is inevitable that, over time, the sealing performance will gradually deteriorate, resulting in gas leakage from the spacecraft and subsequent pressure imbalances. This will not only affect the normal operation of the equipment inside the spacecraft but may also pose a threat to the lives of the astronauts. For instance, in a low-pressure environment, the physiological functions of the human body are significantly impacted [70,71], which can potentially result in hazardous conditions such as decompression sickness.

Furthermore, it is postulated that the chemical properties of lunar dust may have an erosive effect on sealing materials [65]. This phenomenon can be attributed to the potential presence of corrosive substances in certain lunar dust particles. It is hypothesized that, upon prolonged contact with the sealing material, these particles may undergo chemical reactions that result in alterations to the properties of the sealing material, including hardening and embrittlement. The sealing effectiveness of the material is ultimately reduced, and the accumulation of lunar dust within the sealing system has the potential to disrupt its normal operation. This disruption can be seen, for example, in the opening and closing of the sealing door, thereby impairing the protective capability of the sealing system.

3. Evaluation of the Efficiency of Micro-Dust Control

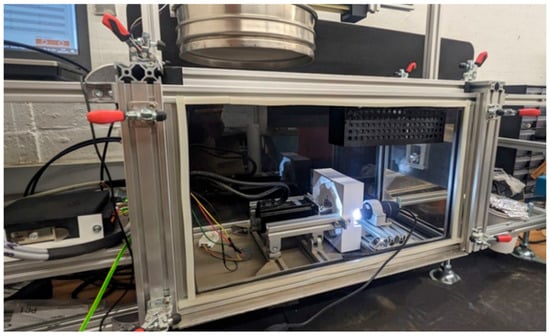

Given the significant differences between the lunar surface environment and Earth’s environment, it is necessary to establish a set of testing standards that can simulate lunar environmental conditions, primarily involving vacuum conditions, microgravity, extreme temperature fluctuations, radiation environments, and dust characteristics. The lunar surface is devoid of an atmosphere, existing in a high-vacuum state. The gravitational force on the surface is one-sixth that experienced on Earth, and the surface experiences extreme diurnal temperature variations. Additionally, the lunar surface is directly exposed to solar wind and cosmic rays. Furthermore, the particles of lunar dust are characterized by their minute size (less than 100 μm), sharpness, considerable adhesive properties, and abrasiveness. These characteristics pose a significant challenge in the full replication of their properties within an Earth-based environment. Whilst it is acknowledged that ground testing environments are unable to fully replicate lunar conditions, the construction of a low-fidelity environment has been demonstrated to ensure the reliability of test results (Figure 4). The environment is engineered to replicate the conditions of the lunar high-vacuum environment by meticulously controlling the pressure within the vacuum chamber [72,73]. It is designed to emulate the diurnal temperature variations and radiation effects experienced on the lunar surface by regulating the temperature and radiation intensity of the experimental environment. Additionally, it simulates the physical and chemical properties of lunar dust by selecting suitable lunar dust simulants and controlling their particle size distribution and chemical composition [73].

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of a low-fidelity test environment for ground testing [73]. Copyright 2025, Springer Nature.

By establishing and applying low-fidelity environments, lunar dust protection technologies can be effectively evaluated in Earth-based conditions. A reasonable transition between ground-based test environments and lunar environments will provide important references for the research and development of lunar dust protection technologies and offer critical technical support for future lunar surface missions.

3.1. Van Der Waals Forces

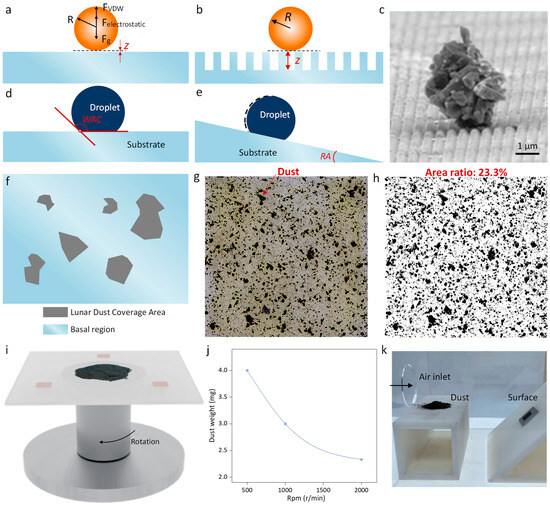

When exploring the mechanical influence mechanisms of dusting phenomena, van der Waals forces play a dominant role, while the effects of electrostatic forces, gravity, and surface tension are usually weaker in comparison. The detailed force distribution is shown in Figure 5a. The electrostatic force follows Coulomb’s law, , which depends on the charge distribution of particles and surfaces and is only manifested in a specific high-charge density, low-ion shielding environment, and, with the rise in environmental ionic strength, the shielding effect of ions on charge is enhanced and the effect of electrostatic force is prone to rapid attenuation. The gravitational force is described by , and the force value generated by gravity is much weaker than that generated by van der Waals force because of the extremely small micro-mass of dust particles at interfaces, suspension, and other behaviors related to dust thinning. For the dust removal-related interface, suspension, and other behaviors, the force value generated by gravity is much smaller than other dominant forces, and it is difficult to significantly change the particle movement and attachment trend. Surface tension originates from the unbalanced force of molecules on the surface of the liquid. For the dust removal process, if it involves the liquid–solid–gas interface, its role can be reflected by Young’s equation , but more often on superhydrophobic surfaces, solid particles are dominated by the dust removal process. For the dust removal process, which is dominated by solid particles, the direct influence on the force and detachment behavior of particles is limited. In general, van der Waals forces are the key determinants in the mechanical equilibrium and dynamics of the dust-trapping phenomenon.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of microscopic dust control efficiency. (a) Diagram showing the decomposition of force. (b) Schematic representation of van der Waals force action on surfaces with microstructures. (c) Microscopic image of particle aggregation [44]; Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. (d) Schematic representation of hydrophobicity angle definition. (e) Schematic representation of rolling angle definition. (f) Schematic representation of the lunar dust distribution area. (g) Diagram of the lunar dust distribution state. (h) Diagram of the degree of lunar dust coverage. (i) Dust protection efficiency test platform. (j) The effect of rotational speed on the amount of lunar dust shedding. (k) Evaluation of dust protection efficiency on inclined surfaces [60]; Copyright 2026, Elsevier.

The phenomenon of van der Waals forces is attributable to transient dipole and induced dipole interactions between molecules or atoms [74]. In the case of two objects in close proximity to each other, it is known that the electron distributions of both objects are known to shift, thus forming transient or induced dipoles. The interaction force between these dipoles is known as the van der Waals force. Despite the generally weak nature of van der Waals forces, they nevertheless exert a considerable influence at the microscopic level, particularly in the context of dust particle–interface interactions, where they predominate. In the context of dust-proof materials, the magnitude of the van der Waals force is directly proportional to the degree of adhesion of dust particles to the surface.

Van der Waals force can be regarded as a weak electrostatic interaction induced by transient dipoles between molecules, containing three types of orientation force, induced force, and dispersion force. (1) The orientation force is characterized by the electrostatic attraction between inherent dipoles of polar molecules. This force exerts a dominant influence on the adhesion behavior of strong polar substances, such as water molecules. In the field of dust control, if polar pollutants (e.g., hydroxyl-containing particles) are adsorbed on the surface of lunar dust, the orientation force will significantly enhance the bonding strength between the particles and the substrate. (2) Induced force: the interaction between polar and non-polar molecules that is induced by an electric field. For instance, the induced force has been shown to account for up to 30% or more of the adhesion force between the oxide layer (polar) on the surface of the metal substrate and the non-polar carbon dust particles. (3) The dispersion force is defined as the attractive force that is generated by the instantaneous dipole coupling of molecules. It has been determined that this force accounts for between 70% and 90% of the total contribution of van der Waals forces. This phenomenon is especially pronounced in the context of non-polar lunar dust (e.g., silicate particles) and low-surface energy coating adhesion, where dispersion force emerges as the predominant form of action.

The van der Waals force is typically expressed as [75]

In this Equation (1), denotes the Hamaker constant, which represents the magnitude of van der Waals interactions between materials, represents the radius of the particle, and is the spacing between the particle and the planar substrate. The Hamaker constant can be calculated using Lifshitz’s theory [76], which accounts for the dielectric properties and refractive indices of the interacting materials (e.g., lunar dust particles and the substrate) and the medium (vacuum for lunar environment). For spherical particles interacting with a planar surface, the Lifshitz-based calculation involves integrating electromagnetic fluctuations over all wavelengths, yielding a material-specific constant. For the interaction between two spherical particles with radii and , the van der Waals force is modified to [75]

In Equation (2), is the distance between the particle surfaces. This formulation accounts for the geometric difference from the sphere–plane system, with the force depending on both particle sizes. As demonstrated in Figure 5a, the mechanism of van der Waals force action is illustrated. As demonstrated in Figure 5b, the van der Waals force is proportional to the Hamaker constant (A) and inversely proportional to the sixth power of the contact distance (z). This relationship is expressed in Equation (1). This finding indicates that the augmentation of contact distance through surface microstructure design or the utilization of low-surface energy materials constitutes the primary strategy for the diminution of adhesion force. It has been demonstrated that when the structural period () and particle size () satisfy (the critical ratio that has been verified through experimentation is 1:5), surface protrusions can effectively limit the particle–substrate contact area [44].

The interparticle interactions exhibited by van der Waals forces are characterized by a duality: when the interparticle spacing is less than 10 nm, the particle–substrate interaction is dominant; when the interparticle van der Waals force (∝) between particles exceeds the particle–substrate interaction, a multiparticle aggregate is formed and spontaneous detachment is triggered (Figure 5c). The figure presents a microscopic image of the particles formed by interparticle van der Waals forces during particle aggregation. The total disengagement force of the aggregates is satisfied as follows [77]:

In Equation (3), denotes the interparticle van der Waals force, signifies the interparticle–substrate van der Waals force, and represents the total number of particles. The experimental observations demonstrated that the aggregation rate of particles on the nanostructured surface (exceeding three particles/cluster) was 72.4%, which was significantly higher than the 18.6% aggregation rate observed on the flat surface. The consequence of this collective detachment mechanism is the increased size of the particle aggregates, which in turn facilitates their removal by gravity or applied centrifugal force [44]. The reversal of the direction of van der Waals forces, from “adhesion-promoting” to “detachment-driving,” is achieved through the dual mechanism of nanostructuring to regulate the contact radius and induce particle aggregation.

From an engineering perspective, van der Waals force serves as a normalized microscopic indicator of dust–surface adhesion strength. Although it does not directly quantify system-level performance, a reduced van der Waals interaction is closely associated with lower dust retention probability, mitigated abrasive wear, and the improved durability of mechanical interfaces and sealing components. Therefore, this metric provides a physically meaningful basis for comparing material surfaces and coating strategies across different experimental platforms and dust simulants.

3.2. Hydrophobic Angle

The water contact angle (WCA) is defined as the contact angle formed by a droplet on a solid surface and is a measure of the surface’s wettability [78]. As demonstrated in Figure 5d, the definition of WCA is as follows: when the contact angle is greater than 90°, the surface exhibits hydrophobicity; when the contact angle is greater than 150°, the surface is superhydrophobic (e.g., the lotus leaf effect). A larger hydrophobic angle is indicative of a lower surface energy and a smaller actual contact area between the droplet and the solid, which in turn reduces the liquid bridge effect (i.e., the role of the liquid film in enhancing dust adhesion). A larger hydrophobic angle is indicative of a lower surface energy of the interface, and a low-surface energy interface has a significant effect on the enhancement of the dust removal effect. Consequently, the size of the hydrophobic angle is a significant index for the evaluation of microscopic dust control.

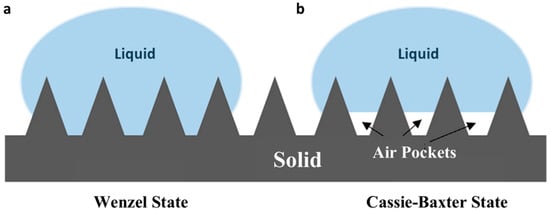

The wetting behavior of droplets can be described using the Wenzel model and the Cassie–Baxter model. The Wenzel model effectively describes the wetting behavior of droplets when they fully wet a rough surface (Figure 6a) [79]. However, in certain cases, as shown in Figure 6b, the droplet cannot enter the microscopic grooves of the rough structure and instead partially suspends at the composite interface formed by the surface microstructure and gas. To characterize this non-fully wetted state, the Cassie–Baxter model was proposed to describe the wetting behavior of droplets at the solid–gas composite interface [80].

Figure 6.

Schematic diagrams of the (a) Wenzel model and the (b) Cassie-Baxter model. Copyright 2017, Elsevier [80].

Recent studies have revealed that the dust prevention mechanism of highly hydrophobic angular surfaces is mainly reflected in two aspects: the Cassie–Baxter state stability is characterized by a superhydrophobic surface (WCA > 150°) that reduces the actual particle–substrate contact area to less than one-twentieth of the Wenzel state. This objective is realized through the implementation of an air cushion layer, which is secured by a micro–nano-composite structure. The air cushion effect has been demonstrated to effectively isolate the direct adhesion of micron-sized particles and significantly reduce the intensity of van der Waals force action. Capillary force suppression refers to the inhibition of the formation of the capillary bridging force on hydrophobic surfaces. The calculation formula for capillary bridging force is [81]

In Equation (4), is the gas–liquid interfacial tension, is the radius of the contact line between the particle and the surface, and is the contact angle of the liquid on the surface. This mechanism can avoid the secondary adhesion enhancement caused by the fluctuation of environmental humidity, when > 90°, is negative, and the capillary force turns to the removal force, further weakening the particle adhesion.

When preparing superhydrophobic surfaces, the commonly used preparation methods mainly include the following two steps: first, microstructures are formed on the surface using methods such as laser etching or magnetron sputtering; second, surface modifiers are used to modify the surface, typically employing low-surface energy substances such as fluorosilanes to form self-assembled films, thereby effectively reducing the surface energy of the material and enhancing the contact angle.

In practical lunar applications, the contact angle is primarily used as an indirect indicator of surface energy and effective contact area rather than a direct measure of dust removal efficiency. A higher contact angle generally correlates with reduced dust accumulation rates, delayed surface coverage, and the enhanced retention of optical transmittance and thermal control performance. Consequently, contact angle measurements enable the relative comparison of passive dust mitigation surfaces under different preparation methods and simulant conditions.

3.3. Roll Angle

Rolling angle (RA) is a pivotal parameter in the characterization of the dynamic wettability of a solid surface (Figure 5e) [82]. Rolling is defined as the critical angle formed between the surface and the horizontal plane when a droplet commences rolling on an inclined surface. The physical nature of the phenomenon under investigation reflects the equilibrium relationship between the adhesion force of the droplet on the material surface and gravity. When the rolling angle is minimal, the droplet can be detached from the surface at a small inclination angle. This indicates that the material surface has low adhesion properties, which is particularly important in the field of dust control. For instance, during the rolling process, rainwater has been observed to carry particulate contaminants that adhere to its surface, thereby achieving a self-cleaning effect.

The roll angle is directly related to the surface’s resistance to wetting. The measurement of roll angle has been demonstrated to quantify the ability of a material surface to resist liquid wetting. It has been demonstrated that the smaller the roll angle, the more hydrophobic the surface, the more pronounced the rolling action of liquid droplets, and the more efficient the disengagement of particulate contaminants. In the context of the textile industry, surfaces exhibiting a roll angle of less than 10° are designated as superhydrophobic, a property that markedly diminishes dust deposition through the “lotus leaf effect.” The optimization of the chemical composition and microstructure of the surface has been demonstrated to reduce the roll angle, thereby enhancing dust protection.

The roll angle reflects the dynamic adhesion hysteresis of a surface and provides insight into the ease with which particles or droplets can be mobilized under external disturbances such as vibration or gravity-assisted shedding. In lunar engineering scenarios, a lower roll angle implies a reduced dust residence time and enhanced self-cleaning capability, which is particularly relevant for inclined or vertically deployed components such as solar panels and radiators. As a dynamic metric, roll angle complements static wettability parameters and supports the cross-study comparison of surface designs.

3.4. Area Ratio of Monthly Dust Distribution

The Lunar Dust Coverage Area (LDCA) is defined as the ratio of the coverage of lunar dust particles on a material surface or equipment structure to its total surface area [66]. This is typically expressed as a percentage or mass of dust per unit area (mg/m2). This parameter is directly indicative of the spatial distribution characteristics of lunar dust on a microscopic scale, and its physical significance lies in quantifying the degree of lunar dust accumulation at the interface and its influence mechanism on equipment performance.

In the experiment, simulated lunar dust was placed on the surface of the specimen and made to completely cover the surface of the specimen. Subsequently, centrifugal force or gravity was applied to the specimen in order to remove the lunar dust. As demonstrated in Figure 5f, subsequent to the experiment, the substrate surface image was binarized, and the LDCA of the extracted specimen surface was analyzed and calculated using image processing software (ImageJ 1.54g). The efficiency of lunar dust removal can be characterized as [83]

In Equation (5), is the lunar dust protection efficiency and is the surface area of the specimen.

The experiment itself revealed that the distribution of lunar dust on the substrate could be observed through the use of an optical microscope, as demonstrated in Figure 5g. Furthermore, the substrate surface image subsequent to dichroic processing could be discerned, as illustrated in Figure 5h.

The lunar dust distribution area is primarily influenced by the following multi-physical field coupling: (1) Surface wettability and electrostatic properties: low-surface energy materials (e.g., fluoropolymers) can reduce the LDCA by lowering the van der Waals force and electrostatic adsorption of lunar dust particles. (2) Microstructure design: biomimetic micro–nanostructures (e.g., honeycomb or trench arrays) can limit the migration path of lunar dust to keep the LDCA under 10% by restricting the lunar dust migration path.

LDCA provides a spatially resolved and visually intuitive measure of dust accumulation on functional surfaces. From a system-level viewpoint, LDCA is directly related to performance degradation mechanisms, including reduction in solar power output, the attenuation of optical signals, and the alteration of thermal emissivity. Although absolute LDCA values depend on test configuration and simulant properties, normalized comparisons within and across studies offer a practical proxy for evaluating dust-induced performance loss.

3.5. Characterization of Dust Protection Efficiency

Dust Resistance Efficiency Characterization (DREC) is a core metric for quantifying the dust resistance of a material or surface, usually achieved through the mass ratio method, which is defined as [84]

In Equation (6), denotes the initial dust loading mass, while signifies the residual dust mass on the surface subsequent to the test. The method is predicated on the direct observation of the dust’s capacity to adhere or dislodge from the surface, operating on the principle of mass conservation. The mass ratio method is a widely utilized technique in the assessment of the dust-proof performance of industrial dust-proof coatings, spacecraft thermal control systems, and precision electronic equipment, owing to its simplicity and reproducibility. The efficacy of dust removal is measured using a device (Figure 5i). The apparatus under consideration is a rotary table, onto which the lunar dust is introduced at the center during the test. The rotary table is rotated at a constant and uniform speed by an external driving force. The operational speeds of the rotary table were varied, and the relationship between rotational speed and the amount of lunar dust shedding was plotted by measuring the mass of lunar dust on the platform after rotation. The results are displayed in Figure 5j. Additionally, dust collection efficiency can be preliminarily assessed by observing dust dispersion on the inclined platform (Figure 5k). By dispersing dust particles within a closed chamber via airflow, the amount of dust adhering to the inclined surface coating characterizes dust collection efficiency. Notably, the surface structure of lotus leaves in nature is a superhydrophobic biomimetic structure exhibiting an exceptionally high contact angle of 160 degrees [85]. Current methods for constructing microstructures to achieve superhydrophobicity are directly inspired by the microstructure of lotus leaf surfaces.

The mass ratio-based dust protection efficiency is widely adopted as a quantitative and reproducible indicator for comparing dust mitigation strategies. While this metric does not directly correspond to a specific system output parameter, it reflects the overall effectiveness of dust detachment under defined mechanical or electrostatic driving conditions. When interpreted as a relative efficiency metric rather than an absolute predictor, mass ratio measurements enable meaningful comparison across different test methods, materials, and lunar dust simulants.

In the field of lunar dust protection research, researchers employ a range of lunar dust simulants, selected based on the specific objectives of their study, to facilitate precise simulation of the lunar environment and the execution of targeted experiments. In the domain of active protection research, researchers predominantly utilize the JSC-1A simulant, which possesses a particle size range of 50–75 μm and is capable of effectively simulating the vacuum conditions of the Moon within a high-vacuum environment of 10−6 kPa [30]. Furthermore, the FJS-1 simulant, which exhibits a composition and particle size distribution analogous to that of JSC-1A, is occasionally selected [86]. In the case of the FJS-1 simulant, researchers first conduct an initial assessment under atmospheric conditions, followed by further simulation of lunar conditions under low-gravity and vacuum conditions to comprehensively evaluate its protective effectiveness under different conditions. In the domain of passive protection research, researchers employ the CLDS-i simulant, a product of the Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences [87]. The composition of this simulant is highly similar to lunar dust collected during the Apollo missions, with particle sizes in the micron and submicron range. Furthermore, it possesses electrical properties such as a high specific surface area and low electrical conductivity that are similar to those of real lunar dust. This facilitates the effective simulation of the physical and chemical behavior of lunar dust, thereby providing a reliable experimental foundation for passive protection research. In studies on active and passive synergistic protection, researchers can also use the JSC-1A and FJS-1 simulants [62,88].

In the domain of lunar dust protection technology, the precise calibration of parameters such as contact angle, surface energy, and roughness is of paramount importance for enhancing protection efficiency. These parameters are intended to visualize the interaction between the material surface and the lunar dust particles, and thus have an impact on the protection effectiveness. In Table 1, a systematic summary of the most commonly utilized techniques for protection against lunar dust is provided, along with the associated parameters and protection efficiencies.

Table 1.

Common lunar dust protection mechanisms.

Active protection techniques primarily utilize external energy sources, such as electrical or mechanical forces, to facilitate the removal of lunar dust from the material surface, thereby reducing adhesion. For instance, electrostatic cleaning techniques leverage electrostatic principles to facilitate the removal of lunar dust, exhibiting typical protection efficiencies ranging from 70% to 80%. Conversely, electromechanical dust shields can attain protection efficiencies of up to 98%, attributable to their distinct mechanism of action. However, the implementation of active protection techniques is greatly limited by the limited energy resources on the Moon and the large costs associated with energy storage and power generation. The fundamental principle of passive protection technology is to optimize the surface structure of materials with a view to enhancing their self-cleaning properties. It is evident that technologies such as fluoropolymer coatings, which inhibit adhesion by precisely controlling the surface roughness to 7 nm, and superhydrophobic zinc oxide coatings, which increase the contact angle to 150°, have the capacity to significantly reduce the adhesion of lunar dust to material surfaces. The technologies in question are distinguished by their autonomy from external energy sources, their high efficiency, their stability and reliability, and their potential to contribute to the solution of the lunar dust problem. Synergistic protection techniques combine the advantages of both active and passive protection techniques. For instance, the integration of electrostatic capture and transfer techniques with active electromechanical dust shielding, in conjunction with low-surface energy coatings, has been demonstrated to yield protection efficiencies ranging from 80% to 90%. It is evident that these techniques have considerable potential to further improve lunar dust protection efficiency.

Regardless of whether protective measures are active, passive, or collaborative, all protective measures must be adapted to the extreme lunar environment. Protective components must have sufficient durability to withstand the near-vacuum conditions of the lunar atmosphere, with a pressure of approximately 10−13 kPa. Additionally, it must be ensured that components can operate reliably under vacuum conditions that approximate key aspects of the lunar environment. Technologies such as energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) and wavelength-modulated coatings (WFMs) have proven their effectiveness in such environments [62]. Furthermore, these systems must be able to withstand extreme temperature fluctuations, with surface temperatures on the Moon reaching up to 127 °C during the day and dropping to −183 °C at night. This requires the use of protective technologies with excellent thermal stability and resistance to thermal shock to ensure stable operation under such conditions. Additionally, these technologies must be adapted to microgravity environments, where gravity is only one-sixth that of Earth. In microgravity environments, dust particles are more likely to become suspended and adhere. Therefore, the development of protective technologies must prioritize optimizing electric field strength and distribution to enhance removal efficiency and adopt alternative methods to ensure functional effectiveness.

4. Active Protection Technology

Active protection techniques encompass natural, mechanical, and electrostatic dust removal approaches [98,99]. The primary techniques employed for the removal of dust, both natural and mechanical, principally comprise brushing, fluid impact, and ultrasonic methods. The process of brushing involves the removal of dust particles from surfaces through physical contact. This method is effective for larger particles but less effective for smaller particles and may result in surface scratches. Fluid impact, which employs high-velocity air or liquid jets to impinge on contaminated surfaces, has been demonstrated to be effective in dislodging dust particles. However, the low-gravity environment of the Moon imposes limitations on the efficacy of this method, and its implementation demands significant resources. The application of ultrasound through high-frequency vibration has been demonstrated to disperse dust particles; nevertheless, this method exhibits limited efficacy in removing particularly recalcitrant dust particles. Electrostatic precipitation techniques leverage the force of an electric field on charged dust particles and the dielectrophoretic force of polarized dust particles to overcome the adhesive forces between the dust particles and the surface, thereby promoting removal. The technology exhibits several key advantages, including high efficiency, minimal energy consumption, and the absence of mechanical wear.

4.1. Natural and Mechanical Dust Removal Techniques

It is evident that, due to the absence of an atmosphere on the Moon, the utilization of wind power for the purpose of natural dust removal is not a viable option. However, the gravitational environment of the Moon offers another possibility for natural dust removal. With regard to the findings of the Viking mission on Mars [100], no accumulation of fine dust was observed on the camera lens of the vehicle. This was attributed to the natural settling of fine dust due to the gravitational forces of Mars. It is evident that the principle underpinning the natural dust removal technology of the Moon can be utilized as a foundation for the design of the Moon’s solar cell wings, which are to be installed in a vertical or tilted configuration. Moreover, the gravitational pull of the Moon can be utilized to assist in the natural elimination of dust, thereby reducing the adverse effects of dust accumulation on the performance of equipment.

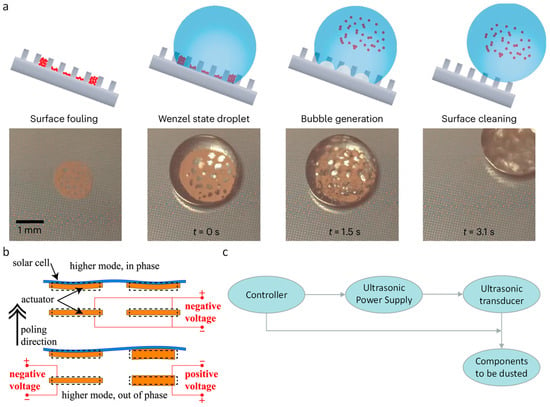

Mechanical dust removal includes brushing, fluid impact force, and ultrasound. The earliest dust removal strategy used on the Apollo missions was nylon brushes, but experiments have shown that nylon brushes cause significant scratches on surfaces and a layer of Moon dust particles remains. Dust removal based on fluid impact is less well studied and centers on the Leidenfrost effect of water droplets—when a water droplet contacts a hot surface [101], the bottom of the droplet vaporizes instantly due to the rapid absorption of thermal energy, forming a continuous pad of steam that separates the droplet from the surface and suspends it (the Leidenfrost effect). During this process, the expansion of the pad generates momentum that can push the Moon dust particles attached to the surface to detach, while the flow of steam further carries away the particles to achieve cleaning (Figure 7a) [93], which is also applicable to the cleaning of spacesuits in airlock environments.

Figure 7.

Natural and mechanical dust removal techniques. (a) Schematic diagram of the removal of dust by the Leidenfrost phenomenon with cryogenic liquids [93]; Copyright 2024, Springer Nature. (b) Schematic diagram of the structure and operation of piezoelectric actuators [34]; Copyright 2024, Elsevier. (c) An ultrasonic removal system for surface-absorbed lunar dust.

In terms of the conditions under which the Leidenfrost effect occurs in water droplets, the Leidenfrost point of a water droplet on a conventionally smooth surface is around 250 °C in terms of temperature, whereas micro- and nanostructured surfaces, such as microcolumns, can be cooled down to a temperature of around 130 °C (the Leidenfrost-like effect) through enhanced heat transfer and vapor locking. For wetting conditions, the surface needs to be hydrophobic or microstructured (e.g., arrays of micropillars) to reduce the direct contact between the liquid and the surface, helping to stabilize the vapor cushion and enhance the effect. Experiments have shown that the effect can be utilized to effectively remove particulate contaminants (micron-sized particles similar to Moon dust) from surfaces and crevices, and the attached particles can be efficiently carried away from the surface through the interaction of water droplets and steam bubbles. However, brushing and fluid impact dust removal techniques are prone to damaging functional surfaces when used for long periods of time and have limitations in the resource-constrained lunar environment and can currently be used as an auxiliary means of dust removal, but with significant prospects for development.

The efficiency of mechanical dust removal can be evaluated by the energy balance between the applied force and dust adhesion. For ultrasonic cleaning, the threshold vibration amplitude () required to dislodge a particle is given by [102]

In Equation (7), η is the dynamic viscosity of the medium (vacuum for lunar environment, approximated as 0) and includes van der Waals and electrostatic forces. In vacuum, the critical acceleration () to overcome adhesion is given by

In Equation (8), is the particle mass. Experimental data show that for 10 μm lunar dust particles is typically 104–105 m/s2, achievable by piezoelectric actuators.

The most prevalent mechanical dust removal technique currently under development is ultrasonic dust removal. For instance, the technique of piezoelectric actuators generating vibrations to remove dust from the surface of a solar cell, as demonstrated in Figure 7b, is based on the complementary nature of the piezoelectric effect and vibration modes [34]. A piezoelectric actuator is capable of generating vibrations by converting electrical energy into mechanical energy through the inverse piezoelectric effect. Applying an AC voltage to the piezoelectric actuator results in the actuator generating high-frequency vibrations, which are subsequently transmitted to the entire solar cell structure via the inactive surfaces affixed to the solar cell. It has been demonstrated that different vibration modes can be realized by varying the phase and frequency of the drive signal. The same-phase vibration mode has been shown to subject dust particles on the surface of the solar cell to a uniform vibration effect, while the anti-phase vibration mode has been demonstrated to form an alternating vibration field on the surface of the solar cell, which has been shown to enhance the loosening and dislodging of dust particles. It is evident that the judicious configuration of the actuator and the driving signal is instrumental in achieving the effective removal of dust from the solar cell surface.

Additionally, an ultrasonic transducer is applied to the component to be cleaned to achieve ultrasonic cleaning. During the cleaning process, the excitation signal generated by the controller is amplified by the ultrasonic power supply, causing the ultrasonic transducer to vibrate (Figure 7c). The ultrasonic cleaning process does not require the use of chemical cleaning agents, which is noteworthy, thereby avoiding the potential hazards of chemicals to equipment and the environment. Ultrasonic technology is suitable for low-gravity environments, making it ideal for use on the lunar surface. The ultrasonic cleaning system is integrated into remotely controllable equipment, which is expected to reduce the risk of astronauts coming into direct contact with lunar dust. However, it is important to note that such systems are not without drawbacks. Ultrasonic generators require a significant amount of electrical energy to produce high-frequency vibrations. This places high demands on energy supply during lunar exploration missions. In the vacuum environment of the lunar surface, the propagation and effectiveness of ultrasonic waves may be affected, potentially reducing the efficiency of lunar dust removal. For larger particles of lunar dust, ultrasonic vibrations may be insufficient to completely remove them. Alternative dust removal methods may be required to enhance overall cleaning effectiveness. Future research and development could be optimized to address these shortcomings, thereby increasing the utility and reliability of the technology in the lunar environment.

4.2. Electrostatic Precipitation Technology

In the domain of active protection against lunar dust, electrostatic dust removal represents a significant mechanism [46]. The fundamental principle underpinning this process is the utilization of electric field force and dielectrophoretic force, which function either in a synergistic manner or independently to achieve dust removal efficacy. In the electric field force mode, the electric field is constructed by applying voltage between the electrodes, thereby driving charged dust particles in a directional manner through the application of the electric field force, thus achieving the separation of the dust particles from the surface. Conversely, the dielectrophoretic force is directed towards uncharged dust particles. When immersed in a non-uniform electric field, these particles will be polarized to form a dipole moment. This, in turn, will be displaced under the action of the dielectrophoretic force. The combined effect of these two forces, when either alone or in concert, is to overcome the adhesion between the dust particles and the surface, thus achieving the objective of dust removal.

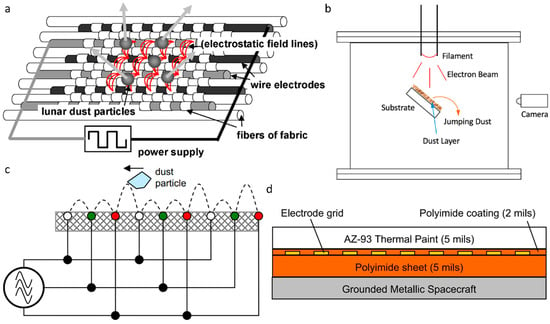

In the practical application scenarios of lunar dust protection, electrostatic dust removal technology has demonstrated diverse innovations. The automatic spacesuit cleaning system developed by Kawamoto and Hara utilizes an electrostatic barrier structure (Figure 8a) [32], which has been demonstrated to achieve a cleaning rate in excess of 80% by applying a single-phase rectangular voltage to parallel wire electrodes sewn into insulating fabrics. This objective is realized through the integration of mechanical vibration and vacuum environment operation. Despite the fact that this system exerts only a limited effect on the removal of dust particles smaller than 10 μm, it can nevertheless be utilized as an initial solution for the cleaning of spacesuits. This will result in a significant reduction in the operation time of astronauts on the Moon. The principle of the method for removing surface lunar dust using electron beams, as proposed by Farr et al., is based on the experimental setup shown in Figure 8b [47]. The application of an electron beam to dust particles has been demonstrated to result in the acquisition of a sufficient charge, thereby inducing electrostatic repulsive forces. It has been demonstrated that these forces are capable of overcoming not only the cohesive forces between particles and the adhesive forces present at the surface of the particles, but also gravitational forces. The consequence of this process is the release of the dust particles. Experiments have demonstrated that, with optimized electron beam parameters, the method can achieve 75–85% cleanliness in approximately 100 s. Moreover, the maximum level of cleanliness achieved is comparable for spacesuit samples and glass surfaces, thus demonstrating the method’s generalizability. The electrodynamic dust shield technology developed by Calle’s team is based on the concept of a motorized window shade with a three-phase electrode configuration (Figure 8c) [30]. The generation of traveling waves is facilitated by a three-phase AC power supply, which functions to transport dust particles. The technology utilizes two forces: the force of the electric field on the charged dust particles and the dielectrophoretic force on the polarized dust particles. These forces overcome the adhesion between the dust particles and the surface, thereby achieving dust particle removal. The practical application of the modified technology is demonstrated in Figure 8d, where the electric field-driven shielding is embedded in a substrate coated with AZ-93 thermal paint for the protection of metallic thermal emitters from lunar dust. This demonstrates the extensive range of applications and the technology’s remarkable adaptability in protecting surfaces and devices, including solar panels and optical components, from lunar dust [20].

Figure 8.

Electrostatic dust removal techniques. (a) Electrostatic cleaning system for removing lunar dust adhering to spacesuit fabrics [32]; Copyright 2011, American Society of Civil Engineers. (b) Schematic of experimental setup for electron beam surface dust removal [47]; Copyright 2020, Elsevier. (c) Three-phase electrode configuration of an electrodynamic dust shield [30]; Copyright 2009, Elsevier. (d) Schematic of the surface cross section of an electrodynamic dust shield embedded in a substrate coated with AZ-93 thermocoating (the unit “mils” is approximately 0.0254 mm) [20]. Copyright 2011, Elsevier.

A comprehensive review of the technical characteristics of electrostatic dust removal technology reveals several key advantages. These include high efficiency, low energy consumption, no mechanical wear, and strong environmental adaptability. Consequently, the technology is well suited to meeting the protection needs of a variety of surfaces and equipment. However, the technology still faces many challenges: the removal efficiency of small dust particles less than 10 μm is not yet optimal; the optimization of electric field distribution on the surface of complex shapes and the improvement of the application effect require in-depth research; and at the same time, the reliability of the system for long-term operation under the extreme lunar environment needs to be solved. In the future, it is imperative that in-depth research be carried out on these technical bottlenecks, with a view to promoting the comprehensive application and development of electrostatic dust removal technology in the field of lunar dust protection.

5. Passive Protection Technology

The term “lunar dust passive protection technology” refers to approaches aimed at reducing the adhesion of lunar dust particles through material surface modification or structural design [103,104]. This process occurs without the reliance on external energy sources such as electricity or mechanical force. The fundamental principle of the process pertains to the modification of the micro-morphology or chemical properties of the material surface. The process is achieved through the utilization of physical or chemical methodologies, thereby aiming to minimize the adhesion and coverage of lunar dust. In comparison with active protection technology, passive technology has become the focus of current research due to its lack of requirement for additional energy consumption, its high reliability, and its adaptation to the extreme lunar environment. Despite the fact that active protection technology demonstrates high dust protection efficiency, its energy consumption is frequently elevated and its configuration is frequently complex. The consequence of this elevated energy consumption and complexity is a reduction in reliability and an elevated risk of damage to the equipment. It must be noted that the application of active protection technology is not universally applicable to all instruments of this nature, on account of the inherent complexity of the technology. However, passive protection technology utilizing lunar dust is a cost-effective and straightforward method that can enhance the adaptability of spacecraft components to the lunar environment, thereby prolonging their service life. Through surface-level protection of instruments and equipment, passive protection strategies improve resilience against lunar dust contamination without compromising system stability.

The efficacy of passive dust control is contingent upon the dust control mechanism of the equipment in question. It is important to note that a single dust control mechanism may not be sufficient to achieve the desired dust reduction effect. In order to achieve an effective and long-term control effect, it is necessary to elucidate the protection mechanism of lunar dust. In order to achieve effective long-term control, it is necessary to clarify the protection mechanism of lunar dust. Passive protection methods include the implementation of protective covers, dust shields [86], surface modification, and other associated practices. The concept of surface modification encompasses a range of disciplines, including energy regulation, surface roughness regulation, and the application of low-adhesion coatings.

5.1. Surface Energy Regulation

In the domain of lunar dust protection technology, surface energy modulation is recognized as a pivotal strategy that aims to curtail the interaction force between lunar dust particles and the substrate material by modulating the energy state of the material surface. Lunar dust, defined by its micron or submicron dimensions, is of particular interest due to its elevated activity and surface charge properties, which contribute to its adsorption and deposition on the surfaces of conventional materials, thereby affecting the functionality of lunar surface devices. By modulating the surface energy, the adsorption mechanism can be regulated at the molecular level, thus providing a passive yet effective technological solution to prevent lunar dust contamination.

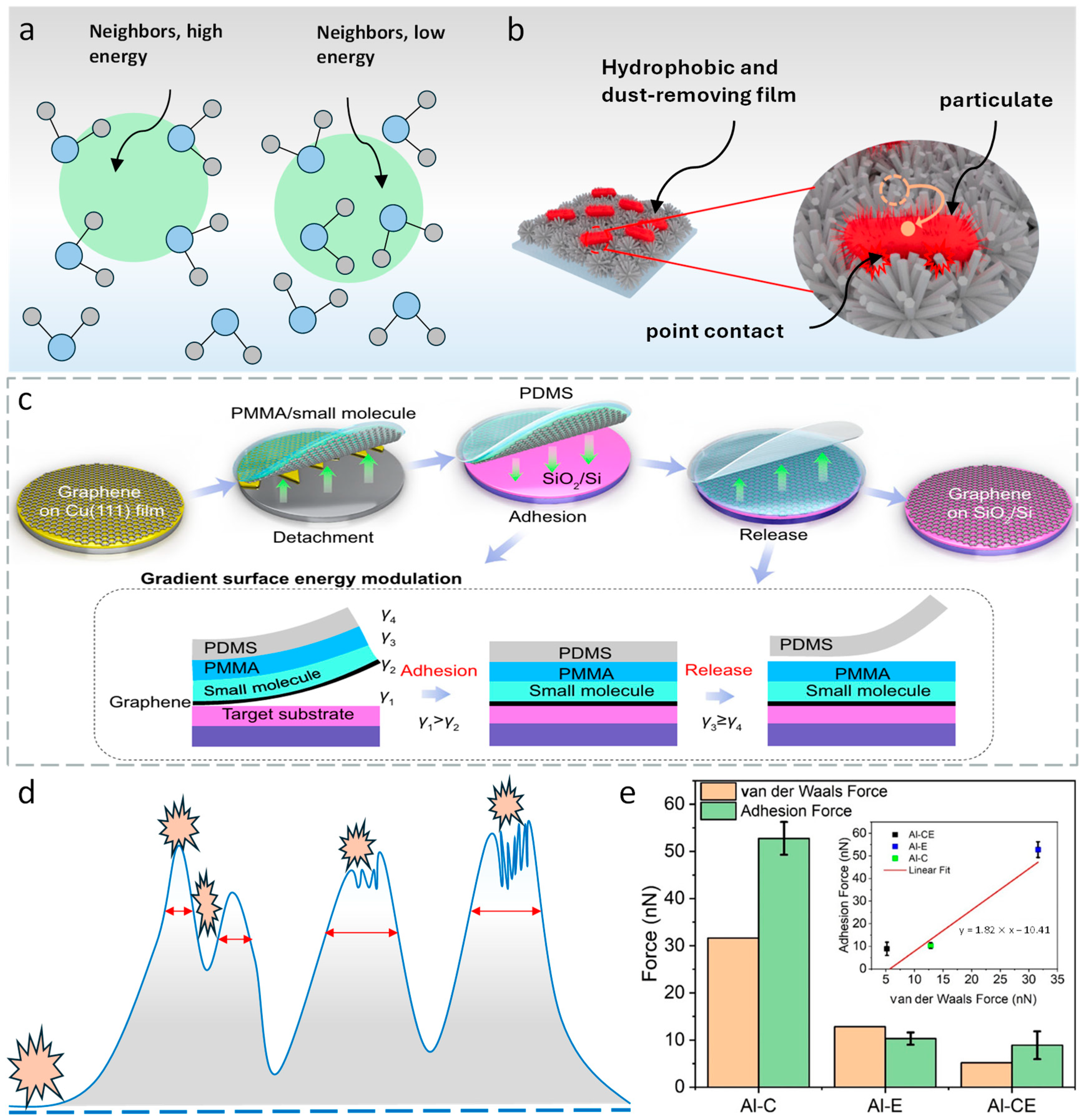

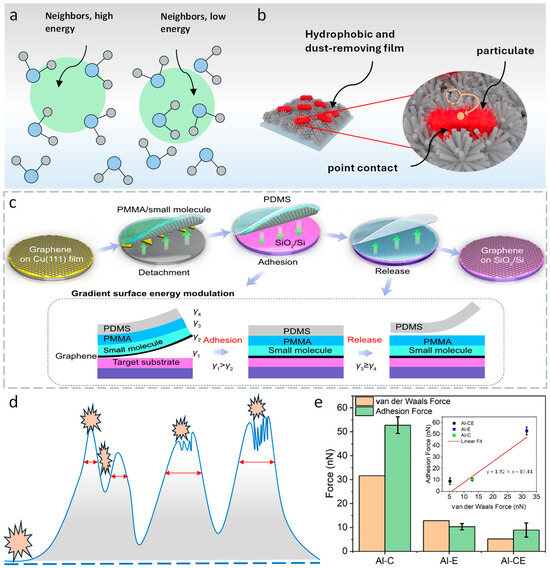

Surface energy is defined as the interaction force between molecules on the surface of a material. This method is frequently employed to characterize the surface affinity of a material for external substances. As demonstrated in Figure 9a, studies have indicated that materials characterized by a low number of molecular or atomic close neighbors on the material surface exhibit a high surface energy. Conversely, materials characterized by multiple close neighbors have been observed to exhibit a diminished surface energy. The hypothesis was that high-surface energy materials would tend to have strong adsorption capacities, while low-surface energy materials would exhibit weak adsorption properties. In the context of lunar dust protection, the van der Waals force and electrostatic adsorption effect between lunar dust particles and surfaces can be effectively mitigated by reducing the surface energy of materials, thereby hindering lunar dust deposition. Theoretically, surface energy regulation can be achieved through altering the molecular arrangement and polarity state of the surface by chemical modification or physical treatment. The effect of surface energy () on dust adhesion can be described by the work of adhesion () as follows [105]:

Figure 9.

(a) Schematic diagram of molecular or atomic proximity number and surface energy of a material surface. (b) Schematic diagram of F-ZMT thin film for dust evacuation [106]; Copyright 2024, MDPI. (c) Gradient surface energy modulation transfer method for wafer-scale 2D materials [96]; Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. (d) Schematic diagram of particle contact with different surface conditions [87]; Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (e) Adhesion of different treated Al surfaces to lunar dust [87]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society.

In Equation (9), is the contact angle. For low-surface energy coatings (e.g., fluoropolymers with ≈ 20 mN/m), is reduced, weakening the van der Waals interaction between dust and the surface. This leads to a lower adhesion force ( ∝ ), as observed in superhydrophobic surfaces with > 150°.

At this stage, chemical modification and surface coating techniques are the primary methods employed for surface energy modulation. Chemical modification employs self-assembled monomolecular layers (SAMs) to introduce low-polarity groups, thereby forming a dense modification layer on the surface of the material and consequently reducing the surface energy. The focal point of this technology is the selection of suitable molecules for modification, which are characterized by low polarity and effective self-assembly properties. This process is instrumental in ensuring the uniformity and density of the modification layer, thereby safeguarding the long-term stability of the function within the lunar dust environment. In recent years, significant progress has been made in the field of surface modification using fluorine-containing compounds and silane derivatives [60]. The experimental results demonstrate that the contact angle of the surface of the modified material increases significantly, thereby further verifying its low-surface energy characteristics. Xin Gao and his team developed a transfer medium characterized by a gradient distribution of surface energy (Figure 9c) [96]. In this medium, a small molecular layer of ice flakes is adsorbed on the surface of graphene. This process effectively reduces the surface energy of graphene, thereby ensuring that, during the process of graphene adhesion to the target substrate, the surface energy of the substrate is significantly higher than that of the graphene. This process is known to result in satisfactory dry affixation. Conversely, the utilization of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) as a support layer facilitates the dry lamination of graphene to the designated substrate, thereby diminishing interfacial water oxygen doping. The application of ice flakes, as a small molecule buffer layer, ensures the effective prevention of direct contact between the upper layer of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) polymer film and the graphene, thus preventing contamination and ensuring a pristine graphene surface. This approach not only yields a clean graphene surface but also confers a dust-proof effect.

The utilization of polymer coatings with low-surface energy properties has become a prevalent approach. The deposition of a uniform layer of low-surface energy fluoride onto the substrate surface facilitates the construction of a physical isolation layer [107], thereby effectively preventing direct contact between the lunar dust and the underlying material. As Li et al. report, the material can also be covered with a low-adhesion film in order to reduce surface adhesion. The proposed film would possess multifunctional properties, incorporating superhydrophilic [106], antifouling, and antimicrobial characteristics. In the development of advanced self-cleaning, superhydrophilic, and oleophobic materials, Motahareh Borzou Esfahani and colleagues prepared a silica film with anti-reflective properties (Figure 9b) [97]. This objective was realized through the preparation of a ZnO microstructured thin film on a fluorine-doped tin oxide substrate (F-ZMF). The glass surface has been treated with a dust-repellent and ice-resistant coating, which has been found to significantly reduce adhesion. This results in a dust-repellent effect.

5.2. Surface Roughness Regulation

Surface roughness conditioning is a passive protection strategy that has been developed in order to reduce the actual contact area of lunar dust particles. The objective is realized through the creation of specific micro–nanostructures on the material surface. These structures serve to reduce van der Waals forces and electrostatic attraction [83]. Due to their minute proportions and intricate morphology, lunar dust particles have the capacity to readily establish extensive continuous contact areas on sleek surfaces. This occurrence serves to augment the adhesion between the particles and the substrate, consequently precipitating wear and the deterioration of equipment performance. The adjustment of surface roughness facilitates a self-cleaning mechanism, akin to that observed in lotus leaves, while ensuring long-term stability under diverse environmental conditions through multi-scale structural design. Research has demonstrated that the surface texture of a material exerts a direct influence on the microscopic contact area of the interface. In the case of solid surfaces exhibiting micrometer or nanometer textures, the contact area between dust particles and the surface is significantly reduced, thereby diminishing the magnitude of the adsorption force (Figure 9d). Furthermore, the modulation of surface roughness has been demonstrated to facilitate the downward movement of dust particles under the action of gravity, thereby enabling the self-cleaning functionality [108]. The construction of rough surfaces with a hierarchical structure (i.e., supplemented with nanostructures at the microscale) has been demonstrated to facilitate the consideration of both anti-adhesion and self-cleaning properties. This ensures that dust accumulation on the lunar surface is prevented, thereby protecting the long-term stability of equipment and instruments [87].

The micro–nanostructures of superhydrophobic surfaces (e.g., lotus-like papillae or honeycomb arrays) resist particle impact and maintain superhydrophobicity under lunar dust exposure. These structures reduce the actual contact area between dust and the surface, as described by the Cassie–Baxter model [109]:

In Equation (10), is the fraction of the solid–liquid interface. For a superhydrophobic surface with , the contact angle remains >150° even after dust impact, as the microstructures prevent dust particles from penetrating the air layer trapped between the surface and the dust. In addition, these structures typically have a high mechanical strength, can withstand the abrasive effects of lunar dust, and maintain their anti-adhesion properties over long periods of time.

Surface roughness adjustment can be achieved through methods such as laser etching, laser perforation, or laser-assisted deposition, which facilitate the creation of micron- or nanometer-scale texture structures on the material surface [110]. The method is characterized by two major advantages: firstly, the processing precision is high and the structure is controllable; secondly, a multi-scale roughness design can be realized, which leads to a dust removal effect. By precisely adjusting the laser pulse energy, frequency, and scanning speed, the surface roughness can be modified to enhance the material’s self-cleaning properties. Plasma or chemical etching can also be used to microstructurally treat the surface of a material through a selective etching process to form randomly or periodically distributed micropores, microbumps, and other structures that reduce the actual contact area [111]. This approach is not complex and is straightforward to implement on a large scale. Nevertheless, effective control of the process parameters is imperative, and a thorough consideration of the balance between corrosion rate and surface uniformity is essential. Wang et al. developed a series of structures for reducing dust, employing chemical [87], electrochemical, and composite etching methods for the surface treatment of aluminum materials. This approach was found to be an effective method for improving surface roughness, thereby reducing the presence of dust (Figure 9e).

The template-assisted deposition method involves the utilization of pre-prepared micron- or nano-templates for the deposition of metals, ceramics, or polymers onto a substrate, thereby resulting in the formation of structured surfaces with regular or semi-regular arrangements. The multilevel roughness structure is determined by the modulation of the template’s size, alignment density, and deposition thickness [112]. As demonstrated in extant research, the method has been shown to significantly reduce the adhesion rate of lunar dust particles and improve self-cleaning [113].

6. Active–Passive Cooperative Protection Technology

6.1. Collaborative Protection Strategy

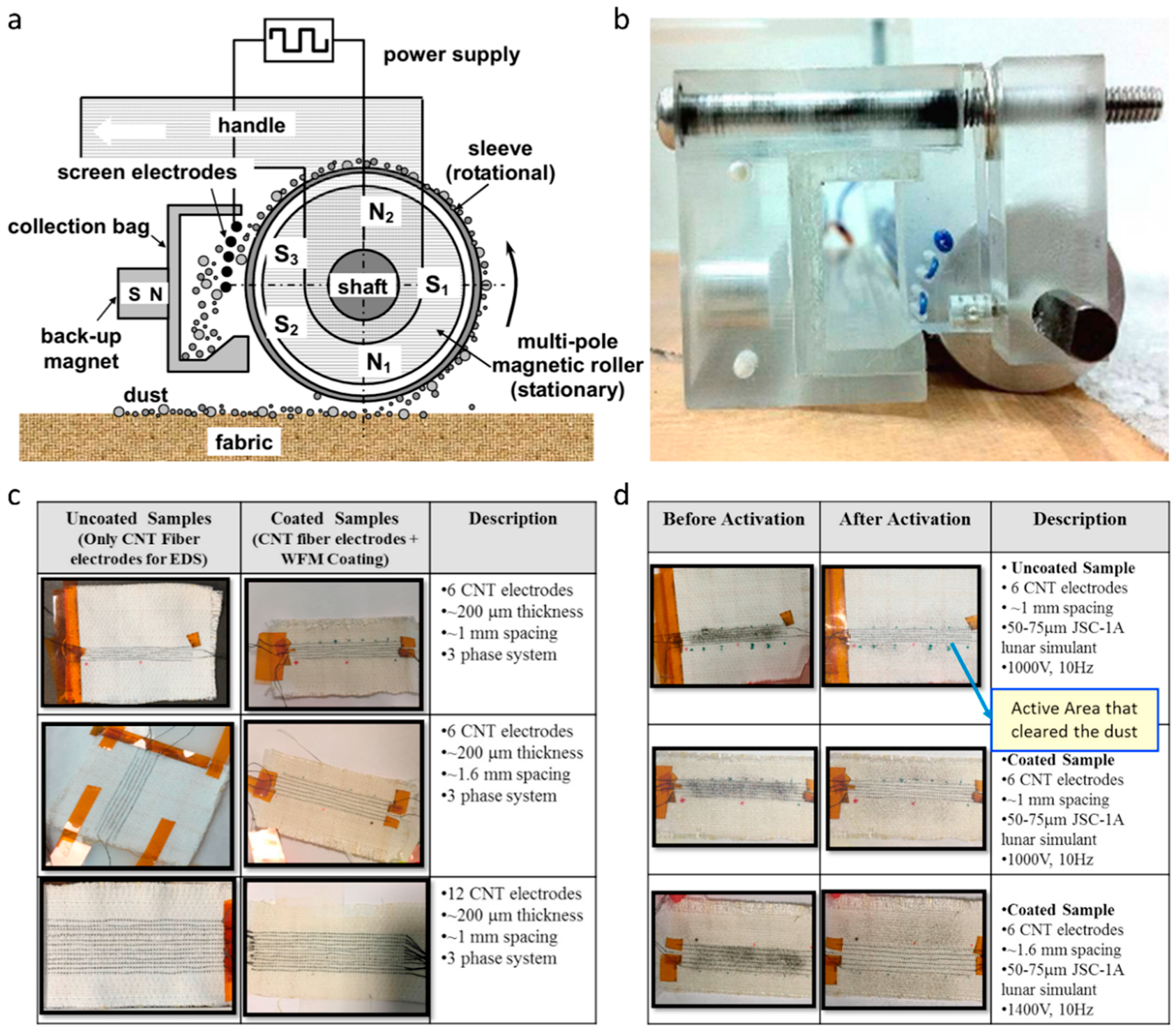

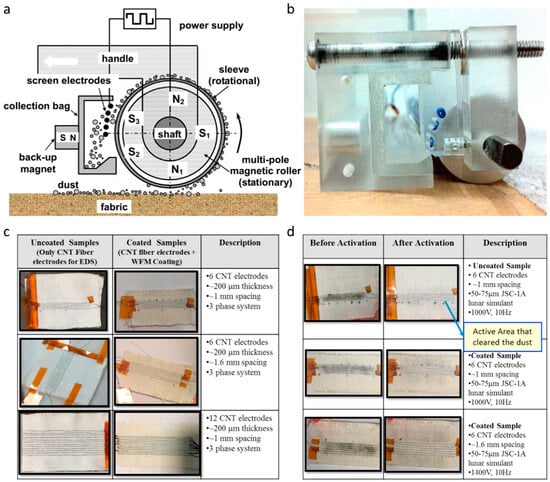

The fundamental concept underpinning the active–passive synergistic protection strategy is the enhancement of lunar dust mitigation efficiency through the integration of the respective advantages of active and passive protection technologies. Numerous studies have proposed a variety of active–passive hybrid approaches, combined with diverse dust protection mechanisms [114], including magnetic, electrostatic, and material synergistic protection. In active protection, the utilization of magnetic fields is employed for the guidance of lunar dust particles to facilitate their removal or preparation for subsequent dust removal procedures. Conversely, in passive protection, special materials are employed on the surface of the equipment, with the objective of accommodating the physical properties of lunar dust and enhancing the efficiency of lunar dust removal or protection. Kawamoto et al. developed a magnetic cleaning device based on the magnetic properties of lunar dust. The device under consideration is composed of the following components: a shaft, a fixed multipolar magnetic roller, a rotating sleeve, a flat magnet, and a collection bag [88]. The schematic diagram of the device is shown in Figure 10a, and the physical drawing is shown in Figure 10b. The device utilizes the friction between the fabric and the sandblasting sleeve to rotate the sleeve, thereby causing the dust adhering to the sleeve to be adsorbed by the magnetic roller under the action of magnetic force and friction. Consequently, the dust is separated. It has been demonstrated that the magnetic rollers incorporate rare-earth permanent magnets, which significantly enhance lunar dust capture capability and overall removal efficiency. This enhancement can be attributed to the electrostatic force generated by the magnets. In the experiment, the capture rate was defined as the ratio of the weight of the particles captured by the sleeve to the weight of the particles initially applied to the fabric; the separation rate was defined as the ratio of the mass of material collected in the collection bag to the weight of the particles captured by the sleeve; and the product of these two ratios was the total cleaning rate. The device demonstrated capture, separation, and total cleaning efficiencies of 44%, 90%, and 40%, respectively, indicating its effectiveness in lunar dust mitigation applications.

Figure 10.

Active–passive synergistic protection technology. (a) Schematic diagram of the principle of the cleaning device utilizing magnetic and electrostatic forces [56]; Copyright 2012, American Society of Civil Engineers. (b) Physical drawing of the cleaning device [56]; Copyright 2012, American Society of Civil Engineers. (c) Multiple specimens made of orthogonal fabric materials embedded with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) fiber electrodes and WFMs, along with their (d) static test results [62]. Copyright 2017, Elsevier.

As a further illustration of synergistic electrostatic and coating protection, Manyapu et al. examined the feasibility of new high-performance CNT flexible fiber materials combined with new technologies for passive and active dust removal systems. The integration of EDS active and WFM coating passive technologies into the outer fabric of spacesuits has been achieved (Figure 10c) [62]. The EDS active technique employs electrostatic and dielectric swimming forces to generate an electric field, thereby carrying dust particles away from the surface. Conversely, the WFM passive technique is designed to minimize electrostatic adhesion by altering the chemistry of the dust-exposed surfaces to match the work function of the spacesuit exterior to the lunar dust. This property renders it more difficult for lunar dust to adhere to the surface of the device. Subsequent static experiments on specimens demonstrated that the static experimental system was able to repel 80% to 95% of the static-adherent dust (Figure 10d).

6.2. Technical Challenges and Prospects

Active–passive synergistic protection against lunar dust faces several key challenges that currently limit its practical implementation. First, technology compatibility and synergistic mechanisms remain insufficiently understood. Active methods such as electric field-based dust removal rely on charge manipulation, while passive approaches such as superhydrophobic coatings alter surface chemistry and charge distribution, potentially attenuating electrostatic effects. At present, systematic experimental validation and co-design guidelines for achieving effective synergy between these technologies are still lacking.

Second, energy constraints and long-term stability pose significant challenges. Active protection techniques typically require external power, while lunar missions operate under strict energy limitations and high storage costs. Achieving an optimal balance between the low energy consumption of passive coatings and the intermittent operation of active systems—such as low-power electric field repulsion integrated with passive shielding—remains a critical issue for long-duration missions.

Third, environmental adaptability and material durability must be addressed. The lunar surface environment, characterized by high vacuum, extreme thermal cycling, and radiation exposure, can degrade both passive coatings and active electronic components. Passive surfaces may lose functionality under radiation, while active systems are vulnerable to temperature-induced failures, highlighting the need for materials and devices specifically designed for extreme environments.