Abstract

Accurate estimation of aircraft operations, such as takeoffs and landings, is critical for airport planning and resource allocation, yet it remains particularly challenging at non-towered airports, where no dedicated surveillance infrastructure exists. Existing solutions, including video analytics, acoustic sensors, and transponder-based systems, are often costly, incomplete, or unreliable in environments with mixed traffic and inconsistent radio usage, highlighting the need for a scalable, infrastructure-free alternative. To address this gap, this study proposes a novel dual-pipeline machine learning framework that classifies pilot radio communications using both textual and spectral features to infer operational intent. A total of 2489 annotated pilot transmissions collected from a U.S. non-towered airport were processed through automatic speech recognition (ASR) and Mel-spectrogram extraction. We benchmarked multiple traditional classifiers and deep learning models, including ensemble methods, long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), across both feature pipelines. Results show that spectral features paired with deep architectures consistently achieved the highest performance, with F1-scores exceeding 91% despite substantial background noise, overlapping transmissions, and speaker variability These findings indicate that operational intent can be inferred reliably from existing communication audio alone, offering a practical, low-cost path toward scalable aircraft operations monitoring and supporting emerging virtual tower and automated air traffic surveillance applications.

1. Introduction

Accurate monitoring of aircraft operations is essential to the strategic functioning of airports, yet it remains challenging—especially for non-towered facilities. Daily and annual counts of takeoffs and landings are critical for both towered and non-towered airports, supporting a wide range of airport management tasks, including strategic planning, environmental assessments, capital improvement programs, funding justification, and personnel allocation. Insights derived from operational counts can substantially inform decisions related to airport expansions, infrastructure upgrades, and policy formulation. In the United States, only 521 of the 5165 public-use airports are staffed with air traffic control personnel capable of tracking aircraft movements, underscoring a considerable gap in operational data coverage [1].

At towered airports, operational aircraft counts are typically recorded by air traffic control (ATC) towers, though these data often lack details and completeness. Many control towers operate on a part-time basis, leading to missed aircraft activity and resulting in incomplete operational records. In response to these limitations, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), in collaboration with the aviation industry, has undertaken various initiatives in recent years to improve the estimation of aircraft operations. A wide array of methods has been employed at both towered and non-towered airports, leveraging technologies such as acoustic sensors, airport visitor logs, fuel sales data, video image detection systems, aircraft transponders, and statistical modeling techniques [2,3,4,5]. Despite these efforts, existing technologies remain constrained by high costs, limited adaptability, and inconsistent accuracy, failing to provide a universally applicable, economical solution for all airport types. This challenge is particularly acute for the nation’s general aviation airports, which collectively service over 214,000 aircraft and account for more than 28 million flight hours annually across more than 5100 U.S. public airports [6]. The absence of a reliable, scalable, and cost-effective approach to accurately monitoring aircraft operations underscores the urgent need for innovative solutions. Addressing this data gap is essential to enhancing decision-making in airport planning, infrastructure development, and policy formulation.

From a machine learning standpoint, pilot communication audio offers a valuable yet underutilized data source. Unlike physical sensors, these recordings are already widespread at airports and contain rich operational information. However, challenges such as unstructured language, overlapping speech, background noise, and limited labeled data make modeling and large-scale supervised learning difficult.

Although prior studies have applied machine learning to aviation audio, most existing approaches rely on a single modality, either linguistic features derived from automatic speech recognition (ASR) or acoustic features extracted directly from the signal [7,8,9]. ASR-based systems have demonstrated utility for communication error detection and safety monitoring. Still, their effectiveness is limited by transcription errors caused by noise, overlapping transmissions, or low-quality transmissions, which are common in general aviation environments. Conversely, acoustic-only methods, including deep learning models trained on spectrograms or raw waveforms, capture necessary time–frequency patterns but lack access to semantic cues such as pilot-stated intentions or position reports [10,11]. As a result, these single-pipeline systems typically struggle to generalize to the inherent variability in non-towered airport communications. To address these shortcomings, this study introduces a dual-pipeline framework that integrates textual (ASR–TF-IDF) and spectral (Mel-spectrogram) representations, enabling systematic comparison and improved robustness over prior audio-based ATC approaches. By evaluating both modalities on a manually annotated dataset of real-world pilot communications, this work provides a comprehensive assessment of operational-intent classification using a dual-modality design explicitly tailored to non-towered airport environments.

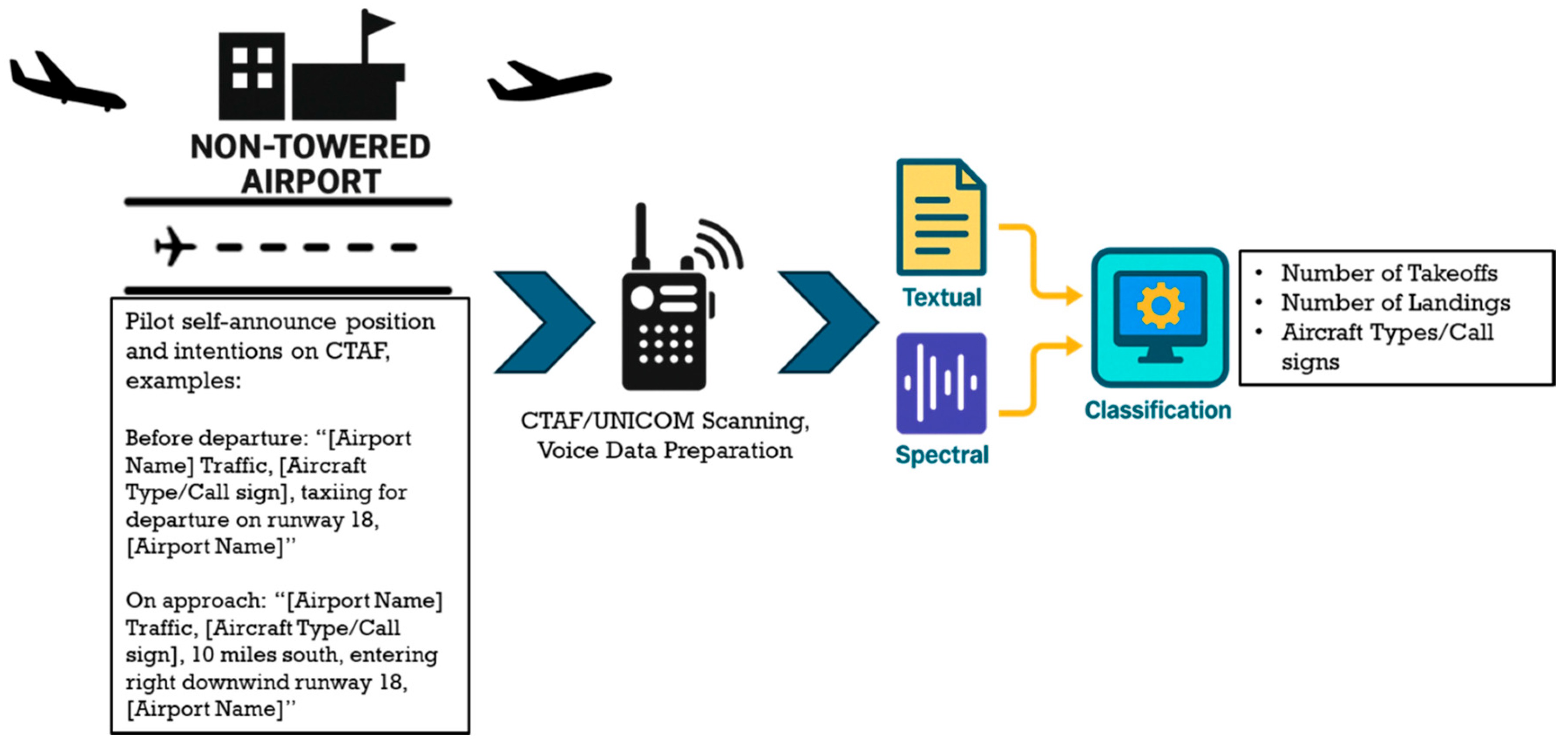

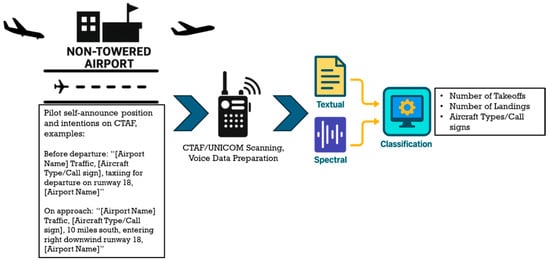

To address the broader challenge faced by many non-towered airports across the United States, we developed a practical, versatile approach based on standard operating procedures for air traffic communication at non-towered airports [12], as illustrated in Figure 1. The core component of this solution is a classification framework that leverages both textual and spectral features extracted from air traffic communication. The textual pipeline applies ASR followed by TF-IDF vectorization, while the spectral pipeline extracts Mel-spectrograms to capture acoustic patterns. These features are used to train a range of models, including traditional classifiers, LSTMs, and CNNs. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first dual-pipeline ML system trained on real-world pilot audio for operational intent recognition at non-towered airports.

Figure 1.

The overview of the solution architecture.

Our contributions include (1) a dual-modality machine learning framework that overcomes speech irregularity and background noise challenges by leveraging both textual and spectral representations of real-world pilot radio communications; (2) a structured data collection and augmentation framework that addresses the scarcity of labeled air traffic audio and enables robust model training under realistic conditions; and (3) the first versatile application of this approach to infer operational intent (landing vs. takeoff) from air traffic communication at non-towered airports. As pilot communication audio is already widely available, our framework requires no additional hardware. It can be deployed at scale, making it a cost-effective and practical solution for all types of airports.

2. Related Work and Challenges

This section reviews prior work on aviation audio analysis and machine learning-based audio classification, covering data acquisition, preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification methods. It also highlights recent advances and limitations in deep learning that motivate the dual-pipeline framework proposed in this study. Although a wide range of sensing and data-driven techniques have been explored for estimating aircraft operations or interpreting communications, existing approaches face constraints that limit their applicability at non-towered airports.

2.1. Aircraft Operation Estimation Approaches

A variety of methods have been developed to estimate aircraft operations, particularly at airports without full-time ATC towers. Among these, aircraft transponder signal analysis techniques have been extensively explored [13,14,15]. Transponder-based methods exploit Mode S Extended Squitter (ES), Mode S, and Mode C signals, typically captured using software-defined radio (SDR) systems to infer aircraft proximity and movement. Adaptive Kalman filters are often employed to improve the accuracy of distance estimation. Transponder-based approaches offer the advantage of estimating operational counts without the extensive need for additional ground-based infrastructure. However, their applicability is limited to cooperative traffic, as they rely on aircraft being equipped with transponders. Furthermore, reported error rates vary across deployment conditions, ranging from −10.2% to +7.6% [5]. At non-towered rural airports, where the majority of movements are conducted by light aircraft that may not carry transponders, these methods are likely to substantially undercount operations, further diminishing their suitability as a universal solution.

Other techniques, such as flight tracking, acoustic sensing, and video-based surveillance, have also been investigated for estimating aircraft operations [16]. For instance, Patrikar et al. introduced the Tartan Aviation multi-modal dataset, designed to support airspace management in both towered and non-towered terminal areas [17]. High-resolution flight tracking data, when combined with ground-based acoustic sensors, has enabled the reconstruction of low-altitude flight paths and operational counts with varying degrees of fidelity. Despite their potential, these approaches face persistent challenges, including susceptibility to environmental noise interference, incomplete or uneven signal coverage, and difficulties in validating data reliability across diverse airport settings. Acoustic-based systems, in particular, often struggle with precise aircraft identification, especially in mixed traffic environments, and tend to lack the resolution necessary to support fine-grained operational assessments. Video-based surveillance, particularly when coupled with computer vision techniques, has recently emerged as another promising avenue. These systems have demonstrated the potential to deliver accurate operational counts and to classify aircraft type [18]. However, their utility is significantly constrained by the inherent limitations of optical sensing. Video surveillance systems often have a limited field of view, requiring multiple cameras across the airfield to achieve comprehensive coverage. Moreover, their performance is susceptible to external conditions, with factors such as lighting, weather, and visibility directly affecting detection accuracy and reliability. The associated costs of installation, calibration, and ongoing maintenance further reduce the practicality of video-based methods, particularly for small non-towered airports. Air traffic communication audio collected through the General Audio Recording Device (GARD) has also been utilized to estimate operational counts by averaging the number of radio transmissions. While straightforward, this approach lacks precision and is highly sensitive to variability in communication patterns. In particular, its effectiveness is further reduced at airports that share the same Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF), where overlapping or extraneous transmissions can distort estimates and lead to substantial inaccuracies [19].

Manual and semi-automated approaches remain common practice at many non-towered airports, where technological alternatives may be prohibitively costly or impractical to implement. These methods typically rely on indirect indicators such as fuel sales records, visitor logs, and other administrative or operational data. While straightforward and relatively low-cost, these methods are inherently labor-intensive, frequently inconsistent, and limited in accuracy.

A review of related work highlights a clear progression from early manual counting techniques toward increasingly sophisticated technological solutions, including transponder-based monitoring and, more recently, machine-learning-enabled classification systems. However, despite this evolution, a universally applicable, cost-effective, and scalable approach remains elusive. Each method carries inherent trade-offs, whether related to infrastructure requirements, reliance on cooperative traffic, or sensitivity to local operational environments. The diversity of airport contexts—from busy, towered hubs to small, rural, non-towered fields—further underscores the need for adaptable, resilient solutions. Consequently, there is a pressing need for innovative systems that can deliver accurate, low-cost estimates of aircraft operations across all airport types, thereby enabling more effective resource allocation, strategic planning, and policy development in the aviation domain.

2.2. Machine Learning for Aviation Audio Analysis

Audio classification plays a critical role in aviation environments, underpinning a wide range of operational and safety-related applications, including monitoring cockpit communications, detecting anomalies in ATC transmissions, and enhancing situational awareness in airport operations. Unlike general-purpose audio tasks, aviation audio presents a particularly challenging domain. Recordings frequently contain overlapping speech between multiple speakers, elevated levels of ambient and engine noise, and a high density of domain-specific terminology and phraseology unique to aviation communications. These characteristics complicate both acoustic and linguistic analysis, necessitating robust preprocessing pipelines, advanced noise-reduction strategies, and domain-adaptive modeling to achieve reliable performance.

Recent research has increasingly explored the use of advanced machine learning and natural language processing (NLP) techniques to address a range of operational and safety challenges within the aviation domain [20,21,22]. For instance, Chen et al. introduced the Audio Scanning Network (ASNet), a framework that leverages rich acoustic feature representations to achieve stable, accurate classification across diverse audio environments [11]. Similarly, Castro-Ospina et al. explored a graph-based approach to audio classification, demonstrating its potential for structured analysis of complex acoustic data [10]. Among these efforts, automatic speech recognition (ASR) has emerged as one of the most extensively explored and studied areas, with a wide range of machine learning architectures applied to pilot-controller communications for downstream applications such as intent recognition, safety monitoring, and traffic flow analysis [7,8,9,23].

Prior aviation communication studies broadly fall into two single-modality camps: text-first pipelines that depend on ASR transcripts, and audio-first pipelines that learn directly from spectral representations. Text-first approaches are inherently dependent on transcription quality; errors induced by channel noise, overlapping transmissions, and clipped phraseology can corrupt the downstream intent signal and reduce overall reliability in general aviation environments. Conversely, audio-first models are typically robust to radio-channel artifacts. Still, they operate with limited access to the explicit semantic intent expressed in standardized phraseology (e.g., “departing,” “final,” “touch-and-go”), which can be decisive when acoustic patterns are ambiguous or when background noise masks key cues. More importantly, existing work rarely integrates textual and spectral modalities effectively because they are challenging to align and are not equally trusted in real-world ATC audio. First, ASR output is often noisy and non-deterministic (domain terms, tail numbers, and partial transmissions), resulting in text features with variable reliability and unclear confidence scores. Second, the textual and spectral streams are not naturally synchronized at the decision-relevant granularity: short utterances, interruptions, and overlapping calls create segmentation mismatches, so naïve fusion can amplify noise rather than add complementary evidence. Third, limited labeled aviation corpora make multimodal fusion prone to overfitting to dataset-specific quirks (speaker mix, channel conditions), especially when the model must learn both alignment and classification simultaneously. These constraints motivate a dual-pipeline design that explicitly evaluates both modalities under the same conditions and clarifies when each modality succeeds or fails.

Despite growing interest in ML for aviation audio, prior approaches either (i) rely on ASR-derived text that degrades under radio-channel noise and overlapping speech [7,8,9], or (ii) rely on spectral features that omit explicit semantic intent cues [10,11]. Because transcript reliability and cross-modal alignment are highly variable in non-towered airport recordings, end-to-end or naïvely fused multimodal approaches struggle to exploit complementary information across textual and acoustic streams consistently. As a result, existing studies have not demonstrated a reliable and systematic integration of textual semantics and spectral acoustics for operational-intent recognition. This gap motivates our dual-pipeline framework, which isolates and benchmarks both modalities on the same real-world dataset to expose their respective failure modes and robust characteristics.

3. Materials and Methods

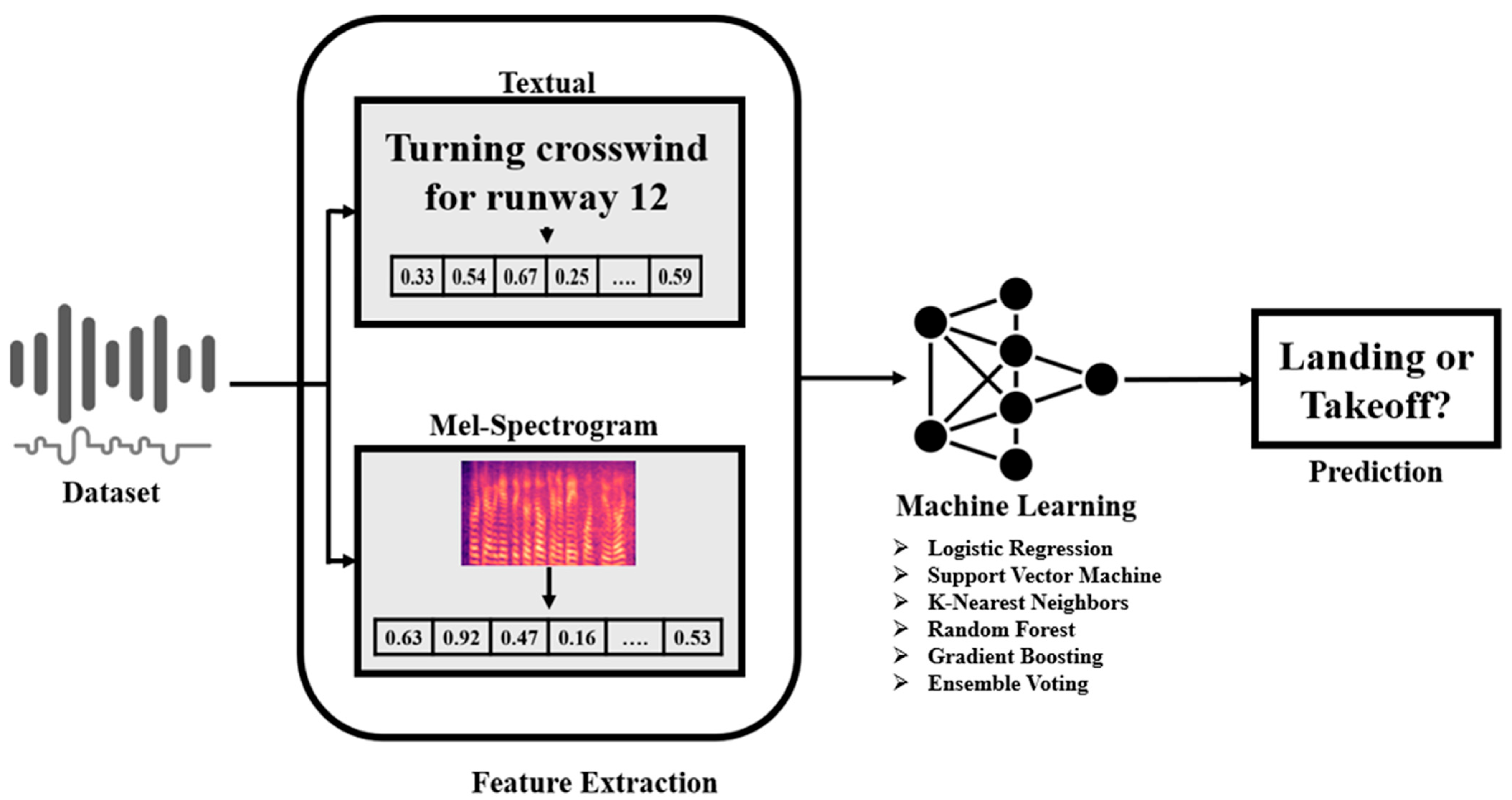

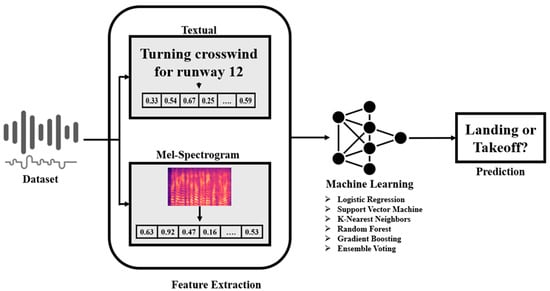

This study focused on the core component of the proposed solution: the development of machine learning-based methods for audio classification. To this end, we adopt two complementary approaches: the Textual approach, which transcribes audio using ASR for text-based classification, and the Spectral approach, which directly extracts Mel-spectrograms from audio signals. To comprehensively evaluate these approaches, we apply both traditional machine learning algorithms and modern deep learning models. The subsequent sections outline the dataset, preprocessing methods, model configurations, and evaluation criteria used in this study. An overview of the proposed dual-pipeline framework is shown in Figure 2. During inference, the textual and spectral pipelines operate independently, generating separate predictions without ensembling. This design enables a direct comparison of the two approaches, facilitating a clearer understanding of the individual contributions and limitations of textual versus spectral features in the classification of pilot radio communications.

Figure 2.

Overview of the dual-pipeline architecture integrating textual (ASR-TF-IDF) and spectral (Mel-spectrogram-CNN) feature extraction for intent classification at non-towered airports.

Before model training, pilot communication is processed by two parallel feature-extraction pipelines. In the textual pipeline, raw audio recordings are first denoised using spectral subtraction and then transcribed into text using an automatic speech recognition (ASR) system. The resulting transcripts are converted into numerical representations using term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF), producing sparse feature vectors that capture aviation-specific phraseology and intent-related keywords. In parallel, the spectral pipeline operates directly on the audio signal, extracting Mel-spectrogram representations that preserve the time-frequency characteristics of speech, including prosodic cues, transmission artifacts, and background noise. These Mel-spectrograms are normalized and formatted as two-dimensional inputs for a convolutional neural network (CNN).

3.1. Data Collection and Processing

To support machine learning-based classification of aircraft operational intent, we construct a domain-specific dataset from pilot radio communications recorded at a public, non-towered airport (KMLE) in Nebraska, United States. This airport primarily serves general aviation activities and represents the operational characteristics of most non-towered airports in the U.S. These recordings were collected over three months using both the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF) and the Universal Communications Frequency (UNICOM), yielding more than 68 h of raw audio. All recordings used in this study were obtained from publicly accessible VHF aviation frequencies, which are openly monitored by pilots, airports, and aviation enthusiasts and are not encrypted or restricted under FAA policy. Only operational information that is already publicly broadcast—such as aircraft callsigns and standard traffic advisories—was captured. No additional personally identifiable information was collected, and audio files were stored and processed in accordance with institutional data-use guidelines. Thus, all data collection activities were fully aligned with FAA regulations on public air-ground communication and with institutional requirements for responsible research data management.

The raw audio data were segmented into 2489 distinct utterances, defined by clear pauses and transmission boundaries. These utterances represent a wide range of real-world communication variability, including overlapping transmissions, fluctuations in audio quality, and diverse speaker accents. The dataset also reflects the highly specialized nature of aviation phraseology, which is often compact, elliptical, and non-grammatical, optimized for rapid information exchange in operational settings.

To enable supervised learning, each audio clip was manually annotated by three licensed pilots with extensive experience in radio communication. The annotations process included three categories: (1) Operational Intent: “Landing” or “Takeoff”; (2) Aircraft Position: “downwind,” “base leg,” and “final”; (3) Callsign: the aircraft’s tail number. Annotation disagreements were resolved by majority voting, and clips that remained ambiguous were excluded from the final dataset. Representative examples for each label are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Example data for landing and takeoff labels.

This annotated dataset is a rare, carefully structured resource for training machine learning models to infer operational intent from unstructured aviation audio. It is specifically designed to support both textual and spectral feature extraction pipelines, thereby enabling dual-modality learning under challenging acoustic conditions.

3.1.1. Textual Feature Extraction with Spectral Subtraction

Audio transcripts in the textual pipeline were generated using the Google Web Speech API accessed via the SpeechRecognition Python library 3.14.4 (Chirp 3: Transcription on Speech-to-Text V2 API), using the default recognizer configuration and English language settings. Because this ASR service is cloud-hosted and updated server-side, the provider does not expose a fixed model version identifier. To support reproducibility, we report the transcription time window (July 2025) and document the exact software interface used (library, version, and recognition call). We additionally verified that the same workflow remains functional under the documented configuration at the time of revision. Readers seeking strict version control may substitute an offline/open-source ASR engine (e.g., Whisper/Vosk) following the same preprocessing steps, although such comparisons are outside the scope of this study.

Let denote the time-domain audio signal. To reduce background noise, we apply a spectral subtraction technique. The signal is first converted to the frequency domain using the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT):

The noise power spectral density (PSD) is estimated from the first T frames of the signal, , assuming they contain only background noise:

Denoising is then performed via spectral subtraction:

To preserve speech quality, a temporal smoothing filter is applied across frames. The enhanced signal is reconstructed using the inverse STFT (ISTFT) and the original phase :

The cleaned signal is transcribed into text using the Google Web Speech API [24], resulting in a sequence of words . These transcriptions are transformed into structured features using the Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) vectorization method. The TF-IDF value for a term t in document d is computed as

where is the term frequency of term t in document is the number of documents containing t, and N is the total number of documents.

This process yields a sparse feature vector , where m is the size of the vocabulary. These numerical features are then used as input to machine learning models for classification. TF-IDF was selected for its ability to emphasize informative, aviation-specific terminology while down-weighting common words, making it ideal for sparse, domain-specific text data.

3.1.2. Spectral Feature Extraction with Mel-Spectrograms

For the direct audio-based classification pipeline, we extracted Mel-spectrogram representations from each audio recording and used them as model input. Each audio file was first resampled to a standard sampling rate of 22,050 Hz and truncated or zero-padded to a fixed duration of 3 s to ensure consistency.

Let denote the time-domain signal. We applied a 2048-point Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) with a hop length of 512 to compute the short-time magnitude spectrum. The signal was then mapped onto the Mel scale using a filter bank of M = 128 triangular filters, resulting in the Mel-spectrogram:

where is the FFT of the -th frame at frequency bin , and is the Mel filter bank. The resulting spectrogram was converted to the decibel (dB) scale:

where is a small constant added for numerical stability. The spectrograms were then min-max normalized to the range [0,1] and reshaped to a fixed size of 128 × 130 time-frequency bins.

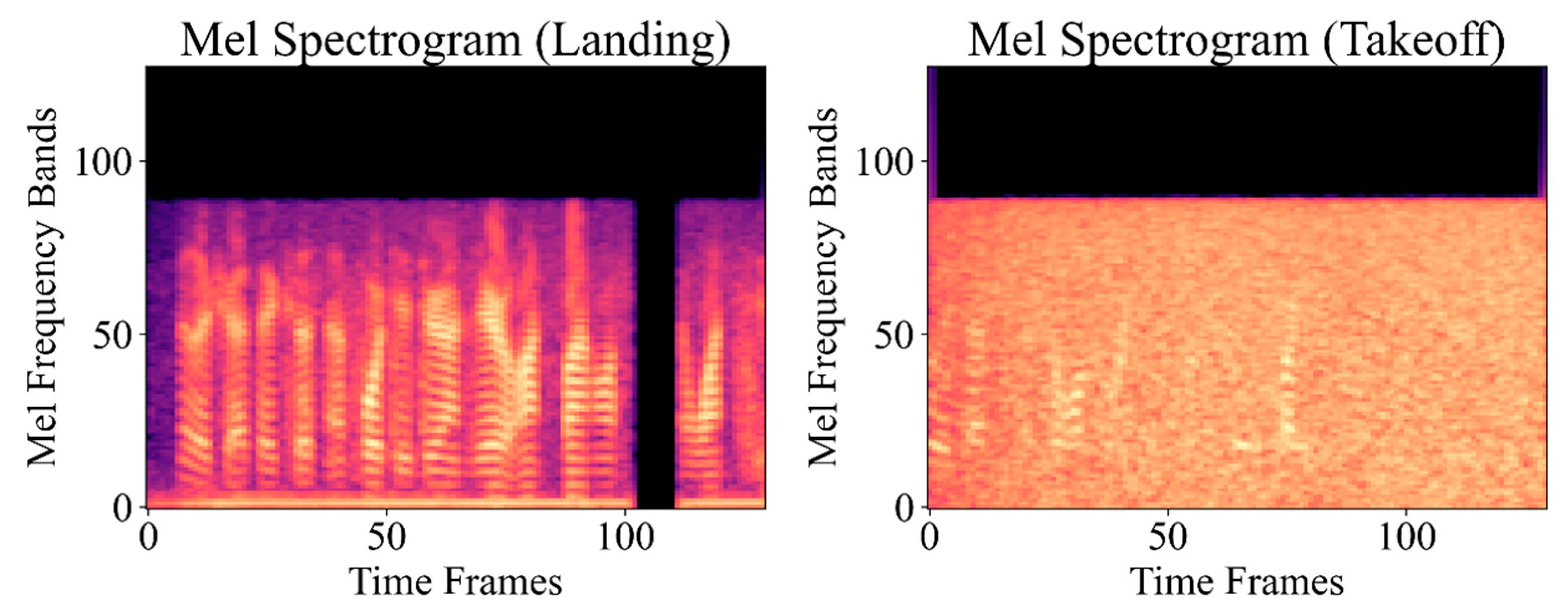

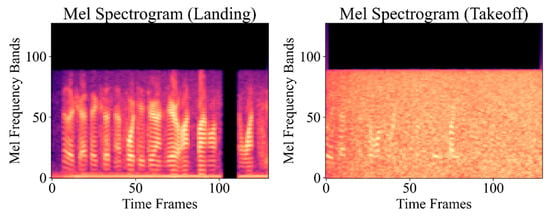

To maintain uniform input shape compatible with convolutional neural networks, shorter recordings were zero-padded along the time axis, and longer ones were truncated. Illustrations of Mel-spectrograms for both the “Landing” and “Takeoff” classes are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Examples of Mel-spectrograms for both classes.

Following feature extraction, valid spectrograms were collected into a NumPy array with an additional channel dimension, resulting in a dataset of shape (N, 128, 130, 1), where N is the number of audio samples. This ensured compatibility with 2D convolutional neural network architectures for subsequent classification tasks.

3.1.3. Audio Data Augmentation

To improve model robustness and generalization, we applied audio augmentation techniques during training to simulate real-world variations in pilot speech and acoustic conditions. Specifically, we used three methods: time stretching (10% speed increase without pitch change) to mimic varying speech rates, Gaussian noise injection (noise factor 0.005) to replicate ambient sounds like wind or static, and temporal shifting (up to 10% of employed three methods: time stretching (a 10% speed increase without pitch change) to simulate varying speech rates, Gaussian noise injection (with a noise factor of 0.005) to replicate ambient sounds such as wind or static, and temporal shifting (up to 10% of the duration) to account for speech timing differences. These augmentations preserved the audio’s semantic content and were applied only during training, with test data left unchanged to ensure fair evaluation.

3.1.4. Classification Models and Training Procedure

A balance between representational capability, data efficiency, and practical deployability guided the selection of deep learning architectures in this study. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) were chosen for the spectral pipeline because they are well-suited for learning localized time–frequency patterns in Mel-spectrograms and have been widely shown to perform robustly in noisy audio classification tasks with moderate dataset sizes [18,25]. CNNs also offer lower computational complexity compared to more elaborate hybrid architectures, making them attractive for continuous monitoring applications.

For the textual pipeline, long short-term memory (LSTM) networks were selected due to their effectiveness in modeling sequential dependencies in short, structured utterances produced by automatic speech recognition systems, particularly when training data are limited, and transcripts are imperfect [7,8]. While more complex architectures such as convolutional recurrent neural networks (CRNNs) or Transformer-based models have shown strong performance in speech and language tasks, their benefits typically emerge when large-scale annotated datasets and high-fidelity transcripts are available [7,8,9]. Given the constrained size of labeled aviation audio data and the presence of transcription noise in real-world radio communications, the chosen CNN and LSTM architectures provide a practical and well-justified trade-off between performance, robustness, and scalability.

To evaluate the Textual and Spectral pipelines, we implemented a diverse set of models , including both traditional classifiers—Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, K-Nearest Neighbors, and Gradient Boosting—and deep learning architectures (CNN and LSTM). These models were trained and tested on consistent data splits across both pipelines. CNNs were applied to 2D Mel-spectrograms, while LSTMs processed ASR-transcribed text sequences. Additionally, we incorporated an ensemble model using soft voting, where the final prediction is given by

Here, denotes the probability assigned to the class by model . All hyperparameters were tuned via grid search or manual optimization, enabling consistent benchmarking across architectures.

As shown in Algorithm 1, let denote an input ATC audio segment. is the corresponding intent label. denotes the dataset. The textual pipeline uses an automatic speech recognition (ASR) model to generate a transcript , which is then mapped to a textual feature embedding using a text encoder . The spectral pipeline extracts acoustic features (e.g., Mel or log-Mel spectrograms), which are encoded into spectral embeddings via a spectral encoder . Classifiers and produce intent predictions from textual and spectral embeddings, respectively. During training, both pipelines are optimized independently using labeled data; during inference, each pipeline produces an intent prediction for evaluation and comparison.

| Algorithm 1 Audio Classification via Textual and Spectral Feature Pipelines |

| Require: Audio dataset {Landing, Takeoff} |

| Ensure: 1: do |

2: Preprocess audio:

|

3: Extract features:

|

| 4: end for |

| 5: |

| 6: using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score |

4. Results

This section presents a detailed evaluation of the proposed audio classification framework, comparing the Textual and Spectral pipelines using various machine learning and deep learning models. We split our dataset into 60% for training, 20% for validation, and 20% for testing, and trained deep models with the Adam optimizer (learning rate 0.001) and Binary Crossentropy loss.

The results are organized as follows: Section 4.1 details model-wise performance for each pipeline; Section 4.2 presents robustness results via augmentation; Section 4.3 analyzes feature extraction techniques; and Section 4.4 discusses metric correlations.

4.1. Model Performance Across Pipelines

To evaluate model performance across different learning paradigms, we benchmarked six traditional classifiers and two deep learning models on both the textual (TF-IDF) and spectral (Mel-spectrogram) pipelines. Table 2 presents the results for all models across six metrics. Overall, models using spectral features consistently outperform their textual counterparts. Among traditional classifiers, Gradient Boosting and Random Forest achieved strong and balanced results across all metrics, especially in the spectral pipeline. The CNN model outperformed all others, achieving the highest AUROC (0.95) and AUPR (0.94), which highlights the effectiveness of deep learning with time-frequency features for audio classification.

Table 2.

Performance of traditional and deep learning models across textual and spectral pipelines.

Table 3 compares the classification accuracies of textual-only, spectral-only, and decision-level-fused models. Across all traditional classifiers, the spectral pipeline consistently outperforms the textual pipeline, reflecting the robustness of acoustic representations in noisy airport communication environments. Decision-level fusion yields mixed results: modest improvements are observed for some models (e.g., SVM and KNN), while for others, fusion performs similarly to or slightly worse than the spectral-only baseline (e.g., Random Forest and Gradient Boosting). Notably, the CNN-based spectral model achieves the highest accuracy (0.93) without fusion, indicating that spectral features alone capture the dominant discriminative cues. These results suggest that while fusion can be beneficial in some instances, its effectiveness is limited by noise in ASR-derived textual features, and the spectral modality remains the most reliable source of information in this setting.

Table 3.

Accuracy comparison with the fusion model.

4.2. Feature Representation Comparison

To evaluate the impact of different feature representations, we conducted an ablation study comparing TF-IDF and BERT embeddings for textual inputs, as well as Mel-spectrograms versus Log-Mel spectrograms for spectral inputs. The results, summarized in Table 4, indicate that TF-IDF consistently outperformed BERT across most traditional machine learning classifiers. In contrast, BERT embeddings showed a slight advantage when used with the LSTM model, reflecting their ability to capture sequential dependencies.

Table 4.

Accuracy with different feature representations.

In the spectral pipeline, Log-Mel features yielded modest improvements for Gradient Boosting and Ensemble models. At the same time, standard Mel-spectrograms remained more effective when combined with CNN architecture, which appears to exploit their raw frequency-time structure. Overall, these findings suggest that the effectiveness of a given feature representation is closely linked to the choice of model architecture and the characteristics of the input modality. Consequently, careful alignment between representation type and classifier design is essential to maximize performance in aviation audio classification tasks.

4.3. Robustness Through Data Augmentation

To evaluate model robustness and generalization, we applied audio data augmentation during training for all models, both traditional machine learning and deep learning, across the Textual and Spectral pipelines. These augmentations simulate realistic variations in pilot speech and environmental noise, enabling models to better generalize to unseen data.

The augmentation techniques included time stretching (factor = 1.1), additive Gaussian noise (noise factor = 0.005), and temporal shifting (up to 10% of audio duration). All augmentations were applied exclusively during training. Test data remained unmodified to ensure fair evaluation. Using the raw audio waveforms, the applied Gaussian noise corresponds to an average SNR of 22.3 ± 6.7 dB, consistent with realistic airport communication conditions. As summarized in Table 5, augmentation generally improves classification accuracy across both textual and spectral pipelines, particularly for SVM, Gradient Boosting, and CNN-based models, indicating enhanced robustness to acoustic variability. While minor performance decreases are observed for a few traditional classifiers (e.g., Random Forest), the overall trend indicates improved generalization rather than redundancy. These results confirm that augmentation contributes meaningfully to robustness under realistic noise conditions rather than serving as a cosmetic addition.

Table 5.

Robustness comparison between before and after augmentation.

These results demonstrate that augmentation significantly improves model performance across both feature modalities and model types. Spectral models, particularly CNNs, benefited the most, but consistent gains were also observed in textual models, underscoring the value of training on varied, noisy inputs.

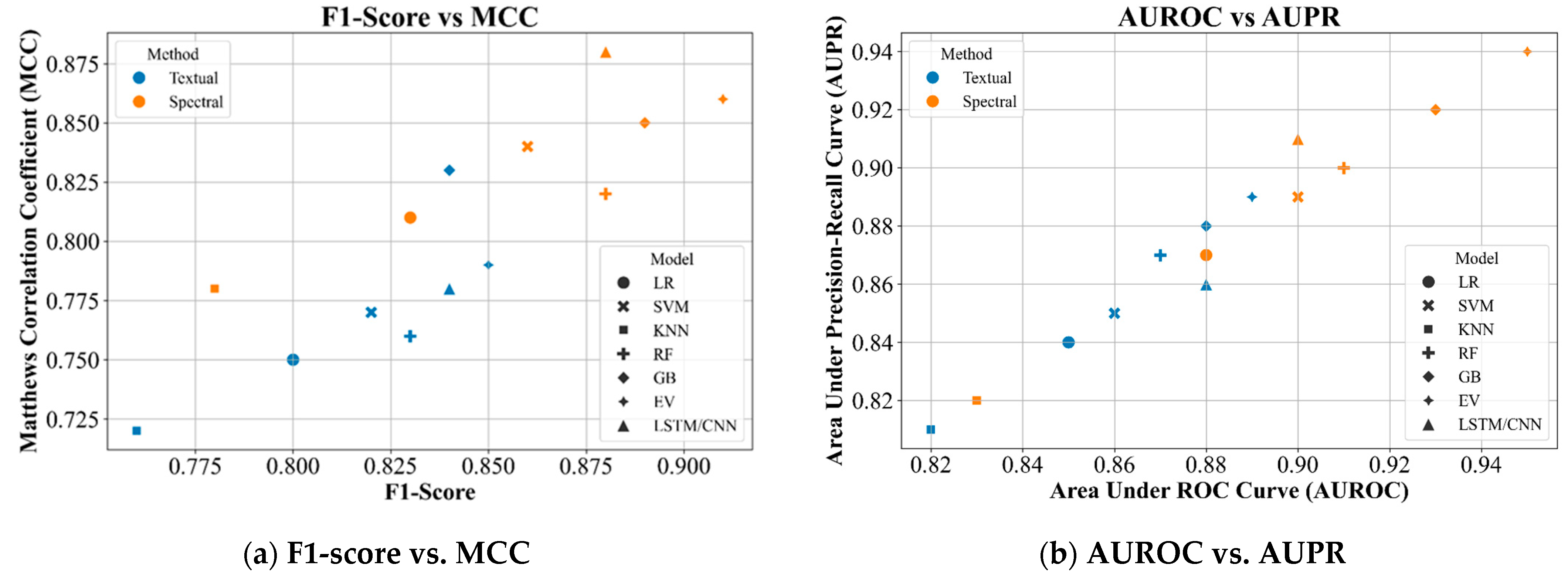

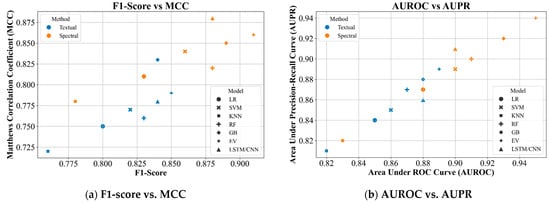

4.4. Evaluation of Metric Correlation Analysis

To better understand model performance, we examine the correlation between key evaluation metrics across all configurations, as shown in Figure 4. The F1-Score vs. MCC plot reveals a strong positive relationship, with Spectral models, especially CNNs, clustered in the upper-right, indicating consistent and balanced predictions. Similarly, the AUROC vs. AUPR plot shows that models with high AUROC also achieve strong precision-recall performance. These trends highlight the robustness and generalizability of models trained on Mel-spectrogram features.

Figure 4.

Metric correlation plots for all models across both pipelines. (a) F1-score versus MCC indicates that spectral models, particularly CNNs, yield balanced precision and recall; (b) AUROC versus AUPR confirms consistent ranking performance across class distributions.

5. Discussion

The proposed dual-pipeline framework demonstrates that combining textual and spectral representations of pilot radio communications can yield robust operational-intent classification at non-towered airports. Spectral models, particularly convolutional neural networks trained on Mel-spectrogram inputs, consistently outperformed text-based pipelines under the experimental conditions reported here. Data augmentation improved resilience to realistic acoustic perturbations and speaker variability, suggesting that practical deployment may be feasible using existing radio-monitoring infrastructure.

From a broader methodological perspective, this work’s contribution lies in clarifying the practical trade-offs among competing approaches to aviation communication intent recognition. Recent studies have explored Transformer-based ASR pipelines followed by text-centric intent classification, as well as graph-based or advanced acoustic modeling techniques for structured audio analysis [7,8,9,10,11]. While these approaches demonstrate strong potential, they often assume access to large, high-quality annotated datasets and reliable transcriptions, and their performance can degrade in the presence of overlapping transmissions, radio interference, and non-standard phraseology that are common in real-world non-towered airport environments [17,22]. In contrast, the results presented here show that a comparatively simple convolutional neural network trained on Mel-spectrogram representations achieves robust and consistent performance without reliance on high-fidelity transcripts or computationally intensive model architectures. This positions the proposed dual-pipeline framework as a scalable and deployment-oriented solution that aligns with the operational constraints of non-towered airports, where cost, infrastructure limitations, and robustness to noise are primary considerations [5,14]. Rather than replacing more complex end-to-end models, the proposed approach complements existing research by demonstrating that reliable operational intent classification can be achieved through data-efficient spectral representations under realistic operating conditions, with horizontal benchmarking against additional architectures identified as a priority for future multi-airport studies.

The performance gap between spectral and textual representations can be explained by the fundamental characteristics of aviation radio communications and has been observed in prior studies. ASR-based textual pipelines are known to be sensitive to transcription errors arising from overlapping transmissions, radio-frequency interference, accent variability, and the use of abbreviated or non-grammatical phraseology, all of which are prevalent in non-towered airport environments [7,8,9]. Errors introduced at the transcription stage propagate directly into downstream intent classification, limiting the effectiveness of purely text-based models. In contrast, spectral representations such as Mel-spectrograms preserve low-level acoustic information, including speech energy distribution, temporal dynamics, and channel artifacts, that remain informative even when linguistic content is partially degraded [18,19]. Similar advantages of spectral modeling under noisy operational conditions have been reported in aviation audio datasets and acoustic monitoring studies, where robustness to environmental noise and speaker variability was identified as a key determinant of classification reliability [12,17]. The results of this study, therefore, align with and extend existing findings by demonstrating that, for real-world non-towered airport communications, spectral features coupled with convolutional architectures capture the dominant discriminative cues more consistently than ASR-derived textual representations.

5.1. Limitations

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged.

- The empirical evaluation is based on a single non-towered airport (KMLE), which constrains the direct evidence for cross-site generalizability. Official operational statistics for many non-towered fields are themselves estimates and are not always suitable as ground truth, complicating external validation.

- The textual pipeline depends on ASR transcription quality; ASR errors can degrade downstream classification performance, particularly for overlapping transmissions or non-standard phraseology.

- While augmentation proved beneficial in this dataset, it cannot fully substitute for diverse real-world recordings from multiple airports and varying environmental conditions. We intentionally limited the scope of new data collection for this study; however, these limitations motivate the avenues discussed below.

- Although the present study evaluates the proposed framework using data collected from a single non-towered airport (KMLE), several features of the task and model design support its potential for cross-scenario generalization. First, pilot communication procedures at non-towered airports are governed by nationally standardized FAA phraseology and reporting conventions, meaning that many linguistic cues relevant to intent classification (e.g., position reports, runway identifiers, maneuver intentions) remain consistent across airports. Second, VHF radio characteristics—such as channel noise, compression artifacts, and intermittent interference—are broadly similar nationwide, enabling spectral models to learn noise-invariant patterns that are not site-specific. Third, the dual-pipeline architecture explicitly captures complementary semantic and acoustic information, allowing the system to remain robust even when ASR performance varies across accents or background noise conditions.

To further mitigate domain shift, the training process incorporates targeted data augmentation (time stretching, Gaussian noise, and temporal shifting) designed to simulate variability in speech rate, transmission quality, and environmental noise, mirroring conditions encountered at other airports. While these strategies enhance robustness, we acknowledge that full validation across diverse airport environments requires additional multi-site datasets. This study, therefore, provides a foundational demonstration of feasibility rather than a definitive assessment of nationwide deployment performance. Future work will involve collecting and evaluating data from multiple non-towered airports to systematically characterize cross-scenario generalization and refine the framework for operational use.

5.2. Generalization, Scalability, and Future Data Augmentation Directions

Such communication-intent recognition frameworks are integral to next-generation automated ATC systems, supporting safety monitoring and reducing workload for human controllers. Although the dataset in this study originates from a single airport, the framework was designed to promote transferability across diverse communication environments. The dual-pipeline architecture explicitly captures two largely independent information channels: (1) standardized linguistic content produced under FAA phraseology conventions (e.g., position reports, intentions), and (2) time–frequency acoustic patterns tied to speech dynamics and radio transmission artifacts. This separation increases the likelihood that feature representations learned here will be transferred to other airports that follow the same operational phraseology [12].

The robustness gains from systematic audio augmentations (time stretching, additive noise, temporal shifting) suggest that the models learn invariances that extend beyond the immediate recording conditions; these invariances are desirable for cross-site deployment. In practical terms, deployment can be staged by integrating the classifier with existing General Audio Recording Device (GARD)-style monitoring systems to provide automated, preliminary operational counts; human review or partial fusion with ADS-B or other surveillance sources can be used for verification until complete confidence in cross-site performance is achieved [14].

A promising complementary strategy to address the limited availability of labeled aviation audio is generative data synthesis. Recent advances in generative AI for audio and speech—including robust text-to-speech style transfer and audio language modeling—make it feasible to synthetically expand training corpora to cover diverse accents, phrase variants, overlapping transmissions, and background acoustic scenes. For example, models that perform style-aware text-to-speech synthesis can generate realistic pilot utterances in a variety of speaker styles and channel conditions, improving coverage of rare or under-represented phraseologies [26,27]. AudioLM-style generative approaches produce high-fidelity audio sequences conditioned on linguistic or acoustic prompts. They can be used to simulate realistic background traffic, engine noise, and channel artifacts for augmentation [25]. When combined with the augmentation strategies used in this study, generative augmentation may substantially increase the effective diversity of training data without the cost and logistics of large multi-site field campaigns.

However, synthetic data must be used carefully. Domain shift between synthetic and real recordings can introduce biases; therefore, synthetic augmentation should be validated using a hold-out set of real recordings and, where possible, by human expert review. Techniques such as domain adversarial training, confidence-based sample weighting, and targeted real-world fine-tuning could mitigate such biases and improve real-world performance.

5.3. Practical Deployment Considerations

For real-world adoption, several operational factors deserve attention. First, the textual pipeline’s reliance on ASR suggests that a deployment should monitor ASR confidence scores and preferentially route low-confidence segments for spectral classification or subject-matter expert (SME) review. Second, computational efficiency is essential for continuous monitoring: lightweight CNN architectures, model quantization, or edge-inference strategies can enable near-real-time operation on modest hardware. Third, privacy, policy, and regulatory considerations must be addressed when recording and processing radio communications; transparent data-use agreements with airports and stakeholders are recommended.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we proposed a versatile, infrastructure-free framework for estimating aircraft operations at non-towered airports by classifying pilot communications through a dual-pipeline machine learning approach. The textual pipeline employed automatic speech recognition (ASR) with TF–IDF features to capture semantic content, while the spectral pipeline extracted Mel-spectrograms to preserve acoustic characteristics. A comprehensive evaluation across traditional and deep learning models showed that spectral representations combined with convolutional architectures achieved the highest performance, with F1-scores above 0.91. Data augmentation further enhanced robustness to noise and speech variability, confirming the approach’s suitability for real-world communication data.

Beyond accurate operation estimation, the proposed method contributes to the broader vision of intelligent, data-driven air traffic management. The framework is computationally lightweight, requires no additional infrastructure, and can be integrated with existing airport radio monitoring systems to provide scalable, automated operational insights.

Future research will emphasize multi-airport validation and explore the use of generative AI for data synthesis, where recent advances in text-to-speech and audio language modeling can simulate diverse pilot–controller exchanges and environmental noise conditions [25,26,27]. Such generative augmentation has the potential to overcome dataset limitations, increase model diversity, and accelerate the deployment of AI-enabled communication analysis tools for aviation monitoring, safety, and virtual tower applications. By enhancing automated interpretation of radio communications, the proposed framework advances the integration of AI and machine learning into ATC and general aviation operations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.T., C.H., C.Y. and X.Z.; methodology, A.A.T., C.H., and X.Z.; software, A.A.T. and M.A.; validation, A.A.T. and M.A.; formal analysis, A.A.T., C.H. and M.A.; investigation, A.A.T. and M.A.; resources, A.A.T., M.A. and X.Z.; data curation, C.H. and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.T., C.H. and M.A.; writing—review and editing, C.H., C.Y. and X.Z.; visualization, A.A.T. and M.A.; supervision, C.H. and X.Z.; project administration, C.H. and X.Z.; funding acquisition, C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Faculty Research Development Program (AWD00890).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author, Chuyang Yang.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATC | Air Traffic Control |

| FAA | Federal Aviation Administration |

| CTAF | Common Traffic Advisory Frequency |

| UNICOM | Universal Communications Frequency |

| ASR | Automatic Speech Recognition |

| TF-IDF | Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| AUPR | Area Under the Precision–Recall Curve |

| MCC | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

| ADS-B | Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PSD | Power Spectral Density |

References

- Federal Aviation Administration. Air Traffic by the Numbers. 2024. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/by_the_numbers/media/Air_Traffic_by_the_Numbers_2024.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Counting Aircraft Operations at Non-Towered Airports; Airport Cooperative Research Program; Washington, DC, USA, 2007. Available online: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/23241/counting-aircraft-operations-at-non-towered-airports (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Transportation Research Board; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Evaluating Methods for Counting Aircraft Operations at Non-Towered Airports; Muia, M.J., Johnson, M.E., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mott, J.H.; Sambado, N.A. Evaluation of acoustic devices for measuring airport operations counts. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Mott, J.H.; Hardin, B.; Zehr, S.; Bullock, D.M. Technology assessment to improve operations counts at non-towered airports. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Aviation Manufacturers Association. Contribution of General Aviation to the U.S. Economy in 2023. 2025. Available online: https://gama.aero/wp-content/uploads/General-Aviations-Contribution-to-the-US-Economy_Final_021925.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Badrinath, S.; Balakrishnan, H. Automatic speech recognition for air traffic control communications. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2676, 798–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Deng, L.; Chen, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, B. A real-time ATC safety monitoring framework using a deep learning approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 21, 4572–4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Tang, P. Automatic communication error detection using speech recognition and linguistic analysis for proactive control of loss of separation. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021, 2675, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohneiser, O.; Ahmed, U. Text-to-speech application for training of aviation radio telephony communication operators. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, X.; Chen, H. Audio scanning network: Bridging time and frequency domains for audio classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, No. 10. pp. 11355–11363. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Aviation Administration. Non-Towered Airport Flight Operations; Advisory Circular No. 90-66C; 2023. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/documentlibrary/media/advisory_circular/ac_90-66c.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Mott, J.H.; Bullock, D.M. Estimation of aircraft operations at airports using mode-C signal strength information. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 19, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, J.H.; McNamara, M.L.; Bullock, D.M. Accuracy assessment of aircraft transponder–based devices for measuring airport operations. Transp. Res. Rec. 2017, 2626, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadmanesh, M.; Rashidi, A.; Marković, N. General aviation aircraft identification at non-towered airports using a two-step computer vision-based approach. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 48778–48791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretto, M.; Dorbolò, L.; Giannattasio, P.; Zanon, A. Aircraft operation reconstruction and airport noise prediction from high-resolution flight tracking data. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 135, 104397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrikar, J.; Dantas, J.; Moon, B.; Hamidi, M.; Ghosh, S.; Keetha, N.; Higgins, I.; Chandak, A.; Yoneyama, T.; Scherer, S. Image, speech, and ADS-B trajectory datasets for terminal airspace operations. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadmanesh, M.; Marković, N.; Rashidi, A. Automated video-based air traffic surveillance system for counting general aviation aircraft operations at non-towered airports. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2677, 250–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida Department of Transportation. Operations Counting at Non-Towered Airports Assessment; FDOT: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2018; Available online: http://www.invisibleintelligencellc.com/uploads/1/8/4/9/18495640/2018_ops_count_project_final_report_09102018.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Yang, C.; Huang, C. Natural language processing (NLP) in aviation safety: Systematic review of research and outlook into the future. Aerospace 2023, 10, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreshidi, I.; Moulitsas, I.; Jenkins, K.W. Advancing aviation safety through machine learning and psychophysiological data: A systematic review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 5132–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Ospina, A.E.; Solarte-Sanchez, M.A.; Vega-Escobar, L.S.; Isaza, C.; Martínez-Vargas, J.D. Graph-based audio classification using pre-trained models and graph neural networks. Sensors 2024, 24, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Tan, X.; Yang, B.; Yang, K.; Zhang, J.; Yu, J. Real-time controlling dynamics sensing in air traffic system. Sensors 2019, 19, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Google Cloud. Speech-to-text: Automatic Speech Recognition. 2025. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/speech-to-text (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Borsos, Z.; Marinier, R.; Vincent, D.; Kharitonov, E.; Pietquin, O.; Sharifi, M.; Zeghidour, N. AudioLM: A language modeling approach to audio generation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2023, 31, 2523–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ren, Y.; Liu, J.; Cui, C.; Zhao, Z. Generspeech: Towards style transfer for generalizable out-of-domain text-to-speech. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 10970–10983. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.S.; Kuznetsova, A.; Manocha, D.; Hershey, J.; Kristjansson, T.; Kim, M. Generative data augmentation challenge: Zero-shot speech synthesis for personalized speech enhancement. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing Workshops (ICASSPW), Turin, Italy, 24–29 April 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.