Abstract

With the growing application of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in complex, stochastic environments, autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance represent critical technical challenges requiring urgent solutions. This study proposes an innovative deep reinforcement learning (DRL) framework that leverages multimodal perception through the fusion of LiDAR and depth camera data. A sophisticated multi-sensor data preprocessing mechanism is designed to extract multimodal features, significantly enhancing the UAV’s situational awareness and adaptability in intricate, stochastic environments. In the high-level decision-maker of the framework, to overcome the intrinsic limitation of low sample efficiency in DRL algorithms, this study introduces an advanced decision-making algorithm, Soft Actor-Critic with Prioritization (SAC-P), which markedly accelerates model convergence and enhances training stability through optimized sample selection and utilization strategies. Validated within a high-fidelity Robot Operating System (ROS) and Gazebo simulation environment, the proposed framework achieved a task success rate of 81.23% in comparative evaluations, surpassing all baseline methods. Notably, in generalization tests conducted in previously unseen and highly complex environments, it maintained a success rate of 72.08%, confirming its robust and efficient navigation and obstacle avoidance capabilities in complex, densely cluttered environments with stochastic obstacle distributions.

Keywords:

UAV; DRL; autonomous navigation; obstacle avoidance; LiDAR; depth camera; multi-sensor; ROS 1. Introduction

Advancements in edge computing and high-precision sensor technologies have significantly expanded the applications of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) across domains such as surveillance [1], reconnaissance [2,3], search and rescue [4], logistics [5], environmental monitoring [6]. The ability to achieve robust autonomous navigation and effective obstacle avoidance is pivotal to ensuring safe, efficient, and reliable UAV operations in complex environments.

Conventional approaches to unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) navigation and obstacle avoidance have demonstrated moderate efficacy in simple, static environments. For example, references [7,8] leveraged enhanced Rapidly exploring Random Tree (RRT) algorithms to facilitate UAV path planning, while references [9,10,11] utilized optimized A* algorithms for navigation and obstacle avoidance. Furthermore, bio-inspired heuristic methods, including genetic algorithms [12,13], ant colony optimization (ACO) [14], and particle swarm optimization (PSO) [15,16], have been applied to address rudimentary UAV navigation and obstacle avoidance tasks. Nevertheless, these traditional methodologies exhibit notable limitations, including heavy reliance on prior environmental knowledge, elevated computational complexity, constrained perceptual capabilities, absence of adaptive learning mechanisms, and cumulative errors stemming from modular designs. Collectively, these deficiencies substantially undermine the robustness and generalizability of such approaches in complex, unknown environments.

To overcome the constraints of conventional approaches in UAV autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance, learning-based algorithms have emerged as a promising solution for addressing challenges in complex environments. These algorithms leverage onboard sensors, such as monocular cameras, depth cameras, and LiDAR, to acquire environmental obstacle data [17], enabling autonomous obstacle avoidance through end-to-end decision-making frameworks. As outlined in [18], learning-based UAV navigation and obstacle avoidance algorithms are broadly classified into three categories: deep learning-based, reinforcement learning-based, and deep reinforcement learning (DRL)-based. Deep learning-based methods typically employ neural networks to process visual data from cameras, augmented by auxiliary sensors such as optical flow meters, to facilitate obstacle avoidance [19,20]. In contrast, reinforcement learning-based approaches rely on trial-and-error interactions with the environment, utilizing sensor inputs from LiDAR or cameras to inform decision-making networks, which generate optimal actions and refine strategies based on reward signals from environmental feedback [21,22]. By integrating the strengths of deep neural networks and reinforcement learning, DRL algorithms markedly enhance the UAV’s capability for autonomous navigation and robust obstacle avoidance in intricate environments [23,24].

Despite advancements, DRL-based UAV navigation and obstacle avoidance research continues to encounter significant challenges. Firstly, the majority of studies depend on a single sensor modality, such as monocular cameras [25,26,27], depth cameras [28], or LiDAR [29,30], for environmental perception. In complex real-world settings, however, monocular and depth cameras are constrained by lighting conditions and limited fields of view, while LiDAR suffers from data sparsity, hindering comprehensive environmental awareness [31]. Secondly, DRL algorithms typically exhibit low sample efficiency, resulting in protracted policy convergence and limited adaptability to unknown environments.

In summary, current research on DRL-based UAV navigation exhibits several notable limitations: (1) a predominant reliance on a single sensing modality, which inherently restricts perception capability; (2) performance evaluations that are largely confined to sparse or simplified obstacle settings, rather than dense, unstructured, and stochastic environments that more faithfully reflect real-world conditions; and (3) insufficient emphasis on enhancing sample efficiency to enable faster and more adaptive policy learning. These constraints collectively impede the practical scalability and deployment of UAV navigation systems, where robust perception and efficient decision-making are paramount.

In addition, some existing integrated UAV system architectures have also explored similar directions. For example, ref. [32] combines intelligent onboard computing, multi-sensor cooperative perception, and efficient communication protocols to enhance UAV autonomy and mission performance. Therefore, to address the aforementioned limitations, this study proposes an innovative framework for UAV autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance, leveraging the fusion of depth cameras and LiDAR to substantially enhance environmental perception in complex settings. An efficient data preprocessing mechanism is developed to extract robust features from multimodal sensor data, thereby strengthening the representation of environmental states. Furthermore, we introduce a novel deep reinforcement learning algorithm, termed SAC-P, which integrates the Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) [33,34] framework with Prioritized Experience Replay (PER) [35]. By optimizing sample selection strategies, SAC-P markedly improves sample efficiency and elevates the overall performance of UAV navigation and obstacle avoidance. Simulation experiments validate that the proposed framework significantly enhances both sample efficiency and obstacle avoidance capabilities, with superior performance in densely cluttered environments featuring randomly distributed obstacles. The SAC-P-based high-level decision-making module demonstrates exceptional generalization and scalability across diverse scenarios, surpassing baseline algorithms. The primary contributions of this study are outlined as follows:

(1) A novel deep reinforcement learning (DRL)-driven framework for UAV autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance is proposed. In this framework, a DRL algorithm is introduced into the high-level decision-making module as the core decision mechanism, while LiDAR and depth camera data are fused to achieve multimodal environmental perception. Considering the characteristics of different sensor data, a dedicated data preprocessing mechanism is designed to effectively extract multisource features, thereby significantly enhancing the UAV’s perception robustness and obstacle avoidance performance in complex and stochastic environments.

(2) An efficient decision algorithm, SAC-P, is designed for the high-level decision-maker of the proposed framework. The algorithm combines the SAC method with the PER mechanism to optimize the sample selection strategy. The experimental results show that SAC-P not only significantly improves the sample utilization efficiency and model convergence speed, reduces the training time cost, but also shows better performance in UAV autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance tasks.

(3) Comprehensive experimental validation was performed within a high-fidelity simulation environment leveraging ROS and Gazebo. The results confirm that the proposed multi-sensor fusion deep reinforcement learning framework delivers superior generalization and adaptability, efficiently executing autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance tasks in complex, densely cluttered environments with randomly distributed obstacles, achieving performance that markedly outperforms baseline approaches.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines the foundational models of DRL and the methodology for constructing the UAV motion model. Section 3 provides a detailed exposition of the SAC-P algorithm’s principles and implementation specifics, alongside a comprehensive description of the architecture for the DRL-based UAV autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance framework, integrating LiDAR and depth camera perception. Section 4 presents the results of simulation experiments conducted with the proposed framework, accompanied by a thorough analysis and discussion. Section 5 concludes with a summary of the primary contributions and delineates avenues for future research.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Partially Observable Markov Decision Process

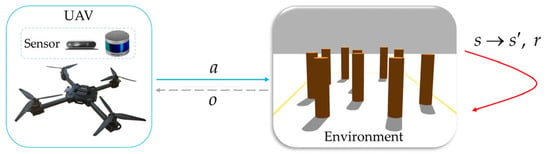

In real-world unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance tasks, the limited operational range of onboard depth camera and LiDAR sensors restricts the UAV to perceiving only partial environmental states. Consequently, as shown in Figure 1, the interaction between the UAV and the environment can be modeled as a partially observable Markov decision process (POMDP) [36]. POMDP is a mathematical model used to describe the control decision process of an intelligent agent system in a partially observable environment, which can be represented as a tuple:

where

denotes the state space of the environment, with the environment state at each time step

represented as

. Similarly,

denotes the action space of the agent, with the action executed by the agent at each time step

represented as

. Furthermore,

is the state transition probability function, representing the probability of transitioning from state

to the next state

after executing action

, thus it can be expressed as

. Additionally,

is the reward function, representing the immediate reward obtained by the agent for executing action

in state

. Moreover,

indicates the observation space of the agent, with the partial observation received by the agent from the environment at each time step

represented as

. Finally,

is the discount facto, which balances the significance of immediate versus future rewards.

Figure 1.

POMDP model.

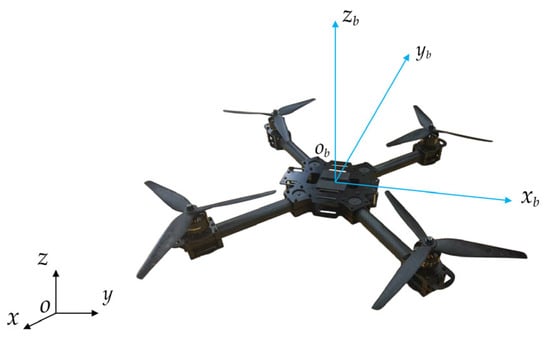

2.2. Motion Model of UAV

This study employs a quadrotor UAV as the experimental platform. To facilitate subsequent modeling, this study establishes a world coordinate system

and a UAV body coordinate system

, as depicted in Figure 2. The world coordinate system is defined using the East-North-Up (ENU) convention, while the body coordinate system adopts the Front-Left-Up (FLU) convention, with

,

and

corresponding to the UAV’s forward, left, and upward directions, respectively.

Figure 2.

Coordinate system.

Typically, the control architecture for quadrotor UAVs comprises low-level and high-level control. The low-level control, managed by the flight controller, primarily governs the UAV’s attitude stabilization. In contrast, the high-level control, executed by the onboard computer, focuses on integrating and processing data from various sensors and making advanced decisions using corresponding decision-making algorithms.

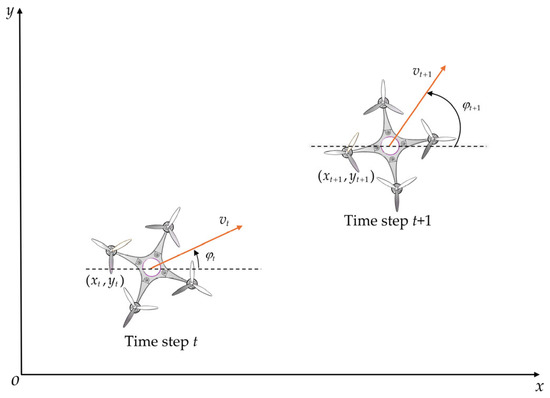

The motion of an UAV in three-dimensional space is characterized by six degrees of freedom. For simplicity, this study assumes that the UAV maintains a constant altitude during autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance. Therefore, this study establishes the UAV motion model in a two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system, as shown in Figure 3, with the specific model described as follows:

Figure 3.

Motion model of UAV.

In the formulation,

denotes the UAV’s linear velocity along its heading at time step

,

represents the yaw angle, defined as the angle between the body coordinate axis

and the world coordinate axis

, with counterclockwise rotation about the body coordinate axis

defined as positive,

denotes the yaw angular velocity,

represents the linear acceleration along the heading,

indicates the global position of the UAV’s center of mass in the world coordinate system, and

signifies the time interval between consecutive time steps.

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Formulation

In this section, the UAV autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance task is formulated as a POMDP model. The UAV achieves end-to-end decision-making by integrating environmental data acquired from its onboard depth camera and LiDAR sensors to effectively avoid obstacles. Furthermore, it is assumed that the UAV can accurately acquire its pose information using onboard GPS and IMU sensors, and the target position information is known.

3.1.1. Observation Space

In the actual task process, a UAV needs to decide which action to take to maximize the reward according to the current observation state. Therefore, this paper defines the observation space as follows:

In the formulation,

denotes the stacked depth image data, comprising four consecutive frames, acquired from the UAV’s onboard binocular depth camera at time step

, Similarly,

represents a 128-dimensional vector derived through down-sampling of the LiDAR sensor data. Additionally,

is a vector encapsulating relative information regarding the target position and the UAV’s own state (

).

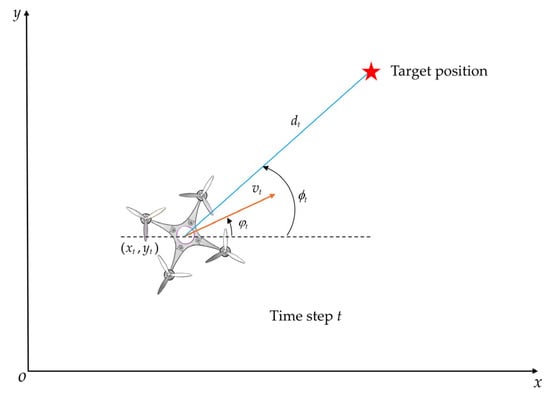

As illustrated in Figure 4,

denotes the Euclidean distance between the UAV and the target position at time step

. The term

represents the angular deviation, defined as

, where

is the angle between the line connecting the UAV’s center of mass to the target position and the world coordinate axis

, and

is the UAV’s current yaw angle. Additionally,

and

denote the sine and cosine of the deviation angle, respectively.

Figure 4.

The relative position relationship between UAV and target position.

3.1.2. Action Space

This study focusses on the design of the high-level controller for the UAV, while the low-level control is implemented by the flight controller onboard the UAV. Typically, such flight controllers support various control modes, including position control, velocity control, and angular velocity control. Based on the UAV motion model presented in Equation (2), and accounting for the continuity of velocity variations, this study employs the linear velocity along the heading and the yaw angular velocity as control inputs to the low-level controller to achieve precise motion control of the UAV. Therefore, the action space of the UAV is defined as follows:

3.1.3. Reword Function

In deep reinforcement learning, the design of the reward function plays a pivotal role in determining task performance. For the UAV autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance task, this study designs a reward mechanism to encourage the UAV to move toward the target position while introducing a penalty function for erroneous action selections to optimize the control policy.

(1) The motion distance reward, defined as the reward based on the difference in distance () between the UAV and the target point from the previous time step to the current time step:

where

denotes the weighting coefficient for the motion distance reward.

(2) The forward motion reward, designed to incentivize the UAV to progress along its heading while discouraging excessive backward motion:

where

denotes the weighting coefficient for the forward motion reward.

(3) The heading alignment reward, designed to incentivize the UAV to adjust its heading to facilitate progress toward the target position:

where

is the heading deviation reward coefficient.

(4) The smoothness action reward, aimed at preventing abrupt changes in UAV actions, thereby ensuring the smoothness of the motion process:

where

denotes the weighting coefficient for the action smoothness reward, and

represents the difference between the actions at the current and previous time steps.

(5) The task completion reward, awarded as a substantial positive reward when the UAV successfully avoids obstacles and reaches the target position:

where

denotes the coefficient of reward for task completion.

(6) The collision penalty, imposed as a substantial negative reward when the UAV collides with an obstacle:

where

denotes the minimum obstacle distance detected by the LiDAR at time step

, while

and

represent the predefined minimum collision distance and pre-collision distance, respectively,

is the coefficient of collision penalty.

(7) The out-of-bounds penalty, imposed as a substantial negative reward when the UAV moves beyond the predefined task boundaries:

where

denotes the out-of-bound penalty coefficient.

(8) The task failure penalty, designed to deter the UAV from exhibiting suboptimal behaviors such as remaining stationary or moving within a limited range, imposes a substantial negative reward when the UAV reaches the maximum time step without colliding or exceeding boundaries:

where

denotes the penalty coefficient of task failure.

(9) The time penalty, designed to decrease as the UAV completes the task in less time, imposes a smaller negative reward for faster task completion:

where

denotes the negative coefficient for the time penalty.

Based on the foregoing, the composite reward function for the UAV during the entire task is defined as follows:

3.2. UAV High-Level Decision-Making Algorithm

In this section, we present a detailed exposition of the high-level decision-making algorithm employed for autonomous UAV navigation and obstacle avoidance in this study. Given the continuous nature of the UAV’s motion dynamics and the requirement for real-time processing of multi-sensor fusion data, we adopt the SAC algorithm for high-level decision-making. To enhance the convergence rate of the SAC algorithm, we incorporate the PER method.

3.2.1. Soft Actor-Critic

The SAC algorithm is a state-of-the-art off-policy DRL method that leverages maximum entropy principles to achieve robust and sample-efficient policy optimization [33,34]. It is particularly well-suited for continuous control tasks. By balancing exploration and exploitation through entropy regularization, SAC ensures stable learning and adaptability in complex environments.

It operates within the maximum entropy reinforcement learning framework, augmenting the standard objective of maximizing expected cumulative rewards with an entropy regularization term. The objective is formalized as:

where

denotes the policy,

is the reward function,

is the discount factor,

represents the entropy of the policy at state

, and

is the temperature parameter balancing reward maximization and policy randomness.

The soft value functions are defined as follows. The state-action value function (Q-function) is:

where the state value function

incorporates the entropy term:

The optimal policy

maximizes the expected Q-value minus the entropy penalty:

To parameterize the policy, SAC employs a Gaussian distribution,

, where

denotes the policy network parameters. Actions are sampled using the reparameterization trick,

with

, enabling efficient gradient computation. The policy is optimized via the policy gradient:

where

is the replay buffer storing past experiences.

For the critic, SAC employs two Q-networks,

and

, to mitigate overestimation bias. The Q-function is optimized by minimizing the soft Bellman residual:

where

are target Q-networks updated via exponential moving average (EMA) to stabilize training.

The temperature parameter

is adaptively tuned to ensure the policy’s entropy approximates a target entropy

. The objective for

is:

3.2.2. Prioritized Experience Replay

PER is an advanced sampling strategy for reinforcement learning that enhances sample efficiency by prioritizing experiences based on their learning utility [35]. Unlike uniform sampling in traditional experience replay, PER assigns higher sampling probabilities to transitions that are deemed more informative, typically measured by their temporal-difference (TD) error.

(1) Priority Assignment. In PER, the priority of a transition

, denoted

, is typically derived from its TD error, which quantifies the discrepancy between the predicted and target values in value-based reinforcement learning methods. For a transition

, the TD error is defined as:

where

is the Q-value estimated by the current Q-network, and

is the target Q-value computed using a target network. The priority is then defined as:

where

is a small constant ensuring non-zero priorities for transitions with zero TD error, thus preventing sampling starvation.

(2) Sampling Probability. To prioritize informative transitions, PER employs a non-uniform sampling distribution where the probability of sampling transition

, denoted

, is proportional to a transformed priority:

where

is a hyperparameter controlling the degree of prioritization. When

, sampling reduces to uniform random sampling, while

results in fully prioritized sampling proportional to the priorities. Typically,

is chosen to balance prioritization and exploration. Efficient sampling is achieved using a SumTree (Based on proportional priority) data structure, where leaf nodes store the priorities

, and internal nodes maintain the cumulative sums of their children’s priorities, enabling

sampling complexity for a buffer of size

.

(3) Importance Sampling Correction. Non-uniform sampling introduces bias in the expected gradient updates, as the sampling distribution deviates from the underlying data distribution. To correct this, PER employs importance sampling weights, defined as:

where

is the number of transitions in the replay buffer, and

is a hyperparameter controlling the degree of bias correction. When

, no correction is applied, while

fully compensates for the sampling bias. In practice,

is often annealed from a small value to 1 over training to ensure stability early on. The weights are applied to the loss function, typically the squared TD error:

where

is normalized by the maximum weight in the mini-batch,

, to prevent gradient explosion and ensure numerical stability.

(4) Priority Updates. After each gradient update, the TD error of sampled transitions is recomputed to reflect changes in the Q-network. The updated TD error

is used to revise the priority:

The SumTree is subsequently updated to maintain the correct priority distribution, ensuring that subsequent samplings reflect the latest learning dynamics.

3.2.3. SAC-P

This study designates the integrated algorithm as SAC-P. In contrast to the original SAC algorithm, the Q-network update incorporates importance sampling weights

, with the loss function defined as follows:

After each update, priorities are recomputed using the updated TD error and stored in the SumTree to reflect the current learning dynamics.

The complete SAC-P algorithm is described in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: SAC-P | |

| 1 | Initialize policy network |

| 2 | Initialize Q-networks , , and target Q-networks , |

| 3 | Initialize replay buffer with a SumTree, PER hyperparameter and |

| 4 | Initialize temperature , soft update factor |

| 5 | Initialize the environment to obtain the initial state |

| 6 | for to Total timesteps do |

| 7 | execute action , obtain , and termination |

| 8 | store transition in with priority |

| 9 | if is greater than Time steps to start learning then |

| 10 | extracting Minibatch samples from |

| 11 | update Q-networks by minimize Equation (28) |

| 12 | if is divisible by Policy update frequency then |

| 13 | update policy network by minimize Equation (19) |

| 14 | end if |

| 15 | update minimize by Equation (21) |

| 16 | if is divisible by Target network update frequency then |

| 17 | update target Q-networks by for |

| 18 | end if |

| 19 | update priorities by Equation (27) and refresh the SumTree |

| 20 | if termination is true then |

| 21 | reset environment, |

| 22 | end if |

| 23 | end for |

3.3. System Framework

This subsection presents a detailed exposition of the framework for the UAV DRL lidar-vision navigation system developed in this study. It encompasses the convolutional neural network (CNN) encoder for preprocessing acquired depth images, the preprocessing of additional observations, and the operational principles of the overall system.

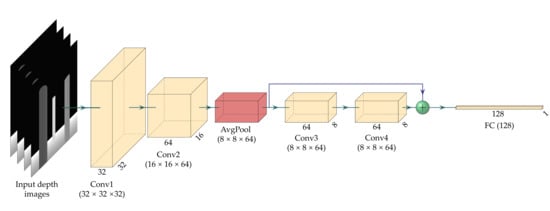

3.3.1. CNN Encoder

Directly utilizing raw depth images from the depth camera as the observation state input for the policy network substantially increases its learning complexity. To mitigate this, we propose a CNN encoder to preprocess the depth image data, extracting essential features and incorporating them as part of the observation state for the policy network. This approach significantly reduces the learning complexity of the policy network. The architecture of the proposed CNN encoder, illustrated in Figure 5, comprises four convolutional layers, ReLU activation functions, average pooling layers, and residual connections. To address the limited field of view of the depth camera, we reshape a sequence of four consecutive depth image frames into 64 × 64 pixels images prior to encoding. The preprocessed depth images are sequentially processed through the network layers. The first and second layers employ 4 × 3 convolution kernels (stride 2, padding (2,1)), progressively reducing the spatial resolution from 64 × 64 to 16 × 16, and further to 8 × 8 via 2 × 2 average pooling, while increasing the feature channels from 4 to 64 to capture multi-scale spatial features. The third and fourth layers form a residual block with 3 × 3 convolution kernels (stride 1, padding 1), preserving the 8 × 8 × 64 spatial dimensions, leveraging residual connections to enhance feature representation and alleviate the vanishing gradient problem. Finally, the flattened feature vector is mapped to a 128-dimensional representation through a fully connected layer, integrated into the observation state for the policy network.

Figure 5.

Network structure of the CNN encoder.

3.3.2. Preprocessing of Additional Observation Data

In contrast to the intricate preprocessing required for depth image data, the preprocessing of other data in the observation space is comparatively straightforward and efficient. We propose a unified feature extraction framework wherein down-sampled lidar data is processed through a fully connected layer to extract essential features, mapping them to a 128-dimensional representation that forms part of the observation state for the policy network. Similarly, relative target position information and UAV state data are fused and processed through another fully connected layer, yielding a 128-dimensional feature representation, which is also incorporated into the observation state.

This approach ensures standardized processing and efficient fusion of multimodal observation data, enabling the policy network to effectively leverage features from diverse data sources, thereby enhancing learning performance.

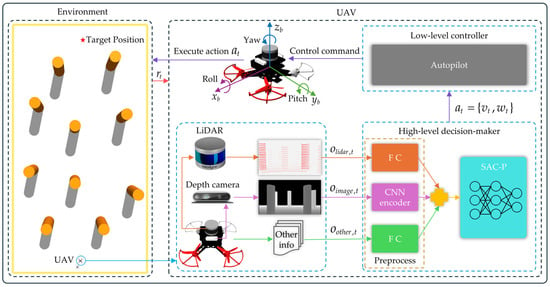

3.3.3. System Framework and Working Principle

Figure 6 illustrates the proposed system framework for autonomous UAV navigation and obstacle avoidance via DRL with fused LiDAR and depth camera information. Within this architecture, the UAV acquires real-time environmental state information through its integrated sensor suite: the onboard LiDAR and depth camera furnish spatial distribution information of obstacles, while the IMU and GPS sensors synchronously capture its own pose information. Based on these inputs, the relative target position information is calculated. These multidimensional sensory information streams are processed by dedicated preprocessing modules within the high-level decision-maker. Subsequently, the high-level decision-maker employs the preprocessed fused information to generate optimal action decisions using the SAC-P algorithm. These movement commands are then translated into actuation signals for individual execution units by the low-level controller, ultimately enabling autonomous obstacle evasion and precise waypoint navigation in unknown environments.

Figure 6.

System framework.

4. Experiments and Analysis

4.1. Experiment Setting

To facilitate joint simulation experiments for the UAV, this study leverages the Ubuntu 20.04 operating system, integrating the Robot Operating System (ROS) and Gazebo platforms for comprehensive simulation. ROS manages UAV flight control, while Gazebo provides a high-fidelity 3D simulation environment to replicate realistic physical interactions and stochastic scenes. This study adopts an open-source UAV simulator provided by Zhefan Xu [37] as the experimental platform. For sensor integration, we employ the D435 binocular depth camera and the Velodyne VLP-16 3D lidar, with detailed specifications outlined in Table 1. The hardware equipment specifications used in the experiments are detailed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Sensor parameters.

Table 2.

Hardware equipment.

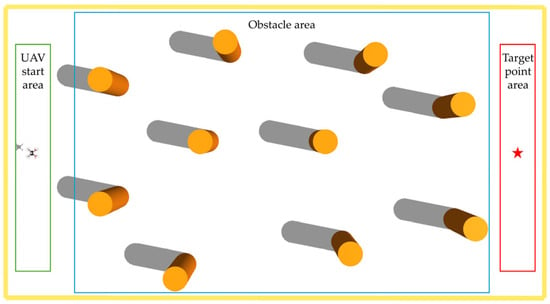

4.1.1. Scenario Setting

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed system framework in this study during task execution, a task area of 24 × 13 × 15 m was constructed in the Gazebo simulation environment, as shown in Figure 7. Obstacles are randomly distributed within the Obstacle subregion, with the UAV’s starting and target positions randomly initialized on the left and right sides of this subregion, respectively. A task is deemed unsuccessful if the UAV collides with an obstacle, exits the task boundaries, or exceeds the maximum time step. The overall simulation effect is shown in Figure 8. This experimental design enables a systematic evaluation of the navigation system’s robustness and effectiveness in partially observable environments.

Figure 7.

Simulation environment.

Figure 8.

The overall simulation effect.

4.1.2. Baseline and State Normalization

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed SAC-P algorithm, this study selected several state-of-the-art DRL algorithms as baselines for the high-level decision-making module, including Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) [38], Twin Delayed DDPG (TD3) [39], Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) [40], and SAC. Notably, DDPG, TD3, and SAC are off-policy algorithms, whereas PPO is an on-policy algorithm. All the aforementioned baseline methods were evaluated within our proposed framework, employing an identical data preprocessing pipeline and the same sensor configuration. In addition, to compare performance with that of frameworks based on traditional algorithms, the APF [41] and DWA [42] algorithms were selected as baselines in this study.

To expedite policy learning and improve training stability, we normalize all observation states to ensure consistent numerical ranges. Specifically, depth image data

, lidar data

, and the distance to the target

are processed using a standardized normalization formula:

where

and

are the predetermined minimum and maximum values for each data type, derived from hardware specifications or experimental analysis.

For the heading deviation states

and

, which are naturally bounded within

, no further normalization is necessary. Moreover, the action space is defined with a maximum value of 1, such that the UAV’s linear velocity

and yaw rate

require no additional normalization.

4.1.3. Basic Parameter Settings

Following extensive testing and validation, the experimental parameter settings for this study are detailed in Table 3. Specifically, the maximum number of time steps per episode is set to

, the time interval between consecutive steps is

, and the reward function weights are configured as follows: movement distance

, forward movement

, heading deviation

, and action smoothness

. Additionally, the minimum collision distance

m, the target proximity threshold is

m, and the time penalty weight is

. The UAV’s maximum linear velocity is

m/s, and the maximum angular velocity is

rad/s.

Table 3.

Basic parameters.

4.2. Training

This study employs PyTorch 2.4.1 with CUDA 12.2 as the training framework. The hyperparameters for algorithm training are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hyperparameters of Algorithm Training.

In addition to the above hyperparameters, three different random seeds were used in this study to ensure the reliability of the results. At the initiation of each episode, obstacles were randomly distributed within predefined subregions to simulate diverse environmental conditions. The backbone architecture for the Actor and Critic networks across all evaluated algorithms consisted of a multilayer perceptron (MLP) with two hidden layers, each containing 256 units.

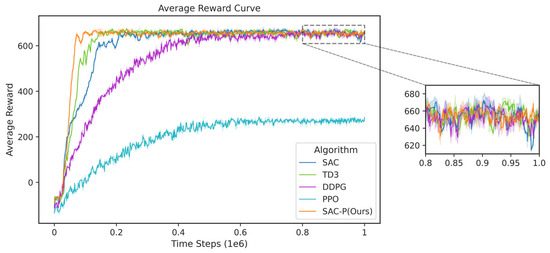

During the training phase, a fixed-size sliding window was utilized to compute the mean episodic reward, thereby enabling the analysis of reward trends over a specified temporal horizon. Figure 9 presents the average reward curves for all algorithms after training for 1 × 106 time steps, with shaded regions indicating the standard deviation derived from the three random seeds, thereby providing a measure of result variability.

Figure 9.

Average reward curve.

As illustrated in Figure 9, the proposed SAC-P algorithm achieves convergence at approximately 0.16 × 106 time steps, significantly outperforming the baseline algorithms. Specifically, TD3, SAC, DDPG, and PPO converge at approximately 0.20 × 106, 0.25 × 106, 0.50 × 106, and 0.60 × 106 time steps, respectively. These results underscore the superior convergence speed of the SAC-P algorithm. Furthermore, the experimental outcomes demonstrate that the optimized sampling strategy employed by SAC-P substantially enhances sample efficiency, yielding marked performance improvements over the baseline algorithms.

4.3. Testing

4.3.1. Performance Metrics

To evaluate the performance of the proposed SAC-P algorithm, we quantify its effectiveness using a comprehensive set of metrics: success rate, collision rate, out-of-bounds rate, timeout rate, step count, and flight distance.

(1) Success Rate (SR): The percentage of episodes in which the UAV successfully reaches the target position.

(2) Collision Rate (CR): The percentage of episodes where the UAV collides with an obstacle.

(3) Out-of-bound Rate (OR): The percentage of times the drone flies out of the mission area.

(4) Timeout Rate (TR): The percentage of episodes where the UAV fails to reach the target within the maximum time steps.

(5) Average Time Steps (ATS): The average number of steps required for the UAV to reach the target position from the starting position when the mission is successfully completed. In addition, since the energy consumed by the UAV during a mission is generally positively correlated with the number of time steps required, this study also considers the ATS as an indirect metric for evaluating the UAV’s energy consumption.

4.3.2. Comparative Testing

To enable an objective evaluation of the framework’s performance across different algorithms, we designed the experiments using the controlled variable approach, thereby ensuring both fairness and consistency in testing conditions. In this setup, all algorithms are implemented within the same proposed framework, with the only variation being the decision-making algorithm; consequently, the data preprocessing procedure remains identical for all cases. Moreover, performance assessments are conducted under an identical obstacle distribution, where the obstacle coordinates are fixed at [[4.0, 4.0], [7.5, 2.0], [−4.0, −5.0], [2.0, 0.5], [−7.0, 3.0], [3.0, −4.0], [−3.0, 0.5], [−2.0, 4.5], [−7.0, −2.0], [8.0, −3.0]]. The UAV’s starting positions are set to three representative points: [−11.0, 0.0], [−11.0, 4.0], [−11.0, −4.0], with corresponding target positions at [11.0, 0.0], [11.0, −4.0], [11.0, 4.0]. Each start-target pair undergoes 100 independent trials, resulting in a total of 300 episodes. In addition, each experiment was independently repeated three times with different random seeds.

- Comparison test with DRL baseline algorithms

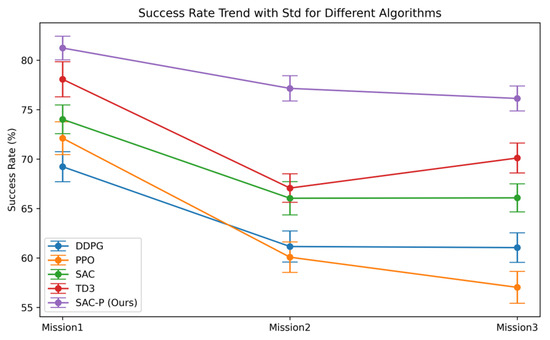

Using the trained model, we first benchmarked our approach against representative DRL baselines in three distinct mission scenarios. Performance was evaluated using five metrics: SR, CR, OR, TR and ATS. Overall statistics are summarized in Table 5 (results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD)), with comparative SR performance illustrated in Figure 10. The low SD values—generally below ±2% for rate-based metrics and ±0.5 time steps for ATS—demonstrate that the performance differences are statistically stable and not caused by stochastic variations inherent to DRL training or UAV simulation environments.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of cross-scene methods (with DRL baseline).

Figure 10.

The success rate of different algorithms for each mission (with DRL baseline).

In Mission 1, the SAC-P-based framework achieved the highest performance across all metrics (SR = 81.23 ± 1.20%, CR = 15.02 ± 1.01%, OR = 1.02 ± 0.40%, TR = 3.01 ± 0.49%, ATS = 61.26 ± 0.35), outperforming the strongest baseline TD3 (SR = 78.07 ± 1.78%) by approximately 3.16 percentage points. Notably, SAC-P required the fewest time steps, completing missions ~1.59 steps faster than DDPG, while maintaining low collision and failure rates. The small SD values (<±1.3%) indicate that these improvements were consistently observed across all trial runs.

Mission 2 results further validated the robustness of SAC-P. Its maintained superiority with an SR of 77.15 ± 1.28%, exceeding TD3 by ~10 percentage points. CR dropped to 18.04 ± 1.02%, a relative reduction of 16.08 and 19.14 percentage points compared with DDPG (34.12 ± 1.48%) and PPO (37.18 ± 1.59%), respectively. Although OR (2.01 ± 0.48%) and TR (3.05 ± 0.41%) were slightly higher than PPO’s values, they remained negligible in operational terms. SAC-P achieved the shortest ATS (66.33 ± 0.42), highlighting its navigation efficiency and path-planning robustness. Low SD values again support the reproducibility of these gains.

In Mission 3, SAC-P achieved SR = 76.13 ± 1.26%, maintaining a 6.02 percentage point margin over TD3. It recorded the lowest CR (17.07 ± 1.03%), dramatically outperforming PPO (38.07 ± 1.54%) and DDPG (32.10 ± 1.37%). Although OR (2.02 ± 0.47%) and TR (5.04 ± 0.48%) were marginally higher than PPO in certain scenarios, they remained within acceptable limits for safe UAV navigation. SAC-P again required the fewest average steps (66.22 ± 0.40). The consistently small SD values confirm that performance differences were not due to random instability.

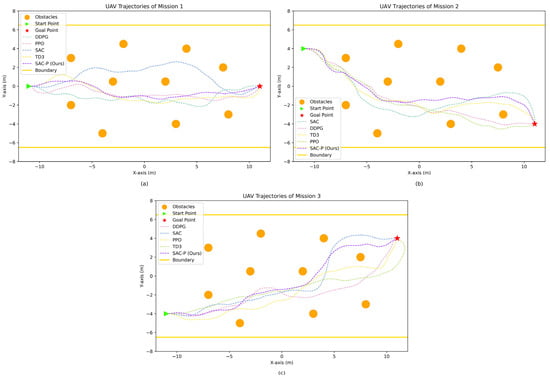

Taken together, results from all three missions demonstrate that the SAC-P framework consistently attains the dual advantage of the highest SR and shortest ATS. The statistical stability, as evidenced by small standard deviations across three independent runs, underscores the robustness and reproducibility of SAC-P in UAV autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance tasks. Algorithmically, SAC-P preserves exploratory behavior while achieving more stable learning of environmental dynamics, enabling a favorable balance between success rate and collision avoidance. The comparison of the UAV trajectories of the proposed method with the baselines of different DRL algorithms in each task is shown in Figure 11a, Figure 11b and Figure 11c, respectively.

Figure 11.

The UAV’s motion trajectories in each task (with DRL baseline): (a) mission 1; (b) mission 2; (c) mission 3.

- 2.

- Comparative test with the baseline of Non-DRL algorithm

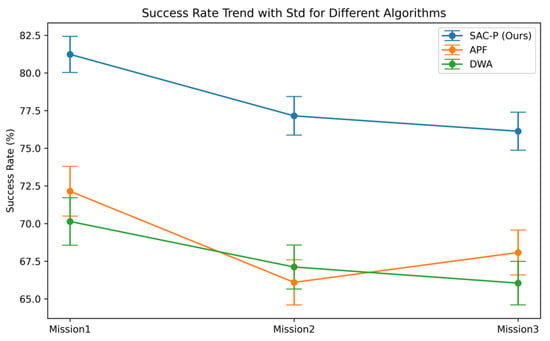

To further assess how the proposed SAC-P-based framework and decision-making strategy perform relative to conventional navigation and obstacle avoidance approaches in mission execution, we compared it against counterparts implemented with the APF and DWA algorithms under the same experimental settings described earlier. The overall results are reported in Table 6, with success rate comparisons illustrated in Figure 12. A detailed analysis of the outcomes for the three mission scenarios is presented as follows.

Table 6.

Performance comparison of cross-scene methods (with Non-DRL baseline).

Figure 12.

The success rate of different algorithms for each mission (with Non-DRL baseline).

In Mission 1, the SAC-P achieved the highest SR (81.23 ± 1.20%), representing a relative improvement of 9.08 and 11.09 percentage points over APF (72.15 ± 1.65%) and DWA (70.14 ± 1.58%), respectively. The CR was limited to 15.02 ± 1.01%, significantly lower than APF (22.08 ± 1.28%) and DWA (23.06 ± 1.25%). Both OR (1.02 ± 0.40%) and TR (3.01 ± 0.49%) were lower than those of the baselines. SAC-P also achieved the shortest ATS (61.26 ± 0.35), outperforming APF by 4.09 steps and DWA by 5.50 steps. The consistently low SD values confirm that these performance gains were stable across repeated runs, underscoring SAC-P’s robustness and superior navigation efficiency in this mission.

In the more challenging Mission 2, SAC-P maintained its dominance with an SR of 77.15 ± 1.28%, outperforming APF (66.10 ± 1.50%) by 11.05 percentage points and DWA (67.12 ± 1.46%) by 10.03 percentage points. It also recorded the lowest CR (18.04 ± 1.02%), OR (2.01 ± 0.48%), and TR (3.05 ± 0.41%) among all methods, indicating reduced mission failure risks. Furthermore, SAC-P achieved the shortest ATS (66.33 ± 0.42), which translates into 1.72 and 1.61 fewer steps than APF and DWA, respectively. The narrow SD margins again confirm that its performance advantages were consistent and not the result of experimental variance.

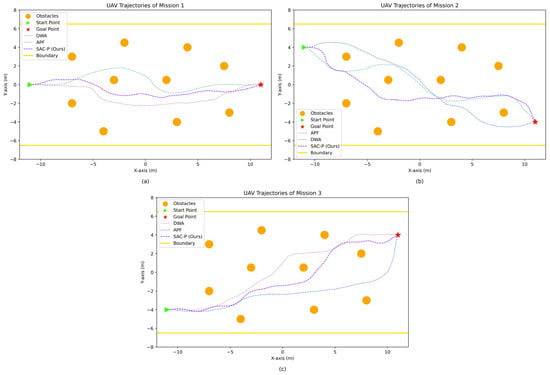

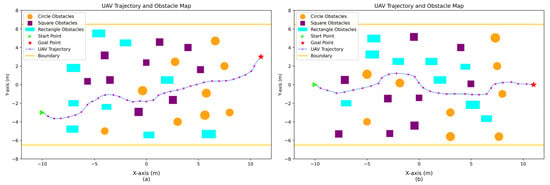

For Mission 3, SAC-P sustained its lead with an SR of 76.13 ± 1.26%, compared to APF (68.08 ± 1.49%) and DWA (66.05 ± 1.44%). Its CR (17.07 ± 1.03%) was substantially lower than that of APF (24.04 ± 1.26%) and DWA (24.06 ± 1.27%). Although APF achieved a marginally lower OR (2.01 ± 0.46% vs. SAC-P’s 2.02 ± 0.47%), SAC-P retained the advantage in TR (5.04 ± 0.48%) and ATS (66.22 ± 0.40), outperforming APF and DWA by 2.69 and 3.34 steps, respectively. This reflects SAC-P’s ability to retain high success rates while minimizing travel time even in stochastic scenarios. Across all missions, the SAC-P-based UAV navigation and obstacle avoidance framework consistently achieved the highest SR and delivered optimal results across CR, OR, TR, and ATS. Compared with APF- and DWA-based counterparts, it demonstrated clear advantages in mission efficiency, safety, and robustness. These outcomes affirm the method’s superior performance in completing tasks efficiently, reducing failure likelihood, and maintaining robust operation under identical environmental conditions. The comparison of the UAV trajectories of the proposed method with the baselines of different Non-DRL algorithms in each task is shown in Figure 13a, Figure 13b, Figure 13c, respectively.

Figure 13.

The UAV’s motion trajectories in each task (with Non-DRL baseline): (a) mission 1; (b) mission 2; (c) mission 3.

4.3.3. Generalization Performance Testing

To examine the generalization capability of the proposed SAC-P-based UAV navigation and obstacle avoidance framework, we performed a dedicated generalization test. A single experiment comprised 100 episodes, which were repeated three times independently with different random seeds. At the start of each episode, the obstacle configuration was randomly regenerated. To analyze performance across varying conditions, we designed two distinct task scenarios. Scenario 1 featured sparsely distributed homogenous obstacles. Scenario 2, inspired by the configurations in [39,40], contained a dense arrangement of heterogeneous obstacles with circular, square, and rectangular cross-sections. Because the initial and target positions, as well as obstacle arrangements, varied between episodes, the required number of time steps also varied. As such, the evaluation focused exclusively on four metrics: SR, CR, OR, and TR.

- 3.

- Simple Obstacle Scenario Test

Table 7 summarizes the results for Scenario 1, where the proposed SAC-P-based autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance framework was evaluated in an environment featuring randomly distributed, homogeneous obstacles. achieved an SR of 79.12 ± 1.85%, with CR (17.06 ± 1.42%), OR (2.01 ± 0.45%), and TR (2.04 ± 0.47%) all maintained at low levels. The relatively small SD values (≤±1.85%) indicate that performance remained stable and reproducible across all unseen map configurations, demonstrating strong adaptability to novel environments. Importantly, the task settings, obstacle positions, and spatial configurations in this scenario were entirely unseen during training, making the results a direct measure of the framework’s adaptability and transferability to unfamiliar environments.

Table 7.

Generalization performance test results (Scenario 1).

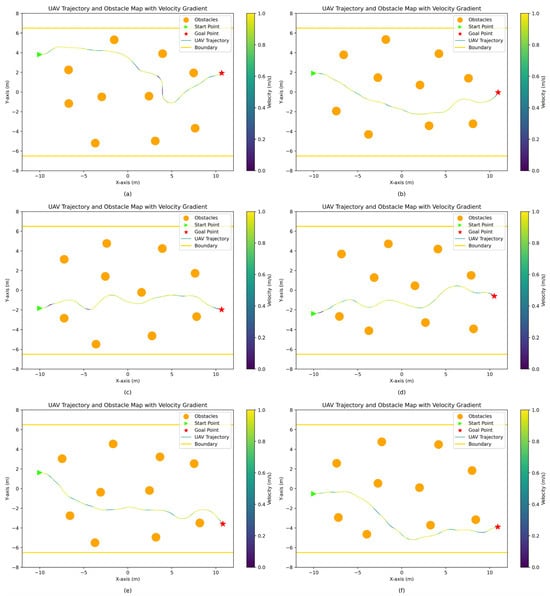

The combination of low CR and OR indicates that the UAV could reliably detect and avoid obstacles under a completely new map topology, while the low TR reflects efficient path planning and decision-making even in untrained scenarios. Together, these findings underscore the framework’s strong generalization capability, demonstrating that navigation policies learned in training can be effectively and robustly applied to new, more uncertain task conditions. Representative UAV trajectories and corresponding obstacle configurations for selected episodes in Scenario 1 are depicted in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

The UAV trajectories and their corresponding obstacle distributions (Scenario 1): (a–f) denote different test episodes, respectively.

- 4.

- Complex Obstacle Scenario Test

As environmental complexity increases—particularly when obstacles are heterogeneous, densely packed, and randomly distributed—UAV navigation and obstacle avoidance place heightened demands on environmental perception, path planning, and decision stability. Table 8 reports the results for Scenario 2.

Table 8.

Generalization performance test results (Scenario 2).

The SAC-P-based framework achieved an SR of 72.08 ± 2.14%, lower than the 79.12% attained in Scenario 1, reflecting the increased difficulty of trajectory planning in the presence of dense and irregular obstacle fields. The CR rose to 22.04 ± 1.68% (+5 percentage points compared with Scenario 1), indicating that denser obstacle configurations increased the frequency of local avoidance maneuvers and collision risk. Nevertheless, both OR (2.02 ± 0.48%) and TR (4.01 ± 0.52%) remained low, demonstrating that the framework could maintain operational safety and execution stability even in high-uncertainty environments.

The relatively small SD values across all metrics (≤±2.14%) confirm that these results are statistically stable, and that SAC-P’s performance degradation from Scenario 1 to Scenario 2 is moderate and consistent, rather than the result of isolated failures. This indicates that the proposed framework preserves robust generalization capability and reliable decision-making in complex, previously unseen operational contexts.

Trajectory analysis in Figure 15 further reveals that, even in the complex scenario, the UAV maintained smooth path generation without excessive turning or futile backtracking. This indicates that the framework’s high-level decision module can preserve stable, efficient global planning despite pronounced local environmental changes, avoiding both decision oscillation and overly conservative maneuvers. Collectively, these results reinforce the framework’s robustness in maintaining path continuity and decision consistency in challenging environments, confirming its strong global planning capabilities.

Figure 15.

The UAV trajectories and their corresponding obstacle distributions (Scenario 2): (a,b) denote different test episodes, respectively.

4.3.4. Performance Evaluation of Single-Sensor and Sensor Fusion Frameworks

To assess the relative merits of the proposed UAV DRL framework—which fuses depth camera and LiDAR perception—against single-sensor counterparts, we performed a sensor configuration comparison while keeping the decision-making algorithm (SAC-P) fixed across all tests. Three input configurations for environmental observation were evaluated: depth camera only, LiDAR only, and the fusion of depth camera with LiDAR. The same preprocessing pipeline was applied to all sensory data to ensure fairness and comparability, and the experimental scenario was configured identically to Mission 1 in the aforementioned comparative tests, with each sensor configuration tested over 100 episodes. Each experiment was independently repeated three times with different random seeds. Performance was evaluated across six metrics: SR, CR, OR, TR, ATS, and an additional measure—Average single-step decision time (ASDT)—to gauge real-time decision-making efficiency.

The results, summarized in Table 9, show that sensor selection substantially affects mission performance even under identical decision-making policies. The consistently small SD values (generally ≤±1.8% for rate-based metrics, ≤±0.5 steps for ATS, and ≤±0.004 s for ASDT) indicate stable and reproducible performance across runs. The proposed Depth camera + LiDAR fusion configuration achieved the highest success rate (SR) of 81.23 ± 1.20%, outperforming the Depth camera–only setup (68.15 ± 1.65%) by 13.08 percentage points and the LiDAR–only setup (72.14 ± 1.58%) by 9.09 percentage points. It also yielded the lowest collision rate (CR) (15.02 ± 1.01%), minimal out-of-bounds rate (OR) (1.02 ± 0.40%), and the lowest timeout rate (TR) (3.01 ± 0.49%) among all configurations.

Table 9.

Performance comparison of frames with different sensors.

In terms of navigation efficiency, the fusion system achieved the shortest average time steps (ATS) (61.26 ± 0.35), reducing task completion time by 2.89 steps compared with Depth camera–only and by 1.89 steps compared with LiDAR–only configurations. This improvement reflects the enhanced environmental awareness and more optimal route selection achievable through the complementary sensing modalities. Regarding decision-making latency, the fusion setup exhibited a slightly higher ASDT (0.043 ± 0.002 s) than the single-sensor configurations (Depth camera: 0.031 ± 0.002 s, LiDAR: 0.029 ± 0.002 s), attributable to the additional computational overhead from sensor fusion and feature integration. However, this latency increase is negligible relative to the UAV control cycle and does not adversely affect real-time execution.

Overall, these findings confirm that combining depth camera and LiDAR perception within the proposed DRL framework delivers superior performance and robustness over single-sensor approaches, enabling more reliable, higher-success navigation in complex and uncertain environments.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Overall Conclusions

This work addresses the challenge of autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance for UAVs operating in complex, stochastic environments by proposing a deep reinforcement learning (DRL) framework that fuses multimodal perception from LiDAR and depth cameras. The framework is designed to deliver both high efficiency and robustness in navigation tasks. To enhance perception accuracy and reliability, we developed a multi-sensor data preprocessing pipeline that extracts multimodal features, significantly improving the UAV’s ability to perceive and adapt to intricate obstacle distributions. To overcome the inherent inefficiency of DRL in sample utilization, we introduce an improved SAC-P algorithm as the framework’s high-level decision-making module, which accelerates convergence and enhances training stability through more effective sample usage.

High-fidelity simulation experiments built on the ROS and Gazebo platforms were conducted to comprehensively validate the performance of the proposed framework. Experimental results demonstrate that the SAC-P-based framework significantly outperforms existing baseline algorithms in key performance metrics, such as mission success rate, collision rate, and average time steps, showcasing its efficient navigation and obstacle avoidance performance in complex stochastic obstacle environments. These findings provide important theoretical and technical support for UAV autonomous operation in unknown environments.

5.2. Future Work

In future work, we plan to incorporate more real-world environmental factors into the modeling and algorithm design of the autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance framework, including wind field disturbances, dynamic obstacles, GPS signal drift, delay of UAV controller and multisource sensor noise. For such challenging conditions, further improvements will be made to the high-level decision-making algorithm, along with the design of effective compensation and robustness enhancement mechanisms, to strengthen the system’s adaptability and stability in dynamic and unstructured environments. Furthermore, we will extend the framework from static to dynamic scenarios and systematically verify its generalization capability and anti-interference performance under real mission conditions through Sim-to-Real transfer experiments. In addition, efforts will be devoted to deeply optimizing computational efficiency to meet the strict latency requirements of real-time navigation, thereby providing more reliable technical support for UAV deployment in complex real-world environments.

In addition, we also plan to extend the proposed framework from single-UAV navigation to multi-UAV cooperative missions, leveraging robust depth camera–LiDAR fusion perception, an efficient decision-making mechanism, and reliable inter-UAV communication to achieve swarm-level cooperative navigation and obstacle avoidance in complex environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L. and Z.R.; methodology, B.L.; software, B.L.; validation, B.L., W.H. and S.J.; formal analysis, B.L. and Z.R.; investigation, B.L.; resources, S.J.; data curation, W.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L.; writing—review and editing, S.J. and W.H.; visualization, B.L.; supervision, S.J.; project administration, W.H.; funding acquisition, Z.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Qingdao Key Technology Research and Industrialization Demonstration Project of Qingdao City, Shandong Province, China, grant number 24-1-3-hygg-12-hy.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Alam, M.M.; Moh, S. Joint Topology Control and Routing in a UAV Swarm for Crowd Surveillance. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2022, 204, 103427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, T.; Huang, S.; Li, K. A Hybrid Optimization Framework for UAV Reconnaissance Mission Planning. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 173, 108653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Wu, B.; Guo, D.; Chen, X. Autonomous Navigation UAVs for Enhancing Information Freshness for Reconnaissance. Electronics 2024, 13, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alpiste, I.; Golcarenarenji, G.; Wang, Q.; Alcaraz-Calero, J.M. Search and Rescue Operation Using UAVs: A Case Study. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2021, 178, 114937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Han, S.R.; Song, B.D. Simultaneous Cooperation of Refrigerated Ground Vehicle (RGV) and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) for Rapid Delivery with Perishable Food. Appl. Math. Modell. 2022, 106, 844–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Carmona, E.; Vasquez-Gomez, J.; Herrera-Lozada, J. Environmental Monitoring Using Embedded Systems on UAVs. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2020, 18, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, Q.; Zhu, M. UAV 3-Dimension Flight Path Planning Based on Improved Rapidly-Exploring Random Tree. In Proceedings of the 2019 Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Nanchang, China, 3–5 June 2019; pp. 921–925. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, W. An Environmental Potential Field Based RRT Algorithm for UAV Path Planning. In Proceedings of the 2018 37th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Wuhan, China, 25–27 July 2018; pp. 9922–9927. [Google Scholar]

- Primatesta, S.; Guglieri, G.; Rizzo, A. A Risk-Aware Path Planning Strategy for UAVs in Urban Environments. J. Intell. Rob. Syst. 2019, 95, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xu, L.; Zhen, R.; Wu, X. Bi-Directional Adaptive A* Algorithm toward Optimal Path Planning for Large-Scale UAV under Multi-Constraints. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 85431–85440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Dai, J.; He, C. A Novel Real-Time Penetration Path Planning Algorithm for Stealth UAV in 3D Complex Dynamic Environment. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 122757–122771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivanoglu, Y.V. A New Vibrational Genetic Algorithm Enhanced with a Voronoi Diagram for Path Planning of Autonomous UAV. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2012, 16, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, V.; Tarbouchi, M.; Labonté, G. Fast Genetic Algorithm Path Planner for Fixed-Wing Military UAV Using GPU. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2018, 54, 2105–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ye, F.; Jiang, T. Path Planning under Obstacle-Avoidance Constraints Based on Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 17th International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT), Chengdu, China, 27–30 October 2017; pp. 1434–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guan, X.; Delahaye, D. Adaptive Sensitivity Decision Based Path Planning Algorithm for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle with Improved Particle Swarm Optimization. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2016, 58, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lyu, W.; Yao, P.; Liang, X.; Liu, C. Three-Dimensional Path Planning for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Based on Interfered Fluid Dynamical System. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2015, 28, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.Z.; Nasir, N.A.; Rashid, R.B. A Review of Perception Sensors, Techniques, and Hardware Architectures for Autonomous Low-Altitude UAVs in Non-Cooperative Local Obstacle Avoidance. Rob. Auton. Syst. 2024, 173, 104629. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G.; Jain, S.; Sharma, R.S. Path Planning for Fully Autonomous UAVs-a Taxonomic Review and Future Perspectives. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 13356–13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, S.; Cho, G.; Oh, J.; Tran, X.-T.; Oh, H. Autonomous UAV Trail Navigation with Obstacle Avoidance Using Deep Neural Networks. J. Intell. Rob. Syst. 2020, 100, 1195–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, H.; Niculescu, V.; Polonelli, T.; Magno, M.; Benini, L. Robust and Efficient Depth-Based Obstacle Avoidance for Autonomous Miniaturized UAVs. IEEE Trans. Rob. 2023, 39, 4935–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburaya, A.; Selamat, H.; Muslim, M.T. Review of Vision-Based Reinforcement Learning for Drone Navigation. Int. J. Intell. Rob. Appl. 2024, 8, 974–992. [Google Scholar]

- AlMahamid, F.; Grolinger, K. Autonomous Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Navigation Using Reinforcement Learning: A Systematic Review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 115, 105321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yu, G.; Meng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. Autonomous Obstacle Avoidance of UAV Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 42, 3323–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Tang, Y. Deep-Reinforcement-Learning-Based UAV Autonomous Navigation and Collision Avoidance in Unknown Environments. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2024, 37, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, C.; Xiao, J.; Feroskhan, M. NPE-DRL: Enhancing Perception Constrained Obstacle Avoidance with Nonexpert Policy Guided Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2025, 6, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Low, K.H.; Lyu, C. Partially-Observable Monocular Autonomous Navigation for UAV through Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2023 Forum; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–16 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Peng, X.-Z. Autonomous Quadrotor Navigation with Vision Based Obstacle Avoidance and Path Planning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 102450–102459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Li, N.; Zhang, C. UAV Environmental Perception and Autonomous Obstacle Avoidance: A Deep Learning and Depth Camera Combined Solution. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 175, 105523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubí, B.; Morcego, B.; Pérez, R. Quadrotor Path Following and Reactive Obstacle Avoidance with Deep Reinforcement Learning. J. Intell. Rob. Syst. 2021, 103, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hou, Z.; Chen, H.; Lu, P. DRL-Based Path Planner and Its Application in Real Quadrotor with LIDAR. J. Intell. Rob. Syst. 2023, 107, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, P.; Benavidez, P.; Jamshidi, M. Survey of Datafusion Techniques for Laser and Vision Based Sensor Integration for Autonomous Navigation. Sensors 2020, 20, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirci, M. A Novel Swarm Unmanned Aerial Vehicle System: Incorporating Autonomous Flight, Real-Time Object Detection, and Coordinated Intelligence for Enhanced Performance. Trait. Signal 2023, 40, 2063–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Soft Actor-Critic: Off-Policy Maximum Entropy Deep Reinforcement Learning with a Stochastic Actor. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.01290. [Google Scholar]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Hartikainen, K.; Tucker, G.; Ha, S.; Tan, J.; Kumar, V.; Zhu, H.; Gupta, A.; Abbeel, P.; et al. Soft Actor-Critic Algorithms and Applications 2019. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.05905. [Google Scholar]

- Schaul, T.; Quan, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Silver, D. Prioritized Experience Replay 2016. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.05952. [Google Scholar]

- Oliehoek, F.A.; Amato, C. A Concise Introduction to Decentralized POMDPs; SpringerBriefs in Intelligent Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-3-319-28927-4. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. Uav Simulator. Available online: https://github.com/Zhefan-Xu/NavRL/tree/main/ros1/uav_simulator (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Lillicrap, T.P.; Hunt, J.J.; Pritzel, A.; Heess, N.; Erez, T.; Tassa, Y.; Silver, D.; Wierstra, D. Continuous Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.02971. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, S.; van Hoof, H.; Meger, D. Addressing Function Approximation Error in Actor-Critic Methods. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.09477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, O. Real-Time Obstacle Avoidance for Manipulators and Mobile Robots. In Proceedings of the 1985 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation Proceedings, St. Louis, MO, USA, 25–28 March 1985; Volume 2, pp. 500–505. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, D.; Burgard, W.; Thrun, S. The Dynamic Window Approach to Collision Avoidance. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 1997, 4, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).