Abstract

Civil airplanes encounter unpredictable safety risks due to uncertain environmental disturbances, mechanical failures, and pilot mis-operations. This paper develops a virtual flight method (VFM) consisting of a series of techniques including flight motion simulation, flight command simulation, flight control simulation, and flight environment simulation. Moreover, a safety perception technique is established using fuzzy safety constraints, which transfers the decoupled analysis of micro-level aircraft state parameters to the coupled analysis of macro-level global system parameters. This integrated approach enables virtual flight operations and safety situation awareness for civil aircraft within the ‘Human–Machine–Environment’ triad under the influences of complex factors. The takeoff and climb scenario of the Cessna Citation 550 aircraft is selected as a case study to validate the feasibility of the proposed safety awareness technology. Results illustrate the capability to effectively capture the aircraft’s flight characteristics and safety status of the civil aircraft under various operational conditions. The safe operational envelope within specific scenarios is also determined.

1. Introduction

Within the civil aviation transportation industry, the complexity, service life, and operational requirements of civil aircraft have been increasing rapidly, posing new challenges to the safety assessment of civil aircraft [1,2,3]. Conventional flight testing and safety assessment approaches require substantial human and financial resources, including time-consuming and labor-intensive flight tests. Moreover, it is also necessary to conduct exhaustive analysis on flight incident cases, without being able to safely replicate complex safety risk scenarios during actual flights. Recently, as more types of aircrafts enter the operational environment, the complexity of airspace has surged dramatically. Therefore, flight safety relying solely on manual processing for flight safety incidents is no longer feasible [4,5].

To address the aforementioned problem, flight simulation and safety analysis methodologies have been developed in recent years [6,7,8]. Within the aircraft safety assessment process, these technologies establish relevant mathematical models based on theories such as vehicle kinematics, aerodynamics, and flight control principles. By leveraging these models for simulation testing and analytical research, they offer significant advantages: excellent controllability, low time investment, minimal risk, climate independence, and high repeatability. This approach enables extensive simulation experiments to explore aircraft flight safety performance with reduced time and cost constraints, providing critical guidance for developing countermeasures against various flight risks encountered during actual operations.

Flight safety awareness technology represents a cutting-edge research topic in the field of civil aviation safety. It exhibits the distinctive characteristic of mutual constraints and integration between policy regulations and technical implementations, while simultaneously spanning multiple disciplines including aerospace engineering, computer technology, automatic control, and artificial intelligence [9]. Flight safety analysis employs methods that assess in-flight risks and countermeasures through analysis of aircraft flight data and construction of mathematical models. This technology can effectively enhance both flight safety and operational efficiency, encompassing interdisciplinary domains such as air traffic management, aircraft design, pilot training, and aviation safety management [10].

The identification and management of flight risks hold significant implications for aviation industry development. For pilots, this technology enables deeper understanding and assessment of flight risks, enhancing the rationality and scientific basis of in-flight decision-making to minimize accidents caused by judgment errors. For aviation professionals, systematic research on flight risks can standardize aviation safety management practices, ultimately establishing a comprehensive flight safety assurance framework spanning the entire lifecycle from design and manufacturing to operation and maintenance [11,12].

In summary, virtual flight technology integrates aerodynamic simulation, motion modeling and simulation, and flight control technologies. While accurately replicating the physical characteristics of real aircraft, it offers significant advantages over physical flight testing, including superior cost-effectiveness, enhanced safety, minimal environmental constraints, and rapid feedback capabilities. Leveraging these attributes to develop perception and analysis systems for flight safety performance enables effective complementarity with actual flight tests. At minimal engineering cost—and in conjunction with established flight safety standards and analysis methodologies—this approach facilitates comprehensive assessment of aircraft flight dynamics and safety performance across diverse operational scenarios. The resulting insights provide critical feedback to stakeholders, delivering essential theoretical grounding and technical support for optimizing aerodynamic designs, refining flight control laws, advancing safety standards, and enhancing flight safety analysis frameworks.

To address the requirements for flight performance testing and safety evaluation of civil airliners, this paper establishes a virtual flight platform within a computational environment. This platform integrates flight environment models, and aircraft systems models developed through the analysis of authentic flight data, aerodynamic parameters, and subsystem design specifications. The system acquires and processes operational data across all subsystems and event sequences, employing flight safety state perception algorithms. Based on the virtual platform’s outputs, it assesses the safety status of aircraft, determines risk levels, and predicts potential flight risk events, which enables us to execute accurate state assessments and risk mitigation procedures for flight safety incidents.

2. Virtual Flight and Safety Awareness Platform Construction Methods

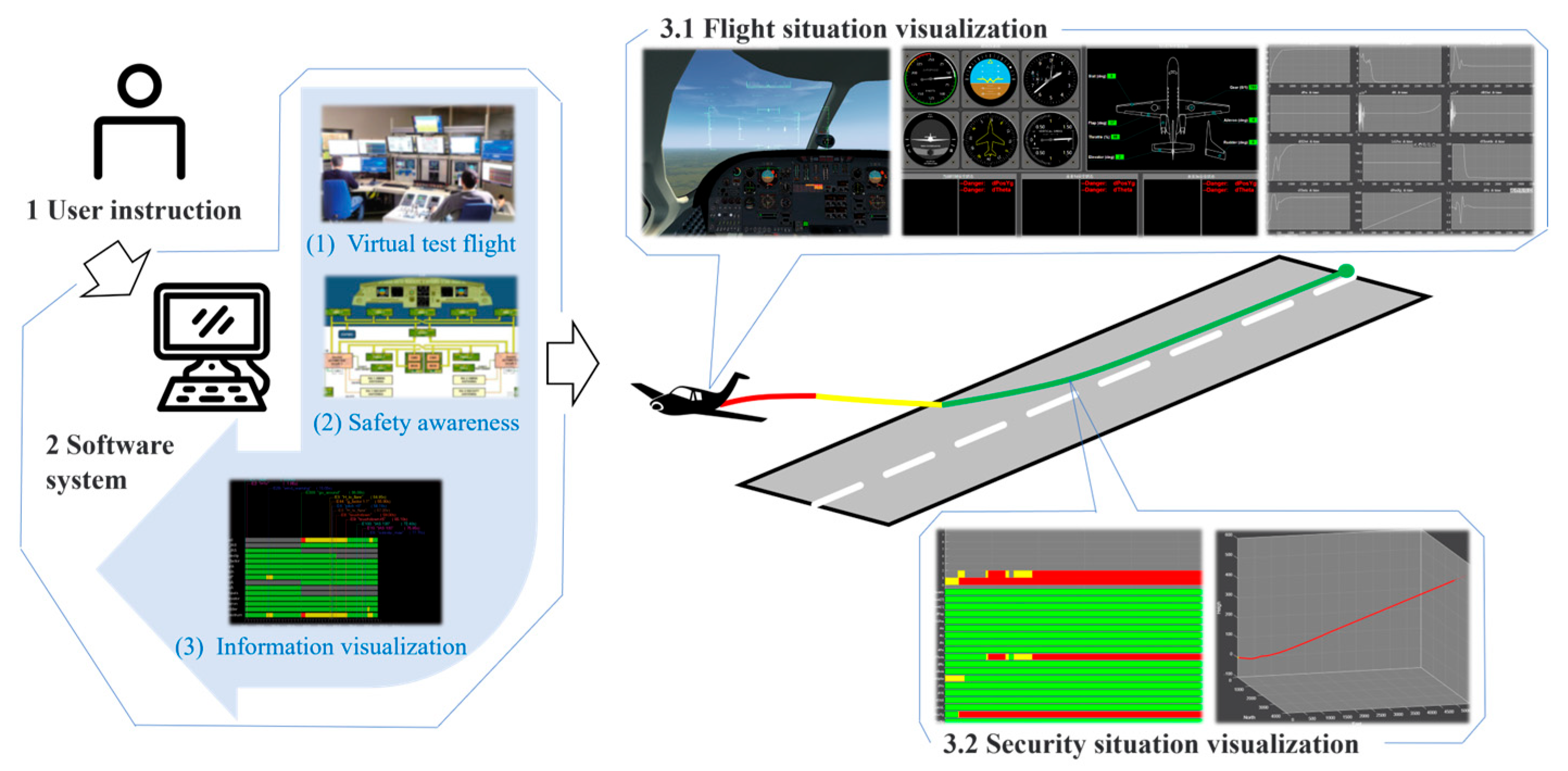

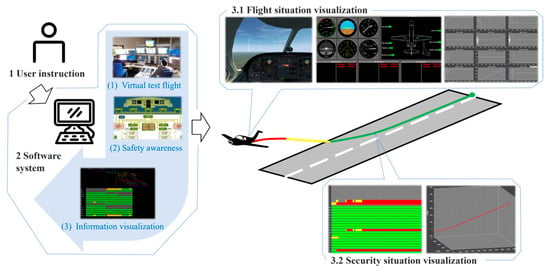

The virtual flight and safety awareness framework proposed in this paper comprises both background programs and a front-end visual interactive interface. The workflow, illustrated in Figure 1, operates as follows: First, users configure and operate through the visual interface according to their specific requirements; subsequently, the system executes the three stages—virtual flight, safety awareness, and visual display. The resulting outputs are presented in the visual interface, including flight status visualization and safety status visualization. This visual display enables users to promptly and accurately comprehend historical, current, and predicted flight safety conditions, while supporting targeted responses to flight incidents.

Figure 1.

Virtual flight and safety awareness platform workflow.

2.1. Virtual Flight Method

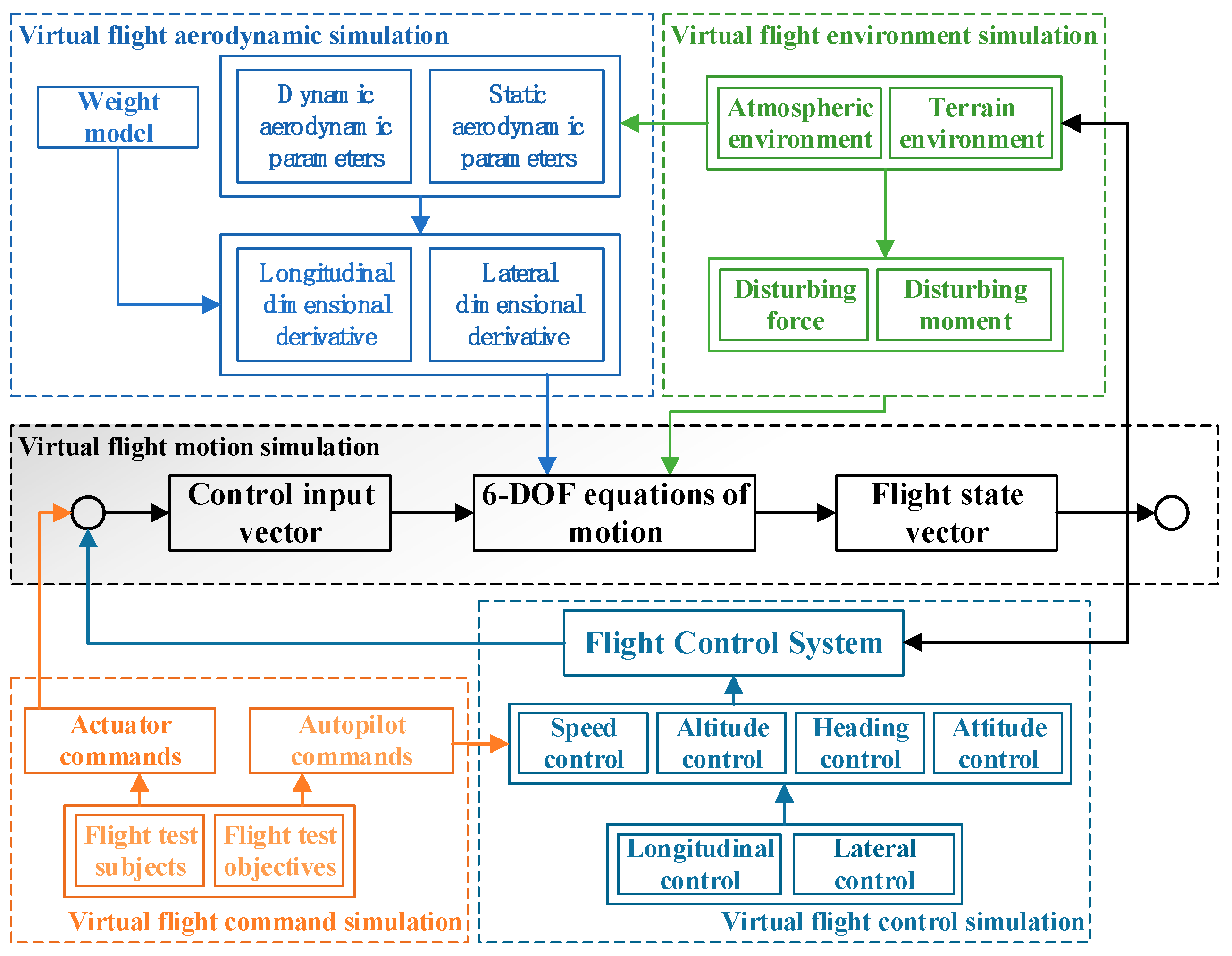

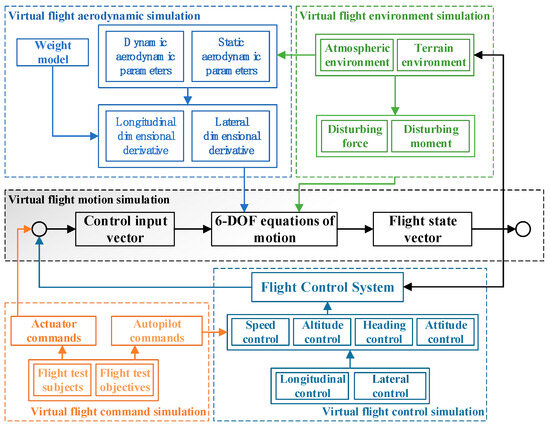

The virtual flight method in the present study employs numerical simulation techniques to integrate control command, aircraft motions, and flight environments during actual aircraft operations systematically, as illustrated in Figure 2, forming a Human–Machine–Environment System (HMES), and enables a comprehensive reflection of full-state flight risks. This approach provides data support for flight safety perception. The technical framework of the system contains four main subsystems, viz., 6-DoF motion simulation, command simulation, control system simulation, and flight environment simulation.

Figure 2.

Technical architecture of virtual flight system.

2.1.1. Motion Simulation Methods

The motion simulation system is dedicated to predict the aircraft’s real-time dynamics and behavior by a given control input. The differential equations of aircraft motion can be linearized using small-disturbance assumption, and thus decoupled into longitudinal and lateral small-perturbation equation sets as

where x and A are the motion state variable vector and matrix, and u and B are the control inputs and matrix, respectively.

Along the longitudinal direction, x and u are

where ΔV, Δα, Δθ, and Δq represent the increments in velocity, angle of attack, pitch angle, and pitch rate, respectively. ΔδT and Δδe are the increments in throttle and elevator deflection. Therefore, the matrices A and B are formulated as

where V0 is the flight velocity, μ0 represents flight path angle, g is the gravitational acceleration (9.81 m/s2), and other parameters are longitudinal dimensional derivatives.

The x and u along the lateral are defined as

where Δβ, Δϕ, Δp, and Δr are the increment of sideslip angle, roll angle, roll rate, and yaw rate, respectively; Δδa and Δδr denote the deflection increments in aileron and rudder, and thus the matrices A and B are defined as

It is necessary to compute the aerodynamic coefficients including static derivatives and dynamic derivatives in A and B. To ensure the accuracy and high fidelity of aerodynamic parameters, the static derivatives in A and B are computed using high-fidelity Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation and the dynamic derivatives are obtained using forced harmonic oscillation methods [13,14].

2.1.2. Command Simulation Methods

Command simulation is used to ensure that the aircraft can execute the intended flight test mission effectively, which is employed to simulate the operations of pilots. However, due to the complexity and randomness in modeling the pilot behavior model, it is not conducive to qualitative and quantitative research. In this paper, an idealized pilot operation model is adopted, where it is assumed that “human” can precisely execute the pre-set operations. Pilot errors and abnormal maneuvers will be specified through direct input by the user via the software platform.

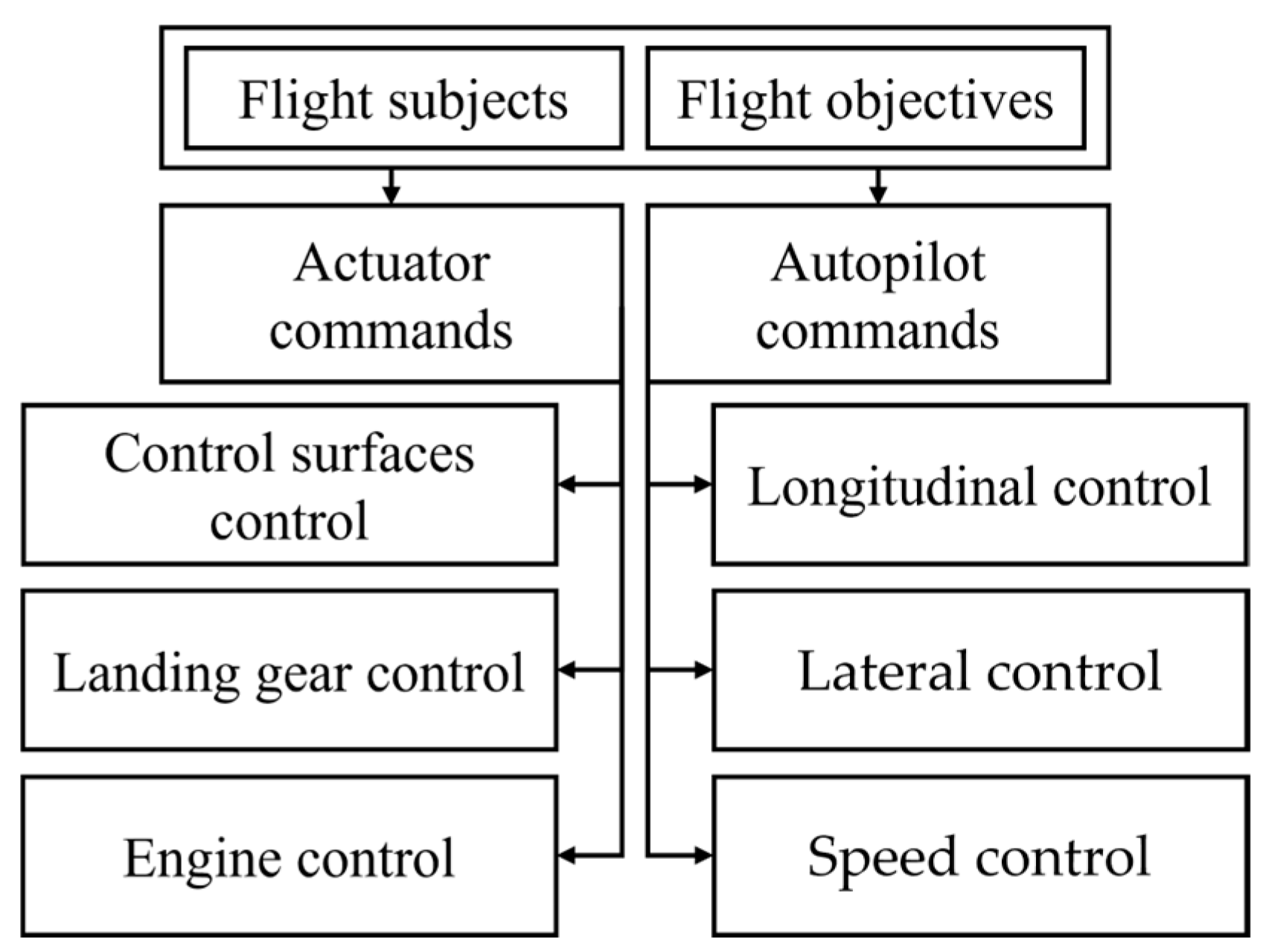

Commands are classified into actuator commands and autopilot commands, as shown in Figure 3. The actuator command is based on the requirements of the flight test subjects and takes the form of directly controlling the actuation of the aircraft’s actuators, outputting the actuation status of each actuator to the motion simulation of the aircraft. This process is used to simulate the pilot’s operations during flight and can be employed for aircraft actuator failure scenarios. For a typical civil aircraft, the actuator commands include control surface commands, engine control command, landing gear control command, etc.

Figure 3.

Actuator commands and autopilot commands.

Autopilot commands are used to send instructions to the flight control system, regulating aircraft control surfaces and throttle settings to the motion module, which enables full autonomous flight operations. The autopilot commands include longitudinal control commands, lateral control commands, and speed control commands.

2.1.3. Flight Control System Simulation Methods

The flight control system can achieve autonomous flight through a closed-loop control by inputting aircraft state parameters and autopilot commands. The aircraft state parameters are derived from the output of the aircraft motion simulation process, while the autopilot commands originate from the virtual flight command simulation module. For the sake of simplification, the present study employs a classical PID control method, and this paper tunes the parameters of the PID controller based on the critical proportional method [15].

- (1)

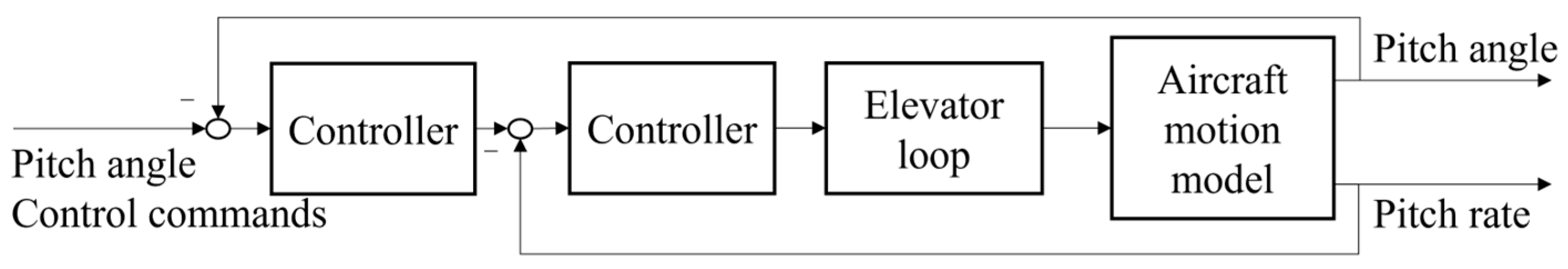

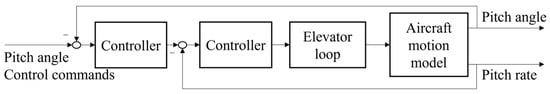

- Pitch angle control method

As the foundation for longitudinal stability and control, the pitch angle control system structure is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Pitching angle control system diagram.

When the system is in operation, the pitch angle target commands and the pitch angle feedback value are input to the controller. The controller converts the error signal into a pitch rate control signal, which is then combined with the rate feedback from the motion model to generate an error signal. The controller then converts this error signal into an elevator deflection signal.

- (2)

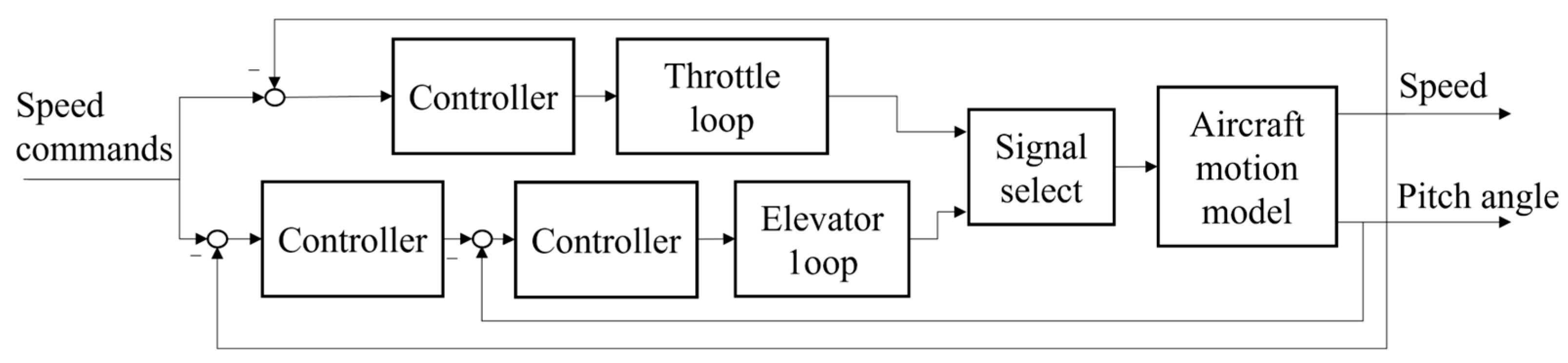

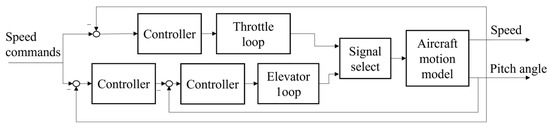

- Speed control method

Speed control systems are categorized into two distinct methods, throttle speed control and altitude speed control, based on their control approach, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Speed control system diagram.

The throttle speed control method is also known as the automatic throttle. By comparing the target speed of the aircraft’s longitudinal flight with the actual speed, the error signal is input into the controller. The controller then converts the error signal into a throttle lever signal.

The altitude speed control system is achieved through the elevator to realize the mutual conversion of the aircraft’s kinetic energy and gravitational potential energy, thereby achieving stable speed control. The speed error signal is converted by the controller into an attitude angle control command, and then through the aforementioned attitude angle control method, the elevator deflection signal is output.

A signal selection module dynamically switches between control modes based on operational requirements.

- (3)

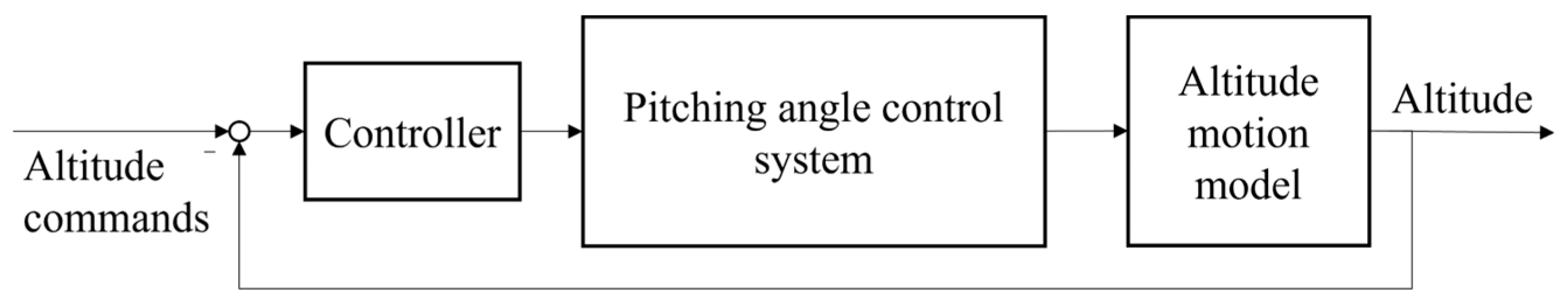

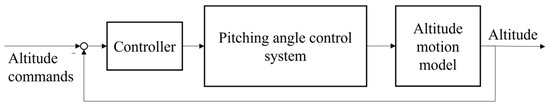

- Altitude control method

The altitude control system performs the functions of altitude stabilization and control. When conducting altitude control, the current flight altitude of the aircraft must be obtained first; the relevant motion equations are as follows:

where represents the vertical velocity, V represents the velocity, represents the path angle, θ represents the pitch angle, and α represents the angle of attack. In the altitude control system, control commands are issued in the form of step signals and ramp signals. Specifically, the direct altitude command is a step signal that represents the magnitude of altitude change, whereas the vertical speed command and flight path angle command are transmitted as ramp signals, as seen in Figure 6. The altitude error signal is converted by the controller into pitch angle control signals, which are then fed into pitch angle control system. The aircraft’s speed and heading angle are acquired, and its flight altitude is computed by Equation (6).

Figure 6.

Altitude control system diagram.

2.1.4. Flight Environment Simulation Methods

Flight environment simulation constructs an aircraft flight environment model to analyze the impact of the flight environment on the aircraft’s aerodynamics and motion, thereby assessing the safety of the aircraft within its operational environment. The environmental model developed in this paper is based on real terrain and atmospheric data, updating in real-time according to the aircraft’s flight state, thus providing a relatively accurate representation of environmental characteristics and their influence on the aircraft.

The flight terrain environment simulation method constructs a realistic terrain distribution to simulate the aircraft’s true altitude and its relative motion trend with respect to the ground during flight, thereby assessing the aircraft’s safety status. The ground elevation data is sourced from NASADEM, a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) dataset publicly released by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in 2020. This dataset encompasses all land areas between 60° N and 56° S latitude, covering the primary regions of human activity, with an elevation data resolution of 30 m. It is currently one of the most up-to-date and high-quality elevation models available. During virtual flight simulation, the aircraft’s current spatial position is input into the elevation dataset, enabling the retrieval of the aircraft’s true altitude and surrounding terrain information.

The virtual flight environment incorporates an atmospheric model designed to simulate the physical properties and dynamic behavior of the atmosphere. During operation, by inputting the aircraft’s current position and time into this atmospheric model, simulated atmospheric parameters are generated. These parameters are then used in the aerodynamic and motion simulation module of the virtual flight.

The atmospheric environment simulation model adopted in this paper is based on the CIRA-86 (COSPAR International Reference Atmosphere 1986) model. To enhance data resolution and reliability, the model is further integrated with meteorological data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) database, enabling a relatively accurate representation of atmospheric conditions at specific locations and times. During the virtual flight test simulation process, the CIRA-86 model takes the aircraft’s spatial position (including altitude, longitude, etc.) and flight time as input data, and can output corresponding atmospheric information such as wind direction, wind speed, and temperature. Although the CIRA-86 model offers relatively low accuracy, its fast computation process meets the usage requirements under general conditions. For higher-precision data, atmospheric information can be retrieved from the NOAA database based on the aircraft’s spatial position and time.

Based on the atmospheric environment model, the small-perturbation equations of motion derived earlier can be reformulated in the following form [16]:

The longitudinal small-perturbation model under wind disturbance is given by

in the equation, .

The lateral small-perturbation model under wind disturbance is given by

2.2. Civil Aircraft Safety Awareness Method

Aircraft flight is a complex process involving the integration of multiple elements and factors. The safety status of an aircraft during each phase of flight is subject to threats from multiple risks associated with the HMES. Although modern civil aircraft can ensure that a single fault does not pose a fatal threat to flight safety, it is difficult to guarantee that the crew and on-board computers can correctly handle risks and ensure flight safety when multiple risk factors accumulate and trigger a chain reaction. Based on this issue, the flight safety awareness technology studied in this paper comprehensively processes the flight characteristics and environmental information of the aircraft itself and its surrounding environment, analyzes the flight safety status of the aircraft in the risky environment under each flight path, and then feeds back this information in an intuitive and accurate form to the aircraft computer, the pilot, and relevant researchers. This helps the aircraft select a safe path to escape from the dangerous environment, thereby ensuring the highest level of flight safety [17].

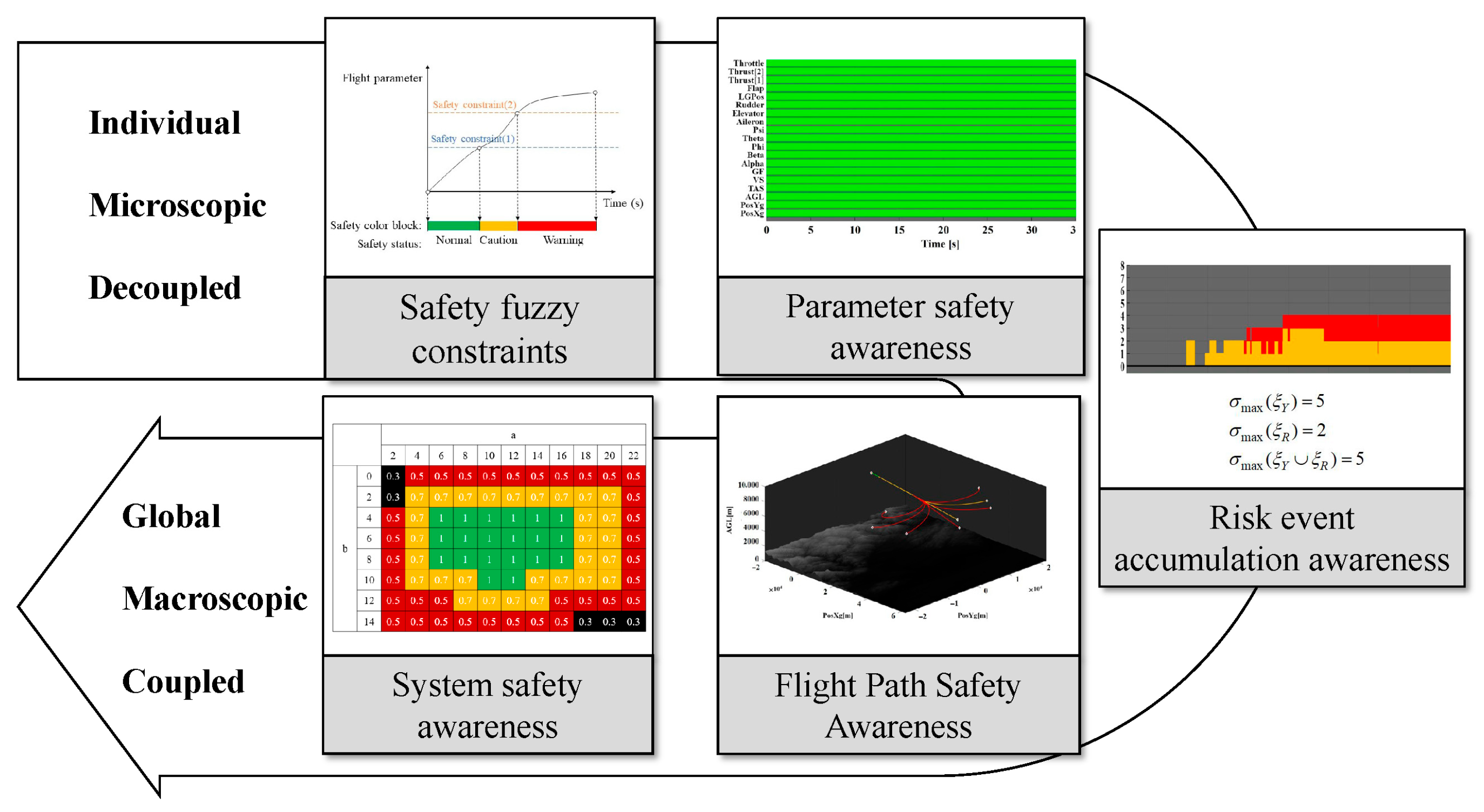

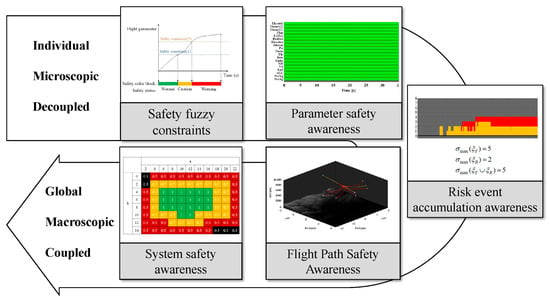

The safety awareness method transforms the aircraft’s physical state during flight into a mathematical state using established algorithms, enabling systematic analysis and processing. Simultaneously, multiple visualization techniques, such as graphs and charts, are employed to display the aircraft’s safety status, allowing relevant technical personnel to accurately and intuitively perceive the safety situation. The proposed safety awareness methodology is illustrated in detail in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Safety awareness method architecture.

The method extends from a decoupled analysis of micro-level individual aircraft parameters to a coupled analysis of the macro-level flight state of the aircraft. It can be subdivided into five perception methods: Safety fuzzy constraints, Parameter safety awareness, Risk event accumulation awareness, Flight path safety awareness, and System safety awareness [18].

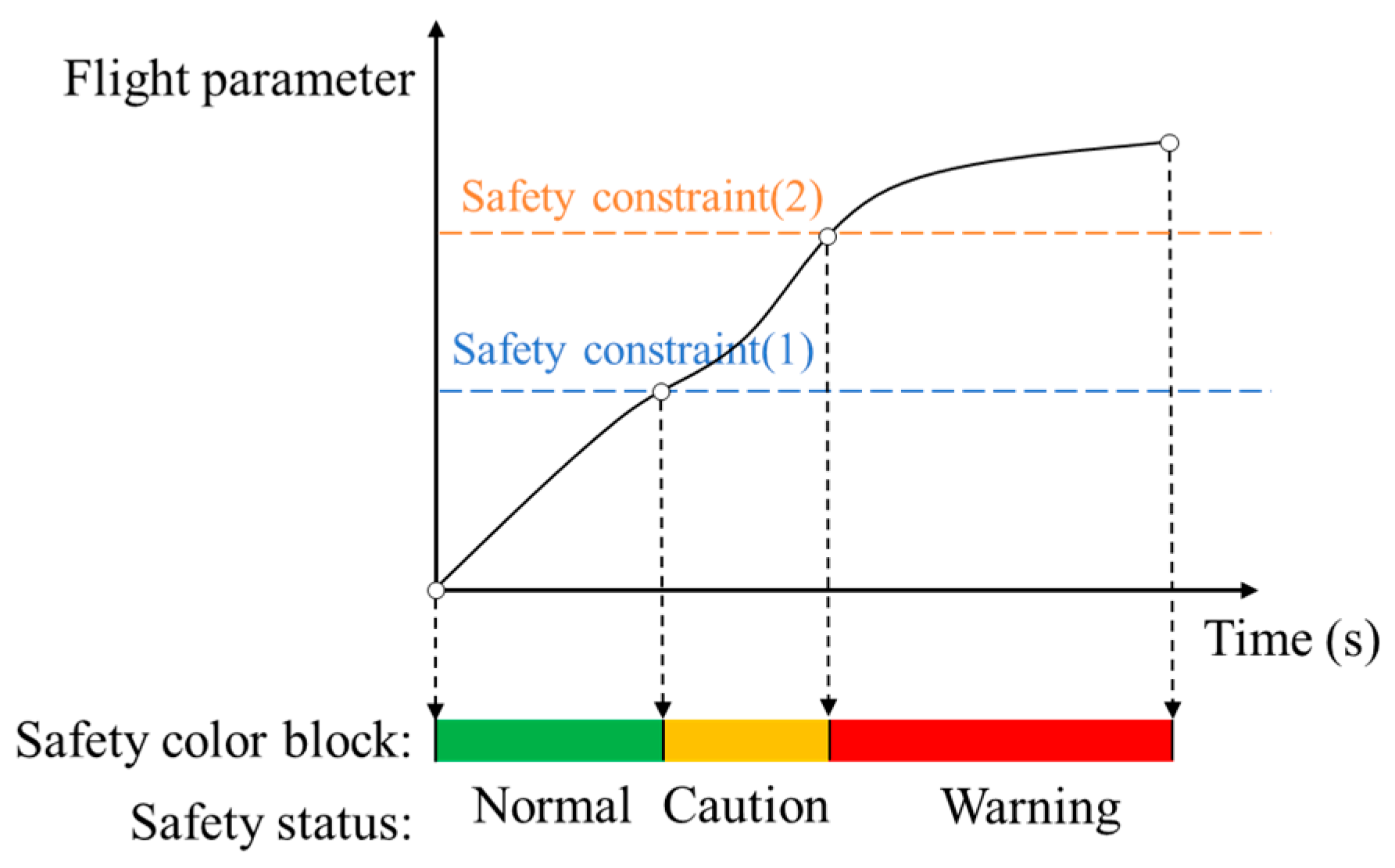

2.2.1. Safety Fuzzy Constraints

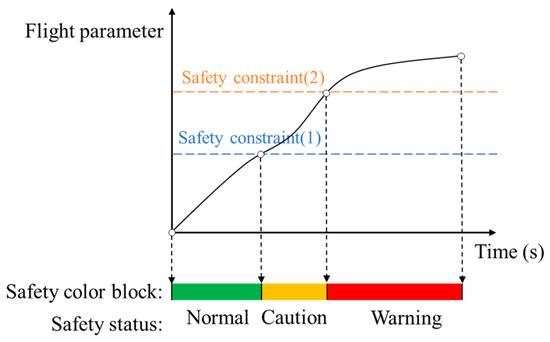

In the safety awareness process, transforming the physical characteristic of flight safety status into numerical features suitable for computational analysis constitutes the most fundamental step. The safety constraint method refers to establishing constraint intervals for each flight parameter. When a flight parameter exceeds its predefined constraint interval, it is determined that the safety characteristic of that parameter has changed, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Safety fuzzy constraint.

Figure 8 illustrates a fuzzy constraint using two or more threshold values; when the flight parameter exceeds constraint (1), its safety status is judged to change from ‘Normal’ to ‘Caution’; when it exceeds constraint (2), the safety status is judged to change to ‘Warning’ [19]. The fuzzy safety constraint method divides safety states into Normal, Caution, Warning, Disaster, and Unknown. The definition is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Safety identification and definition.

Among: these, the ‘Caution’ state indicates an abnormal flight parameter that requires attention from relevant personnel. The parameter is allowed to remain in the ‘Caution’ state for a limited period, and corrective actions should be taken, if feasible, to downgrade it to ‘Normal.’ The ‘Warning’ state indicates a significant parameter exceedance that requires immediate corrective actions to mitigate the condition; failure to do so may result in irreversible consequences for aircraft safety. The ‘Unknown’ state reflects the absence of, or inability to perform, safety assessment for the current parameter.

The specific values of the safety constraints can be derived by combining the flight manual of a particular aircraft, the airworthiness regulations, and relevant accident reports. Therefore, the safety constraint standards will change with the aircraft model, aircraft configuration (such as flap position, landing gear position, etc.), and flight mission stage (such as takeoff, cruise, approach, etc.) [20].

2.2.2. Parameter Safety Awareness

The flight parameters of the aircraft can directly reflect the characteristic performance and safety status of the aircraft. The method for perceiving parameter safety involves selecting specific flight parameters to form a dataset which is analyzed to obtain flight safety based on safety constraints. Aircraft flight is a complex process involving the integration of multiple factors, resulting in a large number of flight parameters that are interrelated and have strong coupling characteristics. According to the source of the parameters, they can be classified into three categories:

- Flight vehicle status parameters: such as the position of the flight vehicle, attitude angles, flight speed, etc.;

- Flight environment parameters: such as wind speed, atmospheric pressure, atmospheric temperature, visibility, etc.;

- Pilot (control system) control parameters: such as control surfaces actuation, landing gear retraction and extension, throttle position, etc.

It is difficult to detect all flight parameters during actual flight tests or virtual flights, and the subsequent analysis and processing of the large dataset is also quite challenging. Therefore, specific flight status parameters were selected to form a dataset for safety perception calculation. The flight safety critical parameters should satisfy the following characteristics in an ideal state:

- The key parameters and aircraft safety are mutually necessary and sufficient conditions. That is, when the flight safety is abnormal, the key parameters will also be abnormal under the safety constraint. Conversely, when the key parameters of the flight are abnormal under the safety constraint, it indicates that the flight safety has also experienced an abnormal situation.

- The key parameters have a weak coupling relationship. The additional impact resulting from the superposition of multiple parameters is relatively small. For instance, when multiple key parameters are in the critical safety state, the flight safety should also be in the critical safety state, and it will not deteriorate due to the coupling effect.

Based on the above analysis, the key parameters selected for flight safety awareness in this paper are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Safety awareness parameters definition.

2.2.3. Flight Path Safety Awareness

The awareness of flight path safety status involves two aspects: flight path of the aircraft and overall safety status of the aircraft. Among them, the flight path data directly comes from the flight path of the aircraft in the virtual flight process; the overall safety status awareness of the entire aircraft is achieved through the methods based on safety fuzzy constraints and parameter safety awareness, where the safety of the entire aircraft is calculated by the local safety status of each key parameter. The calculation method of the overall safety status of the aircraft at a certain moment is as follows:

where Lint is the safety status of the entire aircraft, and LPosXg, LPosYg, LAGL, LCAS, Lint, LVS, LGF, LAlpha, etc., are the safety statuses of each of the key parameters, that is, ξG, ξY, ξR, ξB, ξW.

Meanwhile, for each safety state, the degree of danger of the state increases in sequence as follows:

where the ‘Disaster’ state is successively greater than the ‘Normal’ state, ‘Unknown’ state, ‘Caution’ state, and ‘Warning’ state.

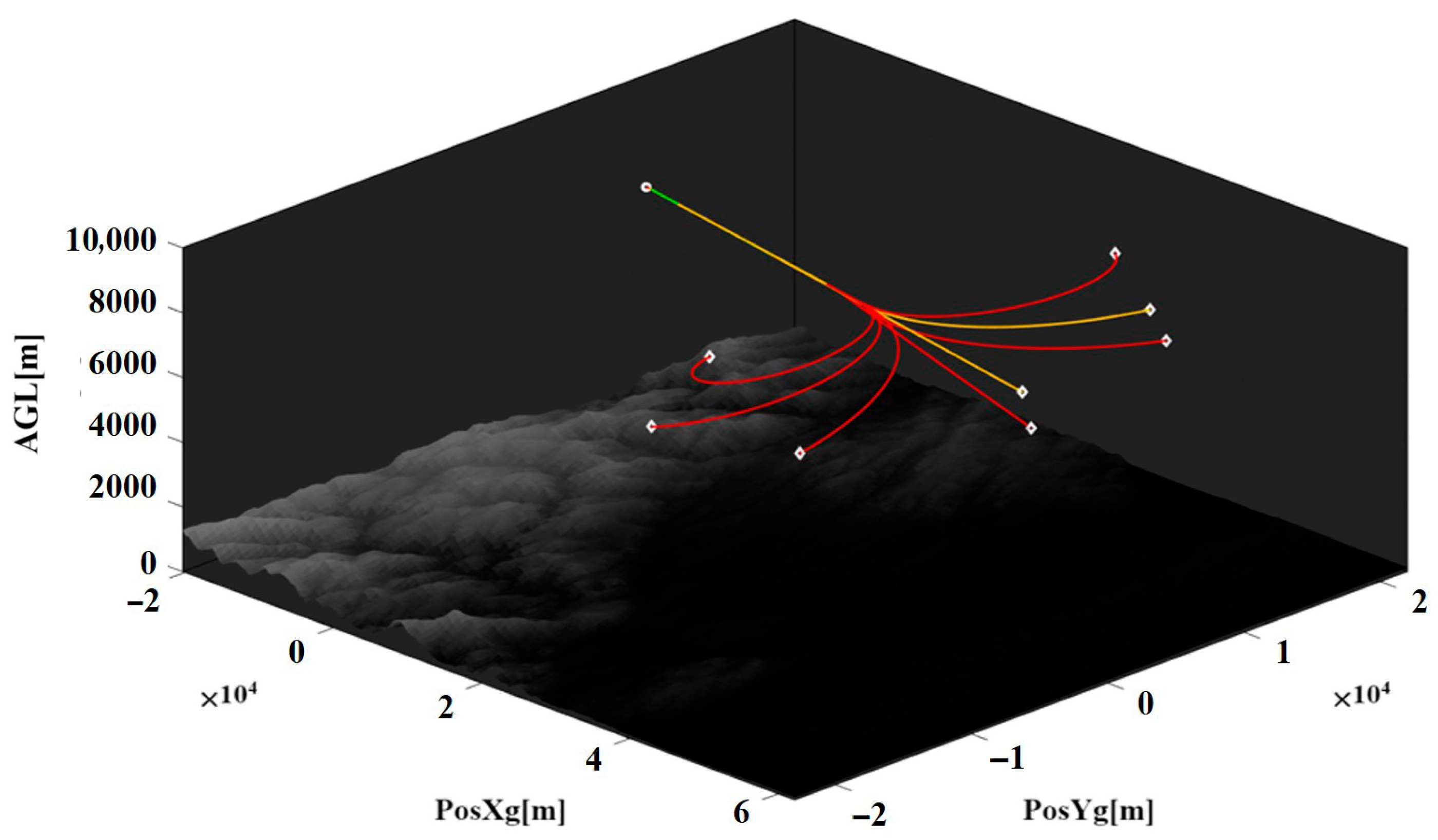

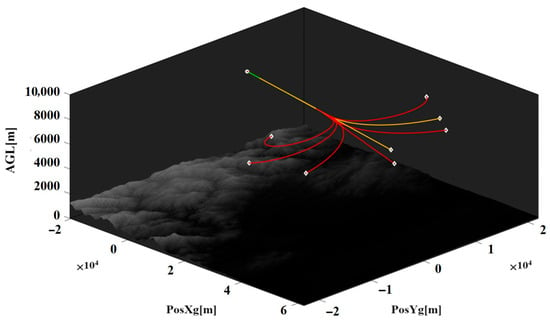

Therefore, at a certain moment, the overall safety status of the aircraft is determined by the most dangerous safety status among all the parameter safety statuses. A flight path map is drawn based on the position of the aircraft, and the color of the flight path is assigned according to the overall safety status of the aircraft. This is presented in a three-dimensional stereoscopic graphic visualization form, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Flight path safety status diagram.

The figure shows the safety status of eight flight paths with different descent rates and heading. The white dots represent the starting points of each flight path, and the white rhombuses indicate the endpoints of each segment of the flight path. The diagram simultaneously displays the actual terrain and is drawn as a three-dimensional surface grid diagram at the corresponding position. By using the above methods, the motion status of the aircraft and the overall safety status of the aircraft can be displayed and analyzed.

2.2.4. Safety Coefficient

The safety coefficient detects and counts the caution and warning states during the flight process, calculates the aircraft safety status using mathematical methods, and finally presents the data in a visual way for display. The safety coefficient can be calculated by the following equation:

where ΔtR represents the sum of the warning time for each parameter, ΔtY represents the sum of the caution time for each parameter, ΔtB represents the sum of the disaster time for each parameter, ΔtG represents the sum of the normal time for each parameter, kY is the weight coefficient for the warning state, and kG is the weight coefficient for the disaster state. The calculated safety coefficient ranges between 0 and 1. A value closer to 1 indicates a safer flight condition, while a value closer to 0 indicates a more hazardous flight condition.

3. Case Study

3.1. Test Aircraft, Flight Environment and Subjects

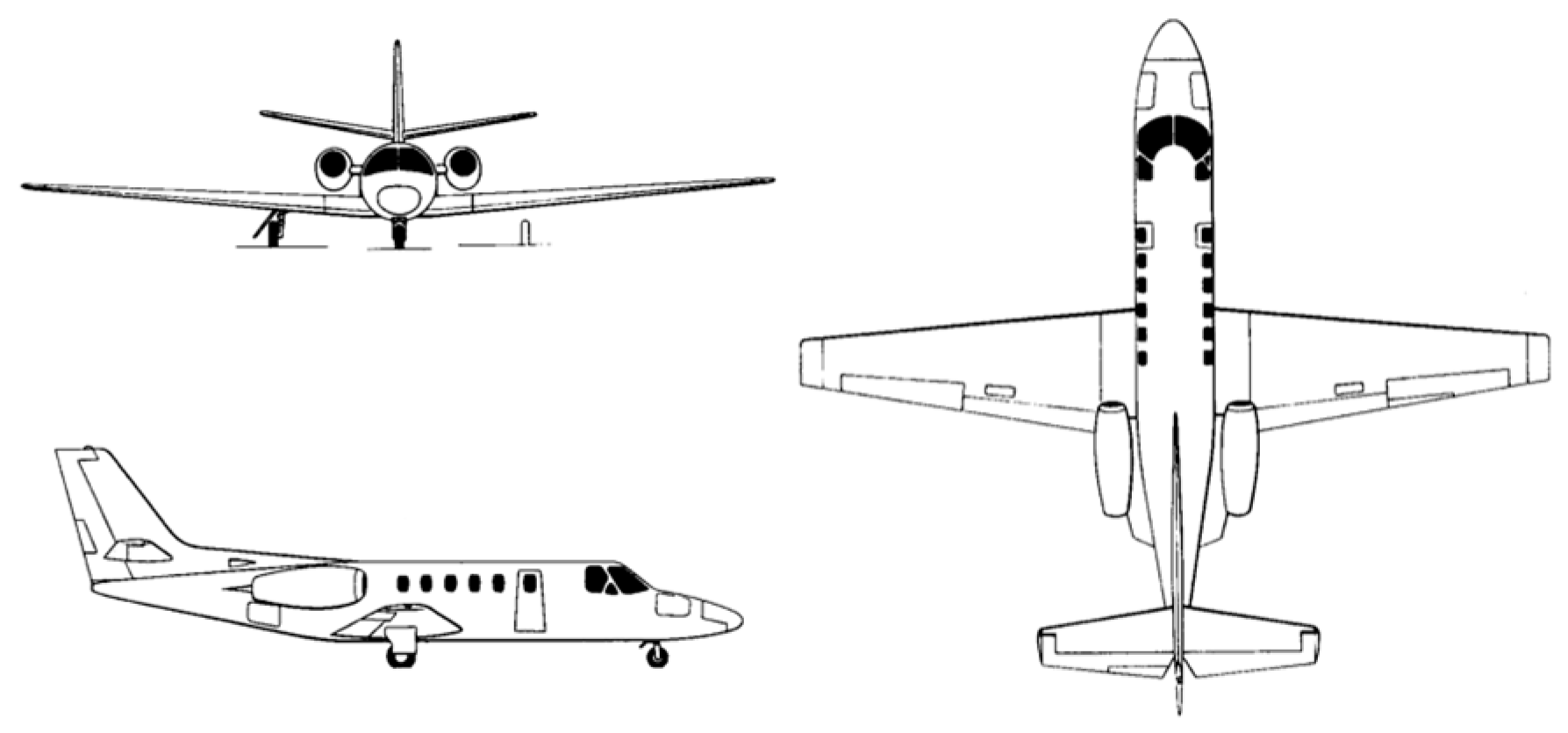

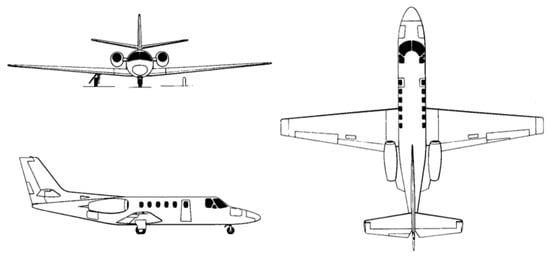

Based on the method described above, this paper developed a visual platform for virtual flight and safety awareness applications of civilian aircraft in the Python (version 3.11.14) programming environment. The takeoff and climb flight subject of the Cessna 550 Citation II twin-engine turbofan medium-sized business jet, as schematically shown in Figure 10, is selected as the case study.

Figure 10.

Three view of Cessna 550.

To establish a virtual flight test model for the Cessna 550, taking into account the nonlinear characteristics caused by variations in speed and angle of attack during takeoff, a piecewise linearization method is employed to construct a nonlinear motion model. Specifically, multiple linearized equations of motion are developed based on different speeds and angles of attack. The aerodynamic derivatives of the Cessna 550 under certain speeds and angles of attack are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Aerodynamic derivatives of Cessna 550.

The test flight airport is Nanjing Luko International Airport. The airport’s elevation is 49 ft. The runway selected is Runway 06, which is 11,800 ft long and 148 ft wide. The airport wind conditions are 126°M, 14 knots.

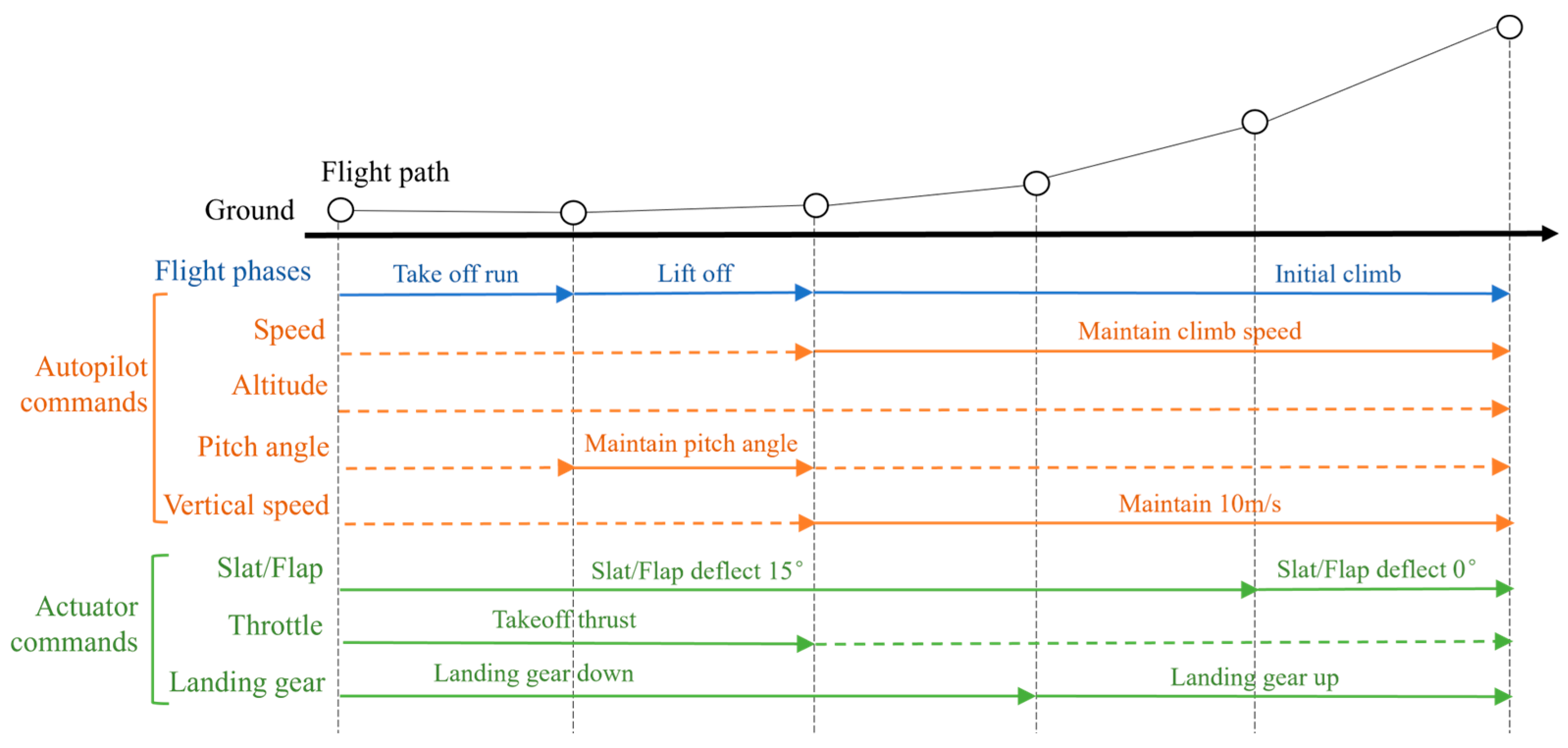

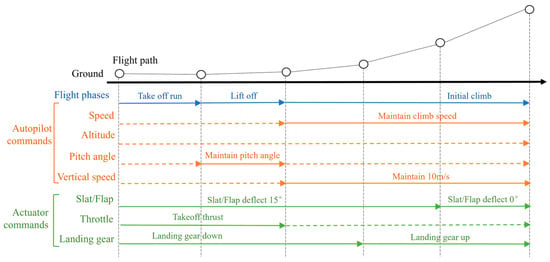

The flight subjects are selected as the takeoff and climb phases of civilian aircraft, which are prone to accidents. The flight process and control instructions of the aircraft during this stage are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Flowchart of takeoff and climb path and control commands.

During the takeoff run phase, the aircraft first accelerates from a stationary state to the rotation speed (VR). At this point, the flap deflection is 15°, the engines maintain takeoff thrust, and the landing gear is in the down and locked position. Once the aircraft reaches VR, the pitch angle automatic control command is activated to maintain the takeoff pitch altitude. After the aircraft takes off, the auto throttle is engaged to maintain the climb speed, the vertical speed control is activated to maintain a vertical speed of 10 m/s, and the landing gear will be retracted once the aircraft achieves a positive climb rate. Thus, the aircraft takeoff process is completed.

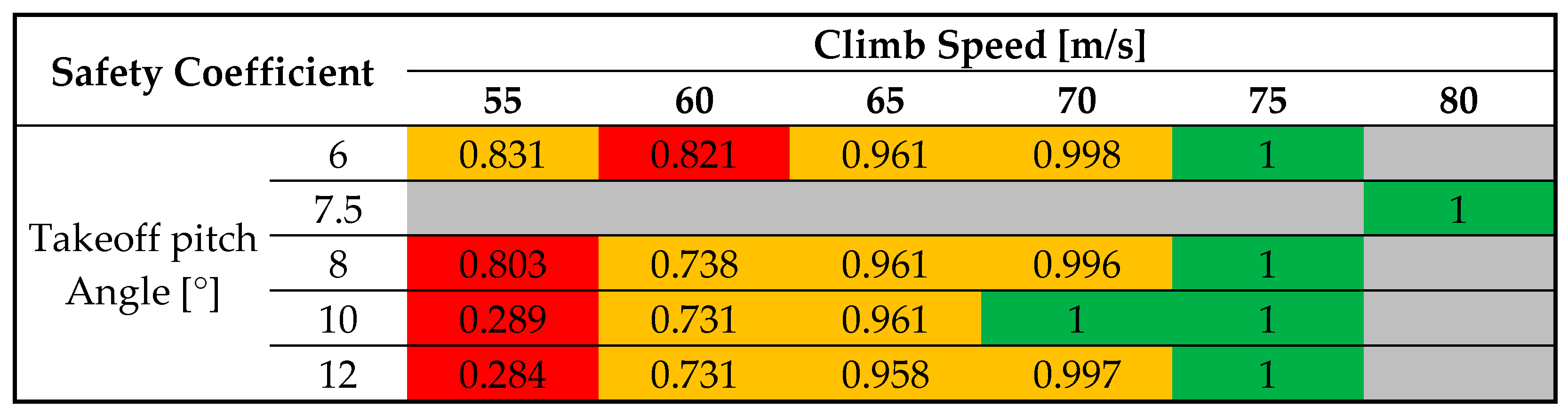

Based on the above content, the takeoff rotation pitch angle and climb speed of the aircraft are selected as the test variables in this study. The test parameters for the aircraft’s takeoff pitch altitude range from 6° to 12°, with values taken at intervals of 2°; the test parameters for the climb speed range from 55 m/s to 75 m/s, with values taken at intervals of 5 m/s; the simulation is terminated when the simulated time reaches 40 s. A total of 20 flight test scenarios are conducted by combining two variables, as shown in Table 4. In addition, a reference flight test is added, where the flight control parameters are set according to the Cessna 550 flight manual and the civil aircraft takeoff standard procedures, and the takeoff pitch altitude is 7.5° and the climb speed is 80 m/s.

Table 4.

Parameters and numbers of test scenarios.

The fuzzy safety constraints for some parameters used in safety awareness are presented in Table 5. Among them, the constraint values for PosXg and PosYg are determined based on aircraft dimensions, airport dimensions, and takeoff run distance; the aircraft’s airspeed TAS is established according to the maximum operating speed and stall speed specified in the flight manual. Data such as pitch angle, angle of attack, and control surface deflection angles are determined with reference to the climb pitch angle, stall speed, etc., outlined in the manual, while the remaining parameters are determined by referencing data from the takeoff process of conventional aircraft.

Table 5.

Fuzzy safety constraints of Cessna 550.

3.2. Analysis of Typical Flight Test Results

Among the 21 flight test scenarios mentioned above, 2 typical ones are selected for detailed analysis and result presentation. These are the F_R standard takeoff and climb procedure, and the non-standard conditions of F_5510.

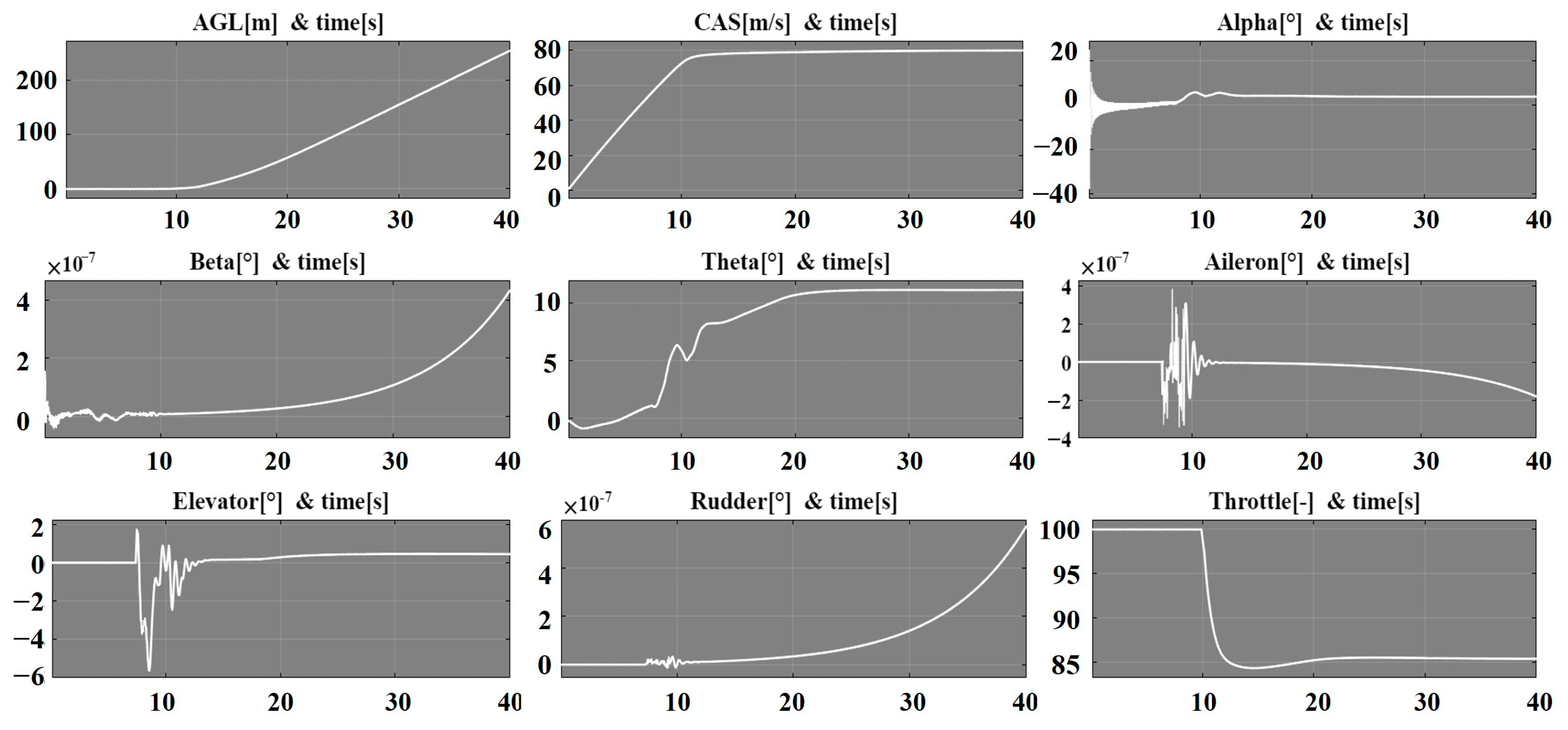

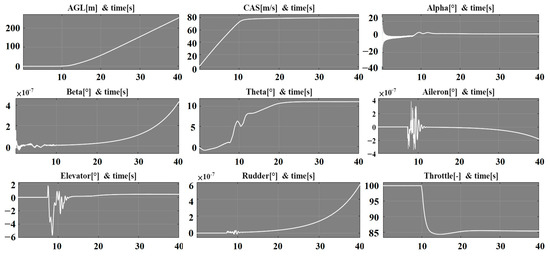

3.2.1. Standard Takeoff and Climb Procedure F_R

The graph of the key state parameters of the F_R is shown in Figure 12. During the takeoff run phase, the flight speed steadily increases and reaches the takeoff rotation speed around 7 s, entering the takeoff rotation phase. The elevator is activated to control the nose of the aircraft to rise. As the angle of attack increases, the lift force on the aircraft increases. Before reaching the specified takeoff pitch angle, the main wheels of the aircraft leave the ground, and the aircraft enters the initial climb stage. It reaches the set climb speed around 20 s and establishes a stable climb. The changes in various parameters become stable, and the aircraft takes off successfully.

Figure 12.

Key state parameters graph of the F_R.

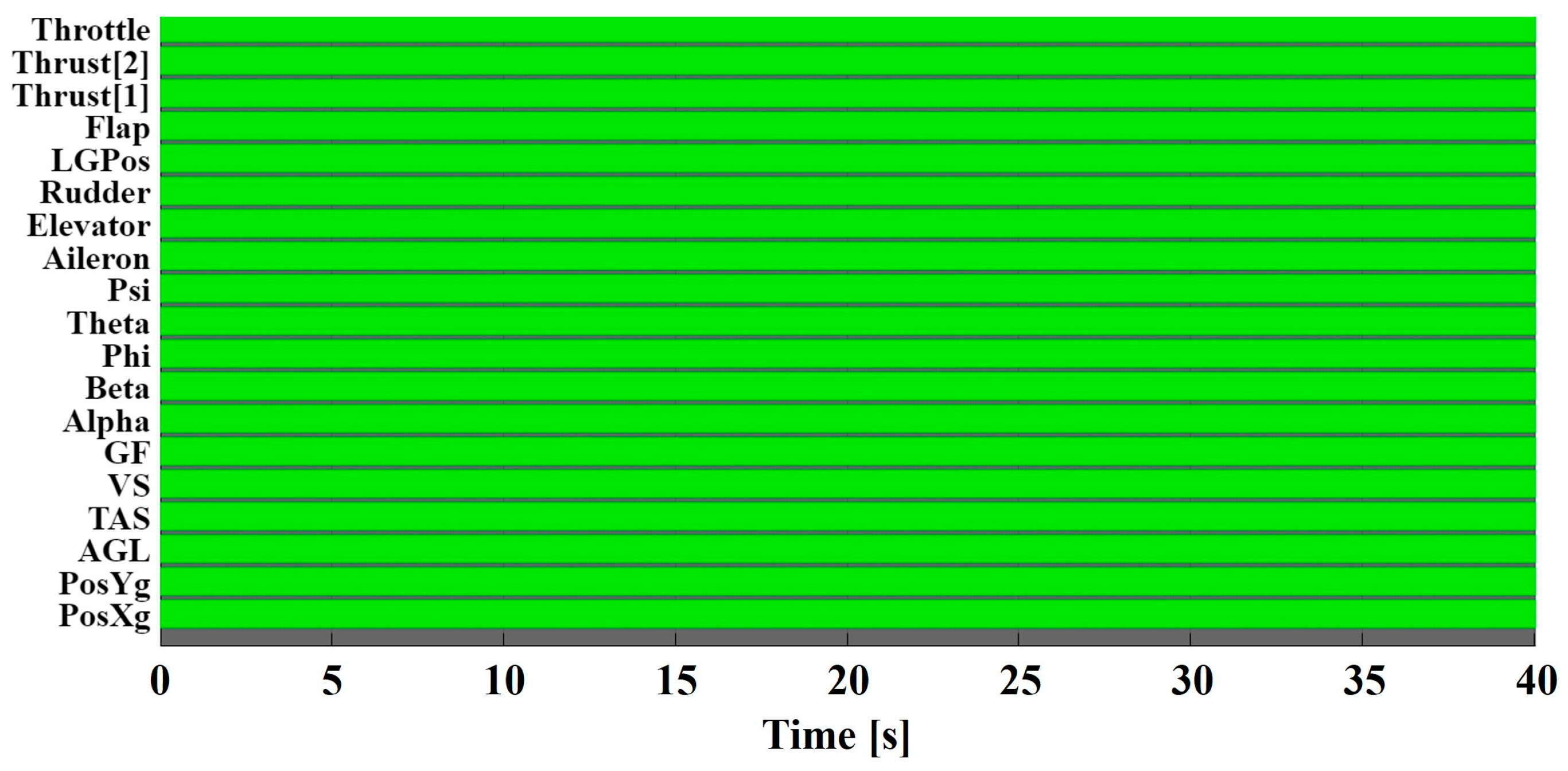

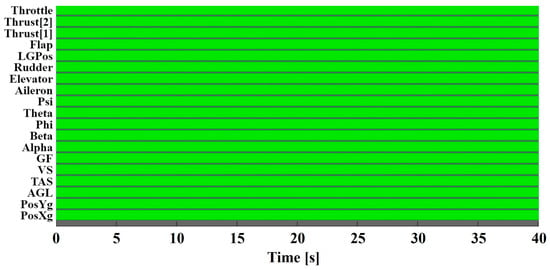

Figure 13 shows the safety awareness result of each parameter. It can be seen that during the entire virtual flight, no abnormal safety states occurred for any of the key parameters. Therefore, it can be concluded that at a pitch angle of 7.5° and a climb speed of 80 m/s, the aircraft completed the takeoff and climb process in a safe state.

Figure 13.

Parameter safety awareness of the F_R.

3.2.2. Non-Standard Takeoff and Climb Procedure F_5510

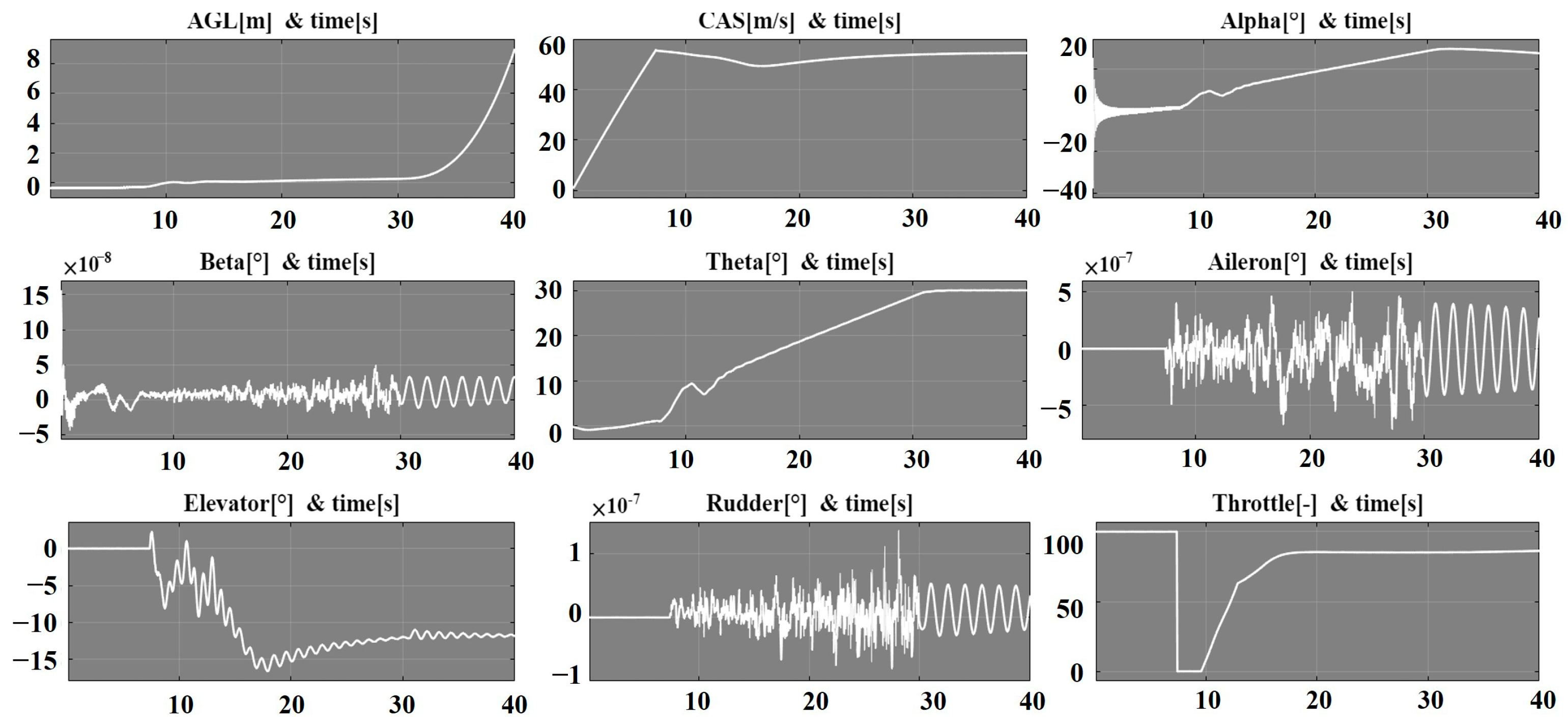

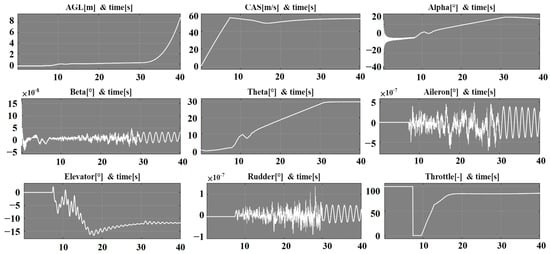

Figure 14 shows the graph of the key parameters of the F_5510. During the takeoff run phase, the aircraft reaches the rotation speed around 7 s, entering the takeoff phase. Around 10 s, the aircraft’s pitch angle reaches 10°. Approximately 3 s later, the main wheels of the aircraft leave the ground, and the aircraft enters the initial climb phase. At this point, the aircraft’s lift is relatively low, unable to support the climbing. The flight altitude remains slightly above the ground for a period of time afterwards. During this phase, due to the aircraft’s low airspeed, it cannot meet the vertical speed.

Figure 14.

Key state parameters graph of the F_5510.

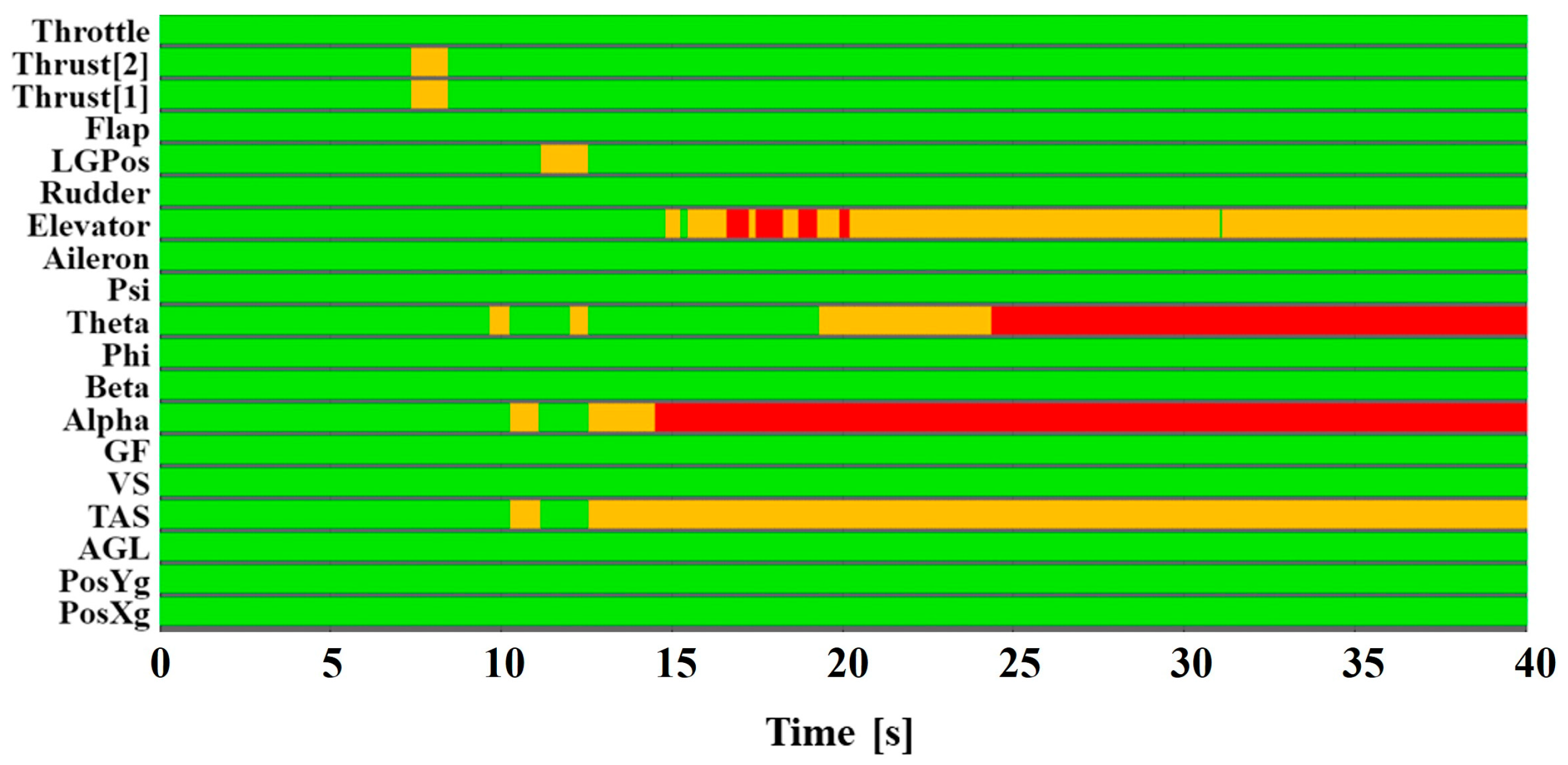

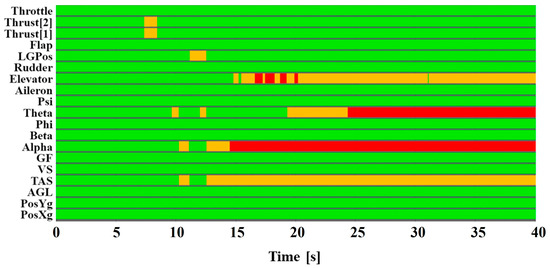

Figure 15 shows the safety awareness result of each parameter. At around 8 s, due to the automatic throttle system reducing the throttle position to the minimum, the ‘Caution’ state occurs. After 10 s, the pitch angle and angle of attack of the aircraft show abnormality, gradually deteriorating from the ‘Caution’ to ‘Warning’ state. At the same time, the elevator deflection also exceeds the limit and presents an abnormal state. After the aircraft takeoff at 10 s, the flight speed remains low and is close to the stall speed, remaining in ‘Caution’. In conclusion, it can be judged that the relevant parameters of the aircraft are severely exceeding the limit, the aircraft state is very dangerous, and a fatal accident is about to occur. The aircraft cannot complete the safe takeoff and climb process under these set parameters.

Figure 15.

Parameter safety awareness of the F_5510.

3.3. Analysis of Test Results for All Flight Test Scenarios Results

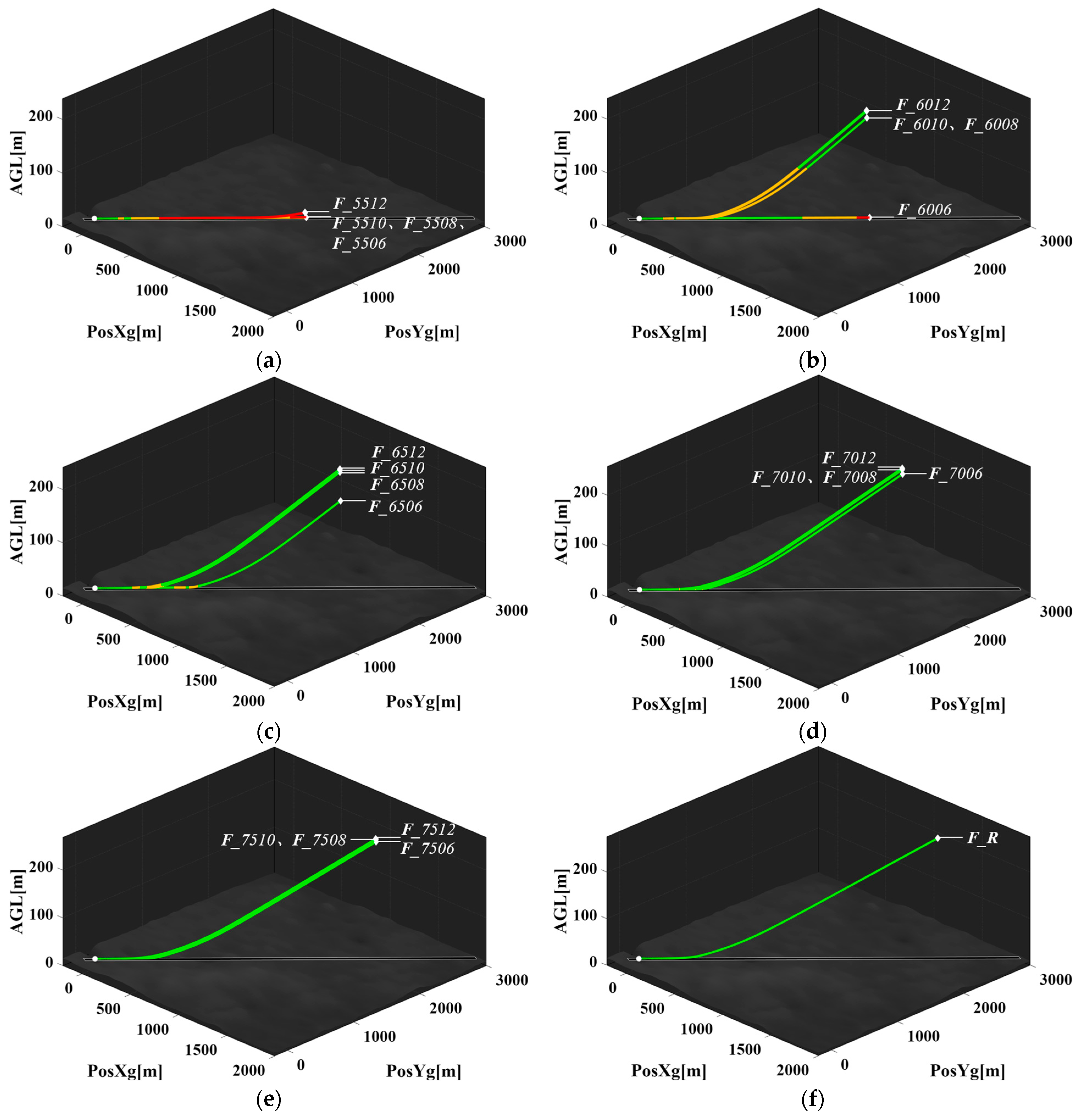

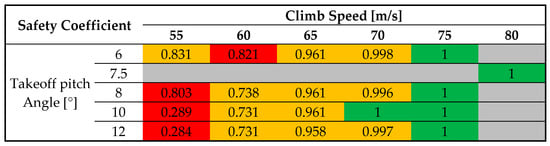

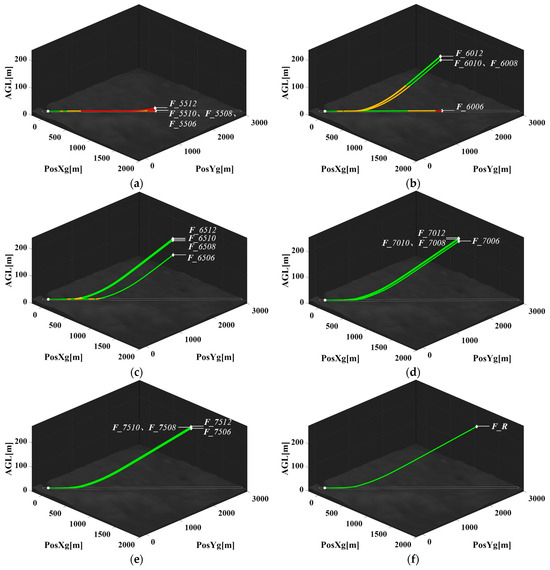

The overall safety status and safety coefficient of each scenario are shown in Figure 16. The colored blocks represent the overall safety status. The safety results of the flight path of the aircraft under different speeds and pitch angles are shown in Figure 17.

Figure 16.

Safety coefficients of test scenarios.

Figure 17.

Flight path safety status diagram of Cessna 550: (a) F_55xx series scenarios comparison chart; (b) F_60xx series scenarios comparison chart; (c) F_65xx series scenarios comparison chart; (d) F_70xx series scenarios comparison chart; (e) F_75xx series scenarios comparison chart; (f) F_R scenarios comparison chart.

It can be seen from Figure 16 and Figure 17 that when the aircraft’s climb speed is 55 m/s, due to the low flight speed, the aircraft is unable to obtain sufficient lift to complete the takeoff process. At the end of the simulation, the flight paths of F_5506, F_5508, and F_5510 are basically overlapping and all fail to takeoff. F_5512 has a lower takeoff height. In the entire simulation process of the four test conditions, the safety of the entire aircraft shows abnormal states. Throughout the simulation process, the safety of the entire aircraft of F_5506 is in the ‘Caution’ state, while the safety of F_5508, F_5510, and F_5512 is in the ‘Warning’ state.

When the aircraft’s climb speed is 60 m/s, due to the increase in flight speed, the problem of insufficient lift is significantly improved. F_6008, F_6010, and F_6012 all complete the takeoff process. F_6006 is unable to takeoff due to its low angle of attack, and the entire simulation process of the four test conditions shows abnormal states for the safety of the entire aircraft. The safety status of F_6006 is ‘Warning’, while F_6008, F_6010, and F_6012 are in the ‘Caution’ state during the initial climbing phase due to their high pitch angles and angles of attack. When the test aircraft begins to steadily climb, the safety status returned to normal.

When the aircraft’s climb speed is 65 m/s, it is able to complete the takeoff procedure under various rotation pitch angles. The flight paths of F_6508, F_6510, and F_6512 are basically coincident. F_6506, due to its lower rotation pitch angle, has insufficient lift and an increased takeoff run distance. During the aircraft rotation phase, all four test scenarios experience abnormal safety conditions due to excessive pitch angles. These conditions are classified as ‘Caution’ states. As the aircraft continues to climb, the safety conditions return to ‘Normal’, and establish a stable climb state.

When the aircraft’s climbing speed is 70 m/s, the four test scenarios’ flight paths are basically coincident. Each scenario’s aircraft is able to complete the takeoff procedure. The aircraft’s takeoff pitch altitude has a relatively minor impact on the aircraft’s trajectory. Only F_7006 has a slightly longer run distance due to a lower pitch angle. The three test scenarios of F_7006, F_7010, and F_7012 also experience a brief abnormal state during the aircraft’s takeoff phase, but their safety status returns to normal afterwards and establishes a stable climb. During the F_7008 test flight process, no abnormalities occur in the aircraft, and it completes the set takeoff and climb flight tasks in a normal state.

When the aircraft’s climb speed is 75 m/s or 80 m/s, the influence of the takeoff pitch altitude of the aircraft on the aircraft’s flight path can be basically ignored. In all test conditions, the aircraft exhibit no abnormality during the virtual flight process, and the aircraft complete the entire takeoff and climb process in a safe state.

From the above, the following conclusion can be drawn: For this aircraft to takeoff safely and during the initial climb, the aircraft’s climb speed should be above 75 m/s. When the airspeed is lower than this speed, the flight process will face certain risks. When the airspeed is lower than 60 m/s, there will inevitably be flight risk events such as takeoff failure and abnormal conditions. Attempting to increase takeoff pitch angle to achieve the aircraft’s takeoff operation will further deteriorate the aircraft’s safety status. In this condition, the airspeed should be immediately increased or the takeoff should be abandoned.

4. Conclusions

The present study establishes a virtual flight and safety awareness technology that closely reflects real flight scenarios, aiming to predict the dynamic characteristics and the safety status of aircraft under specific flight missions and environments. The main research conclusions are drawn as follows:

- The dynamic characteristics of the aircraft under various flight conditions are simulated using sets of small perturbation equations. According to different phases of the flight mission, corresponding flight control objectives and commands are generated. By incorporating relevant databases to simulate the effects of terrain, atmosphere, and weather conditions in the real flight environment, a virtual flight methodology oriented toward flight safety analysis and assessment is established.

- A safety awareness technique based on fuzzy safety constraints is proposed, further advancing multiple safety assessment methodologies, including parameter safety awareness, flight path safety awareness, and a series of related safety perception techniques. Safety state and safety coefficient algorithms are defined to transform the physical state of the aircraft during flight into a mathematical representation through visualization charts.

- The takeoff and climb scenario of the Cessna 550 aircraft is selected as a case study to analyze and evaluate the feasibility of the developed methodology. The results demonstrate that the safety status and the coefficient of the aircraft under each test flight condition can be successfully determined, and the safe operating envelop of the aircraft in specific scenarios is further obtained.

Author Contributions

Methodology, X.Z.; software, Z.G.; validation, H.Q.; investigation, X.Z. and Z.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.G.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, H.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number No. 51805440 and the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province, grant number No. SJCX25 0138 is also acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tepylo, N.; Straubinger, A. Exploring the intellectual insights in aviation safety research: A systematic literature and bibliometric review. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 178, 103873. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Zhang, J. Next frontiers of aviation safety: System-of-systems safety. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 160, 109247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancel, E.; Shih, A.T. Safety assessment and risk management for urban air mobility and advanced air mobility operations. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102094. [Google Scholar]

- Allouche, M.; Givigi, S. Multi-agent coordination and control for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in complex environments. J. Unmanned Veh. Syst. 2020, 8, 167–189. [Google Scholar]

- Clothier, R.A.; Williams, B.P. A review of the safety and regulatory challenges for eVTOL aircraft in urban air mobility. Aeronaut. J. 2019, 123, 1047–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Wang, L.; Tan, X. Digital virtual flight testing and evaluation method for flight characteristics airworthiness compliance of civil aircraft based on HQRM. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2015, 28, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ericsson, L.E. Sources of High Alpha Vortex Asymmetry at Zero Sideslip. J. Aircr. 1992, 29, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratliff, C.L.; Marquart, E.J. An assessment of a potential test technique: Virtual flight testing (VFT). In Proceedings of the 1995 Flight Simulation Technologies Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 7–10 August 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mhangami, W.; King, S.; Barry, D. Accepting Technology in Aviation Safety Risk Management: An extension of the technology acceptance model. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the PHM Society, Nashville, TN, USA, 9–10 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stolzer, A.J.; Halford, C.D.; Goglia, J.J. Safety Management Systems in Aviation, 1st ed.; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegmann, D.A.; Shappell, S.A. A Human Error Approach to Aviation Accident Analysis: The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System, 1st ed.; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nosrati Malekjahan, S.M.; Husseinzadeh Kashan, A.; Mojtaba Sajadi, S. A novel sequential risk assessment model for analyzing commercial aviation accidents: Soft computing perspective. Risk Anal. 2025, 45, 128–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, B.; Zhan, H. Calculation of dynamic derivatives for aircraft based on CFD technique. Acta Aerodyn. Sin. 2014, 32, 834–839. [Google Scholar]

- Green, L.L.; Spence, A.M.; Murphy, P. Computational Methods for Dynamic Stability and Control Derivatives. In Proceedings of the 42nd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, NV, USA, 5–8 January 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y. Research on Parameters Tuning of PID Controller Based on Critical Proportioning Method. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Electrical, Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Phuket, Thailand, 24–25 April 2016; Atlantis Press: Phuket, Thailand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Modern Aircraft Flight Dynamics and Control, 1st ed.; Shanghai Jiaotong University Press: Shanghai, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ivan, Y.B. The Intelligent Situation Awareness and Forecasting Environment (The S.A.F.E. Concept): A case study. In Proceedings of the Advances in Aviation Safety Conference and Exposition, Daytona Beach, FL, USA, 13–15 April 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ivan, Y.B. Prediction of aircraft safety performance in complex flight situations. In Proceedings of the SAE Advances in Aviation Safety Conference, 2003 Aerospace Congress and Exhibition, London, UK, 11–13 November 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Burdun, I.Y.; Parfentyev, O.M. Fuzzy situational tree-networks for intelligent flight support. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 1999, 12, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharl, J.; Mavris, D.; Burdun, I. Use of Flight Simulation in Early Design: Formulation and Application of the Virtual Testing and Evaluation Methodology. In Proceedings of the AIAA Modeling and Simulation Technologies Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 14–17 August 2000. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.