Abstract

With the rapid development of the aviation industry, the complexity and intertwinement of various aviation activities have been continuously increasing, leading to the escalating of potential conflicts in limited airspace resources. Efficient airspace management is crucial for flight safety. To address the issues of conflict detection and resolution in localized high-density multi-airspace environments, this paper proposes an end-to-end integrated framework that integrates octree spatial partitioning, hierarchical conflict detection, and a conflict resolution module based on the Improved Whale Migration Algorithm (IWMA). This framework takes the airspace safety separation standards as constraints and the minimization of multi-airspace adjustment offsets as the optimization objective. The IWMA integrates diverse population structures and multi-strategy optimization technologies to balance global search and local exploration capabilities and avoid falling into local optima. Experiments on high-density conflict scenarios of different scales have verified the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed method. Simulation results show that compared with traditional detection methods and other classic optimization algorithms, the conflict detection and resolution method proposed in this paper can quickly and efficiently provide reliable solutions for multi-airspace conflict issues.

1. Introduction

Currently, with the rapid development of the aviation industry, the specific characteristics of flight activities are manifested in large spatiotemporal spans and complex airspace usage, leading to prominent flight conflicts. Efficient airspace management measures are of significant importance for the safe operation of aviation activities [1,2]. Airspace conflict refers to the situation where multiple aircraft occupy the same space simultaneously or fail to meet the separation standards required for safe airspace operation. Since airspace is a limited four-dimensional resource and serves as a medium for aviation activities, effectively mitigating airspace conflicts has become an urgent issue that needs to be addressed.

Airspace Conflict Detection and Resolution (CD&R) is a core aspect of airspace management, with its fundamental goal being to ensure safe separation between aviation activities. Logically, an effective airspace CD&R system primarily includes a unified spatiotemporal identification framework for space and a detection and resolution system for identifying and resolving airspace conflicts. Traditional airspace conflict resolution methods mainly rely on latitude and longitude coordinates and radar assistance for conflict identification and resolution. This approach involves high computational complexity and low efficiency, and it lacks flexibility when dealing with multi-dimensional constraints such as horizontal position, altitude, and time. To further enhance the efficiency of conflict detection and resolution, research on the spatial identification framework and the detection and resolution is of great significance.

Based on the considerations mentioned above, this paper proposes a layered conflict detection mechanism and an IWMA-based conflict resolution strategy based on the octree spatial partitioning model to address the optimization problem of complex airspace conflicts. To simplify the model validation method, this study adopts the Cartesian reference frame for modeling and analysis, targeting operational conflict issues in local small-scale airspaces. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- Spatial Representation: A three-dimensional octree spatial grid partitioning and Z-curve encoding model is developed, enabling efficient spatial indexing. This establishes a unified multi-scale spatial identification system for subsequent conflict detection and resolution tasks.

- Fast Conflict Detection: We propose a layered conflict detection mechanism combining coarse and fine filtering. In the coarse filtering phase, the grid-based airspace Morton encoding is used for rapid identification of potential conflicts, which are then further evaluated using precise geometric calculations, significantly improving detection efficiency.

- Airspace Conflict Resolution: A multi-dimensional cost conflict resolution model is constructed to avoid the issue of optimizing only a single dimension during the resolution process, thereby improving the overall quality of the resolution. Additionally, different optimization strategies are applied to the WMA, based on the characteristics of the diverse population, to achieve a dynamic balance between exploration and exploitation, seeking more effective conflict resolution solutions. Compared to classical methods, this approach significantly improves the success rate, convergence speed, and adjustment efficiency.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 analyzes the state of research relevant to the content of this paper. Section 3 introduces the fundamental theories of spatial partitioning and encoding, as well as related research on conflict resolution modeling. Section 4 elaborates in detail on the hierarchical conflict detection mechanism proposed in this paper, along with the conflict resolution strategy based on the Improved Whale Migration Algorithm (IWMA). Section 5 conducts simulation experiments with different airspace scales, and verifies the effectiveness of the method proposed in this paper through comparative experiments. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the research findings and discusses potential directions for future work.

2. Literature Review

To address the limitations of the traditional latitude and longitude coordinate system in spatial representation, researchers have proposed the Discrete Global Grid System (DGGS), which is considered a promising structure for global geospatial information representation [3]. The core concept of DGGS is to discretize space into a hierarchical set of grid cells and to manage spatio-temporal information through specific encoding rules, thereby providing a unified and quantifiable spatial model. Compared with the conventional latitude–longitude system, which suffers from drawbacks when handling complex, high-dimensional and large-scale spatial data, DGGS offers an efficient solution for massive spatial-data management. Among existing implementations, H3—an open-source hexagonal indexing library developed by Uber—stands out for its high flexibility and scalability and has been widely adopted in various geographic-information systems [4]. Nevertheless, H3 still faces technical challenges, especially in partitioning complex geometries and irregular regions. To overcome these issues, researchers have introduced multi-level encoding and adaptive mesh-refinement strategies. Tong et al. [5] addressed the hierarchical encoding challenges of the Hexagonal Global Discrete Grid System (DGGS) by introducing the Hexagonal Quaternary Balanced Structure (HQBS), which solves the problem of insufficient self-similarity and difficulty in building hierarchies in traditional hexagonal grids. Wu et al. [6] proposed a non-rigid hierarchical discrete grid structure, distinct from traditional rigid grids, which allows consistent identification of targets at any position on the same scale. Hasbestan et al. [7] introduced a binary octree generation method that utilizes the continuity of the Z-curve (Morton encoding), solving the problem of adaptive grid refinement for complex geometric boundaries. Liu et al. [8] proposed a hybrid coding algorithm for spatial partitioning, which achieves vector data compression while maintaining geometric consistency in multi-scale visualization.

The airspace conflict detection problem can essentially be viewed as a geometric query problem in the spatial and temporal dimensions. Traditional pairwise comparison conflict detection methods often suffer from limitations such as low algorithmic efficiency, insufficient detection accuracy, and incomplete consideration of dimensions when handling large-scale, multi-dimensional airspace conflicts. To overcome these limitations, recent research has shifted towards spatial data structures and grid indexing techniques to accelerate conflict queries, reducing the computational complexity from to . Yang et al. [9] proposed a method based on global airspace grid encoding and spatiotemporal data grids, transforming conflict detection into a grid state query problem, achieving global unified encoding and efficient retrieval. Miao et al. [10] proposed a partitioned indexing and priority strategy based on the GEOSOT multi-level grid spatiotemporal index, which supports dynamic and static conflict detection while further accelerating the conflict detection process. Qu et al. [11] constructed a regular icosahedron diamond discrete grid model to address the accuracy issues in high-dimensional region conflict detection. Cai et al. [12] proposed a method for constructing airspace association networks based on complex network theory, using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to comprehensively calculate time, space, and family correlation degrees to determine conflicts.

Conflict resolution in multi-airspace is essentially a multi-objective optimization problem. Compared to traditional single-objective methods, which may lead to suboptimal or infeasible solutions in multi-objective conflict scenarios, multi-objective optimization methods offer the core advantage of providing a set of non-dominated solutions (Pareto optimal solutions) through Pareto optimal theory. This allows for a comprehensive reflection of the trade-offs between different objectives, offering a complete solution set and enhancing decision-making flexibility. In recent years, substantial research has been conducted to efficiently address conflict resolution problems. Hong et al. [13] proposed a two-level hierarchical framework to resolve multi-sector flight conflicts, where the high-level constructs aircraft maneuver constraints, and the low-level conflict resolution is solved through an integer linear programming model under the maneuver constraints. Malaeket al. [14] proposed a 3D maneuver algorithm that considers both conflict resolution and original flight route recovery for high-density airspace multi-aircraft conflict problems. Xiao et al. [15] proposed a generalized conflict resolution method based on traditional spatiotemporal relationships, incorporating multiple constraint factors such as weather, terrain, and traffic, along with trajectory optimization. This method generates flight paths with safe separation using the artificial potential field method. Jenie et al. [16] proposed a Monte Carlo method to resolve high-density airspace conflict simulation scenarios, employing both the velocity obstacle method and the “right-hand rule” conflict resolution protocols to solve the problem of fewer conflicts and difficult simulations in low-density airspace, achieving the evaluation of airspace conflict resolution safety.

3. Related Work

3.1. Problem Description

In the actual air traffic management process, airspace conflicts arise when airspace regions overlap or intersect within the spatiotemporal domain due to the differing mission nature and application areas of aircraft. In the face of complex, localized multi-airspace conflict scenarios, it is crucial to quickly identify conflict pairs, resolve conflicts in accordance with flight safety separation minimums standards, and ensure flight safety while maintaining flight order, thereby maximizing the utilization efficiency of various airspace regions. In this study, the airspace under consideration refers to the space occupied by aircraft within the spatiotemporal range, with airspace described over the maximum possible spatiotemporal extent, without considering the specific flight performance parameters of the individual aircraft.

To efficiently address the conflict detection and resolution problem in complex localized multi-airspace scenarios, we propose an integrated detection and resolution framework. This framework combines spatial octree-based grid partitioning, a layered conflict detection mechanism, and the IWMA conflict resolution strategy. Among them, the establishment of a multi-scale spatial grid model is the foundational work for solving the related problems. Through grid encoding, it enables a unique representation of spatial positions and rapid indexing, which is of great significance for conflict detection and resolution. The specific framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Multi-Airspace Conflict Detection and Resolution Integrated System Framework.

3.2. Spatial Grid Model

3.2.1. Octree Spatial Grid Partitioning

The Octree is a recursive three-dimensional spatial data structure, whose core concept is to recursively divide three-dimensional space into eight smaller sub-cubes, and combine these divisions with a tree-like hierarchical storage structure for organizing and managing spatial information. Traditional latitude and longitude grids use a global uniform resolution, making it difficult to capture local details when representing spatial relationships. Moreover, they suffer from significant distortions at high latitudes. In contrast, the octree spatial structure uses cubic units, with uniform space division and the ability to support local spatial refinement, enabling precise representation of the properties of any point in space. The Quadtree, which is the two-dimensional counterpart of the octree, can only handle planar relationships and is inefficient for representing three-dimensional spatial topologies [17,18]. Overall, the octree spatial data structure excels in spatial problem-solving by providing high spatial utilization, a clear hierarchical structure, and support for multi-resolution representation. It is particularly effective in representing the spatial topological relationships of multi-airspace environments.

In the recursive subdivision process of three-dimensional space, the root node represents the entire airspace. Each level recursively generates the next level of nodes by dividing the parent node into eight sub-blocks. This recursive subdivision method continuously partitions the space into smaller regions until the specified resolution or coverage accuracy requirement is met. The spatial grid construction process for any given airspace region is as follows:

- The root node represents the airspace to be subdivided, with its spatial range denoted by , and the maximum resolution level denoted by ;

- Recursive subdivision: each child node represents one-eighth of the parent node. The side length of the grid cell at each level and the coordinates of the sub-grid center are denoted, respectively, as:

where

: represents the current grid subdivision level;

: denotes the index of the grid.

- 3.

- Adaptive multi-level spatial structure: The complexity and regional density of the airspace determine the level of refinement in each region. Adaptive subdivision is performed based on the complexity and local details of the airspace, with fine-grained subdivision applied to locally high-density regions, and coarse-grained subdivision applied to low-density and sparse regions.

As shown in Figure 2, the multi-level spatial grid data structure based on an octree can efficiently represent complex three-dimensional airspace. Each node in the tree corresponds to a cubic sub-region, characterized by its center position, size, level, and occupancy status. Due to the recursive subdivision property of the octree spatial grid structure, it exhibits good adaptability and low computational complexity when processing large-scale three-dimensional airspace data, thereby effectively improving computational efficiency. The scale correspondence of each level is shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Octree Grid Spatial Subdivision Structure.

Table 1.

Correspondence Across Scale Levels.

In the process of addressing conflict detection and resolution across multiple airspaces using grid-based methods, each airspace is converted into a set of occupied grids through a sampling-based overlap estimation algorithm. Essentially, this means that within any spatiotemporal range, the relevant grids must be non-overlapping and must maintain a certain safety buffer. To further improve the efficiency of conflict detection and reduce the cost of conflict resolution, this study classifies grids into two types: entity grids and buffer grids . The entity grid represents the basic grid of the airspace itself, while the buffer grid is generated based on the entity grid and is mainly used to account for the safety buffer between airspaces. The classification of the two grid types is based on the spatial relationship between the airspace shape mapped to the grid, with the determination criteria as follows:

- If the grid voxel is completely covered by the airspace, it is directly classified as an entity grid ;

- If it partially intersects with the airspace, it is classified based on the ratio of overlapping volume :

where:

: denotes the volume of the grid cell;

: represents the volume of the airspace;

: is the threshold for overlap classification.

If , it is classified as an entity grid ; otherwise, it is classified as a buffer grid .

3.2.2. Morton Encoding Spatial Index

Morton encoding, also known as Z-order encoding, is a method that maps points in a multi-dimensional space to a one-dimensional space, enabling each grid cell in the space to be uniquely identified. The core concept is to use a bit interleaving technique to achieve linearization and hierarchical indexing of three-dimensional space. Through this interleaving approach, Morton encoding ensures that spatially adjacent locations have small differences in the one-dimensional encoding space, thereby preserving spatial locality. This encoding method provides efficient spatial indexing capabilities for the octree-based spatial grid data structure [19,20].

For any point in three-dimensional space, its Morton encoding can be mathematically defined as:

where represent the -th binary bit of the coordinates respectively. The Morton encoding rule extracts the -th bit of in order from the least significant bit to the most significant bit, and places them sequentially into the positions of the final code.

As shown in Figure 3, in the octree spatial grid, all grid nodes are encoded using the Morton encoding method by recursively subdividing each node. With each additional level in the octree, the Morton code increases by 3 bits, and the encoding allows for rapid querying of node positions and determining node relationships. In summary, the spatial data structure model constructed through octree spatial subdivision and Morton encoding enables a fast and consistent mapping from spatial objects to grids, nodes, and spatial positions, thereby significantly improving the efficiency of spatial queries and conflict detection.

Figure 3.

Morton Encoding Rule Diagram.

3.3. Multi-Objective Optimization Conflict Resolution Model

3.3.1. Decision Variables

Conflicts among multiple airspaces mainly refer to the repeated occupation of the same spatiotemporal range by different airspace activities, as well as situations where the operations of multiple airspaces do not meet the safety separation minimums requirements. For each conflicting airspace , this paper introduces seven decision variables to describe the spatial and temporal adjustments and rejection strategy of the airspace:

where:

: denotes the adjustment of the three-dimensional spatial range during the conflict resolution process among multiple airspaces;

: represents the adjustment of the airspace start and end time window;

is a discrete variable indicating whether the airspace is rejected, where .

When , it indicates acceptance of the current strategy; otherwise, the strategy is rejected, and a globally optimal approach is considered to reduce conflict risk.

If there are airspaces in the conflict group , the overall decision variables are defined as:

3.3.2. Constraint Conditions

Since multi-airspace conflict resolution must not only satisfy the safety separation minimums within the spatiotemporal range for each airspace but also meet the actual airspace usage requirements of aircraft, the goal is to minimize resolution cost. Considering the locally complex multi-airspace conflict scenarios, the constraint conditions for conflict resolution mainly include the following two aspects:

Spatiotemporal Adjustment Constraint:

During the airspace adjustment process, adjustments are not unrestricted and must take into account both the usage requirements of each airspace and the feasibility of flight missions. This is particularly important in the context of airspace used for military operations, where close coordination between different airspaces is required. Proper adjustments should be made to avoid significant modifications that may reduce resource utilization. Therefore, this paper defines the maximum spatial adjustment threshold as and the maximum temporal adjustment threshold as .

Safety Separation minimums Constraint:

To ensure that the adjusted airspaces remain safe and usable after conflict resolution, any two adjusted airspaces must maintain a minimum safety separation. For the localized airspace sectors considered in this work, the three-dimensional Euclidean distance is employed, as it provides an accurate measure of separation while simplifying the model and improving computational efficiency. The constraint is expressed as follows:

where:

: denote the adjusted airspaces;

: represents the safety separation minimums distance required for airspace operations.

3.3.3. Objective Function

To ensure that the conflict resolution results for multiple airspaces are more scientific and reasonable, this study incorporates three optimization criteria into the construction of the objective function: spatiotemporal adjustment cost, rejection cost, and conflict penalty.

- Spatiotemporal Adjustment Cost. Adjustments in the spatiotemporal range of an airspace may result in additional path costs and energy consumption. To maintain the stability and reliability of the original airspace usage scheme as much as possible, this study assigns a priority level to each airspace. A higher priority indicates greater importance, thus the conflict resolution process should prioritize minimizing the amount of adjustment for high-priority airspaces. Here, the priority-based weight in cost calculation is normalized by a constant —set to the maximum priority level in the study (e.g., 3 in this research)—to ensure the importance factor is scaled to the range [0, 1], enabling consistent comparison of adjustment costs across airspaces with different priority levels. The spatiotemporal adjustment cost is expressed as:

To ensure consistent spatial and temporal dimensions, this study introduces characteristic scale factors and to nondimensionalize the displacement. is set to the maximum spatial adjustment limit within the current conflict cluster, while is set to the maximum temporal adjustment limit.

- where:

is the airspace importance factor, and Λ is a constant.

- 2.

- Rejection Cost. When an airspace has a high priority level or large scale, the overall impact of adjustments to that airspace should be comprehensively evaluated. To avoid arbitrarily rejecting applications from high-priority airspaces—especially for tasks such as emergency flights or rescue operations—a rejection cost is introduced. This cost incorporates two normalization parameters: (consistent with that in spatiotemporal adjustment cost) normalizes the priority weight to maintain consistency in priority-based cost scaling, while balances the influence of airspace volume on rejection decisions, preventing excessive dominance of large-volume airspaces in the evaluation. The rejection cost is expressed as:

where:

is the base rejection cost, is the airspace scale factor, and is a constant.

In this study, and are adopted to weight the adjustment cost and rejection cost, respectively. The former stems from empirical statistics indicating that high-priority airspace exhibits lower marginal delay costs, while the latter is based on large-sample regression results, which confirm that the relationship between volume and rejection probability follows a logarithmic rather than linear pattern.

- 3.

- Conflict Penalty. If conflicts still exist between airspaces after adjustments, it indicates that the current resolution strategy does not meet practical requirements. A penalty should therefore be imposed, and the conflict problem re-solved. This penalty term carries a high weight to ensure that the optimization process prioritizes conflict-free solutions, thereby enhancing the safety of the final resolution strategy. The penalty term is expressed as:

This equation imposes a penalty when any two adjusted airspaces still conflict.

In summary, multi-airspace conflict resolution is a multi-objective optimization problem. This study aims to minimize the adjustment cost, rejection cost, and conflict penalty. The objective function is expressed as:

where:

are the weights for spatiotemporal adjustment cost and rejection cost, respectively, and this paper sets ;

: denotes the conflict penalty coefficient.

4. Methodology

Based on the aforementioned gridding and resolution problem model, this section elaborates on the hierarchical conflict detection mechanism for multi-airspace and the conflict resolution strategy based on IWMA, laying a theoretical foundation for realizing the integrated multi-airspace conflict detection and resolution.

4.1. Hierarchical Conflict Detection Mechanism

Airspace conflict refers to the situation where multiple airspaces occupy the same spatiotemporal resource simultaneously or the distance between airspaces is less than the minimum safe separation. To effectively resolve conflicts in the process of airspace management, this study designs a hierarchical conflict detection mechanism including coarse screening and fine screening phases. Among them, the coarse screening phase is used to identify potential conflicts, which means reducing the global comparison to only checking airspace pairs sharing grids through grid indexing. The fine screening phase refers to performing precise geometric calculations on the potential conflicts passing through the coarse screening phase to determine the spatiotemporal relationship between specific airspaces and accurately identify conflicts in combination with the minimum safe separation. During the entire detection process, the grid information and spatiotemporal distribution of each airspace are taken as inputs, and the detection results are represented by conflict groups constructed with undirected graphs. The hierarchical detection mechanism significantly improves the efficiency of multi-airspace conflict detection.

4.1.1. Coarse Screening Phase

The coarse screening phase based on the octree spatial grid model filters most non-overlapping airspaces through shared grids to identify potential conflict pairs. Its essence is a set intersection operation, and there is no need to consider the issue of whether grid coding is continuous. As long as the grid sets of the airspaces to be detected have overlapping Morton codes, it indicates that the airspaces have spatial overlap. Due to the uniqueness of Morton codes and their support for fast hash retrieval, the intersections between airspace entities or between entities and buffer zones can all be efficiently implemented through set operations and hash table lookup, without the need to traverse all spatial points.

The coarse screening phase is based on grid intersection. By constructing reverse indexing from grids to airspaces and traversing the airspace usage status of each grid, potential conflicts are identified according to coincidence. For any two airspaces and , the expression for coarse screening detection is:

where:

and : represent the entity grid set and buffer grid set of the -th airspace;

and : denote the entity grid set and buffer grid set of the -th airspace.

If there is an intersection between the grid sets of the two airspaces, it is considered that a potential conflict exists between them; if there is no intersection, the conflict can be directly excluded.

4.1.2. Fine Screening Phase

The fine screening phase conducts precise geometric relationship-based and semantic accurate evaluation on each potential conflict group. It first performs comprehensive conflict determination within the horizontal, vertical, and temporal ranges, then conducts calculation based on the spatiotemporal overlap degree of the airspaces included in the conflict pair, and finally adopts the comprehensive conflict confidence level to reflect the severity of airspace conflicts. Among them, in the vertical and temporal conflict determination processes, the detection principle is consistent: the vertical and temporal objects to be detected are treated as one-dimensional line segments, and conflicts are determined by comparing the center distance with the sum of radii. Taking vertical detection as an example, its expression is:

where:

and represents the center point of the elevation of the two airspaces;

: the center distance of the elevation of the two airspaces is used to represent the vertical difference;

: denotes the minimum vertical safe separation.

If the inequality holds, a conflict exists; otherwise, no conflict exists.

Temporal dimension conflict detection is analogous to height dimension conflict detection, and its detection principle is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The principle of conflict detection in the temporal dimension.

To summarize, while completing conflict detection in the spatiotemporal range, it is also necessary to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the spatial overlap degree , temporal overlap degree , and vertical overlap degree to further reflect the severity of conflicts. On this basis, a weighted method is adopted to integrate the comprehensive conflict confidence level, and its expression is:

where , and denote the evaluation weights of conflict confidence levels for different dimensions, and . Through the weighted fusion of the aforementioned indicators, the final conflict confidence score is generated.

4.1.3. Construction of Conflict Groups

To convert the three-dimensional spatiotemporal coupling relationships of multiple airspaces in hierarchical conflict detection into a one-dimensional form, this study regards all detected airspace conflict pairs as conflict edges and defines an undirected graph . In the undirected graph , vertices represent the set of all airspaces, and the edge set consists of all airspace pairs with valid conflicts. Among them, any group of airspaces connected by direct or indirect conflict paths forms a connected component in the undirected graph, i.e., a conflict group. Through conflict groups, conflict clusters in a multi-conflict airspace environment can be quickly identified, thereby accurately reflecting multi-airspace conflict relationships.

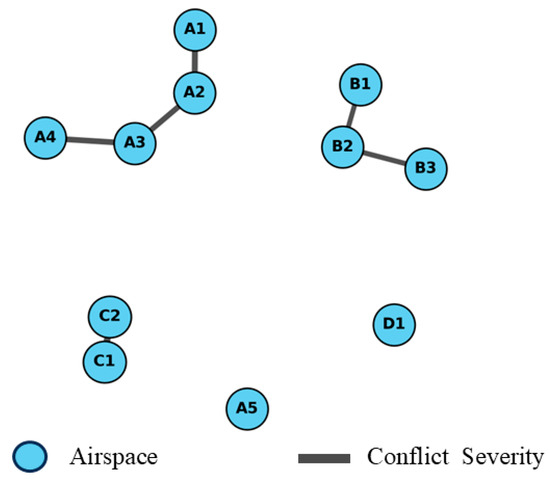

The graph theory method constructs a “vertex + edge” model based on conflict units and conflict relationships, converting complex conflict relationships into an intuitive graph structure. Then, all connected sets of conflict units (i.e., connected components) are found through traversal using the DFS algorithm [21], thus efficiently constructing conflict groups. As shown in Figure 5, this diagram illustrates the conflict dependency relationships between airspaces.

Figure 5.

Conflict-Group Undirected Graph.

4.2. Airspace Conflict Resolution Strategy

4.2.1. Basic Principle of WMA

WMA (Whale Migration Algorithm) is a novel swarm intelligence optimization algorithm that simulates the collective migration behavior of whale populations in the ocean based on a leader-follower mechanism [22]. The process of solving optimization problems with WMA is similar to other swarm intelligence algorithms: the whale population is mapped to a set of candidate solutions, where the position of each whale corresponds to a possible solution. The positions of the whale population are updated dynamically through a leader-follower strategy, iteratively searching for the optimal individual whale position. The mechanism of the algorithm is described as follows:

For a -dimensional search space, the whale population size is defined as . The initial whale population positions are simulated through population initialization, expressed as:

where represents the position of the -th whale, is a -dimensional random vector within the interval , and represent the range of whale migration behavior. denotes the Hadamard product.

During the position update process, the top whales with better performance are defined as leaders, and the rest as followers. Optimization is achieved through the coordinated movement of these two groups. To enhance the guiding capability of the leaders toward the followers, the average position of the leaders is used as the reference direction for group migration, expressed as:

where is the average position of the leaders.

In addition, leaders are responsible for global exploration in unknown regions to search for better migration paths, while followers follow by imitating nearby more experienced individuals and combining the directions of the average position and the best leader position. The position update formulas for leader exploration and follower movement are as follows:

where:

and are random vectors of the same dimension as , and simulates a global guiding signal analogous to a magnetic field. The dual-random term controlled by ensures that leaders can explore unvisited regions in the search space

is the position of a previously better-performing individual follower, and is the position of the best leader. The random term prevents complete replication, thereby maintaining population diversity during local exploitation.

In WMA, local exploitation is achieved by follower movement updates based on imitation and guidance mechanisms, while global exploration is achieved by leader movements combining random exploration and global guidance. Furthermore, during each iteration, the roles of leaders and followers are updated based on the current positions, allowing dynamic adjustment between exploration and exploitation.

4.2.2. Improved WMA

To address the exploration insufficiency of WMA when solving high-dimensional and complex problems, this study proposes an improved version of WMA. Building upon the original collaborative migration and leader-follower mechanism, a diversified population structure and elite-driven update strategy are designed to enhance both the diversity of the initial population and the global optimization capability. Moreover, during each iteration, the global optimum is used as a reference for migration, allowing progressive exploration of high-quality regions while maintaining population diversity, thus avoiding local optima and achieving a better balance between exploration and exploitation.

- 1.

- Diversity Initialization Strategy

The traditional WMA initializes whale populations randomly within the bounds of the search space. However, this randomness can lead to the initial population being clustered around a local optimum, resulting in premature convergence and reducing the likelihood of discovering a global optimum. Alternatively, the population may be concentrated in low-quality regions, which, although correctable through iteration, significantly reduces algorithmic efficiency. To address this, a stratified cost-based initialization strategy is proposed in this study. By layering the population based on cost, the initialization process controls diversity, avoids pitfalls of purely random distribution, and ensures sufficient coverage of the search space. The population is divided into three cost-based layers (from high to low), and the stratified initialization is expressed as:

where represents the cost layer from high to low; and denote, respectively, the upper and lower bounds of the search space; denotes the Hadamard product.

and denote the lower and upper boundary proportion coefficients of layer respectively. When approaches 0, whales in this layer tend to search near boundaries; when approaches 1, they retain a strong global search ability.

- 2.

- Multi-Strategy Collaborative Optimization

The elitist strategy adopted in this paper involves the use of a moderate exploitation strategy and an enhanced exploration strategy based on the quality and fitness of individuals. Specifically, a certain proportion of individuals are referred to as elite individuals, an equal proportion as worst individuals, and the remaining intermediate individuals as ordinary individuals. In the exploration phase, a differentiated individual optimization strategy is employed: for the worst individuals, a radical exploration strategy is used, which introduces the Lévy flight mechanism [23]. This mechanism enables the algorithm to escape from the current local optimal solution region through occasional large-step jumps, avoid becoming trapped in suboptimal solutions, cover a wider solution space, and increase the probability of finding the global optimum. Meanwhile, noise-guided directional exploration is applied to the worst individuals to make them stably evolve towards elite individuals. Secondly, a moderate exploitation strategy is used for elite individuals. The core of this strategy is to make minor adjustments to elite individuals with a linearly decaying step size to avoid drastic changes, guiding them towards the optimal solution. To maintain their diversity, small random perturbations are introduced.

For elite individuals, a moderate exploitation strategy is adopted, and its formula is:

where:

and are step size factors;

is the decay rate of the step size;

is the decay rate of perturbation. and control convergence speed;

is the initial perturbation strength.

For inferior individuals: an enhanced exploration strategy with the introduction of the Lévy mechanism is adopted, and its formula is:

where:

is the Lévy distribution exponent that controls jump heaviness, and ; smaller values facilitate escape from local optima, while larger values result in milder.

controls the exploration range;

is the decay factor of exploration intensity, and ;

denotes the Lévy-distributed random value, and .

For ordinary individuals, a balanced strategy with a probabilistic selection mechanism is adopted, i.e., exploration or exploitation is selected with a probability, and its formula is:

where:

Equation (27) is the exploration formula, denotes the exploration perturbation strength;

Equation (28) is the exploitation formula, is the exploitation step size factor, .

Through the proposed diversity initialization and multi-strategy collaborative optimization mechanisms, the IWMA not only avoids premature convergence to local optima but also significantly enhances the global search capability of the algorithm.

4.2.3. Application of the IWMA in Conflict Resolution

In summary, through the improvement of the WMA algorithm, it is capable of efficiently solving the conflict resolution problem across four dimensions: spatial translation, altitude adjustment, temporal shift, and airspace rejection. The algorithm balances conflict elimination and adjustment cost, ultimately producing an optimal solution that satisfies all constraints. The specific solution process of the improved WMA in multi-airspace conflict resolution is as follows:

Step 1: Conflict Preprocessing:

Input the conflict detection results and extract the conflict set, which includes pairs of conflicting airspaces, spatial and temporal overlap ratios. The severity of each conflict is calculated based on the overlap ratio to determine the priority for resolving multi-airspace conflicts.

Step 2: Problem Modeling:

Each group of conflicts is modeled independently. For each airspace, seven decision variables are defined to represent spatial and temporal adjustments and rejection parameters. An objective function is constructed to minimize adjustment cost, rejection cost, and conflict penalty. Additionally, the maximum adjustment bounds for spatiotemporal variables are set as and .

Step 3: Parameter Settings:

Set the whale population size to , the maximum number of iterations to , the search space dimension to , and define the upper and lower bounds of the search range.

Step 4: Population Initialization:

Each whale individual is treated as a set of conflict resolution parameters. The population is stratified based on solution quality: the top 30% are designated as elite individuals, the bottom 30% as poor individuals, and the remaining as ordinary individuals. The initial fitness of the population is calculated.

Step 5: Iterative Update Phase:

Based on the three quality tiers (elite, poor, ordinary), corresponding strategies are applied: mild exploitation for elite individuals, Lévy global jumps for poor individuals, and adaptive balancing for ordinary individuals. Whale positions are updated to simulate migration and local search. Constraint correction ensures the feasibility of resolution strategies, and the best historical position is updated. Upon termination, the optimal individual is output as the best resolution plan for the current conflict group.

Step 6: Output Results:

Decode the optimal individual into airspace adjustment values and rejection decisions, and output the multi-airspace resolution list and the overall resolution cost.

As illustrated in Figure 6, this simplified flowchart fully presents the entire workflow from grid subdivision to airspace conflict detection and then to conflict resolution in multi-airspace scenarios.

Figure 6.

Simplified Flowchart of Multi-Airspace Conflict Detection and Resolution.

5. Simulation Results and Analysis

To verify the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed multi-airspace conflict detection and resolution method based on the octree grid structure, two sets of experiments were designed. Experiment 1 validates the performance of the hierarchical detection mechanism, while Experiment 2 evaluates the conflict resolution results and algorithm performance based on the IWMA. The simulation environment is as follows: Windows 11, Python 3.12, Intel Core i5-13500H processor, base frequency 2.60 GHz.

5.1. Simulation Scenarios and Parameter Settings

To evaluate the performance of the proposed method in handling locally complex airspace conflicts, three synthetic airspace datasets with distinct scales (15, 30, and 60 airspaces) and varying complexities were constructed. Among these datasets, the detailed information of the 30-airspace dataset—encompassing 2D vertex coordinates, altitude ranges, time usage intervals, and priority levels—is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Airspace Data Parameters.

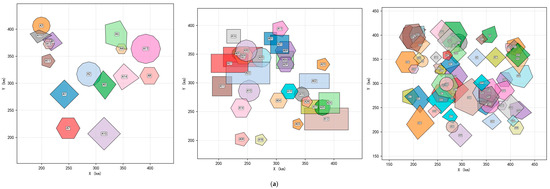

As shown in Figure 7, the spatial distributions of the aforementioned airspace dataset in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional spaces are illustrated. To reduce the complexity introduced by multi-level spatial grids and to enhance the distinguishability of airspaces within the space, only the outermost grid contours of each airspace are selected as the reference in the spatial distribution. This selection is independent of the actual conflict detection and resolution process.

Figure 7.

Spatial Distribution of the Airspace Dataset (a) 2D Spatial Distribution Chart; (b) 3D Spatial Distribution Chart.

In this paper, the relevant parameter settings for the multi-airspace conflict detection and resolution experiments are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The Parameter of The Multi-Airspace Conflict Detection and Resolution.

5.2. Detection Performance Analysis

To determine the optimal grid subdivision level, a sensitivity analysis experiment for grid levels was designed utilizing the three airspace datasets with distinct densities constructed earlier. Specifically, conflict detection was performed on each airspace dataset under varying grid subdivision levels, with the detection time and accuracy systematically recorded. This approach aims to identify the optimal trade-off between accuracy and efficiency, thereby demonstrating that the selection of grid subdivision levels is grounded in the trade-off of objective performance metrics. he experimental results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Performance Comparison of Different Subdivision Levels.

Experimental results indicate that the grid level directly determines the recall capability of conflict detection. In the scenario with an airspace scale of 30 (medium density), only 7 conflict groups were detected when the grid level was set to 5; after increasing the grid level to 6, the number of detected conflict groups increased to 22, and remained unchanged when further raised to levels 7 and 8. This indicates that for this specific scenario, the grid level of 6 has achieved or approached a saturated detection state, while level 5, due to the excessively large grid cell size, results in significant spatial discretization error, leading to severe missing detections. Furthermore, from the results of different grid levels for airspace scales of 15 and 60, it can be observed that in the method proposed in this paper, the selection of grid level is associated with the scale of airspace data.

Based on the experimental parameters defined above, conflict detection was performed for 30 airspaces using the proposed hierarchical detection mechanism. As shown in Figure 8, a total of 22 conflicts were detected throughout the conflict detection process, which can be observed from both the undirected graph of the conflict network relationships and the matrix diagram of conflict relationships. According to the results of temporal occupancy and altitude distribution, the conflicts occurring between 3500 s and 6000 s, as well as between 2000 m and 4000 m, are particularly severe. These conflicts involve high overlaps of multiple airspaces across different spatiotemporal dimensions, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness and reliability of the hierarchical detection mechanism in handling local high-density multi-airspace conflicts.

Figure 8.

Multi-Airspace Conflict Relationship Diagram (a) Conflict network topology: The darkness of the lines connecting airspaces indicates the severity of the conflict, with darker colors representing more severe conflicts; (b) Conflict relationship matrix: Each cell in the matrix represents the specific conflict relationship between two airspaces; (c) Altitude distribution: Different colors represent the distribution of different airspaces at various altitudes; (d) Time occupancy: Different colors indicate the active periods of different airspaces.

To further verify the proposed method in terms of detection efficiency and accuracy, a performance comparison between the hierarchical detection mechanism and the traditional brute-force method was conducted. The comparison results are shown in Table 5. In terms of overall detection accuracy, both the fine screening stage and the traditional method are capable of detecting actual conflicts, although the coarse screening stage may result in some false positives. However, in terms of detection time, the coarse screening stage demonstrates the highest efficiency, followed by the fine screening stage, while the traditional method performs the worst. Specifically, the detection time of the traditional method is four times that of the hierarchical detection mechanism. Since the traditional method employs an exhaustive pairwise comparison of airspaces, the number of detections increases rapidly as the number of airspaces grows—reaching dozens or even hundreds of times more than that of the hierarchical detection mechanism.

Table 5.

Comparison Results of Conflict Detection Experiments.

Simulation results indicate that the hierarchical detection mechanism significantly outperforms the traditional brute-force method in all performance metrics. The primary reason is that the coarse screening stage utilizes octree-based grid partitioning to rapidly filter potential conflict pairs, thereby reducing the computational complexity of brute-force search from to . Although false positives may arise due to the use of buffer grids, the subsequent fine screening stage performs precise geometric calculations on the potential conflicts to confirm actual conflicts and eliminate errors. Meanwhile, by constructing an undirected conflict graph between airspaces—where nodes represent airspaces and edges represent conflict relationships—the structure and clustering characteristics of complex conflict networks are effectively revealed. This provides strong support for rapid conflict identification and spatial-temporal distribution analysis.

5.3. Conflict Resolution Experiment

To fully validate the reliability of the proposed method for resolving multi-airspace conflicts, the 22 conflict pairs identified by the conflict detection strategy were ranked in descending order according to their severity. Subsequently, four algorithms IWMA, WMA, GA [24], and PSO [25]—were sequentially applied for conflict resolution, and their performances were compared in resolving these multi-airspace conflicts.

Figure 9 shows the convergence curves over 200 iterations for the four algorithms in handling the 22 conflict resolution cases. The blue, red, purple, and yellow lines represent the convergence trends of IWMA, WMA, GA, and PSO algorithms, respectively. A faster convergence speed and lower resolution cost indicate better algorithm performance. As observed from the convergence results, IWMA converges around the 23rd iteration, exhibiting the fastest convergence speed. While PSO achieves the lowest resolution cost, it stagnates between the 30th and 100th iterations, indicating that the algorithm may have fallen into a local optimum during the global search phase. Compared to WMA, IWMA demonstrates greater stability due to its multi-strategy collaborative optimization mechanism, which includes multi-population initialization and elite selection. In summary, IWMA outperforms the others both in performance and stability.

Figure 9.

Results of Convergence Curves for Four Algorithms.

As shown in Table 6, the detailed performance indicators of the four algorithms after 20 independent runs on the local multi-airspace conflict-resolution scenario are reported. In these experiments “successful resolution” is strictly defined as: all safety-separation constraints must be satisfied, spatial, temporal and altitude overlaps between any airspace pair must be completely eliminated, and no airspace mission may be rejected. The results reveal pronounced differences in success rates: IWMA achieves the best performance with 88% success, whereas WMA, GA and PSO obtain 62%, 51% and 47%, respectively. This demonstrates that IWMA possesses stronger robustness and solution validity in complex conflict situations. Regarding resolution time, IWMA again exhibits superior behavior, requiring only 1.75 s on average to solve a conflict instance—significantly faster than any competitor. This indicates that IWMA not only maintains a high success probability but also offers excellent real-time responsiveness, making it well suited to rapid decision-making in high-density airspace environments. In terms of total resolution cost, PSO attains the lowest value (32.28), implying that it can occasionally locate high-quality solutions; however, the algorithm suffers from heavy computational overhead, a lower success rate, and slow convergence, which limit its applicability in time-critical systems. By contrast, IWMA achieves a better trade-off among total cost, success rate and time efficiency, demonstrating superior overall performance and stability.

Table 6.

Comparison Results of Conflict Resolution Experiments.

In summary, the proposed IWMA method outperforms the comparative algorithms in success rate, time efficiency and overall stability, and is particularly appropriate for real-time resolution of densely coupled multi-airspace conflicts.

Based on the above simulation experiments, and in order to further comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed IWMA in airspace conflict resolution tasks, a set of evaluation parameters was designed to assess its effectiveness under different degrees of spatiotemporal overlap. The varying levels of overlap reflect the complexity of the current conflict set. This experiment quantifies the algorithm’s performance in controlling conflict overlap, thereby verifying its resolution capability across the spatial, temporal, and altitude dimensions.

The simulation results are illustrated in Figure 10, which shows the changes in overlap degree before and after conflict resolution for each conflict pair in the spatial, temporal, and altitude dimensions, along with the overall average resolution effect across all spatiotemporal dimensions. As seen from the results, the IWMA significantly reduces the overlap degree across all dimensions, with the overlap of nearly all conflict pairs reduced below 0.1, demonstrating the algorithm’s strong multi-dimensional conflict decoupling capability. In the comparative analysis of average overlap degrees, the spatial, temporal, and altitude overlap degrees were reduced by 89.94%, 89.98%, and 90.03%, respectively. These results indicate that the algorithm not only performs excellently for individual conflict instances but also exhibits strong overall resolution capability.

Figure 10.

Comparison Figure of Multi-Dimensional Overlap Degrees Before and After Conflict Resolution. (a) Comparison of Spatial Overlap Degree; (b) Comparison of Temporal Overlap Degree; (c) Comparison of Vertical Overlap Degree; (d) Comparison of Average Overlap Degree.

Considering the practical significance of airspace conflict resolution, the above performance indicators demonstrate that IWMA excels in handling highly coupled, multi-constrained airspace conflict problems, and can effectively support staggered scheduling of tasks, thereby enhancing airspace operational safety and improving resource utilization.

In summary, the IWMA proposed in this study demonstrates significantly superior performance in resolving local high-density airspace conflicts compared to the other three algorithms, particularly in terms of resolution speed. Moreover, the results remain consistently stable across multiple experimental runs, fully validating the effectiveness and reliability of the proposed algorithm.

6. Conclusions

To address the problem of conflict detection and resolution in locally high-density multi-airspace environments, we propose an integrated framework for efficient conflict detection and resolution based on spatial grid partitioning. This framework consists of a grid-based modeling approach, a hierarchical conflict detection mechanism, and a conflict resolution strategy based on IWMA.

- (1)

- To handle 3D spatial problems, an octree-based spatial partitioning scheme was adopted and combined with Morton coding to construct a representation system for discretized three-dimensional airspaces.

- (2)

- In the hierarchical conflict detection strategy, coarse and fine screening phases are used to conduct comprehensive analysis of the candidate airspaces. Compared to traditional detection methods, this approach enables rapid conflict identification while the undirected graph representation effectively captures and structures the conflict relationships.

- (3)

- In the conflict resolution module, we scientifically define the maximum adjustment thresholds in both spatial and temporal dimensions, referencing actual operational separation standards. Aiming to minimize the total resolution cost, we improve the traditional WMA algorithm by designing a diversity-enhanced initialization population and employing a multi-strategy optimization mechanism, effectively addressing the resolution challenges in high-density local multi-airspace scenarios.

The Simulation results confirm the effectiveness and reliability of the proposed method based on the octree grid structure. The hierarchical detection mechanism significantly improves detection efficiency, while the IWMA-based resolution approach demonstrates clear advantages in terms of convergence speed, solution quality, and algorithmic stability. Compared to traditional optimization algorithms, IWMA also shows stronger global search ability and a better capacity to escape local optima. This method is capable of effectively managing complex multi-airspace conflict scenarios and provides reliable technical support for practical airspace management applications.

Although the proposed method demonstrates strong performance in static multi-airspace conflict detection and resolution, it is subject to three principal limitations. First, the model rests on a static airspace-occupancy assumption; it neither accounts for aircraft kinematics and maneuver constraints nor incorporates time-varying environmental factors. Consequently, the approach is better suited to off-line planning and is ill-equipped for real-time, dynamic conflict management. Second, the present optimization framework omits external constraints such as meteorological conditions, terrain, and restricted zones, curtailing its applicability to complex, real-world airspace. Third, the high-resolution octree discretization coupled with multi-objective optimization incurs prohibitive computational cost over large-scale airspace, posing a critical bottleneck for time-critical applications.

To address these deficiencies and to meet the demands of future high-density, highly dynamic airspace operations, efficient dynamic airspace processing and real-time re-planning emerge as indispensable capabilities for autonomous airspace management. Our forthcoming research will therefore pursue the following directions:

- (1)

- Develop a dynamic airspace model that embeds kinematic and dynamic constraints, enabling trajectory-level conflict detection and resolution;

- (2)

- Construct an environmental modeling framework that fuses multi-source sensing data to enhance robustness in realistic scenarios;

- (3)

- Design real-time conflict-resolution and on-line re-planning algorithms founded on receding-horizon optimization and cooperative decision-making for rapid response; and

- (4)

- Explore distributed and parallel optimization architectures to scale computational efficiency to large-scale airspace, thereby satisfying the dual imperatives of safety and performance in future dynamic airspace systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L. and L.W.; methodology, Q.L. and L.W.; software, Q.L. and Y.Z.; validation, B.X. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, Q.L.; investigation, B.X.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L. and Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.W.; visualization, Q.L. and B.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IWMA | Improved Whale Migration Algorithm |

| CD&R | Conflict Detection and Resolution |

| DGGS | Discrete Global Grid System |

| HQBS | Hexagonal Quaternary Balanced Structure |

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

References

- Dai, W.; Pang, B.; Low, K.H. Conflict-free four-dimensional path planning for urban air mobility considering airspace occupancy. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 119, 107154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Romero, E.; Valenzuela, A.; Rivas, D. Probabilistic multi-aircraft conflict detection and resolution considering wind forecast uncertainty. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 105973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Zhou, J.; Ben, J.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; Ding, J.; Dai, J. Precise hexagonal pixel modeling and an easy-sharing storage scheme for remote sensing images based on discrete global grid system. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2328824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmoch, A.; Vasilyev, I.; Virro, H.; Uuemaa, E. Area and shape distortions in open-source discrete global grid systems. Big Earth Data 2022, 6, 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Ben, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pei, T. Efficient encoding and spatial operation scheme for aperture 4 hexagonal discrete global grid system. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 27, 898–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lei, Y.; Tong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Qiu, C.; Guo, C.; Sun, Y.; Lai, G. A Non-Rigid Hierarchical Discrete Grid Structure and Its Application to UAVs Conflict Detection and Path Planning. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2022, 58, 5393–5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbestan, J.J.; Senocak, I. Binarized-octree generation for Cartesian adaptive mesh refinement around immersed geometries. J. Comput. Phys. 2018, 368, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, T.; Li, X.; Ni, Y.; Li, Y.; Jin, Z. A Multiresolution Vector Data Compression Algorithm Based on Space Division. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Hu, M.; Su, F. Unmanned aerial vehicle conflict detection based on spatiotemporal data grid. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 2246, p. 012032. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, S.; Cheng, C.; Zhai, W.; Ren, F.; Zhang, B.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. A low-altitude flight conflict detection algorithm based on a multilevel grid spatiotemporal index. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K.; Zhao, G.; Wu, Y.; Tong, L. Research on Airspace Conflict Detection Method Based on Spherical Discrete Grid Representation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Wan, L.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, Z.; Xu, X. A Complex Network-Based Airspace Association Network Model and Its Characteristic Analysis. Symmetry 2022, 14, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Choi, B.; Lee, K.; Kim, Y. Conflict management considering a smooth transition of aircraft into adjacent airspace. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 17, 2490–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaek, S.M.B.; Golchoubian, M. Enhanced conflict resolution maneuvers for dense airspaces. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2020, 56, 3409–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Liu, D.; Liu, X.; He, F.; Ding, D. Study on aircraft generalized conflict resolution and trajectory optimization with multiple constraint in complex airspace environment. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/AIAA 38th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Diego, CA, USA, 8–12 September 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jenie, Y.I.; van Kampen, E.-J.; Ellerbroek, J.; Hoekstra, J.M. Safety assessment of a UAV CD&R system in high density airspace using Monte Carlo simulations. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 19, 2686–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, D.A.; Rashid, A.T. Three Dimensional Path Planning and Obstacle Avoidance: An Overview. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2020, 975, 8887. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.N.; Fan, Z.H.; Ding, D.Z.; Chen, R.S.; Leung, K.W. Preconditioned MDA-SVD-MLFMA for analysis of multi-scale problems. Appl. Comput. Electromagn. Soc. J. 2010, 25, 914–925. [Google Scholar]

- Guitart, A.; Delahaye, D.; Feron, E. An Accelerated Dual Fast Marching Tree Applied to Emergency Geometric Trajectory Generation. Aerospace 2022, 9, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavez, E.; Chou, P.A. Dynamic polygon cloud compression. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–9 March 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 2936–2940. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffler, R. On the recognition of search trees generated by BFS and DFS. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2022, 936, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Deriche, M.; Trojovský, P.; Mansor, Z.; Zare, M.; Trojovská, E.; Abualigah, L.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Mohammadi, S.K. An efficient bio-inspired algorithm based on humpback whale migration for constrained engineering optimization. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, J.; Hao, F.; Dai, M. A novel enhanced global exploration whale optimization algorithm based on Lévy flights and judgment mechanism for global continuous optimization problems. Eng. Comput. 2023, 39, 2433–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobey, A.J.; Grudniewski, P.A. Re-inspiring the genetic algorithm with multi-level selection theory: Multi-level selection genetic algorithm. Bioinspiration Biomim. 2018, 13, 056007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Huang, K.; Tan, Z.; Fang, M.; Huang, H. Multi-subswarm cooperative particle swarm optimization algorithm and its application. Inf. Sci. 2024, 677, 120887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.