Abstract

In this work, we evaluate the impact of numerical integration methods and perturbation models on the computational speed and position accuracy of orbit propagation techniques. With increasing numbers of satellites in orbit, space traffic management may require near real-time satellite operations, for which computational speed may play a more important part in orbit propagation than positional accuracy. The aim of this work is to identify the most suitable propagation parameters for different mission scenarios and outline the perturbations to be considered based on the target orbit characteristics. We analyze the impact of the integrators’ tolerance on accuracy and runtime, as well as quantify the dominant perturbations for each orbit type. We use a Starlink satellite as a reference case, propagating it across multiple orbital regimes. The results are presented in the form of Pareto fronts trading off runtime and positional accuracy. These Pareto fronts outline some important results, for instance, how gravitational models beyond yield no accuracy improvements while significantly increasing runtime. We also verify that drag is critical in VLEO, LEO, SSO, and HEO (Molniya), while third-body effects play a major role in HEO (Molniya and Tundra), GEO, and GSO, and solar radiation pressure becomes significant in HEO (Tundra), GEO, and GSO. These results can be incorporated into collision avoidance optimization strategies for real-time satellite operations, thereby contributing to more efficient space traffic management.

1. Introduction

On 10 February 2009, an operational Iridium 33 communications satellite and the defunct Russian satellite Cosmos 2251 collided, marking one of the first major accidental collisions between two intact satellites [1]. This event highlighted the risks of space debris and underscored the need for accurate orbit propagation models to enhance collision predictions and prevent such incidents in the future. As the number of satellites in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) continues to rise, driven largely by the expansion of mega-constellations, space safety has become a growing concern. Studies indicate a significantly high probability of satellite collisions within these constellations, necessitating advanced space traffic management systems to ensure safe operations [2,3,4]. For instance, during a five-year operational period, the likelihood of at least one catastrophic collision within the OneWeb constellation is estimated at 5.0%, while for SpaceX, this is substantially higher at 45.8% [5]. The Iridium–Cosmos collision serves as a case study illustrating the limitations of traditional orbit propagation models. On the day of the event, predictions based on available Two-Line Element (TLE) sets estimated a 600-m miss distance, and the conjunction was not even ranked among the CelesTrak top ten closest approaches for the day [1]. A more accurate propagation model could have refined these estimates, revealing a higher probability of collision and potentially allowing for preventive measures.

Orbit determination, the process of estimating the state vector of a space object, and orbit propagation, which forecasts the future state of the object, are essential for space situational awareness and collision avoidance [6,7]. An orbital propagator is the numerical method that performs this prediction by integrating the spacecraft equations of motion under the chosen set of perturbations [8]. Achieving precise and fast orbit propagation is crucial to predict trajectories under the influence of various gravitational and non-gravitational forces. Ensuring both high accuracy and computational efficiency in orbit propagation is essential, as trajectories are influenced by multiple gravitational and non-gravitational forces [9]. Accuracy allows for safe spacecraft operations and timely maneuvers to prevent collisions, while computational speed is critical for rapid decision-making in dynamic space environments. Effective space traffic management depends on accurate trajectory forecasts, requiring near real-time analyses to maintain up-to-date positional knowledge [10]. However, balancing accuracy and runtime remains a key challenge in modern orbit propagation models, as achieving one often comes at the expense of the other.

This paper performs a comprehensive analysis of different orbit propagators within the ESA GODOT Software Tool using multi-objective optimization frameworks, such as Pareto fronts. These offer insights into how to strike a balance between computational speed and accuracy, crucial for near real-time applications, in orbit prediction for collision avoidance maneuvers related to space debris challenges. Through our exploration, we also reveal the significant influence of gravity models and perturbations on orbit prediction, alongside the impact of tolerance levels in propagators. By analyzing the obtained Pareto fronts, the evaluation and decision-making at critical junctures of a mission is facilitated, thereby contributing to safer and more effective space mission planning. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first paper presenting such a trade-off between computational speed and accuracy through Pareto fronts in the context of orbit propagation for collision avoidance strategies.

The paper proceeds as follows: we start by defining the challenges of numerical orbit propagation and its critical requirements, emphasizing the trade-offs involved and their significance. In exploring the core components—ordinary differential equations (ODE) of motion, perturbations, and the integration method—we introduce the GODOT software tool and its use in orbit propagation. Subsequently, we provide a brief definition of a Pareto front and explain its importance for our purposes. Representative orbits spanning various altitudes to address diverse mission scenarios are then selected and analyzed with the help of the obtained Pareto fronts, showing how to navigate the trade-off between positional accuracy and execution time.

2. Related Work

Orbit propagation and the required accuracy to solve a specific problem have been addressed before. It is a fundamental aspect of astrodynamics, extensively covered in classical works such as Montenbruck and Gill [11] and Vallado [8]. These references provide the foundation for understanding numerical integration techniques, perturbation modeling, and their impact on orbital prediction accuracy.

Long-term numerical propagation techniques for Earth-orbiting satellites are assessed in [12], comparing various numerical and semi-analytical methods. Despite differences in processing time, both methods achieve similar accuracy, with errors ranging 1–10 km after a year of propagation. The investigation underlines the significance of step sizes for integrators and the necessity of periodic corrections to maintain accuracy.

The complexities of orbital propagation for Space Surveillance and Tracking (SST) operations are addressed in [13], focusing on fragmentation modeling and collision risk assessment. By integrating an adaptive orbital propagation environment, significant computational time savings are achieved while maintaining accuracy. The study highlights the importance of selecting perturbations based on orbital altitude and object count, with future works focusing on additional test cases and longer propagation time-spans.

A comprehensive review of numerical integration techniques for solving the gravitationally perturbed two-body problem is conducted in [14], evaluating both implicit and explicit methods across different orbital regimes, from LEO to Molniya orbits. Results suggest that high-order integrators, such as Adaptive Picard–Chebyshev, outperform traditional explicit methods in both precision and efficiency.

Additionally, uncertainty propagation in orbital mechanics has been explored to improve prediction accuracy. The study in [15] reviews methods such as Monte Carlo simulations, statistical linearization, and differential algebra techniques, emphasizing the need for nonlinear uncertainty propagation techniques in highly perturbed environments.

In the context of space traffic management, accurate orbit propagation is essential for effective collision avoidance, as discussed in [16,17]. The study highlights limitations in current orbital prediction methods and emphasizes the need for improved uncertainty quantification to enhance conjunction assessments. Given the increasing number of space objects, refining propagation techniques is crucial to minimize false alarms, reduce unnecessary avoidance maneuvers, and ensure the safe and efficient operation of satellites.

Some studies have also focused on optimizing the trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency in orbital propagation. A method to improve computational performance while maintaining accuracy is presented in [18], which proposes adjusting the number of geopotential spherical harmonics dynamically based on altitude. This approach successfully balances accuracy with reduced computational costs.

The importance of selecting an optimal orbit propagator for space traffic management and collision avoidance is addressed in [19], which presents the new PROP-SAFE tool (Propagation analysis Software for Advanced Pareto-Front Evaluations). This tool automatically evaluates over 1500 different propagators, generating tailored Pareto fronts to help in choosing the most suitable propagators for specific satellite missions.

These studies collectively highlight the ongoing advancements in orbital propagation, focusing on accuracy, computational efficiency, and uncertainty quantification factors which are crucial for applications such as space situational awareness, collision risk assessment, and mission planning. The challenge remains in balancing accuracy and runtime, particularly in the context of perturbation modeling, using multi-objective optimization approaches, such as Pareto front analysis, which can be a necessary tool in selecting optimal propagation strategies.

3. Problem Definition and Methodology

3.1. Numerical Orbit Propagation

Orbit propagation involves tracking the motion of celestial bodies, both natural and artificial, as they orbit planets. In many relevant cases, including the motion of satellites around the Earth, the point-like term of the gravitation force exerted by the central body dominates, and the motion can be divided between the approximated solution of this two-body problem plus perturbations, i.e., forces much smaller that disturb the simplified problem.

A numerical propagator, the subject of our analysis, comprises three main components: the equation of motion, which is formulated as a system of ordinary differential equations (ODE), the perturbing accelerations included in those equations, and an integration method. In the Cowell formulation of differential equations for orbit computation, the equations of motion are adapted to numerical methods, taking into account perturbing accelerations [8]:

where is the standard gravitational parameter (of Earth for the case analyzed in this paper) and represents the sum of all perturbation forces acting on the satellite. The perturbations can be categorized into gravitational and non-gravitational forces, detailed in Table 1 [11].

Table 1.

Gravitational and non-gravitational perturbations for satellites orbiting around Earth [11].

Astrodynamics relies on numerical methods to solve the differential equations of motion with perturbations [8]. These methods are crucial for solving problems related to orbital dynamics, and their accuracy depends on the choice of integration scheme. Common methods are Runge–Kutta and Adams (see Section 3.2).

3.2. GODOT Software

GODOT, the General Orbit Determination and Optimization Toolkit, was chosen for its status as the state-of-the-art reference software for mission analysis and in-flight operations at ESA/ESOC [20]. The software is made available by ESA with openly accessible source code under the ESA Community License. It is implemented as a collection of C++ libraries, and there is also a Python interface so that users can build applications in Python. In this work, we use the Python interface of GODOT version 1.9.0 for extensive orbit propagation analyses. The software’s foundational principles, including formulations of light time, relativistic effects, and dynamical models, are based on the orbit determination technical report by Moyer in 1971 [21]. These models allow for the calculations of spacecraft trajectory parameters for lunar and planetary missions based on the spacecraft data retrieved from Earth.

Within GODOT, users have the flexibility to choose perturbation terms based on their specific needs. The perturbation terms included in our analyses were the geopotential up to spherical harmonics order and degree , Sun and Moon as third bodies, solar radiation pressure (SRP), and drag. To model the drag, we use the NRLMSISE-00 atmospheric model [22] that relies on geographical and time data and requires space weather information, including solar flux and geomagnetic indices, to produce accurate results. This model is a widely accepted choice for modeling atmospheric drag in astrodynamics [8].

The purpose is to illustrate how it can work to determine the best equilibrium for the user goals between accuracy and computational speed. For that, we use a relatively simple force model. In general, we aim for an accuracy goal of , as beyond that too many perturbations become relevant, and use an integrator tolerance of – to assure that integration tolerances do not play a role in the determination of the model accuracy.

It is well-known that geopotential terms can induce orbital inclination-dependent resonance effects. The selection of an spherical harmonic model was dictated by the maximum available resolution in the GODOT software used for our simulations, to ensure that eventual resonances would be captured. This inclusion, although inducing in principle much smaller effects than other perturbations, such as, for example, the third-body effects from Jupiter and Venus, makes possible the analysis of the relative importance of the geopotential per se, and checks if it is relevant at a certain level of accuracy. The overall model is not necessarily realistic, but the geopotential terms’ effects and their importance above the expected is still relevant and detectable.

All levels of accuracy in our analysis must therefore be interpreted as relative to the most complete force model used and among the several perturbations considered. For real high levels of accuracy, all relevant perturbations must be included and analyzed. A more detailed explanation of the perturbation models used, including their definitions and equations, can be found in [19].

Users can select integration methods in GODOT tailored to specific propagation needs and the corresponding absolute and relative local error tolerances. Currently, GODOT provides two primary integration algorithms [23,24,25]:

- 1.

- Runge–Kutta Verner (RK78): A seventh-order method that dynamically adjusts step sizes based on tolerance requirements, offering two variants: Verner787 which constructs a seventh-order interpolating polynomial and provides dense output; Verner788 which constructs an eighth-order interpolating polynomial and provides dense output.

- 2.

- Adams–Bashforth–Moulton (ABM): This algorithm incorporates a variable-order, variable-step size predictor–corrector scheme with an Adams–Bashforth predictor and an Adams–Moulton corrector, also offering dense output.

Integration in GODOT requires specifying absolute and relative tolerances for each component. Local error (e), a measure of integration accuracy within a single step, is accepted based on the condition [26]

where y is the current function value, and are the relative and absolute tolerances, respectively. If the error exceeds this threshold, the step size may be halved and the step repeated, optimizing computational time [27]. Global error, derived from local error, varies according to specific scenarios.

In general, the Adams–Bashforth–Moulton algorithm is faster than Runge–Kutta methods for most scenarios while maintaining comparable accuracy. However, Runge–Kutta methods have undergone more extensive testing by ESOC [26]. In scenarios with densely packed events, such as rapid changes or disruptions during integration, Runge–Kutta methods may outperform Adams. The choice between Verner787 and Verner788 hinges on the desired accuracy level, with Verner787 providing sufficient accuracy with a 20% performance cost and Verner788 offering slightly more accurate interpolation at a 60% performance cost [26].

Furthermore, integration accuracy assessments at various error tolerances revealed insights into GODOT integrators. By varying tolerance levels, we aimed to delineate the precision thresholds of each integrator. To isolate the integrator error independent of perturbations, we compared numerical solutions with exact solutions for the two-body problem. Notably, we observed that reducing tolerance values below for the RK methods and below for the ABM method resulted in decreased accuracy and increased execution times. This outcome arises from the limits of machine precision, as further reductions in tolerance cause round-off errors to accumulate. Numerical integration involves repeated arithmetic operations, and each operation introduces a small error due to the finite precision of floating-point numbers in computers. When the tolerance is very low, the algorithm requires more iterations or finer subdivisions, which increases the number of arithmetic operations. This accumulation of round-off errors can eventually dominate the error in the final result, leading to worse accuracy. Hence, tolerance values were considered down to for the RK methods and for the ABM method. Lower values— and below for RK, and and below for ABM—were not considered in our analysis.

3.3. Pareto Front

Accurate satellite orbit propagation requires solving equations of motion under various perturbative forces and integrating them numerically over time. The choice of numerical methods and the complexity of included perturbations directly influence both the accuracy and computational efficiency of the simulation.

In this context, accuracy refers to the deviation between the propagated trajectory and a high-fidelity reference solution. This reference solution incorporates the minimum tolerance level for the ABM method () and all perturbations, including geopotential (up to ), drag, SRP, and third-body effects. The maximum position errors for different propagators are assessed by comparing their results to this reference solution. In this study, the position error is computed as the Euclidean norm of the difference between the propagated and reference position vectors at the final epoch of the 7-day simulation. Runtime, instead, measures the computational cost of executing the propagation. Achieving high accuracy often requires incorporating more perturbations and higher-order numerical methods, but this comes at the expense of longer execution times. Conversely, reducing computational demand typically results in decreased accuracy.

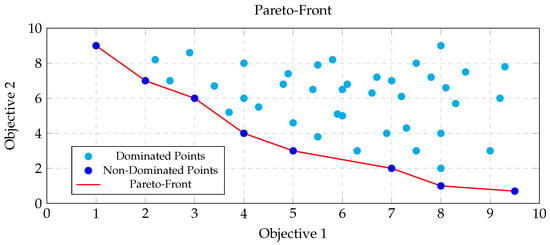

Striking a balance between these competing objectives is a fundamental challenge. A multi-objective optimization framework can be used to identify solutions that offer optimal trade-offs between accuracy and runtime. The Pareto front, a key concept in such an approach, represents the set of non-dominated solutions—configurations where neither objective 1 (accuracy) nor objective 2 (runtime) can be improved without sacrificing the other.

In multi-objective optimization, solutions are classified as either dominated or non-dominated based on their performance across multiple criteria. A solution is considered dominated if another alternative exists that performs better in both objective 1 and objective 2. Conversely, non-dominated solutions define the Pareto front, which highlights the best achievable compromises. As depicted in Figure 1, these solutions represent optimal trade-offs where no further improvements in one objective can be achieved without worsening the other [28].

Figure 1.

Pareto front illustrating the trade-off between objective 1 and objective 2. Non-dominated solutions (blue) define the optimal frontier (red).

To construct the Pareto front for this study, numerical orbit propagation processes were performed using different integration methods settings (e.g., tolerances) and perturbation models. The reference trajectories, serving as the benchmark for the accuracy assessment, were generated using high-precision solutions from GODOT. Maximum position errors were computed by comparing each propagated state to the reference at corresponding time steps. Execution times were recorded for each case.

A total of 320 unique propagator configurations were generated by combining different integration parameters and force models. Specifically, using one integration method at five different tolerances, resulting in five variants. In parallel, different perturbation environments were defined by combining the possible perturbations—eight geopotential values (, , , , , , , ), drag, SRP, and third body (Sun and Moon)—yielding 64 unique variants. The representative orders of the geopotential were identified in a previous study [29]. When pairing each of the five integration variants with the 64 perturbation configurations, a total of 320 unique combinations were created. These represent all possible configurations of integration settings and physical models used in the analysis, with each corresponding to a distinct point on the Pareto front.

The Pareto front was determined by filtering out dominated solutions. Specifically, for each propagation configuration, its accuracy and runtime were compared against all others. If a configuration exhibited both lower accuracy error and shorter runtime than another, the latter was considered dominated and excluded. The remaining set of solutions formed the Pareto-optimal front, providing insight into the best trade-offs achievable under the tested conditions. Note that the Pareto fronts presented in Section 4 illustrate the trade-off between accuracy (x-axis) and runtime (y-axis), displaying only the non-dominated solutions to improve readability.

3.4. Use Cases

Accurate orbit propagation is crucial in the context of large satellite constellations. Starlink, a significant player in LEO, highlights the importance of this analysis. To evaluate propagator performance, we examined various orbital regimes using the parameters of a representative Starlink satellite from the Generation 1.0 constellation. The geometric parameters such as mass (m), cross-section area (), drag coefficient (), and reflectivity coefficient () of this satellite are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Starlink Generation 1.0 satellite parameters [5].

The study encompasses a range of orbits from LEO to GEO, as detailed in Table 3, including orbital characteristics such as apogee altitude (), perigee altitude (), eccentricity (e), inclination (i), and period (T). These orbits constitute the set of cases used for the Pareto-front analysis performed later in this study, providing a representative variety of dynamical environments. The orbital parameters listed in Table 3 correspond to typical representative values widely used in modeling studies to characterize typical LEO/MEO/GEO regimes. The satellite is propagated for seven days in each regime, and the epochs were chosen arbitrarily, yet consistently set in the past when comprehensive Earth Orientation Parameter (EOP) and solar weather data were accessible. This approach aimed to minimize the complexities stemming from predicted data, including data sources, values, and interpolation methods. Additionally, the inclusion of extra orbits in the LEO category aimed to enhance the precision of results, particularly in the context of drag and the lower bounds of solar radiation pressure.

Table 3.

Orbits selected for the Pareto-front analysis.

This satellite was propagated without considering a propulsion system on board. For this reason, as explained in Section 3.2, the Pareto-front analysis will be performed using the ABM method, which demonstrates the best results in terms of accuracy and runtime for general scenarios. Therefore, the reference solution was constructed using the ABM integrator and incorporating minimum tolerance () and all perturbations (geopotential , drag, SRP, third body). The maximum position errors of the various propagators were then determined by comparing their results against this reference solution.

Moreover, an inclination sensitivity analysis was conducted, revealing consistent results across a wider range of inclination values for LEO orbits, as detailed in Table 4. In addition, an eccentricity sensitivity analysis was performed, demonstrating consistent results for Tundra orbits, even extending to Super Tundra orbits with [30].

Table 4.

Extended inclination ranges for the Pareto fronts for LEO.

For the NRLMSISE-00 atmospheric model, space weather parameters such as solar radio flux indices ( and ) in solar flux units (SFU) and the planetary magnetic activity index () were assigned constant values in this study, as detailed in Table 5. These constant values correspond to the default settings used in GODOT. The solar radiation pressure vector is computed at 1AU using a simple cannonball model, i.e., spacecraft assumed spherical with a given mass, frontal area, and reflectivity coefficient . The resulting SRP acceleration vector is aligned with the illumination source direction and has magnitude equal to the radiation pressure at the current distance from the source multiplied by .

Table 5.

Space weather values considered.

It should be noted that the SRP and drag models adopted in this study follow standard simplified formulations (e.g., cannonball), and more advanced spacecraft-specific force models would further increase fidelity at a significantly higher computational cost, which lies beyond the scope of this work.

In this study, computations were carried out using double-precision floating-point arithmetic according to the IEEE 754 standard [31], which provides a precision of roughly 16 decimal places, matching Python’s default for double-precision values. To ensure meaningful reporting and avoid misinterpretation of sub-resolution values, we distinguish between the integrator tolerance (governing the adaptive step size and controlling local error per integration step) and the actual propagation error (defined as the deviation from a high-accuracy reference solution). The code was constructed in order to not consider errors below , aligning with the lowest integrator tolerance used. The simulations were conducted on a machine with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-8565U CPU (Santa Clara, CA, USA) with four cores, and 16 GB of RAM. It is important to note that all Pareto fronts are presented on a logarithmic scale for improved visualization. Consequently, points where propagators achieve maximum accuracy () will not be visible on the graph due to the undefined logarithm of zero. In such cases, the Pareto front will terminate at the y-axis. In addition, each Pareto front is accompanied by a comprehensive table within the respective figure, which provides detailed information on all the propagators, including their corresponding position error (in kilometers) and execution time (in seconds).

4. Results and Discussion

The presented results in the form of Pareto fronts and related data analysis on various propagators, labeled as P1, P2, P3, etc., for scenarios defined in Table 3, offer valuable insights into the trade-offs between computational efficiency and accuracy in orbit prediction for each specific regime. Each case (P1, P2, P3, etc.) represents a distinct combination of ABM method tolerance and perturbation models, showcasing the impact of these factors on runtime and maximum position error. The consistent use of the ABM integration method across all cases allows for a direct comparison of the effects of varying tolerances and perturbations. Lower tolerance values generally lead to higher accuracy but at the expense of longer execution times. Additionally, the introduction of additional perturbations, such as higher-order gravity models, third-body effects, drag, and SRP, progressively refines the accuracy of orbit predictions.

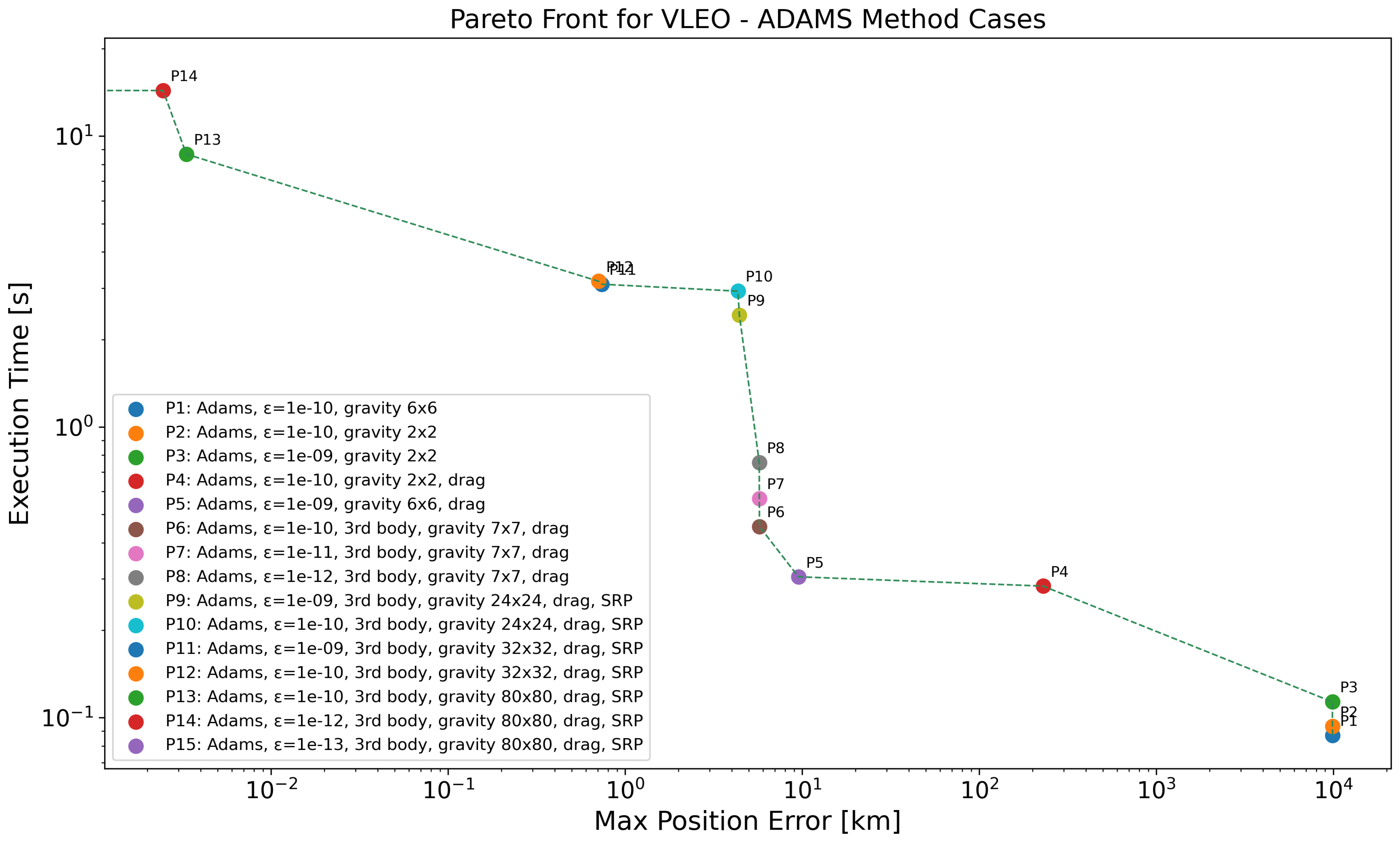

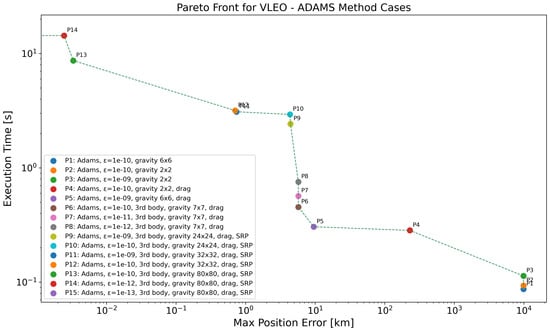

4.1. VLEO Regime

Figure 2 and Table 6 show the results for the Very Low Earth Orbit (VLEO) scenario using the ABM integrator. As expected, the position error is strongly influenced by both the integrator tolerance and the inclusion of perturbations. Propagators P1 to P3, which use simplified dynamics and loose tolerances ( to ), exhibit very large errors on the order of km, indicating that high-order gravity and atmospheric drag are indispensable in this regime, even if they require additional computational cost. A major improvement in accuracy is seen from P3 to P4, where the introduction of atmospheric drag reduces the error by more than an order of magnitude (from km to 229 km), with execution time increasing by a factor of roughly . Between P4 and P6, the gravity model is refined and third-body effects are added, reducing the error by two additional orders of magnitude (down to ∼5.7 km) at the cost of a double increase in runtime (from s to s). Interestingly, tightening the integrator tolerance (P7 and P8) yields minimal gain in accuracy but incurs growing computational cost, confirming that accuracy improvements in this range are limited more by model fidelity than by numerical resolution. The inclusion of SRP (P9–P10) has a moderate effect on accuracy, bringing the error down from km to km, while more than doubling the execution time. However, a substantial improvement is observed when refining the gravity model to (P11–P12), which brings the error below 1 km for the first time. At this point, the trade-off becomes steep: pushing the error further down to millimeter level (P13–P14) and eventually to km (P15) requires increasingly tighter tolerances and a highly resolved gravity model, with the runtime growing from ∼3 s to over 16 s.

Figure 2.

Pareto-front analysis for VLEO regime, considering all the propagators employing ABM method. Log scale used on both axes; points with zero error are not visible, causing the Pareto front to terminate at the y-axis.

Table 6.

Pareto-front data for the VLEO regime with ABM method, as depicted in Figure 2.

At this point it is important to remember that all stated errors refer to the considered perturbations only. As stated before, for real accuracy we must include all perturbations that can produce an effect of the same order of magnitude of the measured error, which was not the case for the higher accuracy results considered in this illustrative analysis. The measured accuracies are still relevant to determine the relative importance of the considered perturbations, and how much computational time they can take, and the inclusion of high-order geopotential terms assures that any orbital inclination-induced resonance is detected. In the limit, we could even use the analytical Keplerian exact solution and determine the effect of each perturbation individually. But in this case, the computational cost can be affected by the absence of other perturbation terms and be less realistic.

From this analysis, it is evident that for the VLEO regime, the most critical perturbation affecting accuracy (in addition to refining the gravity model) is atmospheric drag as seen in the significant accuracy improvements from P3 to P4, as expected. While SRP and third-body effects contribute to further refinements, their impact is comparatively smaller.

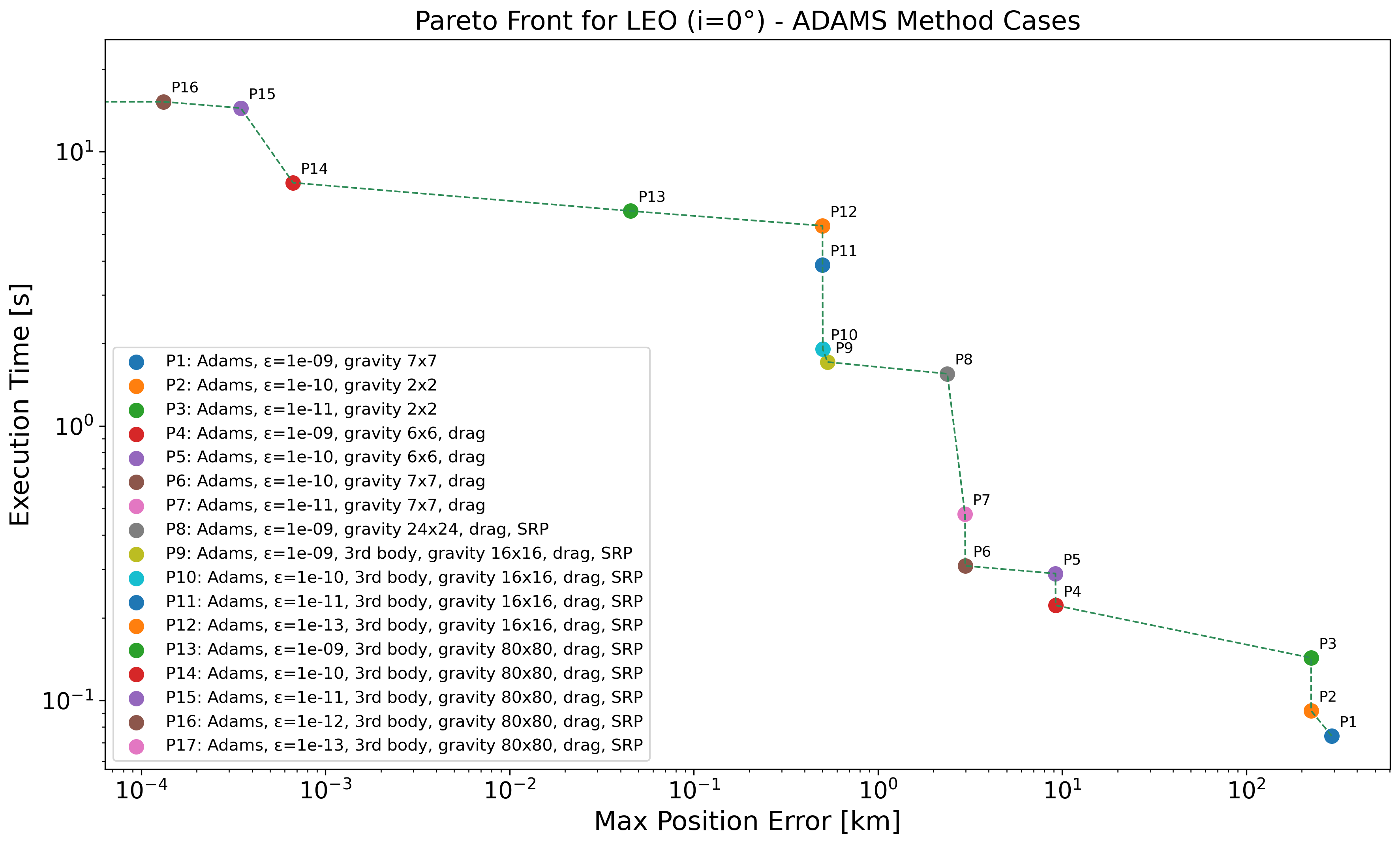

4.2. LEO Regime

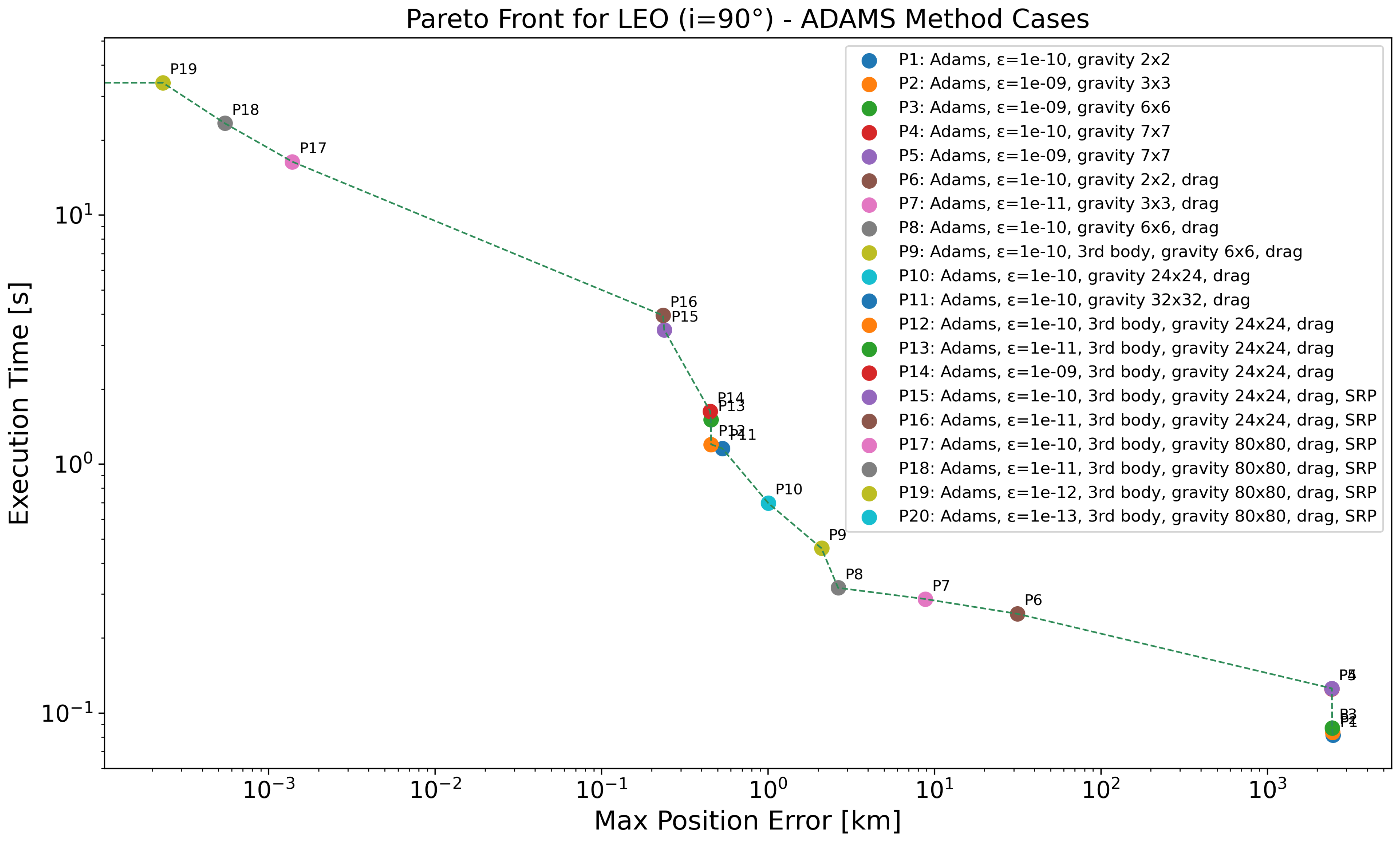

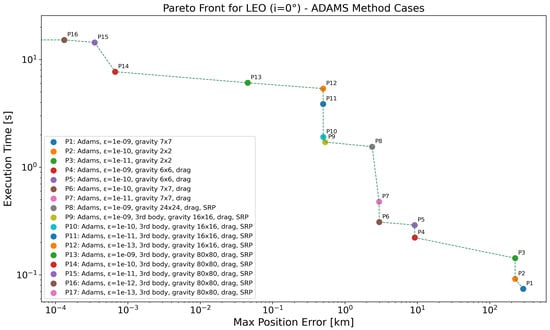

In the Pareto-front analysis for the Low Earth Orbit (LEO) with an inclination of 0° regime depicted in Figure 3 and Table 7, we observe that propagator P1, which uses a coarse gravity model () and a loose tolerance of , achieves the fastest runtime at s, but with a high position error after seven days of propagation of approximately 291 km. Tuning only the integrator tolerance (P2–P3) has little effect on the final accuracy unless the gravity model is also adapted. A major drop in error occurs with the inclusion of atmospheric drag starting from P4, reducing the error to km while increasing the runtime to s. Further minor gains in accuracy and runtime are achieved in P5 and P6 through slight improvements in both model and tolerance. Between P6 and P7, tightening the tolerance from to yields minimal improvement ( km to km) but increases the runtime by over 50%, illustrating diminishing returns when accuracy is limited by model fidelity. Significant improvement is achieved with P8 to P10 through the introduction of more complex perturbations. P8 incorporates a gravity model and SRP, lowering the error to km, but at a cost of over s of runtime. Adding third-body effects (P9) and increasing the gravity resolution to drastically reduces the error to km, a nearly fivefold improvement for a modest increase in execution time. However, tightening tolerances from P10 to P12 brings negligible additional gains in accuracy, with the error plateauing around km, while runtime increases significantly, from s to over s. To surpass this plateau, a further refinement of the gravity model is needed. Propagator P13, which uses an gravity model, drops the error to km, with a runtime of s. The next set of configurations (P14–P16) apply increasingly tight tolerances ( to ) while maintaining the same high-fidelity model reaching an position error order and different execution times. The last propagator P17 achieves near-zero position error ( km), but at the expense of execution times that exceed 19 s.

Figure 3.

Pareto-front analysis for LEO (°) regime, considering all the propagators employing ABM method. Log scale used on both axes; points with zero error are not visible, causing the Pareto front to terminate at the y-axis.

Table 7.

Pareto-front data for the LEO (°) case with ABM method, as depicted in Figure 3.

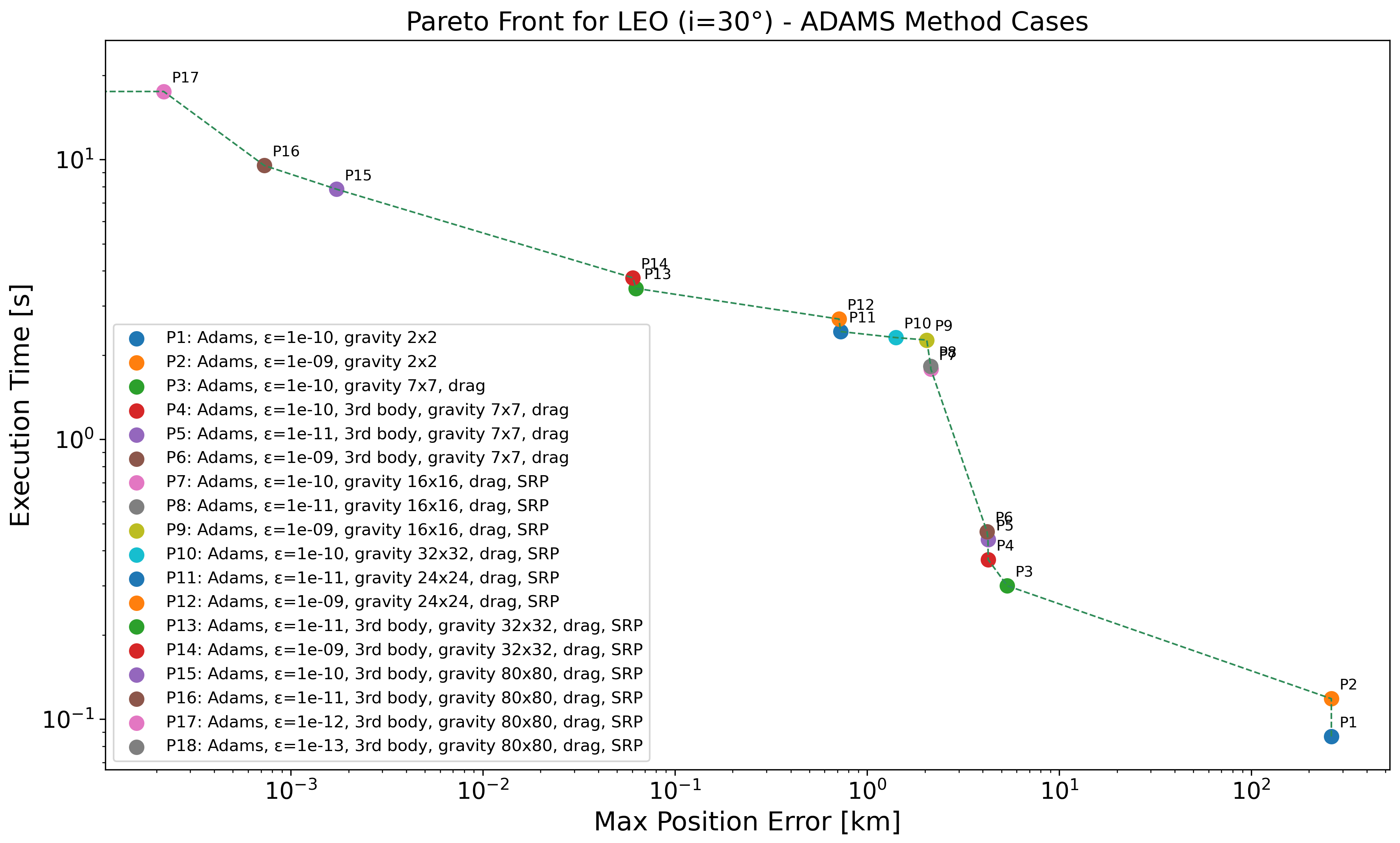

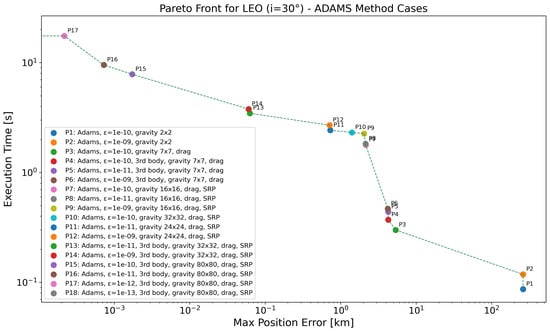

In the LEO regime with an inclination of 30° (see Figure 4 and Table 8), the overall trade-off between execution time and position accuracy mirrors the trend observed in the equatorial case. As before, low-complexity propagators such as P1 and P2, using a coarse gravity model () and loose tolerances, produce the highest errors (above 260 km) but complete within s. Accuracy improves significantly by refining the gravity model and adding perturbations, with P3 through P6 demonstrating how increasing model fidelity—e.g., moving to a gravity field and including drag and third-body effects—reduces the error below 5 km without excessive computational cost. Notably, compared to the case, some propagators here show slightly worse accuracy at similar configurations, likely due to the more complex dynamical environment introduced by orbital inclination. For instance, P4 through P6 yield position errors in the range of – km, higher than their counterparts. Conversely, the most accurate configurations—P17 and P18—achieve nearly zero error, as before, but require longer runtimes due to higher-order gravity models () and tighter tolerances (). Intermediate propagators such as P13 and P14 offer an effective balance, with errors around 60 m and runtimes under 4 s. These cases are particularly noteworthy as they incorporate all major perturbations (SRP, drag, third-body) but maintain moderate model complexity. Overall, while the Pareto front shape remains similar to the equatorial case, slight shifts in error magnitude emphasize the influence of inclination in orbital perturbation sensitivity, which can lead to surprises.

Figure 4.

Pareto-front analysis for LEO (°) regime, considering all the propagators employing ABM method. Log scale used on both axes; points with zero error are not visible, causing the Pareto front to terminate at the y-axis.

Table 8.

Pareto-front data for the LEO () case with ABM method, as depicted in Figure 4.

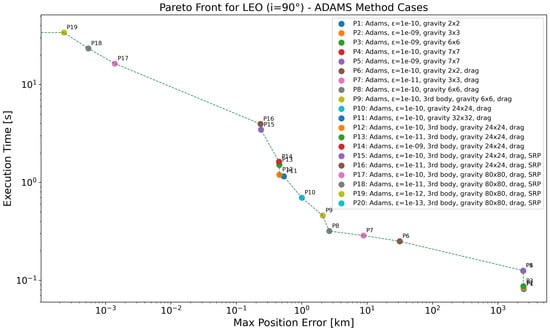

For LEO orbits with an inclination of (see Figure 5 and Table 9), the Pareto front again illustrates a clear trade-off between execution time and accuracy, though with some differences compared to the lower-inclination cases. The simplest configuration, P1, using a gravity model and a tolerance of , results in the highest position error of km but offers the fastest execution time of just s. Subsequent propagators (P2–P5) gradually refine the gravity model up to and slightly adjust tolerances, but the position error remains essentially unchanged, hovering around km—indicating that for polar orbits, gravitational perturbations alone do not yield substantial accuracy gains unless atmospheric drag is also modeled. The inclusion of drag in P6 leads to a dramatic accuracy improvement, bringing the error down to km. As seen in the and cases, the combination of drag with a progressively refined gravity model and tighter tolerances continues to significantly enhance accuracy. For instance, P10–P14, which all include drag and high-resolution gravity (up to ) with or without third-body effects, bring the position error into the sub-kilometer range. The best trade-offs in this region are observed in P11 and P12, with errors of approximately km and km, respectively. As with lower inclinations, further inclusion of SRP and a gravity model extended to (P17–P20) yields incremental gains, with the most accurate configuration, P20, achieving a near-zero position error of km, albeit at the cost of the highest execution time ( s). The curvature of the Pareto front becomes more pronounced here, showing a steep cost in time for relatively minor accuracy improvements beyond P17.

Figure 5.

Pareto-front analysis for LEO (°) regime, considering all the propagators employing ABM method. Log scale used on both axes; points with zero error are not visible, causing the Pareto front to terminate at the y-axis.

Table 9.

Pareto-front data for the LEO () case with ABM method, as depicted in Figure 5.

When comparing the three LEO scenarios, it is evident that atmospheric drag plays an increasingly dominant role in accuracy as inclination increases. At , gravitational refinement alone suffices for moderate accuracy gains, whereas at , drag becomes essential to move off the high-error plateau. The polar case also presents a longer tail on the Pareto front, requiring more computational effort to reach sub-kilometer precision—highlighting the stronger sensitivity of high-inclination orbits to combined perturbative effects.

This analysis shows that in the LEO regime, accuracy is primarily driven by model complexity, especially the inclusion of atmospheric drag, third-body effects, and high-resolution geopotential models. Beyond a certain point (e.g., in the LEO case, from P13 onward), the main avenue to improved accuracy is tightening the integrator tolerance—but this leads to a steep increase in computational cost, confirming that each gain in precision must be balanced against the practical limits imposed by runtime.

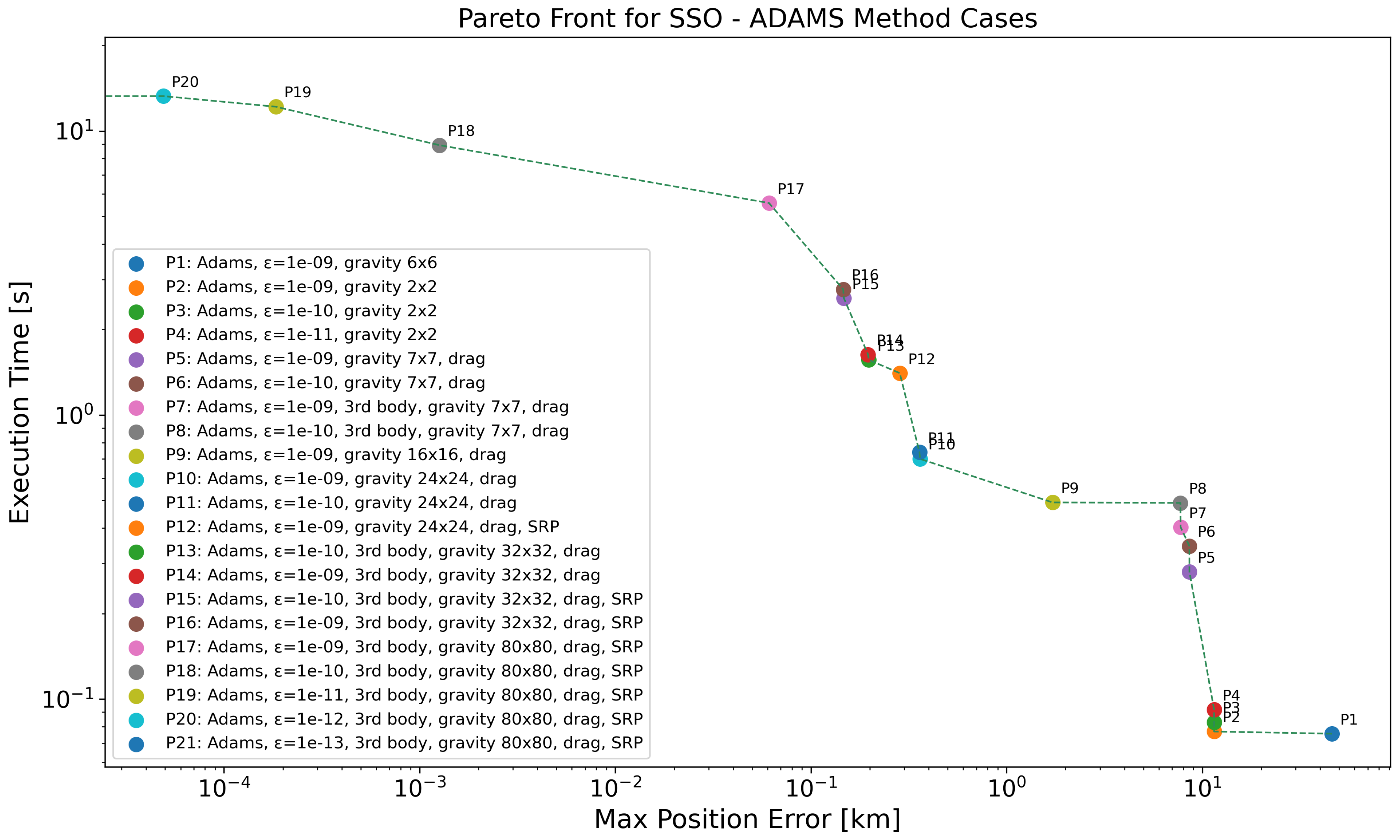

4.3. SSO Regime

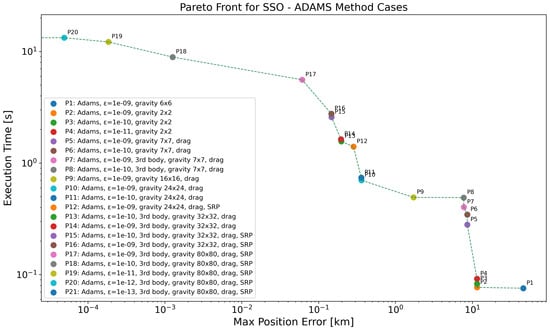

The Pareto front for the Sun-Synchronous Orbit (SSO) case, shown in Figure 6 and detailed in Table 10, compared to the LEO cases, demonstrates higher sensitivity to the inclusion and resolution of perturbation models. Notably, low-resolution gravity models (, ) yield position errors in the range of 10–45 km, indicating that such configurations could be insufficient for a more precise propagation in this regime. Increasing the gravity model resolution and enabling drag leads to substantial improvements in accuracy. For example, configurations using gravity up to with drag reduce the error to below 1 km, with marginal increases in computational cost. The addition of third-body perturbations and SRP further improves accuracy. With a gravity model and full perturbation modeling, errors are reduced to below km, while execution time increases beyond 2 s. The most accurate configurations ( gravity, full perturbations, and decreasing tolerances from to ) progressively reduce the error to machine precision ( km), albeit at a significantly higher computational cost, reaching up to 16 s.

Figure 6.

Pareto-front analysis for SSO regime, considering all the propagators employing ABM method. Log scale used on both axes; points with zero error are not visible, causing the Pareto front to terminate at the y-axis.

Table 10.

Pareto-front data for the SSO case with ABM method, as depicted in Figure 6.

Interestingly, despite using a more detailed gravity model, P1 (with the 6 × 6 gravity field) yields a higher maximum position error compared to P2 (with the 2 × 2 gravity model), even though all other parameters are identical. This is counterintuitive, as a higher-order gravity model is generally expected to produce more accurate results. However, the difference in error—approximately km vs. km—is relatively small and both results are of the same order of magnitude. A possible explanation could be numerical sensitivity introduced by higher-order gravitational harmonics, which might amplify integration errors under certain conditions, especially in combination with the very tight tolerance () used.

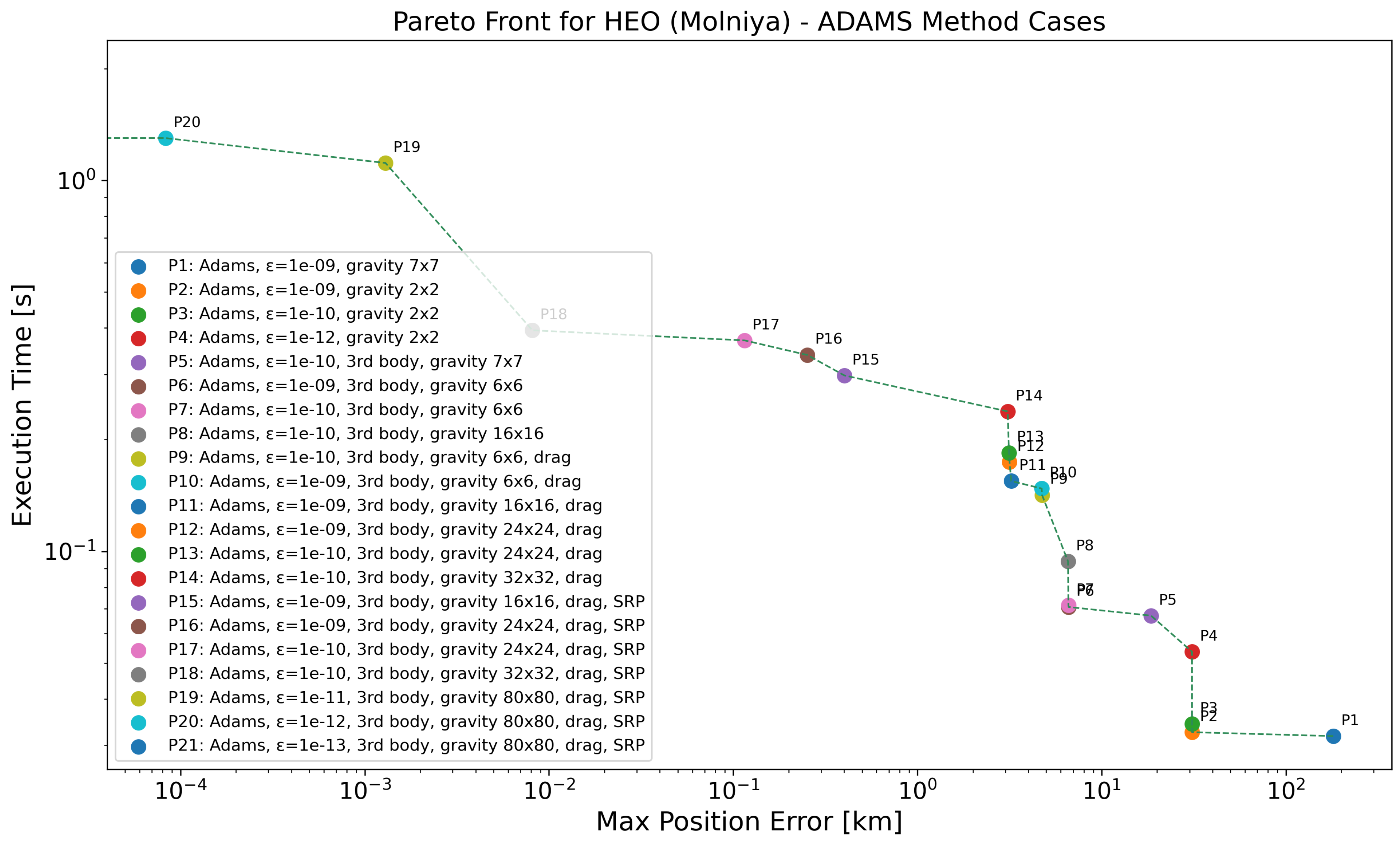

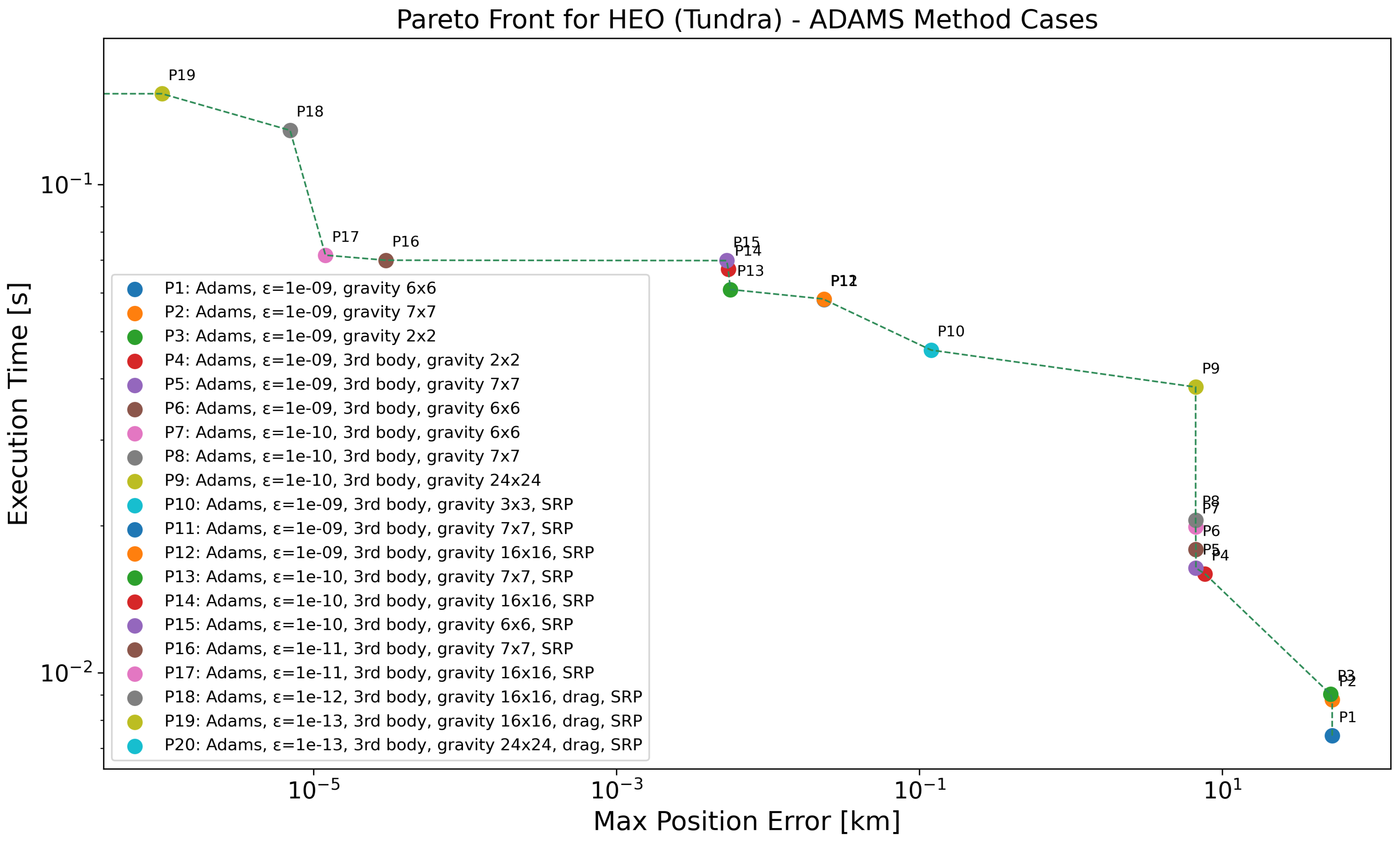

4.4. HEO Regime

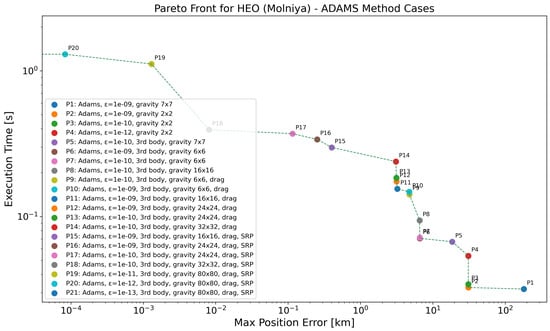

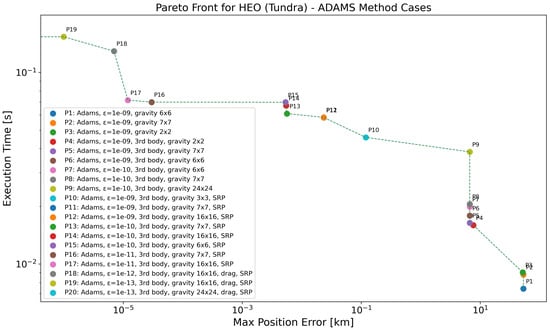

The Pareto-front analysis for the Highly Elliptically Orbit (HEO) cases can be seen in Figure 7 and Table 11 for the Molniya orbit and in Figure 8 and Table 12 for the Tundra orbit. In the case of Molniya, both the execution times and position errors are noticeably higher, especially when using low-resolution gravity models and not considering drag perturbation. The low perigee altitude makes atmospheric drag a significant perturbation here and achieving numerical convergence in such dynamic conditions can be more difficult. This reflects the complexity of accurately propagating such highly eccentric orbits. The progressive addition of perturbing forces—third-body effects, atmospheric drag, and SRP—combined with finer gravity resolutions, leads to significant improvements in accuracy, albeit at a substantial increase in computational cost. The most accurate results are achieved with full perturbation modeling and high numerical tolerances, though these configurations also correspond to the highest execution times. For the Tundra orbit, the execution times are overall lower and the position errors less pronounced, except in the case of the coarsest gravity model (), which yields significant inaccuracies. When moderate to high gravity resolutions are employed, the addition of third-body and SRP effects rapidly improves accuracy, achieving sub-kilometer and even submeter errors with moderate computational load. Compared to Molniya, the Tundra orbit appears to be less sensitive to modeling choices, allowing for more efficient propagation while still maintaining high precision.

Figure 7.

Pareto-front analysis for HEO (Molniya) regime, considering all the propagators employing ABM method. Log scale used on both axes; points with zero error are not visible, causing the Pareto front to terminate at the y-axis.

Table 11.

Pareto-front data for the HEO (Molniya) case with ABM method, as depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 8.

Pareto-front analysis for HEO (Tundra) regime, considering all the propagators employing ABM method. Log scale used on both axes; points with zero error are not visible, causing the Pareto front to terminate at the y-axis.

Table 12.

Pareto-front data for the HEO (Tundra) case with ABM method, as depicted in Figure 8.

An interesting and counterintuitive behavior is observed in the initial entries of both the Molniya and Tundra tables. Specifically, using a higher-degree gravity model ( or ) yields a significantly larger position error compared to using a lower-degree model, even though the tolerance and other force models are kept identical.

- For the Molniya case, P1 ( gravity) results in a maximum position error of km, whereas P2 ( gravity) shows a much lower error of only km.

- For the Tundra case, a similar trend is observed: P1 and P2 ( and gravity) yield errors of approximately km, while P3 ( gravity) gives a slightly better accuracy of km.

This behavior is not expected, as increasing the gravity model resolution should, in principle, lead to more accurate propagation. A plausible explanation lies in the interplay between model complexity and numerical integration tolerance. When a more detailed gravity field is used without tightening the integration tolerance accordingly (in this case, ), the propagator may fail to accurately resolve the higher-frequency gravitational variations. This can lead to the accumulation of numerical errors and poorer accuracy overall. Additionally, in highly dynamic orbits like Molniya or Tundra, a mismatch between the fidelity of the physical model and the numerical solver’s precision can exacerbate convergence issues or trigger instability in the solution. Thus, when increasing model complexity, especially for high-eccentricity orbits, it becomes essential to also refine the tolerance to maintain numerical consistency. This highlights the importance of co-designing model fidelity and solver accuracy when aiming for reliable orbital propagation.

While both orbits fall within the HEO regime, the analysis reveals distinct performance characteristics. The Molniya orbit, with its higher eccentricity and low perigee and rapid motion, imposes greater numerical challenges, requiring finer tolerances and more complex perturbation modeling to achieve precise results—reflected in longer execution times. The Tundra orbit, though still elliptical, is more stable and symmetric, enabling accurate predictions with less computational effort. This is expected, as the Tundra orbit remains at significantly higher altitudes, resulting in minimal atmospheric drag and lower sensitivity to higher-order geopotential terms. Overall, the Tundra orbit offers a more favorable trade-off between accuracy and speed, whereas the Molniya orbit demands higher computational investment to reach similar levels of precision.

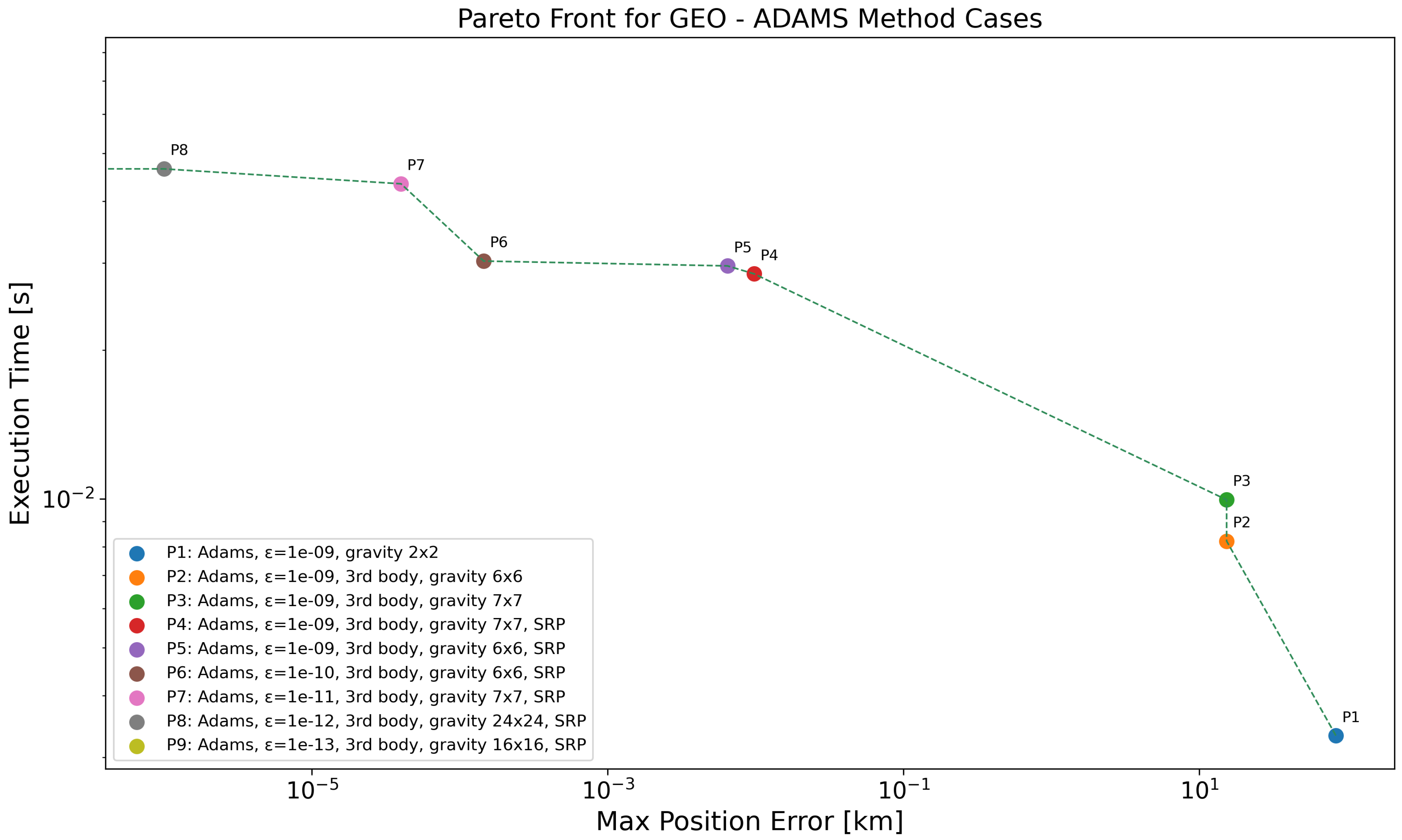

4.5. GEO Regime

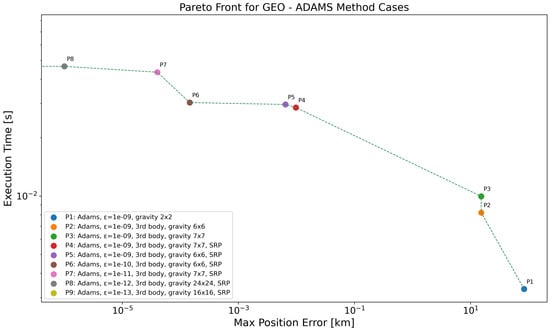

The Pareto-front analysis for the Geostationary Orbit (GEO) regime (see Figure 9 and Table 13) highlights how variations in gravity model resolution and numerical tolerance affect both accuracy and computational performance. In this case, the dominant factor influencing propagation accuracy is the gravity model resolution. The coarsest model () results in significant position errors, with P1 reaching km. Increasing the resolution to (P2) leads to a reduction in error to km. However, further changes to the model resolution (P3) do not significantly improve accuracy unless additional perturbations such as SRP are included (P4, P5). These configurations reduce the error to the meter or submeter level. Tighter numerical tolerances (P6-P9) yield progressively higher accuracies, with P9 achieving near-zero error ( km) at a still reasonable computational cost of s.

Figure 9.

Pareto-front analysis for GEO regime, considering all the propagators employing ABM method. Log scale used on both axes; points with zero error are not visible, causing the Pareto front to terminate at the y-axis.

Table 13.

Pareto-front data for the GEO case with ABM method, as depicted in Figure 9.

These results show that for GEO propagation, improving the gravity model resolution and including relevant perturbations (e.g., SRP and third-body effects) are generally more impactful for improving accuracy than refining the numerical tolerance—up to a certain point. Specifically, looking at propagators P1–P5, the accuracy improvements are mainly driven by the addition of perturbations and higher-order gravity terms, with relatively modest increases in execution time. However, from P6 on, the propagators to achieve a lower position error use lower tolerances. An observation can be made when comparing P8 and P9: although P9 achieves a significantly lower position error ( km) than P8 ( km), it uses a coarser gravity model ( vs. ) but a much tighter numerical tolerance ( vs. ). This indicates that once a sufficiently high-fidelity dynamical model is reached (as in P7 or P8), further improvements in accuracy can still be achieved by refining the numerical tolerance, even when using a slightly lower-resolution gravity model. This is consistent with the fact that the influence of the geopotential decreases with increasing altitude.

While gravity is a fundamental component in orbit propagation across all regimes, the dominant non-gravitational perturbations vary significantly. In LEO, atmospheric drag plays a major role in orbit evolution and must be accurately modeled alongside gravity to achieve reliable results. In contrast, GEO propagation is unaffected by drag; instead, accuracy depends more heavily on the inclusion of third-body effects and SRP, once a sufficiently high-fidelity gravity model is used. The results indicate that refining the gravity model from to yields substantial accuracy improvements in both regimes, but further enhancements—such as finer tolerances and other perturbations perturbations—are more critical in GEO due to the long-term accumulation of small forces. Nonetheless, all Pareto-optimal solutions in this regime require relatively low computation times, making high-accuracy propagation feasible even for time-sensitive applications.

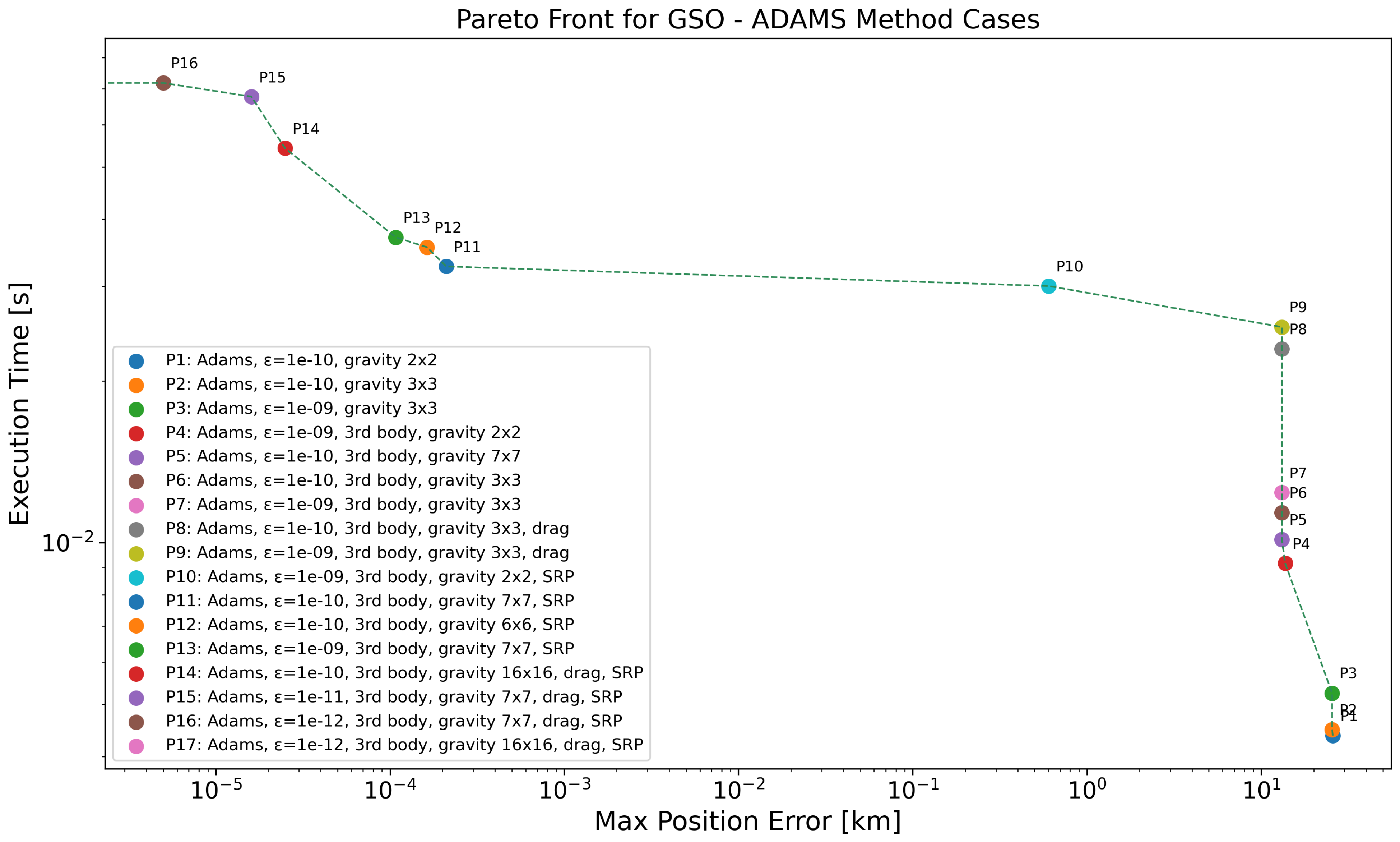

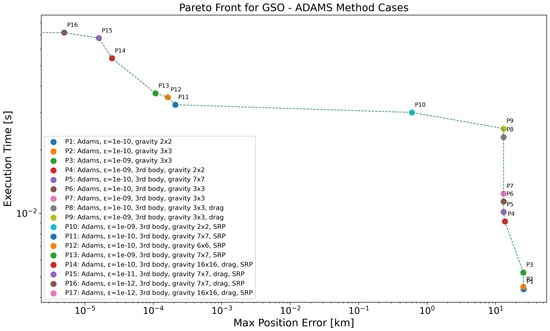

4.6. GSO Regime

Although both GEO and GSO are geosynchronous orbits, GSO trajectories—such as the one analyzed here with an inclination of —exhibit distinct dynamical behaviors that affect propagation accuracy and computational cost (see Figure 10 and Table 14). The coarsest gravity models (P1 and P2), using only and harmonics, result in position errors above 25 km, highlighting their insufficiency in capturing the complex dynamics of inclined geosynchronous orbits. Introducing third-body perturbations (e.g., P4) leads to a modest improvement in accuracy, reducing the error to around 13 km. However, varying tolerances or mid-level gravity models alone (P3, P5–P9) do not substantially impact accuracy unless key perturbations—such as SRP—are included. The most noticeable accuracy improvements occur when SRP is added (P10 onward). For example, P10 reduces the error to under 1 km by combining SRP with a coarse gravity model and third-body effects. Finer gravity models and tighter tolerances (P11–P13) bring the error into the sub-millimeter range, while the most accurate propagators (P14–P17) achieve position errors as low as km. These cases include comprehensive perturbation modeling—namely high-order gravity (up to ), SRP, drag, and third-body effects—with tolerances of or better, and yet require less than s of execution time. Overall, the results show that the combination of SRP and third-body effects is essential for achieving high-accuracy propagation in GSO, particularly when gravity models of moderate or high resolution are employed. While drag is also included in the most precise propagators, its contribution appears to be minor in this regime.

Figure 10.

Pareto-front analysis for GSO regime, considering all the propagators employing ABM method. Log scale used on both axes; points with zero error are not visible, causing the Pareto front to terminate at the y-axis.

Table 14.

Pareto-front data for the GSO case with ABM method, as depicted in Figure 10.

Despite their shared geosynchronous nature, GEO and GSO exhibit different sensitivities to perturbations. In GEO (equatorial), a moderate gravity resolution (e.g., ) combined with SRP and third-body effects is sufficient to achieve high accuracy, with drag playing virtually no role. In contrast, GSO orbits with high inclination are more sensitive to the fidelity of the gravitational model and particularly benefit from the inclusion of SRP and third-body effects. Coarse gravity models—even with low tolerances—fail to capture the complex dynamics of GSO, leading to large position errors unless complemented by these additional perturbations. Additionally, the accuracy gains in GSO require a more comprehensive force model, but come at little extra computational cost compared to GEO, making precise propagation feasible even for inclined geosynchronous missions.

4.7. Discussion Across Orbital Regimes

This study identifies the most suitable propagator for each orbital regime—VLEO, LEO, SSO, HEO (Molniya and Tundra), GEO, and GSO—by analyzing the trade-off between execution time and positional accuracy. One significant observation from our analysis is the substantial influence of gravity models with fewer terms () across all orbital regimes. Another consistent trend emerges across all cases: higher-order gravity models and selective perturbation additions are key to accuracy, but their benefits must be balanced against runtime cost. In VLEO and LEO, where drag plays a major role, the most accurate configurations require models with drag and gravity up to , with tolerances of to . In SSO and Molniya, similar gravity models and tolerances are required to mitigate the effects of both drag and SRP. For Tundra, GEO, and GSO, third-body perturbations and SRP dominate, and the most accurate solutions are obtained with gravity models of and tolerances of , achieving errors on the order of – in under 10 s. We also have observed shorter execution times required to achieve maximum accuracy for GEO and GSO orbits compared to other regimes. This discrepancy arises from the diminished influence of atmospheric drag and gravity terms in GEO orbits, allowing for simpler models while maintaining accuracy.

The findings also show that using a lower-degree gravity model (e.g., or ) results in large propagation errors across all orbital regimes. While increasing its order—to for GEO and GSO cases, to for HEO (Tundra), and to for the HEO(Molniya), SSO, LEO, and VLEO cases—significantly improves accuracy (up to ) with moderate increases in computation time, the best trade-offs are reached with gravity models of to . Importantly, no significant gains are observed for gravity models beyond , despite substantial increases in execution time. Thus, is a practical upper limit for achieving high accuracy efficiently.

4.8. Pareto Front Application

With the growing rate of conjunction alerts—driven by the sharp increase in the number of space objects in orbit—the choice of an appropriate orbit propagator becomes increasingly critical, especially when accurate and timely collision risk assessments are required. In such a context, the choice of an appropriate orbit propagator becomes critical not only for individual collision risk assessments but especially when screening large catalogs of objects to detect potential conjunctions. This task often requires propagating the orbits of thousands of satellites over several days and checking for intersection conditions among all combinations of objects with potentially close approaches. Under these conditions, the execution time of a single orbit propagation cannot be considered in isolation. Even a modest increase in computation time per object may lead to a significant cumulative impact when applied across an entire database. Similarly, this concern extends to scenarios where multiple propagation runs are needed for a single object, such as during maneuver optimization or when iteratively refining a mitigation strategy. In both cases, selecting an efficient propagator that balances accuracy and runtime can be relevant. In practical terms, high-accuracy propagators are required in scenarios such as final collision-risk assessment or maneuver verification, where meter-level precision is critical, whereas faster, lower-fidelity propagators are preferable for large-scale catalog screening or preliminary analysis where only coarse accuracy is needed.

To illustrate how Pareto-front analysis can support such decisions, consider the results shown in Figure 3 and Table 7 for the LEO equatorial case using the ABM method. Suppose a user sets a runtime constraint of under s. In this case, propagators P1, P2, and P3 are viable options. However, all three produce large position errors—ranging from 225 to nearly 291 km after seven days of propagation—making them unsuitable for precise conjunction analysis despite their speed. If the constraint is relaxed to allow execution times up to s, propagators P4 through P7 become accessible. Among these, P6 and P7 offer a much-improved trade-off, with position errors reduced to around 3 km. These configurations incorporate drag and use a gravity model of at least , demonstrating that relatively modest increases in model fidelity and runtime yield substantial accuracy improvements. For applications that can tolerate runtimes up to 2 s, propagators P8, P9, and P10 are notable. In particular, P10 achieves a position error of just km in under 2 s. These configurations include more complex dynamics, such as SRP, atmospheric drag, and third-body effects, with gravity models up to . For missions requiring the highest accuracy—such as final verification in high-risk conjunction scenarios—configurations P13 through P17 should be considered. These include full perturbation modeling with a high-resolution gravity model and increasingly strict numerical tolerances. Accuracy improves progressively from tens of meters (P13) down to near-zero levels with P17, which achieves a position error of km. However, this comes at a cost: P17 requires over 19 s to execute. A key insight from the Pareto front is the importance of selecting the most cost-effective configuration for a given accuracy target. While P14, for example, achieves sub-kilometer accuracy in 7.7 s, P15–P17 offer only marginal improvements in precision at significantly higher computational cost. This highlights the role of Pareto optimization in avoiding unnecessarily costly configurations: by selecting the optimal combination of perturbation modeling and tolerance, users can avoid computational waste without compromising on accuracy.

To quantify the operational impact, consider the task of propagating 100 satellites for one week. Using P6, which executes in s per propagation, would result in a total runtime of approximately 31 s. In contrast, using P17, the most accurate configuration, would take nearly 1940s—over an hour. This represents a speed-up factor of more than 60 times with a position error that is still within 3 km. Depending on the acceptable error threshold for the application, such efficiency gains can make the difference between a practical and an unfeasible approach, especially when hundreds or thousands of satellites must be propagated daily.

This example demonstrates how Pareto-front analysis enables mission analysts and satellite operators to make informed trade-offs between execution time and propagation accuracy, tailored to specific operational constraints. As mega-constellations in LEO continue to expand, the risk of collisions amplifies, requiring informed decisions on orbit propagators. Whether screening a large space object database for conjunctions or iteratively optimizing maneuver strategies, the choice of propagator directly influences the scalability and responsiveness of the entire process. In time-critical environments—or when processing large volumes of data—selecting the most efficient configuration becomes key to ensuring reliable and timely conjunction assessments.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a comprehensive analysis of orbit propagators and demonstrates the value of applying Pareto-front analysis to orbit propagation as a structured method to assess the trade-off between position error and computational time, identifying optimal solutions across various orbital regimes. While the technique itself is not novel, its application to evaluating propagator performance across multiple orbital regimes highlights its practical utility. In particular, the results show that the relative performance of propagators is strongly influenced by specific orbital characteristics—most notably inclination and altitude—underlining the importance of tailoring the configuration to the use case.

The systematic analysis across VLEO, LEO, SSO, HEO, GEO, and GSO orbits illustrates how Pareto fronts can support informed decisions in operational contexts where multiple propagations are required under strict time constraints, such as large-scale catalog maintenance or collision avoidance maneuver planning. Though many trends observed align with known results from the literature, this work emphasizes the need to carry out detailed performance evaluations with the specific software and numerical settings intended for operational use. General expectations based on perturbation theory alone do not suffice, as the interaction with numerical algorithm settings (e.g., tolerances and model orders) significantly affects the outcome.

The PROP-SAFE tool (Propagation analysis Software for Advanced Pareto-Front Evaluations) [19], developed in the context of this study, encapsulates this methodology, providing mission operators with an efficient means to select optimal propagator configurations based on mission-specific constraints. By combining propagation accuracy and runtime metrics in a unified framework, the tool enables faster and more informed decision-making for orbit prediction tasks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R., J.P.M., R.V. and P.J.S.G.; methodology, A.R.; software, A.R.; validation, A.R.; formal analysis, A.R.; investigation, A.R.; resources, A.R.; data curation, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.; writing—review and editing, A.R., J.P.M., R.V. and P.J.S.G.; visualization, A.R.; supervision, J.P.M., R.V. and P.J.S.G.; project administration, J.P.M., R.V. and P.J.S.G.; funding acquisition, R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by NEURASPACE Project, Contract No. 9, under Regulation (EU) 2021/241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 February 2021 and the Portuguese Recovery and Resilience Program (PRR), in component 05-Capitalization and Business Innovation, under Notice No. 01/C05-i01/2021 of the Regulation of Mobilizing Agendas/Alliances for reindustrialization. R. M. M. Ventura and J. P. Monteiro acknowledge LARSyS funding (DOI: 10.54499/LA/P/0083/2020, 10.54499/UIDP/50009/2020, and 10.54499/UIDB/50009/2020). P. J. S. Gil acknowledge Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) for its financial support via the project LAETA Base Funding (DOI: 10.54499/UIDB/50022/2020).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge all other members of the NEURASPACE project, and, particularly, other members from the IST/ISR team, for their contributions to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chow, T. Space situational awareness sharing program: An SWF issue brief. Secur. World Found. 2011, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, H.; Sang, J. An analysis of close approaches and probability of collisions between LEO resident space objects and mega constellations. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 25, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Cui, W.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, S. Self-induced collision risk of the Starlink constellation based on long-term orbital evolution analysis. Astrodynamics 2023, 7, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorge, M.; Alary, D.; Lacomba, F.; Tung, H.; Singh, B. Space Traffic Management: Large Constellations. Acta Astronaut. 2025, 229, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Parejo, C.A.; Sánchez-Ortiz, N.; Dominguez-Gonzalez, R. Effect of Mega Constellations on Collision Risk in Space. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Space Debris, Darmstadt, Germany, 20–23 April 2021; ESA Space Debris Office: Darmstadt, Germany, 2021; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Tapley, B.D.; Schutz, B.E.; Born, G.H. Statistical Orbit Determination; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, H.N.; Rahman, M.E.; Uzzal, M.S.; Kabir, H.D. Orbit Propagation and Determination of Low Earth Orbit Satellites. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2014, 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallado, D.A. Fundamentals of Astrodynamics and Applications, 4th ed.; Microcosm Press: Hawthorne, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodmann, J.; Hampf, D.; Hasenohr, T.; Humbert, L.; Riede, W.; Sproll, F.; Wagner, P. Precise Orbit Propagation for Space Debris Objects Using the Hermite Integration Scheme; ESA Space Debris Office: Darmstadt, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Caldas, F.; Soares, C.; Nunes, C.; Guimarães, M.; Filipe, M.; Ventura, R. Conjunction Data Messages behave as a Poisson Process. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.08509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenbruck, O.; Gill, E.; Lutze, F. Satellite Orbits: Models, Methods, and Applications, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallado, D.A. Long-Term Numerical Propagation for Earth Orbiting Satellites. J. Astronaut. Sci. 2020, 72, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isoletta, G.; Cimmino, N.; Opromolla, R.; Fasano, G.; Romano, A.; Basile, A. International Astronautical Federation, IAF. Orbital propagation challenges and solutions for SST fragmentation services. In Proceedings of the International Astronautical Congress, IAC, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 25–29 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Atallah, A.M.; Woollands, R.M.; Elgohary, T.A.; Junkins, J.L. Accuracy and efficiency comparison of six numerical integrators for propagating perturbed orbits. J. Astronaut. Sci. 2020, 67, 511–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.Z.; Yang, Z. A review of uncertainty propagation in orbital mechanics. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 89, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorge, M.; Harris, T.; Colombo, C.; Hejduk, M.; Fitz-Coy, N.; Sheppard, R.; Kerr, E.; Dasgupta, U.; Berend, N.; Escobar, D.; et al. Space traffic management: Improvements to spacecraft collision avoidance (COLA). Acta Astronaut. 2025, 229, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolado-Perez, J.C.; Nitta, K.; Flohrer, T.; Jah, M.K.; Martinot, V.; Pastor, A. Improvement of orbital data precision and accuracy. Acta Astronaut. 2025, 229, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, R.; Burhani, B.M.; Fantino, E. A method for accurate and efficient propagation of satellite orbits: A case study for a Molniya orbit. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 2661–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, A.; Monteiro, J.P.; Ventura, R.; Gil, P.J.S. PROP-SAFE: Empowering Space Mission Propagation with Personalized Solutions; IAF: Milan, Italy, 2024. Available online: https://iafastro.directory/iac/archive/browse/IAC-24/A6/IP/83205/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- ESOC. GODOT, ESA’s Flight Dynamics Software. Available online: https://godot.space-codev.org/community/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Moyer, T.D. Mathematical Formulation of the Double Precision Orbit Determination Program/dpodp; Technical Report; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1971.

- Picone, J.; Hedin, A.; Drob, D.P.; Aikin, A. NRLMSISE00 empirical model of the atmosphere: Statistical comparisons and scientific issues. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2002, 107, SIA 15-1–SIA 15-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battin, R.H. An Introduction to the Mathematics and Methods of Astrodynamics, Revised Edition; AIAA Education Series: Reston, VA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehlberg, E. Classical Seventh-, Sixth-, and Fifth-Order Runge-Kutta-Nystróm Formulas with Stepsize Control for General Second-Order Differential Equations; NASA Technical Report; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1974.

- Verner, J.H. Numerically Optimal Runge-Kutta Pairs with Interpolants. Numer. Algorithms 2010, 53, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESOC. GODOT, Propagator User’s Guide. Available online: https://godot.io.esa.int/docs/1.4.0/guides/propagator.html#choosing-an-integrator-and-error-tolerance (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Fehlberg, E. New high-order Runge-Kutta formulas with step size control for systems of first-and second-order differential equations. ZAMM-J. Appl. Math. Mech. Angew. Math. Mech. 1964, 44, T17–T29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, N.R.; Lourenço, J.A. Exploring Pareto frontiers in the response surface methodology. In Transactions on Engineering Technologies: World Congress on Engineering 2014; Springer: Dodrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, A. Orbit Propagator for Real-Time Operations Using GODOT, the ESA Flight Dynamics Software. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Capderou, M. Satellites: Orbits and Missions; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, M.; Tinelli, C.; Rümmer, P.; Wahl, T. An automatable formal semantics for IEEE-754 floating-point arithmetic. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 22nd Symposium on Computer Arithmetic, Lyon, France, 22–24 June 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 160–167. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.