Continuous Detonation Combustor Operating on a Methane–Oxygen Mixture: Test Fires, Thrust Performance, and Thermal State

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Propellant Components

2.2. Test Rig and Combustor

3. Test Fire Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Combustor Inspection Results After Test Fire 3

References

- Klepikov, I.; Katorgin, B.; Chvanov, V. The new generation of rocket engines, operating by ecologically safe propellant “liquid oxygen and liquefied natural gas(methane)”. Acta Astronaut. 1997, 41, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeseler, D.; Goetz, A.; Mäding, C.; Roubinski, V.; Khrissanfov, S.; Berejnoy, V. Testing of LOX-Hydrocarbon Thrust Chambers For Future Reusable Launch Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 38th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Indianapolis, Indiana, 7–10 July 2002. AIAA Paper 2002-38454. [Google Scholar]

- Zel’dovich, Y.B. To the Question of Energy Use of Detonation Combustion. J. Technol. Phys. 1940, 10, 1453–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiser, W.H.; Pratt, D.T. Thermodynamic cycle analysis of pulse detonation engines. J. Propuls. Power 2002, 18, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.K.; Braun, E.M. Rotating detonation wave propulsion: Experimental challenges, modeling, and engine concepts. J. Propuls. Power 2014, 30, 1125–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heister, S.D.; Smallwood, J.; Harroun, A.; Dille, K.; Martinez, A.; Ballintyn, N. Rotating Detonation Combustion for Advanced Liquid Propellant Space Engines. Aerospace 2022, 9, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stechmann, D.; Lim, D.; Heister, S.D. Experimental study of a high pressure rotating detonation wave combustor for rocket applications. In Proceedings of the 6th EUCASS, Krakow, Poland, 29 June–3 July 2015. EUCASS Paper 372. [Google Scholar]

- Frolov, S.M.; Aksenov, V.S.; Ivanov, V.S.; Medvedev, S.N.; Shamshin, I.O.; Yakovlev, N.N.; Kostenko, I.I. Rocket engine with continuous detonation combustion of the natural gas–oxygen propellant system. Dokl. Phys. Chem. 2018, 478, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykovsky, F.A.; Zhdan, S.A. Continuous Spin Detonation; SB RAS Publs: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2013; 423p. [Google Scholar]

- Paxson, D.E.; Perkins, H.D. A simple model for rotating detonation rocket engine sizing and performance estimates. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2021 Forum, Virtual Event, 11–15+19–21 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tchvanov, V.K.; Frolov, S.M.; Sternin, E.L. Liquid detonation rocket engine. In Proceedings of the NPO Energomash, Moscow Region, Russia, 17 August 2012; Volume 29, pp. 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, V.; Gutmark, E. Rotating detonation combustors and their similarities to rocket instabilities. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2019, 73, 182–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasley, T. NASA’s Rotating Detonation Rocket Engine Development. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20250000643/downloads/NASAs%20RDRE%20Dev%20AAS%20Teasley%20Final.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Methane-Powered Rocket to Come Twice as Cheap as Soyuz-2 Carrier—Developers. Available online: https://tass.com/science/1109553 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Frolov, S.; Aksenov, V.; Ivanov, V. Experimental proof of Zel’dovich cycle efficiency gain over cycle with constant pressure combustion for hydrogen–oxygen fuel mixture. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 6970–6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindracki, J.; Wolański, P.; Gut, Z. Experimental research on the rotating detonation in gaseous fuels–oxygen mixtures. Shock Waves 2011, 21, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, V.S.; Aksyonov, V.S.; Frolov, S.M.; Shamshin, I.O. Experimental studies of a stand sample of rocket engine with continuous-detonation combustion of natural gas–oxygen mixture. Goren. Vzryv 2016, 9, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- RD-107A Engine. Available online: https://www.uecrus.com/products-and-services/products/raketnye-dvigateli/dvigatel-rd-107a/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Bennewitz, J.W.; Bigler, B.; Danczyk, S.; Hargus, W.A.; Smith, R.D. Performance of a rotating detonation rocket engine with various convergent nozzles. In Proceedings of the AIAA Propulsion and Energy 2019 Forum, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 19–22 August 2019; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2019; pp. 2019–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.D.; Stanley, S.B. Experimental investigation of rotating detonation rocket engines for space propulsion. J. Propuls. Power 2021, 37, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, K.; Yokoo, R.; Kim, J.; Kawasaki, A.; Matsuoka, K.; Kasahara, J.; Matsuo, A.; Funaki, I.; Nakata, D.; Uchiumi, M.; et al. Experimental performance validation of a rotating detonation engine toward a flight demonstration. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2019 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–11 January 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, K.; Matsuoka, K.; Matsuyama, K.; Kawasaki, A.; Watanabe, H.; Itouyama, N.; Ishihara, K.; Buyakofu, V.; Noda, T.; Kasahara, J. Flight demonstration of detonation engine system using sounding rocket S-520-31: Performance of rotating detonation engine. In Proceedings of the AIAA SciTech 2022 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 3–7 January 2022; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Rong, G.; Shen, D.; Wu, K.; Wang, J. Experimental research on the performance of hollow and annular rotating detonation engines with nozzles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 218, 119339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasley, T.W.; Fedotowsky, T.M.; Gradl, P.R.; Austin, B.L.; Heister, S.D. Current state of NASA continuously rotating detonation cycle engine development. In Proceedings of the AIAA SciTech 2023 Forum, National Harbor, MD, USA, 23–27 January 2023; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, T.; Knowlen, C.; Kurosaka, M. Scale effects on rotating detonation rocket engine operation. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2024, 19, 100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, M.-S.; Roh, T.-S.; Lee, H.J. Analysis of development trends for rotating detonation engines based on experimental studies. Aerospace 2024, 11, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolov, S.M.; Smetanyuk, V.A.; Ivanov, V.S.; Basara, B. The influence of the method of supplying fuel components on the characteristics of a rotating detonation engine. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2021, 193, 511–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolov, S.M.; Aksenov, V.S.; Ivanov, V.S.; Medvedev, S.N.; Shamshin, I.O. Flow structure in rotating detonation engine with separate supply of fuel and oxidizer: Experiment and CFD. In Detonation Control for Propulsion: Pulse Detonation and Ro-tating Detonation Engines; Li, J.-M., Teo Boo Cheong Khoo, C.J., Wang, J.-P., Wang, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 39–59. [Google Scholar]

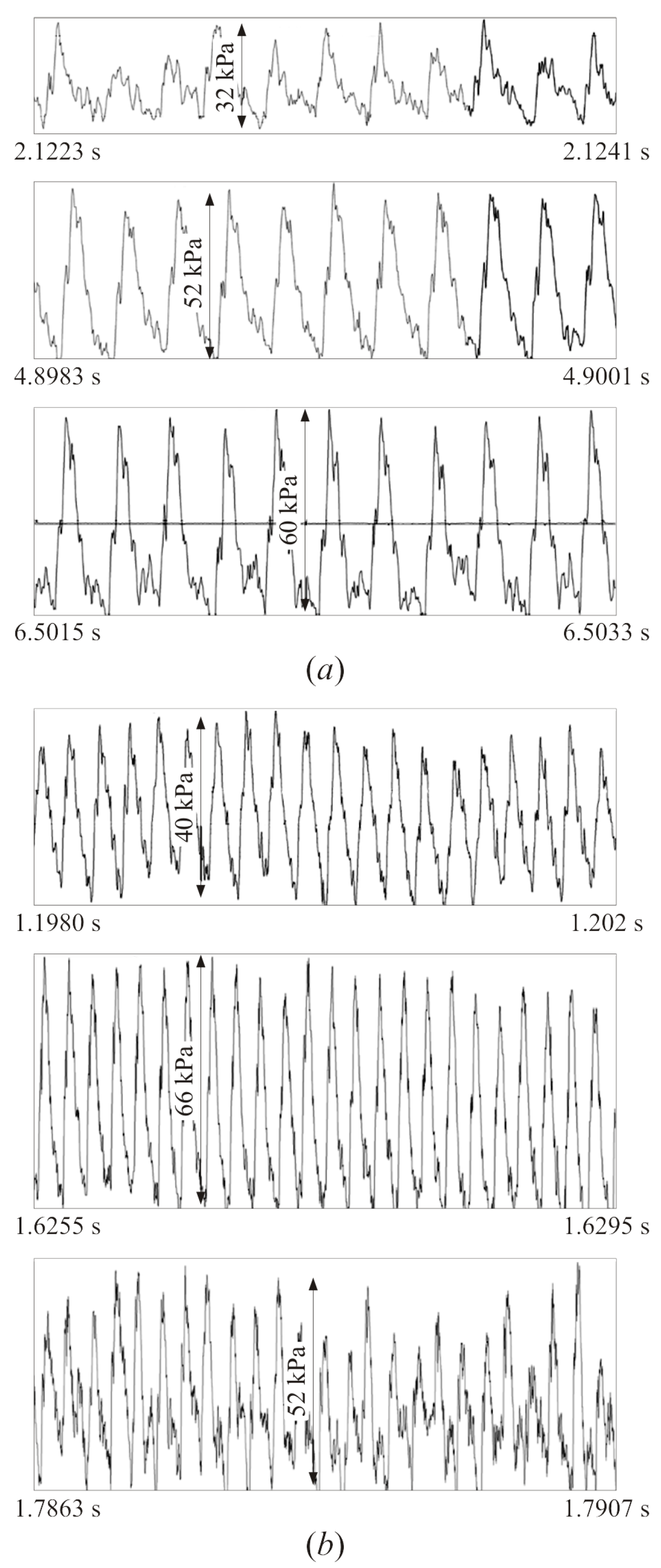

- Ivanov, V.S.; Frolov, S.M.; Sergeev, S.S.; Mironov, Y.M.; Novikov, A.E.; Schultz, I.I. Pressure measurements in detonation engines. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2021, 235, 2113–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Parameter | Sensor | Measuring Range | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Methane pressure, receiver | Kurant DA | 0–20 MPa | 0.5% |

| 2 | Oxygen pressure, receiver | Kurant DA | 0–20 MPa | 0.5% |

| 3 | Methane pressure, CC plenum | Kurant DA | 0–2.5 MPa | 0.5% |

| 4 | Oxygen pressure, CC plenum | Kurant DA | 0–2.5 MPa | 0.5% |

| 5 | Water temperature at exits of cooling jackets (3 pc.) | IFM TM2405 | –50–150 °C | 0.5% |

| 6 | Thrust | Tenso-M M50-0.50-C3 | 0–5000 N | 0.02% |

| 7 | Pressure pulsations in CC | PCB 113B24 | 0–6.9 MPa | 1% |

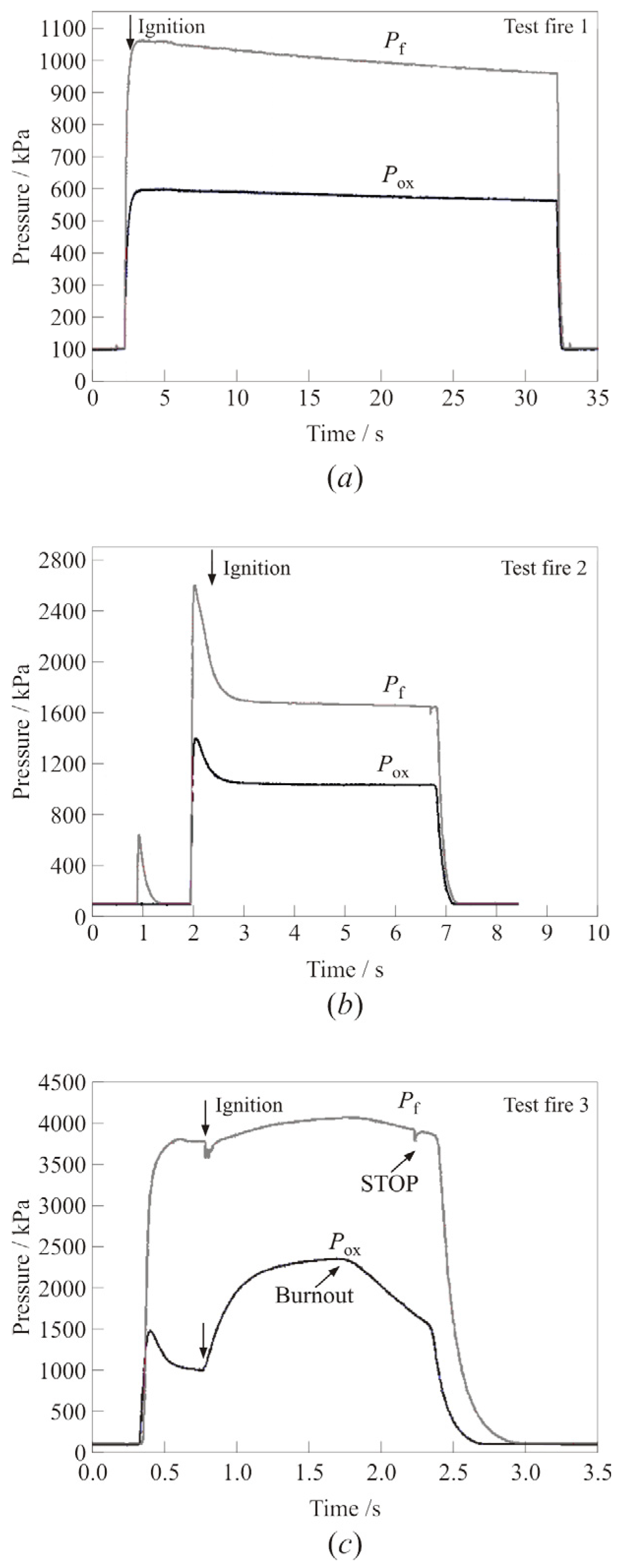

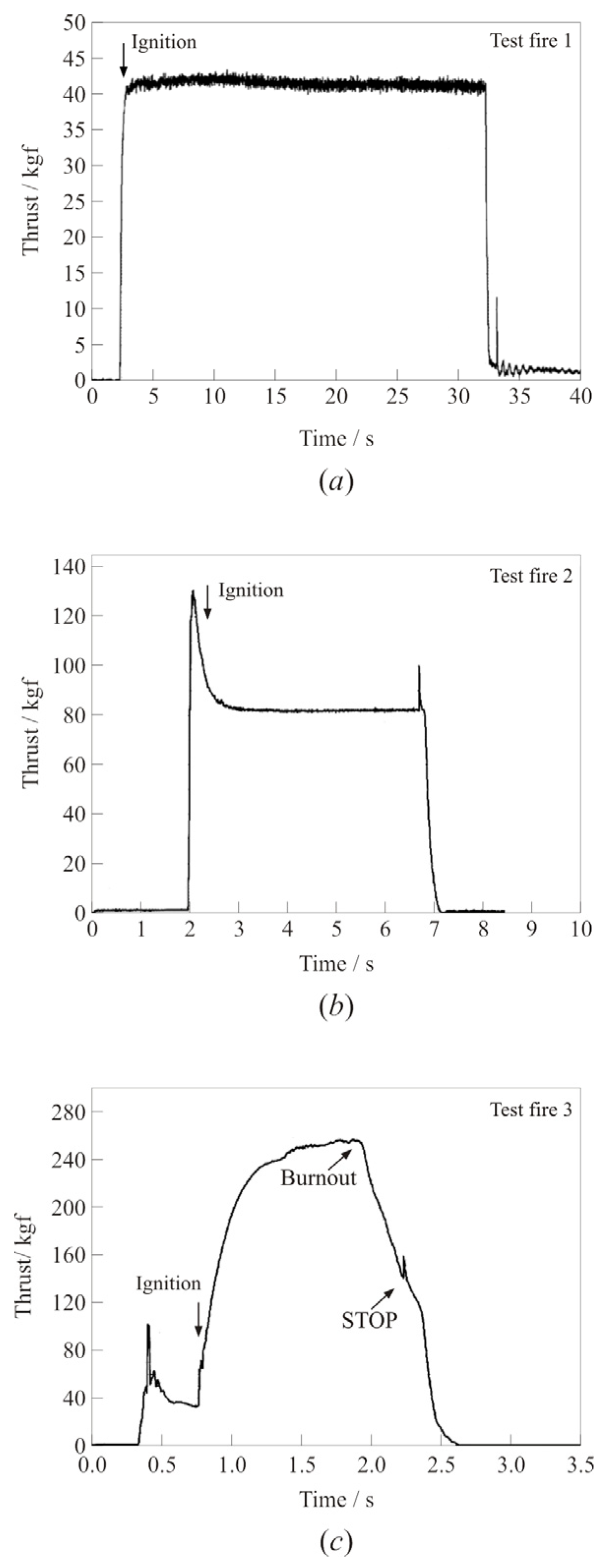

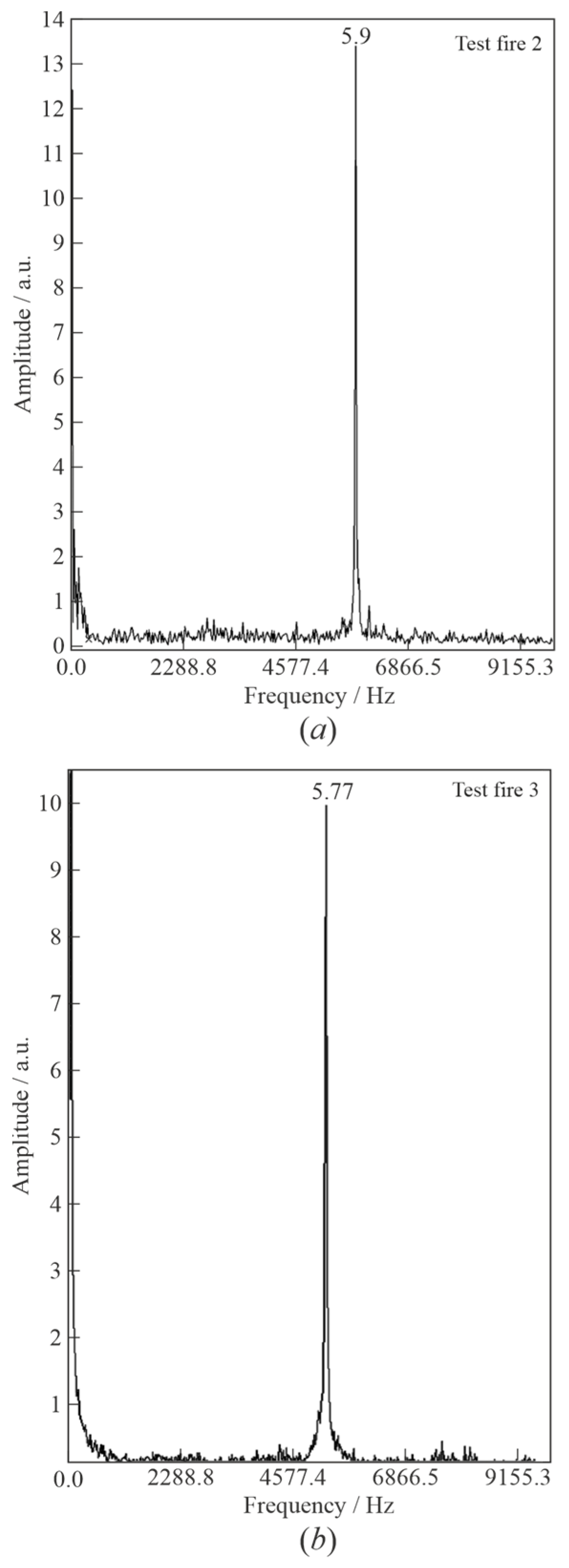

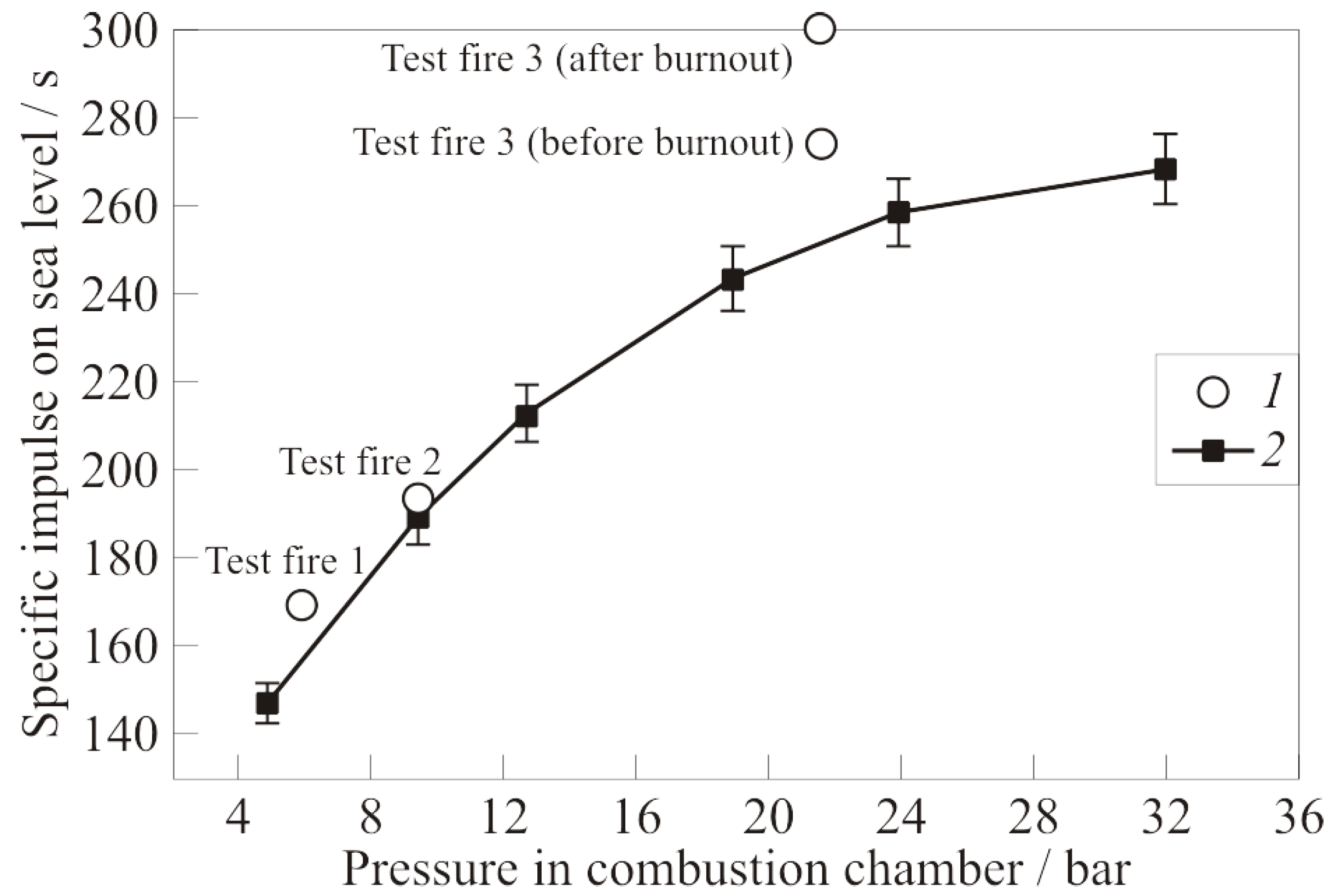

| Test Fire | t s | G kg/s | Ф | Pox kPa | Pf kPa | PCC kPa | f kHz | n | D m/s | F N | Isp s | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

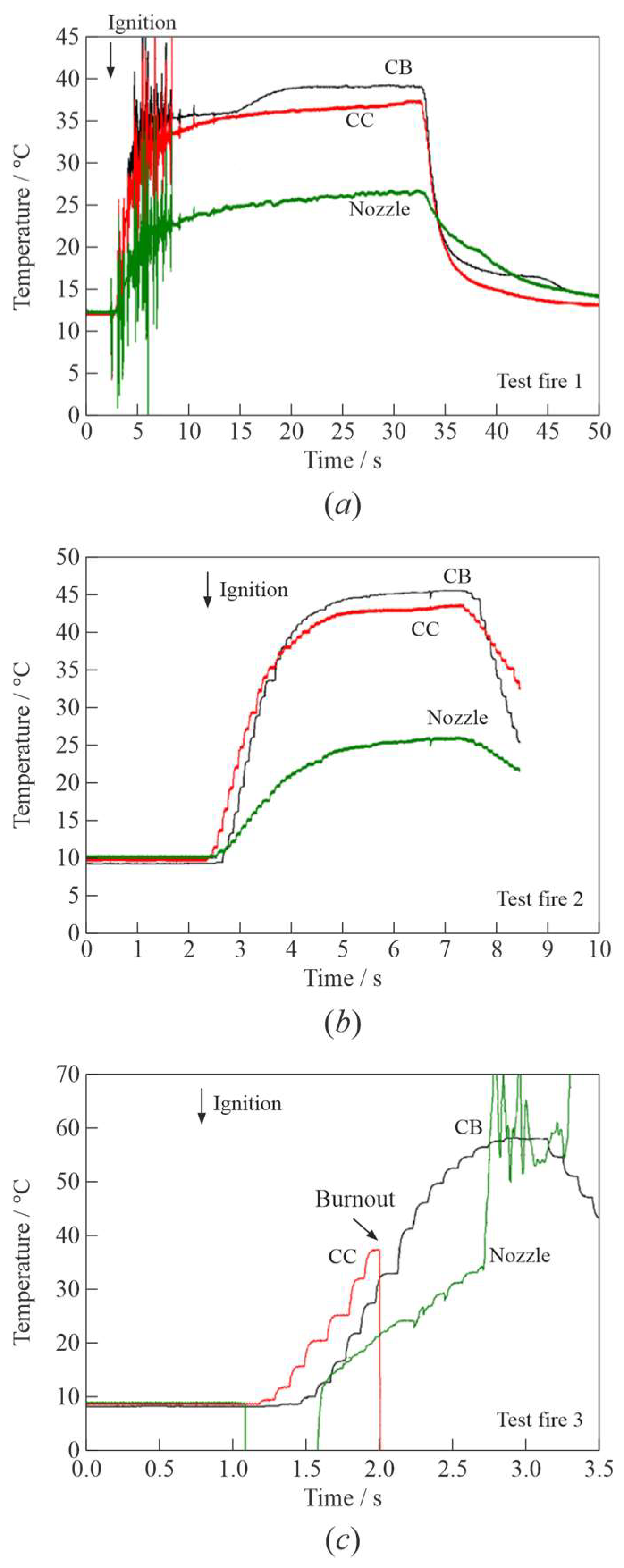

| 1 | 30 | 0.232 | 1.50 | 600 | 1060 | 550 | - | - | - | 402 | 177 | 16.1 |

| 2 | 5 | 0.429 | 1.22 | 1040 | 1670 | 950 | 5.90 | 1 | 1853 | 804 | 191 | 9.5 |

| 3 | 2 | 0.867 | 1.17 | 2340 | 4055 | 2150 | 5.77 | 1 | 1812 | 2550 | 300 | 10.7 |

| Test Fire | Gw kg/s | °C | °C | Water Heating Power kW | Average Heat Flux MW/m2 | kW | QCC MW | % | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB | CC | Nozzle | CB | CC | Nozzle | CB | CC | Nozzle | CB | CC | Nozzle | |||||

| 1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 12.5 | 26.5 | 24.5 | 14.5 | 178 | 165 | 97 | 7.6 | 10.8 | 2.7 | 440 | 3.2 | 13.8 |

| 2 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 9.5 | 36.3 | 34 | 15.8 | 213 | 171 | 93 | 9.1 | 11.2 | 2.6 | 478 | 5.0 | 9.5 |

| 3 * | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 8.7 | 58.8 | 73.1 | 56.9 | 346 | 368 | 333 | 14.8 | 24.1 | 9.26 | 1047 | 9.8 | 10.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Frolov, S.M.; Ivanov, V.S.; Kozarenko, Y.V.; Shamshin, I.O. Continuous Detonation Combustor Operating on a Methane–Oxygen Mixture: Test Fires, Thrust Performance, and Thermal State. Aerospace 2026, 13, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010030

Frolov SM, Ivanov VS, Kozarenko YV, Shamshin IO. Continuous Detonation Combustor Operating on a Methane–Oxygen Mixture: Test Fires, Thrust Performance, and Thermal State. Aerospace. 2026; 13(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrolov, Sergey M., Vladislav S. Ivanov, Yurii V. Kozarenko, and Igor O. Shamshin. 2026. "Continuous Detonation Combustor Operating on a Methane–Oxygen Mixture: Test Fires, Thrust Performance, and Thermal State" Aerospace 13, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010030

APA StyleFrolov, S. M., Ivanov, V. S., Kozarenko, Y. V., & Shamshin, I. O. (2026). Continuous Detonation Combustor Operating on a Methane–Oxygen Mixture: Test Fires, Thrust Performance, and Thermal State. Aerospace, 13(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace13010030