Abstract

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are increasingly deployed across diverse domains. Many applications demand a high degree of automation, supported by reliable Conflict Detection and Resolution (CD&R) and Collision Avoidance (CA) systems. At the same time, public mistrust, safety and privacy concerns, the presence of uncooperative airspace users, and rising traffic density are increasing research interest toward decentralized concepts such as free flight, in which each actor is responsible for its own safe trajectory. This survey reviews CD&R and CA methods with a particular focus on decentralized automation. It analyzes qualitatively classical rule-based approaches and their limitations, then examines machine learning (ML)-based techniques that aim to improve adaptability in complex environments. Building on recent regulatory discussions, it further considers how requirements for trust, transparency, explainability, and interpretability evolve with the degree of human oversight and autonomy, addressing gaps left by prior surveys.

1. Introduction

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have become a pivotal technology across diverse domains. Shakhatreh et al. [1] curated a survey categorizing UAV applications into distinct classes, including precision agriculture, search and rescue, infrastructure monitoring, and delivery of goods. To maximize their effectiveness, most of these applications require a high degree of automation—whether they are being used in fully automated missions, remotely piloted operations with decision-support systems, or hybrid approaches that combine human and machine control.

However, the adoption of automation in UAV operations has raised significant public mistrust. Safety concerns [2] and privacy issues [3] are frequently cited. Tam [4] conducted a survey on public trust in autonomous UAVs for transporting people and goods, revealing that the vast majority of respondents would only accept autonomous aerial transport of people if a pilot were onboard to override the autopilot when necessary. This finding underscores that public acceptance of UAV operations is closely tied to perceptions of human oversight and safety assurance.

At the same time, the potential for non-cooperative or unpredictable behavior from other airspace users, combined with increasing traffic density, complicates the deployment of large-scale automated UAV systems. These challenges have increased research interest in decentralized solutions such as Free Flight [5,6], in which each actor is responsible for planning its trajectory and for maintaining safe separation with other traffic, while centralized control has only a supervisory role. Enabling such a paradigm requires robust Conflict Detection and Resolution (CD&R) and Collision Avoidance (CA) technologies.

In this context, it is important to distinguish between CD&R and CA, which address different safety layers and operate across different time horizons. A conflict refers to a predicted loss of the prescribed separation minimum within a finite look-ahead horizon. CD&R aims to detect such situations in advance and to generate maneuvers that restore or maintain safe separation, and may be implemented either centrally (e.g., by Air Traffic Control) or onboard, depending on the operational paradigm.

CA, by contrast, is activated when separation margins are critically reduced and the risk of collision becomes imminent. CA operates on short time scales, relies on reactive maneuvers, and is always managed by the pilot or onboard automation, independent of ground-based control. In decentralized traffic management concepts, CA therefore acts as a last-resort safety layer, complementing CD&R mechanisms that seek to prevent conflicts from arising in the first place.

1.1. New Machine Learning Approaches and Their Challenges

Recent research suggests that traditional rule-based approaches may be insufficient for managing the complexity of future UAV operations. The combination of uncooperative intruders, traffic growth, and the shift toward decentralized management highlights the need for more adaptable methods for CD&R and CA. Because uncooperative intruders do not share intent information, their behavior is inherently unpredictable. This makes CD&R and CA in high traffic especially challenging, and motivates the exploration of machine learning (ML) approaches that can adapt to diverse encounter scenarios. As stated in [7], ML algorithms offer superior adaptability to complex and novel situations. Unlike hand-crafted systems, they can leverage past experience with the environment rather than relying exclusively on manually coded features, thereby increasing their potential efficacy.

Nevertheless, the use of ML introduces new challenges. By their nature, ML algorithms often operate as black-boxes, making it difficult to ensure predictable and certifiable behavior. This opacity complicates safety assurance, as it becomes harder to anticipate how the system will react under all possible operating conditions. Furthermore, increasing reliance on opaque algorithms runs counter to public expectations of keeping a human in the loop. As UAV systems become more intelligent yet less transparent, sustaining human oversight and fostering public trust become even more difficult.

To reconcile the benefits of ML with the safety and trustworthiness required in aviation, the concepts of transparency, explainability, and interpretability have become paramount. Although sometimes used interchangeably, these terms describe distinct properties:

- Transparency in ML-based systems can be achieved by providing open and accessible information about the model—its architecture, training data, and assumptions. Alternatively, ML can be used as an optimization layer atop transparent rule-based algorithms. An example of this hybrid strategy is presented in [7], where a reinforcement learning agent is combined with a rule-based controller.

- Explainability focuses on understanding how trained models, often neural networks, reach their decisions. Post hoc explanation frameworks such as SHAP [8], LIME [9], and Deep SHAP [10] are commonly applied to provide interpretable insights into complex models.

- Interpretability refers to the degree to which an artificial intelligence (AI) system’s outputs can be directly comprehended and logically assessed by a human observer; while not clearly defined, it generally emphasizes simplicity and clarity. For instance, Q-learning [11] can be considered interpretable due to its straightforward policy representation.

Discussions are still ongoing on how these requirements should be formalized for aviation. The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), in its recent report [12], defines a roadmap for AI integration in aviation. The correspondent concept paper [13] outlined preliminary requirements for the integration of AI-based systems into the airspace. Concepts such as human-in-the-loop operation and explainability are presented as foundational principles for certification and acceptance.

1.2. Related Work

Table 1 provides a comparative overview with related work found in the literature. As can be seen, prior works have focused primarily on cooperative and centralized traffic management [14], or have examined explainability without considering it through the lens of airborne autonomy [15,16]; while Rahman et al. [17] focus on ML techniques for UAV detection and classification, Lu et al. [18] give insights in non-cooperative CA techniques for micro aerial vehicles. Bello et al. [19] address the topic of certification of AI-based autonomous systems in aviation. However, CD&R and CA systems are not their focus, and CD is referenced only as an example. This paper presents a survey which addresses the limitations of prior surveys and places attention on CD&R and CA methods both for cooperative and non-cooperative traffic, with a particular focus on detection and avoidance under decentralized automation regime. This analysis motivates the discussion on integrating ML-based CD&R and CA into safety-critical aviation: how trust, transparency, and assurance requirements scale with autonomy and human oversight, and how certification-oriented engineering practices (including runtime monitoring, fallback behaviors, and benchmarked evaluation) shape feasible design choices.

Table 1.

Summary of related work compared with our paper. CD: Conflict Detection; CR: Conflict Resolution; CA: Collision Avoidance.

The remainder of this survey focuses on the sensor and algorithmic components for CD&R and CA in decentralized UAV operations. Following a brief discussion of the Free Flight paradigm and its relevance to Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) scenarios, the paper is organized by safety function. For each function—conflict detection, reasoning and alerting, and CA—classical algorithmic approaches are first reviewed to establish the foundational methods and their known limitations. ML-based techniques are then examined as potential extensions to these approaches, with particular emphasis on their applicability to dense and uncertain traffic environments. The paper concludes with a dedicated discussion of cross-cutting challenges related to safety assurance, certification, and trustworthy deployment of ML-based methods in safety-critical autonomous systems.

2. Free Flight and Autonomy

Free Flight is a concept originally introduced in Air Traffic Management (ATM) as a conceptual paradigm exploring a shift from centralized control toward increased decentralized decision making. Its goal is to enable pilots or onboard automation to optimize aircraft trajectories—across route, altitude, and timing dimensions—based on real-time information such as weather, traffic, fuel efficiency, and performance constraints, potentially including airborne self-separation assurance. Advocates of this approach highlight its potential to reduce delays and emissions while improving overall system performance in response to anticipated growth in air traffic demand [20].

It is important to distinguish this concept from Free Routing, which primarily concerns airspace design rather than control allocation. Free Routing removes the requirement to follow predefined airways, allowing aircraft to plan user-preferred paths between defined entry and exit points, while separation assurance and conflict resolution remain centrally managed. As such, Free Routing can be implemented within fully centralized ATM or Unmanned aircraft system Traffic Management (UTM) architectures and does not, by itself, imply decentralized decision making.

In the AAM scenarios considered in this paper—where large number of manned and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles share low-altitude airspace—the number of operators is expected to increase dramatically, far exceeding that of conventional aviation [21]. This trend has sparked interest in decentralized strategies that shift trajectory optimization and separation assurance to pilots or autonomous systems.

Centralized traffic management frameworks, such as UTM and U-space, represent a well-established approach to managing unmanned and highly automated air traffic through centralized trajectory approval, strategic deconfliction, and airspace constraint management. These systems offer clear advantages in terms of global situational awareness, regulatory oversight, and predictable behavior, and are particularly effective in low–medium-density operations or in environments with limited onboard autonomy.

However, several studies have highlighted scalability and responsiveness challenges associated with purely centralized traffic management approaches as traffic density, autonomy levels, and system heterogeneity increase. In dense, dynamic low-altitude airspace, high communication loads, stringent latency requirements, and the need for frequent trajectory re-optimization can limit the feasibility of centralized tactical separation. To address these challenges, many UTM and U-space concepts already assume a degree of onboard responsibility for safety, including tactical conflict detection and CA, particularly as a last-resort safety layer.

Alternative mitigation strategies have also been proposed, such as the introduction of structured airspace elements (e.g., air corridors) to reduce traffic complexity and facilitate centralized control. As noted in [22], while such structures can simplify coordination, they may also introduce bottlenecks that limit scalability under high-demand conditions.

This paper does not argue against centralized traffic management, but instead focuses on decentralized trajectory management and airborne self-separation assurance as a complementary and, in high-density AAM scenarios, potentially indispensable component of the overall system architecture. The emphasis on CD&R and CA reflects the scope of this review and their critical role in maintaining safety when centralized control is limited to strategic or supervisory functions, or when communication or coordination with a central authority is degraded.

Notable examples of this technology include the Detect and Avoid Alerting Logic for Unmanned Systems approach (DAIDALUS) [23] and the Airborne Collision Avoidance System (ACAS) Xu [24]. DAIDALUS, developed by NASA, serves as a reference implementation for RTCA DO-365 [25] compliance, providing alerting logic and maneuver guidance to remain collision-free. ACAS Xu, part of the ACAS X family, integrates both CD&R and CA functions through probabilistic decision-making models, offering a certifiable solution for unmanned aircraft systems in shared airspace.

The following chapter breaks down CD, CR, and CA into their core sub-functions and analyzes algorithmic solutions for each, including an overview of the latest ML-based approaches.

3. Conflict Detection, Resolution, and Collision Avoidance: Classical and AI-Based Approaches

This chapter examines the algorithmic pipeline that supports decentralized, Free Flight autonomy for UAVs, encompassing processes from initial sensing to last-resort avoidance maneuvers. Within this framework, the system integrates sensing, reasoning, and avoidance functions to enable autonomous detection, assessment, and mitigation of collision risks. The process begins with cooperative and non-cooperative sensing to detect various types of hazards, such as traffic, terrain, or weather. It then proceeds through reasoning and alerting for intruder identification and threat assessment, and culminates in avoidance maneuvers that guide the UAV to execute a computed evasive action.

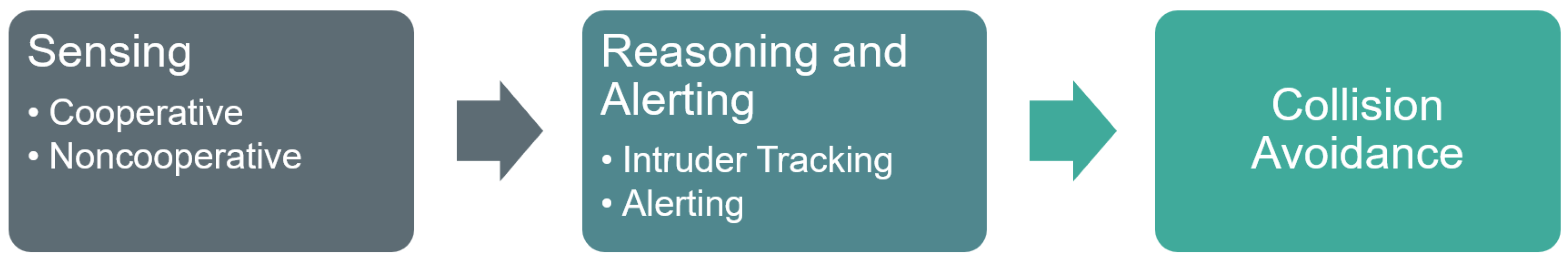

Building on established taxonomies [26], and as illustrated in Figure 1, these processes are grouped into three main functional blocks: detection, reasoning and alerting, and avoidance. The detection block corresponds to the sensing or detect function, while the reasoning and alerting block encompasses the track, evaluate, prioritize, and declare sub-functions. Finally, the avoidance block incorporates the remaining sub-functions responsible for determining and executing the appropriate evasive maneuver.

Figure 1.

Sensors and algorithms over the whole pipeline for CD&R and CA.

3.1. Sensing

The following subsections review sensing modalities and detection techniques for identifying cooperative and non-cooperative intruders. We first summarize the sensor types considered in this survey and their operational constraints, and then survey representative classical and learning-based intruder detection methods for each modality.

3.1.1. Sensor Types

The suitability of specific sensors varies according to whether the detection task involves a cooperative or non-cooperative intruder. In comparison with non-cooperative intruders, cooperative intruders are aerial objects that actively participate in their own detection in accordance with current aviation standards. This information can be supplied through specific signals by equipped transponders, such as Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast (ADS-B). This technology relies on GNSS-derived data to broadcast information such as position, ground speed, track angle, vertical rate, and timestamp over an RF channel. Such systems allow air vehicles to receive continuous and precise traffic information of surrounding aircraft. However, current ADS-B implementations typically lack encryption and authentication, making them sensitive to intentional interference and intrusion, such as spoofing, jamming, or message injection. Furthermore, in scenarios where manned and unmanned aircraft share low-altitude airspace, potential intruders are not equipped with transponders. To address these limitations and extend detection capabilities to non-cooperative intruders, alternative sensing technologies must be integrated to provide robust detection of uncooperative conflicts.

Radar is a widely used active sensing technology for intruder detection due to its capability to operate in various weather and lighting conditions. Radars work by transmitting electromagnetic pulses and analyzing the time delay, Doppler shift, and amplitude of the reflected signals. Range resolution is determined by the transmitted pulse bandwidth. Angular resolution depends on antenna aperture and beamforming method. While radar offers long detection ranges to several kilometers and simultaneous multi-target tracking, its performance can be degraded by clutter, precipitation, or limited scanning coverage, which imposes trade-offs between Field of View (FoV) and update rate.

Thermal (IR) sensors detect emitted radiation in the long-wave infrared (IR) spectrum, providing low-light and night-time detection capability. Compared to visual cameras, thermal sensors have a lower angular resolution. Furthermore, the effectiveness of these sensors depends strongly on temperature contrast and atmospheric absorption, although their comparatively low data rates reduce onboard computational load.

Vision sensors are passive systems that extract information from visible light to perform object detection, classification, and tracking. They offer high spatial and angular resolution, which depends on sensor size, and lens optics. Wider FoVs reduce pixel density and effective operation range. High-resolution images produce substantial data rates that require efficient onboard processing. Vision systems are highly sensitive to environmental factors, such as illumination variations, glare, shadows, rain, or fog, which can reduce detection accuracy or cause false alarms.

LiDAR sensors emit laser light to illuminate their surrounding and analyze the reflected pulses to measure distances. This allows practitioners to localize objects in 3D and its usage in low-light conditions. Moreover, it offers a wide FoV up to 360° coverage. Nevertheless, this sensor type produces large amounts of data and it remains expensive, despite the growing availability of more affordable models. In addition, smaller sensors are constrained by limited range, and their performance can degrade under adverse weather conditions.

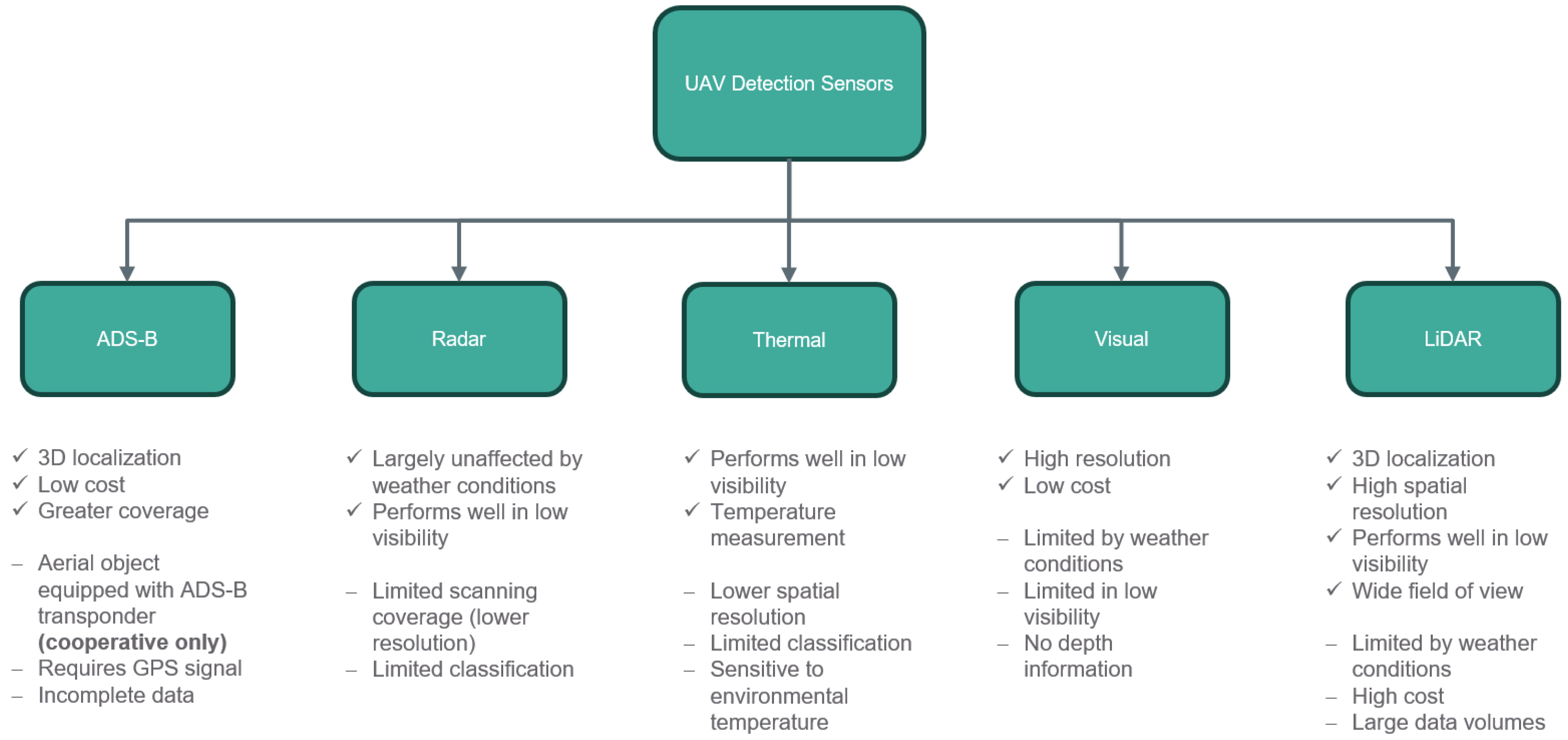

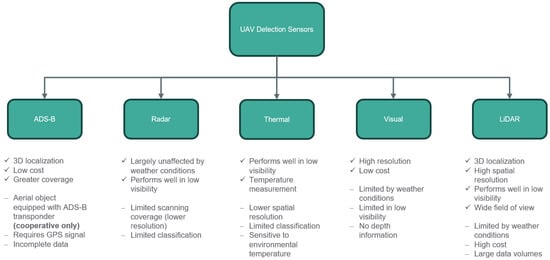

Each sensor type exhibits inherent limitations, summarized in Figure 2, which has resulted in relatively limited research on single-sensor approaches within this field. For instance, Aldao et al. [27] investigate an LiDAR-based system, while Corucci et al. [28] present a radar-based solution. However, no single technology can currently provide accurate, continuous, and robust information on all airspace participants.

Figure 2.

Overview of five sensor types for aerial object detection and their corresponding advantages and disadvantages.

This shortfall is most critical for non-cooperative intruders, where surveillance must rely on physical sensing rather than a received broadcast track. The Alliance for System Safety of UAS through Research Excellence (ASSURE) [29] emphasizes that non-cooperative CD&R and CA performance is frequently dominated by system-level factors—achievable detection range and field of regard/FoV (surveillance volume), false-alarm/false-track burden in cluttered backgrounds, and size/weight/power (SWaP) constraints—so detector performance (classical or ML) must be interpreted together with these operational limits.

These constraints motivate the development of multi-sensor systems, in which complementary sensing technologies are combined to improve detection robustness and coverage. Architecturally, intruder detection can be implemented (i) using airborne sensors only, (ii) through cooperative sensing that combines airborne and ground-based sensors, or (iii) via a ground-only sensing approach.

Much of the literature therefore investigates multi-sensor DAA systems, commonly combining optical, IR, and radar modalities. Fasano et al. [30,31] propose a DAA system composed of pulsed Ka-band radars together with optical and IR cameras. Similarly, Salazar et al. [32] propose a fixed-wing UAV DAA system using LADAR, a millimeter-wave (MMW) radar, and optical and IR cameras. De Haag et al. [33] discuss integrating LiDAR in DAA systems, while Lyu et al. [34] combine LiDAR with stereo cameras.

For mixed airborne/ground architectures, Coraluppi et al. [35,36] describe distributed detection using diverse airborne and ground-based sensors, whereas Stamm et al. [37] focus on DAA supported by distributed ground-based radars. Table 2 summarizes the sensor technologies surveyed. To support system-level interpretation across modalities, Table 3 summarizes typical operating-range tendencies, LoS/environment sensitivities, update/latency drivers, and processing burden for classical versus learning-based detection pipelines. The categories are intentionally qualitative because these quantities depend strongly on sensor configuration, platform constraints (SWaP), and scenario definition; the matrix is therefore meant to orient the reader rather than to provide a normalized performance comparison.

Table 2.

Sensor technologies classified by sensor types and sensor position.

Table 3.

Qualitative modality-and-pipeline matrix for aerial detection. Categories summarize typical operating constraints and reporting practices (range/LoS and environment sensitivity, update/latency drivers, and processing/false-alarm handling) for both classical and ML pipelines; they are not intended as normalized performance benchmarks.

3.1.2. Classical Approaches for Detection

Based on these sensor characteristics and operating principles, numerous algorithms have been proposed in the literature for detecting intruders in the airspace using sensor data. Each algorithm is tailored to a specific sensing modality and exploits the particular characteristics and functioning of the sensor for which it is designed.

For ADS-B, research focuses on data validation—flagging intrusions and anomalies without modifying the ADS-B protocol itself to avoid costly changes. Early work by Kacem et al. [38] combined lightweight cryptography with flight path modeling to verify message authenticity and plausibility with negligible overhead. Leonardi et al. [39] instead used RF fingerprinting to extract transmitter-specific features from ADS-B signals, distinguishing legitimate from spoofed messages (reporting detection rates up to 85% with low-cost receivers). Ray et al. [40] propose a cosine-similarity method to detect replay attacks in large SDR datasets, successfully identifying single, swarm, and staggered scenarios.

Radar target detection typically relies on Constant False Alarm Rate (CFAR) processing [41]. CFAR adaptively sets detection thresholds—often via sliding-window estimates of background statistics—to maintain a specified false-alarm probability; common variants include Cell-Averaging CFAR (CA-CFAR), Ordered Statistics CFAR (OS-CFAR), Greatest-Of CFAR (GO-CFAR), and related schemes. Recent work refines CFAR for real-time, cluttered settings. Sim et al. [42] for instance, present an FPGA-optimized CFAR for airborne radars, sustaining high detection performance under load. Complementarily, Safa et al. [43] introduce a low-complexity nonlinear detector (kernel-inspired, correlation-based) that replaces the statistical modeling step in classical CFAR, outperforming OS-CFAR for indoor drone obstacle avoidance where dense multipath/clutter degrades CFAR. Beyond CFAR, Doppler and micro-Doppler methods exploit target motion for the detection [44]. Regardless of the specific detector, low–slow–small (LSS) UAVs remain challenging to detect with a radar sensor. Classical CFAR schemes struggle to reliably detect targets with low Radar Cross Section (RCS), while Doppler-based methods have difficulties with slow-moving objects. To address these algorithmic limitations, Shao et al. [45] reformulate and retune a classical CFAR-based processing chain to improve LSS detection in complex outdoor environments.

For thermal (IR) sensors, small-target detection is often based on simple intensity thresholding. However, this becomes challenging in low-resolution imagery, where targets occupy only a few pixels and their contrast against clutter is low. To address this, Jakubowicz et al. [46] propose a statistical framework for detecting aircraft in very low-resolution IR images () that combines sensitivity analysis of simulated IR signatures, quasi–Monte Carlo sampling of uncertain conditions, and detection tests based on level sets and total variation. Experiments on 90,000 simulated images show that these level-set-based statistics significantly outperform classical mean- and max-intensity detectors, particularly under realistic cloudy-sky backgrounds modeled as fractional Brownian noise. Complementary to this, Qi et al. [47] formulate IR small-target detection as a saliency problem and exploit the fact that point-like targets appear as isotropic Gaussian-like spots whereas background clutter is locally oriented. They use a second-order directional derivative filter to build directional channels, apply phase-spectrum-based saliency detection, and fuse the resulting maps into a high–signal-to-clutter “target-saliency” map from which targets are extracted by a simple threshold, achieving higher SCR gain and better Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) performance in comparison with several classical filters on real IR imagery with complex backgrounds.

For visual sensors, target detection is usually performed from image sequences from which appearance cues (e.g., shape, texture, apparent size) are extracted to localize obstacles and support trajectory prediction, thereby extending situational awareness. High target speed, agile maneuvers, cluttered backgrounds, and changing illumination remain key challenges, especially for reliably distinguishing cooperative from non-cooperative aircraft at useful ranges. Optical flow is a classical approach for vision-based CA; Chao et al. [48] compared motion models that use flow for UAV navigation. However, standard optical-flow methods are insensitive to objects approaching head-on, as such motion induces little lateral displacement in the image. Mori et al. [49] mitigate this by combining Sped-Up Robust Feature (SURF) feature matching and template matching across frames to track relative size changes, enabling distance estimation to frontal obstacles. Mejías et al. [50] proposed a classical vision-based sense-and-avoid pipeline that combines morphological spatial filtering with a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) temporal filter to detect and track small, low-contrast aircraft above the horizon, estimating the target’s bearing and elevation as inputs to a CA control strategy. This work was extended by Molloy et al. [51] to the more challenging below-horizon case by adding image registration and gradient subtraction, while retaining HMM-based temporal filtering to robustly detect intruding aircraft amid structured ground clutter. Another noteworthy study is presented by Dolph et al. [52], where several classical computer-vision pipelines for intruder detection—including SURF feature matching, optical-flow tracking, Feature from Accelerated Segment Test (FAST)-based frame differencing, and Gaussian-mixture background modeling—are systematically evaluated, providing insight into their practical performance and limitations for long-range visual DAA.

LiDAR sensors deliver accurate distance measurements and 3D data that help differentiate tiny, fast-moving objects such as drones from other aerial targets through their motion and size patterns by analyzing and interpreting the point cloud data. Therefore, classical approaches focusing on point cloud clustering techniques to detect objects of interest. Aldao et al. [27] used a Second-Order Cone Program (SOCP) to detect intruders and estimate their motion. Based on this information, avoidance trajectories are computed in real time. Dewan et al. [53] used Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) [54] to estimate motion cues combined with a Bayesian approach to detect dynamic objects. Their approach effectively addresses the challenges posed by partial observations and occlusions. Lu et al. [55] used Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (DBSCAN) to make a first clustering step followed by an additional geometric segmentation method for dynamic objects by using an adaptive covariance Kalman filter. Their learning free technique enables real-time tracking and CA onboard; while DBSCAN is good for uniform point cloud density, it shows weaknesses when segment obstacles with low density. Zheng et al. [56] try to overcome this limitation by developing a new clustering method: Clustering algorithm Based on Relative Distance and Density (CBRDD).

Classical techniques, unlike ML approaches, require no training and therefore do not rely on the large datasets typically needed to develop ML models. Nevertheless, across the sensor modalities considered here, purely classical (non-AI) detection pipelines are increasingly being supplanted—at different rates depending on the sensing modality—by learning-based methods in modern systems. The main driver is that ML can mitigate limitations that are difficult to overcome with hand-crafted logic: ADS-B validation remains constrained to cooperative participants and largely rule-/threshold-driven; radar detection/classification can benefit from learned Range–Doppler (R-D) or micro-Doppler features but remains bounded by SNR/RCS and coverage constraints; IR and visual pipelines can be brittle under low contrast, clutter, and changing conditions where learning-based detectors can learn context-dependent suppression and invariance, albeit with sensitivity to domain shift; and LiDAR clustering/segmentation degrades with sparse returns and partial views where learning-based 3D perception can exploit learned shape/motion priors at higher compute and data cost.

The next subsection describes a survey of ML approaches for detection.

3.1.3. Machine Learning Approaches for Detection

AI-based methods in this field have advanced rapidly in recent years. Deep learning approaches, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), consistently outperform traditional techniques by handling complex scenarios, diverse object appearances, and dynamic environments where classical algorithms often struggle.

Real-time performance is equally critical, and many approaches rely on You Only Look Once (YOLO) detectors [57] for their strong accuracy–speed balance. Beyond CNN-based architectures, transformer-based models have also gained prominence. Detection Transformer (DETR) [58] introduced an anchor-free, end-to-end paradigm that models images as sequences of patches, integrates global context, and directly predicts bounding boxes and categories—eliminating anchor boxes and non-maximum suppression (NMS). Although later variants improve efficiency, they still fall short of real-time requirements for UAV operations. Roboflow-DETR (RF-DETR) [59] addresses this limitation through a hybrid encoder and Intersection over Union (IoU)-aware queries, establishing the first real-time end-to-end transformer detector. CNNs offer efficiency and maturity, transformers provide enhanced global context, and emerging foundation models leverage the strengths of both: they learn generalized, transferable representations, support multiple tasks, and can leverage massive unlabeled or weakly labeled datasets.

The number of available datasets for both single and multiple sensor configurations in the context of aerial object detection and tracking has grown in parallel with these methodological advancements, reflecting the increasing interest in AI-driven detection of aerial objects. In this regard, not only the volume of data but also its quality, representativeness, and fidelity to real-world conditions are critical, as they directly influence model performance, generalization, and robustness. To enable reliable pattern recognition and decision making, datasets must therefore provide both high-quality samples and sufficient variability while minimizing inherent biases. Table 4 shows a collection of available open source datasets recorded from different sensors to support ML-based aerial object detection from moving as well as stationary sensor setups.

Table 4.

Overview of examined datasets needed for ML approaches for detection.

The Airborne Object Tracking (AOT) dataset [60], published in 2021, contains nearly 5 k high-resolution grayscale flight sequences, resulting in over 5.9 M images with more than 3.3 M annotated airborne objects; it is one of the largest publicly available datasets in this area. Vrba et al. [61] created a dataset for UAV detection and segmentation in point clouds. It consists of 5.455 scans from two LiDAR types, containing three UAV types. To compensate for the weaknesses of a specific sensor type, multi-modal approaches are increasingly being developed as well as their corresponding datasets. Yuan et al. [62] published a multi-modal dataset containing 3D LiDAR, mmWave radar, and audio data. Patrikar et al. [63] published a dataset combining visual data with speech and ADS-B trajectory data while Svanström et al. [64] collected 90 audio clips, 365 IR, and 285 RGB videos. However, acquiring real-world recordings to generate datasets presents significant challenges due to the high time and cost requirements, as well as the difficulty of covering certain scenarios (e.g., collisions with specific objects like birds). To address these limitations, AI-supported data annotation and synthetic generated datasets serve as a valuable alternative, while the first technique decreases time and manual annotation effort, the latter one enables the generation and validation of initial hypotheses using the developed methodologies in the absence of real data. The UAVDB dataset [65] combined bounding box annotations with predictions of the foundation model Segment Anything Model 2 (SAM2) to generate high-quality masks for instance segmentation. Lenhard et al. [66] published SynDroneVision, an RGB-based drone detection dataset, for surveillance applications containing diverse backgrounds, lighting conditions, and drone models. In contrast to the previous Aldao et al. [67] developed an LiDAR simulator to generate realistic point clouds of UAVs. After reviewing the current data landscape and briefly examining techniques to address missing data, the discussion now turns to potential ML applications that require such datasets to train and fine-tune the AI models. In the following paragraphs, AI approaches are discussed for each sensor.

For ADS-B, research focuses on different AI-supported prediction approaches, which are useful in identifying abnormal flight behavior or other safety-critical anomalies. Shafienya et al. [68] developed a CNN model with Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) deep model structure to predict 4D flight trajectories for long-term flight trajectory planning; while the CNN part is used for spatial feature extraction, GRU extracts temporal features. The TTSAD model [69] is focusing on detecting anomalies in ADS-B data by first predicting temporal correlations in ADS-B signals and further applying a reconstruction module to capture contextual dependencies. Finally, the reconstruction differences are predicted to determine anomalies. Ahmed et al. [70] introduced a deep learning architecture using TabNet, NODE, and DeepGBM models to classify ADS-B messages and detect attack types, achieving up to 98% accuracy in identifying anomalies. Similarly, Ngamboé et al. [71] developed an intrusion detection system based on extended Long Short-Term Memory (xLSTM) that outperforms transformer-based models for detecting subtle attacks, with an F1-score of 98.9%.

With radar sensors, the velocity and range of airborne targets can be derived. Zhao et al. [72] focused on target and clutter classification by applying a new GAN-CNN-based detection method. By combining GAN and CNN architectures they are able to locate the target in multidimensional space of range, velocity, and angle-of-arrival. Wang et al. [73] presented a CNN-based method for the detection of UAVs in the airspace with a Pulse–Doppler Radar sensor. The method consists of a CNN with two heads: a classifier to identify targets and a regressor that estimates the offset from the patch center. Their outputs are then processed by a NMS module that combines probability, density, and voting cues to suppress and control false alarms. Tests with simulated and real data showed that the proposed method outperformed the classical CFAR algorithm. Tm et al. [74] propose a CNN architecture to perform single shot target detection from R-D data of an airborne radar.

Thermal sensors pose challenges for AI detection methods because thermal noise, temperature fluctuations, and cluttered environments degrade signal clarity and consistency. To overcome these challenges, GM-DETR [75] provides a fine-grained context-aware fusion module to enhance semantic and texture features for IR detection of small UAV swarms combined with a long-term memory mechanism to further improve the robustness. Gutierrez et al. [76] compared popular detector architectures which are YOLOv9, GELAN, DETR, and ViTDet and showed that CNN-based detectors stands out for real-time detection speed while transformer-based models provide higher accuracies in varying and complex conditions.

For visual sensors, AI models are used for detection, supported by additional filtering and refinement processes. For instance, [77,78] used AI-based visual object detection. Arsenos et al. [79] used an adapted YOLOv5 model. Their approach allows practitioners to detect UAVs at distances of up to 145 m. Yu et al. [80] used YOLOv8 combined with an additional slicing approach to further increase detection accuracy of tiny objects. Approaches like [81] employed CenterTrack a tracking-by-detection method, resulting in a joint detector-tracker by representing objects as center points and modeling only the inter-frame distance offsets. Karampinis et al. [82] took the detection pipeline from [79]. They formulated the task as an image-to-image translation problem and employed a lightweight encoder–decoder network for depth estimation. Despite the current limitations of foundation models regarding processing speed, such models facilitate multi-task annotation generation while requiring minimal supervision as described in [83].

For LiDAR sensors, ML-models learn geometric properties of point clouds to identify and detect objects of interest. Key challenges include large differences in point cloud density and accuracy among LiDAR sensors, as well as motion distortion and real-time processing requirements. Xiao et al. [84] developed an approach based on two LiDAR sensors. The LiDAR 360 gives a 360° coverage while the Livox Avia provides focused 3D point cloud data for each timestamp. Objects of interest are identified by using a clustering-based learning detection approach (CL-Det). Afterwards, DBSCAN is used to further cluster the detected objects. By combining both sensors, they demonstrate the potential for real-time, precise UAV tracking in sparse data conditions. Zhange et al. [85] presented DeFlow, which employs GRU refinement to transition from voxel-based to point-based features. A novel loss function was developed that compensates the imbalance between static and dynamic points.

The field of AI-based object detection and tracking has made continuous progress in tackling challenges such as reliably tracking of very small aerial objects with unpredictable flight patterns. Key research directions include achieving real-time performance, modeling and uncertainty prediction, and effectively leveraging appearance information for robust tracking. Table 5 provides the summary of the presented classical and ML approaches for aerial object detection examined in this survey. Across modalities, the output of detection must ultimately be consolidated into consistent tracks and uncertainty estimates to support threat assessment and timely alerting, which motivates the reasoning and alerting functions discussed next.

Table 5.

Overview of examined approaches for aerial object detection divided into classical and ML-based techniques.

3.2. Reasoning and Alerting

The information provided by these different sensor systems must be processed to acquire a unique description of the environment around the own vehicle. The sensor detections must be analyzed to filter possible false positives. The tracks must be constantly and correctly updated to produce accurate and robust estimates, which are necessary to identify collision risks and to determine their level of threat.

3.2.1. Classical Approaches for Intruder Tracking

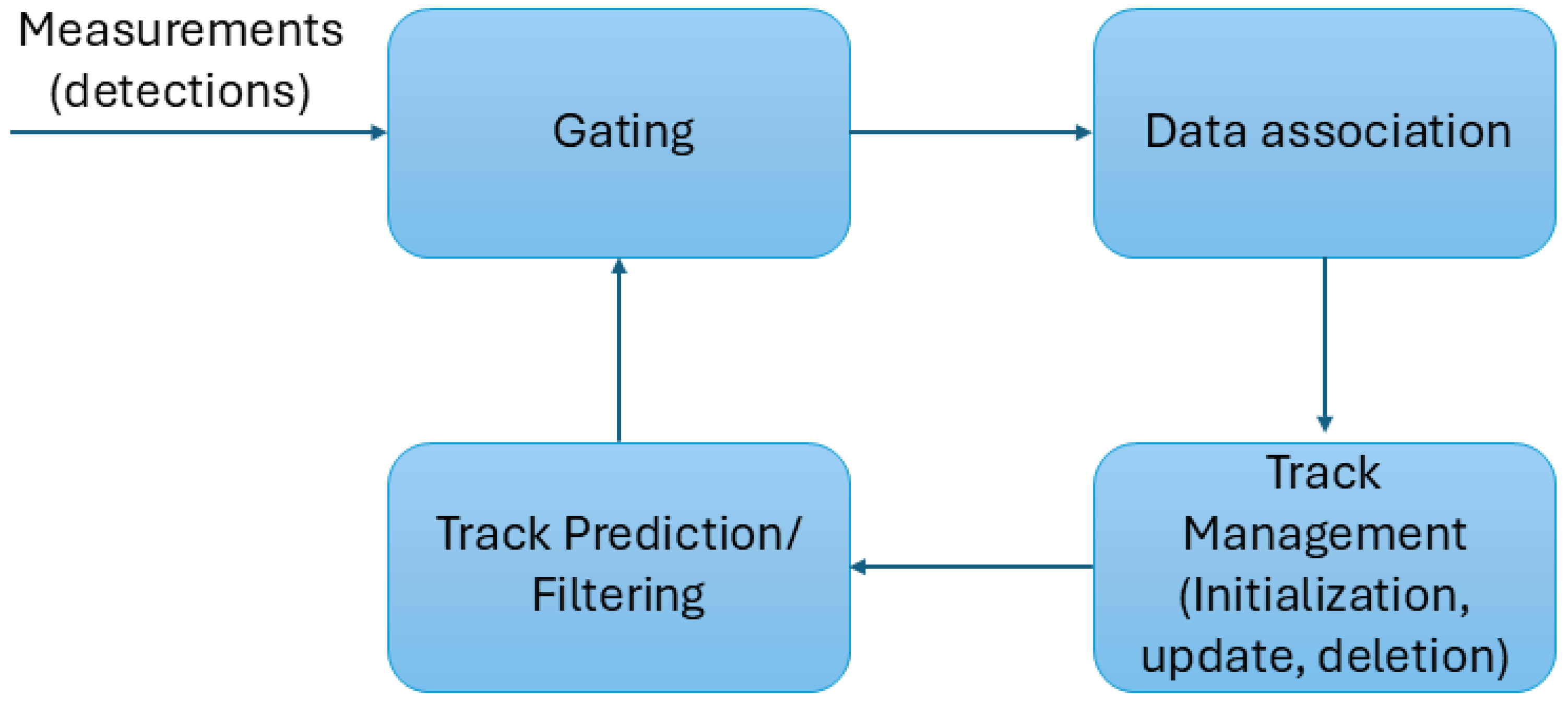

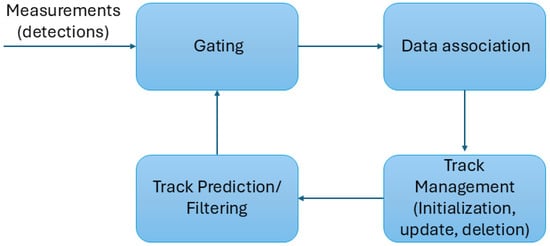

Tracking intruders in airspace using multiple sensor measurements can be formulated as a classical multi-target tracking problem. Figure 3 illustrates a standard multi-target tracking pipeline, including a gating step that pre-filters implausible measurement-to-track pairings before data association and state estimation. This multi-target tracking task is typically decomposed into two main components: observation-to-track association; state filtering and prediction.

Figure 3.

Generic multi-target tracking loop for observation-to-track association. Gating restricts candidate measurement–track pairings (often via ellipsoidal/Mahalanobis gating using the innovation covariance), after which an association rule assigns measurements to predicted tracks and track management performs the update, the initiation/confirmation, and the deletion. The gating threshold is application- and sensor-dependent and trades missed associations against false associations in clutter.

The observation-to-track association is a non-trivial problem in multi-target tracking, particularly in the presence of false detections within track gates, which can lead to misassociations and subsequent track degradation or loss [86].

A simple deterministic approach is the Nearest Neighbor (NN) method, in which each track is updated with the closest measurement. In multi-target settings, this can yield conflicting assignments across tracks and is therefore often replaced by Global Nearest Neighbor (GNN), which solves a joint assignment problem over all gated measurements and tracks. In both cases, the association likelihood is typically based on a distance metric between predicted track states and measurements.

When false positives and ambiguous gating become significant, probabilistic association schemes are commonly used. Probabilistic Data Association (PDA) and its multi-target extension Joint PDA (JPDA) weight multiple association hypotheses and account for the possibility that a measurement is clutter or belongs to another track. A particularly robust family of methods is Multiple Hypothesis Tracking (MHT), originally introduced by Reid [87], which maintains multiple association histories and defers commitment until sufficient evidence has accumulated; Blackman [88] discusses MHT in the data-to-track association context.

Concerning filtering and prediction, one of the most well-known and often-used algorithm is the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF). Another method is the Interactive Multiple Model (IMM) which, as described in [89], consists of several Kalman filters which work in parallel with the aim of corresponding to a target model. Another effective and robust algorithm is Particle Filtering, also called the sequential importance sampling algorithm. It is a Monte Carlo method that sequentially uses incoming measurements to maintain a set of particles distributed across the surveyed state space [90]. Each particle consists of a state and an associated weight, and it is interpreted as a state hypothesis. With a high number of particles and sum-normalized weights, their ensemble can be interpreted as a state-discrete approximation to the posterior probability density function of the true origin of a target that is causing the received detections.

Representative multi-sensor DAA implementations combine these building blocks into end-to-end pipelines that specify gating/association, filtering, and (when multiple sensors are used) fusion level. Fasano et al. in [30,31] use an ellipsoidal gating for track association followed by an EKF. The system developed by Salazar et al. in [32] use the Track-to-Track [91,92] algorithm to fuse the incoming data. As explained in the paper, this method combines estimates rather than measurements and it requires a Kalman Filter for every sensor source. Coraluppi in [35,36] make use of the MHT algorithm for the data association, followed by an EKF. In [89], Torelli et al. propose a joint approach between the MHT and the IMM algorithms, which they call IM3HT. Cornic et al. in [93] propose the use of the Mahalanobis distance [94] for the evaluation of the association of the detection to the tracks, in conjunction with the IMM algorithm for the fusion of radar and visual data.

Table 6 shows a summary of the surveyed intruder tracking methods.

Table 6.

Data association, filtering, and tracking algorithms for detect and avoid systems.

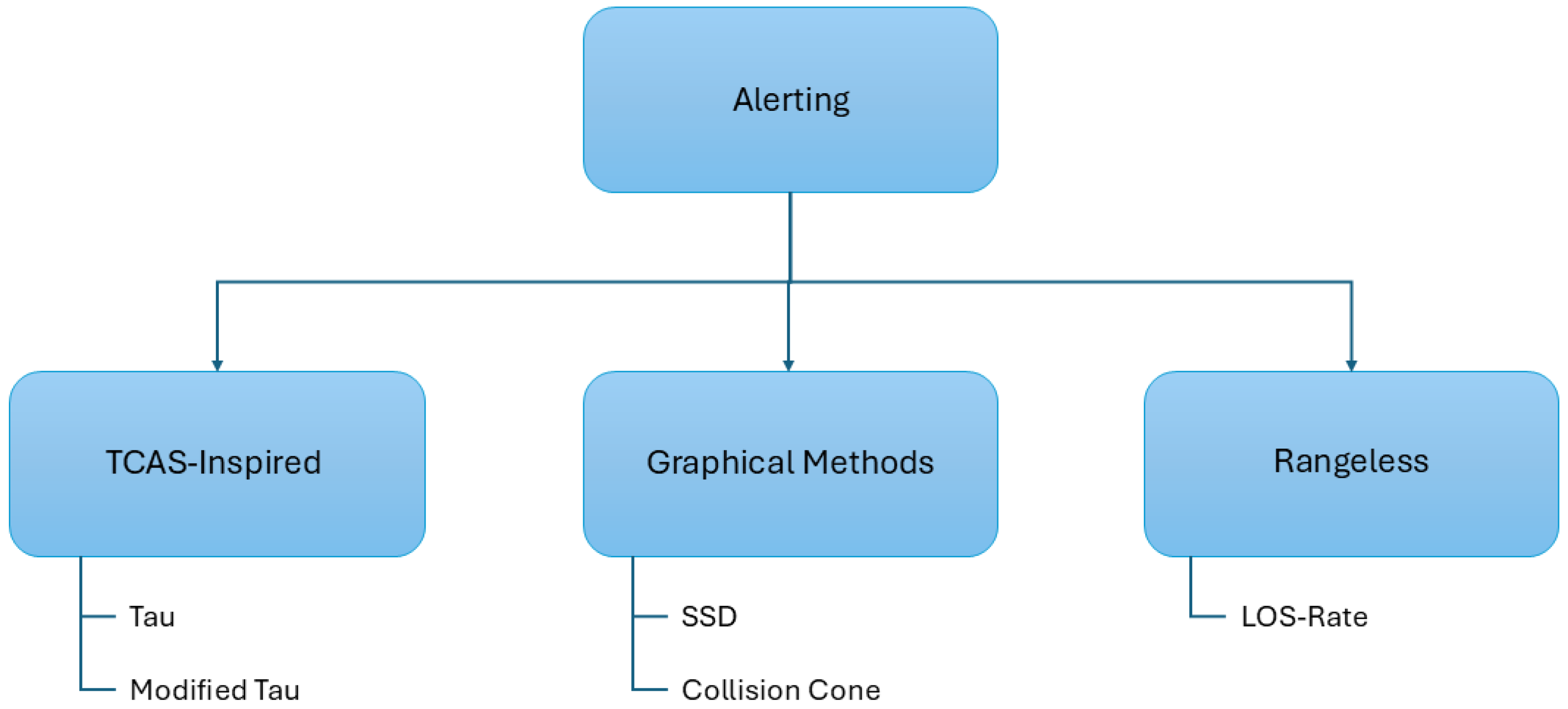

3.2.2. Classical Approaches for Alerting

The process of track update and filtering of false positives is followed by threat identification and alerting. In this context, it is useful to distinguish between evaluation and declaration. Evaluation computes continuous conflict risk quantities from estimated relative states (e.g., time-to-violation or time-to-closest-approach metrics, predicted loss of separation, or band/feasibility conflicts), whereas declaration maps these quantities to discrete alert states (e.g., preventive/corrective/warning) using thresholds and logic predicates, often augmented with hysteresis or persistence rules to avoid alert chattering. Accordingly, the classical literature surveyed below (e.g., Traffic CA Systems (TCAS)-inspired metrics and DAIDALUS violation predicates) largely covers the evaluate + declare stages, which then feed downstream guidance/avoidance. Because evaluation and declaration operate on estimated tracks, upstream integrity and robustness measures affect alerting primarily through track existence, state accuracy, and uncertainty. For cooperative surveillance, plausibility screening and validation reduce the likelihood that corrupted tracks propagate into separation metrics (reducing nuisance alerts), but overly conservative validation can delay declaration. For non-cooperative sensors, clutter-adaptive detection and temporal confirmation reduce spurious track initiation and stabilize estimates, shifting the false-positive/false-negative operating point of geometric and time-to-violation alerting logics. These interactions motivate certification-friendly mitigation such as track-quality scoring, corroboration requirements, temporal persistence, and conservative fallback behaviors under low-integrity conditions.

A widely used instantiation of this evaluate–declare process is based on the concepts of “Well Clear” (WC), “Remain Well Clear” (RWC) volume, and RWC function. As explained in [95], it is possible to define WC as a state for the aircraft, on whose loss it may depend the application of the right of way rule; while the RWC volume is defined as a separation minima, the violation of which determines a conflict. Finally, the purpose of a RWC function is to ensure that the RWC volume is never violated. A distinction must be made at this point between the RWC function and the CA. The first requires smoother maneuvers necessary to avoid loss of WC, whereas the latter is a last-resort maneuver to avoid collision.

ICAO defined these volumes by taking inspiration from the Separation Volumes of the TCAS equipped on manned aircraft and described in [96]. The dimensions of these volumes and the metric by which it is possible to foresee a loss of WC were though not indicated and have been an active field of research in recent years. As explained in [97] one of the concerns was about the interoperability with the TCAS systems. The RWC volumes need to be big enough to avoid triggering a Resolution Advisory (RA) from the TCAS.

The metrics for the detection of loss of separation used in the TCAS is based on the concept of tau, and on its variation, the modified tau. As explained in [98], tau is defined as follows:

In (1), r is the range between the two aircraft and is the range rate, i.e., the variation of the distance between the two aircraft in time. For low range rates, this parameter becomes inadequate to describe the conflict and ensure safe separation. For this reason, a modified version of this parameter, the modified tau, has been defined as follows:

In (2), is a range threshold which depends on the altitude. Vaidya et al. in [98] analyze, by means of simulations based on particle kinematics, and for different encounters, proving that the parameter (2) provides bigger separation at RA. During flight, the TCAS System considers the distance between the vehicles and compare the parameter with a threshold value that depends on the altitude. By stating the necessity to ensure interoperability between UAVs CD&R and CA Systems and TCAS, the study in [97] also highlighted the need for a complementary algorithm for the detection of conflict geometries which can cause a RA from the TCAS II. This complementary algorithm has been implemented based on the parameter and it is described in [99]. The presented method was then generalized in [100] by providing an algorithm for the identification of loss of WC, which could be used with different horizontal time variables. In addition to the aforementioned and parameters, the authors also considered the time to closest point of approach , i.e., the time in seconds to the minimum distance between the two aerial vehicles, and the time to the entry point, , i.e., the time at which the two vehicles will no longer be separated, considering and straight line vehicles trajectory. The authors in [100] also analyzed and compared the performance of this algorithm with these four parameters and proved that the algorithm is more conservative when is used as time variable. These works were the mathematical foundation of the DAIDALUS System, which was first introduced in [23]. To illustrate how these concepts are instantiated in a widely used WC framework, we briefly summarize the DAIDALUS WC violation predicates below. The DAIDALUS WC Logic is based on the following relations:

In (3) and (4), the terms and are the condition of, respectively, horizontal and vertical WC violation. The variables and are the relative position and velocity of the intruder, while and are the relative vertical position and velocity of the intruder. The values , T, , and are, respectively, the Horizontal Miss Distance, the threshold, the vertical distance, and the time threshold. Their values are application-dependent.

The DAIDALUS system was further extended in subsequent work, e.g., [101], which integrates dynamic WC volumes and explicit sensor-uncertainty mitigation. Uncertainty is handled via two complementary mechanisms: (i) a conservative approach based on horizontal uncertainty ellipses (with associated vertical bounds) computed from sensor-reported variances and covariances of position and velocity components, which are then propagated through the WC functions; (ii) a probability-bounds formulation that models the actual relative state as random variables and triggers detection/alerting when a provable upper bound on the probability of WC violation exceeds a configurable threshold.

Another noteworthy work concerning the interoperability between UAV CD&R and CA Systems and TCAS, Thipphavong et al. [102] described the tests made to define a collision volume where the vertical guidance of the UAV is restricted in order to avoid the issuance of a RA by the TCAS.

In multi-intruder encounters, classical alerting logic is commonly applied on a per-intruder basis (i.e., computing WC predicates and time-to-violation metrics for each tracked object) and then reduced to a single operational alert state by prioritization rules, such as selecting the intruder that yields the highest alert level and/or the minimum time-to-violation (with simple tie-breakers). This reduction is practical and certification-friendly, but it can become brittle in dense traffic due to rapid threat switching (“alert flapping”) and because pairwise prioritization may not reflect coupled multi-agent geometry. This limitation also motivates recent ML formulations that learn threat-ranking/aggregation functions (e.g., attention-based encoding used to select which intruder(s) to consider for avoidance), which can be interpreted as a learned counterpart to the classical prioritization stage in declare.

Another common method for assessing whether the ownership remains WC is the Solution Space Diagram (SSD). The method was first applied in ATM applications and has been developed to decrease the workload of Air Traffic Controller, as it is more readable and thus more easily interpretable than other methods. The first implementation of the method can be found in [103]. The method was then further developed in other works such as [104,105]. The determination of conflict with the SSD is based on geometric considerations. Considering the own aircraft and the intruder, the method considers the Protected Zone (PZ) of the intruder, represented as a circle of radius 5 NM centered on the intruders position. From the own vehicle position, the two tangents to the intruder PZ are drawn to identify the Forbidden Zone (FBZ), i.e., the space delimited by the tangents to the PZ. Based on this construction, it is possible to determine if there is a conflict between the two aircraft based on the position of the relative velocity with respect to the FBZ. More specifically, a violation of the PZ of the intruder, and consequently a conflict between the two aircraft, can be foreseen as long as the relative velocity between the aircraft lies in the FBZ.

Other alerting logics can also be defined for sensors which do not deliver a 3D information such as visual camera. Despite the lack of information, these kinds of sensors can be useful for the identification of non-cooperative intruders. As described in [78], it is possible to estimate/determine whether a detected object is a threat by analyzing the Line-of-Sight (LOS) rate. More specifically, considering the principle of proportional navigation—provided that the range rate is negative, i.e., that the two objects are becoming closer—they can be considered on a collision route if the LOS rate approaches 0. However, this method presents inherent difficulties. The first difficulty is the determination of an appropriate threshold to determine the conflict. Secondly, given the impossibility to determine the range rate only with visual cameras, it must always be supposed that the range rate is negative. These algorithms always consider the worst case, and thus give more alerts than they should.

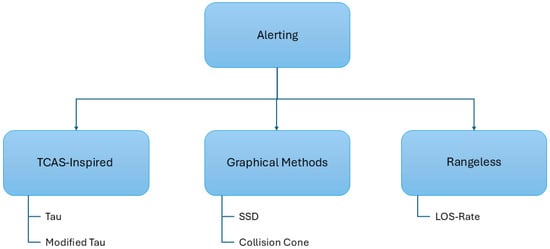

Figure 4 shows an explanatory diagram of the classification of alerting methods.

Figure 4.

Classification of alerting methods.

3.2.3. Machine Learning Approaches for Reasoning and Alerting

Building on the association, filtering, and declaration stages described above, ML is mainly explored as a way to learn components within the pipeline (e.g., measurement models, association scores, or threat-ranking/aggregation) rather than to replace WC definitions wholesale.

In classical CD&R and CA pipelines, tracking and alerting typically rely on model-based estimators (e.g., Kalman/IMM-style filters) and hand-designed association and threshold logic; while these components are interpretable, performance can degrade under model mismatch, non-Gaussian noise, missed detections, and dense multi-target scenes where data association becomes ambiguous.

Surveys by [106,107] review ML methods that can support these functions (e.g., fusion and association), including approaches based on CNNs, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), and k-means clustering. For example, Lin et al. [108] use a CNN with self-attention to fuse measurements from binocular vision, laser tracking, and depth cameras. To the best of our knowledge, however, while such approaches show substantial potential for multi-sensor intruder tracking and threat identification, they have not yet been explicitly studied in the CD&R and CA context considered here.

This gap is partly explained by assurance and certification constraints for safety-critical alerting/tracking functions, where predictable behavior and analyzable failure modes are often prioritized over purely data-driven optimization. The work most closely related is authored by Skinner et al. [109]. They studied the use of Bayesian Networks for the intent classification of aerial objects based on raw data coming from radar, visual and IR sensors. Another noticeable approach is attention networks. These networks are Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks which takes as input data about intruders and give a vector of fixed length with information about the intruder to consider for the avoidance. They are introduced in [110]. The CA agents described in [111,112] use these methods to decide which intruder must be considered for the avoidance. From a functional viewpoint, these attention mechanisms can be seen as implementing a learned multi-intruder prioritization stage that complements classical WC evaluation/declaration logic, particularly under high-traffic conditions. More generally, these representation learning approaches can be interpreted as a bridge between tracking and alerting: rather than replacing the WC logic itself, they aim to learn compact the encoding of multi-intruder scenes and threat ranking, reducing reliance on hand-crafted prioritization heuristics that may become brittle or unstable (e.g., frequent priority switching) in dense traffic.

3.3. Collision Avoidance

The following subsections review avoidance maneuver to resolve conflict and avoid collisions with cooperative and non-cooperative intruders.

3.3.1. Classical Approaches

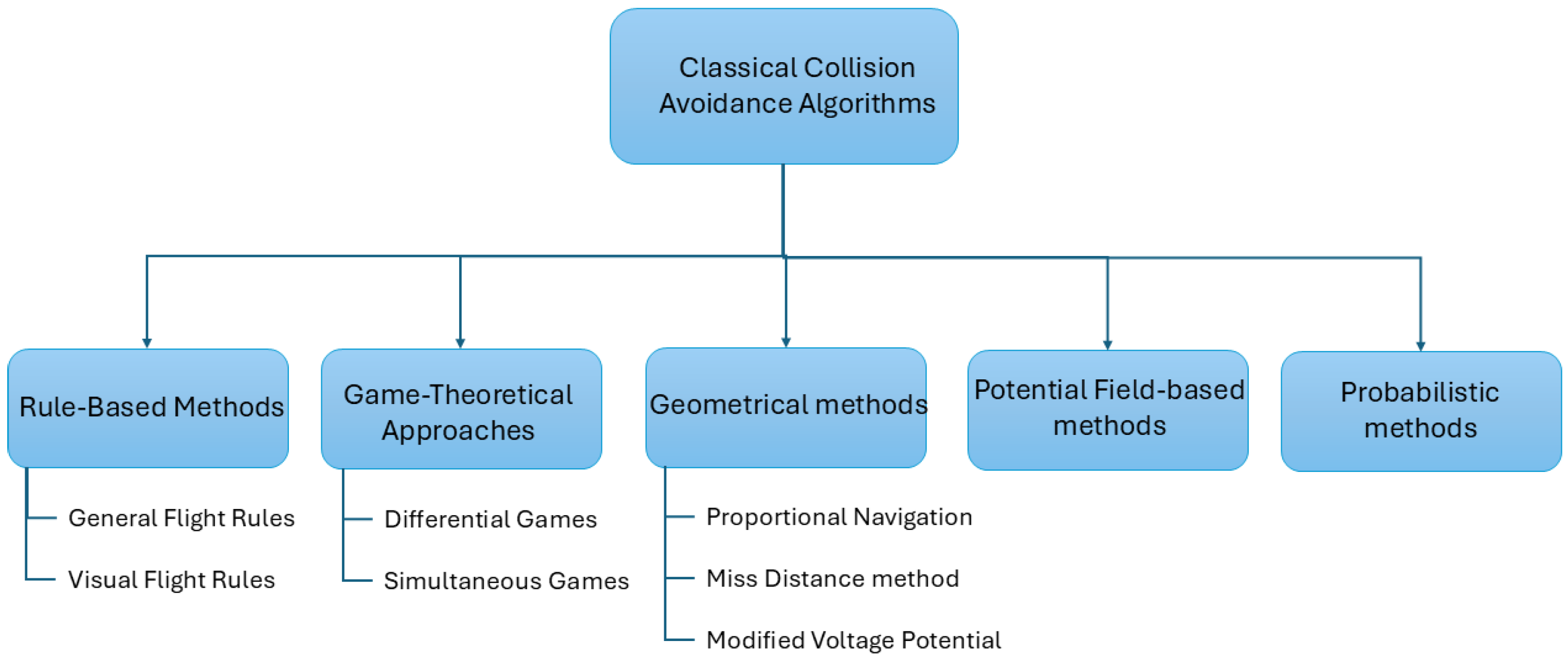

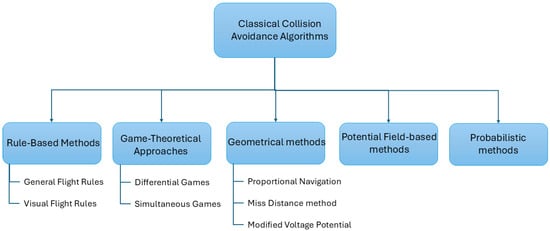

The subsequent step to the threat identification is the decision of the evasive maneuver to perform to avoid a mid-air collision. As for the alerting and threat identification, the CA algorithm must consider the response of other CA systems equipped on the intruder. The avoidance maneuver must thus be compatible or coordinated with the maneuver that other systems such as the TCAS may suggests. Furthermore, the avoidance maneuver must consider possible errors in the estimation of the position of the intruder. Finally, as noted in [113], the CA algorithm must be robust to modification of the trajectory of the intruder, which is the most challenging aspect in the design of a CA system. There are different categories of CA algorithms used for this purpose. The most common ones are rule-based, geometric, game theory, probabilistic, and potential field-based methods. This classification is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Classification of classical methods for CA.

Rule-based methods extrapolate a set of rules for the deconfliction from the General Flight Rule, like in [114], or from the Visual Flight Rules like in [115]. Alharbi et al. [116] describe a rule-based deconfliction method based on three stages with rule for every stage. However, this work addresses the deconfliction problem mainly from the perspective of ATM, rather than that of airborne CA systems. Rule-based CA is also one of the preferred methods with swarms; for instance, in [117], the CA between UAV in a swarm is achieved using the Reynolds rules [118].

Through game theory, the collision of two or more UAVs is modeled in most of the literature as a differential game [119]. Through this formulation, a cost function models the state and the evolution of the game through time and a subsequent optimization process solves the game and provide the avoidance maneuver. The modeling of the conflict is usually achieved through a pursuit–evasion game [120]. Pursuit–evasion games are games between two players, where one of the players (the pursuer) tries to catch the other one (the evader), which in turn tries to evade it. Modifications or restrictions in the movement of one of the two players can be considered by using one of the many variations of this game. The approaches described in [121,122] use differential pursuit–evasion games to model the conflict. In [122], a variation of the game, named the “Suicidal Pedestrian” is used in order to consider limitations in the movement of the evader while giving full freedom of mobility to the pursuer. Contrary to the two approaches presented before, in [123] the conflict is modeled using a simultaneous pursuit–evasion game. The conflict is discretized into a series of simultaneous games which end after the two players decide which actions to perform.

Geometrical methods are characterized by two stages: one is the analysis of the conflict in geometrical term, like for instance with the use of the so-called collision cone [124]. Similarly, as in the previously described SSD method, the PZ of the aircraft and the tangents to the PZ define a cone where the relative velocity vector must not lie to avoid the conflict. In [125], the collision cone is used to determine an “aiming point”, which is then used as a target for a guidance algorithm based on differential geometry [113]. In [126], the collision cone is used to compute a velocity change which is then achieved through proportional navigation. A cooperative geometrical approach is described in [127]. The authors compute the miss distance between two UAVs from their positions and velocities. Subsequently they elongate the miss distance vector to obtain two velocity commands, one for each UAV. Another famous geometrical conflict resolution method is the “Modified Voltage Potential”. This method was originally developed at the MIT Lincoln Laboratories [128], and it is based on the computation of the displacement of the ownership trajectory along the avoidance vector, i.e., the vector between the predicted ownership position and the edge of the intruder’s PZ. Hoekstra et al. then in [5] used this algorithm to develop a concept logic for separation assurance in free flight.

Other noteworthy methods of CA are probabilistic approaches, such as the one implemented in ACAS Xu. As described in [24], the encounter is modeled as a Markov Decision Process (MDP). An MDP models the interaction between a system and its environment in terms of state–action pairs, where the next state depends only on the current state and action (the Markov property). The MDP is solved offline using dynamic programming, and the resulting values (Q-values) are stored in a lookup table. During an encounter, the system uses the current state estimate to query this table and selects the action with the best entry. Human-in-the-loop evaluations reported in [129] demonstrated the effectiveness of the approach in reducing losses of WC for both cooperative and non-cooperative intruders, although the number of losses of WC was higher in the non-cooperative case. This was primarily attributed to the limited range of the radar sensor. The same work also discusses limitations related to human–machine interaction and pilot compliance; however, these aspects are outside the scope of the present review, which focuses on autonomous platforms.

Finally, potential fields methods model the CA problems as charged particles in an electromagnetic field. By associating an attractive potential to the target waypoint and a repulsive potential to obstacles and intruders, it is possible to obtain an optimal obstacle-free trajectory. These methods are capable of providing optimal trajectories but, as mentioned in [130], their practical implementation often suffer from the local minima problem. Furthermore, problems may arise if the target waypoint is close to an obstacle and the trajectory can be highly irregular in some point. The authors then propose an implementation of the Artificial Potential Field algorithm which address these issues producing optimal trajectories. In [131], a CA system based on the Artificial Potential Field algorithm is presented. The authors integrate different components of different Artificial Potential Field algorithms to achieve CA between two UAVs. In particular, the definition of the potential functions is based on the work presented in [132], while the prioritization logic is based on the work presented in [133]. Table 7 summarizes the surveyed literature.

Table 7.

Surveyed non-learning-based CA methods.

Common failure drivers include model mismatch (unmodeled accelerations/intent changes), combinatorial growth of encounter classes in dense traffic, and brittle behavior under distribution shift (e.g., heterogeneous vehicles and operational constraints).

3.3.2. Machine Learning Approaches

The classical CA techniques described above are predominantly model-based and rely on predefined logic, analytical safety criteria, or explicitly enumerated encounter geometries; while these approaches provide strong interpretability and, in some cases, formal safety guarantees, their effectiveness can be challenged as traffic density, encounter complexity, and uncertainty increase, particularly in highly dynamic and heterogeneous airspace.

In recent years, AI has gained increasing attention in the field of CA because of its potential robustness in such scenarios, especially in complex, high-traffic environments and in the presence of unpredictable behavior by other airspace users. By learning decision policies directly from data, ML-based approaches aim to handle high-dimensional state spaces and complex multi-agent interactions without requiring explicit modeling of all possible encounter configurations.

In the context of CA, a large body of recent work relies on reinforcement learning (RL) to compute avoidance maneuvers. Keong et al. in [134], trained an agent with the Deep Q-Network (DQN) [135] algorithm to resolve conflicts in two different scenarios. Zhao et al. in [136] summarized physics information about the conflict such as number of aircraft’s positions, speeds and heading angles in an image which describes the traffic around the own vehicle with the previously described SSD method. These images are fed to the agent, which includes CNN layers, trained with the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm [137] to resolve the conflicts. The use of images representing the traffic with the SSD method makes also the approach human-understandable. Ribeiro et al. in [138] trained an agent with the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) [139] to resolve conflict in the airspace by defining heading deviation and a change of speed after receiving as input the relative bearing and distance of a fixed number of intruders. They pre-trained the critic network of the DDPG with values extrapolated by using the Modified Voltage Potential method. The authors used these results to improve training procedure to train an agent to optimize the MVP method for a variable number of intruders. They published their results in [140]. Brittain et al. in [111] trained an agent with the Discrete Soft Actor–Critic (SACD) algorithm [141] extended by an attention network to achieve decentralized conflict resolution in Urban Air Corridors in AAM scenarios. Brittain et al. [112] presented a multi-agent reinforcement learning framework which employs PPO agents for distributed conflict resolution. Wang et al. in [6] trained an agent to ensure self-separation in Free Flight with an algorithm called Safe-DQN. They developed this algorithm by modifying the formulation of the Bellman Equation, foundation of the classical DQN algorithm, making it the sum of a goal Q-value and a safe Q-Value. This algorithm ensures that the actions of the agent have an appropriate level of safety. Furthermore, they tested the performance of the agent in case of adversarial attack, i.e., an attack aimed at mislead the agent into making the wrong decision using faulty input. Finally, by visualizing the safety values and the Q-values they claimed that the actions of the agent can be understood by humans. Pham et al. in [142] used reinforcement learning to find the best conflict resolution maneuver defined by the time to change heading and the point of return to the original trajectory. Their strategy is composed of two stages: First, a vector of possible times to heading change is generated. Then, for every one of these times, a DDPG agent chooses the best point of return. This results in the creation of different avoidance maneuvers. The best one is then selected with a DQN-like strategy. Tran et al. in [143] trained with the DDPG method an agent to solve conflicts in the airspace by imitating the conflict resolution advisories from a Air Traffic Control Operator (ATCO). This was possible by defining a reward which depended from the similarities between the resolution of the agent and the one of the operator.

It is important to note that, to date, the performance and robustness of RL-based CA approaches have been demonstrated primarily through simulation studies, often under controlled assumptions regarding sensing, communication, and traffic behavior. As such, the potential advantages of ML should be interpreted as indicative rather than conclusive, and do not yet constitute evidence of operational readiness or certified safety performance.

A noteworthy example of AI-based CA that is not based on reinforcement learning is the family of neural networks originally designed as a compact representation of the ACAS X CA policy. These neural networks were first introduced in [144,145] as a function-approximation of the large ACAS Xu score table obtained via dynamic programming. The authors show that the neural-network-based compression of the lookup table reduces the required storage by roughly a factor of 1000, while largely preserving (and in many cases even improving) the preferred advisory in large-scale Monte Carlo simulations. To provide formal safety guarantees for neural network CA controllers of this type, the same research group in [146] later combined reachability analysis with neural network verification tools such as Reluplex [147] and ReluVal [148] in order to prove closed-loop safety properties for notional vertical and horizontal CA systems inspired by ACAS X. Subsequent work by Bak and Tran [149] performed closed-loop verification of the ACAS Xu early-prototype neural network compression and showed that, even under highly favorable assumptions (perfect sensing, idealized dynamics, instantaneous pilot response, and a straight-flying intruder), the compressed neural network controller admits encounter scenarios that lead to near mid-air collisions. Table 8 summarized the surveyed literature.

Table 8.

Surveyed AI-based CA methods.

3.4. Summary of Sensing, Reasoning, and Avoidance Methods

Table 9 provides a unified functional mapping of the methods surveyed in this paper across sensing, reasoning and alerting, and avoidance, and relates them to the classical detect–track–evaluate–declare–avoid pipeline, including typical prerequisites and failure modes. At the sensing level it summarizes radar-, vision-, LiDAR-, cooperative-, and learning-based detection; the reasoning/alerting layer covers tracking, conflict assessment, and alert logic (e.g., kinematic metrics, WC predicates, and uncertainty-aware or learned evaluation); and the avoidance layer groups maneuver-generation approaches spanning geometric guidance, decision and game theoretic methods, potential fields, and learned control policies. This table serves as a compact reference linking the paper’s taxonomy to the system functions required for separation assurance.

Table 9.

Concise framework mapping between the classification used in this paper and the classical functional decomposition (detect–track–evaluate–declare–avoid). Typical prerequisites (P#) and failure modes (F#) are summarized at the algorithm-family level; see legend below.

4. Discussion and Outlook

The survey presented in this paper has examined a wide range of technologies for CD&R and CA, covering both classical algorithmic approaches and recent ML-based methods. Across this range, a central theme is the tension between exploiting the benefits of AI—greater adaptability, improved performance in complex scenarios, and scalability to dense traffic—and satisfying the stringent safety and certification requirements of the aviation domain. This tension is particularly pronounced in CD&R and CA, where system behavior must remain predictable, and acceptable to regulators, operators, and the public.

As of the time of writing, no dedicated, domain-specific certification specifications, acceptable means of compliance, or guidance material (AMC/GM) exist for the integration of AI-based methods in airborne CD&R and CA. EASA’s AI Concept Paper Issue 02 [13] provides practical guidance for the certification of ML-based systems, but its current scope is limited to Level 1 and Level 2 AI (“assistance to human” and “human–AI teaming”) and to offline supervised and unsupervised learning. Within this scope, the worked examples address only a narrow subset of separation-assurance and surveillance problems, such as runway foreign-object debris and intruder detection. For supervised computer-vision detection functions of the type used in these examples, EASA and Daedalean have also introduced a W-shaped learning-assurance life cycle, which adapts the classical V-model by explicitly covering dataset management, the learning process, and model verification. For CD&R and CA perception, dataset management is complicated by two pervasive issues: (i) out-of-distribution (OoD)/outlier operating conditions relative to the AI/ML constituent ODD, and (ii) annotation errors and imperfect ground truth in supervised datasets. OoD/outlier conditions arise because operational airspace may contain objects and phenomena not represented in the training distribution (e.g., birds, balloons/kites, debris, or previously unseen UAV types), as well as rare backgrounds and weather/illumination regimes. If not treated explicitly, these factors can lead to nuisance detections (false positives) that propagate into alerting, or missed intruders (false negatives), both of which are safety- and operations-critical. In addition, aerial datasets often exhibit non-trivial uncertainty in data labeling due to the difficulty of annotating small, distant targets and establishing reliable ground truth across sensors; if not controlled, this can bias training and lead to overconfident predictions. In the W-shaped life cycle, these issues motivate explicit dataset representativeness/completeness arguments against the ODD, verification of data labeling against ground truth, uncertainty-aware evaluation (including an unknown/reject outcome for OoD inputs), and conservative system-level mitigation (e.g., corroboration requirements, track-quality gating, and fallback behaviors under low-confidence conditions). This model is now used as a main reference for assuring Level 1 and 2 ML detectors in safety-critical avionics [150]. Conversely, decentralized air-to-air CD&R and CA are not treated explicitly, even in a purely decision-support role [13].

In parallel, ongoing rule-making activities on AI trustworthiness aim to translate the concept paper into a sector-wide regulatory framework and generic AI-related AMC/GM [151], but concrete certification pathways for highly autonomous applications remain largely unresolved. The regulation of highly autonomous AI-based applications (Level 3, “advanced autonomy”) is expected to be addressed in future EASA rule-making, at which point AI-based CD&R and CA is also likely to come into scope.

Against this background, the research literature on AI-based CD&R and CA tends to adopt design patterns that minimize perceived regulatory risk, as discussed below.

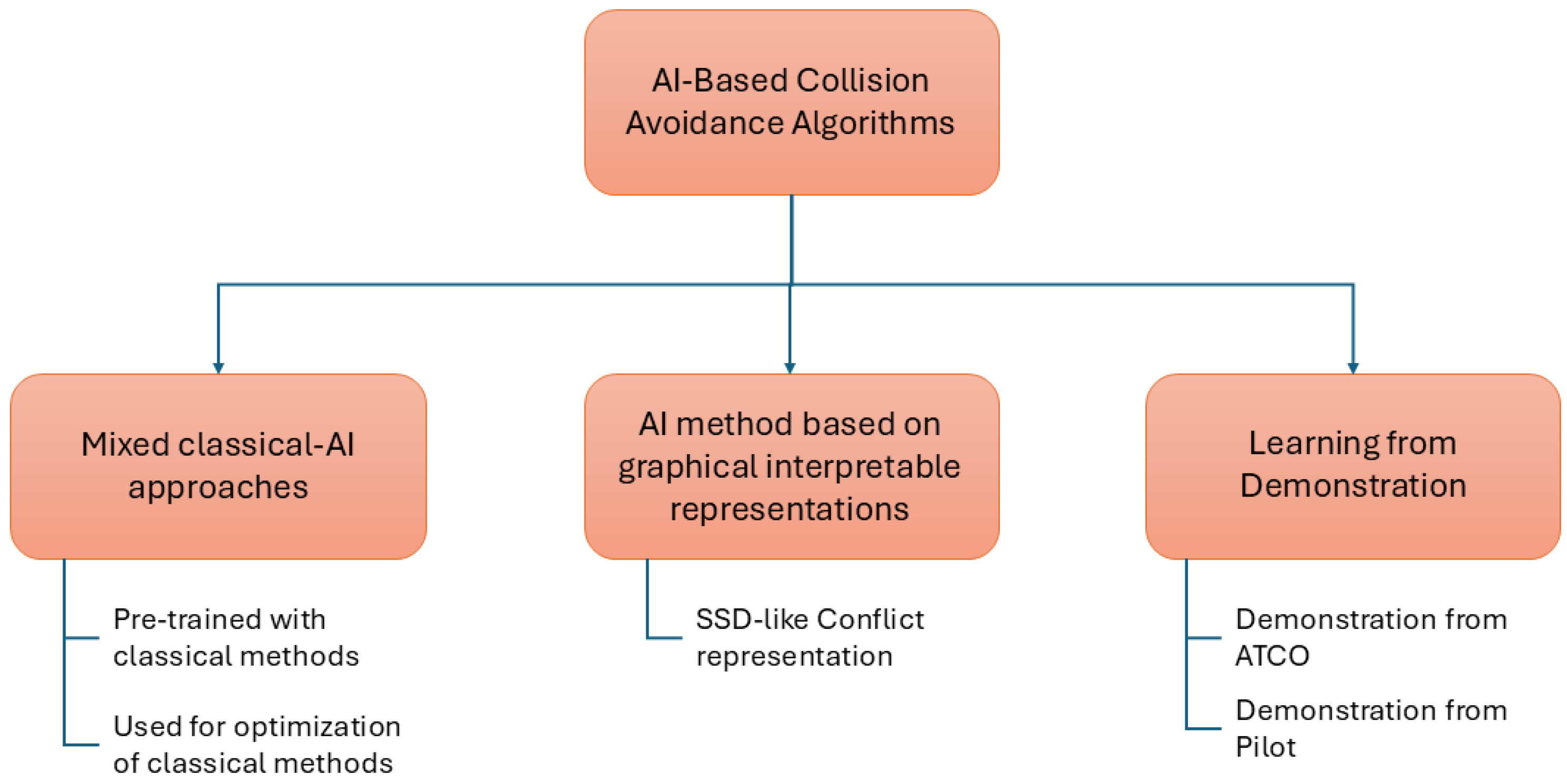

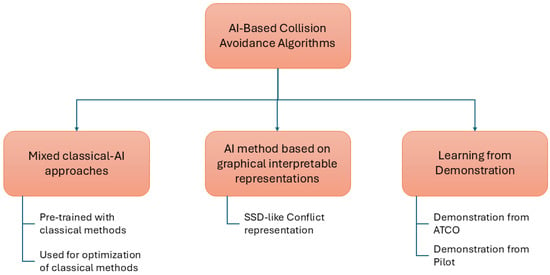

4.1. Certification-Driven Patterns in AI-Based CA

A first pattern emerging in the literature is the use of AI not as a replacement for classical logic but as a means to optimize, approximate, or compress algorithms while preserving a transparent core structure. Examples include the agent that optimizes the MVP algorithm in [140] as well as the policy-compression work for ACAS X in [144,145], in which neural networks approximate a dynamic-programming policy rather than replacing it with a fully opaque controller. In these designs, the safety-critical decision logic remains grounded in classical models, while AI components serve as an efficient surrogate or optimization layer, reducing computational and memory footprints.

A second pattern involves retaining human-interpretable intermediate representations, even when the final policy is implemented via neural networks. Some approaches encode geometrical or graphical constructs—such as SSD-like state-space diagrams or conflict images, as in [136]—as input to a learning algorithm. Intermediate representations, including positions, velocities, headings, and conflict zones, remain interpretable for human experts, while AI maps them to CA advisories. This shared representation facilitates human situational understanding, supports debugging and verification, and enhances regulatory compliance. Similarly, the visualizations of the Q-value and the safety-boundary in [6] provide an interpretable insight into the agent’s reasoning, reducing the complexity of demonstrating compliance.

A third pattern is the combination of reinforcement learning with learning from demonstration, as in [143]. Agents are first trained to mimic controller or pilot behavior, and subsequently refined with RL. Rewards encourage alignment with operational human procedures, anchoring AI behavior in real-world practices. Although formal safety assurance remains necessary, this approach can improve operator trust and facilitate regulatory compliance by ensuring that learned policies adhere closely to accepted procedures.

These three patterns are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Certification patterns in AI-based CA.