Abstract

This work develops and validates a high-order, three-dimensional Carrera Unified Formulation (CUF) framework for coupled structural–acoustic eigenanalysis, aiming at accurate low-frequency modal characterization of interior cavity-structure systems with significantly reduced degrees of freedom. The proposed approach employs high-order polynomial expansions to discretize both the structural and fluid domains. The methodology integrates fully coupled fluid-structure analyses into a unified variational formulation, enabling the systematic assembly of global stiffness and mass matrices via sophisticated numerical integration techniques. Validation against a Comsol Multiphysics benchmark model confirms that the CUF-based high-order frameworks converge with significantly fewer degrees of freedom and reliably capture the intricate interactions at the fluid–structure interface. In addition, the approach is versatile, accommodating a range of boundary conditions and material models, underscoring its broad applicability in modern engineering design. Overall, this work advances the state of the art in vibroacoustic analysis by offering a robust tool for predicting natural frequencies and mode shapes, and it lays the groundwork for future extensions to nonlinear, transient, and data-driven applications.

1. Introduction

This paper introduces a coupled displacement–pressure formulation based on the Carrera Unified Formulation (CUF) for high-order vibroacoustic modal analysis. Unlike conventional finite-element (FE) approaches that rely on full three-dimensional discretizations, the present formulation uses high-order polynomial expansions along each local coordinate. The reduction in unknowns lowers computational cost while preserving the accuracy of natural frequencies and mode shapes. The framework integrates the fully coupled analysis and applies to aerospace, automotive, and civil structures [1].

The proposed approach leverages the inherent advantages of CUF by decoupling cross-sectional and thickness behavior within three-dimensional elements. By employing tailored polynomial bases for structural displacement and acoustic pressure fields, the formulation systematically reduces the problem dimension without sacrificing essential physical details. In particular, the frequency-domain analysis focuses on generalized eigenvalue problems that characterize the system’s dynamic response under various boundary conditions. Fluid–structure coupling is enforced through standard interface conditions and verified against established benchmarks and a commercial solver [2,3].

The contribution is a robust numerical implementation that clarifies the vibroacoustic mechanisms relevant at low frequency. Combining high-order finite elements with a unified formulation provides an efficient tool for the design and optimization of structures with coupled behavior.

1.1. Background and Motivation

Vibroacoustic phenomena influence performance across aerospace, automotive, civil, and architectural applications. The interplay between structural vibrations and the surrounding acoustic field affects noise, energy transmission, and comfort. In aircraft, interactions between the skin and the internal acoustic field can modify cabin noise and influence integrity; analogous considerations arise in vehicles and buildings.

Traditional finite-element models often require full three-dimensional meshes to capture fluid–structure interaction, which can be costly at high frequency or large scale. Reduced-order strategies address this by retaining the essential physics while limiting the number of unknowns. CUF decouples cross-sectional and through-thickness behavior within three-dimensional elements and, by using high-order polynomial expansions, decreases the degrees of freedom (DoFs) needed to represent structural displacements and acoustic pressure fields [4]. Refined FE methods and unified formulations have been rigorously validated against experimental and commercial solver benchmarks, enhancing confidence in their predictive capabilities for high-frequency vibroacoustic phenomena [5,6]. Such innovations not only improve the accuracy of modal analyses but also enable engineers to explore a broader design space, facilitating the development of next-generation structures that are both lightweight and acoustically optimized.

Moreover, recent progress in the field has integrated novel methodologies, such as machine learning techniques, to further optimize acoustic properties and tailor meta-material performance [7,8]. Recent work on acoustic black holes (ABHs) in plates has shown effective vibration attenuation and increased transmission loss, including in plate-cavity configurations [9,10,11].

The goal is to reconcile computational efficiency with high-fidelity modeling. The CUF-based approach provides an alternative to traditional methods for exploring the interactions in coupled fluid–structure systems while meeting performance criteria such as noise reduction, structural integrity, and energy efficiency.

1.2. State of the Art

Over the past decades, variants of the traditional finite element method (FEM) for acoustic–structural coupling have been widely employed to model complex interactions between structures and the surrounding fluid. However, these conventional approaches generally rely on full three-dimensional discretizations that result in large systems and high computational costs, particularly when addressing high-frequency dynamics or large-scale configurations [12]. In contrast, CUF has emerged as a compelling alternative, exploiting cross-sectional polynomial expansions to significantly reduce the problem’s dimensionality while maintaining high accuracy in predicting natural frequencies and mode shapes.

Recent developments in CUF and related high-order FE techniques have advanced the state of the art by integrating refined kinematics and nonlinearity into the formulation. Notable contributions include the unified approach for multilayered plates and shells developed by Carrera et al., which has been extended to account for geometrically nonlinear behavior and complex material anisotropy [13]. The application of refined shell elements has been extended to functionally graded structures, indicating a pathway for future research in this area [14]. The development of variable-kinematic shell elements has also shown promise for analyzing electromechanical problems, suggesting potential extensions of the current framework [15]. Furthermore, developing MITC9 finite elements based on the Reissner-Mindlin Variational Theorem has improved the analysis of laminated shells [16]. These studies not only validate the robustness of the CUF-based approach but also highlight its versatility in handling various boundary conditions and coupling scenarios. Several recent works have also explored vibroacoustic models for composite or multilayered structures relying on CUF. Specifically, Dozio et al. [17] presented a novel finite element strategy that can be used to analyze thick multilayer plates with embedded cavities, demonstrating improved predictive accuracy of fluid–structure interaction using higher-order modeling; compared to that study, this research aims to create a more general three-dimensional fluid–structure framework that incorporates higher-order expansions and covers a broader range of validations.

In addition, emerging methodologies that combine CUF with data-driven techniques—such as machine learning—are beginning to influence the field [18]. For example, recent research has employed genetic algorithms and artificial neural networks to optimize the acoustic properties of metamaterials, thereby offering new avenues for tuning band gaps and resonance characteristics in coupled systems. Incremental moduli and band-gap tuning in pre-stressed viscoelastic composites have been effectively demonstrated [19]. The effect of preload on wave-propagation characteristics in hexagonal lattices has been detailed in previous studies [20]. Antiplane elastic wave propagation studies have shown that band gaps can be tuned by prestress [21]. Similar effects of pre-stress on band-gap distributions have been observed in quasiperiodic structures [22]. Furthermore, the defect-induced annihilation mechanisms in pre-stressed elastic structures [23] highlight the sensitivity of wave propagation to initial stress conditions. Further work on tunable elastodynamic band gaps has provided insights into the switching phenomena in pre-stressed structures [24]. Optimal design strategies employing genetic algorithms for phononic media have been proposed [25]. Moreover, operational modal analysis (OMA) can be employed when extensive in-flight or in-operation data are available for large-scale systems, such as helicopter cabins, to identify key vibro-acoustic modes without interrupting normal operations [26]. In parallel to domain-based FE strategies, boundary integral approaches have matured for both interior and exterior Helmholtz problems, including coupled vibroacoustic settings [27]. The current state of the art reflects a vibrant interplay between advanced theoretical developments and practical computational techniques, paving the way for increasingly efficient and accurate vibroacoustic analyses.

2. Methodological Framework

The methodological framework presented herein integrates advanced FE techniques with CUF to computationally efficiently address complex vibroacoustic phenomena. At its core, the formulation exploits high-order polynomial expansions in both the cross-sectional and through-thickness directions, significantly reducing the overall number of degrees of freedom compared with conventional full three-dimensional discretizations. This reduction is critical for accurately capturing the dynamic behavior of coupled fluid–structure systems while keeping computational costs within practical limits.

A distinctive feature of the framework is its explicit treatment of the fluid–structure interface. Coupling matrices are derived from consistent interface conditions that ensure the continuity of the displacement and pressure fields. Such a rigorous approach to interface modeling is validated against experimental data and benchmarked with commercial solvers, reinforcing the framework’s robustness in capturing the intricacies of vibroacoustic interactions [2,3].

The generalized symmetric eigenproblems were solved by a sparse shift-invert Lanczos method targeting the lowest part of the spectrum; the factorization of the shifted stiffness pencil is Cholesky. Convergence is assessed on relative residual norms of the computed Ritz pairs. Results are reproducible from the element orders, quadrature, boundary conditions, and mesh partitions explicitly stated in the tables and captions; absolute timings are implementation- and hardware-dependent and are therefore not reported here.

2.1. Kinematic Assumptions

In the proposed formulation, the kinematic assumptions form the cornerstone for decoupling the complex spatial behavior of the system into more manageable one-dimensional and two-dimensional components. Central to this approach are high-order polynomial expansions that separately approximate the in-plane (i.e., cross-sectional) and through-thickness variations of both the structural displacement and acoustic pressure fields. By leveraging such tailored expansions, CUF enables a significant reduction in the overall degrees of freedom without compromising the fidelity of the dynamic response prediction. High-order and complex-curvature mode shapes, especially in rotating or multi-component assemblies such as wind turbine blades, demand a formulation capable of accurately capturing both local deformation and mode coupling [28]. Such phenomena underscore the necessity of high-fidelity modeling approaches, such as the CUF-based method proposed here, to resolve coupled multi-physics interactions across a wide frequency range.

The high-order shape functions are computed using one-dimensional Lagrange interpolation formulas, which are then combined in a tensor-product fashion to build three-dimensional shape functions. The resulting formulation naturally enforces compatibility between the structural displacement and acoustic pressure fields at the fluid–structure interface. By systematically decoupling the spatial variables, the formulation facilitates a robust modal analysis and provides a unified framework that can be extended to encompass nonlinearities and transient phenomena. This kinematic strategy has its foundations in seminal work by Carrera and colleagues [1] and is validated by numerous studies on structural vibrations and wave propagation in complex media.

2.1.1. Structural Displacement Field

In this formulation, the structural displacement field is rigorously discretized by decoupling the cross-sectional and through-thickness behaviors. Under the assumption of linear elasticity, the displacement vector

is expressed as a separated expansion. In the framework of the Carrera Unified Formulation, the 3D displacement field is written as a general expansion of the primary unknowns that, in the case of a beam, is reported in Equation (2):

in which represents a set of cross-section expansion functions, indicates the generalized displacement vector depending on the y coordinate, N is the order of expansion in the thickness direction and the repeated index denotes summation. The expansion functions can be chosen based on the specific requirements of the problem. In the present work, Lagrange polynomials [29], from now on indicated by “LE”, are assumed for the expansion functions ; in this case, the unknown variables are pure displacements. According to FEM, the generalized displacement vector is approximated based on the FE nodal parameters and shape functions as reported in Equation (3):

in which are the ith shape functions, represents the unknown nodal variables, is the number of nodes per element and i indicates summation. For a given number of nodes , the one-dimensional Lagrange basis functions are defined as

where denotes the jth nodal coordinate in the reference domain . Their derivatives are given by

These one-dimensional basis functions serve as the building blocks for the tensor-product construction of the three-dimensional shape functions used in the CUF framework. Cross-section () interpolation employs quadrilateral Lagrange elements: LE4 (bilinear, degree 1), LE9 (biquadratic, degree 2), and LE16 (bicubic, degree 3). Through-thickness (y) interpolation uses a 1D Lagrange polynomial of order B3 (quadratic, degree 2). Numerical integration uses Gauss-Legendre quadrature with exactness for the polynomial degree of the integrands: 2 × 2 points for LE4, 3 × 3 for LE9, 4 × 4 for LE16 in the cross-section, and 3-point Gauss in the thickness (B3). This choice exactly integrates products of shape functions and their derivatives up to the corresponding degrees.

The separated expansion strategy significantly reduces the computational burden by limiting the degrees of freedom without sacrificing the resolution of local deformation modes. Moreover, this method facilitates the integration of complex boundary and interface conditions, particularly at the fluid–structure interface, where the displacement field must seamlessly interact with the acoustic pressure field.

2.1.2. Acoustic Pressure Field

The acoustic pressure field is modeled with the same high-order precision as the structural displacement field, albeit with modifications that account for the inherently different physics of fluids. In this formulation, the pressure is approximated by a separated expansion that decouples the cross-sectional behavior from the through-thickness variation:

where are the high-order cross-sectional shape functions and are the generalized pressure functions along the y-axis. This approach leverages polynomial expansions to capture the pressure field’s spatial variability with high accuracy while keeping the number of degrees of freedom to a minimum.

Analogous techniques for the structural field are employed, including evaluating one-dimensional Lagrange polynomials and their tensor-product combinations to construct three-dimensional shape functions. These functions are integrated over the fluid domain using Gauss-Legendre quadrature, ensuring that the fluid’s stiffness and mass matrices are assembled with high numerical precision. The fluid matrices are constructed using a Helmholtz-like formulation, in which the inverse of the fluid density and the square of the wave speed play critical roles in the pressure-field scaling. This formulation aligns well with the weak form of the Helmholtz equation, ensuring that the pressure field satisfies the necessary acoustic boundary conditions, such as pressure-release boundaries (Dirichlet pressure). In interior-cavity problems, pressure-release boundaries represent soft walls: they reflect outgoing waves with a phase inversion and therefore do not absorb energy. They are used to define finite acoustic subdomains (e.g., closed cavity faces) [30]. When an open, effectively unbounded acoustic region is modeled, non-reflecting conditions such as perfectly matched layers (PMLs) or impedance boundaries must be employed instead. Those techniques are outside the present scope, which targets interior cavity-panel eigenpairs [30].

Moreover, by decoupling the spatial dimensions, the CUF-based framework efficiently bridges the gap between the fluid and structural domains. At the fluid–structure interface, the continuity conditions between the pressure field and the normal component of the structural displacement are rigorously enforced through dedicated coupling matrices. This not only enhances the predictive accuracy of the coupled system but also ensures that the fluid dynamics are robustly captured even in the presence of complex geometrical and material discontinuities [31].

2.2. Governing Equations in the Frequency Domain

In the frequency domain, the dynamic behavior of the coupled fluid–structure system is described by reformulating the governing equations into generalized eigenvalue problems. Eigenmode relationships between shell vibration and acoustic modes can be exploited to predict sound fields in structure–acoustic systems [32]. For the structural domain, the equilibrium equations and corresponding constitutive laws are transformed into a weak form through the principle of virtual work. This process results in a discretized system characterized by the global stiffness matrix and the mass matrix . Concurrently, the fluid domain is modeled using a Helmholtz-type formulation, in which the pressure field is governed by an analogous weak form that yields a distinct set of global matrices. These weak formulations are integrated using high-order numerical integration techniques, such as Gauss-Legendre quadrature. This ensures that the high-order polynomial expansions—employed in structural and acoustic discretizations—are integrated with high accuracy. For the structural domain, the element stiffness matrix is computed as

and the corresponding element mass matrix is given by

Here, is the strain–displacement matrix, is the constitutive matrix (with Lamé constants for isotropic materials or the appropriate stiffness coefficients for orthotropic ones), is the shape function matrix, is the material density, J is the Jacobian matrix of the transformation from the reference element, and denotes the Gauss quadrature weights. Similarly, for the fluid domain, the elemental acoustic matrices are defined as

where is the fluid density and is the speed of sound in the fluid. A key aspect of this formulation is the rigorous treatment of the fluid–structure interface. Continuity conditions, which enforce the compatibility of the structural displacement field with the acoustic pressure gradient, introduce additional off-diagonal coupling matrices. These matrices seamlessly integrate the fluid and structural responses into a unified global system, yielding a block-structured eigenvalue problem that directly provides the natural frequencies and mode shapes of the coupled system.

2.2.1. Structural Domain

In the structural domain, the dynamic behavior is governed by the balance of linear momentum under the assumption of small deformations and linear elasticity. Starting from the strong form of the equilibrium equations, the displacement field is cast into a weak form using the principle of virtual work. This procedure yields a set of coupled equations in the frequency domain, which the generalized eigenvalue problem can succinctly represent as

where and denote the global stiffness and mass matrices, respectively, and is the vector of generalized nodal displacements. The high-order shape functions and their derivatives, which are then used to formulate the strain–displacement matrix, are integrated using Gauss-Legendre quadrature. The resultant global matrices incorporate the contributions of all elements after appropriate assembly, thereby providing a robust basis for solving the eigenvalue problem that reveals the system’s natural frequencies and mode shapes.

2.2.2. Acoustic Domain

In the acoustic domain, the governing equations are derived from the linearized acoustic wave equation under the assumption of harmonic time dependence. By assuming the form , the governing partial differential equation reduces to the Helmholtz equation:

where represents the acoustic wavenumber and c denotes the fluid’s sound speed. The corresponding weak formulation is obtained by multiplying the Helmholtz equation by an appropriate test function w and integrating over the fluid domain :

where represents a prescribed acoustic flux (or normal derivative of the acoustic pressure) applied on a boundary segment . This weak formulation is then discretized using high-order polynomial expansions that mirror the strategy adopted in the structural domain. The acoustic shape functions and their gradients, assembled via tensor-product formulations, facilitate the construction of the elemental acoustic stiffness matrix and mass matrix with high numerical precision through Gauss-Legendre quadrature.

The resulting discrete system for the acoustic domain is expressed as a generalized eigenvalue problem:

where encapsulates the nodal pressure degrees of freedom. Accurate assembly of these matrices is critical for capturing the fluid’s dynamic behavior, particularly when modeling phenomena such as wave dispersion and resonant pressure modes.

Appropriate boundary conditions are applied to the acoustic domain to mimic realistic scenarios. For instance, pressure-release boundaries, which enforce on the outer boundaries, are typically implemented to damp outgoing waves and simulate an unbounded fluid region. In other cases, Neumann-type (rigid) boundary conditions are imposed, requiring that the normal derivative of the pressure vanish. The flexibility in imposing these conditions enables the framework to simulate a range of practical applications accurately.

Furthermore, integrating the acoustic formulation within the CUF framework enables seamless coupling with the structural domain. The resulting off-diagonal coupling matrices are computed to ensure continuity of the pressure field and the normal component of structural displacements at the fluid–structure interface. This unified approach is validated against benchmark studies and commercial solvers, underscoring its robustness in modeling complex fluid–structure interactions.

2.3. Fluid–Structure Coupling

The fluid–structure coupling represents a pivotal aspect of the overall formulation, capturing the intricate interplay between the acoustic and structural fields. In the frequency domain, this coupling is achieved by rigorously enforcing interface conditions that ensure the continuity of the normal displacement and its corresponding stress components across the fluid–structure interface. These conditions effectively link the structural displacement field with the acoustic pressure gradient, unifying the two subdomains into a single, coherent model. The fluid–structure coupling is enforced via the standard interface conditions: continuity of normal acceleration and equilibrium of normal tractions. In the frequency domain, these read

where u is the structural displacement, p the acoustic pressure, n the unit normal (fluid→structure), the fluid density, and the interface. Their weak imposition leads to the consistent, symmetric coupling blocks used herein. The above expressions are classical in displacement–pressure fluid–structure interaction (FSI) formulations for structural acoustics [33]. In the assembled pencil , the coupling matrices arise from the interface integrals. With standard finite-element shape functions (structure) and (fluid), and normal , one obtains schematically

Here (and ) map pressure to structural tractions and have units of N/Pa, while maps structural normal acceleration to pressure and carries units of kg/ (entering the block as in ). Thus is the inertial (acceleration-pressure) coupling associated with .

These integrals ensure the continuity of the normal displacement and stress across . In the present approach, coupling is implemented by assembling off-diagonal matrices that encapsulate the interaction terms. The routine computes the coupling contributions with high numerical accuracy by integrating the product of the acoustic and structural shape functions over the common interfaces using high-order Gauss-Legendre quadrature. This meticulous assembly process ensures that the dynamic interactions at the interface are faithfully represented in the global stiffness matrix.

The resultant block-structured eigenvalue problem, which couples the fluid and structural subdomains, inherently accounts for the influence of the surrounding fluid on the structural vibrations and vice versa. Consequently, the coupled system exhibits modified natural frequencies and mode shapes more representative of real-world vibroacoustic phenomena. This enhanced predictive capability is critical for applications where subtle fluid–structure interactions can significantly impact performance, such as in aerospace, automotive, and civil engineering systems.

2.4. Assembly of the Final System

The culmination of the proposed formulation lies in the meticulous assembly of the final global system, which integrates the discrete contributions from the structural and acoustic domains and their mutual coupling. This stage systematically consolidates the high-order stiffness and mass matrices—constructed via Gauss-Legendre quadrature and high-order shape functions—into a block-structured eigenvalue problem that faithfully represents the coupled vibroacoustic behavior.

In the structural domain, the global stiffness matrix and mass matrix are assembled from elemental contributions. Similarly, for the fluid domain, the Helmholtz-like formulation yields the acoustic matrices and , whose assembly mirrors that of the structural matrices but accounts for the unique properties of the fluid medium. These individual matrices are coupled via dedicated off-diagonal matrices that integrate the interaction terms across the shared interfaces using high-order quadrature rules.

Once these subdomain matrices are established, the final global system is expressed in a partitioned form as follows:

where and represent the vectors of generalized nodal displacements and pressures, respectively. In practice, this block-structured system encapsulates the intrinsic dynamic behavior of each subdomain and the critical fluid–structure interactions that alter both the natural frequencies and the corresponding mode shapes.

The implementation enforces boundary conditions by identifying and eliminating constrained degrees of freedom before solving the eigenvalue problem. For instance, clamped structural boundaries are rigorously enforced by constraining the relevant nodal displacements, whereas acoustic boundaries are enforced via Dirichlet or Neumann conditions. Under pure Neumann conditions, the continuous Helmholtz operator admits a constant-pressure null mode at . An initial estimation procedure is also employed—particularly in scenarios where rigid body modes may obscure the actual dynamic response—to guide the eigenvalue solver toward the correct spectral region. Eigenpairs are computed by shift-invert extraction about ; the factorization of is performed once per shift with a direct sparse solver, and the resulting subspace iteration returns the requested portion of the spectrum. Furthermore, the assembly process includes post-processing steps, such as Cholesky factorization of the mass matrix and subsequent orthonormalization of the eigenvectors. This ensures that the computed modes are numerically robust and physically meaningful.

3. Model Description

This section delineates the model’s geometric configuration, material properties, and boundary conditions employed to validate the proposed coupled vibroacoustic formulation. The structural domain consists of an aluminum rectangular plate with a cross-sectional layout in the plane and a thickness development along the y axis. Specifically, the plate has dimensions of cm, cm, and cm. The structural model is configured for validation purposes with clamped boundary conditions along all edges in the x and z directions—namely, at , , , and . These constraints effectively fix all three translational degrees of freedom at the boundaries, ensuring that the modal analysis captures the plate’s inherent stiffness characteristics.

Complementing the structural domain, the fluid domain consists of two air volumes that interface directly with the plate at its top and bottom surfaces (i.e., at and ). These air volumes share the same cross-sectional dimensions as the aluminum plate, ensuring geometric consistency between the domains. The extension of the fluid domain in the y direction is determined according to established guidelines for pressure-release boundaries in acoustic and seismic simulations [3]. In practice, a fluid layer thickness of about one wavelength is sufficient to attenuate outgoing waves effectively. Given that the lowest eigenfrequency of the coupled system is approximately 2200 Hz, an air layer thickness of 15 cm is selected to ensure realistic behavior of the pressure field before it reaches the outer boundary, where Dirichlet-type conditions (i.e., ) are enforced. The observed smoother convergence when the fluid is included is attributed to the added-mass effect and the spectral separation it induces in the coupled pencil. Accounting for compressibility avoids non-negligible errors in pressure prediction for vibrating shells interacting with air [34].

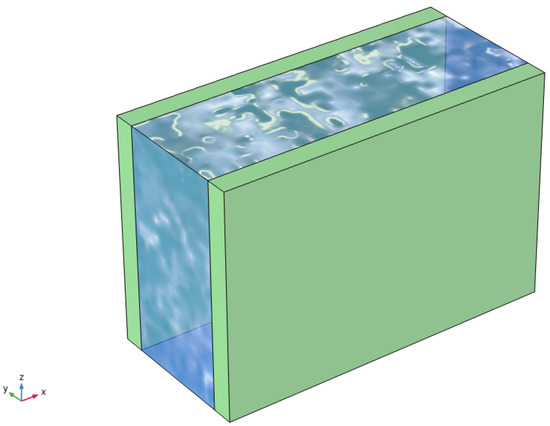

Material properties for the aluminum structure and the air are comprehensively detailed in Table 1. Integrating these properties into the CUF framework provides a robust representation of the coupled dynamics, as structural stiffness and mass, along with acoustic parameters (e.g., speed of sound and density), are directly incorporated into the global eigenvalue problem. Figure 1 offers a schematic illustration of the model domains, providing a visual context for the geometric and boundary condition setup.

Table 1.

Material properties of the structure (aluminum) and the fluid (air).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the model domains; the aluminum plate is green, while the air volumes are gray.

The model description encapsulates a carefully calibrated representation of a coupled fluid–structure system. By combining refined high-order FE techniques with judicious choices in domain geometry and material parameters, the framework establishes a solid foundation for validating the vibroacoustic formulation. Integrating theory, numerical implementation, and physical modeling is critical for advancing the predictive capabilities and computational efficiency of modern coupled analyses.

4. Formulation Validation

The validity of the proposed CUF-based formulation for coupled vibroacoustic modal analysis is rigorously demonstrated through a series of numerical experiments benchmarked against a reference FE model in Comsol Multiphysics 6.2. The Comsol model, employing classical HEX8 elements, serves as a trusted baseline for assessing the high-order formulation’s accuracy and computational efficiency.

A comprehensive cross-section mesh-refinement study is conducted to assess the convergence characteristics of the proposed method. To this aim, the node spacing along the thickness direction is fixed to 5 mm: in Comsol, such seeding results in 2 and 30 first-order elements in the structure and fluid thicknesses, respectively; in CUF, it leads to 1 and 15 B3 elements in the structure and fluid thicknesses, respectively. Table 2 and Table 3 summarize the evolution of the degrees of freedom and the corresponding eigenfrequencies for the in vacuo and fully coupled fluid–structure Comsol models, respectively. As the mesh is refined, the eigenfrequencies converge steadily, and the frequency shifts between successive refinements diminish to negligible levels. Subsequently, three CUF models are built, each with Lagrangian-type elements and different kinematic orders in the cross-section (2D elements with 4, 9, or 16 nodes). For each of these models, a cross-section mesh-convergence analysis is performed, with the results shown in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9.

Table 2.

Mesh convergence analysis for the Comsol in vacuo structural model. Aluminum material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shifts between subsequent mesh refinements are equal to −14.34%, −3.32%, and −0.67%, respectively.

Table 3.

Mesh convergence analysis for the Comsol coupled fluid–structure model. Aluminum material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shifts between subsequent mesh refinements are equal to −0.10%, −0.01%, and 0.00%, respectively.

Table 4.

Mesh convergence analysis for the CUF LE4B3 in vacuo structural model (LE4/LE9/LE16 denote bilinear/biquadratic/bicubic quadrilateral cross-section elements; B3 denotes quadratic 1D thickness interpolation). Aluminum material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shifts between subsequent mesh refinements are equal to −18.85%, −8.78%, and −2.89%, respectively.

Table 5.

Mesh convergence analysis for the CUF LE4B3 coupled fluid–structure model (LE4/LE9/LE16 denote bilinear/biquadratic/bicubic quadrilateral cross-section elements; B3 denotes quadratic 1D thickness interpolation). Aluminum material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shifts between subsequent mesh refinements are equal to −0.92%, −0.25%, and −0.07%, respectively.

Table 6.

Mesh convergence analysis for the CUF LE9B3 in vacuo structural model (LE4/LE9/LE16 denote bilinear/biquadratic/bicubic quadrilateral cross-section elements; B3 denotes quadratic 1D thickness interpolation). Aluminum material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shifts between subsequent mesh refinements are equal to −11.97% and −2.65%, respectively.

Table 7.

Mesh convergence analysis for the CUF LE9B3 coupled fluid–structure model (LE4/LE9/LE16 denote bilinear/biquadratic/bicubic quadrilateral cross-section elements; B3 denotes quadratic 1D thickness interpolation). Aluminum material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shifts between subsequent mesh refinements are equal to −0.10% and −0.01%, respectively.

Table 8.

Mesh convergence analysis for the CUF LE16B3 in vacuo structural model (LE4/LE9/LE16 denote bilinear/biquadratic/bicubic quadrilateral cross-section elements; B3 denotes quadratic 1D thickness interpolation). Aluminum material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shifts between subsequent mesh refinements are equal to −1.74% and −0.37%, respectively.

Table 9.

Mesh convergence analysis for the CUF LE16B3 coupled fluid–structure model (LE4/LE9/LE16 denote bilinear/biquadratic/bicubic quadrilateral cross-section elements; B3 denotes quadratic 1D thickness interpolation). Aluminum material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shift between subsequent mesh refinements is 0.00%.

It is clear that the mesh converge is reached in a smoother manner for the coupled fluid–structure analyses rather than for the in vacuo structural ones, probably due to the surrounding fluid damping effect. Therefore, to identify the convergent discretizations for each FE theory, in vacuo results are considered. In this analysis, convergence results are obtained as percentage error, computed as:

where:

- is the target performance (i.e., an eigenfrequency) obtained with a finer mesh;

- is the target performance (i.e., an eigenfrequency) obtained with a coarser mesh.

Convergence is claimed when successive refinements produce relative changes below on the target eigenfrequencies [35,36]; this is consistent with industry practice in frequency-domain FE analyses (see, e.g., ANSYS guidance for modal accuracy [37]) and aligns with verification principles whereby mesh-induced numerical uncertainty is reduced to within acceptable engineering tolerance. The values reported in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 satisfy this criterion, with frequency drifts decreasing monotonically across refinements. On this basis, the Comsol model converges with 5565 structural DoFs, 84,987 total DoFs, and 150 cross-section elements; the CUF LE4B3 model converges with 22,509 structural DoFs, 177,571 total DoFs, and 2400 cross-section elements; the CUF LE9B3 model converges with 5859 structural DoFs, 46,221 total DoFs, and 150 cross-section elements; the CUF LE16B3 model converges with 3600 structural DoFs, 28,400 total DoFs, and 40 cross-section elements. This convergence behavior not only validates the accuracy of the CUF approach but, when adopting high-order kinematics, also highlights its ability to achieve high precision with a substantially reduced number of degrees of freedom compared to traditional full three-dimensional discretizations [1,2].

The comparison results of each analyzed convergent model, with clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions, numerically validating the proposed CUF implementation for coupled vibroacoustic modal analysis, are shown in Table 10. Afterwards, to demonstrate a generalized applicability of the formulation proposed herein, some configurations with different properties are considered: results related to the same coupled model, but with only the plane at cm structurally clamped, thus leading to a classical cantilever configuration, are reported in Table 11. Furthermore, Table 12 presents results related to clamped structural and rigid fluid boundary conditions. Finally, considering again the initial clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions, Table 13 presents a comparison of results obtained, rather than for an aluminum isotropic structure, for an unidirectional carbon fiber plate, numerically modeled as an equivalent orthotropic layer, with density equal to 1600 kg/, fiber principal direction along x-axis, and whose elastic properties are reported in Table 14.

Table 10.

Comparison of eigenfrequencies between Comsol and CUF, concerning the coupled (displacement–pressure) model. Aluminum material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shifts compared to Comsol Multiphysics 6.2 are equal to −0.04%, −0.06%, and −0.06%, respectively.

Table 11.

Comparison of eigenfrequencies between Comsol and CUF, concerning the coupled (displacement–pressure) model. Aluminum material, cantilever structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shifts compared to Comsol Multiphysics 6.2 are equal to 0.22%, −0.01%, and −0.01%, respectively.

Table 12.

Comparison of eigenfrequencies between Comsol and CUF, concerning the coupled (displacement–pressure) model. Aluminum material, clamped structural and rigid fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shifts compared to Comsol Multiphysics 6.2 are all equal to −0.07%.

Table 13.

Comparison of eigenfrequencies between Comsol and CUF, concerning the coupled (displacement–pressure) model. Unidirectional carbon fiber material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shifts compared to Comsol Multiphysics 6.2 are equal to −0.04%, −0.06%, and −0.06%, respectively.

Table 14.

Material properties of the unidirectional carbon fiber structure, modeled as an equivalent orthotropic layer.

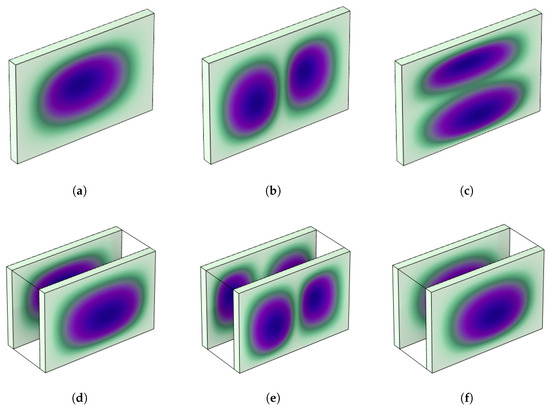

Subsequently, a more convoluted multi-layered model is introduced, representing a sandwich-like package that, in its in vacuo configuration, is constituted by two clamped aluminum structural plates (whose material and geometrical properties are the same of the single one analyzed so far) encapsulating a water fluid volume ( kg/ and m/s) with a thickness equal to cm subdivided into five B3 elements, and having rigid lateral boundary conditions, represented in Figure 2. It should be noted that, since the correspondent in vacuo model involves two identical aluminum plates that are not in contact, the modal behavior of such a configuration is exactly the same of one of these two structures, taken independently. The comparison results of the convergent models with different structural theories are shown in Table 15.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the sandwich-like model domains; the aluminum plates are green, while the water volume is represented with a realistic texture.

Table 15.

Comparison of eigenfrequencies between Comsol and CUF, concerning the coupled (displacement–pressure) multi-layered model. Aluminum structures with clamped boundary conditions, internal water with rigid fluid boundary conditions. The average frequency shifts compared to Comsol Multiphysics 6.2 are equal to −1.01%, 0.00%, and 0.33%, respectively.

Overall, the extensive validation of the formulation against both commercial solvers and a variety of boundary and material conditions substantiates the efficacy of the CUF-based approach. The high-order discretization, coupled with efficient numerical integration and a rigorous treatment of interface conditions, ensures that the method is not only computationally efficient but also capable of accurately predicting the dynamic behavior of complex coupled systems.

5. Results and Discussion

In this section, the performance of the proposed CUF-based formulation is scrutinized through a detailed analysis of coupled vibroacoustic behavior using the CUF LE9B3 approach. These numerical analyses focus on comparing the in vacuo (displacement-only) and coupled (displacement–pressure) models under various boundary and material conditions, thereby providing comprehensive insight into the complex fluid–structure interactions.

Firstly, Table 16 reports a comparison of the first ten eigenfrequencies between in vacuo (displacement) and coupled (displacement–pressure) models, considering an aluminum plate with clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions, whose modal shapes are shown side-by-side in Figure 3. Moreover, Table 17, Table 18, Table 19 and Table 20 and Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 present the first ten eigenfrequencies between in vacuo (displacement) and coupled (displacement–pressure) models with their modal shapes, respectively, for the same other configurations described in Section 4.

Table 16.

Comparison of eigenfrequencies between in vacuo (displacement) and coupled (displacement–pressure) CUF LE9B3 models. Aluminum material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. Multiple (nearly) coincident frequencies stem from geometric symmetries yielding mode multiplicities.

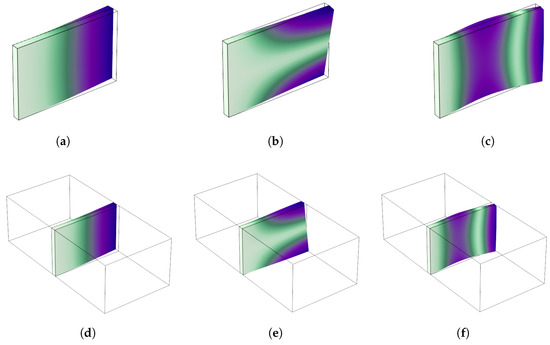

Figure 3.

Comparison of the first three non-rigid modal shapes between in vacuo (displacement) and coupled (displacement–pressure) models. Deformation of the structure is scaled to enhance visual comparison across all subfigures. Aluminum material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. (a) 1st modal shape of the in vacuo model, 6306 Hz. (b) 2nd modal shape of the in vacuo model, 9485 Hz. (c) 3rd modal shape of the in vacuo model, 14,430 Hz. (d) 1st modal shape of the coupled model, 2139 Hz. (e) 2nd modal shape of the coupled model, 2139 Hz. (f) 3rd modal shape of the coupled model, 2681 Hz.

Table 17.

Comparison of eigenfrequencies between in vacuo (displacement) and coupled (displacement–pressure) CUF LE9B3 models. Aluminum material, cantilever structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. Multiple (nearly) coincident frequencies stem from geometric symmetries yielding mode multiplicities.

Table 18.

Comparison of eigenfrequencies between in vacuo (displacement) and coupled (displacement–pressure) CUF LE9B3 models. Aluminum material, clamped structural and rigid fluid boundary conditions. Multiple (nearly) coincident frequencies stem from geometric symmetries yielding mode multiplicities.

Table 19.

Comparison of eigenfrequencies between in vacuo (displacement) and coupled (displacement–pressure) CUF LE9B3 models. Unidirectional carbon fiber material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. Multiple (nearly) coincident frequencies stem from geometric symmetries yielding mode multiplicities.

Table 20.

Comparison of eigenfrequencies between in vacuo (displacement) and coupled (displacement–pressure) CUF LE9B3 models. Aluminum structures with clamped boundary conditions, internal water with rigid fluid boundary conditions. Multiple (nearly) coincident frequencies stem from geometric symmetries yielding mode multiplicities.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the first three non-rigid modal shapes between in vacuo (displacement) and coupled (displacement–pressure) models. Deformation of the structure is scaled to enhance visual comparison across all subfigures. Aluminum material, cantilever structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. (a) 1st modal shape of the in vacuo model, 378 Hz. (b) 2nd modal shape of the in vacuo model, 1214 Hz. (c) 3rd modal shape of the in vacuo model, 2303 Hz. (d) 1st modal shape of the coupled model, 378 Hz. (e) 2nd modal shape of the coupled model, 1214 Hz. (f) 3rd modal shape of the coupled model, 2137 Hz.

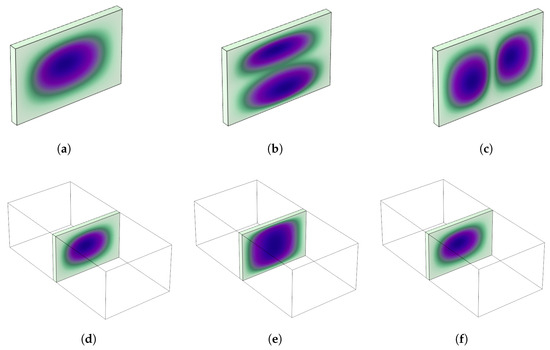

Figure 5.

Comparison of the first three non-rigid modal shapes between in vacuo (displacement) and coupled (displacement–pressure) models. Deformation of the structure is scaled to enhance visual comparison across all subfigures. Aluminum material, clamped structural and rigid fluid boundary conditions. (a) 1st modal shape of the in vacuo model, 6306 Hz. (b) 2nd modal shape of the in vacuo model, 9485 Hz. (c) 3rd modal shape of the in vacuo model, 14,430 Hz. (d) 3rd modal shape of the coupled model, 1143 Hz. (e) 4th modal shape of the coupled model, 1143 Hz. (f) 5th modal shape of the coupled model, 1143 Hz.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the first three non-rigid modal shapes between in vacuo (displacement) and coupled (displacement–pressure) models. Deformation of the structure is scaled to enhance visual comparison across all subfigures. Unidirectional carbon fiber material, clamped structural and pressure-release fluid boundary conditions. (a) 1st modal shape of the in vacuo model, 4349 Hz. (b) 2nd modal shape of the in vacuo model, 7437 Hz. (c) 3rd modal shape of the in vacuo model, 8540 Hz. (d) 1st modal shape of the coupled model, 2139 Hz. (e) 2nd modal shape of the coupled model, 2139 Hz. (f) 3rd modal shape of the coupled model, 2681 Hz.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the first three non-rigid modal shapes between in vacuo (displacement) and coupled (displacement–pressure) models. Deformation of the structure is scaled to enhance visual comparison across all subfigures. Aluminum structures with clamped boundary conditions, internal water with rigid fluid boundary conditions. (a) 1st modal shape of the in vacuo model, 6306 Hz. (b) 2nd modal shape of the in vacuo model, 9485 Hz. (c) 3rd modal shape of the in vacuo model, 14,430 Hz. (d) 2nd modal shape of the coupled model, 3982 Hz. (e) 3rd modal shape of the coupled model, 4704 Hz. (f) 4th modal shape of the coupled model, 6561 Hz.

As expected, the surrounding fluid lowers the structural eigenfrequencies relative to the in vacuo case and introduces additional resonance families characteristic of coupled vibroacoustics. The lowest coupled modes reflect a balance between plate bending stiffness and cavity compressibility. Predominantly structural modes show small pressure gradients; cavity-dominated modes show nearly uniform wall motion with strong pressure antinodes. Mixed modes appear when the panel wavelength becomes comparable to the cavity acoustic wavelength. The zero frequency reported for rigid-wall fluids is the expected Neumann-Laplacian null mode with constant pressure. The results confirm the accuracy and efficiency of the CUF-based formulation. High-order expansions reduce the degrees of freedom needed for convergence relative to full three-dimensional meshes. Comparable evaluation protocols appear in reinforced laminated shells and automotive composite panels [38,39]. This methods-oriented study is focused on interior cavity-panel eigenpairs and code-to-code comparisons of eigenfrequencies and qualitative shapes; broader correlations based on Modal Assurance Criterion (MAC) and additional boundary combinations are natural extensions and will be addressed in follow-up work [40].

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

This work presents a robust, computationally efficient formulation for coupled vibroacoustic modal analysis based on the CUF method. The proposed approach successfully decouples the complex three-dimensional behavior into manageable subproblems by leveraging high-order polynomial expansions in both the cross-sectional and thickness directions. The resulting formulation yields accurate predictions of natural frequencies and mode shapes for both the structural and acoustic fields and provides a unified framework for capturing the intricate fluid–structure interactions observed in real-world applications.

The extensive validation against benchmark models, including comparisons with Comsol Multiphysics results, demonstrates that the CUF-based high-order FEM consistently converges with substantially fewer degrees of freedom than traditional full three-dimensional discretizations. Moreover, the implementation accommodates a variety of boundary conditions and material models, from isotropic aluminum to equivalent orthotropic carbon fiber configurations.

In addition to establishing the method’s accuracy and efficiency, the work highlights several promising avenues for future research. First, nonlinear models of in-plane shear damage in composites [41] can be integrated with the CUF framework to predict damage evolution under operational conditions. Second, further investigation into the optimal mapping and coupling degrees of freedom at the fluid–structure interface may lead to improved computational performance and enhanced predictive capabilities, even through the implementation of a fluid–structure coupling for layers having cross-section shape functions based on Taylor polynomial expansions, which would greatly reduce the overall DoFs. Integrating structural reliability software and advanced monitoring tools [42] may further enhance the predictive capabilities of the CUF-based formulation. Furthermore, integrating thermo-based fatigue life prediction methods, as reviewed by [43], may provide additional insights into the durability of coupled systems under cyclic loading. Future enhancements could integrate structural health monitoring procedures using artificial neural networks [44]. Future research could also benefit from integrating advanced machine learning techniques for damage assessment in composite structures [45]. Moreover, incorporating data-driven approaches, such as machine learning techniques, with the high-order CUF framework could enable real-time optimization and adaptive control of vibroacoustic systems, opening new pathways for innovative materials and advanced structural health monitoring [7,13]. Finally, the adoption of explainable artificial intelligence techniques for creep life prediction, as discussed by [46], could be synergistically combined with the CUF framework for real-time optimization. Recent efforts also highlight the promise of machine learning and deep-learning-based methods for handling large-scale vibroacoustic data sets, even in cases with low signal sparsity or high compression requirements [47]. These data-driven approaches could be integrated into the CUF-based formulation to enable real-time reconstruction of responses and adaptive control in future implementations.

Overall, the proposed CUF-based formulation represents a significant advancement in vibroacoustic analysis. Its ability to accurately and efficiently model coupled systems while maintaining a high degree of flexibility regarding material and boundary condition specifications lays a strong foundation for future developments. As computational demands grow increasingly complex, this work presents a promising approach to addressing the challenges of modern engineering design and analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.; methodology, D.M.; software, D.M.; validation, D.M.; formal analysis, D.M.; investigation, D.M.; resources, D.M.; data curation, D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.; writing—review and editing, D.M.; visualization, D.M.; supervision, D.M.; project administration, D.M.; funding acquisition, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) and the Sustainable Mobility Center (MOST) through the project PNRR-M4C2-CNMS-Spoke 1, under the scheme CN00000023-PNRR-M4C2 Inv. 1.4 (grant no. 55-PRR22-1155-22-GG002138).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article. This article presents a methodological and computational contribution, not an empirical or data-driven study. It introduces a high-order vibroacoustic formulation within a CUF-based finite-element framework and demonstrates its validity by solving generalized eigenvalue problems. Validation is conducted by comparing results with a reference Comsol model to establish accuracy and efficiency. All necessary inputs (such as equations, geometries, material properties, and boundary conditions) are fully specified in the manuscript. The resulting eigenfrequencies and mode shapes are comprehensively reported in figures and tables. Therefore, no additional observational or measurement data exist beyond what is included in the article. Intermediate computational artifacts (e.g., solver outputs, meshes, or log files) are implementation-specific and do not constitute standalone datasets. As such, there is no reusable data to archive or share independently of the procedure described.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carrera, E.; Zappino, E. Carrera unified formulation for free-vibration analysis of aircraft structures. AIAA J. 2016, 54, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliacano, D.; Ouisse, M.; Rosa, S.; Franco, F.; Khelif, A. Investigations about the modelling of acoustic properties of periodic porous materials with the shift cell approach. In Proceedings of the 9th ECCOMAS Thematic Conference on Smart Structures and Materials (SMART 2019), Paris, France, 8–11 July 2019; pp. 1112–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Komatitsch, D.; Tromp, J. A perfectly matched layer for the absorption of seismic waves. Geophys. J. Int. 2003, 154, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliacano, D.; Ouisse, M.; Khelif, A.; De Rosa, S.; Franco, F.; Atalla, N. Computation of wave dispersion characteristics in periodic porous materials modeled as equivalent fluids. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Noise and Vibration Engineering (ISMA 2018), Leuven, Belgium, 17–19 September 2018; pp. 4741–4751. [Google Scholar]

- Filippi, M.; Magliacano, D.; Petrolo, M.; Carrera, E. Variable-Kinematics Finite Elements for Propagation Analyses of Two-Dimensional Waveguides. In Proceedings of the 30th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Rome, Italy, 4–7 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M.; Magliacano, D.; Petrolo, M.; Carrera, E. Wave Propagation in Pre-stressed Structures with Geometric Non-linearities through Carrera Unified Formulation. In Proceedings of the 30th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Rome, Italy, 4–7 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaburo, A.; Magliacano, D.; Petrone, G.; Franco, F.; de Rosa, S. Optimizing the acoustic properties of a meta-material using machine learning techniques. In Proceedings of the 50th International Congress and Exposition of Noise Control Engineering (INTER-NOISE 2021), Washington, DC, USA, 1–4 August 2021; Paper Number 2294. pp. 1948–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catapane, G.; Magliacano, D.; Petrone, G.; Casaburo, A.; Franco, F.; De Rosa, S. Labyrinth Resonator Design for Low-Frequency Acoustic Meta-Structures. Mech. Mach. Sci. 2022, 125, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Guasch, O.; Maxit, L.; Zheng, L. Transmission loss of plates with multiple embedded acoustic black holes using statistical modal energy distribution analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 150, 107262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Liu, X.; Yuan, J.; Bao, Y.; Shan, Y.; He, T. Influence of Acoustic Black Hole Array Embedded in a Plate on Its Energy Propagation and Sound Radiation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Liao, X.; Fu, Q.; Zong, C. Vibro-Acoustic Analysis of Rectangular Plate–Cavity Parallelepiped Coupling System Embedded with 2D Acoustic Black Holes. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackerle, J. Finite element linear and nonlinear, static and dynamic analysis of structural elements: A bibliography (1992–1995). Eng. Comput. 1997, 14, 347–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M.; Magliacano, D.; Petrolo, M.; Carrera, E. Wave Propagation in Prestressed Structures with Geometric Nonlinearities through Carrera Unified Formulation. AIAA J. 2025, 63, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinefra, M.; Carrera, E.; Della Croce, L.; Chinosi, C. Refined shell elements for the analysis of functionally graded structures. Compos. Struct. 2012, 94, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinefra, M.; Carrera, E.; Valvano, S. Variable Kinematic Shell Elements for the Analysis of Electro-Mechanical Problems. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2015, 22, 77–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cinefra, M.; Kumar, S.K.; Carrera, E. MITC9 Shell elements based on RMVT and CUF for the analysis of laminated composite plates and shells. Compos. Struct. 2019, 209, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozio, L.; and, L.A. Variable kinematic finite element models of multilayered composite plates coupled with acoustic fluid. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2016, 23, 981–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliacano, D.; Tufano, V.; Letizia, A.; Sessa, B.; Filippi, M. Data-driven failure criteria prediction in composite wing boxes using machine learning. Compos. Struct. 2025, 373, 119675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, W.J. Pre-stressed viscoelastic composites: Effective incremental moduli and band-gap tuning. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Numerical Analysis and Applied Mathematics 2010 (ICNAAM 2010), Rhodes, Greece, 19–25 September 2010; Volume 1281, pp. 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Su, Y.C.; Hou, X.H.; Meng, J.M.; Deng, Z.C. Effect of pre-load on wave propagation characteristics of hexagonal lattices. Compos. Struct. 2018, 203, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnwell, E.G.; Parnell, W.J.; Abrahams, I.D. Antiplane elastic wave propagation in pre-stressed periodic structures; tuning, band-gap switching and invariance. Wave Motion 2016, 63, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gei, M. Wave propagation in quasiperiodic structures: Stop/pass band distribution and prestress effects. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2010, 47, 3067–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gei, M.; Movchan, A.; Bigoni, D. Band-gap shift and defect-induced annihilation in prestressed elastic structures. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 063507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnwell, E.G.; Parnell, W.J.; Abrahams, I.D. Tunable elastodynamic band gaps. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2017, 12, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascalis, R.; Donateo, T.; Ficarella, A.; Parnell, W.J. Optimal design of phononic media through genetic algorithm-informed pre-stress for the control of antiplane wave propagation. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2020, 40, 100896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierro, E.; Mucchi, E.; Soria, L.; Vecchio, A. On the vibro-acoustical operational modal analysis of a helicopter cabin. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2009, 23, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkup, S. The Boundary Element Method in Acoustics: A Survey. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Escalera Mendoza, A.S.; Griffith, D.T. Experimental and numerial study of high-order complex curvature mode shape and mode coupling on a three-bladed wind turbine assembly. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 160, 107873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, A.; Carrera, E. Unified formulation of geometrically nonlinear refined beam theories. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2018, 25, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlenburg, F. Finite Element Analysis of Acoustic Scattering; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Available online: https://nzdr.ru/data/media/biblio/kolxoz/M/MN/MNf/Ihlenburg%20F.%20Finite%20element%20analysis%20of%20acoustic%20scattering%20(Springer,%201998)(ISBN%200387983198)(241s)_MNf_.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Petrolo, M.; Kaleel, I.; De Pietro, G.; Carrera, E. Wave propagation in compact, thin-walled, layered, and heterogeneous structures using variable kinematics finite elements. Int. J. Comput. Methods Eng. Sci. Mech. 2018, 19, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Hwang, J.; Ryu, J.; Song, M. Prediction of Vibration-Mode-Induced Noise of Structure–Acoustic Coupled Systems. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everstine, G.C. A symmetric potential formulation for fluid–structure interaction. J. Sound Vib. 1981, 79, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Tang, B.; Kaewunruen, S. Dynamic Pressure Analysis of Hemispherical Shell Vibrating in Unbounded Compressible Fluid. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roache, P.J. Verification and Validation in Computational Science and Engineering; Hermosa Publishers: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- ASME V&V 10-2006; Guide for Verification and Validation in Computational Solid Mechanics. American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- ANSYS, Inc. Are There Guideline About the Mesh Convergence for Structural Analysis? ANSYS, Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Wang, N.; Tian, Y.; Kuang, W.; Wei, L.; Zheng, Z. Analysis of Vibration and Acoustic Radiation Characteristics of Reinforced Laminated Cylindrical Shell Structure. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascone, N.; Caivano, L.; D’Errico, G.; Citarella, R. Vibroacoustic Assessment of an Innovative Composite Material for the Roof of a Coupe Car. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemang, R.J. The Modal Assurance Criterion—Twenty Years of Use and Abuse. In Proceedings of the IMAC XXI, Kissimmee, FL, USA, 3–6 February 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fanteria, D.; Panettieri, E. A non-linear model for in-plane shear damage and failure of composite laminates. Aerotec. Missili Spaz. 2014, 93, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj Chehade, F.; Younes, R. Structural reliability software and calculation tools: A review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2020, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z. Thermo-based fatigue life prediction: A review. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2023, 46, 3121–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaimo, A.; Barracco, A.; Milazzo, A.; Orlando, C. Structural Health Monitoring Procedure for Composite Structures through the use of Artificial Neural Networks. Aerotec. Missili Spaz. 2015, 94, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro Junior, R.F.; Gomes, G.F. On the Use of Machine Learning for Damage Assessment in Composite Structures: A Review. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2024, 31, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, B.O.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, B.H.; Lee, J.H. Prediction of Creep Life Using an Explainable Artificial Intelligence Technique and Alloy Design Based on the Genetic Algorithm in Creep-Strength-Enhanced Ferritic 9% Cr Steel. Met. Mater. Int. 2023, 29, 1334–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Xue, Z.; Ou, J. Deep learning-based sparsity-free compressive sensing method for high accuracy structural vibration response reconstruction. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 211, 111168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).